fluorospar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of

Mindat.org Currently, the word "fluorspar" is most commonly used for fluorite as the industrial and chemical commodity, while "fluorite" is used mineralogically and in most other senses. In the context of archeology, gemmology, classical studies, and Egyptology, the Latin terms ''murrina'' and ''myrrhina'' refer to fluorite. In book 37 of his ''

Fluorite crystallizes in a cubic motif.

Fluorite crystallizes in a cubic motif.

Fluorite forms as a late-crystallizing mineral in

Fluorite forms as a late-crystallizing mineral in  In

In

File:Fluorite-Galena-flu70a.jpg, Pastel green fluorite crystal on galena

File:Fluorite-132158.jpg, A golden yellow with hints of purple fluorite

File:Fluorite-cflo06x.jpg, Freestanding purple fluorite cluster between two quartzes

File:Fluorite-189396.jpg, Light to dark burgundy color fluorite

File:Fluorite-158842.jpg, Transparent teal color fluorite with purple highlights

File:Fluorite-233168.jpg, Grass-green fluorite octahedrons clustered on a quartz-rich matrix

Fluorspar

USGS 2009 Minerals Yearbook

Fluorine finally found in nature , Chemistry World

Rsc.org.

File:Fluorite crystals (Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals).jpg, Fluorite crystals on display at the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals, Houston Museum of Natural Science

File:Fluorite and sphalerite J1.jpg, Fluorite and sphalerite, from Elmwood mine, Smith county, Tennessee, US

File:Fluorite-Quartz-226312.jpg, Translucent ball of botryoidal fluorite perched on a calcite crystal

File:FluoriteBerbes.jpg, Fluorite with baryte, from Berbes Mine, Berbes Mining area, Ribadesella, Asturias, Spain

File:Fluorite - Diana Maria mine, Rogerley quarry, Stanhope, County Durham, England.jpg, Fluorite from Diana Maria mine, Weardale, England, UK

File:FluoriteMaroc.jpg, Fluorite from El Hammam Mine, Meknès Prefecture, Meknès-Tafilalet Region, Morocco

File:Fluorite frog, length 8 cm arp.jpg, Toad carved in fluorite. Length 8 cm (3 in).

Educational article about the different colors of fluorites crystals from Asturias, SpainBarber Cup

an

Crawford Cup

related Roman cups at

calcium fluoride

Calcium fluoride is the inorganic compound of the elements calcium and fluorine with the formula CaF2. It is a white insoluble solid. It occurs as the mineral fluorite (also called fluorspar), which is often deeply coloured owing to impurities.

...

, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric

The term ''isometric'' comes from the Greek for "having equal measurement".

isometric may mean:

* Cubic crystal system, also called isometric crystal system

* Isometre, a rhythmic technique in music.

* "Isometric (Intro)", a song by Madeon from ...

cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness () is a Qualitative property, qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch hardness, scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material.

...

, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 4 as fluorite.

Pure fluorite is colourless and transparent, both in visible and ultraviolet light, but impurities usually make it a colorful mineral and the stone has ornamental and lapidary

Lapidary (from the Latin ) is the practice of shaping stone, minerals, or gemstones into decorative items such as cabochons, engraved gems (including cameos), and faceted designs. A person who practices lapidary is known as a lapidarist. A ...

uses. Industrially, fluorite is used as a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ...

for smelting, and in the production of certain glasses and enamels. The purest grades of fluorite are a source of fluoride for hydrofluoric acid

Hydrofluoric acid is a solution of hydrogen fluoride (HF) in water. Solutions of HF are colourless, acidic and highly corrosive. It is used to make most fluorine-containing compounds; examples include the commonly used pharmaceutical antidepr ...

manufacture, which is the intermediate source of most fluorine-containing fine chemical

In chemistry, fine chemicals are complex, single, pure chemical substances, produced in limited quantities in multipurpose plants by multistep batch chemical or biotechnological processes. They are described by exacting specifications, used ...

s. Optically clear transparent fluorite lenses have low dispersion, so lenses made from it exhibit less chromatic aberration

In optics, chromatic aberration (CA), also called chromatic distortion and spherochromatism, is a failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same point. It is caused by dispersion: the refractive index of the lens elements varies with the ...

, making them valuable in microscopes and telescopes. Fluorite optics are also usable in the far-ultraviolet and mid-infrared ranges, where conventional glasses are too opaque for use.

History and etymology

The word ''fluorite'' is derived from theLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

verb ''fluere'', meaning ''to flow''. The mineral is used as a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ...

in iron smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ...

to decrease the viscosity

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

of slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting ( pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/ base metals (by ...

. The term ''flux'' comes from the Latin adjective ''fluxus'', meaning ''flowing, loose, slack''. The mineral fluorite was originally termed fluorospar and was first discussed in print in a 1530 work ''Bermannvs sive de re metallica dialogus'' ermannus; or a dialogue about the nature of metals by Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman ...

, as a mineral noted for its usefulness as a flux. Agricola, a German scientist with expertise in philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

, mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic ...

, and metallurgy, named fluorspar as a neo-Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy a ...

ization of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

''Flussspat'' from ''Fluss'' ( stream, river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the ...

) and ''Spat'' (meaning a nonmetal

In chemistry, a nonmetal is a chemical element that generally lacks a predominance of metallic properties; they range from colorless gases (like hydrogen) to shiny solids (like carbon, as graphite). The electrons in nonmetals behave differen ...

lic mineral akin to gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and dr ...

, spærstān, '' spear stone'', referring to its crystalline projections).

In 1852, fluorite gave its name to the phenomenon of fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, ...

, which is prominent in fluorites from certain locations, due to certain impurities in the crystal. Fluorite also gave the name to its constitutive element fluorine.FluoriteMindat.org Currently, the word "fluorspar" is most commonly used for fluorite as the industrial and chemical commodity, while "fluorite" is used mineralogically and in most other senses. In the context of archeology, gemmology, classical studies, and Egyptology, the Latin terms ''murrina'' and ''myrrhina'' refer to fluorite. In book 37 of his ''

Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

'', Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

describes it as a precious stone with purple and white mottling, whose objects carved from it, the Romans prize.

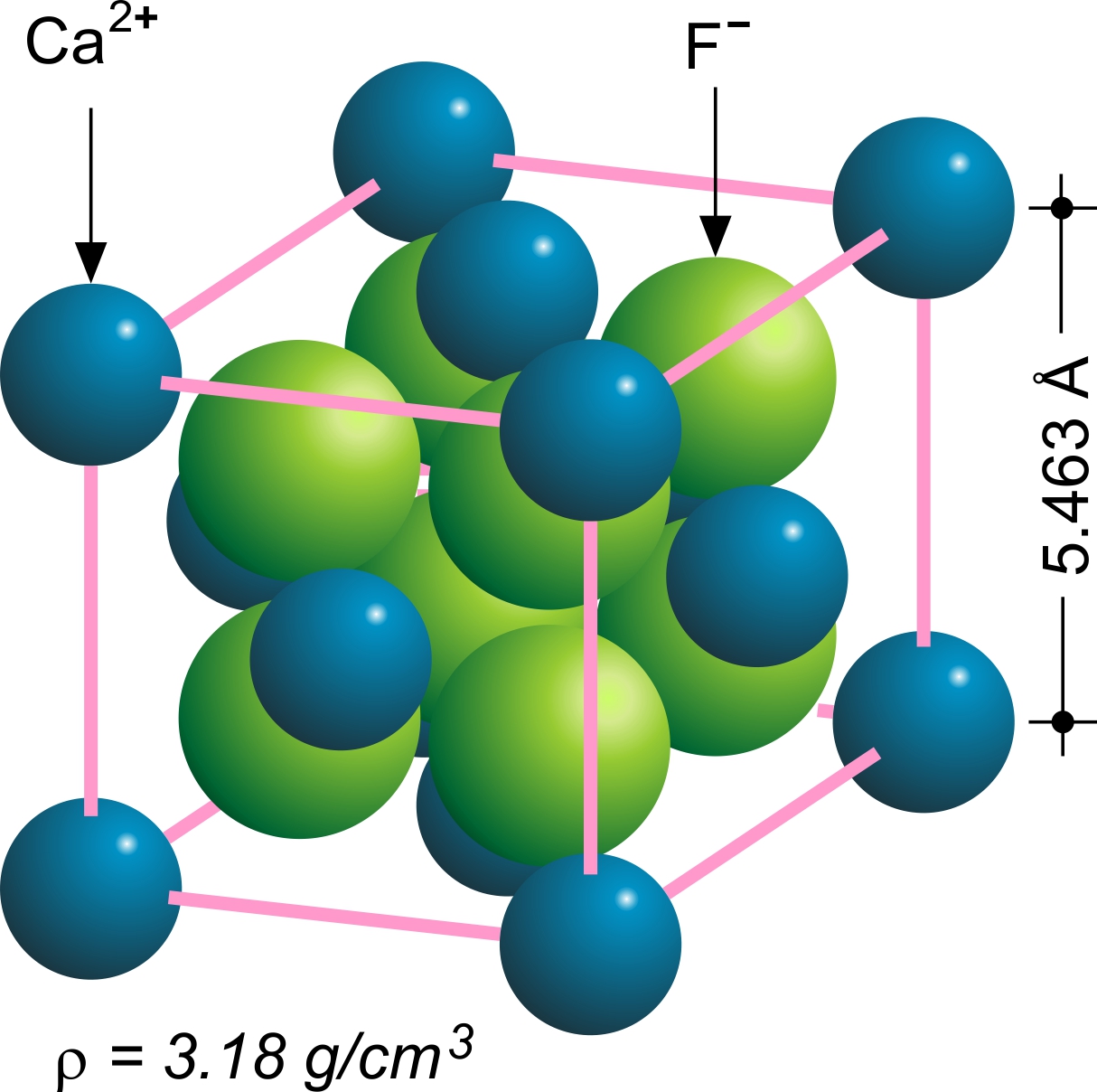

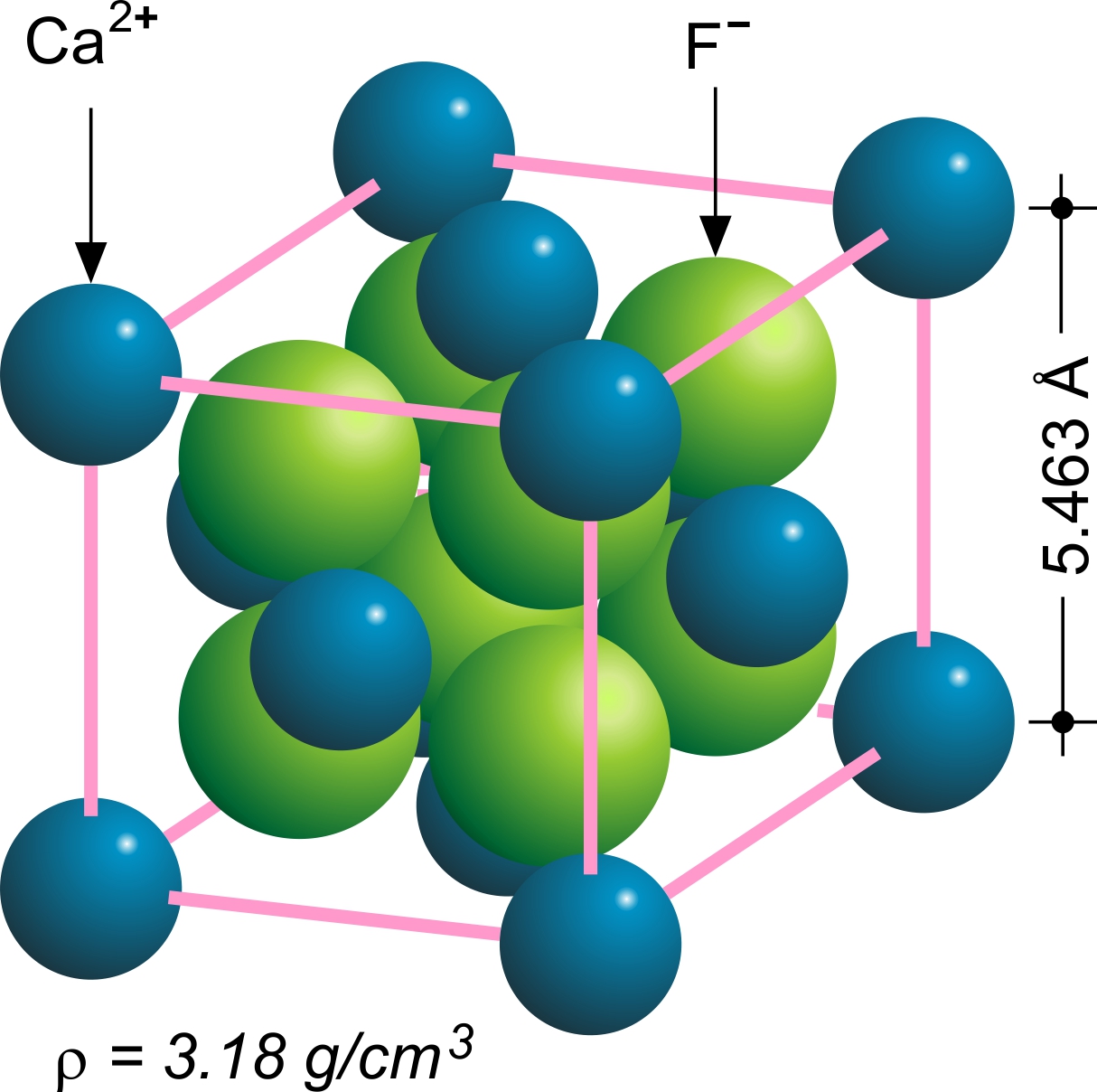

Structure

Fluorite crystallizes in a cubic motif.

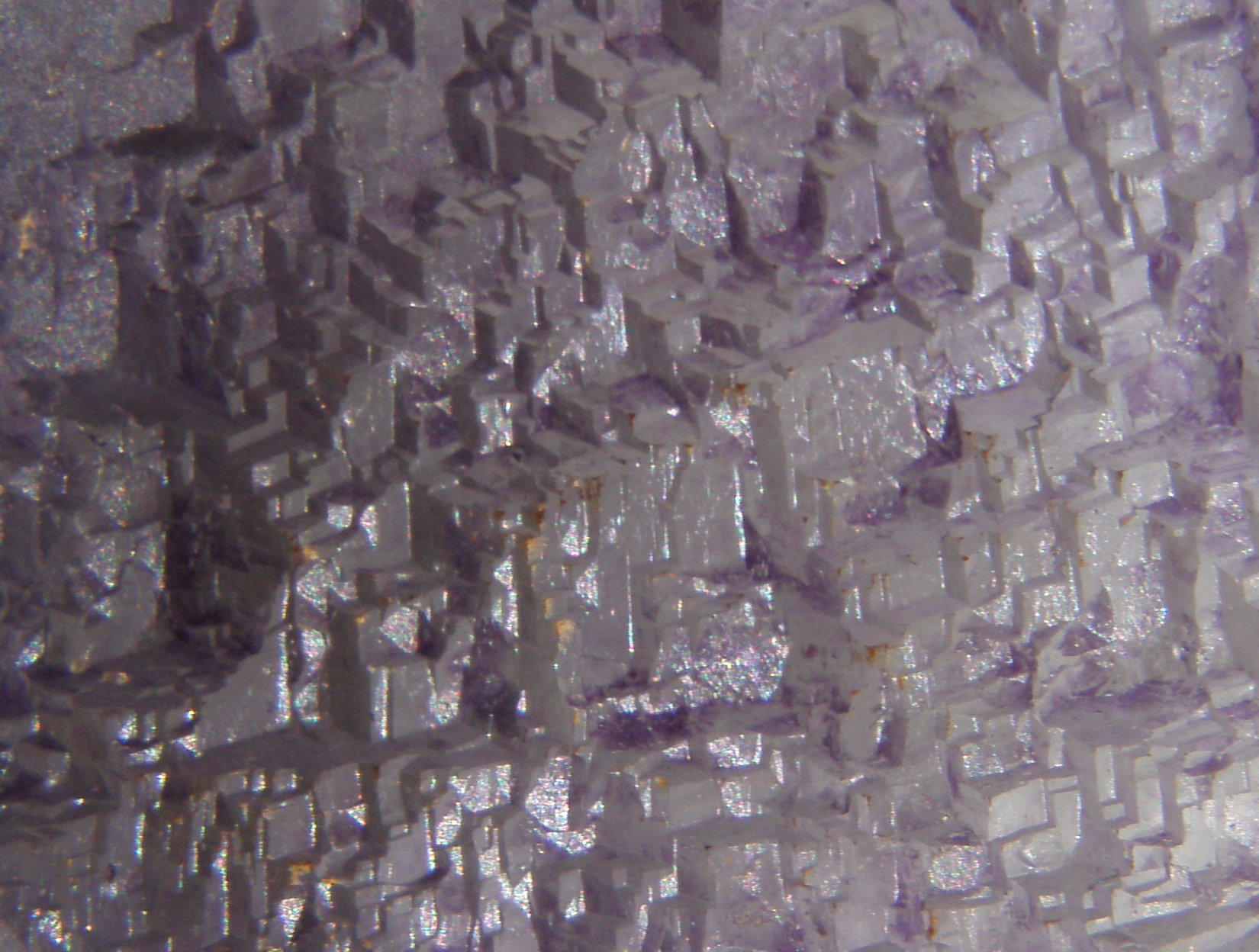

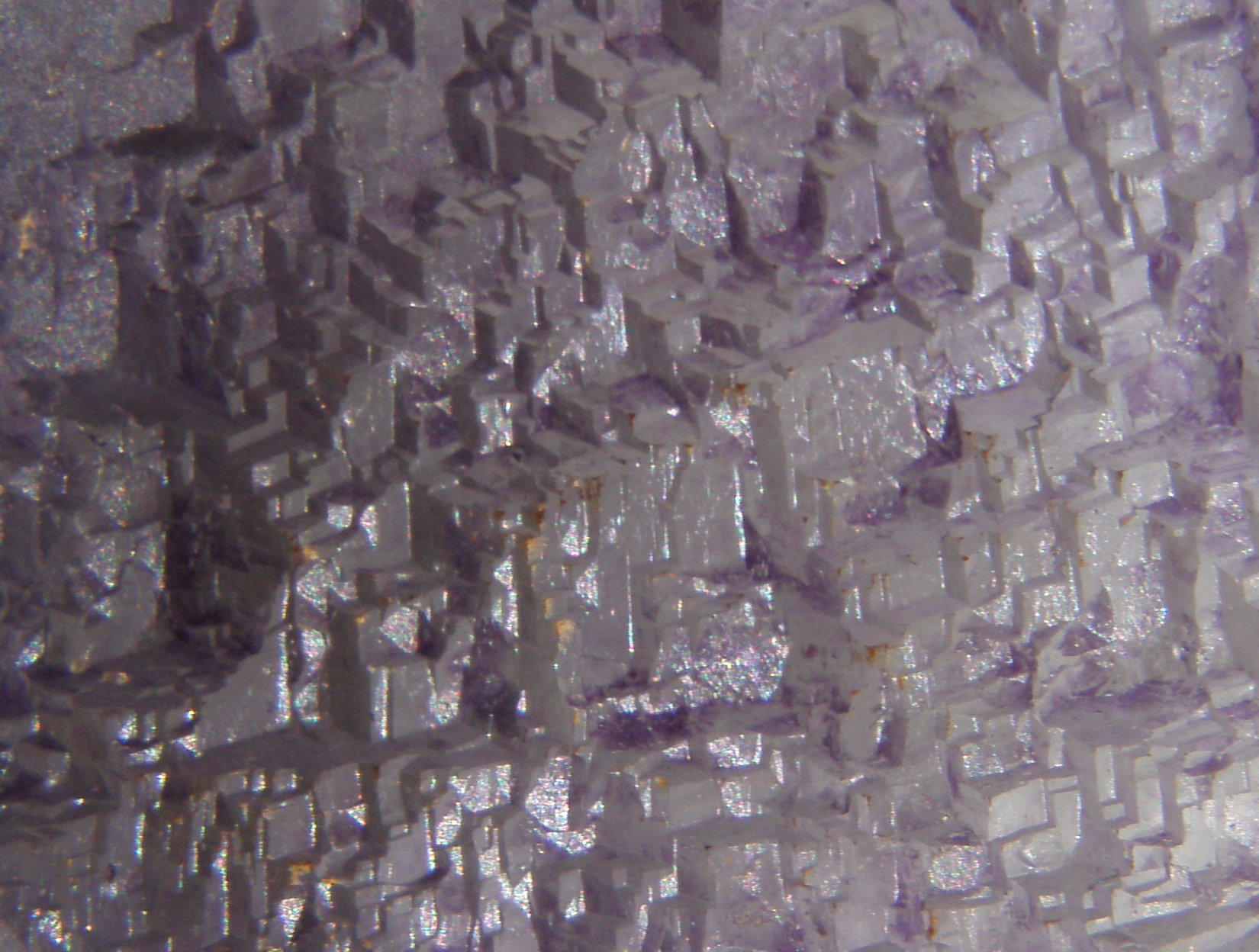

Fluorite crystallizes in a cubic motif. Crystal twinning

Crystal twinning occurs when two or more adjacent crystals of the same mineral are oriented so that they share some of the same crystal lattice points in a symmetrical manner. The result is an intergrowth of two separate crystals that are tightly ...

is common and adds complexity to the observed crystal habit

In mineralogy, crystal habit is the characteristic external shape of an individual crystal or crystal group. The habit of a crystal is dependent on its crystallographic form and growth conditions, which generally creates irregularities due to l ...

s. Fluorite has four perfect cleavage planes that help produce octahedral fragments. The structural motif adopted by fluorite is so common that the motif is called the fluorite structure In solid state chemistry, the fluorite structure refers to a common motif for compounds with the formula MX2. The X ions occupy the eight tetrahedral interstitial sites whereas M ions occupy the regular sites of a face-centered cubic (FCC) struct ...

. Element substitution for the calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

often includes strontium

Strontium is the chemical element with the symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, strontium is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is ...

and certain rare-earth element

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides or sometimes the lanthanides (yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare earths), are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous silv ...

s (REE), such as yttrium

Yttrium is a chemical element with the symbol Y and atomic number 39. It is a silvery-metallic transition metal chemically similar to the lanthanides and has often been classified as a " rare-earth element". Yttrium is almost always found in c ...

and cerium.

Occurrence and mining

Fluorite forms as a late-crystallizing mineral in

Fluorite forms as a late-crystallizing mineral in felsic

In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz.Marshak, Stephen, 2009, ''Essentials of Geology,'' W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, wh ...

igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma o ...

rocks typically through hydrothermal activity. It is particularly common in granitic pegmatites. It may occur as a vein deposit formed through hydrothermal

Hydrothermal circulation in its most general sense is the circulation of hot water (Ancient Greek ὕδωρ, ''water'',Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with th ...

activity particularly in limestones. In such vein deposits it can be associated with galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It cry ...

, sphalerite

Sphalerite (sometimes spelled sphaelerite) is a sulfide mineral with the chemical formula . It is the most important ore of zinc. Sphalerite is found in a variety of deposit types, but it is primarily in sedimentary exhalative, Mississippi-Va ...

, barite, quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical ...

, and calcite

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scra ...

. Fluorite can also be found as a constituent of sedimentary rocks either as grains or as the cementing material in sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

.

It is a common mineral mainly distributed in South Africa, China, Mexico, Mongolia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Tanzania, Rwanda and Argentina.

The world reserves of fluorite are estimated at 230 million tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton ( United State ...

s (Mt) with the largest deposits being in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

(about 41 Mt), Mexico (32 Mt) and China (24 Mt). China is leading the world production with about 3 Mt annually (in 2010), followed by Mexico (1.0 Mt), Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 millio ...

(0.45 Mt), Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

(0.22 Mt), South Africa (0.13 Mt), Spain (0.12 Mt) and Namibia (0.11 Mt).

One of the largest deposits of fluorspar in North America is located on the Burin Peninsula

The Burin Peninsula ( ) is a peninsula located on the south coast of the island of Newfoundland in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Marystown is the largest population centre on the peninsula.Statistics Canada. 2017. Marystown, T ensus ...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, Canada. The first official recognition of fluorspar in the area was recorded by geologist J.B. Jukes in 1843. He noted an occurrence of "galena" or lead ore and fluoride of lime on the west side of St. Lawrence harbour. It is recorded that interest in the commercial mining of fluorspar began in 1928 with the first ore being extracted in 1933. Eventually, at Iron Springs Mine, the shafts reached depths of . In the St. Lawrence area, the veins are persistent for great lengths and several of them have wide lenses. The area with veins of known workable size comprises about .

In 2018, Canada Fluorspar Inc. commenced mine production again in St. Lawrence; in spring 2019, the company was planned to develop a new shipping port on the west side of Burin Peninsula as a more affordable means of moving their product to markets, and they successfully sent the first shipload of ore from the new port on July 31, 2021. This marks the first time in 30 years that ore has been shipped directly out of St. Lawrence.

Cubic crystals up to 20 cm across have been found at Dalnegorsk

Dalnegorsk (russian: Дальнего́рск, lit. ''far in the mountains'') is a town in Primorsky Krai, Russia. Population:

Name

It was formerly known from its founding in 1897 as Tetyukhe (russian: Те́тюхе; ; literally meaning "riv ...

, Russia. The largest documented single crystal of fluorite was a cube 2.12 meters in size and weighing approximately 16 tonnes.

In

In Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensi ...

(Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

) there are several fluorite deposits known internationally for the quality of the specimens they have yielded. In the area of Berbes, Ribadesella

Ribadesella (Asturian: Ribeseya) is a small municipality in the Autonomous Community of the Principality of Asturias, Spain. Known for its location on the Cantabrian Sea, at the outlet of the River Sella, Ribadesella is a town that forms part ...

, fluorite appears as cubic crystals, sometimes with dodecahedron modifications, which can reach a size of up to 10 cm of edge, with internal colour zoning, almost always violet in colour. It is associated with quartz and leafy aggregates of baryte. In the ''Emilio'' mine, in Loroñe, Colunga, the fluorite crystals, cubes with small modifications of other figures, are colourless and transparent. They can reach 10 cm of edge. In the ''Moscona'' mine, in Villabona, the fluorite crystals, cubic without modifications of other shapes, are yellow, up to 3 cm of edge. They are associated with large crystals of calcite and barite.

"Blue John"

One of the most famous of the older-known localities of fluorite is Castleton inDerbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the no ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, where, under the name of "Derbyshire Blue John", purple-blue fluorite was extracted from several mines or caves. During the 19th century, this attractive fluorite was mined for its ornamental value. The mineral Blue John is now scarce, and only a few hundred kilograms are mined each year for ornamental and lapidary

Lapidary (from the Latin ) is the practice of shaping stone, minerals, or gemstones into decorative items such as cabochons, engraved gems (including cameos), and faceted designs. A person who practices lapidary is known as a lapidarist. A ...

use. Mining still takes place in Blue John Cavern

The Blue John Cavern is one of the four show caves in Castleton, Derbyshire, England.

Description

The cavern takes its name from the semi-precious mineral Blue John, which is still mined in small amounts outside the tourist season and mad ...

and Treak Cliff Cavern.

Recently discovered deposits in China have produced fluorite with coloring and banding similar to the classic Blue John stone.

Fluorescence

George Gabriel Stokes

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet, (; 13 August 1819 – 1 February 1903) was an Irish English physicist and mathematician. Born in County Sligo, Ireland, Stokes spent all of his career at the University of Cambridge, where he was the Luc ...

named the phenomenon of ''fluorescence'' from fluorite, in 1852.

Many samples of fluorite exhibit fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, ...

under ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiati ...

, a property that takes its name from fluorite. Many minerals, as well as other substances, fluoresce. Fluorescence involves the elevation of electron energy levels by quanta of ultraviolet light, followed by the progressive falling back of the electrons into their previous energy state, releasing quanta of visible light in the process. In fluorite, the visible light emitted is most commonly blue, but red, purple, yellow, green, and white also occur. The fluorescence of fluorite may be due to mineral impurities, such as yttrium

Yttrium is a chemical element with the symbol Y and atomic number 39. It is a silvery-metallic transition metal chemically similar to the lanthanides and has often been classified as a " rare-earth element". Yttrium is almost always found in c ...

and ytterbium

Ytterbium is a chemical element with the symbol Yb and atomic number 70. It is a metal, the fourteenth and penultimate element in the lanthanide series, which is the basis of the relative stability of its +2 oxidation state. However, like the othe ...

, or organic matter, such as volatile hydrocarbons

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

in the crystal lattice. In particular, the blue fluorescence seen in fluorites from certain parts of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

responsible for the naming of the phenomenon of fluorescence itself, has been attributed to the presence of inclusions of divalent europium

Europium is a chemical element with the symbol Eu and atomic number 63. Europium is the most reactive lanthanide by far, having to be stored under an inert fluid to protect it from atmospheric oxygen or moisture. Europium is also the softest lanth ...

in the crystal. Natural samples containing rare earth impurities such as erbium have also been observed to display upconversion fluorescence, in which infrared light stimulates emission of visible light, a phenomenon usually only reported in synthetic materials.

One fluorescent variety of fluorite is chlorophane

Chlorophane, also sometimes known as pyroemerald, cobra stone, and pyrosmaragd, is a rare variety of the mineral fluorite with the unusual combined properties of thermoluminescence, thermophosphoresence, triboluminescence, and fluorescence: it w ...

, which is reddish or purple in color and fluoresces brightly in emerald green when heated (thermoluminescence

Thermoluminescence is a form of luminescence that is exhibited by certain crystalline materials, such as some minerals, when previously absorbed energy from electromagnetic radiation or other ionizing radiation is re-emitted as light upon h ...

), or when illuminated with ultraviolet light.

The color of visible light emitted when a sample of fluorite is fluorescing depends on where the original specimen was collected; different impurities having been included in the crystal lattice in different places. Neither does all fluorite fluoresce equally brightly, even from the same locality. Therefore, ultraviolet light is not a reliable tool for the identification of specimens, nor for quantifying the mineral in mixtures. For example, among British fluorites, those from Northumberland

Northumberland () is a ceremonial counties of England, county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Ab ...

, County Durham, and eastern Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. ...

are the most consistently fluorescent, whereas fluorite from Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

, Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the no ...

, and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlan ...

, if they fluoresce at all, are generally only feebly fluorescent.

Fluorite also exhibits the property of thermoluminescence

Thermoluminescence is a form of luminescence that is exhibited by certain crystalline materials, such as some minerals, when previously absorbed energy from electromagnetic radiation or other ionizing radiation is re-emitted as light upon h ...

.

Color

Fluorite is allochromatic, meaning that it can be tinted with elemental impurities. Fluorite comes in a wide range of colors and has consequently been dubbed "the most colorful mineral in the world". Every color of the rainbow in various shades is represented by fluorite samples, along with white, black, and clear crystals. The most common colors are purple, blue, green, yellow, or colorless. Less common are pink, red, white, brown, and black. Color zoning or banding is commonly present. The color of the fluorite is determined by factors including impurities, exposure to radiation, and the absence of voids of thecolor centers

An F center or Farbe center (from the original German ''Farbzentrum'', where ''Farbe'' means ''color'' and ''zentrum'' means center) is a type of crystallographic defect in which an anionic vacancy in a crystal lattice is occupied by one or more un ...

.

Uses

Source of fluorine and fluoride

Fluorite is a major source of hydrogen fluoride, a commodity chemical used to produce a wide range of materials. Hydrogen fluoride is liberated from the mineral by the action of concentrated sulfuric acid: :CaF2( s) + H2SO4 → CaSO4(s) + 2 HF( g) The resulting HF is converted into fluorine,fluorocarbon

Fluorocarbons are chemical compounds with carbon-fluorine bonds. Compounds that contain many C-F bonds often has distinctive properties, e.g., enhanced stability, volatility, and hydrophobicity. Fluorocarbons and their derivatives are commerci ...

s, and diverse fluoride materials. As of the late 1990s, five billion kilograms were mined annually.

There are three principal types of industrial use for natural fluorite, commonly referred to as "fluorspar" in these industries, corresponding to different grades of purity. Metallurgical grade fluorite (60–85% CaF2), the lowest of the three grades, has traditionally been used as a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ...

to lower the melting point of raw materials in steel production to aid the removal of impurities, and later in the production of aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in AmE, American and CanE, Canadian English) is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately o ...

. Ceramic grade fluorite (85–95% CaF2) is used in the manufacture of opalescent glass

Glass is a non-Crystallinity, crystalline, often transparency and translucency, transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most ...

, enamels, and cooking utensils. The highest grade, "acid grade fluorite" (97% or more CaF2), accounts for about 95% of fluorite consumption in the US where it is used to make hydrogen fluoride and hydrofluoric acid

Hydrofluoric acid is a solution of hydrogen fluoride (HF) in water. Solutions of HF are colourless, acidic and highly corrosive. It is used to make most fluorine-containing compounds; examples include the commonly used pharmaceutical antidepr ...

by reacting the fluorite with sulfuric acid.

Internationally, acid-grade fluorite is also used in the production of AlF3 and cryolite

Cryolite ( Na3 Al F6, sodium hexafluoroaluminate) is an uncommon mineral identified with the once-large deposit at Ivittuut on the west coast of Greenland, mined commercially until 1987.

History

Cryolite was first described in 1798 by Danish ve ...

(Na3AlF6), which are the main fluorine compounds used in aluminium smelting. Alumina is dissolved in a bath that consists primarily of molten Na3AlF6, AlF3, and fluorite (CaF2) to allow electrolytic recovery of aluminium. Fluorine losses are replaced entirely by the addition of AlF3, the majority of which react with excess sodium from the alumina to form Na3AlF6.Miller, M. MichaelFluorspar

USGS 2009 Minerals Yearbook

Niche uses

Lapidary uses

Natural fluorite mineral has ornamental andlapidary

Lapidary (from the Latin ) is the practice of shaping stone, minerals, or gemstones into decorative items such as cabochons, engraved gems (including cameos), and faceted designs. A person who practices lapidary is known as a lapidarist. A ...

uses. Fluorite may be drilled into beads and used in jewelry, although due to its relative softness it is not widely used as a semiprecious stone. It is also used for ornamental carvings, with expert carvings taking advantage of the stone's zonation.

Optics

In the laboratory, calcium fluoride is commonly used as a window material for bothinfrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from aroun ...

and ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiati ...

wavelengths, since it is transparent in these regions (about 0.15 µm to 9 µm) and exhibits an extremely low change in refractive index

In optics, the refractive index (or refraction index) of an optical medium is a dimensionless number that gives the indication of the light bending ability of that medium.

The refractive index determines how much the path of light is bent, o ...

with wavelength. Furthermore, the material is attacked by few reagents. At wavelengths as short as 157 nm, a common wavelength used for semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical conductivity value falling between that of a conductor, such as copper, and an insulator, such as glass. Its resistivity falls as its temperature rises; metals behave in the opposite way. ...

stepper manufacture for integrated circuit lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone ( lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German ...

, the refractive index of calcium fluoride shows some non-linearity at high power densities, which has inhibited its use for this purpose. In the early years of the 21st century, the stepper market for calcium fluoride collapsed, and many large manufacturing facilities have been closed. Canon and other manufacturers have used synthetically grown crystals of calcium fluoride components in lenses to aid apochromatic design, and to reduce light dispersion. This use has largely been superseded by newer glasses and computer-aided design. As an infrared optical material, calcium fluoride is widely available and was sometimes known by the Eastman Kodak

The Eastman Kodak Company (referred to simply as Kodak ) is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in analogue photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorpor ...

trademarked name "Irtran-3", although this designation is obsolete.

Fluorite should not be confused with fluoro-crown (or fluorine crown) glass, a type of low-dispersion glass that has special optical properties approaching fluorite. True fluorite is not a glass but a crystalline material. Lenses or optical groups made using this low dispersion glass as one or more elements exhibit less chromatic aberration

In optics, chromatic aberration (CA), also called chromatic distortion and spherochromatism, is a failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same point. It is caused by dispersion: the refractive index of the lens elements varies with the ...

than those utilizing conventional, less expensive crown glass and flint glass

Flint glass is optical glass that has relatively high refractive index and low Abbe number (high dispersion). Flint glasses are arbitrarily defined as having an Abbe number of 50 to 55 or less. The currently known flint glasses have refracti ...

elements to make an achromatic lens

An achromatic lens or achromat is a lens that is designed to limit the effects of chromatic and spherical aberration. Achromatic lenses are corrected to bring two wavelengths (typically red and blue) into focus on the same plane.

The most com ...

. Optical groups employ a combination of different types of glass; each type of glass refracts light in a different way. By using combinations of different types of glass, lens manufacturers are able to cancel out or significantly reduce unwanted characteristics; chromatic aberration being the most important. The best of such lens designs are often called apochromatic (see above). Fluoro-crown glass (such as Schott FK51) usually in combination with an appropriate "flint" glass (such as Schott KzFSN 2) can give very high performance in telescope objective lenses, as well as microscope objectives, and camera telephoto lenses. Fluorite elements are similarly paired with complementary "flint" elements (such as Schott LaK 10). The refractive qualities or fluorite and of certain flint elements provide a lower and more uniform dispersion across the spectrum of visible light, thereby keeping colors focused more closely together. Lenses made with fluorite are superior to fluoro-crown based lenses, at least for doublet telescope objectives; but are more difficult to produce and more costly.

The use of fluorite for prisms and lenses was studied and promoted by Victor Schumann near the end of the 19th century. Naturally occurring fluorite crystals without optical defects were only large enough to produce microscope objectives.

With the advent of synthetically grown fluorite crystals in the 1950s - 60s, it could be used instead of glass in some high-performance optical telescope

An optical telescope is a telescope that gathers and focuses light mainly from the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum, to create a magnified image for direct visual inspection, to make a photograph, or to collect data through electr ...

and camera lens

A camera lens (also known as photographic lens or photographic objective) is an optical lens or assembly of lenses used in conjunction with a camera body and mechanism to make images of objects either on photographic film or on other media capa ...

elements. In telescopes, fluorite elements allow high-resolution images of astronomical objects at high magnification

Magnification is the process of enlarging the apparent size, not physical size, of something. This enlargement is quantified by a calculated number also called "magnification". When this number is less than one, it refers to a reduction in si ...

s. Canon Inc. produces synthetic fluorite crystals that are used in their better telephoto lenses. The use of fluorite for telescope lenses has declined since the 1990s, as newer designs using fluoro-crown glass, including triplets, have offered comparable performance at lower prices. Fluorite and various combinations of fluoride compounds can be made into synthetic crystals which have applications in lasers and special optics for UV and infrared.

Exposure tools for the semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical conductivity value falling between that of a conductor, such as copper, and an insulator, such as glass. Its resistivity falls as its temperature rises; metals behave in the opposite way. ...

industry make use of fluorite optical elements for ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiati ...

at wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

s of about 157 nanometer

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the molecular scale.

The nanometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: nm) or nanometer (American and British English spelling differences#-re, ...

s. Fluorite has a uniquely high transparency at this wavelength. Fluorite objective lenses are manufactured by the larger microscope firms (Nikon, Olympus

Olympus or Olympos ( grc, Ὄλυμπος, link=no) may refer to:

Mountains

In antiquity

Greece

* Mount Olympus in Thessaly, northern Greece, the home of the twelve gods of Olympus in Greek mythology

* Mount Olympus (Lesvos), located in Les ...

, Carl Zeiss

Carl Zeiss (; 11 September 1816 – 3 December 1888) was a German scientific instrument maker, optician and businessman. In 1846 he founded his workshop, which is still in business as Carl Zeiss AG. Zeiss gathered a group of gifted practica ...

and Leica). Their transparence to ultraviolet light enables them to be used for fluorescence microscopy

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. "Fluorescence micr ...

. The fluorite also serves to correct optical aberrations in these lenses. Nikon

(, ; ), also known just as Nikon, is a Japanese multinational corporation headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, specializing in optics and imaging products. The companies held by Nikon form the Nikon Group.

Nikon's products include cameras, camera ...

has previously manufactured at least one fluorite and synthetic quartz element camera lens (105 mm f/4.5 UV) for the production of ultraviolet images. Konica produced a fluorite lens for their SLR cameras – the Hexanon 300 mm f/6.3.

Source of fluorine gas in nature

In 2012, the first source of naturally occurring fluorine gas was found in fluorite mines in Bavaria, Germany. It was previously thought that fluorine gas did not occur naturally because it is so reactive, and would rapidly react with other chemicals. Fluorite is normally colorless, but some varied forms found nearby look black, and are known as 'fetid fluorite' orantozonite

Antozonite (historically known as Stinkspat, Stinkfluss, Stinkstein, Stinkspar and fetid fluorite) is a radioactive fluorite variety first found in Wölsendorf, Bavaria, in 1841, and named in 1862.

It is characterized by the presence of multipl ...

. The minerals, containing small amounts of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weakly ...

and its daughter products, release radiation sufficiently energetic to induce oxidation of fluoride anions within the structure, to fluorine that becomes trapped inside the mineral. The color of fetid fluorite is predominantly due to the calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

atoms remaining. Solid-state fluorine-19 NMR carried out on the gas contained in the antozonite, revealed a peak at 425 ppm, which is consistent with F2.Withers, Neil (1 July 2012Fluorine finally found in nature , Chemistry World

Rsc.org.

Images

See also

* List of countries by fluorite production *List of minerals

This is a list of minerals for which there are articles on Wikipedia.

Minerals are distinguished by various chemical and physical properties. Differences in chemical composition and crystal structure distinguish the various ''species''. Within a m ...

*Magnesium fluoride

Magnesium fluoride is an inorganic compound with the formula MgF2. The compound is a white crystalline salt and is transparent over a wide range of wavelengths, with commercial uses in optics that are also used in space telescopes. It occurs natu ...

– also used in UV optics

References

External links

Educational article about the different colors of fluorites crystals from Asturias, Spain

an

Crawford Cup

related Roman cups at

British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docume ...

{{Authority control

Cubic minerals

Minerals in space group 225

Evaporite

Fluorine minerals

Luminescent minerals

Industrial minerals

Symbols of Illinois