Frankish Christianity on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman

Chlodio's successors are obscure figures, but what can be certain is that Childeric I, possibly his grandson, ruled a Salian kingdom from

Chlodio's successors are obscure figures, but what can be certain is that Childeric I, possibly his grandson, ruled a Salian kingdom from

Clovis's sons made their capitals near the Frankish heartland in northeastern Gaul. Theuderic I made his capital at

Clovis's sons made their capitals near the Frankish heartland in northeastern Gaul. Theuderic I made his capital at

In 561 Chlothar died and his realm was divided, in a replay of the events of fifty years prior, between his four sons, with the chief cities remaining the same. The eldest son, Charibert I, inherited the kingdom with its capital at Paris and ruled all of western Gaul. The second eldest, Guntram, inherited the old kingdom of the Burgundians, augmented by the lands of central France around the old capital of Orléans, which became his chief city, and most of Provence.

The rest of Provence, the Auvergne, and eastern Aquitaine were assigned to the third son, Sigebert I, who also inherited Austrasia with its chief cities of Reims and Metz. The smallest kingdom was that of Soissons, which went to the youngest son,

In 561 Chlothar died and his realm was divided, in a replay of the events of fifty years prior, between his four sons, with the chief cities remaining the same. The eldest son, Charibert I, inherited the kingdom with its capital at Paris and ruled all of western Gaul. The second eldest, Guntram, inherited the old kingdom of the Burgundians, augmented by the lands of central France around the old capital of Orléans, which became his chief city, and most of Provence.

The rest of Provence, the Auvergne, and eastern Aquitaine were assigned to the third son, Sigebert I, who also inherited Austrasia with its chief cities of Reims and Metz. The smallest kingdom was that of Soissons, which went to the youngest son,

During the joint reign of Chlothar and Dagobert, who have been called "the last ruling Merovingians", the Saxons, who had been loosely attached to Francia since the late 550s, rebelled under Berthoald, Duke of Saxony, and were defeated and reincorporated into the kingdom by the joint action of father and son. When Chlothar died in 628, Dagobert, in accordance with his father's wishes, granted a subkingdom to his younger brother Charibert II. This subkingdom, commonly called Aquitaine, was a new creation.

During the joint reign of Chlothar and Dagobert, who have been called "the last ruling Merovingians", the Saxons, who had been loosely attached to Francia since the late 550s, rebelled under Berthoald, Duke of Saxony, and were defeated and reincorporated into the kingdom by the joint action of father and son. When Chlothar died in 628, Dagobert, in accordance with his father's wishes, granted a subkingdom to his younger brother Charibert II. This subkingdom, commonly called Aquitaine, was a new creation.

Dagobert, in his dealings with the Saxons, Alemans, and Thuringii, as well as the

Dagobert, in his dealings with the Saxons, Alemans, and Thuringii, as well as the

In 673, Chlothar III died and some Neustrian and Burgundian magnates invited Childeric to become king of the whole realm, but he soon upset some Neustrian magnates and he was assassinated (675).

The reign of Theuderic III was to prove the end of the Merovingian dynasty's power.

Theuderic III succeeded his brother Chlothar III in Neustria in 673, but Childeric II of Austrasia displaced him soon thereafter—until he died in 675, and Theuderic III retook his throne. When Dagobert II died in 679, Theuderic received Austrasia as well and became king of the whole Frankish realm. Thoroughly Neustrian in outlook, he allied with his mayor

In 673, Chlothar III died and some Neustrian and Burgundian magnates invited Childeric to become king of the whole realm, but he soon upset some Neustrian magnates and he was assassinated (675).

The reign of Theuderic III was to prove the end of the Merovingian dynasty's power.

Theuderic III succeeded his brother Chlothar III in Neustria in 673, but Childeric II of Austrasia displaced him soon thereafter—until he died in 675, and Theuderic III retook his throne. When Dagobert II died in 679, Theuderic received Austrasia as well and became king of the whole Frankish realm. Thoroughly Neustrian in outlook, he allied with his mayor

Pepin reigned as an elected king. Although such elections happened infrequently, a general rule in Germanic law stated that the king relied on the support of his leading men. These men reserved the right to choose a new "kingworthy" leader out of the ruling clan if they felt that the old one could not lead them in profitable battle. While in later France the kingdom became hereditary, the kings of the later Holy Roman Empire proved unable to abolish the elective tradition and continued as elected rulers until the empire's formal end in 1806.

Pepin solidified his position in 754 by entering into an alliance with

Pepin reigned as an elected king. Although such elections happened infrequently, a general rule in Germanic law stated that the king relied on the support of his leading men. These men reserved the right to choose a new "kingworthy" leader out of the ruling clan if they felt that the old one could not lead them in profitable battle. While in later France the kingdom became hereditary, the kings of the later Holy Roman Empire proved unable to abolish the elective tradition and continued as elected rulers until the empire's formal end in 1806.

Pepin solidified his position in 754 by entering into an alliance with

Charlemagne had several sons, but only one survived him. This son, Louis the Pious, followed his father as the ruler of a united empire. But sole inheritance remained a matter of chance, rather than intent. When Louis died in 840, the Carolingians adhered to the custom of partible inheritance, and after a brief civil war between the three sons, they made an agreement in 843, the Treaty of Verdun, which divided the empire in three:

# Louis's eldest surviving son

Charlemagne had several sons, but only one survived him. This son, Louis the Pious, followed his father as the ruler of a united empire. But sole inheritance remained a matter of chance, rather than intent. When Louis died in 840, the Carolingians adhered to the custom of partible inheritance, and after a brief civil war between the three sons, they made an agreement in 843, the Treaty of Verdun, which divided the empire in three:

# Louis's eldest surviving son

Roman History

'. trans. by Roger Pearse. London: Bohn, 1862. * Procopius. ''

The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its Continuations

'. trans. by John Michael Wallace-Hadrill. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1960. * Fredegar.

Historia Epitomata

'. Woodruff, Jane Ellen. PhD Dissertation, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 1987. *

''Historia Francorum''.

*

Excerpts here

*

The Dukes in the Regnum Francorum, A.D. 550–751.

''Speculum'', Vol. 51, No 3 (July 1976), pp 381–410. *McKitterick, Rosamond. ''The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987''. London: Longman, 1983. . *Murray, Archibald C. and Goffart, Walter A. ''After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History''. 1999. *Nixon, C. E. V. and Rodgers, Barbara. ''In Praise of Later Roman Emperors''. Berkeley, 1994. * Laury Sarti, "Perceiving War and the Military in Early Christian Gaul (ca. 400–700 A.D.)" (= Brill's Series on the Early Middle Ages, 22), Leiden/Boston 2013, . * Schutz, Herbert. ''The Germanic Realms in Pre-Carolingian Central Europe, 400–750''. American University Studies, Series IX: History, Vol. 196. New York: Peter Lang, 2000. * Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. ''The Long-Haired Kings''. London: Butler & tanner Ltd, 1962. * Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. ''The Barbarian West''. London: Hutchinson, 1970.

TABLE. Capitals of the Frankish Kingdom according to the years, in 509 – 800

{{Authority control 480s establishments 840s disestablishments Barbarian kingdoms Former empires in Europe Germanic kingdoms States and territories established in the 480s States and territories disestablished in the 840s

barbarian kingdom

The barbarian kingdoms, also known as the post-Roman kingdoms, the western kingdoms or the early medieval kingdoms, were the states founded by various non-Roman, primarily Germanic, peoples in Western Europe and North Africa following the collap ...

in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks during late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. After the Treaty of Verdun in 843, West Francia became the predecessor of France, and East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

became that of Germany. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

era before its partition in 843.

The core Frankish territories inside the former Western Roman Empire were close to the Rhine and Meuse rivers in the north. After a period where small kingdoms interacted with the remaining Gallo-Roman institutions to their south, a single kingdom uniting them was founded by Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single kin ...

who was crowned King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic-speaking peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dukes and reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Merovingians, who con ...

in 496. His dynasty, the Merovingian dynasty, was eventually replaced by the Carolingian dynasty. Under the nearly continuous campaigns of Pepin of Herstal, Charles Martel, Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

, Charlemagne, and Louis the Pious—father, son, grandson, great-grandson and great-great-grandson—the greatest expansion of the Frankish empire was secured by the early 9th century, and was by this point dubbed the Carolingian Empire.

During the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties the Frankish realm was one large polity

A polity is an identifiable Politics, political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relation, social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize ...

subdivided into several smaller kingdoms, often effectively independent. The geography and number of subkingdoms varied over time, but a basic split between eastern and western domains persisted. The eastern kingdom was initially called Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

, centred on the Rhine and Meuse, and expanding eastwards into central Europe. Following the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the Frankish Realm was divided into three separate kingdoms: West Francia, Middle Francia and East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

. In 870, Middle Francia was partitioned again, with most of its territory being divided among West and East Francia, which would hence form the nuclei of the future Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire respectively, with West Francia (France) eventually retaining the choronym.

History

Origins

The term "Franks" emerged in the 3rd century AD, covering Germanic tribes who settled on the northern Rhine frontier of the Roman Empire, including the Bructeri, Ampsivarii, Chamavi,Chattuarii

The Chattuarii, also spelled Attoarii, were a Germanic tribe of the Franks. They lived originally north of the Rhine in the area of the modern border between Germany and the Netherlands, but then moved southwards in the 4th century, as a Frankis ...

and Salians. While all of them had a tradition of participating in the Roman military, the Salians were allowed to settle within the Roman Empire. In 358, having already been living in the ''civitas'' of Batavia for some time, Emperor Julian defeated the Chamavi and Salians, allowing the latter to settle further away from the border, in Toxandria.

Some of the early Frankish leaders, such as Flavius Bauto and Arbogast, were committed to the cause of the Romans, but other Frankish rulers, such as Mallobaudes

Mallobaudes or Mellobaudes was a 4th-century Frankish king who also held the Roman title of ''comes domesticorum''.

In 354 he was a ''tribunus armaturarum'' in the Roman army in Gaul, where he served under Silvanus, who usurped power in 355. Mall ...

, were active on Roman soil for other reasons. After the fall of Arbogastes, his son Arigius succeeded in establishing a hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

countship at Trier and after the fall of the usurper Constantine III Constantine III may refer to:

* Constantine III (Western Roman Emperor), self-proclaimed western Roman Emperor 407–411

* Heraclius Constantine, Byzantine Emperor in 641

* Constans II, Byzantine emperor 641–668, sometimes referred to under this ...

some Franks supported the usurper Jovinus (411). Jovinus was dead by 413, but the Romans found it increasingly difficult to manage the Franks within their borders.

The Frankish king Theudemer was executed by the sword, in c. 422.

Around 428, the king Chlodio, whose kingdom may have been in the '' civitas Tungrorum'' (with its capital in Tongeren), launched an attack on Roman territory and extended his realm as far as ''Camaracum'' (Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

) and the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

. Though Sidonius Apollinaris relates that Flavius Aetius defeated a wedding party of his people (c. 431), this period marks the beginning of a situation that would endure for many centuries: the Germanic Franks ruled over an increasing number of Gallo-Roman subjects.

The Merovingians, reputed to be relatives of Chlodio, arose from within the Gallo-Roman military, with Childeric and his son Clovis being called "King of the Franks" in the Gallo-Roman military, even before having any Frankish territorial kingdom. Once Clovis defeated his Roman competitor for power in northern Gaul, Syagrius, he turned to the kings of the Franks to the north and east, as well as other post-Roman kingdoms already existing in Gaul: Visigoths, Burgundians

The Burgundians ( la, Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; on, Burgundar; ang, Burgendas; grc-gre, Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and ...

, and Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

.

The original core territory of the Frankish kingdom later came to be known as Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

(the "eastern lands"), while the large Romanised Frankish kingdom in northern Gaul came to be known as Neustria.

Merovingian rise and decline, 481–687

Chlodio's successors are obscure figures, but what can be certain is that Childeric I, possibly his grandson, ruled a Salian kingdom from

Chlodio's successors are obscure figures, but what can be certain is that Childeric I, possibly his grandson, ruled a Salian kingdom from Tournai

Tournai or Tournay ( ; ; nl, Doornik ; pcd, Tornai; wa, Tornè ; la, Tornacum) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies southwest of Brussels on the river Scheldt. Tournai is part of Euromet ...

as a '' foederatus'' of the Romans. Childeric is chiefly important to history for bequeathing the Franks to his son Clovis

Clovis may refer to:

People

* Clovis (given name), the early medieval (Frankish) form of the name Louis

** Clovis I (c. 466 – 511), the first king of the Franks to unite all the Frankish tribes under one ruler

** Clovis II (c. 634 – c. 657), ...

, who began an effort to extend his authority over the other Frankish tribes and to expand their ''territorium'' south and west into Gaul. Clovis converted to Christianity and put himself on good terms with the powerful Church and with his Gallo-Roman subjects.

In a thirty-year reign (481–511) Clovis defeated the Roman general Syagrius and conquered the Kingdom of Soissons, defeated the Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

(Battle of Tolbiac

The Battle of Tolbiac was fought between the Franks, who were fighting under Clovis I, and the Alamanni, whose leader is not known. The date of the battle has traditionally been given as 496, though other accounts suggest it may either have been ...

, 496) and established Frankish hegemony over them. Clovis defeated the Visigoths ( Battle of Vouillé, 507) and conquered all of their territory north of the Pyrenees save Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

, and conquered the Bretons (according to Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florenti ...

) and made them vassals of Francia. He conquered most or all of the neighbouring Frankish tribes along the Rhine and incorporated them into his kingdom.

He also incorporated the various Roman military settlements ('' laeti'') scattered over Gaul: the Saxons of Bessin

Bessin () is an area in Normandy, France, corresponding to the territory of the Bajocasses, a Gallic tribe from whom Bayeux, its main town, takes its name.

History

The territory was annexed by the count of Rouen in 924.

The Bessin corresponds t ...

, the Britons and the Alans of Armorica and Loire valley or the Taifals of Poitou to name a few prominent ones. By the end of his life, Clovis ruled all of Gaul save the Gothic province of Septimania and the Burgundian kingdom in the southeast.

The Merovingians were a hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is a form of government and succession of power in which the throne passes from one member of a ruling family to another member of the same family. A series of rulers from the same family would constitute a dynasty.

It is h ...

. The Frankish kings adhered to the practice of partible inheritance: dividing their lands among their sons. Even when multiple Merovingian kings ruled, the kingdom—not unlike the late Roman Empire—was conceived of as a single realm ruled collectively by several kings and the turn of events could result in the reunification of the whole realm under a single king. The Merovingian kings ruled by divine right and their kingship was symbolised daily by their long hair and initially by their acclamation, which was carried out by raising the king on a shield in accordance with the ancient Germanic practice of electing a war-leader at an assembly of the warriors.

Clovis's sons

At the death of Clovis, his kingdom was divided territorially by his four adult sons in such a way that each son was granted a comparable portion of fiscal land, which was probably land once part of the Roman fisc, now seized by the Frankish government. Clovis's sons made their capitals near the Frankish heartland in northeastern Gaul. Theuderic I made his capital at

Clovis's sons made their capitals near the Frankish heartland in northeastern Gaul. Theuderic I made his capital at Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

, Chlodomer at Orléans, Childebert I at Paris, and Chlothar I

Chlothar I, sometime called "the Old" ( French: le Vieux), (died December 561) also anglicised as Clotaire, was a king of the Franks of the Merovingian dynasty and one of the four sons of Clovis I.

Chlothar's father, Clovis I, divided the kin ...

at Soissons. During their reigns, the Thuringii (532), Burgundes (534), and Saxons and Frisians

The Frisians are a Germanic ethnic group native to the coastal regions of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen and, in Germany, ...

(c. 560) were incorporated into the Frankish kingdom. The outlying trans-Rhenish tribes were loosely attached to Frankish sovereignty, and though they could be forced to contribute to Frankish military efforts, in times of weak kings they were uncontrollable and liable to attempt independence. The Romanised Burgundian kingdom, however, was preserved in its territoriality by the Franks and converted into one of their primary divisions, incorporating the central Gallic heartland of Chlodomer's realm with its capital at Orléans.

The fraternal kings showed only intermittent signs of friendship and were often in rivalry. On the early death of Chlodomer, his brother Chlothar had his young sons murdered in order to take a share of his kingdom, which was, in accordance with custom, divided between the surviving brothers. Theuderic died in 534, but his adult son Theudebert I was capable of defending his inheritance, which formed the largest of the Frankish subkingdoms and the kernel of the later kingdom of Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

.

Theudebert was the first Frankish king to formally sever his ties to the Byzantine Empire by striking gold coins with his own image on them and calling himself ''magnus rex'' (great king) because of his supposed suzerainty over peoples as far away as Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

. Theudebert interfered in the Gothic War Gothic War may refer to:

*Gothic War (248–253), battles and plundering carried out by the Goths and their allies in the Roman Empire.

*Gothic War (367–369), a war of Thervingi against the Eastern Roman Empire in which the Goths retreated to Mont ...

on the side of the Gepids and Lombards against the Ostrogoths, receiving the provinces of Raetia, Noricum, and part of Veneto.

Chlothar

His son and successor, Theudebald, was unable to retain them and on his death all of his vast kingdom passed to Chlothar, under whom, with the death of Childebert in 558, the entire Frankish realm was reunited under the rule of one king. In 561 Chlothar died and his realm was divided, in a replay of the events of fifty years prior, between his four sons, with the chief cities remaining the same. The eldest son, Charibert I, inherited the kingdom with its capital at Paris and ruled all of western Gaul. The second eldest, Guntram, inherited the old kingdom of the Burgundians, augmented by the lands of central France around the old capital of Orléans, which became his chief city, and most of Provence.

The rest of Provence, the Auvergne, and eastern Aquitaine were assigned to the third son, Sigebert I, who also inherited Austrasia with its chief cities of Reims and Metz. The smallest kingdom was that of Soissons, which went to the youngest son,

In 561 Chlothar died and his realm was divided, in a replay of the events of fifty years prior, between his four sons, with the chief cities remaining the same. The eldest son, Charibert I, inherited the kingdom with its capital at Paris and ruled all of western Gaul. The second eldest, Guntram, inherited the old kingdom of the Burgundians, augmented by the lands of central France around the old capital of Orléans, which became his chief city, and most of Provence.

The rest of Provence, the Auvergne, and eastern Aquitaine were assigned to the third son, Sigebert I, who also inherited Austrasia with its chief cities of Reims and Metz. The smallest kingdom was that of Soissons, which went to the youngest son, Chilperic I

Chilperic I (c. 539 – September 584) was the king of Neustria (or Soissons) from 561 to his death. He was one of the sons of the Frankish king Clotaire I and Queen Aregund.

Life

Immediately after the death of his father in 561, he en ...

. The kingdom Chilperic ruled at his death (584) became the nucleus of later Neustria.

This second fourfold division was quickly ruined by fratricidal wars, waged largely over the murder of Galswintha, the wife of Chilperic, allegedly by his mistress (and second wife) Fredegund. Galswintha's sister, the wife of Sigebert, Brunhilda, incited her husband to war and the conflict between the two queens continued to plague relations until the next century. Guntram sought to keep the peace, though he also attempted twice (585 and 589) to conquer Septimania from the Goths, but was defeated both times.

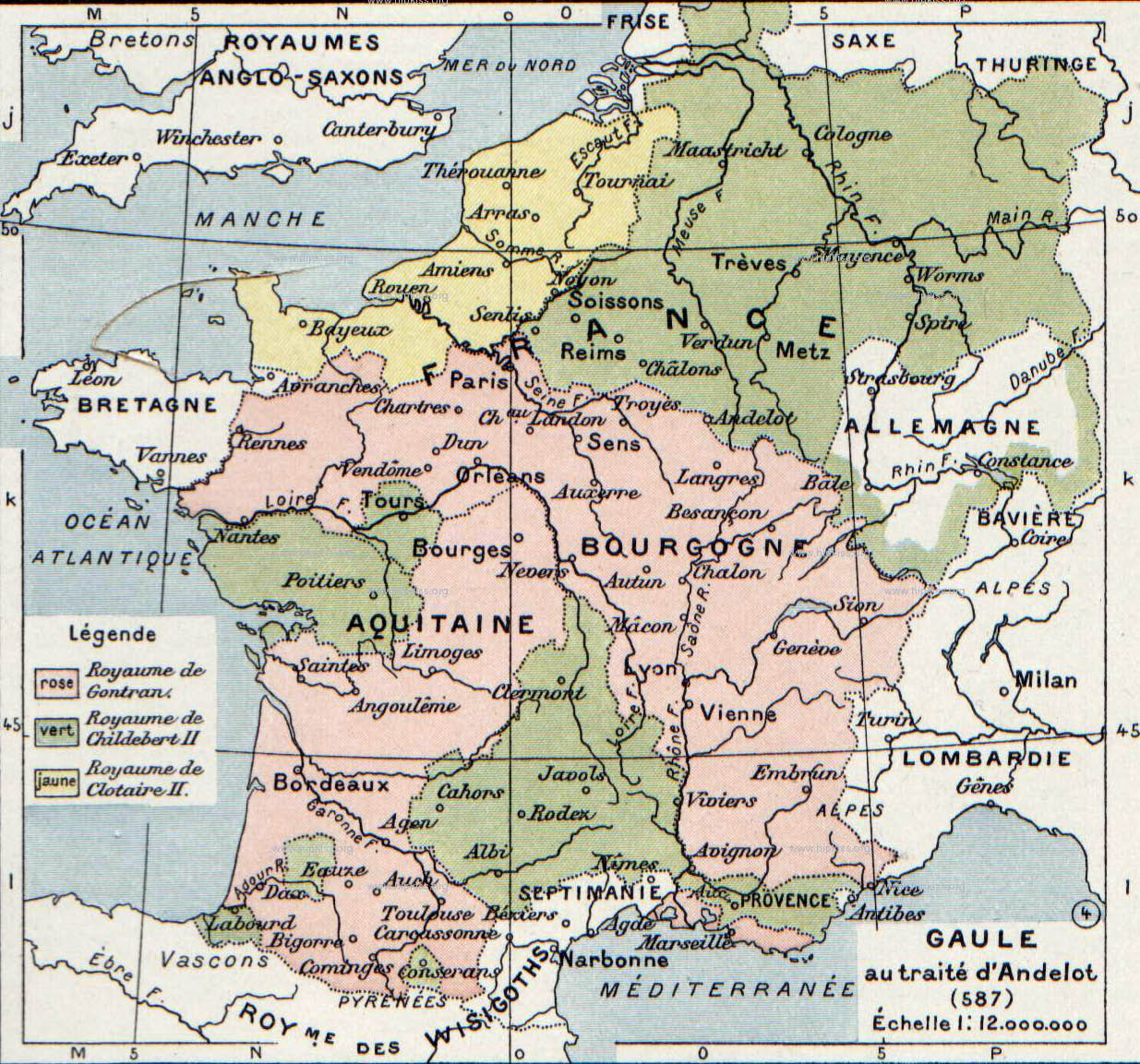

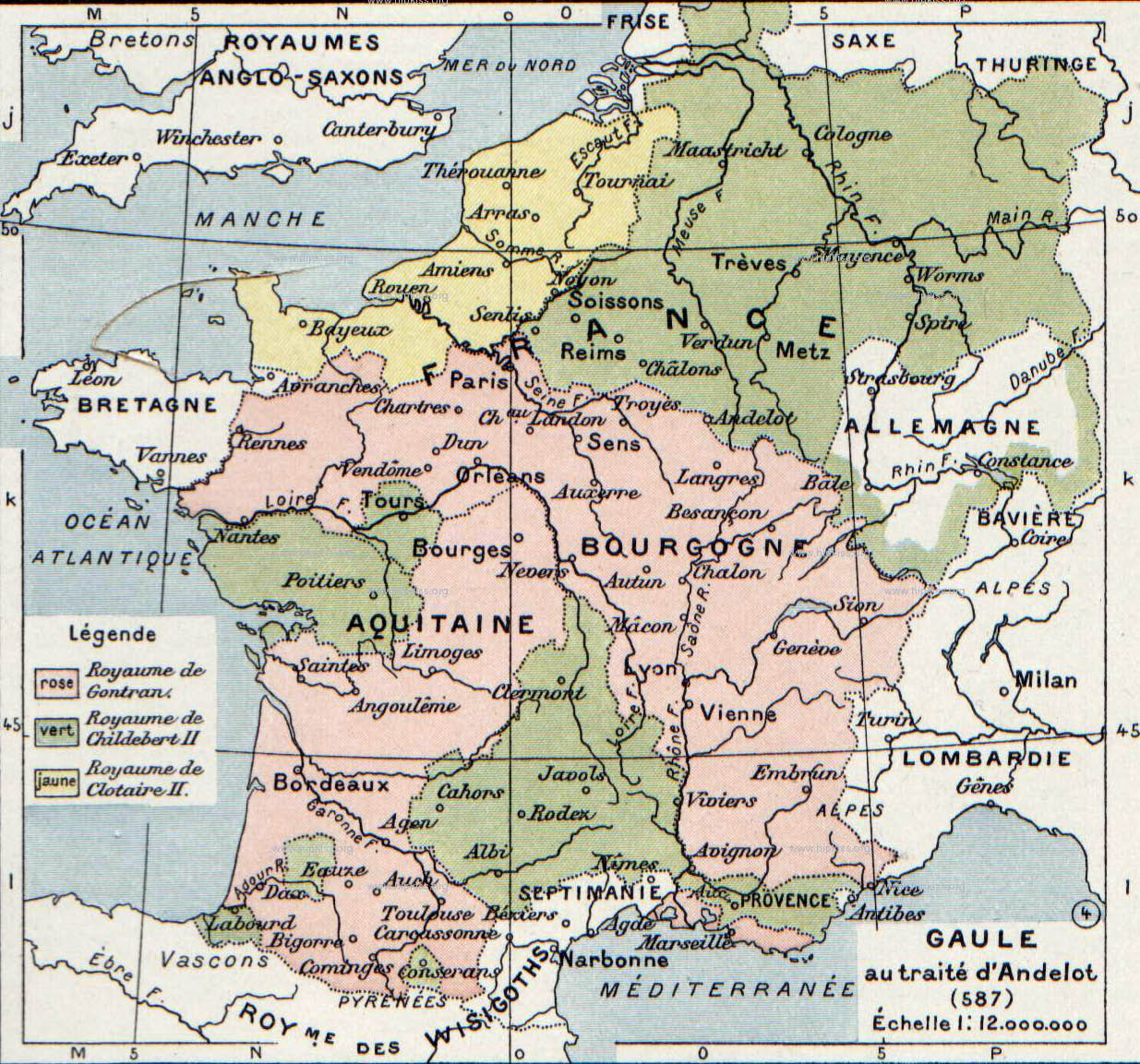

All the surviving brothers benefited at the death of Charibert, but Chilperic was also able to extend his authority during the period of war by bringing the Bretons to heel again. After his death, Guntram had to again force the Bretons to submit. In 587, the Treaty of Andelot

The Treaty of Andelot (or Pact of Andelot) was signed at Andelot-Blancheville in 587 between King Guntram of Burgundy and Queen Brunhilda of Austrasia. Based on the terms of the accord, Brunhilda agreed that Guntram adopt her son Childebert II a ...

—the text of which explicitly refers to the entire Frankish realm as ''Francia''—between Brunhilda and Guntram secured his protection of her young son Childebert II, who had succeeded the assassinated Sigebert (575). Together the territory of Guntram and Childebert was well over thrice as large as the small realm of Chilperic's successor, Chlothar II. During this period Francia took on the tripartite character it was to have throughout the rest of its history, being composed of Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy.

Francia split into Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy

When Guntram died in 592, Burgundy went to Childebert in its entirety, but he died in 595. His two sons divided the kingdom, with the elder Theudebert II taking Austrasia plus Childebert's portion of Aquitaine, while his younger brother Theuderic II inherited Burgundy and Guntram's Aquitaine. United, the brothers sought to remove their father's cousin Chlothar II from power and they did succeed in conquering most of his kingdom, reducing him to only a few cities, but they failed to capture him. In 599 they routed his forces at Dormelles and seized the Dentelin, but they then fell foul of each other and the remainder of their time on the thrones was spent in infighting, often incited by their grandmother Brunhilda, who, angered over her expulsion from Theudebert's court, convinced Theuderic to unseat him and kill him. In 612 he did and the whole realm of his father Childebert was once again ruled by one man. This was short-lived, however, as he died on the eve of preparing an expedition against Chlothar in 613, leaving a young son namedSigebert II :''See Sigeberht II of Essex for the Saxon ruler by that name.''

Sigebert II (601–613) or Sigisbert II, was the illegitimate son of Theuderic II, from whom he inherited the kingdoms of Burgundy and Austrasia in 613. However, he fell under the in ...

.

During their reigns, Theudebert and Theuderic campaigned successfully in Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

, where they had established the Duchy of Gascony and brought the Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Bas ...

to submission (602). This original Gascon conquest included lands south of the Pyrenees, namely Biscay and Gipuzkoa, but these were lost to the Visigoths in 612.

On the opposite end of his realm, the Alemanni had defeated Theuderic in a rebellion and the Franks were losing their hold on the trans-Rhenish tribes. In 610 Theudebert had extorted the Duchy of Alsace

The Duchy of Alsace ( la, Ducatus Alsacensi, ''Ducatum Elisatium''; german: Herzogtum Elsaß) was a large political subdivision of the Frankish Empire during the last century and a half of Merovingian rule. It corresponded to the territory of Al ...

from Theuderic, beginning a long period of conflict over which kingdom was to have the region of Alsace, Burgundy or Austrasia, which was only terminated in the late seventh century.

During the brief minority of Sigebert II, the office of the Mayor of the Palace, which had for sometime been visible in the kingdoms of the Franks, came to the fore in its internal politics, with a faction of nobles coalescing around the persons of Warnachar II, Rado, and Pepin of Landen, to give the kingdom over to Chlothar in order to remove Brunhilda, the young king's regent, from power. Warnachar was himself already the mayor of the palace of Austrasia, while Rado and Pepin were to find themselves rewarded with mayoral offices after Chlothar's coup succeeded and Brunhilda and the ten-year-old king were killed.

Rule of Chlothar II

Immediately after his victory, Chlothar II promulgated the Edict of Paris (614), which has generally been viewed as a concession to the nobility, though this view has come under recent criticism. The Edict primarily sought to guarantee justice and end corruption in government, but it also entrenched the regional differences between the three kingdoms of Francia and probably granted the nobles more control over judicial appointments. By 623 the Austrasians had begun to clamour for a king of their own, since Chlothar was so often absent from the kingdom and, because of his upbringing and previous rule in the Seine basin, was more or less an outsider there. Chlothar thus granted that his son Dagobert I would be their king and he was duly acclaimed by the Austrasian warriors in the traditional fashion. Nonetheless, though Dagobert exercised true authority in his realm, Chlothar maintained ultimate control over the whole Frankish kingdom. During the joint reign of Chlothar and Dagobert, who have been called "the last ruling Merovingians", the Saxons, who had been loosely attached to Francia since the late 550s, rebelled under Berthoald, Duke of Saxony, and were defeated and reincorporated into the kingdom by the joint action of father and son. When Chlothar died in 628, Dagobert, in accordance with his father's wishes, granted a subkingdom to his younger brother Charibert II. This subkingdom, commonly called Aquitaine, was a new creation.

During the joint reign of Chlothar and Dagobert, who have been called "the last ruling Merovingians", the Saxons, who had been loosely attached to Francia since the late 550s, rebelled under Berthoald, Duke of Saxony, and were defeated and reincorporated into the kingdom by the joint action of father and son. When Chlothar died in 628, Dagobert, in accordance with his father's wishes, granted a subkingdom to his younger brother Charibert II. This subkingdom, commonly called Aquitaine, was a new creation.

Dagobert I

Dagobert, in his dealings with the Saxons, Alemans, and Thuringii, as well as the

Dagobert, in his dealings with the Saxons, Alemans, and Thuringii, as well as the Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

beyond the borders of Francia, upon whom he tried to force tribute but who instead defeated him under their king Samo at the Battle of Wogastisburg in 631, made all the far eastern peoples subject to the court of Neustria and not of Austrasia. This, first and foremost, incited the Austrasians to request a king of their own from the royal household.

The subkingdom of Aquitaine corresponded to the southern half of the old Roman province of Aquitania and its capital was at Toulouse. The other cities of his kingdom were Cahors, Agen, Périgueux, Bordeaux, and Saintes; the duchy of Vasconia was also part of his allotment. Charibert campaigned successfully against the Basques, but after his death they revolted again (632). At the same time the Bretons rose up against Frankish suzerainty. The Breton leader Judicael Judicael or Judicaël is a Breton masculine given name. It may refer to:

* Saint Judicael (7th century), king of Domnonia and high king of Brittany

* Judicael, Duke of Brittany (9th century)

* Judicael Berengar (10th century), count of Rennes

* J ...

relented and made peace with the Franks and paid tribute after Dagobert threatened to lead an army against him (635). That same year Dagobert sent an army to subdue the Basques, which it did.

Meanwhile, Dagobert had Charibert's infant successor Chilperic assassinated and reunited the entire Frankish realm again (632), though he was forced by the strong Austrasian aristocracy to grant his own son Sigebert III to them as a subking in 633. This act was precipitated largely by the Austrasians' desire to be self-governing at a time when Neustrians dominated at the royal court. Chlothar had been the king at Paris for decades before becoming the king at Metz as well and the Merovingian monarchy was ever after him to be a Neustrian monarchy first and foremost.

Indeed, it is in the 640s that "Neustria" first appears in writing, its late appearance relative to "Austrasia" probably due to the fact that Neustrians (who formed the bulk of the authors of the time) called their region simply "Francia". ''Burgundia'' too defined itself in opposition to Neustria at about this time. However, it was the Austrasians, who had been seen as a distinct people within the realm since the time of Gregory of Tours, who were to make the most strident moves for independence.

The young Sigebert was dominated during his minority by the mayor, Grimoald the Elder, who convinced the childless king to adopt his own Merovingian-named son Childebert as his son and heir. After Dagobert's death in 639, the duke of Thuringia, Radulf, rebelled and tried to make himself king. He defeated Sigebert in what was a serious reversal for the ruling dynasty (640).

The king lost the support of many magnates while on campaign and the weakness of the monarchic institutions by that time are evident in his inability to effectively make war without the support of the magnates; in fact, he could not even provide his own bodyguard without the loyal aid of Grimoald and Adalgisel. He is often regarded as the first '' roi fainéant'': "do-nothing king", not insofar as he "did nothing", but insofar as he accomplished little.

Clovis II, Dagobert's successor in Neustria and Burgundy, which were thereafter attached yet ruled separately, was a minor for almost the whole of his reign. He was dominated by his mother Nanthild and the mayor of the Neustrian palace, Erchinoald. Erchinoald's successor, Ebroin

Ebroin (died 680 or 681) was the Frankish mayor of the palace of Neustria on two occasions; firstly from 658 to his deposition in 673 and secondly from 675 to his death in 680 or 681. In a violent and despotic career, he strove to impose the aut ...

, dominated the kingdom for the next fifteen years of near-constant civil war. On his death (656), Sigbert's son was shipped off to Ireland, while Grimoald's son Childebert reigned in Austrasia.

Ebroin eventually reunited the entire Frankish kingdom for Clovis's successor Chlothar III by killing Grimoald and removing Childebert in 661. However, the Austrasians demanded a king of their own again and Chlothar installed his younger brother Childeric II. During Chlothar's reign, the Franks had made an attack on northwestern Italy, but were driven off by Grimoald, King of the Lombards, near Rivoli.

Dominance of the mayors of the palace, 687–751

In 673, Chlothar III died and some Neustrian and Burgundian magnates invited Childeric to become king of the whole realm, but he soon upset some Neustrian magnates and he was assassinated (675).

The reign of Theuderic III was to prove the end of the Merovingian dynasty's power.

Theuderic III succeeded his brother Chlothar III in Neustria in 673, but Childeric II of Austrasia displaced him soon thereafter—until he died in 675, and Theuderic III retook his throne. When Dagobert II died in 679, Theuderic received Austrasia as well and became king of the whole Frankish realm. Thoroughly Neustrian in outlook, he allied with his mayor

In 673, Chlothar III died and some Neustrian and Burgundian magnates invited Childeric to become king of the whole realm, but he soon upset some Neustrian magnates and he was assassinated (675).

The reign of Theuderic III was to prove the end of the Merovingian dynasty's power.

Theuderic III succeeded his brother Chlothar III in Neustria in 673, but Childeric II of Austrasia displaced him soon thereafter—until he died in 675, and Theuderic III retook his throne. When Dagobert II died in 679, Theuderic received Austrasia as well and became king of the whole Frankish realm. Thoroughly Neustrian in outlook, he allied with his mayor Berchar

Berchar (also Berthar) was the mayor of the palace of Neustria and Kingdom of Burgundy, Burgundy from 686 to 688/689. He was the successor of Waratton, whose daughter Anstrude he had married.

Unlike Waratton, however, Berthar did not keep peace w ...

and made war on the Austrasian who had installed Dagobert II, Sigebert III's son, in their kingdom (briefly in opposition to Clovis III).

In 687 he was defeated by Pepin of Herstal, the Arnulfing mayor of Austrasia and the real power in that kingdom, at the Battle of Tertry

The Battle of Tertry was an important engagement in Merovingian Gaul between the forces of Austrasia under Pepin II on one side and those of Neustria and Burgundy on the other. It took place in 687 at Tertry, Somme, and the battle is presented as ...

and was forced to accept Pepin as sole mayor and ''dux et princeps Francorum'': " Duke and Prince of the Franks", a title which signifies, to the author of the '' Liber Historiae Francorum'', the beginning of Pepin's "reign". Thereafter the Merovingian monarchs showed only sporadically, in our surviving records, any activities of a non-symbolic and self-willed nature.

During the period of confusion in the 670s and 680s, attempts had been made to re-assert Frankish suzerainty over the Frisians, but to no avail. In 689, however, Pepin launched a campaign of conquest in Western Frisia (''Frisia Citerior'') and defeated the Frisian king Radbod near Dorestad, an important trading centre. All the land between the Scheldt and the Vlie was incorporated into Francia.

Then, circa 690, Pepin attacked central Frisia and took Utrecht. In 695 Pepin could even sponsor the foundation of the Archdiocese of Utrecht and the beginning of the conversion of the Frisians under Willibrord. However, Eastern Frisia (''Frisia Ulterior'') remained outside of Frankish suzerainty.

Having achieved great successes against the Frisians, Pepin turned towards the Alemanni. In 709 he launched a war against Willehari, duke of the Ortenau, probably in an effort to force the succession of the young sons of the deceased Gotfrid on the ducal throne. This outside interference led to another war in 712 and the Alemanni were, for the time being, restored to the Frankish fold.

However, in southern Gaul, which was not under Arnulfing influence, the regions were pulling away from the royal court under leaders such as Savaric of Auxerre Savaric (died 715) was the Bishop of Auxerre from 710 until his death. A member of high nobility, he was a warrior who held a bishopric. He was the father of Eucherius, Bishop of Orleans.

He gathered a large army and subjected the region of the ...

, Antenor of Provence Antenor was the Patrician of Provence in the last years of the 7th and first years of the 8th century. He was independent of Arnulfing authority and the representative of the Merovingian sovereign in Provence at a time when Arnulfing power was ecli ...

, and Odo of Aquitaine. The reigns of Clovis IV and Childebert III

Childebert III (or IV), called the Just (french: le Juste) (c.678/679 – 23 April 711), was the son of Theuderic III and Clotilda (or Doda) and sole king of the Franks (694–711). He was seemingly but a puppet of the mayor of the palace, P ...

from 691 until 711 have all the hallmarks of those of ''rois fainéants'', though Childebert is founding making royal judgements against the interests of his supposed masters, the Arnulfings.

Death of Pepin

When Pepin died in 714, however, the Frankish realm plunged into civil war and the dukes of the outlying provinces became ''de facto'' independent. Pepin's appointed successor, Theudoald, under his widow, Plectrude, initially opposed an attempt by the king, Dagobert III, to appoint Ragenfrid as mayor of the palace in all the realms, but soon there was a third candidate for the mayoralty of Austrasia in Pepin's illegitimate adult son, Charles Martel. After the defeat of Plectrude and Theudoald by the king (now Chilperic II) and Ragenfrid, Charles briefly raised a king of his own, Chlothar IV, in opposition to Chilperic. Finally, at a battle near Soisson, Charles definitively defeated his rivals and forced them into hiding, eventually accepting the king back on the condition that he receive his father's positions (718). There were no more active Merovingian kings after that point and Charles and hisCarolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

heirs ruled the Franks.

After 718 Charles Martel embarked on a series of wars intended to strengthen the Franks' hegemony in western Europe. In 718 he defeated the rebellious Saxons, in 719 he overran Western Frisia, in 723 he suppressed the Saxons again, and in 724 he defeated Ragenfrid and the rebellious Neustrians, ending the civil war phase of his rule. In 720, when Chilperic II died, he had appointed Theuderic IV king, but this last was a mere puppet of his. In 724 he forced his choice of Hugbert for the ducal succession upon the Bavarians and forced the Alemanni to assist him in his campaigns in Bavaria (725 and 726), where laws were promulgated in Theuderic's name. In 730 Alemannia had to be subjugated by the sword and its duke, Lantfrid, was killed. In 734 Charles fought against Eastern Frisia and finally subdued it.

Umayyad invasion

In the 730s the Umayyad conquerors of Spain, who had also subjugatedSeptimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

, began advancing northwards into central Francia and the Loire valley. It was at this time (circa 736) that Maurontus, the ''dux'' of Provence, called in the Umayyads to aid him in resisting the expanding influence of the Carolingians. However, Charles invaded the Rhône Valley with his brother Childebrand

Childebrand I (678 – 743 or 751) was a Frankish duke (''dux''), illegitimate son of Pepin of Heristal and Alpaida, and brother of Charles Martel. He was born in Autun, where he later died. He married Emma of Austrasia and was given Burgundy by h ...

and a Lombard army and devastated the region. It was because of the alliance against the Arabs that Charles was unable to support Pope Gregory III against the Lombards.

In 732 or 737—modern scholars have debated over the date—Charles marched against an Arab army between Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

and Tours and defeated it in a watershed battle that turned back the tide of the Arab advance north of the Pyrenees. But Charles's real interests lay in the northeast, primarily with the Saxons, from whom he had to extort the tribute which for centuries they had paid to the Merovingians.

Shortly before his death in October 741, Charles divided the realm as if he were king between his two sons by his first wife, marginalising his younger son Grifo, who did receive a small portion (it is unknown exactly what). Though there had been no king since Theuderic's death in 737, Charles's sons Pepin the Younger and Carloman were still only mayors of the palaces. The Carolingians had assumed the regal status and practice, though not the regal title, of the Merovingians. The division of the kingdom gave Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

, Alemannia, and Thuringia to Carloman and Neustria, Provence, and Burgundy to Pepin. It is indicative of the ''de facto'' autonomy of the duchies of Aquitaine (under Hunoald) and Bavaria (under Odilo) that they were not included in the division of the ''regnum''.

After Charles Martel was buried, in the Abbey of Saint-Denis alongside the Merovingian kings, conflict immediately erupted between Pepin and Carloman on one side and Grifo their younger brother on the other. Though Carloman captured and imprisoned Grifo, it may have been enmity between the elder brothers that caused Pepin to release Grifo while Carloman was on a pilgrimage to Rome. Perhaps in an effort to neutralise his brother's ambitions, Carloman initiated the appointment of a new king, Childeric III, drawn from a monastery, in 743. Others have suggested that perhaps the position of the two brothers was weak or challenged, or perhaps there Carloman was merely acting for a loyalist or legitimist party in the kingdom.

In 743 Pepin campaigned against Odilo and forced him to submit to Frankish suzerainty. Carloman also campaigned against the Saxons and the two together defeated a rebellion led by Hunoald at the head of the Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Bas ...

and another led by Alemanni, in which Liutfrid of Alsatia probably died, either fighting for or against the brothers. In 746, however, the Frankish armies were still, as Carloman was preparing to retire from politics and enter the monastery of Mount Soratte. Pepin's position was further stabilised and the path was laid for his assumption of the crown in 751.

Carolingian empire, 751–840

Pepin reigned as an elected king. Although such elections happened infrequently, a general rule in Germanic law stated that the king relied on the support of his leading men. These men reserved the right to choose a new "kingworthy" leader out of the ruling clan if they felt that the old one could not lead them in profitable battle. While in later France the kingdom became hereditary, the kings of the later Holy Roman Empire proved unable to abolish the elective tradition and continued as elected rulers until the empire's formal end in 1806.

Pepin solidified his position in 754 by entering into an alliance with

Pepin reigned as an elected king. Although such elections happened infrequently, a general rule in Germanic law stated that the king relied on the support of his leading men. These men reserved the right to choose a new "kingworthy" leader out of the ruling clan if they felt that the old one could not lead them in profitable battle. While in later France the kingdom became hereditary, the kings of the later Holy Roman Empire proved unable to abolish the elective tradition and continued as elected rulers until the empire's formal end in 1806.

Pepin solidified his position in 754 by entering into an alliance with Pope Stephen II

Pope Stephen II ( la, Stephanus II; 714 – 26 April 757) was born a Roman aristocrat and member of the Orsini family. Stephen was the bishop of Rome from 26 March 752 to his death. Stephen II marks the historical delineation between the Byzant ...

, who presented the king of the Franks a copy of the forged " Donation of Constantine" at Paris and in a magnificent ceremony at Saint-Denis anointed the king and his family and declared him ''patricius Romanorum'' ("protector of the Romans"). The following year Pepin fulfilled his promise to the pope and retrieved the Exarchate of Ravenna, recently fallen to the Lombards, and returned it to the Papacy.

Pepin donated the re-conquered areas around Rome to the Pope, laying the foundation for the Papal States in the " Donation of Pepin" which he laid on the tomb of St Peter. The papacy had good cause to expect that the remade Frankish monarchy would provide a deferential power base (''potestas'') in the creation of a new world order, centred on the Pope.

Upon Pepin's death in 768, his sons, Charles and Carloman, once again divided the kingdom between themselves. However, Carloman withdrew to a monastery and died shortly thereafter, leaving sole rule to his brother, who would later become known as Charlemagne or Charles the Great, a powerful, intelligent, and modestly literate figure who became a legend for the later history of both France and Germany. Charlemagne restored an equal balance between emperor and pope.

From 772 onwards, Charles conquered and eventually defeated the Saxons to incorporate their realm into the Frankish kingdom. This campaign expanded the practice of non-Roman Christian rulers undertaking the conversion of their neighbours by armed force; Frankish Catholic missionaries, along with others from Ireland and Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom o ...

, had entered Saxon lands since the mid-8th century, resulting in increasing conflict with the Saxons, who resisted the missionary efforts and parallel military incursions.

Charles's main Saxon opponent, Widukind, accepted baptism in 785 as part of a peace agreement, but other Saxon leaders continued to fight. Upon his victory in 787 at Verden Verden can refer to:

* Verden an der Aller, a town in Lower Saxony, Germany

* Verden, Oklahoma, a small town in the USA

* Verden (district), a district in Lower Saxony, Germany

* Diocese of Verden (768–1648), a former diocese of the Catholic Chur ...

, Charles ordered the wholesale killing

Killing, Killings, or The Killing may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Killing'' (film), a 2018 Japanese film

* ''The Killing'' (film), a 1956 film noir directed by Stanley Kubrick Television

* ''The Killing'' (Danish TV serie ...

of thousands of pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

Saxon prisoners. After several more uprisings, the Saxons suffered definitive defeat in 804. This expanded the Frankish kingdom eastwards as far as the Elbe river, something the Roman empire had only attempted once, and at which it failed in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 AD). In order to more effectively Christianize the Saxons, Charles founded several bishoprics, among them Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

, Münster, Paderborn, and Osnabrück.

At the same time (773–774), Charles conquered the Lombards and thus included northern Italy in his sphere of influence. He renewed the Vatican donation and the promise to the papacy of continued Frankish protection.

In 788, Tassilo, ''dux'' (duke) of Bavaria rebelled against Charles. Crushing the rebellion incorporated Bavaria into Charles's kingdom. This not only added to the royal ''fisc'', but also drastically reduced the power and influence of the Agilolfings (Tassilo's family), another leading family among the Franks and potential rivals. Until 796, Charles continued to expand the kingdom even farther southeast, into today's Austria and parts of Croatia.

Charles thus created a realm that reached from the Pyrenees in the southwest (actually, including an area in Northern Spain (''Marca Hispanica

The Hispanic March or Spanish March ( es, Marca Hispánica, ca, Marca Hispànica, Aragonese and oc, Marca Hispanica, eu, Hispaniako Marka, french: Marche d'Espagne), was a military buffer zone beyond the former province of Septimania, esta ...

'') after 795) over almost all of today's France (except Brittany, which the Franks never conquered) eastwards to most of today's Germany, including northern Italy and today's Austria. In the hierarchy of the church, bishops and abbots looked to the patronage of the king's palace, where the sources of patronage and security lay. Charles had fully emerged as the leader of Western Christendom, and his patronage of monastic centres of learning gave rise to the "Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

" of literate culture. Charles also created a large palace at Aachen, a series of roads, and a canal.

On Christmas Day, 800, Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

crowned Charles as " Emperor of the Romans" in Rome in a ceremony

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secular) ...

presented as a surprise (Charlemagne did not wish to be indebted to the bishop of Rome), a further papal move in the series of symbolic gestures that had been defining the mutual roles of papal ''auctoritas'' and imperial ''potestas.'' Though Charlemagne preferred the title "Emperor, king of the Franks and Lombards", the ceremony formally acknowledged the ruler of the Franks as the Roman Emperor, triggering disputes with the Byzantine Empire, which had maintained the title since the division of the Roman Empire into East and West. The pope's right to proclaim successors was based on the Donation of Constantine, a forged Roman imperial decree. After an initial protest at the usurpation, the Byzantine Emperor Michael I Rhangabes acknowledged in 812 Charlemagne as co-emperor, according to some. According to others, Michael I reopened negotiations with the Franks in 812 and recognized Charlemagne as ''basileus

''Basileus'' ( el, ) is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs in history. In the English-speaking world it is perhaps most widely understood to mean "monarch", referring to either a "king" or an "emperor" and al ...

'' (emperor), but not as emperor of the Romans. The coronation gave permanent legitimacy to Carolingian primacy among the Franks. The Ottonians later resurrected this connection in 962.

Upon Charlemagne's death on 28 January 814 in Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

, he was buried in his own Palace Chapel at Aachen.

Divided empire, after 840

Lothair I

Lothair I or Lothar I (Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario'') (795 – 29 September 855) was emperor (817–855, co-ruling with his father until 840), and the governor of Bavar ...

became Emperor in name but ''de facto'' only the ruler of the Middle Frankish Kingdom

Lotharingia ( la, regnum Lotharii regnum Lothariense Lotharingia; french: Lotharingie; german: Reich des Lothar Lotharingien Mittelreich; nl, Lotharingen) was a short-lived medieval successor kingdom of the Carolingian Empire. As a more durable ...

, or Middle Francia, known as King of the Central or Middle Franks. His three sons in turn divided this kingdom between them into Lotharingia (centered on Lorraine), Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

, and (Northern) Italy Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

. These areas with different cultures, peoples and traditions would later vanish as separate kingdoms, which would eventually become Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Lorraine, Switzerland, Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

and the various departments of France along the Rhône drainage basin and Jura massif

The Jura Mountains ( , , , ; french: Massif du Jura; german: Juragebirge; it, Massiccio del Giura, rm, Montagnas da Jura) are a sub-alpine mountain range a short distance north of the Western Alps and mainly demarcate a long part of the Frenc ...

.

# Louis's second son, Louis the German, became King of the East Frankish Kingdom or East Francia. This area formed the kernel of the later Holy Roman Empire by way of the Kingdom of Germany enlarged with some additional territories from Lothair's Middle Frankish Realm: much of these territories eventually evolved into modern Austria, Switzerland and Germany. For a list of successors, see the List of German monarchs.

# His third son Charles the Bald became King of the West Franks, of the West Frankish Kingdom or West Francia. This area, most of today's southern and western France, became the foundation for the later France under the House of Capet. For his successors, see the List of French monarchs.

Subsequently, at the Treaty of Mersen

The Treaty of Mersen or Meerssen, concluded on 8 August 870, was a treaty to partition the realm of Lothair II, known as Lotharingia, by his uncles Louis the German of East Francia and Charles the Bald of West Francia, the two surviving sons of E ...

(870) the partitions were recast, to the detriment of Lotharingia. On 12 December 884, Charles the Fat (son of Louis the German) reunited most of the Carolingian Empire, aside from Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

. In late 887, his nephew Arnulf of Carinthia

Arnulf of Carinthia ( 850 – 8 December 899) was the duke of Carinthia who overthrew his uncle Emperor Charles the Fat to become the Carolingian king of East Francia from 887, the disputed king of Italy from 894 and the disputed emperor from Feb ...

revolted and assumed the title as King of the East Franks. Charles retired and soon died on 13 January 888.

Odo, Count of Paris was chosen to rule in the west, and was crowned the next month. At this point, West Francia was composed of Neustria in the west and in the east by Francia proper, the region between the Meuse and the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributarie ...

. The Carolingians were restored ten years later in West Francia, and ruled until 987, when the last Frankish King, Louis V, died.

West Francia was the land under the control of Charles the Bald. It is the precursor of modern France. It was divided into the following great fiefs: Aquitaine, Brittany, Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

, Catalonia, Flanders, Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

, Gothia, the Île-de-France, and Toulouse. After 987, the kingdom came to be known as France, because the new ruling dynasty (the Capetians

The Capetian dynasty (; french: Capétiens), also known as the House of France, is a dynasty of Frankish origin, and a branch of the Robertians. It is among the largest and oldest royal houses in Europe and the world, and consists of Hugh Cape ...

) were originally dukes of the Île-de-France.

Middle Francia was the territory ruled by Lothair I

Lothair I or Lothar I (Dutch and Medieval Latin: ''Lotharius''; German: ''Lothar''; French: ''Lothaire''; Italian: ''Lotario'') (795 – 29 September 855) was emperor (817–855, co-ruling with his father until 840), and the governor of Bavar ...

, wedged between East and West Francia. The kingdom, which included the Kingdom of Italy, Burgundy, the Provence, and the west of Austrasia

Austrasia was a territory which formed the north-eastern section of the Merovingian Kingdom of the Franks during the 6th to 8th centuries. It was centred on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers, and was the original territory of the F ...

, was an unnatural creation of the Treaty of Verdun, with no historical or ethnic identity. The kingdom was split on the death of Lothair II

Lothair II (835 – 8 August 869) was the king of Lotharingia from 855 until his death. He was the second son of Emperor Lothair I and Ermengarde of Tours. He was married to Teutberga (died 875), daughter of Boso the Elder.

Reign

For political ...

in 869 into those of Lotharingia, Provence (with Burgundy divided between it and Lotharingia), and north Italy.

East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided t ...

was the land of Louis the German. It was divided into four duchies: Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

(Alamannia

Alamannia, or Alemannia, was the kingdom established and inhabited by the Alemanni, a Germanic peoples, Germanic tribal confederation that had broken through the Roman ''Upper Germanic Limes, limes'' in 213.

The Alemanni expanded from the Main ...

), Franconia, Saxony and Bavaria; to which after the death of Lothair II were added the eastern parts of Lotharingia. This division persisted until 1268, the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Otto I was crowned on 2 February 962, marking the beginning of the Holy Roman Empire ('' translatio imperii''). From the 10th century, East Francia became also known as ''regnum Teutonicum'' (" Teutonic kingdom" or " Kingdom of Germany"), a term that became prevalent in Salian times. The title of Holy Roman Emperor was used from that time, beginning with Conrad II

Conrad II ( – 4 June 1039), also known as and , was the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 1027 until his death in 1039. The first of a succession of four Salian emperors, who reigned for one century until 1125, Conrad ruled the kingdoms ...

.

Life in Francia

Law

The different Frankish tribes, such as the Salii, Ripuarii, and Chamavi, had different legal traditions, which were only later codified, largely under Charlemagne. The '' Leges Salica'', '' Ribuaria'', and '' Chamavorum'' were Carolingian creations, their basis in earlier Frankish reality being difficult for scholars to discern at the present distance. Under Charlemagne codifications were also made of the Saxon law and the Frisian law. It was also under Frankish hegemony that the other Germanic societies east of the Rhine began to codify their tribal law, in such compilations as the '' Lex Alamannorum'' and '' Lex Bajuvariorum'' for the Alemanni and Bavarii respectively. Throughout the Frankish kingdoms there continued to beGallo-Romans

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization (cultural), Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, Roman culture, language, morals and wa ...

subject to Roman law and clergy subject to canon law. After the Frankish conquest of Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

and Catalonia, those regions which had formerly been under Gothic control continued to utilise the Visigothic law code.

During the early period Frankish law was preserved by the ''rachimburgs'', officials trained to remember it and pass it on. The Merovingians adopted the '' capitulary'' as a tool for the promulgation and preservation of royal ordinances. Its usage was to continue under the Carolingians and even the later Spoletan emperors Guy and Lambert

Lambert may refer to

People

*Lambert (name), a given name and surname

* Lambert, Bishop of Ostia (c. 1036–1130), became Pope Honorius II

*Lambert, Margrave of Tuscany ( fl. 929–931), also count and duke of Lucca

*Lambert (pianist), stage-name ...

under a programme of ''renovation regni Francorum'' ("renewal of the Frankish kingdom").

The last Merovingian capitulary was one of the most significant: the edict of Paris, issued by Chlothar II in 614 in the presence of his magnates, had been likened to a Frankish Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

entrenching the rights of the nobility, but in actuality it sought to remove corruption from the judiciary and protect local and regional interests. Even after the last Merovingian capitulary, kings of the dynasty continued to independently exercise some legal powers. Childebert III even found cases against the powerful Arnulfings and became renowned among the people for his justness. But law in Francia was to experience a renaissance under the Carolingians.

Among the legal reforms adopted by Charlemagne were the codifications of traditional law mentioned above. He also sought to place checks on the power of local and regional judiciaries by the method of appointing '' missi dominici'' in pairs to oversee specific regions for short periods of time. Usually ''missi'' were selected from outside their respective regions in order to prevent conflicts of interest. A capitulary of 802 gives insight into their duties. They were to execute justice, enforce respect for the royal rights, control the administration of the counts and dukes (then still royal appointees), receive the oath of allegiance, and supervise the clergy.

Church

The Frankish Church grew out of the Church in Gaul in the Merovingian period, which was given a particularly Germanic development in a number of "Frankish synods" throughout the 6th and 7th centuries, and with theCarolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

, the Frankish Church became a substantial influence of the medieval Western Church.

In the 7th century, the territory of the Frankish realm was (re-)Christianized with the help of Irish and Scottish missionaries. The result was the establishment of numerous monasteries, which would become the nucleus of Old High German literacy in the Carolingian Empire.

Columbanus

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in pr ...

was active in the Frankish Empire from 590, establishing monasteries until his death at Bobbio in 615. He arrived on the continent with twelve companions and founded Annegray, Luxeuil, and Fontaines in France and Bobbio in Italy. During the 7th century the disciples of Columbanus and other Scottish and Irish missionaries founded several monasteries or ''Schottenklöster'' in what are now France, Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland.

The Irish influence in these monasteries is reflected in the adoption of Insular

Insular is an adjective used to describe:

* An island

* Someone who is isolated and parochial

Insular may also refer to:

Sub-national territories or regions

* Insular Chile

* Insular region of Colombia

* Insular Ecuador, administratively known ...

style in book production, visible in 8th-century works such as the Gelasian Sacramentary. The Insular

Insular is an adjective used to describe:

* An island

* Someone who is isolated and parochial

Insular may also refer to:

Sub-national territories or regions

* Insular Chile

* Insular region of Colombia

* Insular Ecuador, administratively known ...

influence on the uncial script of the later Merovingian period eventually gave way to the development of the Carolingian minuscule in the 9th century.

Society

Immediately after the fall of Rome and through the Merovingian dynasty, trading towns were re-established in the ruins of ancient cities. These specialised in exchange of goods, craft and agriculture, and were mostly independent of aristocratic control. Carolingian Francia saw royal sponsorship for the construction of monastic cities, built to showcase a revival of the architecture of ancient Rome. Administration was conducted by bishops. The old Gallo-Roman aristocrats had survived in prestige and as an institution by taking up the episcopal offices, and they were now put in charge of fields such as justice, infrastructure, education and social services. Kings were legitimized by their links with the religious institutions. Episcopal elections became supervised by the kings, and royal confirmation helped to strengthen the bishops' authority as well. There were improvements in agriculture, notably the adoption of a new heavyplough

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

and the growing use of the three-field system.

Currency

Byzantine coinage was in use in Francia before Theudebert I began minting his own money at the start of his reign. The solidus and triens were minted in Francia between 534 and 679. The denarius (or denier) appeared later, in the name of Childeric II and various non-royals around 673–675. A Carolingian denarius replaced the Merovingian one, and the Frisianpenning

Penning may refer to:

__NOTOC__ Currency

*Norwegian penning

*Swedish penning

People

*Mike Penning (born 1957), British politician

*Frans Michel Penning (1894–1953), Dutch physicist

*Edmund Penning-Rowsell (1913–2002), British journalist

* Lo ...

, in Gaul from 755 to the eleventh century.

The denarius subsequently appeared in Italy issued in the name of Carolingian monarchs after 794, later by so-called "native" kings in the tenth century, and later still by the German Emperors from Otto I (962). Finally, denarii were issued in Rome in the names of pope and emperor from Leo III Leo III, Leon III, or Levon III may refer to:

; People

* Leo III the Isaurian (685-741), Byzantine emperor 717-741

* Pope Leo III (d. 816), Pope 795-816

* Leon III of Abkhazia, King of Abkhazia 960–969

* Leo II, King of Armenia (c. 1236–1289), ...

and Charlemagne onwards to the late tenth century.

See also

* List of modern countries within the Frankish Empire * List of Frankish kingsReferences

Citations

Sources

; Primary sources * Ammianus Marcellinus.Roman History

'. trans. by Roger Pearse. London: Bohn, 1862. * Procopius. ''

History of the Wars

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gener ...

''. trans. by H. B. Dewing.

* Fredegar. The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its Continuations

'. trans. by John Michael Wallace-Hadrill. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1960. * Fredegar.

Historia Epitomata

'. Woodruff, Jane Ellen. PhD Dissertation, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 1987. *

Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florenti ...

''Historia Francorum''.

*

Gregory of Tours