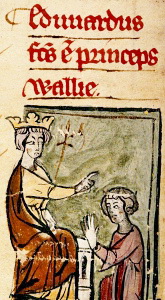

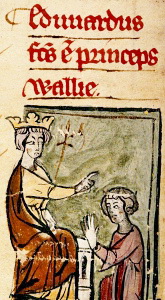

Edward of Caernarvon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was

Edward II was born in

Edward II was born in

Spending increased on Edward's personal household as he grew older and, in 1293, William of Blyborough took over as its administrator. Edward was probably given a religious education by the

Spending increased on Edward's personal household as he grew older and, in 1293, William of Blyborough took over as its administrator. Edward was probably given a religious education by the

Between 1297 and 1298, Edward was left as

Between 1297 and 1298, Edward was left as

During this time, Edward became close to

During this time, Edward became close to

Edward I mobilised another army for the Scottish campaign in 1307, which Prince Edward was due to join that summer, but the elderly king had been increasingly unwell and died on 7 July at

Edward I mobilised another army for the Scottish campaign in 1307, which Prince Edward was due to join that summer, but the elderly king had been increasingly unwell and died on 7 July at

Gaveston's return from exile in 1307 was initially accepted by the barons, but opposition quickly grew. He appeared to have an excessive influence on royal policy, leading to complaints from one chronicler that there were "two kings reigning in one kingdom, the one in name and the other in deed". Accusations, probably untrue, were levelled at Gaveston that he had stolen royal funds and had purloined Isabella's wedding presents. Gaveston had played a key role at Edward's coronation, provoking fury from both the English and the French contingents about the earl's ceremonial precedence and magnificent clothes, and about Edward's apparent preference for Gaveston's company over that of Isabella at the feast.

Gaveston's return from exile in 1307 was initially accepted by the barons, but opposition quickly grew. He appeared to have an excessive influence on royal policy, leading to complaints from one chronicler that there were "two kings reigning in one kingdom, the one in name and the other in deed". Accusations, probably untrue, were levelled at Gaveston that he had stolen royal funds and had purloined Isabella's wedding presents. Gaveston had played a key role at Edward's coronation, provoking fury from both the English and the French contingents about the earl's ceremonial precedence and magnificent clothes, and about Edward's apparent preference for Gaveston's company over that of Isabella at the feast.

Reactions to the death of Gaveston varied considerably.. Edward was furious and deeply upset over what he saw as the murder of Gaveston; he made provisions for Gaveston's family, and intended to take revenge on the barons involved. The earls of Pembroke and Surrey were embarrassed and angry about Warwick's actions, and shifted their support to Edward in the aftermath. To Lancaster and his core of supporters, the execution had been both legal and necessary to preserve the stability of the kingdom. Civil war again appeared likely, but in December, the Earl of Pembroke negotiated a potential peace treaty between the two sides, which would pardon the opposition barons for the killing of Gaveston, in exchange for their support for a fresh campaign in Scotland. Lancaster and Warwick, however, did not give the treaty their immediate approval, and further negotiations continued through most of 1313.

Meanwhile, the Earl of Pembroke had been negotiating with France to resolve the long-standing disagreements over the administration of Gascony, and as part of this Edward and Isabella agreed to travel to Paris in June 1313 to meet with Philip IV. Edward probably hoped both to resolve the problems in the south of France and to win Philip's support in the dispute with the barons; for Philip it was an opportunity to impress his son-in-law with his power and wealth. It proved a spectacular visit, including a grand ceremony in which the two kings knighted Philip's sons and two hundred other men in

Reactions to the death of Gaveston varied considerably.. Edward was furious and deeply upset over what he saw as the murder of Gaveston; he made provisions for Gaveston's family, and intended to take revenge on the barons involved. The earls of Pembroke and Surrey were embarrassed and angry about Warwick's actions, and shifted their support to Edward in the aftermath. To Lancaster and his core of supporters, the execution had been both legal and necessary to preserve the stability of the kingdom. Civil war again appeared likely, but in December, the Earl of Pembroke negotiated a potential peace treaty between the two sides, which would pardon the opposition barons for the killing of Gaveston, in exchange for their support for a fresh campaign in Scotland. Lancaster and Warwick, however, did not give the treaty their immediate approval, and further negotiations continued through most of 1313.

Meanwhile, the Earl of Pembroke had been negotiating with France to resolve the long-standing disagreements over the administration of Gascony, and as part of this Edward and Isabella agreed to travel to Paris in June 1313 to meet with Philip IV. Edward probably hoped both to resolve the problems in the south of France and to win Philip's support in the dispute with the barons; for Philip it was an opportunity to impress his son-in-law with his power and wealth. It proved a spectacular visit, including a grand ceremony in which the two kings knighted Philip's sons and two hundred other men in

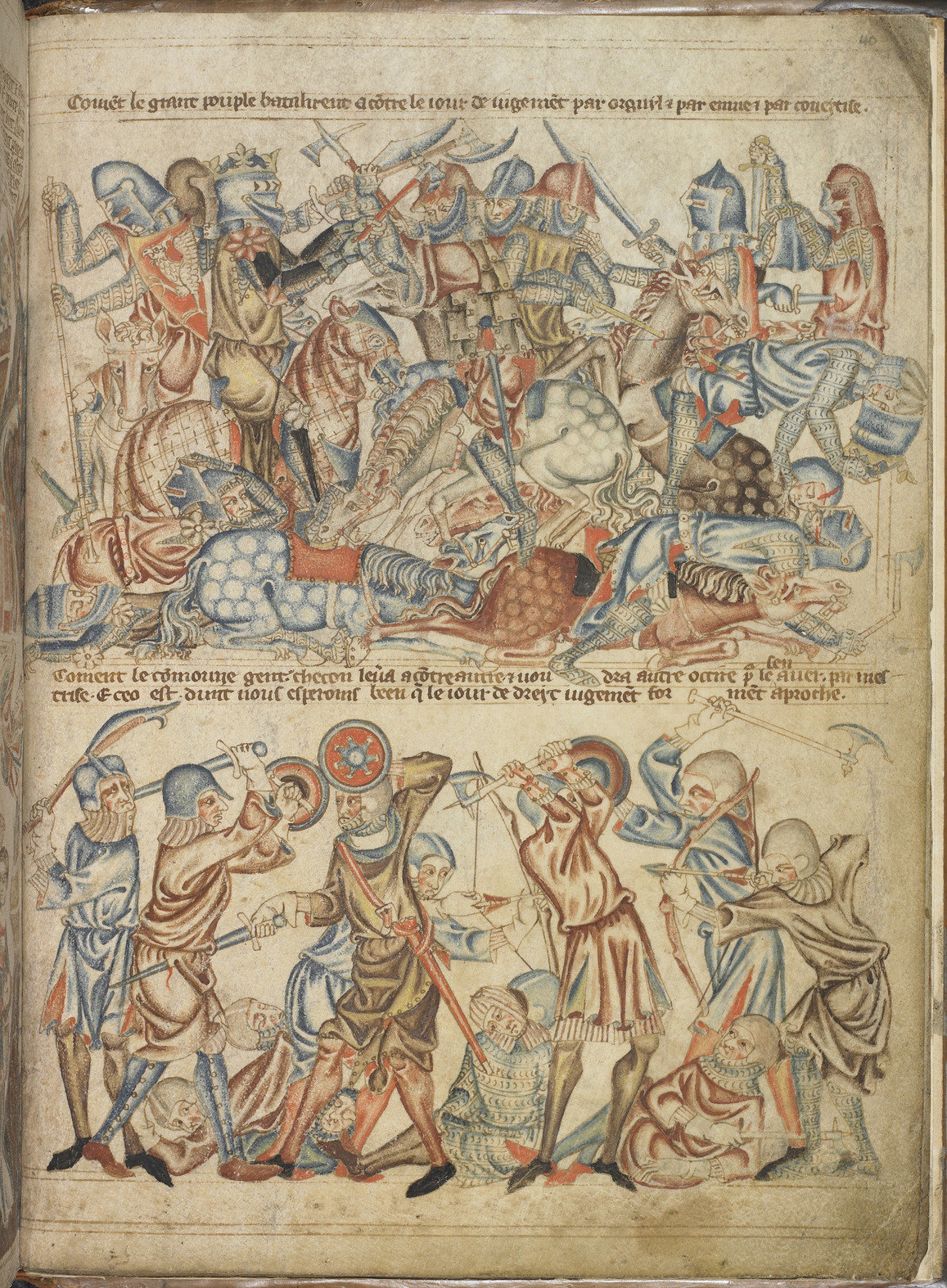

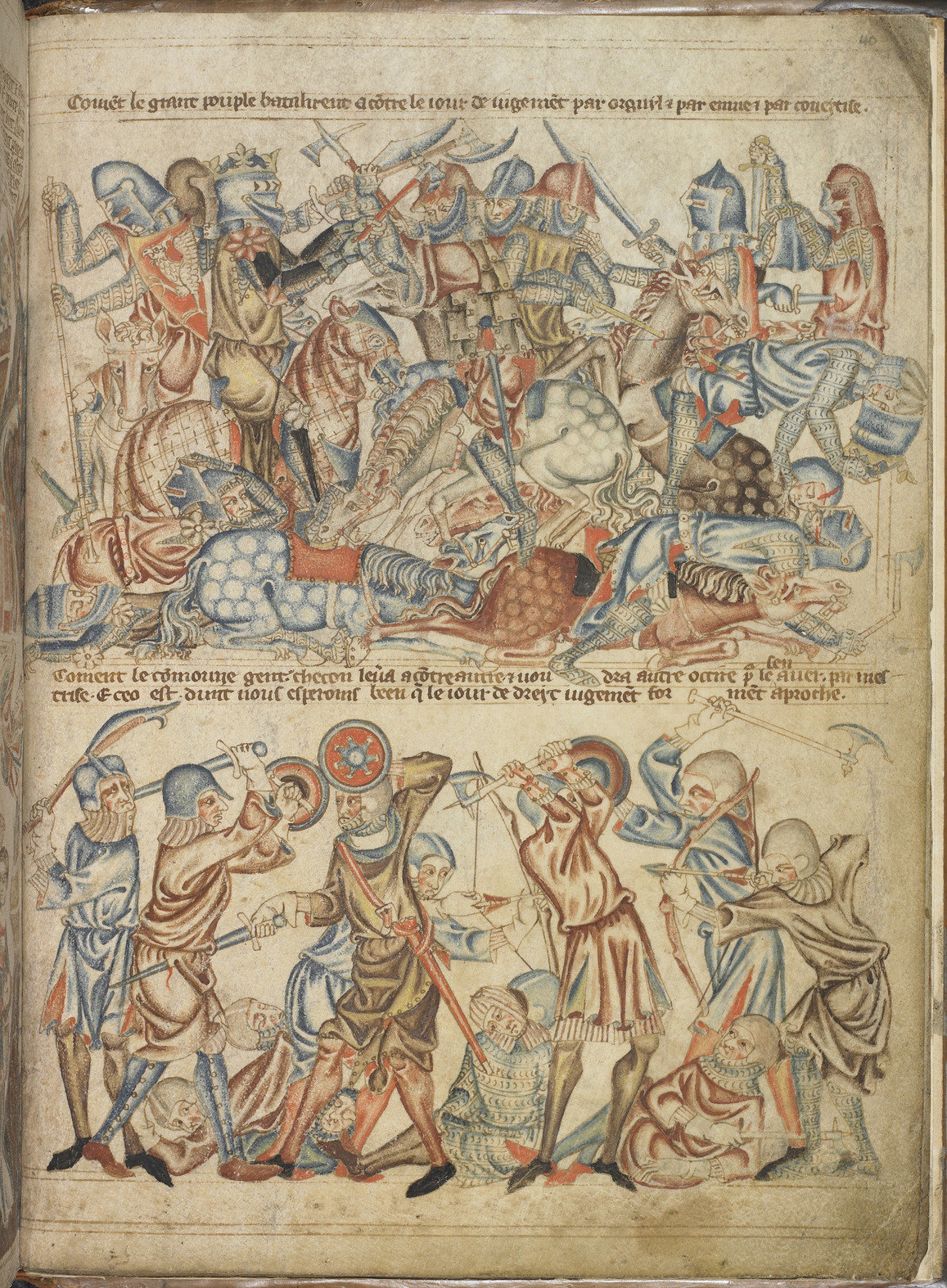

By 1314, Robert the Bruce had recaptured most of the

By 1314, Robert the Bruce had recaptured most of the

Edward punished Lancaster's supporters through a system of special courts across the country, with the judges instructed in advance how to sentence the accused, who were not allowed to speak in their own defence. Many of these so-called "Contrariants" were simply executed, and others were imprisoned or fined, with their lands seized and their surviving relatives detained. The Earl of Pembroke, whom Edward now mistrusted, was arrested; he was released only after pledging all his possessions as

Edward punished Lancaster's supporters through a system of special courts across the country, with the judges instructed in advance how to sentence the accused, who were not allowed to speak in their own defence. Many of these so-called "Contrariants" were simply executed, and others were imprisoned or fined, with their lands seized and their surviving relatives detained. The Earl of Pembroke, whom Edward now mistrusted, was arrested; he was released only after pledging all his possessions as

Isabella, with Edward's envoys, carried out negotiations with the French in late March.. The negotiations proved difficult, and they arrived at a settlement only after Isabella personally intervened with her brother, Charles. The terms favoured the French Crown: In particular, Edward would give homage in person to Charles for Gascony. Concerned about the consequences of war breaking out once again, Edward agreed to the treaty but decided to give Gascony to his son, Edward, and sent the prince to give homage in Paris. The young Prince Edward crossed the English Channel and completed the bargain in September.

Edward now expected Isabella and their son to return to England, but instead she remained in France and showed no intention of making her way back. Until 1322, Edward and Isabella's marriage appears to have been successful, but by the time Isabella left for France in 1325, it had deteriorated. Isabella appears to have disliked Hugh Despenser the Younger intensely, not least because of his abuse of high-status women. Isabella was embarrassed that she had fled from Scottish armies three times during her marriage to Edward, and she blamed Hugh for the final occurrence in 1322. When Edward had negotiated the recent truce with Robert the Bruce, he had severely disadvantaged a range of noble families who owned land in Scotland, including the Beaumonts, close friends of Isabella. She was also angry about the arrest of her household and seizure of her lands in 1324. Finally, Edward had taken away her children and given custody of them to Hugh Despenser's wife.

By February 1326 it was clear that Isabella was involved in a relationship with an exiled Marcher Lord, Roger Mortimer. It is unclear when Isabella first met Mortimer or when their relationship began, but they both wanted to see Edward and the Despensers removed from power. Edward appealed for his son to return, and for Charles to intervene on his behalf, but this had no effect.

Edward's opponents began to gather around Isabella and Mortimer in Paris, and Edward became increasingly anxious about the possibility that Mortimer might invade England. Isabella and Mortimer turned to

Isabella, with Edward's envoys, carried out negotiations with the French in late March.. The negotiations proved difficult, and they arrived at a settlement only after Isabella personally intervened with her brother, Charles. The terms favoured the French Crown: In particular, Edward would give homage in person to Charles for Gascony. Concerned about the consequences of war breaking out once again, Edward agreed to the treaty but decided to give Gascony to his son, Edward, and sent the prince to give homage in Paris. The young Prince Edward crossed the English Channel and completed the bargain in September.

Edward now expected Isabella and their son to return to England, but instead she remained in France and showed no intention of making her way back. Until 1322, Edward and Isabella's marriage appears to have been successful, but by the time Isabella left for France in 1325, it had deteriorated. Isabella appears to have disliked Hugh Despenser the Younger intensely, not least because of his abuse of high-status women. Isabella was embarrassed that she had fled from Scottish armies three times during her marriage to Edward, and she blamed Hugh for the final occurrence in 1322. When Edward had negotiated the recent truce with Robert the Bruce, he had severely disadvantaged a range of noble families who owned land in Scotland, including the Beaumonts, close friends of Isabella. She was also angry about the arrest of her household and seizure of her lands in 1324. Finally, Edward had taken away her children and given custody of them to Hugh Despenser's wife.

By February 1326 it was clear that Isabella was involved in a relationship with an exiled Marcher Lord, Roger Mortimer. It is unclear when Isabella first met Mortimer or when their relationship began, but they both wanted to see Edward and the Despensers removed from power. Edward appealed for his son to return, and for Charles to intervene on his behalf, but this had no effect.

Edward's opponents began to gather around Isabella and Mortimer in Paris, and Edward became increasingly anxious about the possibility that Mortimer might invade England. Isabella and Mortimer turned to

During August and September 1326, Edward mobilised his defences along the coasts of England to protect against the possibility of an invasion either by France or by Roger Mortimer. Fleets were gathered at the ports of

During August and September 1326, Edward mobilised his defences along the coasts of England to protect against the possibility of an invasion either by France or by Roger Mortimer. Fleets were gathered at the ports of

Isabella and Mortimer rapidly took revenge on the former regime. Hugh Despenser the Younger was put on trial, declared a traitor and sentenced to be disembowelled, castrated and quartered; he was duly executed on 24 November 1326. Edward's former chancellor, Robert Baldock, died in Fleet Prison; the Earl of Arundel was beheaded. Edward's position, however, was problematic; he was still married to Isabella and, in principle, he remained the king, but most of the new administration had much to lose were he to be released and potentially regain power.

There was no established procedure for removing an English king. Adam Orleton, the

Isabella and Mortimer rapidly took revenge on the former regime. Hugh Despenser the Younger was put on trial, declared a traitor and sentenced to be disembowelled, castrated and quartered; he was duly executed on 24 November 1326. Edward's former chancellor, Robert Baldock, died in Fleet Prison; the Earl of Arundel was beheaded. Edward's position, however, was problematic; he was still married to Isabella and, in principle, he remained the king, but most of the new administration had much to lose were he to be released and potentially regain power.

There was no established procedure for removing an English king. Adam Orleton, the

Those opposed to the new government began to make plans to free Edward, and Roger Mortimer decided to move him to the more secure location of

Those opposed to the new government began to make plans to free Edward, and Roger Mortimer decided to move him to the more secure location of

Edward's body was

Edward's body was

Edward's royal court was itinerant, travelling around the country with him. When housed in Westminster Palace, the court occupied a complex of two halls, seven chambers and three

Edward's royal court was itinerant, travelling around the country with him. When housed in Westminster Palace, the court occupied a complex of two halls, seven chambers and three

No chronicler for this period is entirely trustworthy or unbiased, often because their accounts were written to support a particular cause, but it is clear that most contemporary chroniclers were highly critical of Edward. The ''

No chronicler for this period is entirely trustworthy or unbiased, often because their accounts were written to support a particular cause, but it is clear that most contemporary chroniclers were highly critical of Edward. The ''

Several plays have shaped Edward's contemporary image..

Several plays have shaped Edward's contemporary image..  Edward's life has also been used in a wide variety of other media. In the Victorian era, the painting ''Edward II and Piers Gaveston'' by

Edward's life has also been used in a wide variety of other media. In the Victorian era, the painting ''Edward II and Piers Gaveston'' by

Edward II had four children with Isabella:

#

Edward II had four children with Isabella:

#

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

and Lord of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

from 1307 until he was deposed

Deposition by political means concerns the removal of a politician or monarch.

ORB: The Online Reference for Med ...

in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the ORB: The Online Reference for Med ...

heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the throne following the death of his elder brother Alphonso. Beginning in 1300, Edward accompanied his father on invasions of Scotland. In 1306, he was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed in a grand ceremony at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. Following his father's death, Edward succeeded to the throne in 1307. He married Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

, the daughter of the powerful King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 1 ...

, in 1308, as part of a long-running effort to resolve tensions between the English and French crowns.

Edward had a close and controversial relationship with Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househo ...

, who had joined his household in 1300. The precise nature of their relationship is uncertain; they may have been friends, lovers, or sworn brothers. Edward's relationship with Gaveston inspired Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

's 1592 play ''Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to th ...

'', along with other plays, films, novels and media. Gaveston's power as Edward's favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

provoked discontent among both the French royal family and the baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

s, and Edward was forced to exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

him. On Gaveston's return, the barons pressured the king into agreeing to wide-ranging reforms, called the Ordinances of 1311

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power of the English monarch. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the Lo ...

.

The newly empowered barons banished Gaveston, to which Edward responded by revoking the reforms and recalling his favourite. Led by Edward's cousin Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster

Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Leicester, 2nd Earl of Derby, ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Lincoln and ''jure uxoris'' 5th Earl of Salisbury (c. 1278 – 22 March 1322) was an English nobleman. A member of the House of Pl ...

, a group of the barons seized and executed Gaveston in 1312, beginning several years of armed confrontation. English forces were pushed back in Scotland, where Edward was decisively defeated by Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventual ...

at the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( gd, Blàr Allt nam Bànag or ) fought on June 23–24, 1314, was a victory of the army of King of Scots Robert the Bruce over the army of King Edward II of England in the First War of Scottish Independence. It was ...

in 1314. Widespread famine followed, and criticism of the king's reign mounted.

The Despenser family, in particular Hugh Despenser the Younger

Hugh le Despenser, 1st Baron le Despenser (c. 1287/1289 – 24 November 1326), also referred to as "the Younger Despenser", was the son and heir of Hugh le Despenser, Earl of Winchester (the Elder Despenser), by his wife Isabella de Beauchamp, ...

, became close friends and advisers to Edward, but Lancaster and many of the barons seized the Despensers' lands in 1321, and forced the king to exile them. In response, Edward led a short military campaign, capturing Lancaster at the Battle of Boroughbridge

The Battle of Boroughbridge was fought on 16 March 1322 in England between a group of rebellious barons and the forces of King Edward II, near Boroughbridge, north-west of York. The culmination of a long period of antagonism between the King a ...

and executing him. Edward and the Despensers strengthened their grip on power, formally revoking the 1311 reforms, executing their enemies and confiscating estates. Unable to make progress in Scotland, Edward finally signed a truce with Bruce.

Opposition to the regime grew, and when Isabella was sent to France to negotiate a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

in 1325, she turned against Edward and refused to return. Instead, she allied herself with the exiled Roger Mortimer, and invaded England with a small army in 1326. Edward's regime collapsed and he fled to Wales, where he was captured in November. The king was forced to relinquish his crown in January 1327 in favour of his 14-year-old son, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ...

, and he died in Berkeley Castle

Berkeley Castle ( ; historically sometimes spelled as ''Berkley Castle'' or ''Barkley Castle'') is a castle in the town of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom. The castle's origins date back to the 11th century, and it has been desi ...

on 21 September, probably murdered on the orders of the new regime.

Edward's contemporaries criticised his performance as king, noting his failures in Scotland and the oppressive regime of his later years, although 19th-century academics later argued that the growth of parliamentary institutions during his reign was a positive development for England over the longer term.

Background

Edward II was the fourth son ofEdward I, King of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

, Lord of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

, and ruler of Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

in south-western France (which he held as the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

vassal of the king of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the first ...

), and Eleanor, Countess of Ponthieu in northern France. Eleanor was from the Castilian royal family. Edward I proved a successful military leader, leading the suppression of the baronial revolts in the 1260s and joining the Ninth Crusade

Lord Edward's crusade, sometimes called the Ninth Crusade, was a military expedition to the Holy Land under the command of Edward, Duke of Gascony (future King Edward I of England) in 1271–1272. It was an extension of the Eighth Crusade and was ...

. During the 1280s he conquered North Wales, removing the native Welsh

The Welsh ( cy, Cymry) are an ethnic group native to Wales. "Welsh people" applies to those who were born in Wales ( cy, Cymru) and to those who have Welsh ancestry, perceiving themselves or being perceived as sharing a cultural heritage and sh ...

princes from power and, in the 1290s, he intervened in Scotland's civil war, claiming suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

over the country. He was considered an extremely successful ruler by his contemporaries, largely able to control the powerful earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

s that formed the senior ranks of the English nobility. The historian Michael Prestwich

Michael Charles Prestwich OBE (born 30 January 1943) is an English historian, specialising on the history of medieval England, in particular the reign of Edward I. He is retired, having been Professor of History at Durham University and Head ...

describes Edward I as "a king to inspire fear and respect", while John Gillingham

John Bennett Gillingham (born 3 August 1940) is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at the London School of Economics and Political Science. On 19 July 2007 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

Gillingham is renowned as an expert on ...

characterises him as an "efficient bully".

Despite Edward I's successes, when he died in 1307 he left a range of challenges for his son to resolve. One of the most critical was the problem of English rule in Scotland, where Edward I's long but ultimately inconclusive military campaign was ongoing when he died. His control of Gascony created tension with the French kings.. They insisted that the English kings give homage

Homage (Old English) or Hommage (French) may refer to:

History

*Homage (feudal) /ˈhɒmɪdʒ/, the medieval oath of allegiance

*Commendation ceremony, medieval homage ceremony Arts

*Homage (arts) /oʊˈmɑʒ/, an allusion or imitation by one arti ...

to them for the lands; the English kings saw this demand as insulting to their honour, and the issue remained unresolved. Edward I also faced increasing opposition from his barons over the taxation and requisitions required to resource his wars, and left his son debts of around £200,000 on his death.

Early life (1284–1307)

Birth

Edward II was born in

Edward II was born in Caernarfon Castle

Caernarfon Castle ( cy, Castell Caernarfon ) – often anglicised as Carnarvon Castle or Caernarvon Castle – is a medieval fortress in Caernarfon, Gwynedd, north-west Wales cared for by Cadw, the Welsh Government's historic environ ...

in north Wales

, area_land_km2 = 6,172

, postal_code_type = Postcode

, postal_code = LL, CH, SY

, image_map1 = Wales North Wales locator map.svg

, map_caption1 = Six principal areas of Wales common ...

on 25 April 1284, less than a year after Edward I had conquered the region, and as a result is sometimes called Edward of Caernarfon. The king probably chose the castle deliberately as the location for Edward's birth as it was an important symbolic location for the native Welsh, associated with Roman imperial history, and it formed the centre of the new royal administration of North Wales. Edward's birth brought predictions of greatness from contemporary prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

s, who believed that the Last Days of the world were imminent, declaring him a new King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

, who would lead England to glory. David Powel

David Powel (1549/52 – 1598) was a Welsh Church of England clergyman and historian who published the first printed history of Wales in 1584.

Life

Powel was born in Denbighshire and commenced his studies at the University of Oxford when he was 1 ...

, a 16th-century clergyman, suggested that the baby was offered to the Welsh as a prince "that was borne in Wales and could speake never a word of English", but there is no evidence to support this account.

Edward's name was English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

in origin, linking him to the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

, and was chosen by his father instead of the more traditional Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

and Castilian names selected for Edward's brothers: John and Henry, who had died before Edward was born, and Alphonso, who died in August 1284, leaving Edward as the heir to the throne.. Although Edward was a relatively healthy child, there were enduring concerns throughout his early years that he too might die and leave his father without a male heir. After his birth, Edward was looked after by a wet nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cu ...

called Mariota or Mary Maunsel for a few months until she fell ill, when Alice de Leygrave became his foster mother.; ; . He would have barely known his natural mother, Eleanor, who was in Gascony with his father during his earliest years. An official household, complete with staff, was created for the new baby, under the direction of a clerk, Giles of Oudenarde.

Childhood, personality and appearance

Spending increased on Edward's personal household as he grew older and, in 1293, William of Blyborough took over as its administrator. Edward was probably given a religious education by the

Spending increased on Edward's personal household as he grew older and, in 1293, William of Blyborough took over as its administrator. Edward was probably given a religious education by the Dominican friar

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of Cal ...

s, whom his mother invited into his household in 1290. He was assigned one of his grandmother's followers, Guy Ferre, as his ''magister'', who was responsible for his discipline, training him in riding and military skills. It is uncertain how well educated Edward was; there is little evidence for his ability to read and write, although his mother was keen that her other children be well educated, and Ferre was himself a relatively learned man for the period. Edward likely mainly spoke Anglo-Norman French

Anglo-Norman, also known as Anglo-Norman French ( nrf, Anglo-Normaund) ( French: ), was a dialect of Old Norman French that was used in England and, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland during the Anglo-Norman period.

When ...

in his daily life, in addition to some English and possibly Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

.

Edward had a normal upbringing for a member of a royal family. He was interested in horses and horsebreeding

Horse breeding is reproduction in horses, and particularly the human-directed process of selective breeding of animals, particularly purebred horses of a given breed. Planned matings can be used to produce specifically desired characteristics in ...

, and became a good rider; he also liked dogs, in particular greyhound

The English Greyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, the breed has seen a resurge ...

s. In his letters, he shows a quirky sense of humour, joking about sending unsatisfactory animals to his friends, such as horses who disliked carrying their riders, or lazy hunting dogs too slow to catch rabbits. He was not particularly interested in hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

or falconry

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person ...

, both popular activities in the 14th century. He enjoyed music, including Welsh music

The Music of Wales (Welsh: ''Cerddoriaeth Cymru''), particularly singing, is a significant part of Welsh national identity, and the country is traditionally referred to as "the land of song".Davies (2008), pg 579.

This is a modern stereotype ba ...

and the newly invented crwth

The crwth (, also called a crowd or rote or crotta) is a bowed lyre, a type of stringed instrument, associated particularly with Welsh music, now archaic but once widely played in Europe. Four historical examples have survived and are to be foun ...

instrument, as well as musical organs. He did not take part in jousting

Jousting is a martial game or hastilude between two horse riders wielding lances with blunted tips, often as part of a tournament (medieval), tournament. The primary aim was to replicate a clash of heavy cavalry, with each participant trying t ...

, either because he lacked the aptitude or because he had been banned from participating for his personal safety, but he was certainly supportive of the sport.

Edward grew up to be tall and muscular, and was considered good-looking by the standards of the period. He had a reputation as a competent public speaker and was known for his generosity to household staff. Unusually, he enjoyed rowing

Rowing is the act of propelling a human-powered watercraft using the sweeping motions of oars to displace water and generate reactional propulsion. Rowing is functionally similar to paddling, but rowing requires oars to be mechanically atta ...

, as well as hedging and ditch

A ditch is a small to moderate divot created to channel water. A ditch can be used for drainage, to drain water from low-lying areas, alongside roadways or fields, or to channel water from a more distant source for plant irrigation. Ditches ar ...

ing, and enjoyed associating with labourers and other lower-class workers. This behaviour was not considered normal for the nobility of the period and attracted criticism from contemporaries.

In 1290, Edward's father had confirmed the Treaty of Birgham

The Treaty of Birgham, also referred to as the Treaty of Salisbury, comprised two treaties in 1289 and 1290 intended to secure the independence of Scotland after the death of Alexander III of Scotland and accession of his three-year-old granddaug ...

, in which he promised to marry his six-year-old son to the young Margaret of Norway, who had a potential claim to the crown of Scotland. Margaret died later that year, bringing an end to the plan. Edward's mother, Eleanor, died shortly afterwards, followed by his grandmother, Eleanor of Provence

Eleanor of Provence (c. 1223 – 24/25 June 1291) was a French noblewoman who became Queen of England as the wife of King Henry III from 1236 until his death in 1272. She served as regent of England during the absence of her spouse in 1253.

...

.. Edward I was distraught at his wife's death and held a huge funeral for her; his son inherited the County of Ponthieu from Eleanor. Next, a French marriage was considered for the young Edward, to help secure a lasting peace with France, but war broke out in 1294.; . The idea was replaced with the proposal of a marriage to a daughter of Guy, Count of Flanders

Guy of Dampierre (french: Gui de Dampierre; nl, Gwijde van Dampierre) ( – 7 March 1305, Compiègne) was the Count of Flanders (1251–1305) and Marquis of Namur (1264–1305). He was a prisoner of the French when his Flemings defeated th ...

, but this too failed after it was blocked by King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 12 ...

.

Early campaigns in Scotland

Between 1297 and 1298, Edward was left as

Between 1297 and 1298, Edward was left as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

in charge of England while the king campaigned in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

against Philip IV, who had occupied part of the English king's lands in Gascony. On his return, Edward I signed a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

, under which he took Philip's sister, Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

, as his wife and agreed that Prince Edward would in due course marry Philip's daughter, Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

, who was then only two years old. In theory, this marriage would mean that the disputed Duchy of Gascony would be inherited by a descendant of both Edward and Philip, providing a possible end to the long-running tensions. The young Edward seems to have got on well with his new stepmother, who gave birth to Edward's two half-brothers, Thomas of Brotherton

Thomas of Brotherton, 1st Earl of Norfolk (1 June 13004 August 1338), was the fifth son of King Edward I of England (1239–1307), and the eldest child by his second wife, Margaret of France, the daughter of King Philip III of France. He was, t ...

and Edmund of Woodstock, in 1300 and 1301. As king, Edward later provided his brothers with financial support and titles..

Edward I returned to Scotland once again in 1300, and this time took his son with him, making him the commander of the rearguard at the siege of Caerlaverock Castle

Caerlaverock Castle is a moated triangular castle first built in the 13th century. It is located on the southern coast of Scotland, south of Dumfries, on the edge of the Caerlaverock National Nature Reserve. Caerlaverock was a stronghold of th ...

. In the spring of 1301, the king declared Edward the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, granting him the earldom of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and ...

and lands across North Wales; he seems to have hoped that this would help pacify the region, and that it would give his son some financial independence. Edward received homage from his Welsh subjects and then joined his father for the 1301 Scottish campaign; he took an army of around 300 soldiers north with him and captured Turnberry Castle

Turnberry Castle is a fragmentary ruin on the coast of Kirkoswald parish, near Maybole in Ayrshire, Scotland.''Ordnance of Scotland'', ed. Francis H. Groome, 1892-6. Vol.6, p.454 Situated at the extremity of the lower peninsula within the paris ...

. Prince Edward also took part in the 1303 campaign during which he besieged Brechin Castle

Brechin Castle is a castle in Brechin, Angus, Scotland. The castle was constructed in stone during the 13th century. Most of the current building dates to the early 18th century, when extensive reconstruction was carried out by architect Alexan ...

, deploying his own siege engine in the operation. In the spring of 1304, Edward conducted negotiations with the rebel Scottish leaders on the king's behalf and, when these failed, he joined his father for the siege of Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

..

In 1305, Edward and his father quarrelled, probably over the issue of money. The prince had an altercation with Bishop Walter Langton

Walter Langton (died 1321) of Castle Ashby'Parishes: Castle Ashby', in A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 4, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1937), pp. 230-236/ref> in Northamptonshire, was Bishop of Lichfield, Bishop of Coventry and Lic ...

, who served as the royal treasurer, apparently over the amount of financial support Edward received from the Crown. The king defended his treasurer, and banished Prince Edward and his companions from his court, cutting off their financial support. After some negotiations involving family members and friends, the two men were reconciled.

The Scottish conflict flared up once again in 1306, when Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventual ...

killed his rival John Comyn III of Badenoch, and declared himself King of the Scots.. Edward I mobilised a fresh army, but decided that, this time, his son would be formally in charge of the expedition. Prince Edward was made the duke of Aquitaine

The Duke of Aquitaine ( oc, Duc d'Aquitània, french: Duc d'Aquitaine, ) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As succe ...

and then, along with many other young men, he was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed in a lavish ceremony at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

called the Feast of the Swans

The Feast of the Swans was a chivalric celebration of the knighting of 267 men at Westminster Abbey on 22 May 1306. It followed a proclamation by Edward I that all esquires eligible for knighthood should come to Westminster to be knighted in turn ...

. Amid a huge feast in the neighbouring hall, reminiscent of Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

s and crusading

The First Crusade inspired the crusading movement, which became an important part of late medieval western culture. The movement influenced the Church, politics, the economy, society and created a distinct ideology that described, regulated, a ...

events, the assembly took a collective oath to defeat Bruce. It is unclear what role Prince Edward's forces played in the campaign that summer, which, under the orders of Edward I, saw a punitive, brutal retaliation against Bruce's faction in Scotland. Edward returned to England in September, where diplomatic negotiations to finalise a date for his wedding to Isabella continued.

Piers Gaveston and sexuality

During this time, Edward became close to

During this time, Edward became close to Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househo ...

. Gaveston was the son of one of the king's household knights whose lands lay adjacent to Gascony, and had himself joined Prince Edward's household in 1300, possibly on Edward I's instruction. The two got on well; Gaveston became a squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Use of the term evolved over time. Initially, a squire served as a knight's apprentice. Later, a village leader or a lord of the manor might come to be known as a " ...

and was soon being referred to as a close companion of Edward, before being knighted by the king during the Feast of the Swans in 1306. The king then exiled Gaveston to Gascony in 1307 for reasons that remain unclear. According to one chronicler, Edward had asked his father to allow him to give Gaveston the County of Ponthieu, and the king responded furiously, pulling his son's hair out in great handfuls, before exiling Gaveston. The official court records, however, show Gaveston being only temporarily exiled, supported by a comfortable stipend; no reason is given for the order, suggesting that it may have been an act aimed at punishing the prince.

The possibility that Edward had a sexual relationship with Gaveston or his later favourites has been extensively discussed by historians, complicated by the paucity of surviving evidence to determine for certain the details of their relationships. Homosexuality was fiercely condemned by the Church in 14th-century England, which equated it with heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, but engaging in sex with another man did not necessarily define an individual's personal identity in the same way it might in the 21st century. Both men had sexual relationships with their wives, who bore them children; Edward also had an illegitimate son, and may have had an affair with his niece, Eleanor de Clare

Eleanor de Clare, suo jure 6th Lady of Glamorgan (3 October 1292 – 30 June 1337) was a Anglo-Welsh noblewoman who married Hugh Despenser the Younger and was a granddaughter of Edward I of England.Lewis, M. E. (2008). A traitor's death? The id ...

.

The contemporary evidence supporting their homosexual relationship comes primarily from an anonymous chronicler in the 1320s who described how Edward "felt such love" for Gaveston that "he entered into a covenant of constancy, and bound himself with him before all other mortals with a bond of indissoluble love, firmly drawn up and fastened with a knot." The first specific suggestion that Edward engaged in sex with men was recorded in 1334, when Adam Orleton

Adam Orleton (died 1345) was an English churchman and royal administrator.

Life

Orleton was born into a Herefordshire family, possibly in Orleton, possibly in Hereford. The lord of the manor was Roger Mortimer, to whose interests Orleton was loy ...

, the Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except dur ...

, was accused of having stated in 1326 that Edward was a "sodomite", although Orleton defended himself by arguing that he had meant that Edward's advisor, Hugh Despenser the Younger

Hugh le Despenser, 1st Baron le Despenser (c. 1287/1289 – 24 November 1326), also referred to as "the Younger Despenser", was the son and heir of Hugh le Despenser, Earl of Winchester (the Elder Despenser), by his wife Isabella de Beauchamp, ...

, was a sodomite, rather than the late king. The Meaux Chronicle from the 1390s simply notes that Edward gave himself "too much to the vice of sodomy".

Alternatively, Edward and Gaveston may have simply been friends with a close working relationship. Contemporary chronicler

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and lo ...

comments are vaguely worded; Orleton's allegations were at least in part politically motivated, and are very similar to the highly politicised sodomy allegations made against Pope Boniface VIII and the Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

in 1303 and 1308 respectively. Later accounts by chroniclers of Edward's activities may trace back to Orleton's original allegations, and were certainly adversely coloured by the events at the end of Edward's reign. Such historians as Michael Prestwich and Seymour Phillips have argued that the public nature of the English royal court would have made it unlikely that any homosexual affairs would have remained discreet; neither the contemporary Church, Edward's father nor his father-in-law appear to have made any adverse comments about Edward's sexual behaviour.

A more recent theory, proposed by the historian Pierre Chaplais

Pierre Théophile Victorien Marie Chaplais (8 July 1920 – 26 November 2006) was a French historian. He was Reader in Diplomatic at the University of Oxford from 1957 to 1987.

Born in Châteaubriant, Loire-Inférieure (now Loire-Atlantique), ...

, suggests that Edward and Gaveston entered into a bond of adoptive brotherhood. Compacts of adoptive brotherhood, in which the participants pledged to support each other in a form of "brotherhood-in-arms", were not unknown between close male friends in the Middle Ages. Many chroniclers described Edward and Gaveston's relationship as one of brotherhood, and one explicitly noted that Edward had taken Gaveston as his adopted brother. Chaplais argues that the pair may have made a formal compact in either 1300 or 1301, and that they would have seen any later promises they made to separate or to leave each other as having been made under duress, and therefore invalid.

Early reign (1307–1311)

Coronation and marriage

Edward I mobilised another army for the Scottish campaign in 1307, which Prince Edward was due to join that summer, but the elderly king had been increasingly unwell and died on 7 July at

Edward I mobilised another army for the Scottish campaign in 1307, which Prince Edward was due to join that summer, but the elderly king had been increasingly unwell and died on 7 July at Burgh by Sands

Burgh by Sands () is a village and civil parish in the City of Carlisle district of Cumbria, England, situated near the Solway Firth. The parish includes the village of Burgh by Sands along with Longburgh, Dykesfield, Boustead Hill, Moorhouse ...

.. Edward travelled from London immediately after the news reached him, and on 20 July he was proclaimed king. He continued north into Scotland and on 4 August received homage from his Scottish supporters at Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from the ...

, before abandoning the campaign and returning south.. Edward promptly recalled Piers Gaveston, who was then in exile, and made him Earl of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.

Condor of Cornwall

*Condor of Cornwall, ...

, before arranging his marriage to the wealthy Margaret de Clare. Edward also arrested his old adversary Bishop Langton, and dismissed him from his post as treasurer. Edward I's body was kept at Waltham Abbey

Waltham Abbey is a town and civil parish in the Epping Forest District of Essex, within the metropolitan and urban area of London, England, north-east of Charing Cross. It lies on the Greenwich Meridian, between the River Lea in the west and E ...

for several months before being taken for burial to Westminster, where Edward erected a simple marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite. Marble is typically not Foliation (geology), foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the ...

tomb for his father.

In 1308, Edward's marriage to Isabella of France proceeded. Edward crossed the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

to France in January, leaving Gaveston as his ''custos regni'' in charge of the kingdom. This arrangement was unusual, and involved unprecedented powers being delegated to Gaveston, backed by a specially engraved Great Seal. Edward probably hoped that the marriage would strengthen his position in Gascony and bring him much needed funds. The final negotiations, however, proved challenging: Edward and Philip IV did not like each other, and the French king drove a hard bargain over the size of Isabella's dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

...

and the details of the administration of Edward's lands in France. As part of the agreement, Edward gave homage to Philip for the Duchy of Aquitaine and agreed to a commission to complete the implementation of the 1303 Treaty of Paris.

The pair were married in Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

on 25 January. Edward gave Isabella a psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the emergence of the book of hours in the Late Middle Ages, psalters we ...

as a wedding gift, and her father gave her gifts worth over 21,000 livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 gr ...

and a fragment of the True Cross

The True Cross is the cross upon which Jesus was said to have been crucified, particularly as an object of religious veneration. There are no early accounts that the apostles or early Christians preserved the physical cross themselves, althoug ...

. The pair returned to England in February, where Edward had ordered Westminster Palace

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

to be lavishly restored in readiness for their coronation and wedding feast, complete with marble tables, forty ovens and a fountain that produced wine and pimento, a spiced medieval drink. After some delays, the ceremony went ahead on 25 February at Westminster Abbey, under the guidance of Henry Woodlock, the Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except dur ...

. As part of the coronation, Edward swore to uphold "the rightful laws and customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen". It is uncertain what this meant: It might have been intended to force Edward to accept future legislation, it may have been inserted to prevent him from overturning any future vows he might take, or it may have been an attempt by the king to ingratiate himself with the barons.; . The event was marred by the large crowds of eager spectators who surged into the palace, knocking down a wall and forcing Edward to flee by the back door.

Isabella was only twelve at the time of her wedding, young even by the standards of the period, and Edward probably had sexual relations with mistresses during their first few years together. During this time he fathered an illegitimate son, Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

, who was born possibly as early as 1307. Edward and Isabella's first son, the future Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ...

, was born in 1312 amid great celebrations, and three more children followed: John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

in 1316, Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was introd ...

in 1318 and Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*:Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

* Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

in 1321.

Tensions over Gaveston

Gaveston's return from exile in 1307 was initially accepted by the barons, but opposition quickly grew. He appeared to have an excessive influence on royal policy, leading to complaints from one chronicler that there were "two kings reigning in one kingdom, the one in name and the other in deed". Accusations, probably untrue, were levelled at Gaveston that he had stolen royal funds and had purloined Isabella's wedding presents. Gaveston had played a key role at Edward's coronation, provoking fury from both the English and the French contingents about the earl's ceremonial precedence and magnificent clothes, and about Edward's apparent preference for Gaveston's company over that of Isabella at the feast.

Gaveston's return from exile in 1307 was initially accepted by the barons, but opposition quickly grew. He appeared to have an excessive influence on royal policy, leading to complaints from one chronicler that there were "two kings reigning in one kingdom, the one in name and the other in deed". Accusations, probably untrue, were levelled at Gaveston that he had stolen royal funds and had purloined Isabella's wedding presents. Gaveston had played a key role at Edward's coronation, provoking fury from both the English and the French contingents about the earl's ceremonial precedence and magnificent clothes, and about Edward's apparent preference for Gaveston's company over that of Isabella at the feast.

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

met in February 1308 in a heated atmosphere.. Edward was eager to discuss the potential for governmental reform, but the barons were unwilling to begin any such debate until the problem of Gaveston had been resolved. Violence seemed likely, but the situation was resolved through the mediation of the moderate Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln

Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln (c. 1251February 1311), Baron of Pontefract, Lord of Bowland, Baron of Halton and hereditary Constable of Chester, was an English nobleman and confidant of King Edward I. He served Edward in Wales, France, and Sc ...

, who convinced the barons to back down. A fresh parliament was held in April, where the barons once again criticised Gaveston, demanding his exile, this time supported by Isabella and the French monarchy. Edward resisted, but finally acquiesced, agreeing to send Gaveston to Aquitaine, under threat of excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by the Archbishop of Canterbury should he return. At the last moment, Edward changed his mind and instead sent Gaveston to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, appointing him as the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

.

Edward called for a fresh military campaign for Scotland, but this idea was quietly abandoned, and instead the king and the barons met in August 1308 to discuss reform. Behind the scenes, Edward started negotiations to convince both Pope Clement V and Philip IV to allow Gaveston to return to England, offering in exchange to suppress the Knights Templar in England, and to release Bishop Langton from prison. Edward called a new meeting of members of the Church and key barons in January 1309, and the leading earls then gathered in March and April, possibly under the leadership of Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster

Thomas of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, 2nd Earl of Leicester, 2nd Earl of Derby, ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Lincoln and ''jure uxoris'' 5th Earl of Salisbury (c. 1278 – 22 March 1322) was an English nobleman. A member of the House of Pl ...

. Another parliament followed, which refused to allow Gaveston to return to England, but offered to grant Edward additional taxes if he agreed to a programme of reform.

Edward sent assurances to the Pope that the conflict surrounding Gaveston's role was at an end. On the basis of these promises, and procedural concerns about how the original decision had been taken, the Pope agreed to annul the Archbishop's threat to excommunicate Gaveston, thus opening the possibility of Gaveston's return. Gaveston arrived back in England in June, where he was met by Edward. At the parliament the next month, Edward made a range of concessions to placate those opposed to Gaveston, including agreeing to limit the powers of the royal steward and the marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

of the royal household, to regulate the Crown's unpopular powers of purveyance

Purveyance was an ancient prerogative right of the English Crown to purchase provisions and other necessaries for the royal household, at an appraised price, and to requisition horses and vehicles for royal use.{{Cite book , title=Osborn's Law ...

, and to abandon recently enacted customs legislation; in return, parliament agreed to fresh taxes for the war in Scotland. Temporarily, at least, Edward and the barons appeared to have come to a successful compromise.

Ordinances of 1311

Following his return, Gaveston's relationship with the major barons became increasingly difficult. He was considered arrogant, and he took to referring to the earls by offensive names, including calling one of their more powerful members the "dog of Warwick". The Earl of Lancaster and Gaveston's enemies refused to attend parliament in 1310 because Gaveston would be present. Edward was facing increasing financial problems, owing £22,000 to hisFrescobaldi

The Frescobaldi are a prominent Florentine noble family that have been involved in the political, social, and economic history of Tuscany since the Middle Ages. Originating in the Val di Pesa in the Chianti, they appear holding important posts ...

Italian bankers, and facing protests about how he was using his right of prise

Purveyance was an ancient prerogative right of the English Crown to purchase provisions and other necessaries for the royal household, at an appraised price, and to requisition horses and vehicles for royal use.{{Cite book , title=Osborn's Law ...

s to acquire supplies for the war in Scotland. His attempts to raise an army for Scotland collapsed and the earls suspended the collection of the new taxes.

The king and parliament met again in February 1310, and the proposed discussions of Scottish policy were replaced by debate of domestic problems. Edward was petitioned to abandon Gaveston as his counsellor and instead adopt the advice of 21 elected barons, termed Ordainers

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power of the English monarch. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the L ...

, who would carry out a widespread reform of both the government and the royal household. Under huge pressure, he agreed to the proposal and the Ordainers were elected, broadly evenly split between reformers and conservatives. While the Ordainers began their plans for reform, Edward and Gaveston took a new army of around 4,700 men to Scotland, where the military situation had continued to deteriorate. Robert the Bruce declined to give battle and the campaign progressed ineffectually over the winter until supplies and money ran out in 1311, forcing Edward to return south.

By now the Ordainers had drawn up their Ordinances for reform and Edward had little political choice but to give way and accept them in October. The Ordinances of 1311

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power of the English monarch. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the Lo ...

contained clauses limiting the king's right to go to war or to grant land without parliament's approval, giving parliament control over the royal administration, abolishing the system of prises, excluding the Frescobaldi bankers, and introducing a system to monitor the adherence to the Ordinances. In addition, the Ordinances exiled Gaveston once again, this time with instructions that he should not be allowed to live anywhere within Edward's lands, including Gascony and Ireland, and that he should be stripped of his titles. Edward retreated to his estates at Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

and Kings Langley

Kings Langley is a village, former Manorialism, manor and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Hertfordshire, England, north-west of Westminster in the historic centre of London and to the south of the Chiltern Hills. It now forms part o ...

; Gaveston left England, possibly for northern France or Flanders.

Mid-reign (1311–1321)

Death of Gaveston

Tensions between Edward and the barons remained high, and the earls opposed to the king kept their personal armies mobilised late into 1311. By now Edward had become estranged from his cousin, the Earl of Lancaster, who was also theEarl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

Early creations ...

, Lincoln, Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

, and Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

, with an income of around £11,000 a year from his lands, almost double that of the next wealthiest baron. Backed by the earls of Arundel

Arundel ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Arun District of the South Downs, West Sussex, England.

The much-conserved town has a medieval castle and Roman Catholic cathedral. Arundel has a museum and comes second behind much large ...

, Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

, Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

, Pembroke, and Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

, Lancaster led a powerful faction in England, but he was not personally interested in practical administration, nor was he a particularly imaginative or effective politician.

Edward responded to the baronial threat by revoking the Ordinances and recalling Gaveston to England, being reunited with him at York in January 1312. The barons were furious and met in London, where Gaveston was excommunicated by the Archbishop of Canterbury and plans were put in place to capture Gaveston and prevent him from fleeing to Scotland. Edward, Isabella, and Gaveston left for Newcastle, pursued by Lancaster and his followers. Abandoning many of their belongings, the royal party fled by ship and landed at Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

, where Gaveston stayed while Edward and Isabella returned to York. After a short siege, Gaveston surrendered to the earls of Pembroke and Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, on the promise that he would not be harmed. He had with him a huge collection of gold, silver, and gems, probably part of the royal treasury, which he was later accused of having stolen from Edward.

On the way back from the north, Pembroke stopped in the village of Deddington

Deddington is a civil parish and small town in Oxfordshire about south of Banbury. The parish includes two hamlets: Clifton and Hempton. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 2,146. Deddington is a small settlement but has a c ...

in the Midlands, putting Gaveston under guard there while he went to visit his wife. The Earl of Warwick took this opportunity to seize Gaveston, taking him to Warwick Castle

Warwick Castle is a medieval castle developed from a wooden fort, originally built by William the Conqueror during 1068. Warwick is the county town of Warwickshire, England, situated on a meander of the River Avon. The original wooden motte-an ...

, where the Earl of Lancaster and the rest of his faction assembled on 18 June. At a brief trial, Gaveston was declared guilty of being a traitor under the terms of the Ordinances; he was executed on Blacklow Hill

Leek Wootton is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Leek Wootton and Guy's Cliffe, in the Warwick district, in the county of Warwickshire, England, approximately 2 miles south of Kenilworth and 2.5 miles north of Warwick. It ...

the following day, under the authority of Lancaster. Gaveston's body was not buried until 1315, when his funeral was held in King's Langley Priory.

Tensions with Lancaster and France