English Legend on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the

The word ''

The word ''

The pre-Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England was illiterate. Thus there is no contemporary written evidence produced by Anglo-Saxon pagans themselves. Instead, our primary textual source material derives from later authors, such as

The pre-Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England was illiterate. Thus there is no contemporary written evidence produced by Anglo-Saxon pagans themselves. Instead, our primary textual source material derives from later authors, such as

Archaeologically, the introduction of Norse paganism to Britain in this period is mostly visited in the mortuary evidence.

A number of Scandinavian furnished burial styles were also introduced that differed from the Christian churchyard burials then dominant in Late Anglo-Saxon England. Whether these represent clear pagan identity or not is however debated among archaeologists. Norse mythological scenes have also been identified on a number of stone carvings from the period, such as the

Archaeologically, the introduction of Norse paganism to Britain in this period is mostly visited in the mortuary evidence.

A number of Scandinavian furnished burial styles were also introduced that differed from the Christian churchyard burials then dominant in Late Anglo-Saxon England. Whether these represent clear pagan identity or not is however debated among archaeologists. Norse mythological scenes have also been identified on a number of stone carvings from the period, such as the

In pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon England, legends and other stories were transmitted orally instead of being written down; it is for this reason that very few survive today.

In both ''Beowulf'' and ''Deor's Lament'' there are references to the mythological smith Wayland the Smith, Weyland, and this figure also makes an appearance on the

In pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon England, legends and other stories were transmitted orally instead of being written down; it is for this reason that very few survive today.

In both ''Beowulf'' and ''Deor's Lament'' there are references to the mythological smith Wayland the Smith, Weyland, and this figure also makes an appearance on the

Place-name evidence may indicate some locations which were used as places of worship by the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons. However, no unambiguous archaeological evidence currently supports the interpretation of these sites as places of cultic practice. Two words that appear repeatedly in Old English place names and , have been interpreted as being references to cult spaces, however it is likely that the two terms had distinctive meanings. These locations were all found on high ground, with Wilson suggesting that these represented a communal place of worship for a specific group, such as the tribe, at a specific time of year. The archaeologist Sarah Semple also examined a number of such sites, noting that while they all reflected activity throughout later prehistory and the Romano-British period, they had little evidence from the sixth and seventh centuries CE. She suggested that rather than referring to specifically Anglo-Saxon cultic sites, was instead used in reference to "something British in tradition and usage."

Highlighting that while sites vary in their location, some being on high ground and others on low ground, Wilson noted that the majority were very close to ancient routeways. Accordingly, he suggested that the term denoted a "small, wayside shrine, accessible to the traveller". Given that some -sites were connected to the name of an individual, Wilson suggested that such individuals may have been the owner or guardian of the shrine.

A number of place-names including reference to pre-Christian deities compound these names with the Old English word ("wood", or "clearing in a wood"), and this may have attested to a Sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology, sacred grove at which cultic practice took place. A number of other place-names associate the deity's name with a high point in the landscape, such as or , which might represent that such spots were considered particularly appropriate for cultic practice. In six examples, the deity's name is associated with ("open land"), in which case these might have been sanctuaries located to specifically benefit the agricultural actions of the community.

Some Old English place names make reference to an animal's head, among them Gateshead ("Goat's Head") in Tyne and Wear and Worms Heath ("Snake's Head") in Surrey. It is possible that some of these names had pagan religious origins, perhaps referring to a sacrificed animal's head that was erected on a pole, or a carved representation of one; equally some or all of these place-names may have been descriptive metaphors for local landscape features.

Place-name evidence may indicate some locations which were used as places of worship by the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons. However, no unambiguous archaeological evidence currently supports the interpretation of these sites as places of cultic practice. Two words that appear repeatedly in Old English place names and , have been interpreted as being references to cult spaces, however it is likely that the two terms had distinctive meanings. These locations were all found on high ground, with Wilson suggesting that these represented a communal place of worship for a specific group, such as the tribe, at a specific time of year. The archaeologist Sarah Semple also examined a number of such sites, noting that while they all reflected activity throughout later prehistory and the Romano-British period, they had little evidence from the sixth and seventh centuries CE. She suggested that rather than referring to specifically Anglo-Saxon cultic sites, was instead used in reference to "something British in tradition and usage."

Highlighting that while sites vary in their location, some being on high ground and others on low ground, Wilson noted that the majority were very close to ancient routeways. Accordingly, he suggested that the term denoted a "small, wayside shrine, accessible to the traveller". Given that some -sites were connected to the name of an individual, Wilson suggested that such individuals may have been the owner or guardian of the shrine.

A number of place-names including reference to pre-Christian deities compound these names with the Old English word ("wood", or "clearing in a wood"), and this may have attested to a Sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology, sacred grove at which cultic practice took place. A number of other place-names associate the deity's name with a high point in the landscape, such as or , which might represent that such spots were considered particularly appropriate for cultic practice. In six examples, the deity's name is associated with ("open land"), in which case these might have been sanctuaries located to specifically benefit the agricultural actions of the community.

Some Old English place names make reference to an animal's head, among them Gateshead ("Goat's Head") in Tyne and Wear and Worms Heath ("Snake's Head") in Surrey. It is possible that some of these names had pagan religious origins, perhaps referring to a sacrificed animal's head that was erected on a pole, or a carved representation of one; equally some or all of these place-names may have been descriptive metaphors for local landscape features.

Archaeological investigation has displayed that structures or buildings were built inside a number of pagan cemeteries, and as David Wilson noted, "The evidence, then, from cemetery excavations is suggestive of small structures and features, some of which may perhaps be interpreted as shrines or sacred areas". In some cases, there is evidence of far smaller structures being built around or alongside individual graves, implying possible small shrines to the dead individual or individuals buried there.

Eventually, in the sixth and seventh centuries, the idea of burial mounds began to appear in Anglo-Saxon England, and in certain cases earlier burial mounds from the Neolithic, Bronze Age,

Archaeological investigation has displayed that structures or buildings were built inside a number of pagan cemeteries, and as David Wilson noted, "The evidence, then, from cemetery excavations is suggestive of small structures and features, some of which may perhaps be interpreted as shrines or sacred areas". In some cases, there is evidence of far smaller structures being built around or alongside individual graves, implying possible small shrines to the dead individual or individuals buried there.

Eventually, in the sixth and seventh centuries, the idea of burial mounds began to appear in Anglo-Saxon England, and in certain cases earlier burial mounds from the Neolithic, Bronze Age,

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

between the 5th and 8th centuries AD, during the initial period of Early Medieval England

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of ...

. A variant of Germanic paganism

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germ ...

found across much of north-western Europe, it encompassed a heterogeneous variety of beliefs and cultic practices, with much regional variation.

Developing from the earlier Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

religion of continental northern Europe, it was introduced to Britain following the Anglo-Saxon migration

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is the process which changed the language and culture of most of what became England from Romano-British to Germanic. The Germanic-speakers in Britain, themselves of diverse origins, eventually develope ...

in the mid 5th century, and remained the dominant belief system in England until the Christianisation

Christianization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise.2C -ize .28-isation.2C -ization.29, or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of ...

of its kingdoms between the 7th and 8th centuries, with some aspects gradually blending into folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

. The pejorative terms ''paganism'' and ''heathenism'' were first applied to this religion by Christian Anglo-Saxons, and it does not appear that these pagans had a name for their religion themselves; there has therefore been debate among contemporary scholars as to the appropriateness of continuing to describe these belief systems using this Christian terminology. Contemporary knowledge of Anglo-Saxon paganism derives largely from three sources: textual evidence produced by Christian Anglo-Saxons like Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

and Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the so ...

, place-name evidence, and archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

evidence of cultic practices. Further suggestions regarding the nature of Anglo-Saxon paganism have been developed through comparisons with the better-attested pre-Christian belief systems of neighbouring peoples such as the Norse.

Anglo-Saxon paganism was a polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

belief system, focused around a belief in deities known as the (singular ). The most prominent of these deities was probably Woden

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered Æsir, god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, v ...

; other prominent gods included Thunor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and ...

and Tiw. There was also a belief in a variety of other supernatural entities which inhabited the landscape, including elves

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic Prose Edda. He distinguishes "ligh ...

, nicor

Nicor Gas is an energy company headquartered in Naperville, Illinois. Its largest subsidiary, Nicor Gas, is a natural gas distribution company. Founded in 1954, the company serves more than two million customers in a service territory that en ...

, and dragons

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

. Cultic practice largely revolved around demonstrations of devotion, including sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exi ...

of inanimate objects and animals, to these deities, particularly at certain religious festivals during the year. There is some evidence for the existence of timber temples, although other cultic spaces might have been open-air, and would have included cultic trees and megaliths. Little is known about pagan conceptions of an afterlife, although such beliefs likely influenced funerary practices, in which the dead were either inhumed or cremated, typically with a selection of grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

. The belief system also likely included ideas about magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

and witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

, and elements that could be classified as a form of shamanism

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a Spirit world (Spiritualism), spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as tranc ...

.

The deities of this religion provided the basis for the names of the days of the week in the English language. What is known about the religion and its accompanying mythology have since influenced both literature and Modern Paganism

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Afric ...

.

Definition

pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

'' is a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

term that was used by Christians in Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom o ...

to designate non-Christians. In Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

, the vernacular language of Anglo-Saxon England, the equivalent term was ("heathen"), a word that was cognate to the Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

, both of which may derive from a Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

word, . Both ''pagan'' and ''heathen'' were terms that carried pejorative overtones, with also being used in Late Anglo-Saxon texts to refer to criminals and others deemed to have not behaved according to Christian teachings. The term "paganism" was one used by Christians as a form of other

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

ing, and as the archaeologist Neil Price put it, in the Anglo-Saxon context, "paganism" is "largely an empty concept defined by what it is not (Christianity)".

There is no evidence that anyone living in Anglo-Saxon England ever described themselves as a "pagan" or understood there to be a singular religion, "paganism", that stood as a monolithic alternative to Christianity. These pagan belief systems would have been inseparable from other aspects of daily life. According to the archaeologists Martin Carver

Martin Oswald Hugh Carver, FSA, Hon FSA Scot, (born 8 July 1941) is Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at the University of York, England, director of the Sutton Hoo Research Project and a leading exponent of new methods in excavation and surve ...

, Alex Sanmark, and Sarah Semple, Anglo-Saxon paganism was "not a religion with supraregional rules and institutions but a loose term for a variety of local intellectual world views." Carver stressed that, in Anglo-Saxon England, neither paganism nor Christianity represented "homogenous intellectual positions or canons and practice"; instead, there was "considerable interdigitation" between the two. As a phenomenon, this belief system lacked any apparent rules or consistency, and exhibited both regional and chronological variation. The archaeologist Aleks Pluskowski suggested that it is possible to talk of "multiple Anglo-Saxon 'paganisms'".

Adopting the terminology of the sociologist of religion

Sociology of religion is the study of the beliefs, practices and organizational forms of religion using the tools and methods of the discipline of sociology. This objective investigation may include the use both of quantitative methods (surveys, ...

Max Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas profo ...

, the historian Marilyn Dunn described Anglo-Saxon paganism as a "world accepting" religion, one which was "concerned with the here and now" and in particular with issues surrounding the safety of the family, prosperity, and the avoidance of drought or famine. Also adopting the categories of Gustav Mensching

Gustav Mensching (6 May 1901 – 30 September 1978) was a German theologian who was Professor of Comparative Religious Studies at the University of Bonn from 1936 to 1972.

Biography

Gustav Mensching was born in Hanover, Germany on 6 May 1901, the ...

, she described Anglo-Saxon paganism as a "folk religion

In religious studies and folkloristics, folk religion, popular religion, traditional religion or vernacular religion comprises various forms and expressions of religion that are distinct from the official doctrines and practices of organized re ...

", in that its adherents concentrated on survival and prosperity in this world.

Using the expressions "paganism" or "heathenism" when discussing pre-Christian belief systems in Anglo-Saxon England is problematic. Historically, many early scholars of the Anglo-Saxon period used these terms to describe the religious beliefs in England before its conversion to Christianity in the 7th century. Several later scholars criticised this approach; as the historian Ian N. Wood

Ian N. Wood, (born 1950) is an English scholar of early medieval history, and a professor at the University of Leeds who specializes in the history of the Merovingian dynasty and the missionary efforts on the European continent. Patrick J. Gear ...

stated, using the term "pagan" when discussing the Anglo-Saxons forces the scholar to adopt "the cultural constructs and value judgements of the early medieval hristianmissionaries" and thus obscures scholarly understandings of the so-called pagans' own perspectives.

At present, while some Anglo-Saxonists have ceased using the terms "paganism" or "pagan" when discussing the early Anglo-Saxon period, others have continued to do so, viewing these terms as a useful means of designating something that is not Christian yet which is still identifiably religious. The historian John Hines proposed "traditional religion" as a better alternative, although Carver cautioned against this, noting that Britain in the 5th to the 8th century was replete with new ideas and thus belief systems of that period were not particularly "traditional". The term "pre-Christian" religion has also been used; this avoids the judgemental connotations of "paganism" and "heathenism" but is not always chronologically accurate.

Evidence

The pre-Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England was illiterate. Thus there is no contemporary written evidence produced by Anglo-Saxon pagans themselves. Instead, our primary textual source material derives from later authors, such as

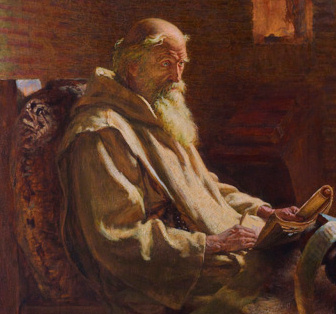

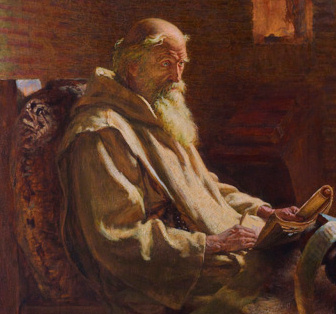

The pre-Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England was illiterate. Thus there is no contemporary written evidence produced by Anglo-Saxon pagans themselves. Instead, our primary textual source material derives from later authors, such as Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

and the anonymous author of the ''Life of St Wilfrid

The ''Vita Sancti Wilfrithi'' or ''Life of St Wilfrid'' (spelled "Wilfrid" in the modern era) is an early 8th-century hagiographic text recounting the life of the Northumbrian bishop, Wilfrid. Although a hagiography, it has few miracles, while ...

'', who wrote in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

rather than in Old English. These writers were not interested in providing a full portrait of the Anglo-Saxons' pre-Christian belief systems, and thus our textual portrayal of these religious beliefs is fragmentary and incidental. Also perhaps useful are the writings of those Christian Anglo-Saxon missionaries who were active in converting the pagan societies of continental Europe, namely Willibrord

Willibrord (; 658 – 7 November AD 739) was an Anglo-Saxon missionary and saint, known as the "Apostle to the Frisians" in the modern Netherlands. He became the first bishop of Utrecht and died at Echternach, Luxembourg.

Early life

His fathe ...

and Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of ...

, as well as the writings of the 1st century AD Roman writer Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, who commented upon the pagan religions of the Anglo-Saxons' ancestors in continental Europe. The historian Frank Stenton

Sir Frank Merry Stenton, FBA (17 May 1880 – 15 September 1967) was an English historian of Anglo-Saxon England, and president of the Royal Historical Society (1937–1945).

The son of Henry Stenton of Southwell, Nottinghamshire, he was edu ...

commented that the available texts only provide us with "a dim impression" of pagan religion in Anglo-Saxon England, while similarly, the archaeologist David Wilson commented that written sources "should be treated with caution and viewed as suggestive rather than in any way definitive".

Far fewer textual records discuss Anglo-Saxon paganism than the pre-Christian belief systems found in nearby Ireland, Francia, or Scandinavia. There is no neat, formalised account of Anglo-Saxon pagan beliefs as there is for instance for Classical mythology

Classical mythology, Greco-Roman mythology, or Greek and Roman mythology is both the body of and the study of myths from the ancient Greeks and ancient Romans as they are used or transformed by cultural reception. Along with philosophy and polit ...

and Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern period ...

. Although many scholars have used Norse mythology as a guide to understanding the beliefs of pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon England, caution has been expressed as to the utility of this approach. Stenton assumes that the connection between Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian paganism occurred "in a past which was already remote" at the time of the Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain, and claims that there was clear diversity among the pre-Christian belief systems of Scandinavia itself, further complicating the use of Scandinavian material to understand that of England. Conversely, the historian Brian Branston argued for the use of Old Norse sources to better understand Anglo-Saxon pagan beliefs, recognising mythological commonalities between the two rooted in their common ancestry.

Old English place-names also provide some insight into the pre-Christian beliefs and practices of Anglo-Saxon England. Some of these place-names reference the names of particular deities, while others use terms that refer to cultic practices that took place there. In England, these two categories remain separate, unlike in Scandinavia, where certain place-names exhibit both features. Those place-names which carry possible pagan associations are centred primarily in the centre and south-east of England, while no obvious examples are known from Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

or East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

. It is not clear why such names are rarer or non-existent in certain parts of the country; it may be due to changes in nomenclature brought about by Scandinavian settlement in the Late Anglo-Saxon period or because of evangelising efforts by later Christian authorities. In 1941, Stenton suggested that "between fifty and sixty sites of heathen worship" could be identified through the place-name evidence, although in 1961 the place-name scholar Margaret Gelling

Margaret Joy Gelling, (''née'' Midgley; 29 November 1924 – 24 April 2009) was an English toponymist, known for her extensive studies of English place-names. She served as President of the English Place-Name Society from 1986 to 1998, and Vi ...

cautioned that only forty-five of these appeared reliable. The literature specialist Philip A. Shaw has however warned that many of these sites might not have been named by pagans but by later Christian Anglo-Saxons, reflecting spaces that were perceived to be heathen from a Christian perspective.

According to Wilson, the archaeological evidence is "prolific and hence is potentially the most useful in the study of paganism" in Anglo-Saxon England. Archaeologically, the realms of religion, ritual, and magic can only be identified if they affected material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects creat ...

. As such, scholarly understandings of pre-Christian religion in Anglo-Saxon England are reliant largely on rich burials and monumental buildings, which exert as much of a political purpose as a religious one. Metalwork items discovered by metal detector

A metal detector is an instrument that detects the nearby presence of metal. Metal detectors are useful for finding metal objects on the surface, underground, and under water. The unit itself, consist of a control box, and an adjustable shaft, ...

ists have also contributed to the interpretation of Anglo-Saxon paganism. The world-views of the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons would have impinged on all aspects of everyday life, making it particularly difficult for modern scholars to separate Anglo-Saxon ritual activities as something distinct from other areas of daily life. Much of this archaeological material comes from the period in which pagan beliefs were being supplanted by Christianity, and thus an understanding of Anglo-Saxon paganism must be seen in tandem with the archaeology of the conversion.

Based on the evidence available, the historian John Blair stated that the pre-Christian religion of Anglo-Saxon England largely resembled "that of the pagan Britons under Roman rule... at least in its outward forms".

However, the archaeologist Audrey Meaney

Audrey Lilian Meaney (19 March 1931 – 14 February 2021) was an archaeologist and historian specialising in the study of Anglo-Saxon England. She published several books on the subject, including ''Gazetteer of Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites'' ...

concluded that there exists "very little undoubted evidence for Anglo-Saxon paganism, and we remain ignorant of many of its essential features of organisation and philosophy". Similarly, the Old English specialist Roy Page expressed the view that the surviving evidence was "too sparse and too scattered" to permit a good understanding of Anglo-Saxon paganism.

Historical development

Arrival and establishment

During most of the fourth century, the majority of Britain had been part of theRoman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, which—starting in 380 AD with the Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholic (term), Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds s ...

—had Christianity as its official religion. However, in Britain, Christianity was probably still a minority religion, restricted largely to the urban centres and their hinterlands. While it did have some impact in the countryside, here it appears that indigenous Late Iron Age polytheistic belief systems continued to be widely practised. Some areas, such as the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

, the majority of Wales (excepting Gwent), Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, and the south-western peninsula, are totally lacking evidence for Christianity in this period.

Britons who found themselves in the areas now dominated by Anglo-Saxon elites possibly embraced the Anglo-Saxons' pagan religion in order to aid their own self-advancement, just as they adopted other trappings of Anglo-Saxon culture. This would have been easier for those Britons who, rather than being Christian, continued to practise indigenous polytheistic belief systems, and in areas this Late Iron Age polytheism could have syncretically mixed with the incoming Anglo-Saxon religion. Conversely, there is weak possible evidence for limited survival of Roman Christianity into the Anglo-Saxon period, such as the place-name ''ecclēs'', meaning 'church', at two locations in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

and Eccles in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. However, Blair suggested that Roman Christianity would not have experienced more than a "ghost-life" in Anglo-Saxon areas. Those Britons who continued to practise Christianity were probably perceived as second-class citizens and were unlikely to have had much of an impact on the pagan kings and aristocracy which was then emphasising Anglo-Saxon culture and defining itself against British culture. If the British Christians were able to convert any of the Anglo-Saxon elite conquerors, it was likely only on a small community scale, with British Christianity having little impact on the later establishment of Anglo-Saxon Christianity in the seventh century.

Prior scholarship tended to view Anglo-Saxon paganism as a development from an older Germanic paganism

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germ ...

. The scholar Michael Bintley cautioned against this approach, noting that this "'Germanic' paganism" had "never had a single ''ur''-form" from which later variants developed.

The conversion to Christianity

Anglo-Saxon paganism only existed for a relatively short time-span, from the fifth to the eighth centuries. Our knowledge of the Christianisation process derives from Christian textual sources, as the pagans were illiterate. Both Latin andogham

Ogham (Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langua ...

inscriptions and the ''Ruin of Britain'' by Gildas

Gildas (Breton: ''Gweltaz''; c. 450/500 – c. 570) — also known as Gildas the Wise or ''Gildas Sapiens'' — was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic ''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'', which recounts ...

suggest that the leading families of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

and other Brittonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

kingdoms had already adopted Christianity in the 6th century. In 596, Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregori ...

ordered a Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to conver ...

to be launched in order to convert the Anglo-Saxons to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The leader of this mission, Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

, probably landed in Thanet Thanet may refer to:

*Isle of Thanet, a former island, now a peninsula, at the most easterly point of Kent, England

*Thanet District, a local government district containing the island

*Thanet College, former name of East Kent College

*Thanet Canal, ...

, then part of the Kingdom of Kent

la, Regnum Cantuariorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the Kentish

, common_name = Kent

, era = Heptarchy

, status = vassal

, status_text =

, government_type = Monarchy ...

, in the summer of 597. While Christianity was initially restricted to Kent, it saw "major and sustained expansion" in the period from c. 625 to 642, when the Kentish king Eadbald sponsored a mission to the Northumbrians led by Paulinus, the Northumbrian king Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

* Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbu ...

invited a Christian mission from Irish monks to establish themselves, and the courts of the East Anglians and the Gewisse were converted by continental missionaries Felix the Burgundian and Birinus the Italian. The next phase of the conversion took place between c.653 and 664, and entailed the Northumbrian sponsored conversion of the rulers of the East Saxons, Middle Anglians, and Mercians. In the final phase of the conversion, which took place during the 670s and 680s, the final two Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to be led by pagan rulers — in Sussex and the Isle of Wight — saw their leaders baptised.

As with other areas of Europe, the conversion to Christianity was facilitated by the aristocracy. These rulers may have felt themselves to be members of a pagan backwater in contrast to the Christian kingdoms in continental Europe. The pace of Christian conversion varied across Anglo-Saxon England, with it taking almost 90 years for the official conversion to succeed. Most of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms returned to paganism for a time after the death of their first converted king. However, by the end of the 680s, all of the Anglo-Saxon peoples were at least nominally Christian.

Blair noted that for most Anglo-Saxons, the "moral and practical imperatives" of following one's lord by converting to Christianity were a "powerful stimulus".

It remains difficult to determine the extent to which pre-Christian beliefs retained their popularity among the Anglo-Saxon populace from the seventh century onward. '' Theodore's Penitential'' and the Laws of Wihtred of Kent

Wihtred ( la, Wihtredus) ( – 23 April 725) was king of Kent from about 690 or 691 until his death. He was a son of Ecgberht I and a brother of Eadric. Wihtred ascended to the throne after a confused period in the 680s, which included a ...

issued in 695 imposed penalties on those who provided offerings to "demons". However, by two or three decades later, Bede could write as if paganism had died out in Anglo-Saxon England. Condemnations of pagan cults also do not appear in other canons from this later period, again suggesting that ecclesiastical figures no longer considered persisting paganism to be a problem.

Scandinavian incursions

In the latter decades of the ninth century during the Late Anglo-Saxon period, Scandinavian settlers arrived in Britain, bringing with them their own, kindred pre-Christian beliefs. No cultic sites used by Scandinavian pagans have been archaeologically identified, although place names suggest some possible examples. For instance,Roseberry Topping

Roseberry Topping is a distinctive hill in North Yorkshire, England. It is situated near Great Ayton and Newton under Roseberry. Its summit has a distinctive half-cone shape with a jagged cliff, which has led to many comparisons with the much h ...

in North Yorkshire was known as Othensberg in the twelfth century, a name which derived from the Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

, or 'Hill of Óðin'. A number of place-names also contain Old Norse references to mythological entities, such as , , and . A number of pendants representing Mjolnir, the hammer of the god Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding æsir, god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology, sacred groves ...

, have also been found in England, reflecting the probability that he was worshipped among the Anglo-Scandinavian

Anglo-Scandinavian is an academic term referring to the hybridisation between Norse and Anglo-Saxon cultures in Britain during the early medieval period. It remains a term and concept often used by historians and archaeologists, and in linguisti ...

population. Jesch argued that, given that there was only evidence for the worship of Odin and Thor in Anglo-Scandinavian England, these might have been the only deities to have been actively venerated by the Scandinavian settlers, even if they were aware of the mythological stories surrounding other Norse gods and goddesses. North however argued that one passage in the Old English rune poem

The Old English rune poem, dated to the 8th or 9th century, has stanzas on 29 Anglo-Saxon runes.

It stands alongside younger rune poems from Scandinavia, which record the names of the 16 Younger Futhark runes.

The poem is a product of the perio ...

, written in the eighth or ninth century, may reflect knowledge of the Scandinavian god Týr

(; Old Norse: , ) is a god in Germanic mythology, a valorous and powerful member of the and patron of warriors and mythological heroes. In Norse mythology, which provides most of the surviving narratives about gods among the Germanic peoples, ...

.

Archaeologically, the introduction of Norse paganism to Britain in this period is mostly visited in the mortuary evidence.

A number of Scandinavian furnished burial styles were also introduced that differed from the Christian churchyard burials then dominant in Late Anglo-Saxon England. Whether these represent clear pagan identity or not is however debated among archaeologists. Norse mythological scenes have also been identified on a number of stone carvings from the period, such as the

Archaeologically, the introduction of Norse paganism to Britain in this period is mostly visited in the mortuary evidence.

A number of Scandinavian furnished burial styles were also introduced that differed from the Christian churchyard burials then dominant in Late Anglo-Saxon England. Whether these represent clear pagan identity or not is however debated among archaeologists. Norse mythological scenes have also been identified on a number of stone carvings from the period, such as the Gosforth Cross

The Gosforth Cross is a large stone monument in St Mary's churchyard at Gosforth in the English county of Cumbria, dating to the first half of the 10th century AD. Formerly part of the kingdom of Northumbria, the area was settled by Scandinavia ...

, which included images of ''Ragnarök

In Norse mythology, (; non, Ragnarǫk) is a series of events, including a great battle, foretelling the death of numerous great figures (including the gods Odin, Thor, Týr, Freyr, Heimdallr, and Loki), natural disasters, and the submers ...

''.

The English church found that it needed to conduct a new conversion process to Christianise the incoming Scandinavian population. It is not well understood how the Christian institutions converted these settlers, in part due to a lack of textual descriptions of this conversion process equivalent to Bede's description of the earlier Anglo-Saxon conversion. However, it appears that the Scandinavian migrants had converted to Christianity within the first few decades of their arrival.

The historian Judith Jesch suggested that these beliefs survived throughout Late Anglo-Saxon England not in the form of an active non-Christian religion, but as "cultural paganism", the acceptance of references to pre-Christian myths in particular cultural contexts within an officially Christian society. Such "cultural paganism" could represent a reference to the cultural heritage of the Scandinavian population rather than their religious heritage. For instance, many Norse mythological themes and motifs are present in the poetry composed for the court of Cnut the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norwa ...

, an eleventh-century Anglo-Scandinavian king who had been baptised into Christianity and who otherwise emphasised his identity as a Christian monarch.

Post-Christianization folklore

Although Christianity had been adopted across Anglo-Saxon England by the late seventh century, many pre-Christian customs continued to be practised. Bintley argued that aspects of Anglo-Saxon paganism served as the foundations for parts of Anglo-Saxon Christianity. Pre-Christian beliefs affected thefolklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

of the Anglo-Saxon period, and through this continued to exert an influence on popular religion

In religious studies and folkloristics, folk religion, popular religion, traditional religion or vernacular religion comprises various forms and expressions of religion that are distinct from the official doctrines and practices of organized rel ...

within the late Anglo-Saxon period. The conversion did not result in the obliteration of pre-Christian traditions, but in various ways created a synthesis of traditions, as exhibited for instance by the Franks Casket

The Franks Casket (or the Auzon Casket) is a small Anglo-Saxon whale's bone (not "whalebone" in the sense of baleen) chest from the early 8th century, now in the British Museum. The casket is densely decorated with knife-cut narrative scenes in ...

, an artwork depicting both the pre-Christian myth of Weland the Smith and the Christian myth of the Adoration of the Magi

The Adoration of the Magi or Adoration of the Kings is the name traditionally given to the subject in the Nativity of Jesus in art in which the three Magi, represented as kings, especially in the West, having found Jesus by following a star, ...

. Blair noted that even in the late eleventh century, "important aspects of lay Christianity were still influenced by traditional indigenous practices".

Both secular and church authorities issued condemnations of alleged non-Christian pagan practices, such as the veneration of wells, trees, and stones, right through to the eleventh century and into the High Middle Ages. However, most of the penitentials

A penitential is a book or set of church rules concerning the Christianity, Christian sacrament of penance, a "new manner of reconciliation with God in Christianity, God" that was first developed by Celtic monks in Ireland in the sixth century A ...

condemning such practices – notably that attributed to Ecgbert of York

Ecgbert (died 19 November 766) was an 8th-century cleric who established the archdiocese of York in 735. In 737, Ecgbert's brother became king of Northumbria and the two siblings worked together on ecclesiastical issues. Ecgbert was a correspond ...

– were largely produced around the year 1000, which may suggest that their prohibitions against non-Christian cultic behaviour may be a response to Norse pagan beliefs brought in by Scandinavian settlers rather than a reference to older Anglo-Saxon practices. Various scholars, among them historical geographer Della Hooke

Della Hooke, (born 1939) is a British historical geographer and academic, who specialises in landscape history and Anglo Saxon England.

On 5 May 1990, she was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London

A fellow is a concept whos ...

and Price, have contrastingly believed that these reflected the continuing practice of veneration at wells and trees at a popular level long after the official Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon society.

Various elements of English folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

from the Medieval period onwards have been interpreted as being survivals from Anglo-Saxon paganism. For instance, writing in the 1720s, Henry Bourne stated his belief that the winter custom of the Yule log

The Yule log, Yule clog, or Christmas block is a specially selected log burnt on a hearth as a winter tradition in regions of Europe, and subsequently North America. The origin of the folk custom is unclear. Like other traditions associated with ...

was a leftover from Anglo-Saxon paganism, however this is an idea that has been disputed by some subsequent research by the likes of historian Ronald Hutton

Ronald Edmund Hutton (born 19 December 1953) is an English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism. He is a professor at the University of Bristol, has written 14 bo ...

, who believe that it was only introduced into England in the seventeenth century by immigrants arriving from Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

. The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance

The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance is an English folk dance dating back to the Middle Ages. The dance takes place each year in Abbots Bromley, a village in Staffordshire, England. The modern version of the dance involves reindeer antlers, a hobby h ...

, which is performed annually in the village of Abbots Bromley

Abbots Bromley is a village and civil parish in the East Staffordshire district of Staffordshire and lies approximately east of Stafford, England. According to the University of Nottingham English Place-names project, the settlement name Abbots ...

in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

, has also been claimed, by some, to be a remnant of Anglo-Saxon paganism. The antlers used in the dance belonged to reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

and have been carbon dated

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

to the eleventh century, and it is therefore believed that they originated in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

and were brought to England some time in the late Mediaeval period, as by that time reindeer were extinct in Britain.

Mythology

Cosmology

Little is known about the cosmological beliefs of Anglo-Saxon paganism. Carver, Sanmark, and Semple suggested that every community within Anglo-Saxon England likely had "its own take on cosmology", although suggested that there might have been "an underlying system" that was widely shared. The later Anglo-Saxon ''Nine Herbs Charm

The "Nine Herbs Charm" is an Old English charm recorded in the tenth-century CEGordon (1962:92–93). Anglo-Saxon medical compilation known as ''Lacnunga'', which survives on the manuscript, Harley MS 585, in the British Library, at London.Macleo ...

'' mentions seven worlds, which may be a reference to an earlier pagan cosmological belief. Similarly, Bede claimed that the Christian king Oswald of Northumbria

Oswald (; c 604 – 5 August 641/642Bede gives the year of Oswald's death as 642, however there is some question as to whether what Bede considered 642 is the same as what would now be considered 642. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology an ...

defeated a pagan rival at a sacred plain or meadow called Heavenfield (), which may be a reference to a pagan belief in a heavenly plain. The Anglo-Saxon concept corresponding to fate

Destiny, sometimes referred to as fate (from Latin ''fatum'' "decree, prediction, destiny, fate"), is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual.

Fate

Although often ...

was , although the "pagan" nature of this conception is subject to some debate; Dorothy Whitelock suggested that it was a belief held only after Christianisation, while Branston maintained that had been an important concept for the pagan Anglo-Saxons. He suggested that it was cognate to the Icelandic term Urdr and thus was connected to the concept of three sisters, the Nornir

The Norns ( non, norn , plural: ) are deities in Norse mythology responsible for Fates, shaping the course of human destinies.''Nordisk familjebok'' (1907)

In the ''Völuspá'', the three primary Norns Urðr (Wyrd), Verðandi, and Skuld draw ...

, who oversee fate in recorded Norse mythology. It is possible that the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons held a belief in an apocalypse that bore similarities with the later Norse myth of Ragnarok.

Although we have no evidence directly testifying to the existence of such a belief, the possibility that the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons believed in a cosmological world tree

The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European religions, Siberian religions, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereb ...

has also been considered. It has been suggested that the idea of a world tree can be discerned through certain references in the ''Dream of the Rood

''The'' ''Dream of the Rood'' is one of the Christian poems in the corpus of Old English literature and an example of the genre of dream poetry. Like most Old English poetry, it is written in alliterative verse. ''Rood'' is from the Old English ...

'' poem. This idea may be bolstered if it is the case, as some scholars have argued, that their concept of a world tree may be derived from a purported common Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

root. The historian Clive Tolley has cautioned that any Anglo-Saxon world tree would likely not be directly comparable to that referenced in Norse textual sources.

Deities

Anglo-Saxon paganism was apolytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

belief system, with its practitioners believing in many deities. However, most Christian Anglo-Saxon writers had little or no interest in the pagan gods, and thus did not discuss them in their texts. The Old English words for a god were and , and they may be reflected in such place-names as Easole ("God's Ridge") in Kent and Eisey ("God's Island") in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

.

The deity for whom we have most evidence is Woden

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered Æsir, god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, v ...

, as "traces of his cult are scattered more widely over the rolling English countryside than those of any other heathen deity". Place names containing or ''Wednes-'' as their first element have been interpreted as references to Woden, and as a result his name is often seen as the basis for such place names as Woodnesborough

Woodnesborough ( ) is a village in the Dover District of Kent, England, west of Sandwich. The population taken at the 2011 census included Coombe as well as Marshborough, and totalled 1,066. There is a Grade II* listed Anglican church dedicate ...

("Woden's Barrow") in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, Wansdyke ("Woden's Dyke") in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, and Wensley ("Woden's Woodland Clearing" or "Woden's Wood") in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

. The name Woden also appears as an ancestor of the royal genealogies of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

and Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

, resulting in suggestions that after losing his status as a god during the Christianisation process he was euhemerised

Euhemerism () is an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that historical accounts become myths as they are exagge ...

as a royal ancestor. Woden also appears as the leader of the Wild Hunt

The Wild Hunt is a folklore motif (Motif E501 in Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature) that occurs in the folklore of various northern European cultures. Wild Hunts typically involve a chase led by a mythological figure escorted by ...

, and he is referred to as a magical healer in the ''Nine Herbs Charm

The "Nine Herbs Charm" is an Old English charm recorded in the tenth-century CEGordon (1962:92–93). Anglo-Saxon medical compilation known as ''Lacnunga'', which survives on the manuscript, Harley MS 585, in the British Library, at London.Macleo ...

'', directly paralleling the role of his continental German counterpart Wodan in the Merseburg Incantations

The Merseburg charms or Merseburg incantations (german: die Merseburger Zaubersprüche) are two medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic pagan belief preserved in the ...

. He is also often interpreted as being cognate with the Norse god Óðinn

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, ...

and the Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old High ...

Uuodan. Additionally, he appears in the Old English ancestor of ''Wednesday'', Ƿōdenesdæġ ( a calque

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language wh ...

from its Latin equivalent, as are the rest of the days of the week

A day is the time period of a full rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours, 1440 minutes, or 86,400 seconds. In everyday life, the word "day" often refers to a solar day, which is the length between two so ...

).

It has been suggested that Woden was also known as Grim – a name which appears in such English place-names as Grimspound

Grimspound is a late Bronze Age settlement, situated on Dartmoor in Devon, England. It consists of a set of 24 hut circles surrounded by a low stone wall. The name was first recorded by the Reverend Richard Polwhele in 1797; it was probably ...

in Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous ...

, Grimes Graves

Grime's Graves is a large Neolithic flint mining complex in Norfolk, England. It lies north east from Brandon, Suffolk in the East of England. It was worked between 2600 and 2300 BC, although production may have continued well int ...

in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

and Grimsby

Grimsby or Great Grimsby is a port town and the administrative centre of North East Lincolnshire, Lincolnshire, England. Grimsby adjoins the town of Cleethorpes directly to the south-east forming a conurbation. Grimsby is north-east of Linco ...

("Grim's Village") in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

– because in recorded Norse mythology, the god Óðinn is also known as Grímnir. Highlighting that there are around twice as many ''Grim'' place-names in England as ''Woden'' place-names, the place-name scholar Margaret Gelling

Margaret Joy Gelling, (''née'' Midgley; 29 November 1924 – 24 April 2009) was an English toponymist, known for her extensive studies of English place-names. She served as President of the English Place-Name Society from 1986 to 1998, and Vi ...

cautioned against the view that ''Grim'' was always associated with Woden in Anglo-Saxon England.

The second most widespread deity from Anglo-Saxon England appears to be the god Thunor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and ...

. It has been suggested that the hammer and the swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

were the god's symbols, representing thunderbolts, and both of these symbols have been found in Anglo-Saxon graves, the latter being common on cremation urns. A large number of Thunor place-names feature the Old English word ''lēah'' ("wood", or "clearing in a wood"), among them Thunderley and Thundersley

Thundersley is a town and former civil parish, now in the unparished area of Benfleet, in the Castle Point borough, in southeast Essex, England. It sits on a clay ridge shared with Basildon and Hadleigh, east of Charing Cross, London. In 1951 ...

in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. The deity's name also appears in other compounds too, as with Thunderfield ("Thunor's Open Land") in Surrey and ''Manston, Kent, Thunores hlaew'' ("Thunor's Mound") in Kent.

A third Anglo-Saxon god that is attested is Tyr, Tiw. In the Anglo-Saxon rune poem, ''Tiwaz rune, Tir'' is identified with the star Polaris rather than with a deity, although it has been suggested that Tiw was probably a war deity. Dunn has suggested that Tiw might have been a supreme creator deity who was nevertheless deemed distant. The name Tiw has been identified in such place-names as Busbridge, Tuesley ("Tiw's Wood or Clearing") in Surrey, Tysoe ("Tiw's Hill-Spur") in Warwickshire, and Alvechurch, Tyesmere ("Tiw's Pool") in Worcestershire. It has been suggested that the "T"-rune which appears on some weapons and crematory urns from the Anglo-Saxon period may be references to Tiw. Also, there is , which in Modern English has become "Tuesday."

Perhaps the most prominent female deity in Anglo-Saxon paganism was Frige (Anglo-Saxon goddess), Frig; however, there is still very little evidence for her worship, although it has been speculated that she was "a goddess of love or festivity". Her name has been suggested as a component of the place-names Frethern in Gloucestershire, and Freefolk, Frobury, and Froyle in Hampshire.

The Saxons, East Saxon royalty claimed lineage from someone known as Seaxnēat, who might have been a god, in part because an Old Saxon baptismal vow calls on the Christian to renounce "Thunaer, Woden and Saxnot". A runic poem mentions a god known as Ingui, Ingwine and the writer Asser mentioned a god known as Gēat. The Christian monk known as the Venerable Bede also mentioned two further goddesses in his written works: Eostre, who was celebrated at a spring festival, and Hretha, whose name meant "glory".

References to idolatry, idols can be found in Anglo-Saxon texts. No Anthropomorphic wooden cult figurines of Central and Northern Europe, wooden carvings of anthropomorphic figures have been found in the area that once encompassed Anglo-Saxon England that are comparable to those found in Scandinavia or continental Europe. It may be that such sculptures were typically made out of wood, which has not survived in the archaeological record. Several anthropomorphic images have been found, mostly in Kent and dated to the first half of the seventh century; however, identifying these with any particular deity has not proven possible. A seated male figure appears on a cremation urn's lid discovered at Spong Hill in Norfolk, which was interpreted as a possible depiction of Woden on a throne. Also found on many crematory urns are a variety of symbols; of these, the swastikas have sometimes been interpreted as symbols associated with Thunor.

Wights

Many Anglo-Saxonists have also assumed that Anglo-Saxon paganism was animism, animistic in basis, believing in a landscape populated by different spirits and other non-human entities, such as elves, Dwarf (folklore), dwarves, and Dragon#Post-classical Germanic, dragons. The English literature scholar Richard North for instance described it as a "natural religion based on animism". Dunn suggested that for Anglo-Saxon pagans, most everyday interactions would not have been with major deities but with such "lesser supernatural beings". She also suggested that these entities might have exhibited similarities with later English beliefs in fairies. Later Anglo-Saxon texts refer to beliefs in (elves), who are depicted as male but who exhibit gender-transgressing and effeminate traits; these may have been a part of older pagan beliefs.Elves seem to have had some place in earlier pre-Christian beliefs, as evidenced by the presence of the Anglo-Saxon language prefix in early given names, such as (elf victory), (elf friend), (elf spear), (elf gift), (elf power) and (modern "Alfred", meaning "elf counsel"), amongst others. Various Old English place names reference (giants) and (dragons). However, such names did not necessarily emerge during the pagan period of early Anglo-Saxon England, but could have developed at a later date.Legend and poetry

In pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon England, legends and other stories were transmitted orally instead of being written down; it is for this reason that very few survive today.

In both ''Beowulf'' and ''Deor's Lament'' there are references to the mythological smith Wayland the Smith, Weyland, and this figure also makes an appearance on the

In pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon England, legends and other stories were transmitted orally instead of being written down; it is for this reason that very few survive today.

In both ''Beowulf'' and ''Deor's Lament'' there are references to the mythological smith Wayland the Smith, Weyland, and this figure also makes an appearance on the Franks Casket

The Franks Casket (or the Auzon Casket) is a small Anglo-Saxon whale's bone (not "whalebone" in the sense of baleen) chest from the early 8th century, now in the British Museum. The casket is densely decorated with knife-cut narrative scenes in ...

. There are moreover two place-names recorded in tenth century charters that include Weyland's name. This entity's mythological stories are better fleshed out in Norse stories.

The only surviving Anglo-Saxon epic poem is the story of ''Beowulf'', known only from a surviving manuscript that was written down by the Christian monk Sepa sometime between the eighth and eleventh centuries AD. The story it tells is set not in England but in Scandinavia, and revolves around a Geatish warrior named Beowulf (hero), Beowulf who travels to Denmark to defeat a monster known as Grendel, who is terrorising the kingdom of Hrothgar, and later, Grendel's Mother as well. Following this, he later becomes the king of Geatland before finally dying in battle with a dragon. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it was commonly believed that ''Beowulf'' was not an Anglo-Saxon pagan tale, but a Scandinavian Christian one; it was not until the influential critical essay ''Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics'' by J. R. R. Tolkien, delivered in 1936, that ''Beowulf'' was established as a quintessentially English poem that, while Christian, looked back on a living memory of paganism. The poem refers to pagan practices such as cremation burials, but also contains repeated mentions of the Christian God and references to tales from Christian mythology, Biblical mythology, such as that of Cain and Abel. Given the restricted nature of literacy in Anglo-Saxon England, it is likely that the author of the poem was a cleric or an associate of the clergy.

Nonetheless, some academics still hold reservations about accepting it as containing information pertaining to Anglo-Saxon paganism, with Patrick Wormald noting that "vast reserves of intellectual energy have been devoted to threshing this poem for grains of authentic pagan belief, but it must be admitted that the harvest has been meagre. The poet may have known that his heroes were pagans, but he did not know much about paganism." Similarly, Christine Fell declared that when it came to paganism, the poet who authored ''Beowulf'' had "little more than a vague awareness of what was done 'in those days'." Conversely, North argued that the poet knew more about paganism that he revealed in the poem, suggesting that this could be seen in some of the language and references.

Cultic practice