Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

After the outbreak of the

After the outbreak of the

On 1 April 1882, Wolseley was appointed Adjutant-General to the Forces, and, in August of that year, given command of the British forces in Egypt under

On 1 April 1882, Wolseley was appointed Adjutant-General to the Forces, and, in August of that year, given command of the British forces in Egypt under

Wolseley was deeply opposed to Sir Edward Watkin's attempt to build a

Wolseley was deeply opposed to Sir Edward Watkin's attempt to build a

Biography at the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''

* * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wolseley, Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount 1833 births 1913 deaths 19th-century Anglo-Irish people Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom British Army personnel of the Anglo-Egyptian War British Army personnel of the Anglo-Zulu War British Army personnel of the Crimean War British Army personnel of the Mahdist War British Army personnel of the Second Opium War British field marshals British military personnel of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 British Army personnel of the Second Anglo-Burmese War British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War Burials at St Paul's Cathedral Commanders-in-Chief, Ireland Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Governors of Natal Governors of the Gold Coast (British colony) High commissioners of the United Kingdom to Cyprus Irish Freemasons Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights of St Patrick Members of the Council of India Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Privy Council of Ireland Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Military personnel from Dublin (city) People of the Fenian raids People of the Red River Rebellion People of the Sekukuni Campaign Recipients of the Order of the Medjidie, 5th class Royal Horse Guards officers Suffolk Regiment officers Transvaal Colony people Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Governors of the Transvaal Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley (4 June 183325 March 1913) was an Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

officer in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

. He became one of the most influential British generals after a series of victories in Canada, West Africa and Egypt, followed by a central role in modernizing the British Army in promoting efficiency.

Wolseley is considered to be one of the most prominent and decorated war heroes of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

during the era of New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

. He served in Burma, the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, the Indian Mutiny, China, Canada and widely throughout Africa—including his Ashanti campaign (1873–1874) and the Nile Expedition

The Nile Expedition, sometimes called the Gordon Relief Expedition (1884–1885), was a British mission to relieve Major-General Charles George Gordon at Khartoum, Sudan. Gordon had been sent to Sudan to help the Egyptians withdraw their garr ...

against Mahdist Sudan in 1884–85. Wolseley served as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, later Commander-in-Chief, British Army, or just Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), was (intermittently) the title of the professional head of the English Army from 1660 to 1707 (the English Army, founded in 1645, wa ...

from 1895 to 1900. His reputation for efficiency led to the late 19th century English phrase "everything's all Sir Garnet", meaning, "All is in order."

Early life and education

Lord Wolseley was born into a prominentAnglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

family in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, the eldest son of Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Garnet Joseph Wolseley of the King's Own Scottish Borderers

The King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSBs) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Scottish Division. On 28 March 2006 the regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Scots, the Royal Highland Fusiliers, Royal Highland Fusiliers ...

( 25th Foot) and Frances Anne Wolseley (''née'' Smith). The Wolseleys were an ancient landed family in Wolseley, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

, whose roots can be traced back a thousand years. Wolseley was born at Golden Bridge House, the seat of his mother's family. His paternal grandfather was Rev. William Wolseley, Rector of Tullycorbet, and the third son of Sir Richard Wolseley, 1st Baronet, who sat in the Irish House of Commons

The Irish House of Commons was the lower house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from 1297 until the end of 1800. The upper house was the Irish House of Lords, House of Lords. The membership of the House of Commons was directly elected, ...

for Carlow

Carlow ( ; ) is the county town of County Carlow, in the south-east of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, from Dublin. At the 2022 census of Ireland, 2022 census, it had a population of 27,351, the List of urban areas in the Republic of Ireland, ...

. The family seat was Mount Wolseley in County Carlow

County Carlow ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county located in the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region of Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Carlow is the List of Irish counties by area, second smallest and t ...

. He had four younger sisters and two younger brothers, Frederick Wolseley (1837–1899) and Sir George Wolseley (1839–1921).

Wolseley's father died in 1840 at age 62, leaving his widow and seven children to struggle on his Army pension. Unlike other boys in his class, Wolseley was not sent to England to attend Harrow or Eton, but was instead educated at a local school in Dublin. There, he enjoyed military history and the Latin classics, and excelled at mathematics, history, drawing, reading, and sports. However, the family circumstance forced Wolseley to leave school at age 14, when he found work in a surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the ...

's office, which helped him bring in a salary and continue studying mathematics and geography. The methodical nature of the job, with its need for attention to detail, would prove to serve him well in his future army career.

Early military career

Wolseley first considered a career in the church, but his financial situation meant that he would have needed a wealthy patron to support such an endeavour. Instead he sought acommission

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

in the Army. Unable to afford Sandhurst or buying a commission, Wolseley wrote to his fellow Dubliner, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

The 1st Duke of Wellington, for assistance. Wellington, then the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, later Commander-in-Chief, British Army, or just Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), was (intermittently) the title of the professional head of the English Army from 1660 to 1707 (the English Army, founded in 1645, wa ...

, promised to assist him when he turned 16. However, Wellington apparently overlooked him and did not respond to another letter sent when he was 17. Wolseley unsuccessfully appealed to his secretary, Lord Fitzroy Somerset. The British Army was then recovering from significant casualties in the latest war in South Africa, and Wolseley wrote to Somerset, "I shall be prepared to start at the shortest notice, should your Lordship be pleased to appoint me to a regiment now at the seat of war." His mother then wrote to the Duke to appeal his case, and on 12 March 1852, the 18-year-old Wolseley was gazetted as an ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

in the 12th Foot

The Suffolk Regiment was an infantry regiment of the line in the British Army with a history dating back to 1685. It saw service for three centuries, participating in many wars and conflicts, including the First and Second World Wars, before ...

, in recognition of his father's service.

Just a month after he joined the 12th Foot

The Suffolk Regiment was an infantry regiment of the line in the British Army with a history dating back to 1685. It saw service for three centuries, participating in many wars and conflicts, including the First and Second World Wars, before ...

, Wolseley transferred to the 80th Foot on 13 April 1852, with whom he served in the Second Anglo-Burmese War. He was severely wounded when he was shot in the left thigh with a jingal bullet on 19 March 1853 in the attack on Donabyu, and was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

. Promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

on 16 May 1853 and invalided home, Wolseley transferred to the 84th Regiment of Foot on 27 January 1854, and then to the 90th Light Infantry, at that time stationed in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, on 24 February 1854. He was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on 29 December 1854.

Crimea

Wolseley accompanied the regiment to the Crimea, and landed atBalaklava

Balaklava ( Ukrainian and , , ) is a settlement on the Crimean Peninsula and part of the city of Sevastopol. It is an administrative center of Balaklavsky District that used to be part of the Crimean Oblast before it was transferred to Sevast ...

in December 1854. He was selected to be an assistant engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, build, maintain and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials. They aim to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while ...

, and attached to the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

during the Siege of Sevastopol. Wolseley served throughout the siege, where he was wounded at "the Quarries" on 7 June 1855, and again in the trenches on 30 August 1855, losing an eye.

After the fall of Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

, Wolseley was employed on the quartermaster-general's staff, assisting in the embarkation of the troops and supplies, and was one of the last British soldiers to leave the Crimea in July 1856. For his services he was twice mentioned in despatches, received the war medal with clasp, the 5th class of the French ''Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

'' and the 5th class of the Turkish Order of the Medjidie

Order of the Medjidie (, August 29, 1852 – 1922) was a military and civilian order of the Ottoman Empire. The order was instituted in 1851 by Sultan Abdulmejid I.

History

Instituted in 1851, the order was awarded in five classes, with the Firs ...

.

Six months after joining the 90th Foot at Aldershot

Aldershot ( ) is a town in the Rushmoor district, Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme north-east corner of the county, south-west of London. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Farnborough/Aldershot built-up are ...

, he went with it in March 1857 to join the troops being despatched for the Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Chinese War or ''Arrow'' War, was fought between the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and the United States against the Qing dynasty of China between 1856 and 1860. It was the second major ...

. Wolseley was embarked in the transport ''Transit'', which wrecked in the Strait of Banka. The troops were all saved, but with only their personal arms and minimal ammunition. They were taken to Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, and from there dispatched to Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

on account of the Indian Mutiny.

Indian Rebellion of 1857

Wolseley distinguished himself at the relief of Lucknow under Sir Colin Campbell in November 1857, and in the defence of the Alambagh position under Outram, taking part in the actions of 22 December 1857, of 12 January 1858 and 16 January 1858, and also in the repulse of the grand attack of 21 February 1858. That March, he served at the finalsiege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

and capture of Lucknow. He was then appointed deputy-assistant quartermaster-general on the staff of Sir Hope Grant's Oudh division, and was engaged in all of the operations of the campaign, including the actions of Bari

Bari ( ; ; ; ) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia Regions of Italy, region, on the Adriatic Sea in southern Italy. It is the first most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy. It is a port and ...

, Sarsi, Nawabganj, the capture of Faizabad, the passage of the Gumti and the action of Sultanpur. In the autumn and winter of 1858–59 he took part in the Baiswara, trans- Gogra and trans- Rapti campaigns ending with the complete suppression of the rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

. For his services he was frequently mentioned in dispatches, and having received the Mutiny medal and clasp, he was promoted to brevet major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

on 24 March 1858 and to brevet lieutenant-colonel on 26 April 1859.

During the rebellion, Wolseley displayed strong views towards native peoples, referring to them as "beastly nigger

In the English language, ''nigger'' is a racial slur directed at black people. Starting in the 1990s, references to ''nigger'' have been increasingly replaced by the euphemistic contraction , notably in cases where ''nigger'' is Use–menti ...

s", and remarking that the sepoys had "barrels and barrels of the filth which flows in these niggers' veins".

Wolseley continued to serve on Sir Hope Grant's staff in Oudh, and when Grant was nominated to the command

Command may refer to:

Computing

* Command (computing), a statement in a computer language

* command (Unix), a Unix command

* COMMAND.COM, the default operating system shell and command-line interpreter for DOS

* Command key, a modifier key on A ...

of the British troops in the Anglo-French expedition to China of 1860, accompanied him as the deputy-assistant quartermaster-general. He was present at the action at Sin-ho, the capture of Tang-ku, the storming of the Taku Forts

The Taku Forts or Dagukou Forts (大沽口炮台), also called the Peiho Forts are forts located by the Hai River (Peiho River) estuary in the Binhai New Area, Tianjin, in northeastern China. They are located southeast of the Tianjin urban ...

, the Occupation of Tientsin, the Battle of Pa-to-cheau and the entry into Peking

Beijing, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's most populous national capital city as well as China's second largest city by urban area after Shanghai. It is l ...

(during which the destruction of the Chinese Imperial Old Summer Palace

The Old Summer Palace, also known as Yuanmingyuan () or Yuanmingyuan Park, originally called the Imperial Gardens (), and sometimes called the Winter Palace, was a complex of palaces and gardens in present-day Haidian District, Beijing, China. I ...

was begun). He assisted in the re-embarkation of the troops before the winter set in. He was Mentioned, yet again, in Dispatches, and for his services received the medal and two clasps. On his return home he published the ''Narrative of the War with China'' in 1860. He was given the substantive rank of major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

on 15 February 1861.

American Civil War and Canadian Service

After the outbreak of the

After the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Wolseley was one of the special service officers sent to the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

in November 1861, in connection with the ''Trent'' incident.

In 1862, shortly after the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

, Wolseley took leave from his military duties and went to investigate the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. He befriended Southern sympathizers in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, who found him passage into Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

with a blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usua ...

across the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

. There he met Generals Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War and was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Ho ...

and Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general and military officer who served during the American Civil War. He played a prominent role in nearly all military engagements in the eastern the ...

. He also provided an analysis of Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was an List of slave traders of the United States, American slave trader, active in the lower Mississippi River valley, who served as a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Con ...

. The '' New Orleans Picayune'' (10 April 1892) published Wolseley's ten-page portrayal of Forrest, which condensed much of what was written about him by biographers of the time. This work appeared in the ''Journal of the Southern Historical Society'' in the same year, and is commonly cited today. Wolseley addressed Forrest's role at the Battle of Fort Pillow near Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, in April 1864 in which black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

USCT troops and white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

officers were alleged by some to have been slaughtered after Fort Pillow had been conquered. Wolseley wrote, "I do not think that the fact that one-half of the small garrison of a place taken by assault was either killed or wounded evinced any very unusual bloodthirstiness on the part of the assailants."

Following the end of the Civil War in the United States, Wolseley returned to Canada, where he became a brevet colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

on 5 June 1865 and Assistant Quartermaster-General in Canada with effect from the same date. He was actively employed the following year in the defence of Canada from Fenian raids launched from the United States. He was appointed Deputy Quartermaster-General in Canada on 1 October 1867. In 1869 his ''Soldiers' Pocket Book for Field Service'' was published. In its pages Wolseley gave his opinion on the fitness of the officer corps of his time and other sensitive subjects. For that he was put on half-pay, according to one source.

In 1870, he led the Red River Expedition against the ongoing uprising in the North-West Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of the three territories in Northern Canada. Its estimated pop ...

(present-day Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

), establishing Canadian colonial sovereignty in the province. As part of the North-West Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of the three territories in Northern Canada. Its estimated pop ...

, Manitoba formally entered Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation () was the process by which three British North American provinces—the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick—were united into one federation, called the Name of Canada#Adoption of Dominion, Dominion of Ca ...

in 1870 when the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

transferred its control of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (), or Prince Rupert's Land (), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The right to "sole trade and commerce" over Rupert's Land was granted to Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), based a ...

to the government of the Dominion of Canada. However, British and Canadian authorities ignored the pre-existing Council of Assiniboia and botched negotiations with its Métis

The Métis ( , , , ) are a mixed-race Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada's three Prairie Provinces extending into parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northwest United States. They ha ...

replacement, the provisional government of Manitoba headed by Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis in Canada, Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of ...

, who sought to join Canada on their own terms.

The campaign to put down the uprising was made difficult by challenging terrain and a lack of easily navigable routes, Canada not yet having a transcontinental railway line. Fort Garry (now Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

), the capital of Manitoba, was separated from eastern Canada by the rocks and forests of the Canadian Shield region of western Ontario. The easiest route to Fort Garry that did not pass through the United States was through a network of rivers and lakes extending for from Lake Superior

Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. Lake Michigan–Huron has a larger combined surface area than Superior, but is normally considered tw ...

, rarely traversed by those who were not part of the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

, and where a conventional army would struggle to obtain supplies. In recognition of his achievements in successfully putting an end to the uprising, Wolseley was made a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

on his return home to Britain on the 22 December 1870, and a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregi ...

on 13 March 1871.

Cardwell reforms

Appointed assistant adjutant-general at theWar Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

in 1871, he furthered the Cardwell schemes of army reform. The reforms met strong opposition from senior military figures led by the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge is a hereditary title of nobility in the British royal family, one of several royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom. The title is named after the city of Cambridge in England. It is heritable by agnatic, male descendants by pr ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the Forces

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, later Commander-in-Chief, British Army, or just Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), was (intermittently) the title of the professional head of the English Army from 1660 to 1707 (the English Army, founded in 1645, wa ...

. At their heart was the intent to expand greatly the Army's latent strength by building reserves, both through introducing legislation for 'short service', which allowed soldiers to serve the second part of their term on the reserve, and by bringing militia (i.e. non-regular) battalions into the new localised regimental structure. Resistance in the Army continued and, in a series of subsequent military posts, Wolseley fought publicly as well as inside the Army's structure to implement them, long after the legislation had passed and Cardwell had gone.

Ashanti

On 2 October 1873, Wolseley became Governor ofSierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

British West African Settlements, and the Governor of the Gold Coast. As Governor of both British Territories in West Africa he had charge over the Colonies of Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

, Gold Coast and Western, Eastern, and Northern Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, and in this role, commanded an expedition against the Ashanti Empire

The Asante Empire ( Asante Twi: ), also known as the Ashanti Empire, was an Akan state that lasted from 1701 to 1901, in what is now modern-day Ghana. It expanded from the Ashanti Region to include most of Ghana and also parts of Ivory Coast ...

. Wolseley made all his arrangements at Gold Coast before the arrival of the troops in January 1874. At the Battle of Amoaful on 31 January, Wolseley's expedition defeated the numerically superior Chief Amankwatia's army in a four-hour battle, advancing through thick bush in loose squares. After five days' fighting, ending with the Battle of Ordashu, the British entered the capital Kumasi

Kumasi is a city and the capital of the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly and the Ashanti Region of Ghana. It is the second largest city in the country, with a population of 443,981 as of the 2021 census. Kumasi is located in a rain forest region ...

, which they burned. Wolseley completed the campaign in two months, and re-embarked his troops for home before the unhealthy season began. This campaign made him a household name in Britain. He received the thanks of both houses of Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and a grant of £25,000, was promoted to brevet major-general for distinguished service in the field on 1 April 1874, received the medal and clasp, and was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George on 31 March 1874, and a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

. The freedom of the city of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

was conferred upon him with a sword of honour, and he was made honorary DCL of Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and LL.D of Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

universities.

Service at home, and in Natal, Cyprus, and South Africa

On his return home he was appointed inspector-general of Auxiliary Forces with effect from 1 April 1874. In his role with the Auxiliary Forces, he directed his efforts to building up adequate volunteer reserve forces. Finding himself opposed by the senior military, he wrote a strong memorandum and spoke of resigning when they tried to persuade him to withdraw it. He became a lifelong advocate of the volunteer reserves, later commenting that all military reforms since 1860 in the British Army had first been introduced by the volunteers. Shortly after, in consequence of the indigenous unrest in Natal, he was sent to that colony as governor and general-commanding on 24 February 1875. Wolseley accepted a seat on theCouncil of India

The Council of India (1858 – 1935) was an advisory body to the Secretary of State for India, established in 1858 by the Government of India Act 1858. It was based in London and initially consisted of 15 members. The Council of India was dissolve ...

in November 1876 and was promoted to the substantive rank of major-general on 1 October 1877. He was promoted to brevet lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

on 25 March 1878.

On 12 July 1878, he was appointed the first High Commissioner to Cyprus, a newly acquired possession.

In the following year, he was sent to South Africa to supersede Lord Chelmsford in command of the forces in the Zulu War, and as governor of Natal and the Transvaal and the High Commissioner of Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

. Wolseley with his 'Ashanti Ring' of adherents was sent to Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

. But on arrival in July, he found that the Zulu War was practically over. After effecting a temporary settlement, he went on to the Transvaal. While serving in South Africa, he was promoted to brevet general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

on 4 June 1879. Having reorganized the administration there and reduced King Sekhukhune of the Bapedi

The Pedi or - also known as the Northern Sotho, Basotho ba Lebowa, bakgatla ba dithebe, Transvaal Colony, Transvaal Sotho, Marota, or Dikgoshi - are a Sotho-Tswana peoples, Sotho-Tswana ethnic group native to South Africa, Botswana, and Leso ...

to submission, he returned to London in May 1880. For his services in South Africa, he was awarded the South Africa Medal with clasp, and was advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior military officers or senior civil servants, and the monarch awards it on the advice of His ...

on 19 June 1880. Finally, as if to signify a meteoric rise in Imperial esteem, he was appointed Quartermaster-General to the Forces

The Quartermaster-General to the Forces (QMG) is a senior general in the British Army. The post has become symbolic: the Ministry of Defence organisation charts since 2011 have not used the term "Quartermaster-General to the Forces"; they simply ...

on 1 July 1880. He found that there was still great resistance to the short service system and used his growing public persona to fight for the Cardwell reforms, especially on building up reserves, including making a speech at a banquet in Mansion house in which he commented: '...how an Army raised under the long service system totally disappeared in a few months under the walls of Sevastopol.'

Egypt, the Nile Expedition and Commander-in-Chief

On 1 April 1882, Wolseley was appointed Adjutant-General to the Forces, and, in August of that year, given command of the British forces in Egypt under

On 1 April 1882, Wolseley was appointed Adjutant-General to the Forces, and, in August of that year, given command of the British forces in Egypt under Khedive Tewfik

Mohamed Tewfik Pasha ( ''Muḥammad Tawfīq Bāshā''; April 30 or 15 November 1852 – 7 January 1892), also known as Tawfiq of Egypt, was khedive of Khedivate of Egypt, Egypt and the Turco-Egyptian Sudan, Sudan between 1879 and 1892 and the s ...

to suppress the Urabi Revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperia ...

. Having seized the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

, he then disembarked his troops at Ismailia

Ismailia ( ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city had an estimated population of about 1,434,741 according to the statistics issued by the Cen ...

and, after a very short campaign, completely defeated Urabi Pasha at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir

The Battle of Tel El Kebir (often spelled Tel-El-Kebir) was fought on 13 September 1882 at Tell El Kebir in Egypt, 110 km north-north-east of Cairo. An entrenched Egyptian force under the command of Ahmed ʻUrabi was defeated by a British ...

, thereby suppressing yet another rebellion. For his services, he was promoted to the substantive rank of general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

on 18 November and raised to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

as Baron Wolseley, of Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

and of Wolseley in the County of Stafford. He also received the thanks of Parliament and the Egypt Medal with clasp; the Order of Osmanieh, First Class, as bestowed by the Khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

; and the more dubious accolade of a composition in his honour by poetaster

Poetaster (), like rhymester or versifier, is a derogatory term applied to bad or inferior poets. Specifically, ''poetaster'' has implications of unwarranted pretensions to artistic value. The word was coined in Latin by Erasmus in 1521. It was f ...

William Topaz McGonagall.

On 1 September 1884, Wolseley was again called away from his duties as adjutant-general, to command the Nile Expedition

The Nile Expedition, sometimes called the Gordon Relief Expedition (1884–1885), was a British mission to relieve Major-General Charles George Gordon at Khartoum, Sudan. Gordon had been sent to Sudan to help the Egyptians withdraw their garr ...

for the relief of General Gordon and the besieged garrison at Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

. Wolseley's unusual strategy was to take an expedition by boat up the Nile and then to cross the desert to Khartoum, while the naval boats went on to Khartoum. The expedition arrived too late; Khartoum had been taken, and Gordon was dead. In the spring of 1885, complications with Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

over the Panjdeh Incident occurred, and the withdrawal of that particular expedition followed. For his services there, he received two clasps to his Egyptian medal, the thanks of Parliament, and on 28 September 1885 was created Viscount Wolseley, of Wolseley in the County of Stafford, and a Knight of the Order of St Patrick. At the invitation of the Queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

, the Wolseley family moved from their former home at 6 Hill Street, London to the much grander Ranger's House in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

in autumn 1888.

Wolseley continued at the War Office as Adjutant-General to the Forces until 1890, when he became Commander-in-Chief, Ireland. He was promoted to be a field marshal on 26 May 1894, and appointed by the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

to succeed the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge is a hereditary title of nobility in the British royal family, one of several royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom. The title is named after the city of Cambridge in England. It is heritable by agnatic, male descendants by pr ...

as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, later Commander-in-Chief, British Army, or just Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), was (intermittently) the title of the professional head of the English Army from 1660 to 1707 (the English Army, founded in 1645, wa ...

on 1 November 1895. This was the position to which his great experience in the field and his previous signal success at the War Office itself had fully entitled him, but it was increasingly irrelevant. Field Marshal Viscount Wolseley's powers in that office were, however, limited by a new Order in Council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

, and after holding the appointment for over five years, he handed over the command-in-chief to his fellow field marshal, Earl Roberts, on 3 January 1901. He had also suffered from a serious illness in 1897, from which he never fully recovered.

The unexpectedly large force required for the initial phase of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, was mainly furnished by means of the system of reserves Wolseley had originated. By drawing on regular reservists and volunteer reserves, Britain was able to assemble the largest army it had ever deployed abroad. Nevertheless, the new conditions at the War Office were not to his liking. The fiasco now called Black Week culminated in his dismissal over Christmastide 1900. Upon being released from responsibilities he brought the whole subject before the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

in a speech.

Lord Wolseley was Gold Stick in Waiting to Queen Victoria and took part in the funeral procession following her death in February 1901. He also served as Gold Stick in Waiting to King Edward during his coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

in August 1902.

Honorific, royal appointments and arms

In early 1901, Lord Wolseley was appointed by KingEdward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

to lead a special diplomatic mission to announce the King's accession to the governments of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. During his visit to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

presented him with the Order of Osmanieh set in brilliants.

He was among the original recipients of the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit () is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by Edward VII, admission into the order r ...

in the 1902 Coronation Honours list published on 26 June 1902, and received the order from King Edward VII at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

on 8 August 1902. For time spent as an honorary colonel in the Volunteer Force

The Volunteer Force was a citizen army of part-time rifle, artillery and engineer corps, created as a Social movement, popular movement throughout the British Empire in 1859. Originally highly autonomous, the units of volunteers became increa ...

, he was given the Volunteer Officers' Decoration

The Volunteer Officers' Decoration, post-nominal letters VD, was instituted in 1892 as an award for long and meritorious service by officers of the United Kingdom's Volunteer Force (Great Britain), Volunteer Force. Award of the decoration was di ...

on 11 August 1903. He was also honorary colonel of the 23rd Middlesex Regiment

The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 until 1966. The regiment was formed, as the Duke of Cambridge's Own (Middlesex Regiment), in 1881 as part of the Childers Re ...

from 12 May 1883, honorary colonel of the Queen's Rifle Volunteer Brigade, the Royal Scots

The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment), once known as the Royal Regiment of Foot, was the oldest and most senior infantry regiment line infantry, of the line of the British Army, having been raised in 1633 during the reign of Charles I of England ...

(Lothian Regiment) from 24 April 1889, colonel of the Royal Horse Guards from 29 March 1895 and colonel-in-chief of the Royal Irish Regiment from 20 July 1898.

In retirement, he was a member of the council of the Union-Castle Steamship Company.

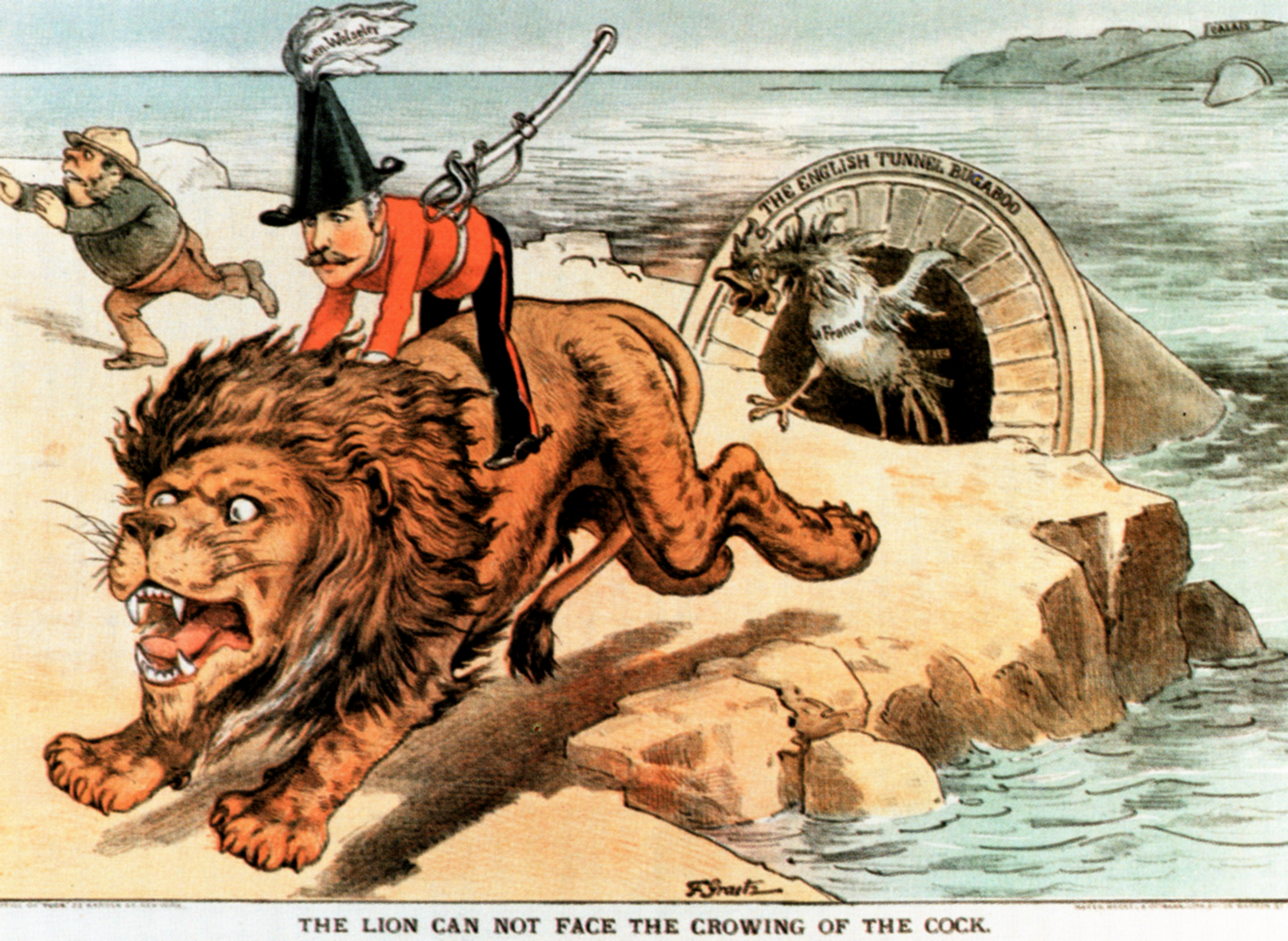

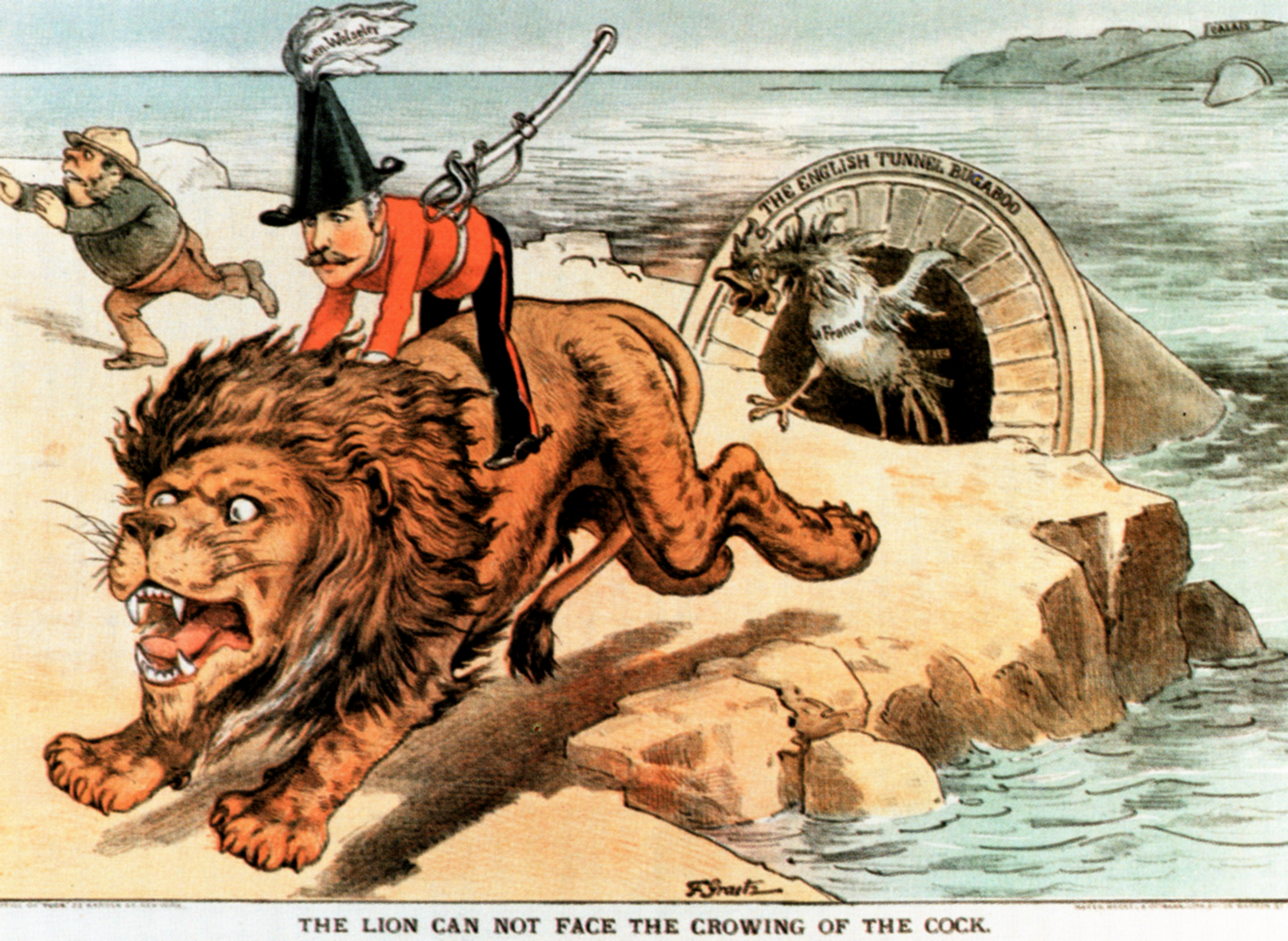

Channel Tunnel

Wolseley was deeply opposed to Sir Edward Watkin's attempt to build a

Wolseley was deeply opposed to Sir Edward Watkin's attempt to build a Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (), sometimes referred to by the Portmanteau, portmanteau Chunnel, is a undersea railway tunnel, opened in 1994, that connects Folkestone (Kent, England) with Coquelles (Pas-de-Calais, France) beneath the English Channel at ...

. He gave evidence to a parliamentary commission that the construction might be "calamitous for England", he added that "No matter what fortifications and defences were built, there would always be the peril of some continental army seizing the tunnel exit by surprise." Various contrivances to satisfy his objections were put forward including looping the line on a viaduct from the Cliffs of Dover and back into them, so that the connection could be bombarded at will by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. For a combination of reasons over 100 years were to pass before a permanent link was made.

Personal life and death

Wolseley was married in 1867 to Louisa (1843–1920), the daughter of Mr. A. Erskine. His only child,Frances

Frances is an English given name or last name of Latin origin. In Latin the meaning of the name Frances is 'from France' or 'the French.' The male version of the name in English is Francis (given name), Francis. The original Franciscus, meaning "F ...

(1872–1936) was an author and founded the College for Lady Gardeners at Glynde. She was heiress to the viscountcy under special remainder, but it became extinct after her death.

In his later years, Lord and Lady Wolseley lived in a grace-and-favour apartment at Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace is a Listed building, Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. Opened to the public, the palace is managed by Historic Royal ...

. He and his wife were wintering at Villa Tourrette, Menton

Menton (; in classical norm or in Mistralian norm, , ; ; or depending on the orthography) is a Commune in France, commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italia ...

on the French Riviera

The French Riviera, known in French as the (; , ; ), is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is considered to be the coastal area of the Alpes-Maritimes department, extending fr ...

, where he fell ill with influenza and returned to England, where he died on 26 March 1913.

He was buried on 31 March 1913 in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, to music played by the band of the 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Regiment, of which he was the first Colonel-in-Chief

Colonel-in-Chief is a ceremonial position in an army regiment. It is in common use in several Commonwealth armies, where it is held by the regiment's patron, usually a member of the royal family.

Some armed forces take a light-hearted approach to ...

.

Legacy

There is an equestrian statue of Wolseley inHorse Guards Parade

Horse Guards Parade is a large Military parade, parade ground off Whitehall in central London (at British national grid reference system, grid reference ). It is the site of the annual ceremonies of Trooping the Colour, which commemorates the K ...

in London. This was sculpted by Sir William Goscombe John R.A. and erected in 1920.

Wolseley Barracks, at London, Ontario

London is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, along the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor. The city had a population of 422,324 according to the 2021 Canadian census. London is at the confluence of the Thames River (Ontario), Thames River and N ...

, is a Canadian military base

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and operations. A military base always provides accommodations for ...

(now officially known as ASU London), established in 1886. It is on the site of Wolseley Hall, the first building constructed by a Canadian Government

The Government of Canada (), formally His Majesty's Government (), is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. The term ''Government of Canada'' refers specifically to the executive, which includes ministers of the Crown ( ...

specifically to house an element of the newly created Permanent Force. Wolseley Barracks has been continuously occupied by the Canadian Army

The Canadian Army () is the command (military formation), command responsible for the operational readiness of the conventional ground forces of the Canadian Armed Forces. It maintains regular forces units at bases across Canada, and is also re ...

since its creation, and has always housed some element of The Royal Canadian Regiment

The Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) is an infantry regiment of the Canadian Army. The regiment consists of four battalions, three in the Regular Force and one in the primary reserve. The RCR is ranked first in the order of precedence amongst Canad ...

. At present, Wolseley Hall is occupied by the Royal Canadian Regiment Museum and the regiment's 4th Battalion, among other tenants. The white pith helmet

The pith helmet, also known as the safari helmet, salacot, sola topee, sun helmet, topee, and topi is a lightweight cloth-covered helmet made of sholapith. The pith helmet originates from the Spanish Empire, Spanish military adaptation of the nat ...

worn as part of the full-dress uniform of the RCR and many other Canadian regiments is known as a Wolseley helmet. Wolseley is also a senior boys house at the Duke of York's Royal Military School.

Field Marshal Lord Wolseley is commemorated by a tablet at St Michael and All Angels Church in Colwich, Staffordshire, a short distance from Shugborough Hall

Shugborough Hall is a stately home near Great Haywood, Staffordshire, England.

The hall is situated on the edge of Cannock Chase, about east of Stafford and from Rugeley. The estate was owned by the Bishops of Lichfield until the dissol ...

and Wolseley Park at Colwich, near Rugeley

Rugeley ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Cannock Chase District, in Staffordshire, England. It lies on the north-eastern edge of Cannock Chase next to the River Trent; it is north of Lichfield, southeast of Stafford, northeast of ...

. The church was the burial place of the Wolseley baronets of Wolseley Park, the ancestral home of the Wolseley family.

W. S. Gilbert, of the musical partnership Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) and to the works they jointly created. The two men collaborated on fourteen com ...

, may have modelled the character of Major-General Stanley in the operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs and including dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, and length of the work. Apart from its shorter length, the oper ...

''The Pirates of Penzance

''The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, W. S. Gilbert. Its official premiere was at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in New York City on 3 ...

'' on Wolseley, and George Grossmith

George Grossmith (9 December 1847 – 1 March 1912) was an English comedian, writer, composer, actor, and singer. His performing career spanned more than four decades. As a writer and composer, he created 18 comic operas, nearly 100 musical ...

, the actor who first created the role in the opening theatrical run, imitated Wolseley's appearance. In another of Gilbert and Sullivan's operettas, ''Patience

or forbearance, is the ability to endure difficult or undesired long-term circumstances. Patience involves perseverance or tolerance in the face of delay, provocation, or stress without responding negatively, such as reacting with disrespect ...

'', Colonel Calverley praises Wolseley in the phrase: "Skill of Sir Garnet in thrashing a cannibal".

The residential areas of Wolseley in Winnipeg, Manitoba

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

, Canada, located in the west central part of the city and of Wolseley, Saskatchewan, Canada, are named after him

The town of Wolseley, Western Cape, South Africa, is named after Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley. It was established on the farm Goedgevonden in 1875 and attained municipal status in 1955; prior to this it was known as Ceres Road.

The Sir Garnet pub in the centre of Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, overlooking the historic market place and city hall, is named after Field Marshal Lord Wolseley. The pub opened in about 1861 and adopted the name Sir Garnet Wolseley in 1874, changed after a brief closing (2011–2012) to Sir Garnet.

Wolseley's uniforms, field marshal's baton and souvenirs from his various campaigns are held in the collections of the Glenbow Museum

The Glenbow Museum is an art and history local museum, regional museum in the city of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The museum focuses on Western Canada, Western Canadian history and culture, including Indigenous perspectives. The Glenbow was establ ...

in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Wolseley maintained a deep interest in notable individuals in early modern European history, and collected items related to many of them (for example, a box from Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

, a watch related to Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, a funerary badge for Admiral Horatio Nelson and General James Wolfe

Major-general James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of ...

's snuff box). These are also held in the collection.

In recognition of his success, an expression arose: "all Sir Garnet" meaning; that everything is in good order.

Selected publications by Viscount Wolseley

* * * * * * * * * * * * *See also

* Royal Horse Guards * British Cavalry *British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

* Essex Regiment

The Essex Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 to 1958. The regiment served in many conflicts such as the Second Boer War and both World War I and World War II, serving with distinction in all three. ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * Hamer, William Spencer. ''The British Army; civil-military relations, 1885–1905'' (1970). * * * Holt, Edgar. "Garnet Wolseley: Soldier of Empire" ''History Today'' (Oct 1958) 8#10 pp 706–713. * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*Primary sources

* *External links

Biography at the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''

* * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wolseley, Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount 1833 births 1913 deaths 19th-century Anglo-Irish people Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom British Army personnel of the Anglo-Egyptian War British Army personnel of the Anglo-Zulu War British Army personnel of the Crimean War British Army personnel of the Mahdist War British Army personnel of the Second Opium War British field marshals British military personnel of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 British Army personnel of the Second Anglo-Burmese War British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War Burials at St Paul's Cathedral Commanders-in-Chief, Ireland Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Governors of Natal Governors of the Gold Coast (British colony) High commissioners of the United Kingdom to Cyprus Irish Freemasons Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights of St Patrick Members of the Council of India Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Privy Council of Ireland Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Military personnel from Dublin (city) People of the Fenian raids People of the Red River Rebellion People of the Sekukuni Campaign Recipients of the Order of the Medjidie, 5th class Royal Horse Guards officers Suffolk Regiment officers Transvaal Colony people Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Governors of the Transvaal Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria