Frank Douglas MacKinnon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

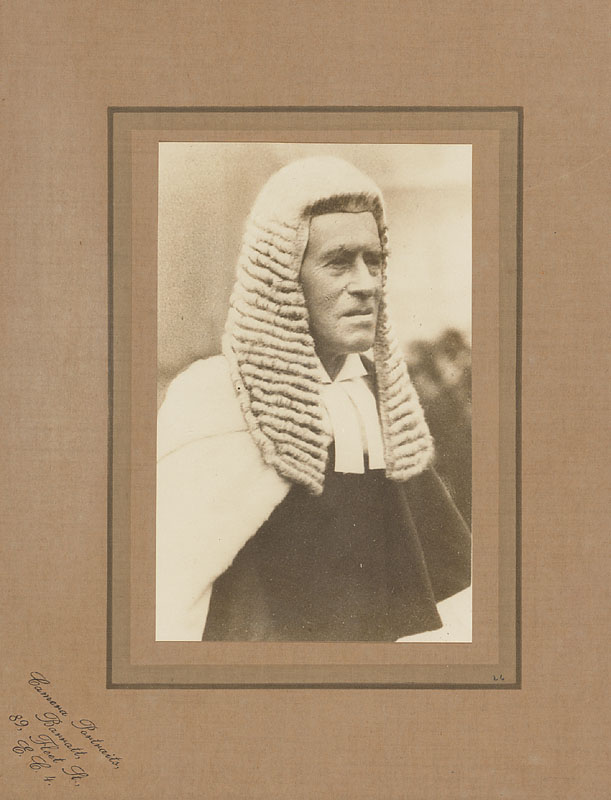

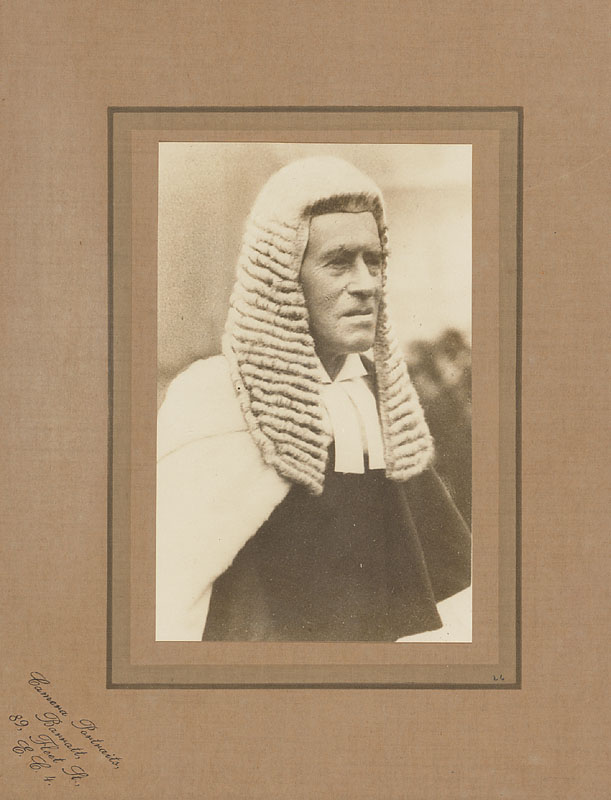

Sir Frank Douglas MacKinnon (11 February 1871 – 23 January 1946) was an English lawyer, judge and writer, the only High Court judge to be appointed during the First Labour Government.

Sir Frank Douglas MacKinnon (11 February 1871 – 23 January 1946) was an English lawyer, judge and writer, the only High Court judge to be appointed during the First Labour Government.

Sir Frank Douglas MacKinnon (11 February 1871 – 23 January 1946) was an English lawyer, judge and writer, the only High Court judge to be appointed during the First Labour Government.

Sir Frank Douglas MacKinnon (11 February 1871 – 23 January 1946) was an English lawyer, judge and writer, the only High Court judge to be appointed during the First Labour Government.

Early life and legal practice

Born inHighgate

Highgate ( ) is a suburban area of north London at the northeastern corner of Hampstead Heath, north-northwest of Charing Cross.

Highgate is one of the most expensive London suburbs in which to live. It has two active conservation organisat ...

, London, the eldest son of 7 children of Benjamin Thomas, a Lloyd's

Lloyd's of London, generally known simply as Lloyd's, is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company; rather, Lloyd's is a corporate body gov ...

underwriter

Underwriting (UW) services are provided by some large financial institutions, such as banks, insurance companies and investment houses, whereby they guarantee payment in case of damage or financial loss and accept the financial risk for liabilit ...

and Katherine ''née'' Edwards, he attended Highgate School and Trinity College, Oxford

(That which you wish to be secret, tell to nobody)

, named_for = The Holy Trinity

, established =

, sister_college = Churchill College, Cambridge

, president = Dame Hilary Boulding

, location = Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3BH

, coordinates ...

, graduating in classics (1892) and '' literae humaniores'' (1894). MacKinnon was called to the bar by the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and ...

in 1897 and became a pupil

The pupil is a black hole located in the center of the Iris (anatomy), iris of the Human eye, eye that allows light to strike the retina.Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) ''Dictionary of Eye Terminology''. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing ...

of Thomas Edward Scrutton

Sir Thomas Edward Scrutton (28 August 1856 – 18 August 1934) was an English barrister, judge, and legal writer.

Biography

Thomas Edward Scrutton was born in London, the son of Thomas Urquhart Scrutton, a wealthy shipowner and head of the well-k ...

Rubin (2004) where he was a contemporary of James Richard Atkin, later to become Lord Atkin

James Richard Atkin, Baron Atkin, (28 November 1867 – 25 June 1944), commonly known as Dick Atkin, was an Australian-born British judge, who served as a lord of appeal in ordinary from 1928 until his death in 1944. He is especially remember ...

. When Scrutton became a QC in 1901, MacKinnon benefited from Scrutton's former junior practice in commercial law. MacKinnon's brother, Sir Percy Graham MacKinnon (1872–1956) was, from time to time, chairman of Lloyd's and his family connections helped build his practice.

MacKinnon married Frances Massey in 1906 and the couple had two children. He became a KC in 1914 and found the circumstances of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

led him to an extensive practice in prize law

In admiralty law prizes are equipment, vehicles, vessels, and cargo captured during armed conflict. The most common use of ''prize'' in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship and her cargo as a prize of war. In the past, the capturing force ...

. The war also generated many complex contractual disputes and MacKinnon developed a reputation for handling such cases with skill. Many issues such as frustration of contract

Frustration of purpose, in law, is a defense to enforcement of a contract. Frustration of purpose occurs when an unforeseen event undermines a party's principal purpose for entering into a contract such that the performance of the contract is rad ...

attracted his attention and his pen.

He began to establish a reputation as a jurist and to advise the government on mercantile law, especially its international dimension.

High Court judge

In October 1924, the minority Labour government was suffering the repercussions of theCampbell case

The Campbell Case of 1924 involved charges against a British communist newspaper editor, J. R. Campbell, for alleged "incitement to mutiny" caused by his publication of a provocative open letter to members of the military. The decision of the go ...

and was not expected to survive. When Sir Clement Bailhache

Sir Clement Meacher Bailhache (2 November 1856 – 8 September 1924) was an English commercial lawyer and judge.

Early life

Bailhache was born at Leeds, the eldest son of Rev. Clement Bailhache, of Huguenot descent, a Baptist minister and secret ...

died, Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, (; 30 July 1856 – 19 August 1928) was a British lawyer and philosopher and an influential Liberal and later Labour politician. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during ...

was anxious that the appointment of a High Court judge was not made "in the last agony of the government's existence". The appointment was made in some haste.

MacKinnon sat in the Commercial Court but also went on circuit with the assizes. Criminal law and juries

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartial verdict (a finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

Juries developed in England dur ...

had never formed a material part of his practice but he adapted well though his reputation as a judge never matched his standing as a lawyer.

In 1926, he chaired a committee to review the law on arbitration. The committee concluded that the Arbitration Act 1889 had been effective and recommended only some miscellaneous amendments. The recommendations were only partly implemented in the Arbitration Acts of 1928 and 1934

Events

January–February

* January 1 – The International Telecommunication Union, a specialist agency of the League of Nations, is established.

* January 15 – The 8.0 Nepal–Bihar earthquake strikes Nepal and Bihar with a maxi ...

.

Lord Justice of Appeal

In 1937, MacKinnon was elevated to the Court of Appeal and sworn into the Privy Council. A pragmatist, he may have had a greater impact had he not felt so impatient as to never reserve judgment. He was considered for theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

in 1938 but Samuel Porter, Baron Porter

Samuel Lowry Porter, Baron Porter, (7 February 1877 – 13 February 1956) was a British judge.

Early life and career

Born in Leeds, Porter was educated at the Perse School and Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he took a Third in Classics ...

was preferred.

He was one of those judges who, on occasion, causes amusement through their unfamiliarity with popular culture. In a notorious libel trial in 1943, the court was viewing a photograph from the magazine '' Lilliput'' showing a well-known male fashion designer juxtaposed next to a pansy

The garden pansy (''Viola'' × ''wittrockiana'') is a type of large-flowered hybrid plant cultivated as a garden flower. It is derived by hybridization from several species in the section ''Melanium'' ("the pansies") of the genus ''Viola'', ...

. MacKinnon had to ask Rayner Goddard, Baron Goddard

William Edgar Rayner Goddard, Baron Goddard, (10 April 1877 – 29 May 1971) was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1946 to 1958, known for his strict sentencing and mostly conservative views despite being the first Lord Chief Justice to be ap ...

to explain the innuendo

An innuendo is a hint, insinuation or intimation about a person or thing, especially of a denigrating or derogatory nature. It can also be a remark or question, typically disparaging (also called insinuation), that works obliquely by allusion ...

. Towards the end of his life he confessed to neither owning nor intending to own a " wiresless set".

He also gained some notoriety for doubting the grounds of the leading negligence

Negligence (Lat. ''negligentia'') is a failure to exercise appropriate and/or ethical ruled care expected to be exercised amongst specified circumstances. The area of tort law known as ''negligence'' involves harm caused by failing to act as a ...

case of '' Donoghue v. Stevenson''. About the case, which involved a snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class G ...

in a bottle of ginger beer

Traditional ginger beer is a sweetened and carbonated, usually non-alcoholic beverage. Historically it was produced by the natural fermentation of prepared ginger spice, yeast and sugar.

Current ginger beers are often manufactured rather than ...

, MacKinninon said, in his 1942 Holdsworth lecture:Lewis ''Op. cit.'' 52

Lord Normand

Wilfrid Guild Normand, Baron Normand, (1884 – 5 October 1962), was a Scottish Unionist Party politician and judge. He was a Scottish law officer at various stages between 1929 and 1935, and a member of parliament (MP) from 1931 to 1935. He ...

, the defendant's advocate, always insisted that MacKinnon's allegation was untrue.Lewis ''Op. cit.'' 52–53

Trials as judge

*''Shirlaw v. Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd'' 9392 KB 206 – in which he defined the " officious bystander test" for impliedcontractual term

A contractual term is "any provision forming part of a contract". Each term gives rise to a contractual obligation, the breach of which may give rise to litigation. Not all terms are stated expressly and some terms carry less legal gravity as th ...

s.

*''Salisbury (Marquess) v. Gilmore'' 942– in which Tom Denning KC attempted to argue that the doctrine of estoppel should be extended to promises rather than solely statements of fact. MacKinnon rejected the argument but Denning had his way once he himself was a High Court judge in ''Central London Property Trust Ltd v. High Trees House Ltd

''Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd'' 947KB 130 is a famous English contract law decision in the High Court. It reaffirmed and extended the doctrine of promissory estoppel in contract law in England and Wales. However, th ...

'' (1947).

*''R v. Home Secretary, ex parte Greene'' 9421 KB 87 – sitting with Lords Justice of Appeal Scott and Goddard Goddard may refer to:

People

* Goddard (given name)

* Goddard (surname)

Places in the United States

* Goddard, Kansas

*Goddard, Kentucky

*Goddard, Maryland

*Goddard College, a low-residency college with campuses in Vermont and Washington

*Godda ...

, the court rejected Ben Greene

Ben Greene (28 December 1901 – October 1978) was a British Labour Party politician and pacifist. He was interned during the Second World War because of his fascist associations and appealed to the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords aga ...

's application for a writ

In common law, a writ (Anglo-Saxon ''gewrit'', Latin ''breve'') is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, a ...

of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' to review his detention under Defence Regulation 18B

Defence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was one of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during and before the Second World War. The complete name for the rule was Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regula ...

. The court ruled that it could not question the discretion of the Home Secretary, honestly exercised. Greene appealed to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

who, in '' Liversidge v. Anderson'', confirmed the Court of Appeal's decision

Other interests

MacKinnon was an enthusiast for the writing and culture of the eighteenth century and, in particular, the work ofDoctor Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford D ...

. He wrote extensively on the period.MacKinnon (1937) He also considered Victorian architecture

Victorian architecture is a series of architectural revival styles in the mid-to-late 19th century. ''Victorian'' refers to the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901), called the Victorian era, during which period the styles known as Victorian we ...

to have ruined much of what came before. When the Temple Church

The Temple Church is a Royal peculiar church in the City of London located between Fleet Street and the River Thames, built by the Knights Templar as their English headquarters. It was consecrated on 10 February 1185 by Patriarch Heraclius of J ...

was bombed during The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

, he welcomed it with mixed feelings:

Never interested in party politics, MacKinnon was president of the Average Adjusters' Association (1935), of the Johnson Society of Lichfield (1933), and of the Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society, chairman of Buckinghamshire quarter sessions

The courts of quarter sessions or quarter sessions were local courts traditionally held at four set times each year in the Kingdom of England from 1388 (extending also to Wales following the Laws in Wales Act 1535). They were also established in ...

, and member of the Historical Manuscripts Commission

The Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts (widely known as the Historical Manuscripts Commission, and abbreviated as the HMC to distinguish it from the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England), was a United Kingdom Royal Com ...

.

MacKinnon was a keen walker, climbing Snowdon on two consecutive days in February 1931 when aged almost 60.

Personal

"In appearance MacKinnon possessed bushy eyebrows, penetrating eyes, a pronounced angular nose, and firm mouth." His daughter, son-in-law and young grandchild were lost aboard the '' Almeda Star'',torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

ed in 1941. His son became bursar

A bursar (derived from " bursa", Latin for '' purse'') is a professional administrator in a school or university often with a predominantly financial role. In the United States, bursars usually hold office only at the level of higher education ( ...

of Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, ...

. Following a sudden heart attack, he died in Charing Cross Hospital

Charing Cross Hospital is an acute general teaching hospital located in Hammersmith, London, United Kingdom. The present hospital was opened in 1973, although it was originally established in 1818, approximately five miles east, in central L ...

.

Honours

*Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and ...

:

**Bencher

A bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales or the Inns of Court in Northern Ireland, or the Honorable Society of King's Inns in Ireland. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher ca ...

(1923);

**Treasurer (1945);

*Knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed (1924);

*Honorary fellow of Trinity College, Oxford (1931)

*Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

References

Bibliography

By MacKinnon

*MacKinnon, F. D. (1917) ''Effect of War on Contract'' *— (1926) "Some aspects of commercial law" *— (ed.) (1930) Burney, F. ''Evelina'' *— (1933) "The law and the lawyers" in Turberville, A. S. (ed.) ''Johnson's England: An Account of the Life and Manners of his Age'', Oxford: Clarendon Press *— (1935) ''The Murder in the Temple and Other Holiday Tasks'', London: Sweet & Maxwell *— (1936) "The origins of commercial law", ''Law Quarterly Review'', 52 30 *— (1937) ''Grand Larceny'' *— (1940) ''On Circuit: 1924–1937'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press *— (1945a) ''The Ravages of the War in the Inner Temple'' *— (1945b) "An unfortunate preference", ''Law Quarterly Review'', 61 237–8 *— (1948) ''Inner Temple Papers'', London: Stevens & Co. *— (ed.) arious editions''Scrutton on Charterparties and Bills of Lading''Obituaries

* ALG (1946) "F. D. M., 1871–1946", ''Law Quarterly Review'', 62 139–40 *''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'', 24 January 1946

About MacKinnon

* Birkett, N. (1949) "Review of ''Inner Temple papers''", ''Law Quarterly Review'', 65 380–84 *Rubin, G. R. (2004) "MacKinnon, Sir Frank Douglas (1871–1946)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 August 2007

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mackinnon, Frank Douglas 1871 births 1946 deaths English barristers 20th-century English judges English antiquarians Queen's Bench Division judges People educated at Highgate School People from Highgate Knights Bachelor Lords Justices of Appeal Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom