Elliott Fitch Shepard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elliott Fitch Shepard (July 25, 1833 – March 24, 1893) was a New York lawyer, banker, and owner of the ''

Shepard was born July 25, 1833, in Jamestown in

Shepard was born July 25, 1833, in Jamestown in

In 1864, Shepard was a member of the executive committee and chair of the Committee on Contributions from Without the City for the New York Metropolitan Fair. He chaired lawyers' committees for disaster relief, including those in

In 1864, Shepard was a member of the executive committee and chair of the Committee on Contributions from Without the City for the New York Metropolitan Fair. He chaired lawyers' committees for disaster relief, including those in

Shepard and Margaret had five daughters and one son: Florence (1869–1869), Maria Louise (1870–1948), Edith (1872–1954), Marguerite (1873–1895),

Shepard and Margaret had five daughters and one son: Florence (1869–1869), Maria Louise (1870–1948), Edith (1872–1954), Marguerite (1873–1895),

In 1892, the City University of New York gave Shepard a

In 1892, the City University of New York gave Shepard a

At the funeral, organizations that Shepard was part of sent representatives, including the Union League Club, the Republican County Committee, the Republican Club, the New York State Bar Association, the Presbyterian Union, the Chamber of Commerce, the American Sabbath Union, New York Sabbath Observance Committee, American Bible Society, St. Paul's Institute at Tarsus, the Union League of Brooklyn, the Republican Association of the 21st Assembly District, the Shepard Rifles, the New York Typothetae, the American Bank Note Company, the College of the City of New York, the ''Mail and Express'', and the New-York Press Club. Those at the funeral included

At the funeral, organizations that Shepard was part of sent representatives, including the Union League Club, the Republican County Committee, the Republican Club, the New York State Bar Association, the Presbyterian Union, the Chamber of Commerce, the American Sabbath Union, New York Sabbath Observance Committee, American Bible Society, St. Paul's Institute at Tarsus, the Union League of Brooklyn, the Republican Association of the 21st Assembly District, the Shepard Rifles, the New York Typothetae, the American Bank Note Company, the College of the City of New York, the ''Mail and Express'', and the New-York Press Club. Those at the funeral included

Letter to Walt Whitman, from The Walt Whitman Archive

*

by

Mail and Express

The ''New York Evening Mail'' (1867–1924) was an American daily newspaper published in New York City. For a time the paper was the only evening newspaper to have a franchise in the Associated Press.

History Names

The paper was founded as the ' ...

'' newspaper, as well as a founder and president of the New York State Bar Association

The New York State Bar Association (NYSBA) is a voluntary bar association for the state of New York. The mission of the association is to cultivate the science of jurisprudence; promote reform in the law; facilitate the administration of justice ...

. Shepard was married to Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt

Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard (New Dorp, July 23, 1845 – Manhattan, March 3, 1924) was an American heiress and a member of the prominent Vanderbilt family. As a philanthropist, she funded the YMCA, helping create a hotel for guests of the o ...

, who was the granddaughter of philanthropist, business magnate, and family patriarch Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

. Shepard's Briarcliff Manor

Briarcliff Manor () is a suburban village in Westchester County, New York, north of New York City. It is on of land on the east bank of the Hudson River, geographically shared by the towns of Mount Pleasant and Ossining. Briarcliff Manor inc ...

residence Woodlea

Sleepy Hollow Country Club is a historic country club in Scarborough-on-Hudson in Briarcliff Manor, New York. The club was founded in 1911, and its clubhouse was known as Woodlea, a 140-room Vanderbilt mansion owned by Colonel Elliott Fitch Shep ...

and the Scarborough Presbyterian Church

The Scarborough Historic District is a national historic district located in the suburban community of Scarborough-on-Hudson, in Briarcliff Manor, New York. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, and conta ...

, which he founded nearby, are contributing properties to the Scarborough Historic District

The Scarborough Historic District is a national historic district located in the suburban community of Scarborough-on-Hudson, in Briarcliff Manor, New York. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, and contain ...

.

Shepard was born in Jamestown, New York

Jamestown is a city in southern Chautauqua County, in the U.S. state of New York. The population was 28,712 at the 2020 census. Situated between Lake Erie to the north and the Allegheny National Forest to the south, Jamestown is the largest pop ...

, one of three sons of the president of a banknote-engraving company. He attended the City University of New York

The City University of New York ( CUNY; , ) is the Public university, public university system of Education in New York City, New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven Upper divis ...

, and practiced law for about 25 years. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Shepard was a Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

recruiter and subsequently earned the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

. He was later a founder and benefactor of several institutions and banks. When Shepard moved to the Briarcliff Manor hamlet of Scarborough-on-Hudson

Briarcliff Manor () is a suburban village in Westchester County, New York, north of New York City. It is on of land on the east bank of the Hudson River, geographically shared by the towns of Mount Pleasant and Ossining. Briarcliff Manor inc ...

, he founded the Scarborough Presbyterian Church and built Woodlea; the house and its land are now part of Sleepy Hollow Country Club

Sleepy Hollow Country Club is a historic country club in Scarborough-on-Hudson in Briarcliff Manor, New York. The club was founded in 1911, and its clubhouse was known as Woodlea, a 140-room Vanderbilt mansion owned by Colonel Elliott Fitch Shep ...

.

Early life

Shepard was born July 25, 1833, in Jamestown in

Shepard was born July 25, 1833, in Jamestown in Chautauqua County, New York

Chautauqua County is the westernmost County (United States), county in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. As of the United States Census 2020, 2020 census, the population was 127,657. Its county seat is Mayville, New York, Mayville, an ...

. He was the second of three sons of Fitch Shepard and Delia Maria Dennis; the others were Burritt Hamilton and Augustus Dennis. Fitch Shepard was president of the National Bank Note Company (later consolidated with the American and Continental Note Companies), and Elliott's brother Augustus became president of the American Bank Note Company

ABCorp is an American corporation providing contract manufacturing and related services to the authentication, payment and secure access business sectors. Its history dates back to 1795 as a secure engraver and printer, and assisting the newl ...

. Shepard's extended family lived in New England, with origins in Bedfordshire, England

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council was a ...

. Fitch, son of Noah Shepard, was a descendant of Thomas Shepard (a Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

minister) and James Fitch (son-in-law of William Bradford). Delia Maria Dennis was a descendant of Robert Dennis, who emigrated from England in 1635. Elliott was described in 1897's ''Prominent Families of New York'' as "prominent by birth and ancestry, as well as for his personal qualities". He attended public schools in Jamestown, and moved with his father and brothers to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in 1845. He began attending the college-preparatory University Grammar School (then located in the City University of New York

The City University of New York ( CUNY; , ) is the Public university, public university system of Education in New York City, New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven Upper divis ...

building), and graduated from the university in 1855. Shepard began reading law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

under Edwards Pierrepont

Edwards Pierrepont (March 4, 1817 – March 6, 1892) was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierre ...

, and was admitted to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in the city of Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

in 1858.

Military service

From January 1861 through the outbreak of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and until 1862 Shepard served as an '' aide-de-camp'' to Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

General Edwin D. Morgan

Edwin Denison Morgan (February 8, 1811February 14, 1883) was the 21st governor of New York from 1859 to 1862 and served in the United States Senate from 1863 to 1869. He was the first and longest-serving chairman of the Republican National Comm ...

with the rank of colonel. During this time Shepard was placed in command of the department of volunteers in Elmira, and enlisted 47,000 men from the surrounding area. In 1862 he was appointed Assistant Inspector-General for half of New York state, reporting to New York's governor on troop organization, equipment, and discipline.

In 1862 he visited Jamestown to inspect, equip and provide uniforms for the Chautauqua regiment, his first return since infancy, and was welcomed by a group of prominent citizens. Shepard recruited and organized the 51st Regiment, New York Volunteers, which was named the Shepard Rifles in his honor. George W. Whitman, brother of the poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among t ...

and a member of the regiment, was notified by Shepard of a promotion; Shepard may have influenced his subsequent promotion to major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

in 1865. In addition, Shepard was involved in correspondence with Walt Whitman. Although President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

offered him a promotion to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

, Shepard declined in deference to officers who had seen field service; Shepard himself never entered the field. From 1866 to 1868 Shepard served as ''aide-de-camp'' to Reuben E. Fenton

Reuben Eaton Fenton (July 4, 1819August 25, 1885) was an American merchant and politician from New York (state), New York. In the mid-19th Century, he served as a United States House of Representatives , U.S. Representative, a United States Sen ...

.

*

*

*

Career

In 1864, Shepard was a member of the executive committee and chair of the Committee on Contributions from Without the City for the New York Metropolitan Fair. He chaired lawyers' committees for disaster relief, including those in

In 1864, Shepard was a member of the executive committee and chair of the Committee on Contributions from Without the City for the New York Metropolitan Fair. He chaired lawyers' committees for disaster relief, including those in Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropol ...

and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

after the 1866 Great Fire and the 1871 Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 10 ...

respectively, and was a member of the municipal committee for victims of the 1889 Johnstown Flood

The Johnstown Flood (locally, the Great Flood of 1889) occurred on Friday, May 31, 1889, after the catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam, located on the south fork of the Little Conemaugh River, upstream of the town of Johnstown, Pennsylv ...

.

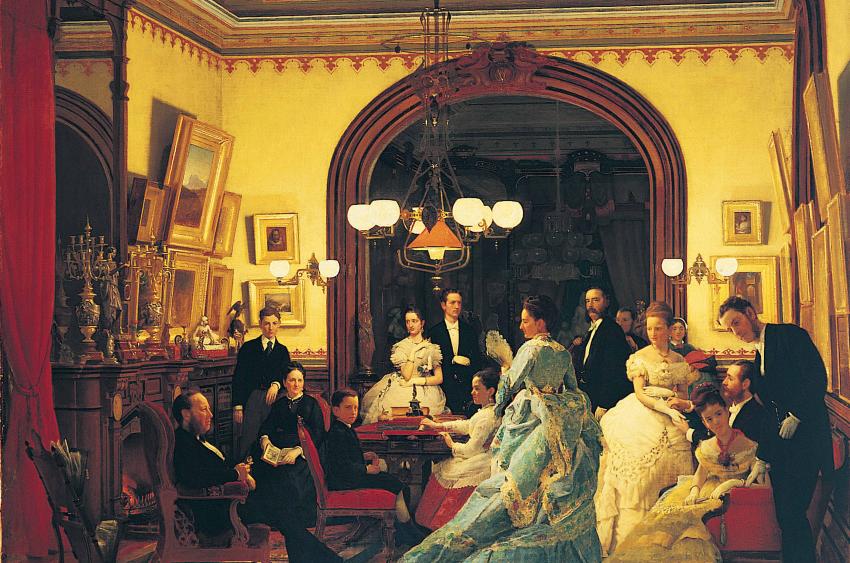

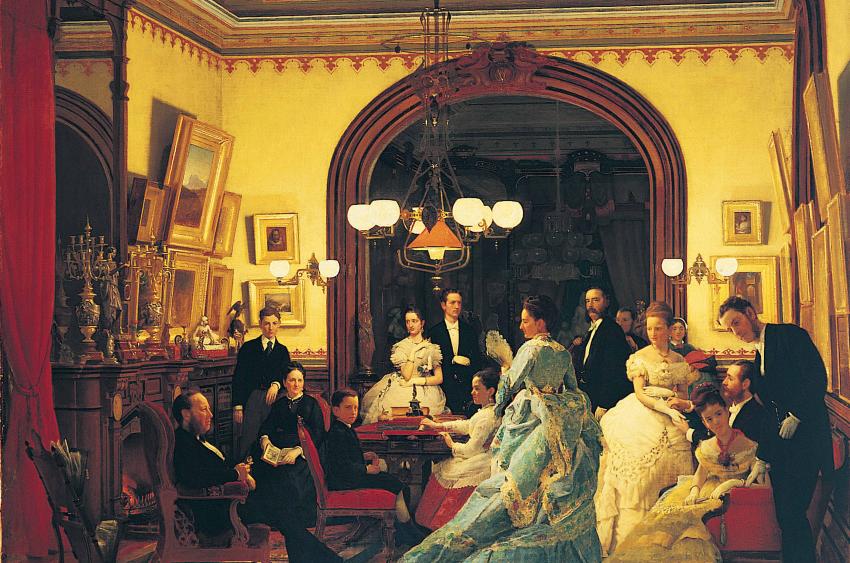

In 1867 Shepard was presented to Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt

Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard (New Dorp, July 23, 1845 – Manhattan, March 3, 1924) was an American heiress and a member of the prominent Vanderbilt family. As a philanthropist, she funded the YMCA, helping create a hotel for guests of the o ...

at a reception given by Governor Morgan; their difficult courtship was opposed by Margaret's father, William Henry Vanderbilt

William Henry Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821 – December 8, 1885) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, an heir to his fortune and a prominent member of the Vanderbilt family. Vanderbi ...

. A year later, on February 18, 1868, they were married in the Church of the Incarnation in New York City. After an 1868 trip to Tarsus, Mersin

Tarsus (Hittite language, Hittite: 𒋫𒅈𒊭 ; grc, Ταρσός, label=Ancient Greek, Greek ; xcl, Տարսոն, label=Old Armenian, Armenian ; ar, طَرسُوس ) is a historic city in south-central Turkey, inland from the Mediterranea ...

he helped found Tarsus American College, agreeing to donate $5,000 a year to the school and leave it an endowment of $100,000 ($ in ). He became one of the school's trustees and vice presidents.

In 1868, Shepard became a partner of Judge Theron R. Strong

Theron Rudd Strong (November 7, 1802 Salisbury, Litchfield County, Connecticut – May 14, 1873) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. From 1839 to 1841, he served one term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Life

He studied law a ...

in Strong & Shepard, continuing the business after Strong's death. He continued to practice law for the next 25 years; he helped found the New York State Bar Association

The New York State Bar Association (NYSBA) is a voluntary bar association for the state of New York. The mission of the association is to cultivate the science of jurisprudence; promote reform in the law; facilitate the administration of justice ...

in 1876, and in 1884 was its fifth president. In 1875 Shepard drafted an amendment establishing an arbitration court for the New York Chamber of Commerce

The New York Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1768 by twenty New York City merchants. As the first such commercial organization in the United States, it attracted the participation of a number of New York's most influential business leaders, in ...

, serving on its five-member executive committee the following year. In 1880, the New York City Board of Aldermen

The New York City Board of Aldermen was a body that was the upper house of New York City's Common Council from 1824 to 1875, the lower house of its Municipal Assembly upon consolidation in 1898 until the charter was amended in 1901 to abolish t ...

appointed Shepard and Ebenezer B. Shafer to revise and codify the city's local ordinances

A local ordinance is a law issued by a local government. such as a municipality, county, parish, prefecture, or the like.

China

In Hong Kong, all laws enacted by the territory's Legislative Council remain to be known as ''Ordinances'' () af ...

to form the New-York Municipal Code; the last revision was in 1859.

During the 1880s he helped found three banks. At the Bank of the Metropolis

The Bank of the Metropolis was a bank in New York City that operated between 1871 and 1918. The bank was originally located at several addresses around Union Square in Manhattan before finally moving to 31 Union Square West, a 16-story Renaissa ...

, he was a founding board member. The others were the American Savings Bank and the Columbian National Bank, where he served as attorney. In 1881, US President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

nominated him for United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York

The United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York is the chief federal law enforcement officer in eight New York counties: New York (Manhattan), Bronx, Westchester, Putnam, Rockland, Orange, Dutchess and Sullivan. Establishe ...

. In 1884, Shepard led the effort to create an arbitration court for the New York Chamber of Commerce

The New York Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1768 by twenty New York City merchants. As the first such commercial organization in the United States, it attracted the participation of a number of New York's most influential business leaders, in ...

. On March 20, 1888, Shepard purchased the ''Mail and Express

The ''New York Evening Mail'' (1867–1924) was an American daily newspaper published in New York City. For a time the paper was the only evening newspaper to have a franchise in the Associated Press.

History Names

The paper was founded as the ' ...

'' newspaper (founded in 1836, with an estimated value in 1888 of $200,000 ($ in ) from Cyrus W. Field for $425,000 ($ in ). Deeply religious, Shepard placed a verse from the Bible at the head of each edition's editorial page. As president of the newspaper company until his death, he approved every important decision or policy. In the same year, Shepard became the controlling stockholder of the Fifth Avenue Transportation Company

The Fifth Avenue Transportation Company was a transportation company based in New York which was founded in 1885 and operated of horse-and-omninbus transit along Fifth Avenue, with a route running from 89th Street to Bleecker Street using horse-d ...

to force it to halt work on Sundays (the Christian Sabbath

Sabbath in Christianity is the inclusion in Christianity of a Sabbath, a day set aside for rest and worship, a practice that was mandated for the Israelites in the Ten Commandments in line with God's blessing of the seventh day (Saturday) making it ...

).

When Margaret's father died in 1885, she inherited $12 million ($ in ). The family lived at 2 West 52nd Street

52nd Street is a -long one-way street traveling west to east across Midtown Manhattan, New York City. A short section of it was known as the city's center of jazz performance from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Jazz center

Following the repeal of ...

in Manhattan, one of three houses of the Vanderbilt Triple Palace

The Triple Palace, also known as the William H. Vanderbilt House, was an elaborate mansion at 640 Fifth Avenue between 51st Street and 52nd Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The urban mansion, completed in 1882 to designs by John B. ...

which were built during the 1880s for William Henry Vanderbilt and his two daughters. After Elliott's death Margaret transferred the house to her sister's family, who combined their two houses into one. The houses were eventually demolished; the nine-story De Pinna

De Pinna was a high-end clothier for men and women founded in New York City in 1885, by Alfred De Pinna (1831 - 1915), a Sephardic Jew born in England. They also sold menswear-inspired clothing for women that was finely tailored. The flagship sto ...

Building was built there in 1928 and was demolished around 1969. 650 Fifth Avenue

650 Fifth Avenue (earlier known as the Piaget Building and the Pahlavi Foundation Building) is a 36-story building on the edge of Rockefeller Center on 52nd Street in New York City.

The building was designed by John Carl Warnecke & Associates ...

is the building currently on the site.

Shepard and his family toured the world in 1884, visiting Asia, Africa, and Europe. He documented his 1887 trip from New York to Alaska in ''The Riva.: New York and Alaska'' taken by himself, his wife and daughter, six other family members, their maid, a chef, butler, porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian regional airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., ...

and conductor. According to Shepard, the family traveled on 26 railroads and stayed at 38 hotels in nearly five months. After the 1884 trip, aware of the opportunity for church work in the territory, he founded a mission and maintained it with his wife for about $20,000 ($ in ) a year. For some time Shepard worshiped at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church

Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church is a Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) church in New York City. The church, on Fifth Avenue at 7 West 55th Street in Midtown Manhattan, has approximately 2,200 members and is one of the larger PCUSA congregations. The ...

under John Hall, and was a vice president of the Presbyterian Union of New-York. Shepard was president of the American Sabbath Union for five years, and he also served as the chairman of the Special Committee on Sabbath Observance.

Briarcliff Manor developments

During the early 1890s Shepard moved toScarborough-on-Hudson

Briarcliff Manor () is a suburban village in Westchester County, New York, north of New York City. It is on of land on the east bank of the Hudson River, geographically shared by the towns of Mount Pleasant and Ossining. Briarcliff Manor inc ...

in present-day Briarcliff Manor, purchasing a Victorian house

In Great Britain and former British colonies, a Victorian house generally means any house built during the reign of Queen Victoria. During the Industrial Revolution, successive housing booms resulted in the building of many millions of Victorian ...

from J. Butler Wright. He had a mansion (named Woodlea, after Wright's house) built south of the house, facing the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

, and improved its grounds. Construction of the mansion began in 1892, and was completed three years later. Shepard died in 1893, leaving Margaret to oversee its completion. The finished house has between , making it one of the largest privately owned houses in the United States.

After Shepard's death Margaret lived there in the spring and fall, with her visits becoming less frequent. By 1900 she began selling property to Frank A. Vanderlip

Frank Arthur Vanderlip Sr. (November 17, 1864 – June 30, 1937) was an American banker and journalist. He was president of the National City Bank of New York (now Citibank) from 1909 to 1919, and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury from 18 ...

and William Rockefeller

William Avery Rockefeller Jr. (May 31, 1841 – June 24, 1922) was an American businessman and financier. Rockefeller was a co-founder of Standard Oil along with his elder brother John Davison Rockefeller. He was also part owner of the Anaconda ...

, selling them the house in 1910. Vanderlip and Rockefeller assembled a board of directors to create a country club; they first met at Vanderlip's National City Bank Building office at 55 Wall Street

55 Wall Street, formerly known as the National City Bank Building, is an eight-story building on Wall Street between William and Hanover streets in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City, United States. The lowest three stor ...

(Vanderlip was president of the bank at the time). Sleepy Hollow Country Club was founded, with Woodlea becoming its clubhouse and the J. Butler Wright house as its golf house.

Shepard established a small chapel on his Briarcliff Manor property, and founded the Scarborough Presbyterian Church

The Scarborough Historic District is a national historic district located in the suburban community of Scarborough-on-Hudson, in Briarcliff Manor, New York. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, and conta ...

in 1892. The church and its manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from '' ...

were donated by Margaret after his death. It was designed by Augustus Haydel (a nephew of Stanford White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect. He was also a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms. He designed many houses for the rich, in additio ...

) and August D. Shepard Jr. (a nephew of Elliott Shepard and William Rutherford Mead

William Rutherford Mead (August 20, 1846 – June 19, 1928) was an American architect who was the "Center of the Office" of McKim, Mead, and White, a noted Gilded Age architectural firm.Baker, Paul R. ''Stanny'' The firm's other founding pa ...

). The church, dedicated on May 11, 1895, in Shepard's memory, was briefly known as Shepard Memorial Church.

Family and personal life

Shepard and Margaret had five daughters and one son: Florence (1869–1869), Maria Louise (1870–1948), Edith (1872–1954), Marguerite (1873–1895),

Shepard and Margaret had five daughters and one son: Florence (1869–1869), Maria Louise (1870–1948), Edith (1872–1954), Marguerite (1873–1895), Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

(1874–1950) and Elliott Jr. (1877–1927). The children attended Sunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

and church, and were educated by private tutors and governesses

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, t ...

. Shepard also employed a private chef for his family. Shepard was a strict father known to beat his son, who was described as being as wild as his father was rigid and moralizing.

Shepard was tall, with a pleasant expression and manner, and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' called him the "perfect type of well-bred clubman". He had thick hair, manicured nails, a well-trimmed beard and an athletic figure. An opponent of antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, he attended dinners publicizing the plight of Russian Jews and regularly addressed Jewish religious and social organizations avoided by others. He rented pews in many New York churches, supported about a dozen missionaries and was described as a generous donor to hospitals and charitable societies. Shepard was politically ambitious, and decided to build Woodlea as a symbol of power and influence. Shepard had horses and carriages which were ridden by the family in parks, and he prided himself on his equestrianism

Equestrianism (from Latin , , , 'horseman', 'horse'), commonly known as horse riding (Commonwealth English) or horseback riding (American English), includes the disciplines of riding, Driving (horse), driving, and Equestrian vaulting, vaulting ...

. Shepard was a long-time friend of US Senator Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, as ...

.

Shepard was a supporter of the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

, contributing $75,000 ($ in ) to the 1888 Presidential campaign fund and $10,000 ($ in ) to the state committee for the Fassett campaign. He furnished Shepard Hall, at Sixth Avenue and 57th Street in New York City, offering it rent-free to the Republican Club.

Shepard belonged to a number of organizations: the Adirondack League, the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

, the American Oriental Society

The American Oriental Society was chartered under the laws of Massachusetts on September 7, 1842. It is one of the oldest learned societies in America, and is the oldest devoted to a particular field of scholarship.

The Society encourages basic ...

, the Association of the Bar of the City of New York

The New York City Bar Association (City Bar), founded in 1870, is a voluntary association of lawyers and law students. Since 1896, the organization, formally known as the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, has been headquartered in a ...

, the Century Association

The Century Association is a private social, arts, and dining club in New York City, founded in 1847. Its clubhouse is located at 7 West 43rd Street near Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. It is primarily a club for men and women with distinction ...

, the Congregational Club, the Lawyers' Club of New York, the Manhattan Athletic Club

The Manhattan Athletic Club was an athletic club in Manhattan, New York City. The club was founded on November 7, 1877, and legally incorporated on April 1, 1878. Its emblem was a "cherry diamond".

It established an athletic cinder ash track at ...

, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

, the National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design is an honorary association of American artists, founded in New York City in 1825 by Samuel Morse, Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Martin E. Thompson, Charles Cushing Wright, Ithiel Town, and others "to promote the fin ...

, the New England Society of New York

The New England Society in the City of New York (NES) is one of several lineage organizations in the United States and one of the oldest charitable societies in the country. It was founded in 1805 to promote “friendship, charity and mutual a ...

, the New York Athletic Club

The New York Athletic Club is a private social club and athletic club in New York state. Founded in 1868, the club has approximately 8,600 members and two facilities: the City House, located at 180 Central Park South in Manhattan, and Travers ...

, the New York Press Club The New York Press Club, sometimes ''NYPC'', is a private nonprofit membership organization which promotes journalism in the New York City metropolitan area. It is unaffiliated with any government organization and abstains from politics. While the c ...

, the New York State Bar Association

The New York State Bar Association (NYSBA) is a voluntary bar association for the state of New York. The mission of the association is to cultivate the science of jurisprudence; promote reform in the law; facilitate the administration of justice ...

, the New York Yacht Club

The New York Yacht Club (NYYC) is a private social club and yacht club based in New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. It was founded in 1844 by nine prominent sportsmen. The members have contributed to the sport of yachting and yacht design. ...

, the Presbyterian Union of New York, the Republican Club of the City of New York, the Riding Club, the Sons of the American Revolution

The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR or NSSAR) is an American Congressional charter, congressionally chartered organization, founded in 1889 and headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky, Louisville, Kentucky. A non-prof ...

, the Twilight Club

The Twilight Club was a dinner club in New York City that operated from 1883 until 1904. It was founded by Charles F. Wingate "to cultivate good fellowship and enjoy rational recreation."

Formation

On January 4, 1883, the Twilight Club was fo ...

, the Union League Club of New York

The Union League Club is a private social club in New York City that was founded in 1863 in affiliation with the Union League. Its fourth and current clubhouse is located at 38 East 37th Street on the corner of Park Avenue, in the Murray Hill ...

, and the Union League

The Union Leagues were quasi-secretive men’s clubs established separately, starting in 1862, and continuing throughout the Civil War (1861–1865). The oldest Union League of America council member, an organization originally called "The Leag ...

of Brooklyn.

Later life, death, and legacy

In 1892, the City University of New York gave Shepard a

In 1892, the City University of New York gave Shepard a Master of Laws

A Master of Laws (M.L. or LL.M.; Latin: ' or ') is an advanced postgraduate academic degree, pursued by those either holding an undergraduate academic law degree, a professional law degree, or an undergraduate degree in a related subject. In mos ...

degree and the University of Omaha

The University of Nebraska Omaha (Omaha or UNO) is a public research university in Omaha, Nebraska. Founded in 1908 by faculty from the Omaha Presbyterian Theological Seminary as a private non-sectarian college, the university was originally kno ...

gave him a Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor (LL. ...

degree. On January 11, 1893, Shepard addressed the House Committee on the Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

in an effort to convince the committee not to open the exposition on a Sunday - the Sabbath. Shepard himself attended, having spent $25,000 ($ in ) on September 7, 1891, in reserving sixteen rooms with board at the Auditorium Hotel for six months during the fair.

Shepard died unexpectedly during the afternoon of March 24, 1893 at his Manhattan residence. Two doctors were attempting to remove a bladder stone

A bladder stone is a stone found in the urinary bladder.

Signs and symptoms

Bladder stones are small mineral deposits that can form in the bladder. In most cases bladder stones develop when the urine becomes very concentrated or when one is d ...

from him. They instructed him to eat lightly, only well before the operation. They gave him the anesthetic ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be c ...

at 12:45 p.m. For a few minutes Shepard did not seem to react, though soon afterward his color started changing and his respiration and pulse dimmed, so administration of ether was stopped, however not enough ether was given to continue with the operation. His condition started to worsen again; the doctors suspected food or vomit was blocking his windpipe or bronchial tubes. The doctors then administered oxygen, which helped temporarily; however, at 4:00 p.m. his pulse became steadily more feeble, he fell unconscious, and died at 4:10 p.m. His cause of death was edema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's Tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels t ...

and congestion of the lungs, after the administration of ether, but due to an unknown cause.

Many doctors considered the case to be unusual and debated the cause of death. Some, including family members, accused them of criminal negligence; that Shepard was fed well before the operation, which could have allowed him to choke on vomit. No autopsy was made, but an inquest was made by the coroner. The two doctors to perform the operation made a statement on March 28, 1893, that after prior examinations no diseases were found and his heart and lungs seemed healthy. A ''Tribune'' reporter met doctor William J. Morton, son of possible ether discoverer William T. G. Morton

William Thomas Green Morton (August 9, 1819 – July 15, 1868) was an American dentist and physician who first publicly demonstrated the use of inhaled ether as a surgical anesthetic in 1846. The promotion of his questionable claim to have been th ...

who had first used it in 1846. Morton said it was most improbable Shepard died of ether, ensuring its safety when properly used, and that deaths were one in 25,000. He recommended an autopsy.

The first funeral service was a small gathering of pallbearers and close friends of the family at the house; then Shepard's body was moved to their church. From the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, Shepard was moved to the Battery and then onto a ferry to Staten Island.

At the funeral, organizations that Shepard was part of sent representatives, including the Union League Club, the Republican County Committee, the Republican Club, the New York State Bar Association, the Presbyterian Union, the Chamber of Commerce, the American Sabbath Union, New York Sabbath Observance Committee, American Bible Society, St. Paul's Institute at Tarsus, the Union League of Brooklyn, the Republican Association of the 21st Assembly District, the Shepard Rifles, the New York Typothetae, the American Bank Note Company, the College of the City of New York, the ''Mail and Express'', and the New-York Press Club. Those at the funeral included

At the funeral, organizations that Shepard was part of sent representatives, including the Union League Club, the Republican County Committee, the Republican Club, the New York State Bar Association, the Presbyterian Union, the Chamber of Commerce, the American Sabbath Union, New York Sabbath Observance Committee, American Bible Society, St. Paul's Institute at Tarsus, the Union League of Brooklyn, the Republican Association of the 21st Assembly District, the Shepard Rifles, the New York Typothetae, the American Bank Note Company, the College of the City of New York, the ''Mail and Express'', and the New-York Press Club. Those at the funeral included Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt (January 7, 1830 – February 18, 1902) was a German-American painter best known for his lavish, sweeping landscapes of the American West. He joined several journeys of the Westward Expansion to paint the scenes. He was no ...

, Noah Davis, Chauncey M. Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, as ...

, John S. Kennedy

John Stewart Kennedy (January 4, 1830 – October 30, 1909) was a Scottish-born American businessman, financier and philanthropist. He was a member of the Jekyll Island Club (also known as The Millionaires' Club) on Jekyll Island, Georgia a ...

, John James McCook

John James McCook (February 21, 1806 – October 11, 1865), was a patriarch of the Fighting McCooks, one of the most prolific families in United States Army history. Five of his sons became prominent soldiers, chaplains, or sailors, as well as ei ...

, Warner Miller

Warner Miller (August 12, 1838March 21, 1918) was an American businessman and politician from Herkimer, New York. A Republican, he was most notable for his service as a U.S. Representative (1879-1881) and United States Senator (1881-1887).

A nat ...

, John Sloane, and John H. Starin

John Henry Starin (August 27, 1825March 21, 1909) was a successful entrepreneur and businessman notably in the logistics and amusement industries. In addition to serving as a U.S. representative from New York in Congress, he founded Starin's Glen ...

. Notable family included his immediate family, as well as most of the living Vanderbilt family, including the majority of Margaret Louisa's siblings, their spouses, and Margaret Louisa's mother.

Shepard was first buried in the Vanderbilt mausoleum in Moravian Cemetery

The Moravian Cemetery is a cemetery in the New Dorp neighborhood of Staten Island, New York City.

Location

Located at 2205 Richmond Road, the Moravian Cemetery is the largest and oldest active cemetery on Staten Island, having opened in 1740. T ...

. On November 17, 1894, one of his daughters, his wife, and her brother George Vanderbilt oversaw the transfer of his remains and those of his daughter Florence to a new Shepard family tomb in the cemetery nearby.

Shepard's estate included the $100,000 Tarsus American College endowment, $850,000 in real estate and $500,000 in personal property for a total of $1.35 million ($ in ). His will distributed money and property to his wife and children, his brother Augustus, and religious organizations. Shepard funded a number of scholarships and prizes

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

, including one at the City University of New York and New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then-Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, the ...

's annual Elliott F. Shepard Scholarship, and in 1888 he donated a large collection of books originally from lawyer Aaron J. Vanderpoel's library to the New York University School of Law

New York University School of Law (NYU Law) is the law school of New York University, a private research university in New York City. Established in 1835, it is the oldest law school in New York City and the oldest surviving law school in New ...

. A year later, Shepard created an endowment for periodicals, necessitating the creation of the university's first reading room. In 1897, Shepard's wife donated his 1,390-volume collection of law books to the library.

When the wife of Chicago publisher Horace O'Donoghue read him the news of Shepard's death four days after the event, he picked up a razor and slit his throat. Although his suicide was first thought to be an impulsive reaction, it was later learned that the likely cause was O'Donoghue's large debts to Chicago publishing houses.

Selected works

* *Notes

References

Further reading

* For details on Elliott Fitch Shepard's average business day and family.External links

Letter to Walt Whitman, from The Walt Whitman Archive

*

by

John Quincy Adams Ward

John Quincy Adams Ward (June 29, 1830 – May 1, 1910) was an American sculptor, whose most familiar work is his larger than life-size standing Statue of George Washington (Wall Street), statue of George Washington on the steps of Federal Hall, Fe ...

, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shepard, Elliott Fitch

1833 births

1893 deaths

19th-century American lawyers

19th-century American male writers

19th-century American newspaper editors

19th-century American writers

19th-century American philanthropists

19th-century Presbyterians

American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law

American male journalists

American Presbyterians

City University of New York alumni

Deaths from edema

Editors of New York (state) newspapers

Journalists from New York City

New York (state) lawyers

New York (state) Republicans

People from Briarcliff Manor, New York

People from Dobbs Ferry, New York

People from Jamestown, New York

People from Manhattan

People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

Philanthropists from New York (state)

Sons of the American Revolution

Union Army colonels

Elliott Fitch Shephard

19th-century American businesspeople

Burials at Moravian Cemetery