Fiona Pinnata on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Fiona pinnata'', common name Fiona, is a

PDF

/ref> the similar-looking oral tentacles and

Sea Slug Forum. Retrieved 17 December 2009. The type locality is the island location of

Malacolog Version 4.1.1. A Database of Western Atlantic Marine Mollusca. Retrieved 17 December 2009. Dimensions of a specimen with a total length of 31.7 mm are as follows: 17.7 mm is the body to the tip of cerata, the length of the foot is 14.4 mm, the tail at the end of the foot is 14 mm. The colour of the head and body ranges from white to brown or purple depending on its food. The foot is long and lanceolate, rounded in front and produced into a fine point behind. The margin of the foot is thin, fringed and crumpled, except near the head, where it is simple. It is divided in front, but not produced into propodial tentacles. The

354

358. 546 pp

Plate 68

figures 23-28

Plate 70

figures 11-12. The mouth is situated on the inferior surface of the head. The mouth is small and the external lip is divided behind on the median line. The anus is between the cerata on the right side of the body, and its opening is directing dorsally. The genital opening is separate.

page 357

.

The

The

"A List of the Worldwide Food Habits of Nudibranchs"

. Accessed 20 December 2009

(see also Beeman & Williams 1980) and

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 8.png, Drawing of anterior view of young

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 4.png, Anterior view of well developed veliger.

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 3.png, Dorsal view of well developed veliger.

File:Fiona pinnata veliger.png, Right side of veliger just before hatching.

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 2.png, Dorsal view of veliger just before hatching.

35Plate 2

figure 2. * Williams, M . N . (1978) ''Buccal glands of some aeolid nudibranchs (Ultrastructure and histochemistry)''. Unpubl. MSc thesis, University of Auckland. 96 pp.

"Cell Lineage and Early Larval Development of ''Fiona marina'', a Nudibranch Mollusck"

''

photo 1

photo 2

{{Taxonbar , from=Q309687 Fionidae Gastropods described in 1831

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of small pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

nudibranch

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs which shed their shells after their larval stage. They are noted for their often extraordinary colours and striking forms, and they have been given colourful nicknames to matc ...

(sea slug), a marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

in the superfamily Fionoidea

Fionoidea is a superfamily of small sea slugs, aeolid nudibranchs. They are gastropod mollusks within the infraorder Cladobranchia. The families within Fionoidea were shown to be monophyletic on DNA evidence and a re-interpretation of family char ...

. This nudibranch species lives worldwide on floating objects on seas, and feeds mainly on barnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in eros ...

s, specifically goose barnacles

Goose barnacles, also called stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerly made up the taxonomic order Pe ...

in the genus ''Lepas

''Lepas'' is a genus of goose barnacles in the family Lepadidae.

Species

Species in the genus include:

* '' Lepas anatifera'' Linnaeus, 1758

* ''Lepas anserifera'' Linnaeus, 1767

* '' Lepas australis'' Darwin, 1851

* ''Lepas hilli

''Lepas'' ...

''.

The anatomy of this species is very unusual. It is currently the only named member of the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

''Fiona'' but a 2016 study showed that this species is a species complex

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

. The family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Fionidae was expanded in 2016 to include Tergipedidae, Eubranchidae

Eubranchidae is a taxonomic family of sea slugs, marine gastropod molluscs in the superfamily Aeolidioidea, the aeolid nudibranch

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs which shed their shells after their larval ...

and Calmidae

Calmidae is a taxonomic family of sea slugs with only one genus and two species. These are specifically aeolid nudibranchs. They are marine gastropod molluscs in the superfamily Fionoidea.

This family has no subfamilies.

Taxonomic history ...

as a result of a molecular phylogenetics study. Features that are characteristic of the genus ''Fiona'' includeWillan R. C. (1979) "New Zealand locality records for the aeolid nudibranch ''Fiona pinnata'' (Eschscholtz)". ''Tane'' 25: /ref> the similar-looking oral tentacles and

rhinophore

A rhinophore is one of a pair of chemosensory club-shaped, rod-shaped or ear-like structures which are the most prominent part of the external head anatomy in sea slugs, marine gastropod opisthobranch mollusks such as the nudibranchs, sea har ...

s; the cerata

:''The tortrix moth genus ''Cerata'' is considered a junior synonym of ''Cydia.

Cerata, singular ceras, are anatomical structures found externally in nudibranch sea slugs, especially in aeolid nudibranchs, marine opisthobranch gastropod mollusks ...

with a membrane and lacking a cnidosac

A cnidosac is an anatomical feature that is found in the group of sea slugs known as aeolid nudibranchs, a clade of marine opisthobranch gastropod molluscs. A cnidosac contains cnidocytes, stinging cells that are also known as cnidoblasts or n ...

; a dorsal anal opening; a reproductive system

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are als ...

with two genital openings; two jaws with a cutting-edge, and a radula

The radula (, ; plural radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food ...

with only one central denticle in each row of teeth. That one denticle has a central cusp and a few surrounding cusps.

Distribution

''Fiona pinnata'' is found in all seas worldwide, on many different kinds of floating objects.''Fiona pinnata'' (Eschscholtz, 1831)Sea Slug Forum. Retrieved 17 December 2009. The type locality is the island location of

Sitka, Alaska

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

(Baranof Island

Baranof Island is an island in the northern Alexander Archipelago in the Alaska Panhandle, in Alaska. The name Baranof was given in 1805 by Imperial Russian Navy captain Yuri Lisyansky, U. F. Lisianski to honor Alexander Andreyevich Baranov. It ...

), on the extreme northwestern coast of North America.

Taxonomy

A 2016 study showed that this species is a species complex, but did not name the segregate species.Trickey, J. S., Thiel, M. & Waters, J., 2016. Transoceanic dispersal and cryptic diversity in a cosmopolitan rafting nudibranch. Invertebrate Systematics 30(3):290. DOI: 10.1071/IS15052 Various names have been created for this species. ''Limax

''Limax'' is a genus of air-breathing land slugs in the terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusk family Limacidae.

The generic name ''Limax'' literally means "slug".

Some species, such as the leopard slug (''L. maximus'') and the tawny garden ...

'' by Peter Forsskål

Peter Forsskål, sometimes spelled Pehr Forsskål, Peter Forskaol, Petrus Forskål or Pehr Forsskåhl (11 January 1732 – 11 July 1763) was a Swedish-speaking Finnish explorer, orientalist, naturalist, and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus.

Earl ...

from 1775 was preoccupied

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linn ...

by Johan Ernst Gunnerus

Johan Ernst Gunnerus (26 February 1718 – 25 September 1773) was a Norway, Norwegian bishop and botanist. Gunnerus was born at Oslo, Christiania. He was bishop of the Diocese of Nidaros from 1758 until his death and also a professor of theology ...

in 1770. Alder and Hancock's 1851 name '' Oithona'' was preoccupied by a Cyclopoid genus from W. Baird in 1843, so in 1855 they chose instead Fiona from a character in ''Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora'' (1763), and later combined under t ...

''. Harold John Finlay

Harold John Finlay (22 March 1901 – 7 April 1951) was a New Zealand palaeontologist and conchologist.

Biography

Finlay was born in Comilla, India (now Bangladesh), on 22 March 1901. He was left a paraplegic after contracting poliomyelitis at ...

proposed a new genus ''Dolicheolis'' for one of those synonyms ''Eolidia longicauda'' in 1927.

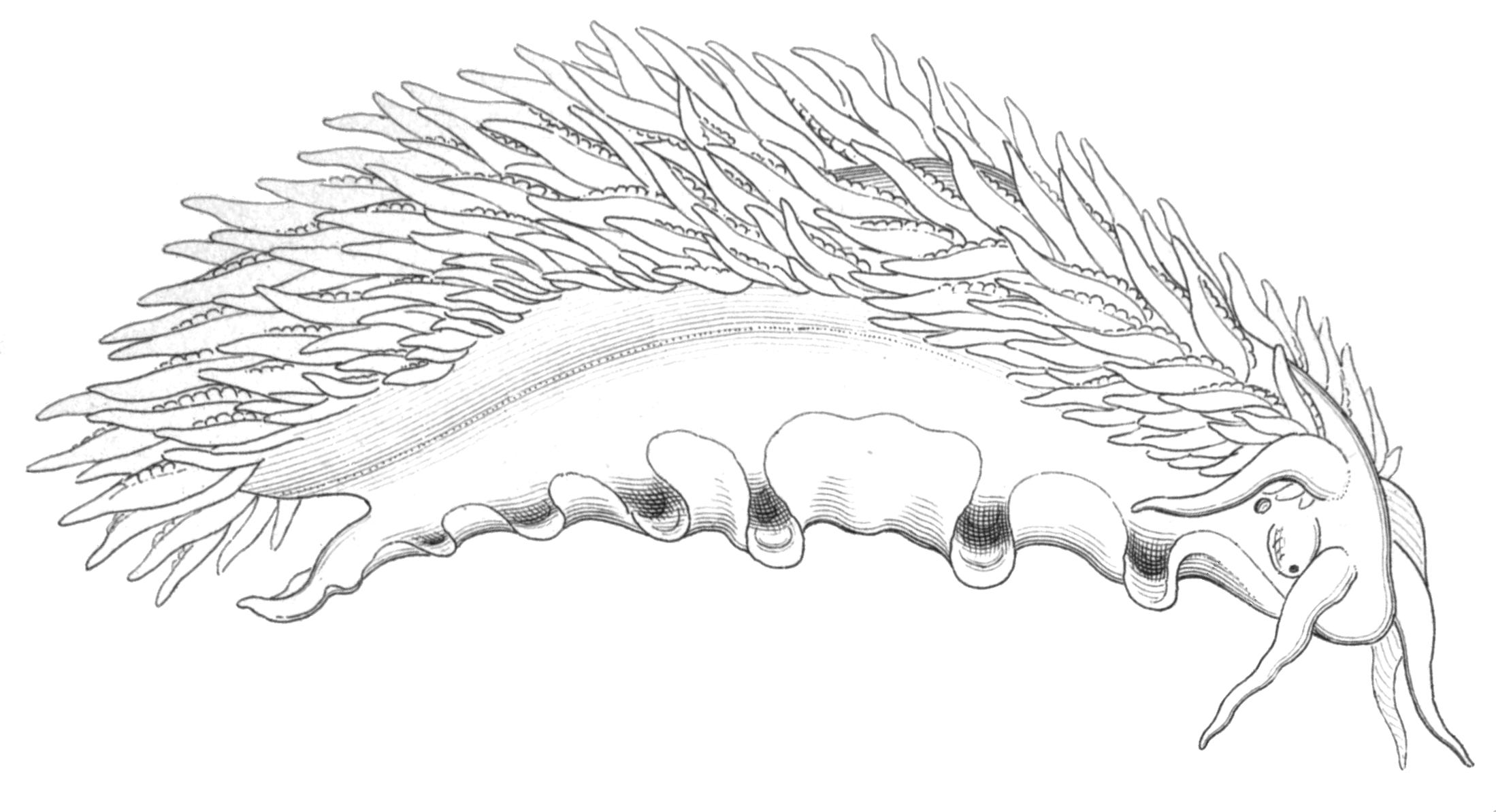

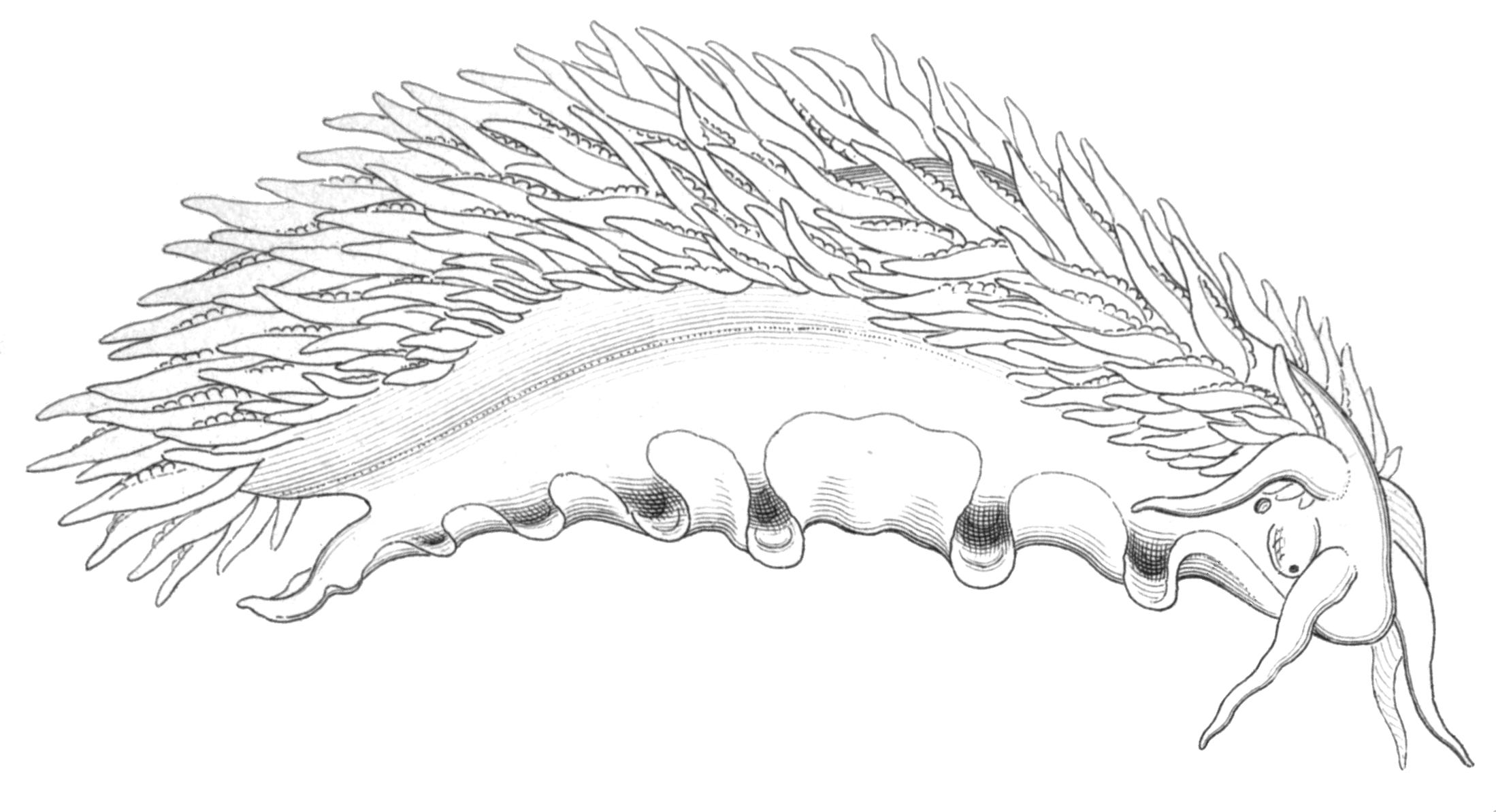

Description

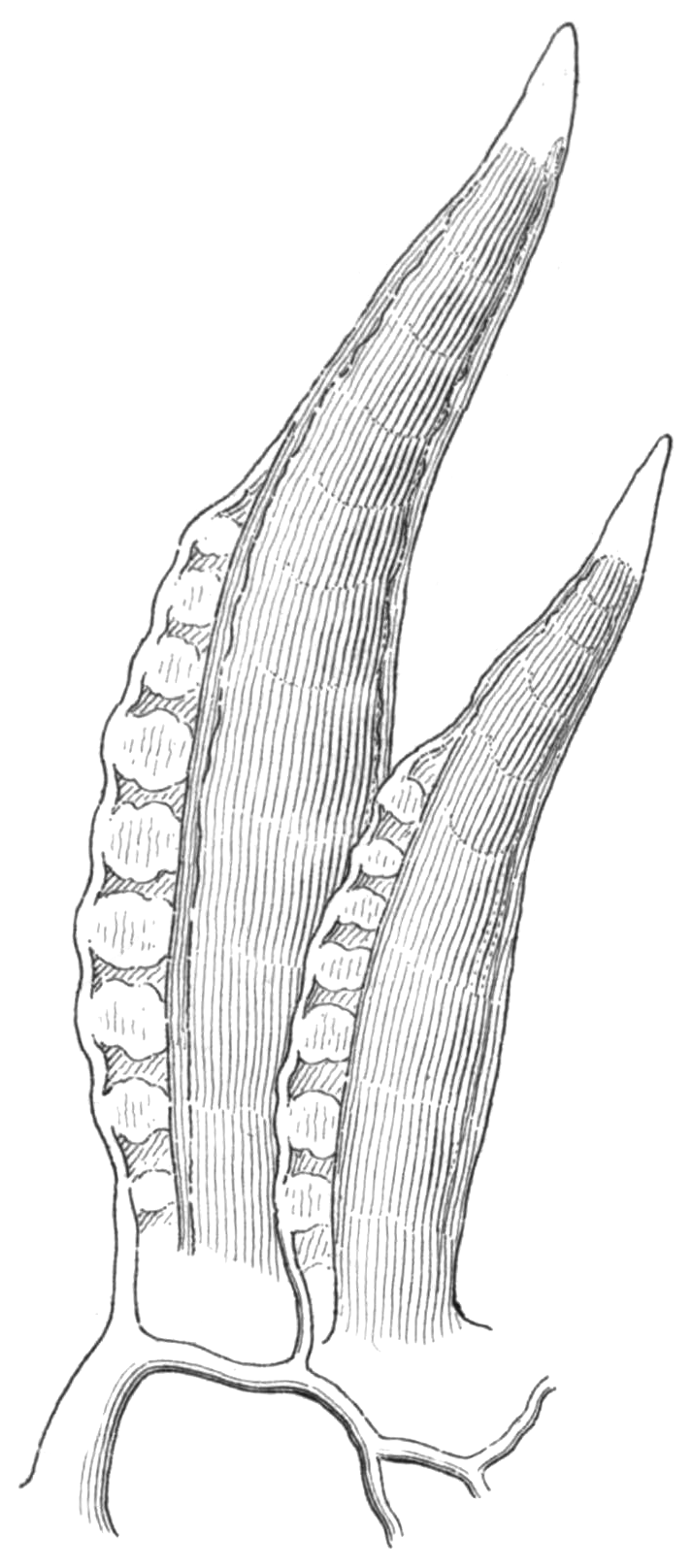

The body is elongated and oblong-elliptical. The length of the body is usually about 20 mm, but the largest reported size of the body is 50 mm.''Fiona pinnata'' (Eschscholtz, 1831)Malacolog Version 4.1.1. A Database of Western Atlantic Marine Mollusca. Retrieved 17 December 2009. Dimensions of a specimen with a total length of 31.7 mm are as follows: 17.7 mm is the body to the tip of cerata, the length of the foot is 14.4 mm, the tail at the end of the foot is 14 mm. The colour of the head and body ranges from white to brown or purple depending on its food. The foot is long and lanceolate, rounded in front and produced into a fine point behind. The margin of the foot is thin, fringed and crumpled, except near the head, where it is simple. It is divided in front, but not produced into propodial tentacles. The

cerata

:''The tortrix moth genus ''Cerata'' is considered a junior synonym of ''Cydia.

Cerata, singular ceras, are anatomical structures found externally in nudibranch sea slugs, especially in aeolid nudibranchs, marine opisthobranch gastropod mollusks ...

are numerous, elongated, with a membranous fringe on the inner sides. Cerata may seem to be without apparent order but they are set in oblique rows containing from four to six cerata. There are also small cerata near the margins of the body. Cerata on the sides of the back are dark brown, each margined with white. The cerata have no cnidosac

A cnidosac is an anatomical feature that is found in the group of sea slugs known as aeolid nudibranchs, a clade of marine opisthobranch gastropod molluscs. A cnidosac contains cnidocytes, stinging cells that are also known as cnidoblasts or n ...

s. They are particularly compressed towards the base.

''Fiona pinnata'' has no eyes.

The rhinophore

A rhinophore is one of a pair of chemosensory club-shaped, rod-shaped or ear-like structures which are the most prominent part of the external head anatomy in sea slugs, marine gastropod opisthobranch mollusks such as the nudibranchs, sea har ...

s are simple and resemble the oral tentacles. They are distant, subulate, tapering and they project outward. They are not retractile, and are without pockets.

The oral tentacles are shorter, thickened at the base, tapering, projecting laterally and horizontally and curved backward. MacFarland, F . M . (8 April 1966). "Studies of opisthobranchiate mollusks of the Pacific Coast of North America". '' Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences'' 6354

358. 546 pp

Plate 68

figures 23-28

Plate 70

figures 11-12. The mouth is situated on the inferior surface of the head. The mouth is small and the external lip is divided behind on the median line. The anus is between the cerata on the right side of the body, and its opening is directing dorsally. The genital opening is separate.

Joshua Alder

Joshua Alder (7 April 1792 – 21 January 1867) was a British cheese, cheesemonger and amateur zoologist and malacologist. As such, he specialized in the Tunicata, and in gastropods.

He was a member of the Hancock Museum, Natural History Societ ...

and Albany Hancock

Albany Hancock (24 December 1806 – 1873), English naturalist, biologist and supporter of Charles Darwin, was born on Christmas Eve in Newcastle upon Tyne. He is best known for his works on marine animals and coal-measure fossils.

Albany Hanco ...

(1851) described the tissues of ''Fiona pinnata'' as being very tough and firm.

Digestive system

Digestive system

The human digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion (the tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder). Digestion involves the breakdown of food into smaller and smaller compone ...

: The channel leading from mouth to the buccal mass is very short and constricted; and, just before it opens into the buccal mass, it receives on either side below, a very slender duct from a large, much folliculated, salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary gla ...

. These glands lie beneath the stomach and extend almost halfway down the body. That on the right side is considerably less than the other, and is somewhat tubular, — distinctly so towards its termination; the one on the left side is much complicated in form, being irregularly and extensively sacculated. The position of these glands is unusual, but there are also other species like '' Doto fragilis'', that open into the channel of the mouth in advance of the buccal mass.

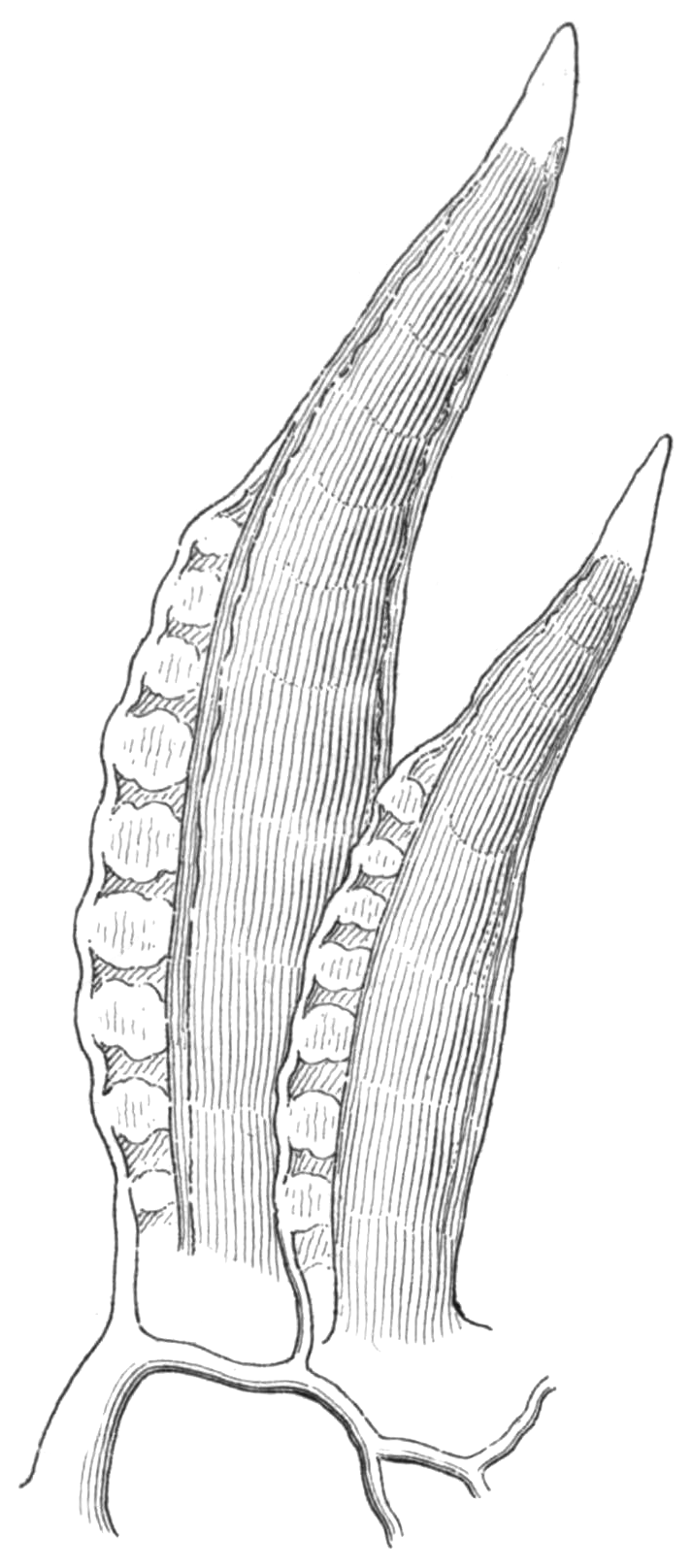

The buccal mass is small, rather long, slender, and irregularly elliptical. There are two corneous plates or jaws

Jaws or Jaw may refer to:

Anatomy

* Jaw, an opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth

** Mandible, the lower jaw

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Jaws (James Bond), a character in ''The Spy Who Loved Me'' and ''Moonraker''

* ...

. at the sides of the buccal mass. It is slightly prolonged behind for the reception of the posterior portion of the radula

The radula (, ; plural radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food ...

, and there are muscles are arranged around. Muscles are from dorsal view extensively developed, forming a dense mass, the fibres passing transversely and have their extremities inserted into the dorsal margins of the jaws. These muscles assist in the motion of the jaws. Muscles for moving the whole buccal mass forward are composed of flattened and isolated bands with their extremities attached to the posterior margin of the jaws and to the muscles forming the walls of the channel of the mouth.

''Fiona pinnata'' has two corneous jaws (mandibles), with a denticulate cutting-edge. The posterior portion is flattened. The corneous plates are little short of the size of the buccal mass, and much elongated, well arched and ovate. (When they are entirely isolated, they strongly resemble the shape the valves of a small bivalve of the genus '' Mytilus''). They are smooth, glossy, and of a brownish amber colour, darkest towards the anterior extremity, which gives support to the cutting blade. This is a winglike appendage of no great size, terminating below in a free point, and having the cutting margin arched forward, plain, and nearly at right angles to the general direction of the plate. Above is a small process or fulcrum — the point at which the two plates are articulated. Immediately behind this point there is the dorsal margin of the plates is reflected and expanded into an arched lobe for muscular attachment. The length of the jaw is 2.8 mm. The maximum width and maximum height of the jaw is 1.3 mm.

The radula

The radula (, ; plural radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food ...

is supported on a fleshy ridge that rises up from the floor of the buccal cavity, and extends in the antero-posterior direction from the oesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

towards the anterior opening. The radula is long, linear, and strap-formed, and is composed of semicircular and crescent-shaped denticles (tiny teeth) of an orange colour. There are 40 rows of teeth in radula: 15 oldest denticles in the anterior end, then there are 22 denticles after the angle and three incomplete denticles in the sheath in the posterior end of the radula. The radula formula is 0+1+0, which means that there is only a single central denticle in each row. There is a pointed spine in the centre, and 6 or 6-7 smaller spines on each side of the denticle. There are also sometimes minute spines at the base of denticle's outer margin. All the spines are a little bent, and have their points directed backwards towards the oesophageal opening. The whole length of the radula is 2.6 mm.

The oesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

is a short and rather slender tube. It leads from the upper part of the buccal mass towards, and opens into, the anterior margin of a distinct pyriform stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

. The stomach has the broad end forward, is placed above the reproductive system, and lies quite in the anterior portion of the visceral cavity. The internal surface of the stomach is not lamellated. The intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

leads from posterior end of the stomach, and is inclining slightly to the right side and passes backwards to the tubular anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, d ...

. The anus is placed a little to the right of the median line of the back, immediately behind the heart. The intestinal tube is rather short, of equal diameter throughout, and internally plicated longitudinally.

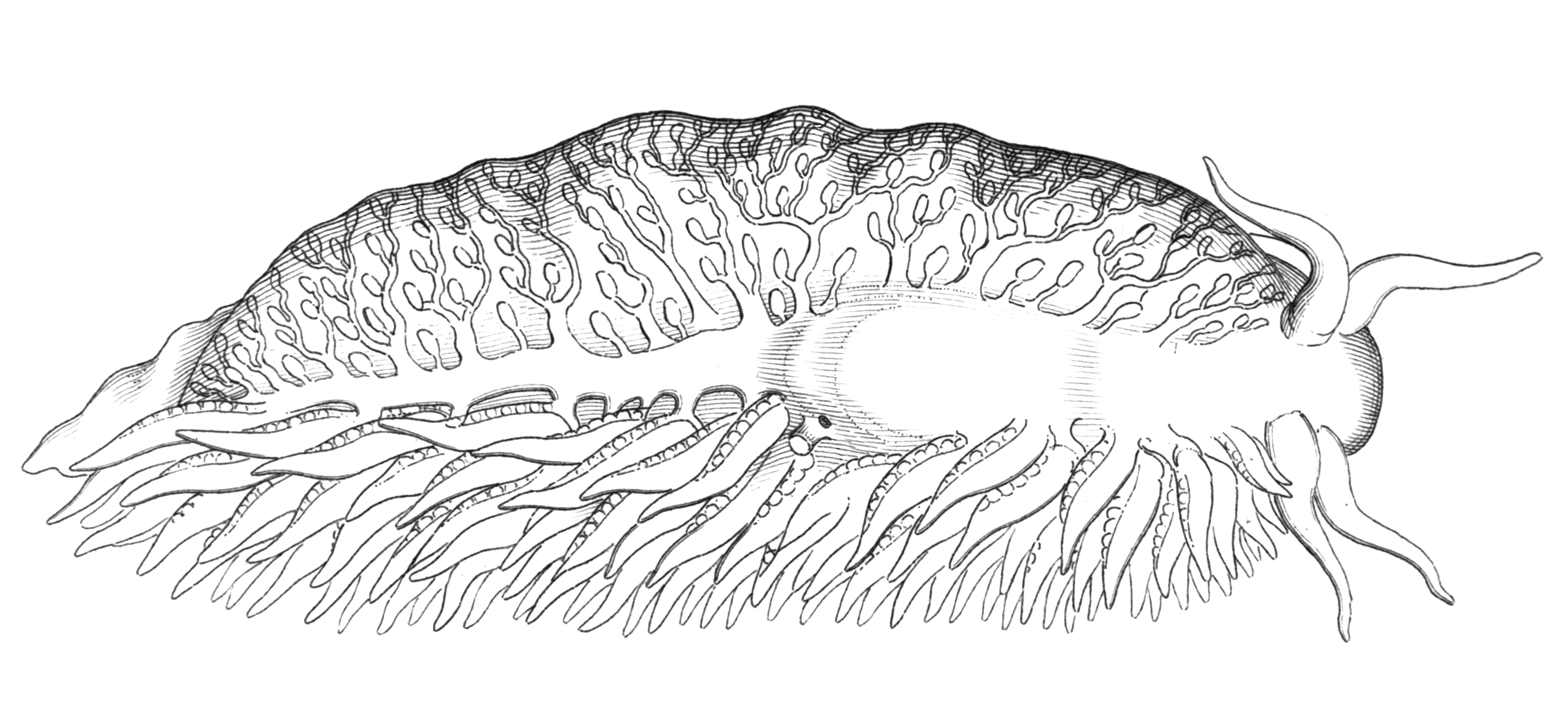

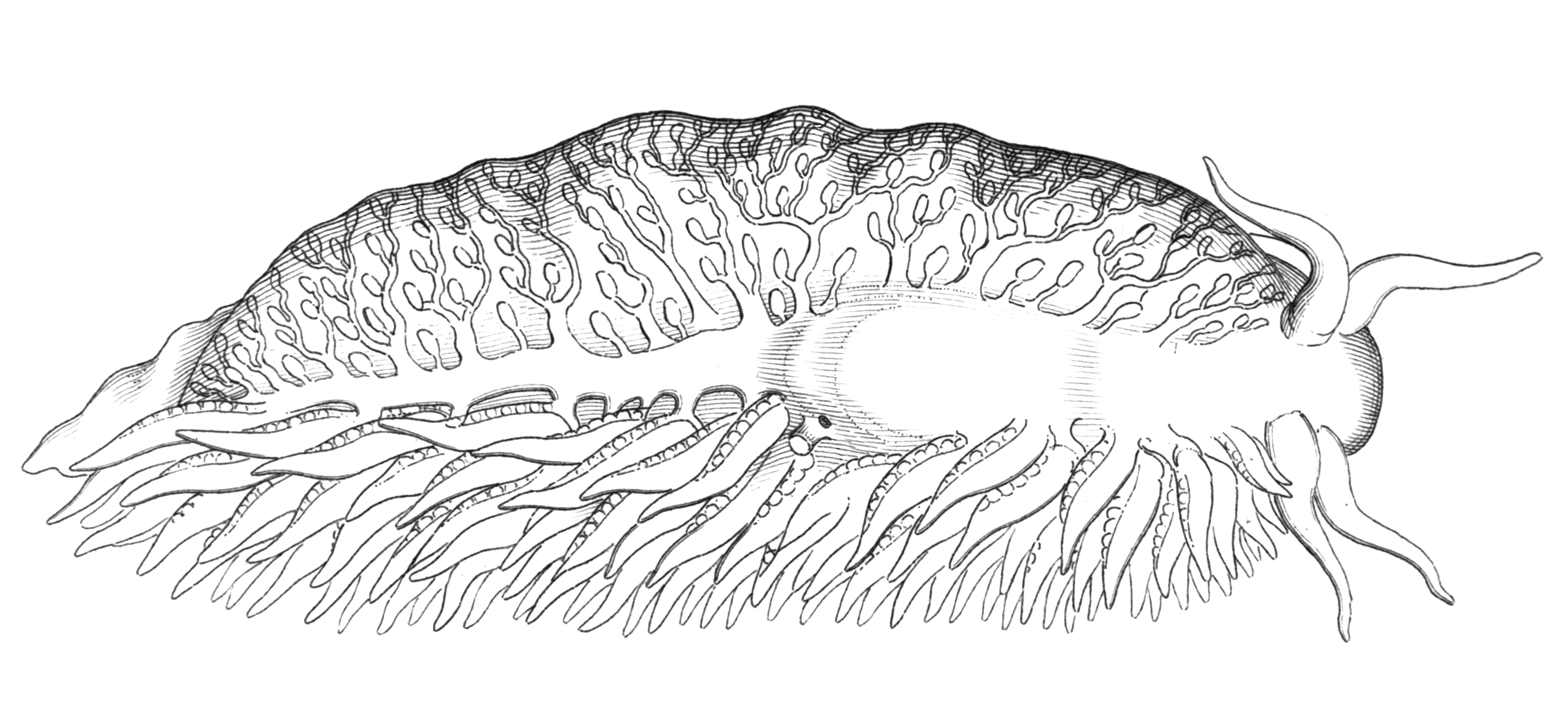

The hepatic apparatus is very peculiar in this animal. The caudal end of the stomach receives two biliary duct

A bile duct is any of a number of long tube-like structures that carry bile, and is present in most vertebrates.

Bile is required for the digestion of food and is secreted by the liver into passages that carry bile toward the hepatic duct. It ...

s, one on each side of the intestine. These ducts or hepatic canals are nearly as wide as the intestine, and they are diverging as they leave the stomach, very shortly pass into the skin at the sides of the back, where each opens into a wide channel that extends nearly the whole length of the body. The channels receive numerous branches, which communicate with the glands of the cerata, and as they approach the lateral expansion at the side of the body. These channels are subdivided several times and are irregularly disposed. The anterior portions of the great hepatic channels are connected with two folliculated glandular bodies much and irregularly sacculated. These glands are united to the skin, one on each side near the region of the stomach, and probably form the inner walls of those portions of the channels. Hepatic canals are almost entirely within the skin. The hepatic glands are large, nearly filling the cerata. They are slightly and irregularly sacculated, with the inner surface of the investing membrane lined with a dark granular substance; above, this substance is very abundant, forming a dense mass; below, the membrane in some of the cerata is entirely devoid of it.

The arrangement of the hepatic canals differs from that which prevails in the Eolidida. In ''Eolis'', ''Embletonia'', ''Doto'', ''Dendronotus'', ''Lomonotus'', and ''Antiopa'', the principal canals lie free in the visceral cavity, and in all of them there is a median posterior trunk. In these respects ''Oithona'' would appear to resemble ''Hermaa'', in which the whole of the hepatic ramifications are apparently connected with the skin, and there are only two principal trunks, which pass down the sides of the back. It is evident, however, that the digestive system alone sufficiently distinguishes ''Oithona'' from all the above genera, not even excepting ''Hermaa''.

In the central part of the caudal end of the body, behind the ovary, there is likewise a glandular substance, of a reddish colour, folliculated and apparently branched, in connexion with the branches of the hepatic canals within the skin. These branches at the posterior portion of the body probably form a sort of network of tubes across the dorsal aspect. Such perhaps may be inferred from the appearance the branches present when the skin of the back is divided down the median line. See also MacFarland (1966page 357

.

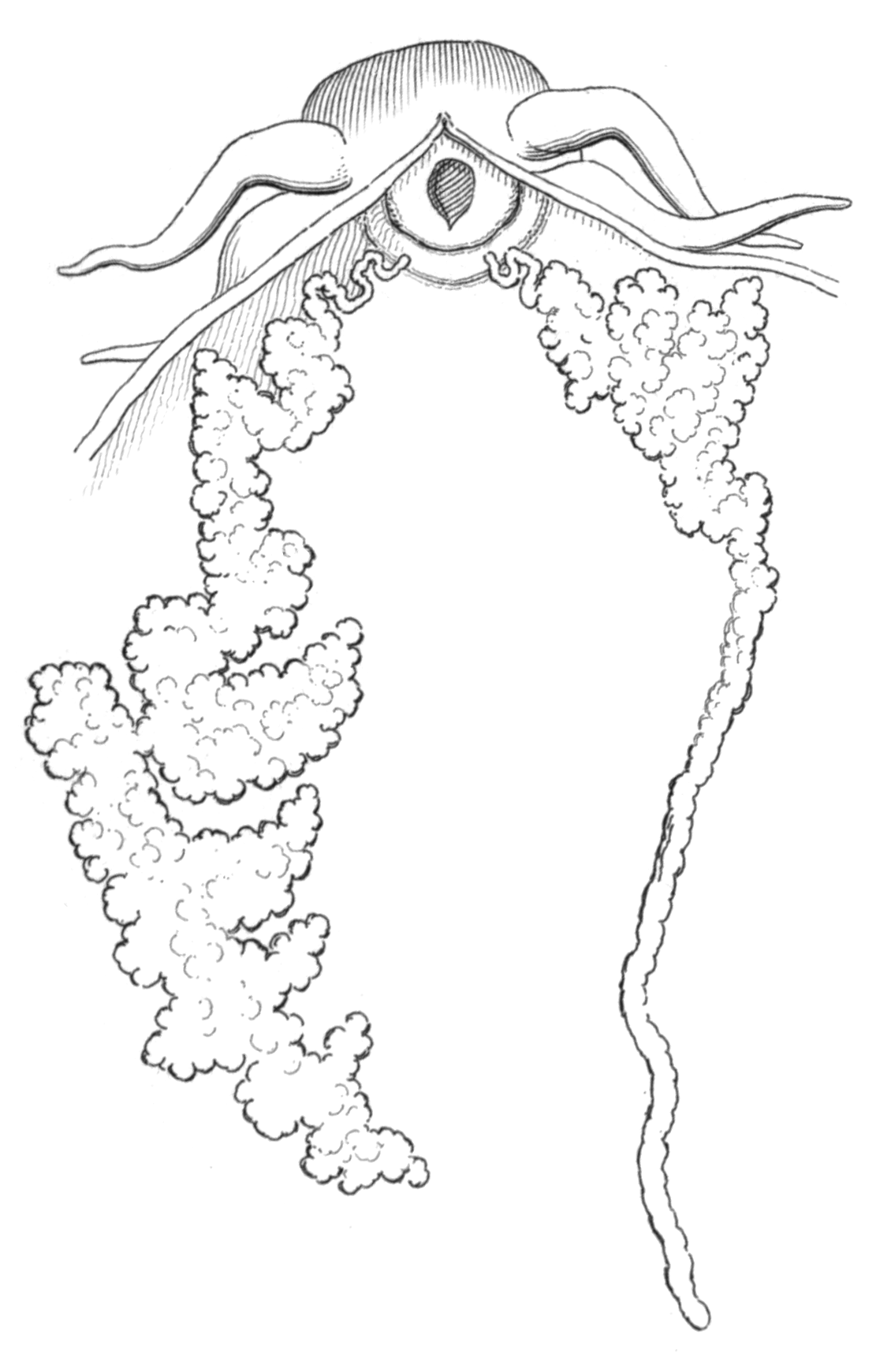

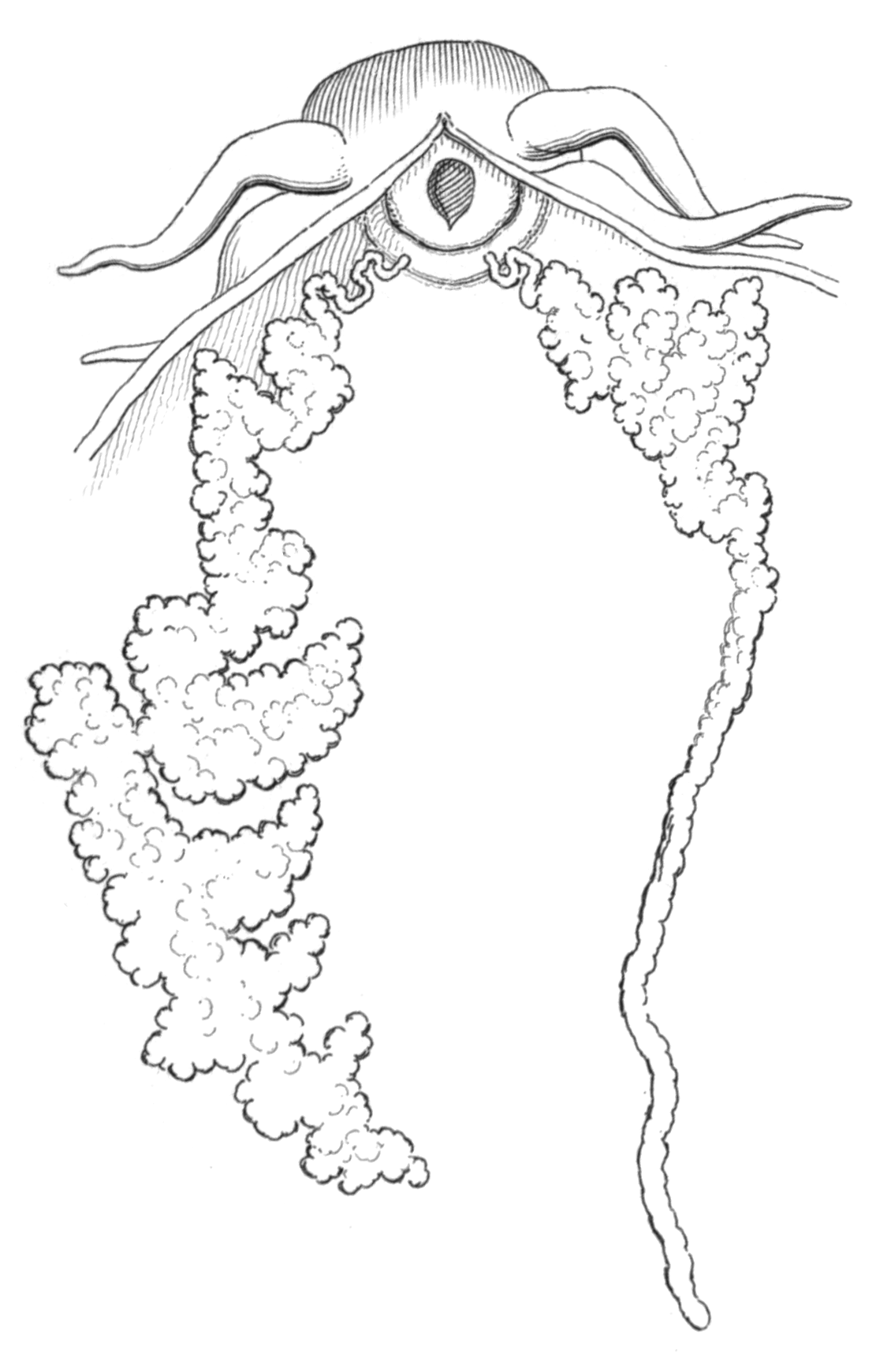

Reproductive system

Reproductive system

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are als ...

: There are two genital openings on the right side of the head behind the oral tentacle: the opening for the penis and for the (hermaphroditic) genital pore. The reproductive system and the mucous gland is the same as in the genus '' Aeolidia''. The only difference is that there is a distinct vas deferens in ''Fiona pinnata''.

On laying open the dorsal skin, the reproductive organs are found, as usual, to occupy much of the visceral cavity, having the stomach and intestine lying above, and the buccal mass in front. The penis is placed in advance of the other parts, and, in its retracted state, is long, rather slender, and linear. The penis has a conical form during mating. The outer extremity of the penis leads through the wall of the visceral cavity to the external opening, and on its way the sheath or external covering of the penis becomes firmly attached to the muscles of the skin.

The ovotestis

An ovotestis is a gonad with both testicular and ovarian aspects. In humans, ovotestes are an infrequent anatomical variation associated with gonadal dysgenesis. The only mammals where ovotestes are not symptomatic of an intersex variation are mole ...

(hermaphrodite gland) is yellow with white dots. The ovotestis fills the posterior portion of the visceral cavity, and is composed of large irregular lobules made up almost entirely of eggs, and packed into a dense mass, tapering a little behind and truncated in front.

The testis is a stout flesh-coloured tube, two or three times convoluted. It tapers at one extremity into a long slender duct or vas deferens, which is united to the inner extremity of the penis. The other extremity of the testis suddenly contracts into an equally slender duct, but very much shorter, and is joined by this duct to the oviduct.

The spermoviduct leaves the anterior border of the ovary as a slender tube, but, almost immediately dilating, equals the diameter of the testis. This dilated portion of the spermoviduct rests between the lobes of the mucous gland

Mucous gland, also known as muciparous glands, are found in several different parts of the body, and they typically stain lighter than serous glands during standard histological preparation. Most are multicellular, but goblet cells are single-cel ...

, and is at first somewhat sacculated and convoluted. Spermoviduct then passes forward and suddenly contracts to its original diameter, and then advances to the anterior border of the mucous gland and receives the duct from the testis as before described. It then bends a little backward and is shortly joined by a duct from the spermatheca. Spermatheca is a small oval membranous sac, lying between the lobes and at the front margin of the mucous gland. The duct, which is short and slender, passes from one end of the sac, and, at the point where the duct is united to the oviduct, it is joined by a tube which comes from the external orifice immediately within the female opening. This tube is the vagina or copulatory channel, and is cemented to the upper wall of the female channel. Just before the vagina reaches the duct of the spermatheca and oviduct, it gives off a branch which sinks into the female channel, and so far may be looked upon as a portion of the oviduct, for it is by this branch that the eggs find their way to the female outlet.

The mucous gland for the secretion of the mucus-like envelope of the eggs, is composed of two lateral lobes separated on the upper surface by a deep fissure. These lobes are semipellucid and are formed of a coarsely convoluted tube, that is on its right side anterior portion opake and flesh-coloured. The two lobes open into the female channel, which is wide and quite long.

Circulatory and respiratory system

The

The circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

and respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

is unique in this animal, because nearly the whole of these vessels are distinctly visible on the skin of the back, rising above the general surface. The heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

is situated about in the middle of the back, where it forms a large oval swelling immediately below the skin, having the generative organs beneath. From the posterior end of the heart there a broad elevated but rounded ridge passes down the median line of the back to the caudal end of the body. This ridge is joined on either side by numerous similarly elevated branches, which divide and subdivide as they approach the pallial-like expansion on the sides of the body. The whole of these branches and their subdivisions, standing boldly up from the general surface of the skin, have the branchial cerata set along them, and they give off twigs, which pass up the margin of the broad, flounced, membranous expansion of the cerata.

On opening the heart from above, the ventricle and auricle are found to occupy a well-defined oval pericardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made of ...

. The ventricle is large and muscular, of an irregular elliptical form, giving off the aorta in front, which in the usual manner supplies branches to the various organs. The auricle is united to it behind, a little on the left side. The auricle is delicate in comparison with the ventricle, but is nevertheless abundantly supplied with muscular fibres; it lies diagonally in the pericardium, having the left side advanced almost to the front of that organ where it receives a trunk-vein from the skin. The right side of the auricle stretches backward, and receives a similar trunk-vein from the skin of this side almost at the posterior extremity of the pericardium.

On laying the dorsal wall of the auricle open, its cavity is found to be continuous with that of the great posterior elevated median ridge or trunk vein before alluded to, and on opening this trunk-vein the various lateral branches are observed debouching into it on either side. It is therefore evident that this trunk-vein, which lies entirely within the skin, is the great posterior afferent or branchio-cardiac vein, and that all the elevated branches coming to it from the cerata are also afferent vessels. This way are cerata used for breathing as a specialized breathing organ.

The oxygenated blood from the heart leads to the aorta, to sinuses where it oxygenates tissues. Deoxygenated blood goes to efferent branchial vessels in cerata. These efferent vessels can be seen in a transverse section of the cerata as widish canal to pass up the opposite margin. From efferent vessels the blood goes into afferent vessel, where is gets an oxygen. Dorsal skin also partly serves as a breathing organ.

Excretory system

Excretory system

The excretory system is a passive biological system that removes excess, unnecessary materials from the body fluids of an organism, so as to help maintain internal chemical homeostasis and prevent damage to the body. The dual function of excreto ...

: The renal pore is between heart and anus.

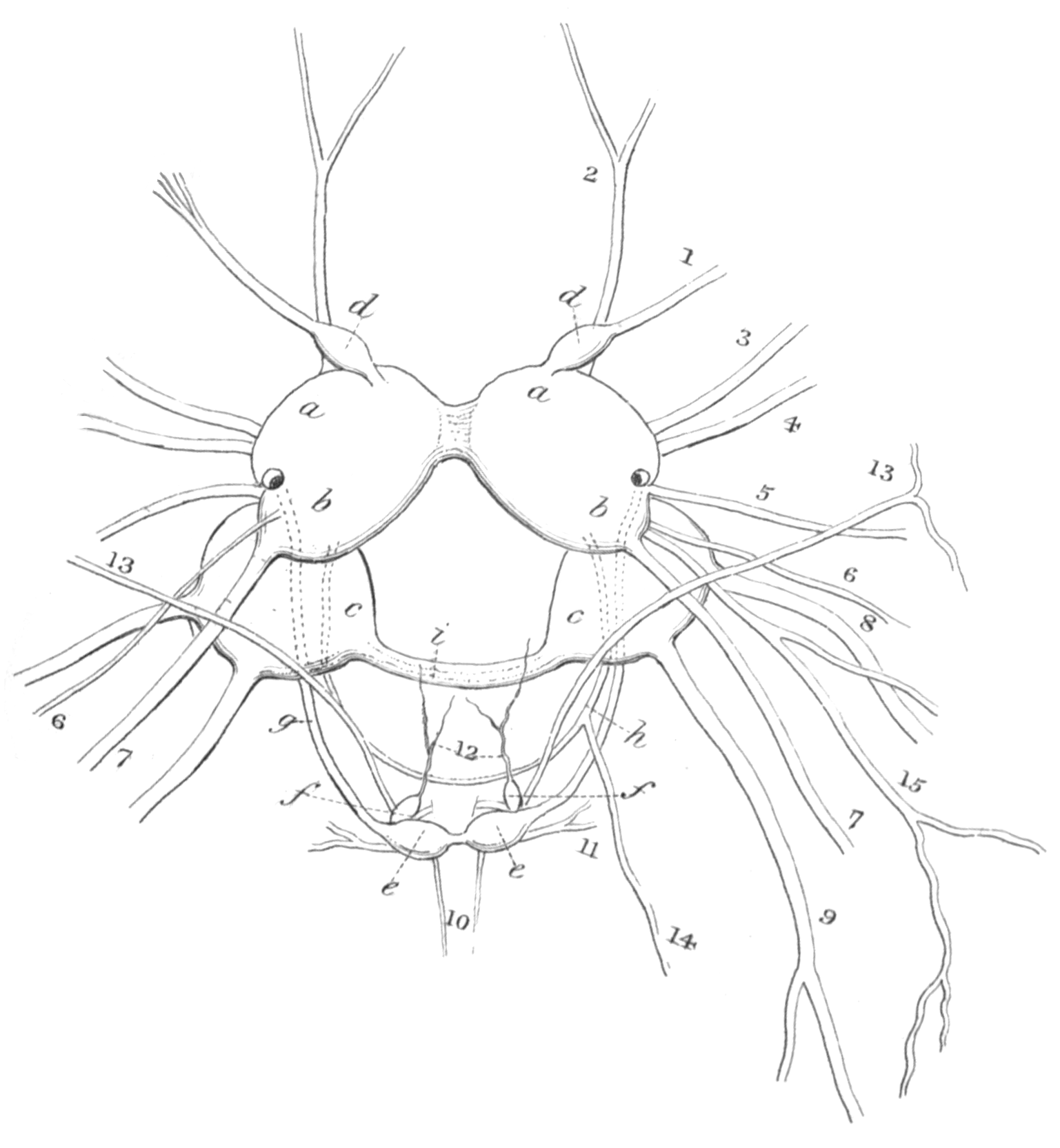

Nervous system

Nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

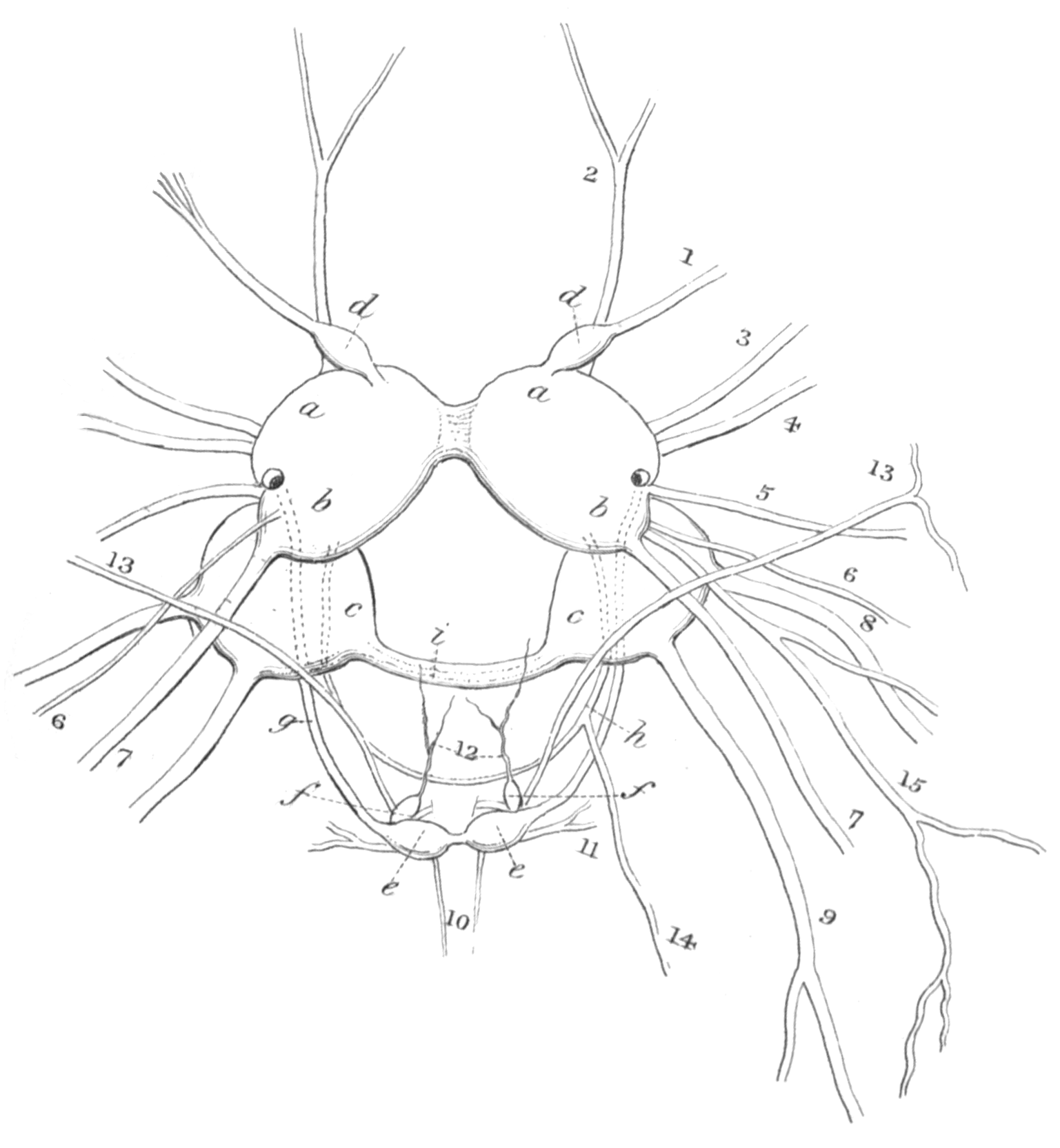

: The cerebral ganglia are placed at the commencement of the oesophagus. There are as usual four pairs of supra-oesophageal ganglia, though at first sight only three are apparent. The cerebroid and branchial are completely fused. Branchial ganglia form two oval central masses, resting upon the upper surface of the oesophagus, one on each side of the median line, across which they are united at the anterior extremity by a short but distinct commissure. Their posterior extremities diverge and are slightly bilobed, marking the boundaries of the two ganglia of which each mass is composed, — the anterior lobe indicating the cerebroid, the posterior the branchial. (Branchial ganglia are also fused in '' Onchidoris bilamellata'' and in '' Lamellidoris aspera''.) The pedial ganglions are irregularly rounded, being equal in bulk to the cerebroid and branchial together. They lie against the sides of the oesophagus, and are united to the under surface of the central masses. The fourth pair of ganglions are the olfactory: they are well developed, though very much smaller than those just described, and are joined by a short commissure to the upper surface of the anterior margins of the cerebroid ganglions.

The infra-oesophageal ganglions are placed in the usual situation on the buccal mass, below the oesophagus. The buccal ganglions are scarcely larger than the olfactory, and are of an oval form, their inner extremities being connected across the median line by a short commissure; their outer extremities receive a cord of communication from each of the cerebroid ganglions. Two minute elliptical ganglions are almost sessile on the anterior

border of the buccal ganglions; these are the gastro-cesophageal ganglions. Thus in all there are six pairs of ganglions; four above the gullet, and two below it.

The first pair of nerves come from the olfactory ganglions, and are large, but of no great length; they divide into several filaments as they enter the base of the dorsal tentacles. The second pair pass from the under surface of the anterior border of the cerebroid ganglions, not far from their union with the olfactory ganglions; these nerves go to supply the upper surface of the channel of the mouth. The third and fourth pairs of nerves issue from the same ganglions, but considerably behind the second pair; these also go to the channel of the mouth; the third probably sending a branch to the oral tentacles. A strong cord passes off close to the root of the fourth pair: these cords curve round the oesophagus and are united to the outer extremities of the buccal ganglions, forming the anterior collar. The fifth pair of nerves issue apparently from the outer border of the branchial ganglia, and go to the skin by the side of the head. The sixth pair are small, and come from the upper surface of the branchial ganglions; these nerves go to the skin of the sides of the back. The seventh, much larger than the sixth, emerge from the posterior margin of the same ganglions, and supply the dorsal skin, and apparently likewise the cerata. These are the branchial nerves. The eighth and ninth pairs are large nerves; they issue from the outer border of the pedial ganglions and go to the foot. The posterior margins of these ganglions are united by a stout, shortish commissure, composed of two or three cords, which, passing below the gullet, form the great oesophageal collar. The tenth pair of nerves are given off from the posterior margin of the buccal ganglions; these pass into the buccal mass and go to supply the tongue. The eleventh pair, issuing from the outer extremities of the buccal ganglions, are distributed to the muscles of the buccal mass. The twelfth pair come from the apex of the gastro-oesophageal ganglions, and

being applied to the gullet, each divides into two branches, one of which supplies the upper portion of that tube, the other, passing down it, goes to the stomach as in the other nudibranch

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs which shed their shells after their larval stage. They are noted for their often extraordinary colours and striking forms, and they have been given colourful nicknames to matc ...

s. The thirteenth pair are large; these are the hepatic nerves; they issue from the buccal mass and probably (as in genus '' Aeolidia'') are connected at their origin with ganglions, which must be looked upon as belonging to the sympathetic system. Immediately on emerging from the buccal mass, they are connected to the buccal ganglions at their point of union with the gastrooesophageal, and then, arching outwards and upwards, pass from within the anterior oesophageal collar, and go to supply the glands of the cerata.

Other nerve include the "genital nerve" a single nerve given off from a delicate collar, the ends of which are united to the under-surface of the central masses, just where they are connected to the pedial ganglions. Another nerve, which was apparently also distributed to the genitalia; this seemed to come from the right branchial ganglion, at its union with the pedial. These two nerves are probably leading from visceral ganglia.

Ecology

This nudibranch ispelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

in a similar way to the nudibranch ''Glaucus atlanticus

''Glaucus atlanticus'' (common names include the blue sea dragon, sea swallow, blue angel, blue glaucus, dragon slug, blue dragon, blue sea slug and blue ocean slug) is a species of small, blue sea slug, a pelagic (open-ocean) aeolid nudibran ...

''. Unlike some other pelagic animals, this species cannot swim or even float in water by itself, thus although it is pelagic, it is not considered to be planktonic

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

.

''Fiona pinnata'' has even been found on both adult and juvenile loggerhead sea turtle

The loggerhead sea turtle (''Caretta caretta'') is a species of oceanic turtle distributed throughout the world. It is a marine reptile, belonging to the family Cheloniidae. The average loggerhead measures around in carapace length when fully ...

s from the Canary Islands.

Feeding habits

''Fiona pinnata'' attacks and preys onbarnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in eros ...

s of the genus ''Lepas

''Lepas'' is a genus of goose barnacles in the family Lepadidae.

Species

Species in the genus include:

* '' Lepas anatifera'' Linnaeus, 1758

* ''Lepas anserifera'' Linnaeus, 1767

* '' Lepas australis'' Darwin, 1851

* ''Lepas hilli

''Lepas'' ...

'': gooseneck barnacle

Goose barnacles, also called stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerly made up the taxonomic order Pe ...

''Lepas anatifera

''Lepas anatifera'', commonly known as the pelagic gooseneck barnacle or smooth gooseneck barnacle, is a species of barnacle in the family Lepadidae. These barnacles are found, often in large numbers, attached by their flexible stalks to floati ...

'', ''Lepas anserifera

''Lepas anserifera'' is a species of goose barnacle or stalked barnacle in the family Lepadidae. It lives attached to floating timber, ships' hulls and various sorts of flotsam.

Description

''Lepas anserifera'' has a shell or capitulum enclosed ...

'', '' Lepas fascicularis'', ''Lepas hilli

''Lepas'' is a genus of goose barnacles in the family Lepadidae.

Species

Species in the genus include:

* '' Lepas anatifera'' Linnaeus, 1758

* ''Lepas anserifera'' Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known a ...

'', and ''Lepas testudinata

''Lepas testudinata'' is a species of goose barnacle in the family Lepadidae

Lepadidae is a family of goose barnacles, erected by Charles Darwin in 1852. There are about five genera and more than 20 described species in Lepadidae.

Genera

Thes ...

'', which grow on floating debris. It can attack other barnacles, but only damaged ones: '' Pollicipes polymerus'' and ''Balanus glandula

''Balanus glandula'' (North American Acorn Barnacle, Common Acorn Barnacle) is one of the most common barnacle species on the Pacific coast of North America, distributed from the U.S. state of Alaska to Bahía de San Quintín near San Quintín, ...

''. It can also eat barnacles on the genus '' Alepas''McDonald G. R. & Nybakken J. W. (last change: 14 December 2009"A List of the Worldwide Food Habits of Nudibranchs"

. Accessed 20 December 2009

(see also Beeman & Williams 1980) and

cnidarian

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocytes, specialized cells that th ...

s ''Velella velella

''Velella'' is a monospecific genus of hydrozoa in the Porpitidae family. Its only known species is ''Velella velella'', a cosmopolitan free-floating hydrozoan that lives on the surface of the open ocean. It is commonly known by the names sea r ...

'' and ''Porpita porpita

''Porpita porpita'', or blue button, is a marine organism consisting of a colony of hydroids found in the warmer, tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans, as well as the Mediterranean Sea and eastern Arabian ...

''. The colour of the digestive gland in the cerata changes to bright blue when the animal feeds on ''Velella''.Thompson, T.E. and Brown, G.H., 1984. Biology of Opisthobranch Molluscs, Volume II. The Ray Society. 229 pages 41 plates, 40 figures, p. 125. Some authors have noted that ''Fiona pinnata'' does not feed on the siphonophore ''Physalia physalis

The Portuguese man o' war (''Physalia physalis''), also known as the man-of-war, is a marine hydrozoan found in the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean. It is considered to be the same species as the Pacific man o' war or blue bottle, which is ...

'' (see also Bayer 1963), but some authors mention '' Physalia'' as its prey.

Life cycle

The stadium of theveliger

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalve molluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

Description

The veliger is the characteristic larva of the gastropod, bivalve and scaphopod ...

larva of ''Fiona pinnata'' lasts five days. Then it undergoes a metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. Some inse ...

into a slug. The New Zealand malacologist Richard Cardeu Willan (1979) published a theory that the veliger can delay its metamorphosis if it does not find suitable floating habitat to attach itself to.

''Fiona pinnata'' grows very rapidly. It has one of the highest growth rates among all nudibranchs (that is compared with benthic nudibranchs, the only ones for which the growth rates are known). The only species known to grow faster than this is '' Doridella obscura''.

''Fiona pinnata'' can grow from 8 mm to 20 mm in 4 days.

veliger

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalve molluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

Description

The veliger is the characteristic larva of the gastropod, bivalve and scaphopod ...

of ''Fiona pinnata''.

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 7.png, Drawing of right side of young veliger.

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 6.png, Drawing of right side of veliger.

File:Fiona pinnata veliger 5.png, Drawing of right side of veliger.

References

This article incorporates public domain text from references.Further reading

* Bayer, F. M. (1963). "Observations on pelagic molluscs associated with the siphonophores ''Velella'' and ''Physalia''". ''Bulletin of Marine Science of the Gulf and Caribbean, University of Miami'' 13 (3): 454-466. * Beeman, R. D. & Williams G. C. (1980). ''Chapter 14. Opisthobranchia and Pulmonata: the sea slugs and allies''. pp. 308–354, pls. 95- 111. In: Robert H. Morris, Donald P. Abbott, & Eugene C. Haderlie. Intertidal invertebrates of California, ix + 690 pp., 200 pls. Stanford University Press. See page 338. * Bergh, L. S. R. (1859). "Contributions to a monograph of the genus ''Fiona'', Hanc". Copenhagen, pp. 1–20. pls. 1-2. * Bieri, R. (1966). "Feeding preferences and rates of the snail, ''Ianthina prolongata'', the barnacle, ''Lepas anserifera'', the nudibranchs, ''Glaucus atlanticus'' and ''Fiona pinnata'', and the food web in the marine neuston". ''Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory'' 14: 161–170, pls. III-IV. * Burn, R. F. (1966). "Descriptions of Australian Eolidacea (Mollusca: Opisthobranchia). 4. The genera ''Pleurolidia'', ''Fiona'', ''Learchis'', and ''Cerberilla'' from Lord Howe Island". ''Journal of the Malacological Society of Australia'' (10): 21–34. * Holleman, J. J. (1972) "Observations on growth, feeding, reproduction, and development in the opisthobranch ''Fiona pinnata'' (Eschscholtz)". ''Veliger'' 15 (2): 142–146. * Jeffreys, J. G. (1869) ''British conchology: or, an account of the Mollusca which now inhabit the British Isles and the surrounding seas''. J. Van Voorst, London. Volume 5, Pag35

figure 2. * Williams, M . N . (1978) ''Buccal glands of some aeolid nudibranchs (Ultrastructure and histochemistry)''. Unpubl. MSc thesis, University of Auckland. 96 pp.

External links

* Pelagic snails: the biology of holoplanktonic gastropod mollusks By Carol M. Lalli, Ronald W. Gilmer. via Google books * Powell A. W. B., ''New Zealand Mollusca'', William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand 1979 * Casteel D. B. (April 1904"Cell Lineage and Early Larval Development of ''Fiona marina'', a Nudibranch Mollusck"

''

Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

The ''Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Acad ...

'' 1 (6): 325-405.

photo 1

photo 2

{{Taxonbar , from=Q309687 Fionidae Gastropods described in 1831