Equatoguinean Politicians Convicted Of Crimes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

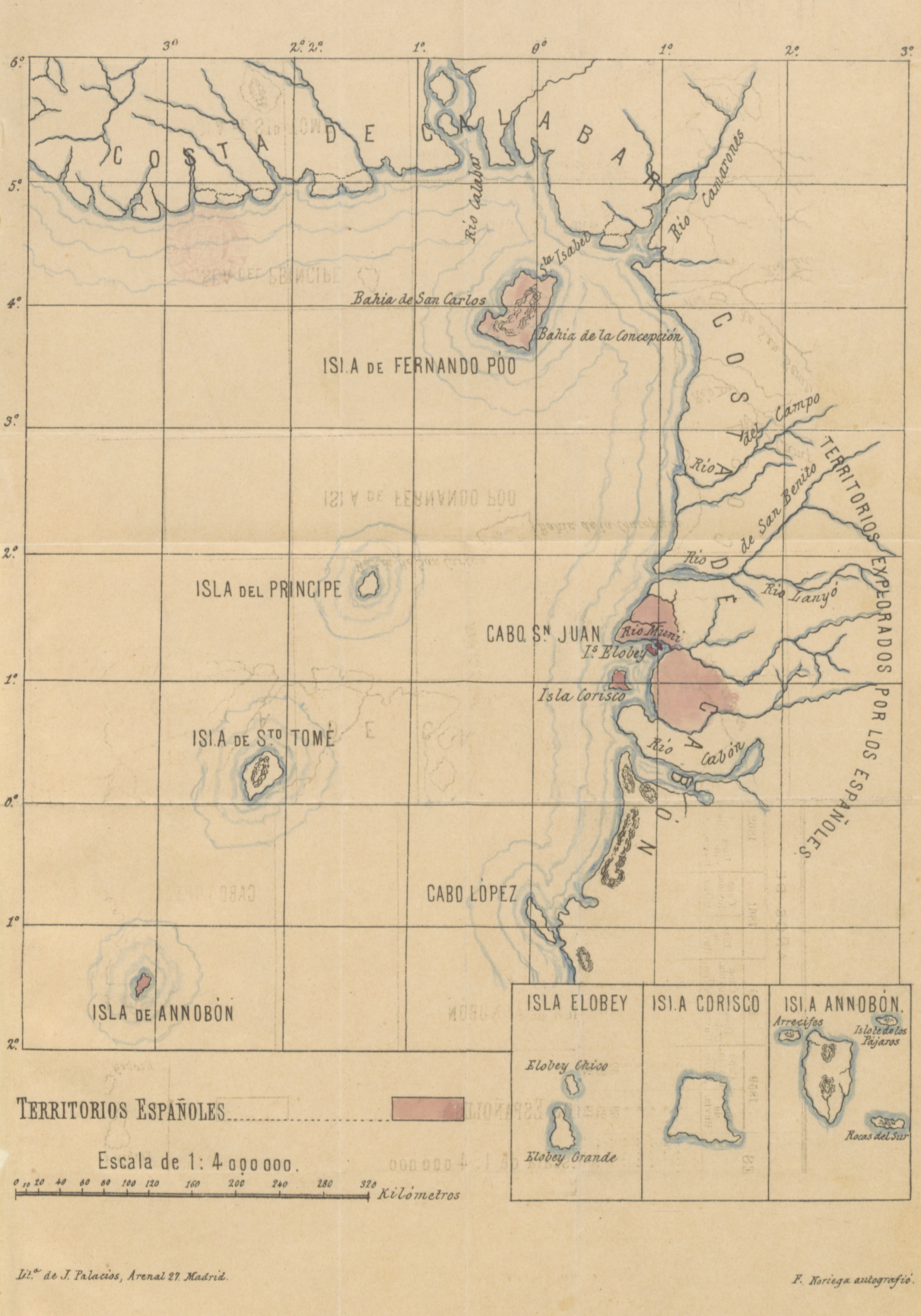

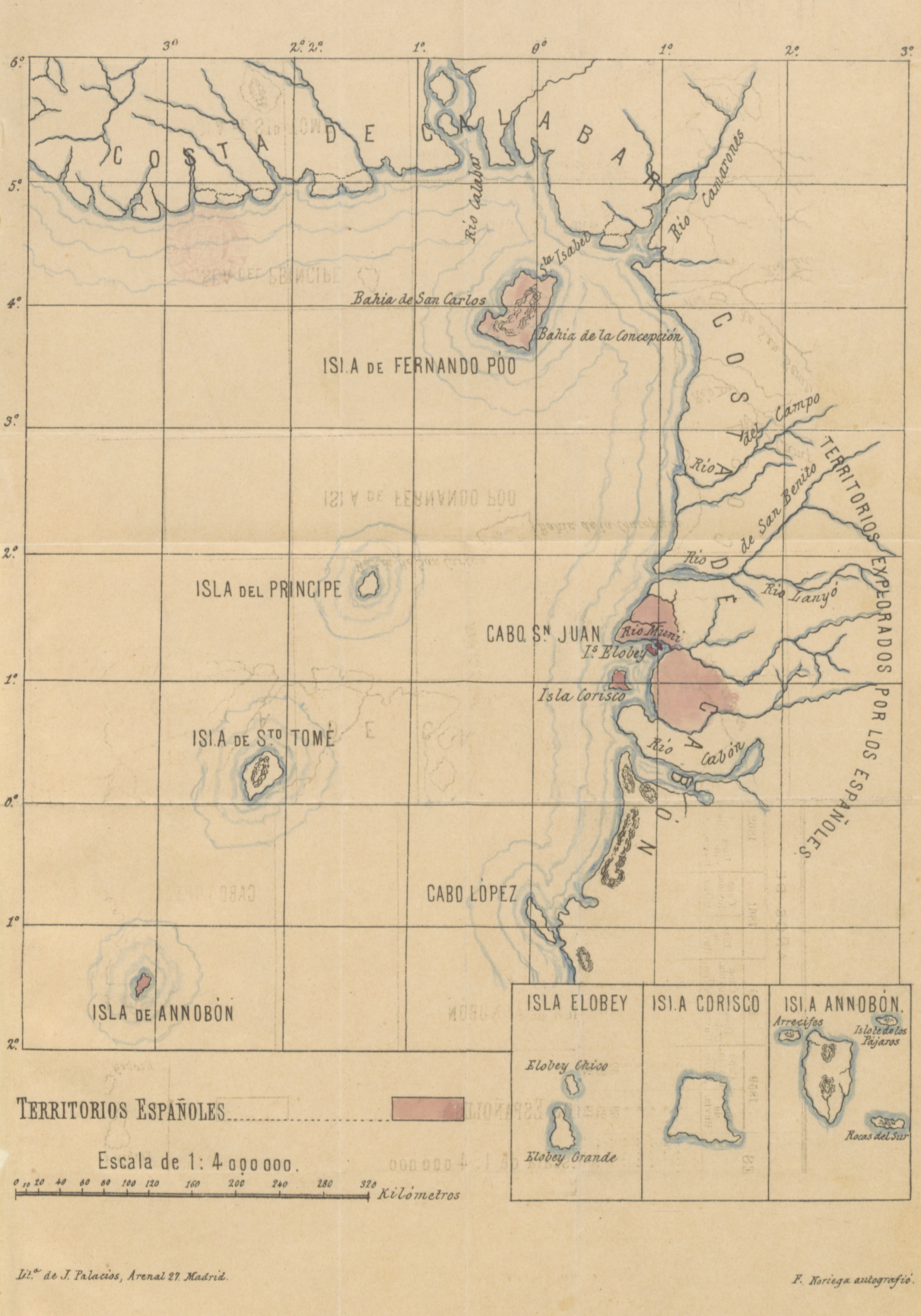

Equatorial Guinea ( es, Guinea Ecuatorial; french: Guinée équatoriale; pt, Guiné Equatorial), officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea ( es, link=no, República de Guinea Ecuatorial, french: link=no, République de Guinée équatoriale, pt, link=no, República da Guiné Equatorial),

*french: link=no, République de Guinée équatoriale

* pt, link=no, República da Guiné Equatorial is a country on the west coast of

Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, ...

, with an area of . Formerly the colony of Spanish Guinea

Spanish Guinea (Spanish: ''Guinea Española'') was a set of insular and continental territories controlled by Spain from 1778 in the Gulf of Guinea and on the Bight of Bonny, in Central Africa. It gained independence in 1968 as Equatorial G ...

, its post-independence name evokes its location near both the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

and the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is in the ...

. , the country had a population of 1,468,777.

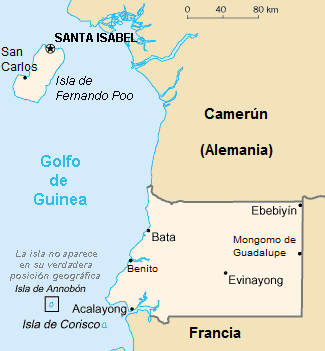

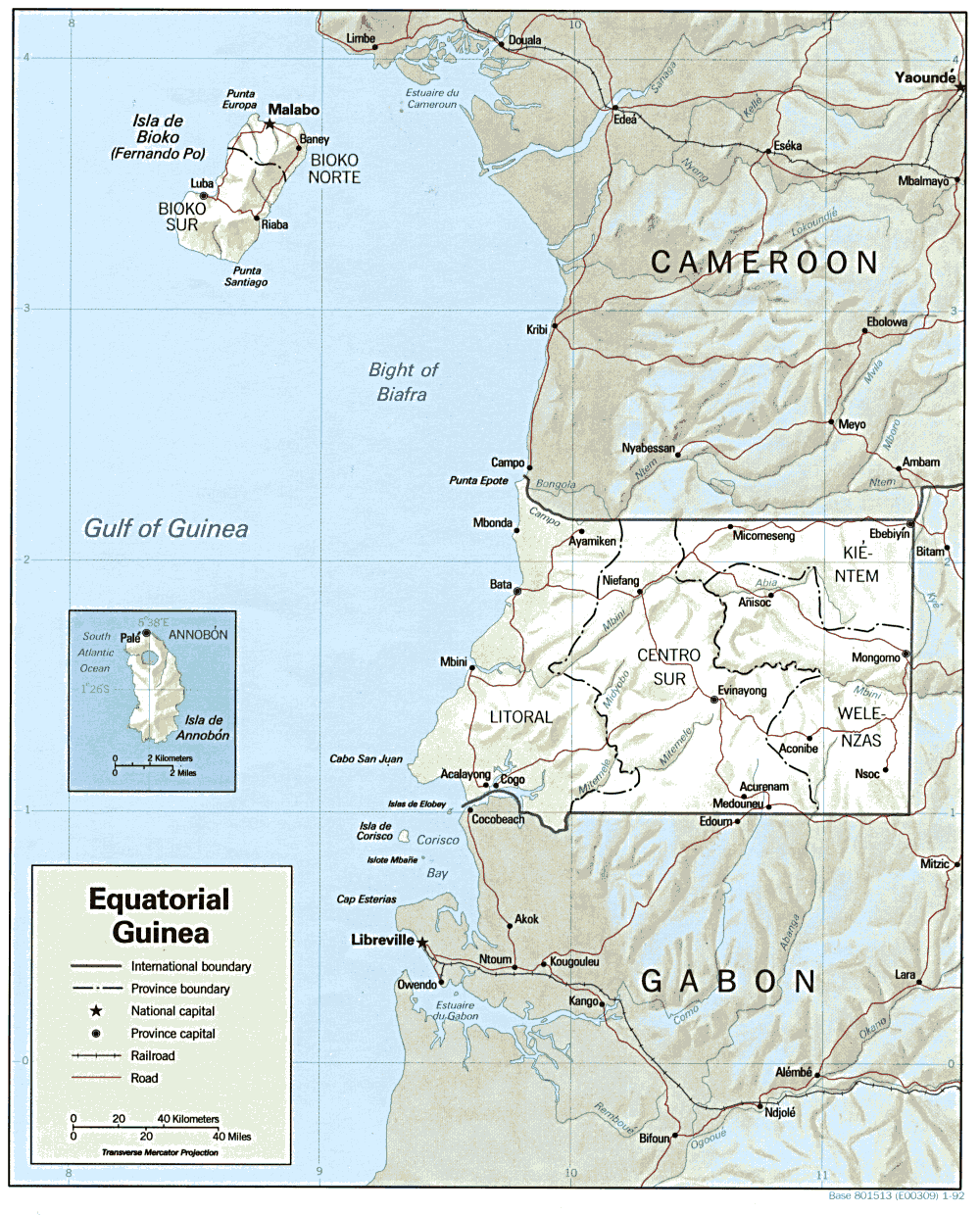

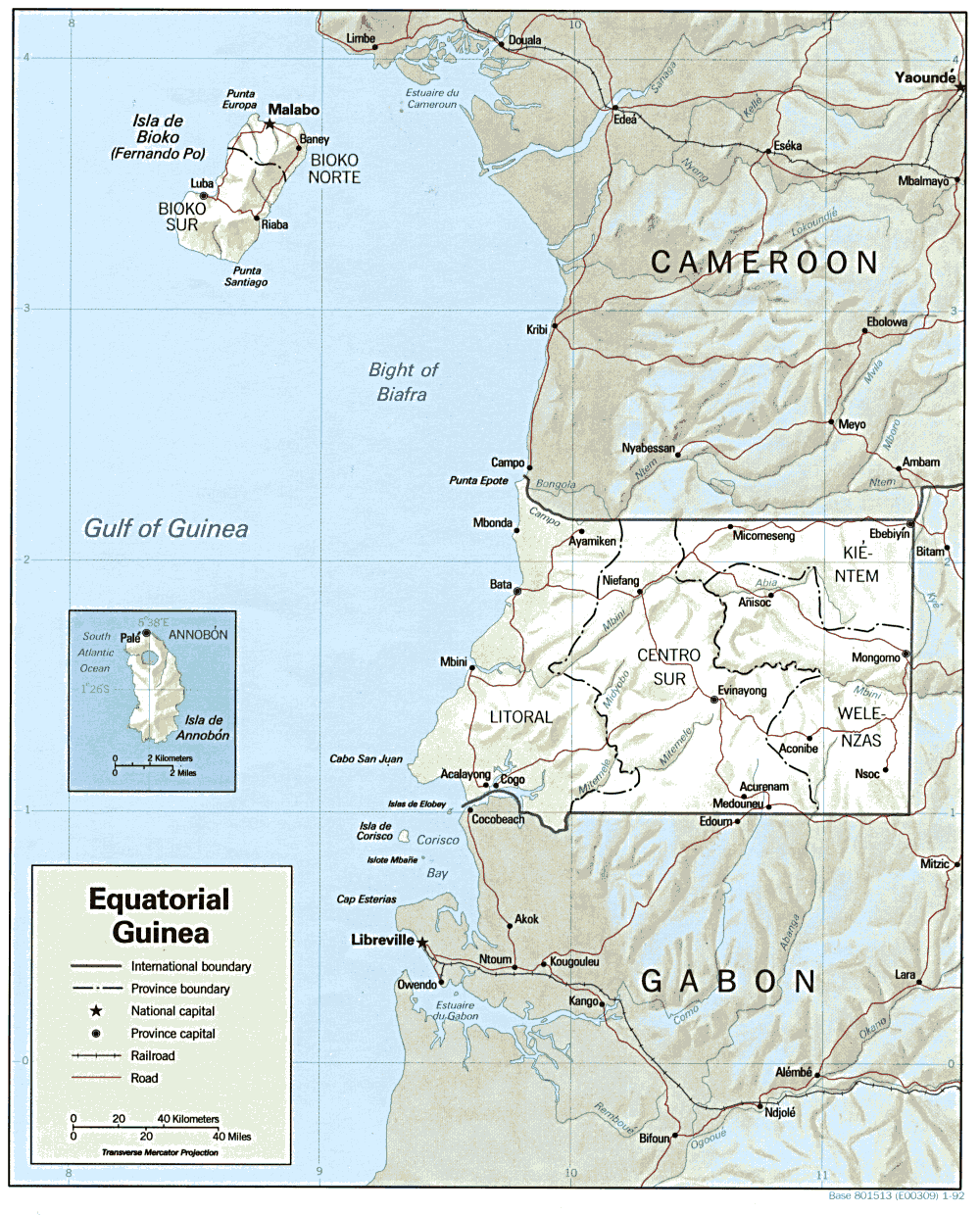

Equatorial Guinea consists of two parts, an insular and a mainland region. The insular region consists of the islands of Bioko

Bioko (; historically Fernando Po; bvb, Ëtulá Ëria) is an island off the west coast of Africa and the northernmost part of Equatorial Guinea. Its population was 335,048 at the 2015 census and it covers an area of . The island is located of ...

(formerly ''Fernando Pó'') in the Gulf of Guinea and Annobón

Annobón ( es, Provincia de Annobón; pt, Ano-Bom), and formerly as ''Anno Bom'' and ''Annabona'', is a province (smallest province in both area and population) of Equatorial Guinea consisting of the island of Annobón, formerly also Pigalu a ...

, a small volcanic island which is the only part of the country south of the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

. Bioko Island is the northernmost part of Equatorial Guinea and is the site of the country's capital, Malabo

Malabo ( , ; formerly Santa Isabel) is the capital of Equatorial Guinea and the province of Bioko Norte. It is located on the north coast of the island of Bioko, ( bvb, Etulá, and as ''Fernando Pó'' by the Europeans). In 2018, the city had a p ...

. The Portuguese-speaking island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe (; pt, São Tomé e Príncipe (); English: " Saint Thomas and Prince"), officially the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe ( pt, República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe), is a Portuguese-speaking i ...

is located between Bioko and Annobón. The mainland region, Río Muni

Río Muni (called ''Mbini'' in Fang) is the Continental Region (called ''Región Continental'' in Spanish) of Equatorial Guinea, and comprises the mainland geographical region, covering . The name is derived from the Muni River, along which ...

, is bordered by Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

on the north and Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

on the south and east. It is the location of Bata, Equatorial Guinea's largest city, and Ciudad de la Paz

Djibloho - Ciudad de la Paz (french: Djibloho - Ville de Paix, pt, Djibloho - Cidade da Paz), formerly Oyala, is a city in Equatorial Guinea that is being built to replace Malabo as the national capital. Established as an urban district in Wele- ...

, the country's planned future capital. Rio Muni also includes several small offshore islands, such as Corisco

Corisco, Mandj, or Mandyi, is a small island of Equatorial Guinea, located southwest of the Río Muni estuary that defines the border with Gabon. Corisco, whose name derives from the Portuguese word for lightning, has an area of , and its highe ...

, Elobey Grande

Elobey Grande, or Great Elobey, is an island of Equatorial Guinea, lying at the mouth of the Mitémélé River. It is sparsely inhabited. Elobey Chico is a smaller island offshore, now uninhabited but once the colonial capital of the Río Muni. ...

, and Elobey Chico

Elobey Chico, or Little Elobey, is a small island off the coast of Equatorial Guinea, lying near the mouth of the Mitémélé River. The island is now uninhabited but was once the ''de facto'' colonial capital of the Spanish territory of Río M ...

. The country is a member of the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the Africa ...

, Francophonie

Francophonie is the quality of speaking French. The term designates the ensemble of people, organisations and governments that share the use of French on a daily basis and as administrative language, teaching language or chosen language. The ...

, OPEC

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

and the CPLP

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries (Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa''; abbreviated as the CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth (''Comunidade Lusófona''), is an international ...

.

After becoming independent from Spain in 1968, Equatorial Guinea was ruled by President for life Francisco Macías Nguema

Francisco Macías Nguema ( Africanised to Masie Nguema Biyogo Ñegue Ndong; 1 January 1924 – 29 September 1979), often mononymously referred to as Macías, was an Equatoguinean politician who served as the first President of Equatorial Guinea f ...

until he was overthrown in a coup in 1979 by his nephew Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (; born 5 June 1942) is an Equatoguinean politician and former military officer who has served as the second president of Equatorial Guinea since August 1979. He is the longest-serving president of any country eve ...

who has served as the country's president since. Both presidents have been widely characterized as dictators by foreign observers. Since the mid-1990s, Equatorial Guinea has become one of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

's largest oil producers. It has subsequently become the richest country per capita in Africa, and its gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a money, monetary Measurement in economics, measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjec ...

(GDP) adjusted for purchasing power parity

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is the measurement of prices in different countries that uses the prices of specific goods to compare the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currency, currencies. PPP is effectively the ratio of the price of ...

(PPP) per capita ranks 43rd in the world; however, the wealth is distributed extremely unevenly, with few people benefiting from the oil riches. The country ranks 144th on the 2019 Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

, with less than half the population having access to clean drinking water and 7.9% of children dying before the age of five.

As a former Spanish colony, the country maintains Spanish as its official language alongside French and recently (as of 2010) Portuguese, being the only African country (aside from the largely unrecognized Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (; SADR; also romanized with Saharawi; ar, الجمهورية العربية الصحراوية الديمقراطية ' es, República Árabe Saharaui Democrática), also known as Western Sahara, is a p ...

) where Spanish is an official language. It is also the most widely spoken language (considerably more than the other two official languages); according to the Instituto Cervantes

Instituto Cervantes (the Cervantes Institute) is a worldwide nonprofit organization created by the government of Spain, Spanish government in 1991. It is named after Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), the author of ''Don Quixote'' and perhaps the ...

, 87.7% of the population has a good command of Spanish.

Equatorial Guinea's government is authoritarian and has one of the worst human rights records in the world, consistently ranking among the "worst of the worst" in Freedom House

Freedom House is a non-profit, majority U.S. government funded organization in Washington, D.C., that conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights. Freedom House was founded in October 1941, and Wendell Wil ...

's annual survey of political and civil rights. Reporters Without Borders

Reporters Without Borders (RWB; french: Reporters sans frontières; RSF) is an international non-profit and non-governmental organization with the stated aim of safeguarding the right to freedom of information. It describes its advocacy as found ...

ranks President Obiang among its "predators" of press freedom. Human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extrac ...

is a significant problem, with the U.S. Trafficking in Persons Report identifying Equatorial Guinea as a source and destination country for forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

and sex trafficking. The report also noted that Equatorial Guinea "does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking but is making significant efforts to do so."

History

Pygmies

In anthropology, pygmy peoples are ethnic groups whose average height is unusually short. The term pygmyism is used to describe the phenotype of endemic short stature (as opposed to disproportionate dwarfism occurring in isolated cases in a pop ...

probably once lived in the continental region that is now Equatorial Guinea, but are today found only in isolated pockets in southern Río Muni. Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for National ...

migrations started probably around 2,000 BC from between south-east Nigeria and north-west Cameroon (the Grassfields). They must have settled continental Equatorial Guinea around 500 BC at the latest. The earliest settlements on Bioko Island are dated to AD 530. The Annobón

Annobón ( es, Provincia de Annobón; pt, Ano-Bom), and formerly as ''Anno Bom'' and ''Annabona'', is a province (smallest province in both area and population) of Equatorial Guinea consisting of the island of Annobón, formerly also Pigalu a ...

population, originally native to Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, was introduced by the Portuguese via São Tomé island

São Tomé Island, at , is the largest island of São Tomé and Príncipe and is home in May 2018 to about 193,380 or 96% of the nation's population. The island is divided into six districts. It is located 2 km (1¼ miles) north of the ...

.

First European contact and Portuguese rule (1472–1778)

ThePortuguese explorer

Portuguese maritime exploration resulted in the numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of Eu ...

Fernando Pó, seeking a path to India, is credited as being the first European to see the island of Bioko, in 1472. He called it ''Formosa'' ("Beautiful"), but it quickly took on the name of its European discoverer. Fernando Pó and Annobón were colonized by Portugal in 1474. The first factories were established on the islands around 1500 as the Portuguese quickly recognized the positives of the islands including volcanic soil and disease-resistant highlands. Despite natural advantages, initial Portuguese efforts in 1507 to establish a sugarcane plantation and town near what is now Concepción on Fernando Pó failed due to Bubi hostility and fever. The main island's rainy climate, extreme humidity and temperature swings took a major toll on European settlers from the beginning, and it would be centuries before attempts restarted.

Early Spanish rule and lease to Britain (1778–1844)

In 1778, QueenMaria I of Portugal

, succession = Queen of Portugal

, image = Maria I, Queen of Portugal - Giuseppe Troni, atribuído (Turim, 1739-Lisboa, 1810) - Google Cultural Institute.jpg

, caption = Portrait attributed to Giuseppe Troni,

, reign ...

and King Charles III of Spain

it, Carlo Sebastiano di Borbone e Farnese

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Elisabeth Farnese

, birth_date = 20 January 1716

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain

, death_d ...

signed the Treaty of El Pardo which ceded Bioko

Bioko (; historically Fernando Po; bvb, Ëtulá Ëria) is an island off the west coast of Africa and the northernmost part of Equatorial Guinea. Its population was 335,048 at the 2015 census and it covers an area of . The island is located of ...

, adjacent islets, and commercial rights to the Bight of Biafra

The Bight of Biafra (known as the Bight of Bonny in Nigeria) is a bight off the West African coast, in the easternmost part of the Gulf of Guinea.

Geography

The Bight of Biafra, or Mafra (named after the town Mafra in southern Portugal), between ...

between the Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesOgoue rivers to

In 1844, the British returned the island to Spanish control and the area became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea". Due to epidemics, Spain did not invest much in the colony, and in 1862 an outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the whites that had settled on the island. Despite this, plantations continued to be established by private citizens through the second half of the 19th century.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 13. Peter Lang, New York.

The

In 1844, the British returned the island to Spanish control and the area became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea". Due to epidemics, Spain did not invest much in the colony, and in 1862 an outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the whites that had settled on the island. Despite this, plantations continued to be established by private citizens through the second half of the 19th century.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 13. Peter Lang, New York.

The

Spain had not occupied the large area in the

Spain had not occupied the large area in the

"Spanish Equatorial Guinea, 1898–1940"

in ''The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1905 to 1940'' Ed. J. D. Fage, A. D. Roberts, & Roland Anthony Oliver. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press The tiny enclave was far smaller than what the Spaniards had considered themselves rightfully entitled to under their claims and the Treaty of El Pardo. The humiliation of the Franco-Spanish negotiations, combined with the disaster in Cuba led to the head of the Spanish negotiating team, The greatest constraint to

The greatest constraint to

Politically, post-war colonial history has three fairly distinct phases: up to 1959, when its status was raised from 'colonial' to 'provincial', following the approach of the

Politically, post-war colonial history has three fairly distinct phases: up to 1959, when its status was raised from 'colonial' to 'provincial', following the approach of the

Independence from Spain was gained on 12 October 1968, at noon in the capital, Malabo. The new country became the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (the date is celebrated as the country's

Independence from Spain was gained on 12 October 1968, at noon in the capital, Malabo. The new country became the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (the date is celebrated as the country's

The nephew of Macías Nguema,

The nephew of Macías Nguema,

The current president of Equatorial Guinea is Teodoro Obiang. The 1982 constitution of Equatorial Guinea gives him extensive powers, including naming and dismissing members of the cabinet, making laws by decree, dissolving the Chamber of Representatives, negotiating and ratifying treaties and serving as commander in chief of the armed forces. Prime Minister

The current president of Equatorial Guinea is Teodoro Obiang. The 1982 constitution of Equatorial Guinea gives him extensive powers, including naming and dismissing members of the cabinet, making laws by decree, dissolving the Chamber of Representatives, negotiating and ratifying treaties and serving as commander in chief of the armed forces. Prime Minister  During the four decades of his rule, Obiang has shown little tolerance for opposition. While the country is nominally a multiparty democracy, its elections have generally been considered a sham. According to

During the four decades of his rule, Obiang has shown little tolerance for opposition. While the country is nominally a multiparty democracy, its elections have generally been considered a sham. According to

Bbc.co.uk (11 December 2012). Retrieved on 5 May 2013. Since August 1979 some 12 real and perceived unsuccessful coup attempts have occurred. According to a March 2004 BBC profile, politics within the country were dominated by tensions between Obiang's son, In November 2011, a new constitution was approved. The vote on the constitution was taken though neither the text or its content was revealed to the public before the vote. Under the new constitution the president was limited to a maximum of two seven-year terms and would be both the head of state and head of the government, therefore eliminating the prime minister. The new constitution also introduced the figure of a vice president and called for the creation of a 70-member senate with 55 senators elected by the people and the 15 remaining designated by the president. Surprisingly, in the following cabinet reshuffle it was announced that there would be two vice-presidents in clear violation of the constitution that was just taking effect.

In October 2012, during an interview with

In November 2011, a new constitution was approved. The vote on the constitution was taken though neither the text or its content was revealed to the public before the vote. Under the new constitution the president was limited to a maximum of two seven-year terms and would be both the head of state and head of the government, therefore eliminating the prime minister. The new constitution also introduced the figure of a vice president and called for the creation of a 70-member senate with 55 senators elected by the people and the 15 remaining designated by the president. Surprisingly, in the following cabinet reshuffle it was announced that there would be two vice-presidents in clear violation of the constitution that was just taking effect.

In October 2012, during an interview with

The

The

Equatorial Guinea has a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. From June to August, Río Muni is dry and Bioko wet; from December to February, the reverse occurs. In between there is gradual transition. Rain or mist occurs daily on Annobón, where a cloudless day has never been registered. The temperature at Malabo, Bioko, ranges from to , though on the southern Moka Plateau normal high temperatures are only . In Río Muni, the average temperature is about . Annual

Equatorial Guinea has a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. From June to August, Río Muni is dry and Bioko wet; from December to February, the reverse occurs. In between there is gradual transition. Rain or mist occurs daily on Annobón, where a cloudless day has never been registered. The temperature at Malabo, Bioko, ranges from to , though on the southern Moka Plateau normal high temperatures are only . In Río Muni, the average temperature is about . Annual

File:Annobon Island Equatorial Guinea.jpg, Annobon

File:Islotes Horacio 1.JPG, Islote Horacio

File:Dschungel bei Oyala.JPG, Near

File:Dissotis sp Bioko201310.jpg,

Before independence Equatorial Guinea exported

Before independence Equatorial Guinea exported  The discovery of large

The discovery of large  According to the

According to the

Due to the large oil industry in the country, internationally recognized carriers fly to

Due to the large oil industry in the country, internationally recognized carriers fly to

The majority of the people of Equatorial Guinea are of

The majority of the people of Equatorial Guinea are of  A growing number of foreigners from neighboring

A growing number of foreigners from neighboring

Since its independence in 1968, Equatorial Guinea main official language is Spanish (the local variant is

Since its independence in 1968, Equatorial Guinea main official language is Spanish (the local variant is

''Terra''. 13 July 2007 French was only made official in order to join the

Guineaecuatorialpress.com. Retrieved on 5 May 2013. Fa d'Ambô, a Portuguese creole, has vigorous use in

Fa d'Ambô, a Portuguese creole, has vigorous use in

The principal religion in Equatorial Guinea is Christianity, the faith of 93% of the population.

The principal religion in Equatorial Guinea is Christianity, the faith of 93% of the population.

In June 1984, the First Hispanic-African Cultural Congress was convened to explore the cultural identity of Equatorial Guinea. The congress constituted the center of integration and the marriage of the Hispanic culture with African cultures.

In June 1984, the First Hispanic-African Cultural Congress was convened to explore the cultural identity of Equatorial Guinea. The congress constituted the center of integration and the marriage of the Hispanic culture with African cultures.

Equatorial Guinea currently has no

Equatorial Guinea currently has no

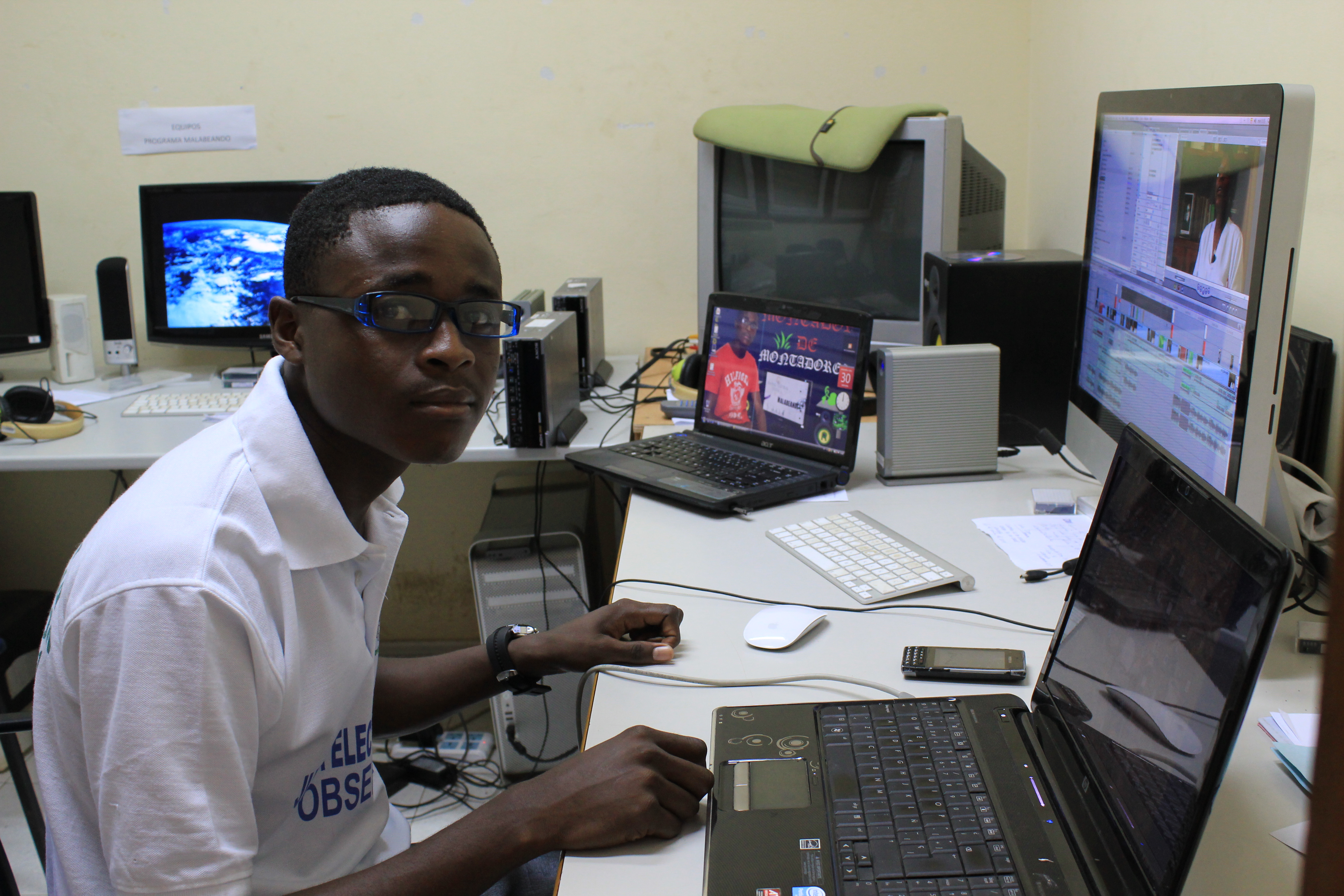

The principal means of communication within Equatorial Guinea are 3 state-operated

The principal means of communication within Equatorial Guinea are 3 state-operated

Equatorial Guinea was chosen to co-host the

Equatorial Guinea was chosen to co-host the

Official Government of Equatorial Guinea website

Guinea in Figures – Official Web Page of the Government of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea

Country Profile

from

Equatorial Guinea

''

Equatorial Guinea

from ''UCB Libraries GovPubs''. {{Authority control Central African countries Former Portuguese colonies Former Spanish colonies French-speaking countries and territories Member states of OPEC Member states of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie Member states of the African Union Member states of the United Nations Republics Spanish-speaking countries and territories States and territories established in 1968 Member states of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries 1968 establishments in Africa Portuguese-speaking countries and territories Countries in Africa Former least developed countries

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in exchange for large areas in South America that are now Western Brazil. Brigadier Felipe José, Count of Arjelejos sailed from Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

to formally take possession of Bioko from Portugal, landing on the island on 21 October 1778. After sailing for Annobón to take possession, the Count died of disease caught on Bioko and the fever-ridden crew mutinied. The crew landed on São Tomé instead where they were imprisoned by the Portuguese authorities after having lost over 80% of their men to sickness. As a result of this disaster, Spain was thereafter hesitant to invest heavily in its new possession. However, despite the setback Spaniards began to use the island as a base for slave trading on the nearby mainland. Between 1778 and 1810, the territory of what became Equatorial Guinea was administered by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata ( es, Virreinato del Río de la Plata or es, Virreinato de las Provincias del Río de la Plata) meaning "River of the Silver", also called "Viceroyalty of the River Plate" in some scholarly writings, in ...

, based in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 6-7. Peter Lang, New York.

Unwilling to invest heavily in the development of Fernando Pó, from 1827 to 1843, the Spanish leased a base at Malabo on Bioko

Bioko (; historically Fernando Po; bvb, Ëtulá Ëria) is an island off the west coast of Africa and the northernmost part of Equatorial Guinea. Its population was 335,048 at the 2015 census and it covers an area of . The island is located of ...

to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

which the UK had sought as part of its efforts to suppress the transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

. Without Spanish permission, the British moved the headquarters of the Mixed Commission for the Suppression of Slave Traffic to Fernando Pó in 1827, before moving it back to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

under an agreement with Spain in 1843. Spain's decision to abolish slavery in 1817 at British insistence damaged the colony's perceived value to the authorities and so leasing naval bases was an effective revenue earner from an otherwise unprofitable possession. An agreement by Spain to sell its African colony to the British was cancelled in 1841 due to metropolitan public opinion and opposition by Spanish Congress.

Late 19th century (1844–1900)

In 1844, the British returned the island to Spanish control and the area became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea". Due to epidemics, Spain did not invest much in the colony, and in 1862 an outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the whites that had settled on the island. Despite this, plantations continued to be established by private citizens through the second half of the 19th century.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 13. Peter Lang, New York.

The

In 1844, the British returned the island to Spanish control and the area became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea". Due to epidemics, Spain did not invest much in the colony, and in 1862 an outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the whites that had settled on the island. Despite this, plantations continued to be established by private citizens through the second half of the 19th century.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 13. Peter Lang, New York.

The plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

s of Fernando Pó were mostly run by a black Creole elite

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

, later known as Fernandinos

Fernandinos are creoles, multi-ethnic or multi-racial populations who developed in Equatorial Guinea (Spanish Guinea). Their name is derived from the island of Fernando Pó, where many worked. This island was named for the Portuguese explorer F ...

. The British settled some 2,000 Sierra Leoneans and freed slaves there during their rule, and a trickle of immigration from West Africa and the West Indies continued after the British left. A number of freed Angolan slaves, Portuguese-African creoles and immigrants from Nigeria and Liberia also began to be settled in the colony where they quickly began to join the new group.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 9. Peter Lang, New York. To the local mix were added Cubans, Filipinos, Jews and Spaniards of various colours, many of whom had been deported to Africa for political or other crimes, as well as some settlers backed by the government.

By 1870 the prognosis of whites that lived on the island was much improved after recommendations that they live in the highlands, and by 1884 much of the minimal administrative machinery and key plantations had moved to Basile hundreds of meters above sea level. Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of Central Africa

Cen ...

had labeled Fernando Pó "a jewel which Spain did not polish" for refusing to enact such a policy. Despite the improved survival chances of Europeans living on the island, Mary Kingsley

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (13 October 1862 – 3 June 1900) was an English ethnographer, scientific writer, and explorer whose travels throughout West Africa and resulting work helped shape European perceptions of both African cultures and ...

, who was staying on the island still described Fernando Pó as 'a more uncomfortable form of execution' for Spaniards appointed there.

There was also a trickle of immigration from the neighboring Portuguese islands, escaped slaves, and prospective planters. Although a few of the Fernandinos

Fernandinos are creoles, multi-ethnic or multi-racial populations who developed in Equatorial Guinea (Spanish Guinea). Their name is derived from the island of Fernando Pó, where many worked. This island was named for the Portuguese explorer F ...

were Catholic and Spanish-speaking, about nine-tenths of them were Protestant and English-speaking on the eve of the First World War, and pidgin English

Pidgin English is a non-specific name used to refer to any of the many pidgin languages derived from English. Pidgins that are spoken as first languages become creoles.

English-based pidgins that became stable contact languages, and which have ...

was the ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

'' of the island. The Sierra Leoneans were particularly well placed as planters while labor recruitment on the Windward coast

The Windward Coast was used to describe an area of West Africa located on the coast between Cape Mount and Assini, i.e. the coastlines of the modern states of Liberia and Ivory Coast, to the west of what was called the Gold Coast. A related re ...

continued, for they kept family and other connections there and could easily arrange a supply of labor. The Fernandinos proved to become effective traders and middlemen between the natives and Europeans. A freed slave from the West Indies by way of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

named William Pratt established the cocoa crop on Fernando Pó.

Early 20th century (1900–1945)

Bight of Biafra

The Bight of Biafra (known as the Bight of Bonny in Nigeria) is a bight off the West African coast, in the easternmost part of the Gulf of Guinea.

Geography

The Bight of Biafra, or Mafra (named after the town Mafra in southern Portugal), between ...

to which it had right by treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations

An international organization or international o ...

, and the French had busily expanded their occupation at the expense of the territory claimed by Spain. Madrid only partly backed the explorations of men like Manuel Iradier

Manuel Iradier (b. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Vitoria, 1854–1911) was a Spanish explorer of Africa. A student of philosophy and literature, he fell under the influence of Henry Morton Stanley and turned to exploration.

History

From 1868-1874 he made p ...

who had signed treaties in the interior as far as Gabon and Cameroon, leaving much of the land out of 'effective occupation' as demanded by the terms of the 1885 Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence ...

. More important events such as the conflict in Cuba and the eventual Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

kept Madrid busy at an inopportune moment. Minimal government backing for mainland annexation came as a result of public opinion and a need for labour on Fernando Pó.

The eventual treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

in 1900 left Spain with the continental enclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

of Rio Muni, a mere 26,000 km out of the 300,000 stretching east to the Ubangi river

The Ubangi River (), also spelled Oubangui, is the largest right-bank tributary of the Congo River in the region of Central Africa. It begins at the confluence of the Mbomou (mean annual discharge 1,350 m3/s) and Uele Rivers (mean annual discharge ...

which the Spaniards had initially claimed.Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (1986"Spanish Equatorial Guinea, 1898–1940"

in ''The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1905 to 1940'' Ed. J. D. Fage, A. D. Roberts, & Roland Anthony Oliver. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press The tiny enclave was far smaller than what the Spaniards had considered themselves rightfully entitled to under their claims and the Treaty of El Pardo. The humiliation of the Franco-Spanish negotiations, combined with the disaster in Cuba led to the head of the Spanish negotiating team,

Pedro Gover y Tovar

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for ''Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

committing suicide on the voyage home on 21 October 1901.Fegley, Randall (1989). ''Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy'', p. 19. Peter Lang, New York. Iradier himself died in despair in 1911, and it would be decades before his achievements would be recognised by Spanish popular opinion when the port of Cogo

CoGo Bike Share is a public bicycle sharing system serving Columbus, Ohio and its suburbs. The service is operated by the bikeshare company Motivate (part of Lyft, Inc.) It was created in July 2013 with 300 bikes and 30 docking stations, since ex ...

was renamed Puerto Iradier in his honour.

The opening years of the twentieth century saw a new generation of Spanish immigrants. Land regulations issued in 1904–1905 favoured Spaniards, and most of the later big planters arrived from Spain after that. An agreement made with Liberia in 1914 to import cheap labor greatly favoured wealthy men with ready access to the state, and the shift in labor supplies from Liberia to Río Muni increased this advantage. Due to malpractice however, the Liberian government eventually ended the treaty after embarrassing revelations about the state of Liberian workers on Fernando Pó in the Christy Report which brought down the country's president Charles D. B. King

Charles Dunbar Burgess King (12 March 1875 – 4 September 1961) was a Liberian politician who served as the 17th president of Liberia from 1920 to 1930. He was of Americo-Liberian and Sierra Leone Creole descent. He was a member of the True Whig ...

in 1930.

The greatest constraint to

The greatest constraint to economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and o ...

was a chronic shortage of labour. Pushed into the interior of the island and decimated by alcohol addiction, venereal disease, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, and sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis, also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals. It is caused by the species ''Trypanosoma brucei''. Humans are infected by two typ ...

, the indigenous Bubi

BuBi (officially: MOL BuBi) is a bicycle sharing network in Budapest, Hungary. Its name is a playful contraction Budapest and Bicikli ( bicycle in Hungarian), meaning "bubble" in an endearing manner. As of May 2019 the network consists of 143 doc ...

population of Bioko

Bioko (; historically Fernando Po; bvb, Ëtulá Ëria) is an island off the west coast of Africa and the northernmost part of Equatorial Guinea. Its population was 335,048 at the 2015 census and it covers an area of . The island is located of ...

refused to work on plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

s. Working their own small cocoa

Cocoa may refer to:

Chocolate

* Chocolate

* ''Theobroma cacao'', the cocoa tree

* Cocoa bean, seed of ''Theobroma cacao''

* Chocolate liquor, or cocoa liquor, pure, liquid chocolate extracted from the cocoa bean, including both cocoa butter and ...

farms gave them a considerable degree of autonomy.

By the late nineteenth century, the Bubi were protected from the demands of the planters by Spanish Claretian

, image = Herb CMF.jpg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = Coat of arms of the Claretians

, abbreviation = CMF

, nickname = Claretians

, formation =

, founders = Anto ...

missionaries, who were very influential in the colony and eventually organised the Bubi into little mission theocracies reminiscent of the famous Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

reductions

Reductions ( es, reducciones, also called ; , pl. ) were settlements created by Spanish rulers and Roman Catholic missionaries in Spanish America and the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines). In Portuguese-speaking Latin America, such redu ...

in Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

. Catholic penetration was furthered by two small insurrections in 1898 and 1910 protesting conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

for the plantations. The Bubi were disarmed in 1917, and left dependent on the missionaries. Serious labour shortages were temporarily solved by a massive influx of refugees from German Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern p ...

, along with thousands of white German soldiers who stayed on the island for several years.

Between 1926 and 1959 Bioko and Rio Muni were united as the colony of Spanish Guinea

Spanish Guinea (Spanish: ''Guinea Española'') was a set of insular and continental territories controlled by Spain from 1778 in the Gulf of Guinea and on the Bight of Bonny, in Central Africa. It gained independence in 1968 as Equatorial G ...

. The economy was based on large cacao

Cacao is the seed from which cocoa and chocolate are made, from Spanish cacao, an adaptation of Nahuatl cacaua, the root form of cacahuatl ("bean of the cocoa-tree"). It may also refer to:

Plants

*''Theobroma cacao'', a tropical evergreen tree

** ...

and coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulant, stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

S ...

plantations and logging

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks or skeleton cars.

Logging is the beginning of a supply chain ...

concessions and the workforce was mostly immigrant contract labour

Employment is a relationship between two party (law), parties Regulation, regulating the provision of paid Labour (human activity), labour services. Usually based on a employment contract, contract, one party, the employer, which might be a co ...

from Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, and Cameroun

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

. Between 1914 and 1930, an estimated 10,000 Liberians went to Fernando Po under a labour treaty that was stopped altogether in 1930.

With Liberian workers no longer available, planters of Fernando Po turned to Rio Muni. Campaigns were mounted to subdue the Fang people

__NOTOC__

The Fang people, also known as Fãn or Pahouin, are a Bantu ethnic group found in Equatorial Guinea, northern Gabon, and southern Cameroon.

in the 1920s, at the time that Liberia was beginning to cut back on recruitment. There were garrisons of the colonial guard throughout the enclave by 1926, and the whole colony was considered 'pacified' by 1929.

The Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

had a major impact on the colony. 150 Spanish whites, including the Governor-General and Vice-Governor-General of Río Muni created a socialist party called the Popular Front in the enclave which served to oppose the interests of the Fernando Pó plantation owners. When the War broke out Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

ordered Nationalist forces based in the Canaries to ensure control over Equatorial Guinea. In September 1936 Nationalist forces backed by Falangists from Fernando Pó, similarly to what happened in Spain proper took control of Río Muni, which under Governor-General Luiz Sanchez Guerra Saez and his deputy Porcel had backed the Republican government. By November the Popular Front and its supporters had been defeated and Equatorial Guinea secured for Franco. The commander in charge of the occupation, Juan Fontán Lobé was appointed Governor-General by Franco and began to exert more effective Spanish control over the enclave interior.

Rio Muni had a small population, officially a little over 100,000 in the 1930s, and escape across the frontiers into Cameroun

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

or Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

was very easy. Also, the timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

companies needed increasing numbers of workers, and the spread of coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulant, stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

S ...

cultivation offered an alternative means of paying taxes. Fernando Pó thus continued to suffer from labour shortages. The French only briefly permitted recruitment in Cameroun, and the main source of labour came to be Igbo

Igbo may refer to:

* Igbo people, an ethnic group of Nigeria

* Igbo language, their language

* anything related to Igboland, a cultural region in Nigeria

See also

* Ibo (disambiguation)

* Igbo mythology

* Igbo music

* Igbo art

*

* Igbo-Ukwu, a t ...

smuggled in canoes from Calabar

Calabar (also referred to as Callabar, Calabari, Calbari and Kalabar) is the capital city of Cross River State, Nigeria. It was originally named Akwa Akpa, in the Efik language. The city is adjacent to the Calabar and Great Kwa rivers and cre ...

in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

. This resolution to the worker shortage allowed Fernando Pó to become one of Africa's most productive agricultural areas after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Final years of Spanish rule (1945–1968)

Politically, post-war colonial history has three fairly distinct phases: up to 1959, when its status was raised from 'colonial' to 'provincial', following the approach of the

Politically, post-war colonial history has three fairly distinct phases: up to 1959, when its status was raised from 'colonial' to 'provincial', following the approach of the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

; between 1960 and 1968, when Madrid attempted a partial decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

aimed at keeping the territory as part of the Spanish system; and from 1968 on, after the territory became an independent republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

. The first phase consisted of little more than a continuation of previous policies; these closely resembled the policies of Portugal and France, notably in dividing the population into a vast majority governed as 'natives' or non-citizens, and a very small minority (together with whites) admitted to civic status as ''emancipados

Emancipado () was a term used for an African-descended social-political demographic within the population of Spanish Guinea (modern day Equatorial Guinea) that existed in the early to mid 1900s. This segment of the native population had become ass ...

'', assimilation to the metropolitan culture being the only permissible means of advancement.

This 'provincial' phase saw the beginnings of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, but chiefly among small groups who had taken refuge from the ''Caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; osp, cabdillo, from Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise definition of ''caudillo'', which is often used interchangeably with " ...

''s paternal hand in Cameroun and Gabon. They formed two bodies: the Movimiento Nacional de Liberación de la Guinea (MONALIGE), and the Idea Popular de Guinea Ecuatorial

The Popular Idea of Equatorial Guinea ( es, Idea Popular de Guinea Ecuatorial, IPGE) was a nationalist political group created at the end of the 1950s with the goal of establishing independence in Equatorial Guinea. The IPGE is considered to be ...

(IPGE). The pressure they could bring to bear was weak, but the general trend in West Africa was not, and by the late 1960s much of the African continent had been granted independence. Aware of this trend, the Spanish began to increase efforts to prepare the country for independence and massively stepped up development. The Gross National Product per capita in 1965 was $466 which was the highest in black Africa, and the Spanish constructed an international airport at Santa Isabel, a television station and increased the literacy rate to a relatively high 89%. At the same time measures were taken to battle sleeping sickness and leprosy in the enclave, and by 1967 the number of hospital beds per capita in Equatorial Guinea was higher than Spain itself, with 1637 beds in 16 hospitals. All the same, measures to improve education floundered and like in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

by the end of colonial rule the number of Africans in higher education was in only the double digits, and political education necessary to a functioning state was negligible.

A decision of 9 August 1963, approved by a referendum of 15 December 1963, gave the territory a measure of autonomy and the administrative promotion of a 'moderate' group, the (MUNGE). This proved a feeble instrument, and, with growing pressure for change from the UN, Madrid was gradually forced to give way to the currents of nationalism. Two General Assembly resolutions were passed in 1965 ordering Spain to grant independence to the colony, and in 1966 a UN Commission toured the country before recommending the same thing. In response, the Spanish declared that they would hold a constitutional convention on 27 October 1967 to negotiate a new constitution for an independent Equatorial Guinea. The conference was attended by 41 local delegates and 25 Spaniards. The Africans were principally divided between Fernandinos and Bubi on one side, who feared a loss of privileges and 'swamping' by the Fang majority, and the Río Muni Fang nationalists on the other. At the conference the leading Fang figure, the later first president Francisco Macías Nguema

Francisco Macías Nguema ( Africanised to Masie Nguema Biyogo Ñegue Ndong; 1 January 1924 – 29 September 1979), often mononymously referred to as Macías, was an Equatoguinean politician who served as the first President of Equatorial Guinea f ...

gave a controversial speech in which he claimed that Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had 'saved Africa'. After nine sessions the conference was suspended due to deadlock between the 'unionists' and 'separatists' who wanted a separate Fernando Pó. Macías resolved to travel to the UN to bolster international awareness of the issue, and his firebrand speeches in New York contributed to Spain naming a date for both independence and general elections. In July 1968 virtually all Bubi leaders went to the UN in New York to try and raise awareness for their cause, but the world community was uninterested in quibbling over the specifics of colonial independence. The 1960s were a time of great optimism over the future of the former African colonies, and groups that had been close to European rulers, like the Bubi, were not viewed positively.

Independence under Macías (1968–1979)

Independence from Spain was gained on 12 October 1968, at noon in the capital, Malabo. The new country became the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (the date is celebrated as the country's

Independence from Spain was gained on 12 October 1968, at noon in the capital, Malabo. The new country became the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (the date is celebrated as the country's Independence Day

An independence day is an annual event commemorating the anniversary of a nation's independence or statehood, usually after ceasing to be a group or part of another nation or state, or more rarely after the end of a military occupation. Man ...

). Macías became president in the country's only free and fair election. The Spanish (ruled by Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

) had backed Macías in the election due to his perceived loyalty, however while on the campaign trail he had proven to be far less easy to handle than they had expected. Much of his campaigning involved visiting rural areas of Río Muni and promising young Fang that they would have the houses and wives of the Spanish if they voted for him. In the towns he had instead presented himself as the urbane leader who had bested the Spanish at the UN, and he had won in the second round of voting; greatly helped by the vote-splitting of his rivals.

The euphoria of independence became quickly overshadowed by problems emanating from the Nigerian Civil War

The Nigerian Civil War (6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970), also known as the Nigerian–Biafran War or the Biafran War, was a civil war fought between Nigeria and the Republic of Biafra, a secessionist state which had declared its independence f ...

. Fernando Pó was inhabited by many Biafra-supporting Ibo migrant workers and many refugees from the breakaway state fled to the island, straining it to breaking point. The International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

began running relief flights out of Equatorial Guinea, but Macías quickly became spooked and shut the flights down, refusing to allow them to fly diesel fuel for their trucks nor oxygen tanks for medical operations. Very quickly the Biafran separatists were starved into submission without international backing.

After the Public Prosecutor complained about "excesses and maltreatment" by government officials, Macías had 150 alleged coup-plotters executed in a purge on Christmas Eve 1969, all of whom happened to be political opponents. Macias Nguema further consolidated his totalitarian powers by outlawing opposition political parties in July 1970 and making himself president for life in 1972. He broke off ties with Spain and the West. In spite of his condemnation of Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, which he deemed " neo-colonialist", Equatorial Guinea maintained very special relations with communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

s, notably China, Cuba, and the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. Macias Nguema signed a preferential trade agreement

A trade agreement (also known as trade pact) is a wide-ranging taxes, tariff and trade treaty that often includes investment guarantees. It exists when two or more countries agree on terms that help them trade with each other. The most common tr ...

and a shipping treaty with the Soviet Union. The Soviets also made loans to Equatorial Guinea.

The shipping agreement gave the Soviets permission for a pilot fishery

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, both ...

development project and also a naval base at Luba

Luba may refer to:

Geography

*Kingdom of Luba, a pre-colonial Central African empire

*Ľubá, a village and municipality in the Nitra region of south-west Slovakia

*Luba, Abra, a municipality in the Philippines

*Luba, Equatorial Guinea, a town o ...

. In return the USSR was to supply fish to Equatorial Guinea. China and Cuba also gave different forms of financial, military, and technical assistance to Equatorial Guinea, which got them a measure of influence there. For the USSR, there was an advantage to be gained in the War in Angola from access to Luba base and later on to Malabo International Airport

Malabo Airport or Saint Isabel Airport ( es, link=no, Aeropuerto de Malabo), is an airport located at ''Punta Europa'', Bioko, Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. The airport is named after the capital, Malabo, approximately to the east.

Airline ...

.

In 1974, the World Council of Churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) is a worldwide Christian inter-church organization founded in 1948 to work for the cause of ecumenism. Its full members today include the Assyrian Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, most juri ...

affirmed that large numbers of people had been murdered since 1968 in an ongoing reign of terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to revolutionary fervour, ...

. A quarter of the entire population had fled abroad, they said, while 'the prisons are overflowing and to all intents and purposes form one vast concentration camp'. Out of a population of 300,000, an estimated 80,000 were killed. Apart from allegedly committing genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

against the ethnic minority Bubi people

The Bubi people (also known as Bobe, Voove, Ewota and Bantu Bubi) are a Bantu ethnic group of Central Africa who are indigenous to Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Once the majority group in the region, the population experienced a sharp decline ...

, Macias Nguema ordered the deaths of thousands of suspected opponents, closed down churches and presided over the economy's collapse as skilled citizens and foreigners fled the country.

Obiang (1979–present)

The nephew of Macías Nguema,

The nephew of Macías Nguema, Teodoro Obiang

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (; born 5 June 1942) is an Equatoguinean politician and former military officer who has served as the second president of Equatorial Guinea since August 1979. He is the longest-serving president of any country eve ...

deposed his uncle on 3 August 1979, in a bloody ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

''; over two weeks of civil war ensued until Macías Nguema was captured. He was tried and executed soon afterward, with Obiang succeeding him as a less bloody, but still authoritarian president.

In 1995 Mobil

Mobil is a petroleum brand owned and operated by American oil and gas corporation ExxonMobil. The brand was formerly owned and operated by an oil and gas corporation of the same name, which itself merged with Exxon to form ExxonMobil in 1999.

...

, an American oil company, discovered oil in Equatorial Guinea. The country subsequently experienced rapid economic development, but earnings from the country's oil wealth have not reached the population and the country ranks low on the UN human development index. 7.9% of children die before the age of 5 and more than 50% of the population lacks access to clean drinking water

Drinking water is water that is used in drink or food preparation; potable water is water that is safe to be used as drinking water. The amount of drinking water required to maintain good health varies, and depends on physical activity level, a ...

. President Teodoro Obiang is widely suspected of using the country's oil wealth to enrich himself and his associates. In 2006, Forbes estimated his personal wealth at $600 million.

In 2011, the government announced it was planning a new capital for the country, named Oyala

Djibloho - Ciudad de la Paz (french: Djibloho - Ville de Paix, pt, Djibloho - Cidade da Paz), formerly Oyala, is a city in Equatorial Guinea that is being built to replace Malabo as the national capital. Established as an urban district in Wele- ...

. The city was renamed Ciudad de la Paz

Djibloho - Ciudad de la Paz (french: Djibloho - Ville de Paix, pt, Djibloho - Cidade da Paz), formerly Oyala, is a city in Equatorial Guinea that is being built to replace Malabo as the national capital. Established as an urban district in Wele- ...

(''"City of Peace"'') in 2017.

, Obiang is Africa's second-longest serving dictator after Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

's Paul Biya

Paul Biya (born Paul Barthélemy Biya'a bi Mvondo; 13 February 1933) is a Cameroonian politician who has served as the president of Cameroon since 6 November 1982.

.

On 7 March 2021, there were munition explosions at a military base near the city of Bata causing 98 deaths and 600 people being injured and treated at the hospital.

In November 2022 Obiang was re-elected in the 2022 Equatorial Guinean general election

General elections were held in Equatorial Guinea on 20 November 2022 to elect the President and members of Parliament, alongside local elections. Originally the parliamentary elections had been scheduled for November 2022 and presidential electi ...

with 99.7% of the vote amid accusations of fraud by the opposition.

Government and politics

The current president of Equatorial Guinea is Teodoro Obiang. The 1982 constitution of Equatorial Guinea gives him extensive powers, including naming and dismissing members of the cabinet, making laws by decree, dissolving the Chamber of Representatives, negotiating and ratifying treaties and serving as commander in chief of the armed forces. Prime Minister

The current president of Equatorial Guinea is Teodoro Obiang. The 1982 constitution of Equatorial Guinea gives him extensive powers, including naming and dismissing members of the cabinet, making laws by decree, dissolving the Chamber of Representatives, negotiating and ratifying treaties and serving as commander in chief of the armed forces. Prime Minister Francisco Pascual Obama Asue

Francisco Pascual Eyegue Obama Asue is an Equatoguinean

Equatorial Guinea ( es, Guinea Ecuatorial; french: Guinée équatoriale; pt, Guiné Equatorial), officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea ( es, link=no, República de Guinea Ecu ...

was appointed by Obiang and operates under powers delegated by the President.

During the four decades of his rule, Obiang has shown little tolerance for opposition. While the country is nominally a multiparty democracy, its elections have generally been considered a sham. According to

During the four decades of his rule, Obiang has shown little tolerance for opposition. While the country is nominally a multiparty democracy, its elections have generally been considered a sham. According to Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human r ...

, the dictatorship of President Obiang used an oil boom

An oil boom is a period of large inflow of income as a result of high global oil prices or large oil production in an economy. Generally, this short period initially brings economic benefits, in terms of increased GDP growth, but might later lead ...

to entrench and enrich itself further at the expense of the country's people.BBC News – Equatorial Guinea country profile – OverviewBbc.co.uk (11 December 2012). Retrieved on 5 May 2013. Since August 1979 some 12 real and perceived unsuccessful coup attempts have occurred. According to a March 2004 BBC profile, politics within the country were dominated by tensions between Obiang's son,

Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue

Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (born 25 June 1968, nicknamed Teodorín) is the Vice President of Equatorial Guinea, in office since 2016. He is a son of Teodoro Obiang, the authoritarian leader of Equatorial Guinea, by his first wife, Constancia Ma ...

, and other close relatives with powerful positions in the security forces. The tension may be rooted in a power shift arising from the dramatic increase in oil production which has occurred since 1997.

In 2004 a plane load of suspected mercenaries was intercepted in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

while allegedly on the way to overthrow Obiang. A November 2004 report named Mark Thatcher

Sir Mark Thatcher, 2nd Baronet (born 15 August 1953) is an English businessman. He is the son of Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990, and Sir Denis Thatcher; his sister is Carol Thatcher.

His early career ...

as a financial backer of the 2004 Equatorial Guinea coup d'état attempt

The 2004 Equatorial Guinea coup d'état attempt, also known as the Wonga Coup, failed to replace President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo with exiled opposition politician Severo Moto. Mercenaries organised by mainly British financiers were arre ...

organized by Simon Mann

Simon Francis Mann (born 26 June 1952) is a British mercenary and former officer in the SAS. He trained to be an officer at Sandhurst and was commissioned into the Scots Guards. He later became a member of the SAS. On leaving the military, h ...

. Various accounts also named the United Kingdom's MI6

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

, the United States' CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

, and Spain as tacit supporters of the coup attempt. Nevertheless, the Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

report released in June 2005

on the ensuing trial of those allegedly involved highlighted the prosecution's failure to produce conclusive evidence that a coup attempt had actually taken place. Simon Mann was released from prison on 3 November 2009 for humanitarian reasons.

Since 2005, Military Professional Resources Inc.

L-3 MPRI, was a global provider of private military contractor services with customers that included U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, law enforcement agencies, ...

, a US-based international private military company

A private military company (PMC) or private military and security company (PMSC) is a private company providing armed combat or security services for financial gain. PMCs refer to their personnel as "security contractors" or "private military ...

, has worked in Equatorial Guinea to train police forces in appropriate human rights practices. In 2006, US Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

Condoleezza Rice

Condoleezza Rice ( ; born November 14, 1954) is an American diplomat and political scientist who is the current director of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. A member of the Republican Party, she previously served as the 66th Uni ...

hailed Obiang as a "good friend" despite repeated criticism of his human rights and civil liberties record. The US Agency for International Development

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 bi ...

entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Obiang, in April 2006, to establish a social development Fund in the country, implementing projects in the areas of health, education, women's affairs and the environment.

In 2006, Obiang signed an anti-torture decree banning all forms of abuse and improper treatment in Equatorial Guinea, and commissioned the renovation and modernization of Black Beach prison in 2007 to ensure the humane treatment of prisoners. However, human rights abuses have continued. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International among other non-governmental organizations have documented severe human rights abuses in prisons, including torture, beatings, unexplained deaths and illegal detention.

In their most recently publishing findings (2020), Transparency International

Transparency International e.V. (TI) is a German registered association founded in 1993 by former employees of the World Bank. Based in Berlin, its nonprofit and non-governmental purpose is to take action to combat global corruption with civil ...

awarded Equatorial Guinea a total score of 16 on their Corruption Perceptions Index

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is an index which ranks countries "by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys." The CPI generally defines corruption as an "abuse of entru ...