Edward O'Hare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lieutenant Commander Edward Henry O'Hare (March 13, 1914 – November 26, 1943) was an American

Edward Henry "Butch" O'Hare was born in

Edward Henry "Butch" O'Hare was born in

O'Hare's most famous flight occurred during the

O'Hare's most famous flight occurred during the

On March 26, O'Hare was greeted at Pearl Harbor by a horde of reporters and radio announcers. During a radio broadcast in Honolulu, he enjoyed the opportunity to say hello to his wife Rita ("Here's a great big radio hug, the best I can do under the circumstances") and to his mother ("Love from me to you").Ewing and Lundstrom 1987, p. 151. On April 8, he thanked the

On March 26, O'Hare was greeted at Pearl Harbor by a horde of reporters and radio announcers. During a radio broadcast in Honolulu, he enjoyed the opportunity to say hello to his wife Rita ("Here's a great big radio hug, the best I can do under the circumstances") and to his mother ("Love from me to you").Ewing and Lundstrom 1987, p. 151. On April 8, he thanked the

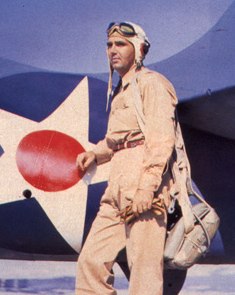

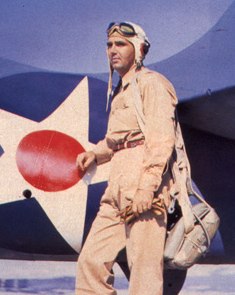

O'Hare was not employed on combat duty from early 1942 until late 1943. Important events in this period included flying an F4F-3A Wildcat (BuNo 3986 "White F-13") as Lieutenant Commander 'Jimmy' Thach's wingman for publicity footage on April 11, 1942, the Medal of Honor presentation at the White House on April 21, and the welcome parade in O'Hare's hometown on Saturday, April 25, 1942.

The welcome parade was held in St. Louis. At the starting point, O'Hare, wearing the blue-ribboned Medal of Honor around his neck, was guided to the back seat of a black open

O'Hare was not employed on combat duty from early 1942 until late 1943. Important events in this period included flying an F4F-3A Wildcat (BuNo 3986 "White F-13") as Lieutenant Commander 'Jimmy' Thach's wingman for publicity footage on April 11, 1942, the Medal of Honor presentation at the White House on April 21, and the welcome parade in O'Hare's hometown on Saturday, April 25, 1942.

The welcome parade was held in St. Louis. At the starting point, O'Hare, wearing the blue-ribboned Medal of Honor around his neck, was guided to the back seat of a black open  On March 2, 1943, O'Hare met Rita and hugged his one-month-old daughter, Kathleen, for the first time. His family resided in

On March 2, 1943, O'Hare met Rita and hugged his one-month-old daughter, Kathleen, for the first time. His family resided in

On October 10, 1943, O'Hare flew with VF-6 again in the airstrikes against Wake Island. On this mission, the future ace Lt.(jg) Alex Vraciu was his wingman – both Butch and Vraciu shot down one enemy plane that day. When they came across an enemy formation Butch took the outside aeroplane and Vraciu took the inside plane. Butch went below the clouds to get a Japanese

On October 10, 1943, O'Hare flew with VF-6 again in the airstrikes against Wake Island. On this mission, the future ace Lt.(jg) Alex Vraciu was his wingman – both Butch and Vraciu shot down one enemy plane that day. When they came across an enemy formation Butch took the outside aeroplane and Vraciu took the inside plane. Butch went below the clouds to get a Japanese

naval aviator

Naval aviation / Aeronaval is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

It often involves '' navalised aircraft'', specifically designed for naval use.

Seaborne aviation encompas ...

of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, who on February 20, 1942, became the Navy's first fighter ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

of the war when he single-handedly attacked a formation of nine medium bombers approaching his aircraft carrier. Although he had a limited amount of ammunition, O'Hare was credited with shooting down five enemy bombers and became the first naval aviator recipient of the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

O'Hare's final action took place on the night of November 26, 1943, while he was leading the U.S. Navy's first-ever nighttime fighter attack launched from an aircraft carrier. During this encounter with a group of Japanese torpedo bombers, O'Hare's Grumman F6F Hellcat

The Grumman F6F Hellcat is an American Carrier-based aircraft, carrier-based fighter aircraft of World War II. Designed to replace the earlier Grumman F4F Wildcat, F4F Wildcat and to counter the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero, it was the United St ...

was shot down; his aircraft was never found. A radio message was sent out, but there was no response. In 1945, the U.S. Navy destroyer was named in his honor.

On September 19, 1949, the Chicago-area Orchard Field Airport was renamed O'Hare International Airport

Chicago O'Hare International Airport is the primary international airport serving Chicago, Illinois, United States, located on the city's Northwest Side, approximately northwest of the Chicago Loop, Loop business district. The airport is ope ...

, six years after O'Hare perished. An F4F Wildcat, in a livery identical to the aircraft ("White F-15") flown by O'Hare, is on display in Terminal 2. The display was formally opened on the seventy-fifth anniversary of his Medal of Honor flight.

Early life

Edward Henry "Butch" O'Hare was born in

Edward Henry "Butch" O'Hare was born in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

, the son of Selma Anna (Lauth) and Edward Joseph O'Hare. He was of Irish and German descent. Butch had two sisters, Patricia and Marilyn. When their parents divorced in 1927, Butch and his sisters stayed with Selma in St. Louis while Edward moved to Chicago. Butch's father was a lawyer who worked closely with Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone ( ; ; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American organized crime, gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-foun ...

before turning against him and helping convict Capone of tax evasion

Tax evasion or tax fraud is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to red ...

.

Butch O'Hare graduated from the Western Military Academy in 1932. The following year, he went on to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

at Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

. After O'Hare graduated and was commissioned as an ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

on June 3, 1937, he served two years on the battleship . In 1939, O'Hare started flight training at NAS Pensacola

Naval Air Station Pensacola or NAS Pensacola (formerly NAS/KNAS until changed circa 1970 to allow Nassau International Airport, now Lynden Pindling International Airport, to have IATA code NAS), "The Cradle of Naval Aviation", is a United Sta ...

in Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, flying the Naval Aircraft Factory N3N-1 "Yellow Peril" and Stearman Stearman is a surname. Notable people with the name include:

* Josiah Stearman (born 2003), American chess master

* Lloyd Stearman (1898–1975), American aviation pioneer

* Richard Stearman (born 1987), English footballer

* William Stearman ( ...

NS-1 biplane trainers, and later the advanced SNJ trainer. On the nimble Boeing F4B-4A, he trained in aerobatics as well as aerial gunnery. O'Hare also flew the SBU Corsair and the TBD Devastator

The Douglas TBD Devastator is a retired American torpedo bomber of the United States Navy. Ordered in 1934, it first flew in 1935 and entered service in 1937. At that point, it was the most advanced aircraft flying for the Navy, being the firs ...

.

In November 1939, O'Hare's father was shot and killed, most likely by Al Capone's gunmen. During Capone's tax evasion trial in 1931 and 1932, Edward O'Hare had provided incriminating evidence which helped finally put Capone away. There is speculation

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, good (economics), goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable in a brief amount of time. It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hope ...

that this was done to ensure that Butch got into the Naval Academy, or to set a good example; it certainly at least partly involved an attempt to distance himself from Capone's activities. Whatever the motivation, the elder O'Hare was shot and killed while driving his car a week before Capone was released from incarceration.

When Butch finished his naval aviation

Naval aviation / Aeronaval is the application of Military aviation, military air power by Navy, navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

It often involves ''navalised aircraft'', specifically designed for naval use.

Seab ...

training on May 2, 1940, he was assigned to Fighter Squadron Three (VF-3) on board . O'Hare then trained on the Grumman F3F

The Grumman F3F is a biplane fighter aircraft produced by the Grumman aircraft for the United States Navy during the mid-1930s. Designed as an improvement on the F2F, it entered service in 1936 as the last biplane to be delivered to any American ...

and then graduated to the Brewster F2A

The Brewster F2A Buffalo is an American fighter aircraft which saw service early in World War II. Designed and built by the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation, it was one of the first U.S. monoplanes with an arrestor hook and other modification ...

Buffalo. Lieutenant John Thach, then executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.

In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer ...

of VF-3, discovered O'Hare's exceptional flying abilities and closely mentored the promising young pilot. Thach, who would later develop the Thach Weave

The Thach weave (also known as a beam defense position) is an aerial combat tactic that was developed by naval aviator John S. Thach and named by James H. Flatley of the United States Navy soon after the United States' entry into Wo ...

aerial combat tactic, emphasized gunnery in his training. In 1941, more than half of all VF-3 pilots, including O'Hare, earned the "E" for gunnery excellence.

In early 1941, VF-3 transferred to , while carrier ''Saratoga'' underwent maintenance and overhaul work at Bremerton Navy Yard.

On Monday morning, July 21, O'Hare made his first flight in a Grumman F4F Wildcat

The Grumman F4F Wildcat is an American carrier-based

A carrier-based aircraft (also known as carrier-capable aircraft, carrier-borne aircraft, carrier aircraft or aeronaval aircraft) is a naval aircraft designed for operations from aircra ...

. Following stops in Washington and Dayton, he landed in St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

the next day. Visiting the wife of a friend in hospital that afternoon, O'Hare met his future wife, nurse Rita Wooster, proposing to her the first time they met. After O'Hare took instruction in Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

to convert, he and Rita married in St. Mary's Catholic Church in Phoenix on Saturday, September 6, 1941. For their honeymoon, they sailed to Hawaii on separate ships, Butch on ''Saratoga'', which had completed modifications at Bremerton, and Rita on the Matson liner . Butch was called to duty the day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

On Sunday evening, January 11, 1942, as Butch and other VF-3 officers ate dinner in the wardroom, the carrier ''Saratoga'' was damaged by a Japanese torpedo hit while patrolling southwest of Hawaii. She spent five months in repair on the west coast, so VF-3 squadron transferred to the on January 31.

World War II service

Medal of Honor flight

O'Hare's most famous flight occurred during the

O'Hare's most famous flight occurred during the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

on February 20, 1942. He and his wingman

A wingman (or wingmate) is the pilot of a secondary aircraft providing support or protection to a primary aircraft in a potentially dangerous situation, traditionally flying in formation to the side and slightly behind the primary craft. The t ...

were the only U.S. Navy fighters available when a second wave of Japanese bombers were attacking his aircraft carrier ''Lexington''.

O'Hare was on board the aircraft carrier ''Lexington'', which had been assigned the task of penetrating enemy-held waters north of New Ireland. While still from the harbor at Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in the province ...

, at 10:15, the ''Lexington'' picked up an unknown aircraft on radar from the ship. A six-plane combat patrol was launched, two fighters being directed to investigate the contact. These two planes, under command of LCDR. John Thach, shot down a four-engined Kawanishi H6K

The Kawanishi H6K was an Imperial Japanese Navy flying boat produced by the Kawanishi Aircraft Company and used during World War II for maritime patrol duties. The Allied reporting name for the type was Mavis; the Navy designation was .

Develo ...

4 Type 97 ("Mavis") flying boat about out at 11:12. Later two other planes of the combat patrol were sent to another radar contact ahead, shooting down a second "Mavis" at 12:02. A third contact was made out, but reversed course and disappeared. At 15:42, a jagged vee signal drew the attention of the ''Lexington''s radar operator. The contact then was lost but reappeared at 16:25 west. O'Hare, flying F4F Wildcat BuNo 4031 "White F-15", was one of several pilots launched to intercept nine Japanese Mitsubishi G4M

The Mitsubishi G4M is a twin-engine, land-based medium bomber formerly manufactured by the Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and operated by the Air Service (IJNAS) of the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to ...

"Betty" bombers from the 4th Kōkūtai

A ''kōkūtai'' () was a military aviation unit in the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS), similar to the Group (military aviation unit), air groups in other air arms and services of the time. Some comparable units included ''wing'' in th ...

's 2nd Chutai. O'Hare's squadmates shot down eight bombers (with the ninth falling to an SBD later), but he and his wingman, Marion "Duff" Dufilho, were held back in the event of a second attack.

At 16:49, the ''Lexington''s radar picked up a second formation of "Bettys" from the 4th Kōkūtai's 1st Chutai, only out, on the disengaged side of the task force. With the majority of VF-3 still chasing the 2nd Chutai, only O'Hare and Dufilho were available to intercept. Flying eastward they arrived above the "Bettys" out at 17:00. Dufilho's guns jammed, leaving only O'Hare to protect the carrier. The enemy was in a V-of-Vs formation, flying very close together and using their rear-facing 20mm cannon for mutual protection. O'Hare's Wildcat was armed with four 50-caliber guns, with 450 rounds per gun, giving him about 10 three-second bursts.

O'Hare's initial maneuver was a high-side diving attack from the formation's starboard side employing deflection shooting

Deflection shooting is a technique of shooting ahead of a moving target, also known as leading the target, so that the projectile will "intercept" and collide with the target at a predicted point. This technique is necessary when the target will ...

. He managed to hit the outside "Betty"s right engine and wing fuel tanks; when the stricken craft of Petty Officer 2nd Class Ryosuke Kogiku (3rd Shotai)Ewing and Lundstrom 1997, p. 130 abruptly lurched to starboard, he switched to the next plane up the line, that of Petty Officer 1st Class Koji Maeda (3rd Shotai leader). Maeda's plane caught fire, but his crew managed to put out the flames with "one single spurt of liquid ... from the fire-extinguisher" Both Maeda and Kogiku would catch up with the group before bomb release.

With two "Bettys" out of formation (albeit temporarily), O'Hare began his second firing pass, this time from the port side. His first target was the outside plane, flown by Petty Officer 1st Class Bin Mori (2nd Shotai). O'Hare's bullets damaged the right engine and left fuel tank, forcing Mori to dump his bombs and abort his mission.Ewing and Lundstrom 1997, p.131 O'Hare then targeted the plane of Petty Officer 1st Class Susumu Uchiyama (1st Shotai), which became his first definite kill.

As O'Hare began his third firing pass, again from the port side, the remaining "Bettys" were nearing their bomb release point. First, O'Hare shot down Lieutenant (junior grade) Akira Mitani (2nd Shotai leader). This left the lead plane, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Takuzo Ito, exposed. O'Hare's concentrated fire caused the plane's port engine nacelle

A nacelle ( ) is a streamlined container for aircraft parts such as Aircraft engine, engines, fuel or equipment. When attached entirely outside the airframe, it is sometimes called a pod, in which case it is attached with a Hardpoint#Pylon, pylo ...

to break free from its mountings and fall from the plane. The resulting explosion was so violent that the 1st Chutai pilots were convinced that an anti-aircraft burst had struck their commander's plane. With a gaping hole in its left wing, Ito's plane fell out of formation.

Shortly afterwards, O'Hare made a fourth firing pass, likely against Maeda (who had now caught up), but ran out of ammunition. Frustrated, he pulled away to allow the ships to fire their anti-aircraft guns. The four surviving bombers dropped their ordnance, but all their 250 kg bombs missed. O'Hare believed he had shot down six bombers and damaged a seventh. Captain Sherman would later reduce this to five, as four of the reported nine bombers were still overhead when he pulled off. Thach, hurrying towards the scene with reinforcements after mopping up the 2nd ''Chûtai'', saw three enemy bombers falling in flames at the same time.

In fact, O'Hare destroyed only three "Bettys": Uchiyama's, Mitani's, and Ito's. The last plane, however, was not yet finished. Ito's command pilot, Warrant Officer Chuzo Watanabe,Group leader Takuzo Ito was not piloting his own "Betty". As per standard practice in the IJNAF, the pilot was an enlisted man, and the commander of the plane was an observer and/or navigator. regained enough control to level his damaged plane and attempted to crash it into ''Lexington''. He missed, and flew into the water near the carrier at 17:12. Another three "Bettys" were damaged by O'Hare's attacks. Of these, Maeda and Kogiku safely landed at Vunakanau airdrome at 19:50, while Mori became lost in a storm and eventually ditched at Simpson Harbor at 20:10.

With his ammunition expended, O'Hare returned to his carrier, and was fired on accidentally but with no effect by a .50-caliber machine gun from the ''Lexington''. O'Hare's fighter had, in fact, been hit by only one bullet during his flight, the single bullet hole in F-15's port wing disabling the airspeed indicator. According to Thach, O'Hare then approached the gun platform to calmly say to the embarrassed anti-aircraft gunner who had fired at him, "Son, if you don't stop shooting at me when I've got my wheels down, I'm going to have to report you to the gunnery officer."

In the opinion of Admiral Brown and of Captain Frederick C. Sherman, commanding the ''Lexington'', Lieutenant O'Hare's actions may have saved the carrier from serious damage or even loss. By 19:00 all ''Lexington'' planes had been recovered except for two F4F-3 Wildcats shot down while attacking enemy bombers; both were lost while making steady, no-deflection runs from astern of their targets. The pilot of one fighter was rescued, the other went down with his aircraft.

The F4F Wildcat O'Hare flew was BuNo. 4031 as discovered in his aviator’s logbook, while its side number was found out to be F-15 based on Captain Burt Stanley's diary. After ''Lexington'' returned to port, 4031 was transferred to VF-2 and flew from ''Lexington'' at Coral Sea. It was one of the six VF-2 Wildcats to survive ''Lexington''‘s sinking, as it landed on ''Yorktown''. After Coral Sea, it served in VF-42 and later Marine Air Group 23 before being struck off charge in July 1944.

Accolades

On March 26, O'Hare was greeted at Pearl Harbor by a horde of reporters and radio announcers. During a radio broadcast in Honolulu, he enjoyed the opportunity to say hello to his wife Rita ("Here's a great big radio hug, the best I can do under the circumstances") and to his mother ("Love from me to you").Ewing and Lundstrom 1987, p. 151. On April 8, he thanked the

On March 26, O'Hare was greeted at Pearl Harbor by a horde of reporters and radio announcers. During a radio broadcast in Honolulu, he enjoyed the opportunity to say hello to his wife Rita ("Here's a great big radio hug, the best I can do under the circumstances") and to his mother ("Love from me to you").Ewing and Lundstrom 1987, p. 151. On April 8, he thanked the Grumman

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, later Grumman Aerospace Corporation, was a 20th century American producer of military and civilian aircraft. Founded on December 6, 1929, by Leroy Grumman and his business partners, it merged in 19 ...

Aircraft Corporation plant at Bethpage (where the F4F Wildcat was made) for 1,150 cartons of Lucky Strike

Lucky Strike is an American brand of cigarettes owned by the British American Tobacco group. Individual cigarettes of the brand are often referred to colloquially as "Luckies."

Name

Lucky Strike was introduced as a brand of plug tobacco (chew ...

cigarettes, a grand total of 230,000 smokes. Ecstatic Grumman workers had passed the hat to buy the cigarettes in appreciation of O'Hare's combat victories in one of their F4F Wildcats. A loyal Camel

A camel (from and () from Ancient Semitic: ''gāmāl'') is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provid ...

smoker, O'Hare opened a carton, deciding that it was the least he could do for the good people back in Bethpage. In his letter to the Grumman employees he wrote, "You build them, we'll fly them and between us, we can't be beaten." It was a sentiment he would voice often in the following two months.

Credited with shooting down five bombers, O'Hare became a flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

, was selected for promotion to lieutenant commander, and became the first naval aviator to receive the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

. With President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

looking on, O'Hare's wife Rita placed the Medal around his neck. After receiving the Medal of Honor, then-Lieutenant O'Hare was described as "modest, inarticulate, humorous, terribly nice and more than a little embarrassed by the whole thing".

O'Hare received further decorations later in 1943 for actions in battles near Marcus Island in August and subsequent missions near Wake Island

Wake Island (), also known as Wake Atoll, is a coral atoll in the Micronesia subregion of the Pacific Ocean. The atoll is composed of three islets – Wake, Wilkes, and Peale Islands – surrounding a lagoon encircled by a coral reef. The neare ...

in October.

Non-combat duty

O'Hare was not employed on combat duty from early 1942 until late 1943. Important events in this period included flying an F4F-3A Wildcat (BuNo 3986 "White F-13") as Lieutenant Commander 'Jimmy' Thach's wingman for publicity footage on April 11, 1942, the Medal of Honor presentation at the White House on April 21, and the welcome parade in O'Hare's hometown on Saturday, April 25, 1942.

The welcome parade was held in St. Louis. At the starting point, O'Hare, wearing the blue-ribboned Medal of Honor around his neck, was guided to the back seat of a black open

O'Hare was not employed on combat duty from early 1942 until late 1943. Important events in this period included flying an F4F-3A Wildcat (BuNo 3986 "White F-13") as Lieutenant Commander 'Jimmy' Thach's wingman for publicity footage on April 11, 1942, the Medal of Honor presentation at the White House on April 21, and the welcome parade in O'Hare's hometown on Saturday, April 25, 1942.

The welcome parade was held in St. Louis. At the starting point, O'Hare, wearing the blue-ribboned Medal of Honor around his neck, was guided to the back seat of a black open Packard

Packard (formerly the Packard Motor Car Company) was an American luxury automobile company located in Detroit, Michigan. The first Packard automobiles were produced in 1899, and the last Packards were built in South Bend, Indiana, in 1958.

One ...

Phaeton, where he sat between his wife Rita and his mother Selma. The parade began at noon, led by a police motorcycle escort, then came the band from Jefferson Barracks, marching veterans, a truck packed with photographers, O'Hare's Phaeton (with a six-man Marine honor guard alongside) and other open cars. Bringing up the rear was the entire 350-member student body of Western Military Academy. St. Louis Mayor William Dee Becker presented O'Hare with a gold navigator's four-dial watch engraved with the words "To Lt. Commander Edward H. O'Hare, USN, from a proud and grateful City of St. Louis, April 25, 1942". As O'Hare's mother and his sisters clipped newspaper stories and photos the following days, his place in history began to dawn on them. A newspaper headline read, "60,000 give O'Hare a hero's welcome here." The United States in 1942 badly needed a live hero, and Butch O'Hare was a young, handsome naval aviator, so he participated in several war bond

War bonds (sometimes referred to as victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are Security (finance)#Debt, debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an un ...

tours the following months.

On June 19, 1942, O'Hare assumed command of VF-3, relieving Lieutenant Commander Thach. He was relocated to Maui, Hawaii

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

, to instruct other pilots in combat tactics. U.S. Navy policy was to use its best combat pilots to train newer pilots, in contrast to the Japanese practice of keeping their best pilots flying combat missions. Ensign Edward L. "Whitey" Feightner, who served with O'Hare in July 1942, later said that one of the best pieces of information O'Hare passed on to him, was:

O'Hare also related

An anecdote

An anecdote is "a story with a point", such as to communicate an abstract idea about a person, place, or thing through the concrete details of a short narrative or to characterize by delineating a specific quirk or trait.

Anecdotes may be real ...

about O'Hare, serving as an instructor on Hawaii mid-1942:

On March 2, 1943, O'Hare met Rita and hugged his one-month-old daughter, Kathleen, for the first time. His family resided in

On March 2, 1943, O'Hare met Rita and hugged his one-month-old daughter, Kathleen, for the first time. His family resided in Coronado Coronado may refer to:

People

* Coronado (surname) Coronado is a Spanish surname derived from the village of Cornado, near A Coruña, Galicia.

People with the name

* Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (1510–1554), Spanish explorer often referred t ...

at 549 Orange Avenue, near North Island NAS. At the end of March 1943, O'Hare made Ensign Alexander Vraciu, a young Naval Reservist just out of flight school, his wingman. On July 15, VF-3 swapped designations with VF-6 squadron.

Return to combat

Equipped with the highly successful follow-on to the Wildcat, the new Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat, two-thirds of VF-6 (twenty-four F6F-3s) under O'Hare's command embarked on August 22, 1943, on the light carrier . The arrival of the F6Fs with their powerfulPratt & Whitney R-2800

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp is an American twin-row, 18-cylinder, air-cooled radial aircraft engine with a engine displacement, displacement of , and is part of the long-lived Pratt & Whitney Wasp series, Wasp family of engines.

...

radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating engine, reciprocating type internal combustion engine, internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinder (engine), cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. ...

s in late 1943, combined with the deployment of the new carriers and the carriers, immediately gave the U.S. Pacific Fleet air supremacy wherever the Fast Carrier Force operated. The Hellcat's first combat mission occurred on August 31, 1943, in a strike against Marcus Island. The F6F did well against Japanese fighters and proved that with the right tactics and teamwork the Japanese Zero need not be considered a superior enemy. VF-6's combat debut on the ''Independence'' also went reasonably well. For his actions in battles near Marcus Island on August 31, O'Hare was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. For his actions in subsequent missions near Wake Island on October 5, O'Hare was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of a second Distinguished Flying Cross.

On October 10, 1943, O'Hare flew with VF-6 again in the airstrikes against Wake Island. On this mission, the future ace Lt.(jg) Alex Vraciu was his wingman – both Butch and Vraciu shot down one enemy plane that day. When they came across an enemy formation Butch took the outside aeroplane and Vraciu took the inside plane. Butch went below the clouds to get a Japanese

On October 10, 1943, O'Hare flew with VF-6 again in the airstrikes against Wake Island. On this mission, the future ace Lt.(jg) Alex Vraciu was his wingman – both Butch and Vraciu shot down one enemy plane that day. When they came across an enemy formation Butch took the outside aeroplane and Vraciu took the inside plane. Butch went below the clouds to get a Japanese Mitsubishi Zero

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range Carrier-based aircraft, carrier-capable fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) ...

and Vraciu lost him, so Vraciu kept an eye on a second Zero that went to Wake Island and landed. Vraciu strafed the Zero on the ground, then saw a "Betty" bomber and shot it down. Upon returning to the carrier, O'Hare asked Vraciu where he went and Vraciu knew then that he should have definitely stayed with his leader. Alex Vraciu later said after the war, "O'Hare taught many of the squadron members little things that would later save their lives. One example was to swivel your neck before starting a strafing run to make sure enemy fighters were not on your tail." Vraciu also learned from O'Hare the "high side pass" used for attacking the G4M "Betty" bombers. The high side technique was used to avoid the lethal 20 mm fire of the "Betty"s tail gunner. The Wake Island raid would be the last occasion Butch would lead VF-6 in battle. According to orders dated September 17, 1943, October found O'Hare as Commander Air Group (CAG) commanding Air Group Six, embarked on USS ''Enterprise''. Functioning as CAG, O'Hare was given command of the entire ''Enterprise'' air group: Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, Douglas SBD Dauntless

The Douglas SBD Dauntless is a World War II American naval scout plane and dive bomber that was manufactured by Douglas Aircraft from 1940 through 1944. The SBD ("Scout Bomber Douglas") was the United States Navy's main Carrier-based aircraft, ...

dive bombers, Grumman TBF Avenger

The Grumman TBF Avenger (designated TBM for aircraft manufactured by General Motors) is an American World War II-era torpedo bomber developed initially for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, and eventually used by several air and naval a ...

torpedo bombers and 100 pilots.

Now overseeing three squadrons, O'Hare still insisted that everyone call him "Butch". O'Hare's VF-6 squadron would "still stay broken up" among three light aircraft carrier

A light aircraft carrier, or light fleet carrier, is an aircraft carrier smaller than the Fleet carrier, standard carriers of a navy. The precise definition of the type varies by country; light carriers typically have a complement of aircraft onl ...

s, the squadron had made itself just too useful filling out the light carrier air groups, and AirPac had no well-trained replacements on hand. As a result, Fighting Squadron Two (VF-2) boarded the USS ''Enterprise'' from November 1943 and became Butch's new Fighting Squadron. While he readied his new air group, he suffered what he intended as only a temporary separation from his beloved VF-6 "Felix the Cat" Squadron. The news, that the commanding officer had to leave them, hit the men of VF-6 hard. O'Hare first flew a TBM-1 Avenger as CAG-6 command aircraft with bombardier Del Delchamps, AOM1/c and radioman Hal Coleman as crew members. With its good radio facilities, docile handling, and long-range, the Grumman Avenger made an ideal command aircraft for Air Group Commanders (CAGs), but Butch considered the Grumman torpedo bomber as a 'lame turkey' compared to the Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter.

Later Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford honored a request from O'Hare to take a fighter as command aircraft instead of the Avenger, so O'Hare in a fateful decision happily drew Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat Bureau Number 66168 from the fleet pool to become his principal CAG plane, numbered "00". From 20 – November 23, 1943, the U.S. forces landed in the Gilberts

The Gilbert Islands (;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this name applied o ...

(Tarawa

Tarawa is an atoll and the capital of the Republic of Kiribati,Kiribati

''

''

Makin), and the ''Enterprise'' joined in providing close air support to the Marines landing on Makin Island. Equipped with the Grumman F6F Hellcat, the U.S. Navy fighter pilots could protect the fleet from attacking Japanese aircraft.

Colonel Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the ''

Colonel Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the ''

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ohare, Edward 1914 births 1940s missing person cases 1943 deaths American people of German descent American people of Irish descent American World War II flying aces Aviators killed by being shot down Aviators from Missouri Catholics from Illinois Military personnel from St. Louis Missing in action of World War II Missing American people Military personnel from Chicago People lost at sea Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) United States Naval Academy alumni United States Naval Aviators United States Navy Medal of Honor recipients United States Navy officers United States Navy personnel killed in World War II World War II recipients of the Medal of Honor

Final mission and death

Faced with U.S. daylightair superiority

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmospher ...

, the Japanese quickly developed tactics to send torpedo-armed "Betty" bombers on night missions from their bases in the Marianas

The Mariana Islands ( ; ), also simply the Marianas, are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly Volcano#Dormant and reactivated, dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean ...

against the U.S. aircraft carriers. In late November they launched these low-altitude strikes almost nightly to attack ''Enterprise'' and other American ships, so Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford, O'Hare and Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

Tom Hamilton, CV-6 air officer, were deeply involved in developing ad hoc counter-tactics, the first carrier-based night fighter operations of the U.S. Navy. O'Hare's plan required the carrier's Fighter Director Officer (FDO) to spot incoming enemy formations at a distance and send a "Bat Team" section consisting of a Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber and two Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters toward the Japanese intruders. Although improvements in new types of aviation radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

were soon forthcoming from the engineers at MIT and the electronic industry, the available primitive radars in 1943 were very bulky, attributed to the fact that they contained vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

technology. Radars were carried only on the roomy TBF Avengers, but not on the smaller and faster Hellcats, so the radar-equipped TBF Avenger would lead the Hellcats into position behind the incoming bombers, close enough for the F6F pilots to spot visually the blue exhaust flames of the Japanese bombers. Finally, the Hellcats would close in and shoot down the torpedo-carrying bombers.

One of the four "Bat Team" fighter pilots to conduct these experimental night fighter operations to intercept and destroy enemy bombers attacking Allied landing forces was then-LT Roy Marlin Voris, who after the war founded and commanded the Navy's flight demonstration squadron, the Blue Angels

The Blue Angels, formally named the U.S. Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, are a Aerobatics, flight demonstration squadron of the United States Navy.. Blue Angels official site. Formed in 1946, the unit is the second oldest formal aerobatics ...

.

On the night of November 26, 1943, the ''Enterprise'' introduced the experiment in the co-operative control of Avengers and Hellcats for night fighting, when the three-plane team from the ship broke up a large group of land-based bombers attacking Task Group TG 50.2. O'Hare volunteered to lead this mission to conduct the first-ever Navy nighttime fighter attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O'Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. He was dressed in loose marine coveralls. The night fighter unit consisting of 1 VT and 2 VF was catapulted between 17:58 and 18:01. The pilots for this flight were Butch O'Hare and Ensign Warren Andrew "Andy" Skon of VF-2 in F6Fs and the Squadron Commander of VT-6, LCDR John C. Phillips in a TBF-1C. The crew of the TBF torpedo plane consisted of LTJG Hazen B. Rand, a radar specialist and Alvin Kernan, A. B., AOM1/c. The "Black Panthers", as the night fighters were dubbed, took off before dusk and flew out into the incoming mass of Japanese planes.

Confusion and complications endangered the success of the mission. The Hellcats first had trouble finding the Avenger, the FDO had difficulty guiding any of them on the targets. O'Hare and Ensign W. Skon in their F6F Hellcats finally got into position behind the Avenger. Butch O'Hare had been well aware of the deadly danger of friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy or hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while ...

in this situation – he radioed to the Avenger pilot of his section, "Hey, Phil, turn those running lights on. I want to be sure it's a yellow devil I'm drilling."

O'Hare was last seen at the 5 o'clock position of the TBF. About that time, the turret gunner of the TBF, Alvin Kernan (AOM1/c) noticed a Japanese G4M "Betty" bomber above and almost directly behind O'Hare's 6 o'clock position. Kernan opened fire with the TBF's .50 cal. machine gun in the dorsal turret and a Japanese gunner fired back. O'Hare's F6F Hellcat apparently was caught in a crossfire. Seconds later O'Hare's F6F slid out of formation to port, pushing slightly ahead at about and then vanished in the dark. The Avenger pilot, Lieutenant Commander Phillips, called repeatedly to O'Hare, but received no reply. Ensign Skon responded: "Mr Phillips, this is Skon. I saw Mr O'Hare's lights go out and, at the same instant, he seemed to veer off and slant down into darkness." Phillips later asserted, as the Hellcat dropped out of view, it seemed to release something that fell almost vertically at a speed too slow for anything but a parachute. Then something "whitish-gray" appeared below, perhaps the splash of the aircraft plunging into the sea.

Lieutenant Commander Phillips reported the position () to the ship. After dawn, a three-plane search was made, but no trace of O'Hare or his aircraft were found. On November 29, a PBY Catalina

The Consolidated Model 28, more commonly known as the PBY Catalina (U.S. Navy designation), is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft designed by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. In U.S. Army service, it was designated as the O ...

flying boat also conducted a search with no positive result, and O'Hare was reported missing in action.

For 54 years, there was no definitive answer as to whether O'Hare had been brought down by friendly fire or the Japanese bomber's nose gunner. In 1997, ''Fateful Rendezvous: The Life of Butch O'Hare'', by Steve Ewing and John B. Lundstrom (see References below) shed new light. Ewing and Lundstrom state that Japanese guns, and not Kernan's, killed O'Hare.

In Chapter 16, "What Happened to Butch", the authors write, "Butch fell to his old familiar adversary, a Betty. Most likely he died from or was immediately disabled by, a lucky shot from the forward observer crouched in the ''rikko's'' etty'sforward glassed-in nose ... the nose gunner's 7.7 mm slugs very likely penetrated Butch's cockpit from above on the port side and ahead of the F6F's armor plate." In the index, Ewing and Lundstrom flatly state that Kernan is "wrongly accused of shooting down Butch."

Ewing and Lundstrom point out that the "most influential and oft-cited" account of O'Hare's last mission came in a 1962 history of the ''Enterprise'' by CDR Edward P. Stafford, which relied on action reports and recollections of former ''Enterprise'' crew, but did not contain interviews with any of the living participants. By contrast, Ewing and Lundstrom came to their conclusions on what happened to Butch after interviewing the still-living survivors of O'Hare's last mission: F6F pilot Skon, TBF radar officer Rand, and TBF gunner Kernan. Ewing and Lundstrom write, "Through Stafford and other accounts based largely on the action reports, Butch has wrongly become known as one of America's most famous 'friendly fire' casualties."

On December 9, the official word arrived that O'Hare was missing in action. His mother Selma left for San Diego to be with his wife Rita and his daughter Kathleen. LCDR Bob Jackson wrote to Rita O'Hare from the ''Enterprise'' to describe the extensive but unsuccessful search for her husband. In the letter, LCDR Jackson quoted RADM Arthur W. Radford saying of Butch O'Hare that he "never saw one individual so universally liked." The hardest thing O'Hare's former wingman Alex Vraciu had to do was to talk to O'Hare's wife Rita after returning stateside. On December 20, 1943, a Solemn Pontifical Mass of Requiem

A Requiem (Latin: ''rest'') or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead () or Mass of the dead (), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the souls of the deceased, using a particular form of the Roman Missal. It is ...

was offered for Butch O'Hare at the St. Louis Cathedral.

As O'Hare went missing on November 26, 1943, and was declared dead a year later, his widow Rita received her husband's posthumous

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award, an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication, publishing of creative work after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1 ...

decorations, a Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the president to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, ...

and the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Naval Service's second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is equivalent to the Army ...

on November 26, 1944.

Honors and awards

Medal of Honor citation

Navy Cross citation

USS ''O'Hare''

On January 27, 1945, the United States Navy named a in his honor. The ship was launched June 22, 1945, with his mother, Selma O'Hare, as the sponsor. ''O'Hare'' was decommissioned on October 31, 1973, then transferred on loan and later sold to theSpanish Navy

The Spanish Navy, officially the Armada, is the Navy, maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation ...

. In 1992, the Spanish Navy decommissioned and scrapped the ship.

O'Hare International Airport

Colonel Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the ''

Colonel Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'', suggested that the name of Chicago's Orchard Depot Airport be changed as a tribute to O'Hare. On September 19, 1949, the airport was renamed O'Hare International Airport

Chicago O'Hare International Airport is the primary international airport serving Chicago, Illinois, United States, located on the city's Northwest Side, approximately northwest of the Chicago Loop, Loop business district. The airport is ope ...

to honor O'Hare's bravery. The airport displays a Grumman F4F-3 like the one flown during the Medal of Honor action.

The Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat on display was recovered virtually intact from the bottom of Lake Michigan, where it sank after a training accident in 1943 when it went off the training aircraft carrier . In 2001, the Air Classics Museum remodeled the aircraft to replicate the F4F-3 Wildcat that O'Hare flew on his Medal of Honor flight. The restored Wildcat is exhibited in the west end of Terminal 2 behind the security checkpoint to honor O'Hare International Airport's namesake.

Other honors

In September 1949, O'Hare's name was engraved on the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific "Wall of the Missing" in Honolulu. In March 1963, PresidentJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

performed a wreath-laying ceremony at O'Hare Airport to honor Butch O'Hare. The Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum is honoring O'Hare with an F4F-3A on display and a plaque dedicated by the USS ''Yorktown'' CV-10 association, "May Butch O'Hare rest in peace ...".

See also

* Edward J. O'Hare * List of aviators * List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War II *List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

Nile Kinnick

Throughout history, people have mysteriously disappeared at sea. The following is a list of known individuals who have mysteriously vanished in open waters, and whose whereabouts remain unknown. In most ocean deaths, bodies are never r ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

*"Air Classics", May 2003. * * * *"Edward Butch O'Hare". ''Legends of Airpower'' DVD, Episode #309. Frederick, MD: 3 Roads Communications, Inc., 2003. * *Shores, Christopher & Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho ''Krvavá jatka II''. Plzeň, Czech Republic: Mustang, 1995, (Czech translation of English ''Bloody Shambles Volume Two: The Complete Account of the Air War in the Far East, from the Defence of Sumatra to the Fall of Burma, 1942'')External links

* * * * *Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ohare, Edward 1914 births 1940s missing person cases 1943 deaths American people of German descent American people of Irish descent American World War II flying aces Aviators killed by being shot down Aviators from Missouri Catholics from Illinois Military personnel from St. Louis Missing in action of World War II Missing American people Military personnel from Chicago People lost at sea Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) United States Naval Academy alumni United States Naval Aviators United States Navy Medal of Honor recipients United States Navy officers United States Navy personnel killed in World War II World War II recipients of the Medal of Honor