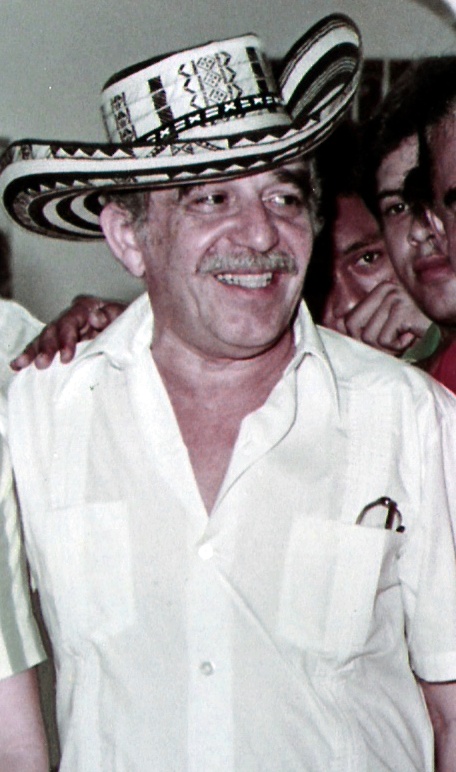

Gabriel José García Márquez (; 6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian writer and journalist, known affectionately as Gabo () or Gabito () throughout Latin America. Considered one of the most significant authors of the 20th century, particularly in the

Spanish language

Spanish () or Castilian () is a Romance languages, Romance language of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin spoken on the Iberian Peninsula of Europe. Today, it is a world language, gl ...

, he was awarded the 1972

Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the

1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. He pursued a self-directed education that resulted in leaving law school for a career in journalism. From early on he showed no inhibitions in his criticism of Colombian and foreign politics. In 1958, he married

Mercedes Barcha Pardo;

they had two sons,

Rodrigo

Rodrigo () is a Spanish, Portuguese and Italian name derived from the Germanic name ''Roderick'' ( Gothic ''*Hroþareiks'', via Latinized ''Rodericus'' or ''Rudericus''), given specifically in reference to either King Roderic (d. 712), the la ...

and Gonzalo.

García Márquez started as a journalist and wrote many acclaimed non-fiction works and short stories. He is best known for his novels, such as

''No One Writes to the Colonel'' (1961), ''

One Hundred Years of Solitude'' (1967), which has sold over fifty million copies worldwide, ''

Chronicle of a Death Foretold'' (1981), and ''

Love in the Time of Cholera'' (1985). His works have achieved significant critical acclaim and widespread commercial success, most notably for popularizing a literary style known as

magic realism, which uses magical elements and events in otherwise ordinary and realistic situations. Some of his works are set in the fictional village of

Macondo (mainly inspired by his birthplace,

Aracataca), and most of them explore the theme of

solitude

Solitude, also known as social withdrawal, is a state of seclusion or isolation, meaning lack of socialisation. Effects can be either positive or negative, depending on the situation. Short-term solitude is often valued as a time when one may wo ...

. He is the most-translated Spanish-language author.

In 1982, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, "for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent's life and conflicts". He was the fourth Latin American to receive the honor, following Chilean poets

Gabriela Mistral (1945) and

Pablo Neruda (1971), as well as Guatemalan novelist

Miguel Ángel Asturias (1967). Alongside

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

, García Márquez is regarded as one of the most renowned Latin American authors in history.

Upon García Márquez's death in April 2014,

Juan Manuel Santos

Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (; born 10 August 1951) is a Colombian politician who was the President of Colombia from 2010 to 2018. He was the sole recipient of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize.

An economist by training and a journalist by trade, S ...

, the president of Colombia, called him "the greatest Colombian who ever lived."

Biography

Early life

Gabriel García Márquez was born on 6 March 1927 in the small town of

Aracataca, in the

Caribbean region of Colombia, to Gabriel Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán. Soon after García Márquez was born, his father became a pharmacist and moved with his wife to the nearby large port city of

Barranquilla

Barranquilla () is the capital district of the Atlántico department in Colombia. It is located near the Caribbean Sea and is the largest city and third port in the Caribbean region of Colombia, Caribbean coast region; as of 2018, it had a popul ...

, leaving young Gabriel in Aracataca. He was raised by his maternal grandparents, Doña Tranquilina Iguarán and Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Mejía. In December 1936, his father took him and his brother to

Sincé. However, when his grandfather died in March 1937, the family moved first (back) to Barranquilla and then on to

Sucre

Sucre (; ) is the ''de jure'' capital city of Bolivia, the capital of the Chuquisaca Department and the sixth most populous city in Bolivia. Located in the south-central part of the country, Sucre lies at an elevation of . This relatively high ...

, where his father started a pharmacy.

When his parents had fallen in love, their relationship was met with resistance from Luisa Santiaga Márquez's father, the Colonel. Gabriel Eligio García was not the man the Colonel had envisioned winning the heart of his daughter: Gabriel Eligio was a

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

, and had the reputation of being a womanizer.

Gabriel Eligio wooed Luisa with violin serenades, love poems, countless letters, and even telephone messages after her father sent her away with the intention of separating the young couple. Her parents tried everything to get rid of the man, but he kept coming back, and it was obvious their daughter was committed to him.

Her family finally capitulated and gave her permission to marry him (The tragicomic story of their courtship would later be adapted and recast as ''

Love in the Time of Cholera''.)

[

Since García Márquez's parents were more or less strangers to him for the first few years of his life, his grandparents influenced his early development very strongly.]

Education and adulthood

After arriving at Sucre

Sucre (; ) is the ''de jure'' capital city of Bolivia, the capital of the Chuquisaca Department and the sixth most populous city in Bolivia. Located in the south-central part of the country, Sucre lies at an elevation of . This relatively high ...

, it was decided that García Márquez should start his formal education and he was sent to an internship in Barranquilla

Barranquilla () is the capital district of the Atlántico department in Colombia. It is located near the Caribbean Sea and is the largest city and third port in the Caribbean region of Colombia, Caribbean coast region; as of 2018, it had a popul ...

, a port on the mouth of the Río Magdalena. There, he gained a reputation of being a timid boy who wrote humorous poems and drew humorous comic strips. Serious and little interested in athletic activities, he was called ''El Viejo'' by his classmates.Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a novelist and writer from Prague who was Jewish, Austrian, and Czech and wrote in German. He is widely regarded as a major figure of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of Litera ...

, at the time incorrectly thought to have been translated by Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

.

Journalism

García Márquez began his career as a journalist while studying law at the National University of Colombia

The National University of Colombia () is a national public research university in Colombia, with general campuses in Bogotá, Medellín, Manizales and Palmira, and satellite campuses in Leticia, San Andrés, Arauca, Tumaco, and La Paz, ...

. In 1948 and 1949, he wrote for '' El Universal'' in Cartagena. From 1950 until 1952, he wrote a "whimsical" column under the name of "''Septimus''" for the local paper '' El Heraldo'' in Barranquilla

Barranquilla () is the capital district of the Atlántico department in Colombia. It is located near the Caribbean Sea and is the largest city and third port in the Caribbean region of Colombia, Caribbean coast region; as of 2018, it had a popul ...

. García Márquez noted of his time at ''El Heraldo'', "I'd write a piece and they'd pay me three pesos for it, and maybe an editorial for another three." During this time he became an active member of the informal group of writers and journalists known as the Barranquilla Group, an association that provided great motivation and inspiration for his literary career. He worked with inspirational figures such as Ramon Vinyes, whom García Márquez depicted as an Old Catalan who owns a bookstore in ''One Hundred Years of Solitude''.Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer and one of the most influential 20th-century modernist authors. She helped to pioneer the use of stream of consciousness narration as a literary device.

Vir ...

and William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

. Faulkner's narrative techniques, historical themes and use of rural locations influenced many Latin American authors.El Espectador

''El Espectador'' () is a nationally circulated Colombian newspaper founded by Fidel Cano Gutiérrez in 1887 in Medellín and published since 1915 in Bogotá. It was initially published twice a week, 500 issues each, but some years later became ...

''.Caracas

Caracas ( , ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas (CCS), is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern p ...

, Venezuela.

Politics

García Márquez was a "committed leftist" throughout his life, adhering to socialist beliefs. In 1991, he published ''Changing the History of Africa'', an admiring study of Cuban activities in the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War () was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war began immediately after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. It was a power struggle between two for ...

and the larger South African Border War

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Angol ...

. He maintained a close but "nuanced" friendship with Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

, praising the achievements of the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

but criticizing aspects of governance and working to "soften heroughest edges" of the country. García Márquez's political and ideological views were shaped by his grandfather's stories.

''The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor''

Ending in controversy, his last domestically written editorial for ''El Espectador'' was a series of 14 news articlesGustavo Rojas Pinilla

Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (12 March 1900 – 17 January 1975) was a Colombian National Army of Colombia, army general, civil engineer and politician who ruled as List of presidents of Colombia, 19th President of Colombia in a military dictatorship f ...

and was later shut down by Colombian authorities.

QAP

García Márquez was one of the original founders of QAP, a Colombian newscast that aired between 1992 and 1997. He was attracted to the project by the promise of editorial and journalistic independence.

Marriage and family

García Márquez met Mercedes Barcha while she was at school; he was 12 and she was 9.Greyhound

The English Greyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a dog breed, breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Some are kept as show dogs or pets.

Greyhounds are defined as a tall, muscular, smooth-c ...

bus throughout the southern United States and eventually settled in Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

. García Márquez had always wanted to see the Southern United States because it inspired the writings of William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

.

''Leaf Storm''

''Leaf Storm'' (''La Hojarasca'') is García Márquez's first novella and took seven years to find a publisher, finally being published in 1955. García Márquez notes that "of all that he had written (as of 1973), ''Leaf Storm'' was his favorite because he felt that it was the most sincere and spontaneous." All the events of the novella take place in one room, during a half-hour period on Wednesday 12 September 1928. It is the story of an old colonel (similar to García Márquez's own grandfather) who tries to give a proper Christian burial to an unpopular French doctor. The colonel is supported only by his daughter and grandson. The novella explores the child's first experience with death by following his stream of consciousness. The book reveals the perspective of Isabel, the Colonel's daughter, which provides a feminine point of view.

''In Evil Hour''

''In Evil Hour'' (''La mala hora''), García Márquez's second novel, was published in 1962. Its formal structure is based on novels such as Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer and one of the most influential 20th-century modernist authors. She helped to pioneer the use of stream of consciousness narration as a literary device.

Vir ...

's ''Mrs Dalloway

''Mrs Dalloway'' is a novel by Virginia Woolf published on 14 May 1925. It details a day in the life of Clarissa Dalloway, a fictional upper-class woman in post-First World War England.

The working title of ''Mrs Dalloway'' was ''The Hours ...

''. The narrative begins on the saint's day of St Francis of Assisi, but the murders that follow are far from the saint's message of peace. The story interweaves characters and details from García Márquez's other writings such as ''Artificial Roses'', and comments on literary genres such as whodunnit detective stories. Some of the characters and situations found in ''In Evil Hour'' re-appear in '' One Hundred Years of Solitude''.

''One Hundred Years of Solitude''

From when he was 18, García Márquez had wanted to write a novel based on his grandparents' house where he grew up. However, he struggled with finding an appropriate tone and put off the idea until one day the answer hit him while driving his family to Acapulco

Acapulco de Juárez (), commonly called Acapulco ( , ; ), is a city and Port of Acapulco, major seaport in the Political divisions of Mexico, state of Guerrero on the Pacific Coast of Mexico, south of Mexico City. Located on a deep, semicirc ...

. He turned the car around and the family returned home so he could begin writing. He sold his car so his family would have money to live on while he wrote. Writing the novel took far longer than he expected; he wrote every day for 18 months. His wife had to ask for food on credit from their butcher and baker as well as nine months of rent on credit from their landlord. During the 18 months of writing, García Márquez met with two couples, Eran Carmen and Álvaro Mutis, and María Luisa Elío and Jomí García Ascot, every night and discussed the progress of the novel, trying out different versions.Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

that should be required reading for the entire human race," and hundreds of articles and books of literary critique have been published in response to it. Despite the many accolades the book received, García Márquez tended to downplay its success. He once remarked: "Most critics don't realize that a novel like ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' is a bit of a joke, full of signals to close friends, and so, with some pre-ordained right to pontificate they take on the responsibility of decoding the book and risk making terrible fools of themselves."

Fame

After writing ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' García Márquez returned to Europe, this time bringing along his family, to live in

After writing ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' García Márquez returned to Europe, this time bringing along his family, to live in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Spain, for seven years.[ The international recognition García Márquez earned with the publication of the novel led to his ability to act as a facilitator in several negotiations between the ]Colombian government

The Government of Colombia is a republic with separation of powers into executive, judicial and legislative branches.

Its legislature has a congress,

its judiciary has a supreme court, and

its executive branch has a president.

The citiz ...

and the guerrillas, including the former 19th of April Movement

The 19th of April Movement (), or M-19, was a Colombian urban guerrilla movement active in the late 1970s and 1980s. After its demobilization in 1990 it became a political party, the M-19 Democratic Alliance (), or AD/M-19.

The M-19 tra ...

(M-19), and the current FARC and ELN organizations. The popularity of his writing also led to friendships with powerful leaders, including one with former Cuban president Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and President of Cuba, president ...

, which has been analyzed in ''Gabo and Fidel: Portrait of a Friendship.'' It was during this time that he was punched in the face by Mario Vargas Llosa

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquess of Vargas Llosa (28 March 1936 – 13 April 2025) was a Peruvian novelist, journalist, essayist and politician. Vargas Llosa was one of the most significant Latin American novelists and essayists a ...

in what became one of the largest feuds in modern literature. In an interview with Claudia Dreifus in 1982 García Márquez noted his relationship with Castro was mostly based on literature: "Ours is an intellectual friendship. It may not be widely known that Fidel is a very cultured man. When we're together, we talk a great deal about literature." This relationship was criticized by Cuban exile writer Reinaldo Arenas, in his 1992 memoir ''Antes de que Anochezca'' ('' Before Night Falls'').

Due to his newfound fame and his outspoken views on US imperialism, García Márquez was labeled as a subversive and for many years was denied visas by US immigration authorities. After Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

was elected US president, he lifted the travel ban and cited ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' as his favorite novel.[

]

''Autumn of the Patriarch''

García Márquez was inspired to write a dictator novel when he witnessed the flight of Venezuelan dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez. He said, "it was the first time we had seen a dictator fall in Latin America." García Márquez began writing ''Autumn of the Patriarch'' (''El otoño del patriarca'') in 1968 and said it was finished in 1971; however, he continued to embellish the dictator novel until 1975 when it was published in Spain. According to García Márquez, the novel is a "poem on the solitude of power" as it follows the life of an eternal dictator known as the General. The novel is developed through a series of anecdotes related to the life of the General, which do not appear in chronological order.My intention was always to make a synthesis of all the Latin American dictators, but especially those from the Caribbean. Nevertheless, the personality of Juan Vicente Gomez f Venezuelawas so strong, in addition to the fact that he exercised a special fascination over me, that undoubtedly the Patriarch has much more of him than anyone else.

After ''Autumn of the Patriarch'' was published García Márquez and his family moved from Barcelona to Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

[ and García Márquez pledged not to publish again until the Chilean Dictator ]Augusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean military officer and politician who was the dictator of Military dictatorship of Chile, Chile from 1973 to 1990. From 1973 to 1981, he was the leader ...

was deposed. All the same, he published ''Chronicle of a Death Foretold'' while Pinochet was still in power, as he "could not remain silent in the face of injustice and repression."

''The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother''

''The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother'' () presents the story of a young mulatto girl who dreams of freedom, but cannot escape the reach of her avaricious grandmother. Eréndira and her grandmother make an appearance in an earlier novel, '' One Hundred Years of Solitude''.

''The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother'' was published in 1972. The novella was adapted to the 1983

1983 saw both the official beginning of the Internet and the first mobile cellular telephone call.

Events January

* January 1 – The migration of the ARPANET to TCP/IP is officially completed (this is considered to be the beginning of the ...

art film '' Eréndira'', directed by Ruy Guerra.

''Chronicle of a Death Foretold''

''Chronicle of a Death Foretold'' (''Crónica de una muerte anunciada''), which literary critic Ruben Pelayo called a combination of journalism, realism and detective story, is inspired by a real-life murder that took place in Sucre

Sucre (; ) is the ''de jure'' capital city of Bolivia, the capital of the Chuquisaca Department and the sixth most populous city in Bolivia. Located in the south-central part of the country, Sucre lies at an elevation of . This relatively high ...

, Colombia, in 1951, but García Márquez maintained that nothing of the actual events remains beyond the point of departure and the structure. The character of Santiago Nasar is based on a good friend from García Márquez's childhood, Cayetano Gentile Chimento.

''Love in the Time of Cholera''

''Love in the Time of Cholera'' (''El amor en los tiempos del cólera'') was first published in 1985. It is considered a non-traditional love story as "lovers find love in their 'golden years'—in their seventies, when death is all around them".

''Love in the Time of Cholera'' is based on the stories of two couples. The young love of Fermina Daza and Florentino Ariza is based on the love affair of García Márquez's parents.[ The love of old people is based on a newspaper story about the death of two Americans, who were almost 80 years old, who met every year in Acapulco. They were out in a boat one day and were murdered by the boatman with his oars. García Márquez notes, "Through their death, the story of their secret romance became known. I was fascinated by them. They were each married to other people."

]

''News of a Kidnapping''

''News of a Kidnapping'' (''Noticia de un secuestro'') was first published in 1996. It examines a series of related kidnapping

Kidnapping or abduction is the unlawful abduction and confinement of a person against their will, and is a crime in many jurisdictions. Kidnapping may be accomplished by use of force or fear, or a victim may be enticed into confinement by frau ...

s and narcoterrorist actions committed in the early 1990s in Colombia by the Medellín Cartel, a drug cartel founded and operated by Pablo Escobar

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (; ; 1 December 19492 December 1993) was a Colombian drug lord, narcoterrorist, and politician who was the founder and leader of the Medellín Cartel. Dubbed the "King of Cocaine", Escobar was one of the wealthie ...

. The text recounts the kidnapping, imprisonment, and eventual release of prominent figures in Colombia, including politicians and members of the press.

The original idea was proposed to García Márquez by the former minister for education Maruja Pachón Castro and Colombian diplomat Luis Alberto Villamizar Cárdenas, both of whom were among the many victims of Pablo Escobar's attempt to pressure the government to stop his extradition

In an extradition, one Jurisdiction (area), jurisdiction delivers a person Suspect, accused or Conviction, convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforc ...

by committing a series of kidnappings, murders and terrorist actions.

''Living to Tell the Tale'' and ''Memories of My Melancholy Whores''

In 2002 García Márquez published the memoir ''Vivir para contarla'', the first of a projected three-volume autobiography. Edith Grossman

Edith Marion Grossman (née Dorph; March 22, 1936 – September 4, 2023) was an American literary translator. Known for her work translating Latin American literature, Latin American and Spanish literature to English, she translated the works o ...

's English translation, '' Living to Tell the Tale'', was published in November 2003. October 2004 brought the publication of a novel, '' Memories of My Melancholy Whores'' (''Memoria de mis putas tristes''), a love story that follows the romance of a 90-year-old man and a child forced into prostitution. ''Memories of My Melancholy Whores'' caused controversy in Iran, where it was banned after an initial 5,000 copies were printed and sold.

Film and opera

Critics often describe the language that García Márquez's imagination produces as visual or graphic,Carlos Fuentes

Carlos Fuentes Macías (; ; November 11, 1928 – May 15, 2012) was a Mexican novelist and essayist. Among his works are ''The Death of Artemio Cruz'' (1962), '' Aura'' (1962), '' Terra Nostra'' (1975), '' The Old Gringo'' (1985) and '' Christop ...

on Juan Rulfo's ''El gallo de oro''.Four Weddings and a Funeral

''Four Weddings and a Funeral'' is a 1994 British romantic comedy film directed by Mike Newell. It is the first of several films by screenwriter Richard Curtis to star Hugh Grant, and follows the adventures of Charles (Grant) and his circle of ...

'') filmed '' Love in the Time of Cholera'' in Cartagena, Colombia, with the screenplay written by Ronald Harwood ('' The Pianist''). The film was released in the U.S. on 16 November 2007.

Later life and death

Declining health

In 1999 García Márquez was misdiagnosed with pneumonia instead of lymphatic cancer.[

In May 2008 it was announced that García Márquez was finishing a new "novel of love" that had yet to be given a title, to be published by the end of the year. However, in April 2009 his agent, Carmen Balcells, told the Chilean newspaper '' La Tercera'' that García Márquez was unlikely to write again.][ This was disputed by Random House Mondadori editor Cristobal Pera, who stated that García Márquez was completing a new novel whose Spanish title was to be (). In 2023 it was announced that the novel, whose English title was to be '' Until August'', would be released posthumously in 2024.][

In 2012 his brother Jaime announced that García Márquez was suffering from ]dementia

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that affects a person's ability to perform activities of daily living, everyday activities. This typically invo ...

.

In April 2014, García Márquez was hospitalized in Mexico. He had infections in his lungs and his urinary tract, and was suffering from dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild deh ...

. He was responding well to antibiotics. Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto wrote on Twitter, "I wish him a speedy recovery". Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos

Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (; born 10 August 1951) is a Colombian politician who was the President of Colombia from 2010 to 2018. He was the sole recipient of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize.

An economist by training and a journalist by trade, S ...

said his country was thinking of the author and said in a tweet: "All of Colombia wishes a speedy recovery to the greatest of all time: Gabriel García Márquez."

Death

García Márquez died of pneumonia at the age of 87 on 17 April 2014, in Mexico City. His death was confirmed by Fernanda Familiar on Twitter,Juan Manuel Santos

Juan Manuel Santos Calderón (; born 10 August 1951) is a Colombian politician who was the President of Colombia from 2010 to 2018. He was the sole recipient of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize.

An economist by training and a journalist by trade, S ...

mentioned: "One Hundred Years of Solitude and sadness for the death of the greatest Colombian of all time".Palacio de Bellas Artes

The Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) is a prominent cultural center in Mexico City. It hosts performing arts events, literature events and plastic arts galleries and exhibitions (including important permanent Mexican murals). "Bella ...

, where the memorial ceremony was held. Earlier, residents in his home town of Aracataca in Colombia's Caribbean region held a symbolic funeral. In February 2015, the heirs of Gabriel García Márquez deposited a legacy of the writer in his Memoriam in the Caja de las Letras of the Instituto Cervantes

Instituto Cervantes (, the Cervantes Institute) is a worldwide nonprofit organization created by the Spanish government in 1991. It is named after Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), the author of ''Don Quixote'' and perhaps the most important fi ...

.

Style

In every book I try to make a different path ... . One doesn't choose the style. You can investigate and try to discover what the best style would be for a theme. But the style is determined by the subject, by the mood of the times. If you try to use something that is not suitable, it just won't work. Then the critics build theories around that and they see things I hadn't seen. I only respond to our way of life, the life of the Caribbean.

García Márquez was noted for leaving out seemingly important details and events so the reader is forced into a more participatory role in the story development. For example, in '' No One Writes to the Colonel'', the main characters are not given names. This practice is influenced by Greek tragedies, such as '' Antigone'' and ''Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' (, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles. While some scholars have argued that the play was first performed , this is highly uncertain. Originally, to ...

'', in which important events occur off-stage and are left to the audience's imagination.

Realism and magical realism

Reality is an important theme in all of García Márquez's works. He said of his early works (with the exception of ''Leaf Storm''), "''Nobody Writes to the Colonel'', ''In Evil Hour'', and ''Big Mama's Funeral'' all reflect the reality of life in Colombia and this theme determines the rational structure of the books. I don't regret having written them, but they belong to a kind of premeditated literature that offers too static and exclusive a vision of reality."

In his other works he experimented more with less traditional approaches to reality, so that "the most frightful, the most unusual things are told with the deadpan expression". A commonly cited example is the physical and spiritual ascending into heaven of a character while she is hanging the laundry out to dry in '' One Hundred Years of Solitude.'' The style of these works fits in the "marvellous realm" described by the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier and was labeled as magical realism

Magical realism, magic realism, or marvelous realism is a style or genre of fiction and art that presents a realistic view of the world while incorporating magical elements, often blurring the lines between speculation and reality. ''Magical rea ...

. Literary critic Michael Bell proposes an alternative understanding for García Márquez's style, as the category magic realism is criticized for being dichotomizing and exoticizing, "what is really at stake is a psychological suppleness which is able to inhabit unsentimentally the daytime world while remaining open to the promptings of those domains which modern culture has, by its own inner logic, necessarily marginalised or repressed." García Márquez and his friend Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza discuss his work in a similar way,The way you treat reality in your books ... has been called magical realism. I have the feeling your European readers are usually aware of the magic of your stories but fail to see the reality behind it .... This is surely because their rationalism prevents them seeing that reality isn't limited to the price of tomatoes and eggs.

Themes

Solitude

The theme of solitude runs through much of García Márquez's works. As Pelayo notes, "''Love in the Time of Cholera'', like all of Gabriel García Márquez's work, explores the solitude of the individual and of humankind...portrayed through the solitude of love and of being in love".

In response to Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza's question, "If solitude is the theme of all your books, where should we look for the roots of this over-riding emotion? In your childhood perhaps?" García Márquez replied, "I think it's a problem everybody has. Everyone has his own way and means of expressing it. The feeling pervades the work of so many writers, although some of them may express it unconsciously."

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, '' Solitude of Latin America'', he relates this theme of solitude to the Latin American experience, "The interpretation of our reality through patterns not our own, serves only to make us ever more unknown, ever less free, ever more solitary."

Macondo

Another important theme in many of García Márquez's work is the setting of the village he calls Macondo. He uses his home town of Aracataca, Colombia as a cultural, historical and geographical reference to create this imaginary town, but the representation of the village is not limited to this specific area. García Márquez shares, "Macondo is not so much a place as a state of mind, which allows you to see what you want, and how you want to see it." Even when his stories do not take place in Macondo, there is often still a consistent lack of specificity to the location. So while they are often set with "a Caribbean coastline and an Andean hinterland... he settings areotherwise unspecified, in accordance with García Márquez's evident attempt to capture a more general regional myth rather than give a specific political analysis." This fictional town has become well known in the literary world. As Stavans notes of Macondo, "its geography and inhabitants constantly invoked by teachers, politicians, and tourist agents..." makes it "...hard to believe it is a sheer fabrication." In ''Leaf Storm'' García Márquez depicts the realities of the ''Banana Boom'' in Macondo, which include a period of great wealth during the presence of the US companies and a period of depression upon the departure of the American banana companies. ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' takes place in Macondo and tells the complete history of the fictional town from its founding to its doom. The account of Macondo in Constance Pedoto, in " The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World" has been compared to tales from Alaska which combine the real and the surreal, deriving from an upbringing which combined superstitious beliefs and a harsh environment.

In his autobiography, García Márquez explains his fascination with the word and concept Macondo. He describes a trip he made with his mother back to Aracataca as a young man:The train stopped at a station that had no town, and a short while later it passed the only banana plantation along the route that had its name written over the gate: ''Macondo''. This word had attracted my attention ever since the first trips I had made with my grandfather, but I discovered only as an adult that I liked its poetic resonance. I never heard anyone say it and did not even ask myself what it meant...I happened to read in an encyclopedia that it is a tropical tree resembling the Ceiba

''Ceiba'' is a genus of trees in the family Malvaceae, native to Tropics, tropical and Subtropics, subtropical areas of the Americas (from Mexico and the Caribbean to northern Argentina) and tropical West Africa. Some species can grow to tall ...

.

La Violencia

In several of García Márquez's works, including ''No One Writes to the Colonel'', ''In Evil Hour'', and ''Leaf Storm'', he referenced '' La Violencia'' (the violence), "a brutal civil war between conservatives and liberals that lasted into the 1960s, causing the deaths of several hundred thousand Colombians".

Legacy

García Márquez's work is an important part of the Latin American Boom of literature, often defined around his works, and those of Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes

Carlos Fuentes Macías (; ; November 11, 1928 – May 15, 2012) was a Mexican novelist and essayist. Among his works are ''The Death of Artemio Cruz'' (1962), '' Aura'' (1962), '' Terra Nostra'' (1975), '' The Old Gringo'' (1985) and '' Christop ...

, and Mario Vargas Llosa

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquess of Vargas Llosa (28 March 1936 – 13 April 2025) was a Peruvian novelist, journalist, essayist and politician. Vargas Llosa was one of the most significant Latin American novelists and essayists a ...

. His work has challenged critics of Colombian literature to step out of the conservative criticism that had been dominant before the success of ''One Hundred Years of Solitude''. In a review of literary criticism Robert Sims notes,Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center, known as the Humanities Research Center until 1983, is an archive, library, and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe ...

, a humanities research library and museum.

In 2023, García Márquez surpassed Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

as the most translated Spanish-language writer according to the World Translation Map. The ranking is based on works translated into 10 languages, including English, Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian and Swedish. García Márquez is also the most translated Spanish-language author between 2000–2021 ahead of Mario Vargas Llosa

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquess of Vargas Llosa (28 March 1936 – 13 April 2025) was a Peruvian novelist, journalist, essayist and politician. Vargas Llosa was one of the most significant Latin American novelists and essayists a ...

, Isabel Allende, Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

, Carlos Ruiz Zafon, Roberto Bolaño, Cervantes and more.

Nobel Prize

García Márquez received the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

on 10 December 1982 "for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent's life and conflicts". His acceptance speech was entitled " The Solitude of Latin America". García Márquez was the first Colombian and fourth Latin American to win a Nobel Prize for Literature. After becoming a Nobel laureate, García Márquez stated to a correspondent: "I have the impression that in giving me the prize, they have taken into account the literature of the sub-continent and have awarded me as a way of awarding all of this literature".

García Márquez in fiction

A year after his death, García Márquez appears as a notable character in Claudia Amengual's novel '' Cartagena'', set in Uruguay and Colombia.

In Giannina Braschi

Giannina Braschi (born February 5, 1953) is a Puerto Rican poet, novelist, dramatist, and scholar. Her notable works include '' Empire of Dreams'' (1988), '' Yo-Yo Boing!'' (1998), '' United States of Banana'' (2011), and '' Putinoika'' (2024). ...

's ''Empire of Dreams'', the protagonist Mariquita Samper shoots the narrator of the Latin American Boom, presumed by critics to be the figure of García Marquez; in Braschi's Spanglish

Spanglish (a blend of the words "Spanish" and "English") is any language variety (such as a contact dialect, hybrid language, pidgin, or creole language) that results from conversationally combining Spanish and English. The term is mostly u ...

novel Yo-Yo Boing! characters debate the importance of García Márquez and Isabel Allende during a heated dinner party scene.

List of works

Novels

* '' In Evil Hour'' (1962)

Novellas

* '' Leaf Storm'' (1955)

Short stories

* '' The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World'' (1968)

* '' A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings'' (1968)

* '' The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother'' (1972)

* ''The General's Departure'' (1990)

Short story collections

* ''Big Mama's Funeral'' (1962, reprinted 2005)

* ''Innocent Eréndira, and other stories'' (1978)

* ''Collected Stories'' (1984)

* '' Strange Pilgrims'' (1993)

Non-fiction

* '' The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor'' (1970)

* '' The Solitude of Latin America'' (1982)

* '' The Fragrance of Guava'' (1982, with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza)

* '' Clandestine in Chile'' (1986)

* '' Changing the History of Africa: Angola and Namibia'' (1991, with David Deutschmann)

* '' News of a Kidnapping'' (1997)

* ''A Country for Children'' (1998)

* '' Living to Tell the Tale'' (2002)

* ''The Scandal of the Century: Selected Journalistic Writings, 1950–1984'' (2019)

Films

Adaptations based on his works

* ''There Are No Thieves in This Village'' (1965, Alberto Isaac

Alberto Isaac (18 March 1923 – 9 January 1998) was a Mexican freestyle Swimming (sport), swimmer and later a film director and screenwriter. He competed in the 1948 Summer Olympics and the 1952 Summer Olympics.

In 1969, he directed the do ...

; also as actor)Netflix

Netflix is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service. The service primarily distributes original and acquired films and television shows from various genres, and it is available internationally in multiple lang ...

)

See also

* Latin American Boom

* Latin American Literature

* McOndo

* Vallenato

* Biblioteca Gabriel García Márquez, library in Barcelona, declared world best library in 2023

Notes

References

General bibliography

*

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* Hernández, Consuelo. "''El Amor en los tiempos del cólera'' es una novela popular." Diario la Prensa: New York, 4 October. 1987.

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

Further reading

*

*

External links

Gabo Fellowship in Cultural JournalismGabriel García Márquez: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Garcia Marquez, Gabriel

1927 births

2014 deaths

20th-century Colombian novelists

20th-century Colombian poets

20th-century Colombian writers

20th-century essayists

20th-century journalists

20th-century screenwriters

20th-century short story writers

21st-century Colombian novelists

21st-century Colombian poets

21st-century Colombian writers

21st-century essayists

21st-century journalists

21st-century memoirists

21st-century screenwriters

21st-century short story writers

Colombian autobiographers

Colombian essayists

Colombian expatriates in Mexico

Colombian literature

Colombian male novelists

Colombian male poets

Colombian male short story writers

Colombian Nobel laureates

Colombian non-fiction writers

Colombian male non-fiction writers

Colombian political writers

Colombian screenwriters

Colombian male screenwriters

Colombian socialists

Deaths from pneumonia in Mexico

Fabulists

Magic realism writers

Colombian memoirists

Mestizo writers

National University of Colombia alumni

Nobel laureates in Literature

People from Magdalena Department

People with Alzheimer's disease

Postmodern writers

Recipients of the Legion of Honour

Speechwriters

Surrealist writers

Urban fantasy writers

Writers about activism and social change

Writers of historical fiction set in the modern age

Gabriel García Márquez was born on 6 March 1927 in the small town of Aracataca, in the Caribbean region of Colombia, to Gabriel Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán. Soon after García Márquez was born, his father became a pharmacist and moved with his wife to the nearby large port city of

Gabriel García Márquez was born on 6 March 1927 in the small town of Aracataca, in the Caribbean region of Colombia, to Gabriel Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán. Soon after García Márquez was born, his father became a pharmacist and moved with his wife to the nearby large port city of  After writing ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' García Márquez returned to Europe, this time bringing along his family, to live in

After writing ''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' García Márquez returned to Europe, this time bringing along his family, to live in