First Intermediate Period Of Egypt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history, spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the

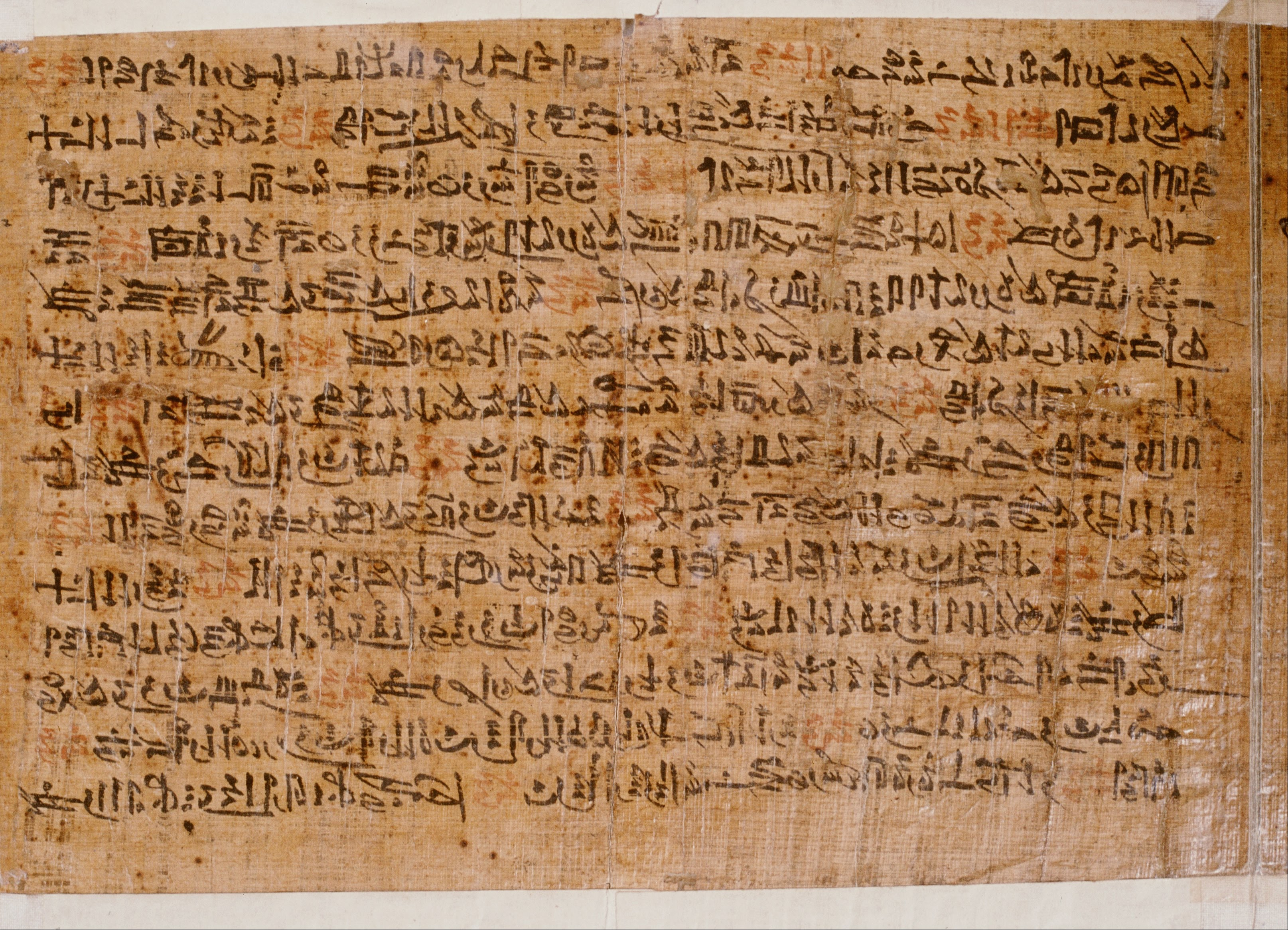

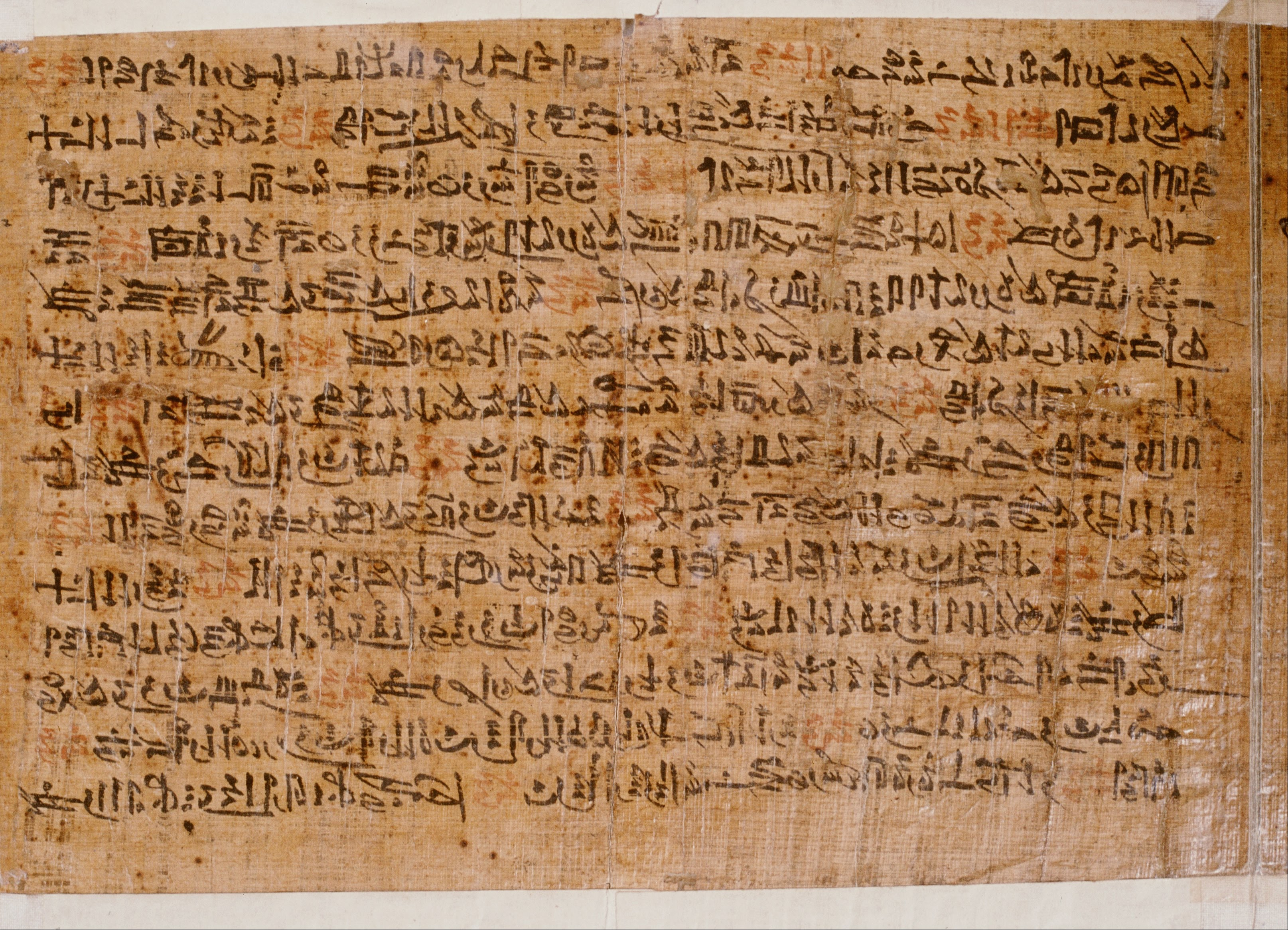

The emergence of what is considered literature by modern standards seems to have occurred during the First Intermediate Period, with a flowering of new literary genres in the Middle Kingdom. A particularly important piece is the Ipuwer Papyrus, often called the ''Lamentations'' or ''Admonitions of Ipuwer'', which although not dated to this period by modern scholarship may refer to the First Intermediate Period and record a decline in international relations and a general impoverishment in Egypt.

The emergence of what is considered literature by modern standards seems to have occurred during the First Intermediate Period, with a flowering of new literary genres in the Middle Kingdom. A particularly important piece is the Ipuwer Papyrus, often called the ''Lamentations'' or ''Admonitions of Ipuwer'', which although not dated to this period by modern scholarship may refer to the First Intermediate Period and record a decline in international relations and a general impoverishment in Egypt.

An example of Pre-Unification Theban reliefs is the Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati, a limestone stela from the reign of Mentuhotep II, ca. 2051-2030 BCE. In this stela, Maati is seated at an offering table with a jar of sacred oils in his left hand, and the text surrounding him references other figures from his life, such as the treasurer Bebi and the ancestor of the ruling Intef family, demonstrating the close bonds that tie together rulers and followers in Theban society during the First Intermediate Period.

Strong facial features and the round modeling of limbs is also seen in statues, as seen in the ''Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery,'' from the 11th Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period, also under the reign of Mentuhotep II.

Males with pronounced, angular breasts portrayed with rolls of fat, as well as females with angular or pointed breasts are seen in the collection of ''Limestone Reliefs of High Official Tjetji.'' The ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji'' contains 14 horizontal lines of text at the top of the relief, with an account of Tjetji's life. Five vertical columns on the right of the relief dictate an elaborate offering formula particular to the First Intermediate Period. Tjetji faces right with two smaller males on the left that are most likely official staff. Tjetji himself is depicted as a mature official with a pronounced breast, rolls of fat on his torso, and a calf-length kilt. The officials shown on the left are more youthful and wear shorter kilts, symbolizing that they are less mature and active. The depiction of the female figure specific to the First Intermediate Period is also seen in the ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji;'' in the image provided, the angular breast can be seen.

The building projects of the Heracleopolitan kings in the North were very limited. Only one pyramid believed to belong to King Merikare (2065–2045 BC) is mentioned to be somewhere at

An example of Pre-Unification Theban reliefs is the Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati, a limestone stela from the reign of Mentuhotep II, ca. 2051-2030 BCE. In this stela, Maati is seated at an offering table with a jar of sacred oils in his left hand, and the text surrounding him references other figures from his life, such as the treasurer Bebi and the ancestor of the ruling Intef family, demonstrating the close bonds that tie together rulers and followers in Theban society during the First Intermediate Period.

Strong facial features and the round modeling of limbs is also seen in statues, as seen in the ''Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery,'' from the 11th Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period, also under the reign of Mentuhotep II.

Males with pronounced, angular breasts portrayed with rolls of fat, as well as females with angular or pointed breasts are seen in the collection of ''Limestone Reliefs of High Official Tjetji.'' The ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji'' contains 14 horizontal lines of text at the top of the relief, with an account of Tjetji's life. Five vertical columns on the right of the relief dictate an elaborate offering formula particular to the First Intermediate Period. Tjetji faces right with two smaller males on the left that are most likely official staff. Tjetji himself is depicted as a mature official with a pronounced breast, rolls of fat on his torso, and a calf-length kilt. The officials shown on the left are more youthful and wear shorter kilts, symbolizing that they are less mature and active. The depiction of the female figure specific to the First Intermediate Period is also seen in the ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji;'' in the image provided, the angular breast can be seen.

The building projects of the Heracleopolitan kings in the North were very limited. Only one pyramid believed to belong to King Merikare (2065–2045 BC) is mentioned to be somewhere at

File:Limestone_Statue_of_the_Steward_Mery.jpg, Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery

File:Limestone_Stela_of_Tjetji.jpg, Limestone Stela of Tjetji

File:Limestone_Stela_Featuring_Woman.jpg, Limestone Stela Featuring Woman

Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

. It comprises the Seventh (although this is mostly considered spurious by Egyptologists), Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and part of the Eleventh Dynasties. The concept of a "First Intermediate Period" was coined in 1926 by Egyptologists Georg Steindorff and Henri Frankfort.

Very little monumental evidence survives from this period, especially from the beginning of the era. The First Intermediate Period was a dynamic time in which rule of Egypt was roughly equally divided between two competing power bases. One of the bases was at Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically ...

, a city just south of the Faiyum region, and the other was at Thebes, in Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend wikt:downriver, upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south. ...

. It is believed that during that time, temples were pillaged and violated, artwork was vandalized, and the statues of kings were broken or destroyed as a result of the postulated political chaos. The two kingdoms would eventually come into conflict, which would lead to the conquest of the north by the Theban kings and to the reunification of Egypt under a single ruler, Mentuhotep II, during the second part of the Eleventh Dynasty. This event marked the beginning of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

History

Events leading to the First Intermediate Period

The fall of theOld Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

is often described as a period of chaos and disorder by some literature in the First Intermediate Period, but mostly by the literature of successive eras of ancient Egyptian history. The causes that brought about the downfall of the Old Kingdom are numerous, but some are merely hypothetical. One reason that is often quoted is the extremely long reign of Pepi II, the last major pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

of the 6th Dynasty. He ruled from his childhood until he was very elderly, possibly in his 90s, but the length of his reign is uncertain. He outlived many of his anticipated heirs, thereby creating problems with succession. Thus, the regime of the Old Kingdom disintegrated amidst this disorganization. Another major problem was the rise in power of the provincial nomarchs. Towards the end of the Old Kingdom the positions of the nomarchs had become hereditary, so families often held onto the position of power in their respective provinces. As these nomarchs grew increasingly powerful and influential, they became more independent from the king. They erected tombs in their own domains and often raised armies. The rise of these numerous nomarchs inevitably created conflicts between neighboring provinces, often resulting in intense rivalries and warfare between them. A third reason for the dissolution of centralized kingship that is mentioned was the low levels of the Nile inundation which may have been caused by a drier climate, resulting in lower crop yields bringing about famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accom ...

across ancient Egypt; see 4.2 kiloyear event

The 4.2-kiloyear (thousand years) BP aridification event (long-term drought) was one of the most severe climatic events of the Holocene epoch. It defines the beginning of the current Meghalayan age in the Holocene epoch.

Starting around 220 ...

. There is however no consensus on this subject. According to Manning, there is no relationship with low Nile floods.

"State collapse was complicated, but unrelated to Nile flooding history."

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties at Memphis

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties are often overlooked because very little is known about the rulers of these two periods. Manetho, a historian and priest from the Ptolemaic era, describes 70 kings who ruled for 70 days.Sir Alan Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 107. This is almost certainly an exaggeration meant to describe the disorganization of the kingship during this time period. The Seventh Dynasty may have been an oligarchy comprising powerful officials of the Sixth Dynasty based in Memphis who attempted to retain control of the country. The Eighth dynasty rulers, claiming to be the descendants of the Sixth Dynasty kings, also ruled from Memphis. Little is known about these two dynasties since very little textual or architectural evidence survives to describe the period. However, a few artifacts have been found, including scarabs that have been attributed to kingNeferkare II

Neferkare II was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Eighth Dynasty during the early First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BC). According to the Egyptologists Kim Ryholt, Jürgen von Beckerath and Darell Baker he was the third king of the Eighth ...

of the Seventh Dynasty, as well as a green jasper cylinder of Syrian influence which has been credited to the Eighth Dynasty. Also, a small pyramid believed to have been constructed by King Ibi

Ibi or IBI may refer to:

Companies

* IBI Group, a Canadian-based architecture, engineering, planning, and technology firm

Places

* Ibi, Nigeria, a town and administrative district in Taraba State, central Nigeria

* Ibi, Spain, a town in the pr ...

of the Eighth Dynasty has been identified at Saqqara

Saqqara ( ar, سقارة, ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphi ...

. Several kings, such as Iytjenu, are only attested once and their position remains unknown.

Rise of the Heracleopolitan kings

Sometime after the obscure reign of the Seventh and Eighth Dynasty kings a group of rulers arose in Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt. These kings comprise the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, each with nineteen listed rulers. The Heracleopolitan kings are conjectured to have overwhelmed the weak Memphite rulers to create the Ninth Dynasty, but there is virtually no archaeology elucidating the transition, which seems to have involved a drastic reduction in population in the Nile Valley. The founder of the Ninth Dynasty, Akhthoes or Akhtoy, is often described as an evil and violent ruler, most notably in Manetho's writing. Possibly the same as Wahkare Khety I, Akhthoes was described as a king who caused much harm to the inhabitants of Egypt, was seized with madness, and was eventually killed by a crocodile.James Henry Breasted, Ph.D., A History of the Ancient Egyptians (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1923), 134. This may have been a fanciful tale, but Wahkare is listed as a king in the Turin Canon. Kheti I was succeeded by Kheti II, also known as Meryibre. Little is certain of his reign, but a few artifacts bearing his name survive. It may have been his successor,Kheti III

The ''Teaching for King Merykara'', alt. ''Instruction Addressed to King Merikare'', is a literary composition in Middle Egyptian, the classical phase of the Egyptian language, probably of Middle Kingdom date (2025–1700 BC).

In this ''sebayt'' ...

, who would bring some degree of order to the Delta, though the power and influence of these Ninth Dynasty kings was seemingly insignificant compared to the Old Kingdom pharaohs.

A distinguished line of nomarchs arose in Siut

AsyutAlso spelled ''Assiout'' or ''Assiut'' ( ar, أسيوط ' , from ' ) is the capital of the modern Asyut Governorate in Egypt. It was built close to the ancient city of the same name, which is situated nearby. The modern city is located at , ...

(or Asyut), a powerful and wealthy province in the south of the Heracleopolitan kingdom. These warrior princes maintained a close relationship with the kings of the Heracleopolitan royal household, as evidenced by the inscriptions in their tombs. These inscriptions provide a glimpse at the political situation that was present during their reigns. They describe the Siut nomarchs digging canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface fl ...

s, reducing taxation

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, o ...

, reaping rich harvests, raising cattle herds, and maintaining an army and fleet. The Siut province acted as a buffer state between the northern and southern rulers, and the Siut princes would bear the brunt of the attacks from the Theban kings.

Ankhtifi

The South was dominated by warlords, the best-known of whom is Ankhtifi, whose tomb was discovered in 1928 at Mo’alla, 30 km south of Luxor. He was a nomarch or provincial governor of the nome based at Hierakonpolis, but he then expanded to the south and conquered a second nome centred on Edfu. He then tried to expand to the north to conquer the nome centred on Thebes, but was unsuccessful, as they refused to come out and fight. His tomb is highly decorated and contains an extremely informative autobiography in which he paints a picture of Egypt riven by hunger and famine from which he, the great Ankhtifi, had rescued them. ‘I gave bread to the hungry and did not allow anyone to die’. This economic disaster is much debated by modern commentators: it seems that every ruler made similar claims. But it seems clear that for all practical purposes, Ankhtifi was the ruler and there was no higher power to whom he owed allegiance. The unity of Egypt had broken down.Rise of the Theban kings

It has been suggested that an invasion of Upper Egypt occurred contemporaneously with the founding of the Heracleopolitan kingdom, which would establish the Theban line of kings, constituting the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties. This line of kings is believed to have been descendants of Intef, who was the nomarch of Thebes, often called the "keeper of the Door of the South". He is credited for organizing Upper Egypt into an independent ruling body in the south, although he himself did not appear to have tried to claim the title of king. However, his successors in the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties would later do so for him. One of them, Intef II, begins the assault on the north, particularly atAbydos Abydos may refer to:

*Abydos, a progressive metal side project of German singer Andy Kuntz

* Abydos (Hellespont), an ancient city in Mysia, Asia Minor

* Abydos (''Stargate''), name of a fictional planet in the '' Stargate'' science fiction universe ...

.

By around 2060 BC, Intef II had defeated the governor of Nekhen, allowing further expansion south, toward Elephantine. His successor, Intef III

Intef III was the third pharaoh of the Eleventh Dynasty of Egypt during the late First Intermediate Period in the 21st century BC, at a time when Egypt was divided in two kingdoms. The son of his predecessor Intef II and father of his successo ...

, completed the conquest of Abydos, moving into Middle Egypt against the Heracleopolitan kings.James Henry Breasted, Ph.D., A History of the Ancient Egyptians (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1923), 136. The first three kings of the Eleventh Dynasty (all named Intef) were, therefore, also the last three kings of the First Intermediate Period and would be succeeded by a line of kings who were all called Mentuhotep Mentuhotep (also Montuhotep) is an ancient Egyptian name meaning "'' Montu is satisfied''" and may refer to:

Kings

* Mentuhotep I, nomarch at Thebes during the First Intermediate Period and first king of the 11th Dynasty

* Mentuhotep II, reuni ...

. Mentuhotep II, also known as Nebhepetra, would eventually defeat the Heracleopolitan kings around 2033 BC and unify the country to continue the Eleventh Dynasty, bringing Egypt into the Middle Kingdom.

The Ipuwer Papyrus

The emergence of what is considered literature by modern standards seems to have occurred during the First Intermediate Period, with a flowering of new literary genres in the Middle Kingdom. A particularly important piece is the Ipuwer Papyrus, often called the ''Lamentations'' or ''Admonitions of Ipuwer'', which although not dated to this period by modern scholarship may refer to the First Intermediate Period and record a decline in international relations and a general impoverishment in Egypt.

The emergence of what is considered literature by modern standards seems to have occurred during the First Intermediate Period, with a flowering of new literary genres in the Middle Kingdom. A particularly important piece is the Ipuwer Papyrus, often called the ''Lamentations'' or ''Admonitions of Ipuwer'', which although not dated to this period by modern scholarship may refer to the First Intermediate Period and record a decline in international relations and a general impoverishment in Egypt.

The art and architecture of the First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period in Egypt was generally divided into two main geographical and political regions, one centered at Memphis and the other at Thebes. The Memphite kings, although weak in power, held on to the Memphite artistic traditions that had been in place throughout the Old Kingdom. This was a symbolic way for the weakened Memphite state to hold on to the vestiges of glory in which the Old Kingdom had reveled. On the other hand, the Theban kings, physically isolated from Memphis (the capital of Egypt in the Old Kingdom) and the Memphite center of art, were forced to develop their own "Pre-Unification Theban Style" of art to fulfill their kingly duty of creating order out of chaos through art. There is not much known about the style of art from the North (centered in Heracleopolis) because not much is known about the Heracleopolitan kings: little information is provided detailing their rule on monuments from the North. However, much is known about the Pre-Unification Theban Style, as the Theban kings of the Pre-Unification Eleventh Dynasty used art to reinforce the legitimacy of their rule, and many royal workshops were created, forming a distinctive Upper Egyptian style of art different from the Old Kingdom canon. Reliefs from the Pre-Unification Theban style of art consist primarily of either high raised relief or deep sunk relief with incised details. Figures depicted have narrow shoulders and a high small of the back, with rounded limbs and a lack of musculature in males; males also sometimes are shown with rolls of fat (a characteristic that originated in the Old Kingdom to portray mature males) and have angular breasts and, while the female breast is more angular or pointed or is shown through a long gentle curve with no nipple (in other periods, the female breast is depicted as curved). Facial features characteristic of this style include a large eye, which is outlined with a band of relief meant to represent eye paint. The band meets the outer eye corner and this line usually runs back to the ear. The eyebrow above the eye is mostly flat; it does not mimic the shape of the eyelid. A deep incision is used in the creation of the broad nose, and the ear is both large and oblique. An example of Pre-Unification Theban reliefs is the Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati, a limestone stela from the reign of Mentuhotep II, ca. 2051-2030 BCE. In this stela, Maati is seated at an offering table with a jar of sacred oils in his left hand, and the text surrounding him references other figures from his life, such as the treasurer Bebi and the ancestor of the ruling Intef family, demonstrating the close bonds that tie together rulers and followers in Theban society during the First Intermediate Period.

Strong facial features and the round modeling of limbs is also seen in statues, as seen in the ''Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery,'' from the 11th Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period, also under the reign of Mentuhotep II.

Males with pronounced, angular breasts portrayed with rolls of fat, as well as females with angular or pointed breasts are seen in the collection of ''Limestone Reliefs of High Official Tjetji.'' The ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji'' contains 14 horizontal lines of text at the top of the relief, with an account of Tjetji's life. Five vertical columns on the right of the relief dictate an elaborate offering formula particular to the First Intermediate Period. Tjetji faces right with two smaller males on the left that are most likely official staff. Tjetji himself is depicted as a mature official with a pronounced breast, rolls of fat on his torso, and a calf-length kilt. The officials shown on the left are more youthful and wear shorter kilts, symbolizing that they are less mature and active. The depiction of the female figure specific to the First Intermediate Period is also seen in the ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji;'' in the image provided, the angular breast can be seen.

The building projects of the Heracleopolitan kings in the North were very limited. Only one pyramid believed to belong to King Merikare (2065–2045 BC) is mentioned to be somewhere at

An example of Pre-Unification Theban reliefs is the Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati, a limestone stela from the reign of Mentuhotep II, ca. 2051-2030 BCE. In this stela, Maati is seated at an offering table with a jar of sacred oils in his left hand, and the text surrounding him references other figures from his life, such as the treasurer Bebi and the ancestor of the ruling Intef family, demonstrating the close bonds that tie together rulers and followers in Theban society during the First Intermediate Period.

Strong facial features and the round modeling of limbs is also seen in statues, as seen in the ''Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery,'' from the 11th Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period, also under the reign of Mentuhotep II.

Males with pronounced, angular breasts portrayed with rolls of fat, as well as females with angular or pointed breasts are seen in the collection of ''Limestone Reliefs of High Official Tjetji.'' The ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji'' contains 14 horizontal lines of text at the top of the relief, with an account of Tjetji's life. Five vertical columns on the right of the relief dictate an elaborate offering formula particular to the First Intermediate Period. Tjetji faces right with two smaller males on the left that are most likely official staff. Tjetji himself is depicted as a mature official with a pronounced breast, rolls of fat on his torso, and a calf-length kilt. The officials shown on the left are more youthful and wear shorter kilts, symbolizing that they are less mature and active. The depiction of the female figure specific to the First Intermediate Period is also seen in the ''Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji;'' in the image provided, the angular breast can be seen.

The building projects of the Heracleopolitan kings in the North were very limited. Only one pyramid believed to belong to King Merikare (2065–2045 BC) is mentioned to be somewhere at Saqqara

Saqqara ( ar, سقارة, ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphi ...

. Also, private tombs that were built during the time pale in comparison to the Old Kingdom monuments, in quality and size. There are still relief scenes of servants making provisions for the deceased as well as the traditional offering scenes which mirror those of the Old Kingdom Memphite tombs. However, they are of a lower quality and are much simpler than their Old Kingdom parallels. Wooden rectangular coffins were still being used, but their decorations became more elaborate during the rule of the Heracleopolitan kings. New Coffin Texts were painted on the interiors, providing spells and maps for the deceased to use in the afterlife.

Artworks that survived from the Theban Period show that the artisans took on new interpretations of traditional scenes. They employed the use of bright colors in their paintings and changed and distorted the proportions of the human figure. This distinctive style was especially evident in the rectangular slab stelae found in the tombs at Naga el-Deir

Naga or NAGA may refer to:

Mythology

* Nāga, a serpentine deity or race in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain traditions

* Naga Kingdom, in the epic ''Mahabharata''

* Phaya Naga, mythical creatures believed to live in the Laotian stretch of the Mekong Ri ...

. In terms of royal architecture, the Theban kings of the early eleventh dynasty constructed rock cut tombs called saff tombs at El-Tarif on the west bank of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. This new style of mortuary architecture consisted of a large courtyard with a rock-cut colonnade at the far wall. Rooms were carved into the walls facing the central courtyard where the deceased were buried, allowing for multiple people to be buried in one tomb.Jaromir Malek, Egyptian Art (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999), 162. The undecorated burial chambers may have been due to the lack of skilled artists in the Theban kingdom.

References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:First Intermediate Period Of Egypt Dynasties of ancient Egypt States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC States and territories disestablished in the 3rd millennium BC