Freedom Summer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the

Mississippi began to make some racial progress but white supremacy was resilient, especially in rural areas. In 1965 Congress passed the federal

Mississippi began to make some racial progress but white supremacy was resilient, especially in rural areas. In 1965 Congress passed the federal

''The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell it Like it is'

Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2011. . * *

SNCC Digital Gateway: Freedom Summer

Digital documentary website created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, telling the story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee & grassroots organizing from the inside-out

*

Freedom Summer Digital Collection

- Miami University of Ohio

Freedom Summer National Conference - 2009

- Miami University of Ohio

Freedom Summer 50th

Miami University of Ohio, 2014

Mississippi Burning (LBJ tapes and documents)

- University of Virginia

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

Freedom On My Mind

a documentary distributed by

"We had Sneakers, They Had Guns,"

Webcast and event flier essay from the

Mississippi & Freedom Summer

- The Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s

- University of Southern Mississippi

SNCC History and Geography

from the Mapping American Social Movements project at the University of Washington

Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive (USM)Oh Freedom Over Me

- American RadioWorks

Mississippi Digital Library

Original photographs, documents oral history, letters from the Mississippi freedom movement *

The 1964 MS Freedom School Curriculum

~ Education and Democracy

Freedom Summer

Civil Rights Digital Library {{Portal bar, Freedom of speech, Journalism, Language, Law, Society, United States 1964 in Mississippi 1964 in the United States 1964 protests African-American history of Mississippi Civil rights movement History of African-American civil rights History of voting rights in the United States Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

launched in June 1964 to attempt to register

Register or registration may refer to:

Arts entertainment, and media Music

* Register (music), the relative "height" or range of a note, melody, part, instrument, etc.

* ''Register'', a 2017 album by Travis Miller

* Registration (organ), th ...

as many African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

voters as possible in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. Blacks had been restricted from voting since the turn of the century due to barriers to voter registration and other laws. The project also set up dozens of Freedom Schools, Freedom Houses, and community centers in small towns throughout Mississippi to aid the local Black population.

The project was organized by the Council of Federated Organizations

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) was a coalition of the major Civil Rights Movement organizations operating in Mississippi. COFO was formed in 1961 to coordinate and unite voter registration and other civil rights activities in the sta ...

(COFO), a coalition of the Mississippi branches of the four major civil rights organizations (SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

, CORE

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber

* Core, the centra ...

, NAACP, and SCLC). Most of the impetus, leadership, and financing for the Summer Project came from SNCC. Bob Moses Robert Moses (1888–1981) was an American city planner.

Robert Moses may also refer to:

* Bob Moses (activist) (1935–2021), American educator and civil rights activist

* Bob Moses, American football player in the 1962 Cotton Bowl Classic

* Bob M ...

, SNCC field secretary and co-director of COFO, directed the summer project.

Freedom Vote

Freedom Summer was built on the years of earlier work by thousands of African Americans, connected through their churches, who lived in Mississippi. In 1963, SNCC organized a mock " Freedom Vote" designed to demonstrate the will of Black Mississippians to vote, if not impeded by terror and intimidation. The Mississippi voting registration procedure at the time required Blacks to fill out a 21-question registration form and to answer, to the satisfaction of the white registrators, a question on the interpretation of any one of 285 sections of the state constitution. The registrars ruled subjectively on the applicant's qualifications, and decided against most blacks, not allowing them to register. In 1963, volunteers set up polling places in Black churches and business establishments across Mississippi. After registering on a simple registration form, voters would select candidates to run in the following year's election. Candidates included Rev.Ed King

Edward Calhoun King (September 14, 1949 – August 22, 2018) was an American musician. He was a guitarist for the psychedelic rock band Strawberry Alarm Clock and guitarist and bassist for the Southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd from 1972 to 1975 ...

of Tougaloo College

Tougaloo College is a private historically black college in the Tougaloo area of Jackson, Mississippi. It is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). It was originally established in 1869 by New Yor ...

and Aaron Henry, from Clarksdale, Mississippi. Local civil rights workers and volunteers, along with students from northern and western universities, organized and implemented the mock election, in which tens of thousands voted.

Planning begins February 1964

By 1964, students and others had begun the process of integrating public accommodations, registering adults to vote, and above all strengthening a network of local leadership. Building on the efforts of 1963 (including the Freedom Vote and registration efforts in Greenwood), Moses prevailed over doubts among SNCC and COFO workers, and planning for Freedom Summer began in February 1964. Speakers recruited for workers on college campuses across the country, drawing standing ovations for their dedication in braving the routine violence perpetrated by police, sheriffs, and others in Mississippi. SNCC recruiters interviewed dozens of potential volunteers, weeding out those with a " John Brown complex" and informing others that their job that summer would not be to "save the Mississippi Negro" but to work with local leadership to develop the grassroots movement. More than 1,000 out-of-state volunteers participated in Freedom Summer alongside thousands of black Mississippians. Volunteers were the brightest of their generation, who came from the best universities from the biggest states, mostly from cities in theNorth

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

(e.g., Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

, Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, etc.) and West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

(e.g., Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, etc.), usually were rich, 90 percent were white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

. Though SNCC's committee agreed to recruit only one hundred white students for the project in December 1963, white civil rights leaders such as Allard Lowenstein

Allard Kenneth Lowenstein (January 16, 1929 – March 14, 1980)Lowenstein's gravestone, Arlington National Cemeteryphoto onlineon the cemetery's official website. Accessed online 28 October 2006.Western College for Women

Western College for Women, known at other times as Western Female Seminary, The Western and simply Western College, was a women's and later coed liberal arts college in Oxford, Ohio, between 1855 and 1974. Initially a seminary, it was the host of ...

in Oxford, Ohio

Oxford is a city in Butler County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,035 at the 2020 census. A college town, Oxford was founded as a home for Miami University and lies in the southwestern portion of the state approximately northwest ...

(now part of Miami University

Miami University (informally Miami of Ohio or simply Miami) is a public research university in Oxford, Ohio. The university was founded in 1809, making it the second-oldest university in Ohio (behind Ohio University, founded in 1804) and the ...

), from June 14 to June 27, after Berea College

Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College was the first college in the Southern United States to be coeducational and racially integrated. Berea College charges no tuition; every a ...

backed out of hosting the sessions due to alumni pressure against it.

Organizers focused on Mississippi because it had the lowest percentage of any state in the country of African Americans registered to vote, and they constituted more than one-third of the population. In 1962 only 6.7% of eligible black voters were registered.

Southern states had effectively disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

most African Americans and many poor whites in the period from 1890 to 1910 by passing state constitutions, amendments and other laws that imposed burdens on voter registration: charging poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

, requiring literacy tests administered subjectively by white registrars, making residency requirements more difficult, as well as elaborate record keeping to document required items. They maintained this exclusion of blacks from politics well into the 1960s, which extended to excluding them from juries and imposing Jim Crow segregation laws for public facilities.

Most of these methods survived US Supreme Court challenges and, if overruled, states had quickly developed new ways to exclude blacks, such as use of grandfather clauses and white primaries

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South ...

. In some cases, would-be voters were harassed economically, as well as by physical assault. Lynchings had been high at the turn of the century and continued for years.

During the ten weeks of Freedom Summer, a number of other organizations provided support for the COFO Summer Project. More than 100 volunteer doctors, nurses, psychologists, medical students and other medical professionals from the Medical Committee for Human Rights

The Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) was a group of American health care professionals that initially organized in June 1964 to provide medical care for civil rights workers, community activists, and summer volunteers working in Mississ ...

(MCHR) provided emergency care for volunteers and local activists, taught health education classes, and advocated improvements in Mississippi's segregated health system.

Volunteer lawyers from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Inc ("Ink Fund"), National Lawyers Guild

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG) is a progressive public interest association of lawyers, law students, paralegals, jailhouse lawyers, law collective members, and other activist legal workers, in the United States. The group was founded in 19 ...

, Lawyer's Constitutional Defense Committee (LCDC) an arm of the ACLU, and the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, or simply the Lawyers' Committee, is a civil rights organization founded in 1963 at the request of President John F. Kennedy. At the time, Alabama Governor George Wallace had vowed to resist cou ...

(LCCR) provided free legal services — handling arrests, freedom of speech, voter registration and other matters.

The Commission on Religion and Race (CORR), an endeavor of the National Council of Churches

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, usually identified as the National Council of Churches (NCC), is the largest ecumenical body in the United States. NCC is an ecumenical partnership of 38 Christian faith groups in the Un ...

(NCC), brought Christian and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish clergy and divinity students to Mississippi to support the work of the Summer Project. In addition to offering traditional religious support to volunteers and activists, the ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

and rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s engaged in voting rights protests at courthouses, recruited voter applicants and accompanied them to register, taught in Freedom Schools, and performed office and other support functions.

Violence

Many of Mississippi's white residents deeply resented the outsiders and any attempt to change the residents' society. Locals routinely harassed volunteers. The volunteers' presence in local black communities drewdrive-by shooting

A drive-by shooting is a type of assault that usually involves the perpetrator(s) firing a weapon from within a motor vehicle and then fleeing. Drive-by shootings allow the perpetrator(s) to quickly strike their target and flee the scene before ...

s, Molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with fla ...

s thrown at host homes, and constant harassment. State and local governments, the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (which was tax-supported and spied on citizens), police, White Citizens' Council

The Citizens' Councils (commonly referred to as the White Citizens' Councils) were an associated network of white supremacist, segregationist organizations in the United States, concentrated in the South and created as part of a white backlash a ...

, and Ku Klux Klan used arrests, arson, beatings, evictions, firing, murder, spying, and other forms of intimidation and harassment to oppose the project and prevent blacks from registering to vote or achieve social equality.

Over the course of the ten-week project:

*1,062 people were arrested (out-of-state volunteers and locals)

*80 Freedom Summer workers were beaten

*37 churches were bombed or burned

*30 Black homes or businesses were bombed or burned

*4 civil rights workers were killed (one in a head-on collision)

*4 people were critically wounded

*At least 3 Mississippi blacks were murdered because of their support for the Civil Rights Movement

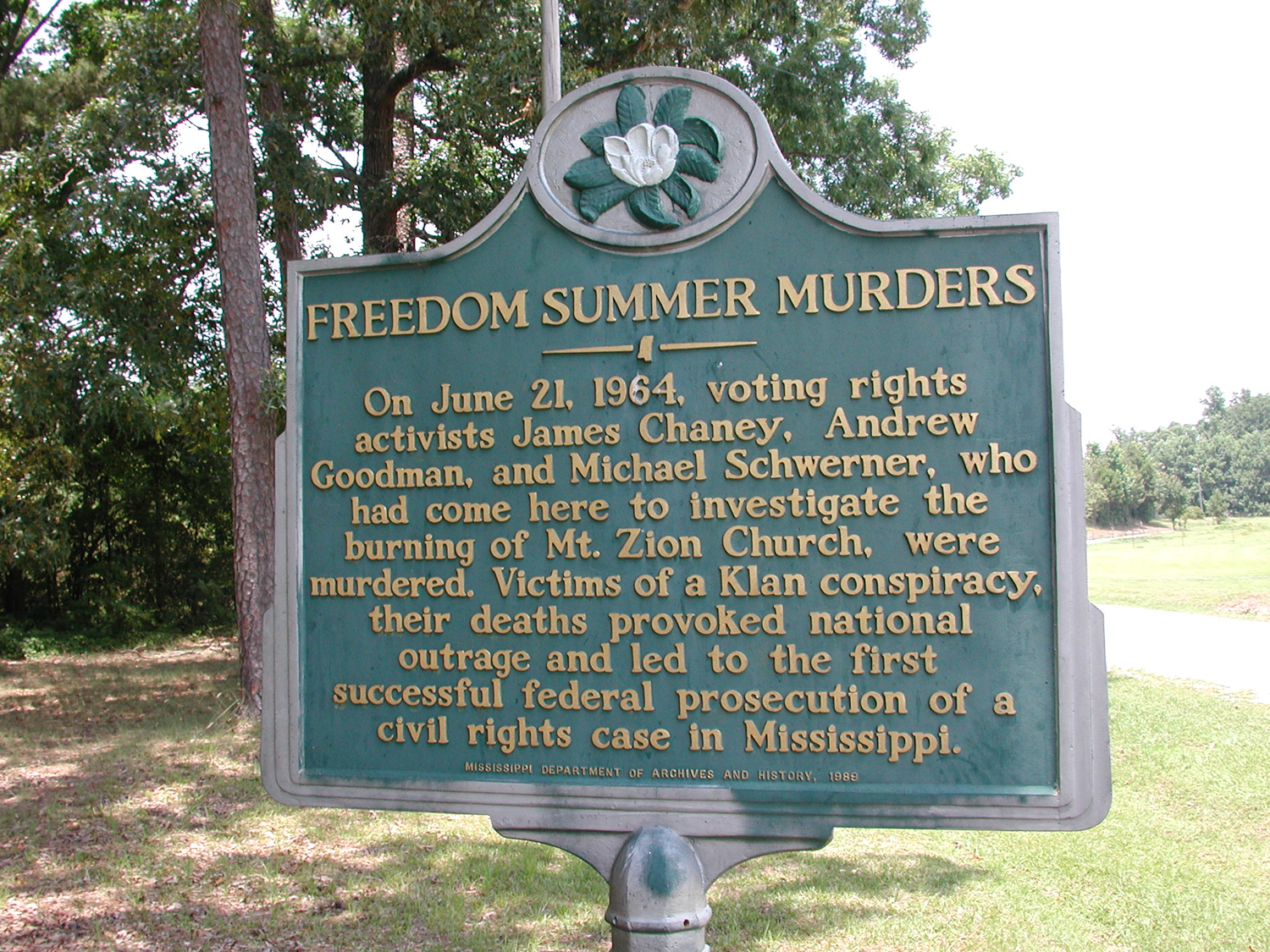

Volunteers were attacked almost as soon as the campaign started. On June 21, 1964, James Chaney

James Earl Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964) was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The others were Andrew Goodman an ...

(a black Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

ORE

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 Apr ...

activist from Mississippi), Andrew Goodman (a summer volunteer), and Michael Schwerner (a CORE organizer) - both Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

- were arrested by Cecil Price

Cecil Ray Price (April 15, 1938 – May 6, 2001) was accused of the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 1964. At the time of the murders, he was 26 years old and a deputy sheriff in Neshoba County, Mississippi. He was a member of the Wh ...

, a Neshoba County deputy sheriff and KKK member. The three were held in jail until after nightfall, then released. They drove away into an ambush on the road by Klansmen, who abducted and killed them. Goodman and Schwerner were shot at point-blank range. Chaney was chased, beaten mercilessly, and shot three times. After weeks of searching in which federal law enforcement participated, on August 4, 1964, their bodies were found to have been buried in an earthen dam. The men's disappearance the night of their release from jail was reported on TV and on newspaper front pages, shocking the nation. It drew massive media attention to Freedom Summer and to Mississippi's "closed society."

When the men went missing, SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

and COFO

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) was a coalition of the major Civil Rights Movement organizations operating in Mississippi. COFO was formed in 1961 to coordinate and unite voter registration and other civil rights activities in the sta ...

workers began phoning the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

requesting an investigation. The parents of the missing children were able to put so much pressure on Washington that meetings with President Johnson and Attorney General Robert Kennedy were arranged. Finally, after some 36 hours, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

authorized the FBI to get involved in the search. FBI agents began swarming around Philadelphia, Mississippi

Philadelphia is a city in and the county seat of Neshoba County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 7,118 at the 2020 census.

History

Philadelphia is incorporated as a municipality; it was given its current name in 1903, two years ...

, where Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner had been arrested after they had investigated the burning of a local black church that was a center for political organizing. For the next seven weeks, FBI agents and sailors from a nearby naval airbase searched for the bodies, wading into swamps and hacking through underbrush. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

went to Mississippi on July 10 to open the first FBI branch office there.

Throughout the search, Mississippi newspapers and word-of-mouth perpetuated the common belief that the disappearance was "a hoax" designed to draw publicity. The search of rivers and swamps turned up the bodies of eight other blacks who appeared to have been murdered: a boy and seven men. Herbert Oarsby, a 14-year-old youth, was found wearing a CORE T-shirt. Charles Eddie Moore

''Mississippi Cold Case'' is a 2007 feature documentary produced by David Ridgen of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation about the Ku Klux Klan murders of two 19-year-old black men, Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, in Southwest Missis ...

was among 600 students expelled in April 1964 from Alcorn A&M for participating in civil rights protests. After he returned home, he was abducted and killed by KKK members in Franklin County, Mississippi

Franklin County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 8,118, making it the fourth-least populous county in Mississippi. Its county seat is Meadville. The county was formed on December 2 ...

on May 2, 1964 with his friend Henry Hezekiah Dee

''Mississippi Cold Case'' is a 2007 feature documentary produced by David Ridgen of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation about the Ku Klux Klan murders of two 19-year-old black men, Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, in Southwest Missi ...

. The other five men were never identified. When they disappeared

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organi ...

, their families could not get local law enforcement to investigate.

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

With participation in the regular Mississippi Democratic Party blocked bysegregationists

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Internati ...

, COFO established the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party created in 1964 as a branch of the populist Freedom Democratic organization in the state of Mississippi during the ...

(MFDP) as a non-exclusionary rival to the regular party organization. It intended to gain recognition of the MFDP by the national Democratic Party as the legitimate party organization in Mississippi. Delegates were elected to go to the Democratic national convention to be held that year.

Before the convention was held, Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

gained passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

When the forces of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

continued to block black voter registration, the Summer Project switched to building the MFDP

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party created in 1964 as a branch of the populist Freedom Democratic organization in the state of Mississippi during th ...

. Though the MFDP challenge had wide support among many convention delegates, Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

feared losing Southern support in the coming campaign. He did not allow the MFDP to replace the regulars, but the continuing issue of political oppression in Mississippi was covered widely by the national press.

Freedom Schools

In addition to voter registration and the MFDP, the Summer Project also established a network of 30 to 40 voluntary summer schools – called "Freedom Schools Freedom Schools were temporary, alternative, and free schools for African Americans mostly in the South. They were originally part of a nationwide effort during the Civil Rights Movement to organize African Americans to achieve social, political and ...

," an educational program proposed by SNCC member, Charlie Cobb – as an alternative to Mississippi's totally segregated and underfunded schools for blacks. Over the course of the summer, more than 3,500 students attended Freedom Schools, which taught subjects that the public schools avoided, such as black history and constitutional rights.

Freedom Schools were held in churches, on back porches, and under the trees of Mississippi. Students ranged from small children to elderly adults, with the average age around 15. Most of the volunteer teachers were college students. Under the direction of Spelman College

Spelman College is a private, historically black, women's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of the Atlanta University Center academic consortium in Atlanta. Founded in 1881 as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, Spelman rece ...

professor Staughton Lynd, the goal was to teach voter literacy, and political organization skills, as well as academic skills, and to help with confidence. The curriculum was directly linked to the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. As Ed King

Edward Calhoun King (September 14, 1949 – August 22, 2018) was an American musician. He was a guitarist for the psychedelic rock band Strawberry Alarm Clock and guitarist and bassist for the Southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd from 1972 to 1975 ...

, who ran for Lieutenant Governor on the MFDP ticket, stated, "Our assumption was that the parents of the Freedom School children, when we met them at night, that the Freedom Democratic Party would be the PTA."

The Freedom Schools operated on a basis of close interaction and mutual trust between teachers and students. The core curriculum

In education, a curriculum (; : curricula or curriculums) is broadly defined as the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view ...

focused on basic literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

and arithmetic, black history and current status, political processes, civil rights, and the freedom movement. The content varied from place to place and day to day according to the questions and interests of the students.

The volunteer Freedom School teachers were as profoundly affected by their experience as were the students. Pam Parker, a teacher in the Holly Springs school, wrote of the experience:

The atmosphere in the class is unbelievable. It is what every teacher dreams about — real, honest enthusiasm and desire to learn anything and everything. The girls come to class of their own free will. They respond to everything that is said. They are excited about learning. They drain me of everything that I have to offer so that I go home at night completely exhausted but very happy in spirit ...

Freedom Libraries

Approximately fiftyFreedom libraries Freedom libraries were community libraries set up by activist organizations and private individuals to serve African Americans during the civil rights movement. Many of these libraries were established in the summer of 1964, during a broader project ...

were established throughout Mississippi. These libraries provided library services and literacy guidance for many African Americans, some who had never had access to libraries before. Freedom Libraries ranged in size from a few hundred volumes to more than 20,000. The Freedom Libraries operated on small budgets and were usually run by volunteers. Some libraries were housed in newly constructed facilities while others were located in abandoned buildings.

Freedom Houses

The volunteers were housed by local black families who refused to be intimidated by segregationist threats of violence. However, project organizers were unable to place all the volunteers in private homes. To accommodate the overflow, the remaining volunteers were placed either in the project office or in ''Freedom Houses.'' Volunteers believed that it was important to free themselves from their race and class backgrounds, so the Freedom Houses would become places where cultural exchange would happen, so the Freedom Houses were free from segregation. Of course, the practice of group living was already well established among American college students, for example, and soon the houses became communal living centers. Freedom houses also played a significant role in the volunteers' sexual activities during the summer. They considered themselves free from the restraints of racism and consequently free to truly love one another. As such, for many of them, interracial sex became the ultimate expression of SNCC ideology, which emphasized the notions of freedom and equality. At the beginning of the summer the Freedom Houses were places to accommodate the overflow of volunteers, but in the eyes of volunteers by the end of summer they had become structural and symbolical expressions of the link between personal and political change. One volunteer said:You never knew what was going to happen n the Freedom Housesfrom one minute to the next ... I slept on the cot ... on a kind of side porch ... and ... I'd drag in some nights and there'd ... be a wild party raging on the porch. So I'd drag my cot off in search of a quiet corner ... nly to findan intense philosophical discussion going on in one corner ... people making peanut butter sandwiches-always peanut butter ... in another ... ndsome soap opera ... romantic entanglement being played out in another ... It was real three-ring circus

Aftermath

Freedom Summer did not succeed in getting many voters registered, but it had a significant effect on the course of the Civil Rights Movement. It helped break down the decades of isolation and repression that had supported the Jim Crow system. Before Freedom Summer, the national news media had paid little attention to the persecution of black voters in the Deep South and the dangers endured by black civil rights workers. The events that summer had captured national attention (as had the mass protests and demonstrations in previous years). Some black activists felt the media had reacted only because northern white students were killed and felt embittered. Many blacks also felt the white students were condescending and paternalistic to the local people and were ascending to an inappropriate dominance over the civil rights movement. Leading up to the November 1964 election, repression persisted in Mississippi, with nuisance arrests, beatings, and church burnings continuing. The discontent with the white students and the increasing need for armed defense against segregationists helped create demand for a black power direction in SNCC. Many of the volunteers have recounted that the summer was one of the defining periods of their lives. They had trouble readjusting to life outside Mississippi. They came with a positive image of the government, but the events of the Freedom Summer upset this simplistic distinction between 'good guys' and 'bad guys'. They saw that those two ideas were linked together. They experienced such lawlessness that they became critical toward American society and federal agencies, like the FBI. Most of the volunteers became politicized in Mississippi. They left intent on carrying on the fight in the North. After that summer, many Christians faced a religious crisis. Personal transformation of volunteers led to social changes. It increased student activity in the civil rights movement. These students also played a role later in the resurgence of leftist activism in the United States. Long-term volunteers staffed the COFO and SNCC offices throughout Mississippi. After the flood of summer workers in 1964, their leadership decided that projects should continue the following summer, but under the direction of local leadership. This was challenged by Northern establishment members of the coalition, beginning withAmericans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) is a liberal American political organization advocating progressive policies. ADA views itself as supporting social and economic justice through lobbying, grassroots organizing, research, and supporting pro ...

, who also disapproved of the MFDP

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party created in 1964 as a branch of the populist Freedom Democratic organization in the state of Mississippi during th ...

. This encouraged the NAACP to withdraw from COFO, both because they did not want to anger liberal Democrats, and because they resented the organizational competition from SNCC. After the MFDP was denied voting status at the 1964 Democratic National Convention

The 1964 Democratic National Convention of the Democratic Party, took place at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey from August 24 to 27, 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson was nominated for a full term. Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minn ...

, Bob Moses was deeply disillusioned and bowed out of both MFDP and COFO. COFO collapsed in 1965, leaving organizing priorities to be set by locals.

Among many notable veterans of Freedom Summer were Heather Booth

Heather Booth (born December 15, 1945) is an American civil rights activist, feminist, and political strategist who has been involved in activism for progressive causes. During her student years, she was active in both the civil rights movement ...

, Marshall Ganz

Marshall Ganz (born March 14, 1943) is the Rita T. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Introduced to organizing in Civil Rights Movement, he worked on the s ...

, and Mario Savio

Mario Savio (December 8, 1942 – November 6, 1996) was an American activist and a key member of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement. He is most famous for his passionate speeches, especially the "Bodies Upon the Gears" address given at Spro ...

. After the summer, Heather Booth returned to Illinois, where she became a founder of the Chicago Women's Liberation Union

The Chicago Women's Liberation Union (CWLU) was an American feminist organization founded in 1969 at a conference in Palatine, Illinois.

The main goal of the organization was to end gender inequality and sexism, which the CWLU defined as "the sy ...

and later the Midwest Academy

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

. Marshall Ganz returned to California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, where he worked for many years on the staff of the United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

. He later taught organizing strategies. In 2008 he played a crucial role in organizing Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

's field staff for the campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

*Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* Bl ...

. Mario Savio returned to the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, where he became a leader of the Free Speech Movement

The Free Speech Movement (FSM) was a massive, long-lasting student protest which took place during the 1964–65 academic year on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley. The Movement was informally under the central leadership of Be ...

.

In Mississippi, controversy raged over the three murders. Mississippi state and local officials did not indict

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of an ...

anyone. The FBI continued to investigate. Agents infiltrated the KKK and paid informers to reveal secrets of their "klaverns". In the fall of 1964, informants told the FBI about the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. On December 4, the FBI arrested 19 men as suspects.

All were freed on a technicality, starting a three-year battle to bring them to justice. In October 1967, the men, including the Klan's Imperial Wizard Samuel Bowers

Samuel Holloway Bowers (August 25, 1924 – November 5, 2006) was a convicted murderer and a leading white supremacist in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. He was Grand Dragon of the Mississippi Original Knights of the Ku Klux Kla ...

, who had allegedly ordered the murders, went on trial in the federal courthouse in Meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

. Seven were ultimately convicted of federal crimes related to the murders. All were sentenced to 3–10 years, but none served more than six years. This marked the first time since Reconstruction era that white men had been convicted of civil rights violations against blacks in Mississippi.

Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

, which provided for federal oversight and enforcement to facilitate registration and voting in areas of historically low turnout. Mississippi's legislature passed several laws to dilute the power of black votes. Only with Supreme Court rulings and more than a decade of cooling did black voting become a reality in Mississippi. The seeds planted during Freedom Summer bore fruit in the 1980s and 1990s, when Mississippi elected more black officials than any other state. Since redistricting in 2003, Mississippi has had four congressional districts. Mississippi's 2nd congressional district, covering a concentration of black population in the western part of the state, including the Mississippi Delta, is black majority.

Renewed investigation of the 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner led to a trial by the state in 2005. As a result of investigative reporting by Jerry Mitchell (an award-winning reporter for the ''Jackson Clarion-Ledger

''The Clarion Ledger'' is an American daily newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi. It is the second-oldest company in the state of Mississippi, and is one of the few newspapers in the nation that continues to circulate statewide. It is an operating d ...

''), high school teacher Barry Bradford, and three of his students from Illinois (Brittany Saltiel, Sarah Siegel, and Allison Nichols), Edgar Ray Killen

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was an American Ku Klux Klan organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists participating in the ...

, one of the leaders of the killings and a former Ku Klux Klan klavern recruiter, was indicted for murder. He was convicted of three counts of manslaughter. The Killen verdict was announced on June 21, 2005, the forty-first anniversary of the crime. Killen's lawyers appealed the verdict, but his sentence of 3 times 20 years in prison was upheld on January 12, 2007, in a hearing by the Supreme Court of Mississippi.

See also

* African-American–Jewish relations *Carpenters for Christmas

Carpenters for Christmas was conceived to counteract a series of church bombings and arson attacks in Mississippi during and following the Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964. During the summer of 1964, the Council of Federated Organizations (CO ...

* '' Summer in Mississippi''

References

Bibliography

*Clayborne Carson

Clayborne Carson (born June 15, 1944) is an American academic who is a professor of history at Stanford University and director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Since 1985, he has directed the Martin Luther King ...

, ''In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s'' (Harvard University Press, 1981).

*Doug McAdam

Doug McAdam (born August 31, 1951) is Professor of Sociology at Stanford University. He is the author or co-author of over a dozen books and over fifty articles, and is widely credited as one of the pioneers of the political process model in socia ...

, ''Freedom Summer'' (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

* Bruce Watson, ''Freedom Summer: The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy'' (New York, NY: Viking, 2010).

Further reading

* Hamer, Fannie Lou''The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer: To Tell it Like it is'

Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2011. . * *

Sally Belfrage

Sally Belfrage (October 4, 1936 – March 14, 1994) was a United States-born British-based 20th century non-fiction writer and international journalist. Her writing covered turmoils in Northern Ireland, the American Civil Rights Movement and her ...

, ''Freedom Summer'' (University of Virginia Press, 1965, reissued 1990).

*Susie Erenrich, editor, ''Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: An Anthology of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement'' (Montgomery, AL: Black Belt Press, 1999).

*Matt Herron, ''Mississippi Eyes: The Story and Photography of the Southern Documentary Project'', Talking Fingers Publications, 2014

*Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild (; born October 5, 1942) is an American author, journalist, historian and lecturer. His best-known works include '' King Leopold's Ghost'' (1998), '' To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914–1918'' (2011), ''Bu ...

, ''Finding the Trapdoor: Essays, Portraits, Travels'' (Syracuse University Press, 1997), "Summer of Violence," pp. 140–150. .

*

*William Sturkey and Jon Hale, eds., ''To Write in the Light of Freedom: Newspapers of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools'' (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2015)

*Steven M. Gillon "10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America" (Three Rivers Press, New York, 2006)

External links

SNCC Digital Gateway: Freedom Summer

Digital documentary website created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, telling the story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee & grassroots organizing from the inside-out

*

Freedom Summer Digital Collection

- Miami University of Ohio

Freedom Summer National Conference - 2009

- Miami University of Ohio

Freedom Summer 50th

Miami University of Ohio, 2014

Mississippi Burning (LBJ tapes and documents)

- University of Virginia

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

Freedom On My Mind

a documentary distributed by

California Newsreel

California Newsreel, was founded in 1968 as the San Francisco branch of the national film making collective Newsreel. It is an American non-profit, social justice film distribution and production company still based in San Francisco, California. Th ...

"We had Sneakers, They Had Guns,"

Webcast and event flier essay from the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

, American Folklife Center

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. was created by Congress in 1976 "to preserve and present American Folklife". The center includes the Archive of Folk Culture, established at the library in 1928 as a repo ...

, May 5, 2009 lecture. Illustrator and journalist Tracy Sugarman describes his experiences covering the voting registration efforts during the 1964 "Freedom Summer." The talk is related to the publication of Sugarman's book of the same title. Retrieved August 25, 2009.Mississippi & Freedom Summer

- The Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s

- University of Southern Mississippi

SNCC History and Geography

from the Mapping American Social Movements project at the University of Washington

Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive (USM)

- American RadioWorks

Mississippi Digital Library

Original photographs, documents oral history, letters from the Mississippi freedom movement *

Carpenters for Christmas

Carpenters for Christmas was conceived to counteract a series of church bombings and arson attacks in Mississippi during and following the Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964. During the summer of 1964, the Council of Federated Organizations (CO ...

Project to Rebuild Antioch Missionary Baptist Church, Tippah County, Mississippi, burned after a speech held there by Fannie Lou HamerThe 1964 MS Freedom School Curriculum

~ Education and Democracy

Freedom Summer

Civil Rights Digital Library {{Portal bar, Freedom of speech, Journalism, Language, Law, Society, United States 1964 in Mississippi 1964 in the United States 1964 protests African-American history of Mississippi Civil rights movement History of African-American civil rights History of voting rights in the United States Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee