exchanged transfusion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring

Historically,

Historically,

Before a blood transfusion is given, there are many steps taken to ensure quality of the blood products, compatibility, and safety to the recipient. In 2012, a national blood policy was in place in 70% of countries and 69% of countries had specific legislation that covers the safety and quality of blood transfusion.

Before a blood transfusion is given, there are many steps taken to ensure quality of the blood products, compatibility, and safety to the recipient. In 2012, a national blood policy was in place in 70% of countries and 69% of countries had specific legislation that covers the safety and quality of blood transfusion.

Donated blood is usually subjected to processing after it is collected, to make it suitable for use in specific patient populations. Collected blood is then separated into blood components by centrifugation:

Donated blood is usually subjected to processing after it is collected, to make it suitable for use in specific patient populations. Collected blood is then separated into blood components by centrifugation:

Before a recipient receives a transfusion, compatibility testing between donor and recipient blood must be done. The first step before a transfusion is given is to type and screen the recipient's blood. Typing of recipient's blood determines the ABO and Rh status. The sample is then screened for any alloantibodies that may react with donor blood.Blood Processing.

Before a recipient receives a transfusion, compatibility testing between donor and recipient blood must be done. The first step before a transfusion is given is to type and screen the recipient's blood. Typing of recipient's blood determines the ABO and Rh status. The sample is then screened for any alloantibodies that may react with donor blood.Blood Processing.

http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/TUTORIAL/BLDBANK/BBPROC.html

Accessed on: December 15, 2006. It takes about 45 minutes to complete (depending on the method used). The blood bank scientist also checks for special requirements of the patient (e.g. need for washed, irradiated or CMV negative blood) and the history of the patient to see if they have previously identified antibodies and any other serological anomalies. A positive screen warrants an antibody panel/investigation to determine if it is clinically significant. An antibody panel consists of commercially prepared group O red cell suspensions from donors that have been phenotyped for antigens that correspond to commonly encountered and clinically significant alloantibodies. Donor cells may have homozygous (e.g. K+k+), heterozygous (K+k-) expression or no expression of various antigens (K−k−). The phenotypes of all the donor cells being tested are shown in a chart. The patient's serum is tested against the various donor cells. Based on the reactions of the patient's serum against the donor cells, a pattern will emerge to confirm the presence of one or more antibodies. Not all antibodies are clinically significant (i.e. cause transfusion reactions, HDN, etc.). Once the patient has developed a clinically significant antibody it is vital that the patient receive antigen-negative red blood cells to prevent future transfusion reactions. A direct antiglobulin test (

A positive screen warrants an antibody panel/investigation to determine if it is clinically significant. An antibody panel consists of commercially prepared group O red cell suspensions from donors that have been phenotyped for antigens that correspond to commonly encountered and clinically significant alloantibodies. Donor cells may have homozygous (e.g. K+k+), heterozygous (K+k-) expression or no expression of various antigens (K−k−). The phenotypes of all the donor cells being tested are shown in a chart. The patient's serum is tested against the various donor cells. Based on the reactions of the patient's serum against the donor cells, a pattern will emerge to confirm the presence of one or more antibodies. Not all antibodies are clinically significant (i.e. cause transfusion reactions, HDN, etc.). Once the patient has developed a clinically significant antibody it is vital that the patient receive antigen-negative red blood cells to prevent future transfusion reactions. A direct antiglobulin test (

Working at the

Working at the

The science of blood transfusion dates to the first decade of the 20th century, with the discovery of distinct

The science of blood transfusion dates to the first decade of the 20th century, with the discovery of distinct

James Blundell, pioneer of blood transfusion

' British Journal of Hospital Medicine, August 2007, Vol 68, No 8. He made a substantial amount of money from this endeavour, roughly $2 million ($50 million real dollars). In 1840, at St George's Hospital Medical School in London,

Only in 1901, when the Austrian

Only in 1901, when the Austrian

While the first transfusions had to be made directly from donor to receiver before

While the first transfusions had to be made directly from donor to receiver before

''Toronto Star''. July 9, 2016. Katie Daubs Robertson published his findings in the ''

Robertson published his findings in the ''

The secretary of the

The secretary of the

The resulting dried plasma package came in two tin cans containing 400 mL bottles. One bottle contained enough

The resulting dried plasma package came in two tin cans containing 400 mL bottles. One bottle contained enough

Milk as a Substitute for Blood Transfusion

, historical account,

Transfusion Evidence Library

searchable source of evidence for transfusion medicine.

British Blood Transfusion Society

(BBTS)

International Society of Blood Transfusion

(ISBT)

''Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens''

Free online book at

''Handbook of Transfusion Medicine''

Free book published in the UK 5th edition

American Association of Blood Banks Clinical Practice Guidelines

Australian National Blood Authority Patient Blood Management Guidelines

* ttps://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng24 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Blood Transfusion GuidanceUK Guidance for transfusion.

Canadian Blood Transfusion Guidelines

German Medical Association Guidelines (English)

published 2014.

Blood Transfusion Leaflets

(NHS Blood and Transplant)

Blood Transfusion Leaflets

(Welsh Blood Service)

Blood Transfusion Information

(Scotland)

Blood Transfusion Information

(Australia)

(American Cancer Society) {{Authority control Transfusion medicine Hematology Blood

blood product

A blood product is any therapeutic substance prepared from human blood. This includes whole blood; blood components; and plasma derivatives. Whole blood is not commonly used in transfusion medicine. Blood components include: red blood cell concen ...

s into a person's circulation intravenous

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly used for rehydration or to provide nutrie ...

ly. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used whole blood

Whole blood (WB) is human blood from a standard blood donation. It is used in the treatment of massive bleeding, in exchange transfusion, and when people donate blood to themselves. One unit of whole blood (~517 mls) brings up hemoglobin lev ...

, but modern medical practice commonly uses only components of the blood, such as red blood cells

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek language, Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''k ...

, white blood cells

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mult ...

, plasma

Plasma or plasm may refer to:

Science

* Plasma (physics), one of the four fundamental states of matter

* Plasma (mineral), a green translucent silica mineral

* Quark–gluon plasma, a state of matter in quantum chromodynamics

Biology

* Blood pla ...

, clotting factors

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism ...

and platelets

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby ini ...

.

Red blood cells (RBC) contain hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

, and supply the cells of the body with oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

. White blood cells are not commonly used during transfusion, but they are part of the immune system, and also fight infections. Plasma is the "yellowish" liquid part of blood, which acts as a buffer, and contains proteins and important substances needed for the body's overall health. Platelets are involved in blood clotting, preventing the body from bleeding. Before these components were known, doctors believed that blood was homogeneous. Because of this scientific misunderstanding, many patients died because of incompatible blood transferred to them.

Medical uses

Red cell transfusion

Historically,

Historically, red blood cell transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used whole blood, but mo ...

was considered when the hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

level fell below 100g/L or hematocrit

The hematocrit () (Ht or HCT), also known by several other names, is the volume percentage (vol%) of red blood cells (RBCs) in blood, measured as part of a blood test. The measurement depends on the number and size of red blood cells. It is norm ...

fell below 30%. Because each unit of blood given carries risks, a trigger level lower than that, at 70 to 80g/L, is now usually used, as it has been shown to have better patient outcomes. The administration of a single unit of blood is the standard for hospitalized people who are not bleeding, with this treatment followed with re-assessment and consideration of symptoms and hemoglobin concentration. Patients with poor oxygen saturation

Oxygen saturation (symbol SO2) is a relative measure of the concentration of oxygen that is dissolved or carried in a given medium as a proportion of the maximal concentration that can be dissolved in that medium at the given temperature. It ca ...

may need more blood. The advisory caution to use blood transfusion only with more severe anemia

Anemia or anaemia (British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, or a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin. When anemia comes on slowly, th ...

is in part due to evidence that outcomes are worsened if larger amounts are given. One may consider transfusion for people with symptoms of cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, h ...

such as chest pain or shortness of breath. In cases where patients have low levels of hemoglobin due to iron deficiency, but are cardiovascularly stable, parenteral iron

Iron supplements, also known as iron salts and iron pills, are a number of iron formulations used to treat and prevent iron deficiency including iron deficiency anemia. For prevention they are only recommended in those with poor absorption, ...

is a preferred option based on both efficacy and safety. Other blood products are given where appropriate, e.g., to treat clotting deficiencies.

Procedure

Before a blood transfusion is given, there are many steps taken to ensure quality of the blood products, compatibility, and safety to the recipient. In 2012, a national blood policy was in place in 70% of countries and 69% of countries had specific legislation that covers the safety and quality of blood transfusion.

Before a blood transfusion is given, there are many steps taken to ensure quality of the blood products, compatibility, and safety to the recipient. In 2012, a national blood policy was in place in 70% of countries and 69% of countries had specific legislation that covers the safety and quality of blood transfusion.

Blood donation

Blood transfusions use as sources of blood either one's own (autologous

Autotransplantation is the transplantation of organs, tissues, or even particular proteins from one part of the body to another in the same person ('' auto-'' meaning "self" in Greek).

The autologous tissue (also called autogenous, autogene ...

transfusion), or someone else's (allogeneic

Allotransplant (''allo-'' meaning "other" in Greek) is the transplantation of cells, tissues, or organs to a recipient from a genetically non-identical donor of the same species. The transplant is called an allograft, allogeneic transplant, o ...

or homologous transfusion). The latter is much more common than the former. Using another's blood must first start with donation of blood. Blood is most commonly donated as whole blood

Whole blood (WB) is human blood from a standard blood donation. It is used in the treatment of massive bleeding, in exchange transfusion, and when people donate blood to themselves. One unit of whole blood (~517 mls) brings up hemoglobin lev ...

obtained intravenously and mixed with an anticoagulant

Anticoagulants, commonly known as blood thinners, are chemical substances that prevent or reduce coagulation of blood, prolonging the clotting time. Some of them occur naturally in blood-eating animals such as leeches and mosquitoes, where the ...

. In developed countries, donations are usually anonymous to the recipient, but products in a blood bank

A blood bank is a center where blood gathered as a result of blood donation is stored and preserved for later use in blood transfusion. The term "blood bank" typically refers to a department of a hospital usually within a Clinical Pathology laborat ...

are always individually traceable through the whole cycle of donation, testing, separation into components, storage, and administration to the recipient. This enables management and investigation of any suspected transfusion related disease transmission or transfusion reaction

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used whole blood, but mod ...

. In developing countries, the donor is sometimes specifically recruited by or for the recipient, typically a family member, and the donation occurs immediately before the transfusion.

It is unclear whether applying alcohol swab alone or alcohol swab followed by antiseptic is able to reduce contamination of donor's blood.

Processing and testing

red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s, plasma

Plasma or plasm may refer to:

Science

* Plasma (physics), one of the four fundamental states of matter

* Plasma (mineral), a green translucent silica mineral

* Quark–gluon plasma, a state of matter in quantum chromodynamics

Biology

* Blood pla ...

, platelet

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby ini ...

s, albumin

Albumin is a family of globular proteins, the most common of which are the serum albumins. All the proteins of the albumin family are water-soluble, moderately soluble in concentrated salt solutions, and experience heat denaturation. Albumins ...

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

, clotting factor concentrates, cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate, also called cryo for short, is a frozen blood product prepared from blood plasma. To create cryoprecipitate, fresh frozen plasma thawed to 1–6 °C is then centrifuged and the precipitate is collected. The precipitate is re ...

, fibrinogen

Fibrinogen (factor I) is a glycoprotein complex, produced in the liver, that circulates in the blood of all vertebrates. During tissue and vascular injury, it is converted enzymatically by thrombin to fibrin and then to a fibrin-based blood clo ...

concentrate, and immunoglobulin

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

s (antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

). Red cells, plasma and platelets can also be donated individually via a more complex process called apheresis

Apheresis ( ἀφαίρεσις (''aphairesis'', "a taking away")) is a medical technology in which the blood of a person is passed through an apparatus that separates out one particular constituent and returns the remainder to the circulation ...

.

* The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

(WHO) recommends that all donated blood be tested for transfusion-transmissible infections. These include HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune ...

, hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is an infectious disease caused by the ''Hepatitis B virus'' (HBV) that affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. It can cause both acute and chronic infection.

Many people have no symptoms during an initial infection. Fo ...

, hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that primarily affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. During the initial infection people often have mild or no symptoms. Occasionally a fever, dark urine, a ...

, ''Treponema pallidum

''Treponema pallidum'', formerly known as ''Spirochaeta pallida'', is a spirochaete bacterium with various subspecies that cause the diseases syphilis, bejel (also known as endemic syphilis), and yaws. It is transmitted only among humans. It is ...

'' (syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

) and, where relevant, other infections that pose a risk to the safety of the blood supply, such as ''Trypanosoma cruzi

''Trypanosoma cruzi'' is a species of parasitic euglenoids. Among the protozoa, the trypanosomes characteristically bore tissue in another organism and feed on blood (primarily) and also lymph. This behaviour causes disease or the likelihood of ...

'' (Chagas disease

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is a tropical parasitic disease caused by ''Trypanosoma cruzi''. It is spread mostly by insects in the subfamily ''Triatominae'', known as "kissing bugs". The symptoms change over the cou ...

) and ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a vert ...

'' species (malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

). According to the WHO, 25 countries are not able to screen all donated blood for one or more of: HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune ...

, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or syphilis. One of the main reasons for this is because testing kits are not always available. However the prevalence of transfusion-transmitted infections is much higher in low income countries compared to middle and high income countries.

* All donated blood should also be tested for the ABO blood group system

The ABO blood group system is used to denote the presence of one, both, or neither of the A and B antigens on erythrocytes. For human blood transfusions, it is the most important of the 43 different blood type (or group) classification system ...

and Rh blood group system

The Rh blood group system is a human blood group system. It contains proteins on the surface of red blood cells. After the ABO blood group system, it is the most likely to be involved in transfusion reactions. The Rh blood group system consists ...

to ensure that the patient is receiving compatible blood.

* In addition, in some countries platelet products are also tested for bacterial infections due to its higher inclination for contamination due to storage at room temperature. Presence of cytomegalovirus

''Cytomegalovirus'' (''CMV'') (from ''cyto-'' 'cell' via Greek - 'container' + 'big, megalo-' + -''virus'' via Latin 'poison') is a genus of viruses in the order ''Herpesvirales'', in the family ''Herpesviridae'', in the subfamily ''Betaherpe ...

(CMV) may also be tested because of the risk to certain immunocompromised recipients if given, such as those with organ transplant or HIV. However, not all blood is tested for CMV because only a certain amount of CMV-negative blood needs to be available to supply patient needs. Other than positivity for CMV, any products tested positive for infections are not used.

* Leukocyte reduction is the removal of white blood cells by filtration. Leukoreduced blood products are less likely to cause HLA alloimmunization

Alloimmunity (sometimes called isoimmunity) is an immune response to nonself antigens from members of the same species, which are called alloantigens or isoantigens. Two major types of alloantigens are blood group antigens and histocompatibility ...

(development of antibodies against specific blood types), febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reaction

Febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reaction (FNHTR) is the most common type of transfusion reaction. It is a benign occurrence with symptoms that include fever but not directly related with hemolysis. It is caused by cytokine release from leukocytes ...

, cytomegalovirus infection

''Cytomegalovirus'' (''CMV'') (from ''cyto-'' 'cell' via Greek - 'container' + 'big, megalo-' + -''virus'' via Latin 'poison') is a genus of viruses in the order ''Herpesvirales'', in the family ''Herpesviridae'', in the subfamily ''Betaherpe ...

, and platelet-transfusion refractoriness

Platelet transfusion refractoriness is the repeated failure to achieve the desired level of blood platelets in a patient following a platelet blood transfusion, transfusion. The cause of refractoriness may be either immune system, immune or non-imm ...

.

* Pathogen Reduction treatment that involves, for example, the addition of riboflavin

Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, is a vitamin found in food and sold as a dietary supplement. It is essential to the formation of two major coenzymes, flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide. These coenzymes are involved in ...

with subsequent exposure to UV light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

has been shown to be effective in inactivating pathogens (viruses, bacteria, parasites and white blood cells) in blood products. By inactivating white blood cells in donated blood products, riboflavin and UV light treatment can also replace gamma-irradiation as a method to prevent graft-versus-host disease (TA-GvHD

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GvHD) is a rare complication of blood transfusion, in which the immunologically competent donor T lymphocytes mount an immune response against the recipient's lymphoid tissue. These donor lymphoc ...

).

Compatibility testing

Before a recipient receives a transfusion, compatibility testing between donor and recipient blood must be done. The first step before a transfusion is given is to type and screen the recipient's blood. Typing of recipient's blood determines the ABO and Rh status. The sample is then screened for any alloantibodies that may react with donor blood.Blood Processing.

Before a recipient receives a transfusion, compatibility testing between donor and recipient blood must be done. The first step before a transfusion is given is to type and screen the recipient's blood. Typing of recipient's blood determines the ABO and Rh status. The sample is then screened for any alloantibodies that may react with donor blood.Blood Processing. University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

. Available athttp://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/TUTORIAL/BLDBANK/BBPROC.html

Accessed on: December 15, 2006. It takes about 45 minutes to complete (depending on the method used). The blood bank scientist also checks for special requirements of the patient (e.g. need for washed, irradiated or CMV negative blood) and the history of the patient to see if they have previously identified antibodies and any other serological anomalies.

A positive screen warrants an antibody panel/investigation to determine if it is clinically significant. An antibody panel consists of commercially prepared group O red cell suspensions from donors that have been phenotyped for antigens that correspond to commonly encountered and clinically significant alloantibodies. Donor cells may have homozygous (e.g. K+k+), heterozygous (K+k-) expression or no expression of various antigens (K−k−). The phenotypes of all the donor cells being tested are shown in a chart. The patient's serum is tested against the various donor cells. Based on the reactions of the patient's serum against the donor cells, a pattern will emerge to confirm the presence of one or more antibodies. Not all antibodies are clinically significant (i.e. cause transfusion reactions, HDN, etc.). Once the patient has developed a clinically significant antibody it is vital that the patient receive antigen-negative red blood cells to prevent future transfusion reactions. A direct antiglobulin test (

A positive screen warrants an antibody panel/investigation to determine if it is clinically significant. An antibody panel consists of commercially prepared group O red cell suspensions from donors that have been phenotyped for antigens that correspond to commonly encountered and clinically significant alloantibodies. Donor cells may have homozygous (e.g. K+k+), heterozygous (K+k-) expression or no expression of various antigens (K−k−). The phenotypes of all the donor cells being tested are shown in a chart. The patient's serum is tested against the various donor cells. Based on the reactions of the patient's serum against the donor cells, a pattern will emerge to confirm the presence of one or more antibodies. Not all antibodies are clinically significant (i.e. cause transfusion reactions, HDN, etc.). Once the patient has developed a clinically significant antibody it is vital that the patient receive antigen-negative red blood cells to prevent future transfusion reactions. A direct antiglobulin test (Coombs test

A Coombs test, also known as antiglobulin test (AGT), is either of two blood tests used in immunohematology. They are the direct and indirect Coombs tests. The direct Coombs test detects antibodies that are stuck to the surface of the red blood ce ...

) is also performed as part of the antibody investigation.

If there is no antibody present, an immediate spin crossmatch or computer-assisted crossmatch is performed where the recipient serum and donor rbc are incubated. In the immediate spin method, two drops of patient serum are tested against a drop of 3–5% suspension of donor cells in a test tube and spun in a serofuge. Agglutination or hemolysis (i.e., positive Coombs test) in the test tube is a positive reaction and the unit should not be transfused.

If an antibody is suspected, potential donor units must first be screened for the corresponding antigen by phenotyping them. Antigen negative units are then tested against the patient plasma using an antiglobulin/indirect crossmatch technique at 37 degrees Celsius to enhance reactivity and make the test easier to read.

In urgent cases where crossmatching cannot be completed, and the risk of dropping hemoglobin outweighs the risk of transfusing uncrossmatched blood, O-negative blood is used, followed by crossmatch as soon as possible. O-negative is also used for children and women of childbearing age. It is preferable for the laboratory to obtain a pre-transfusion sample in these cases so a type and screen can be performed to determine the actual blood group of the patient and to check for alloantibodies.

Compatibility of ABO and Rh system for Red Cell (Erythrocyte) Transfusion

This chart shows possible matches in blood transfusion between donor and receiver using ABO and Rh system.Adverse effects

In the same way that the safety of pharmaceutical products is overseen bypharmacovigilance

Term Given By Tushar Sharma (UPES Batch 2025)

Pharmacovigilance (PV, or PhV), also known as drug safety, is the pharmaceutical science relating to the "collection, detection, assessment, monitoring, and prevention" of adverse effects with pharma ...

, the safety of blood and blood products is overseen by haemovigilance. This is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a system "...to identify and prevent occurrence or recurrence of transfusion related unwanted events, to increase the safety, efficacy and efficiency of blood transfusion, covering all activities of the transfusion chain from donor to recipient." The system should include monitoring, identification, reporting, investigation and analysis of adverse events near-misses and reactions related to transfusion and manufacturing. In the UK this data is collected by an independent organisation called SHOT (Serious Hazards Of Transfusion).

Transfusions of blood products are associated with several complications, many of which can be grouped as immunological or infectious. There is controversy on potential quality degradation during storage.

Immunologic reaction

* Acute hemolytic reactions are defined according to Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) as "fever and other symptoms/signs of haemolysis within 24 hours of transfusion; confirmed by one or more of the following: a fall of Hb, rise in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT), positive crossmatch" This is due to destruction of donor red blood cells by preformed recipient antibodies. Most often this occurs because of clerical errors or improper ABO blood typing and crossmatching resulting in a mismatch in ABO blood type between the donor and the recipient. Symptoms include fever, chills, chest pain, back pain, hemorrhage,increased heart rate

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal (su ...

, shortness of breath, and rapid drop in blood pressure. When suspected, transfusion should be stopped immediately, and blood sent for tests to evaluate for presence of hemolysis. Treatment is supportive. Kidney injury may occur because of the effects of the hemolytic reaction (pigment nephropathy). The severity of the transfusion reaction is depended upon amount of donor's antigen transfused, nature of the donor's antigens, the nature and the amount of recipient antibodies.

* Delayed hemolytic reactions occur more than 24 hours after a transfusion. They usually occur within 28 days of a transfusion. They can be due to either a low level of antibodies present prior to the start of the transfusion, which are not detectable on pre-transfusion testing; or development of a new antibody against an antigen in the transfused blood. Therefore, delayed haemolytic reaction does not manifest until after 24 hours when enough antibodies are available to cause a reaction. The red blood cells are removed by macrophages from the blood circulation into liver and spleen to be destroyed, which leads to extravascular haemolysis. This process usually mediated by anti-Rh and anti-Kidd antibodies. However, this type of transfusion reaction is less severe when compared to acute haemolytic transfusion reaction.

* Febrile nonhemolytic reactions are, along with allergic transfusion reactions, the most common type of blood transfusion reaction and occur because of the release of inflammatory chemical signals released by white blood cells in stored donor blood or attack on donor's white blood cells by recipient's antibodies. This type of reaction occurs in about 7% of transfusions. Fever is generally short lived and is treated with antipyretic

An antipyretic (, from ''anti-'' 'against' and ' 'feverish') is a substance that reduces fever. Antipyretics cause the hypothalamus to override a prostaglandin-induced increase in temperature. The body then works to lower the temperature, which r ...

s, and transfusions may be finished as long as an acute hemolytic reaction is excluded. This is a reason for the now-widespread use of leukoreduction – the filtration of donor white cells from red cell product units.

* Allergic transfusion reaction An allergic transfusion reaction is when a blood transfusion results in allergic reaction. It is among the most common transfusion reactions to occur. Reported rates depend on the degree of active surveillance versus passing reporting to the blood ...

s are caused by IgE anti-allergen antibodies. When antibodies are bound to its antigens, histamine

Histamine is an organic nitrogenous compound involved in local immune responses, as well as regulating physiological functions in the gut and acting as a neurotransmitter for the brain, spinal cord, and uterus. Since histamine was discovered in ...

is released from mast cell

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a par ...

s and basophil

Basophils are a type of white blood cell. Basophils are the least common type of granulocyte, representing about 0.5% to 1% of circulating white blood cells. However, they are the largest type of granulocyte. They are responsible for inflammator ...

s. Either IgE antibodies from the donor's or recipient's side can cause the allergic reaction. It is more common in patients who have allergic conditions such as hay fever

Allergic rhinitis, of which the seasonal type is called hay fever, is a type of inflammation in the nose that occurs when the immune system overreacts to allergens in the air. Signs and symptoms include a runny or stuffy nose, sneezing, red, i ...

. Patient may feel itchy or having hives but the symptoms are usually mild and can be controlled by stopping the transfusion and giving antihistamine

Antihistamines are drugs which treat allergic rhinitis, common cold, influenza, and other allergies. Typically, people take antihistamines as an inexpensive, generic (not patented) drug that can be bought without a prescription and provides re ...

s.

* Anaphylactic reactions are rare life-threatening allergic conditions caused by IgA anti-plasma protein antibodies. For patients who have selective immunoglobulin A deficiency

Selective immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency (SIgAD) is a genetic immunodeficiency, a type of hypogammaglobulinemia. People with this deficiency lack immunoglobulin A (IgA), a type of antibody that protects against infections of the mucous membran ...

, the reaction is presumed to be caused by IgA antibodies in the donor's plasma. The patient may present with symptoms of fever, wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and circulatory shock

Shock is the state of insufficient blood flow to the Tissue (biology), tissues of the body as a result of problems with the circulatory system. Initial symptoms of shock may include weakness, fast heart rate, fast breathing, sweating, anxiety, a ...

. Urgent treatment with epinephrine

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands and ...

is needed.

* Post-transfusion purpura Post-transfusion purpura (PTP) is a delayed adverse reaction to a blood transfusion or platelet transfusion that occurs when the body has produced alloantibodies to the allogeneic transfused platelets' antigens. These alloantibodies destroy the pat ...

is an extremely rare complication that occurs after blood product transfusion and is associated with the presence of antibodies in the patient's blood directed against both the donor's and recipient's platelets HPA (human platelet antigen). Recipients who lack this protein develop sensitization to this protein from prior transfusions or previous pregnancies, can develop thrombocytopenia, bleeding into the skin, and can display purplish discolouration of skin which is known as purpura

Purpura () is a condition of red or purple discolored spots on the skin that do not blanch on applying pressure. The spots are caused by bleeding underneath the skin secondary to platelet disorders, vascular disorders, coagulation disorders, ...

. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is treatment of choice.

* Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) is a syndrome that is similar to acute respiratory distress syndrome

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a type of respiratory failure characterized by rapid onset of widespread inflammation in the lungs. Symptoms include shortness of breath (dyspnea), rapid breathing (tachypnea), and bluish skin colo ...

(ARDS), which develops during or within 6 hours of transfusion of a plasma-containing blood product. Fever, hypotension, shortness of breath, and tachycardia often occurs in this type of reaction. For a definitive diagnosis to be made, symptoms must occur within 6 hours of transfusion, hypoxemia must be present, there must be radiographic evidence of bilateral infiltrates and there must be no evidence of left atrial hypertension (fluid overload). It occurs in 15% of the transfused patient with mortality rate of 5 to 10%. Recipient risk factors includes: end-stage liver disease, sepsis, haematological malignancies, sepsis, and ventilated patients. Antibodies to human neutrophil antigens (HNA) and human leukocyte antigens (HLA) have been associated with this type of transfusion reaction. Donor's antibodies interacting with antigen positive recipient tissue result in release of inflammatory cytokines, resulting in pulmonary capillary leakage. The treatment is supportive.

* Transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a common, yet underdiagnosed, reaction to blood product transfusion consisting of the new onset or exacerbation of three of the following within 6 hours of cessation of transfusion: acute respiratory distress, elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), elevated central venous pressure (CVP), evidence of left heart failure, evidence of positive fluid balance, and/or radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema.

* Transfusion-associated graft versus host disease

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GvHD) is a rare complication of blood transfusion, in which the immunologically competent donor T lymphocytes mount an immune response against the recipient's lymphoid tissue. These donor lympho ...

frequently occurs in immunodeficient patients where recipient's body failed to eliminate donor's T cells. Instead, donor's T cells attack the recipient's cells. It occurs one week after transfusion. Fever, rash, diarrhoea are often associated with this type of transfusion reaction. Mortality rate is high, with 89.7% of the patients dead after 24 days. Immunosuppressive treatment is the most common way of treatment. Irradiation and leukoreduction of blood products is necessary for high risk patients to prevent T cells from attacking recipient cells.

Infection

The use of greater amount of red blood cells is associated with a high risk of infections. In those who were given red blood only with significant anemia infection rates were 12% while in those who were given red blood at milder levels of anemia infection rates were 17%. On rare occasions, blood products are contaminated with bacteria. This can result in a life-threatening infection known as transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection. The risk of severe bacterial infection is estimated, , at about 1 in 50,000 platelet transfusions, and 1 in 500,000 red blood cell transfusions. Blood product contamination, while rare, is still more common than actual infection. The reason platelets are more often contaminated than other blood products is that they are stored at room temperature for short periods of time. Contamination is also more common with longer duration of storage, especially if that means more than 5 days. Sources of contaminants include the donor's blood, donor's skin, phlebotomist's skin, and containers. Contaminating organisms vary greatly, and include skin flora, gut flora, and environmental organisms. There are many strategies in place at blood donation centers and laboratories to reduce the risk of contamination. A definite diagnosis of transfusion-transmitted bacterial infection includes the identification of a positive culture in the recipient (without an alternative diagnosis) as well as the identification of the same organism in the donor blood. Since the advent of HIV testing of donor blood in the mid/later 1980s, ex. 1985'sELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence ...

, the transmission of HIV during transfusion has dropped dramatically. Prior testing of donor blood only included testing for antibodies to HIV. However, because of latent infection (the "window period" in which an individual is infectious, but has not had time to develop antibodies) many cases of HIV seropositive blood were missed. The development of a nucleic acid test for the HIV-1 RNA has dramatically lowered the rate of donor blood seropositivity to about 1 in 3 million units. As transmittance of HIV does not necessarily mean HIV infection, the latter could still occur at an even lower rate.

The transmission of hepatitis C via transfusion currently stands at a rate of about 1 in 2 million units. As with HIV, this low rate has been attributed to the ability to screen for both antibodies as well as viral RNA nucleic acid testing in donor blood.

Other rare transmissible infections include hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is an infectious disease caused by the ''Hepatitis B virus'' (HBV) that affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. It can cause both acute and chronic infection.

Many people have no symptoms during an initial infection. Fo ...

, syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

, Chagas disease

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is a tropical parasitic disease caused by ''Trypanosoma cruzi''. It is spread mostly by insects in the subfamily ''Triatominae'', known as "kissing bugs". The symptoms change over the cou ...

, cytomegalovirus

''Cytomegalovirus'' (''CMV'') (from ''cyto-'' 'cell' via Greek - 'container' + 'big, megalo-' + -''virus'' via Latin 'poison') is a genus of viruses in the order ''Herpesvirales'', in the family ''Herpesviridae'', in the subfamily ''Betaherpe ...

infections (in immunocompromised recipients), HTLV

The human T-lymphotropic virus, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, or human T-cell leukemia-lymphoma virus (HTLV) family of viruses are a group of human retroviruses that are known to cause a type of cancer called adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma an ...

, and Babesia

''Babesia'', also called ''Nuttallia'', is an apicomplexan parasite that infects red blood cells and is transmitted by ticks. Originally discovered by the Romanian bacteriologist Victor Babeș in 1888, over 100 species of ''Babesia'' have since ...

.

Comparison table

Inefficacy

Transfusion inefficacy or insufficient efficacy of a given unit(s) of blood product, while not itself a "complication" ''per se'', can nonetheless indirectly lead to complications – in addition to causing a transfusion to fully or partly fail to achieve its clinical purpose. This can be especially significant for certain patient groups such as critical-care or neonatals. For red blood cells (RBC), by far the most commonly transfused product, poor transfusion efficacy can result from units damaged by the so-called storage lesion – a range of biochemical and biomechanical changes that occur during storage. With red cells, this can decrease viability and ability for tissue oxygenation. Although some of the biochemical changes are reversible after the blood is transfused, the biomechanical changes are less so, and rejuvenation products are not yet able to adequately reverse this phenomenon. There has been controversy about whether a given product unit's age is a factor in transfusion efficacy, specifically about whether "older" blood directly or indirectly increases risks of complications. Studies have not been consistent on answering this question, with some showing that older blood is indeed less effective but with others showing no such difference; these developments are being closely followed by hospitalblood bank

A blood bank is a center where blood gathered as a result of blood donation is stored and preserved for later use in blood transfusion. The term "blood bank" typically refers to a department of a hospital usually within a Clinical Pathology laborat ...

ers – who are the physicians, typically pathologists, who collect and manage inventories of transfusable blood units.

Certain regulatory measures are in place to minimize RBC storage lesion – including a maximum shelf life (currently 42 days), a maximum auto-hemolysis threshold (currently 1% in the US, 0.8% in Europe), and a minimum level of post-transfusion RBC survival ''in vivo'' (currently 75% after 24 hours). However, all of these criteria are applied in a universal manner that does not account for differences among units of product. For example, testing for the post-transfusion RBC survival ''in vivo'' is done on a sample of healthy volunteers, and then compliance is presumed for all RBC units based on universal (GMP) processing standards (RBC survival by itself does not guarantee efficacy, but it is a necessary prerequisite for cell function, and hence serves as a regulatory proxy). Opinions vary as to the "best" way to determine transfusion efficacy in a patient ''in vivo''. In general, there are not yet any ''in vitro'' tests to assess quality or predict efficacy for specific units of RBC blood product prior to their transfusion, though there is exploration of potentially relevant tests based on RBC membrane properties such as erythrocyte deformability Erythrocyte deformability refers to the ability of erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBC) to change shape under a given level of applied stress, without hemolysing (rupturing). This is an important property because erythrocytes must change their shape ...

and erythrocyte fragility

Erythrocyte fragility refers to the propensity of erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBC) to hemolyse (rupture) under stress. It can be thought of as the degree or proportion of hemolysis that occurs when a sample of red blood cells are subjected to ...

(mechanical).

Physicians have adopted a so-called "restrictive protocol" – whereby transfusion is held to a minimum – in part because of the noted uncertainties surrounding storage lesion, in addition to the very high direct and indirect costs of transfusions. However, the restrictive protocol is not an option with some especially vulnerable patients who may require the best possible efforts to rapidly restore tissue oxygenation.

Although transfusions of platelets are far less numerous (relative to RBC), platelet storage lesion and resulting efficacy loss is also a concern.

Other

* A known relationship between intra-operative blood transfusion and cancer recurrence has been established in colorectal cancer. In lung cancer intra-operative blood transfusion has been associated with earlier recurrence of cancer, worse survival rates and poorer outcomes after lung resection. Also studies shown to us, failure of theimmune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

caused by blood transfusion can be categorized as one of the main factors leading to more than 10 different cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

types that are fully associated with blood transfusion and the innate and adaptive immune system. Allogeneic blood transfusion, through five major mechanisms including the lymphocyte-T set, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophage Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are a class of immune cells present in high numbers in the microenvironment of solid tumors. They are heavily involved in cancer-related inflammation. Macrophages are known to originate from bone marrow-derived bl ...

s (TAMs), natural killer cells

Natural killer cells, also known as NK cells or large granular lymphocytes (LGL), are a type of cytotoxic lymphocyte critical to the innate immune system that belong to the rapidly expanding family of known innate lymphoid cells (ILC) and represen ...

(NKCs), and dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. The ...

(DCs) can help the recipient's defense mechanisms. On the other hand, the role for each of the listed items includes activation of the antitumor

Cancer can be treated by surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy (including immunotherapy such as monoclonal antibody therapy) and synthetic lethality, most commonly as a series of separate treatments (e.g. ...

CD8+

A cytotoxic T cell (also known as TC, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL, T-killer cell, cytolytic T cell, CD8+ T-cell or killer T cell) is a T lymphocyte (a type of white blood cell) that kills cancer cells, cells that are infected by intracellular pa ...

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

A cytotoxic T cell (also known as TC, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL, T-killer cell, cytolytic T cell, CD8+ T-cell or killer T cell) is a T lymphocyte (a type of white blood cell) that kills cancer cells, cells that are infected by intracellular pa ...

(CD8+/CTL), temporal inactivation of Tregs, inactivation of the STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a transcription factor which in humans is encoded by the ''STAT3'' gene. It is a member of the STAT protein family.

Function

STAT3 is a member of the STAT protein family. In respons ...

signaling pathway, the use of bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

to enhance the antitumor immune response

An immune response is a reaction which occurs within an organism for the purpose of defending against foreign invaders. These invaders include a wide variety of different microorganisms including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi which could ...

and cellular Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy or biological therapy is the treatment of disease by activating or suppressing the immune system. Immunotherapies designed to elicit or amplify an immune response are classified as ''activation immunotherapies,'' while immunotherap ...

.

* Transfusion-associated volume overload is a common complication simply because blood products have a certain amount of volume. This is especially the case in recipients with underlying cardiac or kidney disease. Red cell transfusions can lead to volume overload when they must be repeated because of insufficient efficacy (see above). Plasma transfusion is especially prone to causing volume overload because large volumes are usually required to give any therapeutic benefit.

* It has been proved that blood transfusion produce worse outcomes after cytoreductive surgery Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is a surgical procedure that aims to reduce the amount of cancer cells in the abdominal cavity for patients with tumors that have spread intraabdominally (peritoneal carcinomatosis). It is often used to treat ovarian can ...

and HIPEC.

* Hypothermia can occur with transfusions with large quantities of blood products which normally are stored at cold temperatures. Core body temperature can go down as low as 32 °C and can produce physiologic disturbances. Prevention should be done with warming the blood to ambient temperature prior to transfusions.

* Transfusions with large amounts of red blood cells, whether due to severe hemorrhaging and/or transfusion inefficacy (see above), can lead to an inclination for bleeding. The mechanism is thought to be due to disseminated intravascular coagulation, along with dilution of recipient platelets and coagulation factors. Close monitoring and transfusions with platelets and plasma is indicated when necessary.

* Metabolic alkalosis can occur with massive blood transfusions because of the breakdown of citrate stored in blood into bicarbonate.

* Hypocalcemia can also occur with massive blood transfusions because of the complex of citrate with serum calcium. Calcium levels below 0.9 mmol/L should be treated.

* Blood doping

Blood doping is a form of doping in which the number of red blood cells in the bloodstream is boosted in order to enhance athletic performance. Because such blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to the muscles, a higher concentration in the bl ...

is often used by athletes, drug addicts or military personnel for reasons such as to increase physical stamina, to fake a drug detection test or simply to remain active and alert during the duty-times respectively. However a lack of knowledge and insufficient experience can turn a blood transfusion into a sudden death. For example, when individuals run the frozen blood sample directly in their veins this cold blood rapidly reaches the heart, where it disturbs the heart's original pace leading to cardiac arrest and sudden death.

Frequency of use

Globally around 85 million units of red blood cells are transfused in a given year. In the United States, blood transfusions were performed nearly 3 million times during hospitalizations in 2011, making it the most common procedure performed. The rate of hospitalizations with a blood transfusion nearly doubled from 1997, from a rate of 40 stays to 95 stays per 10,000 population. It was the most common procedure performed for patients 45 years of age and older in 2011, and among the top five most common for patients between the ages of 1 and 44 years. According to the ''New York Times'': "Changes in medicine have eliminated the need for millions of blood transfusions, which is good news for patients getting procedures like coronary bypasses and other procedures that once required a lot of blood." And, "Blood bank revenue is falling, and the decline may reach $1.5 billion a year this year 014from a high of $5 billion in 2008." Job losses will reach as high as 12,000 within the next three to five years, roughly a quarter of the total in the industry, according to the Red Cross.History

Beginning withWilliam Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and proper ...

's experiments on the circulation of blood, recorded research into blood transfusion began in the 17th century, with successful experiments in transfusion between animals. However, successive attempts by physicians to transfuse animal blood into humans gave variable, often fatal, results.

Pope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII ( la, Innocentius VIII; it, Innocenzo VIII; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death in July 1492. Son of th ...

is sometimes said to have been given "the world's first blood transfusion" by his physician Giacomo di San Genesio, who had him drink (by mouth) the blood of three 10-year-old boys. The boys subsequently died. The evidence for this story, however, is unreliable and considered a possible anti-Jewish blood libel.

Early attempts

The Incas The first reported successful blood transfusions were performed by theIncas

The Inca Empire (also Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift, known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechuan languages, Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) wa ...

as early as the 1500s. Spanish conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

s witnessed blood transfusions when they arrived in the sixteenth century. The prevalence of type O blood

The ABO blood group system is used to denote the presence of one, both, or neither of the A and B antigens on erythrocytes. For human blood transfusions, it is the most important of the 43 different blood type (or group) classification system ...

among Indigenous people of the Andean region meant such procedures would have held less risk than blood transfusion attempts among populations with incompatible blood types, which contributed to the failures of early attempts in Europe.

Animal blood

Working at the

Working at the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in the 1660s, the physician Richard Lower began examining the effects of changes in blood volume on circulatory function and developed methods for cross-circulatory study in animals, obviating clotting by closed arteriovenous connections. The new instruments he was able to devise enabled him to perform the first reliably documented successful transfusion of blood in front of his distinguished colleagues from the Royal Society.

According to Lower's account, "...towards the end of February 1665 selected one dog of medium size, opened its jugular vein, and drew off blood, until its strength was nearly gone. Then, to make up for the great loss of this dog by the blood of a second, I introduced blood from the cervical artery of a fairly large mastiff, which had been fastened alongside the first, until this latter animal showed ... it was overfilled ... by the inflowing blood." After he "sewed up the jugular veins", the animal recovered "with no sign of discomfort or of displeasure".

Lower had performed the first blood transfusion between animals. He was then "requested by the Honorable obertBoyle ... to acquaint the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

with the procedure for the whole experiment", which he did in December 1665 in the Society's ''Philosophical Transactions

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the first journa ...

''.

The first blood transfusion from animal to human was administered by Dr. Jean-Baptiste Denys

Jean-Baptiste Denys (1643 – 3 October 1704) was a French physician notable for having performed the first fully documented human blood transfusion, a xenotransfusion. He studied in Montpellier and was the personal physician to King Louis ...

, eminent physician to King Louis XIV of France, on June 15, 1667. He transfused the blood of a sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

into a 15-year-old boy, who survived the transfusion. Denys performed another transfusion into a labourer, who also survived. Both instances were likely due to the small amount of blood that was actually transfused into these people. This allowed them to withstand the allergic reaction

Allergies, also known as allergic diseases, refer a number of conditions caused by the hypersensitivity of the immune system to typically harmless substances in the environment. These diseases include hay fever, food allergies, atopic derma ...

.

Denys's third patient to undergo a blood transfusion was Swedish Baron Gustaf Bonde. He received two transfusions. After the second transfusion Bonde died. In the winter of 1667, Denys performed several transfusions on Antoine Mauroy with calf's blood. On the third account Mauroy died.

Six months later in London, Lower performed the first human transfusion of animal blood in Britain, where he "superintended the introduction in patient'sarm at various times of some ounces of sheep's blood at a meeting of the Royal Society, and without any inconvenience to him." The recipient was Arthur Coga, "the subject of a harmless form of insanity." Sheep's blood was used because of speculation about the value of blood exchange between species; it had been suggested that blood from a gentle lamb might quiet the tempestuous spirit of an agitated person and that the shy might be made outgoing by blood from more sociable creatures. Coga received 20 shillings () to participate in the experiment.

Lower went on to pioneer new devices for the precise control of blood flow and the transfusion of blood; his designs were substantially the same as modern syringe

A syringe is a simple reciprocating pump consisting of a plunger (though in modern syringes, it is actually a piston) that fits tightly within a cylindrical tube called a barrel. The plunger can be linearly pulled and pushed along the inside ...

s and catheter

In medicine, a catheter (/ˈkæθətər/) is a thin tube made from medical grade materials serving a broad range of functions. Catheters are medical devices that can be inserted in the body to treat diseases or perform a surgical procedure. Cath ...

s. Shortly after, Lower moved to London, where his growing practice soon led him to abandon research.

These early experiments with animal blood provoked a heated controversy in Britain and France. Finally, in 1668, the Royal Society and the French government both banned the procedure. The Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

condemned these experiments in 1670. Blood transfusions fell into obscurity for the next 150 years.

Human blood

The science of blood transfusion dates to the first decade of the 20th century, with the discovery of distinct

The science of blood transfusion dates to the first decade of the 20th century, with the discovery of distinct blood types

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the ci ...

leading to the practice of mixing some blood from the donor and the receiver before the transfusion (an early form of cross-matching

Cross-matching or crossmatching is a test performed before a blood transfusion as part of blood compatibility testing. Normally, this involves adding the recipient's blood plasma to a sample of the donor's red blood cells. If the blood is incom ...

).

In the early 19th century, British obstetrician

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgi ...

Dr. James Blundell made efforts to treat hemorrhage

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

by transfusion of human blood using a syringe. In 1818 following experiments with animals, he performed the first successful transfusion of human blood to treat postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum bleeding or postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is often defined as the loss of more than 500 ml or 1,000 ml of blood following childbirth. Some have added the requirement that there also be signs or symptoms of low blood volume for ...

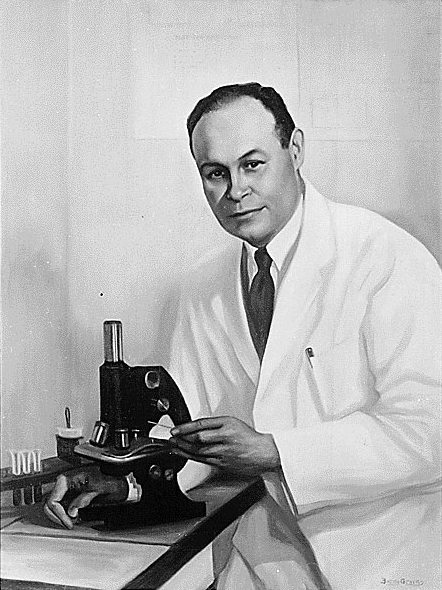

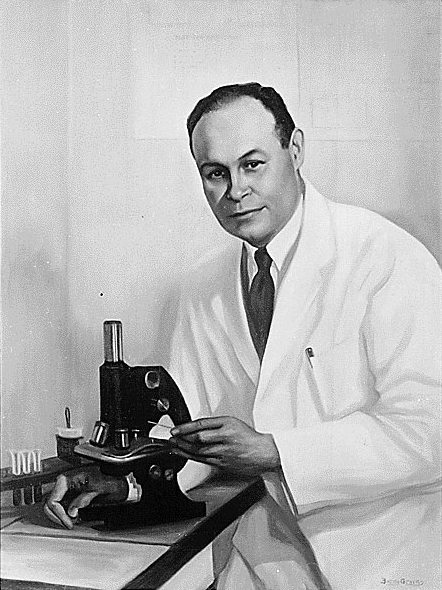

. Blundell used the patient's husband as a donor, and extracted four ounces of blood from his arm to transfuse into his wife. During the years 1825 and 1830, Blundell performed 10 transfusions, five of which were beneficial, and published his results. He also invented a number of instruments for the transfusion of blood.Ellis, H. ''Surgical AnniversariesJames Blundell, pioneer of blood transfusion

' British Journal of Hospital Medicine, August 2007, Vol 68, No 8. He made a substantial amount of money from this endeavour, roughly $2 million ($50 million real dollars). In 1840, at St George's Hospital Medical School in London,

Samuel Armstrong Lane

Samuel Armstrong Lane FRCS (1802 – 2 August 1892) was an English surgeon, consulting surgeon to St Mary's Hospital.

In 1840 while practicing in London England, Samuel Armstrong Lane, aided by consultant Dr. Blundell, performed the first succ ...

, aided by Blundell, performed the first successful whole blood transfusion to treat haemophilia

Haemophilia, or hemophilia (), is a mostly inherited genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, a process needed to stop bleeding. This results in people bleeding for a longer time after an injury, easy bruising, ...

.

However, early transfusions were risky and many resulted in the death of the patient. By the late 19th century, blood transfusion was regarded as a risky and dubious procedure, and was largely shunned by the medical establishment.

Work to emulate James Blundell continued in Edinburgh. In 1845 the Edinburgh Journal described the successful transfusion of blood to a woman with severe uterine bleeding. Subsequent transfusions were successful with patients of Professor James Young Simpson after whom the Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion

The Edinburgh Royal Maternity and Simpson Memorial Pavilion was a maternity hospital in Lauriston, Edinburgh, Scotland. Its services have now been incorporated into the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh at Little France.

History

Midwifery in Edinbu ...

in Edinburgh was named.

Various isolated reports of successful transfusions emerged towards the end of the 19th century. The largest series of early successful transfusions took place at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

between 1885 and 1892. Edinburgh later became the home of the first blood donation and blood transfusion services.

20th century

Only in 1901, when the Austrian

Only in 1901, when the Austrian Karl Landsteiner

Karl Landsteiner (; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-born American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He distinguished the main blood groups in 1900, having developed the modern system of classification of blood groups from ...

discovered three human blood groups

The term human blood group systems is defined by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) as systems in the human species where cell-surface antigens—in particular, those on blood cells—are "controlled at a single gene locus or by ...

(O, A, and B), did blood transfusion achieve a scientific basis and become safer.

Landsteiner discovered that adverse effects arise from mixing blood from two incompatible individuals. He found that mixing incompatible types triggers an immune response and the red blood-cells clump. The immunological reaction occurs when the receiver of a blood transfusion has antibodies against the donor blood-cells. The destruction of red blood cells releases free hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

into the bloodstream, which can have fatal consequences. Landsteiner's work made it possible to determine blood group and allowed blood transfusions to take place much more safely. For his discovery he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1930; many other blood groups have been discovered since.

George Washington Crile

George Washington Crile (November 11, 1864 – January 7, 1943) was an American surgeon. Crile is now formally recognized as the first surgeon to have succeeded in a direct blood transfusion. He contributed to other procedures, such as neck dis ...

is credited with performing the first surgery using a direct blood transfusion in 1906 at St. Alexis Hospital in Cleveland while a professor of surgery at Case Western Reserve University

Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is a private research university in Cleveland, Ohio. Case Western Reserve was established in 1967, when Western Reserve University, founded in 1826 and named for its location in the Connecticut Western Reser ...

.

Jan Janský

Jan Janský () (3 April 1873 in Smíchov, now Prague – 8 September 1921 in Černošice, near Prague) was a Czech serologist, neurologist and psychiatrist. He is credited with the classification of blood into four types (I, II, III, IV).Book ...

also discovered the human blood groups; in 1907 he classified blood into four groups: I, II, III, IV. His nomenclature is still used in Russia and in states of the former USSR, in which blood types O, A, B, and AB are respectively designated I, II, III, and IV.

Dr. William Lorenzo Moss's (1876–1957) Moss-blood typing technique of 1910 was widely used until World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

William Stewart Halsted

William Stewart Halsted, M.D. (September 23, 1852 – September 7, 1922) was an American surgeon who emphasized strict aseptic technique during surgical procedures, was an early champion of newly discovered anesthetics, and introduced several ...

, M.D. (1852–1922), an American surgeon, performed one of the first blood transfusions in the United States. He had been called to see his sister after she had given birth. He found her moribund from blood loss, and in a bold move withdrew his own blood, transfused his blood into his sister, and then operated on her to save her life.

Blood banks in WWI

While the first transfusions had to be made directly from donor to receiver before

While the first transfusions had to be made directly from donor to receiver before coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

, it was discovered that by adding anticoagulant

Anticoagulants, commonly known as blood thinners, are chemical substances that prevent or reduce coagulation of blood, prolonging the clotting time. Some of them occur naturally in blood-eating animals such as leeches and mosquitoes, where the ...

and refrigerating

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

the blood it was possible to store it for some days, thus opening the way for the development of blood bank

A blood bank is a center where blood gathered as a result of blood donation is stored and preserved for later use in blood transfusion. The term "blood bank" typically refers to a department of a hospital usually within a Clinical Pathology laborat ...

s. John Braxton Hicks

John Braxton Hicks (23 February 1823 – 28 August 1897) was a 19th-century English doctor who specialised in obstetrics.

He was born to Edward Hicks in Rye, Sussex. He was educated privately and in 1841 entered Guy's Hospital Medical S ...

was the first to experiment with chemical methods to prevent the coagulation of blood at St Mary's Hospital, London