The Embanking of the tidal Thames is the historical process by which the lower

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, at one time a broad, shallow waterway winding through

malarious marshlands

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found a ...

, has been transformed into a deep, narrow

tidal

Tidal is the adjectival form of tide.

Tidal may also refer to:

* ''Tidal'' (album), a 1996 album by Fiona Apple

* Tidal (king), a king involved in the Battle of the Vale of Siddim

* TidalCycles, a live coding environment for music

* Tidal (servic ...

canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

. With small beginnings in Roman

Londinium

Londinium, also known as Roman London, was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. It was originally a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around AD 47–50. It sat at a key cross ...

, it was pursued more vigorously in the Middle Ages. Mostly it was achieved by farmers reclaiming marshland and building protective embankments or, in London,

frontagers pushing out into the stream to get more riverfront property. The Victorian civil engineering works in central London, usually called

"the Embankment", are just a small part of the process. Today, over 200 miles of walls line the river's banks from

Teddington

Teddington is a suburb in south-west London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. In 2021, Teddington was named as the best place to live in London by ''The Sunday Times''. Historically in Middlesex, Teddington is situated on a long m ...

down to its mouth in the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

; they defend a tidal

flood plain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

where 1.25 million people work and live. Formerly, it could not be believed that the Thames was embanked by local people so the works were attributed to "the Romans".

It has been argued that land reclamation in the Thames contributed to the decay of the

feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

. Other political consequences were said to be two clauses in

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

, and one of the declared causes of the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. The deepening of the Thames made it navigable by larger ships that could travel further inland: an unforeseen result was the growth of the world's largest port. Much of present-day London is recovered marshland, and considerable parts lie below high water mark. Some London streets originated as tracks running along the wall and yet today, are not even in sight of the river.

The Thames before the walls vs. the river today

In the Roman era

The natural Thames near Roman Londinium was a river flowing through marshland, at some point infested with malarial mosquitos (next section). The original site of London may have been chosen because it was the first place where a broad tract of dry land — chiefly gravel — came down to the stream; the modern

City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

(i.e. the "Square Mile") is built on that gravel. Below, the river flowed to the sea through broad marshes, touching firm ground at just a few points. (It was still so even in the Victorian era, though by then the river was restrained at high tides by earthen banks.) According to James A. Galloway

Thus much of today's urban London is built on reclaimed marshland.

File:Ancient London and marshes.jpg, (Modern riverbed and placenames for comparison)

File:Hadrian bm.jpg, Roman bronze found in Thames

File:1796 Thames marshes.jpg, Thames marshland, London to the North Sea, here shown in a late 18th-century map

Hilda Ormsby — one of the first to write a modern geographical textbook on London — visualised the scene:

where, probably, it was shallow enough to be forded.

Some of those creeks may have been navigable. Of only three Roman ships found in London, one was dug up on the site of

Guy's Hospital

Guy's Hospital is an NHS hospital in the borough of Southwark in central London. It is part of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and one of the institutions that comprise the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre.

...

.

Victorian historians had a theory that the Roman-era Thames practically had no banks, but instead spread out into a vast lagoon at high tide. They used it to argue for the

etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

"London" ← ''Llyndin'' (= "lake fort"). This is now discounted. Further, the central bed of the Thames was in much the same position as it is today. "Notwithstanding that the waterway of the Thames is very irregular, it is clear that it has kept its present line of flow the same, within narrow limits, since it first became estuarine".

More recent research suggests that in Londinium the tide was not large, and at one time non-existent. (See below, ''The advancing head of tide'').

During the Roman occupation the first embankation took place: building a quayside in the London Bridge area (see City of London, below).

Malaria

Malaria was commonplace in the Thames marshes, including London, and was called "

ague" or "marsh fever". While not all agues were caused by malaria, most scholars believe true malaria — the

protozoan infection

Protozoan infections are parasitic diseases caused by organisms formerly classified in the kingdom Protozoa. They are usually contracted by either an insect vector or by contact with an infected substance or surface and include organisms that are ...

— was indeed present. It was mainly transmitted by the mosquito ''

Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described and named by J. W. Meigen in 1818. About 460 species are recognised; while over 100 can transmit human malaria, only 30–40 commonly transmit parasites of the genus ''Plasmodium'', which c ...

atroparvus'', and was frequently lethal.

Possibly malaria was introduced by the Roman invaders; evidence from skeletons suggests the disease was present in Anglo-Saxon England.

It was anyway rife by the 16th century, though the climate (the "

Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

") was colder than today.

James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

and

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

were thought to have died of it, and it was prevalent in London before and after the

Great Fire. Mary Dobson said that

Writing about 1800,

Edward Hasted

Edward Hasted (20 December 1732 OS (31 December 1732 NS) – 14 January 1812) was an English antiquarian and pioneering historian of his ancestral home county of Kent. As such, he was the author of a major county history, ''The History and To ...

notedThe heavy use of

opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

(often consumed as poppy-head tea) and alcohol to fight the fever was commonplace. Later, the disease was combated with

quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg cr ...

; that this treatment was effective tends to confirm it was malaria, and not some unrelated malady. (Another sign was "ague cake": an enlarged

spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes . .)

At

Guy's Hospital

Guy's Hospital is an NHS hospital in the borough of Southwark in central London. It is part of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and one of the institutions that comprise the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre.

...

they frequently received ague cases from the Thames marshes,

William Gull

Sir William Withey Gull, 1st Baronet (31 December 181629 January 1890) was an English physician. Of modest family origins, he established a lucrative private practice and served as Governor of Guy's Hospital, Fullerian Professor of Physiology ...

told the House of Commons in 1854. About a half came from

Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained throu ...

and

Erith

Erith () is an area in south-east London, England, east of Charing Cross. Before the creation of Greater London in 1965, it was in the historical county of Kent. Since 1965 it has formed part of the London Borough of Bexley. It lies nort ...

, but cases also came from

Wapping

Wapping () is a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Wapping's position, on the north bank of the River Thames, has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through its riverside public houses and steps, ...

and

Shadwell

Shadwell is a district of East London, England, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets , east of Charing Cross. It lies on the north bank of the Thames between Wapping (to the west) and Ratcliff (to the east). This riverside location has meant ...

, and along the river from

Bermondsey

Bermondsey () is a district in southeast London, part of the London Borough of Southwark, England, southeast of Charing Cross. To the west of Bermondsey lies Southwark, to the east Rotherhithe and Deptford, to the south Walworth and Peckham, a ...

and

Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

and even

Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

. (At that time it was believed the disease came from breathing bad air — ''mal-aria'' — arising from marshes. Gull recommended the marshes should be drained.)

By the end of the Victorian era indigenous malaria had nearly disappeared from England, but a few cases survived into the 20th century enabling the disease to be positively identified by blood tests. It was caused by the protozoan parasite ''

Plasmodium vivax

''Plasmodium vivax'' is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. This parasite is the most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria. Although it is less virulent than ''Plasmodium falciparum'', the deadliest of the five huma ...

''.

While the draining of the Thames marshes did not, by itself, eradicate malaria — in places the mosquito still abounds — it may have been a contributory cause. Why it did disappear is complex and uncertain.

Today

The tidal Thames today is virtually a canal — in central London, about 250 metres wide — flowing between solid artificial walls, and laterally restrained by these at high tide. For instance, the Victorian engineer

James Walker reported that, if the walls were removed

It seems the continual processes of embanking and bank-raising have greatly increased the

tidal amplitude, which at

London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It r ...

is now 6.6 m (nearly 22 feet), and the constriction and

scouring have deepened the river. Sarah Lavery and Bill Donovan of the

Environment Agency

The Environment Agency (EA) is a non-departmental public body, established in 1996 and sponsored by the United Kingdom government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, with responsibilities relating to the protection and enha ...

warned:

Those are just the walls within the purview of that report, for they do not stop at Sheerness and Shoeburyness.

The Thames Estuary has a defended tidal floodplain of 35,000 hectares (≈135 square miles) with 500,000 properties at risk from flooding. "Other assets within this flood-plain include 400 schools, 16 hospitals, eight power stations, dozens of industrial estates,

the city airport, 30 mainline railway stations and 38 underground and

Docklands Light Railway

The Docklands Light Railway (DLR) is an automated light metro system serving the redeveloped Docklands area of London, England and provides a direct connection between London's two major financial districts, Canary Wharf and the City of Londo ...

stations, with this including most of the central part of

the underground network".

In London the Thames flows through an

alluvial plain

An alluvial plain is a largely flat landform created by the deposition of sediment over a long period of time by one or more rivers coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms. A floodplain is part of the process, being the sma ...

, a geological formation which is two or three miles wide. This plain, the river's natural

flood plain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

, is everywhere less than 25 feet (8 metres) above

Ordnance Datum

In the British Isles, an ordnance datum or OD is a vertical datum used by an ordnance survey as the basis for deriving altitudes on maps. A spot height may be expressed as AOD for "above ordnance datum". Usually mean sea level (MSL) is used fo ...

— sometimes less than 5 feet above. (Very nearly, Ordnance Datum equals

mean sea level

There are several kinds of mean in mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. ...

.)

The walls also affect London's

water table

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with water. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated.

T ...

:

Hence in

borehole

A borehole is a narrow shaft bored in the ground, either vertically or horizontally. A borehole may be constructed for many different purposes, including the extraction of water ( drilled water well and tube well), other liquids (such as petro ...

s,

groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in rock and soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. About 30 percent of all readily available freshwater in the world is groundwater. A unit of rock or an unconsolidate ...

levels in

Battersea Park

Battersea Park is a 200-acre (83-hectare) green space at Battersea in the London Borough of Wandsworth in London. It is situated on the south bank of the River Thames opposite Chelsea and was opened in 1858.

The park occupies marshland reclai ...

were observed to fluctuate with the tide; but just across the river in

Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

, hardly at all. Nearly 7,000 tons of water have to be pumped from the

Circle Line daily to maintain track drainage between

West Kensington

West Kensington, formerly North End, is an area in the ancient parish of Fulham, in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, England, 3.4 miles (5.5 km) west of Charing Cross. It covers most of the London postal area of W14, includin ...

and

Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

stations.

File:London, Wapping -- 2016 -- 4765.jpg, Wapping: warehouses — now flats and a pub — built on the wall

File:2017-Woolwich, Hog Lane reconstructed river stairs & Thames wall 04.jpg, Woolwich: reconstructed wall and stairs

File:Thames foreshore near Ratcliff Cross Stairs.jpg, Limehouse: housing built on the wall

File:River Thames foreshore at London SW8.jpg, Nine Elms: wall near Vauxhall Bridge

''Tributaries''. Where a

tributary

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drainage ...

e.g. the

River Lea

The River Lea ( ) is in South East England. It originates in Bedfordshire, in the Chiltern Hills, and flows southeast through Hertfordshire, along the Essex border and into Greater London, to meet the River Thames at Bow Creek. It is one of t ...

meets the Thames it is necessary to cope with tidal water escaping laterally. This was done, traditionally, by providing the tributary with its own walls. The tributary walls must be carried high enough upstream to meet the rising land. In recent times some tributaries have been given barriers against exceptional tides e.g.

Barking Creek

Barking Creek joins the River Roding to the River Thames. It is fully tidal up to the Barking Barrage (a weir), which impounds a minimum water level through Barking.

In the 1850s, the creek was home to England's largest fishing fleet and a Vic ...

and

Dartford Creek

The Darent is a Kentish tributary of the River Thames and takes the waters of the River Cray as a tributary in the tidal portion of the Darent near Crayford, as illustrated by the adjacent photograph, snapped at high tide. 'Darenth' is frequen ...

.

Who built the walls?

Early speculations

The Thames walls puzzled historians for centuries. Early modern thinkers knew the Thames walls must be old, but could not account for their origins.

The antiquarian Sir

William Dugdale

Sir William Dugdale (12 September 1605 – 10 February 1686) was an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject.

Life

Dugdale was born at Shustoke, near Coleshi ...

amassed a collection of legal records (1662) from which it was evident there were embankments along the Thames from the Middle Ages at least:

The scientist and architect Sir

Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

thought the walls were built to restrain wind-blown

sand dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, fl ...

s, and attributed them to the Romans, for similar reasons. The influential Victorian engineer James Walker — who was himself to lay down the lines of the

Thames Embankment

The Thames Embankment is a work of 19th-century civil engineering that reclaimed marshy land next to the River Thames in central London. It consists of the Victoria Embankment and Chelsea Embankment.

History

There had been a long history of f ...

in central London — thought the same, adding

Walter Besant

Sir Walter Besant (14 August 1836 – 9 June 1901) was an English novelist and historian. William Henry Besant was his brother, and another brother, Frank, was the husband of Annie Besant.

Early life and education

The son of wine merchant Will ...

was intrigued by the mystery. He noticed several small chapels in unpeopled places along the northern wall: he surmised they had been devoted to pray for its preservation.

One of the first writers to reject the "Roman" theory was Robert Peirce Cruden. In his ''History of Gravesend'' (1843) he pointed out that the Roman authorities had no incentive to build embankments on such a scale, nor were any embanked marshlands mentioned in

Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

(1086). He concluded that the Thames embankments between London and

Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Ro ...

were commenced early in the 12th century by

religious houses for the purpose of reclaiming marshland "by easily executed approaches", and were completed in the 13th. Some others including the

Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834.

The post ...

were sceptical too.

How the builders coped with 20 foot tides was not mentioned.

Flaxman Spurrell's explanation

In his ''Early Sites and Embankments on the Margins of the Thames Estuary'' (1885)

F.C.J. Spurrell described his fascination with the topic:-

Spurrell came to realise that large tides in the Thames are a relatively recent phenomenon. In the Middle Ages they were much smaller, where they existed at all. They would have posed no insuperable obstacle to land reclamation by farmers and other local people. It was those people who built the walls. As tides gradually increased over the centuries — which happened because the land was sinking — people easily raised them to match.

Sinking land, rising tide

Spurrell had visited the excavations for the

Royal Albert Dock, the

Port of Tilbury

The Port of Tilbury is a port on the River Thames at Tilbury in Essex, England. It is the principal port for London, as well as being the main United Kingdom port for handling the importation of paper. There are extensive facilities for contai ...

and

Crossness Pumping Station

The Crossness Pumping Station is a former sewage pumping station designed by the Metropolitan Board of Works's chief engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette and architect Charles Henry Driver. It is located at Crossness Sewage Treatment Works, at the ea ...

, and in each place he saw — 7 to 9 feet below the surface — traces of human habitation, including Roman-era pottery. This level was on top of a layer of peat, and was covered by a layer of mud. There were multiple layers of mud and peat. Spurrell thought the mud layers ("tidal clay") must have formed when the

spring tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ca ...

s deposited

sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

(a process still observable in his day at certain river margins, called ''Saltings''). But peat formation must have required a long period of freedom from the tide in order for the vegetation to grow, especially since Estuary peat was often associated with the roots of

yew trees ("the yew is intolerant of water and cannot live in salt").

From these data, and from sightings of fossils like estuarine shells and

diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising sev ...

s, Spurrell proposed that the Thames was a freshwater river originally, but had been invaded by the sea, owing to subsidence of the land.But, he said, the process was not uniform, because sometimes the land subsidence paused — maybe reversed — as was indicated by the peat layers. He thought the

tidal limit

Head of tide, tidal limit or tidehead is the farthest point upstream where a river is affected by tidal fluctuations, or where the fluctuations are less than a certain amount. This applies to rivers which flow into tidal bodies such as oceans, b ...

in Roman times was further down the river. The river was much shallower than today. It was "not too much to suggest that the tidal water, such as now reaches London, might then have been full five-and-twenty miles away". As a later commentator explained, "The Romans did not build the embankments, not because they could not, but because they had no need to".

Spurrell's theory has been described as a "startling suggestion" since shown to be probably correct. "

st modern authorities would agree with Spurrell (I889) that the alluvial plain was an area of marsh dissected by creeks, and that the tidal limit was further seaward than today". (The sinking of the land with respect to sea level is best described as relative, however, since it is a complex of several factors: see The advancing head of tide, below.)

The origins of the walls

As a specimen of his maps, Spurrell published the one shown here. It had a network of walls enclosing reclaimed marshland near

Higham, Kent

Higham is a large village, civil parish and electoral ward in the borough of Gravesham in Kent, England. The village lies just north-west of Strood, in the Medway unitary authority, and south-east of Gravesend. The civil parish had a population ...

. The highest walls were the current tidal defences; progressively lower walls lay inland and were (he said) the old defences. The Thames at high spring tides continued to deposit mud on the Saltings but of course not on the landside areas; these were now lower. This was an instance of land reclamation by successive 'inning' of marshland (see below).

Large amounts of Romano-British pottery could be found in the Kent marshes in Spurrell's day ("I have seen over a hundred unbroken pots at one time, and such immense quantities of broken fragments, that the new embankment of the railway there was in places made of them".) But the levels of human occupation were feet below the present-day marsh:

Towards the end of his life he wrote:

In this waterway grew the largest port in the world.

Later research

John H. Evans writing before the 1953 floods and using data from boreholes and similar sources found that Roman-era human occupation sites were well above the high water levels of the era, hence needed no defensive embankments. But water levels continued to rise; so that (in his words):

* Throughout the Saxon period this land surface was gradually subsiding (or the tide advancing).

* Between A.D. 900 and 1000 the high Spring tide started to overflow over the lower parts of this land surface.

* By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the overflow of the tide reached such frequency and proportions that the first river-walls were erected to exclude it.

* Since that time these river-walls have been constantly heightened and extended, nevertheless, during the whole history of inning down to the present century, inned marshes have been lost to the sea, some permanently.

Spurrell's theory was supported by the

radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

of Thames

microfossil

A microfossil is a fossil that is generally between 0.001 mm and 1 mm in size, the visual study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. A fossil which can be studied with the naked eye or low-powered magnification, ...

s by

Robert Devoy (1979).

Building the walls: incentives and methods

Inning

''Inning'' was a land reclamation process in which riverside marshland was enclosed and drained. Starting from hard ground, typically farmers would build out into the marsh a pair of cross-walls, called ''counter walls''. Then they would complete the gap by building a wall between the ends. The strip of marshland was now enclosed, and could be drained. Such an enclosure was often called a ''hope'', which occasionally survives in English placenames.

Drained marshland was exceptionally fertile, and might be worth two or three times (or even six times) as much as ordinary farmland, since grain could be grown and shipped to London (population 80,000), one of Europe's largest cities. However as the land dried, the peaty soil shrank, lowering the surface well below high water mark, and making it all the more imperative to maintain the wall.

File:Traditional Thames wall.jpg, 1

File:Spurrell tide banks of Thames.jpg, 2

# Traditional Thames wall in Essex obtained by "inning" riverside marshland with (inset) a sluice for draining surface runoff water at low tide

# Mature farmland won by inning, Woolwich to Erith. This map shows another pattern of old, new and cross-walls, probably initiated by the monks of

Lesnes Abbey

Lesnes Abbey is a former abbey, now ruined, in Abbey Wood, in the London Borough of Bexley, southeast London, England. It is a scheduled monument, and the abbey's ruins are listed at Grade II by Historic England. The adjacent Lesnes Abbey W ...

. The old walls having served their purpose are now inland. "The oldest and strongest wall was that on which

Belvedere station stands; it may belong to the XIII century". From Flaxman Spurrell's classic 1885 paper "Early sites and embankments on the margins of the Thames Estuary". Today this land supports substantial towns.

Ditches were dug to drain the enclosed marsh. The water would flow out at low tide through a

sluice

Sluice ( ) is a word for a channel controlled at its head by a movable gate which is called a sluice gate. A sluice gate is traditionally a wood or metal barrier sliding in grooves that are set in the sides of the waterway and can be considered ...

set in the river wall. Also, sluices were essential to allow

surface runoff

Surface runoff (also known as overland flow) is the flow of water occurring on the ground surface when excess rainwater, stormwater, meltwater, or other sources, can no longer sufficiently rapidly infiltrate in the soil. This can occur when th ...

water to escape. Though sluices varied, they were often made from hollowed tree trunks; one design comprised a hinged flap that closed tight when the tide rose. It was important to have a tight seal, for leakage would erode and widen any gap. A storm surge could wash the entire sluice out of the embankment; it was said to be "blown up". Captain Perry said that many inundations came through poorly designed or maintained sluices that blew up.

If the river did break through, the water would flow onto neighbours' lands too, unless the counter walls had been properly kept up. Most disputes between neighbours concerned failure to maintain in good condition the river wall, counter walls, sluices or drainage ditches.

Mature inned farmland had a characteristic pattern like a crazy chequerboard, old walls standing well inland, new walls constituting the river's tidal banks.

As far as the riverfront was concerned, the net result of inning in various places was a series of disparate river walls. In time these were gradually connected to form a continuous wall.

Materials

Traditionally, embankments in the Thames Estuary were made from clay dug out from the marsh, faced with bundles of brushwood or rushes to prevent erosion. Routine maintenance work consumed regular quantities of

coppice

Coppicing is a traditional method of woodland management which exploits the capacity of many species of trees to put out new shoots from their stump or roots if cut down. In a coppiced wood, which is called a copse, young tree stems are repeated ...

wood each year. Sometimes, to anchor them, walls were made from a core of driven stakes and bushes and faced with smooth clay; already in 1281 there is a record of this for Plumstead Marshes.

The height of the walls was increased over time (see below) but this caused problems with stability, slumpage and slipping. Later improvements have included facings of

Kentish ragstone, tightly packed granite or sandstone to reduce erosion from navigational wash; the use of chalk instead of clay; protecting the walls with interlocking concrete blocks; and the use of gently sloping profiles to increase stability and absorb wave energy.

Saltings

Land on the river side of the wall was called the ''saltings'', where spring tides deposited mud. Salting was itself valuable grazing land for sheep. Vegetation in the saltings protected the wall from wave attack; to enhance this protection, local people were sometimes banned from cutting reeds. Saltings — a natural form of flood defence — have now almost disappeared from the Thames owing to human intervention.

Political consequences

Medievalist

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often voc ...

Bryce Lyon

Bryce Dale Lyon (April 22, 1920 – 2007) was a medieval historian who taught at the University of Colorado, Harvard University, the University of Illinois, the University of California at Berkeley and Brown University. By the end of his career, ...

argued that — as in other parts of Northwest Europe e.g. Flanders and Holland — the demand for motivated labour needed for land reclamation in the Thames marshes contributed to the rise of independent farmers and the decay of the feudal system. "This definitely is the case around the estuary of the Thames".

The advancing head of the tide

Today, the River Thames is macro-tidal at

London Bridge

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It r ...

, and is tidal as far upriver as

Teddington Lock

Teddington Lock is a complex of three lock (water transport), locks and a weir on the River Thames between Ham, London, Ham and Teddington in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England. Historically in Middlesex, it was first buil ...

. This was not always so.

In the last 6,000 years (at least) sea level in southeast Great Britain has been rising relative to the land, owing to sinking of the land mass by

compaction,

subaerial erosion, long-term

tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

movement and

isostatic adjustment, as well as

eustatic

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

sea level changes and even human activity.

According to one estimate it has been doing so at an average rate of up to 13–16 cm per century; the rate has not been constant, and there have been temporary reversals. In the Roman period the London alluvial plain was an area of marsh dissected by creeks; the tidal limit may have been as far downriver as

Crossness

Crossness is a location in the London Borough of Bexley, close to the southern bank of the River Thames, to the east of Thamesmead, west of Belvedere and north-west of Erith. The place takes its name from Cross Ness, a specific promontory on the ...

. On that estimate there would have been no tide at London Bridge at all.

Gustav Milne thought there was a small tide at Londinium, falling back to nothing in the late Roman period. Research on this topic continues; it includes dating excavated wharves and

tide mill

A tide mill is a water mill driven by tidal rise and fall. A dam with a sluice is created across a suitable tidal inlet, or a section of river estuary is made into a reservoir. As the tide comes in, it enters the mill pond through a one-way gate ...

s by

dendrochronology

Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the scientific method of dating tree rings (also called growth rings) to the exact year they were formed. As well as dating them, this can give data for dendroclimatology, the study of climate and atmos ...

.

While river-bank dwellers might be prepared to live with occasional storm flooding, tidal high water occurs twice every 25 hours or nearly so. Thus as the tidal head advanced — and the tidal range increased — there would have come a time when the water routinely overflowed or eroded the natural river bank unless artificial banks were made.

At first, low walls sufficed (archaeologists discovered one embankment in north Kent had been only 1.2 metres high). As water levels rose over the centuries the walls were raised. Explained Flaxman Spurell:

In response to storm surges

That keeping up the banks cost "little exertion" may have been true in Spurrell's day, but not in the late Middle Ages. The era 1250–1450 was characterised by a deteriorating climate,

storm surge

A storm surge, storm flood, tidal surge, or storm tide is a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as cyclones. It is measured as the rise in water level above the n ...

s and serious flooding. This topic has been researched by Hilda Grieve and particularly James A. Galloway who have examined the accounts of medieval monasteries and manors.

Storm surges, explained Galloway, are caused by They made for freak high tides in the Thames, especially if coinciding with unusually heavy land flooding (e.g. from a snow melt or a heavy rainstorm).

The river broke through the wall at

Bermondsey

Bermondsey () is a district in southeast London, part of the London Borough of Southwark, England, southeast of Charing Cross. To the west of Bermondsey lies Southwark, to the east Rotherhithe and Deptford, to the south Walworth and Peckham, a ...

(1294);

Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

(1311);

Dagenham

Dagenham () is a town in East London, England, within the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Dagenham is centred east of Charing Cross.

It was historically a rural parish in the Becontree Hundred of Essex, stretching from Hainault Forest ...

, and between

Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

and Woolwich (1320s);

Stepney

Stepney is a district in the East End of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The district is no longer officially defined, and is usually used to refer to a relatively small area. However, for much of its history the place name appl ...

(1323); the North Kent marshes (1328); Southwark (again), between Greenwich and

Plumstead

Plumstead is an area in southeast London, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich, England. It is located east of Woolwich.

History

Until 1965, Plumstead was in the historic counties of England, historic county of Kent and the detail of mu ...

,

Stone, Kent

Stone is a village in the Borough of Dartford in Kent, England. It is located 2.5 miles east of Dartford.

History

Iron Age pottery and artefacts have been found here proving it to be an ancient settlement site. The 13th-century parish church, de ...

(1350s) and Stepney (again) (1369);

Barking

Barking may refer to:

Places

* Barking, London, a town in East London, England

** London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, a local government district covering the town of Barking

** Municipal Borough of Barking, a historical local government dist ...

(1374-5);

Dartford

Dartford is the principal town in the Borough of Dartford, Kent, England. It is located south-east of Central London and

is situated adjacent to the London Borough of Bexley to its west. To its north, across the Thames estuary, is Thurrock in ...

, Erith (1375) and elsewhere. The

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

pandemic killed so many labourers it became harder to keep up the walls. Later, the

dissolution of the monasteries may have caused loss of local expertise with consequent wall breaches that were not repaired for decades e.g. at

Lesnes Abbey

Lesnes Abbey is a former abbey, now ruined, in Abbey Wood, in the London Borough of Bexley, southeast London, England. It is a scheduled monument, and the abbey's ruins are listed at Grade II by Historic England. The adjacent Lesnes Abbey W ...

(Plumstead and Erith).

These were violent incursions of water, not smooth increases. The walls were rebuilt a step higher and stronger, accordingly. Likewise, after the

North Sea flood of 1953

The 1953 North Sea flood was a major flood caused by a heavy storm surge that struck the Netherlands, north-west Belgium, England and Scotland. Most sea defences facing the surge were overwhelmed, causing extensive flooding.

The storm and flo ...

the walls were systematically raised in many places. A height of 18 feet was recommended for agricultural land, more for built up areas. The lines of the existing walls were generally retained, although some new walls were built to dam off creeks.

Quite often, inned lands were abandoned permanently to the river and reverted to salt marsh; they still had value for fishing, willows and reeds (for basket-making, thatching, flooring). "Horse-shoes" are evidence of this. Even on relatively modern maps, "characteristic horse-shoe shaped 'set- backs' reveal where sea or river walls had been breached, and the line of the wall set back around the deep scour hole which had resulted from the movement of water in and out through the narrow gap." Some examples are given below.

Encroachment into the stream

Where human activity beside the river was industrial or commercial there was an incentive not only to make banks but to encroach out into the navigable stream. Here the walls were made by making timber revetments and backfilling with rubbish. The process was repeated over time.

River frontage was valuable property. Passengers and goods were best carried by water, which required river access and landing facilities. River access was convenient for trades that dumped offensive by-products. Other trades that needed river access included barge-building, ship repairing and

lighterage Lightering (also called lighterage) is the process of transferring cargo between vessels of different sizes, usually between a barge (lighter) and a bulker or oil tanker. Lightering is undertaken to reduce a vessel's draft so it can enter port facil ...

. Some retail establishments, such as marine stores and taverns for mariners, benefitted from access to the waterfront.

"As long ago as 1848", wrote Martin Bates, "Sir

William Tite

Sir William Tite (7 February 179820 April 1873) was an English architect who twice served as President of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He was particularly associated with various London buildings, with railway stations and cemetery ...

had deduced that nearly all the land south of

Thames Street in the City of London 'had been gained from the river by a series of strong embankments'." Evidence of such land gain is now commonplace.

Although they have not been investigated very systematically by historians, there were complaints of encroachments into the river. Some said it ought to be illegal; others said it was illegal but law enforcement was slack. One of these,

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. He also involved himself in trying to correct other social injustices. Sharp formulated the plan to settle black ...

, said the City's

water bailiff

A water bailiff is a law-enforcement officer responsible for the policing of bodies of water, such as a river, lake or coast. The position has existed in many jurisdictions throughout history.

Scotland

In Scotland, under the Salmon and Freshwater ...

, who was supposed to stop these encroachments, would turn a blind eye for "Fees and Christmas Compliments".

Wrote

John Ehrman

John Patrick William Ehrman, FBA (17 March 1920 – 15 June 2011) was a British historian, most notable for his three-volume biography of William Pitt the Younger.[Narrow Street

Narrow Street is a narrow road running parallel to the River Thames through the Limehouse area of east London, England. It used to be much narrower, and is the oldest part of Limehouse, with many buildings originating from the eighteenth century ...]

, Limehouse. Archaeologists believe that Narrow Street represents the line of the medieval river wall, which was originally built for 'inning" marshland. But the brick houses are to the river side of the street, and presumably were constructed by encroaching on the river and reclaiming the foreshore; archaeological excavations have tended to confirm this.

Specific instances are given below.

Law and administration

Marsh law

The inhabitants of

Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh is a sparsely populated wetland area in the counties of Kent and East Sussex in the south-east of England. It covers about . The Marsh has been in use for centuries, though its inhabitants commonly suffered from malaria until the ...

in Kent were the first in England to establish amongst themselves customary laws about responsibility for keeping up embankments in a

cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

community. Later the judges applied the "custom of Romney Marsh" in other marshlands; thus it became part of the common law of England, including the Thames. A record shows it was already being applied — in

Little Thurrock

Little Thurrock () is an area, ward, former civil parish and Church of England parish in the town of Grays, in the unitary authority of Thurrock, Essex. In 1931 the parish had a population of 4428.

Location

Little Thurrock is on the north bank ...

— in 1201.

The fundamental principle was that every occupier of land who benefitted from the existence of a wall was obliged to contribute to the effort of keeping it up, and to do so in proportion to the size of his holding. Disputes were adjudicated by 24 ''jurats'' who had sworn to tell the truth and act righteously. A bailiff admonished people to keep up their walls; if they neglected to, he did it himself, and charged them.

Occupiers of down-sloping land that did not benefit from the wall's existence did not have to contribute. (Centuries later, the inhabitants of

Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

were to use that principle to get off paying sewerage rates.) Thus each ''level'' of inned marsh was a separate community or regime.

Because of a controversial interpretation of Magna Carta (next section) the law could not compel people to make new walls, only repair existing ones.

The mutual liability principle applied in cooperative communities only. In ''Hudson v. Tabor'' (1877) the defendant neglected to keep up the height of his wall. There was a very high tide, it overflowed his wall, and the floodwaters ran onto his land — and his neighbour's too, causing damage. The Court of Appeal ruled he was not bound to compensate his neighbour for the loss. This was because there was no pattern of cooperative behaviour by which each person bore his proportionate share of the cost of upkeep: in this district, each frontager looked after his own. By not establishing a cooperative regime the neighbours chose to run the risk.

Marsh law had many aspects about using the common resource for the benefit of all.

Chicago-Kent law professor Fred P. Bosselman argued that marsh law ought to guide decisions of American state courts on wetlands use.

Administration

Sometimes local communities were overwhelmed or defeated e.g. by storm surges, or internal dissensions, and needed help to repair the walls. It was the duty of the king to protect his realm from attacks and this included the violence of the sea. The English kings took to sending out commissions to repair the walls and settle disputes. These commissioners had emergency powers: they could make laws, collect taxes, adjudicate disputes and impress labour.

Their descent on a district could cause resentment, however, especially if they compelled local people to make or pay for new walls. Hence (although this interpretation is controversial)

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

provided:

Because the most important point concerned land drainage, these bodies came to be called ''Commissioners of Sewers''. (A ''sewer'' was simply a rainwater ditch for draining land. The word acquired no "sanitary" connotation until after 1815, when it was first made legal, and then compulsory, to discharge human waste into London's sewers instead of in

cesspits

A cesspit (or cesspool or soak pit in some contexts) is a term with various meanings: it is used to describe either an underground holding tank (sealed at the bottom) or a soak pit (not sealed at the bottom). It can be used for the temporary co ...

. )

An example is

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

, who in 1390 was appointed to a commission sent to survey the walls between Greenwich and Woolwich, and compel landowners to repair them, "showing no favour to rich or poor". The commission had power to sit as Justices according to "the Law of the Marsh". Chaucer while on these duties lived at Greenwich, where he was writing his

Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's ''magnum opus' ...

.

Eventually, the

Statute of Sewers

The Statute of Sewers (23 Hen 8 c. 5) was a 1531 law enacted by the English Reformation Parliament of King Henry VIII. It sought to make the powers of various commissions of sewers permanent, whereas previously, each parliament had to renew their ...

1531 of Henry VIII made these commissions permanent. They existed in all parts of England. In 1844, a legal expert, speaking of the sewers of London, said "the metropolis is at the present moment, in the eye of the law, under the ancient and approved drainage laws of the Marsh of Romney in Kent". The Commissioners continued to exist until 1930; their detailed records are a rich resource for historians.

Some instances

No systematic record of the Thames walls has been kept, except perhaps those of the present day, and they are unpublished. The resources available to the historian are casual and sporadic.

Old maps can reveal the walls (and the essential drainage ditches) but the detail is poor until Joel Gascoyne's

survey of East London of 1703.

Foreshore archaeology, where permitted, has yielded valuable clues, particularly in the City of London, Southwark, Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse. Further upstream the clues may have been obliterated by the Victorian Embankments.

Placenames offer hints e.g.

Bankside

Bankside is an area of London, England, within the London Borough of Southwark. Bankside is located on the southern bank of the River Thames, east of Charing Cross, running from a little west of Blackfriars Bridge to just a short distance befor ...

;

Wapping Wall

Wapping Wall is a street located in the East End of London at Wapping. It runs parallel to the northern bank of the River Thames, with many converted warehouses facing the river.

On this street is the Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, built in ...

; "the name ''Flemingges wall'' in 1311 attests how early foreigners were employed here

rith.

Artworks may be records, especially of West London, though because of

artistic licence

Artistic license (alongside more contextually-specific derivative terms such as poetic license, historical license, dramatic license, and narrative license) refers to deviation from fact or form for artistic purposes. It can include the alterat ...

caution is needed.

Legal records go back far, though not to the time the walls were first built. The science of geology allows an understanding of what was desirable and feasible.

There may never be a comprehensive history of the Thames walls. The following are some instances.

City of London

The City of London's Thames as depicted by 18th-century artists has a generally uniform waterfront with elevated embankments (see illustration). But this was a constriction of the natural river.

From 1973 onwards, said

Gustav Milne,

rescue digs were regularly undertaken along the London waterfront.

In a later paper:

The "mile-long" waterfront was the southern limit of the whole of the City of London and ran from the

Fleet River

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. Its headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath, each of which was dammed into a series of ponds—the Hampstead Ponds and ...

in the west to the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

in the east.

Excavations near London Bridge revealed that waterside encroachment, although starting in the Roman era, advanced mainly between the 11th and 16th centuries: a period of 500–600 years. As well as winning land the probable motive was to keep up the harbour and prevent erosion.

At

Queenhithe

Queenhithe is a small and ancient ward of the City of London, situated by the River Thames and to the south of St. Paul's Cathedral. The Millennium Bridge crosses into the City at Queenhithe.

Queenhithe is also the name of the ancient, but now ...

in the 12th century the embanked area was extended south in five stages by nearly 32 m. According to the site's excavators,

The image of the Tower of London, from an engraving first published 1795, shows its embankment under repair, incidentally revealing it had a hollow, lath-and-plaster structure.

Westminster and Whitehall

In 1342 the walls from around Westminster to

Temple Bar were "broken and in decay by the force of the tides"; a commission was sent to view and repair them. (Then, the

Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

was the river front — as its name implies.) Thereafter these walls seem to have been built more sturdily since no more physical breaches are recorded by Dugdale; however they were sometimes overflowed by abnormally high tides. Since the area is low-lying the floods were notable. In 1235 the tide rose so high that the lawyers were brought out of

Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

in boats. In 1663 —

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

said it was "the greatest tide that ever was remembered" — all

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

was drowned.

File:Hollar Westminster.jpg, 1

File:Westminster Hall edited.jpg, 2

File:Hollar Whitehall.jpg, 3

File:Richard Wilson 1744.jpg, 4

# City of Westminster, 1642. Despite these seemingly robust walls, ultra-high tides went over them (

Wenceslaus Hollar

Wenceslaus Hollar (23 July 1607 – 25 March 1677) was a prolific and accomplished Bohemian graphic artist of the 17th century, who spent much of his life in England. He is known to German speakers as ; and to Czech speakers as . He is particu ...

: Yale Center for British Art)

# Westminster Hall, seat of the higher English law courts, could be flooded chest-deep by those tides (

Thomas Rowlandson

Thomas Rowlandson (; 13 July 175721 April 1827) was an English artist and caricaturist of the Georgian Era, noted for his political satire and social observation. A prolific artist and printmaker, Rowlandson produced both individual social an ...

and

Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

)

# Whitehall c.1650. The whole district was drowned in 1663 (Wenceslaus Hollar: Yale Center for British Art)

# Building Westminster Bridge, 1744. Notice the perfunctory river walls upstream: a diasaster waiting to happen (

Richard Wilson (detail): Tate Britain)

In 1762 a tide flowed into Westminster Hall covering it to a depth of 4 feet. In 1791 a tide overflowed the banks above

Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge is a road-and-foot-traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, linking Westminster on the west side and Lambeth on the east side.

The bridge is painted predominantly green, the same colour as the leather seats in the H ...

:

South Bank

The medieval wall and Lambeth Marsh

A commission was sent to view and repair the banks "betwixt Lambehethe and Grenewiche" in 1295, and again to Lambeth in 1444 — this time to provide for its proper governance "according to the Laws and Customes of Romeney Marsh". Lambeth itself was a marsh.

Present-day walkers along Belvedere Road and its continuation Upper Ground, SE1, cannot see the Thames, yet they are actually following the line of the medieval river wall. Already in the Elizabethan era that wall, called ''Narrow Wall'', no longer fronted the river but stood inland, where it served as a causeway through the marsh. Between Narrow Wall and the Thames there was a wide strip of marshy ground overgrown with rushes and willows; this is shown on Norden's map of 1593. The road continued to be called Narrow Wall until the late Victorian era.

A map of 1682 shows that Lambeth, except for the river front, remained open marsh and pasture ground intersected with many drainage ditches. The land was not developed until Waterloo Bridge was built (1817).

File:Norden 1593 Lambeth Marsh.jpg, 1

File:Lambeth Marsh 1739.jpg, 2

File:Belvedere Rd-Upper Ground.jpg, 3

File:Upper Ground - geograph.org.uk - 490622.jpg, 4

#

Lambeth Marsh

Lambeth Marsh (also Lower Marsh and Lambeth Marshe) is one of the oldest settlements on the South Bank of London, England.

Until the early 19th century much of north Lambeth (now known as the South Bank) was mostly marsh. The settlement of Lam ...

in 1593. The orange strip is the Elizabethan river wall. The white strips are obsolete river walls, by now standing inland, and include Narrow Wall — today Belvedere Road and Upper Ground, SE1. Notice "The sluce". (Map by

John Norden

John Norden (1625) was an English cartographer, chorographer and antiquary. He planned (but did not complete) a series of county maps and accompanying county histories of England, the '' Speculum Britanniae''. He was also a prolific writer ...

, highlighted detail)

# Lambeth Marsh about 1740. The roads served as causeways through the marsh; possibly, all were former river walls or counter-walls. The red arrow denotes Narrow Wall.

# Line of medieval Narrow Wall shown on the modern OpenStreetMap.

# Tour de France cyclists riding it (Upper Ground, SE1).

The wall as a flood defence, or otherwise

The area was always liable to flooding. In 1242 the river overflowed the Lambeth banks "drowning houses and fields for the space of six miles".

"The surface of this area is mostly below the level of high water",

Sir Joseph Bazalgette

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as p ...

told the engineering profession in 1865. The traditional sewers were supposed to discharge into the river, but could do so at low tide only. After heavy rains they backed up for days on end: sewage flooded the basements and accumulated in the streets. The area was wet and "malarious". To relieve this, Bazalgette built his Low Level

nterceptingSewer through the district. Effluent was carried away, not by gravity now, but by steam-powered pumps. He compared the effect of pumping to elevating the whole district by 20 feet.

The

Albert Embankment

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Albert ...

(completed 1868) was not meant to be a flood defence, since it was built on arches to allow vessels to enter

draw dock

A draw dock (also draw-dock) is a creek or inlet in a navigable river bank, sometimes lined, sometimes not, into which boats or barges may be drawn for repair or to land cargoes.Oxford Engkish Dictionary Online, 'Draw-dock'.

Some draw docks, such ...

s, etc. It was up to riverside proprietors to maintain their river walls, but many failed to make them high enough to cope with unusual tides. They said "What is the use of doing it unless their neighbours do it also?", Bazalgette told the House of Commons. The poor, whose houses stood in the low-lying districts behind, suffered most. Bazalgette saw houses where the water had reached six or seven feet above the floor. "The people were driven out of them into the upper floors". For a few thousand pounds this could have been prevented. Bazalgette's

Metropolitan Board of Works

The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was the principal instrument of local government in a wide area of Middlesex, Surrey, and Kent, defined by the Metropolis Management Act 1855, from December 1855 until the establishment of the London County ...

sought legal powers to compel them.

File:Hollar Lambeth Palace.jpg, 1

File:Boydell lambeth.jpg, 2

File:Thames overflow, Lambeth.jpg, 3

File:Lambeth boatbuilders 1853.jpg, 4

File:Pether 1862.jpg, 5

File:Lambeth waterfront c.1860.jpg, 6

File:Lambeth flood refugees.png, 7

#

Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposite ...

in 1647. Then, a fairly low embankment sufficed. (Wenceslaus Hollar: Fisher Hollar Collection, Toronto)

# A glimpse of Lambeth Marsh in 1752 (John Boydell: Yale Center for British Art). ''Caution:'' trees will not grow on recently drained marsh.

# Thames overflow, 1850 near Lambeth Stairs (''Illustrated London News'', 2 February 1850). Lambeth Stairs is shown in images 1 and 5, about where

Lambeth Pier is today.

# Lambeth boatbuilders c.1853. Boatbuilding, an important local industry, did not go well with high river walls. The boats on Searle's slipway are the

Leander Club

Leander Club, founded in 1818, is one of the oldest rowing clubs in the world, and the oldest non-academic club. It is based in Remenham in Berkshire, England and adjoins Henley-on-Thames. Only three other surviving clubs were founded prior to ...

's: it was their headquarters. City livery barge moored at centre. The site is now

St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foun ...

. (Richard John Pembery: Lambeth Archives)

# Foreshore at Lambeth Palace shortly before the Albert Embankment was made (

Henry Pether, 1862, Government Art Collection)

# Lambeth waterfront 1860-5, low tide. Short ladders suffice to surmount dilapidated river wall. (Unknown photographer: Historic England)

# Flood refugees, Lambeth, 1877. The Albert Embankment was not designed for flood protection. At unusually high tides poor people were forced out of their homes. (John Thompson,

Woodburytype

A Woodburytype is both a printing process and the print that it produces. In technical terms, the process is a ''photomechanical'' rather than a ''photographic'' one, because sensitivity to light plays no role in the actual printing. The process ...

process)

Lambeth was badly affected by the

1928 Thames flood

The 1928 Thames flood was a disastrous flood of the River Thames that affected much of riverside London on 7 January 1928, as well as places further downriver. Fourteen people died and thousands were made homeless when floodwaters poured over ...

, people drowning in their basements.

For the

Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

(1951) a large expanse of bomb-damaged riverside property was used to make a new embankment wall and create the

South Bank

The South Bank is an entertainment and commercial district in central London, next to the River Thames opposite the City of Westminster. It forms a narrow strip of riverside land within the London Borough of Lambeth (where it adjoins Alber ...

.

In art: West London

The embanking of the Thames in response to the rising tidal head happened too long ago to be captured in art — in most places. But in West London the tide is comparatively recent and, in parts, small even today. Hence pre-Victorian paintings often depict a river with natural banks. Later, modest erosion defences are made, and gradually join up, as in illustrations 5 and 6. The removal of old London Bridge (1834) increased the tide upstream and caused more flooding in the upper districts. Very few papers have been published about the waterfront riverside communities in this area.

File:Combe Putney Bridge.jpg, 1

File:Bluck 1809.jpg, 2

File:Calcott Richmond Bridge.jpg, 3

File:Cox Millbank.jpg, 4

File:Parrott Putney.jpg, 5

File:Hughes Putney embankment.jpg, 6

# Fulham in 1792, old

Putney Bridge

Putney Bridge is a Grade II listed bridge over the River Thames in west London, linking Putney on the south side with Fulham to the north. The bridge has medieval parish churches beside its abutments: St Mary's Church, Putney is built on the so ...

in distance. Notice the natural river bank — and its erosion. (

Joseph Farington

Joseph Farington (21 November 1747 – 30 December 1821) was an 18th-century English landscape painter and diarist.

Life and work

Born in Leigh, Lancashire, Farington was the second of seven sons of William Farington and Esther Gilbody. His ...

R.A., print)

# Cottage, Battersea, 1809 (John Bluck : Yale Center for British Art)

# Richmond Bridge about 1810 (Sir

Augustus Wall Callcott

Sir Augustus Wall Callcott (20 February 177925 November 1844) was an English landscape painter.

Life and work

Callcott was born at Kensington Gravel Pits, a village on the western edge of London, in the area now known as Notting Hill Gate. ...

R.A.: Yale Center for British Art)

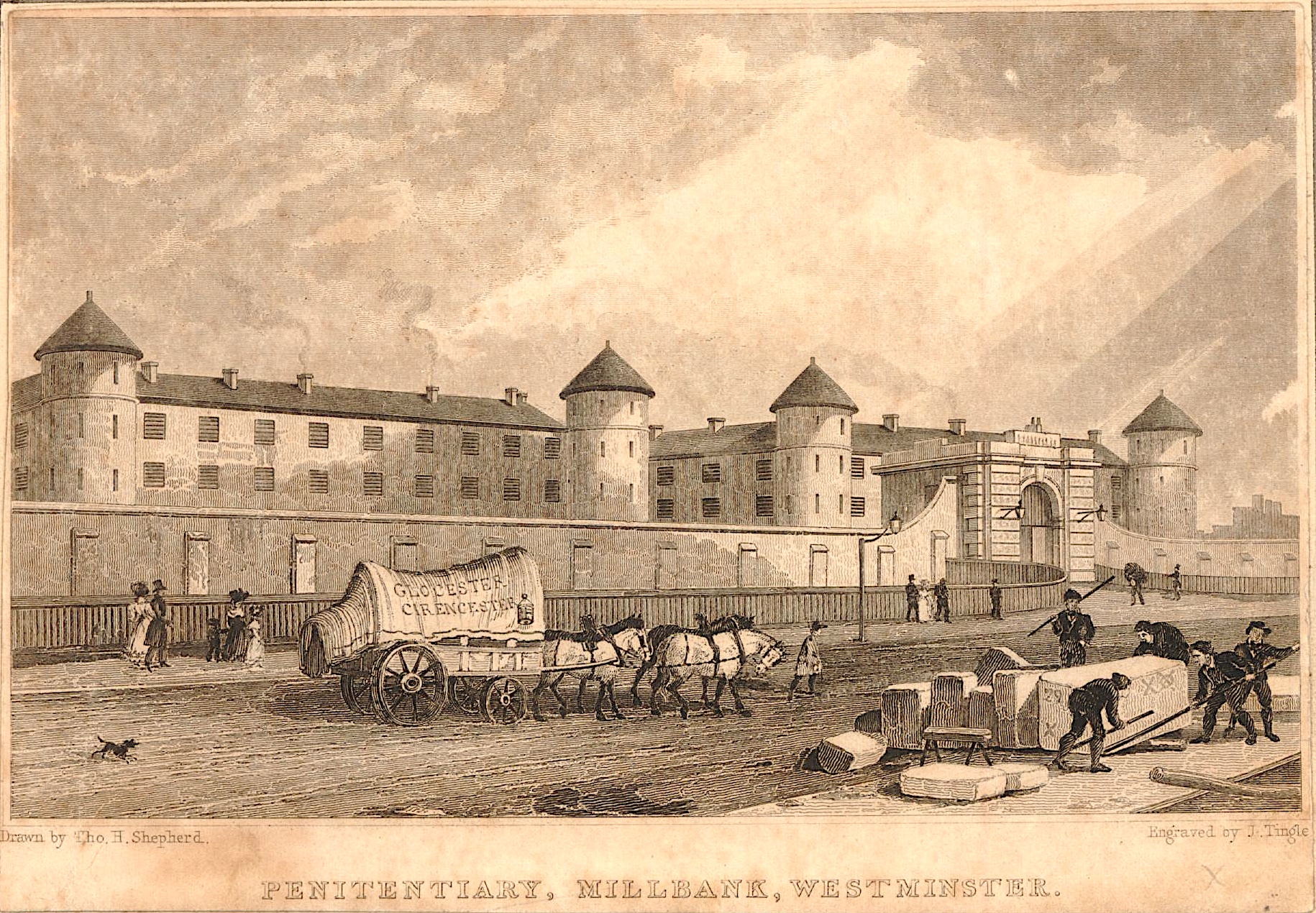

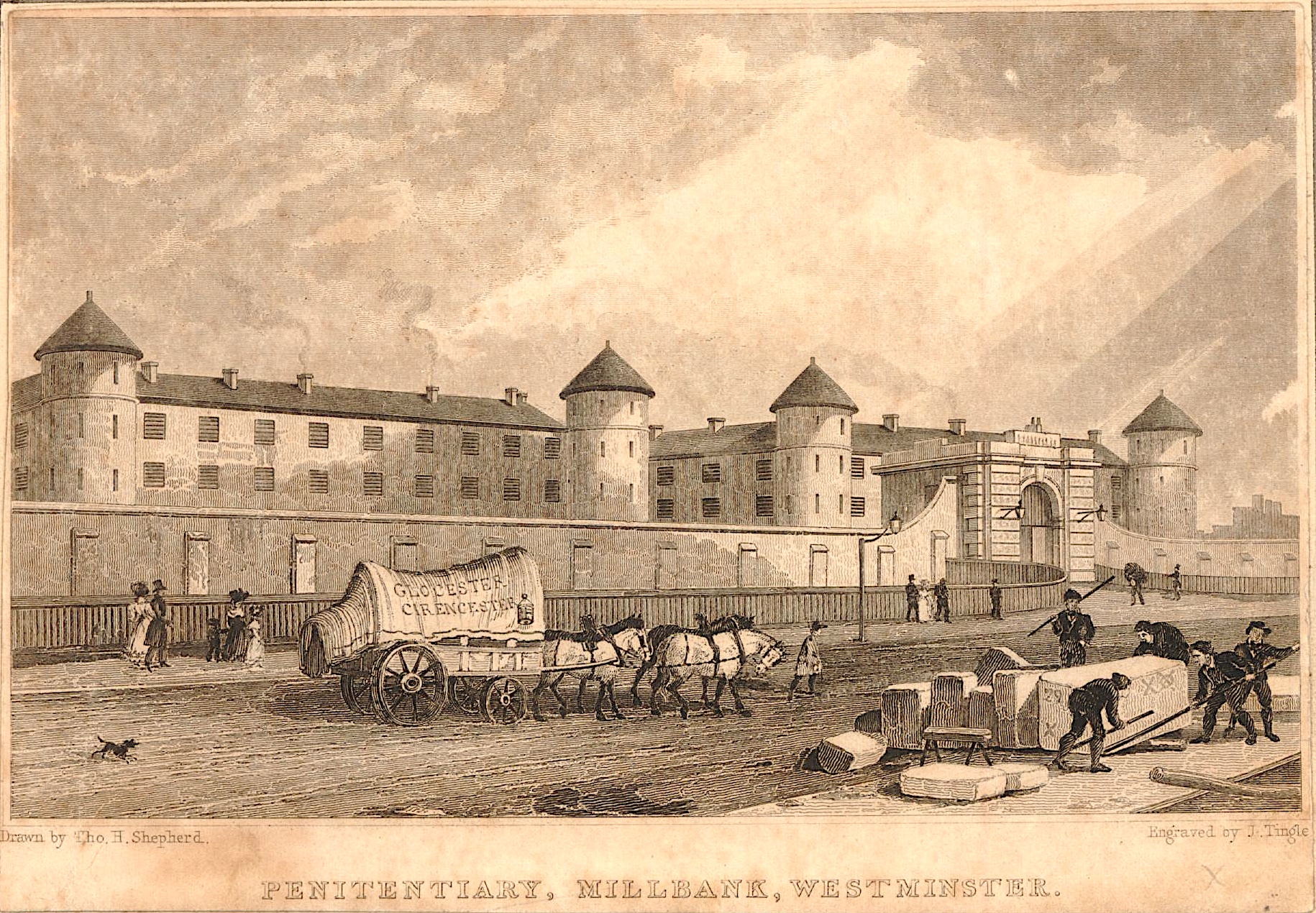

# Millbank 1810 (

David Cox: Yale Center for British Art)

# Putney about 1840. Occasional erosion defences have still not joined up. (William Parrott: Wandsworth Collection)

# Putney about 1880. Now the title is "''The Embankment'', Putney, London". (George Frederick Hughes: Wandsworth Collection)

File:Scott sunset 9 elms.jpg, 1. Nine Elms c.1755

File:The Thames From Millbank.jpg, 2. Millbank, prob. c.1815

File:Pym Battersea Bridge.jpg, 3. Battersea c.1823

File:Heath Cheyne Walk.jpg, 4. Chelsea 1825

File:Byrne Hammersmith.jpg, 5. Hammersmith Bridge 1827

# "A Sunset", woodyard on the left (

Samuel Scott: Tate)

# (

Richard Redgrave

Richard Redgrave (30 April 1804 in Pimlico, London – 14 December 1888 in Kensington, London) was an English landscape artist, genre painter and administrator.

Early life

He was born in Pimlico, London, at 2 Belgrave Terrace, the second son o ...

R.A.: Victoria and Albert Museum)

# "The Old Red House" c.1823 (H. Pymm: YCBA)

# Cheyne Walk looking towards Battersea Bridge, 1825 (

Charles Heath

Charles Theodosius Heath (1 March 1785 – 18 November 1848) was a British engraver, currency and stamp printer, book publisher and illustrator.

Life and career

He was the illegitimate son of James Heath, a successful engraver who enjoyed ...

: YCBA)

# Barnes on the left, Hammersmith on the right (

Letitia Byrne: YCBA)

East London

East of the

Tower

A tower is a tall Nonbuilding structure, structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from guyed mast, masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting ...

were the riverside hamlets of Wapping, Shadwell,

Ratcliff

Ratcliff or Ratcliffe is a locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames between Limehouse (to the east), and Shadwell (to the west). The place name is no longer commonly used.

History

Etymolog ...

and Limehouse, all part of the medieval manor of Stepney. The whole area is flat and low-lying. There was a long history of trying to reclaim the river marsh, defeated by breaches of the river wall caused by abnormal tides.

It was possible to walk from the Tower to Ratcliff along a gravel clifftop overlooking the Thames marsh. This was the

Ratcliff Highway

The Highway, part of which was formerly known as the Ratcliffe Highway, is a road in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London. The route dates back to Roman London, Roman times. In the 19th century it had a reputation for ...

, a route already used in the Roman era. South, however, was "a low-lying swamp flooded daily by the tide and known by the suggestive name 'Wapping in the Wose'", or simply Wapping Marsh or Walmarsh.

This close to London, perhaps the original river walls went back to Saxon times, though there is no record of it. Already in 1325 a jury — asked about the banks and ditches between

St Katharine by the Tower and Shadwell — said they had been made at some remote period in order to inn 100 acres of marsh. Further, an ancient custom of Stepney Manor applied. Tenants had been given land on condition they repaired the walls. Two "wall reeves" were supposed to inspect and admonish slackers. Defaulters could be taken to the

manorial court