History

The Americas

As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlement along the South American coast in what is today

As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlement along the South American coast in what is today Africa and Asia

French colonial expansion was not limited to the New World.

With the end of the French Wars of Religion, King Henry IV encouraged various enterprises, set up to develop trade with faraway lands. In December 1600, a company was formed through the association of Saint-Malo,

French colonial expansion was not limited to the New World.

With the end of the French Wars of Religion, King Henry IV encouraged various enterprises, set up to develop trade with faraway lands. In December 1600, a company was formed through the association of Saint-Malo, /ref> Two ships, the ''Croissant'' and the ''Corbin'', were sent around the Cape of Good Hope in May 1601. One was wrecked in the Maldives, leading to the adventure of François Pyrard de Laval, who managed to return to France in 1611. The second ship, carrying

Colonial conflict with Britain

In the middle of the 18th century, a series of colonial conflicts began between France and Britain, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of most of the first French colonial empire and the near-complete expulsion of France from the Americas. These wars were the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), the

In the middle of the 18th century, a series of colonial conflicts began between France and Britain, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of most of the first French colonial empire and the near-complete expulsion of France from the Americas. These wars were the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), the Second French colonial empire (after 1830)

At the close of the Napoleonic Wars, most of France's colonies were restored to it by Britain, notably

At the close of the Napoleonic Wars, most of France's colonies were restored to it by Britain, notably Franco-Tahitian War (1842–1847)

In 1838, the French naval commander Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars responded to complaints of the mistreatment of French Catholic missionary in the Kingdom of Tahiti ruled by Queen Pōmare IV. Dupetit Thouars forced the native government to pay an indemnity and sign a treaty of friendship with France respecting the rights of French subjects in the islands including any future Catholic missionaries. Four years later, claiming the Tahitians had violated the treaty, a French protectorate was forcibly installed and the queen made to sign a request for French protection.

Queen Pōmare left her kingdom and exiled herself to Raiatea in protest against the French and tried to enlist the help of Queen Victoria. The Franco-Tahitian War broke out between the Tahitians, Tahitian people and the French from 1844 to 1847 as France attempted to consolidate their rule and extend their rule into the Leeward Islands (Society Islands), Leeward Islands where Queen Pōmare sought refuge with her relatives. The British remained officially neutral during the war but diplomatic tensions existed between the French and British. The French succeeded in subduing the guerilla forces on Tahiti but failed to hold the other islands. In February 1847, Queen Pōmare IV returned from her self-imposed exile and acquiesced to rule under the protectorate. Although victorious, the French were not able to annex the islands due to diplomatic pressure from Great Britain, so Tahiti and its dependency Moorea continued to be ruled under the protectorate. A clause to the war settlement, known as the Jarnac Convention or the Anglo-French Convention of 1847, was signed by France and Great Britain, in which the two powers agreed to respect the independence of Queen Pōmare's allies in Leeward Islands. The French continued the guise of protection until the 1880s when they formally annexed Tahiti with the abdication of King Pōmare V on 29 June 1880. The Leeward Islands were annexation of the Leeward Islands, annexed through the Leewards War which ended in 1897. These conflicts and the annexation of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia, French Oceania.

In 1838, the French naval commander Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars responded to complaints of the mistreatment of French Catholic missionary in the Kingdom of Tahiti ruled by Queen Pōmare IV. Dupetit Thouars forced the native government to pay an indemnity and sign a treaty of friendship with France respecting the rights of French subjects in the islands including any future Catholic missionaries. Four years later, claiming the Tahitians had violated the treaty, a French protectorate was forcibly installed and the queen made to sign a request for French protection.

Queen Pōmare left her kingdom and exiled herself to Raiatea in protest against the French and tried to enlist the help of Queen Victoria. The Franco-Tahitian War broke out between the Tahitians, Tahitian people and the French from 1844 to 1847 as France attempted to consolidate their rule and extend their rule into the Leeward Islands (Society Islands), Leeward Islands where Queen Pōmare sought refuge with her relatives. The British remained officially neutral during the war but diplomatic tensions existed between the French and British. The French succeeded in subduing the guerilla forces on Tahiti but failed to hold the other islands. In February 1847, Queen Pōmare IV returned from her self-imposed exile and acquiesced to rule under the protectorate. Although victorious, the French were not able to annex the islands due to diplomatic pressure from Great Britain, so Tahiti and its dependency Moorea continued to be ruled under the protectorate. A clause to the war settlement, known as the Jarnac Convention or the Anglo-French Convention of 1847, was signed by France and Great Britain, in which the two powers agreed to respect the independence of Queen Pōmare's allies in Leeward Islands. The French continued the guise of protection until the 1880s when they formally annexed Tahiti with the abdication of King Pōmare V on 29 June 1880. The Leeward Islands were annexation of the Leeward Islands, annexed through the Leewards War which ended in 1897. These conflicts and the annexation of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia, French Oceania.

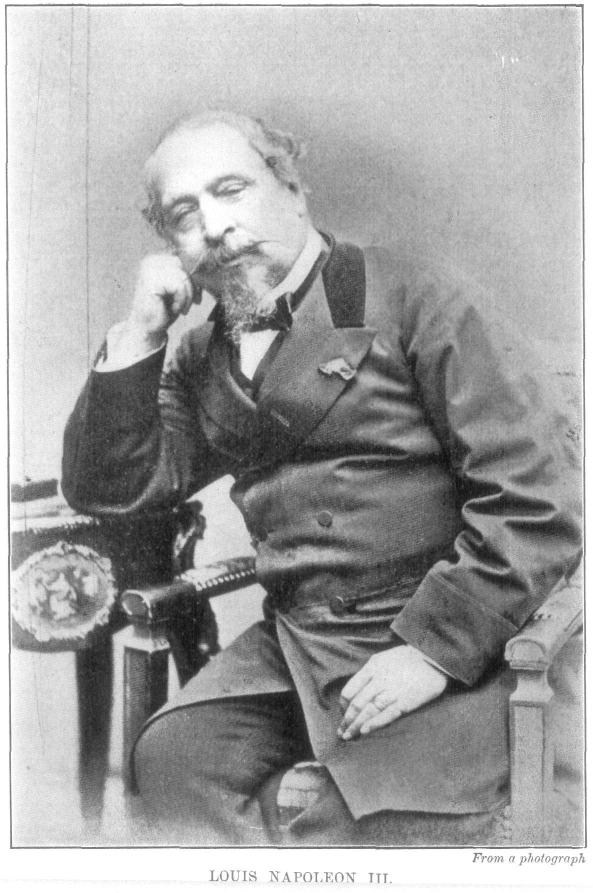

Napoleon III: 1852–1870

Napoleon III doubled the area of the French overseas Empire; he established French rule in New Caledonia, and Cochinchina, established a protectorate in Cambodia (1863); and colonized parts of Africa.

To carry out his new overseas projects, Napoleon III created a new Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies and appointed an energetic minister, Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat, Prosper, Marquis of Chasseloup-Laubat, to head it. A key part of the enterprise was the modernization of the French Navy; he began the construction of 15 powerful new battle cruisers powered by steam and driven by propellers; and a fleet of steam-powered troop transports. The French Navy became the second most powerful in the world, after Britain's. He also created a new force of colonial troops, including elite units of naval infantry, Zouaves, the Chasseurs d'Afrique, and Algerian sharpshooters, and he expanded the Foreign Legion, which had been founded in 1831 and won fame in the Crimea, Italy and Mexico. By the end of Napoleon III's reign, the French overseas territories had tripled in the area; in 1870 they covered a , with more than 5 million inhabitants.

Napoleon III doubled the area of the French overseas Empire; he established French rule in New Caledonia, and Cochinchina, established a protectorate in Cambodia (1863); and colonized parts of Africa.

To carry out his new overseas projects, Napoleon III created a new Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies and appointed an energetic minister, Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat, Prosper, Marquis of Chasseloup-Laubat, to head it. A key part of the enterprise was the modernization of the French Navy; he began the construction of 15 powerful new battle cruisers powered by steam and driven by propellers; and a fleet of steam-powered troop transports. The French Navy became the second most powerful in the world, after Britain's. He also created a new force of colonial troops, including elite units of naval infantry, Zouaves, the Chasseurs d'Afrique, and Algerian sharpshooters, and he expanded the Foreign Legion, which had been founded in 1831 and won fame in the Crimea, Italy and Mexico. By the end of Napoleon III's reign, the French overseas territories had tripled in the area; in 1870 they covered a , with more than 5 million inhabitants.

New Caledonia becomes a French possession (1853–54)

On 24 September 1853, Admiral Auguste Febvrier Despointes, Febvrier Despointes took formal possession of New Caledonia and Port-de-France (Nouméa) was founded 25 June 1854. A few dozen free settlers settled on the west coast in the following years, but New Caledonia became a penal colony and, from the 1860s until the end of the transportations in 1897, about 22,000 criminals and political prisoners were sent to New Caledonia.Colonization of Senegal (1854–1865)

At the beginning of Napoleon III's reign, the presence of France in French Senegal, Senegal was limited to a trading post on the island of Gorée, a narrow strip on the coast, the town of Saint-Louis, Senegal, Saint-Louis, and a handful of trading posts in the interior. The economy had largely been based on the Slavery in Africa, slave trade, carried out by the rulers of the small kingdoms of the interior, until France abolition of slavery, abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848. In 1854, Napoleon III named an enterprising French Army, French officer, Louis Faidherbe, to govern and expand the colony, and to give it the beginning of a modern economy. Faidherbe built a series of forts along the Senegal River, formed alliances with leaders in the interior, and sent expeditions against those who resisted French rule. He built a new port at Dakar, established and protected telegraph lines and roads, followed these with a Dakar-Saint-Louis railway, rail line between Dakar and Saint-Louis and Dakar–Niger Railway, another into the interior. He built schools, bridges, and systems to supply fresh water to the towns. He also introduced the large-scale cultivation of Bambara groundnuts and peanuts as a commercial crop. Reaching into the Niger River, Niger valley, Senegal became the primary French base in French West Africa, West Africa and a model colony. Dakar became one of the most important cities of the French Empire and of Africa.

At the beginning of Napoleon III's reign, the presence of France in French Senegal, Senegal was limited to a trading post on the island of Gorée, a narrow strip on the coast, the town of Saint-Louis, Senegal, Saint-Louis, and a handful of trading posts in the interior. The economy had largely been based on the Slavery in Africa, slave trade, carried out by the rulers of the small kingdoms of the interior, until France abolition of slavery, abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848. In 1854, Napoleon III named an enterprising French Army, French officer, Louis Faidherbe, to govern and expand the colony, and to give it the beginning of a modern economy. Faidherbe built a series of forts along the Senegal River, formed alliances with leaders in the interior, and sent expeditions against those who resisted French rule. He built a new port at Dakar, established and protected telegraph lines and roads, followed these with a Dakar-Saint-Louis railway, rail line between Dakar and Saint-Louis and Dakar–Niger Railway, another into the interior. He built schools, bridges, and systems to supply fresh water to the towns. He also introduced the large-scale cultivation of Bambara groundnuts and peanuts as a commercial crop. Reaching into the Niger River, Niger valley, Senegal became the primary French base in French West Africa, West Africa and a model colony. Dakar became one of the most important cities of the French Empire and of Africa.

France in Indochina and the Pacific (1858–1870)

Napoleon III also acted to increase the French presence in Indochina. An important factor in his decision was the belief that France risked becoming a second-rate power by not expanding its influence in East Asia. Deeper down was the sense that France owed the world a civilizing mission. French missionaries had been active in Vietnam since the 17th century, when the Jesuit priest Alexandre de Rhodes opened a mission there. In 1858 the Vietnamese emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty felt threatened by the French influence and tried to expel the missionaries. Napoleon III sent a naval force of fourteen gunships, carrying three thousand French and three thousand Filipino troops provided by Spain, under Charles Rigault de Genouilly, to compel the government to accept the missionaries and to stop the persecution of Catholics. In September 1858 the expeditionary force captured and occupied the port of Da Nang, and then in February 1859 moved south and captured Saigon. The Vietnamese ruler was compelled to cede three provinces to France, and to offer protection to the Catholics. The French troops departed for a time to take part in the expedition to China, but in 1862, when the agreements were not fully followed by the Vietnamese emperor, they returned. The Emperor was forced to open treaty ports in Annam (French protectorate), Annam and Tonkin, and all of Cochinchina became a French territory in 1864. In 1863, the ruler of Cambodia, King Norodom, who had been placed in power by the government of Thailand, rebelled against his sponsors and sought the protection of France. The Thai king granted authority over Cambodia to France, in exchange for two provinces of Laos, which were ceded by Cambodia to Thailand. In 1867, Cambodia formally became a protectorate of France.Intervention in Syria and Lebanon (1860–1861)

In the spring of 1860, a war broke out in Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire, between the quasi-Muslim Druze population and the Maronite Christians. The Ottoman authorities in Lebanon could not stop the violence, and it spread into neighboring Syria, with the massacre of many Christians. In Damascus, the Emir Abd-el-Kadr protected the Christians there against the Muslim rioters. Napoleon III felt obliged to intervene on behalf of the Christians, despite the opposition of London, which feared it would lead to a wider French presence in the Middle East. After long and difficult negotiations to obtain the approval of the British government, Napoleon III sent a French contingent of seven thousand men for a period of six months. The troops arrived in Beirut in August 1860, and took positions in the mountains between the Christian and Muslim communities. Napoleon III organized an international conference in Paris, where the country was placed under the rule of a Christian governor named by the Ottoman Sultan, which restored a fragile peace. The French troops departed in June 1861, after just under one year. The French intervention alarmed the British, but was highly popular with the powerful History of the Catholic Church in France#Vocation for the care of the poor in the Industrial Revolution, Catholic political faction in France, which had been alarmed by Napoleon III#Prince-President (1848–1851), Louis Napoleon's dispute with the Pope over his territories in Italy.

In the spring of 1860, a war broke out in Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire, between the quasi-Muslim Druze population and the Maronite Christians. The Ottoman authorities in Lebanon could not stop the violence, and it spread into neighboring Syria, with the massacre of many Christians. In Damascus, the Emir Abd-el-Kadr protected the Christians there against the Muslim rioters. Napoleon III felt obliged to intervene on behalf of the Christians, despite the opposition of London, which feared it would lead to a wider French presence in the Middle East. After long and difficult negotiations to obtain the approval of the British government, Napoleon III sent a French contingent of seven thousand men for a period of six months. The troops arrived in Beirut in August 1860, and took positions in the mountains between the Christian and Muslim communities. Napoleon III organized an international conference in Paris, where the country was placed under the rule of a Christian governor named by the Ottoman Sultan, which restored a fragile peace. The French troops departed in June 1861, after just under one year. The French intervention alarmed the British, but was highly popular with the powerful History of the Catholic Church in France#Vocation for the care of the poor in the Industrial Revolution, Catholic political faction in France, which had been alarmed by Napoleon III#Prince-President (1848–1851), Louis Napoleon's dispute with the Pope over his territories in Italy.

Algeria

Algeria had been formally under French rule since 1830, but only in 1852 was the country entirely conquered. There were about 100,000 European settlers in the country, at that time, about half of them French. Under the Second Republic the country was ruled by a civilian government, but Louis Napoleon re-established a military government, much to the annoyance of the colonists. By 1857 the army had conquered Kabyle Province, and pacified the country. By 1860 the European population had grown to 200,000, and lands of native Algerians were being rapidly bought and farmed by the new arrivals.

Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Algerians, out of a total of 3 million, were killed within the first three decades of the conquest as a result of war, massacres, disease and famine. French losses from 1830 to 1851 were 3,336 killed in action and 92,329 dead in the hospital.

In the first eight years of his rule Napoleon III paid little attention to Algeria. In September 1860, however, he and the Empress Eugénie visited Algeria, and the trip made a deep impression upon them. Eugénie was invited to attend a traditional Arab wedding, and the Emperor met many of the local leaders. The Emperor gradually conceived the idea that Algeria should be governed differently from other colonies. In February 1863, he wrote a public letter to Pelissier, the Military Governor, saying: "Algeria is not a colony in the traditional sense, but an Arab kingdom; the local people have, like the colonists, a legal right to my protection. I am just as much the Emperor of the Arabs of Algeria as I am of the French." He intended to rule Algeria through a government of Arab aristocrats. Toward this end he invited the chiefs of main Algerian tribal groups to his chateau at Compiegne for hunting and festivities.

Compared to previous administrations, Napoleon III was far more sympathetic to the native Algerians. He halted European migration inland, restricting them to the coastal zone. He also freed the Algerian rebel leader Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri, Abd al Qadir (who had been promised freedom on surrender but was imprisoned by the previous administration) and gave him a stipend of 150,000 francs. He allowed Muslims to serve in the military and civil service on theoretically equal terms and allowed them to migrate to France. In addition, he gave the option of citizenship; however, for Muslims to take this option they had to accept all of the French civil code, including parts governing inheritance and marriage which conflicted with Muslim laws, and they had to reject the competence of religious Sharia courts. This was interpreted by some Muslims as requiring them to give up parts of their religion to obtain citizenship and was resented.

More importantly, Napoleon III changed the system of land tenure. While ostensibly well-intentioned, in effect this move destroyed the traditional system of land management and deprived many Algerians of land. While Napoleon did renounce state claims to tribal lands, he also began a process of dismantling tribal land ownership in favour of individual land ownership. This process was corrupted by French officials sympathetic to the French in Algeria who took much of the land they surveyed into public domain. In addition, many tribal leaders, chosen for loyalty to the French rather than influence in their tribe, immediately sold communal land for cash.

His attempted reforms were interrupted in 1864 by an Arab insurrection, which required more than a year and an army of 85,000 soldiers to suppress. Nonetheless, he did not give up his idea of making Algeria a model where French colonists and Arabs could live and work together as equals. He traveled to Algiers for a second time on 3 May 1865, and this time he remained for a month, meeting with tribal leaders and local officials. He offered a wide amnesty to participants of the insurrection, and promised to name Arabs to high positions in his government. He also promised a large public works program of new ports, railroads, and roads. However, once again his plans met a major natural obstacle in 1866 and 1867, Algeria was struck by an epidemic of cholera, clouds of locusts, drought and famine, and his reforms were hindered by the French colonists, who voted massively against him in the plebiscites of his late reign.

Algeria had been formally under French rule since 1830, but only in 1852 was the country entirely conquered. There were about 100,000 European settlers in the country, at that time, about half of them French. Under the Second Republic the country was ruled by a civilian government, but Louis Napoleon re-established a military government, much to the annoyance of the colonists. By 1857 the army had conquered Kabyle Province, and pacified the country. By 1860 the European population had grown to 200,000, and lands of native Algerians were being rapidly bought and farmed by the new arrivals.

Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Algerians, out of a total of 3 million, were killed within the first three decades of the conquest as a result of war, massacres, disease and famine. French losses from 1830 to 1851 were 3,336 killed in action and 92,329 dead in the hospital.

In the first eight years of his rule Napoleon III paid little attention to Algeria. In September 1860, however, he and the Empress Eugénie visited Algeria, and the trip made a deep impression upon them. Eugénie was invited to attend a traditional Arab wedding, and the Emperor met many of the local leaders. The Emperor gradually conceived the idea that Algeria should be governed differently from other colonies. In February 1863, he wrote a public letter to Pelissier, the Military Governor, saying: "Algeria is not a colony in the traditional sense, but an Arab kingdom; the local people have, like the colonists, a legal right to my protection. I am just as much the Emperor of the Arabs of Algeria as I am of the French." He intended to rule Algeria through a government of Arab aristocrats. Toward this end he invited the chiefs of main Algerian tribal groups to his chateau at Compiegne for hunting and festivities.

Compared to previous administrations, Napoleon III was far more sympathetic to the native Algerians. He halted European migration inland, restricting them to the coastal zone. He also freed the Algerian rebel leader Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza'iri, Abd al Qadir (who had been promised freedom on surrender but was imprisoned by the previous administration) and gave him a stipend of 150,000 francs. He allowed Muslims to serve in the military and civil service on theoretically equal terms and allowed them to migrate to France. In addition, he gave the option of citizenship; however, for Muslims to take this option they had to accept all of the French civil code, including parts governing inheritance and marriage which conflicted with Muslim laws, and they had to reject the competence of religious Sharia courts. This was interpreted by some Muslims as requiring them to give up parts of their religion to obtain citizenship and was resented.

More importantly, Napoleon III changed the system of land tenure. While ostensibly well-intentioned, in effect this move destroyed the traditional system of land management and deprived many Algerians of land. While Napoleon did renounce state claims to tribal lands, he also began a process of dismantling tribal land ownership in favour of individual land ownership. This process was corrupted by French officials sympathetic to the French in Algeria who took much of the land they surveyed into public domain. In addition, many tribal leaders, chosen for loyalty to the French rather than influence in their tribe, immediately sold communal land for cash.

His attempted reforms were interrupted in 1864 by an Arab insurrection, which required more than a year and an army of 85,000 soldiers to suppress. Nonetheless, he did not give up his idea of making Algeria a model where French colonists and Arabs could live and work together as equals. He traveled to Algiers for a second time on 3 May 1865, and this time he remained for a month, meeting with tribal leaders and local officials. He offered a wide amnesty to participants of the insurrection, and promised to name Arabs to high positions in his government. He also promised a large public works program of new ports, railroads, and roads. However, once again his plans met a major natural obstacle in 1866 and 1867, Algeria was struck by an epidemic of cholera, clouds of locusts, drought and famine, and his reforms were hindered by the French colonists, who voted massively against him in the plebiscites of his late reign.

French–British relations

Despite the signing of the 1860 Cobden–Chevalier Treaty, a historic free trade agreement between Britain and France, and the joint operations conducted by France and Britain in the Crimea, China and Mexico, diplomatic relations between Britain and France never became close during the colonial era. Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, Lord Palmerston, the British foreign minister from 1846 to 1851 and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister from 1855 to 1865, sought to maintain the balance of power in Europe; this rarely involved an alignment with France. In 1859 there were even briefly fears that France might try to invade Britain. Palmerston was suspicious of France's interventions in Lebanon, Southeast Asia and Mexico. Palmerston was also concerned that France might intervene in the American Civil War (1861–65) on the side of the South. The British also felt threatened by the construction of the Suez Canal (1859–1869) by Ferdinand de Lesseps in Egypt. They tried to oppose its completion by diplomatic pressures and by promoting revolts among workers. The Suez Canal was successfully built by the French, but became a joint British-French project in 1875. Both nations saw it as vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia. In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. France's leading expansionist Jules Ferry was out of office, and Paris allowed London to take effective control of Egypt.1870–1939

After the downfall of Napoleon III, few writers used the word 'empire', which had become associated with despotism, decadence, and weakness, preferring the word 'colonies'. However by the 1880s and 1890s, as Republicans consolidated their control over the political system, increasing numbers of politicians, intellectuals and writers began using the phrase "colonial empire", linking it to republicanism and the French nation. Most Frenchmen ignored foreign affairs and colonial issues. In 1914 the chief pressure group was the ''Parti colonial'', a coalition of 50 organizations with a combined total of only 5,000 members.Asia

It was only after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 and the founding of the French Third Republic, Third Republic (1871–1940) that most of France's later colonial possessions were acquired. From their base in Cochinchina, the French took over Tonkin (in modern northern Vietnam) and Annam (French protectorate), Annam (in modern central Vietnam) in 1884–1885. These, together with Cambodia and Cochinchina, formed French Indochina in 1887 (to which Laos was Franco-Siamese War, added in 1893 and Guangzhouwanin 1900).

In 1849, the Shanghai French Concession, French Concession in Shanghai was established, and in 1860, the Concessions in Tianjin, French Concession in Tientsin (now called Tianjin) was set up. Both concessions lasted until 1946. The French also had smaller concession (territory), concessions in Guangzhou and Hankou (now part of Wuhan).

The Third Anglo-Burmese War, in which Britain conquered and annexed the hitherto independent Upper Burma, was in part motivated by British apprehension at France advancing and gaining possession of territories near to Burma.

It was only after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 and the founding of the French Third Republic, Third Republic (1871–1940) that most of France's later colonial possessions were acquired. From their base in Cochinchina, the French took over Tonkin (in modern northern Vietnam) and Annam (French protectorate), Annam (in modern central Vietnam) in 1884–1885. These, together with Cambodia and Cochinchina, formed French Indochina in 1887 (to which Laos was Franco-Siamese War, added in 1893 and Guangzhouwanin 1900).

In 1849, the Shanghai French Concession, French Concession in Shanghai was established, and in 1860, the Concessions in Tianjin, French Concession in Tientsin (now called Tianjin) was set up. Both concessions lasted until 1946. The French also had smaller concession (territory), concessions in Guangzhou and Hankou (now part of Wuhan).

The Third Anglo-Burmese War, in which Britain conquered and annexed the hitherto independent Upper Burma, was in part motivated by British apprehension at France advancing and gaining possession of territories near to Burma.

Africa

France also extended its influence in North Africa after 1870, establishing a protectorate in Tunisia in 1881 with the Bardo Treaty. Gradually, French control crystallised over much of North, West Africa, West, and Central Africa by around the start of the 20th century (including the modern states of Mauritania,Pacific islands

At this time, the French also established colonies in the South Pacific Ocean, South Pacific, including New Caledonia, the various island groups which make up French Polynesia (including the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Gambier Islands, the Austral Islands and the Tuamotus), and established joint control of the New Hebrides with Britain.=Leeward Islands (1880–1897)

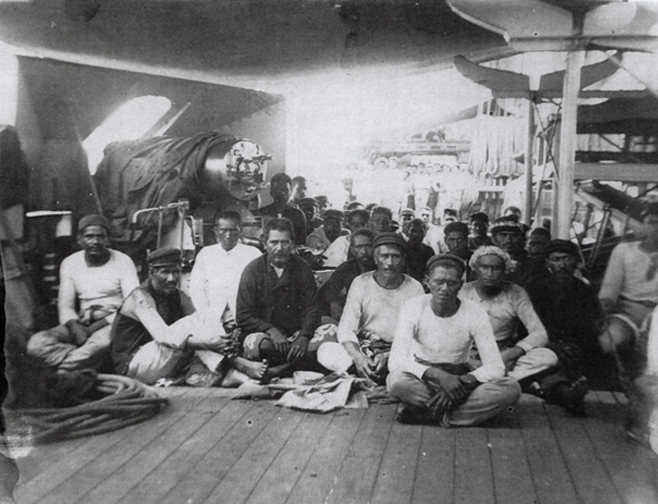

= In contravention of the Jarnac Convention of 1847, the French placed the Leeward Islands under a provisional protectorate by falsely convincing the ruling chiefs that the German Empire planned to take over their island kingdoms. After years of diplomatic negotiation, Britain and France agreed to abrogate the convention in 1887 and the French formally annexed all the Leeward Islands without official treaties of cession from the islands' sovereign governments. From 1888 to 1897, the natives of the kingdom of Raiatea and Tahaa led by a minor chief, Teraupo'o, fought off French rule and the annexation of the Leeward Islands. Anti-French factions in the kingdom of Huahine also attempted to fight off the French under Queen Teuhe while the kingdom of Bora Bora remained neutral but hostile to the French. The conflict ended in 1897 with the capture and exile of rebel leaders to New Caledonia and more than one hundred rebels to the Marquesas. These conflicts and the annexation of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia.

In contravention of the Jarnac Convention of 1847, the French placed the Leeward Islands under a provisional protectorate by falsely convincing the ruling chiefs that the German Empire planned to take over their island kingdoms. After years of diplomatic negotiation, Britain and France agreed to abrogate the convention in 1887 and the French formally annexed all the Leeward Islands without official treaties of cession from the islands' sovereign governments. From 1888 to 1897, the natives of the kingdom of Raiatea and Tahaa led by a minor chief, Teraupo'o, fought off French rule and the annexation of the Leeward Islands. Anti-French factions in the kingdom of Huahine also attempted to fight off the French under Queen Teuhe while the kingdom of Bora Bora remained neutral but hostile to the French. The conflict ended in 1897 with the capture and exile of rebel leaders to New Caledonia and more than one hundred rebels to the Marquesas. These conflicts and the annexation of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia.

Final gains

The French made their last major colonial gains after World War I, when they gained Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, mandates over the former territories of the Ottoman Empire that make up what is now Syria and Lebanon, as well as most of the former German colonies of Togo and Cameroon.Civilising mission

A hallmark of the French colonial project in the late 19th century and early 20th century was the civilising mission (''mission civilisatrice''), the principle that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples. As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies, most notably French West Africa and French Madagascar, Madagascar. During the 19th century, French citizenship along with the right to elect a deputy to the French Chamber of Deputies was granted to the four old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyanne and Réunion as well as to the residents of the "Four Communes" in Senegal. In most cases, the elected deputies were white Frenchmen, although there were some blacks, such as the Senegalese Blaise Diagne, who was elected in 1914.Segalla, Spencer. 2009, ''The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912–1956''. Nebraska University Press

Elsewhere, in the largest and most populous colonies, a Code Noir, strict separation between "sujets français" (all the natives) and "citoyens français" (all males of European extraction) with different rights and duties was maintained until 1946. As was pointed out in a 1927 treatise on French colonial law, the granting of French citizenship to natives "was not a right, but rather a privilege". Two 1912 decrees dealing with French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa enumerated the conditions that a native had to meet in order to be granted French citizenship (they included speaking and writing French, earning a decent living and displaying good moral standards). From 1830 to 1946, only between 3,000 and 6,000 native Algerians were granted French citizenship. In French West Africa, outside of the Four Communes, there were 2,500 "citoyens indigènes" out of a total population of 15 million.

A hallmark of the French colonial project in the late 19th century and early 20th century was the civilising mission (''mission civilisatrice''), the principle that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples. As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies, most notably French West Africa and French Madagascar, Madagascar. During the 19th century, French citizenship along with the right to elect a deputy to the French Chamber of Deputies was granted to the four old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyanne and Réunion as well as to the residents of the "Four Communes" in Senegal. In most cases, the elected deputies were white Frenchmen, although there were some blacks, such as the Senegalese Blaise Diagne, who was elected in 1914.Segalla, Spencer. 2009, ''The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912–1956''. Nebraska University Press

Elsewhere, in the largest and most populous colonies, a Code Noir, strict separation between "sujets français" (all the natives) and "citoyens français" (all males of European extraction) with different rights and duties was maintained until 1946. As was pointed out in a 1927 treatise on French colonial law, the granting of French citizenship to natives "was not a right, but rather a privilege". Two 1912 decrees dealing with French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa enumerated the conditions that a native had to meet in order to be granted French citizenship (they included speaking and writing French, earning a decent living and displaying good moral standards). From 1830 to 1946, only between 3,000 and 6,000 native Algerians were granted French citizenship. In French West Africa, outside of the Four Communes, there were 2,500 "citoyens indigènes" out of a total population of 15 million.

French conservatives had been denouncing the assimilationist policies as products of a dangerous liberal fantasy. In the Protectorate of Morocco, the French administration attempted to use urban planning and colonial education to prevent cultural mixing and to uphold the traditional society upon which the French depended for collaboration, with mixed results. After World War II, the segregationist approach modeled in Morocco had been discredited by its connections to Vichyism, and assimilationism enjoyed a brief renaissance.

David P. Forsythe wrote: "From Senegal and Mauritania in the west to Niger in the east (what became French Africa), there was a parallel series of ruinous wars, resulting in tremendous numbers of people being violently enslaved. At the beginning of the twentieth century there may have been between 3 and 3.5 million slaves, representing over 30 percent of the total population, within this sparsely populated region." In 1905, the French abolished African slave trade, slavery in most of French West Africa. From 1906 to 1911, over a million slaves in French West Africa fled from their masters to earlier homes. In Madagascar over 500,000 slaves were freed following French abolition in 1896.

French conservatives had been denouncing the assimilationist policies as products of a dangerous liberal fantasy. In the Protectorate of Morocco, the French administration attempted to use urban planning and colonial education to prevent cultural mixing and to uphold the traditional society upon which the French depended for collaboration, with mixed results. After World War II, the segregationist approach modeled in Morocco had been discredited by its connections to Vichyism, and assimilationism enjoyed a brief renaissance.

David P. Forsythe wrote: "From Senegal and Mauritania in the west to Niger in the east (what became French Africa), there was a parallel series of ruinous wars, resulting in tremendous numbers of people being violently enslaved. At the beginning of the twentieth century there may have been between 3 and 3.5 million slaves, representing over 30 percent of the total population, within this sparsely populated region." In 1905, the French abolished African slave trade, slavery in most of French West Africa. From 1906 to 1911, over a million slaves in French West Africa fled from their masters to earlier homes. In Madagascar over 500,000 slaves were freed following French abolition in 1896.

Education

French colonial officials, influenced by the revolutionary ideal of equality, standardized schools, curricula, and teaching methods as much as possible. They did not establish colonial school systems with the idea of furthering the ambitions of the local people, but rather simply exported the systems and methods in vogue in the mother nation. Having a moderately trained lower bureaucracy was of great use to colonial officials. The emerging French-educated indigenous elite saw little value in educating rural peoples. After 1946 the policy was to bring the best students to Paris for advanced training. The result was to immerse the next generation of leaders in the growing anti-colonial diaspora centered in Paris. Impressionistic colonials could mingle with studious scholars or radical revolutionaries or so everything in between. Ho Chi Minh#Political education in France, Ho Chi Minh and other young radicals in Paris formed the French Communist party in 1920. Tunisia was exceptional. The colony was administered by Paul Cambon, who built an educational system for colonists and indigenous people alike that was closely modeled on mainland France. He emphasized female and vocational education. By independence, the quality of Tunisian education nearly equalled that in France. African nationalists rejected such a public education system, which they perceived as an attempt to retard African development and maintain colonial superiority. One of the first demands of the emerging nationalist movement after World War II was the introduction of full metropolitan-style education in French West Africa with its promise of equality with Europeans. In Algeria, the debate was polarized. The French set up schools based on the scientific method and French culture. The Pied-Noir (Catholic migrants from Europe) welcomed this. Those goals were rejected by the Moslem Arabs, who prized mental agility and their distinctive religious tradition. The Arabs refused to become patriotic and cultured Frenchmen and a unified educational system was impossible until the Pied-Noir and their Arab allies went into exile after 1962. In South Vietnam from 1955 to 1975 there were two competing powers in education, as the French continued their work and the Americans moved in. They sharply disagreed on goals. The French educators sought to preserving French culture among the Vietnamese elites and relied on the Mission Culturelle – the heir of the colonial Direction of Education – and its prestigious high schools. The Americans looked at the great mass of people and sought to make South Vietnam a nation strong enough to stop communism. The Americans had far more money, as USAID coordinated and funded the activities of expert teams, and particularly of academic missions. The French deeply resented the American invasion of their historical zone of cultural imperialism.Critics of French colonialism

Critics of French colonialism gained an international audience in the 1920s, and often used documentary reportage and access to agencies such as the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization to make their protests heard. The main criticism was the high level of violence and suffering among the natives. Major critics included Albert Londres, Félicien Challaye, and Paul Monet, whose books and articles were widely read. While the first stages of a takeover often involved the destruction of historic buildings in order to use the site for French headquarters, archaeologists and art historians soon engaged in systematic effort to identify, map and preserve historic sites, especially temples such as Angkor Wat, Champa ruins and the temples of Luang Prabang. Many French museums have collections of colonial materials. Since the 1980s the French government has opened new museums of colonial artifacts including the Musée du Quai Branly and the Cité Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration, in Paris; and the Maison des Civilisations et de l’Unité Réunionnaise in Réunion.Revolt in North Africa against Spain and France

The Berber independence leader Abd el-Krim (1882–1963) organized armed resistance against the Spanish and French for control of Morocco. The Spanish had faced unrest off and on from the 1890s, but in 1921 Spanish forces were massacred at the Battle of Annual. El-Krim founded an independent Rif Republic that operated until 1926 but had no international recognition. Paris and Madrid agreed to collaborate to destroy it. They sent in 200,000 soldiers, forcing el-Krim to surrender in 1926; he was exiled in the Pacific until 1947. Morocco became quiet, and in 1936 became the base from which Francisco Franco launched his revolt against Madrid.World War II

During World War II, allied Free France, often with British support, and Axis-aligned Vichy France struggled for control of the colonies, sometimes with outright military combat. By 1943, all of the colonies, except for Indochina under Japanese control, had joined the Free French cause.

The overseas empire helped liberate France as 300,000 North African Arabs fought in the ranks of the Free French. However Charles de Gaulle had no intention of liberating the colonies. He assembled the conference of colonial governors (excluding the nationalist leaders) in Brazzaville in January 1944 to announce plans for postwar Union that would replace the Empire. The Brazzaville manifesto proclaimed:

: the goals of the work of civilization undertaken by France in the colonies exclude all idea of autonomy, all possibility of development outside the French block of the Empire; the possible constitutional self-government in the colonies is to be dismissed.

The manifesto angered nationalists across the Empire, and set the stage for long-term wars in Indochina and Algeria that France would lose in humiliating fashion.

During World War II, allied Free France, often with British support, and Axis-aligned Vichy France struggled for control of the colonies, sometimes with outright military combat. By 1943, all of the colonies, except for Indochina under Japanese control, had joined the Free French cause.

The overseas empire helped liberate France as 300,000 North African Arabs fought in the ranks of the Free French. However Charles de Gaulle had no intention of liberating the colonies. He assembled the conference of colonial governors (excluding the nationalist leaders) in Brazzaville in January 1944 to announce plans for postwar Union that would replace the Empire. The Brazzaville manifesto proclaimed:

: the goals of the work of civilization undertaken by France in the colonies exclude all idea of autonomy, all possibility of development outside the French block of the Empire; the possible constitutional self-government in the colonies is to be dismissed.

The manifesto angered nationalists across the Empire, and set the stage for long-term wars in Indochina and Algeria that France would lose in humiliating fashion.

Decolonization

The French colonial empire began to fall during the Second World War, when various parts were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the United States and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia). However, control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle. The French Union, included in the French Constitution of 1946, Constitution of 1946, nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris remained in full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with only limited local power and budgets. There emerged a group of elites, known as evolués, who were natives of the overseas territories but lived in metropolitan France.Conflict

France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonisation movement. In Algeria demonstrations in May 1945 were Setif and Guelma massacre, repressed with an estimated 6,000 to 45,000 Algerians killed. Unrest in Haiphong, Indochina, in November 1945 was met by a warship bombarding the city. Paul Ramadier's (French Section of the Workers' International, SFIO) cabinet repressed the Malagasy Uprising in Madagascar in 1947. The French blamed education. French officials estimated the number of Malagasy killed from a low of 11,000 to a French Army estimate of 89,000. Also in Indochina, Ho Chi Minh's Vietminh, Viet Minh, which was backed by the Soviet Union and China, declared Vietnam's independence, which started the First Indochina War. The war dragged on until 1954, when the Viet Minh decisively defeated the French at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, Battle of Điện Biên Phủ in northern Vietnam, which was the last major battle between the French and the Vietnamese in the First Indochina War. Following the Vietnamese victory at Điện Biên Phủ and the signing of the Geneva Conference (1954), 1954 Geneva Accords, France agreed to withdraw its forces from all its colonies in French Indochina, while stipulating that Vietnam would be temporarily divided at the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone, 17th parallel, with control of the north given to the Soviet-backed Viet Minh as the North Vietnam, Democratic Republic of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh, and the south becoming the State of Vietnam under former Nguyen-dynasty Emperor Bảo Đại, who Abdication, abdicated following the August Revolution, 1945 August Revolution under pressure from Ho. However, in 1955, the State of Vietnam's Prime Minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, toppled Bảo Đại in a fraud-ridden 1955 State of Vietnam referendum, referendum and proclaimed himself president of the new Republic of Vietnam. The refusal of Ngô Đình Diệm, the US-supported president of the first Republic of Vietnam [RVN], to allow elections in 1956 – as had been stipulated by the Geneva Conference – in fear of Ho Chi Minh's victory and subsequently a total communist takeover, eventually led to the Vietnam War.

In France's African colonies, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection, which started in 1955 and headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed over a two-year period, with perhaps as many as 100 people killed. However, France formally relinquished its protectorate over Morocco and granted it independence in 1956.

French involvement in Algeria stretched back a century. The movements of Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj had marked the period between the two world wars, but both sides radicalised after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War of Independence, Algerian War started in 1954. Torture during the Algerian War of Independence, Atrocities characterized both sides, and the number killed became highly controversial estimates that were made for propaganda purposes. Algeria was a three-way conflict due to the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there in French rule in Algeria, the 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.

The French Union was replaced in the French Constitution of 1958, Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part in the new organisation. However, the French Community ceased to operate before the end of the Algerian War. Almost all of the other former African colonies achieved independence in 1960. The French government refused to allow the populations of the former colonies the right they had in the new French Constitution of 1958, as French citizens with equal rights, to choose for their territories to become full ''départements'' of France. The French government had ensured that a constitutional law (60-525) was passed which removed the need for a referendum in a territory to confirm a change in status towards independence or départementalisation, so the voters who had rejected independence in 1958 were not consulted about it in 1960. There are still a few former colonies that chose to remain part of France, under the status of French overseas departments and territories, overseas ''départements'' or territories.

Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the ''Françafrique'' had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence on one hand, he was maintaining French dominance through the operations of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular Biafra in the Nigerian Civil War during the late 1960s.

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There also were complications and delays in the New Hebrides Vanuatu, which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French suzerainty. The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in referendum in 1974 to retain its link with France and not become independent like the other three islands of the Comoro archipelago.

Following the Vietnamese victory at Điện Biên Phủ and the signing of the Geneva Conference (1954), 1954 Geneva Accords, France agreed to withdraw its forces from all its colonies in French Indochina, while stipulating that Vietnam would be temporarily divided at the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone, 17th parallel, with control of the north given to the Soviet-backed Viet Minh as the North Vietnam, Democratic Republic of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh, and the south becoming the State of Vietnam under former Nguyen-dynasty Emperor Bảo Đại, who Abdication, abdicated following the August Revolution, 1945 August Revolution under pressure from Ho. However, in 1955, the State of Vietnam's Prime Minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, toppled Bảo Đại in a fraud-ridden 1955 State of Vietnam referendum, referendum and proclaimed himself president of the new Republic of Vietnam. The refusal of Ngô Đình Diệm, the US-supported president of the first Republic of Vietnam [RVN], to allow elections in 1956 – as had been stipulated by the Geneva Conference – in fear of Ho Chi Minh's victory and subsequently a total communist takeover, eventually led to the Vietnam War.

In France's African colonies, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection, which started in 1955 and headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed over a two-year period, with perhaps as many as 100 people killed. However, France formally relinquished its protectorate over Morocco and granted it independence in 1956.

French involvement in Algeria stretched back a century. The movements of Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj had marked the period between the two world wars, but both sides radicalised after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War of Independence, Algerian War started in 1954. Torture during the Algerian War of Independence, Atrocities characterized both sides, and the number killed became highly controversial estimates that were made for propaganda purposes. Algeria was a three-way conflict due to the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there in French rule in Algeria, the 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.

The French Union was replaced in the French Constitution of 1958, Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part in the new organisation. However, the French Community ceased to operate before the end of the Algerian War. Almost all of the other former African colonies achieved independence in 1960. The French government refused to allow the populations of the former colonies the right they had in the new French Constitution of 1958, as French citizens with equal rights, to choose for their territories to become full ''départements'' of France. The French government had ensured that a constitutional law (60-525) was passed which removed the need for a referendum in a territory to confirm a change in status towards independence or départementalisation, so the voters who had rejected independence in 1958 were not consulted about it in 1960. There are still a few former colonies that chose to remain part of France, under the status of French overseas departments and territories, overseas ''départements'' or territories.

Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the ''Françafrique'' had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence on one hand, he was maintaining French dominance through the operations of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular Biafra in the Nigerian Civil War during the late 1960s.

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There also were complications and delays in the New Hebrides Vanuatu, which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French suzerainty. The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in referendum in 1974 to retain its link with France and not become independent like the other three islands of the Comoro archipelago.

Demographics

French census statistics from 1936 show an imperial population, outside of Metropolitan France itself, of 69.1 million people. Of the total population, 16.1 million lived in North Africa, 25.5 million in sub-Saharan Africa, 3.2 million in the Middle East, 0.3 million in the Indian subcontinent, 23.2 million in East and South-East Asia, 0.15 million in the South Pacific, and 0.6 million in the Caribbean. The largest colonies were the general governorate of French Indochina (grouping five separate colonies and protectorates), with 23.0 million, the general governorate of French West Africa (grouping eight separate colonies), with 14.9 million, the general governorate of French Algeria, Algeria (grouping three Departments of France#Departments of Algeria (Départements d'Algérie), departments and four Saharan territories), with 7.2 million, the French protectorate in Morocco, protectorate of Morocco, with 6.3 million, the general governorate of French Equatorial Africa (grouping four separate colonies), with 3.9 million, and French Madagascar, Madagascar and Dependencies (incl. the Comoro Islands), with 3.8 million. 2.7 million Europeans (French and non-French citizens) and assimilated natives (non-European French citizens) lived in the French colonial empire in 1936 besides 66.4 million non-assimilated natives (French subjects but not citizens). The majority of Europeans lived in North Africa. Non-European French citizens lived essentially in the four "old colonies" (French settlers

Unlike elsewhere in Europe, France experienced relatively low levels of emigration to the Americas, with the exception of the Huguenots in British or Dutch colonies. France generally had close to the slowest natural population growth in Europe, and emigration pressures were therefore quite small. A small but significant emigration, numbering only in the tens of thousands, of mainly Roman Catholic French populations led to the settlement of the provinces of Acadia, Canada andFox News Channel

Territories

Africa

* French Algeria * French Protectorate in Morocco * French Protectorate of Tunisia * French West Africa ** French Mauritania ** French Senegal ** French Guinea ** French Ivory Coast ** French Niger ** French Upper Volta ** French Dahomey ** French Togoland ** French Sudan * French Equatorial Africa ** French Gabon ** French Congo ** Ubangui-Shari ** French Chad * French Cameroon * French Madagascar ** Seychelles ** Île de France (Mauritius) ** Comoros ** Mayotte **Asia

* Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, French mandate of Syria * Greater Lebanon * French India * French and British interregnum in the Dutch East Indies#French interregnum 1806–1811, Dutch East Indies * French Indochina ** French Cochinchina ** Tonkin (French protectorate), Tonkin ** Annam (French protectorate), Annam ** French protectorate of Cambodia ** French protectorate of Laos * China enclaves ** Foreign concessions in Tianjin, French concession in Tianjin ** Shanghai French Concession ** GuangzhouwanThe Caribbean

* Commonwealth of Dominica *South America

* France Antarctique *North America

* New France ** Acadia ** United States ** Canada (New France), Canada **Oceania

* New Caledonia * French Polynesia * Wallis and Futuna * Clipperton Island * VanuatuSee also

* Army of the Levant * CFA franc * Colonialism * Decolonization * Evolution of the French Empire * Francization * French Army units with a tradition of service overseas ** 1900–1958: Troupes de marine ** 1900–1958: Troupes coloniales ** Tirailleurs ** Spahis ** Zouaves * French colonial flags * French colonisation of the Americas * French law on colonialism (for teachers, 2005) * History of France ** Second French Empire ** French Third Republic ** Kingdom of France * International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919) * List of French possessions and colonies * New France * Organisation internationale de la Francophonie * Overseas France * Postage stamps of the French colonies * Scramble for Africa * Timeline of imperialismReferences

Further reading

* Langley, Michael. "Bizerta to the Bight: The French in Africa." ''History Today.'' (Oct 1972), pp 733–739. covers 1798 to 1900. * Hutton, Patrick H. ed. ''Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940'' (2 vol 1986) * Northcutt, Wayne, ed. ''Historical Dictionary of the French Fourth and Fifth Republics, 1946– 1991'' (1992)Policies and colonies

* Aldrich, Robert. ''Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion'' (1996) * Aldrich, Robert. ''The French Presence in the South Pacific, 1842–1940'' (1989). * Anderson, Fred. ''Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766'' (2001), covers New France in Canada * Baumgart, Winfried. ''Imperialism: The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion, 1880–1914'' (1982) * Betts, Raymond. ''Tricouleur: The French Overseas Empire'' (1978), 174pp * Betts, Raymond. ''Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914'' (2005excerpt and text search

* . * * Clayton, Anthony. ''The Wars of French Decolonization'' (1995) * Cogneau, Denis, et al. "Taxation in Africa from Colonial Times to Present Evidence from former French colonies 1900-2018." (2021)

online

* Conklin, Alice L. ''A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895–1930'' (1997

online

* Evans, Martin. "From colonialism to post-colonialism: the French empire since Napoleon." in Martin S. Alexander, ed., ''French History since Napoleon'' (1999) pp: 391–415. * Gamble, Harry. ''Contesting French West Africa: Battles over Schools and the Colonial Order, 1900–1950'' (U of Nebraska Press, 2017). 378 pp

online review

* Jennings, Eric T. ''Imperial Heights: Dalat and the Making and Undoing of French Indochina'' (2010). * * Lawrence, Adria. ''Imperial rule and the politics of nationalism: anti-colonial protest in the French empire'' (Cambridge UP, 2013). * . * Klein, Martin A. ''Slavery and colonial rule in French West Africa'' (Cambridge University Press, 1998) * Manning, Patrick. ''Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880-1995'' (Cambridge UP, 1998)

online

* Neres, Philip. ''French-speaking West Africa: From Colonial Status to Independence'' (1962

online

* Priestley, Herbert Ingram. ''France overseas: a study of modern imperialism'' (1938) 464pp. * Quinn, Frederick. ''The French Overseas Empire'' (2000

online

* . * Poddar, Prem, and Lars Jensen, eds., ''A historical companion to postcolonial literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires'' (Edinburgh UP, 2008)

excerpt

als

entire text online

* . * Priestley, Herbert Ingram. (1938) ''France overseas;: A study of modern imperialism'' 463pp; encyclopedic coverage as of late 1930s * Roberts, Stephen H. ''History of French Colonial Policy (1870-1925)'' (2 vol 1929

vol 1 online

als

vol 2 online

Comprehensive scholarly history * . * Strother, Christian. "Waging War on Mosquitoes: Scientific Research and the Formation of Mosquito Brigades in French West Africa, 1899–1920." ''Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences'' (2016): jrw005. * Thomas, Martin. ''The French Empire Between the Wars: Imperialism, Politics and Society'' (2007) covers 1919–1939 * Thompson, Virginia, and Richard Adloff. ''French West Africa'' (Stanford UP, 1958). * Wellington, Donald C. ''French East India companies: A historical account and record of trade'' (Hamilton Books, 2006) * Wesseling, H.L. and Arnold J. Pomerans. ''Divide and rule: The partition of Africa, 1880–1914'' (Praeger, 1996.

online

* Wesseling, H.L. ''The European Colonial Empires: 1815–1919'' (Routledge, 2015).

Decolonization

* Betts, Raymond F. ''Decolonization'' (2nd ed. 2004) * Betts, Raymond F. ''France and Decolonisation, 1900–1960'' (1991) * Chafer, Tony. ''The end of empire in French West Africa: France's successful decolonization'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2002). * Chamberlain, Muriel E. ed. ''Longman Companion to European Decolonisation in the Twentieth Century'' (Routledge, 2014) * Clayton, Anthony. ''The wars of French decolonization'' (Routledge, 2014). * Cooper, Frederick. "French Africa, 1947–48: Reform, Violence, and Uncertainty in a Colonial Situation." ''Critical Inquiry'' (2014) 40#4 pp: 466–478in JSTOR

* Ikeda, Ryo. ''The Imperialism of French Decolonisation: French Policy and the Anglo-American Response in Tunisia and Morocco'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) * Jansen, Jan C. & Jürgen Osterhammel. ''Decolonization: A Short History'' (princeton UP, 2017)

* Jones, Max, et al. "Decolonising imperial heroes: Britain and France." ''Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History'' 42#5 (2014): 787–825. * Lawrence, Adria K. ''Imperial Rule and the Politics of Nationalism: Anti-Colonial Protest in the French Empire'' (Cambridge UP, 2013

online reviews

* James McDougall (academic), McDougall, James. "The Impossible Republic: The Reconquest of Algeria and the Decolonization of France, 1945–1962," ''The Journal of Modern History'' 89#4 (December 2017) pp 772–81

excerpt

* Rothermund, Dietmar. ''Memories of Post-Imperial Nations: The Aftermath of Decolonization, 1945–2013'' (2015

excerpt

Compares the impact on Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Portugal, Italy and Japan * Rothermund, Dietmar. ''The Routledge companion to decolonization'' (Routledge, 2006), comprehensive global coverage; 365pp * Shepard, Todd. ''The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France'' (2006) * Simpson, Alfred William Brian. ''Human Rights and the End of Empire: Britain and the Genesis of the European Convention'' (Oxford University Press, 2004). * Smith, Tony. "A comparative study of French and British decolonization." ''Comparative Studies in Society and History'' (1978) 20#1 pp: 70–102

online

* Smith, Tony. "The French Colonial Consensus and People's War, 1946–58." ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1974): 217–247

in JSTOR

* Thomas, Martin, Bob Moore, and Lawrence J. Butler. ''Crises of Empire: Decolonization and Europe's imperial states'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015) * Von Albertini, Rudolf. ''Decolonization: the Administration and Future of the Colonies, 1919–1960'' (Doubleday, 1971), scholarly analysis of French policies, pp 265–469..

Images and impact on France

* Andrew, Christopher M., and Alexander Sydney Kanya-Forstner. "France, Africa, and the First World War." ''Journal of African History'' 19.1 (1978): 11–23. *online

* Andrew, C. M., and A. S. Kanya-Forstner. "The French 'Colonial Party': Its Composition, Aims and Influence, 1885-1914." ''Historical Journal'' 14#1 (1971): 99-128

online

* August, Thomas G. ''The Selling of the Empire: British and French Imperialist Propaganda, 1890–1940'' (1985) * Chafer, Tony, and Amanda Sackur. ''Promoting the Colonial Idea: Propaganda and Visions of Empire in France'' (2002

online

* . * Conkin, Alice L. ''A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930'' (1997

online

* Dobie, Madeleine. ''Trading Places: Colonization & Slavery in 18th-Century French Culture'' (2010) * . * Rosenblum, Mort. ''Mission to Civilize: The French Way'' (1986

online review

* Rothermund, Dietmar. ''Memories of Post-Imperial Nations: The Aftermath of Decolonization, 1945–2013'' (2015

excerpt

Compares the impact on Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Portugal, Italy and Japan * Singer, Barnett, and John Langdon. ''Cultured Force: Makers and Defenders of the French Colonial Empire'' (2008) * Thomas, Martin, ed. ''The French Colonial Mind, Volume 1: Mental Maps of Empire and Colonial Encounters'' (France Overseas: Studies in Empire and D) (2012); ''The French Colonial Mind, Volume 2: Violence, Military Encounters, and Colonialism'' (2012)

Historiography and memoir

* Bennington, Alice. "Writing Empire? The Reception of Post-Colonial Studies in France." ''Historical Journal'' (2016) 59#4: 1157–1186abstract

* Dubois, Laurent. "The French Atlantic," in ''Atlantic History: A Critical Appraisal,'' ed. by Jack P. Greene and Philip D. Morgan, (Oxford UP, 2009) pp 137–61 * Dwyer, Philip. "Remembering and Forgetting in Contemporary France: Napoleon, Slavery, and the French History Wars," ''French Politics, Culture & Society'' (2008) 26#3 pp 110–122. * . * Greer, Allan. "National, Transnational, and Hypernational Historiographies: New France Meets Early American History," ''Canadian Historical Review,'' (2010) 91#4 pp 695–724

* Hodson, Christopher, and Brett Rushforth, "Absolutely Atlantic: Colonialism and the Early Modern French State in Recent Historiography," ''History Compass,'' (January 2010) 8#1 pp 101–117 * Lawrence, Adria K. ''Imperial Rule and the Politics of Nationalism: Anti-Colonial Protest in the French Empire'' (Cambridge UP, 2013

online reviews

External links

*French Colonial Historical Society

French Colonial Historical Society

''French Colonial History''

an annual volume of refereed, scholarly articles {{DEFAULTSORT:French Colonial Empire Former empires French colonial empire, Former French colonies, History of European colonialism Overseas empires 1534 establishments in the French colonial empire 1977 disestablishments in the French colonial empire Historical transcontinental empires