Gaucho Tradition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay,

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay,

A different approach is to consider that the word might have originated north of the Río de la Plata, where the indigenous languages were quite different and there is a Portuguese influence.

Two facts that any theory could usefully account for are:

* The word actually exists in two forms: Port. ''gaúcho'' and Sp. ''gaucho'', both long attested.

* Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the Spanish colonial records for present-day Uruguay, often in connection with smuggling to Brazil (see below, Origins). Thus Azara wrote (around 1784):

Hence the Uruguayan

A different approach is to consider that the word might have originated north of the Río de la Plata, where the indigenous languages were quite different and there is a Portuguese influence.

Two facts that any theory could usefully account for are:

* The word actually exists in two forms: Port. ''gaúcho'' and Sp. ''gaucho'', both long attested.

* Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the Spanish colonial records for present-day Uruguay, often in connection with smuggling to Brazil (see below, Origins). Thus Azara wrote (around 1784):

Hence the Uruguayan  As to that, Rona thought that ''gaúcho'' originated in northern Uruguay, and came from ''garrucho'', a derisive word possibly of Charrua origin, which meant something like "old indian" or "contemptible person", and is actually found in the historical record. However in the Portuguese-based dialects of northern Uruguay the phoneme /rr/ is not easily pronounced, and so is rendered as /h/ (sounding rather like English h). Thus ''garrucho'' would be rendered as ''gahucho'', and indeed the French naturalist

As to that, Rona thought that ''gaúcho'' originated in northern Uruguay, and came from ''garrucho'', a derisive word possibly of Charrua origin, which meant something like "old indian" or "contemptible person", and is actually found in the historical record. However in the Portuguese-based dialects of northern Uruguay the phoneme /rr/ is not easily pronounced, and so is rendered as /h/ (sounding rather like English h). Thus ''garrucho'' would be rendered as ''gahucho'', and indeed the French naturalist

The original gaucho was typically descended from unions between Iberian men and Amerindian women, although he might also have African ancestry. A DNA analysis study of rural inhabitants of

The original gaucho was typically descended from unions between Iberian men and Amerindian women, although he might also have African ancestry. A DNA analysis study of rural inhabitants of

Vidal also painted visiting gauchos from up-country Tucumán. ("Their features are particularly Spanish, uncrossed by that mixture observable in the citizens of Buenos Ayres"). They are not horsemen: they are oxcart drivers, and may or may not have called themselves gauchos in their home province.

Charles Darwin observed life on the pampas for six months and reflected in his diary (1833):

Vidal also painted visiting gauchos from up-country Tucumán. ("Their features are particularly Spanish, uncrossed by that mixture observable in the citizens of Buenos Ayres"). They are not horsemen: they are oxcart drivers, and may or may not have called themselves gauchos in their home province.

Charles Darwin observed life on the pampas for six months and reflected in his diary (1833):

Brazilian inheritance laws compelled landowners to leave their lands in equal shares to their sons and daughters, and since they were numerous, and those laws were hard to evade, great landholdings fractured in a few generations. There were not the huge cattle estates of Buenos Aires province where, as an extreme example, the Anchorena family owned in 1864.

Unlike Argentina, cattlemen in Rio Grande do Sul did not have vagrancy laws to tie gaúchos to their ranches. However, slavery was legal in Brazil; in Rio Grande do Sul it existed until 1884; and perhaps a majority of permanent ranch workers were enslaved. Thus many horse-riding ''campeiros'' (cowboys) were black slaves. They enjoyed sharply better living conditions than the slaves who worked in the brutal ''xarqueadas'' (beef-salting plants). John Charles Chasteen explained why:

Brazilian inheritance laws compelled landowners to leave their lands in equal shares to their sons and daughters, and since they were numerous, and those laws were hard to evade, great landholdings fractured in a few generations. There were not the huge cattle estates of Buenos Aires province where, as an extreme example, the Anchorena family owned in 1864.

Unlike Argentina, cattlemen in Rio Grande do Sul did not have vagrancy laws to tie gaúchos to their ranches. However, slavery was legal in Brazil; in Rio Grande do Sul it existed until 1884; and perhaps a majority of permanent ranch workers were enslaved. Thus many horse-riding ''campeiros'' (cowboys) were black slaves. They enjoyed sharply better living conditions than the slaves who worked in the brutal ''xarqueadas'' (beef-salting plants). John Charles Chasteen explained why: Land-hungry Rio Grande cattlemen bought up estates cheaply in neighbouring Uruguay until they owned about 30% of that country, which they ranched with their slaves and cattle. The border area was fluid, bilingual and lawless. Though slavery was abolished in Uruguay in 1846, and there were laws against human trafficking, weak governments poorly enforced those laws. Often Brazilian ranchers simply ignored them, even crossing and re-crossing the border with their slaves and cattle. An 1851 extradition treaty required Uruguay to return fugitive Brazilian slaves.

Governments found it hard to establish a monopoly of violence in the border area. In the Federalist Revolution of 1893 gaúcho-manned armies led by elite families fought each other with exceptional barbarity. Powerful Brazilian-Uruguayan families, like the Saraivas, led mounted insurrections in both countries, even in the 20th century. In the satirical cartoon (1904)

Land-hungry Rio Grande cattlemen bought up estates cheaply in neighbouring Uruguay until they owned about 30% of that country, which they ranched with their slaves and cattle. The border area was fluid, bilingual and lawless. Though slavery was abolished in Uruguay in 1846, and there were laws against human trafficking, weak governments poorly enforced those laws. Often Brazilian ranchers simply ignored them, even crossing and re-crossing the border with their slaves and cattle. An 1851 extradition treaty required Uruguay to return fugitive Brazilian slaves.

Governments found it hard to establish a monopoly of violence in the border area. In the Federalist Revolution of 1893 gaúcho-manned armies led by elite families fought each other with exceptional barbarity. Powerful Brazilian-Uruguayan families, like the Saraivas, led mounted insurrections in both countries, even in the 20th century. In the satirical cartoon (1904)

Once political stability was achieved the results were dramatic. From around 1875 a flood of immigrants altered the country's ethnic composition. In 1914, 40% of Argentina's residents were foreign-born. Today, Italian surnames are more common than Spanish.

Barbed wire, cheap from 1876, fenced the pampa "and thus eliminated the need for gaucho cowboys". Gauchos were forced off the land, drifting into rural towns to look for work, though a few were retained as peon labourers. Cunninghame Graham, after whom a Buenos Aires street is named, and who had lived as a gaucho in the 1870s, returned in 1914 to "his first love, Argentina" and found it had greatly changed. "Progress, which he constantly lambasted, had rendered the gaucho virtually extinct".

Wote S. Samuel Trifilo (1964): "The gaucho of today working on the pampas of Argentina is no more a real gaucho than is our own present-day cowboy the cowboy of the Wild West; both have gone forever."

Two-thirds of Uruguay lies south of the Río Negro, and this part was fenced most intensively in the decade 1870-1880. The gaucho was marginalised and was frequently driven to live in ''pueblos de ratas'' (rural slums, literally rat towns).

North of the Río Negro mobile gauchos survived rather longer. A Scottish anthropologist in the central region (1882) saw many of them as unsettled. European immigration to the countryside was smaller. The central government failed to consolidate its power over the countryside, and gaucho-manned armies continued to defy it until 1904. The turbulent gaucho leaders e.g. the Saravias had connections with the cattlemen over the Brazilian border, where there was much less European immigration; Wire fences did not become common in the borderland until the close of the 19th century.

The revolutionary battles in Brazil ended by 1930 under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, who disarmed the private gaúcho armies and prohibited the carrying of guns in public.

Once political stability was achieved the results were dramatic. From around 1875 a flood of immigrants altered the country's ethnic composition. In 1914, 40% of Argentina's residents were foreign-born. Today, Italian surnames are more common than Spanish.

Barbed wire, cheap from 1876, fenced the pampa "and thus eliminated the need for gaucho cowboys". Gauchos were forced off the land, drifting into rural towns to look for work, though a few were retained as peon labourers. Cunninghame Graham, after whom a Buenos Aires street is named, and who had lived as a gaucho in the 1870s, returned in 1914 to "his first love, Argentina" and found it had greatly changed. "Progress, which he constantly lambasted, had rendered the gaucho virtually extinct".

Wote S. Samuel Trifilo (1964): "The gaucho of today working on the pampas of Argentina is no more a real gaucho than is our own present-day cowboy the cowboy of the Wild West; both have gone forever."

Two-thirds of Uruguay lies south of the Río Negro, and this part was fenced most intensively in the decade 1870-1880. The gaucho was marginalised and was frequently driven to live in ''pueblos de ratas'' (rural slums, literally rat towns).

North of the Río Negro mobile gauchos survived rather longer. A Scottish anthropologist in the central region (1882) saw many of them as unsettled. European immigration to the countryside was smaller. The central government failed to consolidate its power over the countryside, and gaucho-manned armies continued to defy it until 1904. The turbulent gaucho leaders e.g. the Saravias had connections with the cattlemen over the Brazilian border, where there was much less European immigration; Wire fences did not become common in the borderland until the close of the 19th century.

The revolutionary battles in Brazil ended by 1930 under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, who disarmed the private gaúcho armies and prohibited the carrying of guns in public.

For Lugones (1913), to discern a people's true character, one had to read its epic poetry; and '' Martín Fierro'' was the Argentine epic poem ''par excellence''. Far from being a barbarian, the gaucho was the hero who did what the Spanish Empire could not — civilise the pampa by subjugating the Indian. To be a gaucho demanded "composure, courage, ingenuity, meditation, sobriety, vigour; all this made him a free man". But in that case, asked Lugones, why did the gaucho disappear? Because, together with his virtues, he had inherited two defects from his Indian and Spanish ancestors: laziness and pessimism.

Lugones' lectures, where he canonised ''Martín Fierro'' with its quarreling gaucho protagonist, had official support: the president of the Republic and his cabinet attended them, as did prominent members of the traditional ruling classes.

However, wrote a Mexican scholar, in exalting this gaucho Lugones and others were not recreating a real historical character, they were weaving a nationalist myth, for political purposes. Jorge Luis Borges thought their choice of gaucho was a poor

For Lugones (1913), to discern a people's true character, one had to read its epic poetry; and '' Martín Fierro'' was the Argentine epic poem ''par excellence''. Far from being a barbarian, the gaucho was the hero who did what the Spanish Empire could not — civilise the pampa by subjugating the Indian. To be a gaucho demanded "composure, courage, ingenuity, meditation, sobriety, vigour; all this made him a free man". But in that case, asked Lugones, why did the gaucho disappear? Because, together with his virtues, he had inherited two defects from his Indian and Spanish ancestors: laziness and pessimism.

Lugones' lectures, where he canonised ''Martín Fierro'' with its quarreling gaucho protagonist, had official support: the president of the Republic and his cabinet attended them, as did prominent members of the traditional ruling classes.

However, wrote a Mexican scholar, in exalting this gaucho Lugones and others were not recreating a real historical character, they were weaving a nationalist myth, for political purposes. Jorge Luis Borges thought their choice of gaucho was a poor

In Rio Grande do Sul the gaúcho has been mythified too, not in reaction to massive immigration as in Argentina, but to give the state a regional identity. The main celebration is the ''Semana Farroupilha'', a week of festivities, mass horseback parades, ''

In Rio Grande do Sul the gaúcho has been mythified too, not in reaction to massive immigration as in Argentina, but to give the state a regional identity. The main celebration is the ''Semana Farroupilha'', a week of festivities, mass horseback parades, ''

Richard W. Slatta collected instances of extreme equestrian sports practised by 19th century gauchos. To perform these required and developed skills and courage that helped gauchos to survive on the pampas.

*Crowding. Two men would spur their horses to shove against each other, each man's object being to drive his opponent to a particular place. In a variant, they raced along a narrow track; if one man could crowd the other off it, he won.

*''Cinchada''. An equestrian tug-of-war, tail to tail; the rope was tied to their saddles. "This contest grew out of the need for mounts strong enough to pull against a wild, lassoed steer".

*''Pechando''. Two horsemen galloping at full speed charged each other head on. The shock of the collision tumbled the men and perhaps the horses. The object was to recover and charge again and again until prevented by exhaustion or injury. "Pechando provided an opportunity for a gaucho to exhibit his courage and indifference to death or injury."

*Jumping the bar. A bar was placed above a corral gate with just enough headroom for a horse to pass. A gaucho galloped through, and as he did, he jumped over the bar and landed back in the saddle.

*''Maroma''. A variant in which the gaucho jumped from the bar onto the back of a racing wild horse or wild steer. He had to stay on until the horse was broken or the steer was killed.

*Recado. The horseman galloped across the pampa while he undid his ''recado'' (a multi-layered saddle), dropping the pieces as he went. He had to go back, snatch up the pieces and reassemble his saddle, all the time riding at full speed.

*''Pialar'', a particularly dangerous sport. One man galloped through a group of gauchos who lassoed his horse's legs. This threw the horse, but the man had to land on his feet holding the reins. This skill was useful for survival because the pampa was riddled with

Richard W. Slatta collected instances of extreme equestrian sports practised by 19th century gauchos. To perform these required and developed skills and courage that helped gauchos to survive on the pampas.

*Crowding. Two men would spur their horses to shove against each other, each man's object being to drive his opponent to a particular place. In a variant, they raced along a narrow track; if one man could crowd the other off it, he won.

*''Cinchada''. An equestrian tug-of-war, tail to tail; the rope was tied to their saddles. "This contest grew out of the need for mounts strong enough to pull against a wild, lassoed steer".

*''Pechando''. Two horsemen galloping at full speed charged each other head on. The shock of the collision tumbled the men and perhaps the horses. The object was to recover and charge again and again until prevented by exhaustion or injury. "Pechando provided an opportunity for a gaucho to exhibit his courage and indifference to death or injury."

*Jumping the bar. A bar was placed above a corral gate with just enough headroom for a horse to pass. A gaucho galloped through, and as he did, he jumped over the bar and landed back in the saddle.

*''Maroma''. A variant in which the gaucho jumped from the bar onto the back of a racing wild horse or wild steer. He had to stay on until the horse was broken or the steer was killed.

*Recado. The horseman galloped across the pampa while he undid his ''recado'' (a multi-layered saddle), dropping the pieces as he went. He had to go back, snatch up the pieces and reassemble his saddle, all the time riding at full speed.

*''Pialar'', a particularly dangerous sport. One man galloped through a group of gauchos who lassoed his horse's legs. This threw the horse, but the man had to land on his feet holding the reins. This skill was useful for survival because the pampa was riddled with

The gaucho plays an important symbolic role in the nationalist feelings of this region, especially that of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The epic poem by

The gaucho plays an important symbolic role in the nationalist feelings of this region, especially that of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The epic poem by

File:The Gaucho.png, A person in gaucho clothing.

File:GauchosvonALE.jpg, Argentine Pampas gauchos training for the ''Esgrima Criolla''.

File:Prilidiano Pueyrredon - Un alto en el campo - Google Art Project.jpg, ''Un alto en el campo'' (1861) by Prilidiano Pueyrredón.

File:Posta de San Luis.jpg, ''La Posta de San Luis'' by Juan León Pallière (1858).

File:Work17c.jpg, Two gauchos in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1880.

File:Folklore danza zamba (2).jpg, Folklore dance: Zamba, Argentina. Gaucho.

File:PedroII1865.JPG, Emperor

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay,

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul

Rio Grande do Sul (, , ; "Great River of the South") is a Federative units of Brazil, state in the South Region, Brazil, southern region of Brazil. It is the Federative_units_of_Brazil#List, fifth-most-populous state and the List of Brazilian st ...

in Brazil, and the south of Chilean Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

. Gauchos became greatly admired and renowned in legend, folklore, and literature and became an important part of their regional cultural tradition. Beginning late in the 19th century, after the heyday of the gauchos, they were celebrated by South American writers.

The gaucho in some respects resembled members of other nineteenth century rural, horse-based cultures such as the North American cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the '' vaquer ...

( in Spanish), of Central Chile, the Peruvian or , the Venezuelan and Colombian , the Ecuadorian , the Hawaiian , the Mexican , and the Portuguese .

According to the , in its historical sense a gaucho was a "mestizo

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed Ethnic groups in Europe, European and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also r ...

who, in the 18th and 19th centuries, inhabited Argentina, Uruguay, and Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and was a migratory horseman, and adept in cattle work". In Argentina and Uruguay today, gaucho can refer to any "country person, experienced in traditional livestock farming". Because historical gauchos were reputed to be brave, if unruly, the word is also applied metaphorically to mean "noble, brave and generous", but also "one who is skillful in subtle tricks, crafty". In Portuguese the word gaúcho means "an inhabitant of the plains of Rio Grande do Sul or the Pampas of Argentina of European and indigenous American descent who devotes himself to lassoing and raising cattle and horses"; gaúcho has also acquired a metonym

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something closely associated with that thing or concept.

Etymology

The words ''metonymy'' and ''metonym'' come from grc, μετωνυμία, 'a change of name' ...

ic signification in Brazil, meaning anyone, even an urban dweller, who is a citizen of the State of Rio Grande do Sul.

Etymology

Many explanations have been proposed, but no-one really knows how the word "gaucho" originated. Already in 1933 an author counted 36 different theories; more recently, over fifty. They can proliferate because "there is no documentation of any sort that will fix its origin to any time, place or language".Resemblance theories

Most seem to have been conjured up by finding a word that looks something like ''gaucho'' and guessing that it changed to its present form, with scant attention to the sound laws that govern how languages and words really evolve. The etymologistJoan Corominas

Joan Coromines i Vigneaux (; also frequently spelled ''Joan Corominas''; Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico, by Joan Corominas icand José Antonio Pascual, Editorial Gredos, 1989, Madrid, . Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain 1 ...

said most of these theories were "not worthy of discussion". Of the following explanations, Rona said that only #5, #8 and #9 might be taken seriously.

The dialect frontier theory

A different approach is to consider that the word might have originated north of the Río de la Plata, where the indigenous languages were quite different and there is a Portuguese influence.

Two facts that any theory could usefully account for are:

* The word actually exists in two forms: Port. ''gaúcho'' and Sp. ''gaucho'', both long attested.

* Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the Spanish colonial records for present-day Uruguay, often in connection with smuggling to Brazil (see below, Origins). Thus Azara wrote (around 1784):

Hence the Uruguayan

A different approach is to consider that the word might have originated north of the Río de la Plata, where the indigenous languages were quite different and there is a Portuguese influence.

Two facts that any theory could usefully account for are:

* The word actually exists in two forms: Port. ''gaúcho'' and Sp. ''gaucho'', both long attested.

* Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the Spanish colonial records for present-day Uruguay, often in connection with smuggling to Brazil (see below, Origins). Thus Azara wrote (around 1784):

Hence the Uruguayan sociolinguist

Sociolinguistics is the descriptive study of the effect of any or all aspects of society, including cultural norms, expectations, and context, on the way language is used, and society's effect on language. It can overlap with the sociology of l ...

José Pedro Rona thought the origin of the word was to be sought "on the frontier zone between Spanish and Portuguese, which goes from northern Uruguay to the Argentine province of Corrientes

Corrientes (, ‘currents’ or ‘streams’; gn, Taragui), officially the Province of Corrientes ( es, Provincia de Corrientes; gn, Taragüí Tetãmini) is a province in northeast Argentina, in the Mesopotamia region. It is surrounded by (fr ...

and the Brazilian area between them".

Rona, himself born on a language frontier in pre-Holocaust Europe, was a pioneer of the concept of linguistic borders, and studied the dialects of northern Uruguay where Portuguese and Spanish intermingle. Rona thought that, of the two forms — ''gaúcho'' and ''gaucho'' — the former probably came first, because it was linguistically more natural for ''gaúcho'' to evolve by accent-shift to ''gáucho'', than the other way round. Thus the problem came down to explaining the origin of ''gaúcho''.

Auguste de Saint-Hilaire

Augustin François César Prouvençal de Saint-Hilaire (4 October 17793 September 1853) was French botany, botanist and traveller who was born and died in Orléans, France. A keen observer, he is credited with important discoveries in botany, nota ...

, travelling in Uruguay during the Artigas insurgency, wrote in his diary (16 October 1820): The native Spanish-speakers of these borderlands, however, could not process the phoneme /h/, and would render it as a null, thus ''gaúcho''. In sum, according to this theory, ''gaúcho'' originated in the Uruguay-Brazil dialect borderlands, deriving from a derisive indigenous word ''garrucho'', then in Spanish lands evolved by accent-shift to ''gaucho''.

History

The historical "gaucho" is elusive, because there has been more than one kind. Mythologisation has obscured the topic.Origins

Itinerant horsemen, hunting wild cattle on the pampas, originated as a social class during the 17th century. "The great natural abundance of the pampa", wrote Richard W. Slatta, The original gaucho was typically descended from unions between Iberian men and Amerindian women, although he might also have African ancestry. A DNA analysis study of rural inhabitants of

The original gaucho was typically descended from unions between Iberian men and Amerindian women, although he might also have African ancestry. A DNA analysis study of rural inhabitants of Rio Grande do Sul

Rio Grande do Sul (, , ; "Great River of the South") is a Federative units of Brazil, state in the South Region, Brazil, southern region of Brazil. It is the Federative_units_of_Brazil#List, fifth-most-populous state and the List of Brazilian st ...

, who style themselves ''gaúchos'', has claimed to discern, not only Amerindian ( Charrúa and Guaraní) ancestry in the female line but, in the male line, a higher proportion of Spanish ancestry than is usual in Brazil. However, gauchos were a social class, not an ethnic group.

Gauchos are first mentioned by name in the 18th century records of the Spanish colonial authorities who administered the Banda Oriental (present-day Uruguay). For them, he is an outlaw, cattle thief, robber and smuggler. Félix de Azara (1790) said gauchos were "the dregs of the Rio de la Plata and of Brazil". Summarised one scholar: "Fundamentally he gaucho of the time

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

was a colonial bootlegger whose business was contraband trade in cattle hides. His work was highly illegal; his character lamentably reprehensible; his social standing exceedingly low.

"Gaucho" was an insult; yet it was possible to use the word to refer, without animosity, to country people in general. Furthermore the gaucho's skills, though useful in banditry or smuggling, were just as useful for serving in the frontier police. The Spanish administration recruited its antismuggling Cuerpo de Blandengues from among the outlaws themselves. The Uruguayan patriot José Gervasio Artigas made precisely that career transition.

Wars of emancipation; independence

The gaucho was a born cavalryman, and his bravery in the patriot cause in the wars of independence, especially under Artigas and Martín Miguel de Güemes, earned admiration and improved his image. The Spanish General García Gamba, who fought against Güemes in Salta, said: Knowing "gaucho" to be an insult, the Spanish hurled it at the patriot militias; Güemes, however, picked it up as a badge of honour, referring to his troops as "my gauchos". Visitors to the newly emergent Argentina and Uruguay perceived that a "gaucho" was a country person or herdsman: seldom was there a pejorative significance. Emeric Essex Vidal, the first artist to paint gauchos, noted their mobility (1820): Vidal also painted visiting gauchos from up-country Tucumán. ("Their features are particularly Spanish, uncrossed by that mixture observable in the citizens of Buenos Ayres"). They are not horsemen: they are oxcart drivers, and may or may not have called themselves gauchos in their home province.

Charles Darwin observed life on the pampas for six months and reflected in his diary (1833):

Vidal also painted visiting gauchos from up-country Tucumán. ("Their features are particularly Spanish, uncrossed by that mixture observable in the citizens of Buenos Ayres"). They are not horsemen: they are oxcart drivers, and may or may not have called themselves gauchos in their home province.

Charles Darwin observed life on the pampas for six months and reflected in his diary (1833):

Controlling the wandering gaucho

Argentina

As cattle estates grew bigger the freely wandering gaucho became a nuisance to landed proprietors, except when his casual labour was wanted e.g. at branding. Furthermore his services were needed in the armies that were fighting on the Indian frontiers, or in the frequent civil wars. Hence in Argentina, vagrancy laws required rural workers to carry employment documents. Some restrictions on the gaucho's freedom of movement were imposed under Spanish Viceroy Sobremonte, but they were greatly intensified under Bernardino Rivadavia, and were enforced more vigorously still underJuan Manuel de Rosas

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws", was an Argentine politician and army officer who ruled Buenos Aires Province and briefly the Argentine Confederation. Althoug ...

. Those who did not carry the documentation could be sentenced to years in the military. From 1822 to 1873 even internal passports were required.

According to Marxist and other scholars the gaucho became "proletarianized", preferring life as a salaried peon

Peon (English , from the Spanish ''peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over emp ...

on an estancia to forced enlistment, irregular pay and harsh discipline. However, some resisted. "In words and deeds, soldiers contested the state's disciplinary model", frequently deserting. Deserters often fled to the Indian frontier, or even took refuge with the Indians themselves. José Hernández José Hernández may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* José Hernández (writer) (1834–1886), Argentine writer

* Pepe Hern (José Hernández Bethencourth, 1927–2009), American actor

* José Hernández, American singer (born 1940), better known ...

described the bitter fate of just such a gaucho protagonist in his poem Martín Fierro (1872), a great popular success in the countryside. One estimate was that renegade gauchos comprised half of all Indian raiding parties.

Lucio Victorio Mansilla

Lucio Victorio Mansilla (December 23, 1831 – October 8, 1913) was an Argentinean General, journalist, politician and diplomat. He was later governor of the territory of the Gran Chaco between 1878 and 1879.

His best-known literary work is '' ...

(1877) thought he could discern two types of gaucho in the soldiers under his command: The ''paisano gaucho'' (country worker) has a home, a fixed abode, work habits, respect for authority, on whose side he will always be, even against his better feelings. But the ''gaucho neto'' (out-and-out gaucho) is the typical wandering ''criollo'', here today, there tomorrow; gambler, quarreler, enemy of discipline; who flees military service when it is his turn, takes refuge among the Indians if he knifes someone, or joins the ''montonera'' (armed rabble) if it shows up. The first has the instincts of civilization; he imitates the man of the cities in his dress, in his customs. The second loves tradition; he hates foreigners; his luxury is his spurs, his flash gear, his leather sash, his facón (dagger-sword). The first takes off his poncho to go into town, the second goes there flaunting his trappings. The first is a cultivator, oxcart driver, cattle drover, herdsman, a peon. The second hires himself out for cattle branding. The first has been a soldier several times. The second was once part of a squadron and as soon as he saw his chance he deserted. The first is always ''federal'', the second is no longer anything. The first still believes in something; the second believes in nothing. He has suffered more than the city slicker, and so has been disillusioned quicker. He votes, because the Commander or the Mayor tells him to, and with that universal suffrage is achieved. If he has a claim, he drops it because he thinks it is frankly a waste of time. In a word, the first is a useful man for industry and work — the second is a dangerous inhabitant anywhere. If he resorts to the courts, it is because he has the instinct to believe that they will do him justice out of fear – and there are examples, if they don't do it he takes revenge — he wounds or kills. The former makes up the Argentine social mass; the second is disappearing.Already in 1845 a local dialect dictionary, by a knowledgeable compiler, gave "gaucho" as meaning any kind of rural worker, including one who cultivated the soil. To refer to the wandering sort, one had to specify further. Documentary research has shown the great majority of rural workers in Buenos Aires province were not herdsmen, but cultivators or shepherds. Thus, the gaucho that survives in today's popular imagination — the galloping horseman — was not typical.

Brazil and Uruguay

Gauchos north of the Río de la Plata were similar to their Argentine counterparts; however there were some differences, particularly in the region straddling Brazil and Uruguay. The Portuguese Crown, in order to conquer southern Brazil — it was disputed with the Spanish Empire — distributed vast tracts of land to a few hundred families. Labour in this region was scarce, so great landowners acquired it by allowing a social class, called ''agregados'', to settle on their land with their own animals. Values were martial and paternalistic, for the territory went back and forth between Portugal and Spain. Brazilian inheritance laws compelled landowners to leave their lands in equal shares to their sons and daughters, and since they were numerous, and those laws were hard to evade, great landholdings fractured in a few generations. There were not the huge cattle estates of Buenos Aires province where, as an extreme example, the Anchorena family owned in 1864.

Unlike Argentina, cattlemen in Rio Grande do Sul did not have vagrancy laws to tie gaúchos to their ranches. However, slavery was legal in Brazil; in Rio Grande do Sul it existed until 1884; and perhaps a majority of permanent ranch workers were enslaved. Thus many horse-riding ''campeiros'' (cowboys) were black slaves. They enjoyed sharply better living conditions than the slaves who worked in the brutal ''xarqueadas'' (beef-salting plants). John Charles Chasteen explained why:

Brazilian inheritance laws compelled landowners to leave their lands in equal shares to their sons and daughters, and since they were numerous, and those laws were hard to evade, great landholdings fractured in a few generations. There were not the huge cattle estates of Buenos Aires province where, as an extreme example, the Anchorena family owned in 1864.

Unlike Argentina, cattlemen in Rio Grande do Sul did not have vagrancy laws to tie gaúchos to their ranches. However, slavery was legal in Brazil; in Rio Grande do Sul it existed until 1884; and perhaps a majority of permanent ranch workers were enslaved. Thus many horse-riding ''campeiros'' (cowboys) were black slaves. They enjoyed sharply better living conditions than the slaves who worked in the brutal ''xarqueadas'' (beef-salting plants). John Charles Chasteen explained why: Land-hungry Rio Grande cattlemen bought up estates cheaply in neighbouring Uruguay until they owned about 30% of that country, which they ranched with their slaves and cattle. The border area was fluid, bilingual and lawless. Though slavery was abolished in Uruguay in 1846, and there were laws against human trafficking, weak governments poorly enforced those laws. Often Brazilian ranchers simply ignored them, even crossing and re-crossing the border with their slaves and cattle. An 1851 extradition treaty required Uruguay to return fugitive Brazilian slaves.

Governments found it hard to establish a monopoly of violence in the border area. In the Federalist Revolution of 1893 gaúcho-manned armies led by elite families fought each other with exceptional barbarity. Powerful Brazilian-Uruguayan families, like the Saraivas, led mounted insurrections in both countries, even in the 20th century. In the satirical cartoon (1904)

Land-hungry Rio Grande cattlemen bought up estates cheaply in neighbouring Uruguay until they owned about 30% of that country, which they ranched with their slaves and cattle. The border area was fluid, bilingual and lawless. Though slavery was abolished in Uruguay in 1846, and there were laws against human trafficking, weak governments poorly enforced those laws. Often Brazilian ranchers simply ignored them, even crossing and re-crossing the border with their slaves and cattle. An 1851 extradition treaty required Uruguay to return fugitive Brazilian slaves.

Governments found it hard to establish a monopoly of violence in the border area. In the Federalist Revolution of 1893 gaúcho-manned armies led by elite families fought each other with exceptional barbarity. Powerful Brazilian-Uruguayan families, like the Saraivas, led mounted insurrections in both countries, even in the 20th century. In the satirical cartoon (1904) Aparicio Saravia

Aparicio Saravia da Rosa (August 16, 1856 – September 10, 1904) was a Uruguayan politician and military leader. He was a member of the Uruguayan National Party and was a revolutionary leader against the Uruguayan government.

Early life

...

says it is time for "another little revolution": they have been at peace long enough and are starting to look ridiculous. This time, however, his mobile, lance-wielding horsemen were put down, and decisively, by Uruguayan troops armed with Mauser

Mauser, originally Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik ("Royal Württemberg Rifle Factory"), was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols has been produced since the 1870s for the German arme ...

rifles and Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krup ...

cannon, efficiently deployed by telegraph and rail.

European immigration; fencing the pampa

It was official government policy, enshrined in the Argentine Constitution of 1853, to encourage European immigration. The purpose, which was not concealed, was to supplant the "lower races" of the sparsely populated interior, including gauchos, whom the elite believed to be hopelessly backward. Famously, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Argentina's second elected president, had written (in Facundo: Civilización y Barbarie) that gauchos, although audacious and skilled in country lore, were brutal, feckless, lived indolently in squalor, and — by upholding the caudillos (provincial strongmen) — were obstacles to national unity. The population was so thinly spread it was impossible to educate. They were barbarians, inimical to progress. Juan Bautista Alberdi, deviser of the Constitution, held that "to govern is to populate". Once political stability was achieved the results were dramatic. From around 1875 a flood of immigrants altered the country's ethnic composition. In 1914, 40% of Argentina's residents were foreign-born. Today, Italian surnames are more common than Spanish.

Barbed wire, cheap from 1876, fenced the pampa "and thus eliminated the need for gaucho cowboys". Gauchos were forced off the land, drifting into rural towns to look for work, though a few were retained as peon labourers. Cunninghame Graham, after whom a Buenos Aires street is named, and who had lived as a gaucho in the 1870s, returned in 1914 to "his first love, Argentina" and found it had greatly changed. "Progress, which he constantly lambasted, had rendered the gaucho virtually extinct".

Wote S. Samuel Trifilo (1964): "The gaucho of today working on the pampas of Argentina is no more a real gaucho than is our own present-day cowboy the cowboy of the Wild West; both have gone forever."

Two-thirds of Uruguay lies south of the Río Negro, and this part was fenced most intensively in the decade 1870-1880. The gaucho was marginalised and was frequently driven to live in ''pueblos de ratas'' (rural slums, literally rat towns).

North of the Río Negro mobile gauchos survived rather longer. A Scottish anthropologist in the central region (1882) saw many of them as unsettled. European immigration to the countryside was smaller. The central government failed to consolidate its power over the countryside, and gaucho-manned armies continued to defy it until 1904. The turbulent gaucho leaders e.g. the Saravias had connections with the cattlemen over the Brazilian border, where there was much less European immigration; Wire fences did not become common in the borderland until the close of the 19th century.

The revolutionary battles in Brazil ended by 1930 under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, who disarmed the private gaúcho armies and prohibited the carrying of guns in public.

Once political stability was achieved the results were dramatic. From around 1875 a flood of immigrants altered the country's ethnic composition. In 1914, 40% of Argentina's residents were foreign-born. Today, Italian surnames are more common than Spanish.

Barbed wire, cheap from 1876, fenced the pampa "and thus eliminated the need for gaucho cowboys". Gauchos were forced off the land, drifting into rural towns to look for work, though a few were retained as peon labourers. Cunninghame Graham, after whom a Buenos Aires street is named, and who had lived as a gaucho in the 1870s, returned in 1914 to "his first love, Argentina" and found it had greatly changed. "Progress, which he constantly lambasted, had rendered the gaucho virtually extinct".

Wote S. Samuel Trifilo (1964): "The gaucho of today working on the pampas of Argentina is no more a real gaucho than is our own present-day cowboy the cowboy of the Wild West; both have gone forever."

Two-thirds of Uruguay lies south of the Río Negro, and this part was fenced most intensively in the decade 1870-1880. The gaucho was marginalised and was frequently driven to live in ''pueblos de ratas'' (rural slums, literally rat towns).

North of the Río Negro mobile gauchos survived rather longer. A Scottish anthropologist in the central region (1882) saw many of them as unsettled. European immigration to the countryside was smaller. The central government failed to consolidate its power over the countryside, and gaucho-manned armies continued to defy it until 1904. The turbulent gaucho leaders e.g. the Saravias had connections with the cattlemen over the Brazilian border, where there was much less European immigration; Wire fences did not become common in the borderland until the close of the 19th century.

The revolutionary battles in Brazil ended by 1930 under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, who disarmed the private gaúcho armies and prohibited the carrying of guns in public.

The gaucho as an icon

Argentina

In the 20th century urban intellectuals promoted the gaucho as the Argentine national icon; it was a reaction to massive European immigration and a rapidly changing way of life. Jeane DeLaney has argued that the immigrant was beingscapegoated

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out a person or group for unmerited blame and consequent negative treatment. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals (e.g. "he did it, not me!"), individuals against groups (e.g., ...

for the problems of modernity; thus, the sentiment was antimodernistic, with a xenophobic, nationalistic edge.

Writers variously reflecting this tendency included José María Ramos Mejía, Manuel Gálvez, Rafael Obligado, José Ingenieros, Miguel Cané, and above all Leopoldo Lugones and Ricardo Güiraldes. Their answer was to go back to values that could be attributed to the old-time gaucho. However, the gaucho they chose was not the one who cultivated the land, but the one who galloped across it.

For Lugones (1913), to discern a people's true character, one had to read its epic poetry; and '' Martín Fierro'' was the Argentine epic poem ''par excellence''. Far from being a barbarian, the gaucho was the hero who did what the Spanish Empire could not — civilise the pampa by subjugating the Indian. To be a gaucho demanded "composure, courage, ingenuity, meditation, sobriety, vigour; all this made him a free man". But in that case, asked Lugones, why did the gaucho disappear? Because, together with his virtues, he had inherited two defects from his Indian and Spanish ancestors: laziness and pessimism.

Lugones' lectures, where he canonised ''Martín Fierro'' with its quarreling gaucho protagonist, had official support: the president of the Republic and his cabinet attended them, as did prominent members of the traditional ruling classes.

However, wrote a Mexican scholar, in exalting this gaucho Lugones and others were not recreating a real historical character, they were weaving a nationalist myth, for political purposes. Jorge Luis Borges thought their choice of gaucho was a poor

For Lugones (1913), to discern a people's true character, one had to read its epic poetry; and '' Martín Fierro'' was the Argentine epic poem ''par excellence''. Far from being a barbarian, the gaucho was the hero who did what the Spanish Empire could not — civilise the pampa by subjugating the Indian. To be a gaucho demanded "composure, courage, ingenuity, meditation, sobriety, vigour; all this made him a free man". But in that case, asked Lugones, why did the gaucho disappear? Because, together with his virtues, he had inherited two defects from his Indian and Spanish ancestors: laziness and pessimism.

Lugones' lectures, where he canonised ''Martín Fierro'' with its quarreling gaucho protagonist, had official support: the president of the Republic and his cabinet attended them, as did prominent members of the traditional ruling classes.

However, wrote a Mexican scholar, in exalting this gaucho Lugones and others were not recreating a real historical character, they were weaving a nationalist myth, for political purposes. Jorge Luis Borges thought their choice of gaucho was a poor role model

A role model is a person whose behaviour, example, or success is or can be emulated by others, especially by younger people. The term ''role model'' is credited to sociologist Robert K. Merton, who hypothesized that individuals compare themselves ...

for Argentines.

Wrote musicologist Melanie Plesch:

The iconic gaucho gained traction in popular culture because he appealed to diverse social groups: displaced rural workers; European immigrants anxious to assimilate; traditional ruling classes wanting to affirm their own legitimacy.A classic thesis developed by Adolfo Prieto. At a time when the elite was extolling Argentina as a "white" country, a fourth group, those who possessed dark skins, felt validated by the gaucho's elevation, seeing that his non-white ancestry was too well known to be concealed.

Today a popular movement celebrates gaucho culture.

Brazil

In Rio Grande do Sul the gaúcho has been mythified too, not in reaction to massive immigration as in Argentina, but to give the state a regional identity. The main celebration is the ''Semana Farroupilha'', a week of festivities, mass horseback parades, ''

In Rio Grande do Sul the gaúcho has been mythified too, not in reaction to massive immigration as in Argentina, but to give the state a regional identity. The main celebration is the ''Semana Farroupilha'', a week of festivities, mass horseback parades, ''churrasco

''Churrasco'' (, ) is the Portuguese and Spanish name for beef or grilled meat more generally. It is a prominent feature in the cuisine of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina. The related term ''churrascaria'' (or ''churrasquería'') is mostly under ...

'', rodeos and dances. It refers to the Ragamuffin War (1835–45), an elite-led separatist war against the Brazilian Empire; politicians have reinterpreted it as democratic movement. Hence, wrote Luciano Bornholdt, All the inhabitants of Rio Grande do Sul today, even lawyers and midwives, call themselves ''gaúchos''. Actual ranchers and ''peões'' (peons), when referring to their own social group, use the word rather less. For them, ''gaúcho'' is not a tradition, just a skillset.

The ''Movimento Tradicionalista Gaúcho'' (MTG) has an active participation of two million people, and claims to be the largest popular culture movement in the Western world. Essentially urban, rooted in nostalgia for rural life, the MTG fosters gaúcho culture. There are 2,000 Centres for Gaúcho Traditions, not only in the state, but elsewhere, even Los Angeles and Osaka, Japan. Gaúcho products include television and radio programs, articles, books, dance halls, performers, records, theme restaurants, and clothing. The movement was founded by intellectuals, apparently sons of downwardly mobile small landowners who had moved to the cities to study. Since gaúcho culture was seen as male, only later were women invited to participate. Though the real gaúchos of history lived in the Campanha (plains region), some of the first to join were of German or Italian ethnicity from outside that area, a social class who had idealised the gaúcho rancher as a type superior to themselves.

Horsemanship

For many, an essential attribute of a gaucho is that he is a skilled horseman. Scottish physician and botanistDavid Christison

David Christison MD FRCPE LLD (1830–1912) was a Scottish physician, botanist, writer and antiquary. He served as a military doctor during the Crimean War, at which time, owing to illness, he abandoned his medical career. From the 1860s o ...

noted in 1882, "He has taken his first lessons in riding before he is well able to walk". Without a horse the gaucho himself felt unmanned. During the wars of the 19th century in the Southern Cone

The Southern Cone ( es, Cono Sur, pt, Cone Sul) is a geographical and cultural subregion composed of the southernmost areas of South America, mostly south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Traditionally, it covers Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, bou ...

, the cavalries on all sides were composed almost entirely of gauchos. In Argentina, gaucho armies such as that of Martín Miguel de Güemes, slowed Spanish advances. Furthermore, many relied on gaucho armies to control the Argentine provinces.

The naturalist William Henry Hudson, who was born on the Pampas of Buenos Aires province

Buenos Aires (), officially the Buenos Aires Province (''Provincia de Buenos Aires'' ), is the largest and most populous Argentine province. It takes its name from the city of Buenos Aires, the capital of the country, which used to be part of th ...

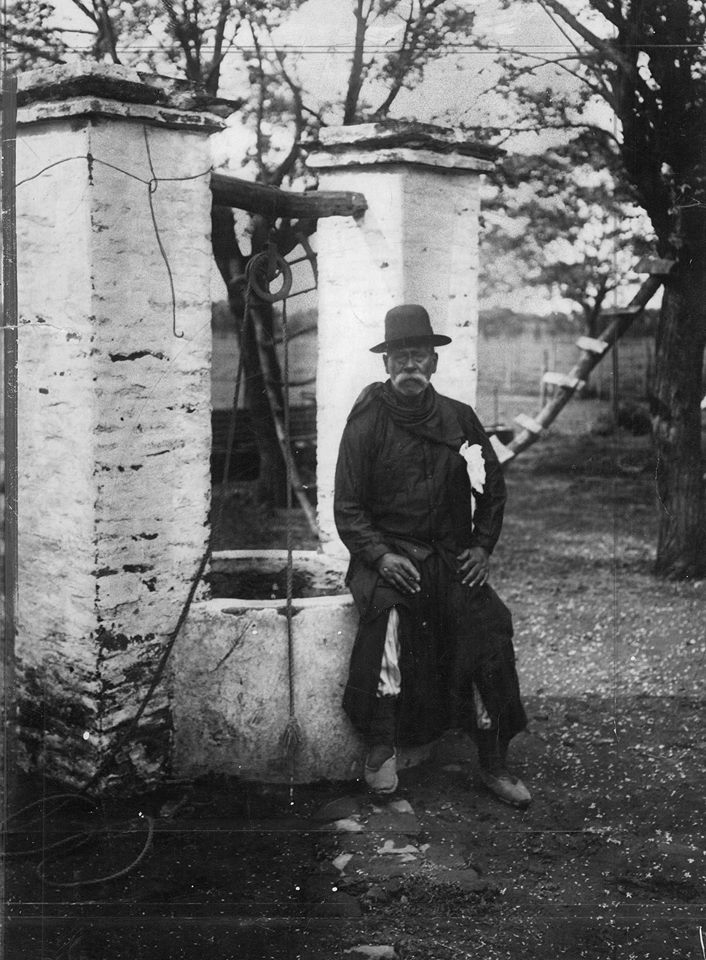

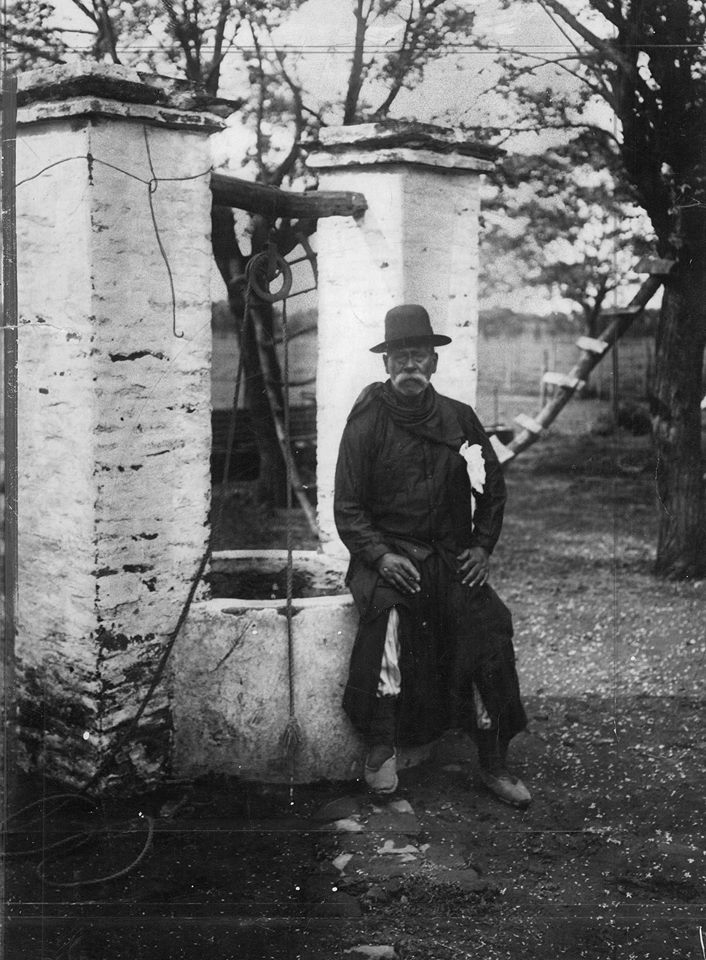

, recorded that the gauchos of his childhood used to say that a man without a horse was a man without legs. He described meeting a blind gaucho who was obliged to beg for his food yet behaved with dignity and went about on horseback. Richard W. Slatta, the author of a scholarly work about gauchos, notes that the gaucho used horses to collect, mark, drive or tame cattle, to draw fishing nets, to hunt ostriches, to snare partridges, to draw well water, and even—with the help of his friends—to ride to his own burial.

By reputation the quintessential gaucho Juan Manuel de Rosas

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws", was an Argentine politician and army officer who ruled Buenos Aires Province and briefly the Argentine Confederation. Althoug ...

could throw his hat on the ground and scoop it up while galloping his horse, without touching the saddle with his hand. For the gaucho, the horse was absolutely essential to his survival for, said Hudson: "he must every day traverse vast distances, see quickly, judge rapidly, be ready at all times to encounter hunger and fatigue, violent changes of temperature, great and sudden perils".

A popular was:

It was the gaucho's passion to own all his steeds in matching colours. Hudson recalled: The gaucho, from the poorest worker on horseback to the largest owner of lands and cattle, has, or had in those days, a fancy for having all his riding-horses of one colour. Every man as a rule had his tropilla — his own half a dozen or a dozen or more saddle-horses, and he would have them all as nearly alike as possible, so that one man had chestnuts, another browns, bays, silver- or iron-greys, duns, fawns, cream-noses, or blacks, or whites, or piebalds.The Chacho Peñaloza described the low point of his life as "In Chile − and on foot!" ()

Extreme equestrianship

Richard W. Slatta collected instances of extreme equestrian sports practised by 19th century gauchos. To perform these required and developed skills and courage that helped gauchos to survive on the pampas.

*Crowding. Two men would spur their horses to shove against each other, each man's object being to drive his opponent to a particular place. In a variant, they raced along a narrow track; if one man could crowd the other off it, he won.

*''Cinchada''. An equestrian tug-of-war, tail to tail; the rope was tied to their saddles. "This contest grew out of the need for mounts strong enough to pull against a wild, lassoed steer".

*''Pechando''. Two horsemen galloping at full speed charged each other head on. The shock of the collision tumbled the men and perhaps the horses. The object was to recover and charge again and again until prevented by exhaustion or injury. "Pechando provided an opportunity for a gaucho to exhibit his courage and indifference to death or injury."

*Jumping the bar. A bar was placed above a corral gate with just enough headroom for a horse to pass. A gaucho galloped through, and as he did, he jumped over the bar and landed back in the saddle.

*''Maroma''. A variant in which the gaucho jumped from the bar onto the back of a racing wild horse or wild steer. He had to stay on until the horse was broken or the steer was killed.

*Recado. The horseman galloped across the pampa while he undid his ''recado'' (a multi-layered saddle), dropping the pieces as he went. He had to go back, snatch up the pieces and reassemble his saddle, all the time riding at full speed.

*''Pialar'', a particularly dangerous sport. One man galloped through a group of gauchos who lassoed his horse's legs. This threw the horse, but the man had to land on his feet holding the reins. This skill was useful for survival because the pampa was riddled with

Richard W. Slatta collected instances of extreme equestrian sports practised by 19th century gauchos. To perform these required and developed skills and courage that helped gauchos to survive on the pampas.

*Crowding. Two men would spur their horses to shove against each other, each man's object being to drive his opponent to a particular place. In a variant, they raced along a narrow track; if one man could crowd the other off it, he won.

*''Cinchada''. An equestrian tug-of-war, tail to tail; the rope was tied to their saddles. "This contest grew out of the need for mounts strong enough to pull against a wild, lassoed steer".

*''Pechando''. Two horsemen galloping at full speed charged each other head on. The shock of the collision tumbled the men and perhaps the horses. The object was to recover and charge again and again until prevented by exhaustion or injury. "Pechando provided an opportunity for a gaucho to exhibit his courage and indifference to death or injury."

*Jumping the bar. A bar was placed above a corral gate with just enough headroom for a horse to pass. A gaucho galloped through, and as he did, he jumped over the bar and landed back in the saddle.

*''Maroma''. A variant in which the gaucho jumped from the bar onto the back of a racing wild horse or wild steer. He had to stay on until the horse was broken or the steer was killed.

*Recado. The horseman galloped across the pampa while he undid his ''recado'' (a multi-layered saddle), dropping the pieces as he went. He had to go back, snatch up the pieces and reassemble his saddle, all the time riding at full speed.

*''Pialar'', a particularly dangerous sport. One man galloped through a group of gauchos who lassoed his horse's legs. This threw the horse, but the man had to land on his feet holding the reins. This skill was useful for survival because the pampa was riddled with vizcacha

Viscacha or vizcacha (, ) are rodents of two genera (''Lagidium'' and ''Lagostomus'') in the family Chinchillidae. They are native to South America and convergently resemble rabbits.

The five extant species of viscacha are:

*The plains vis ...

burrows that threw horses; loss of one's mount was probable death for a solitary rider.

Gauchos routinely maltreated their horses since these were plentiful. Even a poor gaucho usually had a ''tropilla'' of perhaps a dozen. Most of those sports were banned by the elite.

*''La sortija''. Carrying a lance, a galloping horseman had to impale a small ring dangling from a thread. Introduced from Spain, this sport is still practised in Spanish-speaking countries.

*''Pato''. A game resembling rugby football on horseback, but ranging over miles of terrain. Banned in its original form, pato was gentrified and is now Argentina's national sport.

The higher skills were lost as the gaucho was marginalised, wrote Slatta:

Culture

The gaucho plays an important symbolic role in the nationalist feelings of this region, especially that of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The epic poem by

The gaucho plays an important symbolic role in the nationalist feelings of this region, especially that of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The epic poem by José Hernández José Hernández may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* José Hernández (writer) (1834–1886), Argentine writer

* Pepe Hern (José Hernández Bethencourth, 1927–2009), American actor

* José Hernández, American singer (born 1940), better known ...

(considered by some the national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with as ...

of Argentina) used the gaucho as a symbol against corruption and of Argentine national tradition, pitted against Europeanising tendencies. Martín Fierro, the hero of the poem, is drafted into the Argentine military for a border war, deserts, and becomes an outlaw and fugitive. The image of the free gaucho is often contrasted to the slaves who worked the northern Brazilian lands. Further literary descriptions are found in Ricardo Güiraldes' .

Gauchos were generally reputed to be strong, honest, silent types, but proud and capable of violence when provoked. The gaucho tendency to violence over petty matters is also recognized as a typical trait. Gauchos' use of the —a large knife generally tucked into the rear of the gaucho's sash—is legendary, often associated with considerable bloodletting. Historically, the was typically the only eating instrument that a gaucho carried.

The gaucho diet was composed almost entirely of beef while on the range, supplemented by , an herbal infusion made from the leaves of yerba mate, a type of holly rich in caffeine and nutrients. The water for was heated short of boiling on a stove in a kettle, and traditionally served in a hollowed-out gourd and sipped through a metal straw called a .

Gauchos dressed and wielded tools quite distinct from North American cowboys. In addition to the lariat, gauchos used or ( in Portuguese)—three leather-bound rocks tied together with leather straps. The typical gaucho outfit would include a poncho, which doubled as a saddle blanket and as sleeping gear; a (dagger); a leather whip called a ; and loose-fitting trousers called or a poncho or blanket wrapped around the loins like a diaper called a , belted with a sash called a . A leather belt, sometimes decorated with coins and elaborate buckles, is often worn over the sash. During winters, gauchos wore heavy wool ponchos to protect against cold.

Their tasks were to move the cattle between grazing fields, or to market sites such as the port of Buenos Aires. The consists of branding the animal with the owner’s sign. The taming of animals was another of their usual activities. Taming was a trade especially appreciated throughout Argentina and competitions to domesticate wild foal

A foal is an equine up to one year old; this term is used mainly for horses, but can be used for donkeys. More specific terms are colt for a male foal and filly for a female foal, and are used until the horse is three or four. When the foal i ...

remained in force at festivals. The majority of gauchos were illiterate and considered as countrymen.

Modern influences

, a boy in the Argentine colors and a gaucho hat, was the mascot for the1978 FIFA World Cup

The 1978 FIFA World Cup was the 11th edition of the FIFA World Cup, a quadrennial international football world championship tournament among the men's senior national teams. It was held in Argentina between 1 and 25 June.

The Cup was won by t ...

.

In popular culture

* is a 2,316-line epic poem by the Argentine writer José Hernández on the life of the eponymous gaucho. * ''Way of a Gaucho

''Way of a Gaucho'' is a 1952 American Western drama film directed by Jacques Tourneur and starring Gene Tierney and Rory Calhoun. It was written by Philip Dunne and based on a novel by Herbert Childs.

The film was made by 20th Century Fox an ...

'' 1952 film starring Gene Tierney and Rory Calhoun.

* '' The Gaucho'' was a 1927 film starring Douglas Fairbanks.

* was a 1942 Argentine film set during the Gaucho war against Spanish royalists in Salta, northern Argentina, in 1817. It is considered a classic of Argentine cinema.

* The third segment of Disney's 1942 animated feature package film, , is titled "El Gaucho Goofy", where American cowboy Goofy gets taken mysteriously to the Argentine Pampas to learn the ways of the native gaucho.

* '' Gaucho'' is the name of the 1980 album by American jazz fusion

Jazz fusion (also known as fusion and progressive jazz) is a music genre that developed in the late 1960s when musicians combined jazz harmony and jazz improvisation, improvisation with rock music, funk, and rhythm and blues. Electric guitars, ...

band Steely Dan

Steely Dan is an American rock band founded in 1971 in New York by Walter Becker (guitars, bass, backing vocals) and Donald Fagen (keyboards, lead vocals). Initially the band had a stable lineup, but in 1974, Becker and Fagen retired from live ...

, which featured a song by the same name.

* '' Gauchos of El Dorado'' was a 1941 American Western ''Three Mesquiteers

''The Three Mesquiteers'' is the umbrella title for a Republic Pictures series of 51 American Western B-movies released between 1936 and 1943. The films, featuring a trio of Old West adventurers, was based on a series of Western novels by W ...

'' B-movie

A B movie or B film is a low-budget commercial motion picture. In its original usage, during the Golden Age of Hollywood, the term more precisely identified films intended for distribution as the less-publicized bottom half of a double featur ...

directed by Lester Orlebeck.

* by Roberto Fontanarrosa is an Argentinean humor comics series about a gaucho.

* ''Gaucho'' is the name of a song by the Dave Matthews Band on the 2012 album Away From the World

''Away from the World'' is the eighth studio album by Dave Matthews Band (DMB), released on September 11, 2012. The album is their first since 2009's ''Big Whiskey & the GrooGrux King.'' The album's title comes from a line in the song "The Riff": ...

.

* The Gaucho is the University of California Santa Barbara mascot.

* ''The Jewish Gauchos

The Jewish Gauchos, (''Los Gauchos Judíos'' in Spanish, and published in English as The Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas) is a novel of Ukrainian-born Argentine writer and journalist Alberto Gerchunoff, who is regarded as the founder of Jewish lite ...

'' is a 1910 novel by Alberto Gerchunoff about Jewish gauchos in Argentina. It was adapted into a film, , in 1975.

* Gaucho culture is often referred to by Borges

Gallery

Pedro II of Brazil

Don (honorific), Dom PedroII (2 December 1825 – 5 December 1891), nicknamed "the Magnanimity, Magnanimous" ( pt, O Magnânimo), was the List of monarchs of Brazil, second and last monarch of the Empire of Brazil, reigning for over 58 years. ...

in typical Gaúcho outfit.

File:Yerra en Corrientes.jpg, Gauchos in Corrientes province, Argentina.

File:Payador rancho.jpg, A Gaucho payador.

File:Gaucho-a-cavalo.jpg, Brazilian gaúcho with typical clothing at the 2006 Farroupilha Parade.

File:Argentinian gauchos.jpg, Argentine gauchos in the city of Salta.

File:Gumercindo tropa.jpg, Gauchos in the Federalist Revolution (1893 to 1895).

File:Gaúchos dança.jpeg, Riograndenses dancing in full gaúcho outfit (2012)

File:TRIO DE OURO.jpg, Gaúchos with Criollo horses in Brazil, 2007

File:Estátua_"Gaucho_Oriental"_no_Parque_Farroupilha.jpg, Statue ''Gaucho Oriental'' created by Federico Escalada in 1935 and gifted by Uruguay to the people of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil)

See also

* Stockman *Gaucho sheepdog

The Gaucho Sheepdog ( pt, Ovelheiro gaúcho) is a dog breed that originated in the Pampas, Brazil.Criollo horse

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{Authority control Animal husbandry occupations Argentine folklore Chilean folklore Culture in Rio Grande do Sul Pastoralists Uruguayan folklore Brazilian folklore Latin American folklore South American folklore National symbols of Argentina Horse history and evolution Horse-related professions and professionals Herding Ethnic groups in Brazil Transhumance Gaucho culture Obsolete occupations