French Mandate For Syria And The Lebanon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate founded in the aftermath of the First World War and the

The new Arab administration formed local governments in the major Syrian cities, and the pan-Arab flag was raised all over Syria. The Arabs hoped, with faith in earlier British promises, that the new Arab state would include all the Arab lands stretching from Aleppo in northern Syria to Aden in southern

The new Arab administration formed local governments in the major Syrian cities, and the pan-Arab flag was raised all over Syria. The Arabs hoped, with faith in earlier British promises, that the new Arab state would include all the Arab lands stretching from Aleppo in northern Syria to Aden in southern  France demanded full implementation of the Sykes–Picot Agreement, with Syria under its control. On 26 November 1919, British forces withdrew from Damascus to avoid confrontation with the French, leaving the Arab government to face France. Faisal had travelled several times to Europe since November 1918, trying to convince France and Britain to change their positions, but without success. France's determination to intervene in Syria was shown by the naming of General Henri Gouraud as high commissioner in Syria and

France demanded full implementation of the Sykes–Picot Agreement, with Syria under its control. On 26 November 1919, British forces withdrew from Damascus to avoid confrontation with the French, leaving the Arab government to face France. Faisal had travelled several times to Europe since November 1918, trying to convince France and Britain to change their positions, but without success. France's determination to intervene in Syria was shown by the naming of General Henri Gouraud as high commissioner in Syria and  Unrest erupted in Syria when Faisal accepted a compromise with French Prime Minister Clemenceau. Anti-

Unrest erupted in Syria when Faisal accepted a compromise with French Prime Minister Clemenceau. Anti-

Greater Lebanon was created by France to be a "safe haven" for the Maronite population of the ''

Greater Lebanon was created by France to be a "safe haven" for the Maronite population of the ''

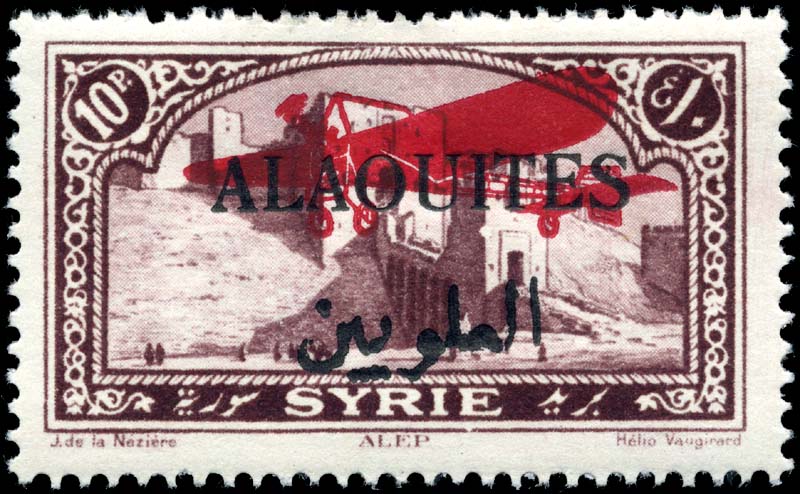

The State of Alawites (french: links=no, État des Alaouites, ar, links=no, دولة العلويين) was located on the Syrian coast and incorporated a majority of

The State of Alawites (french: links=no, État des Alaouites, ar, links=no, دولة العلويين) was located on the Syrian coast and incorporated a majority of

On 1 September 1920, the day after the creation of Greater Lebanon and the Alawite State, Arrêté 330 separated out of the previous "Gouvernement de Damas" ("Government of Damascus") an independent government known as the "Gouvernement d'Alep" ("Government of Aleppo"), including the autonomous sandjak of Alexandretta, which retained its administrative autonomy. The terms "Gouvernement d'Alep" "Gouvernement de Damas" were used interchangeably with "l'État d'Alep" and "l'État de Damas" – for example, Arrete 279 1 October 1920 stated in its preamble: "Vu l'arrêté No 330 du 1er Septembre 1920 créant l'État d'Alep".

The

On 1 September 1920, the day after the creation of Greater Lebanon and the Alawite State, Arrêté 330 separated out of the previous "Gouvernement de Damas" ("Government of Damascus") an independent government known as the "Gouvernement d'Alep" ("Government of Aleppo"), including the autonomous sandjak of Alexandretta, which retained its administrative autonomy. The terms "Gouvernement d'Alep" "Gouvernement de Damas" were used interchangeably with "l'État d'Alep" and "l'État de Damas" – for example, Arrete 279 1 October 1920 stated in its preamble: "Vu l'arrêté No 330 du 1er Septembre 1920 créant l'État d'Alep".

The

Recueil des actes administratifs du Haut-commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban

', Bibliothèque numérique patrimoniale,

Bulletin officiel des actes administratifs du Haut commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban

', Bibliothèque numérique patrimoniale,

The French Mandate in Lebanon

" ''The American Historical Review'', Volume 124, Issue 5, Pages 1689–1693 * Hyam Mallat (2012)

Comprendre la formation des États du Liban et la Syrie a l’aune des boulerversements actuels dans le monde arabe

(in French) * Hourani (1946)

Syria and Lebanon: A Political Essay

page 180 onwards * * * *

Timeline of the French Mandate period

Mandat Syria-Liban ... (1920–1946)

{{DEFAULTSORT:French Mandate of Syria League of Nations mandates 20th century in Lebanon 20th century in Syria History of the Levant Former countries in the Middle East Former colonies in Asia Mandate for Syria Mandate for Syria Former countries of the interwar period Political entities in the Land of Israel Sykes–Picot Agreement States and territories established in 1923 States and territories disestablished in 1946 1946 disestablishments in Asia 1923 establishments in the French colonial empire 1946 disestablishments in the French colonial empire France–Lebanon relations France–Syria relations

partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

, concerning Syria and Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. The mandate system was supposed to differ from colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

, with the governing country intended to act as a trustee until the inhabitants were considered eligible for self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

. At that point, the mandate would terminate and an independent state

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

would be born.

During the two years that followed the end of the war in 1918—and in accordance with the Sykes–Picot Agreement signed by Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

during the war—the British held control of most of Ottoman Mesopotamia (modern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

) and the southern part of Ottoman Syria ( Palestine and Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

), while the French controlled the rest of Ottoman Syria, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

, Alexandretta (Hatay) and portions of southeastern Turkey. In the early 1920s, British and French control of these territories became formalized by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

' mandate system, and on 29 September 1923 France was assigned the League of Nations mandate of Syria, which included the territory of present-day Lebanon and Alexandretta in addition to modern Syria.

The administration of the region under the French was carried out through a number of different governments and territories, including the Syrian Federation

The Syrian Federation ( ar, الاتحاد السوري; french: Fédération syrienne), officially the Federation of the Autonomous States of Syria (french: Fédération des États autonomes de Syrie), was constituted on 28 June 1922 by High Comm ...

(1922–24), the State of Syria (1924–30)

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

and the Syrian Republic (1930–1950), as well as smaller states: the State of Greater Lebanon, the Alawite State

The Alawite State ( ar, دولة جبل العلويين, '; french: État des Alaouites), officially named the Territory of the Alawites (french: territoire des Alaouites), after the locally-dominant Alawites from its inception until its int ...

and Jabal Druze State

Jabal al-Druze ( ar, جبل الدروز, french: Djebel Druze) was an autonomous state in the French Mandate of Syria from 1921 to 1936, designed to function as a government for the local Druze population under French oversight.

Nomenclat ...

. Hatay State

Hatay State ( tr, Hatay Devleti; french: État du Hatay; ar , دولة هاتاي ''Dawlat Hatāy''), also known informally as the Republic of Hatay ( ar , جمهورية هاتاي ''Jumhūriyya Hatāy''), was a transitional political entity t ...

was annexed by Turkey in 1939. The French mandate lasted until 1946, when French troops eventually left Syria and Lebanon, which had both declared independence during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

Background

With the defeat of the Ottomans in Syria, British troops, underGeneral

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir Edmund Allenby, entered Damascus in 1918 accompanied by troops of the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

led by Faisal, son of Sharif Hussein

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ar, الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, al-Ḥusayn bin ‘Alī al-Hāshimī; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after proc ...

of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

. Faisal established the first new postwar Arab government in Damascus in October 1918, and named Ali Rida Pasha ar-Rikabi a military governor.

The new Arab administration formed local governments in the major Syrian cities, and the pan-Arab flag was raised all over Syria. The Arabs hoped, with faith in earlier British promises, that the new Arab state would include all the Arab lands stretching from Aleppo in northern Syria to Aden in southern

The new Arab administration formed local governments in the major Syrian cities, and the pan-Arab flag was raised all over Syria. The Arabs hoped, with faith in earlier British promises, that the new Arab state would include all the Arab lands stretching from Aleppo in northern Syria to Aden in southern Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

.

However, in accordance with the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement between Britain and France, General Allenby assigned to the Arab administration only the interior regions of Syria (the eastern zone). Palestine (the southern zone) was reserved for the British. On 8 October, French troops disembarked in Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

and occupied the Lebanese coastal region south to Naqoura

Naqoura (, ''Enn Nâqoura, Naqoura, An Nāqūrah'') is a small city in southern Lebanon. Since March 23, 1978, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) has been headquartered in Naqoura.

Name

According to E. H. Palmer (1881), the nam ...

(the western zone), replacing British troops there. The French immediately dissolved the local Arab governments in the region.

France demanded full implementation of the Sykes–Picot Agreement, with Syria under its control. On 26 November 1919, British forces withdrew from Damascus to avoid confrontation with the French, leaving the Arab government to face France. Faisal had travelled several times to Europe since November 1918, trying to convince France and Britain to change their positions, but without success. France's determination to intervene in Syria was shown by the naming of General Henri Gouraud as high commissioner in Syria and

France demanded full implementation of the Sykes–Picot Agreement, with Syria under its control. On 26 November 1919, British forces withdrew from Damascus to avoid confrontation with the French, leaving the Arab government to face France. Faisal had travelled several times to Europe since November 1918, trying to convince France and Britain to change their positions, but without success. France's determination to intervene in Syria was shown by the naming of General Henri Gouraud as high commissioner in Syria and Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

. At the Paris Peace Conference, Faisal found himself in an even weaker position when the European powers decided to renege on the promises made to the Arabs.

In May 1919, elections were held for the Syrian National Congress

The Syrian National Congress, also called the Pan-Syrian Congress and General Syrian Congress (GSC), was convened in May 1919 in Damascus, Syria, after the expulsion of the Ottomans from Syria. The mission of the Congress was to consider the futu ...

, which convened in Damascus. 80% of seats went to conservatives. However, the minority included dynamic Arab nationalist figures such as Jamil Mardam Bey

Jamil Mardam Bey ( ota, جميل مردم بك; tr, Cemil Mardam Bey; 1895–1960), was a Syrian politician. He was born in Damascus to a prominent aristocratic family. He is a descendant of the Ottoman general, statesman and Grand Vizier Lala ...

, Shukri al-Kuwatli

Shukri al-Quwatli ( ar, شكري القوّتلي, Shukrī al-Quwwatlī; 6 May 189130 June 1967) was the first president of post-independence Syria. He began his career as a dissident working towards the independence and unity of the Ottoman Em ...

, Ahmad al-Qadri

Ahmed Al-Qadri ( ar, أحمد القادري; 1956 – 3 September 2020) was a Syrian agricultural engineer and politician. He held the position of Minister of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform from February 2013 until August 2020 within the Counc ...

, Ibrahim Hanano

Ibrahim Hananu or Ibrahim Hanano (1869–1935) ( ar, إبراهيم هنانو, Ibrāhīm Hanānū) was an Ottoman municipal official and later a leader of a revolt against the French presence in northern Syria. He was a member of a notable lan ...

, and Riyad as-Solh. The head was moderate nationalist Hashim al-Atassi

Hashim al-Atassi ( ar, هاشم الأتاسي, Hāšim al-ʾAtāsī; 11 January 1875 – 5 December 1960) was a Syrian nationalist and statesman and the President of Syria from 1936 to 1939, 1949 to 1951 and 1954 to 1955.

Background and e ...

.

In June 1919, the American King–Crane Commission arrived in Syria to inquire into local public opinion about the future of the country. The commission's remit extended from Aleppo to Beersheba

Beersheba or Beer Sheva, officially Be'er-Sheva ( he, בְּאֵר שֶׁבַע, ''Bəʾēr Ševaʿ'', ; ar, بئر السبع, Biʾr as-Sabʿ, Well of the Oath or Well of the Seven), is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. ...

. They visited 36 major cities, met with more than 2,000 delegations from more than 300 villages, and received more than 3,000 petitions. Their conclusions confirmed the opposition of Syrians to the mandate in their country as well as to the Balfour Declaration, and their demand for a unified Greater Syria encompassing Palestine. The conclusions of the commission were ignored by both Britain and France.

Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

demonstrations broke out, and Muslim inhabitants in and around Mount Lebanon revolted in fear of being incorporated into a new, mainly Christian, state of Greater Lebanon

The State of Greater Lebanon ( ar, دولة لبنان الكبير, Dawlat Lubnān al-Kabīr; french: État du Grand Liban), informally known as French Lebanon, was a state declared on 1 September 1920, which became the Lebanese Republic ( ar, ...

. A part of France's claim to these territories in the Levant was that France had been acknowledged as a protector of the minority Christian communities by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

In March 1920, the Congress in Damascus adopted a resolution rejecting the Faisal-Clemenceau accords. The congress declared the independence of Syria in her natural borders (including Southern Syria or Palestine), and proclaimed Faisal the king of all Arabs. Faisal invited Ali Rida al-Rikabi to form a government. The congress also proclaimed political and economic union with neighboring Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

and demanded its independence as well.

On 25 April, the supreme inter-Allied council, which was formulating the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, granted France the mandate of Syria (including Lebanon), and granted Britain the Mandate of Palestine (including Jordan), and Iraq. Syrians reacted with violent demonstrations, and a new government headed by Hashim al-Atassi was formed on 7 May 1920. The new government decided to organize general conscription and began forming an army.

These decisions provoked adverse reactions by France as well as by the Maronite patriarchate of Mount Lebanon, which denounced the decisions as a "coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

". In Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, the Christian press expressed its hostility to the decisions of Faisal's government. Lebanese nationalists used the crisis against Faisal's government to convene a council of Christian figures in Baabda

Baabda ( ar, بعبدا) is the capital city of Baabda District as well as the capital of Mount Lebanon Governorate, western Lebanon. Baabda was the capital city of the autonomous Ottoman Mount Lebanon. Baabda is known for the Ottoman Castle (t ...

that proclaimed the independence of Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

on 22 March 1920.

On 14 July 1920, General Gouraud issued an ultimatum to Faisal, giving him the choice between submission or abdication. Realizing that the power balance was not in his favor, Faisal chose to cooperate. However, the young minister of war, Youssef al-Azmeh, refused to comply. In the resulting Franco-Syrian War

The Franco-Syrian War took place during 1920 between the Hashemite rulers of the newly established Arab Kingdom of Syria and France. During a series of engagements, which climaxed in the Battle of Maysalun, French forces defeated the forces of t ...

, Syrian troops under al-Azmeh, composed of the little remaining troops of the Arab army along with Bedouin horsemen and civilian volunteers, met the better trained 12,000-strong French forces under General Mariano Goybet

Mariano Francisco Julio Goybet (17 August 1861 – 29 September 1943) was a French Army general, who held several commands in World War I.

Family

His family is an old family from Savoy in France. Its members were notaries, merchants, mayors, cap ...

at the Battle of Maysaloun

The Battle of Maysalun ( ar, معركة ميسلون), also called the Battle of Maysalun Pass or the Battle of Khan Maysalun (french: Bataille de Khan Mayssaloun), was a four-hour battle fought between the forces of the Arab Kingdom of Syria an ...

. The French won the battle in less than a day and Azmeh died on the battlefield, along with many of the Syrian troops, while the remaining troops possibly defected. General Goybet captured Damascus with little resistance on 24 July 1920, and the mandate was written in London two years later on 24 July 1922.

States created during the French Mandate

Arriving inLebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

, the French were received as liberators by the Christian community, but in the rest of Syria, they were faced with strong resistance.

The mandate region was subdivided into six states. They were the states of Damascus (1920), Aleppo (1920), Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

(1920), Jabal Druze (1921), the autonomous Sanjak of Alexandretta

The Sanjak of Alexandretta ( ar, لواء الإسكندرونة '', '' tr, İskenderun Sancağı, french: Sandjak d'Alexandrette) was a sanjak of the Mandate of Syria composed of two qadaas of the former Aleppo Vilayet ( Alexandretta and Antio ...

(1921, modern-day Hatay

Hatay Province ( tr, Hatay ili, ) is the southernmost province of Turkey. It is situated almost entirely outside Anatolia, along the eastern coast of the Levantine Sea. The province borders Syria to its south and east, the Turkish province of ...

), and the State of Greater Lebanon (1920), which became later the modern country of Lebanon.

The borders of these states were based in part on the sectarian geography in Syria. Many of the different Syrian sects were hostile to the French mandate and to the division it created, as shown by the numerous revolts that the French encountered in all of the Syrian states. The Maronite Christians of Mount Lebanon, on the other hand, were a community with a dream of independence that was being realized under the French; therefore, Greater Lebanon was the exception among the newly formed states.

It took France three years from 1920 to 1923 to gain full control over Syria and to quell all the insurgencies that broke out, notably in the Alawite territories, Mount Druze

Jabal al-Druze ( ar, جبل الدروز, ''jabal ad-durūz'', ''Mountain of the Druze''), officially Jabal al-Arab ( ar, جبل العرب, links=no, ''jabal al-ʿarab'', ''Mountain of the Arabs''), is an elevated volcanic region in the As-Suwa ...

and Aleppo.

Although there were uprisings in the different states, the French deliberately gave different ethnic and religious groups in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

their own lands in the hopes of prolonging their rule. The French hoped to fragment the various groups in the region, to mitigate support for the Syrian nationalist

Syrian nationalism, also known as Pan-Syrian nationalism (or pan-Syrianism), refers to the nationalism of the region of Syria, as a cultural or political entity known as " Greater Syria".

It should not be confused with the Arab nationalism that ...

movement seeking to end colonial rule. The administration of the state governments was heavily dominated by the French. Local authorities were given very little power and did not have the authority to independently decide policy. The small amount of power that local leaders had could easily be overruled by French officials. The French did everything in their power to prevent people in the Levant from developing self-sufficient governing bodies.

State of Greater Lebanon

On 3 August 1920, Arrêté 299 of the ''Haut-commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban'' linked the cazas of Hasbaya, Rachaya, Maallaka and Baalbeck to what was then known as the Autonomous Territory of Lebanon. Then on 31 August 1920, General Gouraud signed Arrêté 318 delimiting the State of Greater Lebanon, with explanatory notes stating that Lebanon would be treated separately from the rest of Syria. On 1 September 1920, General Gouraud publicly proclaimed the creation of the State of Greater Lebanon (french: links=no, État du Grand Liban, ar, links=no, دولة لبنان الكبير) at a ceremony in Beirut. Greater Lebanon was created by France to be a "safe haven" for the Maronite population of the ''

Greater Lebanon was created by France to be a "safe haven" for the Maronite population of the ''mutasarrifia

Mutasarrif or mutesarrif ( ota, متصرّف, tr, mutasarrıf) was the title used in the Ottoman Empire and places like post-Ottoman Iraq for the governor of an administrative district. The Ottoman rank of mutasarrif was established as part of a ...

'' (Ottoman administrative unit) of Mount Lebanon. Mt. Lebanon, an area with a Maronite majority, had enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy during the Ottoman era. However, in addition to the Maronite Mutasarrifia other, mainly Muslim, regions were added, forming "Greater" Lebanon. Those regions correspond today to North Lebanon, south Lebanon

Southern Lebanon () is the area of Lebanon comprising the South Governorate and the Nabatiye Governorate. The two entities were divided from the same province in the early 1990s. The Rashaya and Western Beqaa Districts, the southernmost distric ...

, Biqa' valley

The Beqaa Valley ( ar, links=no, وادي البقاع, ', Lebanese ), also transliterated as Bekaa, Biqâ, and Becaa and known in classical antiquity as Coele-Syria, is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon. It is Lebanon's most important ...

, and Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

. The capital of Greater Lebanon was Beirut. The new state was granted a flag merging the French flag

The national flag of France (french: link=no, drapeau français) is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured blue ( hoist side), white, and red. It is known to English speakers as the ''Tricolour'' (), although the flag of Ireland ...

with the cedar of Lebanon

''Cedrus libani'', the cedar of Lebanon or Lebanese cedar (), is a species of tree in the genus cedrus, a part of the pine family, native to the mountains of the Eastern Mediterranean basin. It is a large evergreen conifer that has great religi ...

.

Maronites were the majority in Lebanon and managed to preserve its independence; an independence that created a unique precedent in the Arab world as Lebanon was the first Arab country in which Christians were not a minority. The State of Greater Lebanon existed until 23 May 1926, after which it became the Lebanese Republic

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

.

Most Muslims in Greater Lebanon rejected the new state upon its creation. Some believe that the continuous Muslim demand for reunification with Syria eventually brought about an armed conflict between Muslims and Christians in 1958 when Lebanese Muslims

Islam in Lebanon has a long and continuous history. According to an estimate by the CIA, it is followed by 67.8% of the country's total population. Sunnis make up 31.9%, Shias make up 31.2%, with smaller percentages of Alawites and Ismailis ...

wanted to join the newly proclaimed United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

, while Lebanese Christians

Christianity in Lebanon has a long and continuous history. Biblical Scriptures purport that Peter and Paul evangelized the Phoenicians, whom they affiliated to the ancient patriarchate of Antioch. The spread of Christianity in Lebanon was ...

were strongly opposed. However, most members of the Lebanese Muslim communities and their political elites were committed to the idea of being Lebanese citizens by the late 1930s, even though they also tended to nurture Arab nationalist sentiments.

State of Alawites

On 19 August 1920, General Gouraud signed Arrêté 314 which added to the autonomous sandjak of Alexandretta the cazas of Jisr el-Choughour, the madriyehs of Baher and Bujack (caza of Latakia), the moudiriyeh of Kinsaba (caza of Sahyoun) "with a view to the formation of the territories of Greater Lebanon and the Ansarieh Mountains"; where the "Ansarieh Mountains" area was to become the Alawite State. On 31 August 1920, the same day that the decree creating Greater Lebanon was signed, General Gouraud signed Arrêté 319 delimiting the State of Alawites, and Arrêté 317 adding the caza of Massyaf (Omranie) into the new State. The State of Alawites (french: links=no, État des Alaouites, ar, links=no, دولة العلويين) was located on the Syrian coast and incorporated a majority of

The State of Alawites (french: links=no, État des Alaouites, ar, links=no, دولة العلويين) was located on the Syrian coast and incorporated a majority of Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

, a branch of Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mo ...

Islam. The port city of Latakia was the capital of this state. Initially it was an autonomous territory under French rule known as the "Alawite Territories". It became part of the Syrian Federation in 1922, but left the federation again in 1924 and became the "State of Alawites". On 22 September 1930, it was renamed the "Independent Government of Latakia". The population at this time was 278,000. The government of Latakia finally joined the Syrian Republic on 5 December 1936. This state witnessed several rebellions against the French, including that of Salih al-Ali (1918–1920).

On 28 June 1922 Arrêté 1459 created a " Federation of the Autonomous States of Syria" which included the State of Aleppo, the State of Damascus and the State of the Alawis. However, two and a half years later on 5 December 1924 Arrêté 2979 and Arrêté 2980 establishing the Alawite State as an independent state with Latakia as its capital, and separately unified the States of Aleppo and Damascus as from 1 January 1925 into a single State, renamed "d'État de Syrie" ("State of Syria").

In 1936, both Jebel Druze and the Alawite State were incorporated into the State of Syria.Arrêté 265/LR of 2 December 1936 and Arrêté 274/LR of 5 December 1936 incorporated Jebel Druze and the Alawite State into Syria. Both used similar wording: "le territoire du Djebel Druze fait partie de l'État de Syrie... ce territoire bénéficie, au sein de l'État de Syrie, d'un régime spécial administratif et financier... sous réserve des dispositions de ce règlement, le territoire du Djebel Druze est régi par la Constitution, les lois et les règlements généraux de la République syrienne... le présent arrêté... entreront en vigueur... dès ratification du traité franco-syrien" [Translate: "The territory of Djebel Druze is part of the State of Syria ... this territory enjoys, within the State of Syria, a special administrative and financial regime ... subject to the provisions of this territory of Djebel Druze is governed by the Constitution, the laws and general regulations of the Syrian Republic ... this Order ... shall enter into force ... upon ratification of the Franco-Syrian Treaty ".]

State of Syria

On 1 September 1920, the day after the creation of Greater Lebanon and the Alawite State, Arrêté 330 separated out of the previous "Gouvernement de Damas" ("Government of Damascus") an independent government known as the "Gouvernement d'Alep" ("Government of Aleppo"), including the autonomous sandjak of Alexandretta, which retained its administrative autonomy. The terms "Gouvernement d'Alep" "Gouvernement de Damas" were used interchangeably with "l'État d'Alep" and "l'État de Damas" – for example, Arrete 279 1 October 1920 stated in its preamble: "Vu l'arrêté No 330 du 1er Septembre 1920 créant l'État d'Alep".

The

On 1 September 1920, the day after the creation of Greater Lebanon and the Alawite State, Arrêté 330 separated out of the previous "Gouvernement de Damas" ("Government of Damascus") an independent government known as the "Gouvernement d'Alep" ("Government of Aleppo"), including the autonomous sandjak of Alexandretta, which retained its administrative autonomy. The terms "Gouvernement d'Alep" "Gouvernement de Damas" were used interchangeably with "l'État d'Alep" and "l'État de Damas" – for example, Arrete 279 1 October 1920 stated in its preamble: "Vu l'arrêté No 330 du 1er Septembre 1920 créant l'État d'Alep".

The State of Aleppo

The State of Aleppo (french: État d'Alep; ar, دولة حلب ') was one of the five states that were established by the French High Commissioner of the Levant, General Henri Gouraud, in the French Mandate of Syria which followed the San Remo ...

(1920–1925, french: links=no, État d'Alep, ar, links=no, دولة حلب) included a majority of Sunni Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

. It covered northern Syria in addition to the entire fertile basin of river Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers''). Originating in Turkey, the Eup ...

of eastern Syria. These regions represented much of the agricultural and mineral wealth of Syria. The autonomous Sanjak of Alexandretta

The Sanjak of Alexandretta ( ar, لواء الإسكندرونة '', '' tr, İskenderun Sancağı, french: Sandjak d'Alexandrette) was a sanjak of the Mandate of Syria composed of two qadaas of the former Aleppo Vilayet ( Alexandretta and Antio ...

was added to the state of Aleppo in 1923. The capital was the northern city of Aleppo, which had large Christian and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

communities in addition to the Sunni Muslims. The state also incorporated minorities of Shiites

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most n ...

and Alawites. Ethnic Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ira ...

and Assyrians inhabited the eastern regions alongside the Arabs. The General Governors of the state were Kamil Pasha al-Qudsi

Kamil Pasha al-Qudsi ( ar, كامل باشا القدسي) ; (1845– 1926) was a Syrian statesman who served as the first Governor General of the State of Aleppo

The State of Aleppo (french: État d'Alep; ar, دولة حلب ') was one of th ...

(1920–1922) Mustafa Bey Barmada

Mustafa Bey Barmada ( ar, مصطفى برمدا; 1883 – April 2, 1953) was a Syrian statesman, politician and judge; served as the Governor General of the State of Aleppo between 1923 and 1924 and headed the Judiciary of Syria between 1930s an ...

(1923) and Mar'i Pasha Al Mallah (1924-1925).

The State of Damascus

The State of Damascus (french: État de Damas; ar, دولة دمشق ') was one of the six states established by the French General Henri Gouraud in the French Mandate of Syria which followed the San Remo conference of 1920 and the defeat of K ...

was a French mandate from 1920 to 1925. The capital was Damascus.

The primarily Sunni population of the states of Aleppo and Damascus were strongly opposed to the division of Syria. This resulted in its quick end in 1925, when France united the states of Aleppo and Damascus into the State of Syria.

Sanjak of Alexandretta

The Sanjak of Alexandretta became an autonomous province of Syria under Article 7 of the French-Turkish treaty of 20 October 1921: "A special administrative regime shall be established for the district of Alexandretta. The Turkish inhabitants of this district shall enjoy facility for their cultural development. The Turkish language shall have official recognition". In 1923, Alexandretta was attached to theState of Aleppo

The State of Aleppo (french: État d'Alep; ar, دولة حلب ') was one of the five states that were established by the French High Commissioner of the Levant, General Henri Gouraud, in the French Mandate of Syria which followed the San Remo ...

, and in 1925 it was directly attached to the French mandate of Syria, still with special administrative status. The sanjak was given autonomy in November 1937 in an arrangement brokered by the League. Under its new statute, the sanjak became 'distinct but not separated' from the French Mandate of Syria on the diplomatic level, linked to both France and Turkey for defence matters.

In 1938, the Turkish military went into the Syrian province and expelled most of its Alawite Arab and Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

inhabitants. Before this, Alawi Arabs and Armenians were the majority of Alexandretta's population.

The allocation of seats in the sanjak assembly was based on the 1938 census held by the French authorities under international supervision. The assembly was appointed in the summer of 1938, and the French-Turkish treaty settling the status of the Sanjak was signed on 4 July 1938.

On 2 September 1938, the assembly proclaimed the Sanjak of Alexandretta as the Hatay State

Hatay State ( tr, Hatay Devleti; french: État du Hatay; ar , دولة هاتاي ''Dawlat Hatāy''), also known informally as the Republic of Hatay ( ar , جمهورية هاتاي ''Jumhūriyya Hatāy''), was a transitional political entity t ...

. The republic lasted for one year under joint French and Turkish military supervision. The name ''Hatay'' itself was proposed by Atatürk and the government was under Turkish control.

In 1939, following a popular referendum, the Hatay State

Hatay State ( tr, Hatay Devleti; french: État du Hatay; ar , دولة هاتاي ''Dawlat Hatāy''), also known informally as the Republic of Hatay ( ar , جمهورية هاتاي ''Jumhūriyya Hatāy''), was a transitional political entity t ...

became a Turkish province.

State of Jabal Druze

On 24 October 1922, Arrêté 1641 established the "" (" Autonomous State of Jabal Druze") It was created for the Druze population of southern Syria. It had a population of some 50,000 and its capital inAs-Suwayda

As-Suwayda ( ar, ٱلسُّوَيْدَاء / ALA-LC romanization: ''as-Suwaydāʾ''), also spelled ''Sweida'' or ''Swaida'', is a mainly Druze city located in southwestern Syria, close to the border with Jordan.

It is the capital of As-Suwayda ...

.

In 1936, both Jebel Druze and the Alawite State were incorporated into the State of Syria.

Demands for autonomy not granted by the French Mandate authorities

Al-Jazira Province

In 1936–1937, there was some autonomist agitation among Assyrians andKurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ira ...

, supported by some Bedouins, in the province of Al-Jazira. Its partisans wanted the French troops to stay in the province in the event of a Syrian independence, as they feared the nationalist Damascus government would replace minority officials by Muslim Arabs from the capital. The French authorities refused to consider any new status of autonomy inside Syria.

Golan Region

InQuneitra

Quneitra (also Al Qunaytirah, Qunaitira, or Kuneitra; ar, ٱلْقُنَيْطِرَة or ٱلْقُنَيطْرَة, ''al-Qunayṭrah'' or ''al-Qunayṭirah'' ) is the largely destroyed and abandoned capital of the Quneitra Governorate in sout ...

and the Golan Region, there was a sizeable Circassian community. For the same reasons as their Assyrian, Kurdish and Bedouin counterparts in Al-Jazira province in 1936–1937, several Circassian leaders wanted a special autonomy status for their region in 1938, as they feared the prospect of living in an independent Syrian republic under a nationalist Arab government hostile towards the minorities. They also wanted the Golan region to become a national homeland for Circassian refugees from the Caucasus. A Circassian battalion served in the French Army of the Levant and had helped it against the Arab nationalist uprisings. As in Al-Jazira Province, the French authorities refused to grant any autonomy status to the Golan Circassians.

Economy

Already in 1921, the French wanted to develop the agricultural sector and over a feasibility study of the ''Union Economique de Syrie'' the North-East Syrian and theAlawite State

The Alawite State ( ar, دولة جبل العلويين, '; french: État des Alaouites), officially named the Territory of the Alawites (french: territoire des Alaouites), after the locally-dominant Alawites from its inception until its int ...

were deemed profitable for the cotton cultivation. Investments began in 1924, but it took until the 1930s to produce more than the level reached in 1925.Khoury, Philip Shukry (1987),p.51 By 1933, Palestine was the largest importer of Syrian goods, while French held a share of 7.5% of the imports.Khoury, Philip Shukry (1987),p.48 Between the two World Wars, France became the largest trader of goods of the French Mandate. From 1933 onwards, Japan was also a large source for imports.

Kingdom of Syria (1918-1920)

Heads of Government

King

French Mandate of Syria (1920-1939)

Acting Heads of State

President

Heads of State

Presidents

High Commissioners

* 26 Nov 1919 – 23 Nov 1922: Henri Gouraud * 23 Nov 1922 – 17 Apr 1923: Robert de Caix (acting) * 19 Apr 1923 – 29 Nov 1924:Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

* 29 Nov 1924 – 23 Dec 1925: Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated th ...

* 23 Dec 1925 – 23 Jun 1926: Henry de Jouvenel

Henry de Jouvenel des Ursins (5 April 1876 – 5 October 1935) was a French journalist and statesman.

* Aug 1926 – 16 Jul 1933: Auguste Henri Ponsot

Auguste Henri Ponsot (2 March 1877 – 5 October 1963) was a French politician and statesman.

Life

Auguste Henri was born in Bologna, Italy. After law studies at the University of Dijon, Ponsot entered the diplomatic career in 1903. After having ...

* 16 Jul 1933 – Jan 1939: Damien de Martel

Count Damien de Martel was a French politician and diplomat, who was born on November 27, 1878 and died on January 21, 1940. He was a minister plenipotentiary in China, then in Latvia, Japan and the sixth High Commissioner of the Levant in Syria ...

* Jan 1939 – Nov 1940: Gabriel Puaux

Gabriel Puaux (May 19, 1883 in Paris – January 1, 1970 in Kitzbühel, Austria) was a French diplomat and politician.

Biography

Puaux, son of the Protestant pastor Frank Puaux, earned a bachelor's degree in addition to his postgraduate educ ...

* 24 Nov 1940 – 27 Nov 1940: Jean Chiappe

Jean Baptiste Pascal Eugène Chiappe (3 May 1878 – 27 November 1940) was a high-ranking French civil servant.

Chiappe was director of the ''Sûreté générale'' in the 1920s. He was subsequently given the post of Préfet de police in the 19 ...

(died on flight to take office)

* 6 Dec 1940 – 16 Jun 1941: Henri Dentz

* 24 Jun 1941 – 7 Jun 1943: Georges Catroux

Georges Albert Julien Catroux (29 January 1877 – 21 December 1969) was a French Army general and diplomat who served in both World War I and World War II, and served as Grand Chancellor of the Légion d'honneur from 1954 to 1969.

Life

Cat ...

* 7 Jun 1943 – 23 Nov 1943: Jean Helleu

* 23 Nov 1943 – 23 Jan 1944: Yves Chataigneau

* 23 Jan 1944 – 1 Sep 1946: Étienne Paul-Émile-Marie Beynet

See also

* French colonial empire *French colonial flags

Some of the colonies, protectorates and mandates of the French Colonial Empire used distinctive colonial flags. These most commonly had a French Tricolour in the canton.

As well as the flags of individual colonies, the governors-general of F ...

* French Lebanese

French people in Lebanon (or French Lebanese) are French citizens resident in Lebanon, including many binationals and persons of mixed ancestry. French statistics estimated that there were around 21,500 French citizens living in Lebanon in 2011. ...

* List of French possessions and colonies

From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over , the second largest empire in the world at the time behind only the Spanish Empire. During the 19th and 20th centuri ...

* Modern history of Syria

Notes

Further reading

Primary sources

* Haut-commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban,Recueil des actes administratifs du Haut-commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban

', Bibliothèque numérique patrimoniale,

Aix-Marseille University

Aix-Marseille University (AMU; french: Aix-Marseille Université; formally incorporated as ''Université d'Aix-Marseille'') is a public research university located in the Provence region of southern France. It was founded in 1409 when Louis II o ...

* Haut-commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban, Bulletin officiel des actes administratifs du Haut commissariat de la République française en Syrie et au Liban

', Bibliothèque numérique patrimoniale,

Aix-Marseille University

Aix-Marseille University (AMU; french: Aix-Marseille Université; formally incorporated as ''Université d'Aix-Marseille'') is a public research university located in the Provence region of southern France. It was founded in 1409 when Louis II o ...

Secondary sources

* Hakim, Carol. 2019.The French Mandate in Lebanon

" ''The American Historical Review'', Volume 124, Issue 5, Pages 1689–1693 * Hyam Mallat (2012)

Comprendre la formation des États du Liban et la Syrie a l’aune des boulerversements actuels dans le monde arabe

(in French) * Hourani (1946)

Syria and Lebanon: A Political Essay

page 180 onwards * * * *

External links

Timeline of the French Mandate period

Mandat Syria-Liban ... (1920–1946)

{{DEFAULTSORT:French Mandate of Syria League of Nations mandates 20th century in Lebanon 20th century in Syria History of the Levant Former countries in the Middle East Former colonies in Asia Mandate for Syria Mandate for Syria Former countries of the interwar period Political entities in the Land of Israel Sykes–Picot Agreement States and territories established in 1923 States and territories disestablished in 1946 1946 disestablishments in Asia 1923 establishments in the French colonial empire 1946 disestablishments in the French colonial empire France–Lebanon relations France–Syria relations