European colonization on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The historical phenomenon of

The historical phenomenon of

Some commentators identify three waves of European colonialism.

The three main countries in the first wave of European colonialism were

Some commentators identify three waves of European colonialism.

The three main countries in the first wave of European colonialism were

The Territorial changes of Russia happened by means of military conquest and by ideological and political unions over the centuries. This section covers (1533–1914).

The Territorial changes of Russia happened by means of military conquest and by ideological and political unions over the centuries. This section covers (1533–1914).

European colonization of both Eastern and

European colonization of both Eastern and  As characteristically happens in any colonialism, European or not, previous or subsequent, both Spain and Portugal profited handsomely from their newfound overseas colonies: the Spanish from gold and silver from mines such as

As characteristically happens in any colonialism, European or not, previous or subsequent, both Spain and Portugal profited handsomely from their newfound overseas colonies: the Spanish from gold and silver from mines such as

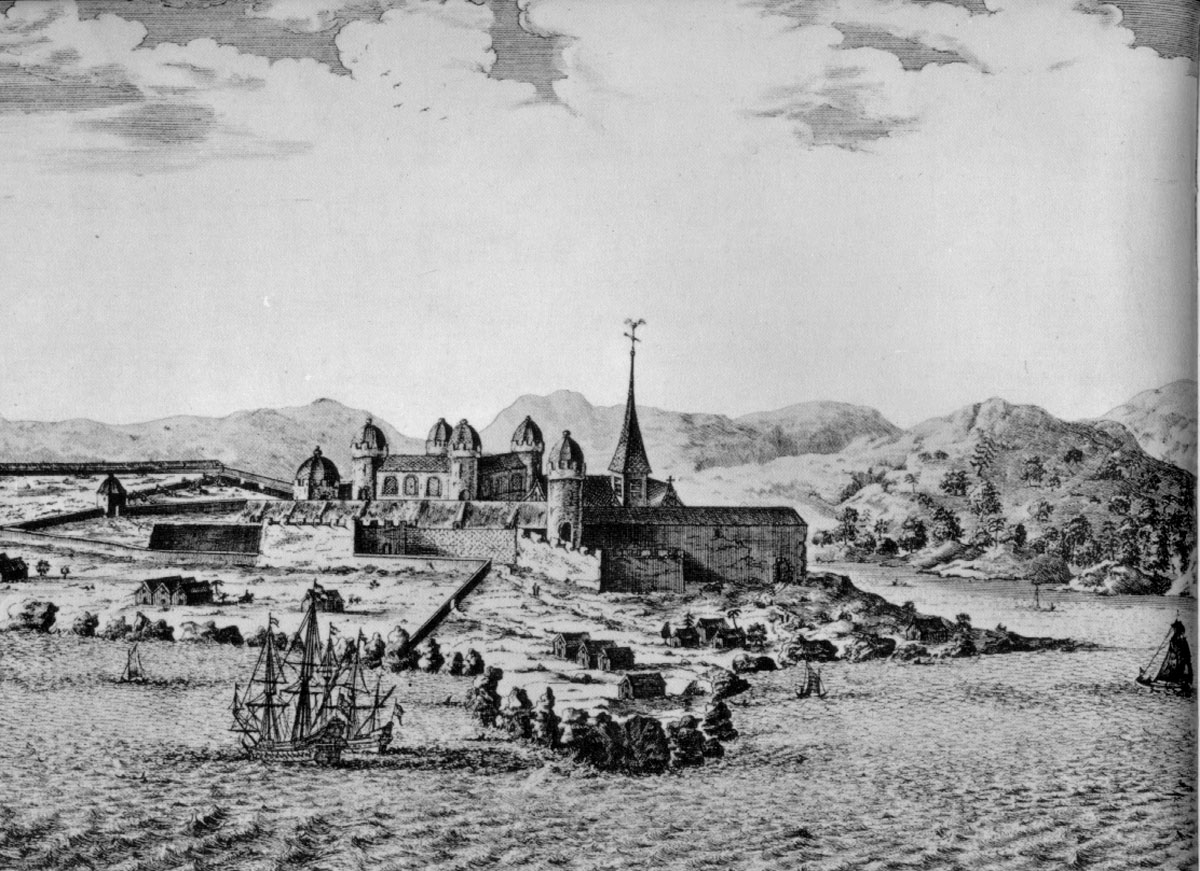

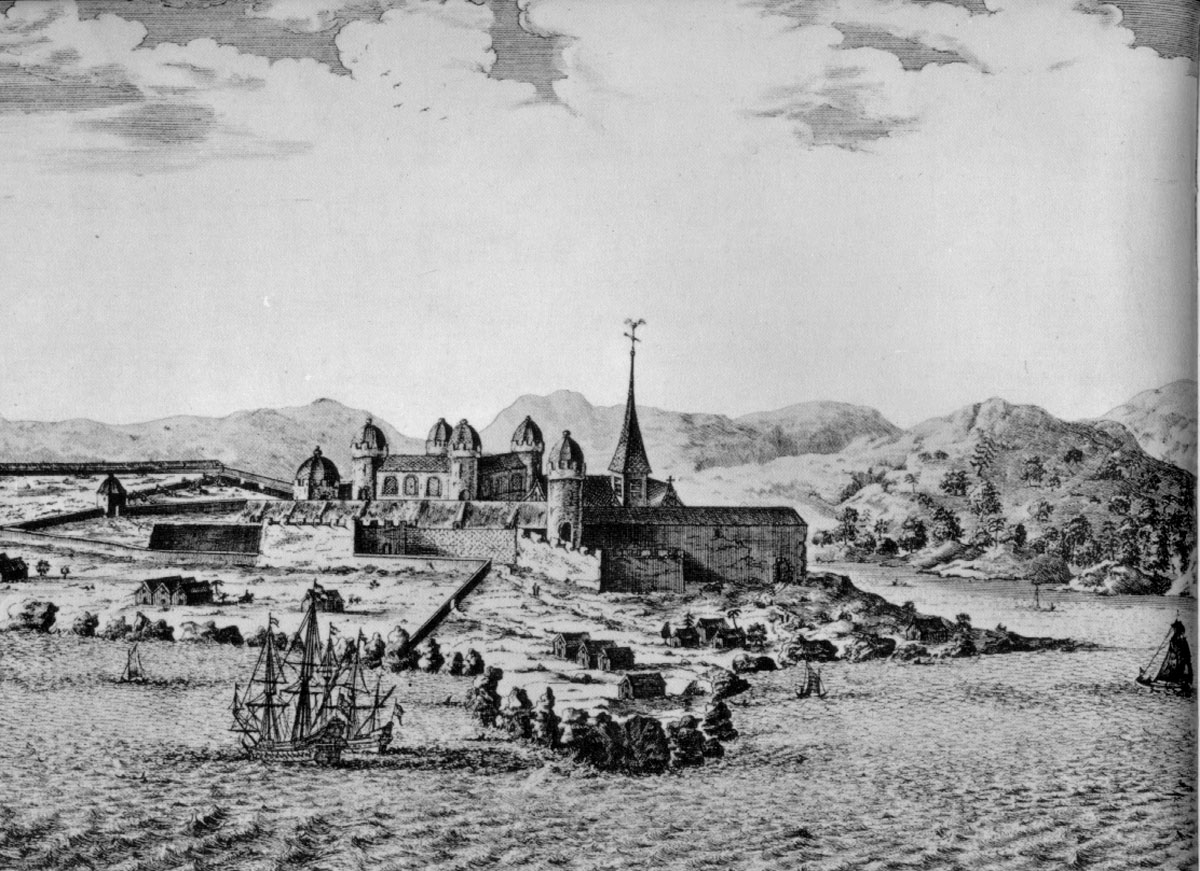

In May 1498, the Portuguese set foot in

In May 1498, the Portuguese set foot in

The historical phenomenon of

The historical phenomenon of colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their hist ...

, the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, Albania, Greeks in Italy, ...

, the Turks, and the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

.

Colonialism in the modern sense began with the "Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafari ...

", led by Portuguese, who became increasingly adventuresome following the conquest of Ceuta

The conquest of Ceuta by the Portuguese on 21 August 1415 marks an important step in the beginning of the Portuguese Empire in Africa.

History

In 711, shortly after the Arab conquest of North Africa, the city of Ceuta was used as a stagi ...

in 1415, aiming to control navigation through the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaism, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, expand Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, obtain plunder, and suppress predation on Portuguese populations by Barbary pirates as part of a longstanding African slave trade

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean ...

; at that point a minor trade, one the Portuguese would soon reverse and surpass. Around 1450, based on North African fishing boats, a lighter ship was developed, the caravel

The caravel ( Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing ...

, which could sail further and faster, was highly maneuverable, and could sail " into the wind".

Enabled by new nautical technology, with the added incentive to find an alternative " Silk Road" after the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

in 1453 to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

effectively closed profitable trade routes with Asia, early European exploration of Africa

The geography of North Africa has been reasonably well known among Europeans since classical antiquity in Greco-Roman geography. Northwest Africa (the Maghreb) was known as either ''Libya'' or ''Africa'', while Egypt was considered part of Asia.

...

was followed by the Spanish exploration of the Americas, further exploration along the coasts of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and explorations of Southwest Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

(also known as the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

), India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, and East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

.

The Conquest of the Canary Islands

The conquest of the Canary Islands by the Crown of Castille took place between 1402 and 1496 and described as the first instance of European settler colonialism in Africa. It can be divided into two periods: the Conquista señorial, carried out ...

by the Crown of Castille

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accessi ...

, from 1402 to 1496, has been described as the first instance of European settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a structure that perpetuates the elimination of Indigenous people and cultures to replace them with a settler society. Some, but not all, scholars argue that settler colonialism is inherently genocidal. It may be enacted b ...

in Africa. In 1462, the previously uninhabited Cape Verde archipelago

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

became the first European settlement in the tropics, and thereafter a site of Jewish exile during the height of the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Cathol ...

in the 1490s; the Portuguese soon also brought slaves from the West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mau ...

n coast. Because of the economics of plantations, especially sugar, European colonial expansion and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

would remain linked into the 1800s. The use of exile to penal colonies

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

would also continue.

The European discovery of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

, as named by Amerigo Vespucci in 1503, opened another colonial chapter, beginning with the colonization of the Caribbean in 1493 with Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and t ...

(later to become Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

). The Portuguese and Spanish empires were the first global empires

Several empires in human history have been contenders for the largest of all time, depending on definition and mode of measurement. Possible ways of measuring size include area, population, economy, and power. Of these, area is the most commonly ...

because they were the first to stretch across different continents (discounting Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

n empires), covering vast territories around the globe. Between 1580 and 1640, the Portuguese and Spanish empires were both ruled by the Spanish monarchs in personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more State (polity), states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some e ...

. During the late 16th and 17th centuries, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, France and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

also established their own overseas empires, in direct competition with one another.

The end of the 18th and mid 19th century saw the first era of decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

, when most of the European colonies in the Americas, notably those of Spain, New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to King ...

and the 13 colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

, gained their independence from their metropole

A metropole (from the Greek ''metropolis'' for "mother city") is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of ...

. The Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, w ...

(uniting Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

and England), France, Portugal, and the Dutch turned their attention to the Old World, particularly South Africa, India and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, where coastal enclaves had already been established.

The second industrial revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardization, mass production and industrialization from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The Fi ...

, in the 19th century, led to what has been termed the era of New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

, when the pace of colonization rapidly accelerated, the height of which was the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ( ...

, in which Belgium, Germany and Italy were also participants.

There were deadly battles between colonizing states and revolutions from colonized areas shaping areas of control and establishing independent nations. During the 20th century, the colonies of the defeated central powers in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

were distributed amongst the victors as mandates, but it was not until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

that the second phase of decolonization began in earnest.

Periodisation

Some commentators identify three waves of European colonialism.

The three main countries in the first wave of European colonialism were

Some commentators identify three waves of European colonialism.

The three main countries in the first wave of European colonialism were Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and the early Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The Portuguese started the long age of European colonization with the conquest of Ceuta, Morocco in 1415, and the conquest and discovery of other African territories and islands, this would also start the movement known as the Age of Discoveries. The Ottomans conquered South Eastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croa ...

, the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

and much of Northern and Eastern Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

between 1359 and 1653 – with the latter territories subjected to colonial occupation, rather than traditional territorial conquest. The Spanish and Portuguese launched the colonization of the Americas, basing their territorial claims on the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

of 1494. This treaty demarcated the respective spheres of influence of Spain and Portugal.

The expansion achieved by Spain and Portugal caught the attention of Britain, France, and the Netherlands. The entrance of these three powers into the Caribbean and North America perpetuated European colonialism in these regions.Gilmartin, M. (2009). Colonialism/Imperialism. In ''Key concepts in political geography'' London: SAGE pp. 115–123.

The second wave of European colonialism commenced with Britain's involvement in Asia in support of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sout ...

; other countries such as France, Portugal and the Netherlands also had involvement in European expansion in Asia.

The third wave

Third wave may refer to:

* Third-wave feminism, diverse strains of feminist activity in the early 1990s

* Third wave ska, a musical genre

* ''Third Wave'' (The Telescopes album), a 2002 studio album by The Telescopes

* Third Wave of the Holy Spiri ...

("New Imperialism") consisted of the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ( ...

regulated by the terms of the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergen ...

of 1884–1885. The conference effectively divided Africa among the European powers. Vast regions of Africa came under the sway of Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Italy and Spain.

Gilmartin argues that these three waves of colonialism were linked to capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

. The first wave of European expansion involved exploring the world to find new revenue and perpetuating European feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

. The second wave focused on developing the mercantile

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

capitalism system and the manufacturing industry in Europe. The last wave of European colonialism solidified all capitalistic endeavours by providing new markets and raw materials.

As a result of these waves of European colonial expansion, only thirteen present-day independent countries escaped formal colonization by European powers: Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

, Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountai ...

, China, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

, Japan, Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and southwest. It ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 millio ...

, Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is ma ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and ...

, Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

, South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

as well as North Yemen, the former independent country which is now part of Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

.

Imperial Russia

Ivan III

Ivan III Vasilyevich (russian: Иван III Васильевич; 22 January 1440 – 27 October 1505), also known as Ivan the Great, was a Grand Prince of Moscow and Grand Prince of all Rus'. Ivan served as the co-ruler and regent for his bl ...

(reigned 1462–1505) and Vasili III (reigned 1505–1533) had already expanded Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

*Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domest ...

's (1283–1547) borders considerably by annexing the Novgorod Republic

The Novgorod Republic was a medieval state that existed from the 12th to 15th centuries, stretching from the Gulf of Finland in the west to the northern Ural Mountains in the east, including the city of Novgorod and the Lake Ladoga regions of ...

(1478), the Grand Duchy of Tver in 1485, the Pskov Republic

Pskov ( la, Plescoviae), known at various times as the Principality of Pskov (russian: Псковское княжество, ) or the Pskov Republic (russian: Псковская Республика, ), was a medieval state on the south shore of ...

in 1510, the Appanage of Volokolamsk in 1513, and the principalities of Ryazan

Ryazan ( rus, Рязань, p=rʲɪˈzanʲ, a=ru-Ryazan.ogg) is the largest city and administrative center of Ryazan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Oka River in Central Russia, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 Cens ...

in 1521 and Novgorod-Seversky in 1522.

After a period of political instability, 1598 to 1613 the Romanovs

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastacia of Russia, Anastasi ...

came to power (1613) and the expansion-colonization process of the Tsardom continued. While western Europe colonized the New World, Russia expanded overland – to the east, north and south. This continued for centuries; by the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

reached from the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

to the Pacific Ocean, and for some time included colonies in the Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S ...

(1732–1867) and a short-lived unofficial colony in Africa (1889) in present-day Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Re ...

.

The acquisition of new territories, especially in the Caucasus, had an invigorating effect on the rest of Russia. According to two Russian historians:

: the culture of Russia and that of the Caucasian peoples interacted in a reciprocally beneficial manner. The turbulent tenor of life in the Caucasus, the mountain peoples' love of freedom, and their willingness to die for independence were felt far beyond the local interaction of the Caucasian peoples and coresident Russians: they injected a potent new spirit into the thinking and creative work of Russia's progressives, strengthened the liberationist aspirations of Russian writers and exiled Decembrists, and influenced distinguished Russian democrats, poets, and prose writers, including Alexander Griboyedov, Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

, Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (; russian: Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjurʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲɛrməntəf; – ) was a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasu ...

, and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. These writers, who generally supported the Caucasian fight for liberation, went beyond the chauvinism of the colonial autocracy and rendered the Caucasian peoples' cultures accessible to the Russian intelligentsia. At the same time, Russian culture exerted an influence on Caucasian cultures, bolstering positive aspects while weakening the impact of the Caucasian peoples' reactionary feudalism and reducing the internecine fighting between tribes and clans.

Expansion into Asia

The first stage to 1650 was an expansion eastward from theUral Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

to the Pacific Ocean. Geographical expeditions mapped much of Siberia. The second stage from 1785 to 1830 looked south to the areas between the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

and the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad s ...

. The key areas were Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

, with some better penetration of the Ottoman Empire, and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

. By 1829, Russia controlled all of the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

as shown in the Treaty of Adrianople of 1829. The third era, 1850 to 1860, was a brief interlude jumping to the East Coast, annexing the region from the Amur River

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeastern China ( Inner Manchuria). The Amur proper is long ...

to Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

. The fourth era, 1865 to 1885 incorporated Turkestan, and the northern approaches to India, sparking British fears of a threat to India in The Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

.

Portuguese and Spanish exploration and colonization

European colonization of both Eastern and

European colonization of both Eastern and Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, th ...

s has its roots in Portuguese exploration. There were financial and religious motives behind this exploration. By finding the source of the lucrative spice trade, the Portuguese could reap its profits for themselves. They would also be able to probe the existence of the fabled Christian kingdom of Prester John

Prester John ( la, Presbyter Ioannes) was a legendary Christian patriarch, presbyter, and king. Stories popular in Europe in the 12th to the 17th centuries told of a Nestorian patriarch and king who was said to rule over a Christian nation lost a ...

, with an eye to encircling the Islamic Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, itself gaining territories and colonies in Eastern Europe. The first foothold outside of Europe was gained with the conquest of Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territo ...

in 1415. During the 15th century, Portuguese sailors discovered the Atlantic islands of Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, Azores

)

, motto=

( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem=( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, and Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, which were duly populated, and pressed progressively further along the west African coast until Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( 1450 – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lay in the o ...

demonstrated it was possible to sail around Africa by rounding the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

in 1488, paving the way for Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

to reach India in 1498.

Portuguese successes led to Spanish financing of a mission by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

in 1492 to explore an alternative route to Asia, by sailing west. When Columbus eventually made landfall in the Caribbean Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

he believed he had reached the coast of India, and that the people he encountered there were Indians with red skin. This is why Native Americans have been called Indians or red-Indians. In truth, Columbus had arrived on a continent that was new to the Europeans, the Americas. After Columbus' first trips, competing Spanish and Portuguese claims to new territories and sea routes were solved with the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

in 1494, which divided the world outside of Europe in two areas of trade and exploration, between the Iberian kingdoms of Castile and Portugal along a north-south meridian, 370 leagues west of Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

. According to this international agreement, the larger part of the Americas and the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

were open to Spanish exploration and colonization, while Africa, the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

, and most of Asia were assigned to Portugal.

The boundaries specified by the Treaty of Tordesillas were put to the test in 1521 when Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

and his Spanish sailors (among other Europeans), sailing for the Spanish Crown became the first European to cross the Pacific Ocean, reaching Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic ce ...

and the Philippines, parts of which the Portuguese had already explored, sailing from the Indian Ocean. The two by now global empires, which had set out from opposing directions, had finally met on the other side of the world. The conflicts that arose between both powers were finally solved with the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, which defined the areas of Spanish and Portuguese influence in Asia, establishing the anti-meridian, or line of demarcation on the other side of the world.

During the 16th century the Portuguese continued to press both eastwards and westwards into the Oceans. Towards Asia they made the first direct contact between Europeans and the peoples inhabiting present day countries such as Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Mala ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-we ...

(1512), China, and finally Japan. In the opposite direction, the Portuguese colonized the huge territory that eventually became Brasil, and the Spanish conquistadores established the vast Viceroyalties of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, and later of Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (, "river of silver"), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and f ...

(Argentina) and New Granada New Granada may refer to various former national denominations for the present-day country of Colombia.

*New Kingdom of Granada, from 1538 to 1717

*Viceroyalty of New Granada, from 1717 to 1810, re-established from 1816 to 1819

*United Provinces of ...

(Colombia). In Asia, the Portuguese encountered ancient and well populated societies, and established a seaborne empire consisting of armed coastal trading posts along their trade routes (such as Goa, Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site s ...

and Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

), so they had relatively little cultural impact on the societies they engaged. In the Western Hemisphere, the European colonization involved the emigration of large numbers of settlers, soldiers and administrators intent on owning land and exploiting the apparently primitive (as perceived by Old World standards) indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

. The result was that the colonization of the New World was catastrophic: native peoples were no match for European technology, ruthlessness, or their diseases which decimated the indigenous population.

Spanish treatment of the indigenous populations caused a fierce debate, the Valladolid Controversy, over whether Indians possessed souls and if so, whether they were entitled to the basic rights of mankind. Bartolomé de Las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, Dominican Order, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish Empire, Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman ...

, author of ''A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''ae ...

'', championed the cause of the native peoples, and was opposed by Sepúlveda, who claimed Amerindians

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

were "natural slaves".

The Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

played a large role in Spanish and Portuguese overseas activities. The Dominicans, Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, and Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

, notably Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier (born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta; Latin: ''Franciscus Xaverius''; Basque: ''Frantzisko Xabierkoa''; French: ''François Xavier''; Spanish: ''Francisco Javier''; Portuguese: ''Francisco Xavier''; 7 April 15063 December ...

in Asia and Junípero Serra

Junípero Serra y Ferrer (; ; ca, Juníper Serra i Ferrer; November 24, 1713August 28, 1784) was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Order. He is credited with establishing the Franciscan Missions in the Sier ...

in North America, were particularly active in this endeavour. Many buildings erected by the Jesuits still stand, such as the Cathedral of Saint Paul in Macau and the Santisima Trinidad de Paraná in Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

, the latter an example of the Jesuit Reductions. The Dominican and Franciscan buildings of California's missions and New Mexico's missions stand restored, such as Mission Santa Barbara in Santa Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning "Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West Coa ...

and San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico

Ranchos de Taos is a census-designated place (CDP) in Taos County, New Mexico. The population was 2,390 at the time of the 2000 census.

The historic district is the Ranchos de Taos Plaza, which includes the San Francisco de Asis Mission Ch ...

.

Potosí

Potosí, known as Villa Imperial de Potosí in the colonial period, is the capital city and a municipality of the Department of Potosí in Bolivia. It is one of the highest cities in the world at a nominal . For centuries, it was the location o ...

and Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

, the Portuguese from the huge markups they enjoyed as trade intermediaries, particularly during the Nanban Japan trade period. The influx of precious metals to the Spanish monarchy's coffers allowed it to finance costly religious war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to w ...

s in Europe which ultimately proved its economic undoing: the supply of metals was not infinite and the large inflow caused inflation and debt, and subsequently affected the rest of Europe.

Northern European challenges to the Iberian hegemony

It was not long before the exclusivity of Iberian claims to the Americas was challenged by other up and coming European powers, primarily the Netherlands, France and England: the view taken by the rulers of these nations is epitomized by the quotation attributed toFrancis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin onc ...

demanding to be shown the clause in Adam's will excluding his authority from the New World. This challenge initially took the form of piratical attacks (such as those by Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 ...

) on Spanish treasure fleets or coastal settlements. Later the Northern European countries began establishing settlements of their own, primarily in areas that were outside of Spanish interests, such as what is now the eastern seaboard of the United States and Canada, or islands in the Caribbean, such as Aruba, Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island and an Overseas department and region, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of ...

and Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate ...

, that had been abandoned by the Spanish in favor of the mainland and larger islands.

Whereas Spanish colonialism was based on the religious conversion and exploitation of local populations via encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

s (many Spaniards emigrated to the Americas to elevate their social status, and were not interested in manual labor), Northern European colonialism was bolstered by those emigrating for religious reasons (for example, the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'' voyage). The motive for emigration was not to become an aristocrat or to spread one's faith but to start a new society afresh, structured according to the colonist's wishes. The most populous emigration of the 17th century was that of the English, who after a series of wars with the Dutch and French came to dominate the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

on the eastern coast of the present-day United States and other colonies such as Newfoundland and Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land ...

in what is now Canada.

However, the English, French and Dutch were no more averse to making a profit than the Spanish and Portuguese, and whilst their areas of settlement in the Americas proved to be devoid of the precious metals found by the Spanish, trade in other commodities and products that could be sold at a massive profit in Europe provided another reason for crossing the Atlantic, in particular, furs from Canada, tobacco, and cotton grown in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

and sugar in the islands of the Caribbean and Brazil. Due to the massive depletion of indigenous labor, plantation owners had to look elsewhere for manpower for these labour-intensive crops. They turned to the centuries-old slave trade of west Africa and began transporting Africans across the Atlantic on a massive scale – historians estimate that the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

brought between 10 and 12 million black African slaves to the New World. The islands of the Caribbean soon came to be populated by slaves of African descent, ruled over by a white minority of plantation owners interested in making a fortune and then returning to their home country to spend it.

Role of companies in early colonialism

From its very outset, Western colonialism was operated as a joint public-private venture. Columbus' voyages to the Americas were partially funded by Italian investors, but whereas the Spanish state maintained a tight rein on trade with its colonies (by law, the colonies could only trade with one designated port in the mother country and treasure was brought back in special convoys), the English, French and Dutch granted what were effectively trade monopolies to joint-stock companies such as the East India Companies and theHudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trade, fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake b ...

.

Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. T ...

had no state-sponsored expeditions or colonization in the Americas, but did charter the first Russian joint-stock commercial enterprise, the Russian America Company, which did sponsor those activities in its territories.

European colonies in India

In May 1498, the Portuguese set foot in

In May 1498, the Portuguese set foot in Kozhikode

Kozhikode (), also known in English as Calicut, is a city along the Malabar Coast in the state of Kerala in India. It has a corporation limit population of 609,224 and a metropolitan population of more than 2 million, making it the second l ...

in Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South C ...

, making them the first Europeans to sail to India. Rivalry among reigning European powers saw the entry of the Dutch, English, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Danish and others. The kingdoms of