First Transcontinental Railroad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

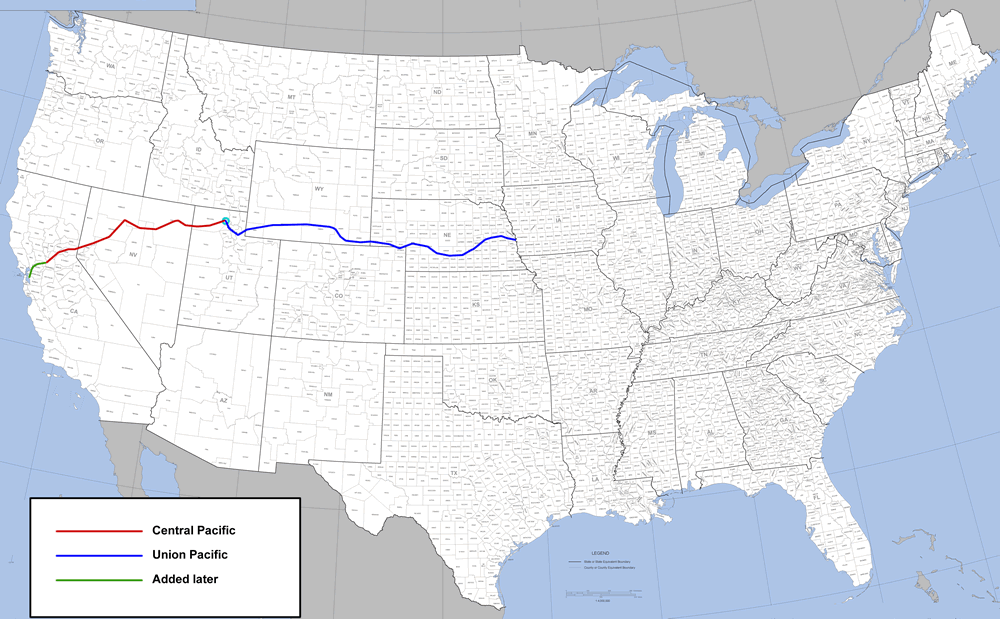

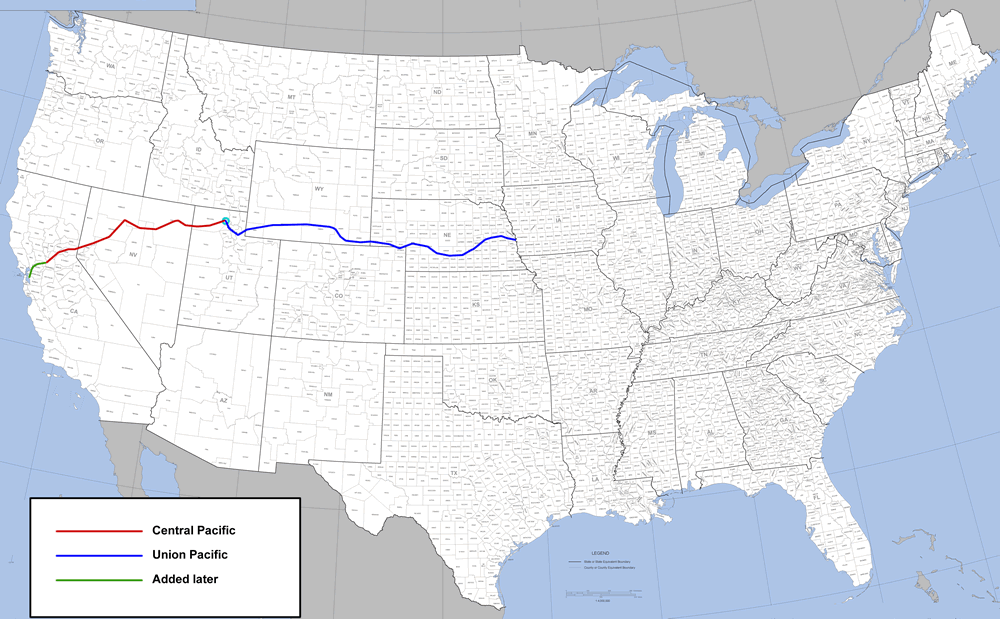

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail network at Council Bluffs, Iowa, with the Pacific coast at the Oakland Long Wharf on

(38th Congress, 1st Session SENATE Ex. Doc. No. 27). The railroad opened for through traffic between Sacramento and Omaha on May 10, 1869, when CPRR President

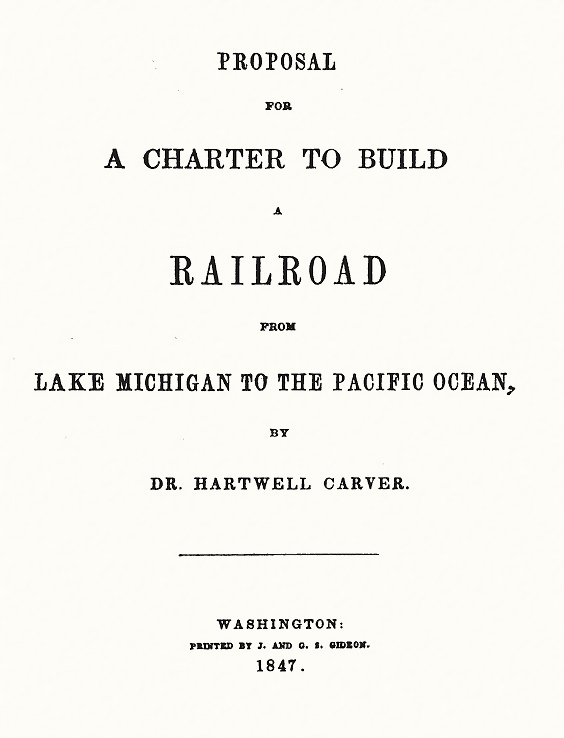

Among the early proponents of building a railroad line that would connect the coasts of the United States was Dr. Hartwell Carver, who in 1847 submitted to the U.S. Congress a "Proposal for a Charter to Build a Railroad from Lake Michigan to the Pacific Ocean", seeking a congressional charter to support his idea.Carver's 1847 proposal records himself as having written a newspaper article on the subject in 1837. Some sources say that he wrote such an article in 1832.

Among the early proponents of building a railroad line that would connect the coasts of the United States was Dr. Hartwell Carver, who in 1847 submitted to the U.S. Congress a "Proposal for a Charter to Build a Railroad from Lake Michigan to the Pacific Ocean", seeking a congressional charter to support his idea.Carver's 1847 proposal records himself as having written a newspaper article on the subject in 1837. Some sources say that he wrote such an article in 1832.

Congress agreed to support the idea. Under the direction of the Department of War, the Pacific Railroad Surveys were conducted from 1853 through 1855. These included an extensive series of expeditions of the American West seeking possible routes. A report on the explorations described alternative routes and included an immense amount of information about the

Congress agreed to support the idea. Under the direction of the Department of War, the Pacific Railroad Surveys were conducted from 1853 through 1855. These included an extensive series of expeditions of the American West seeking possible routes. A report on the explorations described alternative routes and included an immense amount of information about the

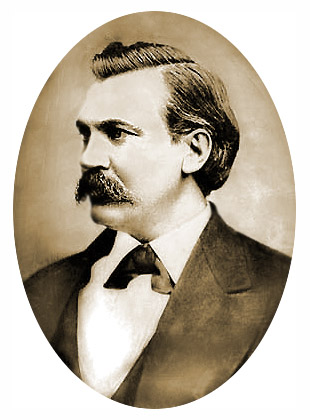

Theodore Judah was a fervent supporter of the central route railroad. He lobbied vigorously in favor of the project and undertook the survey of the route through the rugged Sierra Nevada, one of the chief obstacles of the project.

In 1852, Judah was chief engineer for the newly formed Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first railroad built west of the

Theodore Judah was a fervent supporter of the central route railroad. He lobbied vigorously in favor of the project and undertook the survey of the route through the rugged Sierra Nevada, one of the chief obstacles of the project.

In 1852, Judah was chief engineer for the newly formed Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first railroad built west of the

Four northern California businessmen formed the Central Pacific Railroad:

Four northern California businessmen formed the Central Pacific Railroad:

After 1864, the Central Pacific Railroad received the same Federal financial incentives as the Union Pacific Railroad, along with some construction bonds granted by the state of California and the city of San Francisco. The Central Pacific hired some Canadian and European civil engineers and surveyors with extensive experience building railroads, but it had a difficult time finding semi-skilled labor. Most Caucasians in California preferred to work in the mines or agriculture. The railroad experimented by hiring local emigrant Chinese as manual laborers, many of whom were escaping the poverty and terrors of the war (especially the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars) in the Sze Yup districts in the

After 1864, the Central Pacific Railroad received the same Federal financial incentives as the Union Pacific Railroad, along with some construction bonds granted by the state of California and the city of San Francisco. The Central Pacific hired some Canadian and European civil engineers and surveyors with extensive experience building railroads, but it had a difficult time finding semi-skilled labor. Most Caucasians in California preferred to work in the mines or agriculture. The railroad experimented by hiring local emigrant Chinese as manual laborers, many of whom were escaping the poverty and terrors of the war (especially the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars) in the Sze Yup districts in the

The Union Pacific's of track started at MP 0.0 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on the eastern side of the

The Union Pacific's of track started at MP 0.0 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on the eastern side of the  The Union Pacific reached the new railroad town of Cheyenne in December 1867, having laid about that year. They paused over the winter, preparing to push the track over Evans (Sherman's) Pass. At , Evans Pass was the highest point reached on the transcontinental railroad. About beyond Evans pass, the railroad had to build an extensive bridge over the Dale Creek canyon (). The Dale Creek Crossing was one of their more difficult railroad engineering challenges. Dale Creek Bridge was long and above Dale Creek. The bridge components were pre-built of timber in

The Union Pacific reached the new railroad town of Cheyenne in December 1867, having laid about that year. They paused over the winter, preparing to push the track over Evans (Sherman's) Pass. At , Evans Pass was the highest point reached on the transcontinental railroad. About beyond Evans pass, the railroad had to build an extensive bridge over the Dale Creek canyon (). The Dale Creek Crossing was one of their more difficult railroad engineering challenges. Dale Creek Bridge was long and above Dale Creek. The bridge components were pre-built of timber in

accessed August 2, 2013. The longest of four tunnels built in Weber Canyon was Tunnel 2. Work on this tunnel started in October 1868 and was completed six months later. Temporary tracks were laid around it and Tunnels 3 (), 4 () and 5 () to continue work on the tracks west of the tunnels. The tunnels were all made with the new dangerous nitroglycerine explosive, which expedited work but caused some fatal accidents. While building the railroad along the rugged Weber River Canyon, Mormon workers signed the Thousand Mile Tree which was a lone tree alongside the track from Omaha. A historic marker has been placed there. The tracks reached Ogden, Utah, on March 8, 1869, although finishing work would continue on the tracks, tunnels and bridges in Weber Canyon for over a year. From Ogden, the railroad went north of the Great Salt Lake to Brigham City and Corinne using Mormon workers, before finally connecting with the Central Pacific Railroad at Promontory Summit in Utah territory on May 10, 1869. Some Union Pacific officers declined to pay the Mormons all of the agreed upon construction costs of the work through Weber Canyon, and beyond, claiming Union Pacific poverty despite the millions they had extracted through the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal. Only partial payment was secured through court actions against Union Pacific.

In June 1864, the Central Pacific railroad entrepreneurs opened Dutch Flat and Donner Lake Wagon Road (DFDLWR). Costing about $300,000 and a years worth of work, this toll road wagon route was opened over much of the route the Central Pacific railroad (CPRR) would use over Donner Summit to carry freight and passengers needed by the CPRR and to carry other cargo over their toll road to and from the ever-advancing railhead and over the Sierra to the gold and silver mining towns of Nevada. As the railroad advanced, their freight rates with the combined rail and wagon shipments would become much more competitive. The volume of the toll road freight traffic to Nevada was estimated to be about $13,000,000 a year as the Comstock Lode boomed, and getting even part of this freight traffic would help pay for the railroad construction. When the railroad reached Reno, it had the majority of all Nevada freight shipments, and the price of goods in Nevada dropped significantly as the freight charges to Nevada dropped significantly. The rail route over the Sierras followed the general route of the Truckee branch of the California Trail, going east over Donner Pass and down the rugged

In June 1864, the Central Pacific railroad entrepreneurs opened Dutch Flat and Donner Lake Wagon Road (DFDLWR). Costing about $300,000 and a years worth of work, this toll road wagon route was opened over much of the route the Central Pacific railroad (CPRR) would use over Donner Summit to carry freight and passengers needed by the CPRR and to carry other cargo over their toll road to and from the ever-advancing railhead and over the Sierra to the gold and silver mining towns of Nevada. As the railroad advanced, their freight rates with the combined rail and wagon shipments would become much more competitive. The volume of the toll road freight traffic to Nevada was estimated to be about $13,000,000 a year as the Comstock Lode boomed, and getting even part of this freight traffic would help pay for the railroad construction. When the railroad reached Reno, it had the majority of all Nevada freight shipments, and the price of goods in Nevada dropped significantly as the freight charges to Nevada dropped significantly. The rail route over the Sierras followed the general route of the Truckee branch of the California Trail, going east over Donner Pass and down the rugged  In 1866, they put in a vertical shaft in the center of the summit tunnel and started work towards the east and west tunnel faces, giving four working faces on the summit tunnel to speed up progress. A steam engine off an old locomotive was brought up with much effort over the wagon road and used as a winch driver to help remove loosened rock from the vertical shaft and two working faces. By the winter of 1866–67, work had progressed sufficiently and a camp had been built for workers on the summit tunnel which allowed work to continue. The cross section of a tunnel face was a , oval with an vertical wall. Progress on the tunnel sped up to over per day per face when they started using the newly invented

In 1866, they put in a vertical shaft in the center of the summit tunnel and started work towards the east and west tunnel faces, giving four working faces on the summit tunnel to speed up progress. A steam engine off an old locomotive was brought up with much effort over the wagon road and used as a winch driver to help remove loosened rock from the vertical shaft and two working faces. By the winter of 1866–67, work had progressed sufficiently and a camp had been built for workers on the summit tunnel which allowed work to continue. The cross section of a tunnel face was a , oval with an vertical wall. Progress on the tunnel sped up to over per day per face when they started using the newly invented

Lewis Metzler Clement: A Pioneer of the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Photographic History Museum. Hills or ridges in front of the railroad road bed would have to have a flat-bottomed, V-shaped "cut" made to get the railroad through the ridge or hill. The type of material determined the slope of the V and how much material would have to be removed. Ideally, these cuts would be matched with valley fills that could use the dug out material to bring the road bed up to grade— cut and fill construction. In the 1860s there was no heavy equipment that could be used to make these cuts or haul it away to make the fills. The options were to dig it out by pick and shovel, haul the hillside material by wheelbarrow and/or horse or mule cart or blast it loose. To blast a V-shaped cut out, they had to drill several holes up to deep in the material, fill them with black powder, and blast the material away. Since the Central Pacific was in a hurry, they were profligate users of black powder to blast their way through the hills. The only disadvantage came when a nearby valley needed fill to get across it. The explosive technique often blew most of the potential fill material down the hillside, making it unavailable for fill. Initially, many valleys were bridged by "temporary" trestles that could be rapidly built and were later replaced by much lower maintenance and permanent solid fill. The existing railroad made transporting and putting material in valleys much easier—load it on railway dump cars, haul where needed and dump it over the side of the trestle. The route down the eastern Sierras was done on the south side of Donner Lake with a series of switchbacks carved into the mountain. The Truckee River, which drains

The route down the eastern Sierras was done on the south side of Donner Lake with a series of switchbacks carved into the mountain. The Truckee River, which drains

Most of the capital investment needed to build the railroad was generated by selling government-guaranteed bonds (granted per mile of completed track) to interested investors. The Federal donation of right-of-way saved money and time as it did not have to be purchased from others. The financial incentives and bonds would hopefully cover most of the initial capital investment needed to build the railroad. The bonds would be paid back by the sale of government-granted land, as well as prospective passenger and freight income. Most of the engineers and surveyors who figured out how and where to build the railroad on the Union Pacific were engineering college trained. Many of Union Pacific engineers and surveyors were Union Army veterans (including two generals) who had learned their railroad trade keeping the trains running and tracks maintained during the U.S. Civil War. After securing the finances and selecting the engineering team, the next step was to hire the key personnel and prospective supervisors. Nearly all key workers and supervisors were hired because they had previous railroad on-the-job training, knew what needed to be done and how to direct workers to get it done. After the key personnel were hired, the semi-skilled jobs could be filled if there was available labor. The engineering team's main job was to tell the workers where to go, what to do, how to do it, and provide the construction material they would need to get it done.

Survey teams were put out to produce detailed contour maps of the options on the different routes. The engineering team looked at the available surveys and chose what was the "best" route. Survey teams under the direction of the engineers closely led the work crews and marked where and by how much hills would have to be cut and depressions filled or bridged. Coordinators made sure that construction and other supplies were provided when and where needed, and additional supplies were ordered as the railroad construction consumed the supplies. Specialized bridging, explosive and tunneling teams were assigned to their specialized jobs. Some jobs like explosive work, tunneling, bridging, heavy cuts or fills were known to take longer than others, so the specialized teams were sent out ahead by wagon trains with the supplies and men to get these jobs done by the time the regular track-laying crews arrived. Finance officers made sure the supplies were paid for and men paid for their work. An army of men had to be coordinated and a seemingly never-ending chain of supplies had to be provided. The Central Pacific road crew set a track-laying record by laying of track in a single day, commemorating the event with a signpost beside the track for passing trains to see.

In addition to the track-laying crews, other crews were busy setting up stations with provisions for loading fuel, water and often also mail, passengers and freight. Personnel had to be hired to run these stations. Maintenance depots had to be built to keep all of the equipment repaired and operational. Telegraph operators had to be hired to man each station to keep track of where the trains were so that trains could run in each direction on the available single track without interference or accidents. Sidings had to be built to allow trains to pass. Provision had to be made to store and continually pay for coal or wood needed to run the

Most of the capital investment needed to build the railroad was generated by selling government-guaranteed bonds (granted per mile of completed track) to interested investors. The Federal donation of right-of-way saved money and time as it did not have to be purchased from others. The financial incentives and bonds would hopefully cover most of the initial capital investment needed to build the railroad. The bonds would be paid back by the sale of government-granted land, as well as prospective passenger and freight income. Most of the engineers and surveyors who figured out how and where to build the railroad on the Union Pacific were engineering college trained. Many of Union Pacific engineers and surveyors were Union Army veterans (including two generals) who had learned their railroad trade keeping the trains running and tracks maintained during the U.S. Civil War. After securing the finances and selecting the engineering team, the next step was to hire the key personnel and prospective supervisors. Nearly all key workers and supervisors were hired because they had previous railroad on-the-job training, knew what needed to be done and how to direct workers to get it done. After the key personnel were hired, the semi-skilled jobs could be filled if there was available labor. The engineering team's main job was to tell the workers where to go, what to do, how to do it, and provide the construction material they would need to get it done.

Survey teams were put out to produce detailed contour maps of the options on the different routes. The engineering team looked at the available surveys and chose what was the "best" route. Survey teams under the direction of the engineers closely led the work crews and marked where and by how much hills would have to be cut and depressions filled or bridged. Coordinators made sure that construction and other supplies were provided when and where needed, and additional supplies were ordered as the railroad construction consumed the supplies. Specialized bridging, explosive and tunneling teams were assigned to their specialized jobs. Some jobs like explosive work, tunneling, bridging, heavy cuts or fills were known to take longer than others, so the specialized teams were sent out ahead by wagon trains with the supplies and men to get these jobs done by the time the regular track-laying crews arrived. Finance officers made sure the supplies were paid for and men paid for their work. An army of men had to be coordinated and a seemingly never-ending chain of supplies had to be provided. The Central Pacific road crew set a track-laying record by laying of track in a single day, commemorating the event with a signpost beside the track for passing trains to see.

In addition to the track-laying crews, other crews were busy setting up stations with provisions for loading fuel, water and often also mail, passengers and freight. Personnel had to be hired to run these stations. Maintenance depots had to be built to keep all of the equipment repaired and operational. Telegraph operators had to be hired to man each station to keep track of where the trains were so that trains could run in each direction on the available single track without interference or accidents. Sidings had to be built to allow trains to pass. Provision had to be made to store and continually pay for coal or wood needed to run the

The manual labor to build the Central Pacific's roadbed, bridges and tunnels was done primarily by many thousands of emigrant workers from China under the direction of skilled non-Chinese supervisors. The Chinese were commonly referred to at the time as " Celestials" and China as the "Celestial Kingdom". Labor-saving devices in those days consisted primarily of wheelbarrows, horse or mule pulled carts, and a few railroad pulled gondolas. The construction work involved an immense amount of manual labor. Initially, Central Pacific had a hard time hiring and keeping unskilled workers on its line, as many would leave for the prospect of far more lucrative gold or silver mining options elsewhere. Despite the concerns expressed by Charles Crocker, one of the "big four" and a general contractor, that the Chinese were too small in stature and lacking previous experience with railroad work, they decided to try them anyway. After the first few days of trial with a few workers, with noticeably positive results, Crocker decided to hire as many as he could, looking primarily at the California labor force, where the majority of Chinese worked as independent gold miners or in the service industries (e.g.: laundries and kitchens). Most of these Chinese workers were represented by a Chinese "boss" who translated, collected salaries for his crew, kept discipline and relayed orders from an American general supervisor. Most Chinese workers spoke only rudimentary or no English, and the supervisors typically only learned rudimentary Chinese. Many more workers were imported from the

The manual labor to build the Central Pacific's roadbed, bridges and tunnels was done primarily by many thousands of emigrant workers from China under the direction of skilled non-Chinese supervisors. The Chinese were commonly referred to at the time as " Celestials" and China as the "Celestial Kingdom". Labor-saving devices in those days consisted primarily of wheelbarrows, horse or mule pulled carts, and a few railroad pulled gondolas. The construction work involved an immense amount of manual labor. Initially, Central Pacific had a hard time hiring and keeping unskilled workers on its line, as many would leave for the prospect of far more lucrative gold or silver mining options elsewhere. Despite the concerns expressed by Charles Crocker, one of the "big four" and a general contractor, that the Chinese were too small in stature and lacking previous experience with railroad work, they decided to try them anyway. After the first few days of trial with a few workers, with noticeably positive results, Crocker decided to hire as many as he could, looking primarily at the California labor force, where the majority of Chinese worked as independent gold miners or in the service industries (e.g.: laundries and kitchens). Most of these Chinese workers were represented by a Chinese "boss" who translated, collected salaries for his crew, kept discipline and relayed orders from an American general supervisor. Most Chinese workers spoke only rudimentary or no English, and the supervisors typically only learned rudimentary Chinese. Many more workers were imported from the

The first step of construction was to survey the route and determine the locations where large excavations, tunnels and bridges would be needed. Crews could then start work in advance of the railroad reaching these locations. Supplies and workers were brought up to the work locations by wagon teams and work on several different sections proceeded simultaneously. One advantage of working on tunnels in winter was that tunnel work could often proceed since the work was nearly all "inside". Living quarters would have to be built outside and getting new supplies was difficult. Working and living in winter in the presence of snow slides and avalanches caused some deaths.

To carve a tunnel, one worker held a rock drill on the granite face while one to two other workers swung eighteen-pound sledgehammers to sequentially hit the drill which slowly advanced into the rock. Once the hole was about deep, it would be filled with black powder, a fuse set and then ignited from a safe distance. Nitroglycerin, which had been invented less than two decades before the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, was used in relatively large quantities during its construction. This was especially true on the Central Pacific Railroad, which owned its own nitroglycerin plant to ensure it had a steady supply of the volatile explosive. This plant was operated by Chinese laborers as they were willing workers even under the most trying and dangerous of conditions.

Chinese laborers were also crucial in the construction of 15 tunnels along the railroad's line through the Sierra Nevada mountains. These were about high and wide.Tzu-Kuei, "Chinese Workers and the First Transcontinental Railroad of the United States of America", p. 128. When tunnels with vertical shafts were dug to increase construction speed, tunneling began in the middle of the tunnel and at both ends simultaneously. At first hand-powered

The first step of construction was to survey the route and determine the locations where large excavations, tunnels and bridges would be needed. Crews could then start work in advance of the railroad reaching these locations. Supplies and workers were brought up to the work locations by wagon teams and work on several different sections proceeded simultaneously. One advantage of working on tunnels in winter was that tunnel work could often proceed since the work was nearly all "inside". Living quarters would have to be built outside and getting new supplies was difficult. Working and living in winter in the presence of snow slides and avalanches caused some deaths.

To carve a tunnel, one worker held a rock drill on the granite face while one to two other workers swung eighteen-pound sledgehammers to sequentially hit the drill which slowly advanced into the rock. Once the hole was about deep, it would be filled with black powder, a fuse set and then ignited from a safe distance. Nitroglycerin, which had been invented less than two decades before the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, was used in relatively large quantities during its construction. This was especially true on the Central Pacific Railroad, which owned its own nitroglycerin plant to ensure it had a steady supply of the volatile explosive. This plant was operated by Chinese laborers as they were willing workers even under the most trying and dangerous of conditions.

Chinese laborers were also crucial in the construction of 15 tunnels along the railroad's line through the Sierra Nevada mountains. These were about high and wide.Tzu-Kuei, "Chinese Workers and the First Transcontinental Railroad of the United States of America", p. 128. When tunnels with vertical shafts were dug to increase construction speed, tunneling began in the middle of the tunnel and at both ends simultaneously. At first hand-powered  In order to keep the CPRR's Sierra grade open during the winter months, beginning in 1867, of massive wooden snow sheds and galleries were built between Blue Cañon and Truckee, covering cuts and other points where there was danger of avalanches. 2,500 men and six material trains were employed in this work, which was completed in 1869. The sheds were built with two sides and a steep peaked roof, mostly of locally cut hewn timber and round logs. Snow galleries had one side and a roof that sloped upward until it met the mountainside, thus permitting avalanches to slide over the galleries, some of which extended up the mountainside as much as . Masonry walls such as the "Chinese Walls" at Donner Summit were built across canyons to prevent avalanches from striking the side of the vulnerable wooden construction. A few concrete sheds (mostly at crossovers) are still in use today.

In order to keep the CPRR's Sierra grade open during the winter months, beginning in 1867, of massive wooden snow sheds and galleries were built between Blue Cañon and Truckee, covering cuts and other points where there was danger of avalanches. 2,500 men and six material trains were employed in this work, which was completed in 1869. The sheds were built with two sides and a steep peaked roof, mostly of locally cut hewn timber and round logs. Snow galleries had one side and a roof that sloped upward until it met the mountainside, thus permitting avalanches to slide over the galleries, some of which extended up the mountainside as much as . Masonry walls such as the "Chinese Walls" at Donner Summit were built across canyons to prevent avalanches from striking the side of the vulnerable wooden construction. A few concrete sheds (mostly at crossovers) are still in use today.

The major investor in the Union Pacific was Thomas Clark Durant, who had made his stake money by smuggling Confederate cotton with the aid of Grenville M. Dodge. Durant chose routes that would favor places where he held land, and he announced connections to other lines at times that suited his share dealings. He paid an associate to submit the construction bid to another company he controlled, Crédit Mobilier, manipulating the finances and government subsidies and making himself another fortune. Durant hired Dodge as chief engineer and Jack Casement as construction boss.

In the East, the progress started in Omaha, Nebraska, by the Union Pacific Railroad which initially proceeded very quickly because of the open terrain of the

The major investor in the Union Pacific was Thomas Clark Durant, who had made his stake money by smuggling Confederate cotton with the aid of Grenville M. Dodge. Durant chose routes that would favor places where he held land, and he announced connections to other lines at times that suited his share dealings. He paid an associate to submit the construction bid to another company he controlled, Crédit Mobilier, manipulating the finances and government subsidies and making himself another fortune. Durant hired Dodge as chief engineer and Jack Casement as construction boss.

In the East, the progress started in Omaha, Nebraska, by the Union Pacific Railroad which initially proceeded very quickly because of the open terrain of the

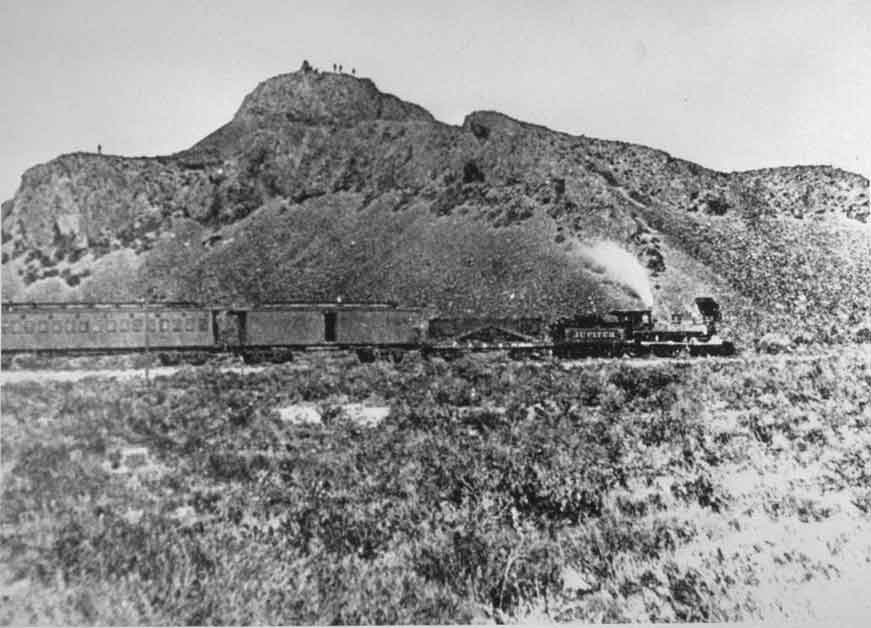

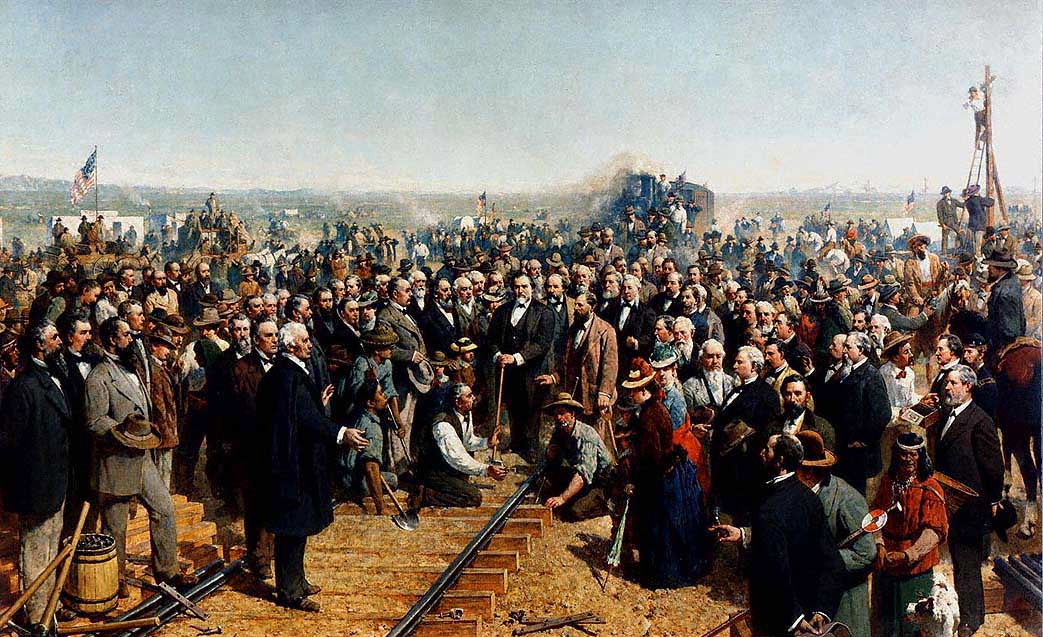

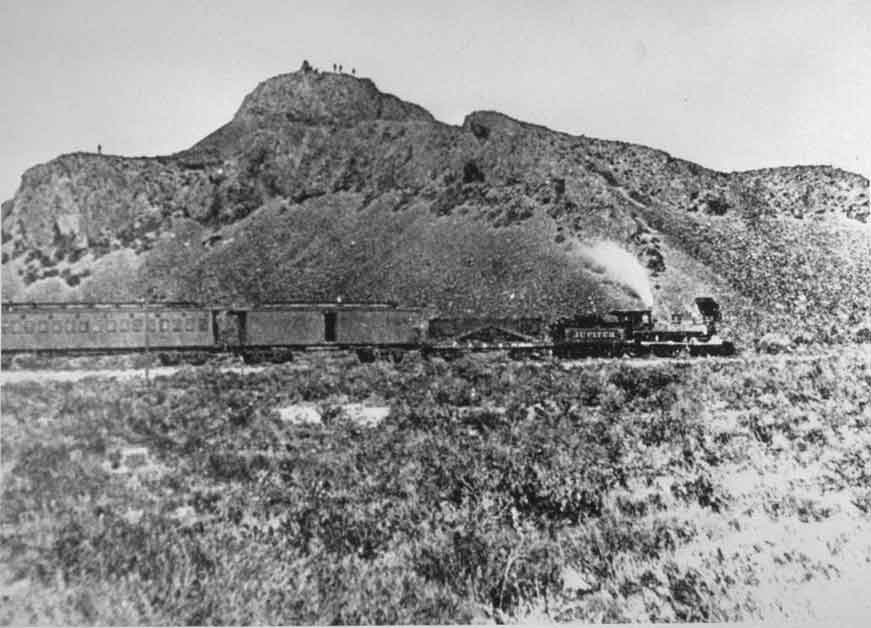

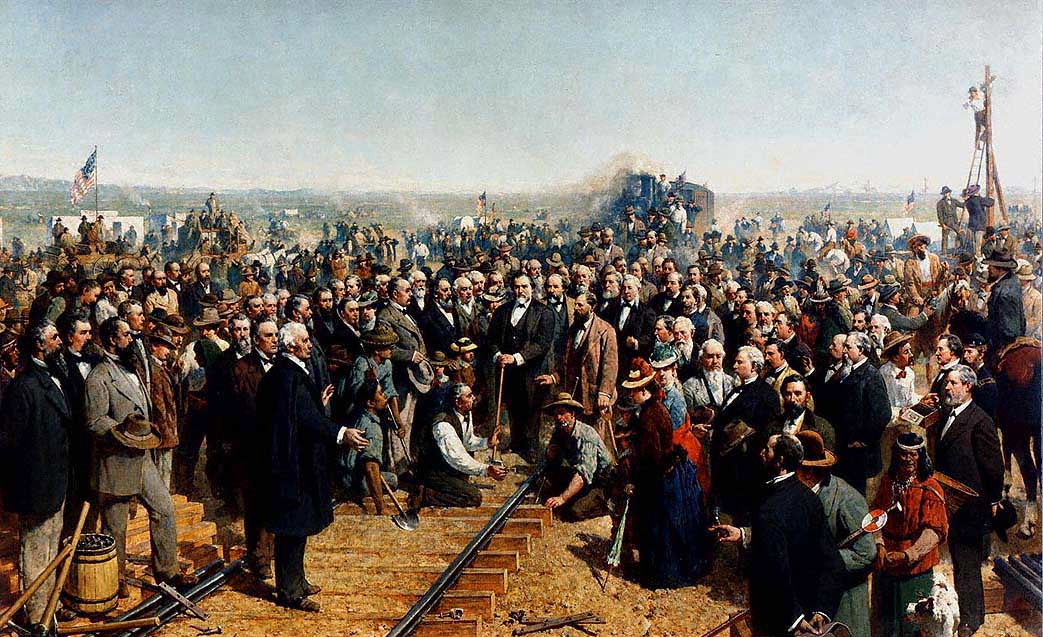

Six years after the groundbreaking, laborers of the Central Pacific Railroad from the west and the Union Pacific Railroad from the east met at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. On the Union Pacific side was Union Pacific No 119, an 1868 4-4-0 type. Thrusting westward, the last two rails were laid by Irishmen. On the Central Pacific side was their Central Pacific No 60 Jupiter, another 1868 4-4-0 type. Thrusting eastward, the last two rails were laid by the Chinese.

It was at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869, that the two engines met. Leland Stanford drove ''The Last Spike'' (or

Six years after the groundbreaking, laborers of the Central Pacific Railroad from the west and the Union Pacific Railroad from the east met at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. On the Union Pacific side was Union Pacific No 119, an 1868 4-4-0 type. Thrusting westward, the last two rails were laid by Irishmen. On the Central Pacific side was their Central Pacific No 60 Jupiter, another 1868 4-4-0 type. Thrusting eastward, the last two rails were laid by the Chinese.

It was at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869, that the two engines met. Leland Stanford drove ''The Last Spike'' (or

Despite the transcontinental success and millions in government subsidies, the Union Pacific faced bankruptcy less than three years after the Last Spike as details surfaced about overcharges that Crédit Mobilier had billed Union Pacific for the formal building of the railroad. The scandal hit epic proportions in the 1872 United States presidential election, which saw the re-election of Ulysses S. Grant and became the biggest scandal of the Gilded Age. It would not be resolved until the death of the congressman who was supposed to have reined in its excesses but instead wound up profiting from it.

Durant had initially come up with the scheme to have Crédit Mobilier subcontract to do the actual track work. Durant gained control of the company after buying out employee Herbert Hoxie for $10,000. Under Durant's guidance, Crédit Mobilier was charging Union Pacific often twice or more the customary cost for track work. The process mired down Union Pacific work.

Lincoln asked Massachusetts Congressman

Despite the transcontinental success and millions in government subsidies, the Union Pacific faced bankruptcy less than three years after the Last Spike as details surfaced about overcharges that Crédit Mobilier had billed Union Pacific for the formal building of the railroad. The scandal hit epic proportions in the 1872 United States presidential election, which saw the re-election of Ulysses S. Grant and became the biggest scandal of the Gilded Age. It would not be resolved until the death of the congressman who was supposed to have reined in its excesses but instead wound up profiting from it.

Durant had initially come up with the scheme to have Crédit Mobilier subcontract to do the actual track work. Durant gained control of the company after buying out employee Herbert Hoxie for $10,000. Under Durant's guidance, Crédit Mobilier was charging Union Pacific often twice or more the customary cost for track work. The process mired down Union Pacific work.

Lincoln asked Massachusetts Congressman

Visible remains of the historic line are still easily located—hundreds of miles are still in service today, especially through the Sierra Nevada Mountains and canyons in Utah and Wyoming. While the original rail has long since been replaced because of age and wear, and the roadbed upgraded and repaired, the lines generally run on top of the original, handmade grade. Vista points on Interstate 80 through California's Truckee Canyon provide a panoramic view of many miles of the original Central Pacific line and of the snow sheds which made winter train travel safe and practical.

In areas where the original line has been bypassed and abandoned, primarily because of the Lucin Cutoff re-route in Utah, the original road grade is still obvious, as are numerous cuts and fills, especially the Big Fill a few miles east of Promontory. The sweeping curve which connected to the east end of the Big Fill now passes a Thiokol rocket research and development facility.

In 1957, Congress authorized the Golden Spike National Historic Site, which was redesignated the Golden Spike National Historical Park in 2019. Today the site features replica engines of Union Pacific No. 119 and Central Pacific

Visible remains of the historic line are still easily located—hundreds of miles are still in service today, especially through the Sierra Nevada Mountains and canyons in Utah and Wyoming. While the original rail has long since been replaced because of age and wear, and the roadbed upgraded and repaired, the lines generally run on top of the original, handmade grade. Vista points on Interstate 80 through California's Truckee Canyon provide a panoramic view of many miles of the original Central Pacific line and of the snow sheds which made winter train travel safe and practical.

In areas where the original line has been bypassed and abandoned, primarily because of the Lucin Cutoff re-route in Utah, the original road grade is still obvious, as are numerous cuts and fills, especially the Big Fill a few miles east of Promontory. The sweeping curve which connected to the east end of the Big Fill now passes a Thiokol rocket research and development facility.

In 1957, Congress authorized the Golden Spike National Historic Site, which was redesignated the Golden Spike National Historical Park in 2019. Today the site features replica engines of Union Pacific No. 119 and Central Pacific

The feat is depicted in various movies, including the 1939 film ''

The feat is depicted in various movies, including the 1939 film ''

''"Riding the Transcontinental Rails: Overland Travel on the Pacific Railroad 1865–1881"''

(2005), Polyglot Press, Philadelphia * Cooper, Bruce Clement (Ed), ''"The Classic Western American Railroad Routes"''. New York: Chartwell Books/Worth Press, 2010. ; BINC: 3099794. * Duran, Xavier, "The First U.S. Transcontinental Railroad: Expected Profits and Government Intervention," ''Journal of Economic History,'' 73 (March 2013), 177–200. * * * White, Richard. ''Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America'' (2010) * Willumson, Glenn. ''Iron Muse: Photographing the Transcontinental Railroad'' (University of California Press; 2013) 242 pages; studies the production, distribution, and publication of images of the railroad in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum

"Map of the Central Pacific Railroad and its Connections" published in the California Mail Bag San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser, Vol. 1, No. 4, Oct–Nov. 1871. accessed May 1, 2013. * Union Pacific Railroad picture Museu

accessed March 1, 2013. *

The Pacific Tourist

' Williams, Henry T.; published by Adams & Bishop, New York, 1881 ed. Gives insights to travel in the late 1880s on the transcontinental railroad.

"I Hear the Locomotives: The Impact of the Transcontinental Railroad"

in Utah

The Transcontinental Railroad

* ttp://cprr.org/Museum/Chinese.html Chinese-American Contribution to transcontinental railroad

Linda Hall Library's Transcontinental Railroad educational site with free, full-text access to 19th century American railroad periodicals

Newspaper articles and clippings about the Transcontinental Railroad at Newspapers.com

; Maps * ttps://www.loc.gov/collection/railroad-maps-1828-to-1900/?q=continental%20railway&fi=subject Route map at the Library of Congress

Map of Union Pacific Railroad with Dates

Abandoned route of the transcontinental railroad in Utah (with map)

Geography of Chinese Workers Building the Transcontinental Railroad

"''A virtual reconstruction of the key historic sites''" – Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project; Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) at

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

. The rail line was built by three private companies over public lands provided by extensive U.S. land grants.Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, §2 & §3 Building was financed by both state and U.S. government subsidy bonds as well as by company-issued mortgage bonds.Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, §5 & §6 The Western Pacific Railroad Company built of track from the road's western terminus at Alameda/ Oakland to Sacramento, California

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of California and the county seat, seat of Sacramento County, California, Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento Rive ...

. The Central Pacific Railroad Company of California (CPRR) constructed east from Sacramento to Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. The Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Railroad classes, Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United Stat ...

(UPRR) built from the road's eastern terminus at the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

settlements of Council Bluffs and Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, westward to Promontory Summit.Executive Order of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, Fixing the Point of Commencement of the Union Pacific Railroad at Council Bluffs, Iowa, dated March 7, 1864(38th Congress, 1st Session SENATE Ex. Doc. No. 27). The railroad opened for through traffic between Sacramento and Omaha on May 10, 1869, when CPRR President

Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American attorney, industrialist, philanthropist, and Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician from Watervliet, New York. He served as the eighth governor of Calif ...

ceremonially tapped the gold "Last Spike" (later often referred to as the "Golden Spike

The golden spike (also known as the last spike) is the ceremonial 17.6-Carat (purity), karat gold final Rail spike, spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States connecting t ...

") with a silver hammer at Promontory Summit. In the following six months, the last leg from Sacramento to San Francisco Bay was completed. The resulting coast-to-coast railroad connection revolutionized the settlement and economy of the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

. It brought the western states and territories into alignment with the northern Union states and made transporting passengers and goods coast-to-coast considerably quicker, safer and less expensive.

The first transcontinental rail passengers arrived at the Pacific Railroad's original western terminus at the Alameda Terminal on September 6, 1869, where they transferred to the steamer ''Alameda'' for transport across the Bay to San Francisco. The road's rail terminus was moved two months later to the Oakland Long Wharf, about a mile to the north, when its expansion was completed and opened for passengers on November 8, 1869. Service between San Francisco and Oakland Pier continued to be provided by ferry.

The CPRR eventually purchased of UPRR-built grade from Promontory Summit (MP 828) to Ogden, Utah Territory (MP 881), which became the interchange point between trains of the two roads. The transcontinental line became popularly known as the '' Overland Route'' after the name of the principal passenger rail service to Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

that operated over the length of the line until 1962.

Overall significance

Railroads not only increased the speed of transport, they also dramatically lowered its cost. The first transcontinental railroad resulted in passengers and freight being able to cross the country in a matter of days instead of months and at one tenth the cost of stagecoach or wagon transport. With economical transportation in the West (which had been referred to as theGreat American Desert

The term Great American Desert was used in the 19th century to describe the part of North America east of the Rocky Mountains to approximately the 100th meridian west, 100th meridian. It can be traced to Stephen Harriman Long, Stephen H. Long's ...

) now farming, ranching and mining could be done at a profit. As a result, railroads transformed the country, particularly the West (which had few navigable rivers).

For example, before the railroads were built in the West, if a farmer were to ship a load of corn only 200 miles to Chicago, the shipping cost by wagon would exceed the price for which the corn could be sold. So, under such circumstances, farming could not be done at a profit. Mining and other economic activity in the West were similarly inhibited because of the high cost of wagon transportation. One Congressman, referring to the West, bluntly stated that, “All that land wasn’t worth ten cents until the railroads came.”

Freight rates by rail were a small fraction of what they had been with wagon transport. When the United States concluded the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

in 1803, people thought that it would take 300 years to populate it. With the introduction of the railroad, it took only 30 years. The low cost of shipping by rail resulted in the Great American Desert

The term Great American Desert was used in the 19th century to describe the part of North America east of the Rocky Mountains to approximately the 100th meridian west, 100th meridian. It can be traced to Stephen Harriman Long, Stephen H. Long's ...

becoming the great American breadbasket.

Origins

Among the early proponents of building a railroad line that would connect the coasts of the United States was Dr. Hartwell Carver, who in 1847 submitted to the U.S. Congress a "Proposal for a Charter to Build a Railroad from Lake Michigan to the Pacific Ocean", seeking a congressional charter to support his idea.Carver's 1847 proposal records himself as having written a newspaper article on the subject in 1837. Some sources say that he wrote such an article in 1832.

Among the early proponents of building a railroad line that would connect the coasts of the United States was Dr. Hartwell Carver, who in 1847 submitted to the U.S. Congress a "Proposal for a Charter to Build a Railroad from Lake Michigan to the Pacific Ocean", seeking a congressional charter to support his idea.Carver's 1847 proposal records himself as having written a newspaper article on the subject in 1837. Some sources say that he wrote such an article in 1832.

Preliminary exploration

Congress agreed to support the idea. Under the direction of the Department of War, the Pacific Railroad Surveys were conducted from 1853 through 1855. These included an extensive series of expeditions of the American West seeking possible routes. A report on the explorations described alternative routes and included an immense amount of information about the

Congress agreed to support the idea. Under the direction of the Department of War, the Pacific Railroad Surveys were conducted from 1853 through 1855. These included an extensive series of expeditions of the American West seeking possible routes. A report on the explorations described alternative routes and included an immense amount of information about the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

, covering at least . It included the region's natural history and illustrations of reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals.

The report did not include detailed topographic map

In modern mapping, a topographic map or topographic sheet is a type of map characterized by large- scale detail and quantitative representation of relief features, usually using contour lines (connecting points of equal elevation), but histori ...

s of potential routes needed to estimate the feasibility, cost and select the best route. However, the survey was detailed enough to determine that the best southern route lay south of the Gila River boundary with Mexico in mostly vacant desert, through the future territories of Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

and New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

. This in part motivated the United States to complete the Gadsden Purchase.

In 1856, the Select Committee on the Pacific Railroad and Telegraph of the US House of Representatives published a report recommending support for a proposed Pacific railroad bill:

Possible routes

The U.S. Congress was strongly divided on where the eastern terminus of the railroad should be—in a southern or northern city. Three routes were considered: * A northern route roughly along the Missouri River through present-day northernMontana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

to Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

. This was considered impractical because of the rough terrain and extensive winter snows.Later, the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) found and built a better route across the northern tier of the western United States from Minnesota to the Pacific Coast. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, which it used to raise money in Europe. Construction began in 1870 and the main line opened all the way from the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

on September 8, 1883.

* A central route following the Platte River in Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

through to the South Pass in Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, following most of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in North America that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon Territory. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail crossed what ...

. Snow on this route remained a concern.

* A southern route across Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, New Mexico Territory, the Sonora desert, connecting to Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, California. Surveyors found during an 1848 survey that the best route lay south of the border between the United States and Mexico. This was resolved by the Gadsden Purchase in 1853.The southern route was constructed in 1880 when the Southern Pacific Railroad crossed Arizona territory.

Once the central route was chosen, it was immediately obvious that the western terminus should be Sacramento. But there was considerable difference of opinion about the eastern terminus. Three locations along of Missouri River were considered:

* St. Joseph, Missouri, accessed via the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad.

* Kansas City, Kansas / Leavenworth, Kansas

Leavenworth () is the county seat and largest city of Leavenworth County, Kansas, Leavenworth County, Kansas, United States. Part of the Kansas City metropolitan area, Leavenworth is located on the west bank of the Missouri River, on the site o ...

, accessed via the Leavenworth, Pawnee and Western Railroad, controlled by Thomas Ewing Jr. and later by John C. Frémont.

* Council Bluffs, Iowa / Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, accessed via an extension of Union Pacific financier Thomas C. Durant's proposed Mississippi and Missouri Railroad and the new Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Railroad classes, Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United Stat ...

, also controlled by Durant.

Council Bluffs had several advantages: It was well north of the Civil War fighting in Missouri; it was the shortest route to South Pass in the Rockies in Wyoming; and it would follow a fertile river that would encourage settlement. Durant had hired the future president Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

in 1857 when he was an attorney to represent him in a business matter about a bridge over the Missouri. Now Lincoln was responsible for choosing the eastern terminus, and he relied on Durant's counsel.

Key people

Asa Whitney

One of the most prominent champions of the central route railroad was Asa Whitney. He envisioned a route from Chicago and the Great Lakes to northern California, paid for by the sale of land to settlers along the route. Whitney traveled widely to solicit support from businessmen and politicians, printed maps and pamphlets, and submitted several proposals to Congress, all at his own expense. In June 1845, he led a team along part of the proposed route to assess its feasibility. Legislation to begin construction of the ''Pacific Railroad'' (called the ''Memorial of Asa Whitney'') was first introduced to Congress by Representative Zadock Pratt. Congress did not immediately act on Whitney's proposal.Theodore Judah

Theodore Judah was a fervent supporter of the central route railroad. He lobbied vigorously in favor of the project and undertook the survey of the route through the rugged Sierra Nevada, one of the chief obstacles of the project.

In 1852, Judah was chief engineer for the newly formed Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first railroad built west of the

Theodore Judah was a fervent supporter of the central route railroad. He lobbied vigorously in favor of the project and undertook the survey of the route through the rugged Sierra Nevada, one of the chief obstacles of the project.

In 1852, Judah was chief engineer for the newly formed Sacramento Valley Railroad, the first railroad built west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. Although the railroad later went bankrupt once the easy placer gold deposits around Placerville, California, were depleted, Judah was convinced that a properly financed railroad could pass from Sacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

through the Sierra Nevada mountains to reach the Great Basin and hook up with rail lines coming from the East.

In 1856, Judah wrote a 13,000-word proposal in support of a Pacific railroad and distributed it to Cabinet secretaries, congressmen and other influential people. In September 1859, Judah was chosen to be the accredited lobbyist for the Pacific Railroad Convention, which indeed approved his plan to survey, finance and engineer the road. Judah returned to Washington in December 1859. He had a lobbying office in the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

, received an audience with President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, and represented the Convention before Congress."A Memorial and Biographical History of Northern California: Illustrated. Containing a History of This Important Section of the Pacific Coast from the Earliest Period of Its Occupancyand Biographical Mention of Many of Its Most Eminent Pioneers and Also of Prominent Citizens of Today". Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company. (1891) pp. 214–221

Judah returned to California in 1860. He continued to search for a more practical route through the Sierra suitable for a railroad. In mid-1860, local miner Daniel Strong had surveyed a route over the Sierra for a wagon toll road, which he realized would also suit a railroad. He described his discovery in a letter to Judah. Also in 1860, Charles Marsh, a surveyor, civil engineer and water company owner, met with civil engineer Judah. Marsh, who had already surveyed a potential railroad route between Sacramento and Nevada City, California, a decade earlier, went with Judah into the Sierra Nevada Mountains. There they examined the Henness Pass Turnpike Company's route (Marsh was a founding director of that company). They measured elevations and distances and discussed the possibility of a transcontinental railroad. Both were convinced that it could be done. Judah, Marsh and Strong then met with merchants and businessmen to solicit investors in their proposed railroad.

From January or February 1861 until July, Judah and Strong led a 10-person expedition to survey the route for the railroad over the Sierra Nevada through Clipper Gap and Emigrant Gap, over Donner Pass, and south to Truckee. They discovered a way across the Sierras that was gradual enough to be made suitable for a railroad, although it still needed a lot of work.

The Big Four

Four northern California businessmen formed the Central Pacific Railroad:

Four northern California businessmen formed the Central Pacific Railroad: Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American attorney, industrialist, philanthropist, and Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician from Watervliet, New York. He served as the eighth governor of Calif ...

, (1824–1893), President; Collis Potter Huntington, (1821–1900), Vice President; Mark Hopkins, (1813–1878), Treasurer; Charles Crocker, (1822–1888), Construction Supervisor. All became substantially wealthy from their association with the railroad. Judah, Marsh, Strong, Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins and Crocker, along with James Bailey and Lucius Anson Booth, became the first board of directors of the Central Pacific Railroad.

Thomas Durant

Former ophthalmologist Dr. Thomas Clark "Doc" Durant was nominally only a vice president of Union Pacific, so he installed a series of respected men like John Adams Dix as president of the railroad. While serving as vice president of Union Pacific he would be a key figure in the Crédit Mobilier scandal which ultimately led to his removal from the company.Grenville M. Dodge

Major General Grenville M. Dodge served as the chief engineer ofUnion Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United States after BNSF, ...

during the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. In 1865 while fighting against Native-American tribes he would discover a pass in the Laramie Mountains, which would serve as a vital passage for the First Transcontinental Railroad. Dodge would serve in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

for Iowa's 5th District from 1867 until 1869. During this time he would push for legislation to help the construction of the railroad.

Authorization and funding

In February 1860, Iowa Representative Samuel Curtis introduced a bill to fund the railroad. It passed theHouse

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

but died when it could not be reconciled with the Senate version because of opposition from southern states who wanted a southern route near the 42nd parallel. Curtis tried and failed again in 1861. After the southern states seceded from the Union, the House of Representatives approved the bill on May 6, 1862, and the Senate on June 20. Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 into law on July 1. It authorized creation of two companies, the Central Pacific in the west and the Union Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United States after BNSF, ...

in the mid-west, to build the railroad. The legislation called for building and operating a new railroad from the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa, west to Sacramento, California

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of California and the county seat, seat of Sacramento County, California, Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento Rive ...

, and on to San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

. Another act to supplement the first was passed in 1864. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1863 established the standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), international gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge in Europe, and SGR in East Africa. It is the ...

to be used in these federally financed railways.

Federal financing

To finance the project, the act authorized the federal government to issue 30-year U.S.government bond

A government bond or sovereign bond is a form of Bond (finance), bond issued by a government to support government spending, public spending. It generally includes a commitment to pay periodic interest, called Coupon (finance), coupon payments' ...

s (at 6% interest). The railroad companies were paid $16,000 per mile (approximately $ per mile today) for track laid on a level grade, $32,000 per mile (about $ per mile today) for track laid in foothills, and $48,000 per mile (or about $ per mile today) for track laid in mountains. The two railroad companies sold similar amounts of company-backed bonds and stock.

Union Pacific financing

While the federal legislation for the Union Pacific required that no partner was to own more than 10 percent of the stock, the Union Pacific had problems selling its stock. One of the few subscribers wasthe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, denomination and the ...

leader Brigham Young

Brigham Young ( ; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1847 until h ...

, who also supplied crews for building much of the railroad through Utah.

Durant manipulated market prices on his stocks by spreading rumors about which railroads he had an interest in were being considered for connection with the Union Pacific. First he touted rumors that his fledgling M&M Railroad had a deal in the works, while secretly buying stock in the depressed Cedar Rapids and Missouri Railroad. Then he circulated rumors that the CR&M had plans to connect to the Union Pacific, at which point he began buying back the M&M stock at depressed prices. It is estimated his scams produced over $5 million in profits for him and his cohorts.

Central Pacific financing

Collis Huntington, a Sacramento hardware merchant, heard Judah's presentation about the railroad at the St. Charles Hotel in November 1860. He invited Judah to his office to hear his proposal in detail. Huntington persuaded Judah to accept financing from himself and four others: Mark Hopkins, his business partner; James Bailey, a jeweler;Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American attorney, industrialist, philanthropist, and Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician from Watervliet, New York. He served as the eighth governor of Calif ...

, a grocer; and Charles Crocker, a dry-goods merchant. They initially invested $1,500 each and formed a board of directors. These investors became known as The Big Four, and their railroad was called the Central Pacific Railroad. Each eventually made millions of dollars from their investments and control of the Central Pacific Railroad.

Before major construction could begin, Judah traveled back to New York City to raise funds to buy out The Big Four. Shortly after arriving in New York, Judah died on November 2, 1863, of yellow fever that he had contracted while traveling over the Panama Railroad's transit of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

. The CPRR Engineering Department was taken over by his successor Samuel S. Montegue, as well as Canadian trained Chief Assistant Engineer (later Acting Chief Engineer) Lewis Metzler Clement who also became Superintendent of Track.

Land grants

To allow the companies to raise additional capital, Congress granted the railroads a right-of-way corridor, lands for additional facilities like sidings and maintenance yards. They were also granted alternate sections of government-owned lands— per mile (1.6 km)—for on both sides of the track, forming a checkerboard pattern. The railroad companies were given the odd-numbered sections while the federal government retained the even-numbered sections. The exception was in cities, at rivers, or on non-government property. The railroads sold bonds based on the value of the lands, and in areas with good land like the Sacramento Valley and Nebraska sold the land to settlers, contributing to a rapid settlement of the West. The total area of the land grants to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific was larger than the area of the state of Texas: federal government land grants totaled about 130,000,000 acres, and state government land grants totaled about 50,000,000 acres. It was far from a given that the railroads operating in the thinly-settled west would make enough money to repay their construction and operation. If the railroad companies failed to sell the land granted them within three years, they were required to sell it at prevailing government price for homesteads: . If they failed to repay the bonds, all remaining railroad property, including trains and tracks, would revert to the U.S. government. To encourage settlement in the west,Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

(1861–1863) passed the Homestead Acts which granted an applicant of land with the requirement that the applicant improve the land. This incentive encouraged thousands of settlers to move west.

In return for the land grants, the railroads were required to haul government personnel and cargo at significantly reduced rates (generally half of the normal rate). In addition, the land was granted in a checkerboard fashion, with the government retaining every other section. The land that the government retained typically doubled in value as a result of the railroad being built. The land grants were a good deal for the government.

The government guaranteed loans to several Pacific railroads, which were all paid off by 1899 ($63 million in principal, and $105 million in interest). After receiving rate discounts of approximately 50% on government personnel and cargo for 80 years (including during two world wars), Congress finally discontinued the rate reductions at the end of World War II. The land grants had been more than paid for (several times over).

Railroad self-dealing

The federal legislation lacked adequate oversight and accountability. The two companies took advantage of these weaknesses in the legislation to manipulate the project and produce extra profit for themselves. Despite the generous subsidies offered by the federal government, the railroad capitalists knew they would not turn a profit on the railroad business for many months, possibly years. They determined to make a profit on the construction itself. Both groups of financiers formed independent companies to complete the project, and they controlled management of the new companies along with the railroad ventures. This self-dealing allowed them to build in generous profit margins paid out by the railroad companies. In the west, the four men heading the Central Pacific chose a simple name for their company, the "Contract and Finance Company." In the east, the Union Pacific selected a foreign name, calling their construction firm "Crédit Mobilier of America." The latter company was later implicated in a far-reaching scandal which would greatly affect the railroad's purpose, described later. Also, the lack of federal oversight provided both companies with incentives to continue building their railroads past one other, since they were each being paid, and receiving land grants, based on how many miles of track they laid, even though only one track would eventually be used. This tacitly-agreed profiteering activity was captured (probably accidentally) by Union Pacific photographer Andrew J. Russell in his images of the Promontory Trestle construction.Labor and wages

Many of thecivil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing i ...

s and surveyors who were hired by the Union Pacific had been employed during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

to repair and operate the over of railroad line the U.S. Military Railroad controlled by the end of the war. The Union Pacific also utilized their experience repairing and building truss bridge

A truss bridge is a bridge whose load-bearing superstructure is composed of a truss, a structure of connected elements, usually forming triangular units. The connected elements, typically straight, may be stressed from tension, compression, or ...

s during the war. Most of the semi-skilled workers on the Union Pacific were recruited from the many soldiers discharged from the Union and Confederate armies along with emigrant Irishmen.

After 1864, the Central Pacific Railroad received the same Federal financial incentives as the Union Pacific Railroad, along with some construction bonds granted by the state of California and the city of San Francisco. The Central Pacific hired some Canadian and European civil engineers and surveyors with extensive experience building railroads, but it had a difficult time finding semi-skilled labor. Most Caucasians in California preferred to work in the mines or agriculture. The railroad experimented by hiring local emigrant Chinese as manual laborers, many of whom were escaping the poverty and terrors of the war (especially the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars) in the Sze Yup districts in the

After 1864, the Central Pacific Railroad received the same Federal financial incentives as the Union Pacific Railroad, along with some construction bonds granted by the state of California and the city of San Francisco. The Central Pacific hired some Canadian and European civil engineers and surveyors with extensive experience building railroads, but it had a difficult time finding semi-skilled labor. Most Caucasians in California preferred to work in the mines or agriculture. The railroad experimented by hiring local emigrant Chinese as manual laborers, many of whom were escaping the poverty and terrors of the war (especially the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars) in the Sze Yup districts in the Pearl River Delta

The Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region is the low-lying area surrounding the Pearl River estuary, where the Pearl River flows into the South China Sea. Referred to as the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area in official documents, ...

of Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

province in China. When they proved themselves as workers, the CPRR from that point forward preferred to hire Chinese, and even set up recruiting efforts in Canton. Despite their small stature and lack of experience, the Chinese laborers were responsible for most of the heavy manual labor since only a very limited amount of that work could be done by animals, simple machines, or black powder. The railroad also hired some black people

Black is a racial classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin and often additional phenotypical ...

escaping the aftermath of the American Civil War. Most of the black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

and white workers were paid $30 per month and given food and lodging. Most Chinese were initially paid $31 per month and provided lodging, but they preferred to cook their own meals. In 1867 the CPRR raised their wage to $35 (equivalent to $ in ) per month after a strike. CPRR came to see the advantage of good workers employed at low wages: "Chinese labor proved to be Central Pacific's salvation."

Transcontinental route

Construction begun

The Central Pacific broke ground on January 8, 1863. Because of insufficient transportation alternatives from the manufacturing centers on the east coast, virtually all of their tools and machinery including rails, railroad switches, railroad turntables,freight

In transportation, cargo refers to goods transported by land, water or air, while freight refers to its conveyance. In economics, freight refers to goods transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. The term cargo is also used in ...

and passenger cars, and steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

s were transported first by train to east coast ports. They were then loaded on ships which either sailed around South America's Cape Horn, or offloaded the cargo at the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

, where it was sent across via paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine driving paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, whereby the first uses were wh ...

and the Panama Railroad. The Panama Railroad gauge was , which was incompatible with the gauge used by the CPRR equipment. The latter route was about twice as expensive per pound. Once the machinery and tools reached the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

area, they were put aboard river paddle steamers which transported them up the final of the Sacramento River to the new state capital in Sacramento