Gemstones In The Bible on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A range of

Amethyst, Heb. ''ahlmh''; Sept. ''amethystos'', also Apoc., xxi, 20. This is the twelfth and last stone of the foundation of the New Jerusalem. It is the third stone in the third row of the rational, representing the tribe of

Amethyst, Heb. ''ahlmh''; Sept. ''amethystos'', also Apoc., xxi, 20. This is the twelfth and last stone of the foundation of the New Jerusalem. It is the third stone in the third row of the rational, representing the tribe of

Chrysolite, Heb. ''trshysh'' (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13; Ezech., i, 16; x, 9; xxviii, 13; Cant., v, 14; Dan., x, 6); Sept., ''chrysolithos'' (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13; Ezech., xxviii, 13); ''tharsis'' (Cant., v, 14; Dan., x, 6); ''tharseis'' (Ezech., 1, 16; x, 9); Vulg. ''chrysolithus'' (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13; Ezech., x, 9; xxviii, 13; Dan., x, 6),

''hyacinthus'' (Cant., v, 14); ''quasi visio maris'' (Ezech., i, 16); Apoc., xxi, 20, ''chrysolithos''; Vulg. ''chrysolithus''. This is the tenth stone of the rational, representing the tribe of

Chrysolite, Heb. ''trshysh'' (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13; Ezech., i, 16; x, 9; xxviii, 13; Cant., v, 14; Dan., x, 6); Sept., ''chrysolithos'' (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13; Ezech., xxviii, 13); ''tharsis'' (Cant., v, 14; Dan., x, 6); ''tharseis'' (Ezech., 1, 16; x, 9); Vulg. ''chrysolithus'' (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13; Ezech., x, 9; xxviii, 13; Dan., x, 6),

''hyacinthus'' (Cant., v, 14); ''quasi visio maris'' (Ezech., i, 16); Apoc., xxi, 20, ''chrysolithos''; Vulg. ''chrysolithus''. This is the tenth stone of the rational, representing the tribe of

Ligurus, Heb. ''lshs''; Sept. ''ligyrion''; Vulg. ''ligurius''; the first stone of the third row of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12), representing Gad. It is missing in the Hebrew of Ezech., xxviii, 13, but present in the Greek. This stone is probably the same as hyacinth (St. Epiphan., loc. cit.). This traditional identification, is based upon

the remark that the twelve foundation stones of the celestial city in Apoc., xxi, 19-20, correspond to the twelve stones of the rational. This alone is enough to equate ligurus with hyacinth although it has been identified with

Ligurus, Heb. ''lshs''; Sept. ''ligyrion''; Vulg. ''ligurius''; the first stone of the third row of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12), representing Gad. It is missing in the Hebrew of Ezech., xxviii, 13, but present in the Greek. This stone is probably the same as hyacinth (St. Epiphan., loc. cit.). This traditional identification, is based upon

the remark that the twelve foundation stones of the celestial city in Apoc., xxi, 19-20, correspond to the twelve stones of the rational. This alone is enough to equate ligurus with hyacinth although it has been identified with

Topaz, Heb. ''ghtrh''; Sept. ''topazion''; Vulg. ''topazius'', the second stone of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 19), representing

Topaz, Heb. ''ghtrh''; Sept. ''topazion''; Vulg. ''topazius'', the second stone of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 19), representing

gemstones

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, or semiprecious stone) is a piece of mineral crystal which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. However, certain rocks (such as lapis lazuli, opal, ...

are mentioned in the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

, particularly in the Old Testament and the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

. Much has been written about the precise identification of these stones, although largely speculative.

History

TheHebrews

The terms ''Hebrews'' (Hebrew: / , Modern: ' / ', Tiberian: ' / '; ISO 259-3: ' / ') and ''Hebrew people'' are mostly considered synonymous with the Semitic-speaking Israelites, especially in the pre-monarchic period when they were still ...

obtained gemstones from the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

. At the time of the Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

, the Bible states that the Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

took gemstones with them (Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

, iii, 22; xii, 35-36). When they were settled in the Land of Israel, they obtained gemstones from the merchant caravans travelling from Babylonia or Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

to Egypt, and those from Saba Saba may refer to:

Places

* Saba (island), an island of the Netherlands located in the Caribbean Sea

* Şaba (Romanian for Shabo), a town of the Odesa Oblast, Ukraine

* Sabá, a municipality in the department of Colón, Honduras

* Saba (river), ...

and Raamah Raamah ( he, , ''Raʿmā'') is a name found in the Torah, meaning "lofty" or "exalted", and possibly "thunder".

The name is first mentioned as the fourth son of Cush, who is the son of Ham, who is the son of Noah in Gen. 10:7, and later appears ...

to Tyre (Book of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Latter Prophets in the Tanakh and one of the major prophetic books, following Isaiah and Jeremiah. According to the book itself, it records six visions of the prophet Ezekiel, exiled in Babylon, during ...

, xxvii, 22). King Solomon even equipped a fleet which returned from Ophir

Ophir (; ) is a port or region mentioned in the Bible, famous for its wealth. King Solomon received a shipment from Ophir every three years (1 Kings 10:22) which consisted of gold, silver, sandalwood, pearls, ivory, apes, and peacocks.

...

, laden with gems ( Books of Kings, x, 11).

Gemstones are mentioned in connection with the breastplate

A breastplate or chestplate is a device worn over the torso to protect it from injury, as an item of religious significance, or as an item of status. A breastplate is sometimes worn by mythological beings as a distinctive item of clothing. It is ...

of the High Priest of Israel (Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

, xxviii, 17-20; xxxix, 10-13), the treasure of the King of Tyre (Book of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Latter Prophets in the Tanakh and one of the major prophetic books, following Isaiah and Jeremiah. According to the book itself, it records six visions of the prophet Ezekiel, exiled in Babylon, during ...

, xxviii, 13), and the foundations of the New Jerusalem ( Book of Tobit, xiii, 16-17, in the Greek text, and more fully, Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

, xxi, 18-21). The twelve stones of the breastplate and the two stones of the shoulder-ornaments were considered by the Jews to be the most

precious. Both Book of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Latter Prophets in the Tanakh and one of the major prophetic books, following Isaiah and Jeremiah. According to the book itself, it records six visions of the prophet Ezekiel, exiled in Babylon, during ...

, xxviii, 13, and Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

, xxi, 18-21, are patterned after the model of the rational and further allude to the Twelve Tribes of Israel

The Twelve Tribes of Israel ( he, שִׁבְטֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵל, translit=Šīḇṭēy Yīsrāʾēl, lit=Tribes of Israel) are, according to Hebrew scriptures, the descendants of the biblical patriarch Jacob, also known as Israel, thro ...

.

At the time of the Septuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond ...

translation, the stones to which the Hebrew names apply could no longer be identified, and translators used various Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words. Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

claimed he had seen the actual stones. The ancients did not classify their gemstones by analyzing their composition and crystalline forms: names were given in accordance with their colour, use or their country of origin. Therefore, stones of the same or nearly the same colour, but of different composition or crystalline form, bear identical names. Another problem is nomenclature; names having changed in the course of time: thus the ancient chrysolite is topaz, sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, or magnesium. The name sapphire is derived via the Latin "sa ...

is lazuli, etc. However, we know most of the stones were precious in Egypt, Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

, and Babylonia.

Alphabetical list

The list comprises comparative etymological origins and referential locations for each stone in the Bible.Agate

Agate

Agate () is a common rock formation, consisting of chalcedony and quartz as its primary components, with a wide variety of colors. Agates are primarily formed within volcanic and metamorphic rocks. The ornamental use of agate was common in Anci ...

, Heb. ''shbw''; Sept. ''achates''; Vulg. ''achates'' (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12, in Heb. and Vulg.; also Ezech., xxviii, 13, in Sept.). This is the second stone of the third row of the rational, where it likely represented the tribe of Asher

Asher ( he, אָשֵׁר ''’Āšēr''), in the Book of Genesis, was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Zilpah (Jacob's eighth son) and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Asher.

Name

The text of the Torah states that the name of ''Asher' ...

. The etymological derivation of the Hebrew word is unclear, but the stone has generally been acknowledged to be the agate. The Hebraic derivation derives ''shbw'' from ''shbb'' "to flame"; it may also be related to Saba (''shba''). Caravans having brought the stone to Palestine. The Greek and Latin names are taken from the river Achates

In Greek and Roman mythology, Achates (Ancient Greek: Ἀχάτης) may refer to the following personages:

* Achates, a companion of the exiled Aeneas.

* Achates, a Sicilian who came to Aristaeus in order to join Dionysus in his Indian campaign ...

(the modern Dirillo

The Dirillo, or Acate, is a river in Sicily which springs from the Hyblaean Mountains and flows through the areas of Vizzini, Licodia Eubea, Mazzarrone, Chiaramonte Gulfi, Acate, Vittoria, Sicily, Vittoria, Gela. It enters the Strait of Sicily so ...

), in ''Sicily'', where this stone was first found (Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

, "''De lapid''.", 38; Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

, "Hist. nat.", XXXVII, liv).

The stone belongs to the silex

Silex is any of various forms of ground stone. In modern contexts the word refers to a finely ground, nearly pure form of silica or silicate.

In the late 16th century, it meant powdered or ground up "flints" (i.e. stones, generally meaning the c ...

family (chalcedony

Chalcedony ( , or ) is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, composed of very fine intergrowths of quartz and moganite. These are both silica minerals, but they differ in that quartz has a trigonal crystal structure, while moganite is monocli ...

species) and is formed by deposits of

siliceous beds in hollows of rocks. This mode of formation results in the bands of various colours which it contains. Its conchoidal cleavage makes it susceptible to a highly polished state.

Various medicinal powers were attributed to this stone until far into the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. Agate was supposed to void the toxicity of all poisons and counteract the infection of contagious diseases; if held in the hand or in the mouth, it was believed to alleviate fever. Within mythology, the eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, j ...

placed an agate in its nest to guard its young against the bite of venomous animals, and the red agate was credited with the power of sharpening vision.

At present, agate and onyx

Onyx primarily refers to the parallel banded variety of chalcedony, a silicate mineral. Agate and onyx are both varieties of layered chalcedony that differ only in the form of the bands: agate has curved bands and onyx has parallel bands. The ...

differ only in the manner in which the stone is cut: if it is cut to show the layers of colour, it is called agate; if cut parallel to the lines, onyx. Formerly, an agate that was banded with well-defined colours was the onyx. The banded agate is used for the manufacturing of cameos.

Amethyst

Amethyst, Heb. ''ahlmh''; Sept. ''amethystos'', also Apoc., xxi, 20. This is the twelfth and last stone of the foundation of the New Jerusalem. It is the third stone in the third row of the rational, representing the tribe of

Amethyst, Heb. ''ahlmh''; Sept. ''amethystos'', also Apoc., xxi, 20. This is the twelfth and last stone of the foundation of the New Jerusalem. It is the third stone in the third row of the rational, representing the tribe of Issachar

Issachar () was, according to the Book of Genesis, the fifth of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's ninth son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Issachar. However, some Biblical scholars view this as an eponymous metaphor providing ...

(Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12); the Septuagint enumerates it among the riches of the King of Tyre (Ezech., xxviii, 13). The Greek name alludes to the popular belief that amethyst prevented intoxication; as such, drinking vessels were made of amethyst for festivities, and carousers wore amulets made of it to counteract the action of wine. Abenesra and Kimchi

''Kimchi'' (; ko, 김치, gimchi, ), is a traditional Korean side dish of salted and fermented vegetables, such as napa cabbage and Korean radish. A wide selection of seasonings are used, including '' gochugaru'' (Korean chili powder), ...

explain the Hebrew ''ahlmh'' in an analogous manner, deriving it from ''hlm'', to dream; ''hlm'' in its first meaning signifies "to be hard". A consensus exists regarding the accuracy of the translation among the various versions; Josephus (Ant. Jud., III, vii, 6) also has "amethyst"; the Targum of Onkelos and the Syriac Version have "calf's eye", indicating the colour.

The amethyst is a brilliant transparent stone of a purple colour and varies in shade from violet purple to rose. There are two kinds of amethysts: the oriental amethyst, a species of sapphire that is very hard (cf. Heb.,''hlm''), and when colourless is almost indistinguishable from the diamond

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, ...

. The occidental amethyst is of the silex family and is different in composition from the oriental stone. But the identity of names is accounted for by the identity of colour. The occidental amethyst is easily engraved and is found in a variety of sizes. Its shape is different from the round pebble to the hexagonal

In geometry, a hexagon (from Greek , , meaning "six", and , , meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

Regular hexagon

A '' regular hexagon'' has ...

, pyramid

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilat ...

-capped crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macro ...

.

Beryl

Beryl

Beryl ( ) is a mineral composed of beryllium aluminium silicate with the chemical formula Be3Al2Si6O18. Well-known varieties of beryl include emerald and aquamarine. Naturally occurring, hexagonal crystals of beryl can be up to several ...

, Heb. ''yhlm''; Sept. ''beryllos''; Vulg. ''beryllus'' occupied the third place of the second row and in the breastplate

A breastplate or chestplate is a device worn over the torso to protect it from injury, as an item of religious significance, or as an item of status. A breastplate is sometimes worn by mythological beings as a distinctive item of clothing. It is ...

, and was understood to represent Nephtali (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 13). According to the Septuagint, it was the second of the fourth row, and third of the fourth according to the Vulgate. Ezech., xxviii, 13, mentions it in the third place, and it is also cited in the Greek text of Tob., xiii, 17; however, it is missing in the Vulgate. Apoc., xxi, 20, gives it as the eighth stone of the foundation of the New Jerusalem.

The etymological debate indicates a difference of opinion regarding the exact Hebrew correlative of this word. The best supported is ''yhlm'', though ''shhm'' is also probable. ''shpht'' has also been suggested, but with little proof. Consequently, the Hebrew ''shpht'' must correspond to jasper, Gr. ''iaspis'' and Lat. ''jaspis''. This mistaken idea probably arose from the supposition that the translated words originally occupied the same position in the original. Comparative analysis of the Greek and Latin translations demonstrates that this is not the case; in the Vulgate, jasper is in the same position as ''yshpht'', whereas the Greek ''beryllos'' does not correspond to the Latin ''beryllus''.

The same may have happened regarding the translation of the Hebrew into Greek, especially because the old manner of writing the two words ''yshlm'' and ''shlm'' might be easily confused. Josephus is not reliable in this instance as he most likely quoted from memory; the position of the words being at variance in his two lists (Bell. Jud., V, v, 7; Ant. Jud., III, vii).

Therefore, the ultimate analysis is limited to the two words ''yshlm'' and ''shlm''. By comparing various texts of the Vulgate - the Greek is very inconsistent - we find that ''shlm''

always translated to onyx. This alone seems sufficient to support the opinion that beryl corresponds to the Heb. ''yhlm''. That beryl was among the stones of the rational appears beyond doubt because all translations mention it and with the etymology giving us no special help, by elimination; we come to the generally accepted conclusion that beryl and ''yhlm'' stand for each other.

Beryl is a stone composed of silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is ...

, alumina, and glucina with beryl and emerald being of the same species. The difference between beryl, aquamarine, and emerald is determined by the colouring and the peculiar shade of each. Beryl, though sometimes colourless (not white), is usually of a light blue bordering on a yellowish green; emerald is more transparent and of a finer hue than beryl. Beryl is also black in colour. As a gem, it is considered more beautiful, and therefore more expensive - aqua marine is a beautiful sea-green variety.

Emerald derives its colour from a small quantity of chromium oxide Chromium oxide may refer to:

* Chromium(II) oxide, CrO

* Chromium(III) oxide, Cr2O3

* Chromium dioxide (chromium(IV) oxide), CrO2, which includes the hypothetical compound chromium(II) chromate

* Chromium trioxide (chromium(VI) oxide), CrO3

* Chro ...

; beryl and aqua marine from a small quantity of iron oxide. Beryl occurs in the shape of either a pebble or of an hexagonal prism

Prism usually refers to:

* Prism (optics), a transparent optical component with flat surfaces that refract light

* Prism (geometry), a kind of polyhedron

Prism may also refer to:

Science and mathematics

* Prism (geology), a type of sedimentary ...

. It is found in metamorphic limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

, slate, mica schist, gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures a ...

and granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

. In ancient times it was mined in Upper Egypt and is still found in the mica slate of Mt. Zaborah. The largest beryls known have been found in Acworth and Grafton, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

, and in Royalston, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

; one weighs 2900 lb. and measures 51 inches in length by 32 inches by 22.

According to John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

in "Miscellanies" beryl has also been employed for mystical and cabalistic

Cabalist or Cabalistic may refer to:

*Cabal, a group of people united in some close design together, usually to promote their private views or interests in a church, state, or other community

*Christian Kabbalah, an incorporation of Jewish Kabbalah ...

practices.

Carbuncle

Carbuncle

A carbuncle is a cluster of boils caused by bacterial infection, most commonly with ''Staphylococcus aureus'' or ''Streptococcus pyogenes''. The presence of a carbuncle is a sign that the immune system is active and fighting the infection. The ...

, Heb., ''nopek''; Sept. ''anthrax'' (Ex., xxviii, 18;

xxxix, 11; Ezech., xxviii, 13; omitted in Ezech., xxvii, 16); Vulg., ''carbunculus'' (Ex., xxviii, 18; xxxix, 11; Ezech., xxviii, 13), ''gemma'' (Ezech., xxvii, 16). The carbuncle was the first stone of the second row of the rational and it represented Juda, and is also the eighth stone mentioned of the riches of the King of Tyre (Ezech., xxviii, 13). An imported object, not a native product, (Ezech., xxvii, 16); it is perhaps the third stone of the foundation of the celestial city (Apoc., xxi, 19).

The ancient authors are not in accordance on the precise nature of the carbuncle stone. It probably corresponded to the ''anthrax'' of Theophrastus (De lap., 18), the ''carbunculus'' of Pliny (Hist. nat., XXXVII, xxv), the ''charchedonius'' of Petronius, and the ''ardjouani'' of the Arabs. If so, it is a red glittering stone, probably the Oriental ruby

A ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum ( aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called ...

, though the appellation may have been applied to a variety of other red gems. Theophrastus describes it as: "Its colour is red and of such a kind that when it is held against the sun it resembles a burning coal." This description fits well with the Oriental ruby. He also relates that the most perfect carbuncles were brought from Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

, Marseilles, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, and the neighbourhood of Siena

Siena ( , ; lat, Sena Iulia) is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.

The city is historically linked to commercial and banking activities, having been a major banking center until the 13th and 14th centur ...

.

Carbuncles were named differently according to their places of origin. Pliny (Hist. nat., XXXVII, xxv) cites the lithizontes, or Indian carbuncles, the amethystizontes, the colour of which resembled amethyst, and sitites. Carbuncle was therefore most probably a generic name which applied to several stones.

Carnelian

Carnelian

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semi-precious gemstone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker (the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often used ...

, Heb. ''arm'', to be red, especially "red blooded"; Sept. and Apoc. ''sardion''; Vulg. ''sardius''; the first stone of the breastplate (Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 10) representing Ruben

Reuben or Reuven is a Biblical male first name from Hebrew רְאוּבֵן (Re'uven), meaning "behold, a son". In the Bible, Reuben was the firstborn son of Jacob.

Variants include Rúben in European Portuguese; Rubens in Brazilian Portuguese ...

; also the first among the stones of the King of Tyre (Ezech., xxviii, 13); the sixth foundation stone of the celestial city (Apoc., xxi, 19). Also found in Noahs story is the unproven that the dove Noah sent down to the ground was actually a garnet used to light the ground.

The word ''sardion'' has sometimes been called ''sardonyx''. This is a mistake, for the same word is equivalent to carnelian in Theophrastus (De lap., 55) and Pliny (Hist. nat., XXXVII, xxxi), who derive the name from that of the city of Sardes

Sardis () or Sardes (; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 ''Sfard''; el, Σάρδεις ''Sardeis''; peo, Sparda; hbo, ספרד ''Sfarad'') was an ancient city at the location of modern ''Sart'' (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, ...

where, they claim, it was first found. The carnelian is a siliceous stone and a species of chalcedony. Its colour is a flesh-hued red, varying from the palest flesh-colour to a deep blood-red. It is of a conchoidal

Conchoidal fracture describes the way that brittle materials break or fracture when they do not follow any natural planes of separation. Mindat.org defines conchoidal fracture as follows: "a fracture with smooth, curved surfaces, typically sli ...

structure. Normally its colour is without clouds or veins; but sometimes delicate veins of extremely light red or white are found arranged much like the rings of an agate. Carnelian is used for rings and seals. The finest carnelians are found in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

.

Chalcedony

Chalcedony

Chalcedony ( , or ) is a cryptocrystalline form of silica, composed of very fine intergrowths of quartz and moganite. These are both silica minerals, but they differ in that quartz has a trigonal crystal structure, while moganite is monocli ...

, Apoc., xxi, 19, ''chalkedon''; Vulg. ''chalcedonius'', the third foundation stone of the celestial Jerusalem. The view that the writing ''chalkedon'' is an error and that it should be ''charkedon'' (the carbuncle) is not without some reason. However, the other eleven stones correspond to a stone in the rational and this is the only exception. The ancients very often confounded the names of these two stones. Chalcedony is a siliceous stone. Its name is supposed to derive from Chalcedon

Chalcedon ( or ; , sometimes transliterated as ''Chalkedon'') was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the cit ...

, in Bithynia, where the ancients obtained the stone from. It is a species of agate and bears various names according to its colour. Chalcedony is usually made up of concentric circles of various colours and the most valuable of these stones are found in the East Indies. The gem is used for rings, seals and, in the East; drinking vessels.

Chodchod

Chodchod, ''kdkd'' (Is., liv, 12; Ezech., xxvii, 16); Sept.''iaspis'' (Is., liv, 12), ''chorchor'' (Ezech., xxvii, 16); Vulg.''jaspis'' (Is., liv, 12), ''chodchod'' (Ezech., xvii, 16). This word is used only twice in the Bible. Chodchod is generally identified with the Oriental ruby. The translation of the word in Is. both by the Septuagint and the Vulgate is ''jasper''; in Ezech. the word is merely transliterated; the Greek ''chorchor'' is explained by considering how easy it is to mistake aresh

Resh is the twentieth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Rēsh , Hebrew Rēsh , Aramaic Rēsh , Syriac Rēsh ܪ, and Arabic . Its sound value is one of a number of rhotic consonants: usually or , but also or in Hebrew and No ...

for a daleth

Dalet (, also spelled Daleth or Daled) is the fourth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Dālet 𐤃, Hebrew Dālet , Aramaic Dālath , Syriac Dālaṯ , and Arabic (in abjadi order; 8th in modern order). Its sound value ...

.

"What chodchod signifies", says St. Jerome, "I have until now not been able to find" (Comment. in Ezech., xxvii, 16, in P. L., XXV, 255). In Is. he follows the Septuagint and translates chodchod by ''jaspis''. The word is probably derived from ''phyr'', "to throw fire"; the stone was therefore brilliant and very likely red. This supposition is strengthened by the fact that the Arabic word ''kadzkadzat'', evidently derived from the same stem as chodchod, designates a bright red. It was therefore a kind of ruby, likely the Oriental ruby, perhaps also the carbuncle (see above).

Chrysolite

Zebulun

Zebulun (; also ''Zebulon'', ''Zabulon'', or ''Zaboules'') was, according to the Books of Genesis and Numbers,Genesis 46:14 the last of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's tenth son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Zebulun. Som ...

; it stands fourth in the enumeration of Ezech., xxviii, 13, and is given as the seventh foundation stone of the celestial city in Apoc., xxi, 20.

None of the Hebrew texts give any hint as to the nature of this stone. However, since the Septuagint repeatedly translates the Hebrew word by ''chrysolithos'', except where it merely transliterates it, and in Ezech., x, 9, since, moreover, the Vulgate follows this translation with very few exceptions, and Aquila, Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

, and St. Epiphanius agree in their rendering, it can be assumed that the ''chrysolite'' of the ancients equates to our topaz.

The word ''tharsis'' very likely points to the origin of the gem (Tarshish

Tarshish ( Phoenician: ''TRŠŠ'', he, תַּרְשִׁישׁ ''Taršīš'', , ''Tharseis'') occurs in the Hebrew Bible with several uncertain meanings, most frequently as a place (probably a large city or region) far across the sea from Phoen ...

). The modern chrysolite is a green oblong hexagonal prism of unequal sides terminated by two triangular pyramids. Topaz, or ancient chrysolite, is an octangular prism of an orange-yellow colour; it is composed of alumina, silica, hydrofluoric acid, and iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

. it is found in Ceylon, Arabia, and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

. Several species were reported to exist (Pliny, "Hist. nat.", XXXVII, xlv) and during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

it was believed to possess the power of relieving anxiety at night, driving away devils and to be an excellent cure for eye diseases.

Chrysoprase

Chrysoprase

Chrysoprase, chrysophrase or chrysoprasus is a gemstone variety of chalcedony (a cryptocrystalline form of silica) that contains small quantities of nickel. Its color is normally apple-green, but varies to deep green. The darker varieties of chry ...

, Greek ''chrysoprasos'', the tenth foundation stone of the celestial Jerusalem (Apoc., xxi, 20). This is perhaps the agate of Ex., xxviii, 20, and xxxix, 13, since the chrysoprasus was not very well known among the ancients. It is a type of green agate, composed mostly of silica and a small percentage of nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

.

Coral

Coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and ...

, Heb. ''ramwt'' (Job, xxviii, 18; Prov., xxiv, 7; Ezech., xxvii, 16); Sept. ''meteora'', ''ramoth''; Vulg. ''excelsa'', ''sericum''. The Hebrew word seems to derive from ''tas'', "to be high", probably pertaining to a tree. Another possibility is that the name originates from a strange country, as did the coral itself. It is apparent that the ancient

versions have been prone to mis-interpretation. In one instance they even went so far as to

simply transliterate the Hebrew word.

In Ezech., xxvii, 16, coral is mentioned as one of the articles brought by the Syrians to Tyre. The Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

mounted beads of coral on collars and garments. These corals were obtained by Babylonian pearl-flshers in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

and the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

. The Hebrews apparently made very little use of this substance, and it is seldom mentioned in their writings. This also explains the difficulty experienced in scriptural translation.

Gesenius (Thesaurus, p. 1113) translates ''phnynys'' (Job, xxviii, 18; Prov., iii, 15; viii, 11; xx, 15; xxxi, 10; Lam., iv, 7) as "red coral". However, pearl has also been interpreted to be the meaning in these passages. The coral referred to in the Bible is the precious coral (''corallium rubrum

Precious coral, or red coral, is the common name given to a genus of marine corals, ''Corallium''. The distinguishing characteristic of precious corals is their durable and intensely colored red or pink-orange skeleton, which is used for m ...

''), the formation of which is well known. It is a calcareous secretion of certain polyps resulting in a tree-like formation. Presently coral is found in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

, the northern coast of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

furnishing the dark red, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

the yellow or salmon-coloured, and the coast of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

the rose-pink coral. One of the greatest coral-fisheries of the present day is Torre del Greco

Torre del Greco (; nap, Torre d' 'o Grieco; "Greek man's Tower") is a ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Naples in Italy, with a population of c. 85,000 . The locals are sometimes called ''Corallini'' because of the once plentiful cora ...

, near Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

.

Crystal

Crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macro ...

, Heb. ''ghbsh'' (Job, xxviii, 18), ''qrh'' (Ezech, i, 22): both words signify a glassy substance; Sept. ''gabis''; Vulg. ''eminentia'' (Job, xxviii, 18); ''krystallos'', ''crystallus'' (Ezech., i, 22). Crystal is a transparent mineral resembling glass, most probably a variety of quartz. Job places it in the same category with gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

, onyx, sapphire, glass, coral, topaz, etc. The Targum renders the ''qrt'' of

Ezech. as "ice"; the other versions translate it as "crystal". Crystal is again mentioned in Apoc., iv, 6; xxi, 11; xxii, 1. In Ps. cxlvii, 17, and Ecclus., xliii, 22, there can be no question that ice is indicated. The word ''zkwkyh'', Job, xxviii, 17, which can be translated as crystal, means glass.

Diamond

Diamond

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, ...

, Heb. ''shmyr''; Sept. ''adamantinos''; Vulg. ''adamas'', ''adamantinus'' (Ezech., iii, 9; Zach., vii, 12; Jer, xvii 1). Whether or not this stone is really diamond cannot be established. Many passages in Holy Scriptures point to the qualities of diamond, in particular to its hardness (Ezech., iii, 9; Zach., vii, 12; Jer., xvii, 1). In the last citation

Jeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, Ἰερεμίας, Ieremíās; meaning " Yah shall raise" (c. 650 – c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewi ...

informs us of a diamond usage which is much the same as its usage today: "The sin of Juda is written with a pen of iron, with the point of a diamond". However, although diamond is used to engrave

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an in ...

hard substances, other stones can serve the same purpose.

The Septuagint omits the passages of Ezech. and Zach., while the first five verses of Jer., xvii, are missing in the Cod. Vaticanus and Alexandrinus, but are found in the Complutensian edition and in the Syriac and Arabic Versions. Despite the qualities mentioned in the Bible, the stone referred to may be the limpid corindon, which exhibits the same qualities, and is used in India for the same purposes as the diamond.

Diamond was not very well known among the ancients; and if we add to this the etymological similarity between the words ''smiris'', the Egyptian ''asmir'', "emery", a species of corindon used to polish gemstones, and ''shmyr'', the Hebrew word supposed to mean diamond; the conclusion to be drawn is that limpid corindon was intended.

Aben-Esra and Abarbanel translate ''yhlm'' as "diamond"; but ''yhlm'' was demonstrated above to be beryl. Diamond is made up of pure carbon, mostly of a white transparent colour, but sometimes tinted. White diamond is often regarded as the most precious because of its beauty and rarity.

Emerald

Emerald, Heb. ''brqm''; Sept. ''smaragdos''; Vulg. ''smaragdus''; the third stone of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 10), representing the tribe ofLevi

Levi (; ) was, according to the Book of Genesis, the third of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's third son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Levi (the Levites, including the Kohanim) and the great-grandfather of Aaron, Moses and ...

; it is the ninth stone in Ezech., xxviii,13, and the fourth foundation stone of the celestial Jerusalem (Apoc., xxi, 19). The same stone is also mentioned in Tob., xiii, 16 (Vulg. 21); Jud., x, 21 (Vulg. 19); and in the Greek text of Ecclus., xxxii, 8, but there is no indication of it in the Manuscript B. of the Hebrew text, found in the Genizah of Cairo in 1896.

Practically all versions, including Josephus (Ant. Jud., III, vii, 5; Bell. Jud., V, v, 7) translate ''brhm'' as "emerald". The Hebrew root ''brq'' (to glitter"), from which it is probably derived, is agreed on by scholastic consensus. The word may also derive from the Sanskrit ''marakata'' which is certainly emerald nor is the Greek form ''smaragdos'' that different either. In Job, xiii, 21; Jud., x, 19; Ecclus., xxxii, 8; and Apoc., xxi, 19, the emerald is certainly the stone referred to. The word ''bphr'' also has sometimes been translated by ''smaragdus'' but this is a mistake as ''bphr'' signifies carbuncle.

Emerald is a green variety of beryl and is composed of silicate of alumina and glucina. Structurally, it is a hexagonal crystal with a brilliant reflecting green colour. The emerald is highly polished and is found in metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock ( protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, caus ...

s, granites

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

, and mica schist. Many of the finest specimens have been found in Muzo

Muzo () is a town and municipality in the Western Boyacá Province, part of the department of Boyacá, Colombia. It is widely known as the world capital of emeralds for the mines containing the world's highest quality gems of this type. Muzo ...

, Bogota, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

but the ancients obtained the stone from Egypt and India.

Although claims have been made that the ancients knew nothing of the emerald - Pliny, Theophrastus and others clearly refute this even though the name may have been used possibly for other stones. In the Middle Ages miraculous healing powers were attributed to the emerald, among them; the power to preserve or heal visual problems.

Jacinth

Hyacinth

Hyacinth or Hyacinthus may refer to:

Nature Plants

* Hyacinth (plant), genus ''Hyacinthus''

** '' Hyacinthus orientalis'', common hyacinth

* Grape hyacinth, '' Muscari'', a genus of perennial bulbous plants native to Eurasia

* Hyacinth bean, ''L ...

, Greek ''hyakinthos''; Vulg. ''hyacinthus'' (Apoc., xxi, 20); the eleventh stone of the foundation of the heavenly city. It is probably equated with Heb., the ''ligurius'' of Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12 (St. Epiphan., "''De duodecim gemmis''" in P. G., XLIII, 300). The stone referred to in Cant., v, 14, and called ''hyacinthus'' in the Vulgate is the Hebrew ''shoham'', which has been shown above to be chrysolite. The exact nature of hyacinth cannot be determined as the name was applied to several stones of similar colours and most probably designated stones reminiscent of the hyacinth flower.

Exodus xxviii:19, xxxix:12

Hyacinth is a zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

of a crimson, red, or orange colour. It is harder than quartz and its cleavage is undulating and sometimes lamellated. Its form is that of an oblong quadrangular prism terminated on both ends by a quadrangular pyramid. It was allegedly used as a talisman

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed perm ...

against tempests.

Jasper

Jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases,Kostov, R. I. 2010. Review on the mineralogical systematics of jasper and related rocks. – Archaeometry Workshop, 7, 3, 209-213PDF/ref> ...

Heb. יָשְׁפֵ֑ה ''yashpeh''; Sept. ''iaspis''; Vulg. ''jaspis''; the twelfth stone of the breastplate (Ex., xxviii, 18; xxxix, 11), representing Benjamin. In the Greek and Latin texts it comes sixth, and so also in Ezech., xxviii, 13; in the Apocalypse it is the first (xxi, 19). Despite this difference of position ''jaspis'' is undoubtedly the ''yshphh'' of the Hebrew text. The gem is an anhydrate quartz composed of silica, alumina, and iron and there are jaspers of nearly every colour. It is a completely opaque stone of a conchoidal cleavage. It seems to have been obtained by the Jews from India and Egypt.

Ligurus

Ligurus, Heb. ''lshs''; Sept. ''ligyrion''; Vulg. ''ligurius''; the first stone of the third row of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12), representing Gad. It is missing in the Hebrew of Ezech., xxviii, 13, but present in the Greek. This stone is probably the same as hyacinth (St. Epiphan., loc. cit.). This traditional identification, is based upon

the remark that the twelve foundation stones of the celestial city in Apoc., xxi, 19-20, correspond to the twelve stones of the rational. This alone is enough to equate ligurus with hyacinth although it has been identified with

Ligurus, Heb. ''lshs''; Sept. ''ligyrion''; Vulg. ''ligurius''; the first stone of the third row of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 12), representing Gad. It is missing in the Hebrew of Ezech., xxviii, 13, but present in the Greek. This stone is probably the same as hyacinth (St. Epiphan., loc. cit.). This traditional identification, is based upon

the remark that the twelve foundation stones of the celestial city in Apoc., xxi, 19-20, correspond to the twelve stones of the rational. This alone is enough to equate ligurus with hyacinth although it has been identified with tourmaline

Tourmaline ( ) is a crystalline silicate mineral group in which boron is compounded with elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. Tourmaline is a gemstone and can be found in a wide variety of colors.

The te ...

; though the latter view is rejected by most scholars.

Onyx

Onyx

Onyx primarily refers to the parallel banded variety of chalcedony, a silicate mineral. Agate and onyx are both varieties of layered chalcedony that differ only in the form of the bands: agate has curved bands and onyx has parallel bands. The ...

, Lat; Sept. ''onychion''; Vulg. ''lapis onychinus''; the eleventh stone of the breastplate in the Hebrew and the Vulgate (Ex., xxviii, 20; xxxix, 13), representing the tribe of Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

. In the Sept. it is the twelfth stone and the fifth in Ezech., xxviii, 13, in the Heb., but the twelfth in the Greek; it is called ''sardonyx'' and comes in the fifth place in Apoc., xxi, 20.

The exact nature of this stone is disputed because the Greek word ''beryllos'' occurs instead of the Hebrew ''???'' thereby indicating beryl. However, this is not so (see Beryl above).

The Vulgate equates onyx with the Hebrew ''??? '' and although this alone would be a very weak argument; there are other, stronger testimonies to the fact that the Hebrew word occurs frequently in Holy Scripture: (Gen., ii, 12; Ex., xxv, 7; xxv, 9, 27; I Par., xxxix, 2; etc.) and on each occasion, except Job, xxviii, 16, the gem is translated in the Vulgate by ''lapis onychinus'' (''lapis sardonychus'' in Job, xxviii, 16).

The Greek is very inconsistent in its translation, rendering ''shhs'' differently in various texts; therefore in Gen., ii, 12, it is ''lithos prasinos'', ''sardios'' in Ex. xxv, 7; xxxv, 9;

''smaragdos'' in Ex., xxviii, 9; xxxv, 27; xxxix, 6; ''soam'', a mere transcription of the Hebrew word in I Par., xxix, 2; and onyx in Job, xxviii, 16.

Other Greek translators are more consistent: Aquila has ''sardonyx'' and Symmachus and Theodotion

Theodotion (; grc-gre, Θεοδοτίων, ''gen''.: Θεοδοτίωνος; died c. 200) was a Hellenistic Jewish scholar, perhaps working in Ephesus, who in c. 150 CE translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek. Whether he was revising the Septua ...

have onyx. The paraphrase of Onkelos

Onkelos ( he, אֻנְקְלוֹס ''ʾunqəlōs''), possibly identical to Aquila of Sinope, was a Roman national who converted to Judaism in Tannaic times ( 35–120 CE). He is considered to be the author of the Targum Onkelos ( 110 C ...

had ''burla'', the Syriac ''berula'', both of which evidently are the Greek ''beryllos''; "beryl". Since the translations do not observe the same order as the Hebrew in enumerating the stones of the rational (see Beryl above), it is not mandatory to accept the Greek ''beryllos'' as the translation of ''shhm''. Therefore, relying on the testimony of the various versions it can safely be assumed that onyx is the stone signified by ''shhm''.

Onyx is a variety of quartz analogous to agate and other crypto-crystalline species. It is composed of different layers of variously coloured carnelian much like banded agate in structure, but the layers are in even or parallel planes. This makes it well adapted for the cutting of cameos and was much used by the ancients for that purpose. The colours of the best are perfectly well defined, and are either white and black, or white, brown, and

black. Some of the best specimens have been brought from India.

Pearl

Pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...

. Although not a gemstone in the strictest sense, we can apply the word "stone" in a broader context similar to that of coral. It is comparatively certain that pearl (Greek

''margarite'', Vulg. ''margarita'') was known among the Jews, at least after the time of Solomon, as it was among the Phoenicians. The exact etymology is uncertain, but the following have been suggested: ''ghbysh'', which signified "crystal" (see above); ''phnynym'', which Gesenius renders by "red coral"; ''dr'', Esth., i, 6, which is translated in the Vulg. by ''lapis parius'', "marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

"; the Arabic ''dar'' also signifies "pearl", and therefore Furst also renders the Hebrew word.

In the New Testament we find pearl mentioned in Matt., xiii, 45, 46; I Tim., ii, 9; etc. Pearl is a concretion consisting chiefly of lime carbonate found in several bivalve molluscs

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is estim ...

, but especially in ''avicula margaritifera''. Generally, it has a whitish blue hue, sometimes showing a tinge of pink; but there are also yellow pearls. This gem was considered the most precious of all among the ancients, and was obtained from the Red Sea,

the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf.

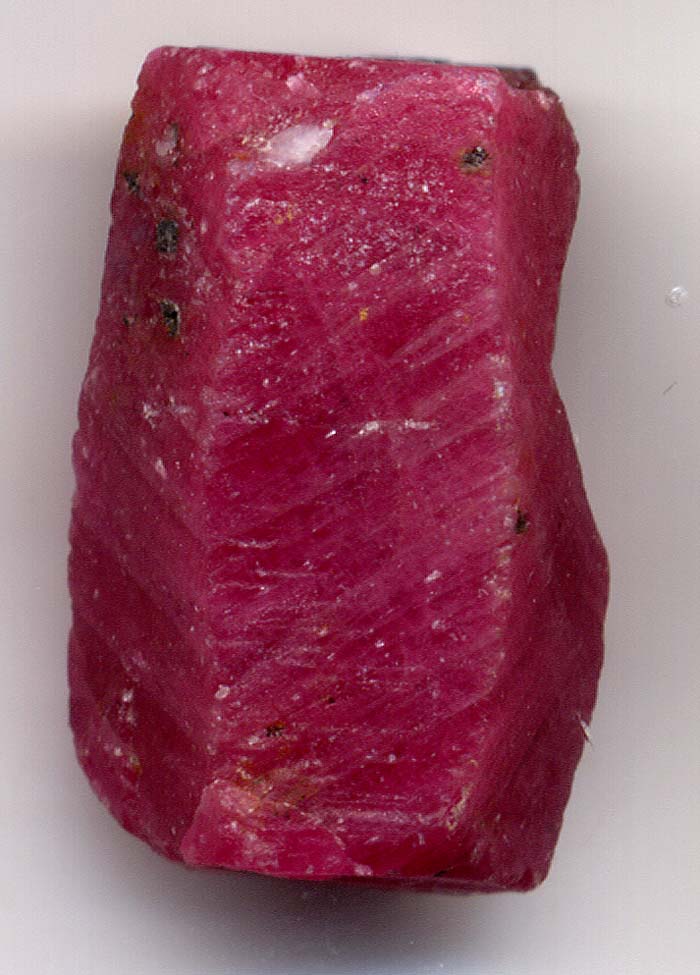

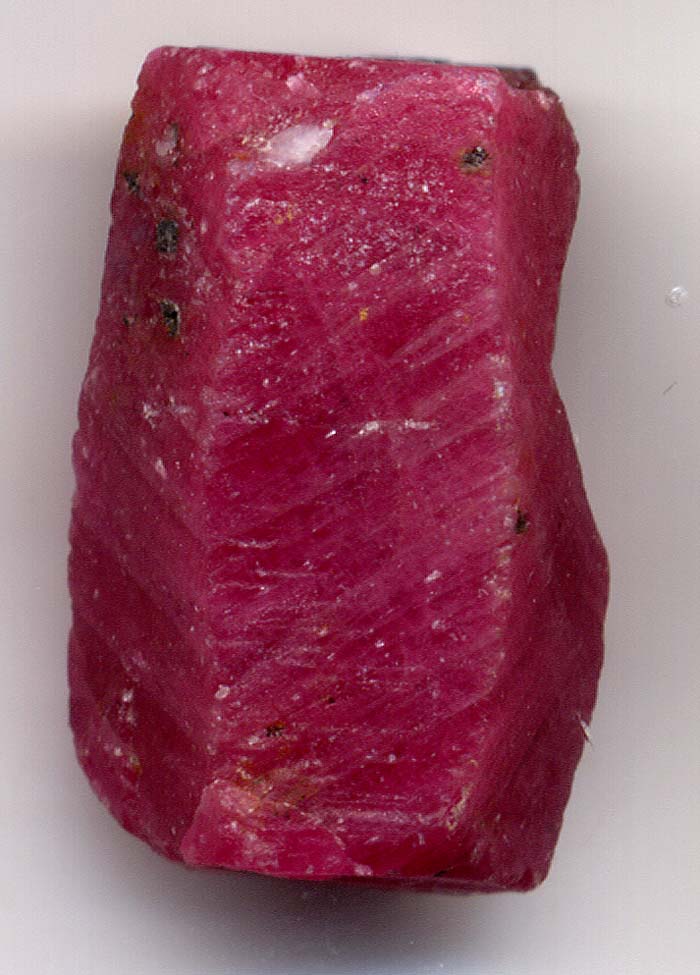

Ruby

Ruby

A ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum ( aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called ...

. This stone may have been either the carbuncle or the chodchod (see above). There is, however, a choice between the oriental ruby and the spinel ruby; but the words may have been used interchangeably for both. The former is extremely hard, almost as hard as diamond, and is obtained from Ceylon, India, and China. It is considered one of the most precious gems.

Sapphire

Sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, or magnesium. The name sapphire is derived via the Latin "sa ...

, Heb. ''mghry'' Septuag. ''sappheiron''; Vulg. ''sapphirus''. Sapphire was the fifth stone of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 19; xxxix, 13), and represented the tribe of Issachar

Issachar () was, according to the Book of Genesis, the fifth of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's ninth son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Issachar. However, some Biblical scholars view this as an eponymous metaphor providing ...

. It is the seventh stone in Ezech., xxviii, 14 (in the Hebrew text, for it occurs fifth in the Greek text); it is also the second foundation stone of the celestial Jerusalem (Apoc., xxi, 19).

The genuine sapphire is a beautiful blue hyaline corindon and is composed of nearly pure alumina, its colour resulting from the presence of iron oxide. The ancients also referred to lapis-lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mine ...

as sapphire, which is likewise a blue stone, often speckled with shining

pyrites

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

giving it the appearance of being sprinkled with gold dust. It is composed of silica, alumina, and alkali and is an opaque substance easily engraved. Debate still continues as to which stone is precisely referred to in the Bible. Both may be meant, but lapis-lazuli seems more probable as its qualities are better suited for the purposes of engraving (Lam., iv, 7; Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 13). Sapphire was obtained from India.

Sard

Sard

is a Japanese tuning company and racing team from Toyota, Aichi, mainly competing in the Super GT series and specialising in Toyota tuning parts.

History

The company was formed in 1972 as Sigma Automotive Co., Ltd by Shin Kato to develop and ...

and sardonyx are often confused by interpreters. Sard is carnelian

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semi-precious gemstone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker (the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often used ...

, while sardonyx is a species of onyx.

Sardonyx

Sardonyx

Onyx primarily refers to the parallel banded variety of chalcedony, a silicate mineral. Agate and onyx are both varieties of layered chalcedony that differ only in the form of the bands: agate has curved bands and onyx has parallel bands. The c ...

has a structure similar to onyx, but is usually composed of alternate layers of white chalcedony and carnelian, although carnelian may be associated with layers of white, brown, and black chalcedony. The ancients obtained onyx from Arabia, Egypt, and India.

Topaz

Topaz, Heb. ''ghtrh''; Sept. ''topazion''; Vulg. ''topazius'', the second stone of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 19), representing

Topaz, Heb. ''ghtrh''; Sept. ''topazion''; Vulg. ''topazius'', the second stone of the rational (Ex., xxviii, 17; xxxix, 19), representing Simeon

Simeon () is a given name, from the Hebrew (Biblical ''Šimʿon'', Tiberian ''Šimʿôn''), usually transliterated as Shimon. In Greek it is written Συμεών, hence the Latinized spelling Symeon.

Meaning

The name is derived from Simeon, so ...

; also the second stone in Ezech., xxviii, 13; the ninth foundation stone of the celestial Jerusalem (Apoc., xxi, 20) and also mentioned in Job, xxviii, 19.

This topaz is generally believed to have been chrysolite rather than the more generally known topaz. Oriental topaz is composed of nearly pure alumina, silica, and fluoric acid; its shape is an orthorhombic prism with a cleavage transverse to its long axis. It is extremely hard and has a double refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenome ...

. When rubbed or heated it becomes highly electric

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by ...

.

It varies in colour according to the country of origin. Australian topaz is green or yellow; the Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

n clear, bright, and transparent; the Saxon pale violet; the Bohemian sea-green and the Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

ian red, varying from a pale red to a deep carmine. The ancients very probably obtained it from the East.

See also

* Priestly breastplateReferences

Further reading

;Attribution * The entry cites: **ST. EPIPHANIUS, De duodecim qemmis in ''Patrologia Graeca

The ''Patrologia Graeca'' (or ''Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Graeca'') is an edited collection of writings by the Christian Church Fathers and various secular writers, in the Greek language. It consists of 161 volumes produced in 1857– ...

'', XLIII, 294-304;

**ST. ISIDORE, De lapidibus in Etymol., xvi, 6-15, in '' Patrologia Latina'', LXXXII, 570-580;

**Charles William King

Charles William King (5 September 1818 – 25 March 1888) was a British Victorian writer and collector of gems.

Early life

King was born in Newport, Monmouthshire, and entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1836. He graduated in 1840, and ob ...

, ''Antique Gems'' (2d ed., London, 1872);

**—, ''The Natural History of Gems or Decorative Stones'' (2d ed., London, 1870);

**BRAUN, Vestitus sacerdotum hebræorum (Leyden, 1680);

**BABELON in DAREMBERG AND SAGLIO, Dict. des antiquités grecques et romaines, s.v. Gemmæ;

**LESÉTRE in VIGOUROUX, Dict. de la Bible, s.v. Pierres précieuses;

**ROSENMÜLLER, Handbuch der biblischen Alterthumskunde (Leipzig);

**WINER in Biblisches Realwörterbuch (Leipzig, 1847), s.v. Edelstine.

{{DEFAULTSORT:gemstones in the Bible, List of

Biblical topics

Gemstones in religion