Galileo's Shortest Time Curve Conjecture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian

Based only on uncertain descriptions of the first practical telescope which

Based only on uncertain descriptions of the first practical telescope which

From September 1610, Galileo observed that

From September 1610, Galileo observed that

Cardinal Bellarmine had written in 1615 that the Copernican heliocentrism, Copernican system could not be defended without "a true physical demonstration that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun". Galileo considered his theory of the tides to provide such evidence. This theory was so important to him that he originally intended to call his ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' the ''Dialogue on the Ebb and Flow of the Sea''. The reference to tides was removed from the title by order of the Inquisition.

For Galileo, the tides were caused by the sloshing back and forth of water in the seas as a point on the Earth's surface sped up and slowed down because of the Earth's rotation on its axis and revolution around the Sun. He circulated his first account of the tides in 1616, addressed to Alessandro Orsini (cardinal), Cardinal Orsini. His theory gave the first insight into the importance of the shapes of ocean basins in the size and timing of tides; he correctly accounted, for instance, for the negligible tides halfway along the Adriatic Sea compared to those at the ends. As a general account of the cause of tides, however, his theory was a failure.

If this theory were correct, there would be only one high tide per day. Galileo and his contemporaries were aware of this inadequacy because there are two daily high tides at Venice instead of one, about 12 hours apart. Galileo dismissed this anomaly as the result of several secondary causes including the shape of the sea, its depth, and other factors. Albert Einstein later expressed the opinion that Galileo developed his "fascinating arguments" and accepted them uncritically out of a desire for physical proof of the motion of the Earth. Galileo also dismissed the idea, Tide#History, known from antiquity and by his contemporary Johannes Kepler, that the

Cardinal Bellarmine had written in 1615 that the Copernican heliocentrism, Copernican system could not be defended without "a true physical demonstration that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun". Galileo considered his theory of the tides to provide such evidence. This theory was so important to him that he originally intended to call his ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' the ''Dialogue on the Ebb and Flow of the Sea''. The reference to tides was removed from the title by order of the Inquisition.

For Galileo, the tides were caused by the sloshing back and forth of water in the seas as a point on the Earth's surface sped up and slowed down because of the Earth's rotation on its axis and revolution around the Sun. He circulated his first account of the tides in 1616, addressed to Alessandro Orsini (cardinal), Cardinal Orsini. His theory gave the first insight into the importance of the shapes of ocean basins in the size and timing of tides; he correctly accounted, for instance, for the negligible tides halfway along the Adriatic Sea compared to those at the ends. As a general account of the cause of tides, however, his theory was a failure.

If this theory were correct, there would be only one high tide per day. Galileo and his contemporaries were aware of this inadequacy because there are two daily high tides at Venice instead of one, about 12 hours apart. Galileo dismissed this anomaly as the result of several secondary causes including the shape of the sea, its depth, and other factors. Albert Einstein later expressed the opinion that Galileo developed his "fascinating arguments" and accepted them uncritically out of a desire for physical proof of the motion of the Earth. Galileo also dismissed the idea, Tide#History, known from antiquity and by his contemporary Johannes Kepler, that the

At the time of Galileo's conflict with the Church, the majority of educated people subscribed to the Aristotle, Aristotelian geocentric view that the Earth is the History of the center of the Universe, center of the Universe and the orbit of all heavenly bodies, or Tycho Brahe's new system blending geocentrism with heliocentrism. Opposition to heliocentrism and Galileo's writings on it combined religious and scientific objections. Religious opposition to heliocentrism arose from biblical passages implying the fixed nature of the Earth. Scientific opposition came from Brahe, who argued that if heliocentrism were true, an annual stellar parallax should be observed, though none was at the time. Aristarchus and Copernicus had correctly postulated that parallax was negligible because the stars were so distant. However, Tycho countered that since stars Airy disk, appear to have measurable angular size, if the stars were that distant and their apparent size is due to their physical size, they would be far larger than the Sun. In fact, Magnitude (astronomy)#History, it is not possible to observe the physical size of distant stars without modern telescopes.

Galileo defended heliocentrism based on Sidereus Nuncius, his astronomical observations of 1609. In December 1613, the Grand Duchess Christina of Lorraine, Christina of Florence confronted one of Galileo's friends and followers, Benedetto Castelli, with biblical objections to the motion of the Earth. Prompted by this incident, Galileo wrote a Letter to Benedetto Castelli, letter to Castelli in which he argued that heliocentrism was actually not contrary to biblical texts, and that the Bible was an authority on faith and morals, not science. This letter was not published, but circulated widely. Two years later, Galileo wrote a Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina, letter to Christina that expanded his arguments previously made in eight pages to forty pages.

By 1615, Galileo's writings on heliocentrism had been submitted to the

At the time of Galileo's conflict with the Church, the majority of educated people subscribed to the Aristotle, Aristotelian geocentric view that the Earth is the History of the center of the Universe, center of the Universe and the orbit of all heavenly bodies, or Tycho Brahe's new system blending geocentrism with heliocentrism. Opposition to heliocentrism and Galileo's writings on it combined religious and scientific objections. Religious opposition to heliocentrism arose from biblical passages implying the fixed nature of the Earth. Scientific opposition came from Brahe, who argued that if heliocentrism were true, an annual stellar parallax should be observed, though none was at the time. Aristarchus and Copernicus had correctly postulated that parallax was negligible because the stars were so distant. However, Tycho countered that since stars Airy disk, appear to have measurable angular size, if the stars were that distant and their apparent size is due to their physical size, they would be far larger than the Sun. In fact, Magnitude (astronomy)#History, it is not possible to observe the physical size of distant stars without modern telescopes.

Galileo defended heliocentrism based on Sidereus Nuncius, his astronomical observations of 1609. In December 1613, the Grand Duchess Christina of Lorraine, Christina of Florence confronted one of Galileo's friends and followers, Benedetto Castelli, with biblical objections to the motion of the Earth. Prompted by this incident, Galileo wrote a Letter to Benedetto Castelli, letter to Castelli in which he argued that heliocentrism was actually not contrary to biblical texts, and that the Bible was an authority on faith and morals, not science. This letter was not published, but circulated widely. Two years later, Galileo wrote a Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina, letter to Christina that expanded his arguments previously made in eight pages to forty pages.

By 1615, Galileo's writings on heliocentrism had been submitted to the  Earlier, Pope Urban VIII had personally asked Galileo to give arguments for and against heliocentrism in the book, and to be careful not to advocate heliocentrism. Whether unknowingly or deliberately, Simplicio, the defender of the Aristotelian geocentric view in ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'', was often caught in his own errors and sometimes came across as a fool. Indeed, although Galileo states in the preface of his book that the character is named after a famous Aristotelian philosopher (Simplicius of Cilicia, Simplicius in Latin, "Simplicio" in Italian), the name "Simplicio" in Italian also has the connotation of "simpleton". This portrayal of Simplicio made ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' appear as an advocacy book: an attack on Aristotelian geocentrism and defence of the Copernican theory.

Most historians agree Galileo did not act out of malice and felt blindsided by the reaction to his book. However, the Pope did not take the suspected public ridicule lightly, nor the Copernican advocacy.

Galileo had alienated one of his biggest and most powerful supporters, the Pope, and was called to Rome to defend his writings in September 1632. He finally arrived in February 1633 and was brought before inquisitor Vincenzo Maculani to be Criminal charge, charged. Throughout his trial, Galileo steadfastly maintained that since 1616 he had faithfully kept his promise not to hold any of the condemned opinions, and initially he denied even defending them. However, he was eventually persuaded to admit that, contrary to his true intention, a reader of his ''Dialogue'' could well have obtained the impression that it was intended to be a defence of Copernicanism. In view of Galileo's rather implausible denial that he had ever held Copernican ideas after 1616 or ever intended to defend them in the ''Dialogue'', his final interrogation, in July 1633, concluded with his being threatened with torture if he did not tell the truth, but he maintained his denial despite the threat.

The sentence of the Inquisition was delivered on 22 June. It was in three essential parts:

* Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy" (though he was never formally charged with heresy, relieving him of facing corporal punishment), namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to "abjure, curse and detest" those opinions.

* He was sentenced to formal imprisonment at the pleasure of the Inquisition. On the following day, this was commuted to house arrest, under which he remained for the rest of his life.

* His offending ''Dialogue'' was banned; and in an action not announced at the trial, publication of any of his works was forbidden, including any he might write in the future.

Earlier, Pope Urban VIII had personally asked Galileo to give arguments for and against heliocentrism in the book, and to be careful not to advocate heliocentrism. Whether unknowingly or deliberately, Simplicio, the defender of the Aristotelian geocentric view in ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'', was often caught in his own errors and sometimes came across as a fool. Indeed, although Galileo states in the preface of his book that the character is named after a famous Aristotelian philosopher (Simplicius of Cilicia, Simplicius in Latin, "Simplicio" in Italian), the name "Simplicio" in Italian also has the connotation of "simpleton". This portrayal of Simplicio made ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' appear as an advocacy book: an attack on Aristotelian geocentrism and defence of the Copernican theory.

Most historians agree Galileo did not act out of malice and felt blindsided by the reaction to his book. However, the Pope did not take the suspected public ridicule lightly, nor the Copernican advocacy.

Galileo had alienated one of his biggest and most powerful supporters, the Pope, and was called to Rome to defend his writings in September 1632. He finally arrived in February 1633 and was brought before inquisitor Vincenzo Maculani to be Criminal charge, charged. Throughout his trial, Galileo steadfastly maintained that since 1616 he had faithfully kept his promise not to hold any of the condemned opinions, and initially he denied even defending them. However, he was eventually persuaded to admit that, contrary to his true intention, a reader of his ''Dialogue'' could well have obtained the impression that it was intended to be a defence of Copernicanism. In view of Galileo's rather implausible denial that he had ever held Copernican ideas after 1616 or ever intended to defend them in the ''Dialogue'', his final interrogation, in July 1633, concluded with his being threatened with torture if he did not tell the truth, but he maintained his denial despite the threat.

The sentence of the Inquisition was delivered on 22 June. It was in three essential parts:

* Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy" (though he was never formally charged with heresy, relieving him of facing corporal punishment), namely of having held the opinions that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold and defend an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. He was required to "abjure, curse and detest" those opinions.

* He was sentenced to formal imprisonment at the pleasure of the Inquisition. On the following day, this was commuted to house arrest, under which he remained for the rest of his life.

* His offending ''Dialogue'' was banned; and in an action not announced at the trial, publication of any of his works was forbidden, including any he might write in the future.

According to popular legend, after recanting his theory that the Earth moved around the Sun, Galileo allegedly muttered the rebellious phrase "E pur si muove!, And yet it moves". There was a claim that a 1640s painting by the Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo or an artist of his school, in which the words were hidden until restoration work in 1911, depicts an imprisoned Galileo apparently gazing at the words "E pur si muove" written on the wall of his dungeon. The earliest known written account of the legend dates to a century after his death. Based on the painting, Stillman Drake wrote "there is no doubt now that the famous words were already attributed to Galileo before his death". However, an intensive investigation by astrophysicist Mario Livio has revealed that said painting is most probably a copy of a 1837 painting by the Flemish painter Roman-Eugene Van Maldeghem.

After a period with the friendly Ascanio II Piccolomini, Ascanio Piccolomini (the Archbishop of Siena), Galileo was allowed to return to his villa at

According to popular legend, after recanting his theory that the Earth moved around the Sun, Galileo allegedly muttered the rebellious phrase "E pur si muove!, And yet it moves". There was a claim that a 1640s painting by the Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo or an artist of his school, in which the words were hidden until restoration work in 1911, depicts an imprisoned Galileo apparently gazing at the words "E pur si muove" written on the wall of his dungeon. The earliest known written account of the legend dates to a century after his death. Based on the painting, Stillman Drake wrote "there is no doubt now that the famous words were already attributed to Galileo before his death". However, an intensive investigation by astrophysicist Mario Livio has revealed that said painting is most probably a copy of a 1837 painting by the Flemish painter Roman-Eugene Van Maldeghem.

After a period with the friendly Ascanio II Piccolomini, Ascanio Piccolomini (the Archbishop of Siena), Galileo was allowed to return to his villa at

Galileo continued to receive visitors until 1642, when, after suffering fever and heart palpitations, he died on 8 January 1642, aged 77. The Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando II, wished to bury him in the main body of the Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze, Basilica of Santa Croce, next to the tombs of his father and other ancestors, and to erect a marble mausoleum in his honour.

Galileo continued to receive visitors until 1642, when, after suffering fever and heart palpitations, he died on 8 January 1642, aged 77. The Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando II, wished to bury him in the main body of the Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze, Basilica of Santa Croce, next to the tombs of his father and other ancestors, and to erect a marble mausoleum in his honour.

These plans were dropped, however, after Pope Urban VIII and his nephew, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, protested, because Galileo had been condemned by the Catholic Church for "vehement suspicion of heresy". He was instead buried in a small room next to the novices' chapel at the end of a corridor from the southern transept of the basilica to the sacristy. He was reburied in the main body of the basilica in 1737 after a monument had been erected there in his honour; during this move, three fingers and a tooth were removed from his remains. These fingers are currently on exhibition at the Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy.

These plans were dropped, however, after Pope Urban VIII and his nephew, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, protested, because Galileo had been condemned by the Catholic Church for "vehement suspicion of heresy". He was instead buried in a small room next to the novices' chapel at the end of a corridor from the southern transept of the basilica to the sacristy. He was reburied in the main body of the basilica in 1737 after a monument had been erected there in his honour; during this move, three fingers and a tooth were removed from his remains. These fingers are currently on exhibition at the Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy.

Using his refracting telescope, Galileo observed in late 1609 that the surface of the Moon is not smooth. Early the next year, he observed the four largest moons of Jupiter. Later in 1610, he observed the phases of Venus—a proof of heliocentrism—as well as Saturn, though he thought the planet's rings were two other planets. In 1612, he observed Neptune and noted its motion, but did not identify it as a planet.

Galileo made studies of sunspots, the Milky Way, and made various observations about stars, including how to measure their apparent size without a telescope.

Using his refracting telescope, Galileo observed in late 1609 that the surface of the Moon is not smooth. Early the next year, he observed the four largest moons of Jupiter. Later in 1610, he observed the phases of Venus—a proof of heliocentrism—as well as Saturn, though he thought the planet's rings were two other planets. In 1612, he observed Neptune and noted its motion, but did not identify it as a planet.

Galileo made studies of sunspots, the Milky Way, and made various observations about stars, including how to measure their apparent size without a telescope.

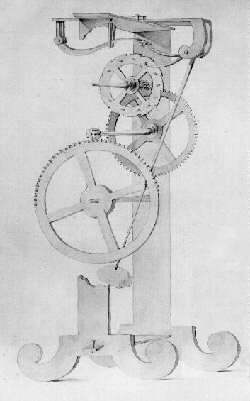

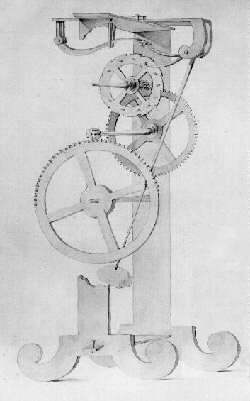

In 1612, having determined the orbital periods of Jupiter's satellites, Galileo proposed that with sufficiently accurate knowledge of their orbits, one could use their positions as a universal clock, and this would make possible the determination of longitude. He worked on this problem from time to time during the remainder of his life, but the practical problems were severe. The method was first successfully applied by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1681 and was later used extensively for large land surveys; this method, for example, was used to survey France, and later by Zebulon Pike of the midwestern United States in 1806. For sea navigation, where delicate telescopic observations were more difficult, the longitude problem eventually required the development of a practical portable marine chronometer, such as that of John Harrison. Late in his life, when totally blind, Galileo designed an escapement mechanism for a pendulum clock (called Galileo's escapement), although no clock using this was built until after the first fully operational pendulum clock was made by

In 1612, having determined the orbital periods of Jupiter's satellites, Galileo proposed that with sufficiently accurate knowledge of their orbits, one could use their positions as a universal clock, and this would make possible the determination of longitude. He worked on this problem from time to time during the remainder of his life, but the practical problems were severe. The method was first successfully applied by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1681 and was later used extensively for large land surveys; this method, for example, was used to survey France, and later by Zebulon Pike of the midwestern United States in 1806. For sea navigation, where delicate telescopic observations were more difficult, the longitude problem eventually required the development of a practical portable marine chronometer, such as that of John Harrison. Late in his life, when totally blind, Galileo designed an escapement mechanism for a pendulum clock (called Galileo's escapement), although no clock using this was built until after the first fully operational pendulum clock was made by

Galileo's theoretical and experimental work on the motions of bodies, along with the largely independent work of Kepler and René Descartes, was a precursor of the classical mechanics developed by Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton. Galileo conducted several experiments with

Galileo's theoretical and experimental work on the motions of bodies, along with the largely independent work of Kepler and René Descartes, was a precursor of the classical mechanics developed by Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton. Galileo conducted several experiments with

According to Stephen Hawking, Galileo probably bears more of the responsibility for the birth of modern science than anybody else, and Albert Einstein called him the father of modern science.

Galileo's astronomical discoveries and investigations into the Copernican theory have led to a lasting legacy which includes the categorisation of the four large moons of

According to Stephen Hawking, Galileo probably bears more of the responsibility for the birth of modern science than anybody else, and Albert Einstein called him the father of modern science.

Galileo's astronomical discoveries and investigations into the Copernican theory have led to a lasting legacy which includes the categorisation of the four large moons of

Galileo's early works describing scientific instruments include the 1586 tract entitled ''The Little Balance'' (''La Billancetta'') describing an accurate balance to weigh objects in air or water and the 1606 printed manual ''Le Operazioni del Compasso Geometrico et Militare'' on the operation of a geometrical and military compass.

His early works on dynamics, the science of motion and mechanics were his ''circa'' 1590 Pisan ''De Motu Antiquiora, De Motu'' (On Motion) and his ''circa'' 1600 Paduan ''Le Meccaniche'' (Mechanics). The former was based on Aristotelian–Archimedean fluid dynamics and held that the speed of gravitational fall in a fluid medium was proportional to the excess of a body's specific weight over that of the medium, whereby in a vacuum, bodies would fall with speeds in proportion to their specific weights. It also subscribed to the Philoponan impetus dynamics in which impetus is self-dissipating and free-fall in a vacuum would have an essential terminal speed according to specific weight after an initial period of acceleration.

Galileo's 1610 ''Sidereus Nuncius, The Starry Messenger'' (''Sidereus Nuncius'') was the first scientific treatise to be published based on observations made through a telescope. It reported his discoveries of:

* the Galilean moons

* the roughness of the Moon's surface

* the existence of a large number of stars invisible to the naked eye, particularly those responsible for the appearance of the Milky Way

* differences between the appearances of the planets and those of the fixed stars—the former appearing as small discs, while the latter appeared as unmagnified points of light

Galileo published a description of sunspots in 1613 entitled ''Letters on Sunspots'' suggesting the Sun and heavens are corruptible. The ''Letters on Sunspots'' also reported his 1610 telescopic observations of the full set of phases of Venus, and his discovery of the puzzling "appendages" of Saturn and their even more puzzling subsequent disappearance. In 1615, Galileo prepared a manuscript known as the "Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina" which was not published in printed form until 1636. This letter was a revised version of the ''Letter to Castelli'', which was denounced by the Inquisition as an incursion upon theology by advocating Copernicanism both as physically true and as consistent with Scripture. In 1616, after the order by the Inquisition for Galileo not to hold or defend the Copernican position, Galileo wrote the "Discourse on the Tides" (''Discorso sul flusso e il reflusso del mare'') based on the Copernican earth, in the form of a private letter to Alessandro Orsini (cardinal), Cardinal Orsini. In 1619, Mario Guiducci, a pupil of Galileo's, published a lecture written largely by Galileo under the title ''Discourse on the Comets'' (''Discorso Delle Comete''), arguing against the Jesuit interpretation of comets.

In 1623, Galileo published ''The Assayer—Il Saggiatore'', which attacked theories based on Aristotle's authority and promoted experimentation and the mathematical formulation of scientific ideas. The book was highly successful and even found support among the higher echelons of the Christian church. Following the success of ''The Assayer'', Galileo published the ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') in 1632. Despite taking care to adhere to the Inquisition's 1616 instructions, the claims in the book favouring Copernican theory and a non-geocentric model of the solar system led to Galileo being tried and banned on publication. Despite the publication ban, Galileo published his ''Two New Sciences, Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences'' (''Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche, intorno a due nuove scienze'') in 1638 in House of Elzevir, Holland, outside the jurisdiction of the Inquisition.

Galileo's early works describing scientific instruments include the 1586 tract entitled ''The Little Balance'' (''La Billancetta'') describing an accurate balance to weigh objects in air or water and the 1606 printed manual ''Le Operazioni del Compasso Geometrico et Militare'' on the operation of a geometrical and military compass.

His early works on dynamics, the science of motion and mechanics were his ''circa'' 1590 Pisan ''De Motu Antiquiora, De Motu'' (On Motion) and his ''circa'' 1600 Paduan ''Le Meccaniche'' (Mechanics). The former was based on Aristotelian–Archimedean fluid dynamics and held that the speed of gravitational fall in a fluid medium was proportional to the excess of a body's specific weight over that of the medium, whereby in a vacuum, bodies would fall with speeds in proportion to their specific weights. It also subscribed to the Philoponan impetus dynamics in which impetus is self-dissipating and free-fall in a vacuum would have an essential terminal speed according to specific weight after an initial period of acceleration.

Galileo's 1610 ''Sidereus Nuncius, The Starry Messenger'' (''Sidereus Nuncius'') was the first scientific treatise to be published based on observations made through a telescope. It reported his discoveries of:

* the Galilean moons

* the roughness of the Moon's surface

* the existence of a large number of stars invisible to the naked eye, particularly those responsible for the appearance of the Milky Way

* differences between the appearances of the planets and those of the fixed stars—the former appearing as small discs, while the latter appeared as unmagnified points of light

Galileo published a description of sunspots in 1613 entitled ''Letters on Sunspots'' suggesting the Sun and heavens are corruptible. The ''Letters on Sunspots'' also reported his 1610 telescopic observations of the full set of phases of Venus, and his discovery of the puzzling "appendages" of Saturn and their even more puzzling subsequent disappearance. In 1615, Galileo prepared a manuscript known as the "Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina" which was not published in printed form until 1636. This letter was a revised version of the ''Letter to Castelli'', which was denounced by the Inquisition as an incursion upon theology by advocating Copernicanism both as physically true and as consistent with Scripture. In 1616, after the order by the Inquisition for Galileo not to hold or defend the Copernican position, Galileo wrote the "Discourse on the Tides" (''Discorso sul flusso e il reflusso del mare'') based on the Copernican earth, in the form of a private letter to Alessandro Orsini (cardinal), Cardinal Orsini. In 1619, Mario Guiducci, a pupil of Galileo's, published a lecture written largely by Galileo under the title ''Discourse on the Comets'' (''Discorso Delle Comete''), arguing against the Jesuit interpretation of comets.

In 1623, Galileo published ''The Assayer—Il Saggiatore'', which attacked theories based on Aristotle's authority and promoted experimentation and the mathematical formulation of scientific ideas. The book was highly successful and even found support among the higher echelons of the Christian church. Following the success of ''The Assayer'', Galileo published the ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') in 1632. Despite taking care to adhere to the Inquisition's 1616 instructions, the claims in the book favouring Copernican theory and a non-geocentric model of the solar system led to Galileo being tried and banned on publication. Despite the publication ban, Galileo published his ''Two New Sciences, Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences'' (''Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche, intorno a due nuove scienze'') in 1638 in House of Elzevir, Holland, outside the jurisdiction of the Inquisition.

online

* * * * * Koyré, Alexandre. "Galileo and Plato." ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 4.4 (1943): 400–428

online

(PDF) * Koyré, Alexandre. "Galileo and the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century." ''Philosophical Review'' 52.4 (1943): 333–348

online

(PDF)

Works in Galileo's Personal Library

at LibraryThing {{DEFAULTSORT:Galilei, Galileo Galileo Galilei, 16th-century Italian mathematicians 16th-century Italian writers 16th-century male writers 16th-century Italian astronomers 17th-century Italian astronomers 17th-century Italian mathematicians 17th-century Italian writers 17th-century Latin-language writers 17th-century male writers 1564 births 1642 deaths Articles containing video clips Ballistics experts Blind people from Italy Burials at Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence Catholicism-related controversies Christian astrologers Copernican Revolution Discoverers of moons Experimental physicists Galileo affair Italian astrologers 16th-century Italian inventors 17th-century Italian physicists Italian Roman Catholics Members of the Lincean Academy Natural philosophers University of Padua faculty Philosophers of science Italian scientific instrument makers Theoretical physicists University of Pisa alumni University of Pisa faculty Writers about religion and science 17th-century Italian inventors 17th-century Italian philosophers

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either o ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate ca ...

and engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

, sometimes described as a polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was born in the city of Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ...

, then part of the Duchy of Florence

The Duchy of Florence ( it, Ducato di Firenze) was an Italian principality that was centred on the city of Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. The duchy was founded after Emperor Charles V restored Medici rule to Florence in 1530. Pope Clement VII, himse ...

. Galileo has been called the "father" of observational astronomy

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical ...

, modern physics, the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

, and modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesop ...

.

Galileo studied speed

In everyday use and in kinematics, the speed (commonly referred to as ''v'') of an object is the magnitude of the change of its position over time or the magnitude of the change of its position per unit of time; it is thus a scalar quantity ...

and velocity

Velocity is the directional speed of an object in motion as an indication of its rate of change in position as observed from a particular frame of reference and as measured by a particular standard of time (e.g. northbound). Velocity i ...

, gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the str ...

and free fall

In Newtonian physics, free fall is any motion of a body where gravity is the only force acting upon it. In the context of general relativity, where gravitation is reduced to a space-time curvature, a body in free fall has no force acting on i ...

, the principle of relativity

In physics, the principle of relativity is the requirement that the equations describing the laws of physics have the same form in all admissible frames of reference.

For example, in the framework of special relativity the Maxwell equations h ...

, inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law o ...

, projectile motion

Projectile motion is a form of motion experienced by an object or particle (a projectile) that is projected in a gravitational field, such as from Earth's surface, and moves along a curved path under the action of gravity only. In the particul ...

and also worked in applied science and technology, describing the properties of pendulums

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward th ...

and "hydrostatic

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body "fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imme ...

balances". He invented the thermoscope

A thermoscope is a device that shows changes in temperature. A typical design is a tube in which a liquid rises and falls as the temperature changes. The modern thermometer gradually evolved from it with the addition of a scale in the early 17th c ...

and various military compasses, and used the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

for scientific observations of celestial objects. His contributions to observational astronomy include telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus

The phases of Venus are the variations of lighting seen on the planet's surface, similar to lunar phases. The first recorded observations of them are thought to have been telescopic observations by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Although the extreme cr ...

, observation of the four largest satellites of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandt ...

, observation of Saturn's rings

The rings of Saturn are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the Solar System. They consist of countless small particles, ranging in size from micrometers to meters, that orbit around Saturn. The ring particles are made almost entir ...

, and analysis of lunar craters

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wor ...

and sunspots

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection. S ...

.

Galileo's championing of Copernican heliocentrism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular ...

(Earth rotating daily and revolving around the Sun) was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and from some astronomers. The matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, respon ...

in 1615, which concluded that heliocentrism was foolish, absurd, and heretical since it contradicted Holy Scripture.

Galileo later defended his views in ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

The ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was tran ...

'' (1632), which appeared to attack Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII ( la, Urbanus VIII; it, Urbano VIII; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death in July 1644. As po ...

and thus alienated both the Pope and the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, who had both supported Galileo up until this point. He was tried by the Inquisition, found "vehemently suspect of heresy", and forced to recant. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest. During this time, he wrote ''Two New Sciences

The ''Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences'' ( it, Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze ) published in 1638 was Galileo Galilei's final book and a scientific testament covering muc ...

'' (1638), primarily concerning kinematics and the strength of materials

The field of strength of materials, also called mechanics of materials, typically refers to various methods of calculating the stresses and strains in structural members, such as beams, columns, and shafts. The methods employed to predict the re ...

, summarizing work he had done around forty years earlier.

Early life and family

Galileo was born inPisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ...

(then part of the Duchy of Florence

The Duchy of Florence ( it, Ducato di Firenze) was an Italian principality that was centred on the city of Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. The duchy was founded after Emperor Charles V restored Medici rule to Florence in 1530. Pope Clement VII, himse ...

), Italy, on 15 February 1564, the first of six children of Vincenzo Galilei

Vincenzo Galilei (born 3 April 1520, Santa Maria a Monte, Italy died 2 July 1591, Florence, Italy) was an Italian lutenist, composer, and music theorist. His children included the astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei and the lute virtuoso ...

, a lutenist

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can refe ...

, composer, and music theorist

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the " rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (k ...

, and Giulia Ammannati

Giulia Ammannati (1 January 1538, Villa Basilica – 1 August 1620, Florence) was a woman from Lucca and Livorno area who is best known as the mother of Galileo Galilei. She was a member of a prosperous family. Her ancestor Iacopo Ammannati was ...

, who had married in 1562. Galileo became an accomplished lutenist himself and would have learned early from his father a scepticism for established authority.

Three of Galileo's five siblings survived infancy. The youngest, Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was in ...

(or Michelagnolo), also became a lutenist and composer who added to Galileo's financial burdens for the rest of his life. Michelangelo was unable to contribute his fair share of their father's promised dowries to their brothers-in-law, who would later attempt to seek legal remedies for payments due. Michelangelo would also occasionally have to borrow funds from Galileo to support his musical endeavours and excursions. These financial burdens may have contributed to Galileo's early desire to develop inventions that would bring him additional income.

When Galileo Galilei was eight, his family moved to Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, but he was left under the care of Muzio Tedaldi for two years. When Galileo was ten, he left Pisa to join his family in Florence and there he was under the tutelage of Jacopo Borghini. He was educated, particularly in logic, from 1575 to 1578 in the Vallombrosa Abbey

Vallombrosa is a Benedictine abbey in the ''comune'' of Reggello (Tuscany, Italy), about 30 km south-east of Florence, in the Apennines, surrounded by forests of beech and firs. It was founded by Florentine nobleman Giovanni Gualberto in 10 ...

, about 30 km southeast of Florence.

Name

Galileo tended to refer to himself only by his given name. At the time, surnames were optional in Italy, and his given name had the same origin as his sometimes-family name, Galilei. Both his given and family name ultimately derive from an ancestor, Galileo Bonaiuti, an important physician, professor, and politician in Florence in the 15th century. Galileo Bonaiuti was buried in the same church, the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, where about 200 years later, Galileo Galilei was also buried. When he did refer to himself with more than one name, it was sometimes as Galileo Galilei Linceo, a reference to his being a member of theAccademia dei Lincei

The Accademia dei Lincei (; literally the "Academy of the Lynx-Eyed", but anglicised as the Lincean Academy) is one of the oldest and most prestigious European scientific institutions, located at the Palazzo Corsini, Rome, Palazzo Corsini on the Vi ...

, an elite pro-science organization in Italy. It was common for mid-sixteenth-century Tuscan families to name the eldest son after the parents' surname. Hence, Galileo Galilei was not necessarily named after his ancestor Galileo Bonaiuti. The Italian male given name "Galileo" (and thence the surname "Galilei") derives from the Latin "Galilaeus", meaning "of Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

", a biblically significant region in Northern Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. Because of that region, the adjective ''galilaios'' (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

Γαλιλαῖος, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

''Galilaeus'', Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

''Galileo''), which means "Galilean", was used in antiquity (particularly by emperor Julian

Julian ( la, Flavius Claudius Julianus; grc-gre, Ἰουλιανός ; 331 – 26 June 363) was Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplato ...

) to refer to Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religi ...

and his followers.

The biblical roots of Galileo's name and surname were to become the subject of a famous pun. In 1614, during the Galileo affair

The Galileo affair ( it, il processo a Galileo Galilei) began around 1610 and culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633. Galileo was prosecuted for his support of heliocentrism, the ...

, one of Galileo's opponents, the Dominican priest Tommaso Caccini Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648) was an Italian Dominican friar and preacher.

Born in Florence as Cosimo Caccini, he entered into the Dominican order of the Catholic Church as a teenager. Caccini began his career in the monastery of San Marco and gra ...

, delivered against Galileo a controversial and influential sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. E ...

. In it he made a point of quoting Acts

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

, "Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven?" (in the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

version found in the Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Bible translations into Latin, Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus&nbs ...

: ''Viri Galilaei, quid statis aspicientes in caelum?'').

Children

Despite being a genuinely pious Roman Catholic, Galileo fathered three children out of wedlock withMarina Gamba

Marina Gamba of Venice ( – ) was the mother of Galileo Galilei's illegitimate children.

Marina Gamba was born around 1570 in Venice.

Relationship with Galileo Galilei

During one of his frequent trips to Venice, Galileo met a young woman nam ...

. They had two daughters, Virginia (born 1600) and Livia (born 1601), and a son, Vincenzo

Vincenzo is an Italian male given name, derived from the Latin name Vincentius (the verb ''vincere'' means to win or to conquer). Notable people with the name include:

Art

*Vincenzo Amato (born 1966), Italian actor and sculptor

* Vincenzo Bell ...

(born 1606).

Due to their illegitimate birth, Galileo considered the girls unmarriageable, if not posing problems of prohibitively expensive support or dowries, which would have been similar to Galileo's previous extensive financial problems with two of his sisters. Their only worthy alternative was the religious life. Both girls were accepted by the convent of San Matteo in Arcetri

Arcetri is a location in Florence, Italy, positioned among the hills south of the city centre.

__TOC__

Landmarks

A number of historic buildings are situated there, including the house of the famous scientist Galileo Galilei (called '' Villa Il Gi ...

and remained there for the rest of their lives.

Virginia took the name Maria Celeste

Sister Maria Celeste (born Virginia Galilei; 16 August 1600 – 2 April 1634) was an Italian nun. She was the daughter of the scientist Galileo Galilei and Marina Gamba.

Biography

Virginia was the eldest of three siblings, wi ...

upon entering the convent. She died on 2 April 1634, and is buried with Galileo at the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence

The ( Italian for 'Basilica of the Holy Cross') is the principal Franciscan church in Florence, Italy, and a minor basilica of the Roman Catholic Church. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 meters south-east of the Duomo. Th ...

. Livia took the name Sister Arcangela and was ill for most of her life. Vincenzo was later legitimised

Legitimation or legitimisation is the act of providing legitimacy. Legitimation in the social sciences refers to the process whereby an act, process, or ideology becomes legitimate by its attachment to norms and values within a given society. ...

as the legal heir of Galileo and married Sestilia Bocchineri.

Career as a scientist

Although Galileo seriously considered the priesthood as a young man, at his father's urging he instead enrolled in 1580 at theUniversity of Pisa

The University of Pisa ( it, Università di Pisa, UniPi), officially founded in 1343, is one of the oldest universities in Europe.

History

The Origins

The University of Pisa was officially founded in 1343, although various scholars place ...

for a medical degree. He was influenced by the lectures of Girolamo Borro

Girolamo Borro (1512 – 26 August 1592) latinized as Hieronomyus Borrius was an Italian philosopher and a professor at the University of Pisa. He belonged to a group of natural philosophers who rejected appeals to the supernatural and occult to e ...

and Francesco Buonamici of Florence. In 1581, when he was studying medicine, he noticed a swinging chandelier

A chandelier (; also known as girandole, candelabra lamp, or least commonly suspended lights) is a branched ornamental light fixture designed to be mounted on ceilings or walls. Chandeliers are often ornate, and normally use incandescent ...

, which air currents shifted about to swing in larger and smaller arcs. To him, it seemed, by comparison with his heartbeat, that the chandelier took the same amount of time to swing back and forth, no matter how far it was swinging. When he returned home, he set up two pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a wikt:pivot, pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, Mechanical equilibrium, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that ...

s of equal length and swung one with a large sweep and the other with a small sweep and found that they kept time together. It was not until the work of Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists ...

, almost one hundred years later, that the tautochrone

A tautochrone or isochrone curve (from Greek prefixes tauto- meaning ''same'' or iso- ''equal'', and chrono ''time'') is the curve for which the time taken by an object sliding without friction in uniform gravity to its lowest point is independ ...

nature of a swinging pendulum was used to create an accurate timepiece.Asimov, Isaac (1964). ''Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology''. Up to this point, Galileo had deliberately been kept away from mathematics, since a physician earned a higher income than a mathematician. However, after accidentally attending a lecture on geometry, he talked his reluctant father into letting him study mathematics and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

instead of medicine. He created a thermoscope

A thermoscope is a device that shows changes in temperature. A typical design is a tube in which a liquid rises and falls as the temperature changes. The modern thermometer gradually evolved from it with the addition of a scale in the early 17th c ...

, a forerunner of the thermometer

A thermometer is a device that measures temperature or a temperature gradient (the degree of hotness or coldness of an object). A thermometer has two important elements: (1) a temperature sensor (e.g. the bulb of a mercury-in-glass thermomete ...

, and, in 1586, published a small book on the design of a hydrostatic

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body "fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imme ...

balance he had invented (which first brought him to the attention of the scholarly world). Galileo also studied ''disegno'', a term encompassing fine art, and, in 1588, obtained the position of instructor in the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno

The Accademia delle Arti del Disegno ("Academy of the Arts of Drawing") is an academy of artists in Florence, Italy. Founded as Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno ("Academy and Company of the Arts of Drawing") on 13 January 1563 by ...

in Florence, teaching perspective and chiaroscuro

Chiaroscuro ( , ; ), in art, is the use of strong contrast (vision), contrasts between light and dark, usually bold contrasts affecting a whole composition. It is also a technical term used by artists and art historians for the use of contrasts ...

. In the same year, upon invitation by the Florentine Academy

The Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze ("academy of fine arts of Florence") is an instructional art academy in Florence, in Tuscany, in central Italy.

It was founded by Cosimo I de' Medici in 1563, under the influence of Giorgio Vasari. M ...

, he presented two lectures, '' On the Shape, Location, and Size of Dante's Inferno'', in an attempt to propose a rigorous cosmological model of Dante's hell

''Inferno'' (; Italian for "Hell") is the first part of Italian writer Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem ''Divine Comedy''. It is followed by '' Purgatorio'' and '' Paradiso''. The ''Inferno'' describes Dante's journey through Hell, g ...

. Being inspired by the artistic tradition of the city and the works of the Renaissance art

Renaissance art (1350 – 1620 AD) is the painting, sculpture, and decorative arts of the period of European history known as the Renaissance, which emerged as a distinct style in Italy in about AD 1400, in parallel with developments which occ ...

ists, Galileo acquired an aesthetic mentality. While a young teacher at the Accademia, he began a lifelong friendship with the Florentine painter Cigoli

Lodovico Cardi (21 September 1559 – 8 June 1613), also known as Cigoli, was an Italian painter and architect of the late Mannerist and early Baroque period, trained and active in his early career in Florence, and spending the last nine years ...

.

In 1589, he was appointed to the chair of mathematics in Pisa. In 1591, his father died, and he was entrusted with the care of his younger brother Michelagnolo. In 1592, he moved to the University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from ...

where he taught geometry, mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects ...

, and astronomy until 1610. During this period, Galileo made significant discoveries in both pure fundamental science

Basic research, also called pure research or fundamental research, is a type of scientific research with the aim of improving scientific theories for better understanding and prediction of natural or other phenomena. In contrast, applied researc ...

(for example, kinematics of motion and astronomy) as well as practical applied science

Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge obtained via conclusions from the method to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted ...

(for example, strength of materials and pioneering the telescope). His multiple interests included the study of astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, which at the time was a discipline tied to the studies of mathematics and astronomy.

Astronomy

Kepler's supernova

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

and others had observed the supernova of 1572. Ottavio Brenzoni's letter of 15 January 1605 to Galileo brought the 1572 supernova and the less bright nova of 1601 to Galileo's notice. Galileo observed and discussed Kepler's Supernova

SN 1604, also known as Kepler's Supernova, Kepler's Nova or Kepler's Star, was a Type Ia supernova that occurred in the Milky Way, in the constellation Ophiuchus. Appearing in 1604, it is the most recent supernova in the Milky Way galaxy to hav ...

in 1604. Since these new stars displayed no detectable diurnal parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby objects ...

, Galileo concluded that they were distant stars, and, therefore, disproved the Aristotelian belief in the immutability of the heavens.

Refracting telescope

Hans Lippershey

Hans Lipperhey (circa 1570 – buried 29 September 1619), also known as Johann Lippershey or Lippershey, was a German- Dutch spectacle-maker. He is commonly associated with the invention of the telescope, because he was the first one who tried to ...

tried to patent in the Netherlands in 1608, Galileo, in the following year, made a telescope with about 3x magnification. He later made improved versions with up to about 30x magnification. With a Galilean telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens as its objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope design was originally used in spyglasses and as ...

, the observer could see magnified, upright images on the Earth—it was what is commonly known as a terrestrial telescope or a spyglass. He could also use it to observe the sky; for a time he was one of those who could construct telescopes good enough for that purpose. On 25 August 1609, he demonstrated one of his early telescopes, with a magnification of about 8 or 9, to Venetian lawmakers. His telescopes were also a profitable sideline for Galileo, who sold them to merchants who found them useful both at sea and as items of trade. He published his initial telescopic astronomical observations in March 1610 in a brief treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions." Treat ...

entitled ''Sidereus Nuncius

''Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually ''Sidereal Messenger'', also ''Starry Messenger'' or ''Sidereal Message'') is a short astronomical treatise (or ''pamphlet'') published in New Latin by Galileo Galilei on March 13, 1610. It was the first published ...

'' (''Starry Messenger'').

Moon

On 30 November 1609, Galileo aimed his telescope at theMoon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

. While not being the first person to observe the Moon through a telescope (English mathematician Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot (; – 2 July 1621), also spelled Harriott, Hariot or Heriot, was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator to whom the theory of refraction is attributed. Thomas Harriot was also recognized for his co ...

had done it four months before but only saw a "strange spottednesse"), Galileo was the first to deduce the cause of the uneven waning as light occlusion from lunar mountains and craters

Crater may refer to:

Landforms

* Impact crater, a depression caused by two celestial bodies impacting each other, such as a meteorite hitting a planet

* Explosion crater, a hole formed in the ground produced by an explosion near or below the surf ...

. In his study, he also made topographical charts, estimating the heights of the mountains. The Moon was not what was long thought to have been a translucent and perfect sphere, as Aristotle claimed, and hardly the first "planet", an "eternal pearl to magnificently ascend into the heavenly empyrian", as put forth by Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

. Galileo is sometimes credited with the discovery of the lunar libration in latitude in 1632, although Thomas Harriot or William Gilbert might have done it before.

A friend of Galileo's, the painter Cigoli, included a realistic depiction of the Moon in one of his paintings, though probably used his own telescope to make the observation.

Jupiter's moons

On 7 January 1610, Galileo observed with his telescope what he described at the time as "three fixed stars, totally invisible by their smallness", all close to Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it. Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these "stars" relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been inexplicable if they had really beenfixed stars

In astronomy, fixed stars ( la, stellae fixae) is a term to name the full set of glowing points, astronomical objects actually and mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the backgro ...

. On 10 January, Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days, he concluded that they were orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such a ...

ing Jupiter: he had discovered three of Jupiter's four largest moons. He discovered the fourth on 13 January. Galileo named the group of four the ''Medicean stars'', in honour of his future patron, Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Cosimo II de' Medici (12 May 1590 – 28 February 1621) was Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1609 until his death. He was the elder son of Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Christina of Lorraine.

For the majority of his twelve-y ...

, and Cosimo's three brothers. Later astronomers, however, renamed them ''Galilean satellites

The Galilean moons (), or Galilean satellites, are the four largest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They were first seen by Galileo Galilei in December 1609 or January 1610, and recognized by him as satellites of Jupiter ...

'' in honour of their discoverer. These satellites were independently discovered by Simon Marius

Simon Marius ( latinized form of Simon Mayr; 10 January 1573 – 5 January 1625) was a German astronomer. He was born in Gunzenhausen, near Nuremberg, but spent most of his life in the city of Ansbach. He is most known for being among the first ...

on 8 January 1610 and are now called Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto Callisto most commonly refers to:

* Callisto (mythology), a nymph

*Callisto (moon), a moon of Jupiter

Callisto may also refer to:

Art and entertainment

*'' Callisto series'', a sequence of novels by Lin Carter

*''Callisto'', a novel by Torsten ...

, the names given by Marius in his ''Mundus Iovialis'' published in 1614.

Galileo's observations of the satellites of Jupiter caused a revolution in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth, and many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing. His observations were confirmed by the observatory of Christopher Clavius

Christopher Clavius, SJ (25 March 1538 – 6 February 1612) was a Jesuit German mathematician, head of mathematicians at the Collegio Romano, and astronomer who was a member of the Vatican commission that accepted the proposed calendar inv ...

and he received a hero's welcome when he visited Rome in 1611. Galileo continued to observe the satellites over the next eighteen months, and by mid-1611, he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their periods—a feat which Johannes Kepler had believed impossible.

Phases of Venus

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

exhibits Phases of Venus, a full set of phases similar to Lunar phase, that of the Moon. The heliocentric model of the Solar System developed by Nicolaus Copernicus predicted that all phases would be visible since the orbit of Venus around the Sun would cause its illuminated hemisphere to face the Earth when it was on the opposite side of the Sun and to face away from the Earth when it was on the Earth-side of the Sun. In geocentric model#Ptolemaic model, Ptolemy's geocentric model, it was impossible for any of the planets' orbits to intersect the spherical shell carrying the Sun. Traditionally, the orbit of Venus was placed entirely on the near side of the Sun, where it could exhibit only crescent and new phases. It was also possible to place it entirely on the far side of the Sun, where it could exhibit only gibbous and full phases. After Galileo's telescopic observations of the crescent, gibbous and full phases of Venus, the Ptolemaic model became untenable. In the early 17th century, as a result of his discovery, the great majority of astronomers converted to one of the various geo-heliocentric planetary models, such as the Tychonic system, Tychonic, Martianus Capella, Capellan and Extended Capellan models, each either with or without a daily rotating Earth. These all explained the phases of Venus without the 'refutation' of full heliocentrism's prediction of stellar parallax. Galileo's discovery of the phases of Venus was thus his most empirically practically influential contribution to the two-stage transition from full geocentrism to full heliocentrism via geo-heliocentrism.

Saturn and Neptune

In 1610, Galileo also observed the planet Saturn, and at first mistook its rings for planets, thinking it was a three-bodied system. When he observed the planet later, Saturn's rings were directly oriented at Earth, causing him to think that two of the bodies had disappeared. The rings reappeared when he observed the planet in 1616, further confusing him. Galileo observed the planet Neptune in 1612. It appears in his notebooks as one of many unremarkable dim stars. He did not realise that it was a planet, but he did note its motion relative to the stars before losing track of it.Sunspots

Galileo made naked-eye and telescopic studies of sunspots. Chapter 2, p. 77: "Drawing of the large sunspot seen by naked-eye by Galileo, and shown in the same way to everybody during the days 19, 20, and 21 August 1612" Their existence raised another difficulty with the unchanging perfection of the heavens as posited in orthodox Aristotelian celestial physics. An apparent annual variation in their trajectories, observed by Francesco Sizzi and others in 1612–1613, also provided a powerful argument against both the Ptolemaic system and the geoheliocentric system of Tycho Brahe. A dispute over claimed priority in the discovery of sunspots, and in their interpretation, led Galileo to a long and bitter feud with the Jesuit Christoph Scheiner. In the middle was Mark Welser, to whom Scheiner had announced his discovery, and who asked Galileo for his opinion. Both of them were unaware of Johannes Fabricius' earlier observation and publication of sunspots.Milky Way and stars

Galileo observed the Milky Way, previously believed to be Nebula, nebulous, and found it to be a multitude of stars packed so densely that they appeared from Earth to be clouds. He located many other stars too distant to be visible with the naked eye. He observed the double star Mizar (star), Mizar in Ursa Major in 1617. In the ''Starry Messenger'', Galileo reported that stars appeared as mere blazes of light, essentially unaltered in appearance by the telescope, and contrasted them to planets, which the telescope revealed to be discs. But shortly thereafter, in his ''Letters on Sunspots'', he reported that the telescope revealed the shapes of both stars and planets to be "quite round". From that point forward, he continued to report that telescopes showed the roundness of stars, and that stars seen through the telescope measured a few seconds of arc in diameter. He also devised a method for measuring the apparent size of a star without a telescope. As described in his ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

The ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was tran ...

'', his method was to hang a thin rope in his line of sight to the star and measure the maximum distance from which it would wholly obscure the star. From his measurements of this distance and of the width of the rope, he could calculate the angle subtended by the star at his viewing point.

In his ''Dialogue'', he reported that he had found the apparent diameter of a star of stellar magnitude, first magnitude to be no more than 5 arcseconds, and that of one of sixth magnitude to be about 5/6 arcseconds. Like most astronomers of his day, Galileo did not recognise that the apparent sizes of stars that he measured were spurious, caused by diffraction and atmospheric distortion, and did not represent the true sizes of stars. However, Galileo's values were much smaller than previous estimates of the apparent sizes of the brightest stars, such as those made by Brahe, and enabled Galileo to counter anti-Copernican arguments such as those made by Tycho that these stars would have to be absurdly large for their annual Stellar parallax, parallaxes to be undetectable. Other astronomers such as Simon Marius, Giovanni Battista Riccioli, and Martin van den Hove, Martinus Hortensius made similar measurements of stars, and Marius and Riccioli concluded the smaller sizes were not small enough to answer Tycho's argument.

Theory of tides

Cardinal Bellarmine had written in 1615 that the Copernican heliocentrism, Copernican system could not be defended without "a true physical demonstration that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun". Galileo considered his theory of the tides to provide such evidence. This theory was so important to him that he originally intended to call his ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' the ''Dialogue on the Ebb and Flow of the Sea''. The reference to tides was removed from the title by order of the Inquisition.

For Galileo, the tides were caused by the sloshing back and forth of water in the seas as a point on the Earth's surface sped up and slowed down because of the Earth's rotation on its axis and revolution around the Sun. He circulated his first account of the tides in 1616, addressed to Alessandro Orsini (cardinal), Cardinal Orsini. His theory gave the first insight into the importance of the shapes of ocean basins in the size and timing of tides; he correctly accounted, for instance, for the negligible tides halfway along the Adriatic Sea compared to those at the ends. As a general account of the cause of tides, however, his theory was a failure.

If this theory were correct, there would be only one high tide per day. Galileo and his contemporaries were aware of this inadequacy because there are two daily high tides at Venice instead of one, about 12 hours apart. Galileo dismissed this anomaly as the result of several secondary causes including the shape of the sea, its depth, and other factors. Albert Einstein later expressed the opinion that Galileo developed his "fascinating arguments" and accepted them uncritically out of a desire for physical proof of the motion of the Earth. Galileo also dismissed the idea, Tide#History, known from antiquity and by his contemporary Johannes Kepler, that the