Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the

left–right political spectrum

The left–right political spectrum is a system of classifying political positions characteristic of left-right politics, ideologies and parties with emphasis placed upon issues of social equality and social hierarchy. In addition to position ...

than the standard

political right

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, auth ...

, particularly in terms of being

radically conservative,

ultra-nationalist

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its sp ...

, and

authoritarian, as well as having

nativist ideologies and tendencies.

Historically, "far-right politics" has been used to describe the experiences of

Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

,

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

, and

Falangism

Falangism ( es, falangismo) was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS) and afterwards the Fal ...

. Contemporary definitions now include

neo-fascism

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration s ...

,

neo-Nazism, the

Third Position

The Third Position is a set of neo-fascist political ideologies that were first described in Western Europe following the Second World War. Developed in the context of the Cold War, it developed its name through the claim that it represented a ...

, the

alt-right,

racial supremacism

Supremacism is the belief that a certain group of people is superior to all others. The supposed superior people can be defined by age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, language, social class, ideology, nation, cultu ...

,

National Bolshevism

National Bolshevism (russian: национал-большевизм, natsional-bol'shevizm, german: Nationalbolschewismus), whose supporters are known as National Bolsheviks (russian: национал-большевики, natsional-bol'sheviki ...

(culturally only) and other

ideologies

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied prim ...

or organizations that feature aspects of

authoritarian,

ultra-nationalist

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its sp ...

,

chauvinist,

xenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

,

theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

,

racist,

homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred or antipathy, m ...

,

transphobic

Transphobia is a collection of ideas and phenomena that encompass a range of negative attitudes, feelings, or actions towards transgender people or transness in general. Transphobia can include fear, aversion, hatred, violence or anger tow ...

, and/or

reactionary views.

Far-right politics have led to

oppression

Oppression is malicious or unjust treatment or exercise of power, often under the guise of governmental authority or cultural opprobrium. Oppression may be overt or covert, depending on how it is practiced. Oppression refers to discrimination ...

,

political violence,

forced assimilation

Forced assimilation is an involuntary process of cultural assimilation of religious or ethnic minority groups during which they are forced to adopt language, identity, norms, mores, customs, traditions, values, mentality, perceptions, way of li ...

,

ethnic cleansing, and

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

against groups of people based on their supposed inferiority or their perceived threat to the native

ethnic group,

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective Identity (social science), identity of a group of people unde ...

,

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

,

national religion,

dominant culture

A dominant culture is a cultural practice that is dominant within a particular political, social or economic entity, in which multiple cultures co-exist. It may refer to a language, religion/ritual, social value and/or social custom. These f ...

, or

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

social institutions.

Overview

Concept and worldview

The core of the far right's worldview is

organicism

Organicism is the philosophical position that states that the universe and its various parts (including human societies) ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism.Gilbert, S. F., and S. Sarkar. 2000. "Embrac ...

, the idea that society functions as a complete, organized and homogeneous living being. Adapted to the community they wish to constitute or reconstitute (whether based on ethnicity, nationality, religion or race), the concept leads them to reject every form of

universalism

Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is seen as more far-reaching th ...

in favor of ''

autophilia'' and ''alterophobia'', or in other words the idealization of a "we" excluding a "they". The far right tends to absolutize differences between nations, races, individuals or cultures since they disrupt their efforts towards the

utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island societ ...

n dream of the "closed" and naturally organized society, perceived as the condition to ensure the rebirth of a community finally reconnected to its quasi-eternal nature and re-established on firm

metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

foundations.

As they view their community in a state of decay facilitated by the ruling elites, far-right members portray themselves as a natural, sane and alternative elite, with the redemptive mission of saving society from its promised doom. They reject both their national political system and the global geopolitical order (including their institutions and values, e.g.

political liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and

egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and Agency (philosophy), agency of Human, human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical in ...

) which are presented as needing to be abandoned or purged of their impurities, so that the "redemptive community" can eventually leave the current phase of

liminal crisis to usher in the new era. The community itself is idealized through great

archetypal

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that o ...

figures (the

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

, the savior,

decadence

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members ...

and global

conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

) as they glorify

non-rationalistic and non-

materialistic values such as the youth or the cult of the dead.

Political scientist

Cas Mudde

Cas Mudde (born 3 June 1967) is a Dutch political scientist who focuses on political extremism and populism in Europe and the United States. His research includes the areas of political parties, extremism, democracy, civil society and Europ ...

argues that the far right can be viewed as a combination of four broadly defined concepts, namely

exclusivism

Exclusivism is the practice of being exclusive; mentality characterized by the disregard for opinions and ideas which are different from one's own, or the practice of organizing entities into groups by excluding those entities which possess certa ...

(e.g.

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

,

xenophobia

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

,

ethnocentrism,

ethnopluralism

Ethnopluralism or ethno-pluralism, also known as ethno-differentialism, is a political concept which relies on preserving and mutually respecting separate and bordered ethno-cultural regions. Among the key components are the "right to difference" ( ...

,

chauvinism, or

welfare chauvinism

Welfare chauvinism or welfare state nationalism is the political notion that welfare benefits should be restricted to certain groups, particularly to the natives of a country as opposed to immigrants. It is used as an argumentation strategy by ...

),

anti-democratic and non-individualist traits (e.g.

cult of personality,

hierarchism

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

,

monism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

,

populism,

anti-particracy

Particracy, also known as partitocracy, partitocrazia or partocracy, is a form of government in which the political parties are the primary basis of rule rather than citizens and/or individual politicians.

As argued by Italian political scientis ...

, an

organicist

Organicism is the philosophical position that states that the universe and its various parts (including human societies) ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism.Gilbert, S. F., and S. Sarkar. 2000. "Embra ...

view of the state), a

traditionalist value system lamenting the disappearance of historic frames of reference (e.g.

law and order

In modern politics, law and order is the approach focusing on harsher enforcement and penalties as ways to reduce crime. Penalties for perpetrators of disorder may include longer terms of imprisonment, mandatory sentencing, three-strikes laws a ...

, the family, the ethnic, linguistic and religious community and nation as well as the

natural environment

The natural environment or natural world encompasses all living and non-living things occurring naturally, meaning in this case not artificial. The term is most often applied to the Earth or some parts of Earth. This environment encompasses ...

) and a socioeconomic program associating

corporatism

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

, state control of certain sectors,

agrarianism and a varying degree of belief in the free play of

socially Darwinistic

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

market forces. Mudde then proposes a subdivision of the far-right nebula into moderate and radical leanings, according to their degree of exclusionism and

essentialism.

Definition and comparative analysis

The ''Encyclopedia of Politics: The Left and the Right'' states that far-right politics include "persons or groups who hold extreme nationalist, xenophobic, racist, religious fundamentalist, or other reactionary views." While the term ''far right'' is typically applied to

fascists and

neo-Nazis

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy (often white supremacy), attack ...

, it has also been used to refer to those to the right of mainstream

right-wing politics

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, author ...

.

According to political scientist Lubomír Kopeček, "

e best working definition of the contemporary far right may be the four-element combination of nationalism, xenophobia, law and order, and welfare chauvinism proposed for the Western European environment by Cas Mudde."

Relying on those concepts, far-right politics includes yet is not limited to aspects of

authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

,

anti-communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

and

nativism.

[Hilliard, Robert L. and Michael C. Keith, ''Waves of Rancor: Tuning in the Radical Right'' (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe 1999, p. 43.] Claims that superior people should have greater rights than inferior people are often associated with the far right, as they have historically favored a social Darwinistic or

elitist

Elitism is the belief or notion that individuals who form an elite—a select group of people perceived as having an intrinsic quality, high intellect, wealth, power, notability, special skills, or experience—are more likely to be construc ...

hierarchy based on the belief in the legitimacy of the rule of a supposed superior minority over the inferior masses. Regarding the socio-cultural dimension of nationality, culture and migration, one far-right position is the view that certain ethnic, racial or religious groups should stay separate, based on the belief that the interests of one's own group should be prioritized.

[Widfeldt, Anders, "A fourth phase of the extreme right? Nordic immigration-critical parties in a comparative context". In: ''NORDEUROPAforum'' (2010:1/2), 7–31]

Edoc.hu

/ref>

In western Europe, far right parties have been associated with anti-immigrant

Opposition to immigration, also known as anti-immigration, has become a significant political ideology in many countries. In the modern sense, immigration refers to the entry of people from one state or territory into another state or territory ...

policies, as well as globalism and European integration. They often make nationalist and xenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

appeals which make allusions to Ethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnocratic) approach to various politi ...

rather than Civic nationalism (aka liberal nationalism). Some have at their core illiberal policies such as removing checks on checks on executive authority and protections for minorities from majority ( multipluralism). In the 1990s, the "winning formula" was often to attract anti-immigrant blue collar workers and white collar workers who wanted less state intervention in the economy, but in the 2000s, this switched to welfare chauvinism

Welfare chauvinism or welfare state nationalism is the political notion that welfare benefits should be restricted to certain groups, particularly to the natives of a country as opposed to immigrants. It is used as an argumentation strategy by ...

.post-Communist

Post-communism is the period of political and economic transformation or transition in former communist states located in Eastern Europe and parts of Africa and Asia in which new governments aimed to create free market-oriented capitalist economi ...

Central European far-right, Kopeček writes that " e Central European far right was also typified by a strong anti-Communism, much more markedly than in Western Europe", allowing for "a basic ideological classification within a unified party family, despite the heterogeneity of the far right parties." Kopeček concludes that a comparison of Central European far-right parties with those of Western Europe shows that "these four elements are present in Central Europe as well, though in a somewhat modified form, despite differing political, economic, and social influences."hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

was said to have developed into the post-World War II combination of ultranationalism and anti-communism, Christian fundamentalism, militaristic orientation, and anti-alien sentiment."

Jodi Dean

Jodi Dean (born April 9, 1962) is an American political theorist and professor in the Political Science department at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in New York state. She held the Donald R. Harter ’39 Professorship of the Humanities and So ...

argues that "the rise of far-right anti-communism in many parts of the world" should be interpreted "as a politics of fear, which utilizes the disaffection and anger generated by capitalism. ..Partisans of far right-wing organizations, in turn, use anti-communism to challenge every political current which is not embedded in a clearly exposed nationalist and racist agenda. For them, both the USSR and the European Union, leftist liberals, ecologists, and supranational corporationsall of these may be called 'communist' for the sake of their expediency."antidemocratic

Criticism of democracy has been a key part of democracy and its functions. As Josiah Ober explains, "the Legitimacy (political), legitimate role of critics" of democracy may be difficult to define, but one "approach is to divide critics into 'g ...

, antiegalitarian, white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

" beliefs that are "embedded in solutions like authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

, ethnic cleansing or ethnic migration, and the establishment of separate ethno-states or enclaves along racial and ethnic lines".

Modern debates

Terminology

According to Jean-Yves Camus

Jean-Yves Camus (born 1958) is a French political scientist who specializes on nationalist movements in Europe.

Life and career

Born in 1958 to a Catholic and Gaullist family, Camus is an observant Jew and describes himself as part of "the an ...

and Nicolas Lebourg, the modern ambiguities in the definition of far-right politics lie in the fact that the concept is generally used by political adversaries to "disqualify and stigmatize all forms of partisan nationalism by reducing them to the historical experiments of Italian Fascism ndGerman National Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

." Mudde agrees and notes that "the term is not only used for scientific purposes but also for political purposes. Several authors define right-wing extremism as a sort of anti-thesis against their own beliefs." While the existence of such a political position is widely accepted among scholars, figures associated with the far-right rarely accept this denomination, preferring terms like "national movement" or "national right". There is also debate about how appropriate the labels neo-fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration s ...

or neo-Nazi are. In the words of Mudde, "the labels Neo-Nazi and to a lesser extent neo-Fascism are now used exclusively for parties and groups that explicitly state a desire to restore the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

or quote historical National Socialism as their ideological influence."

One issue is whether parties should be labelled radical or extreme, a distinction that is made by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany

The Federal Constitutional Court (german: link=no, Bundesverfassungsgericht ; abbreviated: ) is the supreme constitutional court for the Federal Republic of Germany, established by the constitution or Basic Law () of Germany. Since its in ...

when determining whether or not a party should be banned. Within the broader family of the far right, the extreme right is revolutionary, opposing popular sovereignty and majority rule, and sometimes supporting violence, whereas the radical right is reformist, accepting free elections, but opposing fundamental elements of liberal democracy such as minority rights, rule of law, or separation of powers.

After a survey of the academic literature, Mudde concluded in 2002 that the terms "right-wing extremism", " right-wing populism", "national populism", or "neo-populism" were often used as synonyms by scholars, in any case with "striking similarities", except notably among a few authors studying the extremist-theoretical tradition.

Relation to right-wing politics

Italian philosopher and political scientist Norberto Bobbio

Norberto Bobbio (; 18 October 1909 – 9 January 2004) was an Italian philosopher of law and political sciences and a historian of political thought. He also wrote regularly for the Turin-based daily ''La Stampa''.

Bobbio was a social libe ...

argues that attitudes towards equality are primarily what distinguish left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soc ...

from right-wing politics

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, author ...

on the political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more geometric axes that represent independent political dimensions. The expressions politi ...

: "the left considers the key inequalities between people to be artificial and negative, which should be overcome by an active state, whereas the right believes that inequalities between people are natural and positive, and should be either defended or left alone by the state."

Aspects of far-right ideology can be identified in the agenda of some contemporary right-wing parties: in particular, the idea that superior persons should dominate society while undesirable elements should be purged, which in extreme cases has resulted in genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

s. Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform The Centre for European Reform (CER) is a London-based think tank that focuses on matters of European integration. It is a prominent source of ideas and commentary in debates about a wide range of EU-related issues, both in the United Kingdom and in ...

in London, distinguishes between fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

and right-wing nationalist parties which are often described as far right such as the National Front in France.Mark Sedgwick

Mark J. Sedgwick (born 20 July 1960) is a British historian specialising in the study of traditionalism, Islam, Sufi mysticism, and terrorism. He is Professor of Arab and Islamic Studies at Aarhus University in Denmark and chair of the Nordic S ...

, " ere is no general agreement as to where the mainstream ends and the extreme starts, and if there ever had been agreement on this, the recent shift in the mainstream would challenge it."

Proponents of the horseshoe theory

In political science and popular discourse, the horseshoe theory asserts that the extreme left and the extreme right, rather than being at opposite and opposing ends of a linear political continuum, closely resemble each other, analogous to t ...

interpretation of the Left–right political spectrum

The left–right political spectrum is a system of classifying political positions characteristic of left-right politics, ideologies and parties with emphasis placed upon issues of social equality and social hierarchy. In addition to position ...

identify the far left and the far right as having more in common with each other as extremists

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered (by the speaker or by some implied shar ...

than each of them has with centrists

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to Left-w ...

or moderate

Moderate is an ideological category which designates a rejection of radical or extreme views, especially in regard to politics and religion. A moderate is considered someone occupying any mainstream position avoiding extreme views. In American ...

s. However, the horseshoe theory does not enjoy support within academic circles

Nature of support

Jens Rydgren Jens Rydgren (born 1969) is a Swedish writer, political commentator and a professor of sociology, at Stockholm University. Specialising in research of political sociology, for many years he has studied populist right-wing parties. In 2002 he defen ...

describes a number of theories as to why individuals support far-right political parties and the academic literature on this topic distinguishes between demand-side theories that have changed the "interests, emotions, attitudes and preferences of voters" and supply-side theories which focus on the programmes of parties, their organization and the opportunity structures within individual political systems. The most common demand-side theories are the social breakdown thesis

The social breakdown thesis (also known as the anomie–social breakdown thesis)Fella, S. and Ruzza, C. (2009) ''Reinventing the Italian Right: Territorial politics, populism and post-fascism, Abingdon: Routledge'', p 215 is a theory that posits ...

, the relative deprivation thesis

Relative deprivation is the lack of resources to sustain the diet, lifestyle, activities and amenities that an individual or group are accustomed to or that are widely encouraged or approved in the society to which they belong. Peter Townsend, ''Po ...

, the modernization losers thesis The modernization losers thesis, or modernization losers theory, is a theory associated with the academic Hans-Georg Betz that posits that individuals support far-right political parties because they wish to undo changes associated with moderniza ...

and the ethnic competition thesis The ethnic competition thesis, also known as ethnic competition theory or ethnic competition hypothesis, is an academic theory that posits that individuals support far-right political parties because they wish to reduce competition from immigrants ...

.

The rise of far-right parties has also been viewed as a rejection of post-materialist values on the part of some voters. This theory which is known as the reverse post-material thesis

The reverse post-material thesis or reverse post-materialism thesis is an academic theory used to explain support for far-right political parties and right-wing populist political parties. The thesis is modelled on the post-material thesis from ...

blames both left-wing and progressive parties for embracing a post-material agenda (including feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

and environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seeks ...

) that alienates traditional working class voters. Another study argues that individuals who join far-right parties determine whether those parties develop into major political players or whether they remain marginalized.

Early academic studies adopted psychoanalytical explanations for the far right's support. The 1933 publication ''The Mass Psychology of Fascism

''The Mass Psychology of Fascism'' (german: Die Massenpsychologie des Faschismus) is a 1933 psychology book written by the Austrian psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich, in which the author attempts to explain how fascists and authoritari ...

'' by Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( , ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian doctor of medicine and a psychoanalyst, along with being a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several influential books, most ...

argued the theory that fascists came to power in Germany as a result of sexual repression

Sexual repression is a state in which a person is prevented from expressing their own sexuality. Sexual repression is often linked with feelings of guilt or shame being associated with sexual impulses. Defining characteristics and practices ass ...

. For some far-right parties in Western Europe, the issue of immigration has become the dominant issue among them, so much so that some scholars refer to these parties as "anti-immigrant" parties.

Intellectual history

Background

The French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

in 1789 created a major shift in political thought by challenging the established ideas supporting hierarchy with new ones about universal equality

Equality may refer to:

Society

* Political equality, in which all members of a society are of equal standing

** Consociationalism, in which an ethnically, religiously, or linguistically divided state functions by cooperation of each group's elit ...

and freedom. The modern left–right political spectrum

The left–right political spectrum is a system of classifying political positions characteristic of left-right politics, ideologies and parties with emphasis placed upon issues of social equality and social hierarchy. In addition to position ...

also emerged during this period. Democrats and proponents of universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

were located on the left side of the elected French Assembly, while monarchists seated farthest to the right.

The strongest opponents of liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

during the 19th century, such as Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (; 1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, and diplomat who advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immediately following the French Revolution. Despite his clo ...

and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, were highly critical of the French Revolution. Those who advocated a return to the absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism (European history), Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute pow ...

during the 19th century called themselves "ultra-monarchists" and embraced a " mystic" and " providentialist" vision of the world where royal dynasties were seen as the "repositories of divine will". The opposition to liberal modernity was based on the belief that hierarchy and rootedness are more important than equality and liberty, with the latter two being dehumanizing.

Emergence

In the French public debate following the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

of 1917, ''far right'' was used to describe the strongest opponents of the '' far left'', those who supported the events occurring in Russia. A number of thinkers on the far right nonetheless claimed an influence from an anti-Marxist and anti-egalitarian definition of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

, based on a military comradeship that rejected Marxist class analysis

Class analysis is research in sociology, politics and economics from the point of view of the stratification of the society into dynamic classes. It implies that there is no universal or uniform social outlook, rather that there are fundamental c ...

, or what Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best kno ...

had called a "socialism of the blood", which is sometimes described by scholars as a form of " socialist revisionism".Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (; ; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, politician, poet, and critic. He was an organizer and principal philosopher of ''Action Française'', a political movement that is monarchist, anti-par ...

, Benito Mussolini, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck

Arthur Wilhelm Ernst Victor Moeller van den Bruck (23 April 1876 – 30 May 1925) was a German cultural historian, philosopher and writer best known for his controversial 1923 book '' Das Dritte Reich'' ("The Third Reich"), which promoted Germ ...

and Ernst Niekisch

Ernst Niekisch (23 May 1889 – 23 May 1967) was a German writer and politician. Initially a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he later became a prominent exponent of National Bolshevism.

Early life

Born in Trebnitz (Silesia), and b ...

.communist movement

The history of communism encompasses a wide variety of ideologies and political movements sharing the core theoretical values of common ownership of wealth, economic enterprise, and property. Most modern forms of communism are grounded at least ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,["Engels"](_blank)

'' nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

theories with the idea that "the working men adno country." The main reason for that ideological confusion can be found in the consequences of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which according to Swiss historian had completely redesigned the political landscape in Europe by diffusing the idea of an anti-individualistic concept of "national unity" rising above the right and left division.

As the concept of "the masses" was introduced into the political debate through industrialization and the universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

, a new right-wing founded on national and social ideas began to emerge, what Zeev Sternhell

Zeev Sternhell ( he, זאב שטרנהל; 10 April 1935 – 21 June 2020) was a Polish-born Israeli historian, political scientist, commentator on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and writer. He was one of the world's leading theorists of the ...

has called the "revolutionary right" and a foreshadowing of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. The rift between the left and nationalists was furthermore accentuated by the emergence of anti-militarist and anti-patriotic movements like anarchism or syndicalism

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

, which shared even less similarities with the far right. The latter began to develop a "nationalist mysticism" entirely different from that on the left, and antisemitism turned into a credo of the far right, marking a break from the traditional economic "anti-Judaism" defended by parts of the far left, in favour of a racial and pseudo-scientific notion of alterity

Alterity is a philosophical and anthropological term meaning "otherness", that is, the "other of two" (Latin ''alter''). It is also increasingly being used in media to express something other than "sameness", or something outside of tradition or co ...

. Various nationalist leagues began to form across Europe like the Pan-German League or the Ligue des Patriotes, with the common goal of a uniting the masses beyond social divisions.

''Völkisch'' and revolutionary right

The ''Völkisch'' movement emerged in the late 19th century, drawing inspiration from German Romanticism and its fascination for a medieval Reich supposedly organized into a harmonious hierarchical order. Erected on the idea of " blood and soil", it was a racialist,

The ''Völkisch'' movement emerged in the late 19th century, drawing inspiration from German Romanticism and its fascination for a medieval Reich supposedly organized into a harmonious hierarchical order. Erected on the idea of " blood and soil", it was a racialist, populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

, agrarian, romantic nationalist

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

and an antisemitic movement from the 1900s onward as a consequence of a growing exclusive and racial connotation. They idealized the myth of an "original nation", that still could be found at their times in the rural regions of Germany, a form of "primitive democracy freely subjected to their natural elites."Arthur de Gobineau

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau (; 14 July 1816 – 13 October 1882) was a French aristocrat who is best known for helping to legitimise racism by the use of scientific racist theory and "racial demography", and for developing the theory of the Ary ...

, Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (; 9 September 1855 – 9 January 1927) was a British-German philosopher who wrote works about political philosophy and natural science. His writing promoted German ethnonationalism, antisemitism, and scientific ...

, Alexis Carrel

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques. He invented the first perfusion pump with Charl ...

and Georges Vacher de Lapouge

Count Georges Vacher de Lapouge (; 12 December 1854 – 20 February 1936) was a French anthropologist and a theoretician of eugenics and racialism. He is known as the founder of anthroposociology, the anthropological and sociological study of race ...

distorted Darwin's theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variatio ...

to advocate a "race struggle" and an hygienist vision of the world. The purity of the bio-mystical and primordial nation theorized by the ''Völkischen'' then began to be seen as corrupted by foreign elements, Jewish in particular.

Translated in Maurice Barrès' concept of "the earth and the dead", these ideas influenced the pre-fascist "revolutionary right" across Europe. The latter had its origin in the ''fin de siècle

() is a French term meaning "end of century,” a phrase which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom "turn of the century" and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of another. Without context, ...

'' intellectual crisis and it was, in the words of Fritz Stern

Fritz Richard Stern (February 2, 1926 – May 18, 2016) was a German-born American historian of German history, Jewish history and historiography. He was a University Professor and a provost at New York's Columbia University. His work focused ...

, the deep "cultural despair" of thinkers feeling uprooted within the rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

and scientism of the modern world.palingenesis

Palingenesis (; also palingenesia) is a concept of rebirth or re-creation, used in various contexts in philosophy, theology, politics, and biology. Its meaning stems from Greek , meaning 'again', and , meaning 'birth'.

In biology, it is anothe ...

("regeneration, rebirth").

Contemporary thought

The key thinkers of contemporary far-right politics are claimed by Mark Sedgwick

Mark J. Sedgwick (born 20 July 1960) is a British historian specialising in the study of traditionalism, Islam, Sufi mysticism, and terrorism. He is Professor of Arab and Islamic Studies at Aarhus University in Denmark and chair of the Nordic S ...

to share four key elements, namely apocalyptism, fear of global elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (french: élite, from la, eligere, to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. D ...

s, belief in Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (; 11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and prominent member of the Nazi Party. Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. A conservative theorist, he is noted as ...

's friend-enemy distinction and the idea of metapolitics

Metapolitics (sometimes written meta-politics) is metalinguistic talk about politics; a political dialogue about politics itself. In this mode, metapolitics takes on various forms of inquiry, appropriating to itself another way toward the discourse ...

. The apocalyptic strain of thought begins in Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best kno ...

's ''The Decline of the West

''The Decline of the West'' (german: Der Untergang des Abendlandes; more literally, ''The Downfall of the Occident''), is a two-volume work by Oswald Spengler. The first volume, subtitled ''Form and Actuality'', was published in the summer of 19 ...

'' and is shared by Julius Evola

Giulio Cesare Andrea "Julius" Evola (; 19 May 1898 – 11 June 1974) was an Italian philosopher, poet, painter, esotericist, and radical-right ideologue. Evola regarded his values as aristocratic, masculine, traditionalist, heroic, and defiant ...

and Alain de Benoist

Alain de Benoist (; ; born 11 December 1943) – also known as Fabrice Laroche, Robert de Herte, David Barney, and other pen names – is a French journalist and political philosopher, a founding member of the Nouvelle Droite ("New Right"), and ...

. It continues in ''The Death of the West

''The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization'' is a 2001 book by paleoconservative commentator Patrick J. Buchanan, in which the author argues that western culture is dying and will ...

'' by Pat Buchanan as well as in the fears of Islamization of Europe

Islam is the second-largest religion in Europe after Christianity. Although the majority of Muslim communities in Western Europe formed recently, there are centuries-old Muslim societies in the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Volga region. The t ...

. Related to it is the fear of global elites, who are seen as responsible for the decline. Ernst Jünger

Ernst Jünger (; 29 March 1895 – 17 February 1998) was a German author, highly decorated soldier, philosopher, and entomologist who became publicly known for his World War I memoir '' Storm of Steel''.

The son of a successful businessman and ...

was concerned about rootless cosmopolitan

Rootless cosmopolitan () was a pejorative Soviet epithet which referred mostly to Jewish intellectuals as an accusation of their lack of allegiance to the Soviet Union, especially during the antisemitic campaign of 1948–1953. This campaign ...

elites while de Benoist and Buchanan oppose the managerial state

The managerial state is a concept used in critiquing modern procedural democracy. The concept is used largely, though not exclusively, in paleolibertarian, paleoconservative, and anarcho-capitalist critiques of late modern state power in Weste ...

and Curtis Yarvin

Curtis Guy Yarvin (born 1973), also known by the pen name Mencius Moldbug, is an American blogger, software engineer, and Internet entrepreneur. He is known, along with fellow theorist Nick Land, for founding the anti-egalitarian and anti-dem ...

is against "the Cathedral". Schmitt's friend-enemy distinction has inspired the French Nouvelle Droite

The Nouvelle Droite (; en, "New Right"), sometimes shortened to the initialism ND, is a far-right political movement which emerged in France during the late 1960s. The Nouvelle Droite is at the origin of the wider European New Right (ENR). Vario ...

idea of ethnopluralism

Ethnopluralism or ethno-pluralism, also known as ethno-differentialism, is a political concept which relies on preserving and mutually respecting separate and bordered ethno-cultural regions. Among the key components are the "right to difference" ( ...

which has become highly influential on the alt-right when combined with American racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonis ...

.  In a 1961 book deemed influential in the European far-right at large, French neo-fascist writer

In a 1961 book deemed influential in the European far-right at large, French neo-fascist writer Maurice Bardèche

Maurice Bardèche (1 October 1907 – 30 July 1998) was a French art critic and journalist, better known as one of the leading exponents of neo-fascism in post–World War II Europe. Bardèche was also the brother-in-law of the collaborationist ...

introduced the idea that fascism could survive the 20th century under a new metapolitical

Metapolitics (sometimes written meta-politics) is metalinguistic talk about politics; a political dialogue about politics itself. In this mode, metapolitics takes on various forms of inquiry, appropriating to itself another way toward the discourse ...

guise adapted to the changes of the times. Rather than trying to revive doomed regimes with their single party

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

, secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of ...

or public display of Caesarism

Caesarism is an authoritarian or autocratic political philosophy inspired by Julius Caesar. It has been used in various ways by both proponents and opponents as a pejorative.

Historical use of the term

The first documented use of the word is ...

, Bardèche argued that its theorists should promote the core philosophical idea of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

regardless of its framework, i.e. the concept that only a minority, "the physically saner, the morally purer, the most conscious of national interest", can represent best the community and serve the less gifted in what Bardèche calls a new " feudal contract".

Another influence on contemporary far-right thought has been the Traditionalist School

The Traditionalist or Perennialist School is a group of 20th- and 21st-century thinkers who believe in the existence of a perennial wisdom or perennial philosophy, primordial and universal truths which form the source for, and are shared by, al ...

which included Julius Evola

Giulio Cesare Andrea "Julius" Evola (; 19 May 1898 – 11 June 1974) was an Italian philosopher, poet, painter, esotericist, and radical-right ideologue. Evola regarded his values as aristocratic, masculine, traditionalist, heroic, and defiant ...

and has influenced Steve Bannon

Stephen Kevin Bannon (born November 27, 1953) is an American media executive, political strategist, and former investment banker. He served as the White House's chief strategist in the administration of U.S. president Donald Trump during t ...

and Aleksandr Dugin

Aleksandr Gelyevich Dugin ( rus, Александр Гельевич Дугин; born 7 January 1962) is a Russian political philosopher, analyst, and strategist, who has been widely characterized as a fascist.

Born into a military intelligen ...

, advisors to Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

and Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

as well as the Jobbik

The Movement for a Better Hungary ( hu, Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom), commonly known as Jobbik (), is a conservative political party in Hungary.

Originating with radical and nationalist roots, at its beginnings, the party described itself ...

party in Hungary.

Regarding Latin America, Dr. Rene Leal of the University of Santiago, Chile

The University of Santiago, Chile (Usach) ( es, Universidad de Santiago de Chile) is one of the oldest public universities in Chile. The institution was born as ''Escuela de Artes y Oficios'' (Spanish: ''School of Arts and Crafts'') in 1849 by Ig ...

notes that the oppressive exploitation of labor under neoliberal governments in the region precipitated the growth of far-right politics in the region.

International organizations

During the rise of Nazi Germany, far-right international organizations began to emerge in the 1930s with the International Conference of Fascist Parties in 1932 and the Fascist International Congress in 1934.

During the rise of Nazi Germany, far-right international organizations began to emerge in the 1930s with the International Conference of Fascist Parties in 1932 and the Fascist International Congress in 1934.Fascist Regime

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

to create a network for a "Fascist International", representatives from far-right groups gathered in Montreux

Montreux (, , ; frp, Montrolx) is a Swiss municipality and town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Alps. It belongs to the district of Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland, and has a population of approxima ...

, Switzerland, including Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

's Iron Guard, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

's Nasjonal Samling

Nasjonal Samling (, NS; ) was a Norwegian far-right political party active from 1933 to 1945. It was the only legal party of Norway from 1942 to 1945. It was founded by former minister of defence Vidkun Quisling and a group of supporters such ...

, the Greek National Socialist Party

The Greek National Socialist Party ( el, Ελληνικό Εθνικό Σοσιαλιστικό Κόμμα, Elliniko Ethniko Sosialistiko Komma) was a Nazi party founded in Greece in 1932 by George S. Mercouris, a former Cabinet minister.

Histor ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

's Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco ...

movement, Ireland's Blueshirts

The Army Comrades Association (ACA), later the National Guard, then Young Ireland and finally League of Youth, but best known by the nickname the Blueshirts ( ga, Na Léinte Gorma), was a paramilitary organisation in the Irish Free State, founded ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

's '' Mouvement Franciste and'' Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

's União Nacional

The National Union ( pt, União Nacional) was the sole legal party of the Estado Novo regime in Portugal, founded in July 1930 and dominated by António de Oliveira Salazar during most of its existence.

Unlike in most single-party regimes, ...

, among others.[ Payne, Stanley G. "Fascist Italy and Spain, 1922–1945". ''Spain and the Mediterranean Since 1898'', Raanan Rein, ed. p. 105. London, 1999] However, no international group was fully established before the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.Nouvel Ordre Européen

The New European Order (NEO) was a neo-fascist, Europe-wide alliance set up in 1951 to promote pan-European nationalism. The NEO, led by René Binet and Gaston-Armand Amaudruz, was a more radical splinter group that broke away from the European S ...

, European Social Movement

The European Social Movement (German: ''Europäische soziale Bewegung'', ESB) was a neo-fascist Europe-wide alliance set up in 1951 to promote pan-European nationalism.

History

The ESB had its origins in the emergence of the Italian Social Move ...

and Circulo Español de Amigos de Europa

CEDADE (from the initials of ''Círculo Español de Amigos de Europa'' or 'Spanish Circle of Friends of Europe') was a Spanish neo-Nazi group that concerned itself with co-ordinating international activity and publishing.

History

The group began l ...

or the further-reaching World Union of National Socialists

The World Union of National Socialists (WUNS) is an organisation founded in 1962 as an umbrella group for neo-Nazi organisations across the globe.

History Formation

The movement came about when the leader of the American Nazi Party, Geor ...

and the League for Pan-Nordic Friendship.European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

in 1993, far-right groups began to espouse Euroscepticism

Euroscepticism, also spelled as Euroskepticism or EU-scepticism, is a political position involving criticism of the European Union (EU) and European integration. It ranges from those who oppose some EU institutions and policies, and seek refor ...

, nationalist and anti-migrant beliefs.European Alliance for Freedom

The European Alliance for Freedom (EAF) was a pan- European political party of right-wing Eurosceptics. It was founded in late 2010, the party was recognised by the European Parliament in 2011. It did not seek registration as a political party ...

emerged and saw some prominence during the 2014 European Parliament election

The 2014 European Parliament election was held in the European Union, from 22 to 25 May 2014.

It was the 8th parliamentary election since the first direct elections in 1979, and the first in which the European political parties fielded candid ...

.Steve Bannon

Stephen Kevin Bannon (born November 27, 1953) is an American media executive, political strategist, and former investment banker. He served as the White House's chief strategist in the administration of U.S. president Donald Trump during t ...

would create The Movement

The Movement may refer to:

Politics

* The Movement (Iceland), a political party in Iceland

* The Movement (Israel), a political party in Israel, led by Tzipi Livni

* Civil rights movement, the African-American political movement

* The Movemen ...

, an organization to create an international far-right group based on Aleksandr Dugin

Aleksandr Gelyevich Dugin ( rus, Александр Гельевич Дугин; born 7 January 1962) is a Russian political philosopher, analyst, and strategist, who has been widely characterized as a fascist.

Born into a military intelligen ...

's '' The Fourth Political Theory'', for the 2019 European Parliament election

The 2019 European Parliament election was held between 23 and 26 May 2019, the ninth parliamentary election since the first direct elections in 1979. A total of 751 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) represent more than 512 million peop ...

.Identity and Democracy

Identity and Democracy (french: link=no, Identité et démocratie, ID) is a right-wing to far-right political group of the European Parliament, launched on 13 June 2019 for the Ninth European Parliament term. It is composed of nationalist, ri ...

for the 2019 European Parliament election.Madrid Charter

The ''Madrid Charter: In Defense of Freedom and Democracy in the Iberosphere'' ( Spanish: ''Carta de Madrid: en defensa de la libertad y la democracia en la Iberosfera''), also known as the ''Letter from Madrid'', was a manifesto created on 26 O ...

project, a planned group to denounce left-wing groups in Ibero-America

Ibero-America ( es, Iberoamérica, pt, Ibero-América) or Iberian America is a region in the Americas comprising countries or territories where Spanish or Portuguese are predominant languages (usually former territories of Portugal or Spain). ...

, to the government of United States president Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

while visiting the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

in February 2019, with Santiago Abascal

Santiago Abascal Conde (; born 14 April 1976) is a Spanish politician and since September 2014 the leader of the national-conservative political party Vox. Abascal is a member of the Congress of Deputies representing Madrid since 2019. Before ...

and Rafael Bardají

Rafael Luis Bardají López (born Badajoz, 1959) is a Spanish author, sociologist and former national security advisor to the Spanish government who researches the fields of neoconservatism and international politics. He was the founder of the ''G ...

using their good relations with the administration to build support within the Republican Party and establishing strong ties with American contacts.ABC

ABC are the first three letters of the Latin script known as the alphabet.

ABC or abc may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Broadcasting

* American Broadcasting Company, a commercial U.S. TV broadcaster

** Disney–ABC Television ...

'' writing in an article detailing the document that this event provided a narrative that "symbolizes in part the expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

mood of Vox and its ideology far from Spain".Javier Milei

Javier Gerardo Milei (born 22 October 1970) is an Argentine politician, businessman and economist currently serving as a federal deputy of Buenos Aires.

Milei became widely known for his regular television appearances where he has been critical ...

in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, the Bolsonaro family

Jair Messias Bolsonaro (; born 21 March 1955) is a Brazilian politician and retired military officer who has been the 38th president of Brazil since 1 January 2019. He was 2018 Brazilian general election, elected in 2018 as a member of the Soci ...

in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, José Antonio Kast

José Antonio Kast Rist (born 18 January 1966), also known by his initials JAK, is a Chilean lawyer and politician. Kast ran for president in 2021, winning the first round and losing in the second round run-off to Gabriel Boric.

Part of the ...

in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

and Keiko Fujimori

Keiko Sofía Fujimori Higuchi (; ja, 藤森 恵子, Fujimori Keiko; born 25 May 1975) is a Peruvian politician. Fujimori is the eldest daughter of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori and Susana Higuchi. From August 1994 to November 200 ...

in Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

.

Nationalists from Europe and the United States met at a Holiday Inn in St. Petersburg on March 22, 2015 for first convention of the International Russian Conservative Forum organized by pro-Putin Rodina-party. The event was attended by frige right-wing extremists like Nordic Resistance Movement

The Nordic Resistance Movement; Norwegian: nb, Nordiske motstandsbevegelsen, NMB; nn, Nordiske motstandsrørsla NMR; fi, Pohjoismainen Vastarintaliike, PVL; is, Norræna mótstöðuhreyfingin, NMH; da, Den nordiske modstandsbevægelse, ...

from Scandinavia but also by more mainstream MEPs

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its ...

from Golden Dawn and National Democratic Party of Germany

The National Democratic Party of Germany (german: Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands or NPD) is a far-right Neo-Nazi and ultranationalist political party in Germany.

The party was founded in 1964 as successor to the German Reich Part ...

. In addition to Rodina, Russian neo-Nazis from Russian Imperial Movement

The Russian Imperial Movement (RIM; russian: Русское Имперское Движениe, translit=Russkoe imperskoe dvizhenie, RID)Marlene Laruelle, ''Russian Nationalism: Imaginaries, Doctrines, and Political Battlefields'' (Routledge, 2 ...

and Rusich Group

The Sabotage Assault Reconnaissance Group (DShRG) "Rusich" (russian: Диверсионно-штурмовая разведывательная группа «Русич», Diversionno-shturmovaya razvedyvatel'naya gruppa «Rusich») is a combat d ...

were also in attendance. From the US the event was attended by Jared Taylor

Samuel Jared Taylor (born September 15, 1951) is an American white supremacist and editor of ''American Renaissance'', an online magazine espousing such opinions, which was founded by Taylor in 1990.

He is also the president of ''American Ren ...

and Brandon Russell

Brandon Clint Russell is a Bahamian American Neo-Nazi leader and the founder of the Atomwaffen Division.

Creation of Atomwaffen

Russell, who went by the handle " Odin", first appeared on the Iron March on March 22, 2014, at age 18. Iron March wa ...

.

History by country

Africa

Rwanda

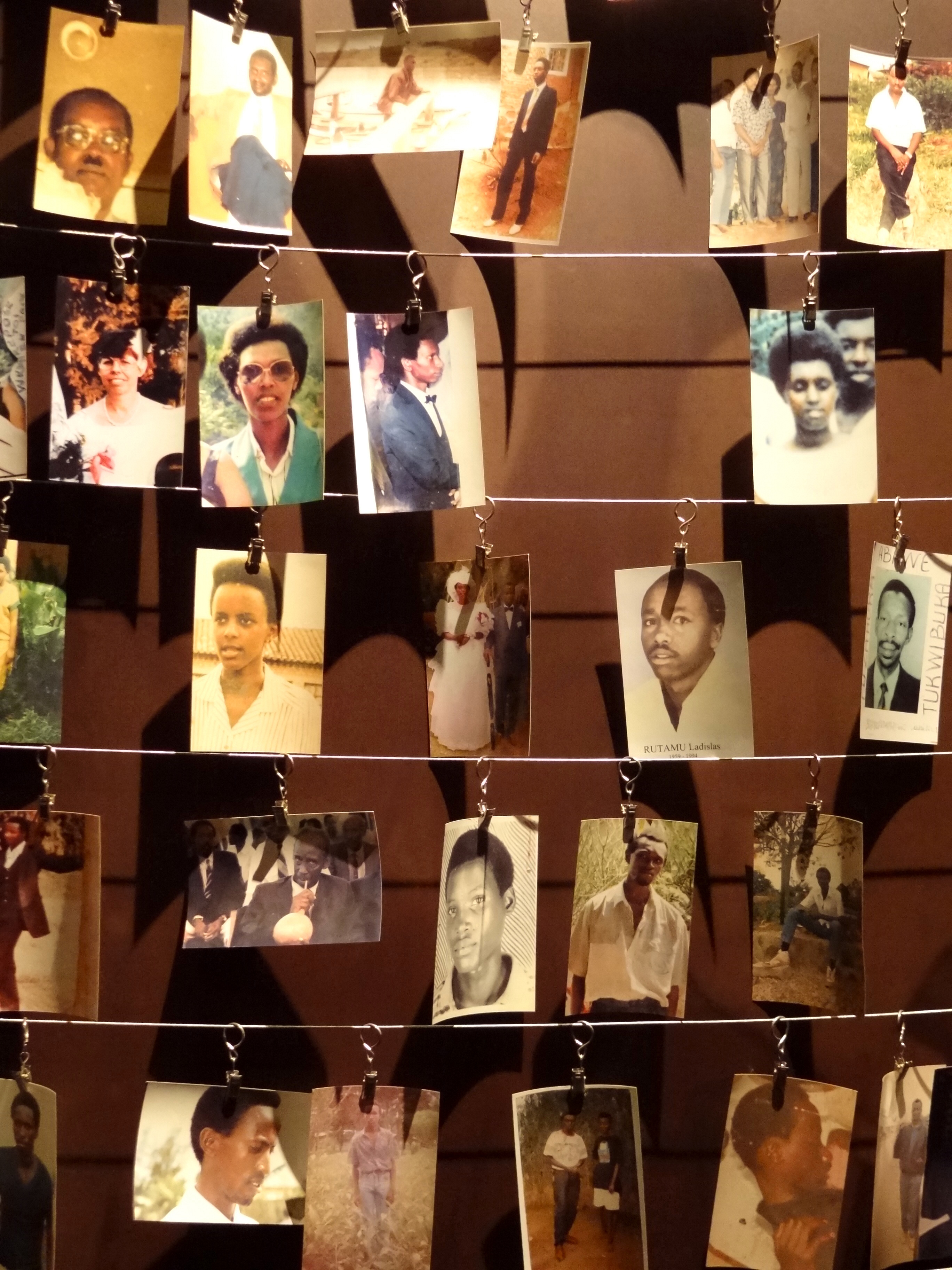

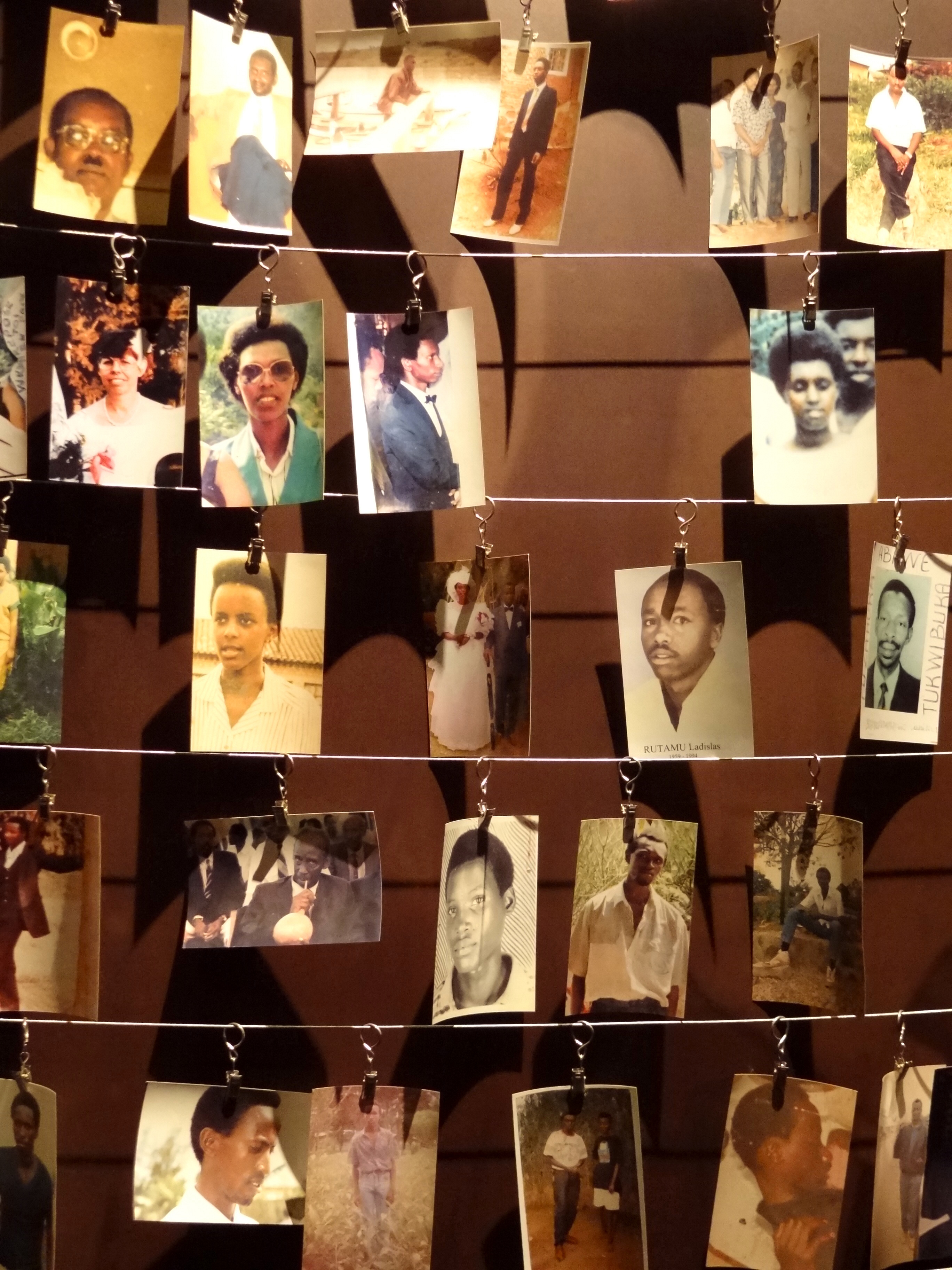

A number of far-right extremist and paramilitary groups carried out the

A number of far-right extremist and paramilitary groups carried out the Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed H ...

under the racial supremacist

Supremacism is the belief that a certain group of people is superior to all others. The supposed superior people can be defined by age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, language, social class, ideology, nation, cultu ...

ideology of Hutu Power, developed by journalist and Hutu supremacist Hassan Ngeze

Hassan Ngeze (born 25 December 1957) is a Rwandan journalist and convicted war criminal best known for spreading anti-Tutsi propaganda and Hutu superiority through his newspaper, ''Kangura'', which he founded in 1990. Ngeze was a founding member ...

.1973 Rwandan coup d'état

The 1973 Rwandan coup d'état, also known as the Coup d'état of 5 July (french: Coup d'état du 5 Juillet), was a military coup staged by Juvénal Habyarimana against incumbent president Grégoire Kayibanda in the Republic of Rwanda. The coup ...

, the far right National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) was founded under president Juvénal Habyarimana

Juvénal Habyarimana (, ; 8 March 19376 April 1994) was a Rwandan politician and military officer who served as the second president of Rwanda, from 1973 until 1994. He was nicknamed ''Kinani'', a Kinyarwanda word meaning "invincible".

An ethn ...

. Between 1975 and 1991, the MRND was the only legal political party in the country. It was dominated by Hutu

The Hutu (), also known as the Abahutu, are a Bantu ethnic or social group which is native to the African Great Lakes region. They mainly live in Rwanda, Burundi and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where they form one of the p ...

s, particularly from Habyarimana's home region of Northern Rwanda. An elite group of MRND party members who were known to have influence on the President and his wife Agathe Habyarimana are known as the akazu, an informal organization of Hutu extremists whose members planned and lead the 1994 Rwandan genocide.Félicien Kabuga