Edward Thomas Daniell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Thomas Daniell (6 June 180424 September 1842) was an English artist known for his

Edward Daniell was associated with the

Edward Daniell was associated with the

Sir Thomas purchased land and slaves in the

Sir Thomas purchased land and slaves in the

The route Daniell took during his eighteen months on the Continent is revealed by the order of his paintings. His travels through Switzerland are reminiscent of those of the artist

The route Daniell took during his eighteen months on the Continent is revealed by the order of his paintings. His travels through Switzerland are reminiscent of those of the artist

On 2 October 1832 Daniell was

On 2 October 1832 Daniell was

Daniell was in Athens by the end of the year, and sailed to

Daniell was in Athens by the end of the year, and sailed to  In March 1842, Fellows left for London on HMS ''Beacon'', in order to obtain bigger ships for transporting the antiquities back to England. Daniell travelled to

In March 1842, Fellows left for London on HMS ''Beacon'', in order to obtain bigger ships for transporting the antiquities back to England. Daniell travelled to

He stayed at Purdie's residence to recuperate, and wrote to Forbes and Spratt describing his discoveries at Apollonia and Lyrbe. Before he had fully recovered he left the city to undertake a solitary expedition to

He stayed at Purdie's residence to recuperate, and wrote to Forbes and Spratt describing his discoveries at Apollonia and Lyrbe. Before he had fully recovered he left the city to undertake a solitary expedition to

Many of Daniell's etchings were printed in Norwich by Henry Ninham, who lived a short distance from Daniell's house on St. Giles Street. His friendships with Ninham and Joseph Stannard may have begun at school.

Daniell was an active patrons of the arts and held regular dinner parties and other gatherings at his London home. It became a resort of painters including John Linnell, David Roberts,

Many of Daniell's etchings were printed in Norwich by Henry Ninham, who lived a short distance from Daniell's house on St. Giles Street. His friendships with Ninham and Joseph Stannard may have begun at school.

Daniell was an active patrons of the arts and held regular dinner parties and other gatherings at his London home. It became a resort of painters including John Linnell, David Roberts,

Daniell first met the artist John Linnell while he was at Oxford. Linnell asked him to promote the sale of '' Illustrations of the Book of Job'' by the artist and poet

Daniell first met the artist John Linnell while he was at Oxford. Linnell asked him to promote the sale of '' Illustrations of the Book of Job'' by the artist and poet

Daniell's friendship with Turner, whom he first met in London, was short but intense. He was a regular guest at Daniell's gatherings and dinner parties, and they quickly became close friends. He was considered by Daniell's circle of artists to be their doyen. Beecheno, in his '': a memoir'', recalled that on one occasion Turner was asked his opinion of Daniell's work. "Very clever, Sir, very clever" was the great master's dictum, delivered in his usual blunt way." Elizabeth Rigby wrote of Daniell:

Roberts wrote that Daniell "adored Turner, when I and others doubted, and taught me to see and to distinguish his beauties over that of others... the old man really had a fond and personal regard for this young clergyman, which I doubt he ever evinced for the other."

He may have helped Turner spiritually. His biographer James Hamilton writes that he was "able to supply spiritual comfort that Turner required to help him fill the holes left by the deaths of his father and friends and to ease the fears of a naturally reflective man approaching old age". The old artist is known to have mourned Daniell's early death deeply, saying repeatedly to Roberts that he would never form such a friendship again. Roberts later wrote: "Poor Daniell, like Wilkie, went to Syria after me, but neither returned. Had Daniell returned to England, I have reason to know, from Turner's own mouth, he would have been entrusted with his law affairs."

Turner's romantic style is approached by Daniell's watercolours painted during his travels abroad. Coincidentally, Turner toured Switzerland in 1829, visiting sites Daniell had earlier depicted.

Daniell's friendship with Turner, whom he first met in London, was short but intense. He was a regular guest at Daniell's gatherings and dinner parties, and they quickly became close friends. He was considered by Daniell's circle of artists to be their doyen. Beecheno, in his '': a memoir'', recalled that on one occasion Turner was asked his opinion of Daniell's work. "Very clever, Sir, very clever" was the great master's dictum, delivered in his usual blunt way." Elizabeth Rigby wrote of Daniell:

Roberts wrote that Daniell "adored Turner, when I and others doubted, and taught me to see and to distinguish his beauties over that of others... the old man really had a fond and personal regard for this young clergyman, which I doubt he ever evinced for the other."

He may have helped Turner spiritually. His biographer James Hamilton writes that he was "able to supply spiritual comfort that Turner required to help him fill the holes left by the deaths of his father and friends and to ease the fears of a naturally reflective man approaching old age". The old artist is known to have mourned Daniell's early death deeply, saying repeatedly to Roberts that he would never form such a friendship again. Roberts later wrote: "Poor Daniell, like Wilkie, went to Syria after me, but neither returned. Had Daniell returned to England, I have reason to know, from Turner's own mouth, he would have been entrusted with his law affairs."

Turner's romantic style is approached by Daniell's watercolours painted during his travels abroad. Coincidentally, Turner toured Switzerland in 1829, visiting sites Daniell had earlier depicted.

As the son of a

As the son of a

Daniell's oil paintings generally depicted subjects encountered on his continental travels, and he showed them at annual exhibitions in London. He was an honorary exhibitor with the

Daniell's oil paintings generally depicted subjects encountered on his continental travels, and he showed them at annual exhibitions in London. He was an honorary exhibitor with the

File:E.T. Daniell - Burgh Bridge near Aylsham.jpg, alt=watercolour of Burgh Bridge, ''Burgh Bridge near Aylsham'' (1827), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Kobban.jpg, alt=watercolour of Kobban, ''Kobban'' (1841), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Near Kalabshee 1841.jpg, alt=watercolour of Kalabsha, ''Near Kalabshee 1841'', Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Interior of Convent, Mount Sinai.jpg, alt=watercolour of St Catherine's Convent, Mount Sinai, ''Interior of Convent, Mount Sinai'' (1841), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E. T. Daniell - Termessus, looking SE.jpg, alt=watercolour of Termessus, ''Termessus, looking SE'' (1842), British Museum

File:E.T. Daniell - Stadium of Cibyra.jpg, alt=watercolour of Cibyra, ''Stadium of Cibyra'' (1842), British Museum

Martin Hardie asserted: "If only more proofs from his fine plates been made available for collectors and museums he would be more readily placed among the great etchers of the world." Miklos Rajnai, a Keeper of Art at Norwich Castle Museum, compared Daniell's skill as an etcher with John Crome and John Sell Cotman. The British art historian Arthur Hind said the etchings "anticipated far more than nearly anything of Crome or Cotman the modern revival of etching".

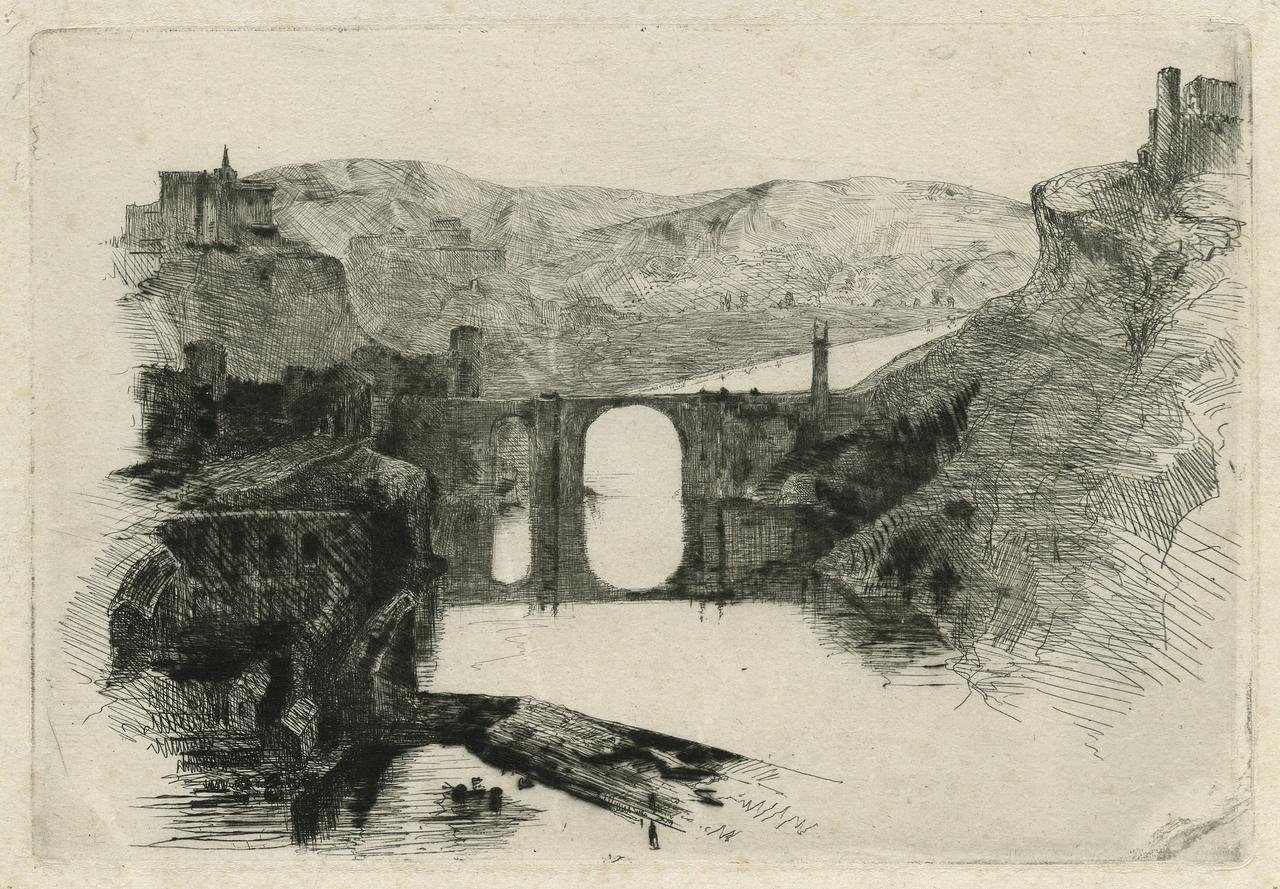

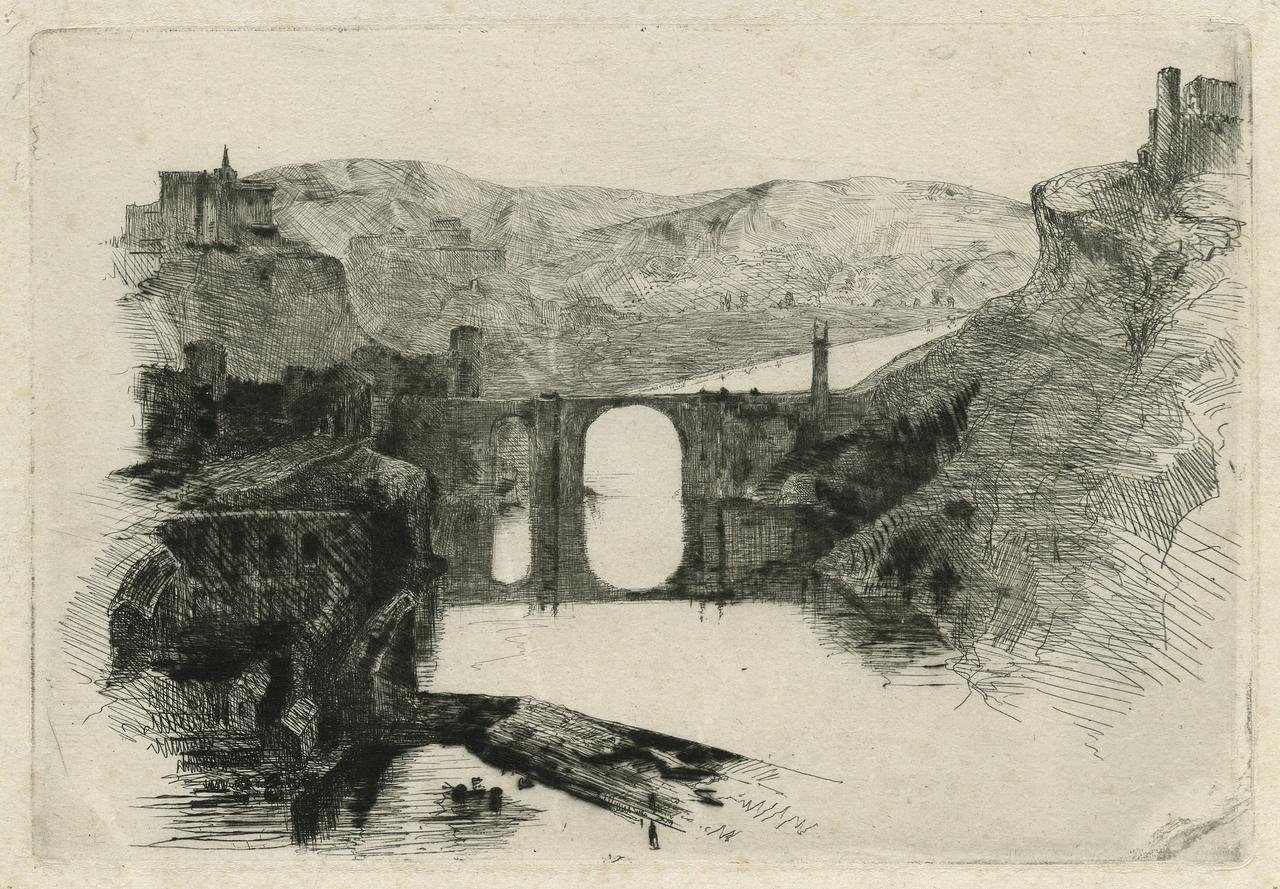

Daniell's first attempts at etching were made with Joseph Stannard in February 1824. The style of his earliest works were influenced by Stannard, but he later became more affected by the works of J. M. W. Turner. Three distinct groups of etchings can be identified: those produced in Norfolk, including ''Flordon Bridge'', his masterpiece from his early years; a more grandiose group of etchings made during his tours of

Martin Hardie asserted: "If only more proofs from his fine plates been made available for collectors and museums he would be more readily placed among the great etchers of the world." Miklos Rajnai, a Keeper of Art at Norwich Castle Museum, compared Daniell's skill as an etcher with John Crome and John Sell Cotman. The British art historian Arthur Hind said the etchings "anticipated far more than nearly anything of Crome or Cotman the modern revival of etching".

Daniell's first attempts at etching were made with Joseph Stannard in February 1824. The style of his earliest works were influenced by Stannard, but he later became more affected by the works of J. M. W. Turner. Three distinct groups of etchings can be identified: those produced in Norfolk, including ''Flordon Bridge'', his masterpiece from his early years; a more grandiose group of etchings made during his tours of

File:E.T. Daniell - Church Tower and Trees.jpg , alt=etching: Church , ''Church Tower and Trees'' (1824), Norfolk Museums Collections. This work is probably Daniell's first etching.

File:E.T. Daniell - River Scene with Man fishing from Boat.jpg, alt=etching: Man fishing , ''River Scene with Man fishing from a Boat'' (1824), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Flordon Bridge.jpg , alt=etching: Flordon Bridge , ''Flordon Bridge'' (1825), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Burgh Bridge.jpg, alt=etching: Burgh Bridge , ''Aylsham Bridge, or Burgh Bridge'' (1827), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Castle of Dunolly, Oban.jpg, alt=etching: Castle of Dunolly, ''Castle of Dunolly, Oban'' (), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Ruin at Rome.jpg, alt=etching: ruin, ''Ruin at Rome'' (), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Whitlingham Lane by Trowse.jpg , alt=etching: Whitlingham Lane by Trowse , ''Whitlingham Lane by Trowse'' (), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - At Banham, Norfolk.jpg, alt=etching: Banham , ''At Banham, Norfolk'' (), Norfolk Museums Collections

File:E.T. Daniell - Norwich Castle - before the restoration of 1834.jpg, alt=etching: Norwich Castle, ''Norwich Castlebefore the restoration of 1834'', Norfolk Museums Collections

etching

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

s and the landscape painting

Landscape painting, also known as landscape art, is the depiction of natural scenery such as mountains, valleys, trees, rivers, and forests, especially where the main subject is a wide view—with its elements arranged into a coherent compos ...

s he made during an expedition to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, including Lycia

Lycia (Lycian language, Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean ...

, part of modern-day Turkey. He is associated with the Norwich School of painters

The Norwich School of painters was the first provincial art movement established in Britain, active in the early 19th century. Artists of the school were inspired by the natural environment of the Norfolk landscape and owed some influence to the wo ...

, a group of artists connected by location and personal and professional relationships, who were mainly inspired by the Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

countryside.

Born in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

to wealthy parents, Daniell grew up and was educated in Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, where he was taught art by John Crome

John Crome (22 December 176822 April 1821), once known as Old Crome to distinguish him from his artist son John Berney Crome, was an English landscape painter of the Romantic era, one of the principal artists and founding members of the Norw ...

and Joseph Stannard

Joseph Stannard (13 September 1797 7 December 1830) was an English marine, landscape and portrait painter. He was a talented and prominent member of the Norwich School of painters.

After attending the Norwich Grammar School, his parents pa ...

. After graduating in classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

at Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

, in 1828, he was ordained as a curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

at Banham in 1832 and appointed to a curacy at St. Mark's Church, London, in 1834. He became a patron of the arts, and an influential friend of the artist John Linnell

John Sidney Linnell ( ; born June 12, 1959) is an American musician, known primarily as one half of the Brooklyn-based alternative rock band They Might Be Giants with John Flansburgh, which was formed in 1982. In addition to singing and songwri ...

. In 1840, after resigning his curacy and leaving England for the Middle East, he travelled to Egypt, Palestine and Syria, and joined the explorer Sir Charles Fellows

Sir Charles Fellows (31 August 1799 – 8 November 1860) was a British archaeologist and explorer, known for his numerous expeditions in what is present-day Turkey.

Biography

Charles Fellows was born at High Pavement, Nottingham on 31 August ...

's archaeological expedition in Lycia

Lycia (Lycian language, Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean ...

(now in Turkey) as an illustrator. He contracted malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

there and reached Adalia (now known as Antalya

Antalya () is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, fifth-most populous city in Turkey as well as the capital of Antalya Province. Located on Anatolia's southwest coast bordered by the Taurus Mountains, Antalya is the largest Turkish cit ...

) intending to recuperate, but died from a second attack of the disease.

He normally used a small number of colours for his watercolour paintings, mainly sepia

Sepia may refer to:

Biology

* ''Sepia'' (genus), a genus of cuttlefish

Color

* Sepia (color), a reddish-brown color

* Sepia tone, a photography technique

Music

* ''Sepia'', a 2001 album by Coco Mbassi

* ''Sepia'' (album) by Yu Takahashi

* " ...

, ultramarine

Ultramarine is a deep blue color pigment which was originally made by grinding lapis lazuli into a powder. The name comes from the Latin ''ultramarinus'', literally 'beyond the sea', because the pigment was imported into Europe from mines in Afgh ...

, and gamboge

Gamboge ( , ) is a partially transparent deep saffron to mustard yellow pigment.Other forms and spellings are: cambodia, cambogium, camboge, cambugium, gambaugium, gambogia, gambozia, gamboidea, gambogium, gumbouge, gambouge, gamboge, gambooge, g ...

. The distinctive style of his watercolours was influenced in part by Crome, and John Sell Cotman

John Sell Cotman (16 May 1782 – 24 July 1842) was an English marine and landscape painter, etcher, illustrator, author and a leading member of the Norwich School of painters.

Born in Norwich, the son of a silk merchant and lace dealer, Cot ...

. As an etcher he was unsurpassed by the other Norwich artists in the use of drypoint

Drypoint is a printmaking technique of the intaglio (printmaking), intaglio family, in which an image is incised into a plate (or "matrix") with a hard-pointed "needle" of sharp metal or diamond point. In principle, the method is practically ident ...

, and he anticipated the modern revival of etching which began in the 1850s. His prints were made by his friend and neighbour Henry Ninham, whose technique he influenced. His paintings of the Near East may have been made with future works in mind.

Background

Edward Daniell was associated with the

Edward Daniell was associated with the Norwich School of painters

The Norwich School of painters was the first provincial art movement established in Britain, active in the early 19th century. Artists of the school were inspired by the natural environment of the Norfolk landscape and owed some influence to the wo ...

, a regional school of landscape painters

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the p ...

who were connected personally or professionally. Though mainly inspired by the Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

countryside, many also depicted other landscapes, and coastal and urban scenes.

The school's most important artists were John Crome

John Crome (22 December 176822 April 1821), once known as Old Crome to distinguish him from his artist son John Berney Crome, was an English landscape painter of the Romantic era, one of the principal artists and founding members of the Norw ...

, Joseph Stannard

Joseph Stannard (13 September 1797 7 December 1830) was an English marine, landscape and portrait painter. He was a talented and prominent member of the Norwich School of painters.

After attending the Norwich Grammar School, his parents pa ...

, George Vincent, Robert Ladbrooke

Robert Ladbrooke (1768 – 11 October 1842) was an English landscape painter who, along with John Crome, founded the Norwich School of painters. His sons Henry Ladbrooke and John Berney Ladbrooke were also associated with the Norwich School.

Ea ...

, James Stark, John Thirtle

John Thirtle (baptised 22 June 177730 September 1839) was an English watercolour artist and frame-maker. Born in Norwich, where he lived for most of his life, he was a leading member of the Norwich School of painters.

Much of Thirtle's life i ...

and John Sell Cotman

John Sell Cotman (16 May 1782 – 24 July 1842) was an English marine and landscape painter, etcher, illustrator, author and a leading member of the Norwich School of painters.

Born in Norwich, the son of a silk merchant and lace dealer, Cot ...

, along with Cotman's sons Miles Edmund and John Joseph Cotman

John Joseph Cotman (1814–1878) was an English landscape painter, the second son of John Sell Cotman.

Life

Cotman was born in 1814 at Southtown, Great Yarmouth, and was baptised on 6 June 1814.John Joseph Cotman in "England Births and Christen ...

. The school was a unique phenomenon in the history of 19th-century British art: Norwich was the first English city outside London which had the right conditions for a provincial art movement. It had more locally born artists than any other similar city, and its theatrical, artistic, philosophical and musical cultures were cross-fertilised in a way that was unique outside the capital.

Life

Early life and education

Edward Thomas Daniell was born on 6June 1804 atCharlotte Street

Charlotte Street is a street in Fitzrovia, historically part of the parish and borough of St Pancras, in central London. It has been described, together with its northern and southern extensions (Fitzroy Street and Rathbone Place), as the ''s ...

in central London, to Sir Thomas Daniell, a retired attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

of Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

, and his second wife Anne Drosier, the daughter of John Drosier of Rudham Grange, Norfolk. Sir Thomas' first wife, with whom he had a son Earle and a daughter Anne, died in London in 1792. Their daughter married John Holmes in Norfolk in 1802 and died in childbirth in 1805. Her brother Earle was an officer in the 12th Dragoons by 1806.

Sir Thomas purchased land and slaves in the

Sir Thomas purchased land and slaves in the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean SeaNorth Atlantic Ocean

, coor ...

, which were then part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. His estates, including at Dickenson Bay

Dickenson Bay is located on the northwestern coast in Antigua, close to the Cedar Grove.

While Dickenson Bay is not the most secluded beach in Antigua, its white beaches and tranquil seas attract many visitors. A string of large resort hotels g ...

on Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

, had been bought in 1779 from the family of his first wife. He retired and moved to the west of Norfolk, but his health deteriorated and he died of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

in 1806, leaving a young widow and infant son. He left his Dominican lands to her, and his Antigua estate to his adult son Earle, subject to him providing a guaranteed annual income of £300 to the family in Norfolk. Anne Daniell and her son moved to a house in St. Giles Street, Norwich. She died in 1836 aged 64, and was buried in the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

of St Mary Coslany.

Edward Daniell grew up with his mother in Norwich and was educated at Norwich Grammar School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English independent day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as a ...

, where the drawing master was John Crome. He was involved in the art world at a young age; the brothers Thomas and Chambers Hall wrote to the artist John Linnell

John Sidney Linnell ( ; born June 12, 1959) is an American musician, known primarily as one half of the Brooklyn-based alternative rock band They Might Be Giants with John Flansburgh, which was formed in 1982. In addition to singing and songwri ...

in 1822 about "our young friend Mr Daniells who accompanied us to your house last week and who wishes to possess a drawing".

On 9 December 1823, aged 19, Daniell went to Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

to read classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

. He graduated in November 1828, despite having neglected his studies in favour of art. In a letter to Linnell, he wrote: "I find that the examinations for which I am preparing next month require a closer application to my literary studies than I had imagined and that I must not attempt to 'serve two masters'." He was introduced to etching by Joseph Stannard, and during the holidays practiced at Stannard's studio in St. Giles Terrace, around the corner from his own house. He graduated with a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

on 25 May 1831.

Travels in Europe and Scotland

Daniell had the financial means to travel abroad to find subjects to paint, and during 1829 and 1830 Daniell spent the months between his classics studies and his master's degree on aGrand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tuto ...

through France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland, producing scenic oil paintings

Oil painting is the process of painting with pigments with a medium of drying oil as the binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on wood panel or canvas for several centuries, spreading from Europe to the rest of ...

and watercolours

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to ...

that the art historian William Dickes described as "well-centred performances, painted with a fluid brush, and revealing a delicate appreciation of tone".

The route Daniell took during his eighteen months on the Continent is revealed by the order of his paintings. His travels through Switzerland are reminiscent of those of the artist

The route Daniell took during his eighteen months on the Continent is revealed by the order of his paintings. His travels through Switzerland are reminiscent of those of the artist James Pattison Cockburn

James Pattison Cockburn (18 March 1779 – 18 March 1847) was an artist, author and military officer. He was born into a military family and received his military training at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich where he received training in d ...

, who published his ''Swiss Scenery'' in 1820. In Rome and Naples he met the artist Thomas Uwins

Thomas Uwins (24 February 1782, in London – 26 August 1857) was a British portrait, subject, genre and landscape painter (in watercolour and oil), and a book illustrator. He became a full member of the Old Watercolour Society and a Royal ...

, who wrote: "What a shoal of amateur artists we have got here!... there is a too come to judgement! second Daniel!, I have gotten more substantial criticism from this young man than from anyone since Havell was my messmate."

Daniell may also have visited Spain, as his etching

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

s of the country were copied by the Norwich artist Henry Ninham, but there is no direct evidence he went there. It is possible he returned home in time for the funeral of Joseph Stannard, who died from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

on 7December 1830, aged33.

In the summer of 1832, Daniell went on a walking trip in Scotland, accompanied by two contemporaries from Oxford, George Denison and Edmund Walker Head

Sir Edmund Walker Head, 8th Baronet, KCB (16 February 1805 – 28 January 1868) was a 19th-century British politician and diplomat.

Early life and scholarship

Head was born at Wiarton Place, near Maidstone, Kent, the son of the Reverend Sir J ...

. The trip provided him with subject material and influenced his use of drypoint

Drypoint is a printmaking technique of the intaglio (printmaking), intaglio family, in which an image is incised into a plate (or "matrix") with a hard-pointed "needle" of sharp metal or diamond point. In principle, the method is practically ident ...

etching, as he was able to study the work of etchers such as Andrew Geddes. In ''The Etchings of E. T. Daniell'', Jane Thistlethwaite wrote that his Scottish scenes "testify in their subjects to his enthusiasm for the beauties of Scotland and in their technique to his almost certain acquaintance with the Scottish etchers".

Church career

On 2 October 1832 Daniell was

On 2 October 1832 Daniell was ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

in Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Norwich, Norfolk, dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity. It is the cathedral church for the Church of England Diocese of Norwich and is one of the Norwich 12 heritage sites.

The cathedral ...

as a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

, and three days later was licensed as the curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

of the parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

at Banham, a post he held for eighteen months. Letters to John Linnell show he felt a need to increase his income during this period in his life. Little is known of his career as a Norfolk curate, but the Banham registers, all of which have been preserved, show he led an active life in the parish. He continued to etch at this time, and in Thistlethwaite's view whilst there produced his "loveliest and most sophisticated plates".

On 2 June 1833, Daniell was ordained to the priesthood, but continued as the curate at Banham until 1834. That year he was appointed to the curacy of St. Mark's, North Audley Street in London, and took rooms in Park Street, Mayfair. He also worked at St. George's Hospital

St George's Hospital is a large teaching hospital in Tooting, London. Founded in 1733, it is one of the UK's largest teaching hospitals and one of the largest hospitals in Europe. It is run by the St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundatio ...

but, as with his curacy at St. Mark's, no official records of his employment have survived. In a letter written in 1835 to his Oxford tutor Joseph Blanco White

Joseph Blanco White, born José María Blanco y Crespo (11 July 1775 – 20 May 1841), was an Anglo-Spanish political thinker, theologian, and poet.

Life

Blanco White was born in Seville, Spain. He had Irish ancestry and was the son of the mer ...

, Daniell wrote: "You probably, thought I was haranguing the plough-boys in Norfolk, and you find me among the Dons of Grosvenor Square, and having to preach (as I must) next Wednesday at St. George's, Hanover Square. I wish you would come and give me some assistance." In about 1836 he moved to rooms in Green Street, near Grosvenor Square

Grosvenor Square is a large garden square in the Mayfair district of London. It is the centrepiece of the Mayfair property of the Duke of Westminster, and takes its name from the duke's surname "Grosvenor". It was developed for fashionable re ...

and close to St. Mark's, living there until his departure for the Holy Land in 1840.

The outer shell of Norwich Castle

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. William the Conqueror (1066–1087) ordered its construction in the aftermath of the Norman conquest of England. The castle was used as a ...

's keep

A keep (from the Middle English ''kype'') is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word ''keep'', but usually consider it to refer to large towers in c ...

was refaced in Bath stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City of ...

from 1834 to 1839, replicating the original blank arcading. Daniell was among those who strongly opposed the proposed refacing. Letters written from London show that he had not forgotten this contentious issue. He planned a plate of Ninham's drawing of the castle as a gesture of his opposition to the project, informing the antiquary

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

Dawson Turner

Dawson Turner (18 October 1775 – 21 June 1858) was an English banker, botanist and antiquary. He specialized in the botany of cryptogams and was the father-in-law of the botanist William Jackson Hooker.

Life

Turner was the son of Jam ...

that "I have had a very beautiful drawing made of it, and I mean to etch it the size of the drawing." His etching of the old keep was never completed.

Tour of the Near East

At some date after June 1840, perhaps inspired by the Scottish painterDavid Roberts David or Dave Roberts may refer to:

Arts and literature

* David Roberts (painter) (1796–1864), Scottish painter

* David Roberts (art collector), Scottish contemporary art collector

* David Roberts (novelist), English editor and mystery writer ...

who had travelled to Egypt and the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

to find landscapes to depict, Daniell resigned his curacy and left England to tour the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

. He arrived in Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

in September 1840. Although Roberts' paintings of the Middle East are thought to have compelled him to tour abroad, he had also been told of recent discoveries in Lycia

Lycia (Lycian language, Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean ...

(now part of modern Turkey) by the explorer Charles Fellows

Sir Charles Fellows (31 August 1799 – 8 November 1860) was a British archaeologist and explorer, known for his numerous expeditions in what is present-day Turkey.

Biography

Charles Fellows was born at High Pavement, Nottingham on 31 August ...

.

Daniell was in Athens by the end of the year, and sailed to

Daniell was in Athens by the end of the year, and sailed to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

early in 1841. He travelled up the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

to Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

, and then from Egypt to Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, on a route that took him past Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

. He reached Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

in October 1841.

He met Fellows in the Turkish city of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

and joined his expedition, boarding HMS ''Beacon'', a ship sent by the British Government to convey home antiquities

Antiquities are objects from antiquity, especially the civilizations of the Mediterranean: the Classical antiquity of Greece and Rome, Ancient Egypt and the other Ancient Near Eastern cultures. Artifacts from earlier periods such as the Meso ...

recently discovered by Fellows at Xanthos

Xanthos ( Lycian: 𐊀𐊕𐊑𐊏𐊀 ''Arñna'', el, Ξάνθος, Latin: ''Xanthus'', Turkish: ''Ksantos'') was an ancient major city near present-day Kınık, Antalya Province, Turkey. The remains of Xanthos lie on a hill on the left ba ...

. During the expedition 18 ancient cities were located. After spending the winter at Xanthos, Daniell chose to remain in Lycia to help survey the region, in company with Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt

Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt (11 May 181112 March 1888) was an English vice-admiral, hydrographer, and geologist.

Life

Thomas Spratt was born at Woodway House, East Teignmouth, the eldest son of Commander James Spratt, RN, who was a hero of ...

, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, and the naturalist Edward Forbes

Edward Forbes FRS, FGS (12 February 1815 – 18 November 1854) was a Manx naturalist. In 1846, he proposed that the distributions of montane plants and animals had been compressed downslope, and some oceanic islands connected to the mainlan ...

. Spratt was responsible for researching the area's topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

and Forbes its natural history; Daniell was to make records of any discoveries. In Lycia he produced a series of watercolours, of which Laurence Binyon

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869 – 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. Born in Lancaster, England, his parents were Frederick Binyon, a clergyman, and Mary Dockray. He studied at St Paul's School, London ...

said, "What strikes one most at first is the astonishing air of space and magnitude conveyed, the fluid wash of sunlight in these towering gorges and open valleys."

In March 1842, Fellows left for London on HMS ''Beacon'', in order to obtain bigger ships for transporting the antiquities back to England. Daniell travelled to

In March 1842, Fellows left for London on HMS ''Beacon'', in order to obtain bigger ships for transporting the antiquities back to England. Daniell travelled to Selge

Selge ( el, Σέλγη) was an important city in ancient Pisidia and later in Pamphylia, on the southern slope of Mount Taurus, modern Antalya Province, Turkey, at the part where the river Eurymedon River ( tr, Köprüçay) forces its way through ...

, sketching and exploring its ruins. He made copies of inscriptions from monuments in Cibyratis, Pisidia and Pamphylia, and visited Sillyon

Sillyon ( el, Σίλλυον), also Sylleion (Σύλλειον), in Byzantine times Syllaeum or Syllaion (), was an important fortress and city near Attaleia in Pamphylia, on the southern coast of modern Turkey. The native Greco-Pamphylian form ...

, Marmara, Perga

Perga or Perge ( Hittite: ''Parha'', el, Πέργη ''Perge'', tr, Perge) was originally an ancient Lycian settlement that later became a Greek city in Pamphylia. It was the capital of the Roman province of Pamphylia Secunda, now located in ...

and Lyrbe. His original drawings are now lost, but they were later published in ''Travels in Lycia, Milyas, and the Cibyratis, in company with the Late '', and his notes were transcribed (inaccurately) by Samuel Birch

Samuel Birch (3 November 1813 – 27 December 1885) was a British Egyptologist and antiquary.

Biography

Birch was the son of a rector at St Mary Woolnoth, London. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School. From an early age, his manifest ...

at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. Birch's collection contains a single page of Daniell's original manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

.

The expedition arrived at Adalia (now known as Antalya

Antalya () is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, fifth-most populous city in Turkey as well as the capital of Antalya Province. Located on Anatolia's southwest coast bordered by the Taurus Mountains, Antalya is the largest Turkish cit ...

) in April 1842. Spratt and Forbes left the city before Daniell, who travelled overland after meeting the Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

. He then visited Cyprus and painted a watercolour of the island, possibly while anchored off shore. The author Rita Severis has compared his painting with the watercolours of Turner, whom he was known to admire. In her book on artistic representations of the island from 1700 to 1960, she wrote: "The interplay of the blue sea and the sandy colour of the landwhich is repeated successfully in the foreground of the pictureaccentuates the distance between the viewer and the land while simultaneously increasing the desire to look more closely and attentively at the subject."

Death

In late May 1842 the ships and ''Media'' arrived and Daniell accepted an offer of a passage to England. In June he leftRhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

to return to Lycia and rejoin Forbes and Spratt, but he missed his ship''Monarch'' and ''Media'' had set sail the previous dayand was forced to amend his plans. There was a chance to return to Rhodes by caïque

A caïque ( el, καΐκι, ''kaiki'', from tr, kayık) is a traditional fishing boat usually found among the waters of the Ionian or Aegean Sea, and also a light skiff used on the Bosporus. It is traditionally a small wooden trading vessel, br ...

and join the returning ships, but he instead travelled to Adalia with the newly-appointed consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

for the city, John Purdie. During the journey Daniell became feverishly ill with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, contracted, according to Forbes and Spratt, "by lingering too long among the unhealthy marshes of the Pamphylian coast".

He stayed at Purdie's residence to recuperate, and wrote to Forbes and Spratt describing his discoveries at Apollonia and Lyrbe. Before he had fully recovered he left the city to undertake a solitary expedition to

He stayed at Purdie's residence to recuperate, and wrote to Forbes and Spratt describing his discoveries at Apollonia and Lyrbe. Before he had fully recovered he left the city to undertake a solitary expedition to Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; grc, Παμφυλία, ''Pamphylía'') was a region in the south of Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the north by ...

and Pisidia

Pisidia (; grc-gre, Πισιδία, ; tr, Pisidya) was a region of ancient Asia Minor located north of Pamphylia, northeast of Lycia, west of Isauria and Cilicia, and south of Phrygia, corresponding roughly to the modern-day province of An ...

, travelling during the hottest part of the year. He was forced back to Adalia after suffering a second attack of malaria, and at Purdie's house dictated what was to be his last letter, which expressed his intentions to continue his work. He lost consciousness after sleeping whilst exposed to the heat of the day on the front terrace of Purdie's residence, and died a week later, on 24 September. He was buried in the city. The Norfolk historian Frederick Beecheno wrote in 1889 that Daniell was "buried beneath an ancient granite column in the court of a Greek church in the centre of the town of Adalia".

Forbes paid tribute to his friend Daniell, writing that his illness "destroyed a traveller whose talents, scholarship, and research would have made Lycia a bright spot on the map of Asia Minor, and whose manliness of character and kindness of heart endeared him to all who had the happiness of knowing him".

A memorial was placed near his tomb in Antalya "by his affectionate and grieving relatives". Another memorial can be seen in Norwich, on the wall of the church of St. Mary Coslany. His will is preserved in the National Archives at Kew.

Friends and associates

Many of Daniell's etchings were printed in Norwich by Henry Ninham, who lived a short distance from Daniell's house on St. Giles Street. His friendships with Ninham and Joseph Stannard may have begun at school.

Daniell was an active patrons of the arts and held regular dinner parties and other gatherings at his London home. It became a resort of painters including John Linnell, David Roberts,

Many of Daniell's etchings were printed in Norwich by Henry Ninham, who lived a short distance from Daniell's house on St. Giles Street. His friendships with Ninham and Joseph Stannard may have begun at school.

Daniell was an active patrons of the arts and held regular dinner parties and other gatherings at his London home. It became a resort of painters including John Linnell, David Roberts, William Mulready

William Mulready (1 April 1786 – 7 July 1863) was an Irish genre painter living in London. He is best known for his romanticising depictions of rural scenes, and for creating Mulready stationery letter sheets, issued at the same time as the P ...

, William Dyce

William Dyce (; 19 September 1806 in Aberdeen14 February 1864) was a Scottish painter, who played a part in the formation of public art education in the United Kingdom, and the South Kensington Schools system. Dyce was associated with the Pre-R ...

, Thomas Creswick

Thomas Creswick (5 February 181128 December 1869) was a British landscapist and illustrator, and one of the best-known members of the Birmingham School of landscapists.

Biography

Creswick was born in Sheffield (at the time it was within Der ...

, Edwin Landseer

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (7 March 1802 – 1 October 1873) was an English painter and sculptor, well known for his paintings of animals – particularly horses, dogs, and stags. However, his best-known works are the lion sculptures at the bas ...

, William Collins, Abraham Cooper

Abraham Cooper (1787–1868) was a British animal and battle painter.

Life

The son of a tobacconist, he was born in Greenwich, London on the 8th September 1787.John Callcott Horsley

John Callcott Horsley RA (29 January 1817 – 18 October 1903) was an English academic painter of genre and historical scenes, illustrator, and designer of the first Christmas card. He was a member of the artist's colony in Cranbrook.

Child ...

, Charles Lock Eastlake

Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (17 November 1793 – 24 December 1865) was a British painter, gallery director, collector and writer of the 19th century. After a period as keeper, he was the first director of the National Gallery.

Life

Eastlake ...

, and William Clarkson Stanfield. Alfred Story, Linnell's biographer, described Daniell's home as "a treasure-house of art, (which) comprised works by some of the best painters of the day".

One of Daniell's pupils was the writer Elizabeth Rigby, who remembered him as the "old friend" who had introduced her to etching and admired her drawings. In 1891 she wrote: "My recollection of his face was that of one of the openest that could be seena superb forehead, and splendid teeth, which showed themselves with every smile, and no one smiled and laughed more genially."

John Linnell

Daniell first met the artist John Linnell while he was at Oxford. Linnell asked him to promote the sale of '' Illustrations of the Book of Job'' by the artist and poet

Daniell first met the artist John Linnell while he was at Oxford. Linnell asked him to promote the sale of '' Illustrations of the Book of Job'' by the artist and poet William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, who was Linnell's great friend. Daniell commissioned him to produce the painting now known as ''View of Lymington, the Isle of Wight beyond'' for the price of thirty guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from t ...

. At a later date, he exchanged it for ''Boy Minding Sheep'', paying the difference of twenty guineas. In 1828 Linnell made a portrait miniature

A portrait miniature is a miniature portrait painting, usually executed in gouache, watercolor, or enamel. Portrait miniatures developed out of the techniques of the miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, and were popular among 16th-century eli ...

of Daniell and taught him how to paint in oils.

They corresponded regularly and Linnell was a frequent guest at Daniell's rooms in London. Daniell encouraged him to complete his ''St. John the Baptist Preaching in the Wilderness'' (1828–1833), offering to buy it himself if it did not sell. When the painting was exhibited in 1839 at the British Institution

The British Institution (in full, the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom; founded 1805, disbanded 1867) was a private 19th-century society in London formed to exhibit the works of living and dead artists; it w ...

, it helped to enhance Linnell's reputation as an artist.

Before leaving for the Middle East, Daniell commissioned a portrait of J. M. W. Turner from Linnell. Turner had previously refused to sit for the artist, and it was difficult to get his agreement to be portrayed. Daniell positioned the two men opposite each other at dinner, so Linnell could observe Turner carefully and portray his likeness from memory. Due to Daniell's death, the completed painting was never delivered.

When Linnell's painting ''Noon

Noon (or midday) is 12 o'clock in the daytime. It is written as 12 noon, 12:00 m. (for meridiem, literally 12:00 noon), 12 p.m. (for post meridiem, literally "after noon"), 12 pm, or 12:00 (using a 24-hour clock) or 1200 (military time).

Solar ...

'' was rejected by the Royal Academy in 1840, Daniell came to his friend's assistance. The picture was taken to Daniell's house and hung above the fireplace, where it was admired by his dinner guests, including two members of the Academy. Daniell reprimanded them, saying "You are a pretty set of men to pretend to stand up for high art and to proclaim the Academy the fosterer of artistic talent, and yet allow such a picture to be rejected!"

J. M. W. Turner

Daniell's friendship with Turner, whom he first met in London, was short but intense. He was a regular guest at Daniell's gatherings and dinner parties, and they quickly became close friends. He was considered by Daniell's circle of artists to be their doyen. Beecheno, in his '': a memoir'', recalled that on one occasion Turner was asked his opinion of Daniell's work. "Very clever, Sir, very clever" was the great master's dictum, delivered in his usual blunt way." Elizabeth Rigby wrote of Daniell:

Roberts wrote that Daniell "adored Turner, when I and others doubted, and taught me to see and to distinguish his beauties over that of others... the old man really had a fond and personal regard for this young clergyman, which I doubt he ever evinced for the other."

He may have helped Turner spiritually. His biographer James Hamilton writes that he was "able to supply spiritual comfort that Turner required to help him fill the holes left by the deaths of his father and friends and to ease the fears of a naturally reflective man approaching old age". The old artist is known to have mourned Daniell's early death deeply, saying repeatedly to Roberts that he would never form such a friendship again. Roberts later wrote: "Poor Daniell, like Wilkie, went to Syria after me, but neither returned. Had Daniell returned to England, I have reason to know, from Turner's own mouth, he would have been entrusted with his law affairs."

Turner's romantic style is approached by Daniell's watercolours painted during his travels abroad. Coincidentally, Turner toured Switzerland in 1829, visiting sites Daniell had earlier depicted.

Daniell's friendship with Turner, whom he first met in London, was short but intense. He was a regular guest at Daniell's gatherings and dinner parties, and they quickly became close friends. He was considered by Daniell's circle of artists to be their doyen. Beecheno, in his '': a memoir'', recalled that on one occasion Turner was asked his opinion of Daniell's work. "Very clever, Sir, very clever" was the great master's dictum, delivered in his usual blunt way." Elizabeth Rigby wrote of Daniell:

Roberts wrote that Daniell "adored Turner, when I and others doubted, and taught me to see and to distinguish his beauties over that of others... the old man really had a fond and personal regard for this young clergyman, which I doubt he ever evinced for the other."

He may have helped Turner spiritually. His biographer James Hamilton writes that he was "able to supply spiritual comfort that Turner required to help him fill the holes left by the deaths of his father and friends and to ease the fears of a naturally reflective man approaching old age". The old artist is known to have mourned Daniell's early death deeply, saying repeatedly to Roberts that he would never form such a friendship again. Roberts later wrote: "Poor Daniell, like Wilkie, went to Syria after me, but neither returned. Had Daniell returned to England, I have reason to know, from Turner's own mouth, he would have been entrusted with his law affairs."

Turner's romantic style is approached by Daniell's watercolours painted during his travels abroad. Coincidentally, Turner toured Switzerland in 1829, visiting sites Daniell had earlier depicted.

Works and artistic style

As the son of a

As the son of a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

, Daniell was of a higher social class than his Norwich School contemporaries. He lived during a time when "it was not suitable for young gentlemen to become artists", and his private income and position as a curate meant he was to remain an amateur artist throughout his life; in a letter to Rigby, he referred to himself as a "tree and house sketcher".

The writer Derek Clifford believed Daniell's distinctive style was influenced by the methods of John Sell Cotman, an artist Daniell deeply admired, but the art historian Andrew Moore writes that "his artistic influences are not readily established," and Searle notes that he had an "assured individuality that recalls no one else". The historian Josephine Walpole, who believes Daniell's talent has yet to be properly recognised, has praised his ability to "create a sense of space, a feeling of heat or cold, of poverty or plenty, with apparent lack of effort".

In 1832 Daniell exhibited a number of his own pictures of scenes in Italy, Switzerland and France with the Norwich Society of Artists, which were favourably commented upon by the ''Norwich Mercury''. During the sole instance of an exhibition of his works with the Society, he showed ''Sketch from Nature'', ''Lake of Geneva, from Lausanne, painted on the spot''. ''Ruins of a Claudian Aqueduct, in the Campagna di Roma'', and ''Ruined Tombs, on the Via Nomentana, Rome, painted on the spot''.

He served on bodies involved with the arts, becoming a Fellow of the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

in 1835, and a committee member of the Society for the Encouragement of British Art in May 1837.

Oils and watercolours

Daniell's oil paintings generally depicted subjects encountered on his continental travels, and he showed them at annual exhibitions in London. He was an honorary exhibitor with the

Daniell's oil paintings generally depicted subjects encountered on his continental travels, and he showed them at annual exhibitions in London. He was an honorary exhibitor with the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

, showing four pieces there: ''Sion in the Valais'' (1837); ''View of St. Malo'' (1838); ''Sketch from a picture of the Mountains of Savoy from Geneva'' (1839); and ''Kenilworth'' (1840), as well as four pictures at the British Institute (''The Temple of Minerva'' (1836); ''Ruins of the Campagna of Rome'' (1838); ''Meadow scene'' (1839); and ''The Lake of Geneva, from near Lausanne'' (1840)).

His watercolours

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to ...

draw from a deliberately limited palette, exemplified by the paintings from his tours of the Middle East, where he used sepia

Sepia may refer to:

Biology

* ''Sepia'' (genus), a genus of cuttlefish

Color

* Sepia (color), a reddish-brown color

* Sepia tone, a photography technique

Music

* ''Sepia'', a 2001 album by Coco Mbassi

* ''Sepia'' (album) by Yu Takahashi

* " ...

, ultramarine

Ultramarine is a deep blue color pigment which was originally made by grinding lapis lazuli into a powder. The name comes from the Latin ''ultramarinus'', literally 'beyond the sea', because the pigment was imported into Europe from mines in Afgh ...

, and gamboge

Gamboge ( , ) is a partially transparent deep saffron to mustard yellow pigment.Other forms and spellings are: cambodia, cambogium, camboge, cambugium, gambaugium, gambogia, gambozia, gamboidea, gambogium, gumbouge, gambouge, gamboge, gambooge, g ...

, with details emphasised using bistre

Bistre (or bister) can refer to two things: a very dark shade of grayish brown (the version shown on the immediate right); a shade of brown made from soot, or the name for a color resembling the brownish pigment. Bistre's appearance is genera ...

, burnt sienna

Sienna (from it, terra di Siena, meaning "Siena earth") is an earth pigment containing iron oxide and manganese oxide. In its natural state, it is yellowish brown and is called raw sienna. When heated, it becomes a reddish brown and is calle ...

or white. The 120 large sketches at Norwich Castle and the further 64 at the British Museum may have been made in preparation for future works that were never made.

Daniell's watercolours have been highly praised by art historians. They were described by Hardie as "the perfection of free sketching". Binyon described them as showing him "at the height of his subject", and according to Andrew Hemingway, some of them are "magnificent". In Moore's opinion, Daniell's "fluid, sensitive use of washes", testified by his early ''Bure Bridge, Aylsham'', ranks him alongside William James Müller

William James Müller (28 June 18128 September 1845), also spelt Muller, was a British landscape and figure painter, the best-known artist of the Bristol School.

Life

Müller was born at Bristol, the son of J. S. Müller, a Prussian from Danz ...

and David Roberts, and the drawings produced on his last tour "reveal a vision that emulates that of David Roberts and exceeds that of Edward Lear". Clifford identified Daniell's distinctively bold style and sense of draughtsmanship, but pointed out what he saw as weaknesses in some of the watercolours: a “fear” of using colour, the emptiness of some of the panoramic views, and an unsuitable use of coloured paper.

Walpole sees Daniell's watercolours as having a style that "is all his own"freely drawn, ambitious and "having a powerful feeling for the atmosphere of the landscape". She notes how his delicate outlines and distinctively varied tones convey a sense of space and give an illusion of detail, citing ''Interior of Convent, Mount Sinai'' as a watercolour that expresses to her all that is best about Daniell's "understated artistry".

Etchings

Daniell's 52 attributed etchings, though small in number and not exhibited during his lifetime, are the basis for his reputation as an artist. In 1899, Binyon considered his etchings to befrom a historical point of viewthe most remarkable of his works, anticipating with their freedom of line theetching revival

The etching revival was the re-emergence and invigoration of etching as an original form of printmaking during the period approximately from 1850 to 1930. The main centres were France, Britain and the United States, but other countries, such as t ...

personified later in the century by Seymour Haden

Sir Francis Seymour Haden PPRE (16 September 1818 – 1 June 1910), was an English surgeon, better known as an original etcher who championed original printmaking. He was at the heart of the Etching Revival in Britain, and one of the founder ...

and James Abbott McNeill Whistler

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (; July 10, 1834July 17, 1903) was an American painter active during the American Gilded Age and based primarily in the United Kingdom. He eschewed sentimentality and moral allusion in painting and was a leading pr ...

. Malcolm Salaman, writing in the 1910s, observed:

Martin Hardie asserted: "If only more proofs from his fine plates been made available for collectors and museums he would be more readily placed among the great etchers of the world." Miklos Rajnai, a Keeper of Art at Norwich Castle Museum, compared Daniell's skill as an etcher with John Crome and John Sell Cotman. The British art historian Arthur Hind said the etchings "anticipated far more than nearly anything of Crome or Cotman the modern revival of etching".

Daniell's first attempts at etching were made with Joseph Stannard in February 1824. The style of his earliest works were influenced by Stannard, but he later became more affected by the works of J. M. W. Turner. Three distinct groups of etchings can be identified: those produced in Norfolk, including ''Flordon Bridge'', his masterpiece from his early years; a more grandiose group of etchings made during his tours of

Martin Hardie asserted: "If only more proofs from his fine plates been made available for collectors and museums he would be more readily placed among the great etchers of the world." Miklos Rajnai, a Keeper of Art at Norwich Castle Museum, compared Daniell's skill as an etcher with John Crome and John Sell Cotman. The British art historian Arthur Hind said the etchings "anticipated far more than nearly anything of Crome or Cotman the modern revival of etching".

Daniell's first attempts at etching were made with Joseph Stannard in February 1824. The style of his earliest works were influenced by Stannard, but he later became more affected by the works of J. M. W. Turner. Three distinct groups of etchings can be identified: those produced in Norfolk, including ''Flordon Bridge'', his masterpiece from his early years; a more grandiose group of etchings made during his tours of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

and the continent; and those made during his curacy at Banham, which includes his most assured work of this period, ''Whitlingham Lane near Trowse''. He stopped etching after his move to London. Although his Norfolk prints are mostly landscapes, they were intended to be artistic rather than topographically accurate, and any figures were used simply to indicate the scale of the landscape they were set in.

Daniell later employed a looser style, moving away from Stannard and towards that of Andrew Geddes and other Scottish etchers, whose output he almost certainly first saw while in Scotland during the summer of 1831. His was outstanding in the use of drypoint, strengthening his design by using the needle's point to create a burr in the plate. The burrs allowed the ink to collect, producing a darker tone in some of his prints. Thistlethwaite views the large drypoint etchings and Norfolk landscapes made after 1831 as being "supremely independent and for his time unique", once he had moved away from the traditional style of etchers like Geddes. He is thought to have introduced drypoint etching to his Norwich peers; both Thomas Lound

Thomas Lound (13 July 180118 January 1861) was an amateur English painter and etcher of landscapes, who specialised in depictions of his home county of Norfolk. He was a member of the Norwich School of painters, and lived in the city of Norwic ...

and Henry Ninham etched in this way after 1831, producing works of a quality approaching Daniell's own.

Legacy

Most of Daniell's works form part of the Norfolk Museums Collections, or are held at the British Museum, which obtained some of them before 1852 and purchased his prints as early as 1856.The original impressions are generally held in public collections. Binyon's biographical article appeared in 1889. Although none of Daniells' etchings were exhibited or published during his lifetime, some were given to friends. They were first shown in public in 1891 in a Norwich Arts Circle exhibition. In 1882, the economistInglis Palgrave

Sir Robert Harry Inglis Palgrave (11 June 1827 – 25 January 1919) was a British economist.

Early life

Robert Harry Inglis Palgrave was born on 11 June 1827. He was the son of Francis Palgrave (born Cohen) and his wife Elizabeth Turner, ...

wrote ''Twelve Etchings of the Rev. E. T. Daniell'', and 24 copies of the book were printed, one of which is at the Victoria & Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

. The book was never published. In 1921, Hardie delivered a lecture to the Print-Collectors' Club in which he discussed Daniell's plates. He has described them as "full of interest and technical value, and at the same time curiously modern in their spirit", adding of him: "He reaches a very high level of refined thought and execution in his ''Borough Bridge''."

Daniell's Middle East landscapes have provided important documentary evidence of the region during the 1840s. His works were exhibited at Aldeburgh

Aldeburgh ( ) is a coastal town in the English county, county of Suffolk, England. Located to the north of the River Alde. Its estimated population was 2,276 in 2019. It was home to the composer Benjamin Britten and remains the centre of the int ...

in 1968,