GMOs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Economic Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops on the Agri-Food Sector; p. 42 Glossary – Term and Definitions

The European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture, "Genetic engineering: The manipulation of an organism's genetic endowment by introducing or eliminating specific genes through modern molecular biology techniques. A broad definition of genetic engineering also includes selective breeding and other means of artificial selection", Retrieved 5 November 2012 These definitions were promptly adjusted with a number of exceptions added as the result of pressure from scientific and farming communities, as well as developments in science. The EU definition later excluded traditional breeding, in vitro fertilization, induction of

Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism. This gene can be taken from a

Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism. This gene can be taken from a

Humans have domesticated plants and animals since around 12,000 BCE, using

Humans have domesticated plants and animals since around 12,000 BCE, using  In 1974, Rudolf Jaenisch created a

In 1974, Rudolf Jaenisch created a

GM crops: A bitter harvest?

/ref> when a strawberry and potato field in California were sprayed with it. The first

Other uses for genetically modified bacteria include

Other uses for genetically modified bacteria include

Plants have been engineered for scientific research, to display new flower colors, deliver vaccines, and to create enhanced crops. Many plants are

Plants have been engineered for scientific research, to display new flower colors, deliver vaccines, and to create enhanced crops. Many plants are  Some genetically modified plants are purely ornamental. They are modified for flower color, fragrance, flower shape and plant architecture. The first genetically modified ornamentals commercialized altered color.

Some genetically modified plants are purely ornamental. They are modified for flower color, fragrance, flower shape and plant architecture. The first genetically modified ornamentals commercialized altered color.

Genetically modified crops are genetically modified plants that are used in

Genetically modified crops are genetically modified plants that are used in  There are three main aims to agricultural advancement; increased production, improved conditions for agricultural workers and

There are three main aims to agricultural advancement; increased production, improved conditions for agricultural workers and

Executive Summary, Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2013

ISAAA Brief 46-2013, Retrieved 6 August 2014 Geographically though the spread has been uneven, with strong growth in the Golden rice is the most well known GM crop that is aimed at increasing nutrient value. It has been engineered with three genes that

Golden rice is the most well known GM crop that is aimed at increasing nutrient value. It has been engineered with three genes that

Link.

/ref>

The process of genetically engineering mammals is slow, tedious, and expensive. However, new technologies are making genetic modifications easier and more precise.Murray, Joo (20)

The process of genetically engineering mammals is slow, tedious, and expensive. However, new technologies are making genetic modifications easier and more precise.Murray, Joo (20)

Genetically modified animals

Canada: Brainwaving The first transgenic mammals were produced by injecting viral DNA into embryos and then implanting the embryos in females. The embryo would develop and it would be hoped that some of the genetic material would be incorporated into the reproductive cells. Then researchers would have to wait until the animal reached breeding age and then offspring would be screened for the presence of the gene in every cell. The development of the Scientists have genetically engineered several organisms, including some mammals, to include

Scientists have genetically engineered several organisms, including some mammals, to include

Systems have been developed to create transgenic organisms in a wide variety of other animals. Chickens have been genetically modified for a variety of purposes. This includes studying

Systems have been developed to create transgenic organisms in a wide variety of other animals. Chickens have been genetically modified for a variety of purposes. This includes studying  The gene responsible for

The gene responsible for

There are differences in the regulation for the release of GMOs between countries, with some of the most marked differences occurring between the US and Europe. Regulation varies in a given country depending on the intended use of the products of the genetic engineering. For example, a crop not intended for food use is generally not reviewed by authorities responsible for food safety. Some nations have banned the release of GMOs or restricted their use, and others permit them with widely differing degrees of regulation. In 2016, thirty eight countries officially ban or prohibit the cultivation of GMOs and nine (Algeria, Bhutan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Peru, Russia, Venezuela and Zimbabwe) ban their importation. Most countries that do not allow GMO cultivation do permit research using GMOs. Despite regulation, illegal releases have sometimes occurred, due to weakness of enforcement.

The European Union (EU) differentiates between approval for cultivation within the EU and approval for import and processing. While only a few GMOs have been approved for cultivation in the EU a number of GMOs have been approved for import and processing. The cultivation of GMOs has triggered a debate about the market for GMOs in Europe. Depending on the coexistence regulations, incentives for cultivation of GM crops differ. The US policy does not focus on the process as much as other countries, looks at verifiable scientific risks and uses the concept of

There are differences in the regulation for the release of GMOs between countries, with some of the most marked differences occurring between the US and Europe. Regulation varies in a given country depending on the intended use of the products of the genetic engineering. For example, a crop not intended for food use is generally not reviewed by authorities responsible for food safety. Some nations have banned the release of GMOs or restricted their use, and others permit them with widely differing degrees of regulation. In 2016, thirty eight countries officially ban or prohibit the cultivation of GMOs and nine (Algeria, Bhutan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Peru, Russia, Venezuela and Zimbabwe) ban their importation. Most countries that do not allow GMO cultivation do permit research using GMOs. Despite regulation, illegal releases have sometimes occurred, due to weakness of enforcement.

The European Union (EU) differentiates between approval for cultivation within the EU and approval for import and processing. While only a few GMOs have been approved for cultivation in the EU a number of GMOs have been approved for import and processing. The cultivation of GMOs has triggered a debate about the market for GMOs in Europe. Depending on the coexistence regulations, incentives for cultivation of GM crops differ. The US policy does not focus on the process as much as other countries, looks at verifiable scientific risks and uses the concept of

/ref> Whether gene edited organisms should be regulated the same as genetically modified organism is debated. USA regulations sees them as separate and does not regulate them under the same conditions, while in Europe a GMO is any organism created using genetic engineering techniques. One of the key issues concerning regulators is whether GM products should be labeled. The

Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors On Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods

and associate

Press release: Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers

say that absent scientific evidence of harm even voluntary labeling is

There is a

There is a

However, in the decades since, several such examples have been observed. Gene flow between GM crops and compatible plants, along with increased use of broad-spectrum

"Proposals for managing the coexistence of GM, conventional and organic crops Response to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs consultation paper"

October 2006 the rigor of the regulatory process, consolidation of control of the food supply in companies that make and sell GMOs, exaggeration of the benefits of genetic modification, or concerns over the use of herbicides with glyphosate. Other issues raised include the patenting of life and the use of

"Statement on Genetically Modified Organisms in the Environment and the Marketplace"

. October 2013Irish Doctors' Environmental Associatio

"IDEA Position on Genetically Modified Foods"

. Retrieved 25 March 2014.PR Newswir

11 November 2013

ISAAA database

GMO-Compass: Information on genetically modified organisms

{{Authority control Molecular biology 1973 introductions Articles containing video clips

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and fu ...

whose gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

tic material has been altered using genetic engineering techniques. The exact definition of a genetically modified organism and what constitutes genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including ...

varies, with the most common being an organism altered in a way that "does not occur naturally by mating and/or natural recombination". A wide variety of organisms have been genetically modified (GM), from animals to plants and microorganisms. Genes have been transferred within the same species, across species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

(creating transgenic organisms), and even across kingdoms. New genes can be introduced, or endogenous

Endogenous substances and processes are those that originate from within a living system such as an organism, tissue, or cell.

In contrast, exogenous substances and processes are those that originate from outside of an organism.

For example, ...

genes can be enhanced, altered, or knocked out

A knockout (abbreviated to KO or K.O.) is a fight-ending, winning criterion in several full-contact combat sports, such as boxing, kickboxing, muay thai, mixed martial arts, karate, some forms of taekwondo and other sports involving strikin ...

.

Creating a genetically modified organism is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism and combine it with other genetic elements, including a promoter and terminator region and often a selectable marker A selectable marker is a gene introduced into a cell, especially a bacterium or to cells in culture, that confers a trait suitable for artificial selection. They are a type of reporter gene used in laboratory microbiology, molecular biology, an ...

. A number of techniques are available for inserting the isolated gene into the host genome. Recent advancements using genome editing

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly inserts ...

techniques, notably CRISPR

CRISPR () (an acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. These sequences are derived from DNA fragments of bact ...

, have made the production of GMOs much simpler. Herbert Boyer

Herbert Wayne "Herb" Boyer (born July 10, 1936) is an American biotechnologist, researcher and entrepreneur in biotechnology. Along with Stanley N. Cohen and Paul Berg he discovered a method to coax bacteria into producing foreign proteins, the ...

and Stanley Cohen made the first genetically modified organism in 1973, a bacterium resistant to the antibiotic kanamycin. The first genetically modified animal, a mouse, was created in 1974 by Rudolf Jaenisch, and the first plant was produced in 1983. In 1994, the Flavr Savr tomato was released, the first commercialized genetically modified food

Genetically modified foods (GM foods), also known as genetically engineered foods (GE foods), or bioengineered foods are foods produced from organisms that have had changes introduced into their DNA using the methods of genetic engineering. Gene ...

. The first genetically modified animal to be commercialized was the GloFish (2003) and the first genetically modified animal to be approved for food use was the AquAdvantage salmon in 2015.

Bacteria are the easiest organisms to engineer and have been used for research, food production, industrial protein purification (including drugs), agriculture, and art. There is potential to use them for environmental purposes or as medicine. Fungi have been engineered with much the same goals. Viruses play an important role as vectors for inserting genetic information into other organisms. This use is especially relevant to human gene therapy

Gene therapy is a Medicine, medical field which focuses on the genetic modification of cells to produce a therapeutic effect or the treatment of disease by repairing or reconstructing defective genetic material. The first attempt at modifying ...

. There are proposals to remove the virulent genes from viruses to create vaccines. Plants have been engineered for scientific research, to create new colors in plants, deliver vaccines, and to create enhanced crops. Genetically modified crops

Genetically modified crops (GM crops) are plants used in agriculture, the DNA of which has been modified using genetic engineering methods. Plant genomes can be engineered by physical methods or by use of ''Agrobacterium'' for the delivery of ...

are publicly the most controversial GMOs, in spite of having the most human health and environmental benefits. The majority are engineered for herbicide tolerance or insect resistance. Golden rice has been engineered with three genes that increase its nutritional value Nutritional value or nutritive value as part of food quality is the measure of a well-balanced ratio of the essential nutrients carbohydrates, fat, protein, minerals, and vitamins in items of food or diet concerning the nutrient requirements of t ...

. Other prospects for GM crops are as bioreactor

A bioreactor refers to any manufactured device or system that supports a biologically active environment. In one case, a bioreactor is a vessel in which a chemical process is carried out which involves organisms or biochemically active substance ...

s for the production of biopharmaceutical

A biopharmaceutical, also known as a biological medical product, or biologic, is any pharmaceutical drug product manufactured in, extracted from, or semisynthesized from biological sources. Different from totally synthesized pharmaceuticals, t ...

s, biofuels, or medicines.

Animals are generally much harder to transform and the vast majority are still at the research stage. Mammals are the best model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

s for humans, making ones genetically engineered to resemble serious human diseases important to the discovery and development of treatments. Human proteins expressed in mammals are more likely to be similar to their natural counterparts than those expressed in plants or microorganisms. Livestock is modified with the intention of improving economically important traits such as growth rate, quality of meat, milk composition, disease resistance, and survival. Genetically modified fish are used for scientific research, as pets, and as a food source. Genetic engineering has been proposed as a way to control mosquitos, a vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

for many deadly diseases. Although human gene therapy is still relatively new, it has been used to treat genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosomal abnormality. Although polygenic disorders ...

s such as severe combined immunodeficiency

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), also known as Swiss-type agammaglobulinemia, is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the disturbed development of functional T cells and B cells caused by numerous genetic mutations that result in diffe ...

and Leber's congenital amaurosis.

Many objections have been raised over the development of GMOs, particularly their commercialization. Many of these involve GM crops and whether food produced from them is safe and what impact growing them will have on the environment. Other concerns are the objectivity and rigor of regulatory authorities, contamination of non-genetically modified food, control of the food supply

Food security speaks to the availability of food in a country (or geography) and the ability of individuals within that country (geography) to access, afford, and source adequate foodstuffs. According to the United Nations' Committee on World Fo ...

, patenting of life, and the use of intellectual property

Intellectual property (IP) is a category of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The best-known types are patents, co ...

rights. Although there is a scientific consensus

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

Consensus is achieved through scholarly communication at confe ...

that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food, GM food safety is a leading issue with critics. Gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

, impact on non-target organisms, and escape are the major environmental concerns. Countries have adopted regulatory measures to deal with these concerns. There are differences in the regulation for the release of GMOs between countries, with some of the most marked differences occurring between the US and Europe. Key issues concerning regulators include whether GM food should be labeled and the status of gene-edited organisms.

Definition

The definition of a genetically modified organism (GMO) is not clear and varies widely between countries, international bodies, and other communities. At its broadest, the definition of a GMO can include anything that has had its genes altered, including by nature. Taking a less broad view, it can encompass every organism that has had its genes altered by humans, which would include all crops and livestock. In 1993, the ''Encyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia ( American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articl ...

'' defined genetic engineering as "any of a wide range of techniques ... among them artificial insemination

Artificial insemination is the deliberate introduction of sperm into a female's cervix or uterine cavity for the purpose of achieving a pregnancy through in vivo fertilization by means other than sexual intercourse. It is a fertility treatment ...

, ''in vitro'' fertilization (''e.g.'', 'test-tube' babies), sperm bank

A sperm bank, semen bank, or cryobank is a facility or enterprise which purchases, stores and sells human semen. The semen is produced and sold by men who are known as sperm donors. The sperm is purchased by or for other persons for the purpose o ...

s, cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, c ...

, and gene manipulation." The European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

(EU) included a similarly broad definition in early reviews, specifically mentioning GMOs being produced by "selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant ...

and other means of artificial selection"StafEconomic Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops on the Agri-Food Sector; p. 42 Glossary – Term and Definitions

The European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture, "Genetic engineering: The manipulation of an organism's genetic endowment by introducing or eliminating specific genes through modern molecular biology techniques. A broad definition of genetic engineering also includes selective breeding and other means of artificial selection", Retrieved 5 November 2012 These definitions were promptly adjusted with a number of exceptions added as the result of pressure from scientific and farming communities, as well as developments in science. The EU definition later excluded traditional breeding, in vitro fertilization, induction of

polyploidy

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than one pair of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they ha ...

, mutation breeding Mutation breeding, sometimes referred to as "variation breeding", is the process of exposing seeds to chemicals, radiation, or enzymes in order to generate mutants with desirable traits to be bred with other cultivars. Plants created using mutagene ...

, and cell fusion techniques that do not use recombinant nucleic acids or a genetically modified organism in the process.

Another approach was the definition provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)french: link=no, Organisation des Nations unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture; it, Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite per l'Alimentazione e l'Agricoltura is an intern ...

, the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

, and the European Commission

The European Commission (EC) is the executive of the European Union (EU). It operates as a cabinet government, with 27 members of the Commission (informally known as "Commissioners") headed by a President. It includes an administrative body ...

, stating that the organisms must be altered in a way that does "not occur naturally by mating and/or natural recombination". Progress in science, such as the discovery of horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

being a relatively common natural phenomenon, further added to the confusion on what "occurs naturally", which led to further adjustments and exceptions. There are examples of crops that fit this definition, but are not normally considered GMOs. For example, the grain crop triticale

Triticale (; × ''Triticosecale'') is a hybrid of wheat (''Triticum'') and rye (''Secale'') first bred in laboratories during the late 19th century in Scotland and Germany. Commercially available triticale is almost always a second-generation ...

was fully developed in a laboratory in 1930 using various techniques to alter its genome.

Genetically engineered organism (GEO) can be considered a more precise term compared to GMO when describing organisms' genomes that have been directly manipulated with biotechnology. The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity is an international agreement on biosafety as a supplement to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) effective since 2003. The Biosafety Protocol seeks to prot ...

used the synonym ''living modified organism'' (''LMO'') in 2000 and defined it as "any living organism that possesses a novel combination of genetic material obtained through the use of modern biotechnology." Modern biotechnology is further defined as "In vitro nucleic acid techniques, including recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and direct injection of nucleic acid into cells or organelles, or fusion of cells beyond the taxonomic family."

The term GMO originally was not typically used by scientists to describe genetically engineered organisms until after usage of GMO became common in popular media. The United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

(USDA) considers GMOs to be plants or animals with heritable changes introduced by genetic engineering or traditional methods, while GEO specifically refers to organisms with genes introduced, eliminated, or rearranged using molecular biology, particularly recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be f ...

techniques, such as transgenesis

Gene delivery is the process of introducing foreign genetic material, such as DNA or RNA, into host cells. Gene delivery must reach the genome of the host cell to induce gene expression. Successful gene delivery requires the foreign gene deli ...

.

The definitions focus on the process more than the product, which means there could be GMOS and non-GMOs with very similar genotypes and phenotypes. This has led scientists to label it as a scientifically meaningless category, saying that it is impossible to group all the different types of GMOs under one common definition. It has also caused issues for organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

institutions and groups looking to ban GMOs. It also poses problems as new processes are developed. The current definitions came in before genome editing

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly inserts ...

became popular and there is some confusion as to whether they are GMOs. The EU has adjudged that they are changing their GMO definition to include "organisms obtained by mutagenesis

Mutagenesis () is a process by which the genetic information of an organism is changed by the production of a mutation. It may occur spontaneously in nature, or as a result of exposure to mutagens. It can also be achieved experimentally using lab ...

", but has excluded them from regulation based on their "long safety record" and that they have been "conventionally been used in a number of applications". In contrast the USDA has ruled that gene edited organisms are not considered GMOs.

Even greater inconsistency and confusion is associated with various "Non-GMO" or "GMO-free" labelling schemes in food marketing, where even products such as water or salt, which do not contain any organic substances and genetic material (and thus cannot be genetically modified by definition), are being labelled to create an impression of being "more healthy".

Production

Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism. This gene can be taken from a

Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism. This gene can be taken from a cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

or artificially synthesized. If the chosen gene or the donor organism's genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

has been well studied it may already be accessible from a genetic library. The gene is then combined with other genetic elements, including a promoter and terminator region and a selectable marker A selectable marker is a gene introduced into a cell, especially a bacterium or to cells in culture, that confers a trait suitable for artificial selection. They are a type of reporter gene used in laboratory microbiology, molecular biology, an ...

.

A number of techniques are available for inserting the isolated gene into the host genome. Bacteria can be induced to take up foreign DNA, usually by exposed heat shock or electroporation

Electroporation, or electropermeabilization, is a microbiology technique in which an electrical field is applied to cells in order to increase the permeability of the cell membrane, allowing chemicals, drugs, electrode arrays or DNA to be introd ...

. DNA is generally inserted into animal cells using microinjection, where it can be injected through the cell's nuclear envelope

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the nucleus, which encloses the genetic material.

The nuclear envelope consists of two lipid bilayer membr ...

directly into the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

* Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucl ...

, or through the use of viral vectors. In plants the DNA is often inserted using ''Agrobacterium''-mediated recombination, biolistics or electroporation.

As only a single cell is transformed with genetic material, the organism must be regenerated from that single cell. In plants this is accomplished through tissue culture

Tissue culture is the growth of tissues or cells in an artificial medium separate from the parent organism. This technique is also called micropropagation. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-solid, or solid growth medium, su ...

. In animals it is necessary to ensure that the inserted DNA is present in the embryonic stem cells

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst, an early-stage pre- implantation embryo. Human embryos reach the blastocyst stage 4–5 days post fertilization, at which time they consist ...

. Further testing using PCR, Southern hybridization

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detecti ...

, and DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. T ...

is conducted to confirm that an organism contains the new gene.

Traditionally the new genetic material was inserted randomly within the host genome. Gene targeting

Gene targeting (also, replacement strategy based on homologous recombination) is a genetic technique that uses homologous recombination to modify an endogenous gene. The method can be used to delete a gene, remove exons, add a gene and modify ...

techniques, which creates double-stranded breaks and takes advantage on the cells natural homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may ...

repair systems, have been developed to target insertion to exact locations. Genome editing

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly inserts ...

uses artificially engineered nuclease

A nuclease (also archaically known as nucleodepolymerase or polynucleotidase) is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds between nucleotides of nucleic acids. Nucleases variously effect single and double stranded breaks in their t ...

s that create breaks at specific points. There are four families of engineered nucleases: meganuclease Meganucleases are endodeoxyribonucleases characterized by a large recognition site (double-stranded DNA sequences of 12 to 40 base pairs); as a result this site generally occurs only once in any given genome. For example, the 18-base pair sequence ...

s, zinc finger nuclease

Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) are artificial restriction enzymes generated by fusing a zinc finger DNA-binding domain to a DNA-cleavage domain. Zinc finger domains can be engineered to target specific desired DNA sequences and this enables zin ...

s, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and the Cas9-guideRNA system (adapted from CRISPR). TALEN and CRISPR are the two most commonly used and each has its own advantages. TALENs have greater target specificity, while CRISPR is easier to design and more efficient.

History

selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant ...

or artificial selection (as contrasted with natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

). The process of selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant ...

, in which organisms with desired traits (and thus with the desired genes

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

) are used to breed the next generation and organisms lacking the trait are not bred, is a precursor to the modern concept of genetic modification. Various advancements in genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

allowed humans to directly alter the DNA and therefore genes of organisms. In 1972, Paul Berg

Paul Berg (born June 30, 1926) is an American biochemist and professor emeritus at Stanford University. He was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980, along with Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger. The award recognized their con ...

created the first recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be f ...

molecule when he combined DNA from a monkey virus with that of the lambda virus.

Herbert Boyer

Herbert Wayne "Herb" Boyer (born July 10, 1936) is an American biotechnologist, researcher and entrepreneur in biotechnology. Along with Stanley N. Cohen and Paul Berg he discovered a method to coax bacteria into producing foreign proteins, the ...

and Stanley Cohen made the first genetically modified organism in 1973. They took a gene from a bacterium that provided resistance to the antibiotic kanamycin, inserted it into a plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

and then induced other bacteria to incorporate the plasmid. The bacteria that had successfully incorporated the plasmid was then able to survive in the presence of kanamycin. Boyer and Cohen expressed other genes in bacteria. This included genes from the toad ''Xenopus laevis

The African clawed frog (''Xenopus laevis'', also known as the xenopus, African clawed toad, African claw-toed frog or the ''platanna'') is a species of African aquatic frog of the family Pipidae. Its name is derived from the three short claws o ...

'' in 1974, creating the first GMO expressing a gene from an organism of a different kingdom.

In 1974, Rudolf Jaenisch created a

In 1974, Rudolf Jaenisch created a transgenic mouse

A genetically modified mouse or genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) is a mouse (''Mus musculus'') that has had its genome altered through the use of genetic engineering techniques. Genetically modified mice are commonly used for research or a ...

by introducing foreign DNA into its embryo, making it the world's first transgenic animal. However it took another eight years before transgenic mice were developed that passed the transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change t ...

to their offspring. Genetically modified mice were created in 1984 that carried cloned oncogenes

An oncogene is a gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels.

, predisposing them to developing cancer. Mice with genes removed (termed a knockout mouse

A knockout mouse, or knock-out mouse, is a genetically modified mouse (''Mus musculus'') in which researchers have inactivated, or "knocked out", an existing gene by replacing it or disrupting it with an artificial piece of DNA. They are importan ...

) were created in 1989. The first transgenic livestock were produced in 1985 and the first animal to synthesize transgenic proteins in their milk were mice in 1987. The mice were engineered to produce human tissue plasminogen activator

Tissue plasminogen activator (abbreviated tPA or PLAT) is a protein involved in the breakdown of blood clots. It is a serine protease () found on endothelial cells, the cells that line the blood vessels. As an enzyme, it catalyzes the conversion ...

, a protein involved in breaking down blood clots

A thrombus (plural thrombi), colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of cr ...

.

In 1983, the first genetically engineered plant was developed by Michael W. Bevan

Michael Webster Bevan (born 5 June 1952) is a professor at the John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK.

Education

Bevan was educated at the University of Auckland where he was awarded a Bachelor of Science in 1973 and a Master of Science in 1974. He wen ...

, Richard B. Flavell and Mary-Dell Chilton. They infected tobacco with ''Agrobacterium

''Agrobacterium'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria established by H. J. Conn that uses horizontal gene transfer to cause tumors in plants. ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' is the most commonly studied species in this genus. ''Agrobacterium ...

'' transformed with an antibiotic resistance gene and through tissue culture

Tissue culture is the growth of tissues or cells in an artificial medium separate from the parent organism. This technique is also called micropropagation. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-solid, or solid growth medium, su ...

techniques were able to grow a new plant containing the resistance gene. The gene gun was invented in 1987, allowing transformation of plants not susceptible to ''Agrobacterium'' infection. In 2000, Vitamin A

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin and an essential nutrient for humans. It is a group of organic compounds that includes retinol, retinal (also known as retinaldehyde), retinoic acid, and several provitamin A carotenoids (most notably ...

-enriched golden rice was the first plant developed with increased nutrient value.

In 1976, Genentech

Genentech, Inc., is an American biotechnology corporation headquartered in South San Francisco, California. It became an independent subsidiary of Roche in 2009. Genentech Research and Early Development operates as an independent center within ...

, the first genetic engineering company was founded by Herbert Boyer and Robert Swanson; a year later, the company produced a human protein (somatostatin

Somatostatin, also known as growth hormone-inhibiting hormone (GHIH) or by several other names, is a peptide hormone that regulates the endocrine system and affects neurotransmission and cell proliferation via interaction with G protein-cou ...

) in '' E. coli''. Genentech announced the production of genetically engineered human insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism ...

in 1978. The insulin produced by bacteria, branded Humulin, was approved for release by the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

in 1982. In 1988, the first human antibodies were produced in plants. In 1987, a strain of ''Pseudomonas syringae

''Pseudomonas syringae'' is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium with polar flagella. As a plant pathogen, it can infect a wide range of species, and exists as over 50 different pathovars, all of which are available to researchers from inte ...

'' became the first genetically modified organism to be released into the environmentBBC News 14 June 200GM crops: A bitter harvest?

/ref> when a strawberry and potato field in California were sprayed with it. The first

genetically modified crop

Genetically modified crops (GM crops) are plants used in agriculture, the DNA of which has been modified using genetic engineering methods. Plant genomes can be engineered by physical methods or by use of ''Agrobacterium'' for the delivery of s ...

, an antibiotic-resistant tobacco plant, was produced in 1982. China was the first country to commercialize transgenic plants, introducing a virus-resistant tobacco in 1992. In 1994, Calgene

The Monsanto Company () was an American agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology corporation founded in 1901 and headquartered in Creve Coeur, Missouri. Monsanto's best known product is Roundup, a glyphosate-based herbicide, developed in the ...

attained approval to commercially release the Flavr Savr tomato, the first genetically modified food

Genetically modified foods (GM foods), also known as genetically engineered foods (GE foods), or bioengineered foods are foods produced from organisms that have had changes introduced into their DNA using the methods of genetic engineering. Gene ...

. Also in 1994, the European Union approved tobacco engineered to be resistant to the herbicide bromoxynil, making it the first genetically engineered crop commercialized in Europe. An insect resistant Potato was approved for release in the US in 1995, and by 1996 approval had been granted to commercially grow 8 transgenic crops and one flower crop (carnation) in 6 countries plus the EU.

In 2010, scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute announced that they had created the first synthetic bacterial genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

. They named it Synthia and it was the world's first synthetic life

Synthetic biology (SynBio) is a multidisciplinary area of research that seeks to create new biological parts, devices, and systems, or to redesign systems that are already found in nature.

It is a branch of science that encompasses a broad ran ...

form.

The first genetically modified animal to be commercialized was the GloFish, a Zebra fish with a fluorescent gene added that allows it to glow in the dark under ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiatio ...

. It was released to the US market in 2003. In 2015, AquAdvantage salmon became the first genetically modified animal to be approved for food use. Approval is for fish raised in Panama and sold in the US. The salmon were transformed with a growth hormone

Growth hormone (GH) or somatotropin, also known as human growth hormone (hGH or HGH) in its human form, is a peptide hormone that stimulates growth, cell reproduction, and cell regeneration in humans and other animals. It is thus important in ...

-regulating gene from a Pacific Chinook salmon and a promoter from an ocean pout enabling it to grow year-round instead of only during spring and summer.

Bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

were the first organisms to be genetically modified in the laboratory, due to the relative ease of modifying their chromosomes. This ease made them important tools for the creation of other GMOs. Genes and other genetic information from a wide range of organisms can be added to a plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

and inserted into bacteria for storage and modification. Bacteria are cheap, easy to grow, clonal, multiply quickly and can be stored at −80 °C almost indefinitely. Once a gene is isolated it can be stored inside the bacteria, providing an unlimited supply for research. A large number of custom plasmids make manipulating DNA extracted from bacteria relatively easy.

Their ease of use has made them great tools for scientists looking to study gene function and evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

. The simplest model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

s come from bacteria, with most of our early understanding of molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and phys ...

coming from studying ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Esc ...

''. Scientists can easily manipulate and combine genes within the bacteria to create novel or disrupted proteins and observe the effect this has on various molecular systems. Researchers have combined the genes from bacteria and archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaeba ...

, leading to insights on how these two diverged in the past. In the field of synthetic biology

Synthetic biology (SynBio) is a multidisciplinary area of research that seeks to create new biological parts, devices, and systems, or to redesign systems that are already found in nature.

It is a branch of science that encompasses a broad ran ...

, they have been used to test various synthetic approaches, from synthesising genomes to creating novel nucleotides

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules with ...

.

Bacteria have been used in the production of food for a long time, and specific strains have been developed and selected for that work on an industrial scale. They can be used to produce enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s, amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s, flavoring

A flavoring (or flavouring), also known as flavor (or flavour) or flavorant, is a food additive used to improve the taste or smell of food. It changes the perceptual impression of food as determined primarily by the chemoreceptors of the g ...

s, and other compounds used in food production. With the advent of genetic engineering, new genetic changes can easily be introduced into these bacteria. Most food-producing bacteria are lactic acid bacteria

Lactobacillales are an order of gram-positive, low-GC, acid-tolerant, generally nonsporulating, nonrespiring, either rod-shaped ( bacilli) or spherical ( cocci) bacteria that share common metabolic and physiological characteristics. These bact ...

, and this is where the majority of research into genetically engineering food-producing bacteria has gone. The bacteria can be modified to operate more efficiently, reduce toxic byproduct production, increase output, create improved compounds, and remove unnecessary pathways. Food products from genetically modified bacteria include alpha-amylase

α-Amylase is an enzyme (EC 3.2.1.1; systematic name 4-α-D-glucan glucanohydrolase) that hydrolyses α bonds of large, α-linked polysaccharides, such as starch and glycogen, yielding shorter chains thereof, dextrins, and maltose:

:Endohyd ...

, which converts starch to simple sugars, chymosin

Chymosin or rennin is a protease found in rennet. It is an aspartic endopeptidase belonging to MEROPS A1 family. It is produced by newborn ruminant animals in the lining of the abomasum to curdle the milk they ingest, allowing a longer reside ...

, which clots milk protein for cheese making, and pectinesterase

Pectinesterase (EC 3.1.1.11; systematic name pectin pectylhydrolase) is a ubiquitous cell-wall-associated enzyme that presents several isoforms that facilitate plant cell wall modification and subsequent breakdown. It catalyzes the following reac ...

, which improves fruit juice clarity. The majority are produced in the US and even though regulations are in place to allow production in Europe, as of 2015 no food products derived from bacteria are currently available there.

Genetically modified bacteria are used to produce large amounts of proteins for industrial use. Generally the bacteria are grown to a large volume before the gene encoding the protein is activated. The bacteria are then harvested and the desired protein purified from them. The high cost of extraction and purification has meant that only high value products have been produced at an industrial scale. The majority of these products are human proteins for use in medicine. Many of these proteins are impossible or difficult to obtain via natural methods and they are less likely to be contaminated with pathogens, making them safer. The first medicinal use of GM bacteria was to produce the protein insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism ...

to treat diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

. Other medicines produced include clotting factors to treat haemophilia

Haemophilia, or hemophilia (), is a mostly inherited genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, a process needed to stop bleeding. This results in people bleeding for a longer time after an injury, easy bruisin ...

, human growth hormone

Growth hormone (GH) or somatotropin, also known as human growth hormone (hGH or HGH) in its human form, is a peptide hormone that stimulates growth, cell reproduction, and cell regeneration in humans and other animals. It is thus important in ...

to treat various forms of dwarfism

Dwarfism is a condition wherein an organism is exceptionally small, and mostly occurs in the animal kingdom. In humans, it is sometimes defined as an adult height of less than , regardless of sex; the average adult height among people with dw ...

, interferon

Interferons (IFNs, ) are a group of signaling proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten th ...

to treat some cancers, erythropoietin

Erythropoietin (; EPO), also known as erythropoetin, haematopoietin, or haemopoietin, is a glycoprotein cytokine secreted mainly by the kidneys in response to cellular hypoxia; it stimulates red blood cell production ( erythropoiesis) in th ...

for anemic patients, and tissue plasminogen activator

Tissue plasminogen activator (abbreviated tPA or PLAT) is a protein involved in the breakdown of blood clots. It is a serine protease () found on endothelial cells, the cells that line the blood vessels. As an enzyme, it catalyzes the conversion ...

which dissolves blood clots. Outside of medicine they have been used to produce biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels, such as oil. According to the United States Energy Information Administration ...

s. There is interest in developing an extracellular expression system within the bacteria to reduce costs and make the production of more products economical.

With a greater understanding of the role that the microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably wel ...

plays in human health, there is a potential to treat diseases by genetically altering the bacteria to, themselves, be therapeutic agents. Ideas include altering gut bacteria so they destroy harmful bacteria, or using bacteria to replace or increase deficient enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. ...

or proteins. One research focus is to modify ''Lactobacillus

''Lactobacillus'' is a genus of Gram-positive, aerotolerant anaerobes or microaerophilic, rod-shaped, non-spore-forming bacteria. Until 2020, the genus ''Lactobacillus'' comprised over 260 phylogenetically, ecologically, and metabolically div ...

'', bacteria that naturally provide some protection against HIV, with genes that will further enhance this protection. If the bacteria do not form colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

inside the patient, the person must repeatedly ingest the modified bacteria in order to get the required doses. Enabling the bacteria to form a colony could provide a more long-term solution, but could also raise safety concerns as interactions between bacteria and the human body are less well understood than with traditional drugs. There are concerns that horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

to other bacteria could have unknown effects. As of 2018 there are clinical trials underway testing the efficacy

Efficacy is the ability to perform a task to a satisfactory or expected degree. The word comes from the same roots as ''effectiveness'', and it has often been used synonymously, although in pharmacology a distinction is now often made between ...

and safety of these treatments.

For over a century bacteria have been used in agriculture. Crops have been inoculated with Rhizobia

Rhizobia are diazotrophic bacteria that fix nitrogen after becoming established inside the root nodules of legumes (Fabaceae). To express genes for nitrogen fixation, rhizobia require a plant host; they cannot independently fix nitrogen. In g ...

(and more recently '' Azospirillum'') to increase their production or to allow them to be grown outside their original habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

. Application of ''Bacillus thuringiensis

''Bacillus thuringiensis'' (or Bt) is a gram-positive, soil-dwelling bacterium, the most commonly used biological pesticide worldwide. ''B. thuringiensis'' also occurs naturally in the gut of caterpillars of various types of moths and butterf ...

'' (Bt) and other bacteria can help protect crops from insect infestation and plant diseases. With advances in genetic engineering, these bacteria have been manipulated for increased efficiency and expanded host range. Markers have also been added to aid in tracing the spread of the bacteria. The bacteria that naturally colonize certain crops have also been modified, in some cases to express the Bt genes responsible for pest resistance. ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative, Gammaproteobacteria, belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae and containing 191 described species. The members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able t ...

'' strains of bacteria cause frost damage by nucleating

In thermodynamics, nucleation is the first step in the formation of either a new thermodynamic phase or structure via self-assembly or self-organization within a substance or mixture. Nucleation is typically defined to be the process that deter ...

water into ice crystals

Ice crystals are solid ice exhibiting atomic ordering on various length scales and include hexagonal columns, hexagonal plates, dendritic crystals, and diamond dust.

Formation

The hugely symmetric shapes are due to depositional growth, n ...

around themselves. This led to the development of ice-minus bacteria, which have the ice-forming genes removed. When applied to crops they can compete with the non-modified bacteria and confer some frost resistance.

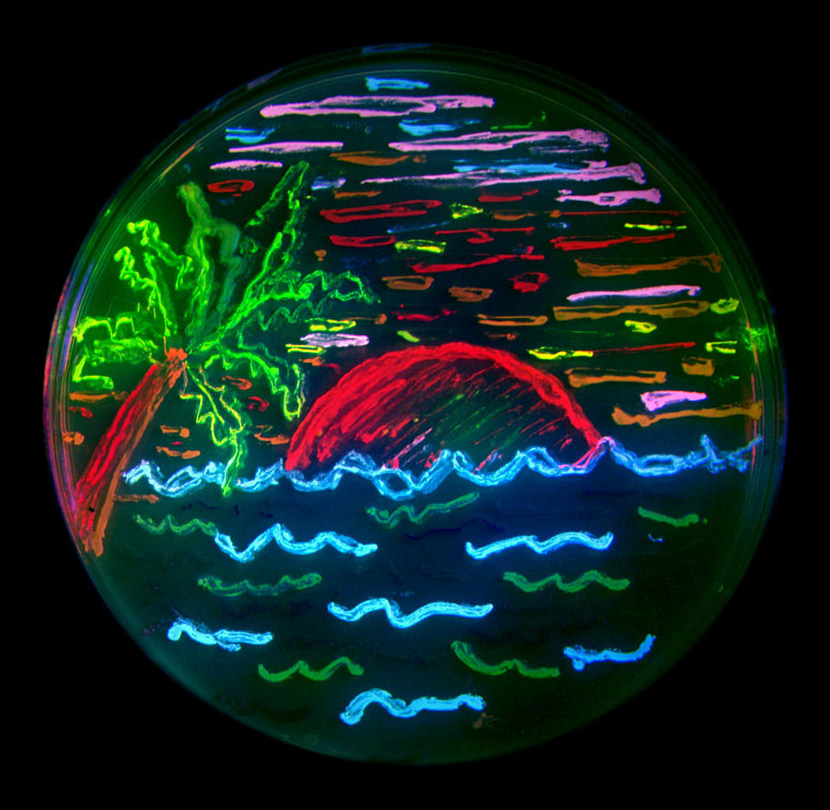

Other uses for genetically modified bacteria include

Other uses for genetically modified bacteria include bioremediation

Bioremediation broadly refers to any process wherein a biological system (typically bacteria, microalgae, fungi, and plants), living or dead, is employed for removing environmental pollutants from air, water, soil, flue gasses, industrial effluent ...

, where the bacteria are used to convert pollutants into a less toxic form. Genetic engineering can increase the levels of the enzymes used to degrade a toxin or to make the bacteria more stable under environmental conditions. Bioart

BioArt is an art practice where artists work with biology, live tissues, bacteria, living organisms, and life processes. Using scientific processes and practices such as biology and life science practices, microscopy, and biotechnology (including ...

has also been created using genetically modified bacteria. In the 1980s artist Jon Davis and geneticist Dana Boyd converted the Germanic symbol for femininity (ᛉ) into binary code and then into a DNA sequence, which was then expressed in ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Esc ...

''. This was taken a step further in 2012, when a whole book was encoded onto DNA. Paintings have also been produced using bacteria transformed with fluorescent proteins.

Viruses

Viruses are often modified so they can be used as vectors for inserting genetic information into other organisms. This process is called transduction and if successful the recipient of the introduced DNA becomes a GMO. Different viruses have different efficiencies and capabilities. Researchers can use this to control for various factors; including the target location, insert size, and duration of gene expression. Any dangerous sequences inherent in the virus must be removed, while those that allow the gene to be delivered effectively are retained. While viral vectors can be used to insert DNA into almost any organism it is especially relevant for its potential in treating human disease. Although primarily still at trial stages, there has been some successes usinggene therapy

Gene therapy is a Medicine, medical field which focuses on the genetic modification of cells to produce a therapeutic effect or the treatment of disease by repairing or reconstructing defective genetic material. The first attempt at modifying ...

to replace defective genes. This is most evident in curing patients with severe combined immunodeficiency

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), also known as Swiss-type agammaglobulinemia, is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the disturbed development of functional T cells and B cells caused by numerous genetic mutations that result in diffe ...

rising from adenosine deaminase deficiency

Adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA deficiency) is a metabolic disorder that causes immunodeficiency. It is caused by mutations in the ADA gene. It accounts for about 10–15% of all cases of autosomal recessive forms of severe combined immuno ...

(ADA-SCID), although the development of leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia and pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and result in high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or ...

in some ADA-SCID patients along with the death of Jesse Gelsinger in a 1999 trial set back the development of this approach for many years. In 2009, another breakthrough was achieved when an eight-year-old boy with Leber's congenital amaurosis regained normal eyesight and in 2016 GlaxoSmithKline

GSK plc, formerly GlaxoSmithKline plc, is a British multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company with global headquarters in London, England. Established in 2000 by a merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham. GSK is the tent ...

gained approval to commercialize a gene therapy treatment for ADA-SCID. As of 2018, there are a substantial number of clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, diet ...

s underway, including treatments for hemophilia

Haemophilia, or hemophilia (), is a mostly inherited genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, a process needed to stop bleeding. This results in people bleeding for a longer time after an injury, easy bruising ...

, glioblastoma

Glioblastoma, previously known as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is one of the most aggressive types of cancer that begin within the brain. Initially, signs and symptoms of glioblastoma are nonspecific. They may include headaches, personality ...

, chronic granulomatous disease

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), also known as Bridges–Good syndrome, chronic granulomatous disorder, and Quie syndrome, is a diverse group of hereditary diseases in which certain cells of the immune system have difficulty forming the reacti ...

, cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare genetic disorder that affects mostly the lungs, but also the pancreas, liver, kidneys, and intestine. Long-term issues include difficulty breathing and coughing up mucus as a result of frequent lung infections. Ot ...

and various cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

s.

The most common virus used for gene delivery comes from adenoviruses

Adenoviruses (members of the family ''Adenoviridae'') are medium-sized (90–100 nm), nonenveloped (without an outer lipid bilayer) viruses with an icosahedral nucleocapsid containing a double-stranded DNA genome. Their name derives from the ...

as they can carry up to 7.5 kb of foreign DNA and infect a relatively broad range of host cells, although they have been known to elicit immune responses in the host and only provide short term expression. Other common vectors are adeno-associated virus

Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) are small viruses that infect humans and some other primate species. They belong to the genus ''Dependoparvovirus'', which in turn belongs to the family '' Parvoviridae''. They are small (approximately 26 nm i ...

es, which have lower toxicity and longer-term expression, but can only carry about 4kb of DNA. Herpes simplex virus

Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), also known by their taxonomical names '' Human alphaherpesvirus 1'' and ''Human alphaherpesvirus 2'', are two members of the human ''Herpesviridae'' family, a set of viruses that produce viral in ...

es make promising vectors, having a carrying capacity of over 30kb and providing long term expression, although they are less efficient at gene delivery than other vectors. The best vectors for long term integration of the gene into the host genome are retrovirus

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. Once inside the host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptas ...

es, but their propensity for random integration is problematic. Lentivirus

''Lentivirus'' is a genus of retroviruses that cause chronic and deadly diseases characterized by long incubation periods, in humans and other mammalian species. The genus includes the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS. L ...

es are a part of the same family as retroviruses with the advantage of infecting both dividing and non-dividing cells, whereas retroviruses only target dividing cells. Other viruses that have been used as vectors include alphaviruses, flaviviruses, measles virus

''Measles morbillivirus'' (MeV), also called measles virus (MV), is a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped, non-segmented RNA virus of the genus '' Morbillivirus'' within the family '' Paramyxoviridae''. It is the cause of measles. Human ...

es, rhabdoviruses, Newcastle disease virus Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

, poxviruses, and picornavirus

Picornaviruses are a group of related nonenveloped RNA viruses which infect vertebrates including fish, mammals, and birds. They are viruses that represent a large family of small, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses with a 30 nm ...

es.

Most vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified.

s consist of viruses that have been attenuated, disabled, weakened or killed in some way so that their virulent properties are no longer effective. Genetic engineering could theoretically be used to create viruses with the virulent genes removed. This does not affect the viruses infectivity, invokes a natural immune response and there is no chance that they will regain their virulence function, which can occur with some other vaccines. As such they are generally considered safer and more efficient than conventional vaccines, although concerns remain over non-target infection, potential side effects and horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

to other viruses. Another potential approach is to use vectors to create novel vaccines for diseases that have no vaccines available or the vaccines that do not work effectively, such as AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ma ...

, malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

, and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. The most effective vaccine against Tuberculosis, the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, only provides partial protection. A modified vaccine expressing ''a M tuberculosis'' antigen is able to enhance BCG protection. It has been shown to be safe to use at phase II trials

The phases of clinical research are the stages in which scientists conduct experiments with a health intervention to obtain sufficient evidence for a process considered effective as a medical treatment. For drug development, the clinical phase ...

, although not as effective as initially hoped. Other vector-based vaccines have already been approved and many more are being developed.

Another potential use of genetically modified viruses is to alter them so they can directly treat diseases. This can be through expression of protective proteins or by directly targeting infected cells. In 2004, researchers reported that a genetically modified virus that exploits the selfish behaviour of cancer cells might offer an alternative way of killing tumours. Since then, several researchers have developed genetically modified oncolytic virus

An oncolytic virus is a virus that preferentially infects and kills cancer cells. As the infected cancer cells are destroyed by oncolysis, they release new infectious virus particles or virions to help destroy the remaining tumour. Oncolytic viru ...

es that show promise as treatments for various types of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

. In 2017, researchers genetically modified a virus to express spinach defensin

Defensins are small cysteine-rich cationic proteins across cellular life, including vertebrate and invertebrate animals, plants, and fungi. They are host defense peptides, with members displaying either direct antimicrobial activity, immune ...

proteins. The virus was injected into orange trees to combat citrus greening disease

Citrus greening disease (; or HLB) is a disease of citrus caused by a vector-transmitted pathogen. The causative agents are motile bacteria, '' Liberibacter'' spp. The disease is vectored and transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllid, '' Diaphori ...

that had reduced orange production by 70% since 2005.

Natural viral diseases, such as myxomatosis

Myxomatosis is a disease caused by ''Myxoma virus'', a poxvirus in the genus '' Leporipoxvirus''. The natural hosts are tapeti (''Sylvilagus brasiliensis'') in South and Central America, and brush rabbits (''Sylvilagus bachmani'') in North ...