Florence Bravo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Florence Bravo (née Campbell; 5 September 1845 – 17 September 1878) was a British heiress and widow who was linked to the unsolved murder of her second husband, Charles Bravo. On 21 April 1876, after three days of agonising illness, Charles died of

"1. Florence Bravo"

in "Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley". ''BBC Radio 4.'' as well as publications in Europe, Australia, and the United States. Previously known as Florence Ricardo, she had inherited £40,000 after her first husband, an alcoholic, drank himself to death. Florence herself lived for only two years after Charles Bravo's death, and died at the age of 33.

On 21 September 1864, at the age of nineteen, Florence married Alexander Ricardo at Buscot Park, following a brief courtship. The newspapers hailed their marriage as "the union of two great families of Europe" – the Campbells, who had been Scottish landowners, and the Ricardos, descendants of a prominent

On 21 September 1864, at the age of nineteen, Florence married Alexander Ricardo at Buscot Park, following a brief courtship. The newspapers hailed their marriage as "the union of two great families of Europe" – the Campbells, who had been Scottish landowners, and the Ricardos, descendants of a prominent

Instead, Ann Campbell advised Florence and Alexander to visit the

Instead, Ann Campbell advised Florence and Alexander to visit the

In the years that followed, Florence Ricardo and Dr Gully had an affair which they tried to keep secret, while maintaining the outward appearance of propriety. Her parents disapproved of her "infatuation" with Dr Gully and insisted that she cut off all ties with him. Florence refused and became estranged from them, but because of the inheritance from Alexander Ricardo, she was now independently wealthy. Florence later admitted that she and Gully had had "conversations about marriage". Although Gully was technically married, he had been separated from his wife, who was 17 years his senior, for thirty years. He promised to marry Florence after his wife died, to avoid scandal, and planned to move with her abroad.

Florence moved to

In the years that followed, Florence Ricardo and Dr Gully had an affair which they tried to keep secret, while maintaining the outward appearance of propriety. Her parents disapproved of her "infatuation" with Dr Gully and insisted that she cut off all ties with him. Florence refused and became estranged from them, but because of the inheritance from Alexander Ricardo, she was now independently wealthy. Florence later admitted that she and Gully had had "conversations about marriage". Although Gully was technically married, he had been separated from his wife, who was 17 years his senior, for thirty years. He promised to marry Florence after his wife died, to avoid scandal, and planned to move with her abroad.

Florence moved to

Charles died less than five months after marrying Florence. On 18 April 1876, Florence and Charles went into town together, briefly quarrelling when their carriage passed Orwell Lodge. They stopped at the bank and at the jewellers on

Charles died less than five months after marrying Florence. On 18 April 1876, Florence and Charles went into town together, briefly quarrelling when their carriage passed Orwell Lodge. They stopped at the bank and at the jewellers on

Leading up to his death on 21 April 1876, Charles Bravo was seen by six medical professionals, including one of the most highly regarded physicians in England. The first two doctors were Dr Joseph Moore of Balham, who arrived first, and Dr George Harrison of Streatham, who arrived after midnight. Moore and Harrison conferred and agreed that it was a serious case of poisoning, and that Charles would die. They asked Florence, Mrs Cox, and Mary Ann if they had any idea what could have caused Charles's symptoms. Florence suggested that Charles had had a heart attack after the horse ride, and also mentioned that he was "prone to fainting fits" and that he had been "worried about stocks and shares". Dr Harrison told Mrs Cox that she was wrong when she suggested that Charles had ingested chloroform, and that the symptoms had likely been caused by

Leading up to his death on 21 April 1876, Charles Bravo was seen by six medical professionals, including one of the most highly regarded physicians in England. The first two doctors were Dr Joseph Moore of Balham, who arrived first, and Dr George Harrison of Streatham, who arrived after midnight. Moore and Harrison conferred and agreed that it was a serious case of poisoning, and that Charles would die. They asked Florence, Mrs Cox, and Mary Ann if they had any idea what could have caused Charles's symptoms. Florence suggested that Charles had had a heart attack after the horse ride, and also mentioned that he was "prone to fainting fits" and that he had been "worried about stocks and shares". Dr Harrison told Mrs Cox that she was wrong when she suggested that Charles had ingested chloroform, and that the symptoms had likely been caused by

The second coroner's inquest took place from 11 July through 11 August 1876, in the Bedford Hotel in Balham. It was attended by the Attorney General himself, with "eminent members of the Bar" holding briefs, and was covered extensively by members of the press. Over an unprecedented 23 days of testimony, members of the public crowded the streets to try to catch a glimpse of the witnesses giving evidence and find out the latest news each day.

Sir William Gull, "the most celebrated physician in England",appeared on the fourth day of the inquest. Gull stated that Charles "did not behave like a man who thought he was being murdered" and that "he had showed no surprise" that he was dying of poison. Gull believed that Charles had swallowed antimony intentionally but lost his nerve, and had asked for hot water to flush out his system, and remained convinced of Florence's complete innocence.

Interest in the case reached its peak when Florence testified for three days starting 3 August 1876. According author James Ruddick, "For Florence Bravo, the Coroner's inquest was the worst experience of her life." Rather than focusing on the circumstances leading up to Charles Bravo's death, his family's lawyers became fixated with proving that Florence had continued her affair with Dr Gully during their marriage, and subjected Florence, Dr Gully, and other witnesses to repeated questions about her past "sexual conduct". The lurid details of her "criminal intimacy" with Dr Gully before marrying Charles were covered in depth, in national newspapers such as ''

The second coroner's inquest took place from 11 July through 11 August 1876, in the Bedford Hotel in Balham. It was attended by the Attorney General himself, with "eminent members of the Bar" holding briefs, and was covered extensively by members of the press. Over an unprecedented 23 days of testimony, members of the public crowded the streets to try to catch a glimpse of the witnesses giving evidence and find out the latest news each day.

Sir William Gull, "the most celebrated physician in England",appeared on the fourth day of the inquest. Gull stated that Charles "did not behave like a man who thought he was being murdered" and that "he had showed no surprise" that he was dying of poison. Gull believed that Charles had swallowed antimony intentionally but lost his nerve, and had asked for hot water to flush out his system, and remained convinced of Florence's complete innocence.

Interest in the case reached its peak when Florence testified for three days starting 3 August 1876. According author James Ruddick, "For Florence Bravo, the Coroner's inquest was the worst experience of her life." Rather than focusing on the circumstances leading up to Charles Bravo's death, his family's lawyers became fixated with proving that Florence had continued her affair with Dr Gully during their marriage, and subjected Florence, Dr Gully, and other witnesses to repeated questions about her past "sexual conduct". The lurid details of her "criminal intimacy" with Dr Gully before marrying Charles were covered in depth, in national newspapers such as ''

Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley: Florence Bravo

(BBC Sounds)

Florence Bravo (née Campbell)

(National Portrait Gallery) {{authority control 1845 births 1878 deaths 19th-century British women

antimony poisoning

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient times ...

. Although there was widespread innuendo in the media about Florence's role in “The Balham Mystery”, following the second inquest into his death, no one was indicted, and the case never reached the courts due to lack of evidence. During the Coroner's inquest, the lurid details of Florence's past affair with Dr James Gully, a married man 37 years older, became a topic of intense fascination, covered by newspapers ranging from ''The Times'' and ''The Daily Telegraph'' to ''The Illustrated Police News'',Worsley, Lucy (2022)"1. Florence Bravo"

in "Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley". ''BBC Radio 4.'' as well as publications in Europe, Australia, and the United States. Previously known as Florence Ricardo, she had inherited £40,000 after her first husband, an alcoholic, drank himself to death. Florence herself lived for only two years after Charles Bravo's death, and died at the age of 33.

Early life and family

Born in 1845 inNew South Wales, Australia

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Florence Campbell was the eldest daughter of Robert and Ann Campbell (née Orr). Robert Campbell ("Tertius") was a land speculator and merchant who made a considerable fortune buying and selling gold. In 1852, the Campbells moved with their eight children, a governess, and three servants to England. In 1859, Robert purchased Buscot Park

Buscot Park is a country house at Buscot near the town of Faringdon in Oxfordshire within the historic boundaries of Berkshire. It is a Grade II* listed building.

It was built in an austere neoclassical style between 1780 and 1783 for Edward ...

, a large estate near Faringdon

Faringdon is a historic market town in the Vale of White Horse, Oxfordshire, England, south-west of Oxford, north-west of Wantage and east-north-east of Swindon. It extends to the River Thames in the north; the highest ground is on the Rid ...

and historically in Berkshire; he also had homes in Belgravia, London, and Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

. Florence took elocution lessons, learned French and some German, and did needlework. She was very fond of animals, especially horses.

As a teenager, she traveled with her family to Canada, where she met Alexander Ricardo, a young British military officer stationed at the Royal Military College. He was the grandnephew of economist David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British Political economy, political economist. He was one of the most influential of the Classical economics, classical economists along with Thomas Robert Malthus, Thomas Malthus, Ad ...

; the only son of International Telegraph Company

The Electric Telegraph Company (ETC) was a British telegraph company founded in 1846 by William Fothergill Cooke and John Ricardo. It was the world's first public telegraph company. The equipment used was the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, ...

founder John L. Ricardo, who had served as member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for Stoke-on-Trent; and the nephew of James Duff, the Fifth Earl of Fife, through his mother, Lady Catherine.

First marriage

On 21 September 1864, at the age of nineteen, Florence married Alexander Ricardo at Buscot Park, following a brief courtship. The newspapers hailed their marriage as "the union of two great families of Europe" – the Campbells, who had been Scottish landowners, and the Ricardos, descendants of a prominent

On 21 September 1864, at the age of nineteen, Florence married Alexander Ricardo at Buscot Park, following a brief courtship. The newspapers hailed their marriage as "the union of two great families of Europe" – the Campbells, who had been Scottish landowners, and the Ricardos, descendants of a prominent Dutch Jewish

The history of the Jews in the Netherlands began largely in the 16th century when they began to settle in Amsterdam and other cities. It has continued to the present. During the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany in May 1940, the J ...

family. Their lavish wedding was officiated by the local vicar, as well as Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public speakers of his day.Natural Hi ...

, the Bishop of Oxford

The Bishop of Oxford is the diocesan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Oxford in the Province of Canterbury; his seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. The current bishop is Steven Croft, following the confirmation of his electio ...

. Florence received a generous marriage settlement of £1,000 a year from her father. After a honeymoon in the Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

, Florence and Alexander returned to England and lived in the West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Gloucesters ...

.

Problems

Seven months into their marriage, Florence informed her father that she and Alexander were having problems. They were at odds over Alexander's military career with theGrenadier Guards

"Shamed be whoever thinks ill of it."

, colors =

, colors_label =

, march = Slow: " Scipio"

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment ...

; she wanted to have a large family, and feared that he would be sent to war and killed in conflict. Florence finally prevailed, and in the spring of 1868, Alexander received an honourable discharge and left the service with the rank of captain. The couple moved to Gatcombe Park

Gatcombe Park is the country residence of Anne, Princess Royal, between the villages of Minchinhampton (to which it belongs) and Avening in Gloucestershire, England. Built in the late 18th century to the designs of George Basevi, it is a ...

in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

, where they took part in aristocratic pursuits such as hunting, fishing, and horse-riding, and regularly hosted parties. Alexander tried to get involved in their families' businesses, but quickly lost interest and grew depressed.

Florence soon found out about Alexander's infidelity

Infidelity (synonyms include cheating, straying, adultery, being unfaithful, two-timing, or having an affair) is a violation of a couple's emotional and/or sexual exclusivity that commonly results in feelings of anger, sexual jealousy, and riva ...

. He had a mistress who lived in the West End of London

The West End of London (commonly referred to as the West End) is a district of Central London, west of the City of London and north of the River Thames, in which many of the city's major tourist attractions, shops, businesses, government buil ...

, and had been seen with women in hotels in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

and in the West Country. When confronted, Alexander eventually confessed, but persisted with his extramarital affairs. He became an alcoholic, and his health started to deteriorate. When drunk, he was verbally abusive and at times violent toward Florence. Florence herself became ill and was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. In late 1869, she wrote to her mother that she wanted a separation, but her father regarded the failure of their marriage as "morally offensive"; both parents were determined to avoid the scandal that would result.

Treatment by Dr Gully

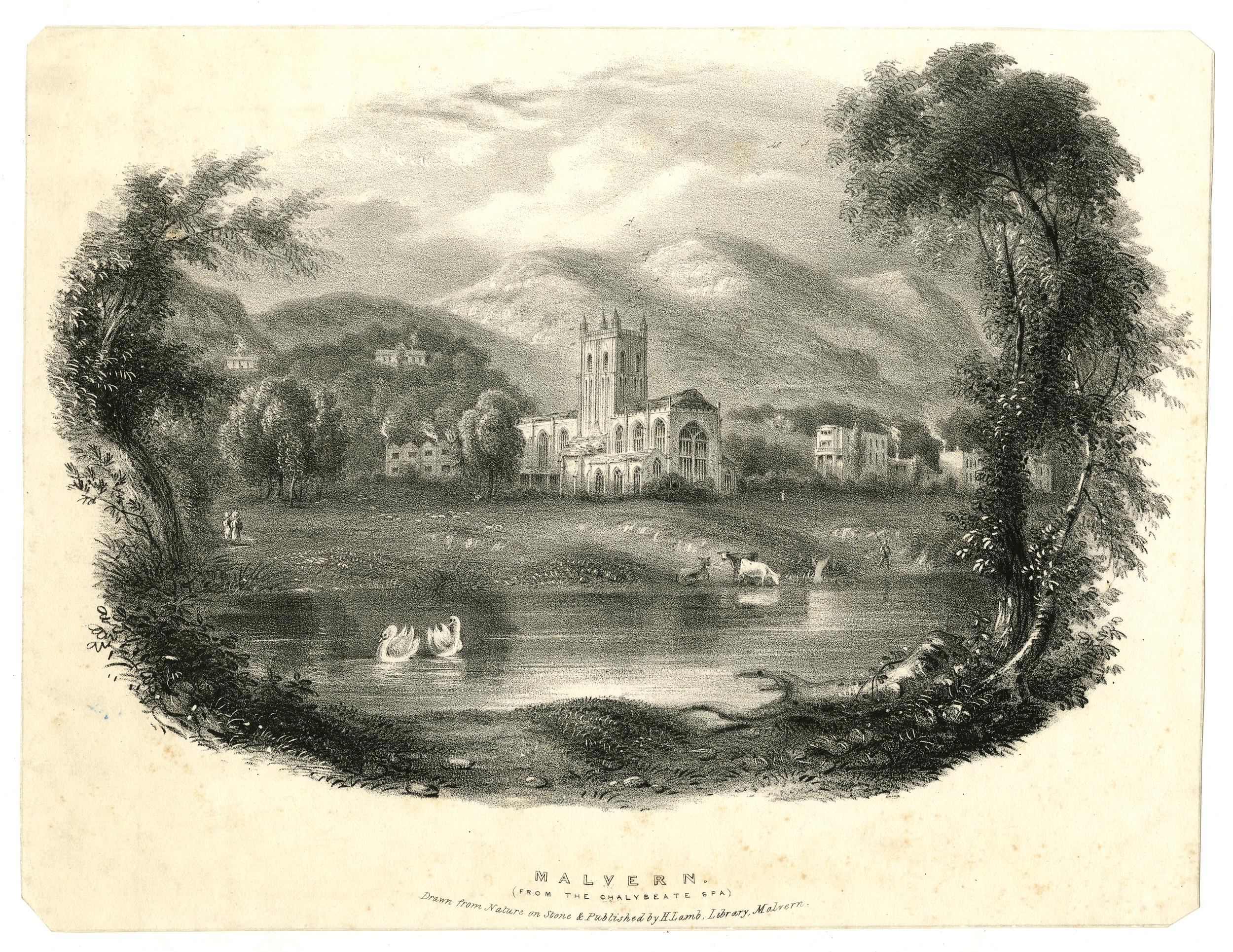

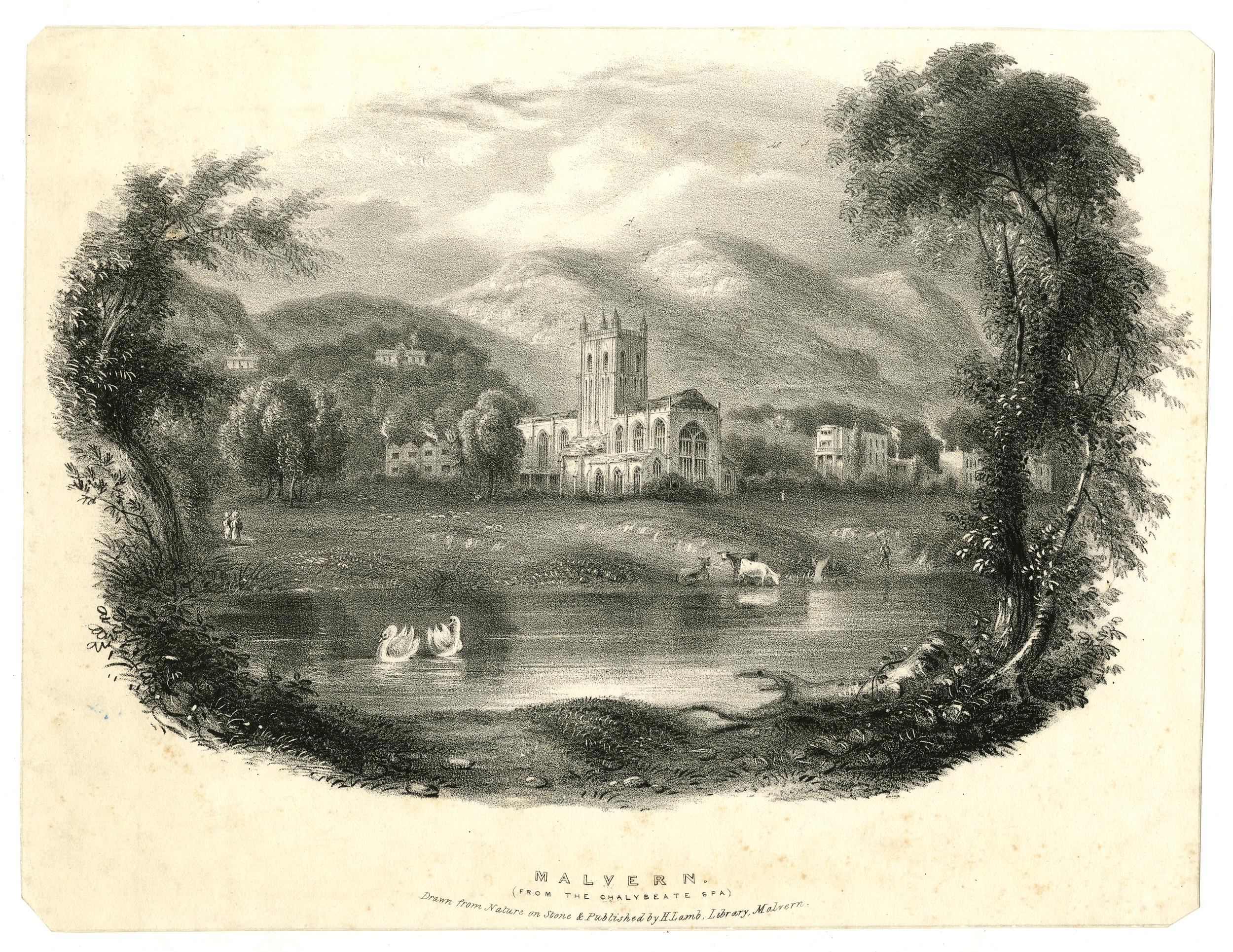

Instead, Ann Campbell advised Florence and Alexander to visit the

Instead, Ann Campbell advised Florence and Alexander to visit the spa town

A spa town is a resort town based on a mineral spa (a developed mineral spring). Patrons visit spas to "take the waters" for their purported health benefits.

Thomas Guidott set up a medical practice in the English town of Bath in 1668. H ...

of Malvern

Malvern or Malverne may refer to:

Places Australia

* Malvern, South Australia, a suburb of Adelaide

* Malvern, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne

* City of Malvern, a former local government area near Melbourne

* Electoral district of Malvern, an e ...

, where their family friend Dr James Gully, a homeopathic hydrotherapist

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and Physical therapy, physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and tr ...

, had been successfully treating Victorian celebrity patients including Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

, Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

, Alfred Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

, and Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

. In 1870, Florence Ricardo became the patient of 62-year-old Dr Gully, who had once treated her for a throat infection when she was twelve. To the alarm of her parents, Gully recommended that Florence separate from her husband for the sake of her own health and well-being. Florence went ahead with the legal separation from Alexander Ricardo, with help from Gully, despite her father's threat to cut her off financially.

Death of Alexander Ricardo

Alexander made a final attempt to reconcile with Florence before the separation papers were finalised in March 1871, and decided to go abroad after she refused. Several weeks later, on 20 April 1871, Florence received a telegram from London saying that Captain Alexander Ricardo had been found dead inCologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, in lodgings he shared with a "female companion". The cause of death was haematemesis

Hematemesis is the vomiting of blood. It is always an important sign. It can be confused with hemoptysis (coughing up blood) or epistaxis (nosebleed), which are more common. The source is generally the upper gastrointestinal tract, typically abo ...

, triggered by a final alcohol binge. Because Alexander had neglected to change his will, Florence inherited a fortune of £40,000.

Affair with doctor

In the years that followed, Florence Ricardo and Dr Gully had an affair which they tried to keep secret, while maintaining the outward appearance of propriety. Her parents disapproved of her "infatuation" with Dr Gully and insisted that she cut off all ties with him. Florence refused and became estranged from them, but because of the inheritance from Alexander Ricardo, she was now independently wealthy. Florence later admitted that she and Gully had had "conversations about marriage". Although Gully was technically married, he had been separated from his wife, who was 17 years his senior, for thirty years. He promised to marry Florence after his wife died, to avoid scandal, and planned to move with her abroad.

Florence moved to

In the years that followed, Florence Ricardo and Dr Gully had an affair which they tried to keep secret, while maintaining the outward appearance of propriety. Her parents disapproved of her "infatuation" with Dr Gully and insisted that she cut off all ties with him. Florence refused and became estranged from them, but because of the inheritance from Alexander Ricardo, she was now independently wealthy. Florence later admitted that she and Gully had had "conversations about marriage". Although Gully was technically married, he had been separated from his wife, who was 17 years his senior, for thirty years. He promised to marry Florence after his wife died, to avoid scandal, and planned to move with her abroad.

Florence moved to south London

South London is the southern part of London, England, south of the River Thames. The region consists of the Districts of England, boroughs, in whole or in part, of London Borough of Bexley, Bexley, London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, London Borou ...

, and leased a large mansion called the Priory in Balham

Balham () is an area in south London, England, mostly within the London Borough of Wandsworth with small parts within the neighbouring London Borough of Lambeth. The area has been settled since Saxon times and appears in the Domesday Book as B ...

, where she could keep two horses and a garden. Dr Gully retired and leased a house that was a five-minute walk away, called Orwell Lodge. According to their servants, they frequently visited each other, went shopping, and went riding, but never spent the night together. Author James Ruddick states, however, that in May 1872, their relationship was exposed when Florence was invited to stay at the family home of her solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

, Henry Brookes, in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

. Mr and Mrs Brookes returned home from a walk to pick up an umbrella, when they discovered Florence and Dr Gully having sex in their drawing room. A heated exchanged ensued, overheard by the servants, and their relationship quickly became the subject of widespread gossip. Gully instructed his solicitor to sue Mrs Brookes for slander

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, but soon withdrew the instruction. The social consequences were devastating to Florence: two servants threatened to quit, some grocers refused to serve her staff, and the invitations she sent out for afternoon tea and dinner were returned without explanation. Within a week, the news had reached her parents in Buscot Park. According to Alison Harris, a descendant of Florence's eldest brother William, Robert Campbell was "incensed and outraged" but also "broken" by the scandal. Florence's telegrams to her parents and her letters to her sister Edith went unanswered.

Abortion

In 1873, Florence traveled with Dr Gully toBad Kissingen

Bad Kissingen is a German spa town in the Bavarian region of Lower Franconia and seat of the district Bad Kissingen. Situated to the south of the Rhön Mountains on the Franconian Saale river, it is one of the health resorts, which be ...

, a spa town in rural Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. Later, she discovered she was pregnant. Fearing further scandal, she allowed Dr Gully to perform an abortion, which went badly. Florence became seriously ill, and later stated that Jane Cox, her "lady's companion", had saved her life by attending to her around the clock for six days and six nights. The ordeal effectively ended her affair with Gully. Florence refused to see him for two weeks, ended their physical relationship, and started to distance herself from him. Weary of social ostracism

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and longing for reconciliation with her parents, Florence started to seek a way out of the relationship.

Friendship with Jane Cox

When she was moving into the Priory, Florence had decided to hire Jane Cannon Cox to oversee day-to-day management of the household, including her large staff. Mrs Cox was a widow who had lived inJamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

and returned to England with her three young sons after her husband died. Florence said she was "very impressed by her, particularly her kindness and her excellent manners." According to author James Ruddick:Neighbours in Balham would later recall the sight of Florence and Mrs Cox travelling together in their open-top carriage, and comment on the attraction of opposites: Florence, the beautiful young widow, with her jewellery and flowing hair; Mrs Cox, the small, shy woman, draped in black, with the hardness and the sheen of a strange insect.By all accounts, Florence and Jane grew very close. During this period when Florence was cut off from her family – and from society – Jane Cox became a maternal figure and confidante. Florence later stated, "I called her Janie and she called me Florrie. At one time she was my only friend."

Second marriage

In 1874, Jane Cox engineered a series of "accidental" meetings between Florence Ricardo and Charles Bravo inKensington, London

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensington Gar ...

, where he lived with his parents, and in Brighton. Charles Delaunay Turner Bravo was the stepson of Joseph Bravo, a business associate of Jane's late husband, and the same age as Florence. Educated at King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

and Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Charles had been admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

in 1870. His friendship with Florence quickly blossomed, and although she joked to her mother that his letters were "cold and undemonstrative" and that he wrote "tersely, as all barristers do", he wrote to her regularly and not without affection.

In October 1875, Charles proposed marriage. For Florence, the prospect of marrying Charles offered the chance to restore her respectability in society. She wrote a letter to Dr Gully from Brighton that their relationship had to end, because she wanted to reconcile with her family. Gully went to Brighton, where they met in a hotel dining room, and Florence admitted that she was expecting a marriage proposal from Charles Bravo. In November 1875, she told Charles about her past affair with Dr Gully, knowing that she risked rejection. According to Florence, after some thought, Charles said she "had acted nobly and generously in telling him" and that her confession made him "more certain" that it was unlikely she would "err" again. The following day, Charles confessed to Florence that he had also had an affair for four years with a mistress in Maidenhead

Maidenhead is a market town in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in the county of Berkshire, England, on the southwestern bank of the River Thames. It had an estimated population of 70,374 and forms part of the border with southern Bu ...

, who had a daughter by him. They agreed not to mention their past affairs to each other ever again.

On 7 December 1875, Florence and Charles Bravo were married at All Saints Church

All Saints Church, or All Saints' Church or variations on the name may refer to:

Albania

*All Saints' Church, Himarë

Australia

* All Saints Church, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory

* All Saints Anglican Church, Henley Brook, Western Aust ...

in Kensington. Charles's main motivation for marrying Florence, despite her chequered past and against the wishes of his mother, was financial. Prior to the wedding, Florence decided to retain control over her fortune rather than have it transfer to her new husband – a legal option that had become available since Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

had passed the Married Women's Property Act of 1870. Upon finding out, Charles threatened to call the wedding off, saying to Florence's solicitor Brookes, "Damn your congratulations! I've come about the money." He urged Robert Campbell to intervene, writing in a letter: "I cannot contemplate a marriage that does not make me master in my own house. I cannot sit upon a chair or eat from a table which does not belong to me." Florence was so upset by his behaviour, she sought advice from Dr Gully, who "advised her not to squabble about the furniture", and wished her happiness. Finally, she agreed to a compromise: Florence would allow Charles to take over the lease to the Priory, as well as all furnishings, and put him in her will, while she retained control of her money.

By all accounts, during the first month of their marriage, they both seemed genuinely happy. After a brief honeymoon in Brighton, they returned to London. In letters to their parents, they described going riding together, playing lawn tennis, going into town, and entertaining relatives and friends, including "local aristocrats". Florence planned a Christmas party with 31 invited guests, including the mayor of Streatham

Streatham ( ) is a district in south London, England. Centred south of Charing Cross, it lies mostly within the London Borough of Lambeth, with some parts extending into the neighbouring London Borough of Wandsworth.

Streatham was in Surrey ...

. That Christmas, she apologised to her parents for all the pain she had caused. On 9 January, she sent them a telegram informing them she was pregnant. Charles jokingly referred to the baby as " Charles the Second".

Problems

By February 1876, it was clear that there was a power struggle within their relationship. Charles was particularly critical of Florence's extravagance, often saying that his mother disapproved. Florence had a butler, a footman, a "lady's maid", two housemaids, a cook, a kitchenmaid, three gardeners, a coachman, a groom, and a stable boy, in addition to Mrs Cox. Two weeks before the wedding, Charles fired her coachman of four years, George Griffiths. Once they were married, Charles confronted Florence and said that to curb expenses, he would fire her "lady's maid" and transfer her duties to another maid, Mary Ann Keeber; dismiss one of the gardeners; landscape the flower beds so they could fire yet another gardener; and sell her horses. Florence later stated, "I told him that he had no right to interfere in my arrangements...I reminded him that I had always lived within my means – and I was accustomed to looking after my own affairs." Charles then became agitated and lost his temper – the first of many heated arguments they would have. Charles also developed a jealous "obsession" with Dr Gully, who continued to live nearby, despite Florence's offer to buy out his lease. In December and January, Charles received three anonymous letters, all in the same handwriting, accusing him of marrying Florence for her money and referring to her as Dr Gully's mistress.Although Jane Cox told him that the handwriting did not appear to be Dr Gully's, Charles made up his mind that it was, and started reprimanding Florence for her past relationship, constantly questioning whether she was going to see him, and saying that he wanted to "annihilate" Gully. Florence left the Priory to stay at Buscot Park, complaining to her parents about Charles's "violent ebullitions of temper" and saying that his "meanness disgusted her". Charles sent her a series of apologetic letters, begging her to return home and promising, "If you come back, I will so take care of you that you will never leave me again." During her absence, however, staff at the Priory reported that Charles had called Florence "a selfish pig" who had been spoilt all her life, and that as her husband, he was right to stand up to her. According to Ruddick, Charles also took the opportunity to tell Jane Cox that he was dismissing her, but he would give her enough time to find a new position. Although he was grateful to Mrs Cox for bringing them together, Charles was jealous of her closeness with, and influence over, Florence, and had wanted to fire her for some time to reduce expenses.Miscarriages

Sadly, shortly after returning to Balham, Florence had a miscarriage. She became very weak, was bed-ridden, and grew depressed. After her doctor recommended "a change of air", Florence planned a holiday inWorthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Hov ...

, but Charles and his mother opposed the trip due to the expense. When Florence said she would confront his mother for interfering, Charles lost his temper, shouting, "I will go and cut my throat!" He then struck Florence, and stormed off. In March, Charles told Florence that he felt it was time for her to get pregnant again. By then, Florence doubted whether she would be able to carry a child to term, but a few weeks later she telegraphed her parents to inform them that she was pregnant for a second time. As she had feared, the second pregnancy also ended in miscarriage on 6 April 1876. Considerably weakened, she planned once more to travel to Worthing to rest and recover.

Death of Charles Bravo

Charles died less than five months after marrying Florence. On 18 April 1876, Florence and Charles went into town together, briefly quarrelling when their carriage passed Orwell Lodge. They stopped at the bank and at the jewellers on

Charles died less than five months after marrying Florence. On 18 April 1876, Florence and Charles went into town together, briefly quarrelling when their carriage passed Orwell Lodge. They stopped at the bank and at the jewellers on Bond Street

Bond Street in the West End of London links Piccadilly in the south to Oxford Street in the north. Since the 18th century the street has housed many prestigious and upmarket fashion retailers. The southern section is Old Bond Street and the l ...

, before going their separate ways. Florence went shopping on Haymarket Haymarket may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Haymarket, New South Wales, area of Sydney, Australia

Germany

* Heumarkt (KVB), transport interchange in Cologne on the site of the Heumarkt (literally: hay market)

Russia

* Sennaya Square (''Hay Squ ...

and bought hair lotion and premium tobacco for Charles as a "peace offering". Charles went to a Turkish bath

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited ...

on Jermyn Street

Jermyn Street is a one-way street in the St James's area of the City of Westminster in London, England. It is to the south of, parallel, and adjacent to Piccadilly. Jermyn Street is known as a street for gentlemen's-clothing retailers.

Hist ...

, and met her uncle, James Orr, for lunch at St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

.

Florence was resting in the morning room when he returned to the Priory. Charles decided to go riding, ignoring the groom's warning not to take any of the horses out since they had already exercised that day. The horse then bolted for four miles, taking him on a long and unpleasant ride. When Charles returned, he was stiff and exhausted. According to the butler Frederick Rowe, Charles was "in great pain", looking "exceedingly pale"; Florence said she had to help him to his feet when his bath was ready.

At dinner, Charles was extremely irritable toward both Florence and Mrs Cox, complaining that he was sore from the horse ride and that his toothache had returned. During the meal, he was angered to receive a letter from Joseph Bravo, criticising him for playing the stock market; his stepfather had opened a letter from Charles's stockbroker showing that he had sold shares at a loss. Before going to bed, Charles went into Florence's bedroom to scold her in French for drinking too much that day, as she had since the miscarriage; she had had champagne at lunch, a bottle of sherry at dinner, and had asked for two glasses of wine upstairs.

After Florence had fallen asleep, Charles suddenly burst out of his bedroom, shouting, "Florence! Florence! Hot water!" The maid, Mary Ann Keeber, was halfway down the stairs, waited for Florence to emerge, went back up the stairs, knocked on Florence's bedroom door, and alerted Mrs Cox . Mrs Cox ran to the other bedroom and found Charles vomiting out the window. He fainted, but Mrs Cox stayed with him rubbing his chest, and sent Mary Ann downstairs for mustard and hot water. They poured it down his throat, which caused him to vomit, but he remained unconscious. Mrs Cox told Mary Ann to tell the butler to send the coachman out to Streatham for Dr Harrison. Mary Ann then woke Florence, who got up saying, "What's the matter? What's the matter?" Alarmed to see Charles not moving, Florence held his hand, sobbing, and asked whether a doctor had been sent for. When Mrs Cox replied that she had sent for Dr Harrison, Florence was "horrified" and screamed for Rowe to get another doctor – any doctor – who was closer.

Diagnosis

Leading up to his death on 21 April 1876, Charles Bravo was seen by six medical professionals, including one of the most highly regarded physicians in England. The first two doctors were Dr Joseph Moore of Balham, who arrived first, and Dr George Harrison of Streatham, who arrived after midnight. Moore and Harrison conferred and agreed that it was a serious case of poisoning, and that Charles would die. They asked Florence, Mrs Cox, and Mary Ann if they had any idea what could have caused Charles's symptoms. Florence suggested that Charles had had a heart attack after the horse ride, and also mentioned that he was "prone to fainting fits" and that he had been "worried about stocks and shares". Dr Harrison told Mrs Cox that she was wrong when she suggested that Charles had ingested chloroform, and that the symptoms had likely been caused by

Leading up to his death on 21 April 1876, Charles Bravo was seen by six medical professionals, including one of the most highly regarded physicians in England. The first two doctors were Dr Joseph Moore of Balham, who arrived first, and Dr George Harrison of Streatham, who arrived after midnight. Moore and Harrison conferred and agreed that it was a serious case of poisoning, and that Charles would die. They asked Florence, Mrs Cox, and Mary Ann if they had any idea what could have caused Charles's symptoms. Florence suggested that Charles had had a heart attack after the horse ride, and also mentioned that he was "prone to fainting fits" and that he had been "worried about stocks and shares". Dr Harrison told Mrs Cox that she was wrong when she suggested that Charles had ingested chloroform, and that the symptoms had likely been caused by arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, but ...

, to which Florence responded, "Arsenic?" When he asked if there was any poison in the house, Florence answered, "Only rat poison, in the stables." She also stated that Charles had no reason to take poison.

Florence suggested sending for Royes Bell, Charles's cousin and best friend, who was an assistant surgeon at King's College Hospital

King's College Hospital is a major teaching hospital and major trauma centre in Denmark Hill, Camberwell in the London Borough of Lambeth, referred to locally and by staff simply as "King's" or abbreviated internally to "KCH". It is managed by K ...

in London, with his own practice on Harley Street

Harley Street is a street in Marylebone, Central London, which has, since the 19th century housed a large number of private specialists in medicine and surgery. It was named after Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.< ...

. Bell brought with him his superior, Dr George Johnson, who would later become vice-president of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

. Dr Johnson, in turn, brought in Henry Smith, another assistant surgeon at King's College Hospital and an in-law of Charles's mother. Charles awoke after his cousin arrived, and upon questioning, insisted to Bell and Johnson that the only substance he may have swallowed was laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Red ...

, which he had rubbed onto his own gums to treat his toothache. Mrs Cox took Bell aside and told him that before he fainted, Charles had said, "I have taken poison – don't tell Florence." She then repeated the claim in front of Dr Johnson and Dr Harrison; Dr Johnson asked if it was true, but Charles said he did not remember mentioning poison. Florence telegraphed his parents to come at once. Her father-in-law, Joseph Bravo, later stated that Florence "did not seem much grieved", and that she had given contradictory explanations for his condition. She told Charles's former nanny that she thought it was food poisoning from lunch, while she said to Royes Bell that what had happened to Charles would "always remain a mystery".

Finally, Florence wrote to Sir William Gull

Sir William Withey Gull, 1st Baronet (31 December 181629 January 1890) was an English physician. Of modest family origins, he established a lucrative private practice and served as Governor of Guy's Hospital, Fullerian Professor of Physiology ...

, a "leading English physician of his time", and requested that he see her husband who was "dangerously ill". Gull had become famous for saving the life of the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

) by diagnosing and treating typhoid. Florence later explained, "I believed that if anyone could save Charles, it was Sir William. I knew that he had saved people when others had given up all hope for them." Sir William knew her father "very well as a patient and an acquaintance"; they had dined together at the Reform Club

The Reform Club is a private members' club on the south side of Pall Mall in central London, England. As with all of London's original gentlemen's clubs, it comprised an all-male membership for decades, but it was one of the first all-male cl ...

. After examining Charles, Gull told Florence that he was sorry that nothing could be done to save his life. Gull pushed Charles repeatedly to reveal the name of the poison he had taken, but until the end, Charles insisted that he had only applied laudanum in his mouth, on his lower jaw, for neuralgia

Neuralgia (Greek ''neuron'', "nerve" + ''algos'', "pain") is pain in the distribution of one or more nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Classification

Under the general heading of neuralg ...

.

In his final hours, Florence offered to send for the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Streatham, but Charles declined. Instead, he recited the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

with his family. To Florence, he said, "Make no fuss when you bury me." He made a will favourable to Florence, witnessed by his cousin Bell and the butler Rowe. To his mother, he said, "Take care of my poor, dear wife." Charles Bravo was pronounced dead by Royes Bell at 5:20 am, 55 hours after he had collapsed.

Investigation

First inquest

The first coroner's inquest into Charles Bravo's death took place on 25 and 28 April 1876. Impressed by the credentials of the many doctors and surgeons who had examined Charles, the Coroner for East Surrey, William Carter, stated that the cause of death was likelysuicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

, and sought to "spare the feelings of the family" by keeping the inquiry private, perfunctory, and not calling Florence Bravo as a witness. Carter accepted Florence's request, written by Mrs Cox at the request of Joseph Bravo, to hold the inquest at the Priory, where she would provide refreshments – a practice which was not unusual at the time. The post mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

concluded that Charles had ingested thirty to forty grains – ten times the lethal dose – of tartar emetic

Antimony potassium tartrate, also known as potassium antimonyl tartrate, potassium antimontarterate, or tartar emetic, has the formula K2Sb2(C4H2O6)2. The compound has long been known as a powerful emetic, and was used in the treatment of schistos ...

, a derivative of antimony. Based on the evidence and testimony of the witnesses, the jury returned an open verdict, stating that there was "not sufficient evidence under what circumstances" the antimony had "entered his body".

Escalation

Friends and family of Charles Bravo objected to the implication that he had committed suicide, saying he had been "in his usual health and spirits". Troubled with how the inquest was handled, Barrister Carlyle Willoughby, a friend and colleague of Charles Bravo, contactedScotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

to voice his concerns. Joseph Bravo also spoke to the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

, and hired criminal lawyer George Lewis George Lewis may refer to:

Entertainment and art

* George B. W. Lewis (1818–1906), circus rider and theatre manager in Australia

* George E. Lewis (born 1952), American composer and free jazz trombonist

* George J. Lewis (1903–1995), Mexica ...

. Detective Chief Inspector George Clarke was assigned to investigate. On 8 May 1876, Florence, who was staying in Brighton, consented to Clarke's search of the Priory.

On 11 May 1876, ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' first brought national attention to the mystery surrounding Charles Bravo's death, denouncing the inquest as having been conducted in a "secret and unsatisfactory manner". The sensational article named some of the doctors, gave details about the dinner menu on the night of his death, and speculated that the Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

which he alone had drunk had been poisoned. On the advice of the Buscot Park physician and her father, for one week, Florence had her solicitor advertise a reward of £500 for anyone who could produce evidence of selling antimony to a member of the Priory household staff. At first, suspicion fell on George Griffiths, the coachman fired by Charles, who had reportedly shouted in a pub that "Mr Bravo would be dead in five months". The police found that a large quantity of tartar emetic had been sold by a chemist in Streatham to Griffiths in the summer of 1875, which he used on horses to eliminate worms and stored in the Priory stables. However, media interest in Griffiths subsided after it turned out he had moved to Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, and was not in the area when Charles Bravo was poisoned.

Soon, the newspapers were filled with gossip about Florence Ricardo's past affair with Dr Gully and recent sightings of Dr Gully together with Mrs Cox, as well as rumours that Mrs Cox had been fired, thus providing a motive. The accounts of Dr Harrison and Dr Moore were published in ''The Daily Telegraph'', while Dr Johnson shared his perspective in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles, ...

'', noting that Mrs Cox had initially claimed that Charles admitted to swallowing poison before fainting – a claim which Charles himself questioned when he woke up. On 18 May 1876, Serjean Simon, MP, asked Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

R. A. Cross in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

whether he was aware of the "unsatisfactory" nature of the coroner's inquest into the late Mr Bravo's death. Increasingly, suspicions were raised both publicly and privately about Mrs Cox. Florence suffered a collapse and "brain fever", while Mrs Cox abruptly left for the Priory to collect her belongings and move to other accommodations in London.

On 27 May 1876, ''The Daily Telegraph'' reported that the Treasury Solicitor, Augustus Keppel Stephenson

Sir Augustus Frederick William Keppel Stephenson, (18 October 1827 in London – 26 September 1904) was a Treasury Solicitor and the second person to hold the office of Director of Public Prosecutions in England and Wales.

Early life and family

...

, had concluded a preliminary inquiry of thirty witnesses, but that this did not include Mrs Bravo and Mrs Cox, implying that they were both suspects. Anxious to demonstrate their innocence, Florence and Mrs Cox each submitted written statements through their solicitor. Mrs Cox stated in writing that she had perjured herself and suppressed evidence during the first inquest, leading the Lord Chief Justice

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

Sir Alexander Cockburn

Sir Alexander James Edmund Cockburn, 12th Baronet (24 September 1802 – 20 November 1880) was a British jurist and politician who served as the Lord Chief Justice for 21 years. He heard some of the leading '' causes célèbres'' of the nine ...

to grant the Attorney General Sir John Holker

Sir John Holker (1828 – 24 May 1882) was a British lawyer, politician, and judge. He sat as a Member of Parliament for Preston from 1872 until his death ten years later. He was first Solicitor General and later Attorney General in the ...

's application to open a fresh inquiry. Florence received a torrent of anonymous hate mail through her letter box

A letter box, letterbox, letter plate, letter hole, mail slot or mailbox is a receptacle for receiving incoming mail at a private residence or business. For outgoing mail, Post boxes are often used for depositing the mail for collection, althou ...

in Brighton, and could no longer look out the window toward the Promenade without seeing passersby gazing up at her window. She paid her servants a month's wages and left Brighton for Buscot Park, before returning to the Priory.

Second inquest

The second coroner's inquest took place from 11 July through 11 August 1876, in the Bedford Hotel in Balham. It was attended by the Attorney General himself, with "eminent members of the Bar" holding briefs, and was covered extensively by members of the press. Over an unprecedented 23 days of testimony, members of the public crowded the streets to try to catch a glimpse of the witnesses giving evidence and find out the latest news each day.

Sir William Gull, "the most celebrated physician in England",appeared on the fourth day of the inquest. Gull stated that Charles "did not behave like a man who thought he was being murdered" and that "he had showed no surprise" that he was dying of poison. Gull believed that Charles had swallowed antimony intentionally but lost his nerve, and had asked for hot water to flush out his system, and remained convinced of Florence's complete innocence.

Interest in the case reached its peak when Florence testified for three days starting 3 August 1876. According author James Ruddick, "For Florence Bravo, the Coroner's inquest was the worst experience of her life." Rather than focusing on the circumstances leading up to Charles Bravo's death, his family's lawyers became fixated with proving that Florence had continued her affair with Dr Gully during their marriage, and subjected Florence, Dr Gully, and other witnesses to repeated questions about her past "sexual conduct". The lurid details of her "criminal intimacy" with Dr Gully before marrying Charles were covered in depth, in national newspapers such as ''

The second coroner's inquest took place from 11 July through 11 August 1876, in the Bedford Hotel in Balham. It was attended by the Attorney General himself, with "eminent members of the Bar" holding briefs, and was covered extensively by members of the press. Over an unprecedented 23 days of testimony, members of the public crowded the streets to try to catch a glimpse of the witnesses giving evidence and find out the latest news each day.

Sir William Gull, "the most celebrated physician in England",appeared on the fourth day of the inquest. Gull stated that Charles "did not behave like a man who thought he was being murdered" and that "he had showed no surprise" that he was dying of poison. Gull believed that Charles had swallowed antimony intentionally but lost his nerve, and had asked for hot water to flush out his system, and remained convinced of Florence's complete innocence.

Interest in the case reached its peak when Florence testified for three days starting 3 August 1876. According author James Ruddick, "For Florence Bravo, the Coroner's inquest was the worst experience of her life." Rather than focusing on the circumstances leading up to Charles Bravo's death, his family's lawyers became fixated with proving that Florence had continued her affair with Dr Gully during their marriage, and subjected Florence, Dr Gully, and other witnesses to repeated questions about her past "sexual conduct". The lurid details of her "criminal intimacy" with Dr Gully before marrying Charles were covered in depth, in national newspapers such as ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' and ''The Daily Telegraph'', as well as penny newspapers such as ''The Illustrated Police News

''The Illustrated Police News'' was a weekly illustrated newspaper which was one of the earliest British tabloids. It featured sensational and melodramatic reports and illustrations of murders and hangings and was a direct descendant of the exec ...

,'' and telegraphed by correspondents to newspapers across Europe, the US, and Australia. Florence broke down repeatedly, but on the third day of questioning about details of her sexual history with Dr Gull, she finally objected. According to ''The Times'', she said "part with tragic force and part tearfully" and with "perfectly just indignation":"That attachment to Dr Gully has nothing to do with this case—the death of Mr Bravo... I have been subjected to sufficient pain and humiliation already, and I appeal to the Coroner and the jury, as men and Britons, to protect me. I think it is great shame that I should be thus questioned, and I will refuse to answer any further questions with regard to Dr Gully."'' The Saturday Review'' reported that the audience was sympathetic, and "moved their feet as if applauding". Other commentators remarked ironically that Mr Bravo's own counsel had managed to "let the dead man's own 'criminal intimacy' with a prostitute at Maidenhead remain in decent obscurity." Nevertheless, the coroner allowed lawyer George Lewis to continue this line of questioning, unchecked. Over the course of the inquest, the likely method of transmission of poison was identified as Charles's water jug, which he drank from each night before going to bed. Although considerable suspicion of Florence remained, there was no direct evidence against her. Florence had not prepared food or given medicine to her husband, and had not signed for any poison in her name. In the end, the inquest failed to produce any meaningful new evidence. The Coroner's jury ruled out suicide and "death by misadventure" and found that Charles Bravo had been "wilfully murdered by the administration of tartar emetic" by an unknown person or persons.

Later life

Although Florence Bravo had avoided being indicted, the public shame and suspicion which persisted destroyed her life. Jane Cox was the first to pack her bags and leave, followed by her other servants, and she received notice that the landlord of The Priory was taking steps to evict her. Florence's eldest brother William Campbell urged her to move to Australia with him, but she refused. At the end of September 1876, she returned to the Priory and arranged for all its furnishings to be sold by auctioneers Bonham and Son. She changed her name to Florence Turner, and left London permanently on 3 April 1877. She settled in Southsea, Hampshire, where she bought a property called Lumps Villa, which she renamed Coombe Lodge, and hired a housekeeper, two maids, and a coachman. Florence rarely went out, and eventually drank herself to death, much like her first husband, and died on 17 September 1878, at the age of 33.Notes

References

Further reading

* Bridges, Yseult (1957). ''How Charles Bravo Died: The Chronicle of a Cause Célèbre.'' London: Reprint Society. * Ruddick, James (2001). ''Death at the Priory: Love, Sex, and Murder in Victorian England.'' New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.External links

Lady Killers with Lucy Worsley: Florence Bravo

(BBC Sounds)

Florence Bravo (née Campbell)

(National Portrait Gallery) {{authority control 1845 births 1878 deaths 19th-century British women