Fashoda Incident on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis ( French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an

During the late-19th century, Africa was rapidly being claimed and colonised by European colonial powers. After the 1885

During the late-19th century, Africa was rapidly being claimed and colonised by European colonial powers. After the 1885

The Fashoda Incident

West Chester University, 2014; Web, 12 July 2014; accessed 2019.10.20. Fashoda had been founded by the Egyptian army in 1855 as base from which to combat the

Fashoda had been founded by the Egyptian army in 1855 as base from which to combat the

Both sides insisted on their right to Fashoda but agreed to wait for further instructions from home. The two commanders behaved with restraint and even a certain humour. Kitchener toasted Marchand with whisky, the drinking of which the French officer described as "one of the greatest sacrifices I ever made for my country". Kitchener inspected a French garden commenting "Flowers at Fashoda. Oh these Frenchmen!" More seriously the British distributed French newspapers detailing the political chaos caused by the

Both sides insisted on their right to Fashoda but agreed to wait for further instructions from home. The two commanders behaved with restraint and even a certain humour. Kitchener toasted Marchand with whisky, the drinking of which the French officer described as "one of the greatest sacrifices I ever made for my country". Kitchener inspected a French garden commenting "Flowers at Fashoda. Oh these Frenchmen!" More seriously the British distributed French newspapers detailing the political chaos caused by the

As the commander of the Anglo-Egyptian army that had just defeated the forces of the

As the commander of the Anglo-Egyptian army that had just defeated the forces of the

international incident {{Refimprove, date=December 2011

An international incident (or diplomatic incident) is a seemingly relatively small or limited action, incident or clash that results in a wider dispute between two or more nation-states. International incidents can ...

and the climax of imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

territorial disputes between Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

, occurring in 1898. A French expedition to Fashoda

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independ ...

on the White Nile river sought to gain control of the Upper Nile river basin and thereby exclude Britain from the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

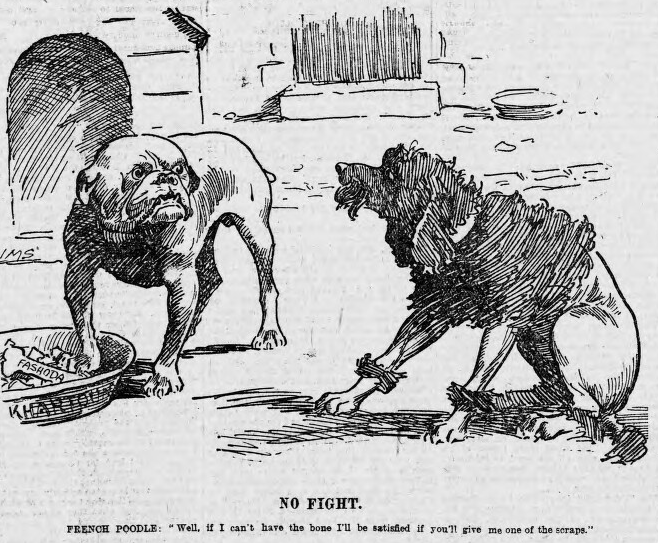

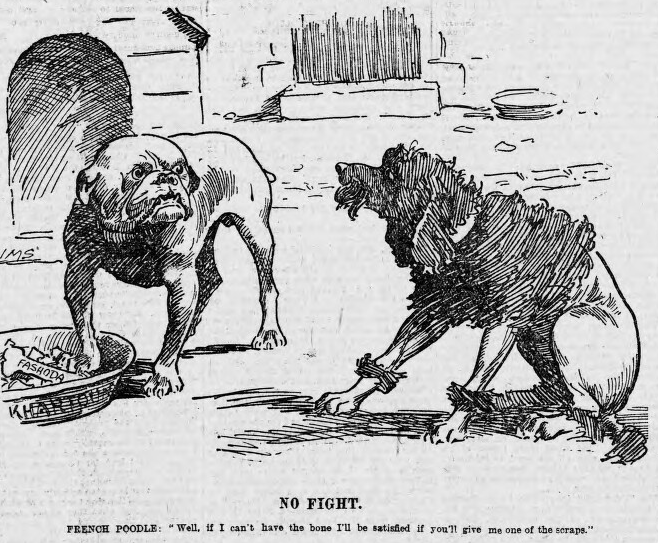

. The French party and a British-Egyptian force (outnumbering the French by 10 to 1) met on friendly terms, but back in Europe, it became a war scare. The British held firm as both empires stood on the verge of war with heated rhetoric on both sides. Under heavy pressure, the French withdrew, ensuring Anglo-Egyptian control over the area.

Background

During the late-19th century, Africa was rapidly being claimed and colonised by European colonial powers. After the 1885

During the late-19th century, Africa was rapidly being claimed and colonised by European colonial powers. After the 1885 Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence ...

regarding West Africa, Europe's great powers went after any remaining lands in Africa that were not already under another European nation's influence. This period in African history

The history of Africa begins with the emergence of hominids, archaic humans and — around 300–250,000 years ago—anatomically modern humans ('' Homo sapiens''), in East Africa, and continues unbroken into the present as a patchwork of d ...

is usually termed the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

by modern historiography. The principal powers involved in this scramble were Britain, France, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

The French thrust into the African interior was mainly from the continent's Atlantic coast (modern-day Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

) eastward, through the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid c ...

along the southern border of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, a territory covering modern-day Senegal, Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

, Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesChad

Chad (; ar, تشاد , ; french: Tchad, ), officially the Republic of Chad, '; ) is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic ...

. Their ultimate goal was to have an uninterrupted link between the Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through ...

and the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

, hence controlling all trade to and from the Sahel region, by virtue of their existing control over the caravan routes through the Sahara. France also had an outpost near the mouth of the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

in Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

(French Somaliland

French Somaliland (french: Côte française des Somalis, lit= French Coast of the Somalis so, Xeebta Soomaaliyeed ee Faransiiska) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which time it became the French Ter ...

), which could serve as an eastern anchor to an east–west belt of French territory across the continent.

The British, on the other hand, wanted to link their possessions in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number of ...

(South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, Bechuanaland and Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

), with their territories in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

(modern-day Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

), and these two areas with the Nile basin. Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

, which then included modern-day South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the C ...

and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

, was the key to the fulfilment of these ambitions, especially since Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

was already under British control. This 'red line' (i.e. a proposed railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

or road, see Cape to Cairo Railway

The Cape to Cairo Railway was an unfinished project to create a railway line crossing Africa from south to north. It would have been the largest and most important railway of that continent. It was planned as a link between Cape Town in Sout ...

) through Africa was made most famous by the British diamond magnate and politician Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

, who wanted Africa "painted Red" (meaning under British control, since territories which were part of Britain were often painted red on maps).

If one draws a line from Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

(Rhodes' dream) and another line from Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

to French Somaliland

French Somaliland (french: Côte française des Somalis, lit= French Coast of the Somalis so, Xeebta Soomaaliyeed ee Faransiiska) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which time it became the French Ter ...

(now Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

) by the Red Sea in the Horn (the French ambition), these two lines intersect in eastern South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the C ...

near the town of Fashoda (present-day Kodok

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independe ...

), explaining its strategic importance. The French east–west axis and the British north–south axis could not co-exist; the nation that could occupy and hold the crossing of the two axes would be the only one able to proceed with its plan.Jones, Jim,The Fashoda Incident

West Chester University, 2014; Web, 12 July 2014; accessed 2019.10.20.

Fashoda had been founded by the Egyptian army in 1855 as base from which to combat the

Fashoda had been founded by the Egyptian army in 1855 as base from which to combat the East African slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the East African slave trade or Arab slave trade, was multi-directional slave trade and has changed over time. Africans were sent as slaves to the Middle East, to Indian Ocean islands (including Ma ...

. It was located on high ground along of marshy shoreline at one of the few places where a boat could unload. The surrounding area, although swampy, was populated by Shilluk people

The Shilluk ( Shilluk: ''Chollo'') are a major Luo Nilotic ethnic group of Southern Sudan, living on both banks of the river Nile, in the vicinity of the city of Malakal. Before the Second Sudanese Civil War the Shilluk also lived in a number of ...

, and by the mid-1870s, Fashoda was a bustling market and administrative town. The first Europeans to arrive in the region were explorers

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

Georg Schweinfurth

Georg August Schweinfurth (29 December 1836 – 19 September 1925) was a Baltic German botanist and ethnologist who explored East Central Africa.

Life and explorations

He was born at Riga, Latvia, then part of the Russian Empire. He was edu ...

in 1869 and Wilhelm Junker

Wilhelm Junker ( rus, Василий Васильевич Юнкер; 6 April 184013 February 1892) was a Russian explorer of Africa. Dr. Junker was of German descent.

Born in Moscow, he studied medicine at Dorpat (now called University of Tart ...

in 1876. Junker described the town as "a considerable trading place ... the last outpost of civilization, where travelers plunging into or returning from the wilds of equatorial Africa could procure a few indispensable European wares from the local Greek traders." By the time Jean-Baptiste Marchand

:''for others with similar names, see Jean Marchand

General Jean-Baptiste Marchand (22 November 1863 – 14 January 1934) was a French military officer and explorer in Africa. Marchand is best known for commanding the French expeditionary ...

arrived, however, the deserted fort was in ruins.

Fashoda was also bound up in the Egyptian Question, a long running dispute between the United Kingdom and France over the British occupation of Egypt

The history of Egypt under the British lasted from 1882, when it was occupied by British forces during the Anglo-Egyptian War, until 1956 after the Suez Crisis, when the last British forces withdrew in accordance with the Anglo-Egyptian agree ...

. Since 1882 many French politicians, particularly those of the ''parti colonial'', had come to regret France's decision not to join with Britain in occupying the country. They hoped to force Britain to leave, and thought that a colonial outpost on the Upper Nile could serve as a base for French gunboats. These in turn were expected to make the British abandon Egypt. Another proposed scheme involved a massive dam, cutting off the Nile's water supply and forcing the British out. These ideas were highly impractical, but they succeeded in alarming many British officials.

Other European nations were also interested in controlling the upper Nile valley. The Italians got a head start from their Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

n outpost at Massawa on the Red Sea, but their defeat by the Ethiopians at Adowa

Adwa ( ti, ዓድዋ; amh, ዐድዋ; also spelled Aduwa) is a town and separate woreda in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. It is best known as the community closest to the site of the 1896 Battle of Adwa, in which Ethiopian soldiers defeated Italian ...

in March 1896 ended their attempt. In September 1896, King Leopold, the official leader of the Congo Free State, dispatched a column of 5,000 Congolese troops, with artillery, towards the White Nile River from Stanleyville on the Upper Congo River. They took five months to reach Lake Albert on the White Nile, about from Fashoda, but by then, their soldiers were so angry at their treatment that they mutinied on 18 March 1897. Many of the Belgian officers were killed and the rest were forced to flee.

Crisis

Marchand expedition

France made its move by sending CaptainJean-Baptiste Marchand

:''for others with similar names, see Jean Marchand

General Jean-Baptiste Marchand (22 November 1863 – 14 January 1934) was a French military officer and explorer in Africa. Marchand is best known for commanding the French expeditionary ...

, a veteran of the conquest of French Sudan

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

, back to West Africa. He embarked a force composed mostly of West African colonial troops from Senegal on a ship for central Africa. On 20 June 1896, he reached Libreville in the colony of Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

with a force of only 120 ''tirailleurs'' plus 12 French officers, non-commissioned officers and support staff—Captain Marcel Joseph Germain, Captain Albert Baratier, Captain Charles Mangin

Charles Emmanuel Marie Mangin (6 July 1866 – 12 May 1925) was a French general during World War I.

Early career

Charles Mangin was born on 6 July 1866 in Sarrebourg. After initially failing to gain entrance to Saint-Cyr, he joined the 77th ...

, Captain Victor Emmanuel Largeau, Lieutenant Félix Fouqué, teacher Dyé, doctor Jules Emily Major, Warrant Officer De Prat, Sergeant George Dat, Sergeant Bernard, Sergeant Venail and the military interpreter Landerouin.Michel Côte, Mission de Bonchamps: ''Vers Fachoda à la rencontre de la mission Marchand à travers l’Ethiopie'', Paris, Plon, 1900.

Marchand's force set out from Brazzaville

Brazzaville (, kg, Kintamo, Nkuna, Kintambo, Ntamo, Mavula, Tandala, Mfwa, Mfua; Teke: ''M'fa'', ''Mfaa'', ''Mfa'', ''Mfoa''Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, ''Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture'', ABC-CLI ...

in a borrowed Belgian steamer with orders to secure the area around Fashoda, and make it a French protectorate. They steamed up the Ubangi River

The Ubangi River (), also spelled Oubangui, is the largest right-bank tributary of the Congo River in the region of Central Africa. It begins at the confluence of the Mbomou (mean annual discharge 1,350 m3/s) and Uele Rivers (mean annual discharge ...

to its head of navigation and then marched overland (carrying 100 tons of supplies, including a collapsible steel steamboat with a one-ton boiler) through jungle and scrub to the deserts of Sudan. They travelled across Sudan to the Nile River. They were to be met there by two expeditions coming from the east across Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, one of which, from Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

, was led by Christian de Bonchamps

The Marquis Christian de Bonchamps (15 June 1860 – 9 December 1919) was a French explorer in Africa and a Colonialism, colonial officer in the French colonial empire, French Empire during the late 19th- early 20th-century epoch known as the ...

, veteran of the Stairs Expedition to Katanga.

Following a difficult 14-month trek across the heart of Africa, the Marchand Expedition arrived on 10 July 1898, but the de Bonchamps Expedition failed to make it after being ordered by the Ethiopians to halt, and then suffering accidents in the Baro Gorge. Marchand's small force thus became isolated and alone. The British, meanwhile, were engaged in the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan

The Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan in 1896–1899 was a reconquest of territory lost by the Khedives of Egypt in 1884 and 1885 during the Mahdist War. The British had failed to organise an orderly withdrawal of Egyptian forces from Sudan, an ...

, moving upriver from Egypt. On 18 September a flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

of five British gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s arrived at the isolated Fashoda fort. They carried 1,500 British, Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers, led by Sir Herbert Kitchener and including Lieutenant-Colonel Horace Smith-Dorrien

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, (26 May 1858 – 12 August 1930) was a British Army General. One of the few British survivors of the Battle of Isandlwana as a young officer, he also distinguished himself in the Second Boer War.

Smit ...

. Marchand had received incorrect reports that the approaching force consisted of Dervishes

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from fa, درویش, ''Darvīsh'') in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity (''tariqah''), or more narrowly to a religious mendicant, who chose or accepted material poverty. The latter usage i ...

but now found himself facing a diplomatic rather than a military crisis.

Standoff at Fashoda

Both sides insisted on their right to Fashoda but agreed to wait for further instructions from home. The two commanders behaved with restraint and even a certain humour. Kitchener toasted Marchand with whisky, the drinking of which the French officer described as "one of the greatest sacrifices I ever made for my country". Kitchener inspected a French garden commenting "Flowers at Fashoda. Oh these Frenchmen!" More seriously the British distributed French newspapers detailing the political chaos caused by the

Both sides insisted on their right to Fashoda but agreed to wait for further instructions from home. The two commanders behaved with restraint and even a certain humour. Kitchener toasted Marchand with whisky, the drinking of which the French officer described as "one of the greatest sacrifices I ever made for my country". Kitchener inspected a French garden commenting "Flowers at Fashoda. Oh these Frenchmen!" More seriously the British distributed French newspapers detailing the political chaos caused by the Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

, warning that France was in no condition to provide serious support for Marchand and his party. News of the meeting was relayed to Paris and London, where it inflamed the pride of both nations. Widespread popular outrage followed, each side accusing the other of naked expansionism and aggression. The crisis continued throughout September and October 1898. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

drafted war orders and mobilized its reserves.

French withdrawal

As the commander of the Anglo-Egyptian army that had just defeated the forces of the

As the commander of the Anglo-Egyptian army that had just defeated the forces of the Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a Messianism, messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a de ...

at the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of the M ...

, Kitchener was in the process of reconquering the Sudan in the name of the Egyptian Khedive, and after the battle he opened sealed orders to investigate the French expedition. Kitchener landed at Fashoda wearing an Egyptian Army uniform

The Egyptian Army uses a British Army Style ceremonial outfit, and a desert camouflage overall implemented in 2012. The Identification between different branches in the Egyptian Army depends on the branch insignia on the left upper arm and the co ...

and insisted in raising the Egyptian flag at some distance from the French flag.

In naval terms, the situation was heavily in Britain's favour, a fact that French deputies acknowledged in the aftermath of the crisis. Several historians have given credit to Marchand for remaining calm. The military facts were undoubtedly important to Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé (1 March 185222 February 1923) was a French politician who served as foreign minister from 1898 to 1905. He is best known for his hatred of Germany and efforts to secure alliances with Russia and Great Britain that became t ...

, the newly appointed French foreign minister. "They have soldiers. We only have arguments," he said resignedly. In addition, he saw no advantage in a war with the British, especially since he was keen to gain their friendship in case of any future conflict with Germany. He therefore pressed hard for a peaceful resolution of the crisis although it encouraged a tide of nationalism and anglophobia. In an editorial published in ''L'Intransigeant

''L'Intransigeant'' was a French newspaper founded in July 1880 by Henri Rochefort. Initially representing the left-wing opposition, it moved towards the right during the Boulanger affair (Rochefort supported Boulanger) and became a major right-wi ...

'' on 13 October Victor Henri Rochefort wrote, "Germany keeps slapping us in the face. Let's not offer our cheek to England." As Professor P. H. Bell writes,

Aftermath

According toFrench nationalists

French nationalism () usually manifests as cultural nationalism, promoting the cultural unity of France.

History

French nationalism emerged from its numerous wars with England, which involved the reconquest of the territories that made up Fra ...

, France's capitulation was clear evidence that the French army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

had been severely weakened by the traitors who supported Dreyfus. Yet the reopening of the Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

in January had done much to distract French public opinion from events in the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and with people increasingly questioning the wisdom of a war over such a remote part of Africa, the French government quietly ordered its soldiers to withdraw on 3 November and the crisis ended peacefully. Marchand chose to withdraw his small force by way of Abyssinia and Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

, rather than cross Egyptian territory by taking the relatively quick journey by steamer down the Nile.

It was a diplomatic victory for the British as the French realized that in the long run they needed the friendship of Britain in case of a war between France and Germany.In March 1899, the

Anglo-French Convention of 1898

The Anglo-French Convention of 1898, full name the ''Convention between Great Britain and France for the Delimitation of their respective Possessions to the West of the Niger, and of their respective Possessions and Spheres of Influence to the East ...

was signed and it was agreed that the source of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

and the Congo rivers should mark the frontier between their spheres of influence.

The Fashoda incident was the last serious colonial dispute between Britain and France, and its classic diplomatic solution is considered by most historians to be the precursor of the Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

of 1904. The two main individuals involved in the incident are commemorated in the Pont Kitchener-Marchand, a road bridge over the Saône, completed in 1959 in the French city of Lyon. In 1904, Fashoda was officially renamed Kodok

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independe ...

. It is located in modern-day South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the C ...

.

Legacy

The incident gave rise to the 'Fashoda syndrome Fashoda syndrome, or a 'Fashoda complex', is the name given to a tendency within French foreign policy in Africa, giving importance to asserting French influence in areas which might be becoming susceptible to British influence. It refers to the Fas ...

' in French foreign policy, or seeking to assert French influence in areas which might be becoming susceptible to British influence. As such it was used as a comparison to other later crises or conflicts such as the Levant Crisis

The Levant Crisis, also known as the Damascus Crisis, the Syrian Crisis, or the Levant Confrontation, was a military confrontation that took place between British and French forces in Syria in May 1945 soon after the end of World War II in Eur ...

of 1945, the Nigerian Civil War

The Nigerian Civil War (6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970), also known as the Nigerian–Biafran War or the Biafran War, was a civil war fought between Nigeria and the Republic of Biafra, a secessionist state which had declared its independence f ...

in Biafra

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised secessionist state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the predominantly Igbo-populated form ...

in the 1970s and the Rwandan Civil War

The Rwandan Civil War was a large-scale civil war in Rwanda which was fought between the Rwandan Armed Forces, representing the country's government, and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) from 1October 1990 to 18 July 1994. The war arose ...

in 1994.

See also

*Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan

The Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan in 1896–1899 was a reconquest of territory lost by the Khedives of Egypt in 1884 and 1885 during the Mahdist War. The British had failed to organise an orderly withdrawal of Egyptian forces from Sudan, an ...

* International relations of the Great Powers

** France–United Kingdom relations

The historical ties between France and the United Kingdom, and the countries preceding them, are long and complex, including conquest, wars, and alliances at various points in history. The Roman era saw both areas largely conquered by Rome, ...

* Pink Map

The Pink Map (, "rose-coloured map"), also known in English as the Rose-Coloured Map, was a map prepared in 1885 to represent Portugal's claim of sovereignty over a land corridor connecting their colonies of Angola and Mozambique during the Scr ...

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* {{Authority control 1898 in Sudan 1898 in the British Empire 1898 in the French colonial empire Battles and conflicts without fatalities British colonisation in Africa Conflicts in 1898 Diplomatic incidents European colonisation in Africa Former French colonies France–United Kingdom relations French colonial empire French colonisation in Africa French Third Republic History of Africa History of Sudan History of the British Empire Military history of Africa War scare