Easter Islands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of

Estimated dates of initial settlement of Easter Island have ranged from 300 to 1200 CE, though the current best estimate for colonization is in the . Easter Island colonization likely coincided with the arrival of the first settlers in Hawaii. Rectifications in

Estimated dates of initial settlement of Easter Island have ranged from 300 to 1200 CE, though the current best estimate for colonization is in the . Easter Island colonization likely coincided with the arrival of the first settlers in Hawaii. Rectifications in  According to oral traditions recorded by

According to oral traditions recorded by  As the island became overpopulated and resources diminished, warriors known as ''matatoa'' gained more power and the Ancestor Cult ended, making way for the Bird Man Cult. Beverly Haun wrote, "The concept of mana (power) invested in hereditary leaders was recast into the person of the birdman, apparently beginning circa 1540, and coinciding with the final vestiges of the moai period." This cult maintained that, although the ancestors still provided for their descendants, the medium through which the living could contact the dead was no longer statues but human beings chosen through a competition. The god responsible for creating humans,

As the island became overpopulated and resources diminished, warriors known as ''matatoa'' gained more power and the Ancestor Cult ended, making way for the Bird Man Cult. Beverly Haun wrote, "The concept of mana (power) invested in hereditary leaders was recast into the person of the birdman, apparently beginning circa 1540, and coinciding with the final vestiges of the moai period." This cult maintained that, although the ancestors still provided for their descendants, the medium through which the living could contact the dead was no longer statues but human beings chosen through a competition. The god responsible for creating humans,

The first recorded European contact with the island was on 5 April 1722,

The first recorded European contact with the island was on 5 April 1722,  On 10 April 1786, French Admiral

On 10 April 1786, French Admiral

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapa Nui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapa Nui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the

Fishers of Rapa Nui have shown their concern of

Fishers of Rapa Nui have shown their concern of

Starting in August 2010, members of the indigenous Hitorangi clan occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa. The occupiers allege that the hotel was bought from the Pinochet government, in violation of a Chilean agreement with the indigenous Rapa Nui, in the 1990s. The occupiers say their ancestors had been cheated into giving up the land. According to a

Starting in August 2010, members of the indigenous Hitorangi clan occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa. The occupiers allege that the hotel was bought from the Pinochet government, in violation of a Chilean agreement with the indigenous Rapa Nui, in the 1990s. The occupiers say their ancestors had been cheated into giving up the land. According to a

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. Its closest inhabited neighbour is

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. Its closest inhabited neighbour is

Easter Island is a

Easter Island is a

File:Easter Island ESA419941 (cropped, lightened).jpg, Satellite view of Easter Island 2019. The Poike peninsula is on the right.

File:RAPA NUI.JPG, Digital recreation of its ancient landscape, with tropical forest and palm trees

File:Easter Island 3.jpg, Hanga Roa seen from Terevaka, the highest point of the island

File:Easter Island 13.jpg, View of

The immunosuppressant drug sirolimus was first discovered in the bacterium ''Streptomyces hygroscopicus'' in a

File:Kneeled moai Easter Island.jpg, Rano Raraku#Tukuturi, Tukuturi, an unusual bearded kneeling moai

File:Ahu-Tongariki-2013.jpg, All fifteen standing moai at Ahu Tongariki, excavated and restored in the 1990s

File:Ahu-Akivi-1.JPG, Ahu Akivi, one of the few inland ahu, with the only moai facing the ocean

''Ahu'' are stone platforms. Varying greatly in layout, many were reworked during or after Moai#1722–1868 Toppling of the Moai, the ''huri mo'ai'' or ''statue-toppling'' era; many became ossuary, ossuaries, one was dynamited open, and Ahu Tongariki was swept inland by a tsunami. Of the 313 known ahu, 125 carried moaiusually just one, probably because of the shortness of the moai period and transportation difficulties. Ahu Tongariki, from Rano Raraku, had the most and tallest moai, 15 in total. Other notable ahu with moai are Ahu Akivi, restored in 1960 by William Mulloy, Nau Nau at Anakena and Tahai. Some moai may have been made from wood and were lost.

The classic elements of ahu design are:

* A retaining rear wall several feet high, usually facing the sea

* A front wall made of rectangular basalt slabs called ''paenga''

* A fascia made of red scoria that went over the front wall (platforms built after 1300)

* A sloping ramp in the inland part of the platform, extending outward like wings

* A pavement of even-sized, round water-worn stones called ''poro''

* An alignment of stones before the ramp

* A paved plaza before the ahu. This was called ''marae''

* Inside the ahu was a fill of rubble.

On top of many ahu would have been:

* Moai on squarish "pedestals" looking inland, the ramp with the poro before them.

* Pukao or Hau Hiti Rau on the moai heads (platforms built after 1300).

* When a ceremony took place, "eyes" were placed on the statues. The whites of the eyes were made of coral, the iris was made of obsidian or red scoria.

Ahu evolved from the traditional Polynesian ''

''Ahu'' are stone platforms. Varying greatly in layout, many were reworked during or after Moai#1722–1868 Toppling of the Moai, the ''huri mo'ai'' or ''statue-toppling'' era; many became ossuary, ossuaries, one was dynamited open, and Ahu Tongariki was swept inland by a tsunami. Of the 313 known ahu, 125 carried moaiusually just one, probably because of the shortness of the moai period and transportation difficulties. Ahu Tongariki, from Rano Raraku, had the most and tallest moai, 15 in total. Other notable ahu with moai are Ahu Akivi, restored in 1960 by William Mulloy, Nau Nau at Anakena and Tahai. Some moai may have been made from wood and were lost.

The classic elements of ahu design are:

* A retaining rear wall several feet high, usually facing the sea

* A front wall made of rectangular basalt slabs called ''paenga''

* A fascia made of red scoria that went over the front wall (platforms built after 1300)

* A sloping ramp in the inland part of the platform, extending outward like wings

* A pavement of even-sized, round water-worn stones called ''poro''

* An alignment of stones before the ramp

* A paved plaza before the ahu. This was called ''marae''

* Inside the ahu was a fill of rubble.

On top of many ahu would have been:

* Moai on squarish "pedestals" looking inland, the ramp with the poro before them.

* Pukao or Hau Hiti Rau on the moai heads (platforms built after 1300).

* When a ceremony took place, "eyes" were placed on the statues. The whites of the eyes were made of coral, the iris was made of obsidian or red scoria.

Ahu evolved from the traditional Polynesian ''

File:Makemake.jpeg,

* Reimiro, a gorget or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips. The same design appears on the flag of Rapa Nui. Two Rei Miru at the British Museum are inscribed with Rongorongo.

* Moko Miro, a man with a lizard head. The Moko Miro was used as a club because of the legs, which formed a handle shape. If it wasn't held by hand, dancers wore it around their necks during feasts. The Moko Miro would also be placed at the doorway to protect the household from harm. It would be hanging from the roof or set in the ground. The original form had eyes made from white shells, and the pupils were made of obsidian.

* Moai kavakava are male carvings and the Moai Paepae are female carvings.Encyclopædia Britannica Online

* Reimiro, a gorget or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips. The same design appears on the flag of Rapa Nui. Two Rei Miru at the British Museum are inscribed with Rongorongo.

* Moko Miro, a man with a lizard head. The Moko Miro was used as a club because of the legs, which formed a handle shape. If it wasn't held by hand, dancers wore it around their necks during feasts. The Moko Miro would also be placed at the doorway to protect the household from harm. It would be hanging from the roof or set in the ground. The original form had eyes made from white shells, and the pupils were made of obsidian.

* Moai kavakava are male carvings and the Moai Paepae are female carvings.Encyclopædia Britannica Online

"Moai Figure"

. These grotesque and highly detailed human figures carved from Toromiro pine, represent ancestors. Sometimes these statues were used for fertility rites. Usually, they are used for harvest celebrations; "the first picking of fruits was heaped around them as offerings". When the statues were not used, they would be wrapped in bark cloth and kept at home. There were a few times that are reported when the islanders would pick up the figures like dolls and dance with them. The earlier figures are rare and generally depict a male figure with an emaciated body and a goatee. The figures' ribs and vertebrae are exposed and many examples show carved glyphs on various parts of the body but more specifically, on the top of the head. The female figures, rarer than the males, depict the body as flat and often with the female's hand lying across the body. The figures, although some were quite large, were worn as ornamental pieces around a tribesman's neck. The more figures worn, the more important the man. The figures have a shiny patina developed from constant handling and contact with human skin. * Ao, a large dancing paddle

File:HangaroaAlcaldía.jpg, Hanga Roa town hall

File:TAMURE.png, Polynesian culture, Polynesian dancing with feather costumes is on the tourist itinerary.

File:EasterIslandsFishingBoats.jpg, Fishing boats

File:Hanga Roa Catholic Church exterior 1.JPG, Front view of the Catholic Church, Hanga Roa

File:Hanga Roa Catholic Church exterior 2.JPG, Catholic Church, Hanga Roa

File:Hanga Roa Catholic Church interior.JPG, Interior view of the Catholic Church in Hanga Roa

in Internet Archive

* *

Terevaka Archaeological Outreach (TAO)

– Non-profit Educational Outreach & Cultural Awareness on Easter Island

Easter Island – The Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui

– Bradshaw Foundation / Dr Georgia Lee

Chile Cultural Society – Easter Island

Rapa Nui Digital Media Archive

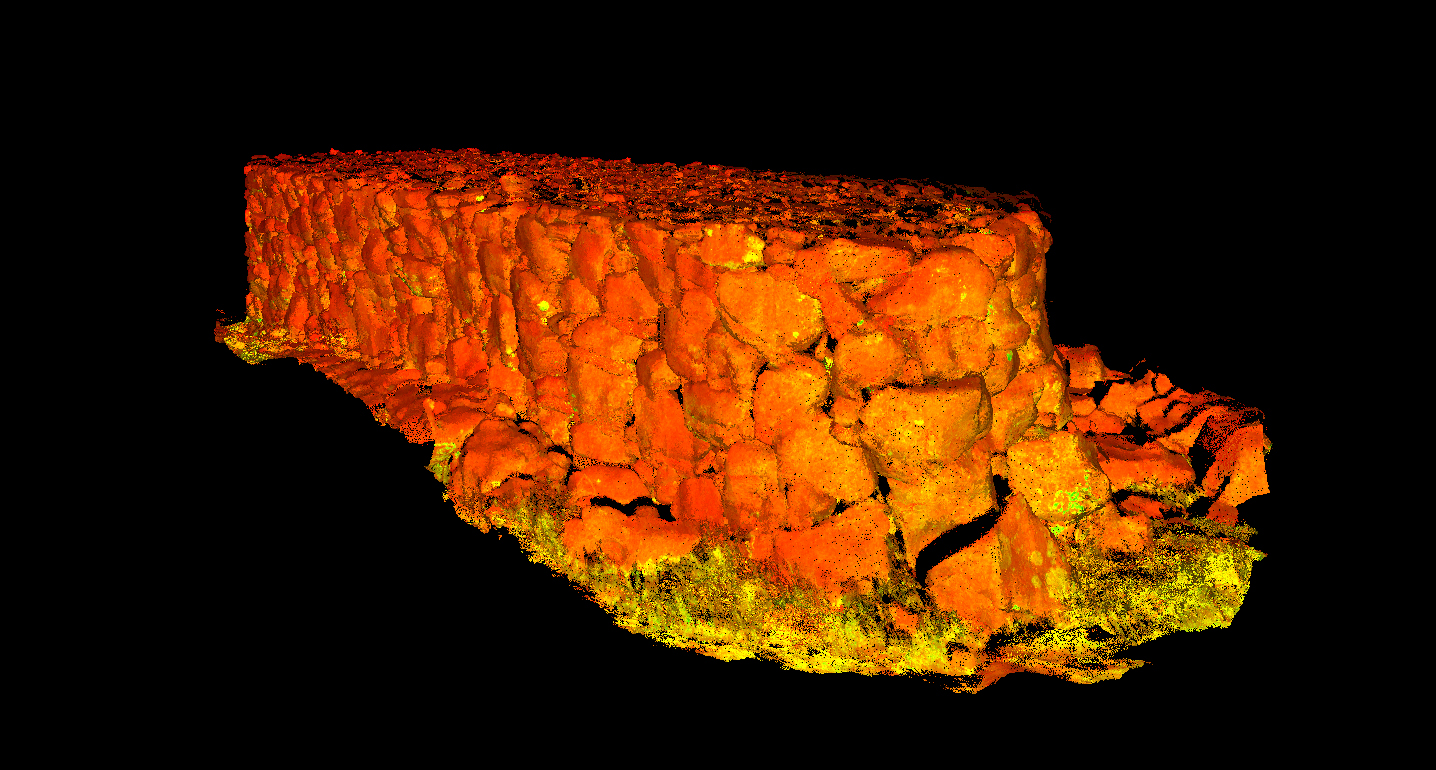

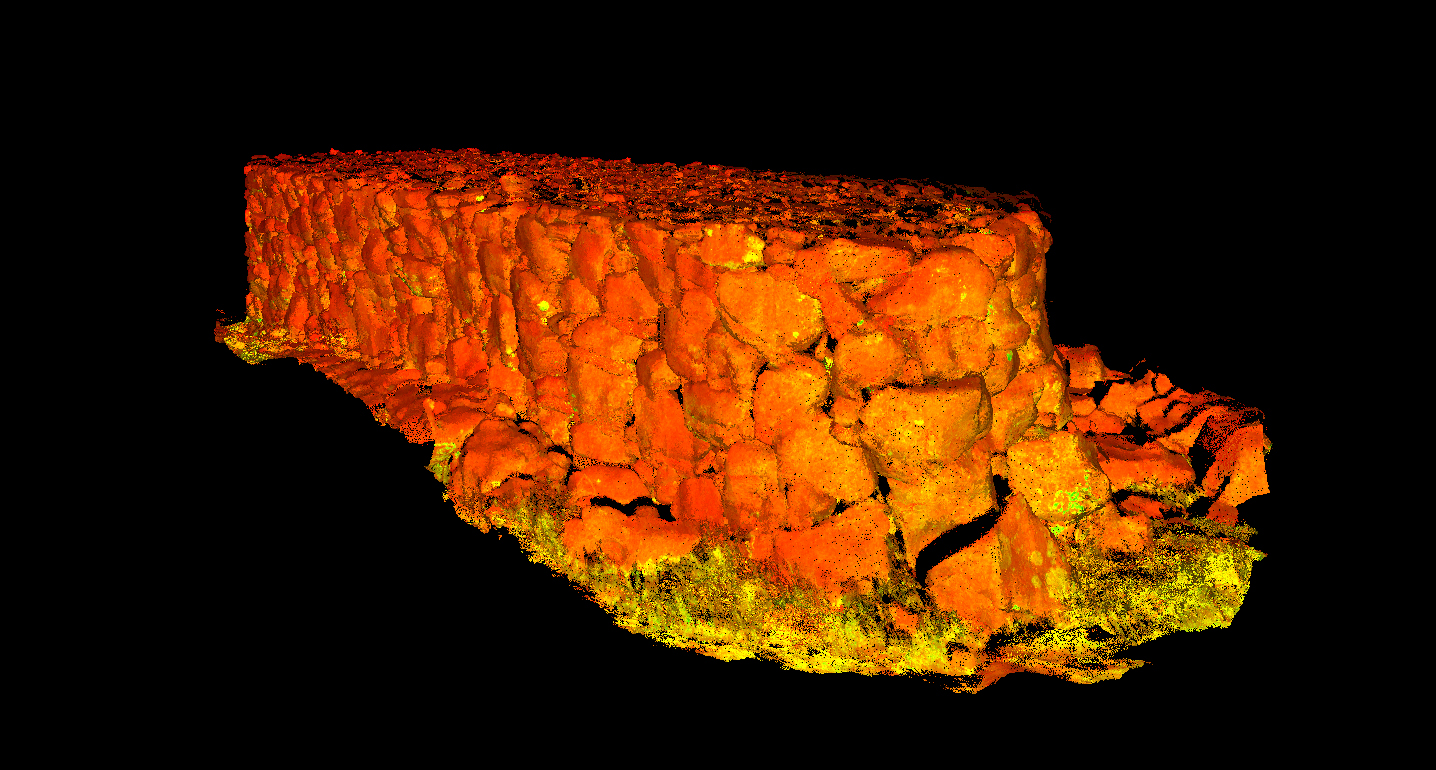

– Creative Commons – licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas, focused in the area around Rano Raraku and Ahu Te Pito Kura with data from an Autodesk/CyArk research partnership

Mystery of Easter Island

– PBS Nova program

Current Archaeology's comprehensive description of island and discussion of dating controversies

Books and Texts about Easter Island from the Internet Archive

* {{Authority control Easter Island, Archaeological sites in Chile Archaeological sites in Oceania Ecoregions of Chile Geography of Polynesia Pacific islands of Chile Islands of Oceania Islands of Valparaíso Region Oceanian ecoregions Volcanic islands Eastern Indo-Pacific Marine ecoregions

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

in the southeastern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle

The Polynesian Triangle is a region of the Pacific Ocean with three island groups at its corners: Hawai‘i, Easter Island (''Rapa Nui'') and New Zealand (Aotearoa). It is often used as a simple way to define Polynesia.

Outside the triangle, th ...

in Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a region, geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern Hemisphere, Eastern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of ...

. The island is most famous for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, called ''moai

Moai or moʻai ( ; es, moái; rap, moʻai, , statue) are monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui people on Easter Island, Rapa Nui in eastern Polynesia between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main mo ...

'', which were created by the early Rapa Nui people

The Rapa Nui (Rapa Nui: , Spanish: ) are the Polynesian peoples indigenous to Easter Island. The easternmost Polynesian culture, the descendants of the original people of Easter Island make up about 60% of the current Easter Island population and ...

. In 1995, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

named Easter Island a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

, with much of the island protected within Rapa Nui National Park

Rapa Nui National Park ( es, Parque nacional Rapa Nui) is a national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site located on Easter Island, Chile. Rapa Nui is the Polynesian name of Easter Island; its Spanish name is Isla de Pascua. The island is located ...

.

Experts disagree on when the island's Polynesian inhabitants first reached the island. While many in the research community cited evidence that they arrived around the year 800, there is compelling evidence presented in a 2007 study that places their arrival closer to 1200. The inhabitants created a thriving and industrious culture, as evidenced by the island's numerous enormous stone ''moai'' and other artifacts. However, land clearing for cultivation and the introduction of the Polynesian rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), known to the Māori as ''kiore'', is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. The Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asia, a ...

led to gradual deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated d ...

. By the time of European arrival in 1722, the island's population was estimated to be 2,000 to 3,000. European diseases, Peruvian slave raiding

Slave raiding is a military raid for the purpose of capturing people and bringing them from the raid area to serve as slaves. Once seen as a normal part of warfare, it is nowadays widely considered a crime. Slave raiding has occurred since ant ...

expeditions in the 1860s, and emigration to other islands such as Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

further depleted the population, reducing it to a low of 111 native inhabitants in 1877.

Chile annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

Easter Island in 1888. In 1966, the Rapa Nui were granted Chilean citizenship. In 2007 the island gained the constitutional status of "special territory" ( es, territorio especial). Administratively, it belongs to the Valparaíso Region

The Valparaíso Region ( es, Región de Valparaíso, links=no, ) is one of Chile's 16 first order administrative divisions.Valparaíso Region, 2006 With the country's second-highest population of 1,790,219 , and fourth-smallest area of , ...

, constituting a single commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

(Isla de Pascua

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly ...

) of the Province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

of Isla de Pascua

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly ...

. The 2017 Chilean census registered 7,750 people on the island, of whom 3,512 (45%) considered themselves Rapa Nui.

Easter Island is one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world. The nearest inhabited land (around 50 residents in 2013) is Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

, away; the nearest town with a population over 500 is Rikitea

Rikitea is a small town on Mangareva, which is part of the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia. A majority of the islanders live in Rikitea. The island was a protectorate of France in 1871 and was annexed in 1881.

History

The town's history dates ...

, on the island of Mangareva

Mangareva is the central and largest island of the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia. It is surrounded by smaller islands: Taravai in the southwest, Aukena and Akamaru in the southeast, and islands in the north. Mangareva has a permanent pop ...

, away; the nearest continental point lies in central Chile, away.

Etymology

The name "Easter Island" was given by the island's first recorded European visitor, the Dutch explorerJacob Roggeveen

Jacob Roggeveen (1 February 1659 – 31 January 1729) was a Dutch explorer who was sent to find Terra Australis and Davis Land, but instead found Easter Island (called so because he landed there on Easter Sunday). Jacob Roggeveen also found Bora ...

, who encountered it on Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

(5 April) in 1722, while searching for "Davis Land

Davis Land is the name of a phantom island that was believed to be located in the Pacific Ocean, near South America. It is named for the pirate Edward Davis, who supposedly sighted it in 1687. Never found again, it was also believed by William D ...

". Roggeveen named it ''Paasch-Eyland'' (18th-century Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

for "Easter Island")."An English translation of the originally Dutch journal by Jacob Roggeveen, with additional significant information from the log by Cornelis Bouwman", was published in: Andrew Sharp (ed.), ''The Journal of Jacob Roggeveen'' (Oxford 1970). The island's official Spanish name, ''Isla de Pascua'', also means "Easter Island".

The current Polynesian name of the island, ''Rapa Nui'' ("Big Rapa"), was coined after the slave raids of the early 1860s, and refers to the island's topographic resemblance to the island of Rapa in the Bass Islands

The Bass Islands are three American islands in the western half of Lake Erie. They are north of Sandusky, Ohio, and south of Pelee Island, Ontario. South Bass Island () is the largest of the islands, followed closely by North Bass Island () a ...

of the Austral Islands

The Austral Islands (french: Îles Australes, officially ''Archipel des Australes;'' ty, Tuha'a Pae) are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of the French Republic in the South Pacific. Geographically, ...

group. However, Norwegian ethnographer

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl KStJ (; 6 October 1914 – 18 April 2002) was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in zoology, botany and geography.

Heyerdahl is notable for his ''Kon-Tiki'' expedition in 1947, in which he sailed 8,000&nb ...

argued that ''Rapa'' was the original name of Easter Island and that ''Rapa Iti'' was named by refugees from there.

The phrase ''Te pito o te henua'' has been said to be the original name of the island since French ethnologist Alphonse Pinart

Alphonse Louis Pinart (26 February 1852 — 13 February 1911) was a French scholar, linguist, ethnologist and collector, specialist on the American continent. He studied the civilizations of the New World in the manner of the pioneers of the time ...

gave it the romantic translation "the Navel of the World" in his ''Voyage à l'Île de Pâques'', published in 1877. William Churchill (1912) inquired about the phrase and was told that there were three ''te pito o te henua'', these being the three capes (land's ends) of the island. The phrase appears to have been used in the same sense as the designation of "Land's End" at the tip of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

. He was unable to elicit a Polynesian name for the island and concluded that there may not have been one.

According to Barthel (1974), oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

has it that the island was first named ''Te pito o te kainga a Hau Maka'', "The little piece of land of Hau Maka". However, there are two words pronounced ''pito'' in Rapa Nui, one meaning 'end' and one 'navel', and the phrase can thus also mean "The Navel of the World". Another name, ''Mata ki te rangi'', means "Eyes looking to the sky".

Islanders are referred to in Spanish as ''pascuense''; however it is common to refer to members of the indigenous community as ''Rapa Nui''.

Felipe González de Ahedo

Felipe González de Ahedo, also spelled Phelipe González y Haedo (13 May 1714 in Santoña, Cantabria – 26 October 1802), was a Spanish navigator and cartographer known for annexing Easter Island in 1770.

González de Ahedo commanded two ...

named it ''Isla de San Carlos'' (" Saint Charles' Island", the patron saint of Charles III of Spain

it, Carlo Sebastiano di Borbone e Farnese

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Elisabeth Farnese

, birth_date = 20 January 1716

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain

, death_d ...

) or ''Isla de David'' (probably the phantom island of Davis Land

Davis Land is the name of a phantom island that was believed to be located in the Pacific Ocean, near South America. It is named for the pirate Edward Davis, who supposedly sighted it in 1687. Never found again, it was also believed by William D ...

; sometimes translated as "Davis's Island") in 1770. In Wikimedia Commons.

History

Introduction

Oral tradition states the island was first settled by a two-canoe expedition, originating from Marae Renga (or Marae Toe Hau – otherwise known asCook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

), and led by the chief Hotu Matu'a and his captain Tu'u ko Iho. The island was first scouted after Haumaka dreamed of such a far-off country; Hotu deemed it a worthwhile place to flee from a neighboring chief, one to whom he had already lost three battles. At their time of arrival, the island had one lone settler, Nga Tavake 'a Te Rona. After a brief stay at Anakena

Anakena is a white coral sand beach in Rapa Nui National Park on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. Anakena has two ahus; Ahu-Ature has a single moai and Ahu Nao-Nao has seven, two of which have deteriorated. It als ...

, the colonists settled in different parts of the island. Hotu's heir, Tu'u ma Heke, was born on the island. Tu'u ko Iho is viewed as the leader who brought the statues and caused them to walk.

The Easter Islanders are considered to be South-East Polynesians. Similar sacred zones with statuary (''marae

A ' (in New Zealand Māori, Cook Islands Māori, Tahitian), ' (in Tongan), ' (in Marquesan) or ' (in Samoan) is a communal or sacred place that serves religious and social purposes in Polynesian societies. In all these languages, the term a ...

'' and ''ahu'') in East Polynesia demonstrates homology with most of Eastern Polynesia. At contact, populations were about 3,000–4,000.

By the 15th century, two confederations, ''hanau'', of social groupings, ''mata'', existed, based on lineage. The western and northern portion of the island belonged to the Tu'u, which included the royal Miru, with the royal center at Anakena, though Tahai and Te Peu served as earlier capitals. The eastern portion of the island belonged to the 'Otu 'Itu. Shortly after the Dutch visit, from 1724 until 1750, the 'Otu 'Itu fought the Tu'u for control of the island. This fighting continued until the 1860s. Famine followed the burning of huts and the destruction of fields. Social control vanished as the ordered way of life gave way to lawlessness and predatory bands as the warrior class took over. Homelessness prevailed, with many living underground. After the Spanish visit, from 1770 onwards, a period of statue toppling, ''huri mo'ai'', commenced. This was an attempt by competing groups to destroy the socio-spiritual power, or ''mana'', represented by statues, making sure to break them in the fall to ensure they were dead and without power. None were left standing by the time of the arrival of the French missionaries in the 1860s.

Between 1862 and 1888, about 94% of the population perished or emigrated. The island was victimized by blackbirding

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people in ...

from 1862 to 1863, resulting in the abduction or killing of about 1,500, with 1,408 working as indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment ...

s in Peru. Only about a dozen eventually returned to Easter Island, but they brought smallpox, which decimated the remaining population of 1,500. Those who perished included the island's ''tumu ivi 'atua'', bearers of the island's culture, history, and genealogy besides the ''rongorongo

Rongorongo (Rapa Nui: ) is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) that appears to be writing or proto-writing. Numerous attempts at decipherment have been made, with none being successful. Although some c ...

'' experts.

Rapa Nui settlement

Estimated dates of initial settlement of Easter Island have ranged from 300 to 1200 CE, though the current best estimate for colonization is in the . Easter Island colonization likely coincided with the arrival of the first settlers in Hawaii. Rectifications in

Estimated dates of initial settlement of Easter Island have ranged from 300 to 1200 CE, though the current best estimate for colonization is in the . Easter Island colonization likely coincided with the arrival of the first settlers in Hawaii. Rectifications in radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

have changed almost all of the previously posited early settlement dates in Polynesia. Ongoing archaeological studies provide this late date: "Radiocarbon dates for the earliest stratigraphic layers at Anakena, Easter Island, and analysis of previous radiocarbon dates imply that the island was colonized late, about . Significant ecological impacts and major cultural investments in monumental architecture and statuary thus began soon after initial settlement."

According to oral tradition, the first settlement was at Anakena

Anakena is a white coral sand beach in Rapa Nui National Park on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. Anakena has two ahus; Ahu-Ature has a single moai and Ahu Nao-Nao has seven, two of which have deteriorated. It als ...

. Researchers have noted that the Caleta Anakena landing point provides the island's best shelter from prevailing swells as well as a sandy beach for canoe landings and launchings, so it is a likely early place of settlement. However radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

concludes that other sites preceded Anakena by many years, especially the Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by American archaeologist William Mulloy, Tahai comprises three principal ''ahu'' from north to south: Ko Te Riku (with res ...

by several centuries.

The island was populated by Polynesians who most likely navigated in canoes or catamaran

A Formula 16 beachable catamaran

Powered catamaran passenger ferry at Salem, Massachusetts, United States

A catamaran () (informally, a "cat") is a multi-hulled watercraft featuring two parallel hulls of equal size. It is a geometry-stab ...

s from the Gambier Islands

The Gambier Islands ( or ) are an archipelago in French Polynesia, located at the southeast terminus of the Tuamotu archipelago. They cover an area of , and are made up of the Mangareva Islands, a group of high islands remnants of a caldera alo ...

(Mangareva, away) or the Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' ( North Marquesan) and ' ( South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in th ...

, away. According to some theories, such as the Polynesian Diaspora Theory, there is a possibility that early Polynesian settlers arrived from South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

due to their remarkable sea-navigation abilities. Theorists have supported this through the agricultural evidence of the sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the Convolvulus, bindweed or morning glory family (biology), family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a r ...

. The sweet potato was a favoured crop in Polynesian society for generations but it originated in South America, suggesting interaction between these two geographic areas. However, recent research suggests that sweet potatoes may have spread to Polynesia by long-distance dispersal long before the Polynesians arrived. When James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

visited the island, one of his crew members, a Polynesian from Bora Bora

Bora Bora ( French: ''Bora-Bora''; Tahitian: ''Pora Pora'') is an island group in the Leeward Islands. The Leeward Islands comprise the western part of the Society Islands of French Polynesia, which is an overseas collectivity of the Frenc ...

, Hitihiti, was able to communicate with the Rapa Nui. The language most similar to Rapa Nui is Mangarevan

Mangareva, Mangarevan (autonym , ; in French ) is a Polynesian language spoken by about 600 people in the Gambier Islands of French Polynesia (especially the largest island Mangareva) and on the islands of Tahiti and Moorea, located to the Nort ...

, with an estimated 80% similar vocabulary. In 1999, a voyage with reconstructed Polynesian boats was able to reach Easter Island from Mangareva in 19 days.

According to oral traditions recorded by

According to oral traditions recorded by missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

in the 1860s, the island originally had a strong class system

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, incom ...

: an ''ariki'', or high chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

, wielded great power over nine other clans and their respective chiefs. The high chief was the eldest descendant through first-born lines of the island's legendary founder, Hotu Matu'a Hotu may refer to:

* Hotu Matu'a, legendary first settler of Easter Island

* The Yellow River Map

The acronym HOTU may stand for:

* Home of the Underdogs

Home of the Underdogs (often called HotU) is an abandonware archive founded by Sarinee Acha ...

. The most visible element in the culture was the production of massive moai statues that some believe represented deified ancestors. According to ''National Geographic'', "Most scholars suspect that the moai were created to honor ancestors, chiefs, or other important personages, However, no written and little oral history exists on the island, so it's impossible to be certain."

It was believed that the living had a symbiotic relationship

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

with the dead in which the dead provided everything that the living needed (health, fertility of land and animals, fortune etc.) and the living, through offerings, provided the dead with a better place in the spirit world. Most settlements were located on the coast, and most moai were erected along the coastline, watching over their descendants in the settlements before them, with their backs toward the spirit world in the sea.

In his book '' Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed'', Jared Diamond

Jared Mason Diamond (born September 10, 1937) is an American geographer, historian, ornithologist, and author best known for his popular science books ''The Third Chimpanzee'' (1991); ''Guns, Germs, and Steel'' (1997, awarded a Pulitzer Prize); ...

suggested that cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

took place on Easter Island after the construction of the moai contributed to environment

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

al degradation when extreme deforestation destabilized an already precarious ecosystem. Archeological record shows that at the time of the initial settlement the island was home to many species of trees, including at least three species which grew up to or more: ''Paschalococos

''Paschalococos disperta'', the Rapa Nui palm or Easter Island palm, formerly ''Jubaea disperta,'' was the native cocoid palm species of Easter Island. It disappeared from the pollen record circa AD 1650. Taxonomy

It is not known whether the spe ...

'' (possibly the largest palm trees in the world at the time), ''Alphitonia zizyphoides

''Alphitonia'' is a genus of arborescent flowering plants comprising about 20 species, constituting part of the buckthorn family ( Rhamnaceae). They occur in tropical regions of Southeast Asia, Oceania and Polynesia. These are large trees or shru ...

'', and '' Elaeocarpus rarotongensis.'' At least six species of land birds were known to live on the island. A major factor that contributed to the extinction of multiple plant species was the introduction of the Polynesian rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), known to the Māori as ''kiore'', is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. The Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asia, a ...

. Studies by paleobotanists have shown rats can dramatically affect the reproduction of vegetation in an ecosystem. In the case of Rapa Nui, recovered plant seed shells showed markings of being gnawed on by rats. Barbara A. West wrote, "Sometime before the arrival of Europeans on Easter Island, the Rapanui experienced a tremendous upheaval in their social system brought about by a change in their island's ecology... By the time of European arrival in 1722, the island's population had dropped to 2,000–3,000 from a high of approximately 15,000 just a century earlier."

By that time, 21 species of trees and all species of land birds became extinct through some combination of over-harvesting, over-hunting, rat predation, and climate change. The island was largely deforested

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated d ...

, and it did not have any trees taller than . Loss of large trees meant that residents were no longer able to build seaworthy vessels, significantly diminishing their fishing abilities. One theory is that the trees were used as rollers to move the statues to their place of erection from the quarry at Rano Raraku

Rano Raraku is a volcanic crater formed of consolidated volcanic ash, or tuff, and located on the lower slopes of Terevaka in the Rapa Nui National Park on Easter Island in Chile. It was a quarry for about 500 years until the early eighteenth cent ...

. Deforestation also caused erosion which caused a sharp decline in agricultural production. This was exacerbated by the loss of land birds and the collapse in seabird populations as a source of food. By the 18th century, islanders were largely sustained by farming, with domestic chickens as the primary source of protein.

Makemake

Makemake (minor-planet designation 136472 Makemake) is a dwarf planet and – depending on how they are defined – the second-largest Kuiper belt object in the classical population, with a diameter approximately 60% that of Pluto. It ...

, played an important role in this process. Katherine Routledge

Katherine Maria Routledge (), née Pease (11 August 1866 – 13 December 1935), was an English archaeologist and anthropologist who, in 1914, initiated and carried out much of the first true survey of Easter Island.

She was the second child o ...

, who systematically collected the island's traditions in her 1919 expedition, showed that the competitions for Bird Man (Rapa Nui: ''tangata manu

The ''Tangata manu'' ("bird-man," from "human beings" + "bird") was the winner of a traditional competition on Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The ritual was an annual competition to collect the first sooty tern () egg of the season from the islet of ...

'') started around 1760, after the arrival of the first Europeans, and ended in 1878, with the construction of the first church by Roman Catholic missionaries who formally arrived in 1864. Petroglyphs

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

representing Bird Men on Easter Island are the same as some in Hawaii, indicating that this concept was probably brought by the original settlers; only the competition itself was unique to Easter Island.

According to Diamond and Heyerdahl's version of the island's history, the ''huri mo'ai''"statue-toppling"continued into the 1830s as a part of fierce internal wars. By 1838, the only standing moai were on the slopes of Rano Raraku, in Hoa Hakananai'a

Hoa Hakananai'a is a moai, a statue from Easter Island. It was taken from Orongo, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in 1868 by the crew of a British ship and is now in the British Museum in London.

It has been described as a "masterpiece" and among th ...

in Orongo

Orongo is a stone village and ceremonial center at the southwestern tip of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). It consists of a collection of low, sod-covered, windowless, round-walled buildings with even lower doors positioned on the high south-westerly t ...

, and Ariki Paro in Ahu Te Pito Kura. A study headed by Douglas Owsley published in 1994 asserted that there is little archaeological evidence of pre-European societal collapse

Societal collapse (also known as civilizational collapse) is the fall of a complex human society characterized by the loss of cultural identity and of socioeconomic complexity, the downfall of government, and the rise of violence. Possible causes ...

. Bone pathology

Orthopedic pathology, also known as bone pathology is a subspecialty of surgical pathology which deals with the diagnosis and feature of many bone diseases, specifically studying the cause and effects of disorders of the musculoskeletal system. It ...

and osteometric

Osteometry is the study and measurement of the human or animal skeleton, especially in an anthropological or archaeological context.

In Archaeology it has been used to various ends in the subdisciplines of Zooarchaeology and Bioarchaeology.

...

data from islanders of that period clearly suggest few fatalities can be attributed directly to violence. Research by Binghamton University anthropologists Robert DiNapoli and Carl Lipo in 2021 determined that the island experienced steady population growth from its initial settlement until European contact in 1722. The island never had more than a few thousand people prior to European contact, and their numbers were increasing rather than dwindling.

European contact

The first recorded European contact with the island was on 5 April 1722,

The first recorded European contact with the island was on 5 April 1722, Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

, by Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen

Jacob Roggeveen (1 February 1659 – 31 January 1729) was a Dutch explorer who was sent to find Terra Australis and Davis Land, but instead found Easter Island (called so because he landed there on Easter Sunday). Jacob Roggeveen also found Bora ...

. His visit resulted in the death of about a dozen islanders, including the ''tumu ivi 'atua'', and the wounding of many others.

The next foreign visitors (on 15 November 1770) were two Spanish ships, ''San Lorenzo'' and ''Santa Rosalia'', under the command of Captain Don Felipe Gonzalez de Ahedo

Felipe is the Spanish language, Spanish variant of the name Philip (name), Philip, which derives from the Greek adjective ''Philippos'' "friend of horses". Felipe is also widely used in Portuguese language, Portuguese-speaking Brazil alongside Fili ...

. The Spanish were amazed by the "standing idols", all of which were erect at the time.

Four years later, in 1774, British explorer James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

visited Easter Island; he reported that some statues had been toppled. Through the interpretation of Hitihiti, Cook learned the statues commemorated their former high chiefs, including their names and ranks.

On 10 April 1786, French Admiral

On 10 April 1786, French Admiral Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse

Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse (; variant spelling: ''La Pérouse''; 23 August 17411788?), often called simply Lapérouse, was a French naval officer and explorer. Having enlisted at the age of 15, he had a successful naval caree ...

anchored at Hanga Roa at the start of a circumnavigation of the Pacific. He made a detailed map of the bay, including his anchorage points, as well as a more generalised map of the island, plus some illustrations.

19th century

A series of devastating events killed or removed most of the population in the 1860s. In December 1862,Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

vian slave raiders struck. Violent abductions continued for several months, eventually capturing around 1,500 men and women, half of the island's population. Among those captured were the island's paramount chief, his heir, and those who knew how to read and write the rongorongo

Rongorongo (Rapa Nui: ) is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) that appears to be writing or proto-writing. Numerous attempts at decipherment have been made, with none being successful. Although some c ...

script, the only Polynesian script to have been found to date, although debate exists about whether this is proto-writing

Proto-writing consists of visible marks communicating limited information. Such systems emerged from earlier traditions of symbol systems in the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium BC in Eastern Europe and China. They used ideograph ...

or true writing.

When the slave raiders were forced to repatriate the people they had kidnapped, carriers of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

disembarked together with a few survivors on each of the islands. This created devastating epidemics from Easter Island to the Marquesas

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' ( North Marquesan) and ' ( South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in t ...

islands. Easter Island's population was reduced to the point where some of the dead were not even buried.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, introduced by whalers in the mid-19th century, had already killed several islanders when the first Christian missionary, Eugène Eyraud

Eugène Eyraud (1820 – 23 August 1868) was a lay friar of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary and the first Westerner to live on Easter Island.

Early life

Eyraud was born in Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur, France, in 1820. He ...

, died from this disease in 1867. It ultimately killed approximately a quarter of the island's population. In the following years, the managers of the sheep ranch and the missionaries started buying the newly available lands of the deceased, and this led to great confrontations between natives and settlers.

Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier

Jean-Baptiste Onésime Dutrou-Bornier (19 November 1834 – 6 August 1876) was a French mariner who settled on Easter Island in 1868, purchased much of the island, removed many of the Rapa Nui people, and turned the island into a sheep ranch.

...

bought up all of the island apart from the missionaries' area around Hanga Roa

Hanga Roa (; rap, Haŋa Roa, Rapa Nui pronunciation: �ha.ŋa ˈɾo.a (Spanish: ''Bahía Larga'') is the main town, harbour and seat of Easter Island, a municipality of Chile. It is located in the southern part of the island's west coast, in th ...

and moved a few hundred Rapa Nui to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

to work for his backers. In 1871 the missionaries, having fallen out with Dutrou-Bornier, evacuated all but 171 Rapa Nui to the Gambier islands

The Gambier Islands ( or ) are an archipelago in French Polynesia, located at the southeast terminus of the Tuamotu archipelago. They cover an area of , and are made up of the Mangareva Islands, a group of high islands remnants of a caldera alo ...

. Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, only 111 people lived on Easter Island, and only 36 of them had any offspring. From that point on, the island's population slowly recovered. But with over 97% of the population dead or gone in less than a decade, much of the island's cultural knowledge had been lost.

Alexander Salmon, Jr.

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, the son of an English Jewish merchant and a Pōmare Dynasty

The Pōmare dynasty was the reigning family of the Kingdom of Tahiti between the unification of the islands by Pōmare I in 1788 and Pōmare V's cession of the kingdom to France in 1880. Their influence once spanned most of the Society Islands, ...

princess, eventually worked to repatriate workers from his inherited copra

Copra (from ) is the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted. Traditionally, the coconuts are sun-dried, especially for export, before the oil, also known as copra oil, is pressed out. The oil extracted from copr ...

plantation. He eventually bought up all lands on the island with the exception of the mission, and was its sole employer. He worked to develop tourism on the island and was the principal informant for the British and German archaeological expeditions for the island. He sent several pieces of genuine Rongorongo to his niece's husband, the German consul in Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, Chile. Salmon sold the Brander Easter Island holdings to the Chilean government on 2 January 1888, and signed as a witness to the cession of the island. He returned to Tahiti in December 1888. He effectively ruled the island from 1878 until his cession to Chile in 1888.

Easter Island was annexed by Chile on 9 September 1888 by Policarpo Toro

Policarpo Toro Hurtado (born in Melipilla, Chile on February 6, 1851 – died 1921 in Santiago, Chile) was a Chilean naval officer.

He enlisted in the Chilean Navy in 1871 and visited Easter Island in 1875. From 1877 to 1879, he joined the Engl ...

by means of the "Treaty of Annexation of the Island" (Tratado de Anexión de la isla). Toro, representing the government of Chile, signed with Atamu Tekena

Atamu Tekena or Atamu te Kena, full name Atamu Maurata Te Kena ʻAo Tahi (c. 1850 – August 1892) was the penultimate ‘Ariki or King of Rapa Nui (i.e. Easter Island) from 1883 until his death. He was appointed as the ruler in 1883 by the Fre ...

, designated "King" by the Roman Catholic missionaries after the paramount chief and his heir had died. The validity of this treaty is still contested by some Rapa Nui. Officially, Chile purchased the nearly all encompassing Mason-Brander sheep ranch, comprised from lands purchased from the descendants of Rapa Nui who died during the epidemics, and then claimed sovereignty over the island.

20th century

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapa Nui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapa Nui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the Williamson-Balfour Company

The Williamson-Balfour Company (or ''Williamson, Balfour and Company'') was a Scottish owned Chilean company. Its successor company, Williamson Balfour Motors S.A., is a subsidiary of the British company Inchcape plc.

The company was founded i ...

as a sheep farm until 1953. This exemplified the introduction of private property into Rapa Nui. The island was then managed by the Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy ( es, Armada de Chile) is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Origins and the Wars ...

until 1966, at which point the island was reopened in its entirety. The Rapa Nui were given Chilean citizenship in 1966.

Following the 1973 Chilean coup d'état

The 1973 Chilean coup d'état Enciclopedia Virtual > Historia > Historia de Chile > Del gobierno militar a la democracia" on LaTercera.cl. Retrieved 22 September 2006.

In October 1972, Chile suffered the first of many strikes. Among the par ...

that brought Augusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (, , , ; 25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean general who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, first as the leader of the Military Junta of Chile from 1973 to 1981, being declared President of ...

to power, Easter Island was placed under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. Tourism slowed, land was broken up, and private property was distributed to investors. During his time in power, Pinochet visited Easter Island on three occasions. The military built military facilities and a city hall.

After an agreement in 1985 between Chile and United States, the runway at Mataveri International Airport

Mataveri International Airport or Isla de Pascua Airport is at Hanga Roa on Rapa Nui / (Easter Island) (''Isla de Pascua'' in Spanish). The most remote airport in the world (defined as distance to another airport), it is from Santiago, Chile (S ...

was enlarged and was inaugurated in 1987. The runway was expanded , reaching . Pinochet is reported to have refused to attend the inauguration in protest at pressures from the United States over human rights.

21st century

illegal fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) is an issue around the world. Fishing industry observers believe IUU occurs in most fisheries, and accounts for up to 30% of total catches in some important fisheries.

Illegal fishing takes pl ...

on the island. "Since the year 2000 we started to lose tuna, which is the basis of the fishing on the island, so then we began to take the fish from the shore to feed our families, but in less than two years we depleted all of it", Pakarati said. On 30 July 2007, a constitutional reform gave Easter Island and the Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands ( es, Archipiélago Juan Fernández) are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic i ...

(also known as Robinson Crusoe Island

Robinson Crusoe Island ( es, Isla Róbinson Crusoe, ), formerly known as Más a Tierra (), is the second largest of the Juan Fernández Islands, situated 670 km (362 nmi; 416 mi) west of San Antonio, Chile, in the South Pacific Oc ...

) the status of "special territories" of Chile. Pending the enactment of a special charter, the island continues to be governed as a province of the V Region of Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

.

Species of fish were collected in Easter Island for one month in different habitats including shallow lava pools and deep waters. Within these habitats, two holotypes and paratypes

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype nor a syntype). Of ...

, ''Antennarius randalli

Randall's frogfish (''Antennarius randalli'') is a marine fish belonging to the family Antennariidae, the frogfishes.

Description

Randall's frogfish has long, claw-like pectoral fins that it uses for stabilization. The colors range from black ...

'' and ''Antennarius moai

''Antennarius moai'', commonly known as the Moai frogfish, is a species of fish native to Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, ...

'', were discovered. These are considered frog-fish because of their characteristics: "12 dorsal rays, last two or three branched; bony part of first dorsal spine slightly shorter than second dorsal spine; body without bold zebra-like markings; caudal peduncle short, but distinct; last pelvic ray divided; pectoral rays 11 or 12".

In 2018, the government decided to limit the stay period for tourists from 90 to 30 days because of social and environmental issues faced by the Island to preserve its historical importance.

A tsunami warning was declared for Easter Island after the 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai eruption and tsunami

On 20 December 2021, an eruption began on Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai, a submarine volcano in the Tongan archipelago in the southern Pacific Ocean. The eruption reached a very large and powerful climax nearly four weeks later, on 15 January 2022 ...

.

Easter Island was closed to tourists from March 17, 2020 until August 4, 2022 due to the COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first known case was COVID-19 pandemic in Hubei, identified in Wuhan, China, in December ...

pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic (epidemiology), endemic disease wi ...

. Then in early October 2022, just two months after the island was reopened to tourists, a forest fire burned nearly 148 acres (60 hectares) of the island, causing irreparable damage to some of the ''moai''. Arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

is suspected.

Indigenous rights movement

Starting in August 2010, members of the indigenous Hitorangi clan occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa. The occupiers allege that the hotel was bought from the Pinochet government, in violation of a Chilean agreement with the indigenous Rapa Nui, in the 1990s. The occupiers say their ancestors had been cheated into giving up the land. According to a

Starting in August 2010, members of the indigenous Hitorangi clan occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa. The occupiers allege that the hotel was bought from the Pinochet government, in violation of a Chilean agreement with the indigenous Rapa Nui, in the 1990s. The occupiers say their ancestors had been cheated into giving up the land. According to a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

report, on 3 December 2010, at least 25 people were injured when Chilean police using pellet guns attempted to evict from these buildings a group of Rapa Nui who had claimed that the land the buildings stood on had been illegally taken from their ancestors. In 2020 the conflict was settled. The property rights were transferred to the Hitorangi clan while the owners retained the exploitation of the hotel for 15 years.

In January 2011, the UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous People, James Anaya

Stephen James Anaya is an American lawyer and the 16th Dean of the University of Colorado Boulder Law School. He was formerly the James J. Lenoir Professor of Human Rights Law and Policy at the University of Arizona's James E. Rogers College of La ...

, expressed concern about the treatment of the indigenous Rapa Nui by the Chilean government, urging Chile to "make every effort to conduct a dialogue in good faith with representatives of the Rapa Nui people

The Rapa Nui (Rapa Nui: , Spanish: ) are the Polynesian peoples indigenous to Easter Island. The easternmost Polynesian culture, the descendants of the original people of Easter Island make up about 60% of the current Easter Island population and ...

to solve, as soon as possible the real underlying problems that explain the current situation". The incident ended in February 2011, when up to 50 armed police broke into the hotel to remove the final five occupiers. They were arrested by the government, and no injuries were reported.

Geography

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. Its closest inhabited neighbour is

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. Its closest inhabited neighbour is Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

, to the east, with approximately 50 inhabitants. The nearest continental point lies in central Chile near Concepción, at . Easter Island's latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

is similar to that of Caldera, Chile

Caldera is a port city and commune in the Copiapó Province of the Atacama Region in northern Chile. It has a harbor protected by breakwaters, being the port city for the productive mining district centering on Copiapó to which it is connected ...

, and it lies west of continental Chile at its nearest point (between Lota and Lebu Lebu may refer to:

* Lebu, Chile, a city and capital of the Arauco Province of the Biobio Region of Chile

* Lebu River, located in the Arauco Province of the Biobio Region of Chile

* LEBU, acronym for Large Eddy Break Up

* Libu or Lebu, Egyptian te ...

in the Biobío Region

The Biobío Region ( es, Región del Biobío ), is one of Chile's sixteen regions of Chile, regions (first-order administrative divisions). With a population of 1.5 million, thus being the third most populated region in Chile, it is divided int ...

). Isla Salas y Gómez

Isla Salas y Gómez, also known as Isla Sala y Gómez ( rap, Motu Motiro Hiva), is a small uninhabited Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. It is sometimes considered the easternmost point in the Polynesian Triangle.

Isla Salas y Gómez and its s ...

, to the east, is closer but is uninhabited. The Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying approximately from Cape Town in South Africa, from Saint Helena ...

archipelago in the southern Atlantic competes for the title of the most remote island, lying from Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

island and from the South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

n coast.

The island is about long by at its widest point; its overall shape is triangular. It has an area of , and a maximum elevation of above mean sea level. There are three ''Rano'' (freshwater crater lake

Crater Lake (Klamath language, Klamath: ''Giiwas'') is a volcanic crater lake in south-central Oregon in the western United States. It is the main feature of Crater Lake National Park and is famous for its deep blue color and water clarity. The ...

s), at Rano Kau

Rano Kau is a tall dormant volcano that forms the southwestern headland of Easter Island, a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. It was formed of basaltic lava flows in the Pleistocene with its youngest rocks dated at between 150,000 and 210,0 ...

, Rano Raraku and Rano Aroi, near the summit of Terevaka, but no permanent streams or rivers.

Geology

Easter Island is a

Easter Island is a volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

high island

Geologically, a high island or volcanic island is an island of volcanic origin. The term can be used to distinguish such islands from low islands, which are formed from sedimentation or the uplifting of coral reefs (which have often formed ...

, consisting mainly of three extinct coalesced volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

es: Terevaka

Ma′unga Terevaka is the largest, tallest () and youngest of three main extinct volcanoes that form Easter Island. Several smaller volcanic cones and craters dot its slopes, including a crater hosting one of the island's three lakes, Rano Aroi. ...

(altitude 507 metres) forms the bulk of the island, while two other volcanoes, Poike

Poike is one of the three main extinct volcanoes that form Rapa Nui (Easter Island), a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. At 370 metres above sea level, Poike's peak is the island's second-highest point after the peak of the extinct volcano T ...

and Rano Kau, form the eastern and southern headlands and give the island its roughly triangular shape. Lesser cones and other volcanic features include the crater Rano Raraku, the cinder cone

A cinder cone (or scoria cone) is a steep conical hill of loose pyroclastic fragments, such as volcanic clinkers, volcanic ash, or scoria that has been built around a volcanic vent. The pyroclastic fragments are formed by explosive eruptions o ...

Puna Pau

Maunga Puna Pau is a small crater or cinder cone and prehistoric quarry on the outskirts of Hanga Roa in the south west of Easter Island (a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean). Puna Pau gives its name to one of the seven regions of the Rapa Nui ...

and many volcanic caves including lava tubes

A lava tube, or pyroduct, is a natural conduit formed by flowing lava from a volcanic vent that moves beneath the hardened surface of a lava flow. If lava in the tube empties, it will leave a cave.

Formation

A lava tube is a type of lava ca ...

.

Poike used to be a separate island until volcanic material from Terevaka united it to the larger whole. The island is dominated by hawaiite

Hawaiite is an olivine basalt with a composition between alkali basalt and mugearite. It was first used as a name for some lavas found on the island of Hawaii.

It occurs during the later stages of volcanic activity on oceanic islands such as Haw ...

and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

flows which are rich in iron and show affinity with igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main The three types of rocks, rock types, the others being Sedimentary rock, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, metamorphic. Igneous rock ...

s found in the Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

.

Easter Island and surrounding islets, such as Motu Nui

Motu Nui (''large island'' in the Rapa Nui language) is the largest of three islets just south of Easter Island and is the List of extreme points of Chile, most westerly place in Chile and all of South America. All three islets have seabirds, ...

and Motu Iti, form the summit of a large volcanic mountain rising over from the sea bed. The mountain is part of the Salas y Gómez Ridge, a (mostly submarine) mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

with dozens of seamount

A seamount is a large geologic landform that rises from the ocean floor that does not reach to the water's surface (sea level), and thus is not an island, islet or cliff-rock. Seamounts are typically formed from extinct volcanoes that rise abru ...

s, formed by the Easter hotspot

The Easter hotspot is a volcanic hotspot located in the southeastern Pacific Ocean. The hotspot created the Sala y Gómez Ridge which includes Easter Island, Salas y Gómez Island and the Pukao Seamount which is at the ridge's young western ed ...

. The range begins with Pukao

Pukao are the hat-like structures or topknots formerly placed on top of some moai statues on Easter Island. They were all carved from a very light-red volcanic scoria, which was quarried from a single source at Puna Pau.

Symbolism

Pukao were not ...

and next Moai

Moai or moʻai ( ; es, moái; rap, moʻai, , statue) are monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui people on Easter Island, Rapa Nui in eastern Polynesia between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main mo ...

, two seamounts to the west of Easter Island, and extends east to the Nazca Ridge

The Nazca Ridge is a submarine ridge, located on the Nazca Plate off the west coast of South America. This plate and ridge are currently subducting under the South American Plate at a convergent boundary known as the Peru-Chile Trench at approx ...

. The ridge was formed by the Nazca Plate

The Nazca Plate or Nasca Plate, named after the Nazca region of southern Peru, is an oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin off the west coast of South America. The ongoing subduction, along the Peru–Chile Trench, of the Na ...

moving over the Easter hotspot.

Located about east of the East Pacific Rise

The East Pacific Rise is a mid-ocean rise (termed an oceanic rise and not a mid-ocean ridge due to its higher rate of spreading that results in less elevation increase and more regular terrain), a divergent tectonic plate boundary located along ...

, Easter Island lies within the Nazca Plate, bordering the Easter Microplate

Easter Plate is a tectonic List of tectonic plates#Microplates, microplate located to the west of Easter Island off the west coast of South America in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, bordering the Nazca Plate to the east and the Pacific Plate to ...

. The Nazca-Pacific relative plate movement due to the seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

, amounts to about per year. This movement over the Easter hotspot has resulted in the Easter Seamount Chain, which merges into the Nazca Ridge further to the east. Easter Island and Isla Salas y Gómez

Isla Salas y Gómez, also known as Isla Sala y Gómez ( rap, Motu Motiro Hiva), is a small uninhabited Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. It is sometimes considered the easternmost point in the Polynesian Triangle.

Isla Salas y Gómez and its s ...

are surface representations of that chain. The chain has progressively younger ages to the west. The current hotspot location is speculated to be west of Easter Island, amidst the Ahu, Umu and Tupa submarine volcanic fields and the Pukao and Moai seamounts.

Easter Island lies atop the Rano Kau Ridge, and consists of three shield volcanoes

A shield volcano is a type of volcano named for its low profile, resembling a warrior's shield lying on the ground. It is formed by the eruption of highly fluid (low viscosity) lava, which travels farther and forms thinner flows than the more vi ...

with parallel geologic histories. Poike and Rano Kau exist on the east and south slopes of Terevaka, respectively. Rano Kau developed between 0.78 and 0.46 Ma from tholeiitic

The tholeiitic magma series is one of two main magma series in subalkaline igneous rocks, the other being the calc-alkaline series. A magma series is a chemically distinct range of magma compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma i ...