Fuero on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from

''Fuero'' dates back to the

''Fuero'' dates back to the

1125

1127–47

1129

1133

1145

1147

1152

''c''. 1154

1157

1169

1173

1173

1175

1181

1198

1198 Grantor(s)

Estefanía Sánchez

Íñigo Jiménez

María Fernández

Martín and Elvira Pérez

Sancha Ponce

Gonzalo, Constanza and Jimena Osorio

Pedro Pérez and Fernando Cídez

Gutierre Díaz

San Cebrián de Campos

Villarmildo

Yanguas

Castrocalbón

Molina

Villarratel

Azaña

Villalobos

Almaraz de Duero

Barruecopardo

Villavaruz de Ríoseco

Cifuentes de Rueda

' s character,

Inquisición

' at the

Statute of Estella

initially garnering a majority of the votes, but controversially failing to take off (Pamplona, 1932). Four years later and amid a climate of war, Basque nationalists supported the

''Noticias históricas de las tres provincias vascongadas''

Tomo II, Capitulo I.'' (1800) Available (in Spanish) online through the Digital Library of the Sancho El Sabio Foundation.''

"Los Fueros de Navarra: Exposición"

- discussion of fueros on the official web site of the Navarrese government (in Spanish). *Much of the discussion of the Basque ''fueros'' comes from :es:Nacionalismo vasco in the Spanish-language Wikipedia; last updated from the version dated 11:44 23 Sep, 2004.

Fueros de la Rioja

a collection of the local Medieval charters of several towns in

Fuero

at the Dictionary of the

Historia de la legislación y recitaciones del derecho civil de España : Fueros de Navarra, Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa y Alava

', 2ª ed. corr. y aum., ("History of the legislation and recitations of the civil law of Spain; 2nd edition corrected and augmented") Madrid : .n. 1868 (Impr. de los Sres. Gasset, Loma y compañia) p.; 8º mayr is available on the site of the Biblioteca Nacional Española. Basque Navarre Spanish language Legal terminology Basque history Politics of Spain Carlism Legal history of Spain

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

terms and ; all of these words have related, but somewhat different meanings.

The Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

term has a wide range of meanings, depending upon its context. It has meant a compilation of laws, especially a local or regional one; a set of laws specific to an identified class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

or estate (for example , comparable to a military code of justice, or , specific to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

). In many of these senses, its equivalent in medieval England

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England during the medieval period, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the Early Modern period in 1485. When England emerged from the collapse of the Roman Empire, the econ ...

would be the custumal

A custumal is a medieval-English document that stipulates the economic, political, and social customs of a manor or town. It is common for it to include an inventory of customs, regular agricultural, trading and financial activities as well as l ...

.

In the 20th century, Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

's regime used the term for several of the fundamental laws. The term implied these were not constitutions subject to debate and change by a sovereign people, but orders from the only legitimate source of authority, as in feudal times.

Characteristics

''Fuero'' dates back to the

''Fuero'' dates back to the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

era: the lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or ar ...

could concede or acknowledge a ''fuero'' to certain groups or communities, most notably the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the military, and certain regions that fell under the same monarchy as Castile or, later, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, but were not fully integrated into those countries.

The relations among ''fueros'', other bodies of law (including the role of precedent), and sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

is a contentious one that influences government and law in the present day. The king of León, Alfonso V, decreed the Fuero de León (1017), considered the earliest laws governing territorial and local life, as it applied to the entire kingdom, with certain provisions for the city of León. The various Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

provinces also generally regarded their ''fueros'' as tantamount to a municipal constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. This view was accepted by some others, including President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

. He cited the Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

B ...

an ''fueros'' as a precedent for the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

. (Adams, ''A defense…'', 1786) This view regards ''fueros'' as granting or acknowledging rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical the ...

. In the contrasting view, ''fueros'' were privileges granted by a monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

. In the letter Adams also commented on the substantial independence of the hereditary Basque Jauntxo families as the origin for their privileges.

In practice, distinct ''fueros'' for specific classes, estates, towns, or regions usually arose out of feudal power politics. Some historians believe monarchs were forced to concede some traditions in exchange for the general acknowledgment of his or her authority, that monarchs granted fueros to reward loyal subjection, or (especially in the case of towns or regions) the monarch simply acknowledged distinct legal traditions.

In medieval Castilian law, the king could assign privileges to certain groups. The classic example of such a privileged group was the Roman Catholic Church: the clergy did not pay taxes to the state, enjoyed the income via tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

of local landholding, and were not subject to the civil court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

s. Church-operated ecclesiastical courts tried churchmen for criminal offenses. Another example was the powerful Mesta organization, composed of wealthy sheepherders, who were granted vast grazing rights

Grazing rights is the right of a user to allow their livestock to feed (graze) in a given area.

United States

Grazing rights have never been codified in United States law, because such common-law rights derive from the English concept of the ...

in Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

after that land was reconquered by Spanish Christians from the Muslims (''see Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

''). Lyle N. McAlister writes in ''Spain and Portugal in the New World'' that the Mesta's ''fuero'' helped impede the economic development of southern Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. This resulted in a lack of opportunity, and Spaniards emigrated to the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

to escape these constraints.

Aristocratic ''fueros''

During the Reconquista, the feudal lords granted ''fueros'' to some ''villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

s'' and cities

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

, to encourage the colonization of the frontier and of commercial routes. These laws regulated the governance and the penal

Penal is a town in south Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago. It lies south of San Fernando, Princes Town, and Debe, and north of Moruga, Morne Diablo and Siparia. It was originally a rice- and cocoa-producing area but is now a rapidly expanding and ...

, process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

*Business process, activities that produce a specific se ...

and civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

aspects of the places. Often the ''fueros'' already codified for one place were granted to another, with small changes, instead of crafting a new redaction from scratch.

Date

1125

1127–47

1129

1133

1145

1147

1152

''c''. 1154

1157

1169

1173

1173

1175

1181

1198

1198 Grantor(s)

Gutierre Fernández de Castro

Gutierre Fernández de Castro ( flourished 1124–66) was a nobleman and military commander from the Kingdom of Castile. His career in royal service corresponds exactly with the reigns of Alfonso VII (1126–57) and his son Sancho III (1157–58). ...

and Toda DíazPedro González de Lara

Pedro González de Lara (died 16 October 1130) was a Castilian magnate. He served Alfonso VI as a young man, and later became the lover of Alfonso's heiress, Queen Urraca. He may have joined the First Crusade in the following of Raymond IV of Tou ...

and EvaEstefanía Sánchez

Alfonso VII

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

Íñigo Jiménez

Osorio Martínez

Osorio Martínez ( la, Osorius Martini) (bef. 1108 – March 1160) was a magnate from the Province of León in the Empire of Alfonso VII. He served as the emperor militarily throughout his long career, which peaked in 1138–41. Besides the documen ...

and Teresa FernándezMaría Fernández

Manrique Pérez de Lara

Manrique Pérez de Lara (died 1164) was a magnate of the Kingdom of Castile and its regent from 1158 until his death. He was a leading figure of the House of Lara and one of the most important counsellors and generals of three successive Castilian ...

Martín and Elvira Pérez

Sancha Ponce

Ponce de Minerva

Ponce de Minerva (1114/1115 – 27 July 1175) was a nobleman, courtier, governor, and general serving, at different times, the kingdoms of León and Castile. Originally from Occitania, he came as a young man to León (1127), where he was raised ...

Gonzalo, Constanza and Jimena Osorio

Pedro Pérez and Fernando Cídez

Ermengol VII of Urgell

Ermengol VII (or Armengol VII) (died 1184) was the Count of Urgell from 1154 to his death. He was called ''el de Valencia''.

The son of Ermengol VI and his first wife, Arsenda of Cabrera, in 1157, Ermengol VII married Dulce, daughter of Roger III ...

Gutierre Díaz

Froila Ramírez

Froila Ramírez, also spelled Fruela or Froilán ('' fl.'' 11501202), was a Leonese nobleman and a member of the Flagínez family. His power and influence lay chiefly in the heart of the province of León and its west, but it extended also into ...

and Sancha

Grantee(s)San Cebrián de Campos

Tardajos

Tardajos is a municipality and town located in the province of Burgos, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2014 census (INE), the municipality has a population of 950 inhabitants.

History

Tardajos received a ''fuero'' from Count Pedro G ...

Villarmildo

Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the list of states of Mexico, state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Me ...

Yanguas

Villalonso

Villalonso is a municipality located in the province of Zamora, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census (INE), the municipality has a population of 116 inhabitants.

In 1147 Osorio Martínez granted a ''fuero'' to Villalonso with ...

and Benafarces

Benafarces is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census (INE), the municipality had a population of 114 inhabitants.

In 1147 Osorio Martínez granted a ''fuero

(), (), () ...

Castrocalbón

Molina

Pozuelo de la Orden

Pozuelo de la Orden is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members o ...

Villarratel

Azaña

Villalobos

Almaraz de Duero

Barruecopardo

Villavaruz de Ríoseco

Cifuentes de Rueda

Basque and Pyrenean ''fueros''

Approach

In contemporary Spanish usage, the word ''fueros'' most often refers to the historic and contemporary ''fueros'' or charters of certain regions, especially of the Basque regions. The equivalent for French usage is ''fors'', applying to the northern regions of the Pyrenees. The whole central and western Pyrenean region was inhabited by the Basques in the early Middle Ages within theDuchy of Vasconia

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a medieval country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between " ...

. The Basques and the Pyrenean peoples—as Romance language replaced Basque in many areas by the turn of the first millennium—governed themselves by a native a set of rules, different from Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

and Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

law but with an ever-increasing imprint of them. Typically their laws, arising from regional traditions and practices, were kept and transmitted orally. Because of this oral tradition, the Basque-language regions preserved their specific laws longer than did those Pyrenean regions that adopted Romance languages. For example, Navarrese law developed along less feudal lines than those of surrounding realms. The Fors de Bearn are another example of Pyrenean law.

Two sayings address this legal idiosyncrasy: "en Navarra hubo antes leyes que reyes," and "en Aragón antes que rey hubo ley," both meaning that law developed and existed before the kings. The force of these principles required monarchs to accommodate to the laws. This situation sometimes strained relations between the monarch and the kingdom, especially if the monarchs were alien to native laws.

''Fueros'' in the High and Late Middle Ages

In 1234 when the first foreign king, the French Theobald I of Champagne arrived in the area, he did not know Navarrese common law. He appointed a commission to write the laws; this was the first written ''fuero''. The accession of French lineages to the throne of Navarre brought a relationship between the king and the kingdom that was alien to the Basques. The resulting disagreements were a major factor in the 13th-century uprisings and clashes between different factions and communities, e.g. the borough wars of Pamplona. The loyalty of the Basques (the ''Navarri'') to the king was conditioned on his upholding the traditions and customs of the kingdom, which were based on oral laws.Relations with the crown and rise of absolutism

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

conquered and annexed Navarre between 1512 and 1528 (up to the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

). In order to gain Navarrese loyalty, the Spanish Crown represented by the Aragonese Fernando upheld the kingdom's specific laws (''fueros'') allowing the region to continue to function under its historic laws, while Lower Navarre

Lower Navarre ( eu, Nafarroa Beherea/Baxenabarre; Gascon/Bearnese: ''Navarra Baisha''; french: Basse-Navarre ; es, Baja Navarra) is a traditional region of the present-day French ''département'' of Pyrénées-Atlantiques. It corresponds to the ...

remained independent, but increasingly tied to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, a process completed after King Henry III of Navarre and IV of France died. Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

failed to respect his father's will to keep Navarre and France separate. All specific relevant legal provisions and institutions (Parliament, Courts of Justice, etc.) were devalued in 1620–1624, and critical powers transferred to the French Crown.

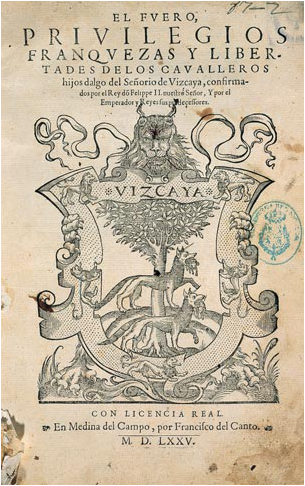

Since the high Middle Ages, many Basques had been born into the ''hidalgo

Hidalgo may refer to:

People

* Hidalgo (nobility), members of the Spanish nobility

* Hidalgo (surname)

Places

Mexico

* Hidalgo (state), in central Mexico

* Hidalgo, Coahuila, a town in the north Mexican state of Coahuila

* Hidalgo, Nuevo Le� ...

nobility''. The Basques had no uniform legal corpus of laws, which varied between valleys and seigneuries. Early on (14th century) all Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa (, , ; es, Guipúzcoa ; french: Guipuscoa) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French depa ...

ns were granted noble status, several Navarrese valleys ( Salazar, Roncal, Baztan, etc.) followed suit, and Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

B ...

nes saw their universal nobility confirmed in 1525. Álava

Álava ( in Spanish) or Araba (), officially Araba/Álava, is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Álava, former medieval Catholic bishopric and now Latin titular see.

Its c ...

's distribution of nobility was patchy but less widespread, since the Basque specific nobility only took hold in northern areas (Ayala

Ayala may refer to:

Places

* Ciudad Ayala, Morelos, Mexico

* Ayala Alabang, a barangay in Muntinlupa, Philippines

* Ayala Avenue, a major thoroughfare in the Makati Central Business District, Philippines

* Ayala, Magalang, a barrio in Magalang ...

, etc.). Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

B ...

nes, as nobles, were theoretically excluded from torture and from the need to serve in the Spanish army, unless called for the defence of their own territory (''Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of Wester ...

''Sancho Panza

Sancho Panza () is a fictional character in the novel ''Don Quixote'' written by Spanish author Don Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra in 1605. Sancho acts as squire to Don Quixote and provides comments throughout the novel, known as ''sanchismos'', ...

, remarked humorously that writing and reading and being ''Biscayne'' was enough to be secretary to the emperor). Other Basque regions had similar provisions.

The Castilian kings took an oath to comply with the Basque laws in the different provinces of Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa. These provinces and Navarre kept their self-governing bodies and their own parliaments, i.e. the ''diputaciones'' and the territorial councils/Parliament of Navarre

The Parliament of Navarre ( Spanish ''Parlamento de Navarra'', Basque ''Nafarroako Parlamentua'') or also known as ''Cortes de Navarra'' (in Spanish) or ''Nafarroako Gorteak'' (in Basque) is the Navarre autonomous unicameral parliament.

Functio ...

. However, the prevailing Castilian rule prioritized the king's will. In addition, the ever more centralizing absolutism, especially after the accession to the throne of the Bourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

, increasingly devalued the laws specific to regions and realms—Basque provinces and the kingdoms of Navarre and Aragon—sparking uprisings (Matalaz's uprising in Soule

Soule (Basque language, Basque: Zuberoa; Zuberoan/ Soule Basque: Xiberoa or Xiberua; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Sola'') is a former viscounty and France, French Provinces of France, province and part of the present-day Pyrénées-Atlantiques ...

1660, regular ''Matxinada'' revolts in the 17-18th centuries) and mounting tensions between the territorial governments and the Spanish central government of Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

and Charles IV, to the point of considering the Parliament of Navarre

The Parliament of Navarre ( Spanish ''Parlamento de Navarra'', Basque ''Nafarroako Parlamentua'') or also known as ''Cortes de Navarra'' (in Spanish) or ''Nafarroako Gorteak'' (in Basque) is the Navarre autonomous unicameral parliament.

Functio ...

dangerous to the royal authority and condemning "its spirit of independence and liberties."

Despite vowing loyalty to the crown, the Pyrenean Aragonese and Catalans kept their separate specific laws too, the "King of the Spains" represented a crown tying together different realms and peoples, as claimed by the Navarrese ''diputación'', as well as the Parliament of Navarre

The Parliament of Navarre ( Spanish ''Parlamento de Navarra'', Basque ''Nafarroako Parlamentua'') or also known as ''Cortes de Navarra'' (in Spanish) or ''Nafarroako Gorteak'' (in Basque) is the Navarre autonomous unicameral parliament.

Functio ...

's last trustee. The Aragonese ''fueros'' were an obstacle for Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

when his former secretary Antonio Pérez escaped the death penalty by fleeing to Aragon. The king's only means to enforce the sentence was the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

, the only cross-kingdom tribunal of his domains. There were frequent conflicts of jurisdiction between the Spanish Inquisition and regional civil authorities and bishops.Inquisición

' at the

Auñamendi Encyclopedia

The Auñamendi Encyclopedia is the largest encyclopedia of Basque culture and society, with 120,000 articles and more than 67,000 images.

History

Founded in 1958 by the Estornés Lasa brothers, Bernardo and Mariano. He began publishing in 196 ...

. Pérez escaped to France, but Philip's army invaded Aragon and executed its authorities.

In 1714 the Catalan and Aragonese specific laws and self-government were violently suppressed. The Aragonese count of Robres, one strongly opposing the abolition, put it down to Castilian centralism, stating that the royal prime minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares, had at last a free rein "for the kings of Spain to be independent of all laws save those of their own conscience."

The Basques managed to retain their specific status for a few years after 1714, as they had supported the claimant who became Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mon ...

, a king hailing from the lineage of Henry III of Navarre

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarc ...

. However, they could not escape the king's attempts (using military force) at centralization (1719–1723). In the run-up to the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the relations between the absolutist Spanish Crown and the Basque governing institutions were at breaking point. By the beginning of the War of the Pyrenees

The War of the Pyrenees, also known as War of Roussillon or War of the Convention, was the Pyrenean front of the First Coalition's war against the First French Republic. It pitted Revolutionary France against the kingdoms of Spain and Portug ...

, Manuel Godoy

Manuel Godoy y Álvarez de Faria, Prince of the Peace, 1st Duke of Alcudia, 1st Duke of Sueca, 1st Baron of Mascalbó (12 May 17674 October 1851) was First Secretary of State of Spain from 1792 to 1797 and from 1801 to 1808. He received many t ...

took office as Prime Minister in Spain, and went on to take a tough approach on the Basque self-government and specific laws. Both fear and anger spread among the Basques at his uncompromising stance.

The end of the ''fueros'' in Spain

The 1789 Revolution brought the rise of the Jacobinnation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

—also referred to in a Spanish context as "unitarism", unrelated to the religious view of similar name. Whereas the French Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

recognized the regional specific laws, the new order did not allow for such autonomy. The jigsaw puzzle of fiefs was divided into ''département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level ("territorial collectivity, territorial collectivities"), between the regions of France, admin ...

s'', based on administrative and ideological concerns, not tradition. In the French Basque Country

The French Basque Country, or Northern Basque Country ( eu, Iparralde (), french: Pays basque, es, País Vasco francés) is a region lying on the west of the French department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. Since 1 January 2017, it constitu ...

, what little remained of self-government was suppressed in 1790 during the French Revolution and the new administrative arrangement, and was followed by the interruption of the customary cross-border trade between the Basque districts (holding minor internal customs or duties), the mass deportation to the Landes of thousands of residents in the bordering villages of Labourd—Sara, Itxassou

Itxassou (; Basque ''Itsasu'')ITSASU

Ascain Ascain (; eu, Azkaine) is a commune in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of south-western France. The inhabitants of the commune are known as ''Azkaindar''.

—, including the imposition (fleetingly) of alien names to villages and towns—period of the Ascain Ascain (; eu, Azkaine) is a commune in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of south-western France. The inhabitants of the commune are known as ''Azkaindar''.

National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

and War of the Pyrenees

The War of the Pyrenees, also known as War of Roussillon or War of the Convention, was the Pyrenean front of the First Coalition's war against the First French Republic. It pitted Revolutionary France against the kingdoms of Spain and Portug ...

(1793–1795).

Some Basques saw a way forward in the 1808 Bayonne Statute

The Bayonne Statute ( es, Estatuto de Bayona),Ignacio Fernández Sarasola Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Retrieved 2010-03-12. also called the Bayonne Constitution () or the Bayonne Charter (), was a constitution or a royal charter () a ...

and Dominique-Joseph Garat

Dominique Joseph Garat (8 September 17499 December 1833) was a French Basque Country, French Basque writer, lawyer, journalist, philosopher and politician.

Biography

Garat was born at Bayonne, in the French Basque Country. After a good educati ...

's project, initially approved by Napoleon, to create a separate Basque state, but the French invasive attitude on the ground and the deadlock of the self-government project led the Basques to find help elsewhere, i.e. local liberal or moderate commanders and public figures supportive of the ''fueros'', or the conservative Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

. The 1812 Spanish Constitution of Cadiz

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

received no Basque input, ignored the Basque self-government, and was accepted begrudgingly by the Basques, overwhelmed by war events. For example, the 1812 Constitution was signed by Gipuzkoan representatives to a general Castaños

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

wielding menacingly a sword, and tellingly the San Sebastián

San Sebastian, officially known as Donostia–San Sebastián (names in both local languages: ''Donostia'' () and ''San Sebastián'' ()) is a city and Municipalities of Spain, municipality located in the Basque Country (autonomous community), B ...

council representatives took an oath to the 1812 Constitution with the smell of smoke still wafting and surrounded by rubble.

During the two centuries since the French Revolution and the Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

ic Era, the level of autonomy for the Basque regions within Spain has varied. The cry for ''fueros'' (meaning regional autonomy) was one of the demands of the Carlists of the 19th century, hence the strong support for Carlism from the Basque Country and (especially in the First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

) in Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and Aragón

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises th ...

. The Carlist effort to restore an absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

was sustained militarily mainly by those whom the ''fueros'' had protected from the full weight of absolutism, due to their readiness to respect region and kingdom specific legal systems and institutions. The defeat of the Carlists in three successive wars resulted in continuing erosion of traditional Basque privileges.

The Carlist land-based small nobility (''jauntxos'') lost power to the new bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

ie, who welcomed the extension of Spanish customs

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out of a country. Traditionally, customs ...

borders from the Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

to the Pyrenees. The new borders protected the fledgling Basque industry from foreign competition and opened the Spanish market, but lost opportunities abroad since customs were imposed on the Pyrenees and the coast.

Echoes of the ''fueros'' after suppression in Spain

After theFirst Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

, the new class of Navarre negotiated separately from the rest of Basque districts the ''Ley Paccionada'' (or ''Compromise Act'') in Navarre (1841), which granted some administrative and fiscal prerogatives to the provincial government within Spain. The rest of the Basque districts managed to keep still for another 40 years a small status of self-government, definitely suppressed in 1876. The end of the Third Carlist War

The Third Carlist War ( es, Tercera Guerra Carlista) (1872–1876) was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is sometimes referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the earlier "Second" War (1847–1849) was smaller in scale and relatively trivial ...

saw the Carlists strong in the Basque districts succumb to the Spanish troops led by King Alfonso XII of Spain

Alfonso XII (Alfonso Francisco de Asís Fernando Pío Juan María de la Concepción Gregorio Pelayo; 28 November 185725 November 1885), also known as El Pacificador or the Peacemaker, was King of Spain from 29 December 1874 to his death in 188 ...

and their reduced self-government was suppressed and converted into Economic Agreements. Navarre's status was less altered in 1876 than that of Gipuzkoa, Biscay, and Álava, due to the separate agreement signed in 1841 by officials of the Government of Navarre with the Spanish government accepting the transformation of the kingdom into a Spanish province.

Despite capitulation agreements acknowledging specific administrative and economic prerogatives, attempts of the Spanish government to bypass them spread malaise and anger in the Basque districts, ultimately leading to the 1893–94 ''Gamazada'' uprising in Navarre. Sabino Arana

Sabino Policarpo Arana Goiri (in Spanish), Sabin Polikarpo Arana Goiri (in Basque), or Arana ta Goiri'taŕ Sabin (self-styled) (26 January 1865 – 25 November 1903), was a Basque writer and the founder of the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) ...

bore witness to the popular revolt as a Biscayne envoy to the protests.

The enthusiasm raised by the popular revolt in Navarre against the breach of war ending agreements made a deep impact on Sabino Arana, who went on to found the Basque Nationalist Party in 1895, based in Biscay but aiming beyond the boundaries of each Basque district, seeking instead a confederation of the Basque districts. Arana, of a Carlist background, rejected the Spanish monarchy and founded Basque nationalism

Basque nationalism ( eu, eusko abertzaletasuna ; es, nacionalismo vasco; french: nationalisme basque) is a form of nationalism that asserts that Basques, an ethnic group indigenous to the western Pyrenees, are a nation and promotes the poli ...

on the basis of Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and ''fueros'' (''Lagi-Zaŕa'', as he called them in Basque, "Old Law").

The high-water mark of a restoration of Basque autonomy in recent times came under the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

in the mid twentieth century. An attempt was made at restoring some kind of Basque self-government in thStatute of Estella

initially garnering a majority of the votes, but controversially failing to take off (Pamplona, 1932). Four years later and amid a climate of war, Basque nationalists supported the

left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

-leaning Republic as ardently as they had earlier supported the right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authorit ...

Carlists (note that contemporary Carlists supported Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

). The defeat of the Republic by the forces of Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

led in turn to a suppression of Basque culture, including banning the public use of the Basque language.

The Franco regime considered Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

B ...

and Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa (, , ; es, Guipúzcoa ; french: Guipuscoa) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French depa ...

as "traitor provinces" and cancelled their ''fueros''. However, the pro-Franco provinces of Álava

Álava ( in Spanish) or Araba (), officially Araba/Álava, is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Álava, former medieval Catholic bishopric and now Latin titular see.

Its c ...

and Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

maintained a degree of autonomy unknown in the rest of Spain, with local telephone companies, provincial limited-bailiwick police forces ('' miñones'' in Alava, and Foral Police in Navarre), road works and some taxes to support local government.

The post-Franco Spanish Constitution of 1978

The Spanish Constitution (Spanish, Asturleonese, and gl, Constitución Española; eu, Espainiako Konstituzioa; ca, Constitució Espanyola; oc, Constitucion espanhòla) is the democratic law that is supreme in the Kingdom of Spain. It was ...

acknowledged "historical rights" and attempted to compromise in the old conflict between centralism and federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments (Province, provincial, State (sub-national), state, Canton (administrative division), can ...

by establishing a constitutional provision catering to historic Catalan and Basque political demands, and leaving open the possibility of establishing their own autonomous communities

eu, autonomia erkidegoa

ca, comunitat autònoma

gl, comunidade autónoma

oc, comunautat autonòma

an, comunidat autonoma

ast, comunidá autónoma

, alt_name =

, map =

, category = Autonomous administra ...

. The Spanish Constitution speaks of "nationalities" and "historic territories", but does not define them. The term ''nationality'' itself was coined for the purpose, and neither Basques nor Catalans are specifically recognized by the Constitution.

After the 1981 coup d'état attempt and the ensuing passing of the restrictive LOAPA act, such possibility of autonomy got opened to whatever (reshaped) Spanish region demanded it (such as Castile and León

Castile and León ( es, Castilla y León ; ast-leo, Castiella y Llión ; gl, Castela e León ) is an autonomous community in northwestern Spain.

It was created in 1983, eight years after the end of the Francoist regime, by the merging of the ...

, Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

, etc.), even to those never struggling to have their separate identity recognized and always considering themselves invariably Spanish. The '' State of Autonomous Communities'' took the shape of administrative districts and was ambiguous as to the actual recognition of separate identities, coming to be known as ''café para todos'', or 'coffee for everyone'.

However, the provincial chartered governments (''Diputación Foral'' / ''Foru Aldundia'') in the Basque districts were restored, getting back significant powers. Other powers held historically by the chartered governments ("Diputación") were transferred to the new government of the Basque Country autonomous community. The Basque provinces still perform tax collection in their respective territories, coordinating with the Basque/Navarrese, Spanish, as well as European governments.

Today, the act regulating the powers of the government of Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

is the ''Amejoramiento del Fuero'' ("Betterment of the Fuero"), and the official name of Navarre is ''Comunidad Foral de Navarra'', ''foral'' ('chartered') being the adjectival form for ''fuero''. The reactionary governmental party in Navarre UPN

The United Paramount Network (UPN) was an American broadcast television network that launched on January 16, 1995. It was originally owned by Chris-Craft Industries' United Television. Viacom (through its Paramount Television unit, which pr ...

(2013) claimed during its establishment (1979) and at later times the validity and continuity of the institutional framework for Navarre held during Franco's dictatorship

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spani ...

(1936–1975), considering the present regional ''statu quo'' an "improvement" of its previous status.

Private law

While ''fueros'' have disappeared from administrative law in Spain, (except for the Basque Country and Navarre), there are remnants of the old laws infamily law

Family law (also called matrimonial law or the law of domestic relations) is an area of the law that deals with family matters and domestic relations.

Overview

Subjects that commonly fall under a nation's body of family law include:

* Marriage, ...

. When the Civil Code was established in Spain (1888) some parts of it did not run in some regions. In places like Galicia and Catalonia, the marriage contract

''Marriage Contract'' () is a 2016 South Korean television series starring Lee Seo-jin and Uee. It aired on MBC from March 5 to April 24, 2016 on Saturdays and Sundays at 22:00 for 16 episodes.

Plot

Kang Hye-soo (Uee) is a single mother who ...

s and inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, Title (property), titles, debts, entitlements, Privilege (law), privileges, rights, and Law of obligations, obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ ...

are still governed by local laws.

This has led to peculiar forms of land distribution.

These laws are not uniform. For example, in Biscay, different rules regulate inheritance in the ''villas'', than in the country towns (''tierra llana''). Modern jurists try to modernize the foral family laws while keeping with their spirit.

''Fueros'' in Spanish America

During the colonial era in Spanish America, theSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

extended ''fueros'' to the clergy, the ''fuero eclesiástico''. The crown attempted to curtail the ''fuero eclesiástico'', which gave the lower secular (diocesan) clergy privileges that separated them legally from their plebeian parishioners. The curtailment of the ''fuero'' has been seen as a reason why so many clerics participated in the Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de México, links=no, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from Spain. It was not a single, co ...

, including insurgency leaders Miguel Hidalgo

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican ...

and José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

. Removal of the ''fuero'' was seen by the Church as another act of the Bourbon Reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Monarchy, Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of ...

that alienated the Mexican population, including American-born Spaniards.

In the eighteenth century, when Spain established a standing military in key areas of its overseas territory, privileges were extended to the military, the ''fuero militar'', which had an impact on the colonial legal system and society. The ''fuero militar'' was the first time that privileges extended to plebeians, which has been argued was a cause of debasing justice. Indigenous men were excluded from the military, and inter-ethnic conflicts occurred. The ''fuero militar'' presented some contradictions in colonial rule.

In post-independence Mexico, formerly New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

, ''fueros'' continued to be recognized by the Mexican state until the mid-nineteenth century. As Mexican liberals gained power, they sought to implement the liberal ideal of equality before the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic ru ...

by eliminating special privileges of the clerics and the military. The Liberal Reform

Liberal Reform is a group of members of the British Liberal Democrats. Membership of the group is open to any Liberal Democrat party member, and is free of charge. It was launched on 13 February 2012, and describes itself as a broadly centrist g ...

and the liberal Constitution of 1857

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Co ...

's abolition of those ''fueros'' mobilized Mexico's conservatives, which fought a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, and rallied allies to their cause with the slogan ''religión y fueros'' ("religion and privileges").

For post-independence Chile, the ''fuero militar'' also was an issue concerning the rights and privileges of citizenship.

List of fueros

*Fueros of Navarre

The Fueros of Navarre ( es, Fuero General de Navarra, eu, Nafarroako Foru Orokorra, meaning in English ''General Charter of Navarre'') were the laws of the Kingdom of Navarre up to 1841, tracing its origins to the Early Middle Ages and issued from ...

* Fors de Bearn

* Furs de Valencia

* Fuero de Oreja

Notes

References

* Llorente, Juan Antoni''Noticias históricas de las tres provincias vascongadas''

Tomo II, Capitulo I.'' (1800) Available (in Spanish) online through the Digital Library of the Sancho El Sabio Foundation.''

"Los Fueros de Navarra: Exposición"

- discussion of fueros on the official web site of the Navarrese government (in Spanish). *Much of the discussion of the Basque ''fueros'' comes from :es:Nacionalismo vasco in the Spanish-language Wikipedia; last updated from the version dated 11:44 23 Sep, 2004.

Fueros de la Rioja

a collection of the local Medieval charters of several towns in

La Rioja

La Rioja () is an autonomous community and province in Spain, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, an ...

, in old Castilian or Latin.

Fuero

at the Dictionary of the

Real Academia Española

The Royal Spanish Academy ( es, Real Academia Española, generally abbreviated as RAE) is Spain's official royal institution with a mission to ensure the stability of the Spanish language. It is based in Madrid, Spain, and is affiliated with ...

.

Further reading

* * * *External links

{{Americana Poster, year=1920, Fuero * A digitized version of Amalio Marichalar, Marqués de Montesa,Historia de la legislación y recitaciones del derecho civil de España : Fueros de Navarra, Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa y Alava

', 2ª ed. corr. y aum., ("History of the legislation and recitations of the civil law of Spain; 2nd edition corrected and augmented") Madrid : .n. 1868 (Impr. de los Sres. Gasset, Loma y compañia) p.; 8º mayr is available on the site of the Biblioteca Nacional Española. Basque Navarre Spanish language Legal terminology Basque history Politics of Spain Carlism Legal history of Spain