Friendship paradox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The friendship paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that most people have fewer

The friendship paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that most people have fewer

The friendship paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that most people have fewer

The friendship paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that most people have fewer friend

Friendship is a relationship of mutual affection between people. It is a stronger form of interpersonal bond than an "acquaintance" or an "association", such as a classmate, neighbor, coworker, or colleague.

In some cultures, the concept of ...

s than their friends have, on average. It can be explained as a form of sampling bias

In statistics, sampling bias is a bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population have a lower or higher sampling probability than others. It results in a biased sample of a population (or non-human fa ...

in which people with more friends are more likely to be in one's own friend group. In other words, one is less likely to be friends with someone who has very few friends. In contradiction to this, most people believe that they have more friends than their friends have.

The same observation can be applied more generally to social network

A social network is a social structure made up of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), sets of dyadic ties, and other social interactions between actors. The social network perspective provides a set of methods for an ...

s defined by other relations than friendship: for instance, most people's sexual partners have had (on the average) a greater number of sexual partners than they have.

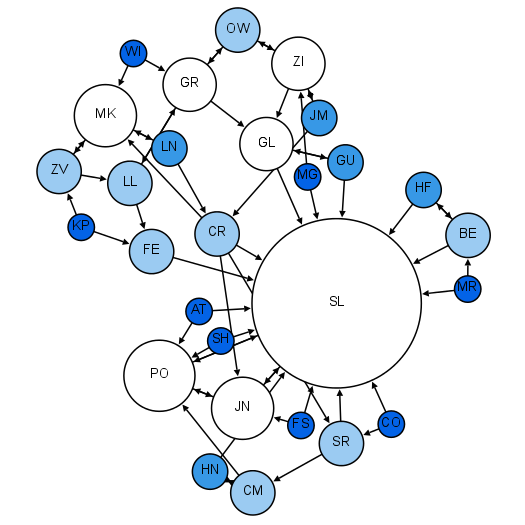

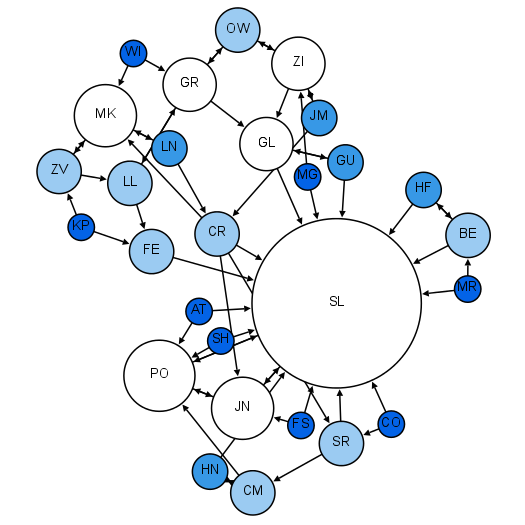

The friendship paradox is an example of how network structure can significantly distort an individual's local observations.

Mathematical explanation

In spite of its apparentlyparadox

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictory or a logically u ...

ical nature, the phenomenon is real, and can be explained as a consequence of the general mathematical properties of social network

A social network is a social structure made up of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), sets of dyadic ties, and other social interactions between actors. The social network perspective provides a set of methods for an ...

s. The mathematics behind this are directly related to the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality and the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality (also called Cauchy–Bunyakovsky–Schwarz inequality) is considered one of the most important and widely used inequalities in mathematics.

The inequality for sums was published by . The corresponding inequality fo ...

.

Formally, Feld assumes that a social network is represented by an undirected graph

In discrete mathematics, and more specifically in graph theory, a graph is a structure amounting to a set of objects in which some pairs of the objects are in some sense "related". The objects correspond to mathematical abstractions called '' v ...

, where the set of vertices corresponds to the people in the social network, and the set of edges corresponds to the friendship relation between pairs of people. That is, he assumes that friendship is a symmetric relation: if is a friend of , then is a friend of . The friendship between and is therefore modeled by the edge and the number of friends an individual has corresponds to a vertex's degree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

. The average number of friends of a person in the social network is therefore given by the average of the degrees of the vertices in the graph. That is, if vertex has edges touching it (representing a person who has friends), then the average number of friends of a random person in the graph is

:

The average number of friends that a typical friend has can be modeled by choosing a random person (who has at least one friend), and then calculating how many friends their friends have on average. This amounts to choosing, uniformly at random, an edge of the graph (representing a pair of friends) and an endpoint of that edge (one of the friends), and again calculating the degree of the selected endpoint. The probability of a certain vertex to be chosen is

:

The first factor corresponds to how likely it is that the chosen edge contains the vertex, which increases when the vertex has more friends. The halving factor simply comes from the fact that each edge has two vertices. So the expected value of the number of friends of a (randomly chosen) friend is

:

We know from the definition of variance that

:

where is the variance of the degrees in the graph. This allows us to compute the desired expected value as

:

For a graph that has vertices of varying degrees (as is typical for social networks), is strictly positive, which implies that the average degree of a friend is strictly greater than the average degree of a random node.

Another way of understanding how the first term came is as follows. For each friendship , a node mentions that is a friend and has friends. There are such friends who mention this. Hence the square of term. We add this for all such friendships in the network from both the 's and 's perspective, which gives the numerator. The denominator is the number of total such friendships, which is twice the total edges in the network (one from the 's perspective and the other from the 's).

After this analysis, Feld goes on to make some more qualitative assumptions about the statistical correlation between the number of friends that two friends have, based on theories of social networks such as assortative mixing In the study of complex networks, assortative mixing, or assortativity, is a bias in favor of connections between network nodes with similar characteristics. In the specific case of social networks, assortative mixing is also known as homophily. ...

, and he analyzes what these assumptions imply about the number of people whose friends have more friends than they do. Based on this analysis, he concludes that in real social networks, most people are likely to have fewer friends than the average of their friends' numbers of friends. However, this conclusion is not a mathematical certainty; there exist undirected graphs (such as the graph formed by removing a single edge from a large complete graph

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a complete graph is a simple undirected graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a unique edge. A complete digraph is a directed graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is c ...

) that are unlikely to arise as social networks but in which most vertices have higher degree than the average of their neighbors' degrees.

The Friendship Paradox may be restated in graph theory

In mathematics, graph theory is the study of ''graphs'', which are mathematical structures used to model pairwise relations between objects. A graph in this context is made up of '' vertices'' (also called ''nodes'' or ''points'') which are conne ...

terms as “the average degree of a randomly selected node in a network is less than the average degree of neighbors of a randomly selected node”, but this leaves unspecified the exact mechanism of averaging (i.e., macro vs micro averaging). Let be an undirected graph with and , having no isolated nodes. Let the set of neighbors of node be denoted . The average degree is then . Let the number of "friends of friends" of node be denoted . Note that this can count 2-hop neighbors multiple times, but so does Feld's analysis. We have . Feld considered the following "micro average" quantity.

:

However, there is also the (equally legit) "macro average" quantity, given by

:

The computation of MacroAvg can be expressed as the following pseudocode.

:# for each node

:## initialize

:# for each edge

:##

:##

:# return

Each edge contributes to MacroAvg the quantity , because . We thus get

:.

Thus, we have both and , but no inequality holds between them.

Applications

The analysis of the friendship paradox implies that the friends of randomly selected individuals are likely to have higher than averagecentrality

In graph theory and network analysis, indicators of centrality assign numbers or rankings to nodes within a graph corresponding to their network position. Applications include identifying the most influential person(s) in a social network, key ...

. This observation has been used as a way to forecast and slow the course of epidemic

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics ...

s, by using this random selection process to choose individuals to immunize or monitor for infection while avoiding the need for a complex computation of the centrality of all nodes in the network. In a similar manner, in polling and election forecasting, friendship paradox has been exploited in order to reach and query well-connected individuals who may have knowledge about how a lot of the others are going to vote.

A study in 2010 by Christakis and Fowler showed that flu outbreaks can be detected almost two weeks before traditional surveillance measures would do so by using the friendship paradox in monitoring the infection in a social network. They found that using the friendship paradox to analyze the health of central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

friends is "an ideal way to predict outbreaks, but detailed information doesn't exist for most groups, and to produce it would be time-consuming and costly."

Friendship paradox based sampling (i.e., sampling random friends) has been theoretically and empirically shown to outperform classical uniform sampling for the purpose of estimating the power-law degree distributions of scale-free networks

A scale-free network is a network whose degree distribution follows a power law, at least asymptotically. That is, the fraction ''P''(''k'') of nodes in the network having ''k'' connections to other nodes goes for large values of ''k'' as

:

P(k ...

. This is because sampling the network uniformly will not collect enough samples from the characteristic heavy tail

In probability theory, heavy-tailed distributions are probability distributions whose tails are not exponentially bounded: that is, they have heavier tails than the exponential distribution. In many applications it is the right tail of the distrib ...

part of the power-law degree distribution to properly estimate it. However, sampling random friends incorporates more nodes from the tail of the degree distribution (i.e., more high degree nodes) into the sample. Hence, friendship paradox based sampling captures the characteristic heavy tail of a power-law degree distribution more accurately and reduces the bias and variance of the estimation.

The "generalized friendship paradox" states that the friendship paradox applies to other characteristics as well. For example, one's co-authors are on average likely to be more prominent, with more publications, more citations and more collaborators, or one's followers on Twitter have more followers. The same effect has also been demonstrated for Subjective Well-Being by Bollen et al (2017), who used a large-scale Twitter network and longitudinal data on subjective well-being for each individual in the network to demonstrate that both a Friendship and a "happiness" paradox can occur in online social networks.

See also

*Second neighborhood problem

In mathematics, the second neighborhood problem is an unsolved problem about oriented graphs posed by Paul Seymour. Intuitively, it suggests that in a social network described by such a graph, someone will have at least as many friends-of-friends ...

* Self-evaluation maintenance theory Self-evaluation maintenance (SEM) concerns discrepancies between two people in a relationship. The theory posits an individual will maintain as well as enhance their self-esteem via a social comparison to another individual. Self-evaluation refers t ...

References

External links

* {{Social networking Statistical paradoxes Social networks Graph theory Friendship