Fredrick Engels on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

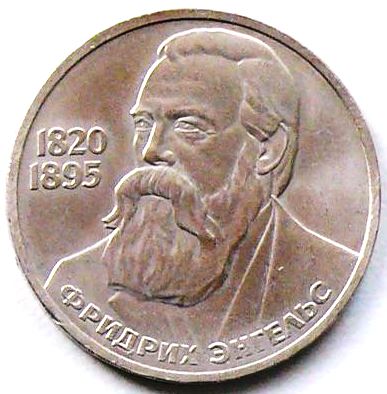

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

''

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in

Engels decided to return to Germany in 1844. On the way, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had an earlier correspondence. Marx had been living in Paris since late October 1843, after the ''Rheinische Zeitung'' was banned in March 1843 by Prussian governmental authorities. Prior to meeting Marx, Engels had become established as a fully developed

Engels decided to return to Germany in 1844. On the way, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had an earlier correspondence. Marx had been living in Paris since late October 1843, after the ''Rheinische Zeitung'' was banned in March 1843 by Prussian governmental authorities. Prior to meeting Marx, Engels had become established as a fully developed

The nation of Belgium, founded in 1830, was endowed with one of the most liberal constitutions in Europe and functioned as refuge for progressives from other countries. From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx lived in

The nation of Belgium, founded in 1830, was endowed with one of the most liberal constitutions in Europe and functioned as refuge for progressives from other countries. From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx lived in

To help Marx with '' Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-ökonomische Revue'', the new publishing effort in London, Engels sought ways to escape the continent and travel to London. On 5 October 1849, Engels arrived in the Italian port city of Genoa. There, Engels booked passage on the English schooner, ''Cornish Diamond'' under the command of a Captain Stevens. The voyage across the western Mediterranean, around the Iberian Peninsula by sailing schooner took about five weeks. Finally, the ''Cornish Diamond'' sailed up the River Thames to London on 10 November 1849 with Engels on board.

Upon his return to Britain, Engels re-entered the Manchester company in which his father held shares to support Marx financially as he worked on ''

To help Marx with '' Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-ökonomische Revue'', the new publishing effort in London, Engels sought ways to escape the continent and travel to London. On 5 October 1849, Engels arrived in the Italian port city of Genoa. There, Engels booked passage on the English schooner, ''Cornish Diamond'' under the command of a Captain Stevens. The voyage across the western Mediterranean, around the Iberian Peninsula by sailing schooner took about five weeks. Finally, the ''Cornish Diamond'' sailed up the River Thames to London on 10 November 1849 with Engels on board.

Upon his return to Britain, Engels re-entered the Manchester company in which his father held shares to support Marx financially as he worked on ''

Engels's interests included poetry,

Engels's interests included poetry,

Since 1931, Engels has had a Russian city named after him—

Since 1931, Engels has had a Russian city named after him—

This book was written by Marx and Engels in November 1844. It is a critique on the

This book was written by Marx and Engels in November 1844. It is a critique on the

Karl Marx: A Biography

', prepared by the Institute of Marxism–Leninism of the C.P.S.U. Central Committee, Moscow: Progress Publishers * Green, John (2008). ''Engels: A Revolutionary Life'', London: Artery Publications, * Henderson, W.O. (1976). ''The life of Friedrich Engels'', London: Cass, * Hunt, Tristram (2009). ''The Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels'', London: Allen Lane. *

Marx/Engels Biographical Archive

by

Reason in Revolt: Marxism and Modern Science

Engels: The Che Guevara of his Day

* ttp://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/biografien/EngelsFriedrich/index.html German Biography from dhm.de* * * *

''Frederick Engels: A Biography''

(Soviet work)

''Frederick Engels: A Biography''

(East German work)

Engels was Right: Early Human Kinship was Matriliineal

* Archive o

Karl Marx / Friedrich Engels Papers

at the

Libcom.org/library Friedrich Engels archive

Works by Friedrich Engels

(in German) at

Pathfinder Press

* Friedrich Engels

"On Rifled Cannon"

articles from the New York ''Tribune'', April, May and June 1860, reprinted in ''Military Affairs'' 21, no. 4 (Winter 1957) ed. Morton Borden, 193–198.

Marx and Engels in their native German languageEngels in Eastbourne - Commemorating the life, work and legacy of Friedrich Engels in Eastbourne

{{DEFAULTSORT:Engels, Friedrich 1820 births 1895 deaths 19th-century atheists 19th-century German economists 19th-century German male writers 19th-century German non-fiction writers 19th-century German philosophers 19th-century Prussian people Atheist philosophers European democratic socialists German industrialists German Communist writers Cultural critics Deaths from throat cancer German anti-capitalists German atheism activists German atheist writers German emigrants to England German journalists German political philosophers German revolutionaries Karl Marx Marxist theorists German Marxist writers Materialists Members of the International Workingmen's Association Orthodox Marxists People from the Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg People from the Rhine Province Businesspeople from Wuppertal People of the Revolutions of 1848 Philosophers of culture Philosophers of economics Philosophers of history Prussian Army personnel German social commentators Social critics Social philosophers Socialist economists Theoretical historians Theorists on Western civilization Urban theorists 19th-century German businesspeople Writers from Wuppertal Critics of political economy Deaths from cancer in England

''

Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary'' is a large American dictionary, first published in 1966 as ''The Random House Dictionary of the English Language: The Unabridged Edition''. Edited by Editor-in-chief Jess Stein, it contained 315, ...

''. ; 28 November 1820 – 5 August 1895) was a German philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, critic of political economy, historian, political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized by their ...

and revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revoluti ...

. He was also a businessman, journalist and political activist, whose father was an owner of large textile factories in Salford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

(Lancashire, England) and Barmen

Barmen is a former industrial metropolis of the region of Bergisches Land, Germany, which merged with four other towns in 1929 to form the city of Wuppertal.

Barmen, together with the neighbouring town of Elberfeld founded the first electric ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

(now Wuppertal

Wuppertal (; "''Wupper Dale''") is, with a population of approximately 355,000, the seventh-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia as well as the 17th-largest city of Germany. It was founded in 1929 by the merger of the cities and to ...

, Germany).

Engels developed what is now known as Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

together with Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

. In 1845, he published ''The Condition of the Working Class in England

''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' (german: Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England) is an 1845 book by the German philosopher Friedrich Engels, a study of the industrial working class in Victorian England. Engels' first book, ...

'', based on personal observations and research in English cities. In 1848, Engels co-authored ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Comm ...

'' with Marx and also authored and co-authored (primarily with Marx) many other works. Later, Engels supported Marx financially, allowing him to do research and write ''Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in Historical mater ...

''. After Marx's death, Engels edited the second and third volumes of ''Das Kapital''. Additionally, Engels organised Marx's notes on the ''Theories of Surplus Value

''Theories of Surplus Value'' (german: Theorien über den Mehrwert) is a draft manuscript written by Karl Marx between January 1862 and July 1863. It is mainly concerned with the Western Europe, Western European theorizing about ''Mehrwert'' (add ...

'' which were later published as the "fourth volume" of ''Das Kapital''. In 1884, he published ''The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

''The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State: in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan'' (german: Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigenthums und des Staats) is an 1884 philosophical treatise by Friedrich Engels. It is p ...

'' on the basis of Marx's ethnographic research.

On 5 August 1895, aged 74, Engels died of laryngeal cancer

Laryngeal cancers are mostly squamous-cell carcinomas, reflecting their origin from the epithelium of the larynx.

Cancer can develop in any part of the larynx. The prognosis is affected by the location of the tumour. For the purposes of staging, ...

in London. Following cremation, his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head

Beachy Head is a chalk headland in East Sussex, England. It is situated close to Eastbourne, immediately east of the Seven Sisters.

Beachy Head is located within the administrative area of Eastbourne Borough Council which owns the land, formin ...

, near Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the la ...

.

Biography

Early life

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen

Barmen is a former industrial metropolis of the region of Bergisches Land, Germany, which merged with four other towns in 1929 to form the city of Wuppertal.

Barmen, together with the neighbouring town of Elberfeld founded the first electric ...

, Jülich-Cleves-Berg, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

(now Wuppertal

Wuppertal (; "''Wupper Dale''") is, with a population of approximately 355,000, the seventh-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia as well as the 17th-largest city of Germany. It was founded in 1929 by the merger of the cities and to ...

, Germany), as eldest son of Friedrich Engels Sr. (1796–1860) and of Elisabeth "Elise" Franziska Mauritia von Haar (1797–1873). The wealthy Engels family owned large cotton-textile mills in Barmen and Salford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

, both expanding industrial metropoles. Friedrich's parents were devout Pietist

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life, including a social concern for ...

Protestants and they raised their children accordingly.

At the age of 13, Engels attended grammar school ('' Gymnasium'') in the adjacent city of Elberfeld

Elberfeld is a municipal subdivision of the German city of Wuppertal; it was an independent town until 1929.

History

The first official mentioning of the geographic area on the banks of today's Wupper River as "''elverfelde''" was in a docu ...

but had to leave at 17, due to pressure from his father, who wanted him to become a businessman and start work as a mercantile apprentice in the family firm. After a year in Barmen, the young Engels was in 1838 sent by his father to undertake an apprenticeship at a trading house in Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

.Tucker, Robert C. ''The Marx-Engels Reader'', p. xv His parents expected that he would follow his father into a career in the family business. Their son's revolutionary activities disappointed them. It would be some years before he joined the family firm.

Whilst at Bremen, Engels began reading the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

, whose teachings dominated German philosophy at that time. In September 1838 he published his first work, a poem entitled "The Bedouin", in the ''Bremisches Conversationsblatt'' No. 40. He also engaged in other literary work and began writing newspaper articles critiquing the societal ills of industrialisation. He wrote under the pseudonym "Friedrich Oswald" to avoid connecting his family with his provocative writings.

In 1841, Engels performed his military service in the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

as a member of the Household Artillery (german: link=no, Garde-Artillerie-Brigade). Assigned to Berlin, he attended university lectures at the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

and began to associate with groups of Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians (german: Junghegelianer), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel ...

. He anonymously published articles in the ''Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Rheinische Zeitung'' ("Rhenish Newspaper") was a 19th-century German newspaper, edited most famously by Karl Marx. The paper was launched in January 1842 and terminated by Prussian state censorship in March 1843. The paper was eventually su ...

'', exposing the poor employment- and living-conditions endured by factory workers. The editor of the ''Rheinische Zeitung'' was Karl Marx, but Engels would not meet Marx until late November 1842. Engels acknowledged the influence of German philosophy on his intellectual development throughout his career. In 1840, he also wrote: "To get the most out of life you must be active, you must live and you must have the courage to taste the thrill of being young."

Engels developed atheistic

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

beliefs and his relationship with his parents became strained.

Manchester and Salford

In 1842, his parents sent the 22-year-old Engels toManchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, England, a manufacturing centre where industrialisation was on the rise. He was to work in Weaste

Weaste () is a suburb in the City of Salford, Greater Manchester, England. In 2014, Weaste and Seedley ward had a population of 12,616.

History

Historically in Lancashire, it is an industrial area, with many industrial estates. The A57 (Ec ...

, Salford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

, in the offices of Ermen and Engels's Victoria Mill, which made sewing threads. Engels's father thought that working at the Manchester firm might make his son reconsider some of his radical opinions. On his way to Manchester, Engels visited the office of the ''Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Rheinische Zeitung'' ("Rhenish Newspaper") was a 19th-century German newspaper, edited most famously by Karl Marx. The paper was launched in January 1842 and terminated by Prussian state censorship in March 1843. The paper was eventually su ...

'' in Cologne and met Karl Marx for the first time. Initially they were not impressed with each other. Marx mistakenly thought that Engels was still associated with the Berliner Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians (german: Junghegelianer), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel ...

, with whom Marx had just broken off ties.

In Manchester, Engels met Mary Burns

Mary Burns (29 September 1821 – 7 January 1863)Whitfield, Roy (1988) ''Friedrich Engels in Manchester'', Working Class Movement Library, was a working-class Irish woman, best known as the lifelong partner of Friedrich Engels.

Burns lived in ...

, a fierce young Irish woman with radical opinions who worked in the Engels factory. They began a relationship that lasted 20 years until her death in 1863. The two never married, as both were against the institution of marriage. While Engels regarded stable monogamy as a virtue, he considered the current state and church-regulated marriage as a form of class oppression. Burns guided Engels through Manchester and Salford

Salford () is a city and the largest settlement in the City of Salford metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. In 2011, Salford had a population of 103,886. It is also the second and only other city in the metropolitan county afte ...

, showing him the worst districts for his research.

Engels was often described as a man with a very strong libido and not much restraint. He had numerous affairs with a string of lovers and despite his condemnation of prostitution as "exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie" he also occasionally paid for sex. In 1846 he wrote to Marx: "If I had an income of 5000 francs I would do nothing but work and amuse myself with women until I went to pieces. If there were no Frenchwomen, life wouldn't be worth living. But so long as there are grisettes, well and good!" His most controversial relationship was with the wife of his rival Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His socialist theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zion ...

, Sibylle, who later accused him of rape.

While in Manchester between October and November 1843, Engels wrote his first critique of political economy

Critique of political economy or critique of economy is a form of Social criticism, social critique that rejects the various social categories and structures that constitute the mainstream discourse concerning the forms and modalities of resourc ...

, entitled "Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy

''Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy'' is an article by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1843 for the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher.https://tilde.town/~xat/rt/pdf/engels_1843_outline_political_economy.pdf

The article ...

". Engels sent the article to Paris, where Marx published it in the ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher

The ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher'' (''German–French Annals'') was a journal published in Paris by Karl Marx and Arnold Ruge. It was created as a reaction to the censorship of the ''Rheinische Zeitung''.

History and profile

''Deutsch� ...

'' in 1844.

While observing the slums of Manchester in close detail, Engels took notes of its horrors, notably child labour

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

, the despoiled environment, and overworked and impoverished labourers. He sent a trilogy of articles to Marx. These were published in the ''Rheinische Zeitung'' and then in the ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher'', chronicling the conditions among the working class in Manchester. He later collected these articles for his influential first book, ''The Condition of the Working Class in England

''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' (german: Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England) is an 1845 book by the German philosopher Friedrich Engels, a study of the industrial working class in Victorian England. Engels' first book, ...

'' (1845). Written between September 1844 and March 1845, the book was published in German in 1845. In the book, Engels described the "grim future of capitalism and the industrial age", noting the details of the squalor in which the working people lived. The book was published in English in 1887. Archival resources contemporary to Engels's stay in Manchester shed light on some of the conditions he describes, including a manuscript (MMM/10/1) held by special collections at the University of Manchester. This recounts cases seen in the Manchester Royal Infirmary, where industrial accidents dominated and which resonate with Engels's comments on the disfigured persons seen walking round Manchester as a result of such accidents.

Engels continued his involvement with radical journalism and politics. He frequented areas popular among members of the English labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

and Chartist movements, whom he met. He also wrote for several journals, including ''The Northern Star

''The Northern Star'' is a daily newspaper serving Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The newspaper is owned by News Corp Australia.

''The Northern Star'' is circulated to Lismore and surrounding communities, from Tweed Heads to the north ...

'', Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

's '' New Moral World,'' and the '' Democratic Review'' newspaper.

Paris

Engels decided to return to Germany in 1844. On the way, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had an earlier correspondence. Marx had been living in Paris since late October 1843, after the ''Rheinische Zeitung'' was banned in March 1843 by Prussian governmental authorities. Prior to meeting Marx, Engels had become established as a fully developed

Engels decided to return to Germany in 1844. On the way, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx, with whom he had an earlier correspondence. Marx had been living in Paris since late October 1843, after the ''Rheinische Zeitung'' was banned in March 1843 by Prussian governmental authorities. Prior to meeting Marx, Engels had become established as a fully developed materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

and scientific socialist, independent of Marx's philosophical development.

In Paris, Marx was publishing the ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher

The ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher'' (''German–French Annals'') was a journal published in Paris by Karl Marx and Arnold Ruge. It was created as a reaction to the censorship of the ''Rheinische Zeitung''.

History and profile

''Deutsch� ...

''. Engels met Marx for a second time at the Café de la Régence

The Café de la Régence in Paris was an important European centre of chess in the 18th and 19th centuries. All important chess masters of the time played there.

The Café's masters included, but are not limited to:

* Paul Morphy

* François- ...

on the Place du Palais, 28 August 1844. The two quickly became close friends and remained so their entire lives. Marx had read and was impressed by Engels's articles on ''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' in which he had written that " class which bears all the disadvantages of the social order without enjoying its advantages, ..Who can demand that such a class respect this social order?" Marx adopted Engels's idea that the working class would lead the revolution against the bourgeoisie as society advanced toward socialism, and incorporated this as part of his own philosophy.

Engels stayed in Paris to help Marx write '' The Holy Family''. It was an attack on the Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians (german: Junghegelianer), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel ...

and the Bauer brothers, and was published in late February 1845. Engels's earliest contribution to Marx's work was writing for the ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher'', edited by both Marx and Arnold Ruge

Arnold Ruge (13 September 1802 – 31 December 1880) was a German philosopher and political writer. He was the older brother of Ludwig Ruge.

Studies in university and prison

Born in Bergen auf Rügen, he studied in Halle, Jena and Heidelberg. ...

, in Paris in 1844. During this time in Paris, both Marx and Engels began their association with and then joined the secret revolutionary society called the League of the Just

The League of the Just (German: ''Bund der Gerechten'') or League of Justice was a Christian communist international revolutionary organization. It was founded in 1836 by branching off from its ancestor, the League of Outlaws (German: ''Bund der ...

. The League of the Just had been formed in 1837 in France to promote an egalitarian society through the overthrow of the existing governments. In 1839, the League of the Just participated in the 1839 rebellion fomented by the French utopian revolutionary socialist, Louis Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui (; 8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Biography Early life, political activity and first imprisonment (1805–1848)

Bla ...

; however, as Ruge remained a Young Hegelian in his belief, Marx and Ruge soon split and Ruge left the ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher''. Nonetheless, following the split, Marx remained friendly enough with Ruge that he sent Ruge a warning on 15 January 1845 that the Paris police were going to execute orders against him, Marx and others at the ''Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher'' requiring all to leave Paris within 24 hours. Marx himself was expelled from Paris by French authorities on 3 February 1845 and settled in Brussels with his wife and one daughter. Having left Paris on 6 September 1844, Engels returned to his home in Barmen, Germany, to work on his ''The Condition of the Working Class in England'', which was published in late May 1845. Even before the publication of his book, Engels moved to Brussels in late April 1845, to collaborate with Marx on another book, ''German Ideology

''The German Ideology'' (German: ''Die deutsche Ideologie'', sometimes written as ''A Critique of the German Ideology'') is a set of manuscripts originally written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels around April or early May 1846. Marx and Engels ...

''. While living in Barmen, Engels began making contact with Socialists in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

to raise money for Marx's publication efforts in Brussels; however, these contacts became more important as both Marx and Engels began political organizing for the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, SDAP) was a Marxist socialist political party in the North German Confederation during unification.

Founded in Eisenach in 1869, the SDAP e ...

.

Brussels

The nation of Belgium, founded in 1830, was endowed with one of the most liberal constitutions in Europe and functioned as refuge for progressives from other countries. From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx lived in

The nation of Belgium, founded in 1830, was endowed with one of the most liberal constitutions in Europe and functioned as refuge for progressives from other countries. From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx lived in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, spending much of their time organising the city's German workers. Shortly after their arrival, they contacted and joined the underground German Communist League. The Communist League was the successor organisation to the old League of the Just which had been founded in 1837, but had recently disbanded. Influenced by Wilhelm Weitling

Wilhelm Christian Weitling (October 5, 1808 – January 25, 1871) was a German tailor, inventor, radical political activist and one of the first theorists of communism. Weitling gained fame in Europe as a social theorist before he emigrated t ...

, the Communist League was an international society of proletarian revolutionaries with branches in various European cities.

The Communist League also had contacts with the underground conspiratorial organisation of Louis Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui (; 8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Biography Early life, political activity and first imprisonment (1805–1848)

Bla ...

. Many of Marx's and Engels's current friends became members of the Communist League. Old friends like Georg Friedrich Herwegh, who had worked with Marx on the ''Rheinsche Zeitung'', Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, writer and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of '' Lied ...

, the famous poet, a young physician by the name of Roland Daniels, Heinrich Bürgers

Johann Heinrich Georg Bürgers (21 June 1820, Cologne – 10 December 1878, Berlin) was a German journalist and an editor of the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung'' He became a member of the Communist League and, in 1850, he became a member of the League ...

and August Herman Ewerbeck

August Hermann Ewerbeck (12 November 1816 – 4 November 1860), known by his middle name of Hermann, was a pioneer socialist political activist, writer, and translator. A physician by vocation and a German by birth, Ewerbeck is best remembered as a ...

all maintained their contacts with Marx and Engels in Brussels. Georg Weerth

Georg Ludwig Weerth (17 February 1822 – 30 July 1856) was a German writer and poet. Weerth's poems celebrated the solidarity of the working class in its fight for liberation from exploitation and oppression. He was a friend and companio ...

, who had become a friend of Engels in England in 1843, now settled in Brussels. Carl Wallau and Stephen Born (real name Simon Buttermilch) were both German immigrant typesetters who settled in Brussels to help Marx and Engels with their Communist League work. Marx and Engels made many new important contacts through the Communist League. One of the first was Wilhelm Wolff, who was soon to become one of Marx's and Engels's closest collaborators. Others were Joseph Weydemeyer

Joseph Arnold Weydemeyer (February 2, 1818, Münster – August 26, 1866, St. Louis, Missouri) was a military officer in the Kingdom of Prussia and the United States as well as a journalist, politician and Marxist revolutionary.

At first a suppo ...

and Ferdinand Freiligrath Ferdinand Freiligrath (17 June 1810 – 18 March 1876) was a German poet, translator and liberal agitator, who is considered part of the Young Germany movement.

Life

Freiligrath was born in Detmold, Principality of Lippe. His father was a teacher. ...

, a famous revolutionary poet. While most of the associates of Marx and Engels were German immigrants living in Brussels, some of their new associates were Belgians. Phillipe Gigot, a Belgian philosopher and Victor Tedesco

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* Victor (1951 film), ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* Victor (1993 film), ...

, a lawyer from Liège, both joined the Communist League. Joachim Lelewel

Joachim Lelewel (22 March 1786 – 29 May 1861) was a Polish historian, geographer, bibliographer, polyglot and politician.

Life

Born in Warsaw to a Polonized German family, Lelewel was educated at the Imperial University of Vilna, where in 18 ...

a prominent Polish historian and participant in the Polish uprising of 1830–1831 was also a frequent associate.

The Communist League commissioned Marx and Engels to write a pamphlet explaining the principles of communism. This became the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Comm ...

'', better known as ''The Communist Manifesto''. It was first published on 21 February 1848 and ends with the world-famous phrase: "Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletariat have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working Men of All Countries, Unite!"

Engels's mother wrote in a letter to him of her concerns, commenting that he had "really gone too far" and "begged" him "to proceed no further".Elisabeth Engels's letter contained at No. 6 of the Appendix, ''Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 38'' (International Publishers: New York, 1982) pp. 540–541. She further stated:You have paid more heed to other people, to strangers, and have taken no account of your mother's pleas. God alone knows what I have felt and suffered of late. I was trembling when I picked up the newspaper and saw therein that a warrant was out for my son's arrest.

Return to Prussia

There was a revolution in France in 1848 that soon spread to other Western European countries. These events caused Engels and Marx to return to their homeland of the Kingdom of Prussia, specifically to the city ofCologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

. While living in Cologne, they created and served as editors for a new daily newspaper called the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Organ der Demokratie'' ("New Rhenish Newspaper: Organ of Democracy") was a German daily newspaper, published by Karl Marx in Cologne between 1 June 1848 and 19 May 1849. It is recognised by historians as one of the ...

''. Besides Marx and Engels, other frequent contributors to the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung'' included Karl Schapper

Karl Friedrich Schapper (December 30, 1812, Weinbach – April 28, 1870, London) was a German socialist and labour leader. He was one of the pioneers of the labour movement in Germany and an early associate of Wilhelm Weitling and Karl Marx.

Youn ...

, Wilhelm Wolff, Ernst Dronke

Ernst Andreas Dominicus Dronke (17 August 1822, Koblenz – 2 November 1891, Liverpool) was a German writer and journalist. Because of his philosophical beliefs, Dronke became a "true socialist". Later he became a member of the Communist League a ...

, Peter Nothjung, Heinrich Bürgers

Johann Heinrich Georg Bürgers (21 June 1820, Cologne – 10 December 1878, Berlin) was a German journalist and an editor of the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung'' He became a member of the Communist League and, in 1850, he became a member of the League ...

, Ferdinand Wolff

Ferdinand Wolff (7 November 1812 – 8 March 1895) was a German journalist by profession and a proletarian revolutionary. He joined the Communist League and became an editor of the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung'' in 1848 and 1849. He was a close frie ...

and Carl Cramer. Friedrich Engels's mother, herself, gives unwitting witness to the effect of the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung'' on the revolutionary uprising in Cologne in 1848. Criticising his involvement in the uprising she states in a 5 December 1848 letter to Friedrich that "nobody, ourselves included, doubted that the meetings at which you and your friends spoke, and also the language of ''(Neue) Rh.Z.'' were largely the cause of these disturbances."Elisabeth Engels's letter to Friedrich Engels contained at No. 8 of the Appendix in the ''Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 38'', p. 543.

Engels's parents hoped that young Engels would "decide to turn to activities other than those which you have been pursuing in recent years and which have caused so much distress". At this point, his parents felt the only hope for their son was to emigrate to America and start his life over. They told him that he should do this or he would "cease to receive money from us"; however, the problem in the relationship between Engels and his parents was worked out without Engels having to leave England or being cut off from financial assistance from his parents. In July 1851, Engels's father arrived to visit him in Manchester, England. During the visit, his father arranged for Engels to meet Peter Ermen of the office of ''Ermen & Engels'', to move to Liverpool and to take over sole management of the office in Manchester.

In 1849, Engels travelled to the Kingdom of Bavaria for the Baden and Palatinate revolutionary uprising, an even more dangerous involvement. Starting with an article called "The Magyar Struggle", written on 8 January 1849, Engels, himself, began a series of reports on the Revolution and War for Independence of the newly founded Hungarian Republic. Engels's articles on the Hungarian Republic became a regular feature in the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung'' under the heading "From the Theatre of War"; however, the newspaper was suppressed during the June 1849 Prussian coup d'état. After the coup, Marx lost his Prussian citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

, was deported and fled to Paris and then London. Engels stayed in Prussia and took part in an armed uprising in South Germany as an aide-de-camp in the volunteer corps of August Willich

August Willich (November 19, 1810 – January 22, 1878), born Johann August Ernst von Willich, was a military officer in the Prussian Army and a leading early proponent of communism in Germany. In 1847 he discarded his title of nobility. He later ...

. Engels also brought two cases of rifle cartridges with him when he went to join the uprising in Elberfeld

Elberfeld is a municipal subdivision of the German city of Wuppertal; it was an independent town until 1929.

History

The first official mentioning of the geographic area on the banks of today's Wupper River as "''elverfelde''" was in a docu ...

on 10 May 1849. Later when Prussian troops came to Kaiserslautern to suppress an uprising there, Engels joined a group of volunteers under the command of August Willich, who were going to fight the Prussian troops. When the uprising was crushed, Engels was one of the last members of Willich's volunteers to escape by crossing the Swiss border. Marx and others became concerned for Engels's life until they finally heard from him.

Engels travelled through Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

as a refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

and eventually made it to safety in England. On 6 June 1849 Prussian authorities issued an arrest warrant for Engels which contained a physical description as "height: 5 feet 6 inches; hair: blond; forehead: smooth; eyebrows: blond; eyes: blue; nose and mouth: well proportioned; beard: reddish; chin: oval; face: oval; complexion: healthy; figure: slender. Special characteristics: speaks very rapidly and is short-sighted". As to his "short-sightedness", Engels admitted as much in a letter written to Joseph Weydemeyer on 19 June 1851 in which he says he was not worried about being selected for the Prussian military because of "my eye trouble, as I have now found out once and for all which renders me completely unfit for active service of any sort". Once he was safe in Switzerland, Engels began to write down all his memories of the recent military campaign against the Prussians. This writing eventually became the article published under the name "The Campaign for the German Imperial Constitution".

Back in Britain

To help Marx with '' Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-ökonomische Revue'', the new publishing effort in London, Engels sought ways to escape the continent and travel to London. On 5 October 1849, Engels arrived in the Italian port city of Genoa. There, Engels booked passage on the English schooner, ''Cornish Diamond'' under the command of a Captain Stevens. The voyage across the western Mediterranean, around the Iberian Peninsula by sailing schooner took about five weeks. Finally, the ''Cornish Diamond'' sailed up the River Thames to London on 10 November 1849 with Engels on board.

Upon his return to Britain, Engels re-entered the Manchester company in which his father held shares to support Marx financially as he worked on ''

To help Marx with '' Neue Rheinische Zeitung Politisch-ökonomische Revue'', the new publishing effort in London, Engels sought ways to escape the continent and travel to London. On 5 October 1849, Engels arrived in the Italian port city of Genoa. There, Engels booked passage on the English schooner, ''Cornish Diamond'' under the command of a Captain Stevens. The voyage across the western Mediterranean, around the Iberian Peninsula by sailing schooner took about five weeks. Finally, the ''Cornish Diamond'' sailed up the River Thames to London on 10 November 1849 with Engels on board.

Upon his return to Britain, Engels re-entered the Manchester company in which his father held shares to support Marx financially as he worked on ''Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in Historical mater ...

''. Unlike his first period in England (1843), Engels was now under police surveillance. He had "official" homes and "unofficial homes" all over Salford, Weaste and other inner-city Manchester districts where he lived with Mary Burns under false names to confuse the police. Little more is known, as Engels destroyed over 1,500 letters between himself and Marx after the latter's death so as to conceal the details of their secretive lifestyle.

Despite his work at the mill, Engels found time to write a book on Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

, the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

and the 1525 revolutionary war of the peasants, entitled ''The Peasant War in Germany

''The Peasant War in Germany'' (German: ''Der deutsche Bauernkrieg'') by Friedrich Engels is a short account of the early-16th-century uprisings known as the German Peasants' War (1524–1525). It was written by Engels in London during the summ ...

''. He also wrote a number of newspaper articles including "The Campaign for the German Imperial Constitution" which he finished in February 1850 and "On the Slogan of the Abolition of the State and the German 'Friends of Anarchy'" written in October 1850. In April 1851, he wrote the pamphlet "Conditions and Prospects of a War of the Holy Alliance against France".

Marx and Engels denounced Louis Bonaparte

Louis Napoléon Bonaparte (born Luigi Buonaparte; 2 September 1778 – 25 July 1846) was a younger brother of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French. He was a monarch in his own right from 1806 to 1810, ruling over the Kingdom of Holland (a French cl ...

when he carried out a coup against the French government and made himself president for life on 2 December 1851. In condemning this action, Engels wrote to Marx on 3 December 1851, characterising the coup as "comical"Friedrich Engels's letter to Karl Marx dated 3 December 1851 contained in the "Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Volume 38", p. 503. and referred to it as occurring on "the 18th Brumaire", the date of Napoleon I's coup of 1799 according to the French Republican Calendar. Marx was later to incorporate this comically ironic characterisation of Louis Bonaparte's coup into his essay about the coup. Indeed, Marx even called the essay ''The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

''The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon'' (german: italic=yes, Der 18te Brumaire des Louis Napoleon) is an essay written by Karl Marx between December 1851 and March 1852, and originally published in 1852 in ''Die Revolution'', a German mo ...

'' again using Engels's suggested characterisation. Marx also borrowed Engels' characterisation of Hegel's notion of the World Spirit that history occurred twice, "once as a tragedy and secondly as a farce" in the first paragraph of his new essay.

Meanwhile, Engels started working at the mill owned by his father in Manchester as an office clerk, the same position he held in his teens while in Germany where his father's company was based. Engels worked his way up to become a partner of the firm in 1864. Five years later, Engels retired from the business and could focus more on his studies. At this time, Marx was living in London but they were able to exchange ideas through daily correspondence. One of the ideas that Engels and Marx contemplated was the possibility and character of a potential revolution in the Russias. As early as April 1853, Engels and Marx anticipated an "aristocratic-bourgeois revolution in Russia which would begin in "St. Petersburg with a resulting civil war in the interior". The model for this type of aristocratic-bourgeois revolution in Russia against the autocratic Tsarist government in favour of a constitutional government had been provided by the Decembrist Revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

of 1825.

Although an unsuccessful revolt against the Tsarist government in favour of a constitutional government, both Engels and Marx anticipated a bourgeois revolution in Russia would occur which would bring about a bourgeois stage in Russian development to precede a communist stage. By 1881, both Marx and Engels began to contemplate a course of development in Russia that would lead directly to the communist stage without the intervening bourgeois stage. This analysis was based on what Marx and Engels saw as the exceptional characteristics of the Russian village commune or obshchina

Obshchina ( rus, община, p=ɐpˈɕːinə, literally "commune") or mir (russian: мир, literally "society", among other meanings), or selskoye obshchestvo (russian: сельское общество, literally "rural community", official ...

. While doubt was cast on this theory by Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (; rus, Гео́ргий Валенти́нович Плеха́нов, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revoluti ...

, Plekhanov's reasoning was based on the first edition of ''Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in Historical mater ...

'' (1867) which predated Marx's interest in Russian peasant communes by two years. Later editions of the text demonstrate Marx's sympathy for the argument of Nikolay Chernyshevsky

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky ( – ) was a Russian literary and social critic, journalist, novelist, democrat, and socialist philosopher, often identified as a utopian socialist and leading theoretician of Russian nihilism. He was t ...

, that it should be possible to establish socialism in Russia without an intermediary bourgeois stage provided that the peasant commune were used as the basis for the transition.

In 1870, Engels moved to London where he and Marx lived until Marx's death in 1883. Engels's London home from 1870 to 1894 was at 122 Regent's Park Road. In October 1894 he moved to 41 Regent's Park Road, Primrose Hill

Primrose Hill is a Grade II listed public park located north of Regent's Park in London, England, first opened to the public in 1842.Mills, A., ''Dictionary of London Place Names'', (2001) It was named after the natural hill in the centre of ...

, NW1, where he died the following year.

Marx's first London residence was a cramped apartment at 28 Dean Street

Dean Street is a street in Soho, central London, running from Oxford Street south to Shaftesbury Avenue.

Historical figures and places

In 1764 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, then a young boy, gave a recital at 21 Dean Street.

Admiral Nelson stayed ...

, Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

. From 1856, he lived at 9 Grafton Terrace, Kentish Town

Kentish Town is an area of northwest London, England in the London Borough of Camden, immediately north of Camden Town. Less than four miles north of central London, Kentish Town has good transport connections and is situated close to the ope ...

, and then in a tenement at 41 Maitland Park Road in Belsize Park

Belsize Park is an affluent residential area of Hampstead in the London Borough of Camden (the inner north-west of London), England.

The residential streets are lined with mews houses and Georgian and Victorian villas. Some nearby localities ar ...

from 1875 until his death in March 1883.

Mary Burns suddenly died of heart disease in 1863, after which Engels became close with her younger sister Lydia ("Lizzie

Lizzie or Lizzy is a nickname for Elizabeth or Elisabet, often given as an independent name in the United States, especially in the late 19th century.

Lizzie can also be the shortened version of Lizeth, Lissette or Lizette.

People

* Elizabeth I ...

"). They lived openly as a couple in London and married on 11 September 1878, hours before Lizzie's death.

Later years

Later in their life, both Marx and Engels came to argue that in some countries workers might be able to achieve their aims through peaceful means. In following this, Engels argued that socialists were evolutionists, although they remained committed tosocial revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political syst ...

. Similarly, Tristram Hunt

Tristram Julian William Hunt, (born 31 May 1974) is a British historian, broadcast journalist and former politician who has been Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum since 2017. He served as the Labour Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke ...

argues that Engels was sceptical of "top-down revolutions" and later in life advocated "a peaceful, democratic road to socialism". Engels also wrote in his introduction to the 1891 edition of Marx's ''The Class Struggles in France

''The'' () is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite ...

'' that " bellion in the old style, street fighting with barricades, which decided the issue everywhere up to 1848, was to a considerable extent obsolete",Kellogg, Paul (Summer 1991). "Engels and the Roots of 'Revisionism': A Re-Evaluation". ''Science & Society''. Guilford Press. 55 (2): 158–174. . although some such as David W. Lowell empashised their cautionary and tactical meaning, arguing that "Engels questions only rebellion 'in the old style', that is, insurrection: he does not renounce revolution. The reason for Engels' caution is clear: he candidly admits that ultimate victory for any insurrection is rare, simply on military and tactical grounds".

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Marx's ''The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between reformists

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

and revolutionaries

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist

Gradualism, from the Latin ''gradus'' ("step"), is a hypothesis, a theory or a tenet assuming that change comes about gradually or that variation is gradual in nature and happens over time as opposed to in large steps. Uniformitarianism, incrementa ...

and evolutionary socialist

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German Social democracy, social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl ...

measures while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a goal. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the revisionists.Steger, Manfred B. (1999). "Friedrich Engels and the Origins of German Revisionism: Another Look". In Carver, Terrell; Steger, Manfred B. (eds.). ''Engels After Marx''. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University. p. 182. . Engels's statements in the French newspaper ''Le Figaro'', in which he wrote that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly changing social phenomena, and argued that this made "us socialists all evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was gravitating towards evolutionary socialism. Engels also argued that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to power that he predicted could bring "social democracy

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

into power as early as 1898". Engels's stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion. Marxist revisionist Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl Marx and Friedric ...

interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels's stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolut ...

. Engels was deeply distressed when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of ''The Class Struggles in France'' had been edited by Bernstein and orthodox Marxist

Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxist thought that emerged after the death of Karl Marx (1818–1883) and which became the official philosophy of the majority of the socialist movement as represented in the Second International until the Firs ...

Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels in ...

in a manner which left the impression that he had become a proponent of a peaceful road to socialism. On 1 April 1895, four months before his death, Engels responded to Kautsky:

I was amazed to see today in the ''Vorwärts'' an excerpt from my 'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of legalityAfter Marx's death, Engels devoted much of his remaining years to editing Marx's unfinished volumes of ''t all costs T, or t, is the twentieth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''. It is deri ...Which is all the more reason why I should like it to appear in its entirety in the ''Neue Zeit'' in order that this disgraceful impression may be erased. I shall leave Liebknecht in no doubt as to what I think about it and the same applies to those who, irrespective of who they may be, gave him this opportunity of perverting my views and, what's more, without so much as a word to me about it.

Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in Historical mater ...

''; however, he also contributed significantly in other areas. Engels made an argument using anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

evidence of the time to show that family structures changed over history, and that the concept of monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a form of Dyad (sociology), dyadic Intimate relationship, relationship in which an individual has only one Significant other, partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (Monogamy#Serial monogamy, ...

marriage came from the necessity within class society for men to control women to ensure their own children would inherit their property. He argued a future communist society would allow people to make decisions about their relationships free of economic constraints. One of the best examples of Engels's thoughts on these issues are in his work ''The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

''The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State: in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan'' (german: Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigenthums und des Staats) is an 1884 philosophical treatise by Friedrich Engels. It is p ...

''. On 5 August 1895, Engels died of throat cancer in London, aged 74. Following cremation at Woking Crematorium

Woking Crematorium is a crematorium in Woking, a large town in the west of Surrey, England. Established in 1878, it was the first custom-built crematorium in the United Kingdom and is closely linked to the history of cremation in the UK.

Locat ...

, his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head

Beachy Head is a chalk headland in East Sussex, England. It is situated close to Eastbourne, immediately east of the Seven Sisters.

Beachy Head is located within the administrative area of Eastbourne Borough Council which owns the land, formin ...

, near Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the la ...

, as he had requested. He left a considerable estate to Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl Marx and Friedric ...

and Louise Freyberger (wife of Ludwig Freyberger), valued for probate at £25,265 0s. 11d, equivalent to £ in .

Personality

Engels's interests included poetry,

Engels's interests included poetry, fox hunting

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase and, if caught, the killing of a fox, traditionally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds. A group of unarmed followers, led by a "master of foxhounds" (or "master of ho ...

and hosting regular Sunday parties for London's left-wing intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

where, as one regular put it, "no one left before two or three in the morning". His stated personal motto was "take it easy" while "jollity" was listed as his favourite virtue.

Of Engels's personality and appearance, Robert Heilbroner

Robert L. Heilbroner (March 24, 1919 – January 4, 2005) was an American economist and historian of economic thought. The author of some 20 books, Heilbroner was best known for ''The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times and Ideas of the Great ...

described him in ''The Worldly Philosophers'' as "tall and rather elegant, he had the figure of a man who liked to fence and to ride to hounds and who had once swum the Weser River four times without a break" as well as having been "gifted with a quick wit and facile mind" and of a gay temperament, being able to "stutter in twenty languages". He had a great enjoyment of wine and other "bourgeois pleasures". Engels favoured forming romantic relationships with that of the proletariat and found a long-term partner in a working-class woman named Mary Burns

Mary Burns (29 September 1821 – 7 January 1863)Whitfield, Roy (1988) ''Friedrich Engels in Manchester'', Working Class Movement Library, was a working-class Irish woman, best known as the lifelong partner of Friedrich Engels.

Burns lived in ...

, although they never married. After her death, Engels was romantically involved with her younger sister Lydia Burns

Lydia "Lizzie" Burns (6 August 1827 – 12 September 1878 in London) was a Working class, working-class Irish people, Irish woman, the wife of Friedrich Engels.

Lizzie Burns was a daughter of Michael Burns or Byrne, a Dyeing, dyer in a cotton m ...

.

Historian and former Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

MP Tristram Hunt

Tristram Julian William Hunt, (born 31 May 1974) is a British historian, broadcast journalist and former politician who has been Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum since 2017. He served as the Labour Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke ...

, author of ''The Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels'', argues that Engels "almost certainly was, in other words, the kind of man Stalin would have had shot". Hunt sums up the disconnect between Engels's personality and the Soviet Union which later utilised his works, stating:

As to the religious persuasion attributable to Engels, Hunt writes:

Engels was a polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingualism, monolingual speakers in the World population, world's pop ...

and was able to write and speak in numerous languages, including Russian, Italian, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish, Polish, French, English, German and the Milanese dialect

Milanese (endonym in traditional orthography , ') is the central variety of the Western dialect of the Lombard language spoken in Milan, the rest of its metropolitan city, and the northernmost part of the province of Pavia. Milanese, due to t ...

.

Legacy

In his biography of Engels,Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

wrote: "After his friend Karl Marx (who died in 1883), Engels was the finest scholar and teacher of the modern proletariat in the whole civilised world. ..In their scientific works, Marx and Engels were the first to explain that socialism is not the invention of dreamers, but the final aim and necessary result of the development of the productive forces in modern society. All recorded history hitherto has been a history of class struggle, of the succession of the rule and victory of certain social classes over others." According to Paul Kellogg

Paul Underwood Kellogg (September 30, 1879 – November 1, 1958) was an American journalist and social reformer. He died at 79 in New York on November 1, 1958.

Life

He was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1879. After working as a journalist he m ...

, there is "some considerable controversy" regarding "the place of Frederick Engels in the canon of 'classical Marxism

Classical Marxism refers to the economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as contrasted with later developments in Marxism, especially Marxism–Leninism.

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (5 May 1818, ...

'". While some such as Terrell Carver

Terrell Foster Carver (born 4 September 1946) is a Professor of Political Theory at the University of Bristol.

Career

Carver was born in Boise, Idaho. After receiving his B.A. from Columbia University in 1968, Carver went on to study in Engla ...

dispute "Engels' claim that Marx agreed with the views put forward in Engels' major theoretical work, ''Anti-Dühring''", others such as E. P. Thompson "identified a tendency to make 'old Engels into a whipping boy, and to impugn him any sign that once chooses to impugn subsequent Marxsisms'".

Tristram Hunt

Tristram Julian William Hunt, (born 31 May 1974) is a British historian, broadcast journalist and former politician who has been Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum since 2017. He served as the Labour Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke ...

argues that Engels has become a convenient scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designate ...

, too easily blamed for the state crimes of Communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

s such as China, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and those in Africa and Southeast Asia, among others. Hunt writes that "Engels is left holding the bag of 20th century ideological extremism" while Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

"is rebranded as the acceptable, post–political seer of global capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

". Hunt largely exonerates Engels, stating that " no intelligible sense can Engels or Marx bear culpability for the crimes of historical actors carried out generations later, even if the policies were offered up in their honor". Andrew Lipow describes Marx and Engels as "the founders of modern revolutionary democratic socialism".

While admitting the distance between Marx and Engels on one hand and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

on the other, some writers such as Robert Service are less charitable, noting that the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

predicted the oppressive potential of their ideas, arguing that " is a fallacy that Marxism's flaws were exposed only after it was tried out in power. .. arx and Engelswere centralisers. While talking about 'free associations of producers', they advocated discipline and hierarchy". Paul Thomas, of the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, claims that while Engels had been the most important and dedicated facilitator and diffuser of Marx's writings, he significantly altered Marx's intents as he held, edited and released them in a finished form and commentated on them. Engels attempted to fill gaps in Marx's system and extend it to other fields. In particular, Engels is said to have stressed historical materialism

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

, assigning it a character of scientific discovery and a doctrine, forming Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

as such. A case in point is ''Anti-Dühring

''Anti-Dühring'' (german: Herrn Eugen Dührings Umwälzung der Wissenschaft, "Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science") is a book by Friedrich Engels, first published in German in 1878. It had previously been serialised in the newspaper ''V ...

'' which both supporters and detractors of socialism treated as an encompassing presentation of Marx's thought. While in his extensive correspondence with German socialists Engels modestly presented his own secondary place in the couple's intellectual relationship and always emphasised Marx's outstanding role, Russian communists such as Lenin raised Engels up with Marx and conflated their thoughts as if they were necessarily congruous. Soviet Marxists then developed this tendency to the state doctrine of dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a philosophy of science, history, and nature developed in Europe and based on the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxist dialectics, as a materialist philosophy, emphasizes the importance of real-world con ...

.

Since 1931, Engels has had a Russian city named after him—

Since 1931, Engels has had a Russian city named after him—Engels, Saratov Oblast

Engels ( rus, Э́нгельс, p=ˈɛnɡʲɪlʲs), formerly known as Pokrovsk and Kosakenstadt, is a city in Saratov Oblast, Russia. It is a port located on the Volga River across from Saratov, the administrative center of the oblast, and is co ...

. It served as the capital of the Volga German Republic

The Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (german: Autonome Sozialistische Sowjetrepublik der Wolgadeutschen; russian: Автономная Советская Социалистическая Республика Немцев По� ...

within Soviet Russia