Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained

bird of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predat ...

. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person involved in falconry: a "falconer" flies a

falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Adult falcons ...

; an "austringer" (

Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

origin) flies a

hawk (''

Accipiter

''Accipiter'' is a genus of birds of prey in the family Accipitridae. With 51 recognized species it is the most diverse genus in its family. Most species are called goshawks or sparrowhawks, although almost all New World species (excepting th ...

'', some

buteo

''Buteo'' is a genus of medium to fairly large, wide-ranging raptors with a robust body and broad wings. In the Old World, members of this genus are called "buzzards", but " hawk" is used in the New World (Etymology: ''Buteo'' is the Latin na ...

s and similar) or an

eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

(''

Aquila'' or similar). In modern falconry, the

red-tailed hawk

The red-tailed hawk (''Buteo jamaicensis'') is a bird of prey that breeds throughout most of North America, from the interior of Alaska and northern Canada to as far south as Panama and the West Indies. It is one of the most common members wit ...

(''Buteo jamaicensis''),

Harris's hawk

The Harris's hawk (''Parabuteo unicinctus''), formerly known as the bay-winged hawk, dusky hawk, and sometimes a wolf hawk, and known in Latin America as peuco, is a medium-large bird of prey that breeds from the southwestern United States south ...

(''Parabuteo unicinctus''), and the

peregrine falcon (''Falco perigrinus'') are some of the more commonly used birds of prey. The practice of hunting with a conditioned falconry bird is also called "hawking" or "gamehawking", although the words

hawking

Hawking may refer to:

People

* Stephen Hawking (1942–2018), English theoretical physicist and cosmologist

* Hawking (surname), a family name (including a list of other persons with the name)

Film

* ''Hawking'' (2004 film), about Stephen Ha ...

and

hawker

Hawker or Hawkers may refer to:

Places

* Hawker, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb of Canberra

* Hawker, South Australia, a town

* Division of Hawker, an Electoral Division in South Australia

* Hawker Island, Princess Elizabeth Land, Antarct ...

have become used so much to refer to petty traveling traders, that the terms "falconer" and "falconry" now apply to most use of trained birds of prey to catch game. Many contemporary practitioners still use these words in their original meaning, however.

In early English falconry literature, the word "falcon" referred to a female peregrine falcon only, while the word "hawk" or "hawke" referred to a female hawk. A male hawk or falcon was referred to as a "tiercel" (sometimes spelled "tercel"), as it was roughly one-third less than the female in size.

[.][.] This traditional Arabian sport grew throughout Europe. Falconry is an icon of Emirati and Arab culture.

History

Evidence suggests that the art of falconry may have begun in

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, with the earliest accounts dating to around 2,000 BC. Also, some raptor representations are in the northern

Altai, western Mongolia.

The falcon was a

symbolic bird of ancient Mongol tribes. Some disagreement exists about whether such early accounts document the practice of falconry (from the ''

Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh ...

'' and others) or are misinterpreted depictions of humans with birds of prey. During the Turkic Period of Central Asia (seventh century AD), concrete figures of falconers on horseback were described on the rocks in Kyrgyz.

Falconry was probably introduced to Europe around AD 400, when the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

and

Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the Al ...

invaded from the east.

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen

Frederick II (German: ''Friedrich''; Italian: ''Federico''; Latin: ''Federicus''; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusal ...

(1194–1250) is generally acknowledged as the most significant wellspring of traditional falconry knowledge. He is believed to have obtained firsthand knowledge of Arabic falconry during wars in the region (between June 1228 and June 1229). He obtained a copy of

Moamyn

Moamyn (or Moamin) was the name given in Medieval Europe to an Arabic author of a five-chapter treatise on falconry, important for early Europeans, which was most popular as translated by the Syriac Theodore of Antioch under the title ''De Scienti ...

's manual on falconry and had it translated into Latin by Theodore of Antioch.

Frederick II himself made corrections to the translation in 1241, resulting in ''De Scientia Venandi per Aves''.

[.] King Frederick II is most recognized for his falconry treatise, ''

De arte venandi cum avibus

''De Arte Venandi cum Avibus'', literally ''On The Art of Hunting with Birds'', is a Latin treatise on ornithology and falconry written in the 1240s by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. One of the surviving manuscripts is dedicated to his son ...

'' (''The Art of Hunting with Birds''). Written himself toward the end of his life, it is widely accepted as the first comprehensive book of falconry, but also notable in its contributions to

ornithology

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

and

zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

. ''De arte venandi cum avibus'' incorporated a diversity of scholarly traditions from east to west, and is one of the earliest challenges to

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

's explanations of nature.

Historically, falconry was a popular sport and status symbol among the

nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteri ...

of

medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

,

[15 Let's play Age of Empires IV. Falconry & Hawking: Norman Nobility.](_blank)

/ref> and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

. Many historical illustrations left in Rashid al Din's "Compendium chronicles" book described falconry of the middle centuries with Mongol images. Falconry was largely restricted to the noble classes due to the prerequisite commitment of time, money, and space. In art and other aspects of culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

, such as literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

, falconry remained a status symbol long after it was no longer popularly practiced. The historical significance of falconry within lower social classes may be underrepresented in the archaeological record

The archaeological record is the body of physical (not written) evidence about the past. It is one of the core concepts in archaeology, the academic discipline concerned with documenting and interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeological t ...

, due to a lack of surviving evidence, especially from nonliterate nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

ic and nonagrarian societies

An agrarian society, or agricultural society, is any community whose economy is based on producing and maintaining crops and farmland. Another way to define an agrarian society is by seeing how much of a nation's total production is in agriculture ...

. Within nomadic societies such as the Bedouin, falconry was not practiced for recreation by noblemen. Instead, falcons were trapped and hunted on small game during the winter to supplement a very limited diet.

In the UK and parts of Europe, falconry probably reached its zenith in the 17th century,radio telemetry

Telemetry is the in situ collection of measurements or other data at remote points and their automatic transmission to receiving equipment (telecommunication) for monitoring. The word is derived from the Greek roots ''tele'', "remote", and ' ...

(transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna (radio), antenna. The transmitter itself generates a radio frequency alternating current, which i ...

s attached to free-flying birds) increased the average lifespan of falconry birds, and allowed falconers to pursue quarry and styles of flight that had previously resulted in the loss of their hawk or falcon.

Timeline

* 722–705 BC – An

* 722–705 BC – An Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

found in the ruins at Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; ar, دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mo ...

during the excavation of the palace of Sargon II (Sargon II) has been claimed to depict falconry. In fact, it depicts an archer shooting at raptors and an attendant capturing a raptor. A. H. Layard's statement in his 1853 book ''Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

'' is "A falconer bearing a hawk on his wrist appeared to be represented in a bas-relief which I saw on my last visit to those ruins."

* 680 BC – Chinese records describe falconry.

* Fourth century BC - Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

wrote that in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, the boys who want to hunt small birds, take hawks with them. When they call the hawks addressing them by name, the hawks swoop down on the birds. The small birds fly in terror into the bushes, where the boys catch them by knocking them down with sticks; in case the hawks themselves catch any of the birds, they throw them down to the hunters. When the hunting finishes, the hunters give a portion of all that is caught to the hawks. He also wrote that in the city of Cedripolis (Κεδρίπολις), men and hawks jointly hunt small birds. The men drive them away with sticks, while the hawks pursue closely, and the small birds in their flight fall into the clutches of the men. Because of this, they share their prey with the hawks.

* Third century BC - Antigonus of Carystus Antigonus of Carystus (; grc, Ἀντίγονος ὁ Καρύστιος; la, Antigonus Carystius), Greek writer on various subjects, flourished in the 3rd century BCE. After some time spent at Athens and in travelling, he was summoned to the co ...

wrote the same story about the city of Cedripolis.

* 355 AD – '' Nihon-shoki'', a largely mythical narrative, records hawking first arriving in Japan from Baekje

Baekje or Paekche (, ) was a Korean kingdom located in southwestern Korea from 18 BC to 660 AD. It was one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, together with Goguryeo and Silla.

Baekje was founded by Onjo, the third son of Goguryeo's founder Jum ...

as of the 16th emperor Nintoku.

* Second–fourth century – the Germanic tribe of the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

learned falconry from the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic peoples of classical ant ...

.

* Fifth century – the son of Avitus

Eparchius Avitus (c. 390 – 457) was Roman emperor of the West from July 455 to October 456. He was a senator of Gallic extraction and a high-ranking officer both in the civil and military administration, as well as Bishop of Piacenza.

He o ...

, Roman Emperor 455– 56, from the Celtic tribe of the Arverni, who fought at the Battle of Châlons

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Roman general ...

with the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

against the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, introduced falconry in Rome.

* 500 – a Roman floor mosaic depicts a falconer and his hawk hunting duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form ...

s.

* Early seventh century – Prey caught by trained dogs or falcons is considered halal

''Halal'' (; ar, حلال, ) is an Arabic word that translates to "permissible" in English. In the Quran, the word ''halal'' is contrasted with ''haram'' (forbidden). This binary opposition was elaborated into a more complex classification kno ...

in Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

. By this time, falconry was already popular in the Arabian Peninsula.

* 818 – Japanese Emperor Saga

was the 52nd emperor of Japan, Emperor Saga, Saganoyamanoe Imperial Mausoleum, Imperial Household Agency according to the traditional order of succession. Saga's reign spanned the years from 809 through 823.

Traditional narrative

Saga was the ...

ordered someone to edit a falconry text named ''Shinshuu Youkyou''.

* 875 – Western Europe and Saxon England practiced falconry widely.

* 991 – In the poem ''The Battle of Maldon

"The Battle of Maldon" is the name given to an Old English poem of uncertain date celebrating the real Battle of Maldon of 991, at which an Anglo-Saxon army failed to repulse a Viking raid. Only 325 lines of the poem are extant; both the beginni ...

'' describing the Battle of Maldon

The Battle of Maldon took place on 11 August 991 AD near Maldon beside the River Blackwater in Essex, England, during the reign of Æthelred the Unready. Earl Byrhtnoth and his thegns led the English against a Viking invasion. The battl ...

in Essex, before the battle, the Anglo-Saxons' leader Byrhtnoth

Byrhtnoth ( ang, Byrhtnoð), Ealdorman of Essex ( 931 - 11 August 991), died at the Battle of Maldon. His name is composed of the Old English ''beorht'' (bright) and ''noþ'' (courage). He is the subject of '' The Battle of Maldon'', an Old ...

says, "let his tame hawk fly from his hand to the wood".

* 1070s – The Bayeux Tapestry shows King Harold of England with a hawk in one scene. The king is said to have owned the largest collection of books on the sport in all of Europe.

* 1100 – Norman nobility distinguished falconry from the sport

Sport pertains to any form of Competition, competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and Skill, skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to specta ...

of 'hawking'.Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

practiced falconry by horseback and 'hawking' by foot.Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

.

* Around the 1240s – The treatise of an Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

falconer, Moamyn, was translated into Latin by Master Theodore of Antioch, at the court of Frederick II, it was called ''De Scientia Venandi per Aves'' and much copied.

* 1250 – Frederick II wrote in the last years of his life a treatise on the art of hunting with birds: ''De arte venandi cum avibus''.

* 1285 – The ''Baz-Nama-yi Nasiri'', a Persian treatise on falconry, was compiled by Taymur Mirza, an English translation of which was produced in 1908 by D. C. Phillott.

* 1325 – The ''Libro de la caza'', by the prince of Villena

Villena () is a city in Spain, in the Valencian Community. It is located at the northwest part of Alicante, and borders to the west with Castilla-La Mancha and Murcia, to the north with the province of Valencia and to the east and south with the ...

, Don Juan Manuel

Don Juan Manuel (5 May 128213 June 1348) was a Spanish medieval writer, nephew of Alfonso X of Castile, son of Manuel of Castile and Beatrice of Savoy. He inherited from his father the great Lordship of Villena, receiving the titles of Lord, D ...

, includes a detailed description of the best hunting places for falconry in the kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th cent ...

.

* 1390s – In his ''Libro de la caza de las aves'', Castilian poet and chronicler Pero López de Ayala

Don Pero (or Pedro) López de Ayala (1332–1407) was a Castilian statesman, historian, poet, chronicler, chancellor, and courtier.

Life

Pero López de Ayala was born in 1332 at Vitoria, County of Alava, Kingdom of Castile, as the son of Fe ...

attempts to compile all the available correct knowledge concerning falconry.

* 1486 – See the '' Boke of Saint Albans''

* Early 16th century – Japanese warlord Asakura Norikage

, also known as Asakura Sōteki (朝倉 宗滴), was a Japanese samurai warrior of the latter Sengoku Period. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"Asakura Norikage"in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 50. from Asakura clan

The is a Japanese kin group. Pa ...

(1476–1555) succeeded in captive breeding of goshawk

Goshawk may refer to several species of birds of prey, mainly in the genus ''Accipiter'':

* Northern goshawk, ''Accipiter gentilis'', often referred to simply as the goshawk, since it is the only goshawk found in much of its range (in Europe and N ...

s.

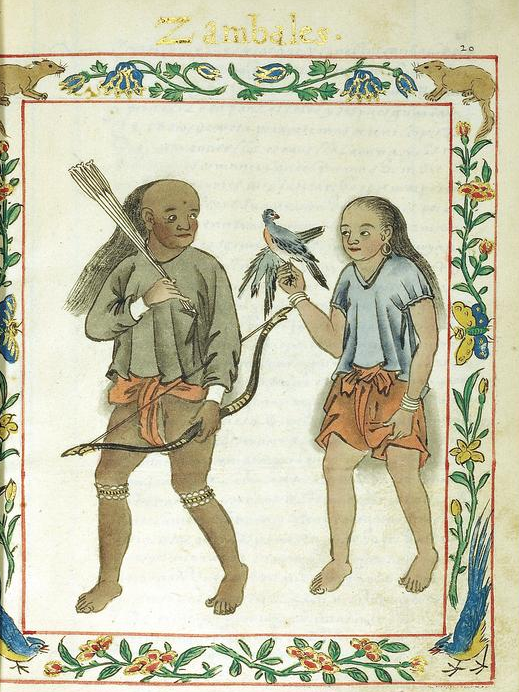

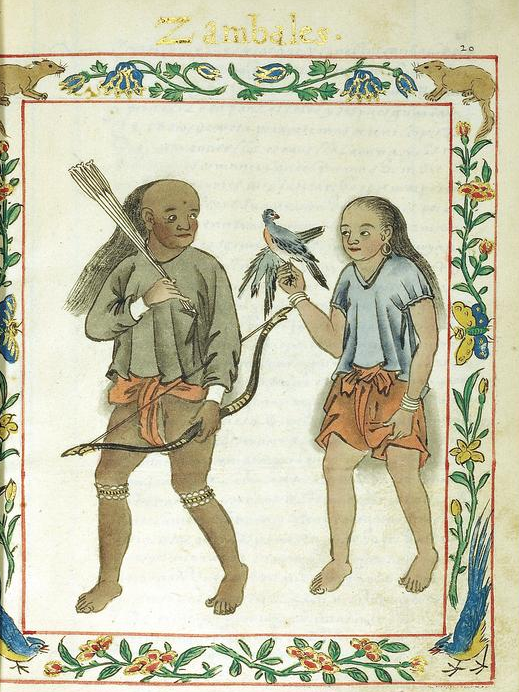

* 1580s – Spanish drawings of Sambal people recorded in the ''Boxer Codex'' showed a culture of falconry in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

.

* 1600s – In Dutch records of falconry, the town of Valkenswaard

Valkenswaard () is a municipality and a town in the southern Netherlands, in the Metropoolregio Eindhoven of the province of North Brabant. The municipality had a population of in and spans an area of of which is water.

The name Valkenswaard ...

was almost entirely dependent on falconry for its economy.

* 1660s – Tsar Alexis

Aleksey Mikhaylovich ( rus, Алексе́й Миха́йлович, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ; – ) was the Tsar of Russia from 1645 until his death in 1676. While finding success in foreign affairs, his reign saw several wars ...

of Russia writes a treatise that celebrates aesthetic pleasures derived from falconry.

* 1801 – Joseph Strutt of England writes, "the ladies not only accompanied the gentlemen in pursuit of the diversion alconry but often practiced it by themselves; and even excelled the men in knowledge and exercise of the art."

* 1864 – The Old Hawking Club is formed in Great Britain.

* 1921 – Deutscher Falkenorden is founded in Germany. Today, it is the largest and oldest falconry club in Europe.

* 1927 – The British Falconers' Club is founded by the surviving members of the Old Hawking Club.

* 1934 – The first US falconry club, the Peregrine Club of Philadelphia, is formed; it became inactive during World War II and was reconstituted in 2013 by Dwight A. Lasure of Pennsylvania.

* 1941 – Falconer's Club of America formed

* 1961 – Falconer's Club of America was defunct

* 1961 – North American Falconers Association The North American Falconers Association (NAFA) is a falconry organization composed primarily of falconers.

Founded in 1961 by Hal Webster, Frank Beebe

Frank Lyman Beebe (1914 – 15 November 2008) was a falconer, writer and wildlife illustrat ...

formed

* 1968 – International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey formed

* 1970 – Peregrine falcons were listed as an endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

in the U.S., due primarily to the use of DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound, an organochloride. Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. ...

as a pesticide (35 Federal Register 8495; June 2, 1970).

* 1970 – The Peregrine Fund is founded, mostly by falconers, to conserve raptors, and focusing on peregrine falcons.

* 1972 – DDT banned in the U.S. (EPA press release – December 31, 1972) but continues to be used in Mexico and other nations.

* 1999 – Peregrine falcon removed from the Endangered Species List in the United States, due to reports that at least 1,650 peregrine breeding pairs existed in the U.S. and Canada at that time. (64 Federal Register 46541-558, August 25, 1999)

* 2003 – A population study by the USFWS shows peregrine falcon numbers climbing ever more rapidly, with well over 3000 pairs in North America * 2006 – A population study by the USFWS shows peregrine falcon numbers still climbing. (Federal Register circa September 2006)

* 2008 – USFWS rewrites falconry regulations virtually eliminating federal involvement.

* 2010 – Falconry is added to the by the (UNESCO)

* 2006 – A population study by the USFWS shows peregrine falcon numbers still climbing. (Federal Register circa September 2006)

* 2008 – USFWS rewrites falconry regulations virtually eliminating federal involvement.

* 2010 – Falconry is added to the by the (UNESCO)

Falconry in

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

in Early 12th century

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

distinguished falconry from the sport

Sport pertains to any form of Competition, competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and Skill, skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to specta ...

of 'hawking'.Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

practiced falconry by horseback and 'hawking' by foot.Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

was a penchant for falconry enjoyed by Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

.outlawed

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

commoners from hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

particular lands so that nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

could freely enjoy both sports

Sport pertains to any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators. Sports can, th ...

.Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

cultural identity in medieval times

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire an ...

.Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

transported their falcons on a frame called a cadge

Begging (also panhandling) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a beggar or panhandler. Beggars may operate in public plac ...

.

The ''Book of St Albans''

The often-quoted ''Book of Saint Albans

''The Book of Saint Albans'' (or ''Boke of Seynt Albans'') is the common title of a book printed in 1486 that is a compilation of matters relating to the interests of the time of a gentleman. It was the last of eight books printed by the St Alb ...

'' or ''Boke of St Albans'', first printed in 1486, often attributed to Dame Juliana Berners

Juliana Berners, O.S.B., (or Barnes or Bernes) (born 1388), was an English writer on heraldry, hawking and hunting, and is said to have been prioress of the Priory of St Mary of Sopwell, near St Albans in Hertfordshire.

Life and Work

Very lit ...

, provides this hierarchy of hawks and the social rank

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, incom ...

s for which each bird was supposedly appropriate.

# Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

: Eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

, vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

, and merlin

# King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

: gyr falcon

The gyrfalcon ( or ) (), the largest of the falcon species, is a bird of prey. The abbreviation gyr is also used. It breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, and the islands of northern North America and the Eurosiberian region. It is mainly a reside ...

and the tercel of the gyr falcon

The gyrfalcon ( or ) (), the largest of the falcon species, is a bird of prey. The abbreviation gyr is also used. It breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, and the islands of northern North America and the Eurosiberian region. It is mainly a reside ...

# Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

: falcon gentle and the tercel gentle

# Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ran ...

: falcon of the loch

''Loch'' () is the Scottish Gaelic, Scots language, Scots and Irish language, Irish word for a lake or sea inlet. It is Cognate, cognate with the Manx language, Manx lough, Cornish language, Cornish logh, and one of the Welsh language, Welsh w ...

# Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

: Peregrine falcon

# Baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

: bustard

Bustards, including floricans and korhaans, are large, terrestrial birds living mainly in dry grassland areas and on the steppes of the Old World. They range in length from . They make up the family Otididae (, formerly known as Otidae). Bustar ...

# Knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

: sacre and the sacret

# Esquire

Esquire (, ; abbreviated Esq.) is usually a courtesy title.

In the United Kingdom, ''esquire'' historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentlema ...

: lanere and the laneret

# Lady: marlyon

# Young man: hobby

A hobby is considered to be a regular activity that is done for enjoyment, typically during one's leisure time. Hobbies include collecting themed items and objects, engaging in creative and artistic pursuits, playing Sport, sports, or pursu ...

# Yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

: goshawk

Goshawk may refer to several species of birds of prey, mainly in the genus ''Accipiter'':

* Northern goshawk, ''Accipiter gentilis'', often referred to simply as the goshawk, since it is the only goshawk found in much of its range (in Europe and N ...

# Poor man: tercel

# Priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

: sparrowhawk

Sparrowhawk (sometimes sparrow hawk) may refer to several species of small hawk in the genus ''Accipiter''. "Sparrow-hawk" or sparhawk originally referred to ''Accipiter nisus'', now called "Eurasian" or "northern" sparrowhawk to distinguish it f ...

# Holy water clerk: musket

# Knave or servant: kestrel

The term kestrel (from french: crécerelle, derivative from , i.e. ratchet) is the common name given to several species of predatory birds from the falcon genus ''Falco''. Kestrels are most easily distinguished by their typical hunting behaviou ...

This list, however, was mistaken in several respects.

* 1) Vultures are not used for falconry.

* 3) 4) 5) These are usually said to be different names for the peregrine falcon. But there is an opinion that renders 4) as "rock falcon" = a peregrine from remote rocky areas, which would be bigger and stronger than other peregrines. This could also refer to the Scottish peregrine.

* 6) The bustard

Bustards, including floricans and korhaans, are large, terrestrial birds living mainly in dry grassland areas and on the steppes of the Old World. They range in length from . They make up the family Otididae (, formerly known as Otidae). Bustar ...

is not a bird of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predat ...

, but a game

A game is a structured form of play (activity), play, usually undertaken for enjoyment, entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator s ...

species that was commonly hunted by falconers; this entry may have been a mistake for buzzard

Buzzard is the common name of several species of birds of prey.

''Buteo'' species

* Archer's buzzard (''Buteo archeri'')

* Augur buzzard (''Buteo augur'')

* Broad-winged hawk (''Buteo platypterus'')

* Common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'')

* Eastern ...

, or for ''busard'' which is French for " harrier"; but any of these would be a poor deal for baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

s; some treat this entry as "bastard hawk", possibly meaning a hawk of unknown lineage, or a hawk that could not be identified.

* 7) Sakers were imported from abroad and very expensive, and ordinary knights and squires would be unlikely to have them.

* 8) Contemporary records have lanners as native to England.

* 10) 15) Hobbies and kestrels are historically considered to be of little use for serious falconry (the French name for the hobby is ''faucon hobereau'', ''hobereau'' meaning ''local/country squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as a ...

''. That may be the source of the confusion), however King Edward I of England sent a falconer to catch hobbies for his use. Kestrels are coming into their own as worthy hunting birds, as modern falconers dedicate more time to their specific style of hunting. While not suitable for catching game for the falconer's table, kestrels are certainly capable of catching enough quarry that they can be fed on surplus kills through the molt.

* 12) An opinion holds that since the previous entry is the goshawk, this entry ("Ther is a Tercell. And that is for the powere poorman.") means a male goshawk and that here "poor man" means not a labourer or beggar, but someone at the bottom of the scale of landowners.

The relevance of the "Boke" to practical falconry past or present is extremely tenuous, and veteran British falconer Phillip Glasier dismissed it as "merely a formalised and rather fanciful listing of birds".

Falconry in Britain in 1973

A book about falconry published in 1973 says:

* Most falconry birds used in Britain were taken from the wild, either in Britain, or taken abroad and then imported.

* Captive breeding was initiated. The book mentions a captive-bred goshawk

Goshawk may refer to several species of birds of prey, mainly in the genus ''Accipiter'':

* Northern goshawk, ''Accipiter gentilis'', often referred to simply as the goshawk, since it is the only goshawk found in much of its range (in Europe and N ...

and a brood of captive-bred red-tailed hawk

The red-tailed hawk (''Buteo jamaicensis'') is a bird of prey that breeds throughout most of North America, from the interior of Alaska and northern Canada to as far south as Panama and the West Indies. It is one of the most common members wit ...

s. It describes as a new and remarkable event captive breeding hybrid young in 1971 and 1972 from John Morris's female saker

Saker may refer to:

* Saker falcon (''Falco cherrug''), a species of falcon

* Saker (cannon), a type of cannon

* Saker Baptist College, an all-girls secondary school in Limbe, Cameroon

* Grupo Saker-Ti, a Guatemalan writers group formed in 1947

* ...

and Ronald Stevens's peregrine falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Adult falcons ...

.

* Peregrine falcons were suffering from the post–World War II severe decline caused by pesticide

Pesticides are substances that are meant to control pests. This includes herbicide, insecticide, nematicide, molluscicide, piscicide, avicide, rodenticide, bactericide, insect repellent, animal repellent, microbicide, fungicide, and lampri ...

s. Taking wild peregrines in Britain was only allowed to train them to keep birds off Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

airfields to prevent bird strike

A bird strike—sometimes called birdstrike, bird ingestion (for an engine), bird hit, or bird aircraft strike hazard (BASH)—is a collision between an airborne animal (usually a bird or bat) and a moving vehicle, usually an aircraft. The term ...

s.

* The book does not mention telemetry

Telemetry is the in situ data collection, collection of measurements or other data at remote points and their automatic data transmission, transmission to receiving equipment (telecommunication) for monitoring. The word is derived from the Gr ...

.

* Harris hawks were known to falconers but unusual. For example, the book lists a falconry meet on four days in August 1971 at White Hill and Leafield in Dumfriesshire

Dumfriesshire or the County of Dumfries or Shire of Dumfries (''Siorrachd Dhùn Phris'' in Gaelic) is a historic county and registration county in southern Scotland. The Dumfries lieutenancy area covers a similar area to the historic county.

I ...

in Scotland; the hawks flown were 11 goshawks and one Harris hawk. The book felt it necessary to say what a Harris hawk is.

* The usual species for a beginner was a kestrel

The term kestrel (from french: crécerelle, derivative from , i.e. ratchet) is the common name given to several species of predatory birds from the falcon genus ''Falco''. Kestrels are most easily distinguished by their typical hunting behaviou ...

.

* A few falconers used golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of p ...

s.

* Falcons in falconry would have bells on their legs so the hunters could find them. If the bells fell off the falcon, the hunter would not be able to find his bird easily. The bird usually died if it could not find a way to remove the leather binding on its feet.

Birds used in contemporary falconry

Several raptors are used in falconry. They are typically classed as:

* "Broadwings": ''Buteo

''Buteo'' is a genus of medium to fairly large, wide-ranging raptors with a robust body and broad wings. In the Old World, members of this genus are called "buzzards", but " hawk" is used in the New World (Etymology: ''Buteo'' is the Latin na ...

and Parabuteo'' spp., and eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

s (red-tailed hawks, Harris hawks, golden eagles)

* "Shortwings": ''Accipiter

''Accipiter'' is a genus of birds of prey in the family Accipitridae. With 51 recognized species it is the most diverse genus in its family. Most species are called goshawks or sparrowhawks, although almost all New World species (excepting th ...

'' (Cooper's hawk

Cooper's hawk (''Accipiter cooperii'') is a medium-sized hawk native to the North American continent and found from southern Canada to Mexico. This species is a member of the genus ''Accipiter'', sometimes referred to as true hawks, which are f ...

, goshawk

Goshawk may refer to several species of birds of prey, mainly in the genus ''Accipiter'':

* Northern goshawk, ''Accipiter gentilis'', often referred to simply as the goshawk, since it is the only goshawk found in much of its range (in Europe and N ...

s, sparrow hawk

Sparrowhawk (sometimes sparrow hawk) may refer to several species of small hawk in the genus ''Accipiter''. "Sparrow-hawk" or sparhawk originally referred to ''Accipiter nisus'', now called "Eurasian" or "northern" sparrowhawk to distinguish it f ...

s)

* "Longwings": Falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Adult falcons ...

s (peregrine falcons, kestrels, gyrfalcons, saker falcons)

Owls are also used, although they are far less common.

In determining whether a species can or should be used for falconry, the species' behavior in a captive environment, its responsiveness to training, and its typical prey and hunting habits are considered. To some degree, a species' reputation will determine whether it is used, although this factor is somewhat harder to objectively gauge.

Species for beginners

In North America, the capable red-tailed hawk is commonly flown by beginner falconers during their apprenticeship. Opinions differ on the usefulness of the kestrel for beginners due to its inherent fragility. In the UK, beginner falconers are often permitted to acquire a larger variety of birds, but Harris's hawk and the red-tailed hawk remain the most commonly used for beginners and experienced falconers alike. Red-tailed hawks are held in high regard in the UK due to the ease of breeding them in captivity, their inherent hardiness, and their capability hunting the rabbits and hares commonly found throughout the countryside in the UK. Many falconers in the UK and North America switch to accipiters or large falcons following their introduction with easier birds. In the US, accipiters, several types of buteos, and large falcons are only allowed to be owned by falconers who hold a general license. The three kinds of falconry licenses in the United States, typically, are the apprentice class, general class, and master class.

Soaring hawks and the common buzzard (''Buteo'')

The genus ''

The genus ''Buteo

''Buteo'' is a genus of medium to fairly large, wide-ranging raptors with a robust body and broad wings. In the Old World, members of this genus are called "buzzards", but " hawk" is used in the New World (Etymology: ''Buteo'' is the Latin na ...

'', known as "hawks" in North America and not to be confused with vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

s, has worldwide distribution, but is particularly well represented in North America. The red-tailed hawk, ferruginous hawk

The ferruginous hawk, (''Buteo regalis''), is a large bird of prey and belongs to the broad-winged buteo hawks. An old colloquial name is ferrugineous rough-leg, due to its similarity to the closely related rough-legged hawk (''B. lagopus'').

...

, and rarely, the red-shouldered hawk

The red-shouldered hawk (''Buteo lineatus'') is a medium-sized buteo. Its breeding range spans eastern North America and along the coast of California and northern to northeastern-central Mexico. It is a permanent resident throughout most of its ...

are all examples of species from this genus that are used in falconry today. The red-tailed hawk is hardy and versatile, taking rabbits, hares, and squirrels; given the right conditions, it can catch the occasional duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form ...

or pheasant

Pheasants ( ) are birds of several genera within the family Phasianidae in the order Galliformes. Although they can be found all over the world in introduced (and captive) populations, the pheasant genera native range is restricted to Eurasia ...

. The red-tailed hawk is also considered a good bird for beginners. The Eurasian or common buzzard is also used, although this species requires more perseverance if rabbit

Rabbits, also known as bunnies or bunny rabbits, are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also contains the hares) of the order Lagomorpha (which also contains the pikas). ''Oryctolagus cuniculus'' includes the European rabbit speci ...

s are to be hunted.

Harris's hawk (''Parabuteo unicinctus'')

''Parabuteo unicinctus'' is one of two representatives of the ''Parabuteo'' genus worldwide. The other is the white-rumped hawk (''P. leucorrhous''). Arguably the best rabbit or hare raptor available anywhere, Harris's hawk is also adept at catching birds. Often captive-bred, Harris's hawk is remarkably popular because of its temperament and ability. It is found in the wild living in groups or packs, and hunts cooperatively, with a social hierarchy similar to wolves. This highly social behavior is not observed in any other bird-of-prey species, and is very adaptable to falconry. This genus is native to the

''Parabuteo unicinctus'' is one of two representatives of the ''Parabuteo'' genus worldwide. The other is the white-rumped hawk (''P. leucorrhous''). Arguably the best rabbit or hare raptor available anywhere, Harris's hawk is also adept at catching birds. Often captive-bred, Harris's hawk is remarkably popular because of its temperament and ability. It is found in the wild living in groups or packs, and hunts cooperatively, with a social hierarchy similar to wolves. This highly social behavior is not observed in any other bird-of-prey species, and is very adaptable to falconry. This genus is native to the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

from southern Texas and Arizona to South America. Harris's hawk is often used in the modern technique of car hawking (or drive-by falconry), where the raptor is launched from the window of a moving car at suitable prey.

True hawks (''Accipiter'')

The genus ''Accipiter'' is also found worldwide. Hawk expert Mike McDermott once said, "The attack of the accipiters is extremely swift, rapid, and violent in every way." They are well known in falconry use both in Europe and North America. The northern goshawk has been trained for falconry for hundreds of years, taking a variety of birds and mammals. Other popular ''Accipiter'' species used in falconry include Cooper's hawk and the sharp-shinned hawk in North America and the European sparrowhawk in Europe and Eurasia.

Harriers (''Circus'')

New Zealand is likely to be one of the few countries to use a harrier species for falconry; there, falconers successfully hunt with the Australasian harrier (''Circus approximans'').

Falcons (''Falco'')

The genus '' Falco'' is found worldwide and has occupied a central niche in ancient and modern falconry. Most falcon species used in falconry are specialized predators, most adapted to capturing bird prey such as the peregrine falcon and merlin. A notable exception is the use of desert falcons such the saker falcon in ancient and modern falconry in Asia and Western Asia, where hares were and are commonly taken. In North America, the prairie falcon

The prairie falcon (''Falco mexicanus'') is a medium-large sized falcon of western North America. It is about the size of a peregrine falcon or a crow, with an average length of 40 cm (16 in), wingspan of approximately 1 meter (40&n ...

and the gyrfalcon

The gyrfalcon ( or ) (), the largest of the falcon species, is a bird of prey. The abbreviation gyr is also used. It breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, and the islands of northern North America and the Eurosiberian region. It is mainly a resid ...

can capture small mammal prey such as rabbits and hares (as well as the standard gamebirds and waterfowl) in falconry, but this is rarely practiced. Young falconry apprentices in the United States often begin practicing the art with American kestrel

The American kestrel (''Falco sparverius''), also called the sparrow hawk, is the smallest and most common falcon in North America. It has a roughly two-to-one range in size over subspecies and sex, varying in size from about the weight of ...

s, the smallest of the falcons in North America; debate remains on this, as they are small, fragile birds, and can die easily if neglected. Small species, such as kestrels, merlins and hobbys are most often flown on small birds such as starlings or sparrows, but can also be used for recreational bug hawking – that is, hunting large flying insects such as dragonflies, grasshoppers, and moths.

Owls (Strigidae)

Owl

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes (), which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers a ...

s (family Strigidae) are not closely related to hawks or falcons. Little is written in classic falconry that discusses the use of owls in falconry. However, at least two species have successfully been used, the Eurasian eagle-owl

The Eurasian eagle-owl (''Bubo bubo'') is a species of eagle-owl that resides in much of Eurasia. It is also called the Uhu and it is occasionally abbreviated to just the eagle-owl in Europe. It is one of the largest species of owl, and femal ...

and the great horned owl

The great horned owl (''Bubo virginianus''), also known as the tiger owl (originally derived from early naturalists' description as the "winged tiger" or "tiger of the air"), or the hoot owl, is a large owl native to the Americas. It is an extre ...

. Successful training of owls is much different from the training of hawks and falcons, as they are hearing- rather than sight-oriented. (Owls can only see black and white, and are long-sighted.) This often leads falconers to believe that they are less intelligent, as they are distracted easily by new or unnatural noises, and they do not respond as readily to food cues. However, if trained successfully, owls show intelligence on the same level as those of hawks and falcons.

Booted eagles (''Aquila'')

The '' Aquila'' (all have "booted" or feathered tarsi) genus has a nearly worldwide distribution. The more powerful types are used in falconry; for example golden eagles have reportedly been used to hunt

The '' Aquila'' (all have "booted" or feathered tarsi) genus has a nearly worldwide distribution. The more powerful types are used in falconry; for example golden eagles have reportedly been used to hunt wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly un ...

in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, and are now most widely used by the Altaic Kazakh eagle hunters in the western Mongolian province of Bayan-Ölgii to hunt foxes,Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the east. ...

. Most are primarily ground-oriented, but occasionally take birds. Eagles are not used as widely in falconry as other birds of prey, due to the lack of versatility in the larger species (they primarily hunt over large, open ground), the greater potential danger to other people if hunted in a widely populated area, and the difficulty of training and managing an eagle. A little over 300 active falconers are using eagles in Central Asia, with 250 in western Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

, 50 in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, and smaller numbers in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the east. ...

and western China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

Sea eagles (''Haliaëtus'')

Most species of genus '' Haliaëtus'' catch and eat fish, some almost exclusively, but in countries where they are not protected, some have been effectively used in hunting for ground quarry.

Husbandry, training, and equipment

''See Hack (falconry) and Falconry training and technique

Training raptors (birds of prey) is a complex undertaking. Books containing advice by experienced falconers are still rudimentary at best.

Many important details vary between individual raptors, species of raptors and between places and times. ...

. They can be trained by nurturing a deep bond between the falconer and Falcon.They should cover the falcon’s head with a leather band if not hunting.''

Falconry around the world

Falconry is currently practiced in many countries around the world. The falconer's traditional choice of bird is the northern goshawk and peregrine falcon. In contemporary falconry in both North America and the UK, they remain popular, although Harris' hawks and red-tailed hawks are likely more widely used. The northern goshawk and the

Falconry is currently practiced in many countries around the world. The falconer's traditional choice of bird is the northern goshawk and peregrine falcon. In contemporary falconry in both North America and the UK, they remain popular, although Harris' hawks and red-tailed hawks are likely more widely used. The northern goshawk and the golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of p ...

are more commonly used in Eastern Europe than elsewhere. In the west asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

, the saker falcon is the most traditional species flown against the houbara bustard

The houbara bustard (''Chlamydotis undulata''), also known as African houbara, is a relatively small bustard native to North Africa, where it lives in arid habitats. The global population is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 2014. ...

, sandgrouse

Sandgrouse is the common name for Pteroclidae , a family of sixteen species of bird, members of the order Pterocliformes . They are traditionally placed in two genera. The two central Asian species are classified as '' Syrrhaptes'' and the othe ...

, stone-curlew, other birds, and hares. Peregrines and other captive-bred imported falcons are also commonplace. Falconry remains an important part of the Arab heritage and culture. The UAE

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia (The Middle East). It is located at th ...

reportedly spends over US$27 million annually towards the protection and conservation of wild falcons, and has set up several state-of-the-art falcon hospitals in Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital

The Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital (ADFH) is the first public medical institution exclusively for falcons in the United Arab Emirates. Established by Environment Agency – Abu Dhabi and opened on 3 October 1999, Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital has become ...

is the largest falcon hospital in the whole world. Two breeding farms are in the Emirates, as well as those in Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Every year, falcon beauty contests and demonstrations take place at the ADIHEX exhibition in Abu Dhabi.

Eurasian sparrowhawks were formerly used to take a range of small birds, but are really too delicate for serious falconry, and have fallen out of favour now that American species are available.

In North America and the UK, falcons usually fly only after birds. Large falcons are typically trained to fly in the "waiting-on" style, where the falcon climbs and circles above the falconer and/or dog and the quarry is flushed when the falcon is in the desired commanding position. Classical game hawking in the UK had a brace

Brace(s) or bracing may refer to:

Medical

* Orthopaedic brace, a device used to restrict or assist body movement

** Back brace, a device limiting motion of the spine

*** Milwaukee brace, a kind of back brace used in the treatment of spinal cur ...

of peregrine falcons flown against the red grouse, or merlins in "ringing" flights after skylark

''Alauda'' is a genus of larks found across much of Europe, Asia and in the mountains of north Africa, and one of the species (the Raso lark) endemic to the islet of Raso in the Cape Verde Islands. Further, at least two additional species are ...

s. Rooks

Rook (''Corvus frugilegus'') is a bird of the corvid family. Rook or rooks may also refer to:

Games

*Rook (chess), a piece in chess

*Rook (card game), a trick-taking card game

Military

*Sukhoi Su-25 or Rook, a close air support aircraft

* USS ...

and crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

s are classic game for the larger falcons, and the magpie

Magpies are birds of the Corvidae family. Like other members of their family, they are widely considered to be intelligent creatures. The Eurasian magpie, for instance, is thought to rank among the world's most intelligent creatures, and is one ...

, making up in cunning what it lacks in flying ability, is another common target. Short-wings can be flown in both open and wooded country against a variety of bird and small mammal prey. Most hunting with large falcons requires large, open tracts where the falcon is afforded opportunity to strike or seize its quarry before it reaches cover. Most of Europe practices similar styles of falconry, but with differing degrees of regulation.

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

falconers often rode horses, but this is now rare with the exception of contemporary Kazakh and Mongolian falconry. In Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the east. ...

, and Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

, the golden eagle is traditionally flown (often from horseback), hunting game as large as fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelve sp ...

es and wolves.

In Japan, the northern goshawk has been used for centuries. Japan continues to honor its strong historical links with falconry (''takagari

is Japanese falconry, a sport of the noble class, and a symbol of their nobility, their status, and their warrior spirit.

History

In Japan, records indicate that falconry from Continental Asia began in the fourth century.Nihon Rekishi Daijiten ...

''), while adopting some modern techniques and technologies.

In Australia, although falconry is not specifically illegal, it is illegal to keep any type of bird of prey in captivity without the appropriate permits. The only exemption is when the birds are kept for purposes of rehabilitation (for which a licence must still be held), and in such circumstances it may be possible for a competent falconer to teach a bird to hunt and kill wild quarry, as part of its regime of rehabilitation to good health and a fit state to be released into the wild.

In New Zealand, falconry was formally legalised for one species only, the swamp/Australasian harrier ('' Circus approximans'') in 2011. This was only possible with over 25 years of effort from both Wingspan National Bird of Prey Center and the Raptor Association of New Zealand. Falconry can only be practiced by people who have been issued a falconry permit by the Department of Conservation. Tangent aspects, such as bird abatement

Bird control or bird abatement involves the methods to eliminate or deter pest birds from landing, roosting and nesting.

Bird control is important because pest birds can create health-related problems through their feces, including histoplasmos ...

and raptor rehabilitation Raptor rehabilitation is a field of veterinary medicine dealing with care for sick or injured birds of prey, with the goal of returning them to the wild. Since raptors are highly specialized predatory birds, special skills, facilities, equipment, v ...

, also employ falconry techniques to accomplish their goals.

Clubs and organizations

In the UK, the British Falconers' Club (BFC) is the oldest and largest of the falconry clubs. BFC was founded in 1927 by the surviving members of the Old Hawking Club, itself founded in 1864. Working closely with the Hawk Board, an advisory body representing the interests of UK bird of prey keepers, the BFC is in the forefront of raptor conservation, falconer education, and sustainable falconry. Established in 1927, the BFC now has a membership over 1,200 falconers. It began as a small and elite club, but it is now a sizeable democratic organisation that has members from all walks of life, flying hawks, falcons, and eagles at legal quarry throughout the British Isles.

The North American Falconers Association The North American Falconers Association (NAFA) is a falconry organization composed primarily of falconers.

Founded in 1961 by Hal Webster, Frank Beebe

Frank Lyman Beebe (1914 – 15 November 2008) was a falconer, writer and wildlife illustrat ...

(NAFA), founded in 1961, is the premier club for falconry in the US, Canada, and Mexico, and has members worldwide. NAFA is the primary club in the United States and has a membership from around the world. Most USA states have their own falconry clubs. Although these clubs are primarily social, they also serve to represent falconers within their states in regards to that state's wildlife regulations.

The International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey, founded in 1968, currently represents 156 falconry clubs and conservation organisations from 87 countries worldwide, totalling over 75,000 members.

The Saudi Falcons Club preserves the historical heritage associated with the falconry culture, and spreads awareness and provides training to protect falcons and flourish falconry.

Captive breeding and conservation

The successful and now widespread captive breeding of birds of prey began as a response to dwindling wild populations due to persistent toxins such as PCBs

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are highly carcinogenic chemical compounds, formerly used in industrial and consumer products, whose production was banned in the United States by the Toxic Substances Control Act in 1979 and internationally by t ...

and DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound, an organochloride. Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. ...

, systematic persecution as undesirable predators, habitat loss, and the resulting limited availability of popular species for falconry, particularly the peregrine falcon. The first known raptors to breed in captivity belonged to a German falconer named Renz Waller. In 1942–43, he produced two young peregrines in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

in Germany.

The first successful captive breeding of peregrine falcons in North America occurred in the early 1970s by the Peregrine Fund, professor and falconer Heinz Meng, and other private falconer/breeders such as David Jamieson and Les Boyd who bred the first peregrines by means of artificial insemination. In Great Britain, falconer Phillip Glasier of the Falconry Centre in Newent, Gloucestershire, was successful in obtaining young from more than 20 species of captive raptors. A cooperative effort began between various government agencies, non-government organizations, and falconers to supplement various wild raptor populations in peril. This effort was strongest in North America where significant private donations along with funding allocations through the Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA or "The Act"; 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.) is the primary law in the United States for protecting imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of ec ...

of 1972 provided the means to continue the release of captive-bred peregrines, golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of p ...

s, bald eagles, aplomado falcon

The aplomado falcon (''Falco femoralis'') is a medium-sized falcon of the Americas. The species' largest contiguous range is in South America, but not in the deep interior Amazon Basin. It was long known as ''Falco fusco-coerulescens'' or ''Fal ...

s and others. By the mid-1980s, falconers had become self-sufficient as regards sources of birds to train and fly, in addition to the immensely important conservation benefits conferred by captive breeding.

Between 1972 and 2001, nearly all peregrines used for falconry in the U.S. were captive-bred from the progeny of falcons taken before the U. S. Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA or "The Act"; 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.) is the primary law in the United States for protecting imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of ec ...

was passed, and from those few infusions of wild genes available from Canada and special circumstances. Peregrine falcons were removed from the United States' endangered species list on August 25, 1999. Finally, after years of close work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, a limited take of wild peregrines was allowed in 2001, the first wild peregrines taken specifically for falconry in over 30 years.

Some controversy has existed over the origins of captive-breeding stock used by the Peregrine Fund in the recovery of peregrine falcons throughout the contiguous United States. Several peregrine subspecies were included in the breeding stock, including birds of Eurasian origin. Due to the extirpation

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...