Epikouros Met 11 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Epicurus (; grc-gre,

Epicurus's teachings were heavily influenced by those of earlier philosophers, particularly Democritus. Nonetheless, Epicurus differed from his predecessors on several key points of determinism and vehemently denied having been influenced by any previous philosophers, whom he denounced as "confused". Instead, he insisted that he had been "self-taught". According to DeWitt, Epicurus's teachings also show influences from the contemporary philosophical school of

Epicurus's teachings were heavily influenced by those of earlier philosophers, particularly Democritus. Nonetheless, Epicurus differed from his predecessors on several key points of determinism and vehemently denied having been influenced by any previous philosophers, whom he denounced as "confused". Instead, he insisted that he had been "self-taught". According to DeWitt, Epicurus's teachings also show influences from the contemporary philosophical school of

During Epicurus's lifetime, Platonism was the dominant philosophy in higher education. Epicurus's opposition to Platonism formed a large part of his thought. Over half of the forty Principal Doctrines of Epicureanism are flat contradictions of Platonism. In around 311 BC, Epicurus, when he was around thirty years old, began teaching in Mytilene. Around this time, Zeno of Citium, the founder of

During Epicurus's lifetime, Platonism was the dominant philosophy in higher education. Epicurus's opposition to Platonism formed a large part of his thought. Over half of the forty Principal Doctrines of Epicureanism are flat contradictions of Platonism. In around 311 BC, Epicurus, when he was around thirty years old, began teaching in Mytilene. Around this time, Zeno of Citium, the founder of

Epicurus was a hedonist, meaning he taught that what is pleasurable is morally good and what is painful is morally evil. He idiosyncratically defined "pleasure" as the absence of suffering and taught that all humans should seek to attain the state of ''

Epicurus was a hedonist, meaning he taught that what is pleasurable is morally good and what is painful is morally evil. He idiosyncratically defined "pleasure" as the absence of suffering and taught that all humans should seek to attain the state of ''

In his ''Letter to Menoeceus'', a summary of his own moral and theological teachings, the first piece of advice Epicurus himself gives to his student is: "First, believe that a god is an indestructible and blessed animal, in accordance with the general conception of god commonly held, and do not ascribe to god anything foreign to his indestructibility or repugnant to his blessedness." Epicurus maintained that he and his followers knew that the gods exist because "our knowledge of them is a matter of clear and distinct perception", meaning that people can empirically sense their presences. He did not mean that people can see the gods as physical objects, but rather that they can see visions of the gods sent from the remote regions of interstellar space in which they actually reside. According to George K. Strodach, Epicurus could have easily dispensed of the gods entirely without greatly altering his materialist worldview, but the gods still play one important function in Epicurus's theology as the paragons of moral virtue to be emulated and admired.

Epicurus rejected the conventional Greek view of the gods as anthropomorphic beings who walked the earth like ordinary people, fathered illegitimate offspring with mortals, and pursued personal feuds. Instead, he taught that the gods are morally perfect, but detached and immobile beings who live in the remote regions of interstellar space. In line with these teachings, Epicurus adamantly rejected the idea that deities were involved in human affairs in any way. Epicurus maintained that the gods are so utterly perfect and removed from the world that they are incapable of listening to prayers or supplications or doing virtually anything aside from contemplating their own perfections. In his ''Letter to Herodotus'', he specifically denies that the gods have any control over natural phenomena, arguing that this would contradict their fundamental nature, which is perfect, because any kind of worldly involvement would tarnish their perfection. He further warned that believing that the gods control natural phenomena would only mislead people into believing the superstitious view that the gods punish humans for wrongdoing, which only instills fear and prevents people from attaining ''ataraxia''.

Epicurus himself criticizes popular religion in both his ''Letter to Menoeceus'' and his ''Letter to Herodotus'', but in a restrained and moderate tone. Later Epicureans mainly followed the same ideas as Epicurus, believing in the existence of the gods, but emphatically rejecting the idea of divine providence. Their criticisms of popular religion, however, are often less gentle than those of Epicurus himself. The ''Letter to Pythocles'', written by a later Epicurean, is dismissive and contemptuous towards popular religion and Epicurus's devoted follower, the Roman poet

In his ''Letter to Menoeceus'', a summary of his own moral and theological teachings, the first piece of advice Epicurus himself gives to his student is: "First, believe that a god is an indestructible and blessed animal, in accordance with the general conception of god commonly held, and do not ascribe to god anything foreign to his indestructibility or repugnant to his blessedness." Epicurus maintained that he and his followers knew that the gods exist because "our knowledge of them is a matter of clear and distinct perception", meaning that people can empirically sense their presences. He did not mean that people can see the gods as physical objects, but rather that they can see visions of the gods sent from the remote regions of interstellar space in which they actually reside. According to George K. Strodach, Epicurus could have easily dispensed of the gods entirely without greatly altering his materialist worldview, but the gods still play one important function in Epicurus's theology as the paragons of moral virtue to be emulated and admired.

Epicurus rejected the conventional Greek view of the gods as anthropomorphic beings who walked the earth like ordinary people, fathered illegitimate offspring with mortals, and pursued personal feuds. Instead, he taught that the gods are morally perfect, but detached and immobile beings who live in the remote regions of interstellar space. In line with these teachings, Epicurus adamantly rejected the idea that deities were involved in human affairs in any way. Epicurus maintained that the gods are so utterly perfect and removed from the world that they are incapable of listening to prayers or supplications or doing virtually anything aside from contemplating their own perfections. In his ''Letter to Herodotus'', he specifically denies that the gods have any control over natural phenomena, arguing that this would contradict their fundamental nature, which is perfect, because any kind of worldly involvement would tarnish their perfection. He further warned that believing that the gods control natural phenomena would only mislead people into believing the superstitious view that the gods punish humans for wrongdoing, which only instills fear and prevents people from attaining ''ataraxia''.

Epicurus himself criticizes popular religion in both his ''Letter to Menoeceus'' and his ''Letter to Herodotus'', but in a restrained and moderate tone. Later Epicureans mainly followed the same ideas as Epicurus, believing in the existence of the gods, but emphatically rejecting the idea of divine providence. Their criticisms of popular religion, however, are often less gentle than those of Epicurus himself. The ''Letter to Pythocles'', written by a later Epicurean, is dismissive and contemptuous towards popular religion and Epicurus's devoted follower, the Roman poet

The Epicurean paradox or riddle of Epicurus or Epicurus' trilemma is a version of the

The Epicurean paradox or riddle of Epicurus or Epicurus' trilemma is a version of the

Epicurus was an extremely prolific writer. According to Diogenes LaГ«rtius, he wrote around 300 treatises on a variety of subjects. More original writings of Epicurus have survived to the present day than of any other Hellenistic Greek philosopher. Nonetheless, the vast majority of everything he wrote has now been lost and most of what is known about Epicurus's teachings come from the writings of his later followers, particularly the Roman poet Lucretius. The only surviving complete works by Epicurus are three relatively lengthy letters, which are quoted in their entirety in Book X of

Epicurus was an extremely prolific writer. According to Diogenes LaГ«rtius, he wrote around 300 treatises on a variety of subjects. More original writings of Epicurus have survived to the present day than of any other Hellenistic Greek philosopher. Nonetheless, the vast majority of everything he wrote has now been lost and most of what is known about Epicurus's teachings come from the writings of his later followers, particularly the Roman poet Lucretius. The only surviving complete works by Epicurus are three relatively lengthy letters, which are quoted in their entirety in Book X of

By the early fifth century AD, Epicureanism was virtually extinct. The Christian Church Father

By the early fifth century AD, Epicureanism was virtually extinct. The Christian Church Father

In 1417, a manuscript-hunter named

In 1417, a manuscript-hunter named

In the seventeenth century, the French Catholic priest and scholar

In the seventeenth century, the French Catholic priest and scholar

''Epicureanism''

SPCK (1880)

''Stoic And Epicurean''

by

Epicurea, Hermann Usener - full text

* * .

Society of Friends of Epicurus

Discussion Forum for Epicurus and Epicurean philosophy - EpicureanFriends.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:Epicurus 4th-century BC Greek people 4th-century BC philosophers 4th-century BC writers 3rd-century BC Greek people 3rd-century BC philosophers 3rd-century BC writers 341 BC births 270 BC deaths Ancient Greek epistemologists Ancient Greek ethicists Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek philosophers of mind Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Samians Ancient Greek cosmologists Critics of religions Cultural critics Empiricists Epicurean philosophers Epistemologists Greek male writers Hellenistic-era philosophers Materialists Metaphysicians Moral philosophers Ontologists Philosophers of education Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of mind Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Religious skeptics Simple living advocates Social philosophers Virtue ethicists 4th-century BC religious leaders 3rd-century BC religious leaders Philosophers of death

бјҳПҖОҜОәОҝП…ПҒОҝПӮ

Epicurus (; grc-gre, бјҳПҖОҜОәОҝП…ПҒОҝПӮ ; 341вҖ“270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced ...

; 341вҖ“270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage

Sage or SAGE may refer to:

Plants

* ''Salvia officinalis'', common sage, a small evergreen subshrub used as a culinary herb

** Lamiaceae, a family of flowering plants commonly known as the mint or deadnettle or sage family

** ''Salvia'', a large ...

who founded Epicureanism

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

, a highly influential school of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

. He was born on the Greek island of Samos

Samos (, also ; el, ОЈО¬ОјОҝПӮ ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

to Athenian

Athens ( ; el, О‘ОёО®ОҪОұ, AthГӯna ; grc, бјҲОёбҝҶОҪОұО№, AthГӘnai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

parents. Influenced by Democritus

Democritus (; el, О”О·ОјПҢОәПҒО№П„ОҝПӮ, ''DД“mГіkritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; вҖ“ ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, Aristippus

Aristippus of Cyrene, Libya, Cyrene (; grc, бјҲПҒОҜПғП„О№ПҖПҖОҝПӮ бҪҒ ОҡП…ПҒО·ОҪОұбҝ–ОҝПӮ; c. 435 вҖ“ c. 356 BCE) was a Hedonism, hedonistic Ancient Greece, Greek philosopher and the founder of the Cyrenaics, Cyrenaic school of philosophy. He w ...

, Pyrrho

Pyrrho of Elis (; grc, О ПҚПҒПҒПүОҪ бҪҒ бјЁО»Оөбҝ–ОҝПӮ, PyrrhРҫМ„n ho Д’leios; ), born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Life

...

, and possibly the Cynics, he turned against the Platonism of his day and established his own school, known as "the Garden", in Athens. Epicurus and his followers were known for eating simple meals and discussing a wide range of philosophical subjects. He openly allowed women and slaves to join the school as a matter of policy. Of the over 300 works said to have been written by Epicurus about various subjects, the vast majority have been destroyed. Only three letters written by himвҖ”the letters to ''Menoeceus

In Greek mythology, Menoeceus (; Ancient Greek: ОңОөОҪОҝО№ОәОөПҚПӮ ''MenoikeГәs'' "strength of the house" derived from ''menos'' "strength" and ''oikos'' "house") was the name of two Theban characters. They are related by genealogy, the first being ...

'', ''Pythocles'', and ''Herodotus''вҖ”and two collections of quotesвҖ”the ''Principal Doctrines'' and the ''Vatican Sayings''вҖ”have survived intact, along with a few fragments of his other writings. As a result of his work's destruction, most knowledge about his philosophy is due to later authors, particularly the biographer Diogenes LaГ«rtius

Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

, the Epicurean Roman poet Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; вҖ“ ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

and the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus

Philodemus of Gadara ( grc-gre, ОҰО№О»ПҢОҙО·ОјОҝПӮ бҪҒ О“ОұОҙОұПҒОөПҚПӮ, ''PhilodД“mos'', "love of the people"; c. 110 вҖ“ prob. c. 40 or 35 BC) was an Arabic Epicurean philosopher and poet. He studied under Zeno of Sidon in Athens, before moving ...

, and with hostile but largely accurate accounts by the Pyrrhonist

Pyrrho of Elis (; grc, О ПҚПҒПҒПүОҪ бҪҒ бјЁО»Оөбҝ–ОҝПӮ, PyrrhРҫМ„n ho Д’leios; ), born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Life

...

philosopher Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, ОЈОӯОҫП„ОҝПӮ бјҳОјПҖОөО№ПҒО№ОәПҢПӮ, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

, and the Academic Skeptic and statesman Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вҖ“ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

.

Epicurus asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain happy ('' eudaimonic''), tranquil lives characterized by ''ataraxia

''Ataraxia'' (Greek: бјҖП„ОұПҒОұОҫОҜОұ, from ("a-", negation) and ''tarachД“'' "disturbance, trouble"; hence, "unperturbedness", generally translated as "imperturbability", "equanimity", or "tranquility") is a Greek term first used in Ancient Gre ...

'' (peace and freedom from fear) and ''aponia

"Aponia" ( grc, бјҖПҖОҝОҪОҜОұ) means the absence of pain, and was regarded by the Epicureans to be the height of bodily pleasure.

As with the other Hellenistic schools of philosophy, the Epicureans believed that the goal of human life is happine ...

'' (the absence of pain). He advocated that people were best able to pursue philosophy by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends. He taught that the root of all human neurosis is death denial and the tendency for human beings to assume that death will be horrific and painful, which he claimed causes unnecessary anxiety, selfish self-protective behaviors, and hypocrisy. According to Epicurus, death is the end of both the body and the soul and therefore should not be feared. Epicurus taught that although the gods exist, they have no involvement in human affairs. He taught that people should act ethically not because the gods punish or reward them for their actions but because, due to the power of guilt, amoral behavior would inevitably lead to remorse weighing on their consciences and as a result, they would be prevented from attaining ''ataraxia''.

Epicurus was an empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

, meaning he believed that only the senses are a reliable source of knowledge about the world. He derived much of his physics and cosmology from the earlier philosopher Democritus ( 460вҖ“ 370 BC). Like Democritus, Epicurus taught that the universe is infinite and eternal and that all matter is made up of extremely tiny, invisible particles known as ''atoms

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, an ...

''. All occurrences in the natural world are ultimately the result of atoms moving and interacting in empty space. Epicurus deviated from Democritus by proposing the idea of atomic "swerve", which holds that atoms may deviate from their expected course, thus permitting humans to possess free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actio ...

in an otherwise deterministic

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

universe.

Though popular, Epicurean teachings were controversial from the beginning. Epicureanism reached the height of its popularity during the late years of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

. It died out in late antiquity, subject to hostility from early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

. Throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

Epicurus was popularly, though inaccurately, remembered as a patron of drunkards, whoremongers, and gluttons. His teachings gradually became more widely known in the fifteenth century with the rediscovery of important texts, but his ideas did not become acceptable until the seventeenth century, when the French Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi

Pierre Gassendi (; also Pierre Gassend, Petrus Gassendi; 22 January 1592 вҖ“ 24 October 1655) was a French philosopher, Catholic priest, astronomer, and mathematician. While he held a church position in south-east France, he also spent much tim ...

revived a modified version of them, which was promoted by other writers, including Walter Charleton

Walter Charleton (2 February 1619 вҖ“ 24 April 1707) was a natural philosopher and English writer.

According to Jon Parkin, he was "the main conduit for the transmission of Epicurean ideas to England".Jon Parkin, ''Science, Religion and Politics ...

and Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

. His influence grew considerably during and after the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, profoundly impacting the ideas of major thinkers, including John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 вҖ“ 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 вҖ“ July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

, and Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 вҖ“ 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

.

Life

Upbringing and influences

Epicurus was born in the Athenian settlement on the Aegean island ofSamos

Samos (, also ; el, ОЈО¬ОјОҝПӮ ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

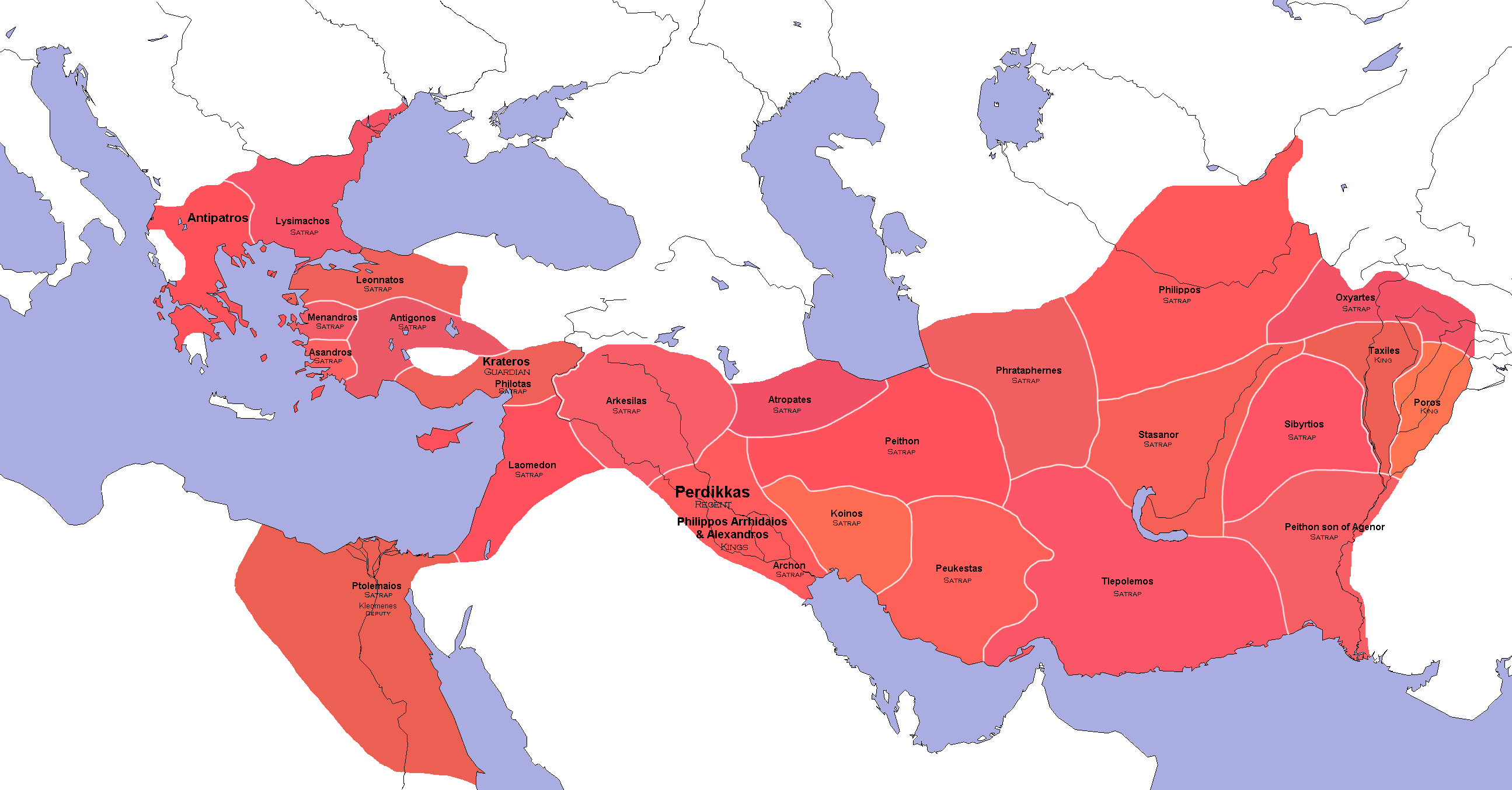

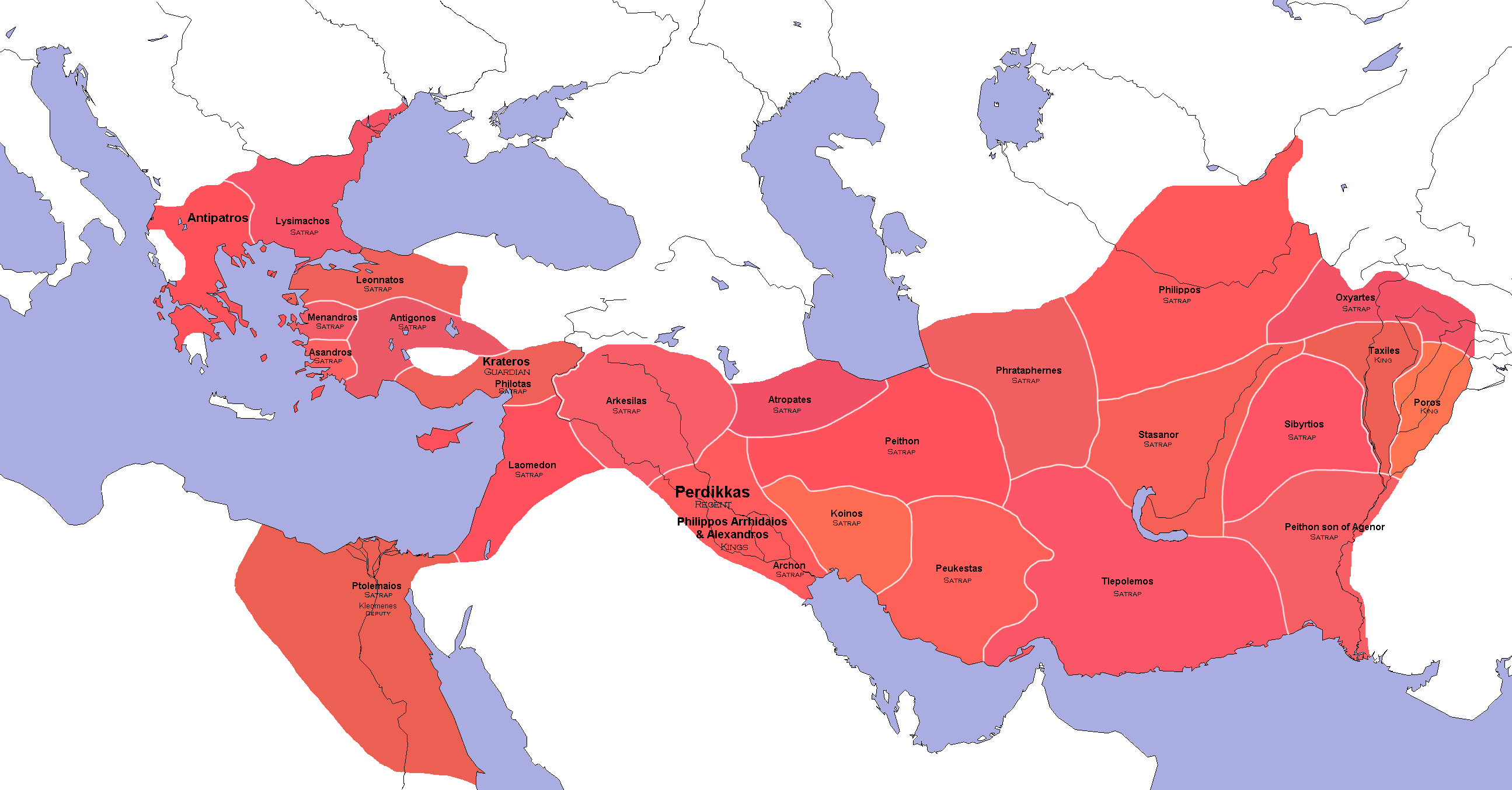

in February 341 BC. His parents, Neocles and Chaerestrate, were both Athenian-born, and his father was an Athenian citizen. Epicurus grew up during the final years of the Greek Classical Period. Plato had died seven years before Epicurus was born and Epicurus was seven years old when Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:бјҲО»ОӯОҫОұОҪОҙПҒОҝПӮ, бјҲО»ОӯОҫОұОҪОҙПҒОҝПӮ, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC вҖ“ 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

crossed the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, ГҮanakkale BoДҹazДұ, lit=Strait of ГҮanakkale, el, О”ОұПҒОҙОұОҪОӯО»О»О№Оұ, translit=DardanГ©llia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

into Persia. As a child, Epicurus would have received a typical ancient Greek education. As such, according to Norman Wentworth DeWitt, "it is inconceivable that he would have escaped the Platonic training in geometry, dialectic, and rhetoric." Epicurus is known to have studied under the instruction of a Samian Platonist named Pamphilus, probably for about four years. His ''Letter of Menoeceus'' and surviving fragments of his other writings strongly suggest that he had extensive training in rhetoric. After the death of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:бјҲО»ОӯОҫОұОҪОҙПҒОҝПӮ, бјҲО»ОӯОҫОұОҪОҙПҒОҝПӮ, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC вҖ“ 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, О ОөПҒОҙОҜОәОәОұПӮ, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to becom ...

expelled the Athenian settlers on Samos to Colophon, on the coast of what is now Turkey. After the completion of his military service, Epicurus joined his family there. He studied under Nausiphanes, who followed the teachings of Democritus

Democritus (; el, О”О·ОјПҢОәПҒО№П„ОҝПӮ, ''DД“mГіkritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; вҖ“ ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, and later those of Pyrrho

Pyrrho of Elis (; grc, О ПҚПҒПҒПүОҪ бҪҒ бјЁО»Оөбҝ–ОҝПӮ, PyrrhРҫМ„n ho Д’leios; ), born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Life

...

, whose way of life Epicurus greatly admired.

Epicurus's teachings were heavily influenced by those of earlier philosophers, particularly Democritus. Nonetheless, Epicurus differed from his predecessors on several key points of determinism and vehemently denied having been influenced by any previous philosophers, whom he denounced as "confused". Instead, he insisted that he had been "self-taught". According to DeWitt, Epicurus's teachings also show influences from the contemporary philosophical school of

Epicurus's teachings were heavily influenced by those of earlier philosophers, particularly Democritus. Nonetheless, Epicurus differed from his predecessors on several key points of determinism and vehemently denied having been influenced by any previous philosophers, whom he denounced as "confused". Instead, he insisted that he had been "self-taught". According to DeWitt, Epicurus's teachings also show influences from the contemporary philosophical school of Cynicism

Cynic or Cynicism may refer to:

Modes of thought

* Cynicism (philosophy), a school of ancient Greek philosophy

* Cynicism (contemporary), modern use of the word for distrust of others' motives

Books

* ''The Cynic'', James Gordon Stuart Grant 1 ...

. The Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope was still alive when Epicurus would have been in Athens for his required military training and it is possible they may have met. Diogenes's pupil Crates of Thebes ( 365 вҖ“ 285 BC) was a close contemporary of Epicurus. Epicurus agreed with the Cynics' quest for honesty, but rejected their "insolence and vulgarity", instead teaching that honesty must be coupled with courtesy and kindness. Epicurus shared this view with his contemporary, the comic playwright Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, ОңОӯОҪОұОҪОҙПҒОҝПӮ ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 вҖ“ c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

.

Epicurus's ''Letter to Menoeceus'', possibly an early work of his, is written in an eloquent style similar to that of the Athenian rhetorician Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, бјёПғОҝОәПҒО¬П„О·ПӮ ; 436вҖ“338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education throu ...

(436вҖ“338 BC), but, for his later works, he seems to have adopted the bald, intellectual style of the mathematician Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Wikt:О•бҪҗОәО»ОөОҜОҙО·ПӮ, О•бҪҗОәО»ОөОҜОҙО·ПӮ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'' trea ...

. Epicurus's epistemology also bears an unacknowledged debt to the later writings of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, бјҲПҒО№ПғП„ОҝП„ОӯО»О·ПӮ ''AristotГ©lД“s'', ; 384вҖ“322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

(384вҖ“322 BC), who rejected the Platonic idea of hypostatic Reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

and instead relied on nature and empirical evidence for knowledge about the universe. During Epicurus's formative years, Greek knowledge about the rest of the world was rapidly expanding due to the Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

of the Near East and the rise of Hellenistic kingdoms

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, О”О№О¬ОҙОҝПҮОҝО№, DiГЎdochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

. Epicurus's philosophy was consequently more universal in its outlook than those of his predecessors, since it took cognizance of non-Greek peoples as well as Greeks. He may have had access to the now-lost writings of the historian and ethnographer Megasthenes, who wrote during the reign of Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, ОЈОӯО»ОөП…ОәОҝПӮ ОқО№ОәО¬П„ПүПҒ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

(ruled 305вҖ“281 BC).

Teaching career

During Epicurus's lifetime, Platonism was the dominant philosophy in higher education. Epicurus's opposition to Platonism formed a large part of his thought. Over half of the forty Principal Doctrines of Epicureanism are flat contradictions of Platonism. In around 311 BC, Epicurus, when he was around thirty years old, began teaching in Mytilene. Around this time, Zeno of Citium, the founder of

During Epicurus's lifetime, Platonism was the dominant philosophy in higher education. Epicurus's opposition to Platonism formed a large part of his thought. Over half of the forty Principal Doctrines of Epicureanism are flat contradictions of Platonism. In around 311 BC, Epicurus, when he was around thirty years old, began teaching in Mytilene. Around this time, Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

, arrived in Athens, at the age of about twenty-one, but Zeno did not begin teaching what would become Stoicism for another twenty years. Although later texts, such as the writings of the first-century BC Roman orator Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вҖ“ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, portray Epicureanism and Stoicism as rivals, this rivalry seems to have only emerged after Epicurus's death.

Epicurus's teachings caused strife in Mytilene and he was forced to leave. He then founded a school in Lampsacus before returning to Athens in 306 BC, where he remained until his death. There he founded The Garden (ОәбҝҶПҖОҝПӮ), a school named for the garden he owned that served as the school's meeting place, about halfway between the locations of two other schools of philosophy, the Stoa

A stoa (; plural, stoas,"stoa", ''Oxford English Dictionary'', 2nd Ed., 1989 stoai, or stoae ), in ancient Greek architecture, is a covered walkway or portico, commonly for public use. Early stoas were open at the entrance with columns, usually ...

and the Academy. The Garden was more than just a school; it was "a community of like-minded and aspiring practitioners of a particular way of life." The primary members were Hermarchus, the financier Idomeneus, Leonteus and his wife Themista, the satirist Colotes Colotes of Lampsacus ( el, ОҡОҝО»ПҺП„О·ПӮ ОӣОұОјПҲОұОәО·ОҪПҢПӮ, ''KolЕҚtД“s LampsakД“nos''; c. 320 вҖ“ after 268 BC) was a pupil of Epicurus, and one of the most famous of his disciples. He wrote a work to prove "That it is impossible even to live a ...

, the mathematician Polyaenus of Lampsacus Polyaenus of Lampsacus ( ; grc-gre, О oО»ПҚОұО№ОҪoПӮ ОӣОұОјПҲОұОәО·ОҪПҢПӮ, ''Polyainos LampsakД“nos''; c. 340 вҖ“ c. 285 BCE), also spelled Polyenus, was an ancient Greek mathematician and a friend of Epicurus.

Life

He was the son of Athenodorus. ...

, and Metrodorus of Lampsacus, the most famous popularizer of Epicureanism. His school was the first of the ancient Greek philosophical schools to admit women as a rule rather than an exception, and the biography of Epicurus by Diogenes LaГ«rtius lists female students such as Leontion

Leontion ( la, Leontium, el, ОӣОөПҢОҪП„О№ОҝОҪ; fl. 300 BC) was a Greek Epicurean philosopher.

Biography

Leontion was a pupil of Epicurus and his philosophy. She was the companion of Metrodorus of Lampsacus. The information we have about her ...

and Nikidion. An inscription on the gate to The Garden is recorded by Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

in epistle XXI of '' Epistulae morales ad Lucilium'': "Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good

''Summum bonum'' is a Latin expression meaning the highest or ultimate good, which was introduced by the Roman philosopher Cicero to denote the fundamental principle on which some system of ethics is based вҖ” that is, the aim of actions, which, ...

is pleasure."

According to Diskin Clay, Epicurus himself established a custom of celebrating his birthday annually with common meals, befitting his stature as ''heros ktistes'' ("founding hero") of the Garden. He ordained in his will annual memorial feasts for himself on the same date (10th of Gamelion month). Epicurean communities continued this tradition, referring to Epicurus as their "saviour" ( soter) and celebrating him as hero. The hero cult of Epicurus may have operated as a Garden variety civic religion

Civil religion, also referred to as a civic religion, is the implicit religious values of a nation, as expressed through public rituals, symbols (such as the national flag), and ceremonies on sacred days and at sacred places (such as monuments, bat ...

. However, clear evidence of an Epicurean hero cult, as well as the cult itself, seems buried by the weight of posthumous philosophical interpretation. Epicurus never married and had no known children. He was most likely a vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism m ...

.

Death

Diogenes LaГ«rtius records that, according to Epicurus's successor Hermarchus, Epicurus died a slow and painful death in 270 BC at the age of seventy-two from a stone blockage of his urinary tract. Despite being in immense pain, Epicurus is said to have remained cheerful and to have continued to teach until the very end. Possible insights into Epicurus's death may be offered by the extremely brief ''Epistle to Idomeneus'', included by Diogenes LaГ«rtius in Book X of his ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

''. The authenticity of this letter is uncertain and it may be a later pro-Epicurean forgery intended to paint an admirable portrait of the philosopher to counter the large number of forged epistles in Epicurus's name portraying him unfavorably.

I have written this letter to you on a happy day to me, which is also the last day of my life. For I have been attacked by a painful inability to urinate, and also dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which comes from the recollection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions. And I beg you to take care of the children of Metrodorus, in a manner worthy of the devotion shown by the young man to me, and to philosophy.If authentic, this letter would support the tradition that Epicurus was able to remain joyful to the end, even in the midst of his suffering. It would also indicate that he maintained a special concern for the wellbeing of children.Diogenes LaГ«rtius Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ..., ''Lives of Eminent Philosophers''

10.22

(trans. C.D. Yonge).

Teachings

Epistemology

Epicurus and his followers had a well-developedepistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

, which developed as a result of their rivalry with other philosophical schools. Epicurus wrote a treatise entitled , or ''Rule'', in which he explained his methods of investigation and theory of knowledge. This book, however, has not survived, nor does any other text that fully and clearly explains Epicurean epistemology, leaving only mentions of this epistemology by several authors to reconstruct it. Epicurus was an ardent Empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

; believing that the senses are the only reliable sources of information about the world. He rejected the Platonic idea of "Reason" as a reliable source of knowledge about the world apart from the senses and was bitterly opposed to the Pyrrhonists

Pyrrho of Elis (; grc, О ПҚПҒПҒПүОҪ бҪҒ бјЁО»Оөбҝ–ОҝПӮ, PyrrhРҫМ„n ho Д’leios; ), born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek Philosophical skepticism, skeptic philosopher and found ...

and Academic Skeptics, who not only questioned the ability of the senses to provide accurate knowledge about the world, but also whether it is even possible to know anything about the world at all.

Epicurus maintained that the senses never deceive humans, but that the senses can be misinterpreted. Epicurus held that the purpose of all knowledge is to aid humans in attaining ''ataraxia''. He taught that knowledge is learned through experiences rather than innate and that the acceptance of the fundamental truth of the things a person perceives is essential to a person's moral and spiritual health. In the ''Letter to Pythocles'', he states, "If a person fights the clear evidence of his senses he will never be able to share in genuine tranquility." Epicurus regarded gut feelings as the ultimate authority on matters of morality and held that whether a person feels an action is right or wrong is a far more cogent guide to whether that act really is right or wrong than abstracts maxims, strict codified rules of ethics, or even reason itself.

Epicurus permitted that any and every statement that is not directly contrary to human perception has the possibility to be true. Nonetheless, anything contrary to a person's experience can be ruled out as false. Epicureans often used analogies to everyday experience to support their argument of so-called "imperceptibles", which included anything that a human being cannot perceive, such as the motion of atoms. In line with this principle of non-contradiction, the Epicureans believed that events in the natural world may have multiple causes that are all equally possible and probable. Lucretius writes in ''On the Nature of Things'', as translated by William Ellery Leonard:

Epicurus strongly favored naturalistic explanations over theological ones. In his ''Letter to Pythocles'', he offers four different possible natural explanations for thunder, six different possible natural explanations for lightning, three for snow, three for comets, two for rainbows, two for earthquakes, and so on. Although all of these explanations are now known to be false, they were an important step in the history of science, because Epicurus was trying to explain natural phenomena using natural explanations, rather than resorting to inventing elaborate stories about gods and mythic heroes.There be, besides, some thing Of which 'tis not enough one only cause To stateвҖ”but rather several, whereof one Will be the true: lo, if thou shouldst espy Lying afar some fellow's lifeless corse, 'Twere meet to name all causes of a death, That cause of his death might thereby be named: For prove thou mayst he perished not by steel, By cold, nor even by poison nor disease, Yet somewhat of this sort hath come to him We knowвҖ”And thus we have to say the same In divers cases.

Ethics

Epicurus was a hedonist, meaning he taught that what is pleasurable is morally good and what is painful is morally evil. He idiosyncratically defined "pleasure" as the absence of suffering and taught that all humans should seek to attain the state of ''

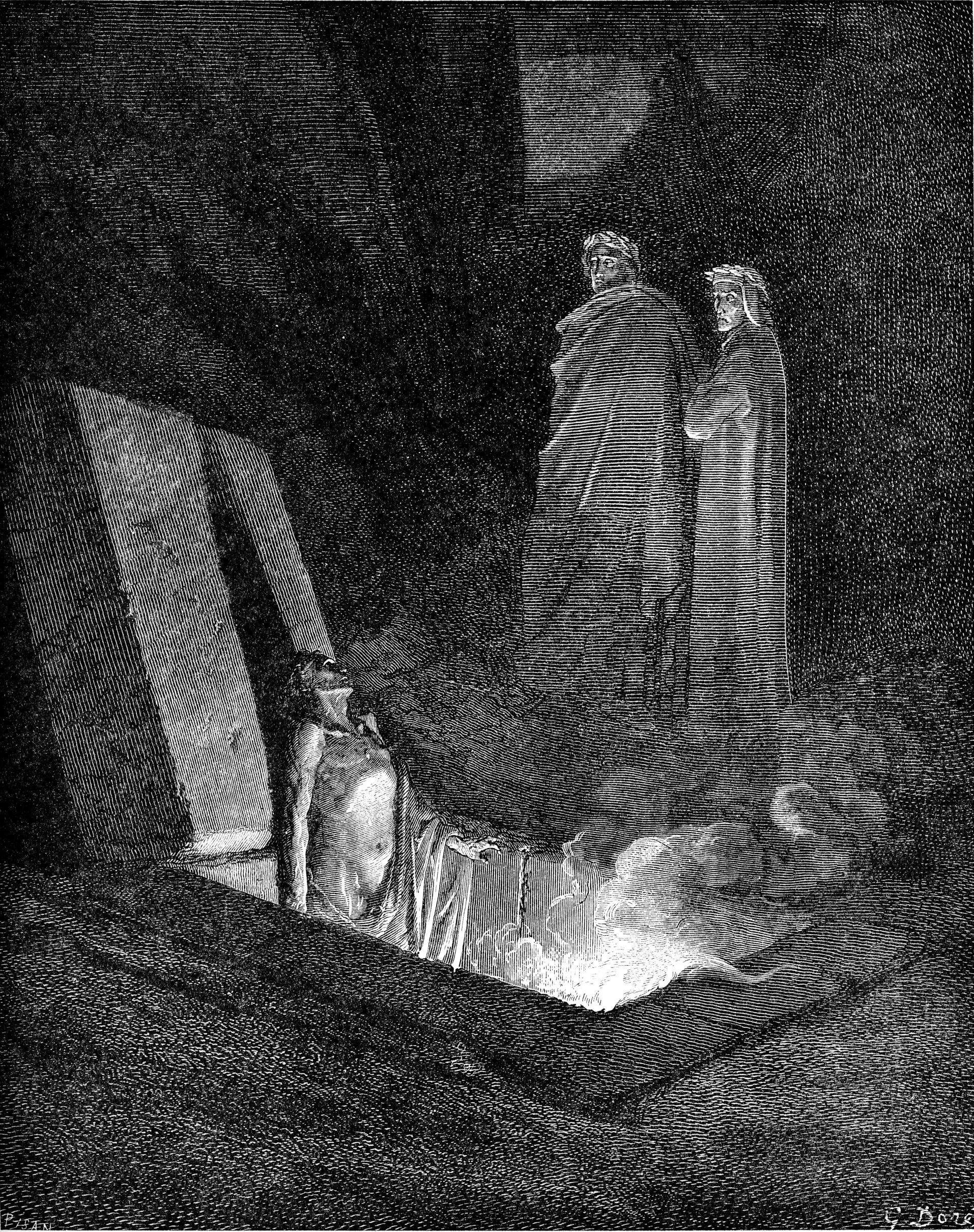

Epicurus was a hedonist, meaning he taught that what is pleasurable is morally good and what is painful is morally evil. He idiosyncratically defined "pleasure" as the absence of suffering and taught that all humans should seek to attain the state of ''ataraxia

''Ataraxia'' (Greek: бјҖП„ОұПҒОұОҫОҜОұ, from ("a-", negation) and ''tarachД“'' "disturbance, trouble"; hence, "unperturbedness", generally translated as "imperturbability", "equanimity", or "tranquility") is a Greek term first used in Ancient Gre ...

'', meaning "untroubledness", a state in which the person is completely free from all pain or suffering. He argued that most of the suffering which human beings experience is caused by the irrational fears of death, divine retribution

Divine retribution is supernatural punishment of a person, a group of people, or everyone by a deity in response to some action. Many cultures have a story about how a deity exacted punishment upon previous inhabitants of their land, causing th ...

, and punishment in the afterlife. In his ''Letter to Menoeceus'', Epicurus explains that people seek wealth and power on account of these fears, believing that having more money, prestige, or political clout will save them from death. He, however, maintains that death is the end of existence, that the terrifying stories of punishment in the afterlife are ridiculous superstitions, and that death is therefore nothing to be feared. He writes in his ''Letter to Menoeceus'': "Accustom thyself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply sentience, and death is the privation of all sentience;... Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not." From this doctrine arose the Epicurean epitaph: ''Non fui, fui, non-sum, non-curo'' ("I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care"), which is inscribed on the gravestones of his followers and seen on many ancient gravestones of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, О’ОұПғО№О»ОөОҜОұ П„бҝ¶ОҪ бҝ¬ПүОјОұОҜПүОҪ, BasileГӯa tГҙn RhЕҚmaГӯЕҚn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. This quotation is often used today at humanist funerals.

The Tetrapharmakos

The Principal Doctrines are forty authoritative conclusions set up as official doctrines by the founders of Epicureanism: Epicurus of Samos, Metrodorus of Lampsacus, Hermarchus of Mitilene and Polyaenus of Lampsacus. The first four doctrines make ...

presents a summary of the key points of Epicurean ethics:

* Don't fear god

* Don't worry about death

* What is good is easy to get

* What is terrible is easy to endure

Although Epicurus has been commonly misunderstood as an advocate of the rampant pursuit of pleasure, he, in fact, maintained that a person can only be happy and free from suffering by living wisely, soberly, and morally. He strongly disapproved of raw, excessive sensuality and warned that a person must take into account whether the consequences of his actions will result in suffering, writing, "the pleasant life is produced not by a string of drinking bouts and revelries, nor by the enjoyment of boys and women, nor by fish and the other items on an expensive menu, but by sober reasoning." He also wrote that a single good piece of cheese could be equally pleasing as an entire feast. Furthermore, Epicurus taught that "it is not possible to live pleasurably without living sensibly and nobly and justly", because a person who engages in acts of dishonesty or injustice will be "loaded with troubles" on account of his own guilty conscience and will live in constant fear that his wrongdoings will be discovered by others. A person who is kind and just to others, however, will have no fear and will be more likely to attain ''ataraxia''.

Epicurus distinguished between two different types of pleasure: "moving" pleasures (ОәОұП„бҪ° ОәОҜОҪО·ПғО№ОҪ бјЎОҙОҝОҪОұОҜ) and "static" pleasures (ОәОұП„ОұПғП„О·ОјОұП„О№ОәОұбҪ¶ бјЎОҙОҝОҪОұОҜ).Diogenes LaГ«rtius

Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

, ''The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'', X:136. "Moving" pleasures occur when one is in the process of satisfying a desire and involve an active titillation of the senses. After one's desires have been satisfied (e.g. when one is full after eating), the pleasure quickly goes away and the suffering of wanting to fulfill the desire again returns. For Epicurus, static pleasures are the best pleasures because moving pleasures are always bound up with pain. Epicurus had a low opinion of sex and marriage, regarding both as having dubious value. Instead, he maintained that platonic friendships are essential to living a happy life. One of the ''Principal Doctrines'' states, "Of the things wisdom acquires for the blessedness of life as a whole, far the greatest is the possession of friendship." He also taught that philosophy is itself a pleasure to engage in. One of the quotes from Epicurus recorded in the ''Vatican Sayings'' declares, "In other pursuits, the hard-won fruit comes at the end. But in philosophy, delight keeps pace with knowledge. It is not after the lesson that enjoyment comes: learning and enjoyment happen at the same time."

Epicurus distinguishes between three types of desires: natural and necessary, natural but unnecessary, and vain and empty. Natural and necessary desires include the desires for food and shelter. These are easy to satisfy, difficult to eliminate, bring pleasure when satisfied, and are naturally limited. Going beyond these limits produces unnecessary desires, such as the desire for luxury foods. Although food is necessary, luxury food is not necessary. Correspondingly, Epicurus advocates a life of hedonistic moderation by reducing desire, thus eliminating the unhappiness caused by unfulfilled desires. Vain desires include desires for power, wealth, and fame. These are difficult to satisfy because no matter how much one gets, one can always want more. These desires are inculcated by society and by false beliefs about what we need. They are not natural and are to be shunned.

Epicurus' teachings were introduced into medical philosophy and practice by the Epicurean doctor Asclepiades of Bithynia

Asclepiades ( el, бјҲПғОәО»О·ПҖО№О¬ОҙО·ПӮ; c. 129/124 BC вҖ“ 40 BC), sometimes called Asclepiades of Bithynia or Asclepiades of Prusa, was a Greek physician born at Prusias-on-Sea in Bithynia in Anatolia and who flourished at Rome, where he pr ...

, who was the first physician who introduced Greek medicine in Rome. Asclepiades introduced the friendly, sympathetic, pleasing and painless treatment of patients. He advocated humane treatment of mental disorders, had insane persons freed from confinement and treated them with natural therapy, such as diet and massages. His teachings are surprisingly modern; therefore Asclepiades is considered to be a pioneer physician in psychotherapy, physical therapy and molecular medicine.

Physics

Epicurus writes in his '' Letter to Herodotus'' (not the historian) that " nothing ever arises from the nonexistent", indicating that all events therefore have causes, regardless of whether those causes are known or unknown. Similarly, he also writes that nothing ever passes away into nothingness, because, "if an object that passes from our view were completely annihilated, everything in the world would have perished, since that into which things were dissipated would be nonexistent." He therefore states: "The totality of things was always just as it is at present and will always remain the same because there is nothing into which it can change, inasmuch as there is nothing outside the totality that could intrude and effect change." Like Democritus before him, Epicurus taught that allmatter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

is entirely made of extremely tiny particles called "atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, and ...

s" ( grc-gre, бј„П„ОҝОјОҝПӮ; ', meaning "indivisible"). For Epicurus and his followers, the existence of atoms was a matter of empirical observation; Epicurus's devoted follower, the Roman poet Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; вҖ“ ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

, cites the gradual wearing down of rings from being worn, statues from being kissed, stones from being dripped on by water, and roads from being walked on in ''On the Nature of Things'' as evidence for the existence of atoms as tiny, imperceptible particles.

Also like Democritus, Epicurus was a materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

who taught that the only things that exist are atoms and void. Void occurs in any place where there are no atoms. Epicurus and his followers believed that atoms and void are both infinite and that the universe is therefore boundless. In ''On the Nature of Things'', Lucretius argues this point using the example of a man throwing a javelin at the theoretical boundary of a finite universe. He states that the javelin must either go past the edge of the universe, in which case it is not really a boundary, or it must be blocked by something and prevented from continuing its path, but, if that happens, then the object blocking it must be outside the confines of the universe. As a result of this belief that the universe and the number of atoms in it are infinite, Epicurus and the Epicureans believed that there must also be infinitely many worlds within the universe.

Epicurus taught that the motion of atoms is constant, eternal, and without beginning or end. He held that there are two kinds of motion: the motion of atoms and the motion of visible objects. Both kinds of motion are real and not illusory. Democritus had described atoms as not only eternally moving, but also eternally flying through space, colliding, coalescing, and separating from each other as necessary. In a rare departure from Democritus's physics, Epicurus posited the idea of atomic "swerve" ( '; la, clinamen

Clinamen (; plural ''clinamina'', derived from ''clД«nДҒre'', to incline) is the Latin name Lucretius gave to the unpredictable swerve of atoms, in order to defend the atomistic doctrine of Epicurus. In modern English it has come more generally to ...

), one of his best-known original ideas. According to this idea, atoms, as they are travelling through space, may deviate slightly from the course they would ordinarily be expected to follow. Epicurus's reason for introducing this doctrine was because he wanted to preserve the concepts of free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actio ...

and ethical responsibility while still maintaining the deterministic

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

physical model of atomism. Lucretius describes it, saying, "It is this slight deviation of primal bodies, at indeterminate times and places, which keeps the mind as such from experiencing an inner compulsion in doing everything it does and from being forced to endure and suffer like a captive in chains."

Epicurus was first to assert human freedom as a result of the fundamental indeterminism in the motion of atoms. This has led some philosophers to think that, for Epicurus, free will was ''caused directly by chance''. In his ''On the Nature of Things'', Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; вҖ“ ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

appears to suggest this in the best-known passage on Epicurus' position. In his ''Letter to Menoeceus'', however, Epicurus follows Aristotle and clearly identifies ''three'' possible causes: "some things happen of necessity, others by chance, others through our own agency." Aristotle said some things "depend on us" (''eph'hemin''). Epicurus agreed, and said it is to these last things that praise

Praise as a form of social interaction expresses recognition, reassurance or admiration.

Praise is expressed verbally as well as by body language (facial expression and gestures).

Verbal praise consists of a positive evaluations of another's a ...

and blame

Blame is the act of censuring, holding responsible, or making negative statements about an individual or group that their actions or inaction are socially or morally irresponsible, the opposite of praise. When someone is morally responsible for ...

naturally attach. For Epicurus, the "swerve" of the atoms simply defeated determinism

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

to leave room for autonomous agency.

Theology

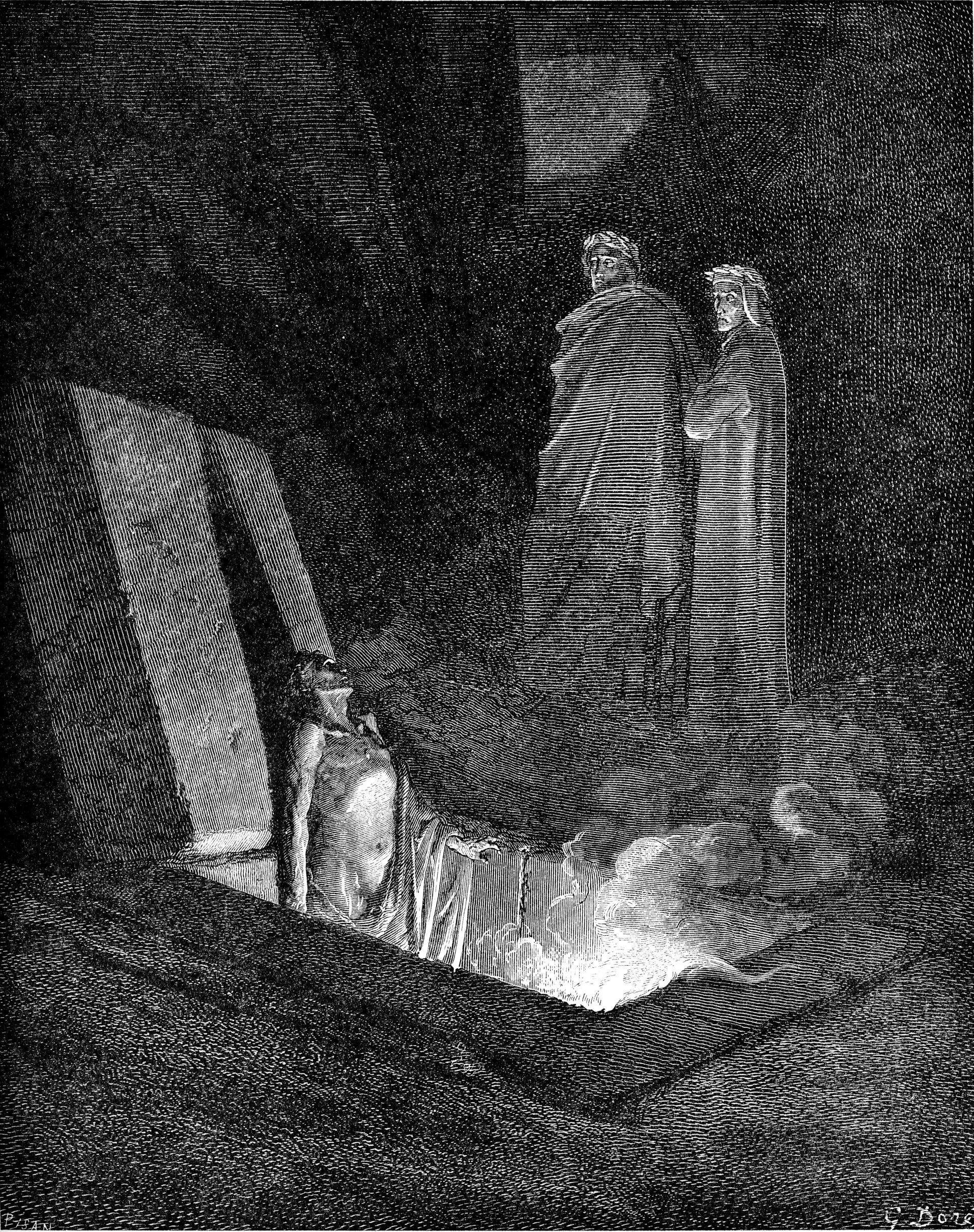

In his ''Letter to Menoeceus'', a summary of his own moral and theological teachings, the first piece of advice Epicurus himself gives to his student is: "First, believe that a god is an indestructible and blessed animal, in accordance with the general conception of god commonly held, and do not ascribe to god anything foreign to his indestructibility or repugnant to his blessedness." Epicurus maintained that he and his followers knew that the gods exist because "our knowledge of them is a matter of clear and distinct perception", meaning that people can empirically sense their presences. He did not mean that people can see the gods as physical objects, but rather that they can see visions of the gods sent from the remote regions of interstellar space in which they actually reside. According to George K. Strodach, Epicurus could have easily dispensed of the gods entirely without greatly altering his materialist worldview, but the gods still play one important function in Epicurus's theology as the paragons of moral virtue to be emulated and admired.

Epicurus rejected the conventional Greek view of the gods as anthropomorphic beings who walked the earth like ordinary people, fathered illegitimate offspring with mortals, and pursued personal feuds. Instead, he taught that the gods are morally perfect, but detached and immobile beings who live in the remote regions of interstellar space. In line with these teachings, Epicurus adamantly rejected the idea that deities were involved in human affairs in any way. Epicurus maintained that the gods are so utterly perfect and removed from the world that they are incapable of listening to prayers or supplications or doing virtually anything aside from contemplating their own perfections. In his ''Letter to Herodotus'', he specifically denies that the gods have any control over natural phenomena, arguing that this would contradict their fundamental nature, which is perfect, because any kind of worldly involvement would tarnish their perfection. He further warned that believing that the gods control natural phenomena would only mislead people into believing the superstitious view that the gods punish humans for wrongdoing, which only instills fear and prevents people from attaining ''ataraxia''.

Epicurus himself criticizes popular religion in both his ''Letter to Menoeceus'' and his ''Letter to Herodotus'', but in a restrained and moderate tone. Later Epicureans mainly followed the same ideas as Epicurus, believing in the existence of the gods, but emphatically rejecting the idea of divine providence. Their criticisms of popular religion, however, are often less gentle than those of Epicurus himself. The ''Letter to Pythocles'', written by a later Epicurean, is dismissive and contemptuous towards popular religion and Epicurus's devoted follower, the Roman poet

In his ''Letter to Menoeceus'', a summary of his own moral and theological teachings, the first piece of advice Epicurus himself gives to his student is: "First, believe that a god is an indestructible and blessed animal, in accordance with the general conception of god commonly held, and do not ascribe to god anything foreign to his indestructibility or repugnant to his blessedness." Epicurus maintained that he and his followers knew that the gods exist because "our knowledge of them is a matter of clear and distinct perception", meaning that people can empirically sense their presences. He did not mean that people can see the gods as physical objects, but rather that they can see visions of the gods sent from the remote regions of interstellar space in which they actually reside. According to George K. Strodach, Epicurus could have easily dispensed of the gods entirely without greatly altering his materialist worldview, but the gods still play one important function in Epicurus's theology as the paragons of moral virtue to be emulated and admired.

Epicurus rejected the conventional Greek view of the gods as anthropomorphic beings who walked the earth like ordinary people, fathered illegitimate offspring with mortals, and pursued personal feuds. Instead, he taught that the gods are morally perfect, but detached and immobile beings who live in the remote regions of interstellar space. In line with these teachings, Epicurus adamantly rejected the idea that deities were involved in human affairs in any way. Epicurus maintained that the gods are so utterly perfect and removed from the world that they are incapable of listening to prayers or supplications or doing virtually anything aside from contemplating their own perfections. In his ''Letter to Herodotus'', he specifically denies that the gods have any control over natural phenomena, arguing that this would contradict their fundamental nature, which is perfect, because any kind of worldly involvement would tarnish their perfection. He further warned that believing that the gods control natural phenomena would only mislead people into believing the superstitious view that the gods punish humans for wrongdoing, which only instills fear and prevents people from attaining ''ataraxia''.

Epicurus himself criticizes popular religion in both his ''Letter to Menoeceus'' and his ''Letter to Herodotus'', but in a restrained and moderate tone. Later Epicureans mainly followed the same ideas as Epicurus, believing in the existence of the gods, but emphatically rejecting the idea of divine providence. Their criticisms of popular religion, however, are often less gentle than those of Epicurus himself. The ''Letter to Pythocles'', written by a later Epicurean, is dismissive and contemptuous towards popular religion and Epicurus's devoted follower, the Roman poet Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; вҖ“ ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

( 99 BC вҖ“ 55 BC), passionately assailed popular religion in his philosophical poem ''On the Nature of Things

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( вҖ“ c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7 ...

''. In this poem, Lucretius declares that popular religious practices not only do not instill virtue, but rather result in "misdeeds both wicked and ungodly", citing the mythical sacrifice of Iphigenia as an example. Lucretius argues that divine creation and providence are illogical, not because the gods do not exist, but rather because these notions are incompatible with the Epicurean principles of the gods' indestructibility and blessedness. The later Pyrrhonist

Pyrrho of Elis (; grc, О ПҚПҒПҒПүОҪ бҪҒ бјЁО»Оөбҝ–ОҝПӮ, PyrrhРҫМ„n ho Д’leios; ), born in Elis, Greece, was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Life

...

philosopher Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, ОЈОӯОҫП„ОҝПӮ бјҳОјПҖОөО№ПҒО№ОәПҢПӮ, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

( 160 вҖ“ 210 AD) rejected the teachings of the Epicureans specifically because he regarded them as theological "Dogmaticists".

Epicurean paradox

The Epicurean paradox or riddle of Epicurus or Epicurus' trilemma is a version of the

The Epicurean paradox or riddle of Epicurus or Epicurus' trilemma is a version of the problem of evil

The problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,The Problem of Evil, Michael TooleyThe Internet Encyclope ...

. Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 вҖ“ c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Cr ...

attributes this trilemma

A trilemma is a difficult choice from three options, each of which is (or appears) unacceptable or unfavourable. There are two logically equivalent ways in which to express a trilemma: it can be expressed as a choice among three unfavourable option ...

to Epicurus in ''De Ira Dei'', 13, 20-21:

God, he says, either wishes to take away evils, and is unable; or He is able, and is unwilling; or He is neither willing nor able, or He is both willing and able. If He is willing and is unable, He is feeble, which is not in accordance with the character of God; if He is able and unwilling, He isIn ''Dialogues concerning Natural Religion'' (1779),envious Envy is an emotion which occurs when a person lacks another's quality, skill, achievement, or possession and either desires it or wishes that the other lacked it. Aristotle defined envy as pain at the sight of another's good fortune, stirred b ..., which is equally at variance with God; if He is neither willing nor able, He is both envious and feeble, and therefore not God; if He is both willing and able, which alone is suitable to God, from what source then are evils? Or why does He not remove them?

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) вҖ“ 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''EncyclopГҰdia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

also attributes the argument to Epicurus:

EpicurusвҖҷs old questions are yet unanswered. Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?No extant writings of Epicurus contain this argument. However, the vast majority of Epicurus's writings have been lost and it is possible that some form of this argument may have been found in his lost treatise ''On the Gods'', which Diogenes LaГ«rtius describes as one of his greatest works. If Epicurus really did make some form of this argument, it would not have been an argument against the existence of deities, but rather an argument against divine providence. Epicurus's extant writings demonstrate that he did believe in the existence of deities. Furthermore, religion was such an integral part of daily life in Greece during the early Hellenistic Period that it is doubtful anyone during that period could have been an atheist in the modern sense of the word. Instead, the Greek word (''ГЎtheos''), meaning "without a god", was used as a term of abuse, not as an attempt to describe a person's beliefs.

Politics

Epicurus promoted an innovative theory of justice as a social contract. Justice, Epicurus said, is an agreement neither to harm nor be harmed, and we need to have such a contract in order to enjoy fully the benefits of living together in a well-ordered society. Laws and punishments are needed to keep misguided fools in line who would otherwise break the contract. But the wise person sees the usefulness of justice, and because of his limited desires, he has no need to engage in the conduct prohibited by the laws in any case. Laws that are useful for promoting happiness are just, but those that are not useful are not just. (''Principal Doctrines'' 31вҖ“40) Epicurus discouraged participation in politics, as doing so leads to perturbation and status seeking. He instead advocated not drawing attention to oneself. This principle is epitomised by the phrase ''lathe biЕҚsas'' (), meaning "live in obscurity", "get through life without drawing attention to yourself", i.e., live without pursuing glory or wealth or power, but anonymously, enjoying little things like food, the company of friends, etc.Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, О О»ОҝПҚП„ОұПҒПҮОҝПӮ, ''PloГәtarchos''; ; вҖ“ after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

elaborated on this theme in his essay ''Is the Saying "Live in Obscurity" Right?'' (, ''An recte dictum sit latenter esse vivendum'') 1128c; cf. Flavius Philostratus, ''Vita Apollonii'' 8.28.12.

Works

Epicurus was an extremely prolific writer. According to Diogenes LaГ«rtius, he wrote around 300 treatises on a variety of subjects. More original writings of Epicurus have survived to the present day than of any other Hellenistic Greek philosopher. Nonetheless, the vast majority of everything he wrote has now been lost and most of what is known about Epicurus's teachings come from the writings of his later followers, particularly the Roman poet Lucretius. The only surviving complete works by Epicurus are three relatively lengthy letters, which are quoted in their entirety in Book X of

Epicurus was an extremely prolific writer. According to Diogenes LaГ«rtius, he wrote around 300 treatises on a variety of subjects. More original writings of Epicurus have survived to the present day than of any other Hellenistic Greek philosopher. Nonetheless, the vast majority of everything he wrote has now been lost and most of what is known about Epicurus's teachings come from the writings of his later followers, particularly the Roman poet Lucretius. The only surviving complete works by Epicurus are three relatively lengthy letters, which are quoted in their entirety in Book X of Diogenes LaГ«rtius

Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

's ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

'', and two groups of quotes: the ''Principal Doctrines'' (ОҡПҚПҒО№ОұО№ О”ПҢОҫОұО№), which are likewise preserved through quotation by Diogenes LaГ«rtius, and the ''Vatican Sayings'', preserved in a manuscript from the Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library ( la, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, it, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City. Formally es ...

that was first discovered in 1888. In the ''Letter to Herodotus'' and the ''Letter to Pythocles'', Epicurus summarizes his philosophy on nature and, in the ''Letter to Menoeceus'', he summarizes his moral teachings. Numerous fragments of Epicurus's lost thirty-seven volume treatise '' On Nature'' have been found among the charred papyrus fragments at the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

. Scholars first began attempting to unravel and decipher these scrolls in 1800, but the efforts are painstaking and are still ongoing.

According to Diogenes Laertius (10.27-9), the major works of Epicurus include:

# On Nature, in 37 books

# On Atoms and the Void

# On Love

# Abridgment of the Arguments employed against the Natural Philosophers

# Against the Megarians

# Problems

# Fundamental Propositions (''Kyriai Doxai'')

# On Choice and Avoidance

# On the Chief Good

# On the Criterion (the Canon)

# Chaeridemus,

# On the Gods

# On Piety

# Hegesianax

# Four essays on Lives

# Essay on Just Dealing

# Neocles

# Essay addressed to Themista

# The Banquet (Symposium)

# Eurylochus

# Essay addressed to Metrodorus

# Essay on Seeing

# Essay on the Angle in an Atom

# Essay on Touch

# Essay on Fate

# Opinions on the Passions

# Treatise addressed to Timocrates

# Prognostics

# Exhortations

# On Images

# On Perceptions

# Aristobulus

# Essay on Music (i.e., on music, poetry, and dance)

# On Justice and the other Virtues

# On Gifts and Gratitude

# Polymedes

# Timocrates (three books)

# Metrodorus (five books)

# Antidorus (two books)

# Opinions about Diseases and Death, addressed to Mithras

# Callistolas

# Essay on Kingly Power

# Anaximenes

# Letters

Legacy

Ancient Epicureanism

Epicureanism was extremely popular from the very beginning.Diogenes LaГ«rtius

Diogenes LaГ«rtius ( ; grc-gre, О”О№ОҝОіОӯОҪО·ПӮ ОӣОұОӯПҒП„О№ОҝПӮ, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

records that the number of Epicureans throughout the world exceeded the populations of entire cities. Nonetheless, Epicurus was not universally admired and, within his own lifetime, he was vilified as an ignorant buffoon and egoistic sybarite. He remained the most simultaneously admired and despised philosopher in the Mediterranean for the next nearly five centuries. Epicureanism rapidly spread beyond the Greek mainland all across the Mediterranean world. By the first century BC, it had established a strong foothold in Italy. The Roman orator Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вҖ“ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

(106 вҖ“ 43 BC), who deplored Epicurean ethics, lamented, "the Epicureans have taken Italy by storm."

The overwhelming majority of surviving Greek and Roman sources are vehemently negative towards Epicureanism and, according to Pamela Gordon, they routinely depict Epicurus himself as "monstrous or laughable". Many Romans in particular took a negative view of Epicureanism, seeing its advocacy of the pursuit of ''voluptas'' ("pleasure") as contrary to the Roman ideal of ''virtus'' ("manly virtue"). The Romans therefore often stereotyped Epicurus and his followers as weak and effeminate. Prominent critics of his philosophy include prominent authors such as the Roman Stoic Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

( 4 BC вҖ“ AD 65) and the Greek Middle Platonist

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC вҖ“ when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy вҖ“ until the development of neoplatonism ...

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, О О»ОҝПҚП„ОұПҒПҮОҝПӮ, ''PloГәtarchos''; ; вҖ“ after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

( 46 вҖ“ 120), who both derided these stereotypes as immoral and disreputable. Gordon characterizes anti-Epicurean rhetoric as so "heavy-handed" and misrepresentative of Epicurus's actual teachings that they sometimes come across as "comical". In his ''De vita beata'', Seneca states that the "sect of Epicurus... has a bad reputation, and yet it does not deserve it." and compares it to "a man in a dress: your chastity remains, your virility is unimpaired, your body has not submitted sexually, but in your hand is a tympanum."

Epicureanism was a notoriously conservative philosophical school; although Epicurus's later followers did expand on his philosophy, they dogmatically retained what he himself had originally taught without modifying it. Epicureans and admirers of Epicureanism revered Epicurus himself as a great teacher of ethics, a savior, and even a god. His image was worn on finger rings, portraits of him were displayed in living rooms, and wealthy followers venerated likenesses of him in marble sculpture. His admirers revered his sayings as divine oracles, carried around copies of his writings, and cherished copies of his letters like the letters of an apostle. On the twentieth day of every month, admirers of his teachings would perform a solemn ritual to honor his memory. At the same time, opponents of his teachings denounced him with vehemence and persistence.