Florida In The Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A formal Ordinance of Secession was introduced for debate on January 8. The primary topic of debate was whether Florida should immediately secede or wait until other southern states such as Alabama officially chose to secede. Outspoken supporters of secession at the conference included Governor Perry and Governor-elect

A formal Ordinance of Secession was introduced for debate on January 8. The primary topic of debate was whether Florida should immediately secede or wait until other southern states such as Alabama officially chose to secede. Outspoken supporters of secession at the conference included Governor Perry and Governor-elect  Afterward, the Florida secession convention formed a committee to draft a declaration of causes, but the committee was discharged before completing the task. Only an undated, untitled draft remains. During the secession convention, president John McGehee stated: "At the South and with our people, of course, slavery is the element of all value, and a destruction of that destroys all that is property. This party, now soon to take possession of the powers of government, is sectional, irresponsible to us, and, driven on by an infuriated, fanatical madness that defies all opposition, must inevitably destroy every vestige of right growing out of property in slaves.”

The delegates adopted a new state constitution and within a month the state joined other southern states to form the

Afterward, the Florida secession convention formed a committee to draft a declaration of causes, but the committee was discharged before completing the task. Only an undated, untitled draft remains. During the secession convention, president John McGehee stated: "At the South and with our people, of course, slavery is the element of all value, and a destruction of that destroys all that is property. This party, now soon to take possession of the powers of government, is sectional, irresponsible to us, and, driven on by an infuriated, fanatical madness that defies all opposition, must inevitably destroy every vestige of right growing out of property in slaves.”

The delegates adopted a new state constitution and within a month the state joined other southern states to form the

As Florida was an important supply route for the

As Florida was an important supply route for the

Governor Milton also worked to strengthen the state

Governor Milton also worked to strengthen the state  On October 9, Confederates, including the

On October 9, Confederates, including the

As a result of Florida's limited strategic importance, the

As a result of Florida's limited strategic importance, the  The 2nd Florida Infantry was first commanded by convention delegate G. T. Ward. He participated in the Yorktown siege, and died after being shot at the

The 2nd Florida Infantry was first commanded by convention delegate G. T. Ward. He participated in the Yorktown siege, and died after being shot at the

After Antietam, the 2nd, 5th, and 8th were grouped together under

After Antietam, the 2nd, 5th, and 8th were grouped together under  At Fredericksburg, the 8th regiment, whose Company C was commanded by David Lang protected the city from General

At Fredericksburg, the 8th regiment, whose Company C was commanded by David Lang protected the city from General  Lang took command of the Florida Brigade. The Florida Brigade served through the Gettysburg Campaign and twice charged

Lang took command of the Florida Brigade. The Florida Brigade served through the Gettysburg Campaign and twice charged

In early 1862, the Confederate government pulled General Bragg's small army from Pensacola following successive Confederate defeats in

In early 1862, the Confederate government pulled General Bragg's small army from Pensacola following successive Confederate defeats in

The Union gunboat sailed up

The Union gunboat sailed up

The flotilla arrived at the mouth of the St. John' s River on October 1, where Cdr. Charles Steedman' s gunboats—Paul Jones, Cimarron, Uncas, Patroon, Hale, and Water Witch—joined them. Brannan landed troops at Mayport Mills. The Bluff held off the Naval squadron until the troops were landed to come up behind it, the Confederates quietly abandoned the work.

In January 1863, there was a skirmish at Township Landing with the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. On March 9, 1863, 80 Confederates were driven off by 120 men of the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers near St. Augustine.

On 28 July 1863, ''Sagamore'' and attacked New Smyrna.

The flotilla arrived at the mouth of the St. John' s River on October 1, where Cdr. Charles Steedman' s gunboats—Paul Jones, Cimarron, Uncas, Patroon, Hale, and Water Witch—joined them. Brannan landed troops at Mayport Mills. The Bluff held off the Naval squadron until the troops were landed to come up behind it, the Confederates quietly abandoned the work.

In January 1863, there was a skirmish at Township Landing with the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. On March 9, 1863, 80 Confederates were driven off by 120 men of the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers near St. Augustine.

On 28 July 1863, ''Sagamore'' and attacked New Smyrna.

The

The

Seymour's relatively high losses caused

Seymour's relatively high losses caused

Convention delegate James O. Devall owned ''General Sumpter'', the first steamboat in Palatka, which was captured by in March 1864. Palatka was occupied, and there were two picket attacks in late March. Union troops utilized Sunny Point, and St. Mark's was used as a barracks.

The first mine casualty of the war was at Jacksonville on April 1, 1864. ''General Hunter'' was sunk on April 16, close to where ''Maple Leaf'' was sunk.

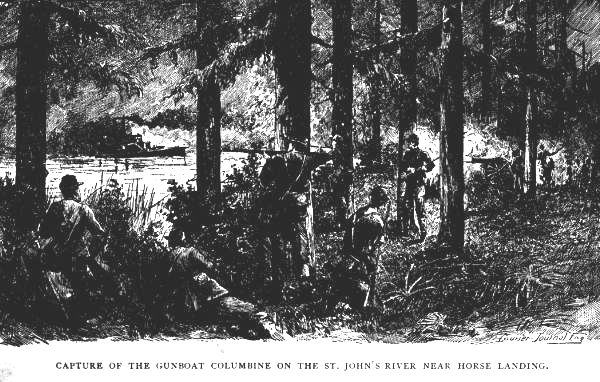

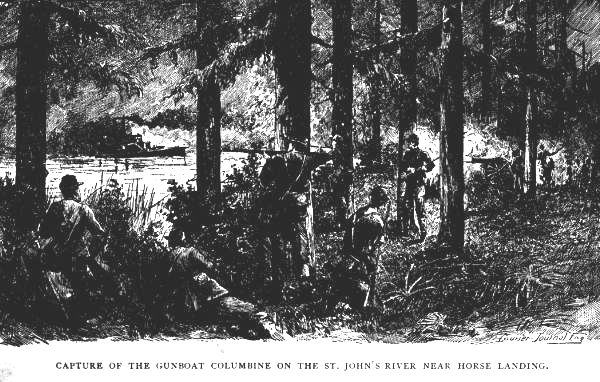

On May 19, there was a skirmish with the 17th Connecticut in Welaka, and a skirmish in Saunders. On May 21, spy Lola Sanchez got wind of a Union raid, and the Columbine was captured by Dickison's forces at the "Battle of Horse Landing".

Convention delegate James O. Devall owned ''General Sumpter'', the first steamboat in Palatka, which was captured by in March 1864. Palatka was occupied, and there were two picket attacks in late March. Union troops utilized Sunny Point, and St. Mark's was used as a barracks.

The first mine casualty of the war was at Jacksonville on April 1, 1864. ''General Hunter'' was sunk on April 16, close to where ''Maple Leaf'' was sunk.

On May 19, there was a skirmish with the 17th Connecticut in Welaka, and a skirmish in Saunders. On May 21, spy Lola Sanchez got wind of a Union raid, and the Columbine was captured by Dickison's forces at the "Battle of Horse Landing".

New York's 14th cavalry lost in a skirmish at Cow Ford Creek on April 2. The

New York's 14th cavalry lost in a skirmish at Cow Ford Creek on April 2. The

Confederates occupied Gainesville after the

Confederates occupied Gainesville after the

In March 1865

In March 1865

On May 20, General McCook read Lincoln's

On May 20, General McCook read Lincoln's

Cannonball

a

A History of Central Florida Podcast

''Florida and the Civil War''

open access digital collection of materials from the PK Yonge Library of Florida History

Florida Memory Project - State Archives

Journal of the Secession Convention

{{DEFAULTSORT:Florida In The American Civil War .American Civil War American Civil War by state

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

participated in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

as a member of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. It had been admitted to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

as a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

in 1845. In January 1861, Florida became the third Southern state to secede

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a polity, political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former republics of ...

from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

after the November 1860 presidential election victory of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. It was one of the initial seven slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

which formed the Confederacy on February 8, 1861, in advance of the American Civil War.

Florida had by far the smallest population of the Confederate states with about 140,000 residents, nearly half of them enslaved people. As such, Florida sent around 15,000 troops to the Confederate army, the vast majority of which were deployed elsewhere during the war. The state's chief importance was as a source of cattle and other food supplies for the Confederacy, and as an entry and exit location for blockade-runners who used its many bays and small inlets to evade the Union Navy.

At the outbreak of war, the Confederate government seized many United States facilities in the state, though the Union retained control of Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Pickens

Fort Pickens is a pentagonal historic United States military fort on Santa Rosa Island in the Pensacola, Florida, area. It is named after American Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. The fort was completed in 1834 and was one of the few ...

for the duration of the conflict. The Confederate strategy was to defend the vital farms in the interior of Florida at the expense of coastal areas. As the war progressed and southern resources dwindled, forts and towns along the coast were increasingly left undefended, allowing Union forces to occupy them with little or no resistance. Fighting in Florida was largely limited to small skirmishes with the exception of the Battle of Olustee

The Battle of Olustee or Battle of Ocean Pond was fought in Baker County, Florida on February 20, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the largest battle fought in Florida during the war.

Union General Truman Seymour had landed troops a ...

, fought near Lake City in February 1864, when a Confederate army of over 5,000 repelled a Union attempt to disrupt Florida's food-producing region. Wartime conditions made it easier for enslaved people to escape, and many became useful informants to Union commanders. Deserters from both sides took refuge in the Florida wilderness, often attacking Confederate units and looting farms.

The war ended in April 1865. By the following month, United States control of Florida had been re-established, slavery had been abolished, and Florida's Confederate governor John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

had committed suicide by gunshot. Florida was formally readmitted to the United States in 1868.

Background

Florida had been a Spanish territory for 300 years before being transferred to the United States in 1821. The population at the time was quite small, with most residents concentrated in the towns of St. Augustine on the Atlantic coast andPensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

on the western end of the panhandle. The interior of the Florida Territory

The Territory of Florida was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 30, 1822, until March 3, 1845, when it was admitted to the Union as the state of Florida. Originally the major portion of the Spanish te ...

was home to the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

and Black Seminole

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

along with scattered pioneers. Steamboat navigation was well established on the Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River is a river, approximately 160 mi (180 km) long in the state of Florida. The river's large watershed, known as the ACF River Basin, drains an area of approximately into the Gulf of Mexico. The distance to its fa ...

and St. Johns River

The St. Johns River ( es, Río San Juan) is the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida and its most significant one for commercial and recreational use. At long, it flows north and winds through or borders twelve counties. The drop in eleva ...

and railroads were planned, but transportation through the interior remained very difficult and growth was slow. A series of wars to forcibly remove the Seminoles from their lands raged off and on from the 1830s until the 1850s, further slowing development.

By 1840, the English-speaking population of Florida outnumbered those of Spanish colonial descent. The overall population had reached 54,477 people, with African slaves making up almost one-half.

Florida was admitted to the union as the 27th state on March 3, 1845, when it had a population of 66,500, including about 30,000 people held in slavery. By 1861, Florida's population had increased to about 140,000, of which about 63,000 were enslaved persons. Their forced labor accounted for 85 percent of the state's cotton production, with most large slave-holding plantations concentrated in middle Florida, a swath of fertile farmland stretching across the northern panhandle approximately centered on the state capital at Tallahassee

Tallahassee ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2020, the population ...

.

1860 U.S. presidential election

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally mu ...

walked out of the 1860 Democratic National Convention

The 1860 Democratic National Conventions were a series of presidential nominating conventions held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1860 election. The first convention, held from April 23 t ...

, and later nominated U.S. Vice President John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

to run for their party. While Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

won the 1860 U.S. presidential election, Breckinridge won in Florida. Within days of the election, a large gathering of Marion County pioneers was held in Ocala to demand secession. Its motions were brought to the attention of the Florida House of Representatives by Rep. Daniel A. Vogt.

Secession and confederation

Although theCompromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

was unpopular in Florida, the secession movement in 1851 and 1852 did not gain much traction. A series of events in subsequent years exacerbated divisions. By January 1860, talk of conflict had progressed to the point that Senators Stephen Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was a Democratic senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War. For much of that period, he was chairman of the Committee on Na ...

and David Levy Yulee

David Levy Yulee (born David Levy; June 12, 1810 – October 10, 1886) was an American politician and attorney. Born on the island of St. Thomas, then under British control, he was of Sephardic Jewish ancestry: His father was a Sephardi from Mo ...

jointly requested from the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* Dep ...

a statement of munitions and equipment in Florida forts.

Following the election of Lincoln, a special secession convention formally known as the "Convention of the People of Florida" was called by Governor Madison S. Perry

Madison Starke Perry (1814 – March 1865) was the fourth Governor of Florida.

Early life

Madison Starke Perry was born in Lancaster County, South Carolina, the youngest child of Benjamin Perry and his wife Mary Starke. He attended South Car ...

to discuss secession from the Union. Delegates were selected in a statewide election, and met in Tallahassee on January 3, 1861. Virginia planter and firebrand Edmund Ruffin

Edmund Ruffin III (January 5, 1794 – June 18, 1865) was a wealthy Virginia planter who served in the Virginia Senate from 1823 to 1827. In the last three decades before the American Civil War, his pro-slavery writings received more attention tha ...

came to the convention to advocate for secession. Fifty-one of the 69 convention members held slaves in 1860. Just seven of the delegates were born in Florida.

On January 5, McQueen McIntosh introduced a series of resolutions defining the purpose of the convention and the constitutionality of secession. John C. McGehee, who was involved in drafting Florida's original constitution and became a judge, was elected the convention president. Leonidas W. Spratt of South Carolina gave an impassioned speech for secession. Edward Bullock

Edward Courtenay Bullock (December 7, 1822 – December 23, 1861) was an American politician and Confederate officer in the American Civil War.

Biography

Bullock, a native of South Carolina, came to Alabama shortly after graduating from Harvar ...

of Alabama also spoke to conventioneers. William S. Harris was the convention's secretary. On January 7, the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of immediate secession, delegates voting sixty-two to seven to withdraw Florida from the Union.

The group with the most sway that opposed secession in Florida was the Constitutional Union Party, which had several supporting newspapers including Tallahassee's Florida Sentinel. The party held it's convention in June 1860 and had nominated the editor of the Sentinel, Benjamin F. Allen, for Congress. Despite being against secession, the party was composed mostly of slave-owning planters and conservative democrats.

Individuals who opposed secession included Conservative plantation owner and former Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

military commander Richard Keith Call

Richard Keith Call (October 24, 1792 – September 14, 1862) was an American attorney, politician, and slave owner who served as the 3rd and 5th territorial governor of Florida. Before that, he was elected to the Florida Territorial Council and a ...

, who advocated for restraint and judiciousness. His daughter Ellen Call Long wrote that upon being told of the vote outcome by its supporters, Call raised his cane above his head and told the delegates who came to his house, "And what have you done? You have opened the gates of hell, from which shall flow the curses of the damned, which shall sink you to perdition." In response, Call, and others against secession, were called names like "submissionists" and "Union Shriekers." Pro-unionists in Florida not only faced public ridicule, some could be attacked and even killed. One example was the case of William Hollingsworth who was shot at and seriously wounded by a group of secessionists who called themselves regulators.

A formal Ordinance of Secession was introduced for debate on January 8. The primary topic of debate was whether Florida should immediately secede or wait until other southern states such as Alabama officially chose to secede. Outspoken supporters of secession at the conference included Governor Perry and Governor-elect

A formal Ordinance of Secession was introduced for debate on January 8. The primary topic of debate was whether Florida should immediately secede or wait until other southern states such as Alabama officially chose to secede. Outspoken supporters of secession at the conference included Governor Perry and Governor-elect John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

. Jackson Morton

Jackson Morton (August 10, 1794 – November 20, 1874) was an American politician. A member of the Whig Party, he represented Florida as a U.S. Senator from 1849 to 1855. He also served as a Deputy from Florida to the Provisional Congress of th ...

and George Taliaferro Ward attempted to have the ordinance amended so that Florida would not secede before Georgia and Alabama, but their proposal was voted down. When Ward signed the Ordinance he stated "When I die, I want it inscribed upon my tombstone that I was the last man to give up the ship."

On January 10, 1861, the delegates formally adopted the Ordinance of Secession, which declared that the "nation of Florida" had withdrawn from the "American union." Florida was the third state to secede, following South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. By the following month, six states had seceded; These six had the largest population of enslaved people among the Southern states.

Secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

was declared and a public ceremony held on the east steps of the Florida capitol

The Florida State Capitol in Tallahassee, Florida, is an architecturally and historically significant building listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Capitol is at the intersection of Apalachee Parkway and South ...

the following day; an Ordinance of Secession

An Ordinance of Secession was the name given to multiple resolutions drafted and ratified in 1860 and 1861, at or near the beginning of the Civil War, by which each seceding Southern state or territory formally declared secession from the United ...

was signed by 69 people. The public in Tallahassee celebrated the announcement of secession with fireworks and a large parade.The secession ordinance of Florida simply declared its severing of ties with the federal Union, without stating any causes. According to historian William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's secession, as well as for the creation of the Confederacy itself. Supporters of secession included the '' St. Augustine Examiner''. The governors of Georgia and Mississippi sent telegrams affirming support for immediate secession.

Afterward, the Florida secession convention formed a committee to draft a declaration of causes, but the committee was discharged before completing the task. Only an undated, untitled draft remains. During the secession convention, president John McGehee stated: "At the South and with our people, of course, slavery is the element of all value, and a destruction of that destroys all that is property. This party, now soon to take possession of the powers of government, is sectional, irresponsible to us, and, driven on by an infuriated, fanatical madness that defies all opposition, must inevitably destroy every vestige of right growing out of property in slaves.”

The delegates adopted a new state constitution and within a month the state joined other southern states to form the

Afterward, the Florida secession convention formed a committee to draft a declaration of causes, but the committee was discharged before completing the task. Only an undated, untitled draft remains. During the secession convention, president John McGehee stated: "At the South and with our people, of course, slavery is the element of all value, and a destruction of that destroys all that is property. This party, now soon to take possession of the powers of government, is sectional, irresponsible to us, and, driven on by an infuriated, fanatical madness that defies all opposition, must inevitably destroy every vestige of right growing out of property in slaves.”

The delegates adopted a new state constitution and within a month the state joined other southern states to form the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. Florida's Senator Mallory was selected to be Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

in the first Confederate cabinet under president Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

. The convention had further meetings in 1861 and into 1862. There was a Unionist minority in the state, an element that grew as the war progressed.

Florida sent a three-man delegation to the 1861-62 Provisional Confederate Congress

The Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, also known as the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America, was a congress of deputies and delegates called together from the Southern States which became the governing body ...

, which first met in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

, and then in the new capital of Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. The delegation consisted of Jackson Morton, James Byeram Owens

James Byeram Owens ( c. 1816 – August 1, 1889) was a slaveowner and American politician who served as a Deputy from Florida to the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1862. He mounted legal arguments in defense of seces ...

, and James Patton Anderson

James Patton Anderson (February 16, 1822 – September 20, 1872) was an American slave owner, physician, lawyer, and politician, most notably serving as a United States Congressman from the Washington Territory, a Mississippi state legislator, ...

, who resigned April 8, 1861, and was replaced by G. T. Ward. Ward served from May 1861 until February 1862, when he resigned and was replaced by John Pease Sanderson.

In June 1861, the Confederate government split Florida up into military districts led by Confederate commanders who were given the power to requisition soldiers from the governor, more specifically from the state's militia. By March 1862, the state convention had abolished the state militia in an effort to create a more unified Confederate military organization.

Civil War

Blockade

As Florida was an important supply route for the

As Florida was an important supply route for the Confederate army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

, Union forces operated a blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

around the entire state. The 8,436-mile coastline and 11,000 miles of rivers, streams, and waterways proved a haven for blockade runners and a daunting task for patrols by Federal warships.

Governor John Milton, an ardent secessionist, throughout the war stressed the importance of Florida as a supplier of goods, rather than personnel. Florida was a large provider of food (particularly beef cattle) and salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

for the Confederate Army. The Confederates also attempted to use the close proximity of Florida with Cuba to continue trade with Spain and the rest of Europe and to develop relationships with the Spanish government in the hopes that they would help the Confederate war effort or, at the least, not hamper it.

Union troops occupied major ports such as Apalachicola, Cedar Key

Cedar Key is a city in Levy County, Florida, United States. The population was 702 at the 2010 census. The Cedar Keys are a cluster of islands near the mainland. Most of the developed area of the city has been on Way Key since the end of the 19th ...

, Jacksonville

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

, Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, and Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

early in the war. had blockade duty in Apalachicola, and, in January 1862, was part of a Union naval force which landed in Cedar Key and burned several ships, a pier, and flatcars.

Slavery

The majority of enslaved people, much like the majority of the white population, resided in North Florida during the war, while Southern Florida, aside from Key West, remained a largely "undeveloped frontier." Confederate authorities used enslaved people as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many enslaved people working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the war. In particular, many enslaved people fled to Key West because of the relatively large free black population (the 1860 census for Key West lists 2302 white people, 435 enslaved people, and 156 free black people) and the presence of a Union garrison. The Union army utilized slave labor south of the Mason Dixon line. During 1861 and 1862, the Department of War's payroll showed thatFort Zachary Taylor

The Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park, better known simply as Fort Taylor (or Fort Zach to locals), is a Florida State Park and National Historic Landmark centered on a Civil War-era fort located near the southern tip of Key West, Florida. ...

averaged forty-five slave laborers per month. Beginning in 1862, Union military activity in East and West Florida encouraged enslaved people in plantation areas to flee their owners in search of freedom. Planter fears of uprisings by enslaved people increased as the war went on.

Some worked on Union ships and, beginning in 1863, more than a thousand enlisted as soldiers in the United States Colored Troops

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed primarily of African-American (colored) soldiers, although members of other minority groups also served within the units. They were first recruited during ...

(USCT) or as sailors in the Union Navy

), (official)

, colors = Blue and gold

, colors_label = Colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

. Companies D and I of the 2nd USCT were moved from their station at Key West to Fort Myers

Fort Myers (or Ft. Myers) is a city in southwestern Florida and the county seat and commercial center of Lee County, Florida, United States. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 92,245 in 20 ...

on April 20, 1864. These men would go on to help disrupt the Confederate cattle supply and help free enslaved people in the area. In mid-May 1864, a delegation of Miccosukee

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

entered Fort Myers and told Union officers there that they had been lied to and treated poorly by the Confederates. The appearance of black soldiers as part of the garrison there helped further convince the Native Americans to work with Federal troops rather than their Confederate counterparts.

In January 1865, Union General William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

issued Special Field Orders No. 15

Special Field Orders, No. 15 (series 1865) were military orders issued during the American Civil War, on January 16, 1865, by General William Tecumseh Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi of the United States Army. They p ...

that set aside a portion of Florida as designated territory for runaway and freed former enslaved people who had accompanied his command during its March to the Sea. These controversial orders were not enforced in Florida, and were later revoked by President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

.

Deserters

Growing public dissatisfaction with Confederate conscription and impressment policies encouraged desertion by Confederate soldiers. Several Florida counties became havens for Florida deserters, as well as deserters from other Confederate states. Deserter bands attacked Confederate patrols, launched raids on plantations, confiscated slaves, stole cattle, and provided intelligence to Union army units and naval blockaders. Although most deserters formed their own raiding bands or simply tried to remain free from Confederate authorities, other deserters and Unionist Floridians, joined regular Federal units for military service in Florida.Battles

Overall, the state raised some 15,000 troops for the Confederacy, which were organized into twelveregiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s of infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

and two of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

, as well as several artillery batteries

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to faci ...

and supporting units. The state's small population (140,000 residents, the fewest in the Confederacy), relatively remote location, and meager industry limited its overall strategic importance. Battles in Florida were mostly numerous small skirmishes, as neither army aggressively sought control of the state.

Forts and Other Military Installations

Governor Milton also worked to strengthen the state

Governor Milton also worked to strengthen the state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and to improve fortifications and key defensive positions. Confederate forces moved quickly to seize control of many of Florida's U.S. Army forts, succeeding in most cases, with the significant exceptions of Fort Jefferson, Fort Pickens

Fort Pickens is a pentagonal historic United States military fort on Santa Rosa Island in the Pensacola, Florida, area. It is named after American Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. The fort was completed in 1834 and was one of the few ...

and Fort Zachary Taylor

The Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park, better known simply as Fort Taylor (or Fort Zach to locals), is a Florida State Park and National Historic Landmark centered on a Civil War-era fort located near the southern tip of Key West, Florida. ...

, which stayed firmly in Federal control throughout the war.

On January 6, 1861, state troops seized the Federal arsenal located in Chattahoochee

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the con ...

. On January 10, 1861, the day Florida declared its secession, Union general Adam J. Slemmer

Adam Jacoby Slemmer (January 24, 1828 – October 7, 1868) was an officer in the United States Army during the Seminole Wars and the American Civil War, as well as in the Old West.

Early years

Slemmer was born in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, ...

destroyed over of gunpowder at Fort McRee

Fort McRee was a historic military fort constructed by the United States on the eastern tip of Perdido Key to defend Pensacola and its important natural harbor. In the defense of Pensacola Bay, Fort McRee was accompanied by Fort Pickens, located a ...

. He then spiked the guns

A touch hole, also called a vent, is a small hole at the rear (breech) portion of the barrel of a muzzleloading gun or cannon. The hole provides external access of an ignition spark into the breech chamber of the barrel (where the combustion o ...

at Fort Barrancas

Fort Barrancas (1839) or Fort San Carlos de Barrancas (from 1787) is a United States military fort and National Historic Landmark in the former Warrington area of Pensacola, Florida, located physically within Naval Air Station Pensacola, which wa ...

and moved his force to Fort Pickens. Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Weste ...

commanded the Battle of Pensacola.

On October 9, Confederates, including the

On October 9, Confederates, including the 1st Florida Infantry

The 1st Florida Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment raised by the Confederate state of Florida during the American Civil War. Raised for 12 months of service its remaining veterans served in the 1st (McDonell's) Battalion, Florida Infantry f ...

, commanded by convention delegate James Patton Anderson, tried to take the fort at the Battle of Santa Rosa Island

The Battle of Santa Rosa Island (October 9, 1861) was an unsuccessful Confederate attempt to take Union-held Fort Pickens on Santa Rosa Island, Florida.

Background

Santa Rosa Island is a 40-mile barrier island in the U.S. state of Florida, t ...

. They were unsuccessful, and Harvey Brown planned a counter. On November 22, all Union guns at Fort Pickens and two ships, the and , targeted Fort McRee.

On January 1, there was an artillery duel in Pensacola. Twenty-eight gunboats commanded by Commodore Samuel Dupont

Samuel Francis Du Pont (September 27, 1803 – June 23, 1865) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy, and a member of the prominent Du Pont family. In the Mexican–American War, Du Pont captured San Diego, and was made commander of the Ca ...

occupied Fort Clinch

Fort Clinch is a 19th-century masonry Coastal defence and fortification, coastal fortification, built as part of the Seacoast Defense (US)#Third system, Third System of seacoast defense conceived by the United States. It is located on a peninsula n ...

at Fernandina Beach Fernandina may refer to:

*Fernandina Beach, Florida

**Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site

*Fernandina Island, Galapagos Islands

*Fernandina (fruit), a citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae ...

in March 1862. On March 11, the Union captured St. Augustine and Fort Marion

The Castillo de San Marcos (Spanish for "St. Mark's Castle") is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States; it is located on the western shore of Matanzas Bay in the city of St. Augustine, Florida.

It was designed by the Spanish ...

. Before falling into Union hands, many ethnic Minorcans

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capita ...

from St. Augustine, as well as other civilians, signed on as volunteers with a militia unit called the St. Augustine Blues. This company would eventually become a part of the 3rd Florida Infantry Regiment.

Skirmish of the Brick Church

The first land engagement in Northeast Florida and first Confederate victory in Florida was the Skirmish of the Brick Church, fought by the 3rd Florida Infantry, commanded by convention delegate Col. William S. Dilworth. Delegate Arthur J.T. Wright was an officer.Eastern Theater

As a result of Florida's limited strategic importance, the

As a result of Florida's limited strategic importance, the 2nd

A second is the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI).

Second, Seconds or 2nd may also refer to:

Mathematics

* 2 (number), as an ordinal (also written as ''2nd'' or ''2d'')

* Second of arc, an angular measurement unit ...

, 5th, and 8th

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

In mathematics

8 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being , , and . It is twice 4 or four times 2.

* a power of two, being 2 (two cubed), and is the first number of t ...

Florida Infantries were sent to serve in the Eastern Theater in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

. They fought at Second Manassas

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

The 2nd Florida Infantry was first commanded by convention delegate G. T. Ward. He participated in the Yorktown siege, and died after being shot at the

The 2nd Florida Infantry was first commanded by convention delegate G. T. Ward. He participated in the Yorktown siege, and died after being shot at the Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first pitc ...

, the first battle of the Peninsula Campaign.

Richard K. Call's son-in-law Theodore W. Brevard Jr. was captain of the 2nd's Company D, the "Leon Rifles" at Yorktown and Williamsburg, leaving shortly after. Francis P. Fleming was a private in the 2nd. Convention delegate Thomas M. Palmer was the 2nd's surgeon.

Roger A. Pryor commanded the 2nd during the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, command ...

. After Second Manassas, Pryor wrote “The Second, Fifth and Eighth (Florida) Regiments, though never under fire, exhibited the cool and collected courage of veterans."

Delegate Andrew J. Lea was captain of the 5th's Company D. Delegates Thompson Bird Lamar and William T. Gregory served with the 5th at Antietam. Lamar was wounded and Gregory was killed.

=Perry's Florida Brigade

= After Antietam, the 2nd, 5th, and 8th were grouped together under

After Antietam, the 2nd, 5th, and 8th were grouped together under Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Edward A. Perry

Edward Aylesworth Perry (March 15, 1831October 15, 1889) was a general under Robert E. Lee during the American Civil War and the 14th Governor of Florida.

Early life

He was a descendant of Arthur Perry, one of the earliest settlers of New Engl ...

. Perry's Florida Brigade served in Anderson’s Division of the First Corps under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

.

At Fredericksburg, the 8th regiment, whose Company C was commanded by David Lang protected the city from General

At Fredericksburg, the 8th regiment, whose Company C was commanded by David Lang protected the city from General Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

, contesting Federal attempts to lay pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the entir ...

. An artillery shell fragment struck the chimney of the building that Lang occupied, and a large chunk of masonry struck him in the head, gravely injuring him. He was promoted to commander of the 8th.

After Chancellorsville, Perry was stricken with typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

. Perry wrote "The firm and steadfast courage exhibited, especially by the Fifth and Second Florida Regiments, in the charge at Chancellorsville, attracted my attention."

Lang took command of the Florida Brigade. The Florida Brigade served through the Gettysburg Campaign and twice charged

Lang took command of the Florida Brigade. The Florida Brigade served through the Gettysburg Campaign and twice charged Cemetery Ridge

Cemetery Ridge is a geographic feature in Gettysburg National Military Park, south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that figured prominently in the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1 to July 3, 1863. It formed a primary defensive position for the ...

at Gettysburg, including supporting Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the B ...

. It suffered heavy fire from Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery

Freeman McGilvery (October 17, 1823 – September 3, 1864) was a United States Army artillery officer during the American Civil War. He gained fame at the Battle of Gettysburg for taking the initiative to piece together a line of guns that gre ...

's line of artillery, and lost about 60% of its 700 plus soldiers when attacked on one flank by the 2nd Vermont Brigade

The 2nd Vermont Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War.

Composition and commanders

The brigade was composed of the 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th and 16th Vermont Infantry regiments, all nin ...

of Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard.

Perry then returned to command of the Florida Brigade, leading it in the Bristoe and Mine Run campaigns.

Western Theater

In early 1862, the Confederate government pulled General Bragg's small army from Pensacola following successive Confederate defeats in

In early 1862, the Confederate government pulled General Bragg's small army from Pensacola following successive Confederate defeats in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

at Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built early in 1862 by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River, which led to the heart of Tennessee, and thereby the Confederacy. The fort was named after Confederate general Da ...

and Fort Henry and the fall of New Orleans. It sent them to the Western Theater for the remainder of the war. Florida native Edmund Kirby Smith

General Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the Indi ...

fought with Bragg.

The 1st and 3rd Florida Infantry Regiments joined Bragg in Tennessee. Convention delegate W. G. M. Davis raised the 1st Florida Cavalry and joined General Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia seceded ...

in Tennessee. In December 1863, the 4th Florida Infantry was consolidated with the 1st Cavalry. Convention delegate Daniel D. McLean was a 2nd lieutenant in the 4th's Company H, and died in service. The 7th Florida Infantry

The 7th Florida Infantry Regiment was a Civil War regiment from Florida organized at Gainesville, in April, 1862. Its companies were recruited in the counties of Bradford, Hillsborough, Alachua, Manatee, and Marion.

During the war it served in R. ...

also fought with the Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating i ...

.

Battles in Florida

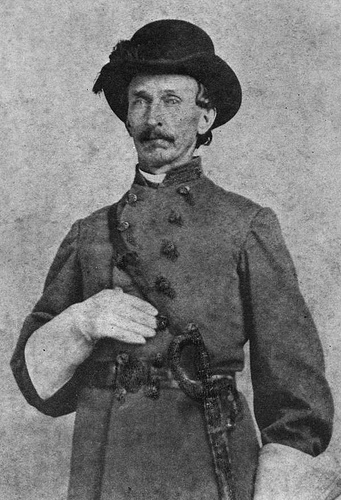

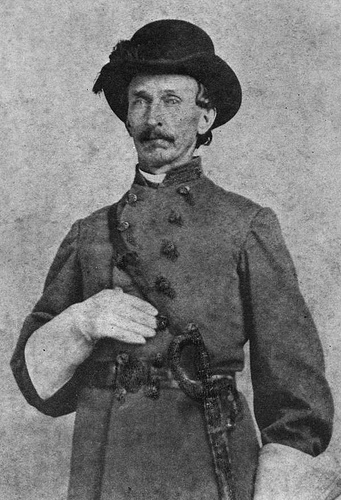

After Bragg's troops left for Tennessee, the only Confederate forces remaining in Florida at that time were a variety of independent companies, several infantry battalions, and the 2nd Florida Cavalry, commanded by J. J. Dickison. On May 20, Confederates ambushed a Union landing party in Crooked River.Tampa

The Union gunboat sailed up

The Union gunboat sailed up Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater in ...

to bombard Fort Brooke

Fort Brooke was a historical military post established at the mouth of the Hillsborough River in present-day Tampa, Florida in 1824. Its original purpose was to serve as a check on and trading post for the native Seminoles who had been confined ...

under the command of John William Pearson

John William Pearson (January 19, 1808 – September 30, 1864) was an American businessman and a Confederate Captain during the American Civil War. Pearson was a successful businessman who established a popular health resort in Orange Springs ...

on June 30, 1861. Representatives from both sides met under a flag of truce on a launch in the bay, where Pearson refused a Union demand that he unconditionally surrender. The ''Sagamore'' began bombarding the town that evening and the fort's defenders returned fire, opening the Battle of Tampa

The Battle of Tampa, also known as the "Yankee Outrage at Tampa", was a minor engagement of the American Civil War fought June 30 – July 1, 1862, between the United States Navy and a Confederate artillery company charged with "protecting" ...

. The steamship moved out of range of the fort's guns the next morning and resumed fire for several hours before withdrawing. The engagement was inconclusive, as neither side scored a direct hit and there were no casualties.

=St. Johns Bluff

= Jacksonville was occupied after theBattle of St. Johns Bluff

The Battle of St. John's Bluff was fought from October 1–3, 1862, between Union and Confederate forces in Duval County, Florida, during the American Civil War. The battle resulted in a significant Union victory, helping secure their control o ...

, a bluff designed to stop the movement of Federal ships up the St. Johns River, was won by John Milton Brannan

John Milton Brannan (July 1, 1819 – December 16, 1892) was a career United States Army artillery officer who served in the Mexican–American War and as a Union brigadier general of volunteers in the American Civil War, in command of the Departm ...

and about 1,500 infantry.

The flotilla arrived at the mouth of the St. John' s River on October 1, where Cdr. Charles Steedman' s gunboats—Paul Jones, Cimarron, Uncas, Patroon, Hale, and Water Witch—joined them. Brannan landed troops at Mayport Mills. The Bluff held off the Naval squadron until the troops were landed to come up behind it, the Confederates quietly abandoned the work.

In January 1863, there was a skirmish at Township Landing with the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. On March 9, 1863, 80 Confederates were driven off by 120 men of the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers near St. Augustine.

On 28 July 1863, ''Sagamore'' and attacked New Smyrna.

The flotilla arrived at the mouth of the St. John' s River on October 1, where Cdr. Charles Steedman' s gunboats—Paul Jones, Cimarron, Uncas, Patroon, Hale, and Water Witch—joined them. Brannan landed troops at Mayport Mills. The Bluff held off the Naval squadron until the troops were landed to come up behind it, the Confederates quietly abandoned the work.

In January 1863, there was a skirmish at Township Landing with the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. On March 9, 1863, 80 Confederates were driven off by 120 men of the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers near St. Augustine.

On 28 July 1863, ''Sagamore'' and attacked New Smyrna.

=Fort Brooke

= The

The Battle of Fort Brooke

The Battle of Fort Brooke was a minor engagement fought October 16–18, 1863 in and around Tampa, Florida during the American Civil War. The most important outcome of the action was the destruction of two Confederate blockade runners whic ...

in October 1863 was the second and largest skirmish in Tampa during the Civil War. On October 15, two Union Navy ships, and , bombarded Fort Brooke

Fort Brooke was a historical military post established at the mouth of the Hillsborough River in present-day Tampa, Florida in 1824. Its original purpose was to serve as a check on and trading post for the native Seminoles who had been confined ...

from positions in Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater in ...

out of the range of Confederate artillery. Under the cover of shelling that continued intermittently for three days, a detachment of Union forces landed in secret and marched several miles to where two blockade running ships owned by former Tampa mayor James McKay Sr.

James McKay Sr. (May 17, 1808 – November 11, 1876) was a cattleman, ship captain, and the sixth mayor of Tampa, Florida. McKay is memorialized with a bronze bust on the Tampa Riverwalk, along with other historical figures prominent in th ...

were hidden along the Hillsborough River. The ''Scottish Chief'', a steamship, and the sloop ''Kate Dale'' were burned at their moorings near present day Lowry Park. Their mission accomplished, Union troops made their way to their landing point but were intercepted near present day Ballast Point Park by a small force consisting of Confederate cavalry from Fort Brooke along with local militia. A brief but sharp skirmish erupted as the raiding party attempted to board their boats and row back to the ''Tahoma'', with the ship supporting the troops in the water by firing shells over their heads at the Confederates on shore. Most of the landing party successfully returned to the ship and both sides suffered about 20 casualties.

''Tahoma'' returned to Tampa Bay and again shelled Fort Brooke on Christmas Day 1863. The defenders prepared for another landing but none was forthcoming, and the ship steamed away at nightfall.

By May 1864, all regular Confederate troops had been withdrawn from Tampa to reinforce beleaguered forces in more active theaters of war. Union forces landed without opposition on May 5 and seized or destroyed all artillery pieces and other supplies left behind at Fort Brooke. They occupied the fort for about six weeks, but as the town of Tampa had been largely abandoned, they left in June, leaving the fort unoccupied for the duration of the war.

Final years

The force remaining in Florida were reinforced in 1864 by troops from neighboring Georgia. Andersonville Prison began in February 1864. Convention delegate John C. Pelot was its lead surgeon.=Olustee

=

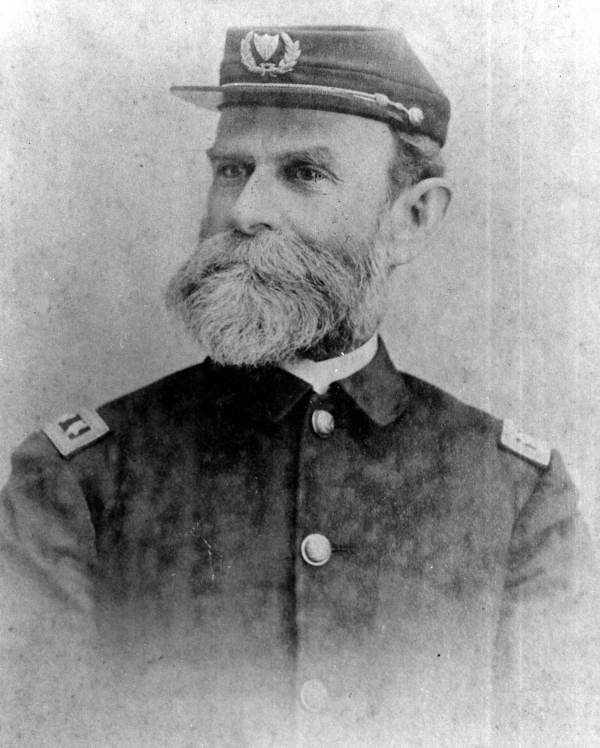

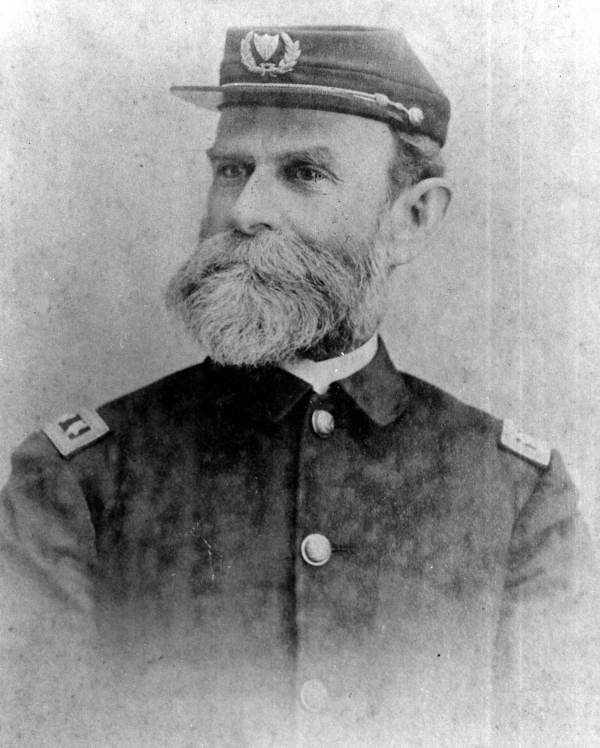

Quincy Gillmore

Quincy Adams Gillmore (February 28, 1825 – April 7, 1888) was an American civil engineer, author, and a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was noted for his actions in the Union victory at Fort Pulaski, where his mod ...

selected Brigadier General Truman Seymour

Truman Seymour (September 24, 1824 – October 30, 1891) was a career soldier and an accomplished painter. He served in the Union Army during the American Civil War, rising to the rank of major general. He was present at the Battle of Fort S ...

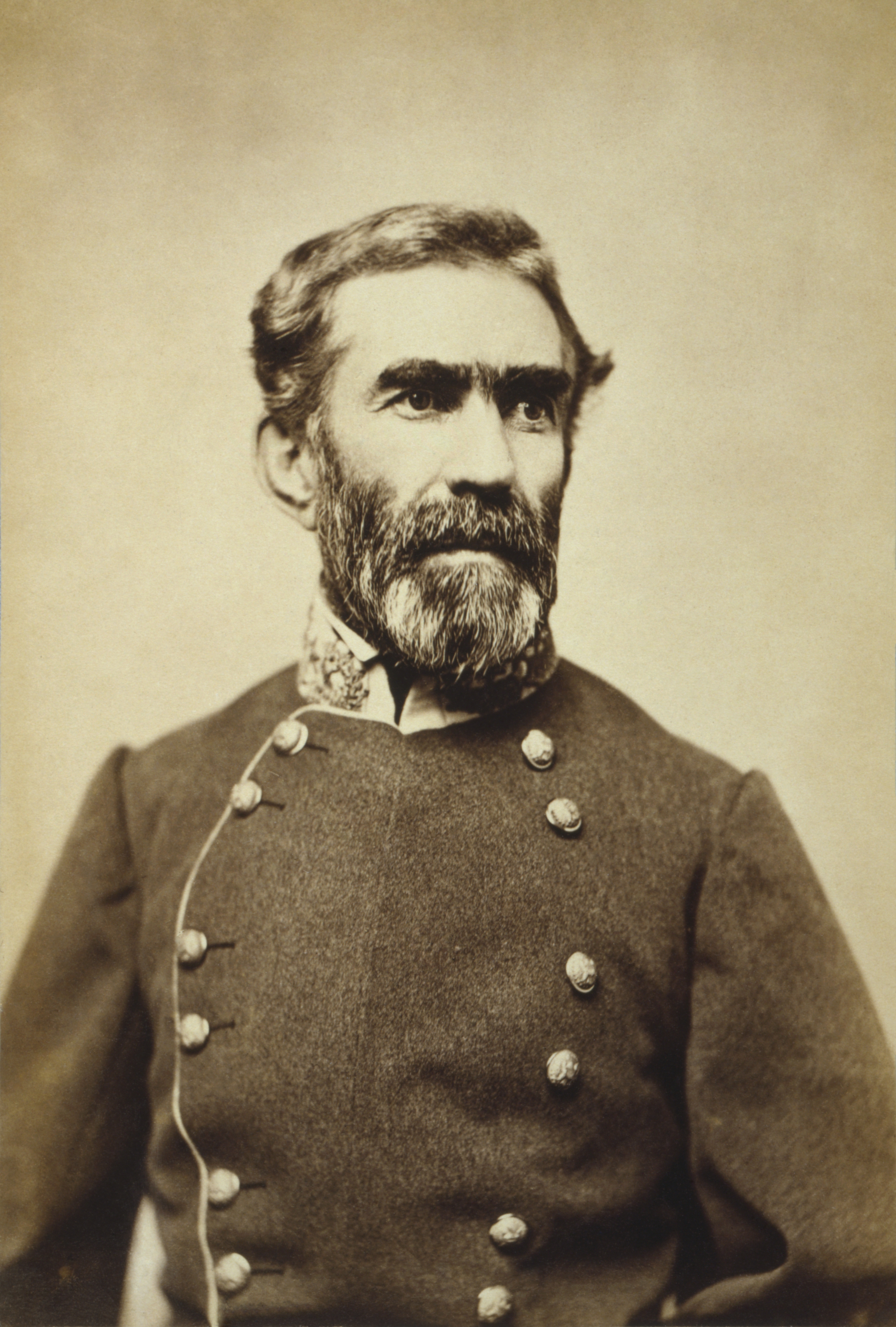

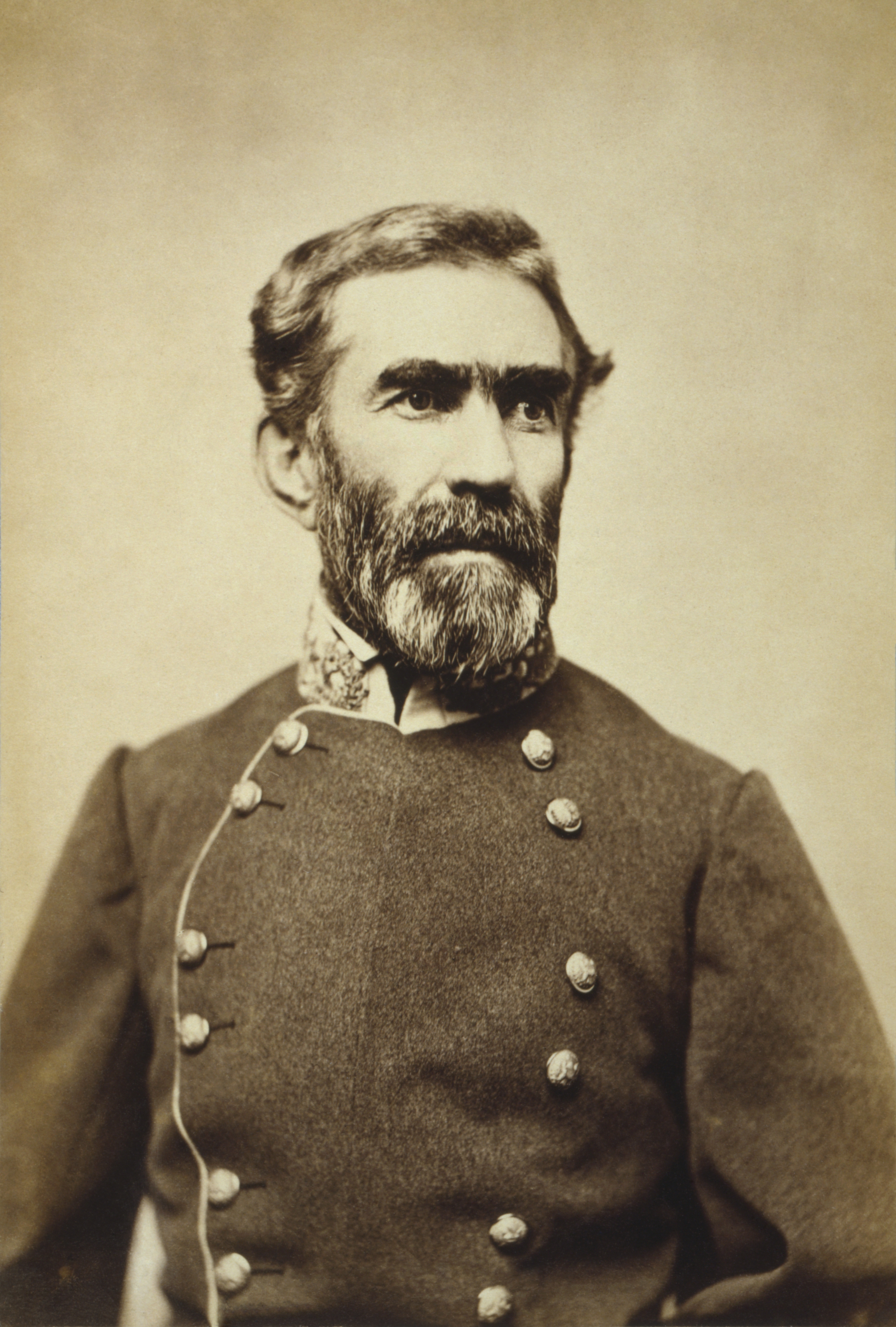

for an invasion of Florida, landing in Jacksonville on February 7. Joseph Finegan

Joseph Finegan, sometimes Finnegan (November 17, 1814 – October 29, 1885), was an American businessman and brigadier general for the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. From 1862 to 1864 he commanded Confederate forces oper ...

skirmished with Union forces at Barber's Ford and Lake City on February 10 and 11. The only major engagement in Florida was at Olustee near Lake City. Union forces under Seymour were repulsed by Finegan's Florida and Georgia troops and retreated to their fortifications around Jacksonville. Brevard's Battalion fought with Finegan's Brigade at Olustee.

Seymour's relatively high losses caused

Seymour's relatively high losses caused Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ra ...

lawmakers and citizens to question the necessity of any further Union actions in militarily insignificant Florida. Many of the Federal troops were withdrawn and sent elsewhere. Throughout the balance of 1864 and into the following spring, the 2nd Florida Cavalry repeatedly thwarted Federal raiding parties into the Confederate-held northern and central portions of the state.

The Skirmish at Cedar Creek soon followed. Perry had suffered wounds, and the three regiments of Perry's Brigade were consolidated into Finegan's Brigade, which included the 9th

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra and ...

, 10th

10 (ten) is the even natural number following 9 and preceding 11. Ten is the base of the decimal numeral system, by far the most common system of denoting numbers in both spoken and written language. It is the first double-digit number. The rea ...

and 11th Infantries. Convention delegate Green H. Hunter was captain of the 9th's Company E. There was a skirmish at McGirt's Creek on March 1, 1864.

In March 1864, James McKay wrote the state to say he was unable to secure cattle as his blockade runners had been destroyed during the Battle of Fort Brooke.. C. J. Munnerlyn organized the 1st Florida Special Cavalry Battalion

The 1st Florida Special Cavalry Battalion, nicknamed Cow Cavalry, was a Confederate States Army cavalry unit from Florida during the American Civil War. Commanded by Charles James Munnerlyn; it was organized to protect herds of cattle from Union ...

or "Cow Cavalry" in April made up of Florida crackers, including John T. Lesley

John Thomas Lesley (May 12, 1835 – July 13, 1913) was a cattleman and pioneer in Tampa, Florida. He fought in the Third Seminole War and was a captain in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Lesley formed his own volunteer company t ...

, Francis A. Hendry and W. B. Henderson

William Benton Henderson (September 17, 1839 – May 7, 1909) was a cattleman, merchant, and prominent figure in the history of Tampa, Florida. He is the namesake of Henderson Boulevard and Henderson Avenue as well as the former W. B. Henders ...

.

=Horse Landing

= Convention delegate James O. Devall owned ''General Sumpter'', the first steamboat in Palatka, which was captured by in March 1864. Palatka was occupied, and there were two picket attacks in late March. Union troops utilized Sunny Point, and St. Mark's was used as a barracks.

The first mine casualty of the war was at Jacksonville on April 1, 1864. ''General Hunter'' was sunk on April 16, close to where ''Maple Leaf'' was sunk.

On May 19, there was a skirmish with the 17th Connecticut in Welaka, and a skirmish in Saunders. On May 21, spy Lola Sanchez got wind of a Union raid, and the Columbine was captured by Dickison's forces at the "Battle of Horse Landing".

Convention delegate James O. Devall owned ''General Sumpter'', the first steamboat in Palatka, which was captured by in March 1864. Palatka was occupied, and there were two picket attacks in late March. Union troops utilized Sunny Point, and St. Mark's was used as a barracks.

The first mine casualty of the war was at Jacksonville on April 1, 1864. ''General Hunter'' was sunk on April 16, close to where ''Maple Leaf'' was sunk.

On May 19, there was a skirmish with the 17th Connecticut in Welaka, and a skirmish in Saunders. On May 21, spy Lola Sanchez got wind of a Union raid, and the Columbine was captured by Dickison's forces at the "Battle of Horse Landing".

New York's 14th cavalry lost in a skirmish at Cow Ford Creek on April 2. The

New York's 14th cavalry lost in a skirmish at Cow Ford Creek on April 2. The 7th United States Colored Infantry

The 7th United States Colored Infantry was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was composed of African American enlisted men commanded by white officers and was authorized by the Bureau of ...

fought in a skirmish at Camp Finnegan on May 25, and on the same day there was a skirmish at Jackson's Bridge near Pensacola.

Camp Milton was captured on June 2, and Baldwin raided on July 23. The Union would raid Florida's cattle. A skirmish at Trout Creek occurred on July 15. On July 24, William Birney

William Birney (May 28, 1819 – August 14, 1907) was an American professor, Union Army general during the American Civil War, attorney and author. An ardent Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, he was noted for encouraging thousands ...

was attacked by G. W. Scott and the 2nd Florida Cavalry at the South Fork of Black Creek.

The Florida Brigade took part in the Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

. Perry was wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Arm ...

. The Brigade was then at the Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S ...

. The 11th was then reorganized with Brevard as commander.

The Brigade then fought at the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

. At Weldon Railroad Weldon may refer to:

Places

In Canada:

* Weldon, Saskatchewan

In England:

* Weldon, Northamptonshire

* Weldon, Northumberland

In the United States:

* Weldon, Arkansas

* Weldon, California

* Weldon, Illinois

* Weldon, Iowa

* Weldon, North Caroli ...

, Brevard learned of the death of his brother, Mays Brevard. The Brigade also fought at the Battle of Ream's Station and the Battle of Globe Tavern

The Battle of Globe Tavern, also known as the Second Battle of the Weldon Railroad, fought August 18–21, 1864, south of Petersburg, Virginia, was the second attempt of the Union Army to sever the Weldon Railroad during the siege of Petersburg ...

. Lamar was shot off his horse by a Yankee sniper at Petersburg on August 30.

=Gainesville

= Confederates occupied Gainesville after the

Confederates occupied Gainesville after the Battle of Gainesville

The Battle of Gainesville was an American Civil War engagement fought on August 17, 1864, when a Confederate force defeated Union detachments from Jacksonville, Florida. The result of the battle was the Confederate occupation of Gainesville for ...

. On August 15, 1864, Col. Andrew L. Harris

Andrew Lintner Harris (also known as The Farmer–Statesman) (November 17, 1835 – September 13, 1915) was one of the heroes of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War and served as the 44th governor of Ohio.

Biography

Har ...

of the 75th Ohio Mounted infantry left Baldwin with 173 officers and men from the Seventy-Fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The Union troops on the way destroyed a picket post on the New River. At Starke, the Union troops were joined by the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry and some Florida Unionists. On August 17, 1864, Dickison was told that members of the Union Army had arrived at Starke and that they had burned Confederate train cars. Dickison proceeded to Gainesville, and attacked the Union troops from the rear.

=Marianna

= On September 27, 1864, GeneralAlexander Asboth

Alexander "Sandor" Asboth ( Hungarian: Asbóth Sándor, December 18, 1811 – January 21, 1868) was a Hungarian military leader best known for his victories as a Union general during the American Civil War. He also served as United States Ambassa ...

led a raid in Marianna, the home of Governor Milton and an important supply depot, and the Battle of Marianna ensued, with the Union stunned at first but achieving a victory. Convention delegate Adam McNealy served in the Marianna Home Guard. Asboth was wounded, as was dentist Thaddeus Hentz, not far from his mother's grave, the famed novelist Caroline Lee Hentz

Caroline Lee Whiting Hentz (June 1, 1800, Lancaster, Massachusetts – February 11, 1856, Marianna, Florida) was an American novelist and author, most noted for her defenses of slavery and opposition to the abolitionist movement. Her widely read ' ...

, who wrote ''The Planter's Northern Bride

''The Planter's Northern Bride'' is an 1854 novel written by Caroline Lee Hentz, in response to the publication of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1852.

Overview

Unlike other examples of anti-Tom literature (aka "plantation ...

'', a pro-slavery rebuttal to Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

's popular anti-slavery book, ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U. ...

''. The next day, Asboth's forces again ran into a battle in Vernon.

On October 18 at Pierce's Point south of Milton, Union troops were attacked by Confederates. In December 1864, there were skirmishes in Mitchell's Creek and Pine Barren Ford with the 82nd Colored Infantry.

=Braddock's Farm

= Near Crescent City, there was the Battle of Braddock's Farm. Dickison caught the troops of the 17th Connecticut Infantry when they had just finished a raid, and when they charged, he shot their commander Albert Wilcoxson off his horse. When Dickison asked Wilcoxson why he charged, he responded, "Don't blame yourself, you are only doing your duty as a soldier. I alone am to blame." In Cedar Key, there was the Battle of Station Four. TheBattle of Fort Myers

The Battle of Fort Myers was fought on February 20, 1865, in Lee County, Florida during the last months of the American Civil War. This small engagement is known as the "southernmost land battle of the Civil War."

Background

Fort Myers had been ...

is known as the "southernmost land battle of the Civil War." Confederate Maj. William Footman led 275 men of the "Cow Cavalry" to the fort under a flag of truce to demand surrender. The fort's commander, Capt. James Doyle, refused, and the battle began.

=Natural Bridge

= In March 1865

In March 1865 Battle of Natural Bridge

The Battle of Natural Bridge was fought during the American Civil War in what is now Woodville, Florida near Tallahassee on March 6, 1865. A small group of Confederate troops and volunteers, which included teenagers from the nearby Florida Mil ...

, a small band of Confederate troops and volunteers, mostly composed of teenagers from the nearby Florida Military and Collegiate Institute that would later become Florida State University

Florida State University (FSU) is a public research university in Tallahassee, Florida. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida. Founded in 1851, it is located on the oldest continuous site of higher education in the st ...

, and the elderly, protected by breastworks, prevented a detachment of United States Colored Troops from crossing the Natural Bridge on the St. Marks River.

Brevard took command of the Florida Brigade on March 22.

On April 1, Governor Milton committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

rather than submit to Union occupation. In a final statement to the state legislature, he said Yankees "have developed a character so odious that death would be preferable to reunion with them." He was replaced by convention delegate Abraham K. Allison.

Brevard was captured at the Battle of Sailor's Creek