Felice Napoleone Canevaro on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Felice Napoleone Canevaro (7 July 1838 – 30 December 1926) was an Italian admiral and politician and a

On returning to Italy, he was assigned to the broadside ironclad , commanded by Augusto Riboty. Aboard ''Re di Portogallo'', he took part in 1866 in the Third Italian War of Independence, during which the ship was engaged in operations against the fortress of Lissa in the

On returning to Italy, he was assigned to the broadside ironclad , commanded by Augusto Riboty. Aboard ''Re di Portogallo'', he took part in 1866 in the Third Italian War of Independence, during which the ship was engaged in operations against the fortress of Lissa in the

Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the

Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the  Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the

Knight of the Grand Cross decorated with the Great Cordon of the

Silver Medal for Civil Valor

Silver Medal for Civil Valor

Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence (with three bars)

Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence (with three bars)

Commander of the

Commander of the

senator of the Kingdom of Italy

The Senate of the Kingdom of Italy () was the upper house of the bicameral parliament of the Kingdom of Italy, officially created on 4 March 1848, acting as an evolution of the original Subalpine Senate. It was replaced on 1 January 1948 by the ...

. He served as both Minister of the Navy and Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

and was a recipient of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

The Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus ( it, Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro) (abbreviated OSSML) is a Roman Catholic dynastic order of knighthood bestowed by the royal House of Savoy. It is the second-oldest order of knighthood in the wo ...

. In his naval career, he was best known for his actions during the Italian Wars of Independence The War of Italian Independence, or Italian Wars of Independence, include:

*First Italian War of Independence (1848–1849)

*Second Italian War of Independence (1859)

*Third Italian War of Independence (1866)

*Fourth Italian War of Independence (19 ...

and later as commander of the International Squadron off Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

in 1897–1898.

Biography

The descendant of aLiguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

n family originally from Zoagli

Zoagli ( lij, Zoagi) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa in the Italian region Liguria, located about southeast of Genoa. Zoagli is a popular destination during all seasons of the year by tourists from all over the wo ...

, Canevaro was born in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, to Giuseppe and Francesca Velaga.

Naval career

In 1852, Canevaro was admitted to the Kingdom of Sardinia's Royal Navy School atGenoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

, completing the course of instruction in 1855 and receiving a commission as an ensign second class.

Italian Wars of Independence

In 1859, with the rank of secondlieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

, Canevaro took part in Royal Sardinian Navy

The Royal Sardinian Navy was the naval force of the Kingdom of Sardinia. The fleet was created in 1720 when the Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus II, became the King of Sardinia. Victor Amadeus had acquired the vessels be used to establish the flee ...

operations in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

aboard the transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, an ...

''Beroldo'' and the sailing frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

during the Second Italian War of Independence.

In 1860, Canevaro arrived in Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, aboard , the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of the Sardinian squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, de ...

. When the supporters of the Italian nationalist leader General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

organized their navy, he resigned from the Royal Sardinian Navy to enlist in the Garibaldian navy. Aboard the steam frigate ''Tukory'' on the night of 13 August 1860, Canevaro distinguished himself during an unsuccessful attempt to board the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and a ...

steam ship-of-the-line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colum ...

''Monarca'' while she was anchored in the port of Castellammare di Stabia. He received the Silver Medal of Military Valor for his actions during this engagement.

In the autumn of 1860, Canevarro was reinstated in the Royal Sardinian Navy. While embarked on the Sardinian steam frigate from December 1860 to March 1861, he took part in the Siege of Gaeta and a siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

of Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

during operations in which ''Carlo Alberto'' repeatedly exchanged fire with hostile forces at close range along the coast. After the campaign, he was made a Knight of the Military Order of Savoy

The Military Order of Savoy was a military honorary order of the Kingdom of Sardinia first, and of the Kingdom of Italy later. Following the abolition of the Italian monarchy, the order became the Military Order of Italy.

History

The origin of ...

, and in 1863, he was promoted to '' luogotenente de vascello''. In 1865–1866, Canevaro was on board the steam frigate , under the command Guglielmo Acton, during a long cruise that included a transatlantic voyage

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuries ...

, operations along the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

, a transit of the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

into the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, and steaming up the coast of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

.

On returning to Italy, he was assigned to the broadside ironclad , commanded by Augusto Riboty. Aboard ''Re di Portogallo'', he took part in 1866 in the Third Italian War of Independence, during which the ship was engaged in operations against the fortress of Lissa in the

On returning to Italy, he was assigned to the broadside ironclad , commanded by Augusto Riboty. Aboard ''Re di Portogallo'', he took part in 1866 in the Third Italian War of Independence, during which the ship was engaged in operations against the fortress of Lissa in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. As flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of the 3rd Division, and with Canevaro aboard as the division's chief-of-staff, ''Re di Portogallo'' led the division's attack on Porto San Giorgio

Porto San Giorgio is a ''comune'' (town or municipality) in the Province of Fermo, in the Marche region of Italy. It has approximately 15,700 inhabitants (2021) and it is located on the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

History

Already famous at the tim ...

on 18 July 1866.

Battle of Lissa

On 20 July 1866, ''Re di Portogallo'' played a particularly prominent role in the Battle of Lissa against theAustrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

fleet. She first opened fire on the Austrian steam corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

, scoring a hit below the waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

that opened a leak that caused more water to enter ''Erzherzog Friedrich'' than her pumps could handle, forcing '' Erzherzog Friedrich'' to retreat in the direction of Lissa. While chasing the damaged ''Erzherzog Friedrich'', ''Re di Portogallo'' sighted the Austrian steam ship-of-the-line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colum ...

, which, although seriously damaged by a broadside fired by the Italian ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

ram , was approaching to defend ''Erzherzog Friedrich''.Ermanno Martino, ''Lissa 1866: perché?'' in ''Storia Militare'' n. 214 and 215, July–August 2011 (Italian). ''Re di Portogallo'' attempted to ram ''Kaiser'', but ''Kaiser'' steered toward ''Re di Portogallo'' and the two ships collided violently head-on. ''Kaiser'' had the worst of the collision, which badly damaged her bow, destroyed her bowsprit, and left her figurehead, a wooden statue of the Austrian emperor Kaiser Franz Joseph I

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

, stuck in the hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

of ''Re di Portogallo''; it became an Italian war trophy. Entangled with ''Kaiser'', ''Re di Portogallo'' pummeled her with gunfire at close range, inflicting many casualties on her crew and bringing down her foresail

A foresail is one of a few different types of sail set on the foremost mast (''foremast'') of a sailing vessel:

* A fore-and-aft sail set on the foremast of a schooner or similar vessel.

* The lowest square sail on the foremast of a full-rig ...

, which crashed onto her funnel. ''Re di Portogallo'' put her engines astern to pull away from ''Kaiser'' and maneuver to ram her again, but could not resume her attack because smoke had concealed ''Kaiser'', which the officers of ''Re di Portogallo'' mistakenly believed may have sunk. As the battle continued ''Re di Portogallo'' found herself surrounded by four Austrian ships, but she managed to escape from them thanks to the ability of her commander, Riboty. One of the Italian ships most heavily involved in the battle, ''Re di Portogallo'' suffered serious damage, including the loss of her anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek ἄγ ...

s and some of her boats and having of her armor dislodged, most of this damage occurring during the duel with ''Kaiser''. Although the outcome of the Battle of Lissa ultimately was disastrous for the Italian fleet, Canevaro received a second award of the Silver Medal for Military Valor, while ''Re di Portogallo''s commanding officer Riboty received the Gold Medal of Military Valor

The Gold Medal of Military Valour ( it, Medaglia d'oro al valor militare) is an Italian medal established on 21 May 1793 by King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia for deeds of outstanding gallantry in war by junior officers and soldiers.

The fac ...

.

1870s–1890s

Promoted to '' capitano di fregata'' in 1869, Canevaro served as a naval attaché at the Italian embassy inLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

from March 1874 to August 1876. From January 1877 to March 1879, while in command of the cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

, he circumnavigated the globe, departing Italy, transiting the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

, skirting Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

, visiting ports in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and the Netherlands East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

– where ''Colombo'' recovered the body of the Italian general and politician Nino Bixio

Gerolamo "Nino" Bixio (, ; 2 October 1821 – 16 December 1873) was an Italian general, patriot and politician, one of the most prominent figures in the Italian unification.

Life and career

He was born Gerolamo Bixio in Genoa. While still a boy, ...

, who had died of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

in Banda Aceh

Banda Aceh ( Acehnese: ''Banda Acèh'', Jawoë: كوتا بند اچيه) is the capital and largest city in the province of Aceh, Indonesia. It is located on the island of Sumatra and has an elevation of . The city covers an area of and had ...

on Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

in 1873 – and then went on to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

(including Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

), Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. After transiting the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

into the Atlantic Ocean, ''Colombo'' steamed up the coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

to the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, then crossed the Atlantic to return to Italy.

Promoted to ''capitano di vascello

The rank insignia of the Italian Navy are worn on epaulettes of shirts and white jackets, and on sleeves for navy jackets and mantels.

Rank structure

Officers

Notes:

1 The rank of ''"ammiraglio"'' (admiral) is assigned to the only naval off ...

'', Canevaro performed various important duties, including service as chief-of-staff of the 3rd Maritime Department headquartered at Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, second-in-command of the Italian Naval Academy, and commanding officer of the ironclad battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

. In 1884, while in command of ''Italia'', he played an active role in humanitarian work and public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

during a cholera epidemic in La Spezia

La Spezia (, or , ; in the local Spezzino dialect) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second largest city ...

, and he received the Silver Medal for Civil Valor for these efforts.

Promoted to counter admiral (the equivalent of rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

) in 1887, Canevaro assumed command of the arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

of Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

and later of the 2nd Naval Division of the Permanent Squadron. He was promoted to vice admiral in 1893, and King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

Umberto I appointed him a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy

The Senate of the Kingdom of Italy () was the upper house of the bicameral parliament of the Kingdom of Italy, officially created on 4 March 1848, acting as an evolution of the original Subalpine Senate. It was replaced on 1 January 1948 by the ...

– an appointment for life – in 1896, the same year in which he assumed command of the ''Regia Marina''s Naval Squadron.

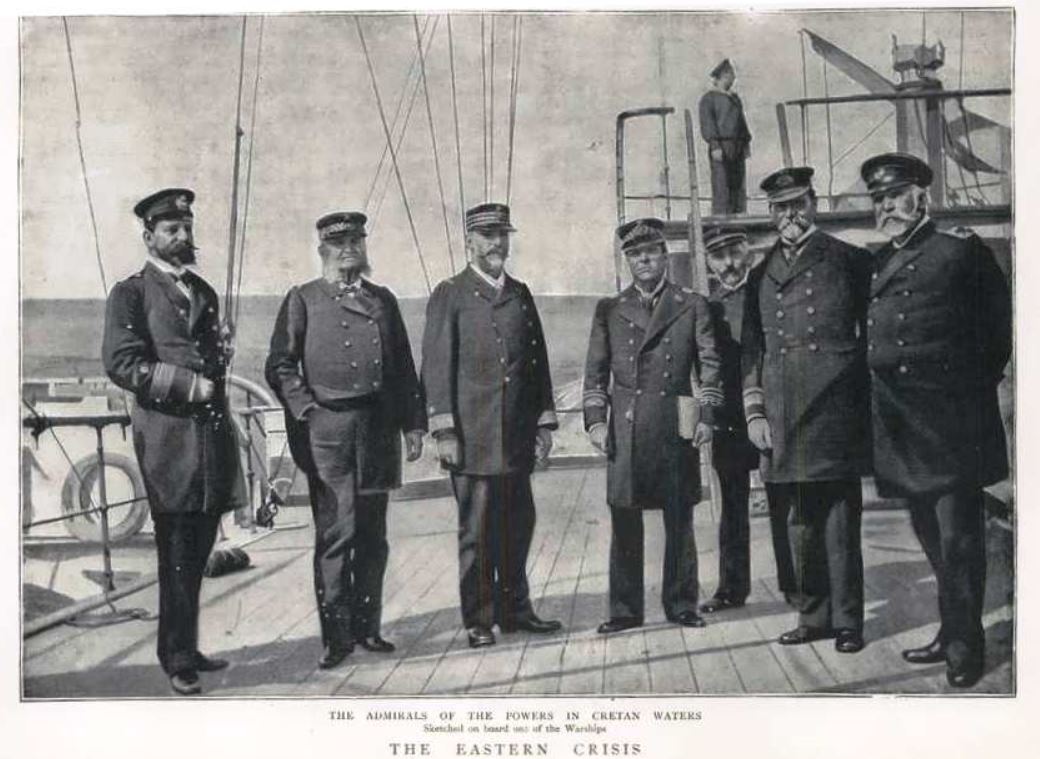

International Squadron

In February 1897, when a Christian uprising against the authority of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

broke out on the island of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, Canevaro arrived at Crete in command of the 1st Division of the 1st Squadron, consisting of the ironclad battleships (his flagship) and , the protected cruiser , and the torpedo cruiser . Canevaro – who relieved the commander of the Italian naval squadron, Rear Admiral Gualterio, who had previously been in command of the 2nd Naval Division – assumed command of the International Squadron of warships off Crete on 16 or 17 February 1897 (sources differ) as the most senior admiral present, and took up duties as president of the "Admirals Council," which consisted of the senior admirals present off Crete of each of the six countries participating in the International Squadron. The squadron put landing detachments ashore, but Christian insurgents continued to attack Ottoman forces and Canevaro soon ordered International Squadron ships to bombard them during February and March 1897 to stop the fighting. Although some political opponents in the Italian legislature attacked him for ordering the International Squadron to bombard the insurgents, Canevaro received great credit during his time in command of the squadron for his ability to exercise diplomacy and mediate disputes between the six Great Powers – Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, Italy, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

– making up the squadron and for the way in which he dealt with the confusing and anarchic situation on Crete, balancing humanitarian compassion and a spirit of conciliation in his dealings with Greek, Christian insurgent, and Ottoman forces on the island with the occasional need to use force to halt fighting and quell disturbances. Before leaving the International Squadron in 1898, Canevaro negotiated an agreement under which all combat on Crete would cease and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and the Ottoman Empire would withdraw their forces from the island in anticipation of the creation of an autonomous Cretan State under the suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

of the Ottoman sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

. Such was his reputation that when the creation of an office of High Commissioner of the Cretan State was proposed in the spring of 1898, Canevaro received an invitation to become the first high commissioner, but he declined the offer, and instead Prince George of Greece and Denmark became the first high commissioner when the Cretan State finally came into existence in December 1898.

Government minister

WhenPrime Minister of Italy

The Prime Minister of Italy, officially the President of the Council of Ministers ( it, link=no, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is ...

Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì

Antonio Starrabba (o Starabba), Marquess of Rudinì (16 April 18397 August 1908) was an Italian statesman, Prime Minister of Italy between 1891 and 1892 and from 1896 until 1898.

Biography Early life and patriotic activities

He was born in Pal ...

, formed the government for his fifth ministry, Canevaro turned over command of the International Squadron to its next-most-senior admiral, Rear Admiral Édouard Pottier of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, and returned to Italy to serve as di Rudini′s Minister of the Navy Minister of the Navy may refer to:

* Minister of the Navy (France)

* Minister of the Navy (Italy)

The Italian Minister of the Navy ( it, Ministri della Marina del Regno) was a member in the Council Ministers until 1947, when the ministry merged ...

. Taking office on 1 June 1898, he served only four weeks, until the di Rudini government was replaced on 29 June 1898 by that of Prime Minister General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Luigi Pelloux

Luigi Gerolamo Pelloux (La Roche-sur-Foron, 1 March 1839 – Bordighera, 26 October 1924) was an Italian general and politician, born of parents who retained their Italian nationality when Savoy was annexed to France. He was the Prime Minister of ...

. On the same day Pelloux took office, Canevaro changed portfolios to become the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs

The Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs is the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Italy. The office was one of the positions which Italy inherited from the Kingdom of Sardinia where it was the most ancient ministry of the government: thi ...

. In his new role, he attempted to continue Italy′s policy of loyalty to the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

with Austria-Hungary and the German Empire and of continued warm relations with the United Kingdom, but at the same time worked toward relaxing tensions with France, and he conducted secret negotiations with the French for a commercial treaty, which the countries signed on 26 November 1898. He also resisted pressure from Germany to change the status of the Cretan State, supporting its continuation as an autonomous state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.

However, despite his successes in negotiations on Crete while in command of the International Squadron, Canevaro's talent for leading military forces did not translate into success in international diplomacy when it came to larger issues. During the Fashoda Crisis

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis ( French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exp ...

of 1899 between France and the United Kingdom, Canevaro conducted intensive diplomacy as part of the ongoing European "Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

" in an effort to gain French and British recognition of an Italian interest in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

, but when the French and British concluded an agreement on 21 March 1899 that resolved the crisis, they offered no such recognition. Canevaro also was unsuccessful when in the wake of a number of anarchist attacks in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

– one of which resulted in the stabbing death of Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary Elizabeth on 10 September 1898 – he proposed an international anti-anarchist conference of diplomats and government security and judicial officials to address the situation; although some countries agreed to participate, the conference never took place.

A final blow to Canevaro's diplomatic career came in the "San Mun Affair" of 1899, in which Italy demanded that the Chinese Empire

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the ''Book of Documents'' (early chapter ...

grant it a lease for a naval coaling station at China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

's Sanmen Bay (known as "San-Mun Bay" to the Italians) similar to the lease the German Empire had secured in 1898 at Kiaochow Bay. From Sanmen Bay, Italy hoped to establish an area of influence in Chekiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Jiangs ...

. The Russian Empire and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

opposed the Italian demand, but the Italian ambassador in China, Renato De Martino, led Canevaro to believe that the area was ripe for the taking. The British government, although ambivalent toward the Italian move, gave its approval as long as Italy did not use force against the Chinese, but the British did not inform Canevaro that the United Kingdom′s representatives in China had advised that Italy could not achieve its goals without using force. Believing the opportunity to pursue Italy's interests in China was at hand, Canevaro had de Martino pass Italy′s demands to the Chinese imperial government in the winter of 1899, but the Chinese summarily rejected them on 4 March 1899. On 8 March, Canevaro instructed De Martino to present the demands again as an ultimatum and authorized the armored cruiser ''Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

'' and protected cruiser '' Elba'' to occupy the bay. When the British ambassador in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

reminded him that the United Kingdom did not support an Italian use of force, Canevaro issued a counterorder cancelling his authorization to use the two cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s in the bay, but De Martino received the counterorder before he received the original authorization to employ the ships. Unable to decipher the counterorder, De Martino presented the Italian ultimatum to China again on 10 March 1899, and China immediately refused to comply. Italy withdrew its ultimatum, becoming at the end of the 19th century the first and only Western power to fail to achieve its territorial goals in China. The fiasco was an embarrassment that gave Italy – still stung by its defeat at the hands of the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historical ...

in the Battle of Adowa in 1896 – the appearance of a third-rate power. On 14 March 1899, Canevaro attempted to present the affair to the Italian Parliament in a positive light, saying that be believed that China had rejected the Italian ultimatum in order to maintain a positive and productive relationship with Italy uninterrupted by negotiations over the bay, but such was the domestic criticism of the Italian failure as a humiliation and international criticism of it as a needless and unjustified provocation that Pelloux announced the resignation of his entire cabinet on 14 May 1899. He excluded Canevaro from the new cabinet he established that day.

Later naval service

Canevaro returned to the navy, commanding the 3rd Maritime District from 16 July 1900 to 16 January 1902 and presiding over the Supreme Council of the Navy from 16 January 1902 until 6 July 1903. He then retired and was placed on the reserve list, although in retirement he was promoted to vice admiral of the navy on 1 December 1923. He died atVenice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

on 30 December 1926.

Awards and honors

Italian awards and honors

Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

The Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus ( it, Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro) (abbreviated OSSML) is a Roman Catholic dynastic order of knighthood bestowed by the royal House of Savoy. It is the second-oldest order of knighthood in the wo ...

Order of the Crown of Italy

The Order of the Crown of Italy ( it, Ordine della Corona d'Italia, italic=no or OCI) was founded as a national order in 1868 by King Vittorio Emanuele II, to commemorate the unification of Italy in 1861. It was awarded in five degrees for civi ...

Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

of the Military Order of Savoy

The Military Order of Savoy was a military honorary order of the Kingdom of Sardinia first, and of the Kingdom of Italy later. Following the abolition of the Italian monarchy, the order became the Military Order of Italy.

History

The origin of ...

Silver Medal of Military Valour

The Silver Medal of Military Valor ( it, Medaglia d'argento al valor militare) is an Italian medal for gallantry.

Italian medals for valor were first instituted by Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia on 21 May 1793, with a gold medal, and, below it, ...

(two awards)

Maurician medal

The Maurician medal is an honorary degree granted to a soldier, after 50 years of service in the Italian army (the commanding years are added afterward). This medal was established by Carlo Alberto di Savoia, on 19 July 1839 on decree of the Reg ...

Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence (with three bars)

Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence (with three bars)

Commemorative Medal of the Unity of Italy

The Italian Risorgimento was celebrated by a series of medals set up by the three kings who ruled during the long process of unification - the Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence and the various versions of the Commemor ...

Foreign awards and honors

Order of Isabella the Catholic

The Order of Isabella the Catholic ( es, Orden de Isabel la Católica) is a Spanish civil order and honor granted to persons and institutions in recognition of extraordinary services to the homeland or the promotion of international relations a ...

(Kingdom of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

)

Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa

The Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa (also known as The Order of Our Lady of Conception of Vila Vicosa; pt, Ordem de Nossa Senhora da Conceição de Vila Viçosa) is a dynastic order of knighthood of the House of Braganza, the f ...

(Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal ( la, Regnum Portugalliae, pt, Reino de Portugal) was a monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also kno ...

)

Commemorative medal of the 1859 Italian Campaign

The Commemorative medal of the 1859 Italian Campaign (french: Médaille commémorative de la campagne d'Italie de 1859) was a French commemorative medal established by Napoleon III, following the 1859 French campaign in Italy during the Second I ...

(Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Empire, Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the French Second Republic, Second and the French Third Republic ...

)

In popular culture

Canevaro (spelled "Canavaro") is mentioned inNikos Kazantzakis

Nikos Kazantzakis ( el, ; 2 March ( OS 18 February) 188326 October 1957) was a Greek writer. Widely considered a giant of modern Greek literature, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in nine different years.

Kazantzakis's no ...

's novel ''Zorba the Greek

''Zorba the Greek'' ( el, Βίος και Πολιτεία του Αλέξη Ζορμπά, , Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas) is a novel written by the Cretan author Nikos Kazantzakis, first published in 1946. It is the tale of a young Greek int ...

'' and the subsequent film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

and musical

Musical is the adjective of music.

Musical may also refer to:

* Musical theatre, a performance art that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance

* Musical film and television, a genre of film and television that incorporates into the narr ...

of the same name, as the admiral and former lover of key character Madame Hortense, who thereafter calls Zorba by his name.

One of the main streets of the city center in Chania on Crete, ''odos Kanevarou'', is named after Canevaro.

See also

References

Notes

Bibliography

*External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Canevaro, Felice Napoleone 1838 births 1926 deaths 19th-century Italian military personnel 20th-century Italian military personnel 19th-century Italian politicians Foreign ministers of Italy Naval ministers Italian admirals People from Lima Italian military people of the wars of Italian unification Dukes of Italy Commanders of the Military Order of Savoy Commanders of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa Recipients of the Maurician medal Recipients of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Recipients of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Italy)