Ely S. Parker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ely Samuel Parker (1828 – August 31, 1895), born ''Hasanoanda'' ( Tonawanda Seneca), later known as ''Donehogawa'', was a

University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, pp. 12-14, , accessed 17 February 2011 One of his elder brothers, Nicholson Parker, also became a prominent Seneca leader as he was a powerful

Near the start of the Civil War, Parker tried to raise a regiment of Iroquois volunteers to fight for the Union, but was turned down by

Near the start of the Civil War, Parker tried to raise a regiment of Iroquois volunteers to fight for the Union, but was turned down by  When Ulysses S. Grant became commander of the Military Division of the

When Ulysses S. Grant became commander of the Military Division of the

in JSTOR

* Moses, Daniel. ''The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan'' (University of Missouri Press, 2009) * Parker, Arthur Caswell. ''The Life of General Ely S. Parker'' (1919

online

* Van Steenwyk, Elizabeth. ''Seneca Chief, Army General: A Story about Ely Parker'' (Millbrook Press, 2001) for high schools

online

''The Civil War'', PBS

National Park Service: Ely Parker- A Real American"Ely Parker Scrapbooks

at

Ely Samuel Parker Papers

at

Jacob Riis, "A Dream of the Woods"

*Website for the PBS documentar

(March 10, 2004) {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Ely S. 1828 births 1895 deaths American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Burials at Forest Lawn Cemetery (Buffalo) Grant administration personnel 19th-century Native American politicians Native American United States military personnel Native Americans in the American Civil War People from Galena, Illinois People from Genesee County, New York People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute alumni Seneca people Union Army officers United States Army officers

U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

officer, engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

, and tribal diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

. He was bilingual, speaking both Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, and became friends with Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his theories of social evol ...

, who became a student of the Iroquois in upstate New York. Parker earned an engineering degree in college and worked on the Erie Canal, among other projects.

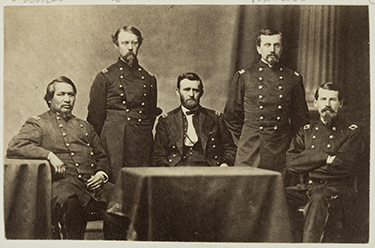

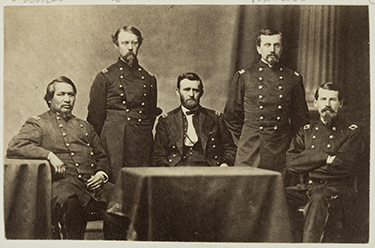

He was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, when he served as adjutant and secretary to General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. He wrote the final draft of the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

surrender terms at Appomattox. Later in his career, Parker rose to the rank of brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

.

When General Grant was elected as US president, he appointed Parker as Commissioner of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal government of the United States, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

, the first Native American to hold that post. (reprinted 2005, )

Early life and education

Ely Parker was born in 1828 as the sixth of seven children to Elizabeth and William Parker atIndian Falls, New York

Indian Falls is a Hamlet (place), hamlet located closely within the northern border of the town of Pembroke, New York, Pembroke and the western edge of Genesee County, New York, Genesee County, Western New York, Western New York (state), New York, ...

(then part of the Tonawanda Reservation

The Tonawanda Indian Reservation ( see, Ta:nöwöde') is an Indian reservation of the Tonawanda Seneca Nation located in western New York, United States. The band is a federally recognized tribe and, in the 2010 census, had 693 people living on t ...

). He was named ''Ha-sa-no-an-da'' and later baptized as Samuel Parker. Both of his parents were of prominent Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

families; while his father was a miller

A miller is a person who operates a Gristmill, mill, a machine to grind a grain (for example corn or wheat) to make flour. Mill (grinding), Milling is among the oldest of human occupations. "Miller", "Milne" and other variants are common surname ...

by trade and a Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

minister, he was also respected as a Tonawanda Seneca chief who had fought for the United States in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. His mother was the granddaughter of ''Sos-he-o-wa'', the successor of the great Haudenosaunee spiritual leader Handsome Lake

Handsome Lake ( Cayuga language: Sganyadái:yo, Seneca language: Sganyodaiyo) (Θkanyatararí•yau• in Tuscarora) (1735 – 10 August 1815) was a Seneca religious leader of the Iroquois people. He was a half-brother to Cornplanter, a Seneca ...

.

His parents strongly supported education for all their children, whose Christian names were Spencer Houghton Cone, Nicholson Henry, Levi, Caroline (Carrie), Newton, and Solomon, all with the surname of Parker.Joy Porter, ''To Be Indian: The Life of Iroquois-Seneca Arthur Caswell Parker''University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, pp. 12-14, , accessed 17 February 2011 One of his elder brothers, Nicholson Parker, also became a prominent Seneca leader as he was a powerful

orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14th ...

, much like the family’s famous relation Red Jacket

Red Jacket (known as ''Otetiani'' in his youth and ''Sagoyewatha'' eeper Awake''Sa-go-ye-wa-tha'' as an adult because of his oratorical skills) (c. 1750–January 20, 1830) was a Seneca people, Seneca orator and Tribal chief, chief of the Wolf ...

had been. Ely had a classical education at a missionary school, and was fully bilingual

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all E ...

, speaking the Seneca language

Seneca (; in Seneca, or ) is the language of the Seneca people, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois League; it is an Iroquoian language, spoken at the time of contact in the western portion of New York. While the name ''Seneca'', attested as ...

as well as English. He also studied in college. He spent his life bridging his identities as Seneca and a resident of the United States.

Beginning in the 1840s, when Ely was a teenager, the Parker home became a meeting place of non-Indian scholars who were interested in the ''Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

'', such as Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his theories of social evol ...

, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft (March 28, 1793 – December 10, 1864) was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist, noted for his early studies of Native American cultures, as well as for his 1832 expedition to the source of the Mississippi R ...

, and John Wesley Powell

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. He ...

. They all played a role in the studies that formed ethnology and anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

as an academic discipline.

As a young man, Parker worked in a legal firm reading law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

for the customary three years with an established firm in Ellicottville, New York

Ellicottville is a town in Cattaraugus County, New York, United States. The population was 1,317 at the 2020 census. The town is named after Joseph Ellicott, principal land agent of the Holland Land Company.

The town of Ellicottville includes ...

before applying to take the bar examination

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associa ...

. He was not permitted to take it because as a Seneca, he was not then considered a United States citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

. All American Indians were not considered citizens until passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, (, enacted June 2, 1924) was an Act of the United States Congress that granted US citizenship to the indigenous peoples of the United States. While the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution ...

, but by that time, some two thirds were American citizens due to other circumstances (military service, etc).

Parker encountered scholar Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his theories of social evol ...

through a chance meeting in a bookstore. At the time Morgan was a young lawyer involved in forming “The Grand Order of the Iroquois”, a fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, "wiktionary:brotherhood, brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club (organization), club or fraternal ...

of young white men from Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

who romanticized their image of the American Indian and wanted to model their group after “Iroquois“ ideals. The two bridged their cultures to become friends, and Parker invited Morgan to visit the Tonawanda reservation

The Tonawanda Indian Reservation ( see, Ta:nöwöde') is an Indian reservation of the Tonawanda Seneca Nation located in western New York, United States. The band is a federally recognized tribe and, in the 2010 census, had 693 people living on t ...

in New York state. Parker became Morgan's main source of information and an entrée to others in the Seneca and other Haudenosaunee nations. Morgan later dedicated his book ''League of the Iroquois'' (1851) to Parker, noting that "the materials are the fruit of our joint researches."Steven Conn, ''History's Shadow: Native Americans and Historical Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century'', Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004, p.210

The relationship proved important for both men; as Parker helped Morgan become an anthropological pioneer, Morgan helped Parker make connections in the larger white-dominated society in which he later worked and lived. With Morgan's help, Parker gained admission to study engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific method, scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad rang ...

at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute () (RPI) is a private research university in Troy, New York, with an additional campus in Hartford, Connecticut. A third campus in Groton, Connecticut closed in 2018. RPI was established in 1824 by Stephen Van ...

in Troy, New York

Troy is a city in the U.S. state of New York and the county seat of Rensselaer County. The city is located on the western edge of Rensselaer County and on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. Troy has close ties to the nearby cities of Albany a ...

.

He worked as a civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

until the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. Parker was later appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

to Commissioner of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal government of the United States, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

, which Morgan had once had ambitions for.

Career

Parker began his career in public service by working as an interpreter and diplomat for the Seneca chiefs in their negotiations with the United States government about land andtreaty rights

In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States the term treaty rights specifically refers to rights for indigenous peoples enumerated in treaties with settler societies that arose from European colonization.

Exactly who is indigenou ...

. In 1852, he was made ''sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Al ...

'' of the Seneca and given the name ''Donehogawa'', "Keeper of the Western Door of the Long House of the Iroquois".Dee Brown, ''Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee''. 1970.

As an engineer, Parker contributed to upgrades and maintenance of the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

, among other projects. As a supervisor of government projects in Galena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in and the county seat of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, with a population of 3,308 at the 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Galena Historic District. The ci ...

, he befriended Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, forming a strong and collegial relationship that was useful later.

Civil War service

Near the start of the Civil War, Parker tried to raise a regiment of Iroquois volunteers to fight for the Union, but was turned down by

Near the start of the Civil War, Parker tried to raise a regiment of Iroquois volunteers to fight for the Union, but was turned down by New York Governor

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has a ...

Edwin D. Morgan

Edwin Denison Morgan (February 8, 1811February 14, 1883) was the 21st governor of New York from 1859 to 1862 and served in the United States Senate from 1863 to 1869. He was the first and longest-serving chairman of the Republican National Comm ...

. He tried to enlist in the Union Army as an engineer, but was told by Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Americ ...

that, as an Indian, he could not join. Parker contacted his colleague and friend Ulysses S. Grant, whose forces suffered from a shortage of engineers. Parker was commissioned a captain in May 1863 and ordered to report to Brig. Gen. John Eugene Smith

John Eugene Smith (1816-1897) was a Swiss immigrant to the United States, who served as a Union general during the American Civil War.

Early life

Smith was born in Bern, Switzerland, in 1816. His father had served under Napoleon Bonaparte and e ...

. Smith appointed Parker as the chief engineer of his 7th Division during the siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Missis ...

, and later said Parker was a "good engineer".

When Ulysses S. Grant became commander of the Military Division of the

When Ulysses S. Grant became commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Parker became his adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

during the Chattanooga Campaign. He was subsequently transferred with Grant as the adjutant of the U.S. Army headquarters and served Grant through the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

. At Petersburg, Parker was appointed as the military secretary to Grant, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He wrote much of Grant's correspondence.

Parker was present when Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865. He helped draft the surrender documents, which are in his handwriting. At the time of surrender, General Lee "stared at me for a moment," said Parker to more than one of his friends and relatives, "He extended his hand and said, 'I am glad to see one real American here.' I shook his hand and said, 'We are all Americans.'” Parker was brevetted brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

of United States Volunteers

United States Volunteers also known as U.S. Volunteers, U.S. Volunteer Army, or other variations of these, were military volunteers called upon during wartime to assist the United States Army but who were separate from both the Regular Army and the ...

on April 9, 1865, and of United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

March 2, 1867.

Post-Civil War

After the Civil War, Parker was commissioned as an officer in the 2nd United States Cavalry on July 1, 1866. He again became the military secretary to Grant, with the rank of colonel, as Grant completed his appointment as commanding general of the U.S. Army. Parker was a member of the Southern Treaty Commission, which renegotiated treaties with tribes who had sided with the Confederacy, were mostly from the Southeast, and now lived inIndian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

. On April 26, 1869, Parker resigned from the army with the rank of brevet brigadier general of the regular army.

He was elected a Veteran Companion of the New York Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or simply the Loyal Legion is a United States patriotic order, organized April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Army. The original membership was composed of members ...

, a military society of officers of the Union armed forces and their descendants.

Personal life

After the war, in 1867 Parker married Minnie Orton Sackett (1849–1932). They had one daughter, Maud Theresa Parker (1878–1956).Appointment under Grant

Shortly after Grant took office as president in March 1869, he appointed Parker asCommissioner of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal government of the United States, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

. He was the first Native American to hold the office. Parker became the chief architect of President Grant's Peace Policy in relation to the Native Americans in the West. Under his leadership, the number of military actions against Indians were reduced, and there was an effort to support tribes in their transition to lives on reservations. In 1871, however, a disaffected former Commissioner of Indian Affairs named William Welsh accused Parker of corruption. Although Parker was cleared of any significant wrongdoing by the House Committee on Appropriations

The United States House Committee on Appropriations is a List of current United States House of Representatives committees, committee of the United States House of Representatives that is responsible for passing Appropriations bill (United State ...

, his position was stripped of much of its power and he resigned in 1871.

Post Commissioner of Indian Affairs

After leaving government service, Parker invested in the stock market. At first he did well, but eventually he lost the fortune he had accumulated, after thePanic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

.

Through his social connections, Parker received an appointment to the Board of Commissioners of the New York Police Department's Committee on Supplies and Repairs. Parker received many visits at Police Headquarters on Mulberry Street from Jacob Riis

Jacob August Riis ( ; May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914) was a Danish-American social reformer, "muckraking" journalist and social documentary photographer. He contributed significantly to the cause of urban reform in America at the turn of the twen ...

, the photographer famous for documenting the lives of slum dwellers.

Later life, death, and reinterment

Parker lived his last years in poverty, dying inFairfield, Connecticut

Fairfield is a town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. It borders the city of Bridgeport and towns of Trumbull, Easton, Weston, and Westport along the Gold Coast of Connecticut. Located within the New York metropolitan area ...

on August 31, 1895. He was buried, but the Seneca did not believe that this Algonquian territory was appropriate for his final resting place. They requested that his widow relocate his body. On January 20, 1897, his body was exhumed and reinterred at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

. He was reinterred next to his ancestor Red Jacket

Red Jacket (known as ''Otetiani'' in his youth and ''Sagoyewatha'' eeper Awake''Sa-go-ye-wa-tha'' as an adult because of his oratorical skills) (c. 1750–January 20, 1830) was a Seneca people, Seneca orator and Tribal chief, chief of the Wolf ...

, a famous Seneca orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14th ...

, and other notables of Western New York

Western New York (WNY) is the westernmost region of the U.S. state of New York. The eastern boundary of the region is not consistently defined by state agencies or those who call themselves "Western New Yorkers". Almost all sources agree WNY in ...

.

Legacy

*Ely S. Parker Building of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Reston, Virginia *Parker's career and influence on contemporary Native Americans is described in Chapter 8 of Dee Brown's ''Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

''Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West'' is a 1970 non-fiction book by American writer Dee Brown that covers the history of Native Americans in the American West in the late nineteenth century. The book expres ...

''.

*He is said to have helped found the town of Parker, Arizona

Parker ( Mojave 'Amat Kuhwely, formerly 'Ahwe Nyava) is the county seat of La Paz County, Arizona, United States, on the Colorado River in Parker Valley. The population was 3,083 at the 2010 census.

History

Founded in 1908, the town was named a ...

. Another individual with the surname of Parker is credited with this distinction as well. The Arizona Republic, dated April 29, 1871 indicates that the new post office was named after “Ely Parker”.

*Parker is honored on the reverse of the 2022 Sacagawea dollar coin.

In popular culture

*Jacob Riis

Jacob August Riis ( ; May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914) was a Danish-American social reformer, "muckraking" journalist and social documentary photographer. He contributed significantly to the cause of urban reform in America at the turn of the twen ...

featured Parker as a character in a short story, "A Dream of the Woods," about a Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

*Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

*Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been t ...

woman and her child stranded in Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central Terminal (GCT; also referred to as Grand Central Station or simply as Grand Central) is a commuter rail terminal located at 42nd Street and Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Grand Central is the southern terminus ...

.

* Asa-Luke Twocrow plays Ely Parker in the film ''Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

'' (2012), directed by Steven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Spie ...

.

*Gregory Sierra

Gregory Joseph Sierra (January 25, 1937 – January 4, 2021) was an American actor known for his roles as Detective Sergeant Chano Amengual on ''Barney Miller'', Julio Fuentes, the Puerto Rican neighbor of Fred G. Sanford on ''Sanford and Son'' ...

plays him in Season 3, Episode 7 of the American TV series '' Dr. Quinn: Medicine Woman''.

*Parker is featured as a character in the novels ''Grant Comes East

''Grant Comes East: A Novel of the Civil War'' (2004) is an alternate history novel written by Newt Gingrich, former Speaker of the United States House of Representatives; William R. Forstchen, and Albert S. Hanser, and the second of a trilogy. I ...

'' and '' Never Call Retreat.''

*Parker is featured in season 2 of the podcast drama ''1865''.

See also

*''Fellows v. Blacksmith

''Fellows v. Blacksmith'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 366 (1857), is a United States Supreme Court decision involving Native American law. John Blacksmith, a Tonawanda Seneca, sued agents of the Ogden Land Company for common law claims of trespass, assa ...

'' Parker acting as plaintiff for Blacksmith's estate before the United States Supreme Court

*Arthur C. Parker

Arthur Caswell Parker (April 5, 1881 – January 1, 1955) was an American archaeologist, historian, folklorist, museologist and noted authority on Native American culture. Of Seneca and Scots-English descent, he was director of the Roc ...

, Nephew and biographer of Ely Parker

Notes

Further reading

* Armstrong, William H. ''Warrior in Two Camps''. (Syracuse University Press, 1978) . * Bruchac, Joseph. ''Walking Two Worlds..'' (7th Generation, 2015) . Biography for young adults. * Michaelsen, Scott. "Ely S. Parker and Amerindian Voices in Ethnography." ''American Literary History'' 8.4 (1996): 615–638in JSTOR

* Moses, Daniel. ''The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan'' (University of Missouri Press, 2009) * Parker, Arthur Caswell. ''The Life of General Ely S. Parker'' (1919

online

* Van Steenwyk, Elizabeth. ''Seneca Chief, Army General: A Story about Ely Parker'' (Millbrook Press, 2001) for high schools

online

External links

''The Civil War'', PBS

National Park Service: Ely Parker- A Real American"

at

Newberry Library

The Newberry Library is an independent research library, specializing in the humanities and located on Washington Square in Chicago, Illinois. It has been free and open to the public since 1887. Its collections encompass a variety of topics rela ...

Ely Samuel Parker Papers

at

Newberry Library

The Newberry Library is an independent research library, specializing in the humanities and located on Washington Square in Chicago, Illinois. It has been free and open to the public since 1887. Its collections encompass a variety of topics rela ...

*Jacob Riis, "A Dream of the Woods"

*Website for the PBS documentar

(March 10, 2004) {{DEFAULTSORT:Parker, Ely S. 1828 births 1895 deaths American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law Burials at Forest Lawn Cemetery (Buffalo) Grant administration personnel 19th-century Native American politicians Native American United States military personnel Native Americans in the American Civil War People from Galena, Illinois People from Genesee County, New York People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute alumni Seneca people Union Army officers United States Army officers