Elucidarium on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Elucidarium'' (also ''Elucidarius'', so called because it "elucidates the obscurity of various things") is an encyclopedic work or ''

''Elucidarium'' (also ''Elucidarius'', so called because it "elucidates the obscurity of various things") is an encyclopedic work or ''

; Late Middle Ages * A Late Middle English translation of the fourteenth-century French, ''Second Lucidaire'' called The Lucidary * A Provençal translatio

* A

The Elucidarium and other tracts in Welsh from Llyvyr agkyr Llandewivrevi A.D. 1346 (Jesus college ms. 119)

' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894) * A fifteenth-century Czech translatio

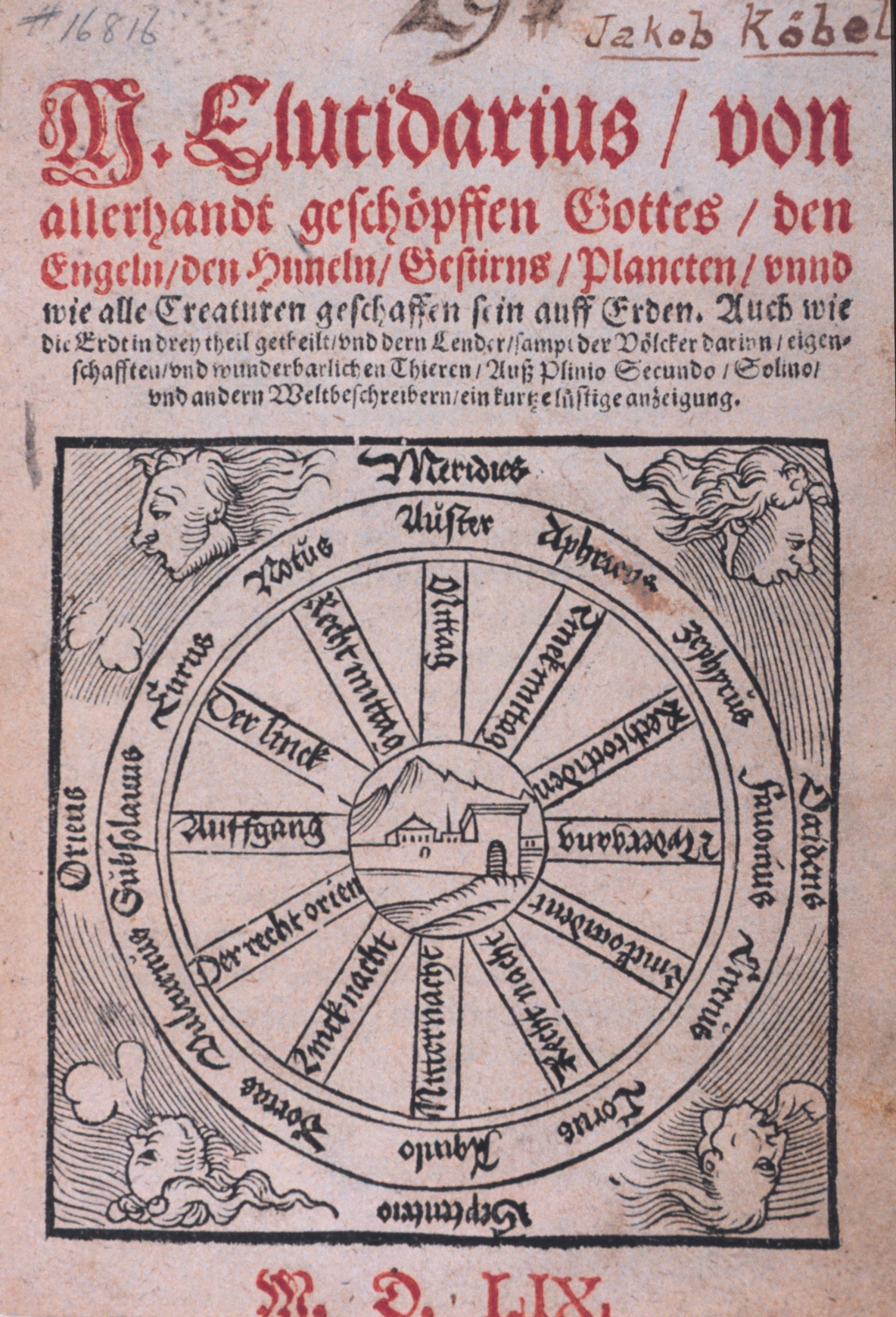

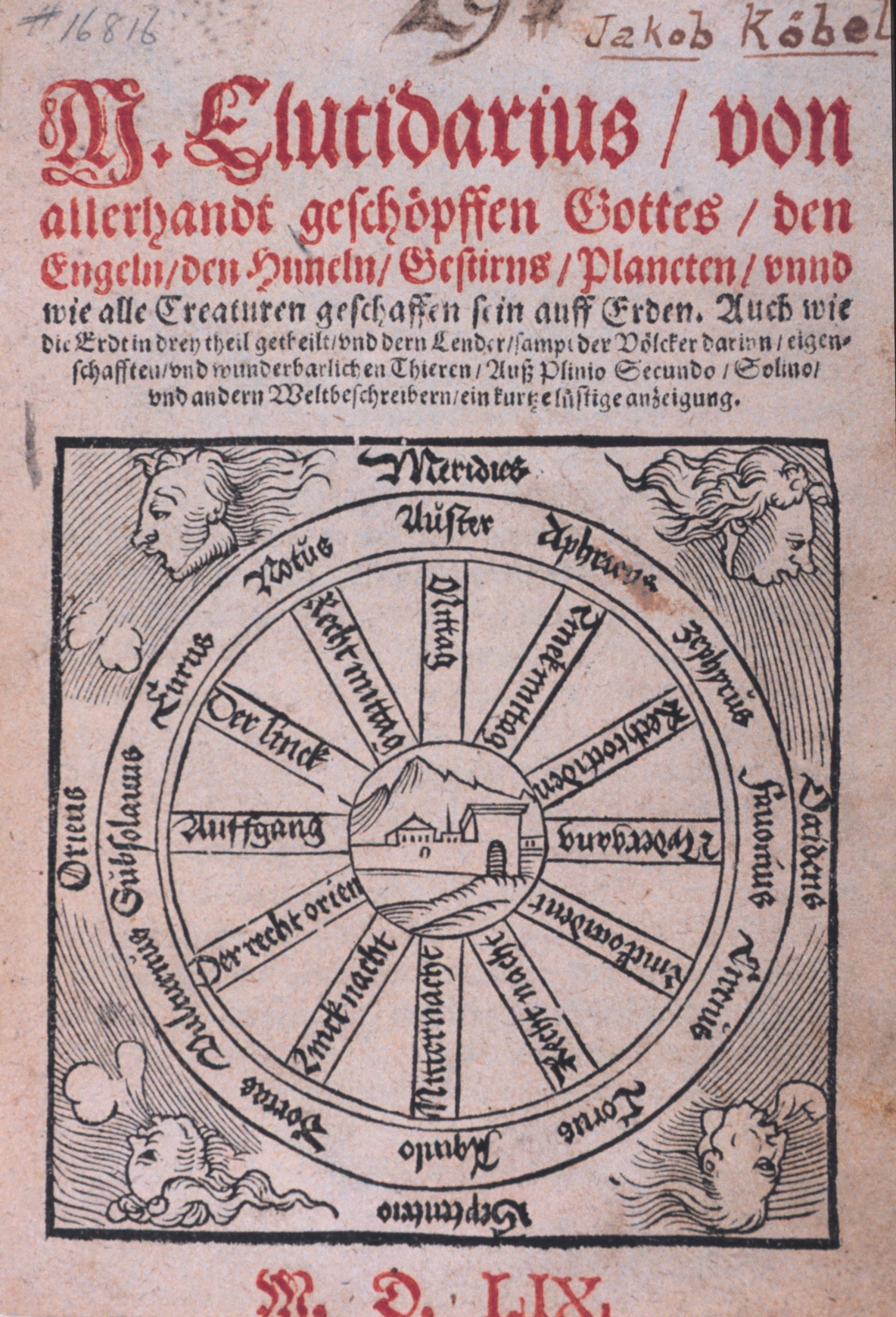

; Sixteenth century * Nuremberg, 150

* Nuremberg, 151

* Landshut, 151

* Vienna, 151

* Hermannus Torrentinus, ''Dictionarivm poeticvm qvod vvlgo inscribitur Elucidarius carminum, apvd Michaellem Hillenium'', 153

''Elucidarius poeticus : fabulis et historiis refertissimus, iam denuo in lucem, cum libello d. Pyrckheimeri de propriis nominibus civitatum, arcium, montium, aeditus, Imprint Basileae : per Nicolaum Bryling.'', 154

* ''Eyn newer M. Elucidarius'', Strasbourg 153

''Elucidarium'' (also ''Elucidarius'', so called because it "elucidates the obscurity of various things") is an encyclopedic work or ''

''Elucidarium'' (also ''Elucidarius'', so called because it "elucidates the obscurity of various things") is an encyclopedic work or ''summa

Summa and its diminutive summula (plural ''summae'' and ''summulae'', respectively) was a medieval didactics literary genre written in Latin, born during the 12th century, and popularized in 13th century Europe. In its simplest sense, they might ...

'' about medieval Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theology, theologian ...

and folk belief

In folkloristics, folk belief or folk-belief is a broad genre of folklore that is often expressed in narratives, customs, rituals, foodways, proverbs, and rhymes. It also includes a wide variety of behaviors, expressions, and beliefs. Examples of c ...

, originally written in the late 11th century by Honorius Augustodunensis

Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1080 – c. 1140), commonly known as Honorius of Autun, was a very popular 12th-century Christian theologian who wrote prolifically on many subjects. He wrote in a non-scholastic manner, with a lively style, and his wor ...

, influenced by Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury, OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also called ( it, Anselmo d'Aosta, link=no) after his birthplace and (french: Anselme du Bec, link=no) after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of th ...

and John Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena, also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena, John the Scot, or John the Irish-born ( – c. 877) was an Irish Neoplatonist philosopher, theologian and poet of the Early Middle Ages. Bertrand Russell dubbed him "the most ...

. It was probably complete by 1098, as the latest work by Anselm that finds mention is ''Cur deus homo''. This suggests that it is the earliest work by Honorius, written when he was a young man. It was intended as a handbook for the lower and less educated clergy. Valerie Flint

Valerie Irene Jane Flint (5 July 1936 – 7 January 2009) was a British scholar and historian, specialising in medieval intellectual and cultural history.

Biography

Early life

Flint was born in Derby. She was a pupil at the Rutland Ho ...

(1975) associates its compilation with the 11th-century Reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill#The Yorkshire Associati ...

of English monasticism.

Overview

The work is set in the form of aSocratic dialogue

Socratic dialogue ( grc, Σωκρατικὸς λόγος) is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the p ...

between a disciple and his teacher, divided in three books. The first discusses God, the creation of angels and their fall, the creation of man and his fall and need for redemption, and the earthly life of Christ. The second book discusses the divine nature of Christ and the foundation of the Church at Pentecost, understood as the mystical body of Christ manifested in the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

dispensed by the Church. The third book discusses Christian eschatology

Christian eschatology, a major branch of study within Christian theology, deals with "last things". Such eschatology – the word derives from two Greek roots meaning "last" () and "study" (-) – involves the study of "end things", whether of ...

. Honorius embraces this last topic with enthusiasm, with the Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, the Antichrist refers to people prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus Christ and substitute themselves in Christ's place before the Second Coming. The term Antichrist (including one plural form) 1 John ; . 2 John . ...

, the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

, the Last Judgement

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

, Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

, the pains of Hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell ...

and the joys of Heaven

Heaven or the heavens, is a common religious cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or reside. According to the belie ...

described in vivid detail.

The work was very popular from the time of its composition and remained so until the end of the medieval period. The work survives in more than 300 manuscripts of the Latin text (Flint 1995, p. 162). The theological topic is embellished with many loans from the native folklore of England, and was embellished further in later editions and vernacular translations. Written in the 1090s in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, it was translated into late Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

within a few years of its completion (Southern 1991, p. 37). It was frequently translated into vernaculars and survives in numerous disparate versions, from the 16th century also in print in the form of popular chapbook

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered bookle ...

s. Later versions attributed the work to a "Master Elucidarius". A Provençal translation revises the text for compatibility with Catharism

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Follow ...

. An important early translation is that into Old Icelandic

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

, dated to the late 12th century. The Old Icelandic translation survives in fragments in a manuscript dated to c. 1200 (AM 674 a 4to), one of the very earliest surviving Icelandic manuscripts. This ''Old Icelandic Elucidarius'' was an important influence on medieval Icelandic literature and culture, including the Snorra Edda

The ''Prose Edda'', also known as the ''Younger Edda'', ''Snorri's Edda'' ( is, Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as ''Edda'', is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been t ...

.

The ''editio princeps In classical scholarship, the ''editio princeps'' (plural: ''editiones principes'') of a work is the first printed edition of the work, that previously had existed only in manuscripts, which could be circulated only after being copied by hand.

For ...

'' of the Latin text is that of the Patrologia Latina

The ''Patrologia Latina'' (Latin for ''The Latin Patrology'') is an enormous collection of the writings of the Church Fathers and other ecclesiastical writers published by Jacques-Paul Migne between 1841 and 1855, with indices published between ...

, vol. 172 (Paris 1895).

Editions and translations

Modern editions and translations

* Lefèvre, Yves, ''L'Elucidarium et les Lucidaires'', Bibliothèque des écoles Françaises d’Athènes et de Rome, 180 (Paris, 1954) (Latin with modern French translation)Medieval translations

; High Middle Ages * AnOld Icelandic

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

version of ca. 1200.Magnús Eiríksson

:''Magnús Eiríksson was also the Old Norse name of Magnus IV of Sweden.''

Magnús Eiríksson (22 June 1806 in Skinnalón (Norður-Þingeyjarsýsla), Iceland – 3 July 1881 in Copenhagen, Denmark) was an Icelandic theologian and a contemporary ...

, "Brudstykker af den islandske Elucidarius," in: ''Annaler for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie'', Copenhagen 1857, pp. 238–308.

**Ed. Evelyn Scherabon Firchow and Kaaren Grimstad, ''Elucidarius: in Old Norse translation'', Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi 36 (Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússonar, 1989).

* A thirteenth-century translation into Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

by the Dominican Jeffrey of Waterford

* A thirteenth-century translation into Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. High ...

, followed by a German-language ms. tradition of the 13th to 15th centurie; Late Middle Ages * A Late Middle English translation of the fourteenth-century French, ''Second Lucidaire'' called The Lucidary * A Provençal translatio

* A

Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh ( cy, Cymraeg Canol, wlm, Kymraec) is the label attached to the Welsh language of the 12th to 15th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This form of Welsh developed directly from Old Welsh ( cy, Hen G ...

version from the ''Llyvyr agkyr Llandewivrevi'' (Jesus college ms. 119, 1346)

**Ed. J. Morris Jones and John Rhŷs, The Elucidarium and other tracts in Welsh from Llyvyr agkyr Llandewivrevi A.D. 1346 (Jesus college ms. 119)

' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1894) * A fifteenth-century Czech translatio

; Sixteenth century * Nuremberg, 150

* Nuremberg, 151

* Landshut, 151

* Vienna, 151

* Hermannus Torrentinus, ''Dictionarivm poeticvm qvod vvlgo inscribitur Elucidarius carminum, apvd Michaellem Hillenium'', 153

''Elucidarius poeticus : fabulis et historiis refertissimus, iam denuo in lucem, cum libello d. Pyrckheimeri de propriis nominibus civitatum, arcium, montium, aeditus, Imprint Basileae : per Nicolaum Bryling.'', 154

* ''Eyn newer M. Elucidarius'', Strasbourg 153

References

* Valerie I. J. Flint, ''The Elucidarius of Honorius Augustodunensis and Reform in Late Eleventh-Century England'', in: Revue bénédictine 85 (1975), 178–189. * Marcia L. Colish, ''Peter Lombard, Volume 1'', vol. 41 of Brill's studies in intellectual history (1994), , 37–42. * Th. Ricklin, "Elucidarium"; in: Eckert, Michael; Herms, Eilert; Hilberath, Bernd Jochen; Jüngel, Eberhard eds.): ''Lexikon der theologischen Werke'', Stuttgart 2003, 263/264. * Gerhard Müller, ''Theologische Realenzyklopädie'', Walter de Gruyter, 1993, , p. 572. {{Authority control 1090s books Christian apocalyptic writings Christian theology books Christian folklore European folklore 11th-century Latin books