Einsatzgruppe Diamant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary

In response to

In response to

All four main took part in mass shootings from the early days of the war. Initially the targets were adult Jewish men, but by August the net had been widened to include women, children, and the elderly—the entire Jewish population. Initially there was a semblance of legality given to the shootings, with trumped-up charges being read out (arson, sabotage, black marketeering, or refusal to work, for example) and victims being murdered by a firing squad. As this method proved too slow, the began to take their victims out in larger groups and shot them next to, or even inside, mass graves that had been prepared. Some started to use automatic weapons, with survivors being murdered with a pistol shot.

As word of the massacres got out, many Jews fled; in Ukraine, 70 to 90 per cent of the Jews ran away. This was seen by the leader of VI as beneficial, as it would save the regime the costs of deporting the victims further east over the Urals. In other areas the invasion was so successful that the had insufficient forces to immediately murder all the Jews in the conquered territories. A situation report from C in September 1941 noted that not all Jews were members of the Bolshevist apparatus, and suggested that the total elimination of Jewry would have a negative impact on the economy and the food supply. The Nazis began to round their victims up into concentration camps and ghettos and rural districts were for the most part rendered (free of Jews). Jewish councils were set up in major cities and forced labour gangs were established to make use of the Jews as slave labour until they were totally eliminated, a goal that was postponed until 1942.

The used public hangings as a terror tactic against the local population. An B report, dated 9 October 1941, described one such hanging. Due to suspected partisan activity near Demidov, all male residents aged 15 to 55 were put in a camp to be screened. The screening produced seventeen people who were identified as "partisans" and "Communists". Five members of the group were hanged while 400 local residents were assembled to watch; the rest were shot.

All four main took part in mass shootings from the early days of the war. Initially the targets were adult Jewish men, but by August the net had been widened to include women, children, and the elderly—the entire Jewish population. Initially there was a semblance of legality given to the shootings, with trumped-up charges being read out (arson, sabotage, black marketeering, or refusal to work, for example) and victims being murdered by a firing squad. As this method proved too slow, the began to take their victims out in larger groups and shot them next to, or even inside, mass graves that had been prepared. Some started to use automatic weapons, with survivors being murdered with a pistol shot.

As word of the massacres got out, many Jews fled; in Ukraine, 70 to 90 per cent of the Jews ran away. This was seen by the leader of VI as beneficial, as it would save the regime the costs of deporting the victims further east over the Urals. In other areas the invasion was so successful that the had insufficient forces to immediately murder all the Jews in the conquered territories. A situation report from C in September 1941 noted that not all Jews were members of the Bolshevist apparatus, and suggested that the total elimination of Jewry would have a negative impact on the economy and the food supply. The Nazis began to round their victims up into concentration camps and ghettos and rural districts were for the most part rendered (free of Jews). Jewish councils were set up in major cities and forced labour gangs were established to make use of the Jews as slave labour until they were totally eliminated, a goal that was postponed until 1942.

The used public hangings as a terror tactic against the local population. An B report, dated 9 October 1941, described one such hanging. Due to suspected partisan activity near Demidov, all male residents aged 15 to 55 were put in a camp to be screened. The screening produced seventeen people who were identified as "partisans" and "Communists". Five members of the group were hanged while 400 local residents were assembled to watch; the rest were shot.

A operated in

A operated in  In late 1941, the settled into headquarters in Kaunas, Riga, and Tallinn. A grew less mobile and faced problems because of its small size. The Germans relied increasingly on the Latvian and similar groups to perform massacres of Jews.

Such extensive and enthusiastic collaboration with the has been attributed to several factors. Since the

In late 1941, the settled into headquarters in Kaunas, Riga, and Tallinn. A grew less mobile and faced problems because of its small size. The Germans relied increasingly on the Latvian and similar groups to perform massacres of Jews.

Such extensive and enthusiastic collaboration with the has been attributed to several factors. Since the

B, C, and D did not immediately follow A's example in systematically murdering all Jews in their areas. The commanders, with the exception of A's Stahlecker, were of the opinion by the fall of 1941 that it was impossible to murder the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union in one sweep, and thought the murders should stop. An report dated 17 September advised that the Germans would be better off using any skilled Jews as labourers rather than shooting them. Also, in some areas poor weather and a lack of transportation led to a slowdown in deportations of Jews from points further west. Thus, an interval passed between the first round of massacres in summer and fall, and what American historian

B, C, and D did not immediately follow A's example in systematically murdering all Jews in their areas. The commanders, with the exception of A's Stahlecker, were of the opinion by the fall of 1941 that it was impossible to murder the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union in one sweep, and thought the murders should stop. An report dated 17 September advised that the Germans would be better off using any skilled Jews as labourers rather than shooting them. Also, in some areas poor weather and a lack of transportation led to a slowdown in deportations of Jews from points further west. Thus, an interval passed between the first round of massacres in summer and fall, and what American historian

After a time, Himmler found that the killing methods used by the were inefficient: they were costly, demoralising for the troops, and sometimes did not kill the victims quickly enough. Many of the troops found the massacres to be difficult if not impossible to perform. Some of the perpetrators suffered physical and mental health problems, and many turned to drink. As much as possible, the leaders militarized the genocide. The historian Christian Ingrao notes an attempt was made to make the shootings a collective act without individual responsibility. Framing the shootings in this way was not psychologically sufficient for every perpetrator to feel absolved of guilt. Browning notes three categories of potential perpetrators: those who were eager to participate right from the start, those who participated in spite of moral qualms because they were ordered to do so, and a significant minority who refused to take part. A few men spontaneously became excessively brutal in their killing methods and their zeal for the task. Commander of D, SS-

After a time, Himmler found that the killing methods used by the were inefficient: they were costly, demoralising for the troops, and sometimes did not kill the victims quickly enough. Many of the troops found the massacres to be difficult if not impossible to perform. Some of the perpetrators suffered physical and mental health problems, and many turned to drink. As much as possible, the leaders militarized the genocide. The historian Christian Ingrao notes an attempt was made to make the shootings a collective act without individual responsibility. Framing the shootings in this way was not psychologically sufficient for every perpetrator to feel absolved of guilt. Browning notes three categories of potential perpetrators: those who were eager to participate right from the start, those who participated in spite of moral qualms because they were ordered to do so, and a significant minority who refused to take part. A few men spontaneously became excessively brutal in their killing methods and their zeal for the task. Commander of D, SS-

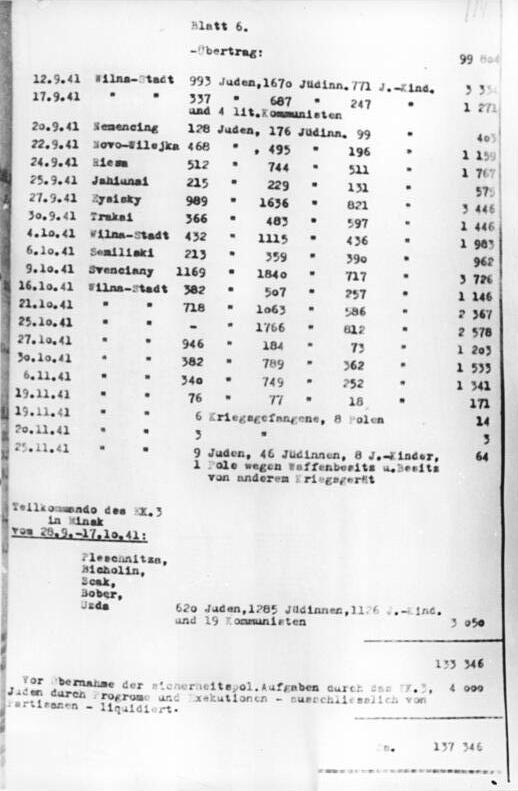

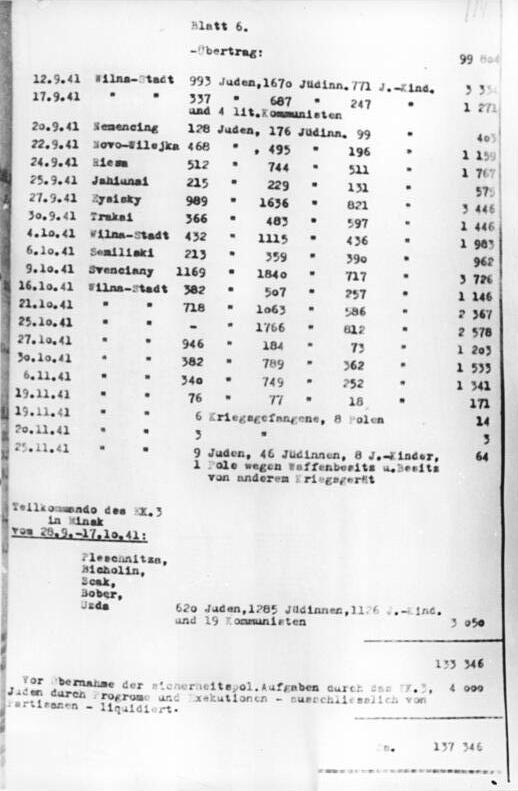

The kept official records of many of their massacres and provided detailed reports to their superiors. The

The kept official records of many of their massacres and provided detailed reports to their superiors. The

Several leaders, including Ohlendorf, claimed at the trial to have received an order before Operation Barbarossa requiring them to murder all Soviet Jews. To date no evidence has been found that such an order was ever issued. German prosecutor Alfred Streim noted that if such an order had been given, post-war courts would only have been able to convict the leaders as ''accomplices'' to mass murder. However, if it could be established that the had committed mass murder without orders, then they could have been convicted as ''perpetrators'' of mass murder, and hence could have received stiffer sentences, including capital punishment.

Streim postulated that the existence of an early comprehensive order was a fabrication created for use in Ohlendorf's defence. This theory is now widely accepted by historians. Longerich notes that most orders received by the leaders—especially when they were being ordered to carry out criminal activities—were vague, and couched in terminology that had a specific meaning for members of the regime. Leaders were given briefings about the need to be "severe" and "firm"; all Jews were to be viewed as potential enemies that had to be dealt with ruthlessly. British historian Sir

Several leaders, including Ohlendorf, claimed at the trial to have received an order before Operation Barbarossa requiring them to murder all Soviet Jews. To date no evidence has been found that such an order was ever issued. German prosecutor Alfred Streim noted that if such an order had been given, post-war courts would only have been able to convict the leaders as ''accomplices'' to mass murder. However, if it could be established that the had committed mass murder without orders, then they could have been convicted as ''perpetrators'' of mass murder, and hence could have received stiffer sentences, including capital punishment.

Streim postulated that the existence of an early comprehensive order was a fabrication created for use in Ohlendorf's defence. This theory is now widely accepted by historians. Longerich notes that most orders received by the leaders—especially when they were being ordered to carry out criminal activities—were vague, and couched in terminology that had a specific meaning for members of the regime. Leaders were given briefings about the need to be "severe" and "firm"; all Jews were to be viewed as potential enemies that had to be dealt with ruthlessly. British historian Sir

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum article on

The Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team {{Authority control Military units and formations of Germany in World War II The Holocaust in Ukraine The Holocaust in Latvia The Holocaust in Lithuania The Holocaust in Estonia The Holocaust in Russia The Holocaust in Belarus The Holocaust in Poland Holocaust terminology Gestapo Reinhard Heydrich Reich Security Main Office Police of Nazi Germany

death squad

A death squad is an armed group whose primary activity is carrying out extrajudicial killings or forced disappearances as part of political repression, genocide, ethnic cleansing, or revolutionary terror. Except in rare cases in which they are ...

s of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

(1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

. The had an integral role in the implementation of the so-called "Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

to the Jewish question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

" () in territories conquered by Nazi Germany, and were involved in the murder of much of the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

and cultural elite of Poland, including members of the Catholic priesthood

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers only ...

. Almost all of the people they murdered were civilians, beginning with the intelligentsia and swiftly progressing to Soviet political commissars, Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

s, and Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sig ...

, as well as actual or alleged partisans throughout Eastern Europe.

Under the direction of Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

and the supervision of SS- Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

, the operated in territories occupied by the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

(German armed forces) following the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

in September 1939 and the invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

in June 1941. The worked hand-in-hand with the Order Police battalions

The Order Police battalions were militarised formations of the German Order Police (uniformed police) during the Nazi era. During World War II, they were subordinated to the SS and deployed in German-occupied areas, specifically the Army Group ...

on the Eastern Front to carry out operations ranging from the murder of a few people to operations which lasted over two or more days, such as the massacre at Babi Yar

Babi Yar (russian: Ба́бий Яр) or Babyn Yar ( uk, Бабин Яр) is a ravine in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv and a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany's forces during its campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. The fi ...

with 33,771 Jews murdered in two days, and the Rumbula massacre

The Rumbula massacre is a collective term for incidents on November 30 and December 8, 1941, in which about 25,000 Jews were murdered in or on the way to Rumbula forest near Riga, Latvia, during the Holocaust. Except for the Babi Yar massacre in U ...

(with about 25,000 Jews murdered in two days of shooting). As ordered by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, the ''Wehrmacht'' cooperated with the , providing logistical support for their operations, and participated in the mass murders. Historian Raul Hilberg

Raul Hilberg (June 2, 1926 – August 4, 2007) was a Jewish Austrian-born American political scientist and historian. He was widely considered to be the preeminent scholar on the Holocaust. Christopher R. Browning has called him the founding fath ...

estimates that between 1941 and 1945 the , related agencies, and foreign auxiliary personnel murdered more than two million people, including 1.3 million of the 5.5 to 6 million Jews murdered during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

.

After the close of World War II, 24 senior leaders of the were prosecuted in the Einsatzgruppen trial in 1947–48, charged with crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

and war crimes. Fourteen death sentences and two life sentences were handed out. However, only four of these death sentences were carried out. Four additional leaders were later tried and executed by other nations.

Formation and Aktion T4

The were formed under the direction of SS-Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

and operated by the (SS) before and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The had their origins in the ad hoc formed by Heydrich to secure government buildings and documents following the in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

in March 1938. Originally part of the (Security Police; SiPo), two units of were stationed in the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

in October 1938. When military action turned out not to be necessary due to the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

, the were assigned to confiscate government papers and police documents. They also secured government buildings, questioned senior civil servants, and arrested as many as 10,000 Czech communists and German citizens. From September 1939, the (Reich Security Main Office; RSHA) had overall command of the .

As part of the drive by the Nazi regime to remove so-called "undesirable" elements from the German population, from September to December 1939 the and others took part in Action T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of ...

, a program of systematic murder of persons with physical and mental disabilities and patients of psychiatric hospitals. Aktion T4 mainly took place from 1939 to 1941, but the murders continued until the end of the war. Initially the victims were shot by the and others, but gas chamber

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

Histor ...

s were put into use by spring 1940.

Invasion of Poland

In response to

In response to Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's plan to invade Poland on 1 September 1939, Heydrich re-formed the to travel in the wake of the German armies. Membership at this point was drawn from the SS, the (Security Service; SD), the police, and the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

. Heydrich placed SS- Werner Best

Karl Rudolf Werner Best (10 July 1903 – 23 June 1989) was a German jurist, police chief, SS-''Obergruppenführer'', Nazi Party leader, and theoretician from Darmstadt. He was the first chief of Department 1 of the Gestapo, Nazi Germany's secret ...

in command, who assigned to choose personnel for the task forces and their subgroups, called , from among educated people with military experience and a strong ideological commitment to Nazism. Some had previously been members of paramilitary groups such as the . Heydrich instructed Wagner in meetings in late July that the should undertake their operations in cooperation with the (Order Police; Orpo) and military commanders in the area. Army intelligence was in constant contact with to coordinate their activities with other units.

Initially numbering 2,700 men (and ultimately 4,250 in Poland), the 's mission was to murder members of the Polish leadership most clearly identified with Polish national identity: the intelligentsia, members of the clergy, teachers, and members of the nobility. As stated by Hitler: "... there must be no Polish leaders; where Polish leaders exist they must be killed, however harsh that sounds". SS- Lothar Beutel

Lothar Beutel (6 May 1902 – 16 May 1986) was a German pharmacist by profession and Schutzstaffel (SS) officer in World War II serving on behalf of the Sicherheitsdienst branch of the SS.

Biography

Born in Leipzig in 1902, Beutel served as a vol ...

, commander of IV, later testified that Heydrich gave the order for these murders at a series of meetings in mid-August. The lists of people to be murderedhad been drawn up by the SS as early as May 1939, using dossiers collected by the SD from 1936 forward. The performed these murders with the support of the , a paramilitary group consisting of ethnic Germans living in Poland. Members of the SS, the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

, and the also shot civilians during the Polish campaign. Approximately 65,000 civilians were murdered by the end of 1939. In addition to leaders of Polish society, they murdered Jews, prostitutes, Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sig ...

, and the mentally ill. Psychiatric patients in Poland were initially murdered by shooting, but by spring 1941 gas van

A gas van or gas wagon (russian: душегубка, ''dushegubka'', literally "soul killer"; german: Gaswagen) was a truck reequipped as a mobile gas chamber. During the World War II Holocaust, Nazi Germany developed and used gas vans on a large ...

s were widely used.

Seven of battalion strength (around 500 men) operated in Poland. Each was subdivided into five of company strength (around 100 men).

* I, commanded by SS- Bruno Streckenbach

Bruno Streckenbach (7 February 1902 – 28 October 1977) was a German SS functionary during the Nazi era. He was the head of Administration and Personnel Department of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA). Streckenbach was responsible for many ...

, acted with 14th Army

* II, SS- Emanuel Schäfer, acted with 10th Army

* III, SS- Herbert Fischer

Herbert Fischer (born 16 April 1951 in Trebnitz) is a former East German slalom canoeist who competed in the 1970s. He won a gold medal in the C-2 team event at the 1975 in Skopje.

Fischer also finished 18th in the C-2 event at the 1972 Summe ...

, acted with 8th Army

* IV, SS- Lothar Beutel

Lothar Beutel (6 May 1902 – 16 May 1986) was a German pharmacist by profession and Schutzstaffel (SS) officer in World War II serving on behalf of the Sicherheitsdienst branch of the SS.

Biography

Born in Leipzig in 1902, Beutel served as a vol ...

, acted with 4th Army

* V, SS- Ernst Damzog

Ernst Damzog (30 October 1882 – 24 July 1945) was a German policeman, who was a member of the SS of Nazi Germany and served in the Gestapo. He was responsible for the mass murder of Poles and Jews committed in the territory of occupied Polan ...

, acted with 3rd Army

* VI, SS- Erich Naumann

Erich Naumann (29 April 1905 – 7 June 1951) was an SS-Brigadeführer, member of the SD, and a convicted war criminal. Naumann had a key role in the Holocaust in Eastern Europe as the commander of Einsatzgruppe VI and the commander of Einsat ...

, acted in Wielkopolska

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city ...

* VII, SS- Udo von Woyrsch

Udo Gustav Wilhelm Egon von Woyrsch (24 July 1895 – 14 January 1983) was a high-ranking SS official in Nazi Germany who participated in implementation of the regime's racial policies during World War II.

First World War

From early 1914 ...

and SS- Otto Rasch

Emil Otto Rasch (7 December 1891 – 1 November 1948) was a high-ranking German Nazi official and Holocaust perpetrator, who commanded Einsatzgruppe C in northern and central Ukraine until October 1941. After World War II, Rasch was indicted for ...

, acted in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located ...

and Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia, Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia ( pl, Śląsk Cieszyński ; cs, Těšínské Slezsko or ; german: Teschener Schlesien or ) is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered on the towns of Cieszyn and Český Tě ...

Though they were formally under the command of the army, the received their orders from Heydrich and for the most part acted independently of the army. Many senior army officers were only too glad to leave these genocidal actions to the task forces, as the murders violated the rules of warfare as set down in the Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

. However, Hitler had decreed that the army would have to tolerate and even offer logistical support to the when it was tactically possible to do so. Some army commanders complained about unauthorised shootings, looting, and rapes committed by members of the and the , to little effect. For example, when Johannes Blaskowitz

Johannes Albrecht Blaskowitz (10 July 1883 – 5 February 1948) was a German ''Generaloberst'' during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. After joining the Imperial German Army in 1 ...

sent a memorandum of complaint to Hitler about the atrocities, Hitler dismissed his concerns as "childish", and Blaskowitz was relieved of his post in May 1940. He continued to serve in the army but never received promotion to field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

.

The final task of the in Poland was to round up the remaining Jews and concentrate them in ghettos

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

within major cities with good railway connections. The intention was to eventually remove all the Jews from Poland, but at this point their final destination had not yet been determined. Together, the ''Wehrmacht'' and the also drove tens of thousands of Jews eastward into Soviet-controlled territory.

Preparations for Operation Barbarossa

On 13 March 1941, in the lead-up toOperation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the planned invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler dictated his "Guidelines in Special Spheres re: Directive No. 21 (Operation Barbarossa)". Sub-paragraph B specified that Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

would be given "special tasks" on direct orders from the Führer, which he would carry out independently. This directive was intended to prevent friction between the ''Wehrmacht'' and the SS in the upcoming offensive. Hitler also specified that criminal acts against civilians perpetrated by members of the ''Wehrmacht'' during the upcoming campaign would not be prosecuted in the military courts, and thus would go unpunished.

In a speech to his leading generals on 30 March 1941, Hitler described his envisioned war against the Soviet Union. General Franz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres, Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and i ...

, the Army's Chief of Staff, described the speech:

Though General Halder did not record any mention of Jews, German historian Andreas Hillgruber

Andreas Fritz Hillgruber (18 January 1925 – 8 May 1989) was a conservative German historian who was influential as a military and diplomatic historian who played a leading role in the ''Historikerstreit'' of the 1980s. In his controversial book ...

argued that because of Hitler's frequent contemporary statements about the coming war of annihilation against "Judeo-Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revo ...

", his generals would have understood Hitler's call for the destruction of the Soviet Union as also comprising a call for the destruction of its Jewish population. The genocide was often described using euphemisms such as "special tasks" and "executive measures"; victims were often described as having been shot while trying to escape. In May 1941, Heydrich verbally passed on the order to murder the Soviet Jews to the SiPo NCO School in Pretzsch, where the commanders of the reorganised were being trained for Operation Barbarossa. In spring 1941, Heydrich and the First Quartermaster of the , General Eduard Wagner

Eduard Wagner (1 April 1894 – 23 July 1944) was a general in the Army of Nazi Germany who served as quartermaster-general in World War II. He had the overall responsibility for security in the Army Group Rear Areas, and thus bore responsibili ...

, successfully completed negotiations for co-operation between the and the German Army to allow the implementation of the "special tasks". Following the Heydrich-Wagner agreement on 28 April 1941, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch

Walther Heinrich Alfred Hermann von Brauchitsch (4 October 1881 – 18 October 1948) was a German field marshal and the Commander-in-Chief (''Oberbefehlshaber'') of the German Army during World War II. Born into an aristocratic military family ...

ordered that when Operation Barbarossa began, all German Army commanders were to immediately identify and register all Jews in occupied areas in the Soviet Union, and fully co-operate with the .

In further meetings held in June 1941 Himmler outlined to top SS leaders the regime's intention to reduce the population of the Soviet Union by 30 million people, not only through direct murder of those considered racially inferior, but by depriving the remainder of food and other necessities of life.

Organisation starting in 1941

For Operation Barbarossa, initially four were created, each numbering 500–990 men to comprise a total force of 3,000. A, B, and C were to be attached to Army Groups North,Centre

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

, and South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

; D was assigned to the 11th Army. The for Special Purposes operated in eastern Poland starting in July 1941. The were under the control of the RSHA, headed by Heydrich and later by his successor, SS- Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 190316 October 1946) was a high-ranking Austrian SS official during the Nazi era and a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and a brief period under Heinrich ...

. Heydrich gave them a mandate to secure the offices and papers of the Soviet state and Communist Party; to liquidate all the higher cadres of the Soviet state; and to instigate and encourage pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s against Jewish populations. The men of the were recruited from the SD, Gestapo, (Kripo), Orpo, and Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

. Each was under the operational control of the Higher SS Police Chiefs in its area of operations. In May 1941, General Wagner and SS- Walter Schellenberg

Walter Friedrich Schellenberg (16 January 1910 – 31 March 1952) was a German SS functionary during the Nazi era. He rose through the ranks of the SS, becoming one of the highest ranking men in the ''Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD) and eventually ass ...

agreed that the in front-line areas were to operate under army command, while the army provided the with all necessary logistical support. Given their main task was defeating the enemy, the army left the pacification of the civilian population to the , who offered support as well as prevented subversion. This did not preclude their participation in acts of violence against civilians, as many members of the ''Wehrmacht'' assisted the in rounding up and murdering Jews of their own accord.

Heydrich acted under orders from Himmler, who supplied security forces on an "as needed" basis to the local SS and Police Leaders. Led by SD, Gestapo, and Kripo officers, included recruits from the Orpo, Security Service and Waffen-SS, augmented by uniformed volunteers from the local auxiliary police force. Each was supplemented with Waffen-SS and Order Police battalions

The Order Police battalions were militarised formations of the German Order Police (uniformed police) during the Nazi era. During World War II, they were subordinated to the SS and deployed in German-occupied areas, specifically the Army Group ...

as well as support personnel such as drivers and radio operators. On average, the Order Police formations were larger and better armed, with heavy machine-gun detachments, which enabled them to carry out operations beyond the capability of the SS. Each death squad

A death squad is an armed group whose primary activity is carrying out extrajudicial killings or forced disappearances as part of political repression, genocide, ethnic cleansing, or revolutionary terror. Except in rare cases in which they are ...

followed an assigned army group as they advanced into the Soviet Union. During the course of their operations, the commanders received assistance from the ''Wehrmacht''. Activities ranged from the murder of targeted groups of individuals named on carefully prepared lists, to joint citywide operations with which lasted for two or more days, such as the massacres at Babi Yar

Babi Yar (russian: Ба́бий Яр) or Babyn Yar ( uk, Бабин Яр) is a ravine in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv and a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany's forces during its campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. The fi ...

, perpetrated by the Police Battalion 45

The Police Battalion 45 (''Polizeibattalion 45'') was a formation of the German Order Police (uniformed police) during the Nazi era. During Operation Barbarossa, it was subordinated to the SS and deployed in German-occupied areas, specifically ...

, and at Rumbula, by Battalion 22, reinforced by local (auxiliary police). The SS brigades, wrote historian Christopher Browning

Christopher Robert Browning (born May 22, 1944) is an American historian who is the professor emeritus of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). A specialist on the Holocaust, Browning is known for his work documenting ...

, were "only the thin cutting edge of German units that became involved in political and racial mass murder."

Many leaders were highly educated; for example, nine of seventeen leaders of A held doctorate degrees. Three were commanded by holders of doctorates, one of whom SS- Otto Rasch

Emil Otto Rasch (7 December 1891 – 1 November 1948) was a high-ranking German Nazi official and Holocaust perpetrator, who commanded Einsatzgruppe C in northern and central Ukraine until October 1941. After World War II, Rasch was indicted for ...

) held a double doctorate.

Additional were created as additional territories were occupied. E operated in Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Fascist It ...

under three commanders, SS- , SS- Günther Herrmann, and lastly SS- Wilhelm Fuchs

Oberführer and Oberst of Police Wilhelm Fuchs (1 September 1898, in Mannheim – 24 January 1947, in Belgrade) was a Nazi Einsatzkommando leader. From April 1941 to January 1942 he commanded Einsatzgruppe Serbia. From 15 September 1943 throu ...

. The unit was subdivided into five located in Vinkovci

Vinkovci () is a city in Slavonia, in the Vukovar-Syrmia County in eastern Croatia. The city's registered population was 28,247 in the 2021 census, the total population of the city was 31,057, making it the largest town of the county. Surrounde ...

, Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its a ...

, Banja Luka

Banja Luka ( sr-Cyrl, Бања Лука, ) or Banjaluka ( sr-Cyrl, Бањалука, ) is the second largest city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the largest city of Republika Srpska. Banja Luka is also the ''de facto'' capital of this entity. I ...

, Knin

Knin (, sr, link=no, Книн, it, link=no, Tenin) is a city in the Šibenik-Knin County of Croatia, located in the Dalmatian hinterland near the source of the river Krka, an important traffic junction on the rail and road routes between Zagr ...

, and Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

. F worked with Army Group South. G operated in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, commanded by SS- . H was assigned to Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

. K and L, under SS- Emanuel Schäfer and SS- Ludwig Hahn

Ludwig Hermann Karl Hahn (23 January 1908 – 10 November 1986) was a German '' SS-Standartenführer'', Nazi official and convicted war criminal. He held numerous positions with the police and security services over the course of his career with ...

, worked alongside 5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

and 6th Panzer Armies during the Ardennes offensive

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

. Hahn had previously been in command of in Greece.

Other and included (operated in Carinthia, on the border between Slovenia and Austria) under SS- Paul Blobel

Paul Blobel (13 August 1894 – 7 June 1951) was a German ''Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD) commander and convicted war criminal who played a leading role in the Holocaust. He organised and executed the Babi Yar massacre, the largest massacre of th ...

, (Yugoslavia) (Luxembourg), (Norway) commanded by SS- Franz Walter Stahlecker, (Yugoslavia) under SS- Wilhelm Fuchs

Oberführer and Oberst of Police Wilhelm Fuchs (1 September 1898, in Mannheim – 24 January 1947, in Belgrade) was a Nazi Einsatzkommando leader. From April 1941 to January 1942 he commanded Einsatzgruppe Serbia. From 15 September 1943 throu ...

and SS- August Meysner, ' (Lithuania, Poland), and (Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

), commanded by SS- Walter Rauff

Walter (Walther) Rauff (19 June 1906 – 14 May 1984) was a mid-ranking SS commander in Nazi Germany. From January 1938, he was an aide of Reinhard Heydrich firstly in the Security Service (''Sicherheitsdienst'' or ''SD''), later in the Reich Se ...

.

Killings in the Soviet Union

After the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the 's main assignment was to kill civilians, as in Poland, but this time its targets specifically includedSoviet Communist Party

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first)Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and Eas ...

s and Jews. In a letter dated 2 July 1941 Heydrich communicated to his SS and Police Leaders that the were to execute all senior and middle ranking Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

officials; all senior and middle ranking members of the central, provincial, and district committees of the Communist Party; extremist and radical Communist Party members; people's commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and Eas ...

s; and Jews in party and government posts. Open-ended instructions were given to execute "other radical elements (saboteurs, propagandists, snipers, assassins, agitators, etc.)." He instructed that any pogroms spontaneously initiated by the population of the occupied territories were to be quietly encouraged.

On 8 July, Heydrich announced that all Jews were to be regarded as partisans, and gave the order for all male Jews between the ages of 15 and 45 to be shot. On 17 July Heydrich ordered that the were to murder all Jewish Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

prisoners of war, plus all Red Army prisoners of war from Georgia and Central Asia, as they too might be Jews. Unlike in Germany, where the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

of 1935 defined as Jewish anyone with at least three Jewish grandparents, the defined as Jewish anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent; in either case, whether or not the person practised the religion was irrelevant. The unit was also assigned to exterminate Romani people and the mentally ill. It was common practice for the to shoot hostages.

As the invasion began, the Germans pursued the fleeing Red Army, leaving a security vacuum. Reports surfaced of Soviet guerrilla activity in the area, with local Jews immediately suspected of collaboration. Heydrich ordered his officers to incite anti-Jewish pogroms in the newly occupied territories. Pogroms, some of which were orchestrated by the , broke out in Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. Within the first few weeks of Operation Barbarossa, 10,000 Jews had been murdered in 40 pogroms, and by the end of 1941 some 60 pogroms had taken place, claiming as many as 24,000 victims. However, Franz Walter Stahlecker

Franz Walter Stahlecker (10 October 1900 – 23 March 1942) was commander of the SS security forces (''Sicherheitspolizei'' (SiPo) and the ''Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD) for the ''Reichskommissariat Ostland'' in 1941–42. Stahlecker commanded ''Eins ...

, commander of A, reported to his superiors in mid-October that the residents of Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

were not spontaneously starting pogroms, and secret assistance by the Germans was required. A similar reticence was noted by B in Russia and Belarus and C in Ukraine; the further east the travelled, the less likely the residents were to be prompted into murdering their Jewish neighbours.

All four main took part in mass shootings from the early days of the war. Initially the targets were adult Jewish men, but by August the net had been widened to include women, children, and the elderly—the entire Jewish population. Initially there was a semblance of legality given to the shootings, with trumped-up charges being read out (arson, sabotage, black marketeering, or refusal to work, for example) and victims being murdered by a firing squad. As this method proved too slow, the began to take their victims out in larger groups and shot them next to, or even inside, mass graves that had been prepared. Some started to use automatic weapons, with survivors being murdered with a pistol shot.

As word of the massacres got out, many Jews fled; in Ukraine, 70 to 90 per cent of the Jews ran away. This was seen by the leader of VI as beneficial, as it would save the regime the costs of deporting the victims further east over the Urals. In other areas the invasion was so successful that the had insufficient forces to immediately murder all the Jews in the conquered territories. A situation report from C in September 1941 noted that not all Jews were members of the Bolshevist apparatus, and suggested that the total elimination of Jewry would have a negative impact on the economy and the food supply. The Nazis began to round their victims up into concentration camps and ghettos and rural districts were for the most part rendered (free of Jews). Jewish councils were set up in major cities and forced labour gangs were established to make use of the Jews as slave labour until they were totally eliminated, a goal that was postponed until 1942.

The used public hangings as a terror tactic against the local population. An B report, dated 9 October 1941, described one such hanging. Due to suspected partisan activity near Demidov, all male residents aged 15 to 55 were put in a camp to be screened. The screening produced seventeen people who were identified as "partisans" and "Communists". Five members of the group were hanged while 400 local residents were assembled to watch; the rest were shot.

All four main took part in mass shootings from the early days of the war. Initially the targets were adult Jewish men, but by August the net had been widened to include women, children, and the elderly—the entire Jewish population. Initially there was a semblance of legality given to the shootings, with trumped-up charges being read out (arson, sabotage, black marketeering, or refusal to work, for example) and victims being murdered by a firing squad. As this method proved too slow, the began to take their victims out in larger groups and shot them next to, or even inside, mass graves that had been prepared. Some started to use automatic weapons, with survivors being murdered with a pistol shot.

As word of the massacres got out, many Jews fled; in Ukraine, 70 to 90 per cent of the Jews ran away. This was seen by the leader of VI as beneficial, as it would save the regime the costs of deporting the victims further east over the Urals. In other areas the invasion was so successful that the had insufficient forces to immediately murder all the Jews in the conquered territories. A situation report from C in September 1941 noted that not all Jews were members of the Bolshevist apparatus, and suggested that the total elimination of Jewry would have a negative impact on the economy and the food supply. The Nazis began to round their victims up into concentration camps and ghettos and rural districts were for the most part rendered (free of Jews). Jewish councils were set up in major cities and forced labour gangs were established to make use of the Jews as slave labour until they were totally eliminated, a goal that was postponed until 1942.

The used public hangings as a terror tactic against the local population. An B report, dated 9 October 1941, described one such hanging. Due to suspected partisan activity near Demidov, all male residents aged 15 to 55 were put in a camp to be screened. The screening produced seventeen people who were identified as "partisans" and "Communists". Five members of the group were hanged while 400 local residents were assembled to watch; the rest were shot.

Babi Yar

The largest mass shooting perpetrated by the took place on 29 and 30 September 1941 at Babi Yar, a ravine northwest ofKyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

city center in Ukraine that had fallen to the Germans on 19 September. The perpetrators included a company of Waffen-SS attached to C under Rasch, members of 4a under SS- Friedrich Jeckeln

Friedrich Jeckeln (2 February 1895 – 3 February 1946) was a German SS commander during the Nazi era. He served as a Higher SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union during World War II. Jeckeln was the commander of one of the largest ...

, and some Ukrainian auxiliary police. The Jews of Kyiv were told to report to a certain street corner on 29 September; anyone who disobeyed would be shot. Since word of massacres in other areas had not yet reached Kyiv and the assembly point was near the train station, they assumed they were being deported. People showed up at the rendezvous point in large numbers, laden with possessions and food for the journey.

After being marched northwest of the city centre, the victims encountered a barbed wire barrier and numerous Ukrainian police and German troops. Thirty or forty people at a time were told to leave their possessions and were escorted through a narrow passageway lined with soldiers brandishing clubs. Anyone who tried to escape was beaten. Soon the victims reached an open area, where they were forced to strip, and then were herded down into the ravine. People were forced to lie down in rows on top of the bodies of other victims, and they were shot in the back of the head or the neck by members of the execution squads.

The murders continued for two days, claiming a total of 33,771 victims. Sand was shovelled and bulldozed over the bodies and the sides of the ravine were dynamited to bring down more material. Anton Heidborn, a member of 4a, later testified that three days later that there were still people alive among the corpses. Heidborn spent the next few days helping smooth out the "millions" of banknotes taken from the victims' possessions. The clothing was taken away, destined to be re-used by German citizens. Jeckeln's troops shot more than 100,000 Jews by the end of October.

Killings in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia

A operated in

A operated in Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (the three Baltic countries which had been occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940–1941). According to its own reports to Himmler, A murdered almost 140,000 people in the five months following the 1941 German invasion: 136,421 Jews, 1,064 Communists, 653 people with mental illnesses, 56 partisans, 44 Poles, five Romani, and one Armenian were reported murdered between 22 June and 25 November 1941.

Upon entering Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

, Lithuania, on 25 June 1941, the released the criminals from the local jail and encouraged them to join the pogrom which was underway. Between 23 and 27 June 1941, 4,000 Jews were murdered on the streets of Kaunas and in nearby open pits and ditches. Particularly active in the Kaunas pogrom was the so-called "Death Dealer of Kaunas", a young man who murdered Jews with a crowbar at the Lietukis Garage before a large crowd that cheered each murder with much applause; he occasionally paused to play the Lithuanian national anthem "Tautiška giesmė

"" (; literally "The National Hymn") is the national anthem of Lithuania, also known by its opening words, "" (official translation of the lyrics: "Lithuania, Our Homeland", literally: "Lithuania, Our Fatherland"), and as "" ("The National Anthem ...

" on his accordion before resuming the murders.

As A advanced into Lithuania, it actively recruited local nationalists and antisemitic groups. In July 1941, local Lithuanian collaborators, pejoratively called "White Armbands" (), joined the massacres. A pogrom in the Latvian capital Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

in early July 1941 killed 400 Jews. Latvian nationalist Viktors Arājs

Viktors Arājs (13 January 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a Latvian/Baltic German collaborator and Nazi SS SD officer who took part in the Holocaust during the German occupation of Latvia and Belarus as the leader of the Arajs Kommando. The Ara ...

and his supporters undertook a campaign of arson against synagogues. On 2 July, A commander Stahlecker appointed Arājs to head the , a of about 300 men, mostly university students. Together, A and the murdered 2,300 Jews in Riga on 6–7 July. Within six months, Arājs and collaborators would murder about half of Latvia's Jewish population.

Local officials, the , and the (Auxiliary Police) played a key role in rounding up and massacring local Jews in German-occupied Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. These groups also helped the and other killing units to identify Jews. For example, in Latvia, the , consisting of auxiliary police organised by the Germans and recruited from former Latvian army and police officers, ex-, members of the Pērkonkrusts

Pērkonkrusts (, "Thunder Cross") was a Latvian ultranationalist, anti-German, anti-Slavic, and antisemitic political party founded in 1933 by Gustavs Celmiņš, borrowing elements of German nationalism—but being unsympathetic to Nazism at ...

, and university students, assisted in the murder of Latvia's Jewish citizens. Similar units were created elsewhere, and provided much of the manpower for the Holocaust in Eastern Europe.

With the creation of units such as the in Latvia and the in Lithuania, the attacks changed from the spontaneous mob violence of the pogroms to more systematic massacres. With extensive local help, A was the first to attempt to systematically exterminate all the Jews in its area. Latvian historian Modris Eksteins Modris Eksteins ( lv, Modris Ekšteins; born December 13, 1943) is a Latvian Canadian historian with a special interest in German history and modern culture.

Born in Riga, Latvia, his works include ''Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of ...

wrote:

In late 1941, the settled into headquarters in Kaunas, Riga, and Tallinn. A grew less mobile and faced problems because of its small size. The Germans relied increasingly on the Latvian and similar groups to perform massacres of Jews.

Such extensive and enthusiastic collaboration with the has been attributed to several factors. Since the

In late 1941, the settled into headquarters in Kaunas, Riga, and Tallinn. A grew less mobile and faced problems because of its small size. The Germans relied increasingly on the Latvian and similar groups to perform massacres of Jews.

Such extensive and enthusiastic collaboration with the has been attributed to several factors. Since the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, the and other borderlands had experienced a political culture of violence. The 1940–1941 Soviet occupation had been profoundly traumatic for residents of the Baltic states and areas that had been part of Poland until 1939; the population was brutalised and terrorised, and the existing familiar structures of society were destroyed.

Historian Erich Haberer

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, or Eirik is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Norse languag ...

has suggested that many survived and made sense of the "totalitarian atomization" of society by seeking conformity with communism. As a result, by the time of the German invasion in 1941, many had come to see conformity with a totalitarian regime as socially acceptable behaviour; thus, people simply transferred their allegiance to the German regime when it arrived. Some who had collaborated with the Soviet regime sought to divert attention from themselves by naming Jews as collaborators and murdering them.

Rumbula

In November 1941 Himmler was dissatisfied with the pace of the exterminations in Latvia, as he intended to move Jews from Germany into the area. He assigned SS- Jeckeln, one of the perpetrators of the Babi Yar massacre, to liquidate the Riga ghetto. Jeckeln selected a site about southeast of Riga near the Rumbula railway station, and had 300 Russian prisoners of war prepare the site by digging pits in which to bury the victims. Jeckeln organised around 1,700 men, including 300 members of the , 50 German SD men, and 50 Latvian guards, most of whom had already participated in mass-murdering of civilians. These troops were supplemented by Latvians, including members of the Riga city police, battalion police, and ghetto guards. Around 1,500 able-bodied Jews would be spared execution so their slave labour could be exploited; a thousand men were relocated to a fenced-off area within the ghetto and 500 women were temporarily housed in a prison and later moved to a separate nearby ghetto, where they were put to work mending uniforms. Although Rumbula was on the rail line, Jeckeln decided that the victims should travel on foot from Riga to the execution ground. Trucks and buses were arranged to carry children and the elderly. The victims were told that they were being relocated, and were advised to bring up to of possessions. The first day of executions, 30 November 1941, began with the perpetrators rousing and assembling the victims at 4:00 am. The victims were moved in columns of a thousand people toward the execution ground. As they walked, some SS men went up and down the line, shooting people who could not keep up the pace or who tried to run away or rest. When the columns neared the prepared execution site, the victims were driven some from the road into the forest, where any possessions that had not yet been abandoned were seized. Here the victims were split into groups of fifty and taken deeper into the forest, near the pits, where they were ordered to strip. The victims were driven into the prepared trenches, made to lie down, and shot in the head or the back of the neck by members of Jeckeln's bodyguard. Around 13,000 Jews from Riga were murdered at the pits that day, along with a thousand Jews from Berlin who had just arrived by train. On the second day of the operation, 8 December 1941, the remaining 10,000 Jews of Riga were murdered in the same way. About a thousand were murdered on the streets of the city or on the way to the site, bringing the total number of deaths for the two-day extermination to 25,000 people. For his part in organising the massacre, Jeckeln was promoted to Leader of the SS Upper Section,Ostland

The Reichskommissariat Ostland (RKO) was established by Nazi Germany in 1941 during World War II. It became the civilian occupation regime in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the western part of Byelorussian SSR. German planning documents ini ...

.

Second sweep

B, C, and D did not immediately follow A's example in systematically murdering all Jews in their areas. The commanders, with the exception of A's Stahlecker, were of the opinion by the fall of 1941 that it was impossible to murder the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union in one sweep, and thought the murders should stop. An report dated 17 September advised that the Germans would be better off using any skilled Jews as labourers rather than shooting them. Also, in some areas poor weather and a lack of transportation led to a slowdown in deportations of Jews from points further west. Thus, an interval passed between the first round of massacres in summer and fall, and what American historian

B, C, and D did not immediately follow A's example in systematically murdering all Jews in their areas. The commanders, with the exception of A's Stahlecker, were of the opinion by the fall of 1941 that it was impossible to murder the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union in one sweep, and thought the murders should stop. An report dated 17 September advised that the Germans would be better off using any skilled Jews as labourers rather than shooting them. Also, in some areas poor weather and a lack of transportation led to a slowdown in deportations of Jews from points further west. Thus, an interval passed between the first round of massacres in summer and fall, and what American historian Raul Hilberg

Raul Hilberg (June 2, 1926 – August 4, 2007) was a Jewish Austrian-born American political scientist and historian. He was widely considered to be the preeminent scholar on the Holocaust. Christopher R. Browning has called him the founding fath ...

called the second sweep, which started in December 1941 and lasted into the summer of 1942. During the interval, the surviving Jews were forced into ghettos.

A had already murdered almost all Jews in its area, so it shifted its operations into Belarus to assist B. In Dnepropetrovsk

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

in February 1942, D reduced the city's Jewish population from 30,000 to 702 over the course of four days. The German Order Police and local collaborators provided the extra manpower needed to perform all the shootings. Haberer wrote that, as in the Baltic states, the Germans could not have murdered so many Jews so quickly without local help. He points out that the ratio of Order Police to auxiliaries was 1 to 10 in both Ukraine and Belarus. In rural areas the proportion was 1 to 20. This meant that most Ukrainian and Belarusian Jews were murdered by fellow Ukrainians and Belarusians commanded by German officers rather than by Germans.

The second wave of exterminations in the Soviet Union met with armed resistance in some areas, though the chance of success was poor. Weapons were typically primitive or home-made. Communications were impossible between ghettos in various cities, so there was no way to create a unified strategy. Few in the ghetto leadership supported resistance for fear of reprisals on the ghetto residents. Mass break-outs were sometimes attempted, though survival in the forest was nearly impossible due to the lack of food and the fact that escapees were often tracked down and murdered.

Transition to gassing

After a time, Himmler found that the killing methods used by the were inefficient: they were costly, demoralising for the troops, and sometimes did not kill the victims quickly enough. Many of the troops found the massacres to be difficult if not impossible to perform. Some of the perpetrators suffered physical and mental health problems, and many turned to drink. As much as possible, the leaders militarized the genocide. The historian Christian Ingrao notes an attempt was made to make the shootings a collective act without individual responsibility. Framing the shootings in this way was not psychologically sufficient for every perpetrator to feel absolved of guilt. Browning notes three categories of potential perpetrators: those who were eager to participate right from the start, those who participated in spite of moral qualms because they were ordered to do so, and a significant minority who refused to take part. A few men spontaneously became excessively brutal in their killing methods and their zeal for the task. Commander of D, SS-

After a time, Himmler found that the killing methods used by the were inefficient: they were costly, demoralising for the troops, and sometimes did not kill the victims quickly enough. Many of the troops found the massacres to be difficult if not impossible to perform. Some of the perpetrators suffered physical and mental health problems, and many turned to drink. As much as possible, the leaders militarized the genocide. The historian Christian Ingrao notes an attempt was made to make the shootings a collective act without individual responsibility. Framing the shootings in this way was not psychologically sufficient for every perpetrator to feel absolved of guilt. Browning notes three categories of potential perpetrators: those who were eager to participate right from the start, those who participated in spite of moral qualms because they were ordered to do so, and a significant minority who refused to take part. A few men spontaneously became excessively brutal in their killing methods and their zeal for the task. Commander of D, SS- Otto Ohlendorf

Otto Ohlendorf (; 4 February 1907 – 7 June 1951) was a German SS functionary and Holocaust perpetrator during the Nazi era. An economist by education, he was head of the (SD) Inland, responsible for intelligence and security within Germ ...

, particularly noted this propensity towards excess, and ordered that any man who was too eager to participate or too brutal should not perform any further executions.

During a visit to Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the admi ...

in August 1941, Himmler witnessed an mass execution first-hand and concluded that shooting Jews was too stressful for his men. By November he made arrangements for any SS men suffering ill health from having participated in executions to be provided with rest and mental health care. He also decided a transition should be made to gassing the victims, especially the women and children, and ordered the recruitment of expendable native auxiliaries who could assist with the murders. Gas vans, which had been used previously to murder mental patients, began to see service by all four main from 1942. However, the gas vans were not popular with the , because removing the dead bodies from the van and burying them was a horrible ordeal. Prisoners or auxiliaries were often assigned to do this task so as to spare the SS men the trauma. Some of the early mass murders at extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s used carbon monoxide fumes produced by diesel engines, similar to the method used in gas vans, but by as early as September 1941 experiments were begun at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

using Zyklon B

Zyklon B (; translated Cyclone B) was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such ...

, a cyanide-based pesticide gas.

Plans for the total eradication of the Jewish population of Europe—eleven million people—were formalised at the Wannsee Conference, held on 20 January 1942. Some would be worked to death, and the rest would be murdered in the implementation of the Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

of the Jewish question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

(german: link=no, Die Endlösung der Judenfrage). Permanent killing centres at Auschwitz, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, a ...

, Sobibor

Sobibor (, Polish: ) was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Reinhard. It was located in the forest near the village of Żłobek Duży in the General Government region of German-occupied Poland.

As an ...

, Treblinka

Treblinka () was an extermination camp, built and operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II. It was in a forest north-east of Warsaw, south of the village of Treblinka in what is now the Masovian Voivodeship. The camp ...

, and other Nazi extermination camps replaced mobile death squads as the primary method of mass-murder. The remained active, however, and were put to work fighting partisans, particularly in Belarus.

After the fall of Stalingrad in February 1943, Himmler realised that Germany would likely lose the war, and ordered the formation of a special task force, ''Sonderaktion 1005