Education in ancient Greece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Education for Greek people was vastly "democratized" in the 5th century B.C., influenced by the

Old Education in

Old Education in

Perseus program

* Lycurgus, Contra Leocratem. * * . See original text i

* * . See original text i

Sophists

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, and Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, Ἰσοκράτης ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education thro ...

. Later, in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, education in a gymnasium school was considered essential for participation in Greek culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these grou ...

. The value of physical education to the ancient Greeks and Romans has been historically unique. There were two forms of education in ancient Greece: formal and informal. Formal education was attained through attendance to a public school or was provided by a hired tutor. Informal education was provided by an unpaid teacher and occurred in a non-public setting. Education was an essential component of a person's identity.

Formal Greek education was primarily for males and non-slaves. In some poleis, laws were passed to prohibit the education of slaves.Ed. Sienkewicz, "Daily Life and Customs," ''Ancient Greece'' (New Jersey: Salem Press, I) The Spartans also taught music and dance, but with the purpose of enhancing their maneuverability as soldiers.

Athenian systems

Classical Athens (508–322 BCE)

Old education

Old Education in

Old Education in classical Athens

The city of Athens ( grc, Ἀθῆναι, ''Athênai'' .tʰɛ̂ː.nai̯ Modern Greek: Αθήναι, ''Athine'' or, more commonly and in singular, Αθήνα, ''Athina'' .'θi.na during the classical period of ancient Greece (480–323 BC) wa ...

consisted of two major parts – physical and intellectual, or what was known to Athenians as "''gymnastike''" and "''mousike''." ''Gymnastike'' was a physical education that mirrored the ideals of the military – strength, stamina, and preparation for war. Having a physically fit body was extremely important to the Athenians. Boys would begin physical education either during or just after beginning their elementary education. Initially, they would learn from a private teacher known as a ''paidotribes''. Eventually, the boys would begin training at the '' gymnasium''. Physical training was seen as necessary for improving one's appearance, preparation for war, and good health at an old age. On the other hand, ''mousike—''literally 'the art of the Muses'—was a combination of modern-day music, dance, lyrics, and poetry. Learning how to play the lyre, and sing and dance in a chorus were central components of musical education in Classical Greece. ''Mousike'' provided students with examples of beauty and nobility, as well as an appreciation of harmony and rhythm.

Students would write using a stylus

A stylus (plural styli or styluses) is a writing utensil or a small tool for some other form of marking or shaping, for example, in pottery. It can also be a computer accessory that is used to assist in navigating or providing more precision ...

, with which they would etch onto a wax tablet

A wax tablet is a tablet made of wood and covered with a layer of wax, often linked loosely to a cover tablet, as a "double-leaved" diptych. It was used as a reusable and portable writing surface in Antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages. ...

. When children were ready to begin reading whole works, they would often be given poetry to memorize and recite. Mythologies

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

such as those of Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the '' Iliad'' and the '' Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of ...

were also highly regarded by Athenians, and their works were often incorporated into lesson plans. Old Education lacked heavy structure and only featured schooling up to the elementary level. Once a child reached adolescence his formal education ended. Therefore, a large part of this education was informal and relied on simple human experience.

Higher education

It was not until about 420 BC that Higher Education became prominent inAthens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

.Aristophanes, ''Lysistrata and Other Plays'' (London: Penguin Classics, 2002), 65. Philosophers such as Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

(''c.'' 470–399 BCE), as well as the sophistic movement, which led to an influx of foreign teachers, created a shift from Old Education to a new Higher Education. This Higher Education expanded formal education, and Athenian society began to hold intellectual capacity in higher regard than physical. The shift caused controversy between those with traditional as opposed to modern views on education. Traditionalists believed that raising "intellectuals" would destroy Athenian culture, and leave Athens at a disadvantage in war. On the other hand, those in support of the change felt that while physical strength was important, its value in relation to Athenian power would diminish over time.Plutarch ''The Training of Children'', c. 110 CE (Ancient History Sourcebook), 5-6. Such people believed that education should be a tool to develop the whole man, including his intellect.Downey, "Ancient Education," ''The Classical Journal'' 52, no.8 (May 1980): 340. But Higher Education prevailed. The introduction of secondary and post-secondary levels of education provided greater structure and depth to the existing Old Education framework. More focused fields of study included mathematics, astronomy, harmonics and dialectic – all with an emphasis on the development of philosophical insight. It was seen as necessary for individuals to use knowledge within a framework of logic and reason.

Wealth played an integral role in classical Athenian Higher Education. In fact, the amount of Higher Education an individual received often depended on the ability and the family's willingness to pay for such an education. The formal programs within Higher Education were often taught by sophist

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ...

s who charged for their teaching. In fact, sophists extensively used advertisements in order to reach as many customers as possible. In most circumstances, only those who could afford the price could participate and the peasant class who lacked capital were limited in the education they could receive. Women and slaves were also barred from receiving an education. Societal expectations limited women mostly to the home, and the widely-held belief that women have inferior intellectual capacity caused them to have no access to formal education. Slaves were legally disallowed access to education. Women, while expected to stay at home and fulfill the role of a housewife, were still educated in such aspects. At about the age of seven, where boys and girls would exhibit distinct differentiation between sexes, girls were taught by their mothers the specific tasks related to a housewife as well as other moral education.

After Greece became part of the Roman Empire, educated Greeks were used as slaves by affluent Romans – indeed this was the primary way in which affluent Romans were educated. This led to the continuation of Greek culture in the Roman sphere.

Classical Athenian educators

= Isocrates (436–338 BC)

=Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, Ἰσοκράτης ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education thro ...

was an influential classical Athenian orator. Growing up in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

exposed Isocrates to educators such as Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

and Gorgias

Gorgias (; grc-gre, Γοργίας; 483–375 BC) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Along with Protagoras, he forms the first generation of Sophists. Several ...

at a young age and helped him develop exceptional rhetoric. As he grew older and his understanding of education developed, Isocrates disregarded the importance of the arts and sciences, believing rhetoric was the key to virtue. Education's purpose was to produce civic efficiency and political leadership and therefore, the ability to speak well and persuade became the cornerstone of his educational theory. However, at the time there was no definite curriculum for Higher Education, with only the existence of the sophists

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ...

who were constantly traveling. In response, Isocrates founded his school of Rhetoric around 393 BCE. The school was in contrast to Plato's Academy (c. 387 BCE) which was largely based on science, philosophy, and dialectic.

=Plato (428–348 BC)

=

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

was a philosopher in classical Athens who studied under Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, ultimately becoming one of his most famed students. Following Socrates' execution, Plato left Athens in anger, rejecting politics as a career and traveling to Italy and Sicily. He returned ten years later to establish his school, the Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

(c. 387 BCE) – named after the Greek hero Akademos

Academus or Akademos (; Ancient Greek: Ἀκάδημος), also Hekademos or Hecademus (Ἑκάδημος) was an Attic hero in Greek mythology. Academus, the place lies on the Cephissus, six stadia from Athens.

Place origins

Academus, the s ...

. Plato perceived education as a method to produce citizens who could operate as members of the civic community in Athens. In one sense, Plato believed Athenians could obtain education through the experiences of being a community member, but he also understood the importance of deliberate training, or Higher Education, in the development of civic virtue

Civic virtue is the harvesting of habits important for the success of a society. Closely linked to the concept of citizenship, civic virtue is often conceived as the dedication of citizens to the common welfare of each other even at the cost of ...

. Thus, his reasoning behind founding the Academy – what is often credited as the first University.

It is at this school where Plato discussed much of his educational program, which he outlined in his best-known work – the '' Republic.'' In his writing, Plato describes the rigorous process one must go through in order to attain true virtue and understand reality for what it actually is. The education required of such achievement, according to Plato, included an elementary education in music, poetry, and physical training, two to three years of mandatory military training, ten years of mathematical science, five years of dialectic training, and fifteen years of practical political training. The few individuals equipped to reach such a level would become philosopher-kings, the leaders of Plato's ideal city.

= Aristotle (384–322 BC)

=

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

was a classical Greek philosopher. While born in Stagira, Chalkidice, Aristotle joined Plato's Academy in Athens during his late teenage years and remained there until the age of thirty-seven, withdrawing following Plato's death. His departure from the Academy also signalled his departure from Athens. Aristotle left to join Hermeias, a former student at the Academy, who had become the ruler of Atarneus

Atarneus (; grc, Ἀταρνεύς), also known as Atarna (Ἄταρνα) and Atarneites (Ἀταρνείτης), was an ancient Greek city in the region of Aeolis, Asia Minor. It lies on the mainland opposite the island of Lesbos. It was on the ...

and Assos in the north-western coast of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

(present-day Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

). He remained in Anatolia until, in 342 BCE, he received an invitation from King Philip of Macedon to become the educator of his thirteen-year-old son Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

. Aristotle accepted the invitation and moved to Pella

Pella ( el, Πέλλα) is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It is best-known for serving as the capital city of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon, and was the birthplace of Alexander the Great.

On site of the ancient cit ...

to begin his work with the boy who would soon become known as Alexander the Great. When Aristotle moved back to Athens in 352 BCE, Alexander helped finance Aristotle's school – the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the ...

. A significant part of the Lyceum was research. The school had a systematic approach to the collection of information. Aristotle believed dialectical relationships among students performing research could impede the pursuit of truth. Thus, much of the school's focus was on research done empirically.

Spartan system

The Spartan society desired that all male citizens become successful soldiers with the stamina and skills to defend their polis as members of a Spartan phalanx. It was a rumored byPlutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

, a Greek historian, that Sparta killed weak children.Ed. Sienkewicz, "Education and Training," ''Ancient Greece'' (New Jersey: Salem Press, Inc. 2007), 344. After examination, the council would either rule that the child was fit to live or would reject the child sentencing him to death by abandonment and exposure.

Agoge

Military dominance was of extreme importance to the Spartans of Ancient Greece. In response, the Spartans structured their educational system as an extreme form of military boot camp, which they referred to as ''agoge

The ( grc-gre, ἀγωγή in Attic Greek, or , in Doric Greek) was the rigorous education and training program mandated for all male Spartan citizens, with the exception of the firstborn son in the ruling houses, Eurypontid and Agiad. The ...

''.Adkins and Adkins, ''Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece'' (New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2005), 104. The pursuit of intellectual knowledge was seen as trivial, and thus academic learning, such as reading and writing, was kept to a minimum. A Spartan boy's life was devoted almost entirely to his school, and that school had but one purpose: to produce an almost indestructible Spartan ''phalanx''. Formal education for a Spartan male began at about the age of seven when the state removed the boy from the custody of his parents and sent him to live in a barracks with many other boys his age. For all intents and purposes, the barracks was his new home, and the other males living in the barracks his family. For the next five years, until about the age of twelve, the boys would eat, sleep and train within their barracks unit and receive instruction from an adult male citizen who had completed all of his military training and experienced battle.

The instructor stressed discipline and exercise and saw to it that his students received little food and minimal clothing in an effort to force the boys to learn how to forage, steal and endure extreme hunger, all of which would be necessary skills in the course of a war. Those boys who survived the first stage of training entered into a secondary stage in which punishments became harsher and physical training and participation in sports almost non-stop in order to build up strength and endurance. During this stage, which lasted until the males were about eighteen years old, fighting within the unit was encouraged, mock battles were performed, acts of courage praised, and signs of cowardice and disobedience severely punished.Adkins and Adkins, ''Handbook'', 105

During the mock battles, the young men were formed into ''phalanxes'' to learn to maneuver as if they were one entity and not a group of individuals. To be more efficient and effective during maneuvers, students were also trained in dancing and music, because this would enhance their ability to move gracefully as a unit. Toward the end of this phase of the ''agoge'', the trainees were expected to hunt down and kill a Helot

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

, a Greek slave. If caught, the student would be convicted and disciplined-not for committing murder, but for his inability to complete the murder without being discovered.

Ephebe

The students would graduate from the ''agoge'' at the age of eighteen and receive the title of '' ephebes''. Upon becoming an ''ephebe'', the male would pledge strict and complete allegiance to Sparta and would join a private organization to continue training in which he would compete in gymnastics, hunting and performance with planned battles using real weapons. After two years, at the age of twenty, this training was finished and the now-grown men were officially regarded as Spartan soldiers.Education of Spartan women

Spartan women, unlike their Athenian counterparts, received a formal education that was supervised and controlled by the state. Much of the public schooling received by the Spartan women revolved around physical education. Until about the age of eighteen women were taught to run, wrestle, throw a discus, and also to throw javelins. The skills of the young women were tested regularly in competitions such as the annual footrace at the Heraea of Elis, In addition to physical education, the young girls also were taught to sing, dance, and play instruments often by traveling poets such asAlcman

Alcman (; grc-gre, Ἀλκμάν ''Alkmán''; fl. 7th century BC) was an Ancient Greek choral lyric poet from Sparta. He is the earliest representative of the Alexandrian canon of the Nine Lyric Poets.

Biography

Alcman's dates are u ...

or by the elderly women in the polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

. The Spartan educational system for females was very strict because its purpose was to train future mothers of soldiers in order to maintain the strength of Sparta's phalanxes, which were essential to Spartan defense and culture.Pomeroy, ''Spartan Women'', 4.

Other Greek educators

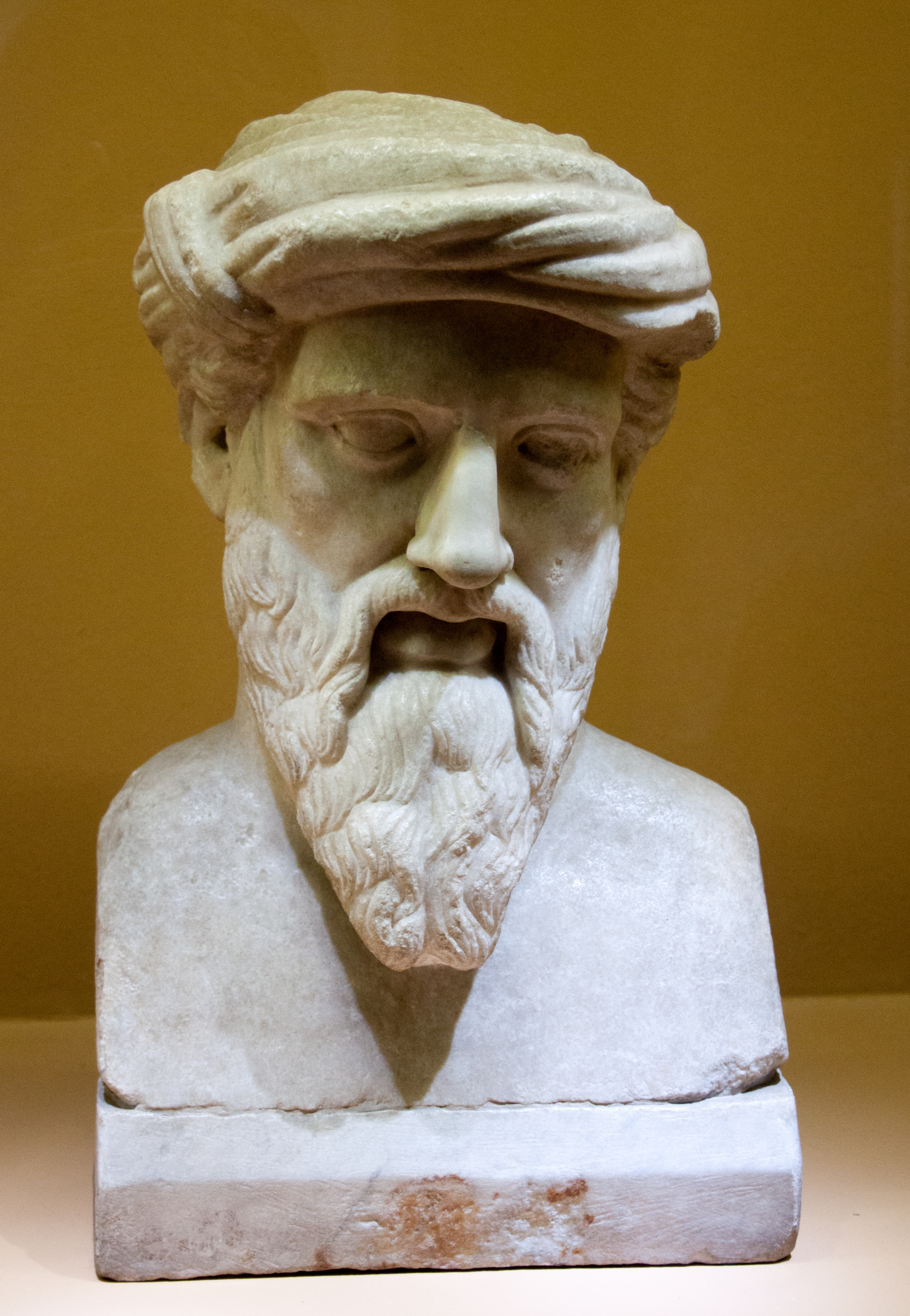

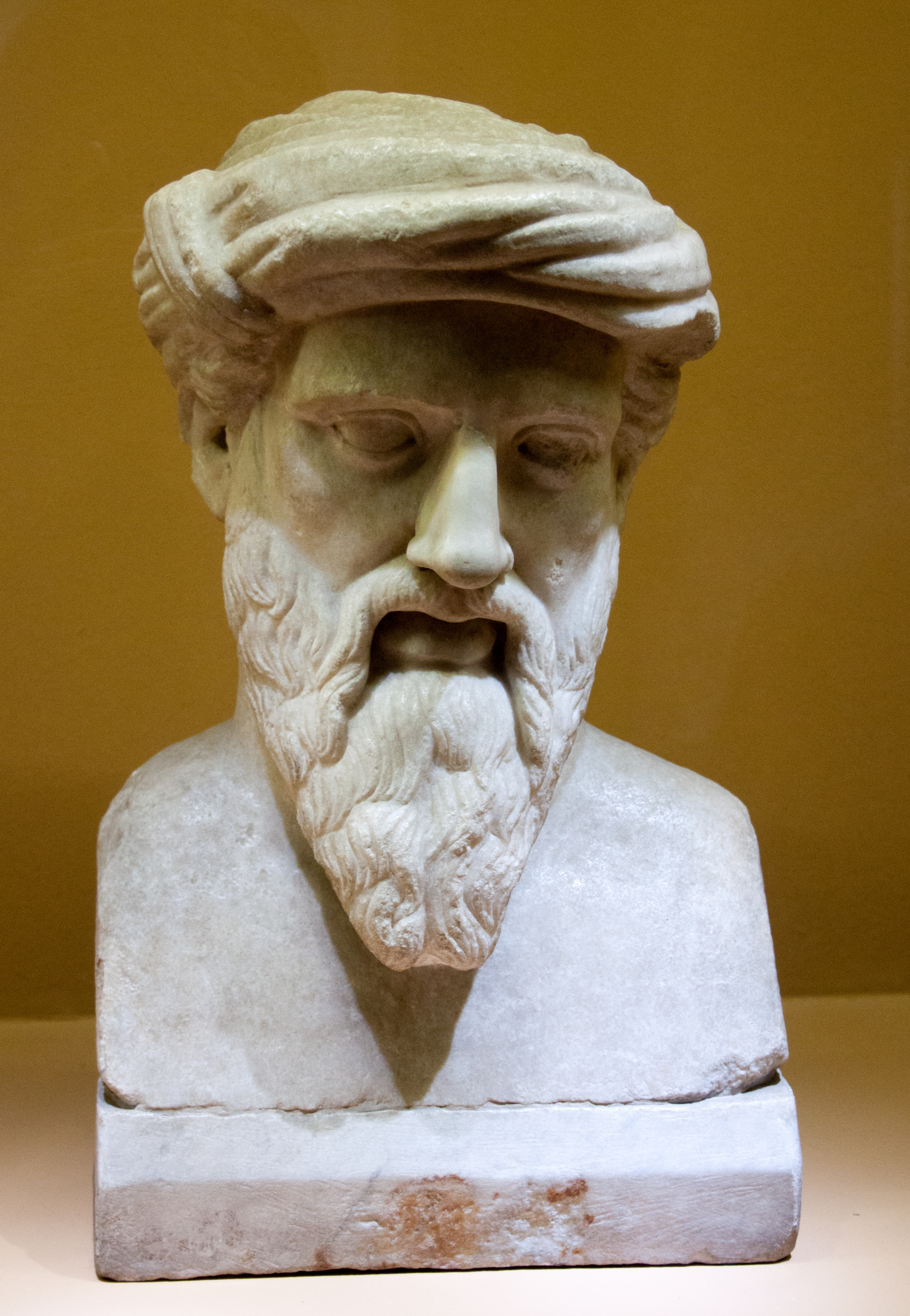

Pythagoras (570–490 BCE)

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politic ...

was one of many Greek philosophers. He lived his life on the island Samos and is known for his contributions to mathematics. Pythagoras taught philosophy of life, religion, and mathematics in his own school in Kroton, which was a Greek colony. Pythagoras' school is linked to the Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry between the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposit ...

, which states that the square of the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. The students of Pythagoras were known as Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

.

Pythagoreans

Pythagoreans followed a very specific way of life. They were famous for friendship, unselfishness, and honesty. The Pythagoreans also believed in a life after the current which drove them to be people who have no attachment to personal possessions everything was communal; they were also vegetarians. The people in a Pythagorean society were known as ''mathematikoi'' (μαθηματικοί, Greek for "learners").Teachings

There are two forms that Pythagoras taught,Exoteric

Exoteric refers to knowledge that is outside and independent from a person's experience and can be ascertained by anyone (related to common sense).

The word is derived from the comparative form of Greek ἔξω ''eksô'', "from, out of, outside". ...

and Esoteric. Exoteric was the teaching of generally accepted ideas. These courses lasted three years for ''mathematikoi''. Esoteric was teachings of deeper meaning. These teachings did not have a time limit. They were subject to when Pythagoras thought the student was ready. In Esoteric, students would learn the philosophy of inner meanings. The focus of Pythagoras in his Exoteric teachings were ethical teachings. Here, he taught the idea of the dependence of opposites in the world; the dynamics behind the balance of opposites.

Along with the more famous achievements, Pythagoreans were taught various mathematical ideas. They were taught the following: Pythagorean theorem, irrational numbers, five specific regular polygons, and that the earth was a sphere in the centre of the universe. Many people believed that the mathematical ideas that Pythagoras brought to the table allowed reality to be understood. Whether reality was seen as ordered or if it just had a geometrical structure. Even though Pythagoras has many contributions to mathematics, his most known theory is that things themselves are numbers. Pythagoras has a unique teaching style. He never appeared face to face to his students in the Exoteric courses. Pythagoras would set a current and face the other direction to address them. The students upon passing their education become initiated to be disciples. Pythagoras was much more intimate with the initiated and would speak to them in person. The specialty taught by Pythagoras was his theoretical teachings. In the society of Crotona, Pythagoras was known as the master of all science and brotherhood.

Rules of the school

Unlike other education systems of the time, men and women were allowed to be Pythagorean. The Pythagorean students had rules to follow such as: abstaining from beans, not picking up items that have fallen, not touching white chickens, could not stir the fire with iron, and not looking in a mirror that was beside a light.Mathematics and music

Some of Pythagoras's applications of mathematics can be seen in his musical relationship to mathematics. The idea of proportions and ratios. Pythagoreans are known for formulating numerical concords and harmony. They put together sounds by the plucking of a string. The fact that the musician meant to pluck it at a mathematically expressible point. However, if the mathematical proportion between the points on the string were to be broken, the sound would become unsettled.School's dictum

The Pythagorean school had adictum

In general usage, a dictum ( in Latin; plural dicta) is an authoritative or dogmatic statement. In some contexts, such as legal writing and church cantata librettos, ''dictum'' can have a specific meaning.

Legal writing

In United States legal te ...

that said ''All is number''. This means that everything in the world had a number that described them. For instance, number 6 is the number that relates to creation, number 5 is the number that relates to marriage, number 4 is the number that relates to justice, number 3 is the number that relates to harmony, number 2 is the number that relates to opinion, and number 1 is the number that relates to reason.

Pythagorean Society was very secretive, the education society was based around the idea of living in peace and harmony, but secretly. Due to the education and society being so secretive, not much is known about the Pythagorean people.

See also

*Agoge

The ( grc-gre, ἀγωγή in Attic Greek, or , in Doric Greek) was the rigorous education and training program mandated for all male Spartan citizens, with the exception of the firstborn son in the ruling houses, Eurypontid and Agiad. The ...

* Scholarch

A scholarch ( grc, σχολάρχης, ''scholarchēs'') was the head of a school in ancient Greece. The term is especially remembered for its use to mean the heads of schools of philosophy, such as the Platonic Academy in ancient Athens. Its fir ...

* Gymnasiarch

Gymnasiarch ( la, gymnasiarchus, from el, γυμνασίαρχος, ''gymnasiarchos''), which derives from Greek γυμνάσιον (''gymnasion'', gymnasium) + ἄρχειν, ''archein'', to lead, was the name of an official of ancient Greece wh ...

* Platonic Academy

The Academy (Ancient Greek: Ἀκαδημία) was founded by Plato in c. 387 BC in Classical Athens, Athens. Aristotle studied there for twenty years (367–347 BC) before founding his own school, the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum. The Academy ...

* Gymnasium (ancient Greece)

The gymnasium ( grc-gre, γυμνάσιον, gymnásion) in Ancient Greece functioned as a training facility for competitors in public games. It was also a place for socializing and engaging in intellectual pursuits. The name comes from the An ...

Notes

References

*Lynch, John P. (1972). Aristotle's School: A Study of a Greek Educational Institution. Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 33. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 36. *Sienkewicz, Joseph, ed. (2007). "Education and Training". Ancient Greece. New Jersey: Salem Press, Inc. p. 344. *Plutarch (1927). "The Training of Children". Moralia. Loeb Classical Library. p. 7. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 37. *Beck, Frederick A.G. (1964). Greek Education, 450–350 B.C. London: Methuen & CO LTD. pp. 201–202. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 38. *Lodge, R.C. (1970). Plato's Theory of Education. New York: Russell & Russell. p. 11. *Aristophanes, Lysistrata and Other Plays (London: Penguin Classics, 2002), 65. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 38. *Plutarch The Training of Children, c. 110 CE (Ancient History Sourcebook), 5–6. *Downey, "Ancient Education," The Classical Journal 52, no.8 (May 1980): 340. *Lodge. Plato's Theory of Education. p. 304. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 33. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 39. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 38. *O’pry, Kay (2012). "Social and Political Roles of Women in Athens and Sparta". Saber and Scroll. 1: 9. *Plutarch (1960). The Rise and Fall of Athens: Nine Greek Lives. London: Penguin Classics. pp. 168–9. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 253. *Matsen, Patricia; Rollinson, Philip; Sousa, Marion (1990). Readings from Classical Rhetoric. Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 43. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 255. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 257. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 293. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 227. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 200. *Beck. Greek Education. p. 240. *Lodge. Plato's Theory of Education. p. 303. *Plato (2013). Republic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 186. *Plato. Republic. p. 188. *Anagnostopoulos, Georgios, ed. (2013). "First Athenian Period". A Companion to Aristotle. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. *Anagnostopoulos (ed.). Companion to Aristotle. p. 8. *Anagnostopoulos (ed.). Companion to Aristotle. p. 9. *Lynch. Aristotle's School. p. 87.Primary sources (ancient Greek)

* See original text iPerseus program

* Lycurgus, Contra Leocratem. * * . See original text i

* * . See original text i

Secondary sources

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Education In Ancient Greece Education in ancient Greece, History of academia