Albert Einstein ( ;

; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born

theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experime ...

,

widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the

theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical phenomena in ...

, but he also made important contributions to the development of the theory of

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

. Relativity and quantum mechanics are the two pillars of

modern physics

Modern physics is a branch of physics that developed in the early 20th century and onward or branches greatly influenced by early 20th century physics. Notable branches of modern physics include quantum mechanics, special relativity and general ...

.

His

mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame, where the two quantities differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physici ...

formula , which arises from relativity theory, has been dubbed "the world's most famous equation".

His work is also known for its influence on the

philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultim ...

.

He received the 1921

Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

"for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the

photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons when electromagnetic radiation, such as light, hits a material. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physics, and solid st ...

",

a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory. His intellectual achievements and originality resulted in "Einstein" becoming synonymous with "genius".

In 1905, a year sometimes described as his ''

annus mirabilis

''Annus mirabilis'' (pl. ''anni mirabiles'') is a Latin phrase that means "marvelous year", "wonderful year", "miraculous year", or "amazing year". This term has been used to refer to several years during which events of major importance are re ...

'' ('miracle year'), Einstein published

four groundbreaking papers. These outlined the theory of the photoelectric effect, explained

Brownian motion

Brownian motion, or pedesis (from grc, πήδησις "leaping"), is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas).

This pattern of motion typically consists of random fluctuations in a particle's position insi ...

, introduced

special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory regarding the relationship between space and time. In Albert Einstein's original treatment, the theory is based on two postulates:

# The laws o ...

, and demonstrated mass-energy equivalence. Einstein thought that the laws of

classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classical ...

could no longer be reconciled with those of the

electromagnetic field

An electromagnetic field (also EM field or EMF) is a classical (i.e. non-quantum) field produced by (stationary or moving) electric charges. It is the field described by classical electrodynamics (a classical field theory) and is the classical c ...

, which led him to develop his special theory of relativity. He then extended the theory to gravitational fields; he published a paper on

general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

in 1916, introducing his theory of gravitation. In 1917, he applied the general theory of relativity to model the structure of the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

.

He continued to deal with problems of

statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic be ...

and quantum theory, which led to his explanations of particle theory and the

motion of molecules. He also investigated the thermal properties of light and the quantum theory of

radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

, which laid the foundation of the

photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they always ...

theory of light.

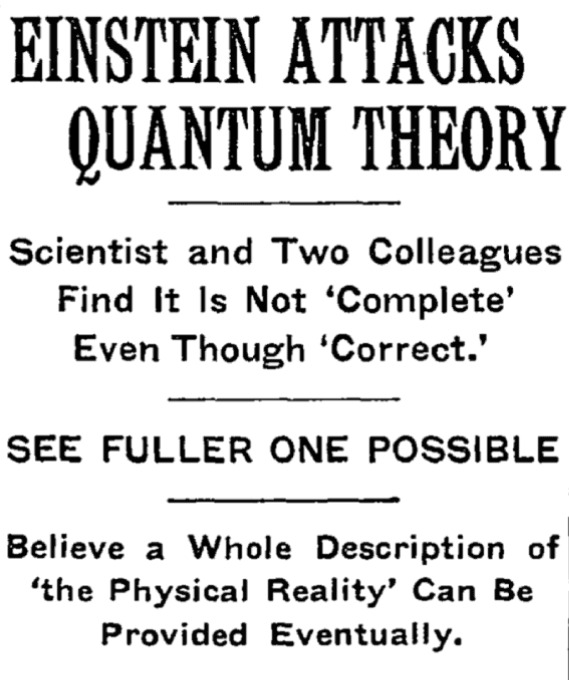

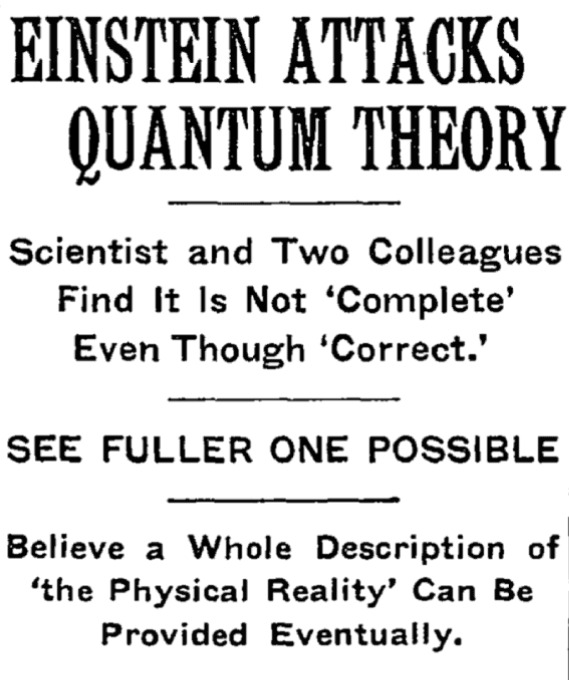

However, for much of the later part of his career, he worked on two ultimately unsuccessful endeavors. First, despite his great contributions to quantum mechanics, he opposed what it evolved into, objecting that "God does not play dice". Second, he attempted to devise a

unified field theory

In physics, a unified field theory (UFT) is a type of field theory that allows all that is usually thought of as fundamental forces and elementary particles to be written in terms of a pair of physical and virtual fields. According to the modern ...

by generalizing his geometric theory of

gravitation

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stron ...

to include

electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

. As a result, he became increasingly isolated from the mainstream of modern

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

.

Einstein was born in the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, but moved to

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

in 1895, forsaking his German citizenship (as a subject of the

Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg (german: Königreich Württemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which exist ...

)

the following year. In 1897, at the age of 17, he enrolled in the mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Swiss

Federal polytechnic school in

Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

, graduating in 1900. In 1901, he acquired Swiss citizenship, which he kept for the rest of his life, and in 1903 he secured a permanent position at the

Swiss Patent Office

The Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property (French: ''Institut fédéral de la propriété intellectuelle'', IPI; German: ''Eidgenössisches Institut für Geistiges Eigentum'', IGE; Italian: ''Istituto federale della proprietà intelle ...

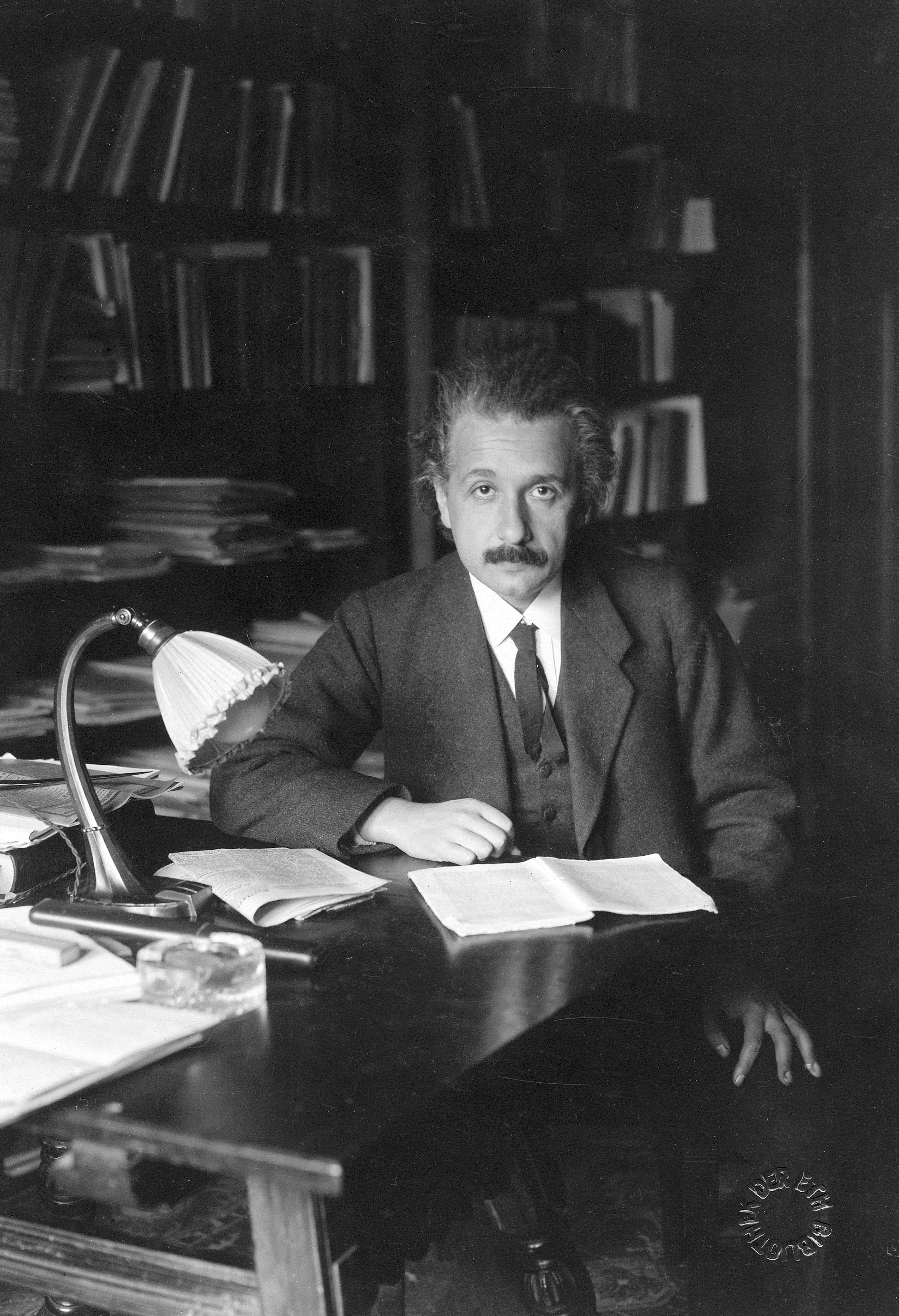

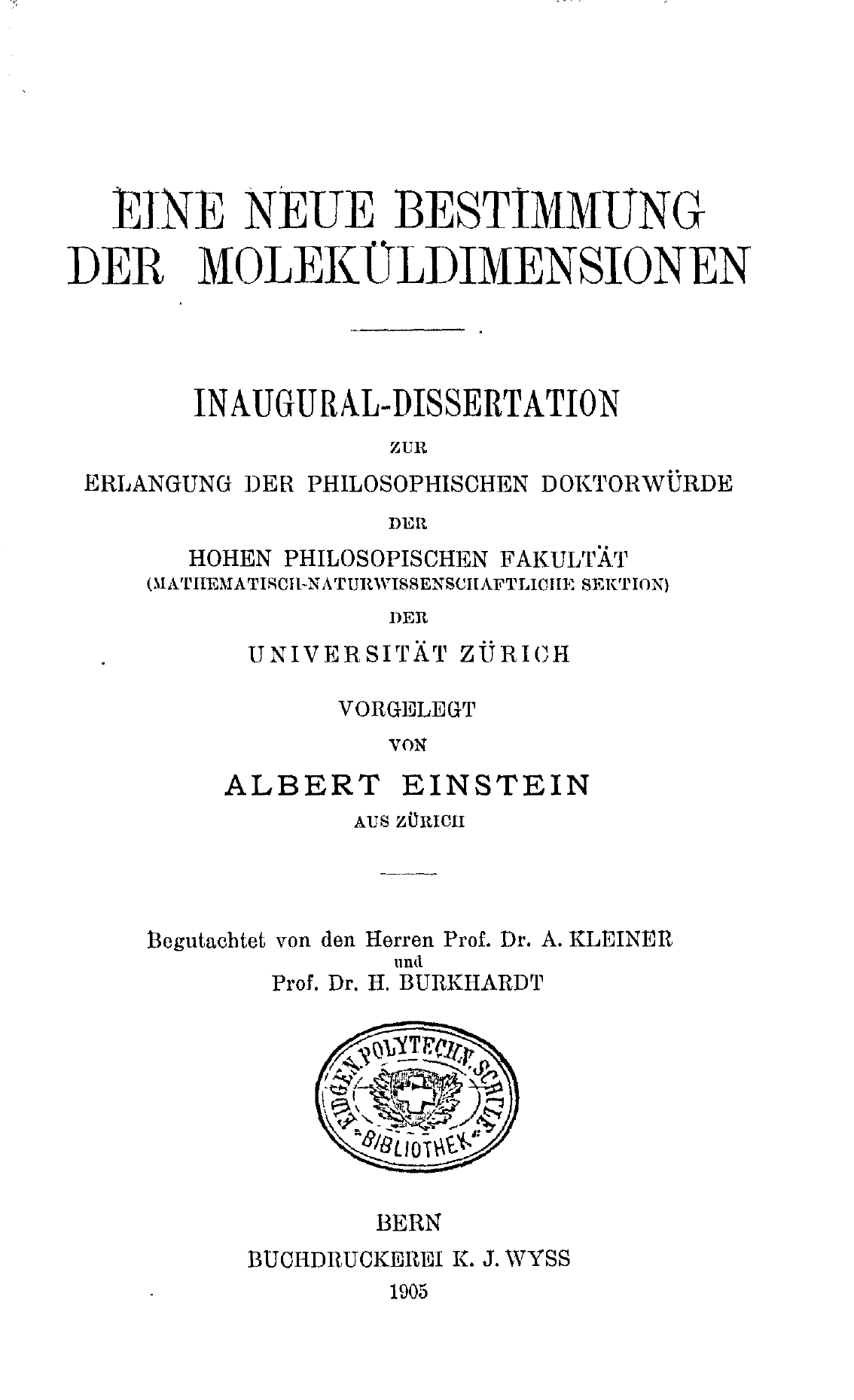

in Bern. In 1905, he was awarded a PhD by the

University of Zurich

The University of Zürich (UZH, german: Universität Zürich) is a public research university located in the city of Zürich, Switzerland. It is the largest university in Switzerland, with its 28,000 enrolled students. It was founded in 1833 f ...

. In 1914, Einstein moved to

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in order to join the

Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

and the

Humboldt University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

. In 1917, Einstein became director of the

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (German language, German: ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften'') was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions we ...

; he also became a German citizen again, this time

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n.

In 1933, while Einstein was visiting the United States,

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

came to power in Germany. Einstein, as a Jew, objected to the policies of the newly elected

Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

;

he settled in the United States and became an

American citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

in 1940.

On the eve of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he endorsed

a letter to President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

alerting him to the potential

German nuclear weapons program

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through sev ...

and recommending that the US begin

similar research. Einstein supported the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

but generally denounced the idea of

nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

.

Life and career

Early life and education

Albert Einstein was born in

Ulm

Ulm () is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Danube on the border with Bavaria. The city, which has an estimated population of more than 126,000 (2018), forms an urban district of its own (german: link=no, ...

,

in the

Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg (german: Königreich Württemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which exist ...

in the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, on 14 March 1879 into a family of secular

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

. His parents were

Hermann Einstein

The Einstein family is the family of physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955). Einstein's great-great-great-great-grandfather, Jakob Weil, was his oldest recorded relative, born in the late 17th century, and the family continues to this day. Al ...

, a salesman and engineer, and

Pauline Koch. In 1880, the family moved to

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, where Einstein's father and his uncle Jakob founded ''Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie'', a company that manufactured electrical equipment based on

direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or even ...

.

Albert attended a

Catholic elementary school in Munich, from the age of five, for three years. At the age of eight, he was transferred to the Luitpold-Gymnasium (now known as the Albert-Einstein-Gymnasium), where he received advanced primary and secondary school education until he left the German Empire seven years later.

In 1894, Hermann and Jakob's company lost a bid to supply the city of Munich with electrical lighting because they lacked the capital to convert their equipment from the

direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or even ...

(DC) standard to the more efficient

alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in whic ...

(AC) standard.

The loss forced the sale of the Munich factory. In search of business, the Einstein family moved to Italy, first to

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

and a few months later to

Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

. When the family moved to Pavia, Einstein, then 15, stayed in Munich to finish his studies at the Luitpold Gymnasium. His father intended for him to pursue

electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

, but Einstein clashed with the authorities and resented the school's regimen and teaching method. He later wrote that the spirit of learning and creative thought was lost in strict

rote learning

Rote learning is a memorization technique based on repetition. The method rests on the premise that the recall of repeated material becomes faster the more one repeats it. Some of the alternatives to rote learning include meaningful learning, ...

. At the end of December 1894, he traveled to Italy to join his family in Pavia, convincing the school to let him go by using a doctor's note. During his time in Italy he wrote a short essay with the title "On the Investigation of the State of the

Ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be c ...

in a Magnetic Field".

Einstein excelled at math and physics from a young age, reaching a mathematical level years ahead of his peers. The 12-year-old Einstein taught himself algebra and Euclidean geometry over a single summer. Einstein also independently discovered his own original proof of the

Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry between the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite t ...

aged 12.

A family tutor

Max Talmud

Max Talmey (1869–1941) was an American ophthalmologist of Jewish- Lithuanian descent, best known as Albert Einstein's tutor who introduced him to fields and books on natural science and philosophy, his success in treating cataracts, and his wor ...

says that after he had given the 12-year-old Einstein a geometry textbook, after a short time "

insteinhad worked through the whole book. He thereupon devoted himself to higher mathematics... Soon the flight of his mathematical genius was so high I could not follow." His passion for geometry and algebra led the 12-year-old to become convinced that nature could be understood as a "mathematical structure". Einstein started teaching himself calculus at 12, and as a 14-year-old he says he had "mastered

integral

In mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented i ...

and

differential calculus

In mathematics, differential calculus is a subfield of calculus that studies the rates at which quantities change. It is one of the two traditional divisions of calculus, the other being integral calculus—the study of the area beneath a curve. ...

".

At the age of 13, when he had become more seriously interested in philosophy (and music), Einstein was introduced to

Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

's ''

Critique of Pure Reason''. Kant became his favorite philosopher, his tutor stating: "At the time he was still a child, only thirteen years old, yet Kant's works, incomprehensible to ordinary mortals, seemed to be clear to him."

In 1895, at the age of 16, Einstein took the entrance examinations for the Swiss

Federal polytechnic school in

Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

(later the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, ETH). He failed to reach the required standard in the general part of the examination, but obtained exceptional grades in physics and mathematics. On the advice of the principal of the polytechnic school, he attended the

Argovian cantonal school (

''gymnasium'') in

Aarau

Aarau (, ) is a List of towns in Switzerland, town, a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality, and the capital of the northern Swiss Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Aargau. The List of towns in Switzerland, town is also the capital of the dis ...

, Switzerland, in 1895 and 1896 to complete his secondary schooling. While lodging with the family of

Jost Winteler

Jost Winteler (21 November 1846 - 23 February 1929) was a Swiss professor of Greek and history at the Kantonsschule Aarau (today called the Old Cantonal School Aarau), a linguist, a "noted" philologist, an ornithologist, a journalist, and a pu ...

, he fell in love with Winteler's daughter, Marie. Albert's sister

Maja later married Winteler's son Paul. In January 1896, with his father's approval, Einstein renounced his

citizenship in the German Kingdom of Württemberg to avoid

military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job (volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

Some nations (e.g., Mexico) require a ...

. In September 1896 he passed the Swiss ''

Matura

or its translated terms (''Mature'', ''Matur'', , , , , , ) is a Latin name for the secondary school exit exam or "maturity diploma" in various European countries, including Albania, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech ...

'' with mostly good grades, including a top grade of 6 in physics and mathematical subjects, on

a scale of 1–6. At 17, he enrolled in the four-year mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Federal polytechnic school. Marie Winteler, who was a year older, moved to

Olsberg, Switzerland, for a teaching post.

Einstein's future wife, a 20-year-old

Serbian named

Mileva Marić

Mileva Marić ( sr-cyr, Милева Марић; 19 December 1875 – 4 August 1948), sometimes called Mileva Marić-Einstein ( sr-cyr, Милева Марић-Ајнштајн, Mileva Marić-Ajnštajn), was a Serbian physicist and mathematicia ...

, also enrolled at the polytechnic school that year. She was the only woman among the six students in the mathematics and physics section of the teaching diploma course. Over the next few years, Einstein's and Marić's friendship developed into a romance, and they spent countless hours debating and reading books together on extra-curricular physics in which they were both interested. Einstein wrote in his letters to Marić that he preferred studying alongside her.

In 1900, Einstein passed the exams in Maths and Physics and was awarded a Federal teaching diploma. There is eyewitness evidence and several letters over many years that indicate Marić might have collaborated with Einstein prior to his landmark 1905 papers,

known as the

''Annus Mirabilis'' papers, and that they developed some of the concepts together during their studies, although some historians of physics who have studied the issue disagree that she made any substantive contributions.

Marriages and children

Early correspondence between Einstein and Marić was discovered and published in 1987 which revealed that the couple had a daughter named

"Lieserl", born in early 1902 in

Novi Sad

Novi Sad ( sr-Cyrl, Нови Сад, ; hu, Újvidék, ; german: Neusatz; see below for other names) is the second largest city in Serbia and the capital of the autonomous province of Vojvodina. It is located in the southern portion of the Pan ...

where Marić was staying with her parents. Marić returned to Switzerland without the child, whose real name and fate are unknown. The contents of Einstein's letter in September 1903 suggest that the girl was either given up for adoption or died of

scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

in infancy.

Einstein and Marić married in January 1903. In May 1904, their son

Hans Albert Einstein

Hans Albert Einstein (May 14, 1904 – July 26, 1973) was a Swiss-American engineer and educator, the second child and first son of physicists Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić. He was a long-time professor of hydraulic engineering at the Univ ...

was born in

Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

, Switzerland. Their son

Eduard

Eduard Model Accessories is a Czech manufacturer of plastic models and finescale model accessories.

Formed in 1989 in the city of Most, Eduard began in a rented cellar as a manufacturer of photoetched brass model components. Following the succ ...

was born in Zürich in July 1910. The couple moved to Berlin in April 1914, but Marić returned to Zürich with their sons after learning that, despite their close relationship before,

Einstein's chief romantic attraction was now his cousin

Elsa Löwenthal; she was his first cousin maternally and second cousin paternally. Einstein and Marić divorced on 14 February 1919, having lived apart for five years. As part of the divorce settlement, Einstein agreed to give Marić any future (in the event, 1921) Nobel Prize money.

In letters revealed in 2015, Einstein wrote to his early love Marie Winteler about his marriage and his strong feelings for her. He wrote in 1910, while his wife was pregnant with their second child: "I think of you in heartfelt love every spare minute and am so unhappy as only a man can be." He spoke about a "misguided love" and a "missed life" regarding his love for Marie.

Einstein married Löwenthal in 1919, after having had a relationship with her since 1912.

They emigrated to the United States in 1933. Elsa was diagnosed with heart and kidney problems in 1935 and died in December 1936.

In 1923, Einstein fell in love with a secretary named Betty Neumann, the niece of a close friend, Hans Mühsam. In a volume of letters released by

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, הַאוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה הַעִבְרִית בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם) is a public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Dr. Chaim Weiz ...

in 2006, Einstein described about six women, including Margarete Lebach (a blonde Austrian), Estella Katzenellenbogen (the rich owner of a florist business), Toni Mendel (a wealthy Jewish widow) and Ethel Michanowski (a Berlin socialite), with whom he spent time and from whom he received gifts while being married to Elsa. Later, after the death of his second wife Elsa, Einstein was briefly in a relationship with Margarita Konenkova. Konenkova was a Russian spy who was married to the Russian sculptor

Sergei Konenkov

Sergey Timofeyevich Konenkov (Сергей Тимофеевич Коненков) (also Sergei Konyonkov) (russian: Серге́й Тимофеевич Конёнков; – 9 December 1971) was a Russian and Soviet Union, Soviet sculptor. ...

(who created the bronze bust of Einstein at the

Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

at Princeton).

Einstein's son Eduard had a breakdown at about age 20 and was diagnosed with

schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdra ...

.

His mother cared for him and he was also committed to asylums for several periods, finally, after her death, being committed permanently to

Burghölzli

The ''Psychiatrische Universitätsklinik Zürich'' (Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich) is a psychiatric hospital in Switzerland. As a research hospital, it is associated with the University of Zürich. It is also called Burghölzli, after t ...

, the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zürich.

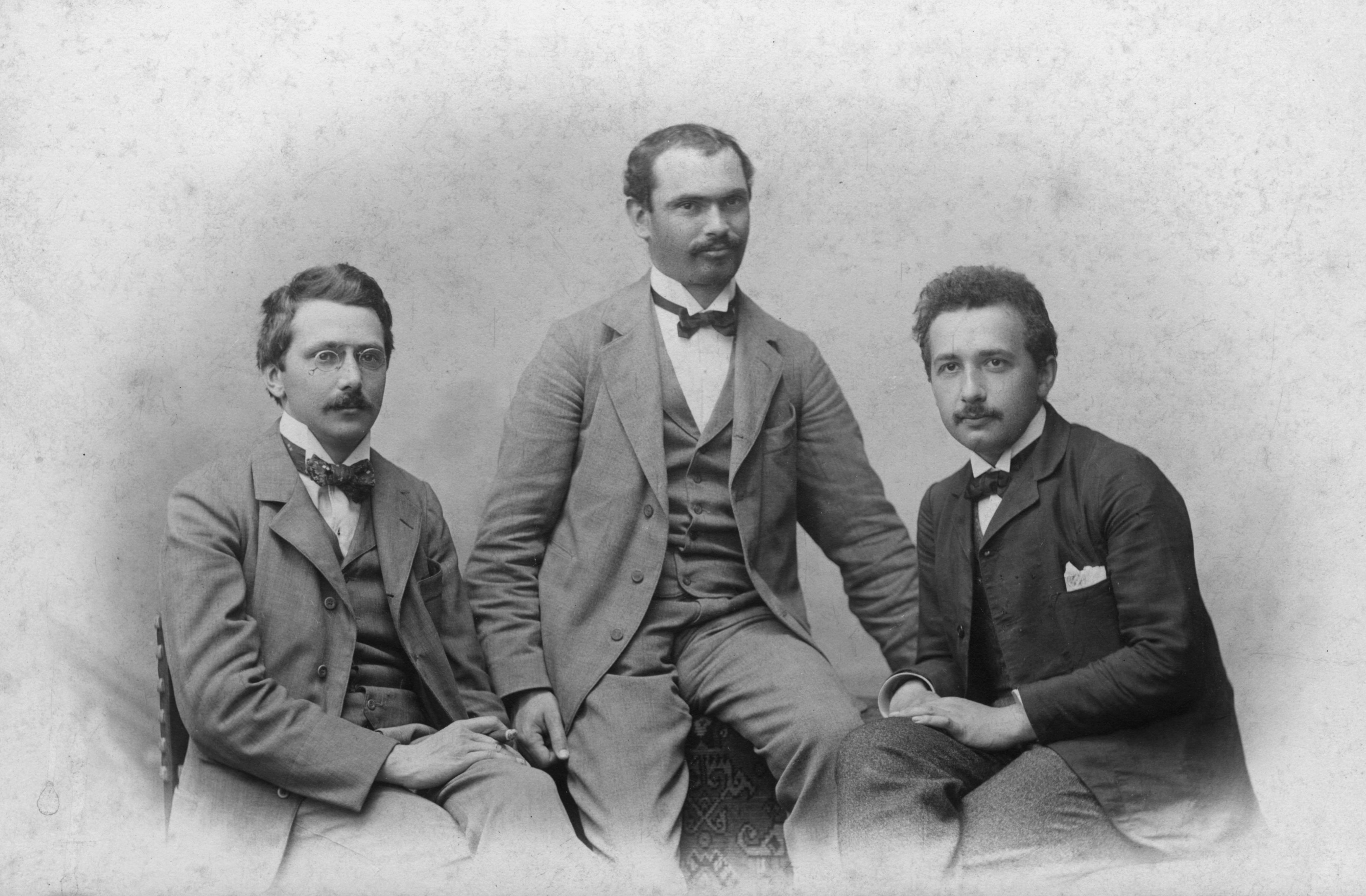

Patent office

After graduating in 1900, Einstein spent almost two years searching for a teaching post. He acquired Swiss citizenship in February 1901, but was not

conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

for medical reasons. With the help of

Marcel Grossmann

Marcel Grossmann (April 9, 1878 – September 7, 1936) was a Swiss mathematician and a friend and classmate of Albert Einstein. Grossmann was a member of an old Swiss family from Zurich. His father managed a textile factory. He became a Profe ...

's father, he secured a job in

Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

at the

Swiss Patent Office

The Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property (French: ''Institut fédéral de la propriété intellectuelle'', IPI; German: ''Eidgenössisches Institut für Geistiges Eigentum'', IGE; Italian: ''Istituto federale della proprietà intelle ...

,

as an

assistant examiner – level III.

Einstein evaluated

patent application

A patent application is a request pending at a patent office for the grant of a patent for an invention described in the patent specification and a set of one or more claims stated in a formal document, including necessary official forms and re ...

s for a variety of devices including a gravel sorter and an electromechanical typewriter.

In 1903, his position at the Swiss Patent Office became permanent, although he was passed over for promotion until he "fully mastered machine technology".

Much of his work at the patent office related to questions about transmission of electric signals and electrical-mechanical synchronization of time, two technical problems that show up conspicuously in the

thought experiments

A thought experiment is a hypothetical situation in which a hypothesis, theory, or principle is laid out for the purpose of thinking through its consequences.

History

The ancient Greek ''deiknymi'' (), or thought experiment, "was the most anci ...

that eventually led Einstein to his radical conclusions about the nature of light and the fundamental connection between space and time.

With a few friends he had met in Bern, Einstein started a small discussion group in 1902, self-mockingly named "

The Olympia Academy", which met regularly to discuss science and philosophy. Sometimes they were joined by Mileva who attentively listened but did not participate. Their readings included the works of

Henri Poincaré,

Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( , ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was a Moravian-born Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the physics of shock waves. The ratio of one's speed to that of sound is named the Mach ...

, and

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

, which influenced his scientific and philosophical outlook.

First scientific papers

In 1900, Einstein's paper

"Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen" ("Conclusions from the Capillarity Phenomena") was published in the journal ''

Annalen der Physik

''Annalen der Physik'' (English: ''Annals of Physics'') is one of the oldest scientific journals on physics; it has been published since 1799. The journal publishes original, peer-reviewed papers on experimental, theoretical, applied, and mathe ...

''.

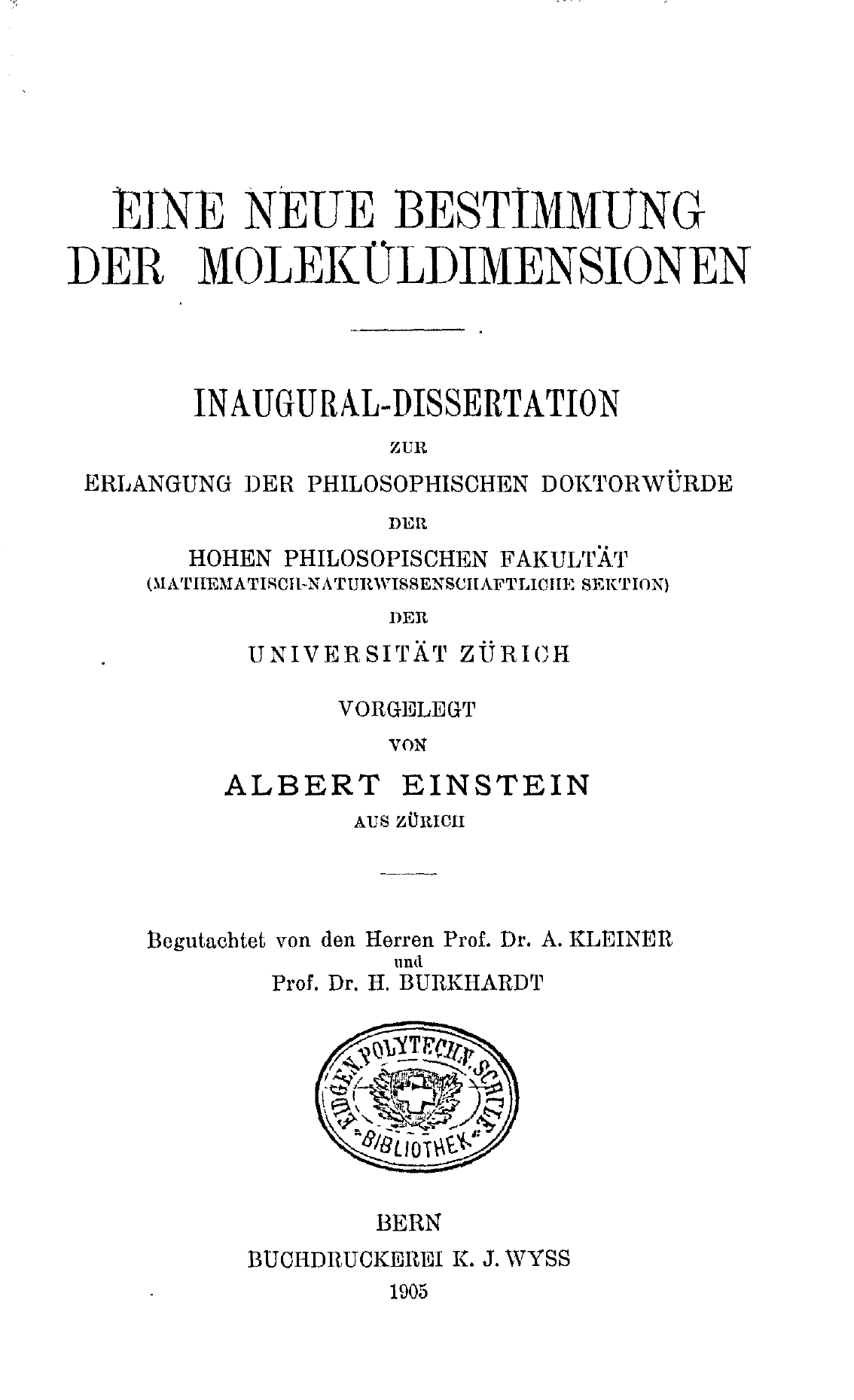

On 30 April 1905 Einstein completed his dissertation, ''A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions'' with

Alfred Kleiner

Alfred Kleiner (24 April 1849 – 3 July 1916) was a Swiss physicist and Professor of Experimental Physics at the University of Zurich. He was Albert Einstein's doctoral advisor or ''Doktorvater.'' Initially Einstein's advisor was Heinrich ...

, serving as ''

pro-forma

The term ''pro forma'' (Latin for "as a matter of form" or "for the sake of form") is most often used to describe a practice or document that is provided as a courtesy or satisfies minimum requirements, conforms to a norm or doctrine, tends to ...

'' advisor. His thesis was accepted in July 1905, and Einstein was awarded a PhD on 15 January 1906.

Also in 1905, which has been called Einstein's ''

annus mirabilis

''Annus mirabilis'' (pl. ''anni mirabiles'') is a Latin phrase that means "marvelous year", "wonderful year", "miraculous year", or "amazing year". This term has been used to refer to several years during which events of major importance are re ...

'' (amazing year), he published

four groundbreaking papers, on the photoelectric effect,

Brownian motion

Brownian motion, or pedesis (from grc, πήδησις "leaping"), is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas).

This pattern of motion typically consists of random fluctuations in a particle's position insi ...

,

special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory regarding the relationship between space and time. In Albert Einstein's original treatment, the theory is based on two postulates:

# The laws o ...

, and the

equivalence of mass and energy

Equivalence or Equivalent may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*Album-equivalent unit, a measurement unit in the music industry

*Equivalence class (music)

*''Equivalent VIII'', or ''The Bricks'', a minimalist sculpture by Carl Andre

*''Equivale ...

, which were to bring him to the notice of the academic world, at the age of 26.

Academic career

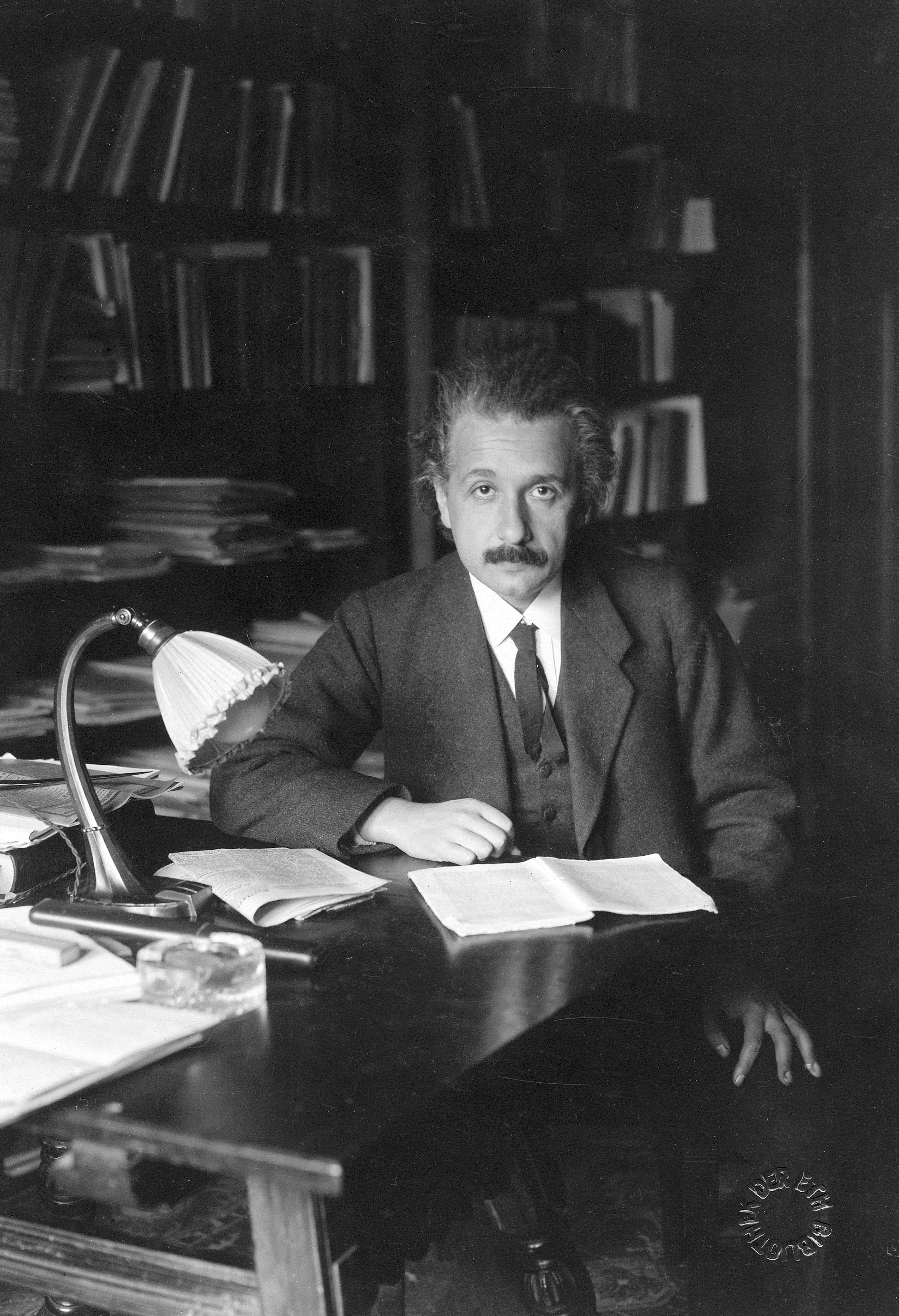

By 1908, he was recognized as a leading scientist and was appointed lecturer at the

University of Bern

The University of Bern (german: Universität Bern, french: Université de Berne, la, Universitas Bernensis) is a university in the Switzerland, Swiss capital of Bern and was founded in 1834. It is regulated and financed by the Canton of Bern. It ...

. The following year, after he gave a lecture on

electrodynamics

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

and the relativity principle at the University of Zurich,

Alfred Kleiner

Alfred Kleiner (24 April 1849 – 3 July 1916) was a Swiss physicist and Professor of Experimental Physics at the University of Zurich. He was Albert Einstein's doctoral advisor or ''Doktorvater.'' Initially Einstein's advisor was Heinrich ...

recommended him to the faculty for a newly created professorship in theoretical physics. Einstein was appointed associate professor in 1909.

Einstein became a full professor at the German

Charles-Ferdinand University

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Králíčková

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, underg ...

in Prague in April 1911, accepting

Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

citizenship in the

Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

to do so.

During his Prague stay, he wrote 11 scientific works, five of them on radiation mathematics and on the quantum theory of solids.

In July 1912, he returned to his alma mater in Zürich. From 1912 until 1914, he was a professor of theoretical physics at the

ETH Zurich

(colloquially)

, former_name = eidgenössische polytechnische Schule

, image = ETHZ.JPG

, image_size =

, established =

, type = Public

, budget = CHF 1.896 billion (2021)

, rector = Günther Dissertori

, president = Joël Mesot

, ac ...

, where he taught analytical mechanics and

thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws of the ...

. He also studied

continuum mechanics

Continuum mechanics is a branch of mechanics that deals with the mechanical behavior of materials modeled as a continuous mass rather than as discrete particles. The French mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy was the first to formulate such m ...

, the molecular theory of heat, and the problem of gravitation, on which he worked with mathematician and friend

Marcel Grossmann

Marcel Grossmann (April 9, 1878 – September 7, 1936) was a Swiss mathematician and a friend and classmate of Albert Einstein. Grossmann was a member of an old Swiss family from Zurich. His father managed a textile factory. He became a Profe ...

.

When the "

Manifesto of the Ninety-Three

The "Manifesto of the Ninety-Three" (originally "To the Civilized World" by "Professors of Germany") is a 4 October 1914 proclamation by 93 prominent Germans supporting Germany in the start of World War I. The Manifesto galvanized support for the w ...

" was published in October 1914—a document signed by a host of prominent German intellectuals that justified Germany's militarism and position during the First World War—Einstein was one of the few German intellectuals to rebut its contents and sign the pacifistic "

Manifesto to the Europeans

The ″Manifesto to the Europeans″ (German: ''Aufruf an die Europäer'') was a pacifistic proclamation written in response to the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three that included as its authors, German astronomer, Wilhelm Julius Foerster, and German p ...

".

In the spring of 1913, Einstein was enticed to move to Berlin with an offer that included membership in the Prussian Academy of Sciences, and a linked University of Berlin professorship, enabling him to concentrate exclusively on research.

On 3 July 1913, he became a member of the

Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

in Berlin.

Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (, ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial contributions to theoretical p ...

and

Walther Nernst visited him the next week in Zurich to persuade him to join the academy, additionally offering him the post of director at the

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (German language, German: ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften'') was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions we ...

, which was soon to be established. Membership in the academy included paid salary and professorship without teaching duties at

Humboldt University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

. He was officially elected to the academy on 24 July, and he moved to Berlin the following year. His decision to move to Berlin was also influenced by the prospect of living near his cousin Elsa, with whom he had started a romantic affair. Einstein assumed his position with the academy, and Berlin University, after moving into his

Dahlem apartment on 1 April 1914.

As World War I broke out that year, the plan for Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was delayed. The institute was established on 1 October 1917, with Einstein as its director.

In 1916, Einstein was elected president of the

German Physical Society (1916–1918).

In 1911, Einstein used his 1907

Equivalence principle

In the theory of general relativity, the equivalence principle is the equivalence of gravitational and inertial mass, and Albert Einstein's observation that the gravitational "force" as experienced locally while standing on a massive body (suc ...

to calculate the deflection of

light from another star by the Sun's gravity. In 1913, Einstein improved upon those calculations by using

Riemannian space-time

In the mathematical field of differential geometry, the Riemann curvature tensor or Riemann–Christoffel tensor (after Bernhard Riemann and Elwin Bruno Christoffel) is the most common way used to express the curvature of Riemannian manifolds. I ...

to represent the gravity field. By the fall of 1915, Einstein had successfully completed his general theory of relativity, which he used to calculate that deflection, and the

perihelion precession of Mercury

Tests of general relativity serve to establish observational evidence for the theory of general relativity. The first three tests, proposed by Albert Einstein in 1915, concerned the "anomalous" precession of the perihelion of Mercury, the bendin ...

.

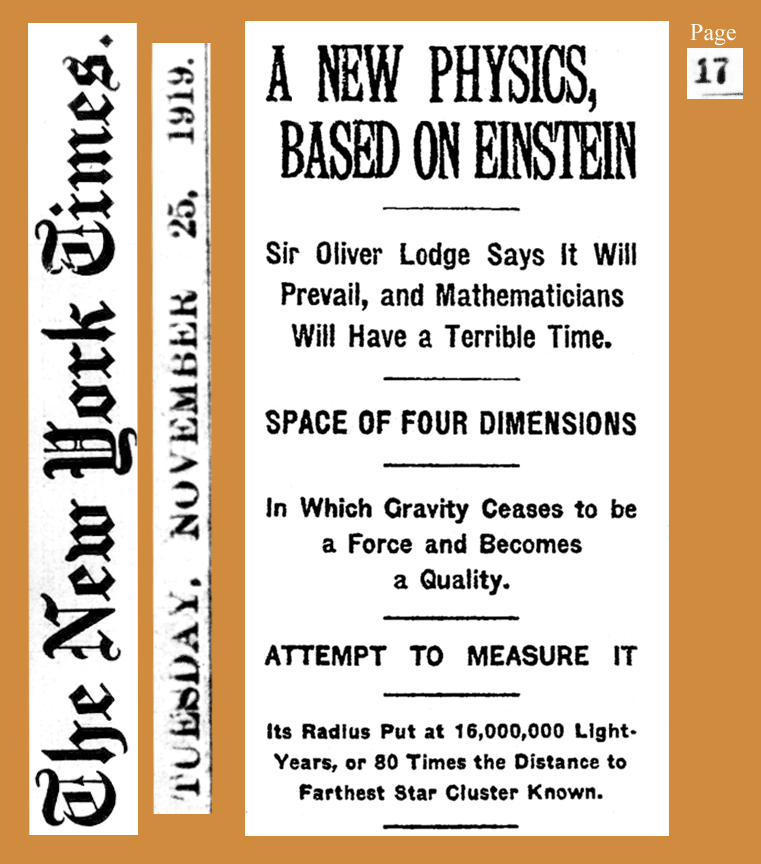

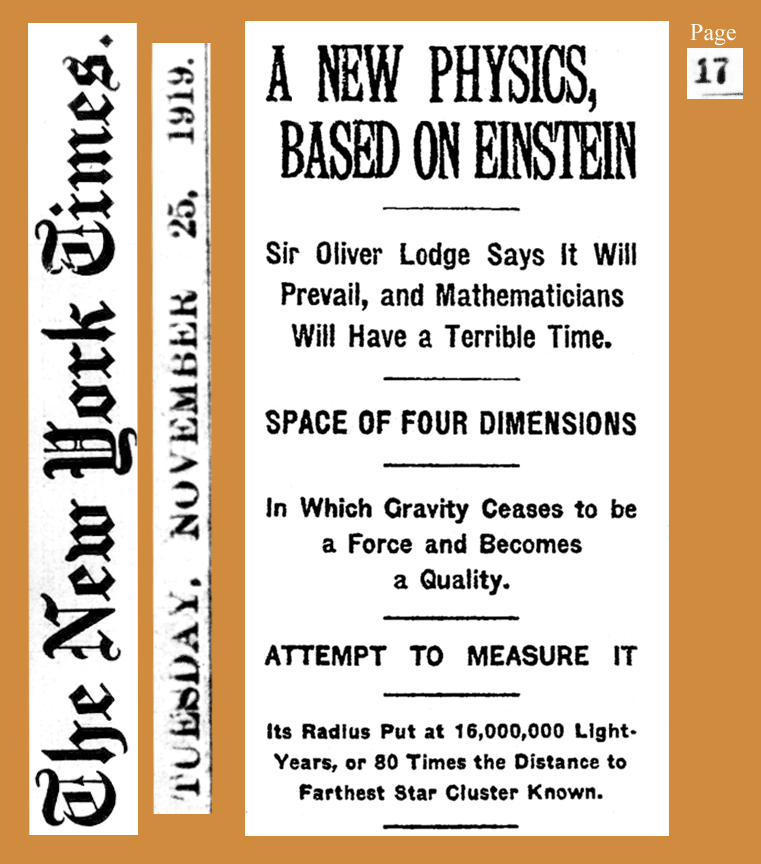

In 1919, that deflection prediction was confirmed by Sir

Arthur Eddington during the

solar eclipse of 29 May 1919. Those observations were published in the international media, making Einstein world-famous. On 7 November 1919, the leading British newspaper ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' printed a banner headline that read: "Revolution in Science – New Theory of the Universe – Newtonian Ideas Overthrown".

In 1920, he became a Foreign Member of the

Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences ( nl, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, abbreviated: KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed ...

.

In 1922, he was awarded the 1921

Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

"for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect".

While the

general theory of relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric scientific theory, theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current descr ...

was still considered somewhat controversial, the citation also does not treat even the cited photoelectric work as an ''explanation'' but merely as a ''discovery of the law'', as the idea of photons was considered outlandish and did not receive universal acceptance until the 1924 derivation of the

Planck spectrum

A black body or blackbody is an idealized physical object, physical body that absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation, regardless of frequency or angle of incidence (optics), angle of incidence. T ...

by

S. N. Bose

Satyendra Nath Bose (; 1 January 1894 – 4 February 1974) was a Bengali mathematician and physicist specializing in theoretical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, in developing the foundation for ...

. Einstein was elected a

Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1921.

He also received the

Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

from the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1925.

Einstein resigned from the Prussian Academy in March 1933. Einstein's scientific accomplishments while in Berlin, included finishing the general theory of relativity, proving the

gyromagnetic effect, contributing to the quantum theory of radiation, and

Bose–Einstein statistics

In quantum statistics, Bose–Einstein statistics (B–E statistics) describes one of two possible ways in which a collection of non-interacting, indistinguishable particles may occupy a set of available discrete energy states at thermodynamic ...

.

1921–1922: Travels abroad

Einstein visited New York City for the first time on 2 April 1921, where he received an official welcome by Mayor

John Francis Hylan

John Francis Hylan (April 20, 1868January 12, 1936) was the 96th Mayor of New York City (the seventh since the consolidation of the five boroughs), from 1918 to 1925. From rural beginnings in the Catskills, Hylan eventually obtained work in Broo ...

, followed by three weeks of lectures and receptions. He went on to deliver several lectures at

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

and

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, and in Washington, he accompanied representatives of the

National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

on a visit to the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

. On his return to Europe he was the guest of the British statesman and philosopher

Viscount Haldane

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

in London, where he met several renowned scientific, intellectual, and political figures, and delivered a lecture at

King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

.

He also published an essay, "My First Impression of the U.S.A.", in July 1921, in which he tried briefly to describe some characteristics of Americans, much as had

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (; 29 July 180516 April 1859), colloquially known as Tocqueville (), was a French aristocrat, diplomat, political scientist, political philosopher and historian. He is best known for his wor ...

, who published his own impressions in ''

Democracy in America

(; published in two volumes, the first in 1835 and the second in 1840) is a classic French text by Alexis de Tocqueville. Its title literally translates to ''On Democracy in America'', but official English translations are usually simply entitl ...

'' (1835).

For some of his observations, Einstein was clearly surprised: "What strikes a visitor is the joyous, positive attitude to life ... The American is friendly, self-confident, optimistic, and without envy."

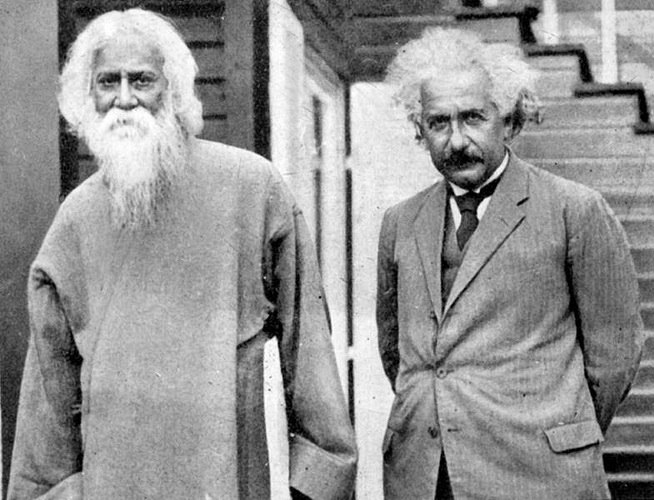

In 1922, his travels took him to Asia and later to Palestine, as part of a six-month excursion and speaking tour, as he visited Singapore,

Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and Japan, where he gave a series of lectures to thousands of Japanese. After his first public lecture, he met the emperor and empress at the

Imperial Palace, where thousands came to watch. In a letter to his sons, he described his impression of the Japanese as being modest, intelligent, considerate, and having a true feel for art. In his own travel diaries from his 1922–23 visit to Asia, he expresses some views on the Chinese, Japanese and Indian people, which have been described as xenophobic and racist judgments when they were rediscovered in 2018.

Because of Einstein's travels to the Far East, he was unable to personally accept the Nobel Prize for Physics at the Stockholm award ceremony in December 1922. In his place, the banquet speech was made by a German diplomat, who praised Einstein not only as a scientist but also as an international peacemaker and activist.

On his return voyage, he visited

Palestine for 12 days, his only visit to that region. He was greeted as if he were a head of state, rather than a physicist, which included a cannon salute upon arriving at the home of the British high commissioner,

Sir Herbert Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel, (6 November 1870 – 5 February 1963) was a British Liberal politician who was the party leader from 1931 to 1935.

He was the first nominally-practising Jew to serve as a Cabinet minister and to beco ...

. During one reception, the building was stormed by people who wanted to see and hear him. In Einstein's talk to the audience, he expressed happiness that the Jewish people were beginning to be recognized as a force in the world.

Einstein visited Spain for two weeks in 1923, where he briefly met

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (; 1 May 1852 – 17 October 1934) was a Spanish neuroscientist, pathologist, and histologist specializing in neuroanatomy and the central nervous system. He and Camillo Golgi received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Me ...

and also received a diploma from

King Alfonso XIII naming him a member of the Spanish Academy of Sciences.

From 1922 to 1932, Einstein was a member of the

International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation

The International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, sometimes League of Nations Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, was an advisory organization for the League of Nations which aimed to promote international exchange between scientists, r ...

of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in Geneva (with a few months of interruption in 1923–1924),

a body created to promote international exchange between scientists, researchers, teachers, artists, and intellectuals.

Originally slated to serve as the Swiss delegate, Secretary-General

Eric Drummond

James Eric Drummond, 7th Earl of Perth, (17 August 1876 – 15 December 1951), was a British politician and diplomat who was the first Secretary-General of the League of Nations (1920–1933).

Quiet and unassuming, he succeeded in building an e ...

was persuaded by Catholic activists

Oskar Halecki

Oskar Halecki (26 May 1891, Vienna, Cisleithania, Austria-Hungary – 17 September 1973, White Plains, New York, United States of America) was a Polish historian, social and Catholic activist.

Life and career

Halecki, whose first name is sometim ...

and

Giuseppe Motta

Giuseppe Motta (29 December 1871 – 23 January 1940) was a Swiss politician. He was a member of the Swiss Federal Council (1911–1940) and President of the League of Nations (1924–1925). He was a Catholic-conservative foreign minister and a ...

to instead have him become the German delegate, thus allowing

Gonzague de Reynold

Gonzague de Reynold (15 June 1880 – 9 April 1970) was a Swiss writer, historian, and right-wing political activist.

Over the course of his six-decade career, he wrote more than thirty books outlining his traditionalist Catholic and Swiss natio ...

to take the Swiss spot, from which he promoted traditionalist Catholic values.

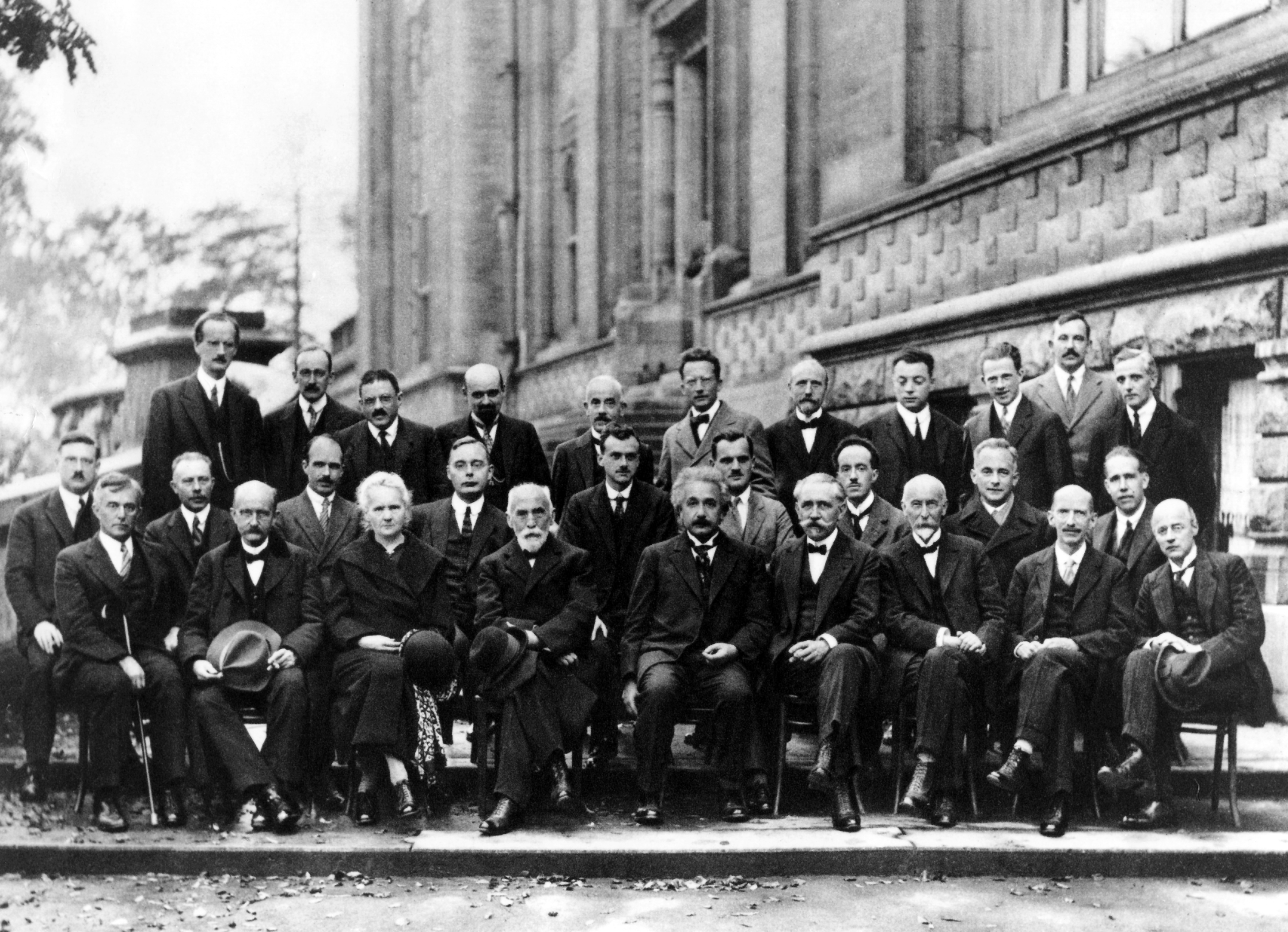

Einstein's former physics professor

Hendrik Lorentz and the Polish chemist

Marie Curie

Marie Salomea Skłodowska–Curie ( , , ; born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first ...

were also members of the committee.

1925: Visit to South America

In the months of March and April 1925, Einstein visited South America, where he spent about a month in

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, a week in

Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and a week in

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, Brazil. Einstein's visit was initiated by Jorge Duclout (1856–1927) and Mauricio Nirenstein (1877–1935) with the support of several Argentine scholars, including

Julio Rey Pastor

Julio Rey Pastor (14 August 1888 – 21 February 1962) was a Spanish mathematician and historian of science.

Biography

Julio Rey Pastor studied high school in his hometown, and began his studies in Sciences in Vitoria. He moved to the Universi ...

,

Jakob Laub

Jakob Johann Laub (born as Jakub Laub, 7 February 1884 in Rzeszów – 22 April 1962 in Fribourg) was a physicist from Austria-Hungary, who is best known for his work with Albert Einstein in the early period of special relativity.

Life

He was the ...

, and

Leopoldo Lugones

Leopoldo Antonio Lugones Argüello (13 June 1874 – 18 February 1938) was an Argentine poet, essayist, novelist, playwright, historian, professor, translator, biographer, philologist, theologian, diplomat, politician and journalist. His poetic ...

. The visit by Einstein and his wife was financed primarily by the Council of the

University of Buenos Aires

The University of Buenos Aires ( es, Universidad de Buenos Aires, UBA) is a public research university in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Established in 1821, it is the premier institution of higher learning in the country and one of the most prestigi ...

and the ''Asociación Hebraica Argentina'' (Argentine Hebraic Association) with a smaller contribution from the Argentine-Germanic Cultural Institution.

1930–1931: Travel to the US

In December 1930, Einstein visited America for the second time, originally intended as a two-month working visit as a research fellow at the

California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

. After the national attention he received during his first trip to the US, he and his arrangers aimed to protect his privacy. Although swamped with telegrams and invitations to receive awards or speak publicly, he declined them all.

After arriving in New York City, Einstein was taken to various places and events, including

Chinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Austra ...

, a lunch with the editors of ''The New York Times'', and a performance of ''Carmen'' at the

Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

, where he was cheered by the audience on his arrival. During the days following, he was given the keys to the city by Mayor

Jimmy Walker

James John Walker (June 19, 1881November 18, 1946), known colloquially as Beau James, was mayor of New York City from 1926 to 1932. A flamboyant politician, he was a liberal Democrat and part of the powerful Tammany Hall machine. He was forced t ...

and met the president of Columbia University, who described Einstein as "the ruling monarch of the mind".

Harry Emerson Fosdick

Harry Emerson Fosdick (May 24, 1878 – October 5, 1969) was an American pastor. Fosdick became a central figure in the Fundamentalist–Modernist controversy within American Protestantism in the 1920s and 1930s and was one of the most prominen ...

, pastor at New York's

Riverside Church

Riverside Church is an interdenominational church in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, on the block bounded by Riverside Drive, Claremont Avenue, 120th Street and 122nd Street near Columbia University's Mornin ...

, gave Einstein a tour of the church and showed him a full-size statue that the church made of Einstein, standing at the entrance. Also during his stay in New York, he joined a crowd of 15,000 people at

Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylva ...

during a

Hanukkah

or English translation: 'Establishing' or 'Dedication' (of the Temple in Jerusalem)

, nickname =

, observedby = Jews

, begins = 25 Kislev

, ends = 2 Tevet or 3 Tevet

, celebrations = Lighting candles each night. ...

celebration.

Einstein next traveled to California, where he met

Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

president and Nobel laureate

Robert A. Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the Elementary charge, elementary electric charge and for his work on ...

. His friendship with Millikan was "awkward", as Millikan "had a penchant for patriotic militarism", where Einstein was a pronounced

pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

. During an address to Caltech's students, Einstein noted that science was often inclined to do more harm than good.

This aversion to war also led Einstein to befriend author

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

and film star

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

, both noted for their pacifism.

Carl Laemmle

Carl Laemmle (; born Karl Lämmle; January 17, 1867 – September 24, 1939) was a film producer and the co-founder and, until 1934, owner of Universal Pictures. He produced or worked on over 400 films.

Regarded as one of the most important o ...

, head of

Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

, gave Einstein a tour of his studio and introduced him to Chaplin. They had an instant rapport, with Chaplin inviting Einstein and his wife, Elsa, to his home for dinner. Chaplin said Einstein's outward persona, calm and gentle, seemed to conceal a "highly emotional temperament", from which came his "extraordinary intellectual energy".

Chaplin's film, ''

City Lights'', was to premiere a few days later in Hollywood, and Chaplin invited Einstein and Elsa to join him as his special guests.

Walter Isaacson

Walter Seff Isaacson (born May 20, 1952) is an American author, journalist, and professor. He has been the President and CEO of the Aspen Institute, a nonpartisan policy studies organization based in Washington, D.C., the chair and CEO of CNN, ...

, Einstein's biographer, described this as "one of the most memorable scenes in the new era of celebrity". Chaplin visited Einstein at his home on a later trip to Berlin and recalled his "modest little flat" and the piano at which he had begun writing his theory. Chaplin speculated that it was "possibly used as kindling wood by the Nazis".

1933: Emigration to the US

In February 1933, while on a visit to the United States, Einstein knew he could not return to Germany with the rise to power of the

Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

under Germany's new chancellor,

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

.

While at American universities in early 1933, he undertook his third two-month visiting professorship at the

California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

in Pasadena. In February and March 1933, the

Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

repeatedly raided his family's apartment in Berlin. He and his wife Elsa returned to Europe in March, and during the trip, they learned that the German Reichstag had passed the

Enabling Act

An enabling act is a piece of legislation by which a legislative body grants an entity which depends on it (for authorization or legitimacy) the power to take certain actions. For example, enabling acts often establish government agencies to carr ...

on 23 March, transforming Hitler's government into a ''de facto'' legal dictatorship, and that they would not be able to proceed to Berlin. Later on, they heard that their cottage had been raided by the Nazis and Einstein's personal sailboat confiscated. Upon landing in

Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504, , Belgium on 28 March, Einstein immediately went to the German consulate and surrendered his passport, formally renouncing his German citizenship. The Nazis later sold his boat and converted his cottage into a

Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

camp.

Refugee status

In April 1933, Einstein discovered that the new German government had passed laws barring Jews from holding any official positions, including teaching at universities. Historian

Gerald Holton

Gerald James Holton (born May 23, 1922) is an American physicist, historian of science, and educator, whose professional interests also include philosophy of science and the fostering of careers of young men and women. He is Mallinckrodt Profes ...

describes how, with "virtually no audible protest being raised by their colleagues", thousands of Jewish scientists were suddenly forced to give up their university positions and their names were removed from the rolls of institutions where they were employed.

A month later, Einstein's works were among those targeted by the

German Student Union

The German Student Union (german: Deutsche Studentenschaft, abbreviated ''DSt'') from 1919 until 1945, was the merger of the general student committees of all German universities, including Danzig, Austria and the former German universities in ...

in the Nazi book burnings, with Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels proclaiming, "Jewish intellectualism is dead." One German magazine included him in a list of enemies of the German regime with the phrase, "not yet hanged", offering a $5,000 bounty on his head.

In a subsequent letter to physicist and friend Max Born, who had already emigrated from Germany to England, Einstein wrote, "... I must confess that the degree of their brutality and cowardice came as something of a surprise." After moving to the US, he described the book burnings as a "spontaneous emotional outburst" by those who "shun popular enlightenment", and "more than anything else in the world, fear the influence of men of intellectual independence".

Einstein was now without a permanent home, unsure where he would live and work, and equally worried about the fate of countless other scientists still in Germany. Aided by the Council for At-Risk Academics, Academic Assistance Council, founded in April 1933 by British liberal politician William Beveridge to help academics escape Nazi persecution, Einstein was able to leave Germany.

He rented a house in De Haan, Belgium, where he lived for a few months. In late July 1933, he went to England for about six weeks at the personal invitation of British naval officer Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, who had become friends with Einstein in the preceding years. Locker-Lampson invited him to stay near his home in a wooden cabin on Roughton Heath in the Parish of . To protect Einstein, Locker-Lampson had two bodyguards watch over him at his secluded cabin; a photo of them carrying shotguns and guarding Einstein was published in the ''Daily Herald'' on 24 July 1933.

Locker-Lampson took Einstein to meet Winston Churchill at his home, and later, Austen Chamberlain and former Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Lloyd George. Einstein asked them to help bring Jewish scientists out of Germany. British historian Martin Gilbert notes that Churchill responded immediately, and sent his friend, physicist Frederick Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell, Frederick Lindemann, to Germany to seek out Jewish scientists and place them in British universities.

Churchill later observed that as a result of Germany having driven the Jews out, they had lowered their "technical standards" and put Allies of World War II, the Allies' technology ahead of theirs.

Einstein later contacted leaders of other nations, including Turkey's Prime Minister, İsmet İnönü, to whom he wrote in September 1933 requesting placement of unemployed German-Jewish scientists. As a result of Einstein's letter, Jewish invitees to Turkey eventually totaled over "1,000 saved individuals".

Locker-Lampson also submitted a bill to parliament to extend British citizenship to Einstein, during which period Einstein made a number of public appearances describing the crisis brewing in Europe. In one of his speeches he denounced Germany's treatment of Jews, while at the same time he introduced a bill promoting Jewish citizenship in Palestine, as they were being denied citizenship elsewhere.

In his speech he described Einstein as a "citizen of the world" who should be offered a temporary shelter in the UK.

Both bills failed, however, and Einstein then accepted an earlier offer from the

Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

, in Princeton, New Jersey, US, to become a resident scholar.

Resident scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study

On 3 October 1933, Einstein delivered a speech on the importance of academic freedom before a packed audience at the Royal Albert Hall in London, with ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' reporting he was wildly cheered throughout.

Four days later he returned to the US and took up a position at the Institute for Advanced Study, noted for having become a refuge for scientists fleeing Nazi Germany.

At the time, most American universities, including Harvard, Princeton and Yale, had minimal or no Jewish faculty or students, as a result of their Jewish quotas, which lasted until the late 1940s.

Einstein was still undecided on his future. He had offers from several European universities, including Christ Church, Oxford, where he stayed for three short periods between May 1931 and June 1933 and was offered a five-year research fellowship (called a "studentship" at Christ Church),

but in 1935, he arrived at the decision to remain permanently in the United States and apply for citizenship.

Einstein's affiliation with the Institute for Advanced Study would last until his death in 1955.

He was one of the four first selected (along with John von Neumann, Kurt Gödel, and Hermann Weyl) at the new Institute, where he soon developed a close friendship with Gödel. The two would take long walks together discussing their work. Bruria Kaufman, his assistant, later became a physicist. During this period, Einstein tried to develop a

unified field theory

In physics, a unified field theory (UFT) is a type of field theory that allows all that is usually thought of as fundamental forces and elementary particles to be written in terms of a pair of physical and virtual fields. According to the modern ...

and to refute the Copenhagen interpretation, accepted interpretation of quantum physics, both unsuccessfully.

World War II and the Manhattan Project

In 1939, a group of Hungarian scientists that included émigré physicist Leó Szilárd attempted to alert Washington to ongoing Nazi atomic bomb research. The group's warnings were discounted. Einstein and Szilárd, along with other refugees such as Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, "regarded it as their responsibility to alert Americans to the possibility that German scientists might win the German nuclear energy project, race to build an atomic bomb, and to warn that Hitler would be more than willing to resort to such a weapon."

To make certain the US was aware of the danger, in July 1939, a few months before the beginning of World War II in Europe, Szilárd and Wigner visited Einstein to explain the possibility of atomic bombs, which Einstein, a pacifist, said he had never considered.

He was asked to lend his support by writing

a letter, with Szilárd, to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Roosevelt, recommending the US pay attention and engage in its own nuclear weapons research.

The letter is believed to be "arguably the key stimulus for the U.S. adoption of serious investigations into nuclear weapons on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II".

In addition to the letter, Einstein used his connections with the Belgian Royal Family