Dyula people on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

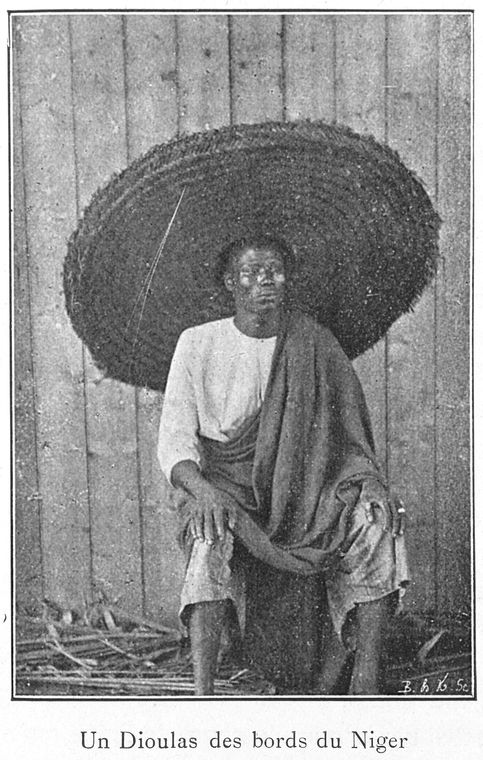

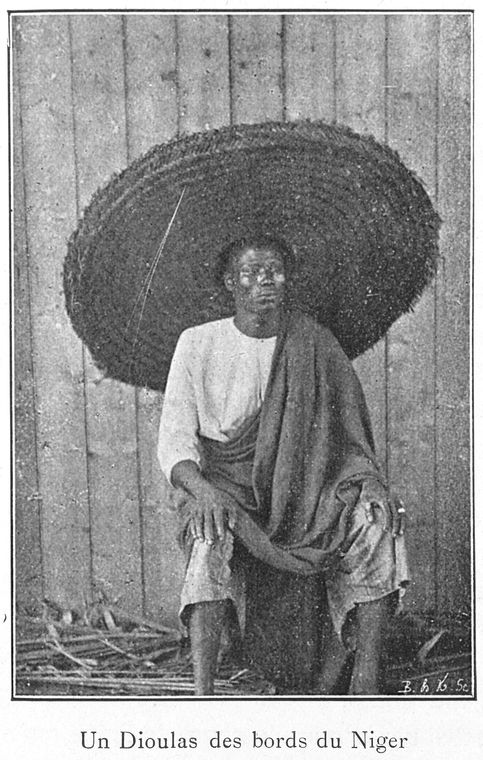

The Dyula (Dioula or Juula) are a Mande

The Mandé embraced Islam during the thirteenth century following introduction to the faith through contact with the

The Mandé embraced Islam during the thirteenth century following introduction to the faith through contact with the

Over time ''dyula'' colonies developed a

Over time ''dyula'' colonies developed a

''Dyula'' society is hierarchical or

''Dyula'' society is hierarchical or

ethnic group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

inhabiting several West African

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Ma ...

countries, including Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

, Cote d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

, Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, and Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the ...

.

Characterized as a highly successful merchant caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

, ''Dyula'' migrants began establishing trading communities across the region in the fourteenth century. Since business was often conducted under non-Muslim rulers, the ''Dyula'' developed a set of theological principles for Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

minorities in non-Muslim societies. Their unique contribution of long-distance commerce, Islamic scholarship and religious tolerance were significant factors in the peaceful expansion of Islam in West Africa.

Historical background

The Mandé embraced Islam during the thirteenth century following introduction to the faith through contact with the

The Mandé embraced Islam during the thirteenth century following introduction to the faith through contact with the North African

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

traders. By the 14th century, the Malian empire

The Mali Empire (Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or Manden; ar, مالي, Māl� ...

(c.1230-1600) had reached its apogee, acquiring a considerable reputation for the Islamic rulings of its court and the pilgrimages of several emperors who followed the tradition of Lahilatul Kalabi, the first black prince to make ''hajj

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried ...

'' to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

. It was at this time that Mali began encouraging some of its local merchants to establish colonies close to the gold fields of West Africa. This migrant trading class were known as ''Dyula'', the Mandingo word for “merchant”.

The ''Dyula'' spread throughout the former area of Mandé culture from the Atlantic coast of Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

to the Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesSahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

to forest zones further south. They established decentralized townships in non-Muslim colonies that were linked to an extensive commercial network, in what was described by professor Philip D. Curtin as a “trading diaspora.” Motivated by business imperatives, they expanded into new markets, founding settlements under the auspices of various local rulers who often permitted them self-governance and autonomy. Organization of ''dyula'' trading companies was based on a clan-family structure known as the ''lu'' - a working unit consisting of a father and his sons and other attached males. Members of a given ''lu'' dispersed from the savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

to the forest, managed circulation of goods and information, placed orders, and effectively controlled the economic mechanisms of supply and demand

In microeconomics, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a Market (economics), market. It postulates that, Ceteris paribus, holding all else equal, in a perfect competition, competitive market, the unit price for a ...

.

Suwarian tradition

Over time ''dyula'' colonies developed a

Over time ''dyula'' colonies developed a theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

rationale for their relations with non-Muslim ruling classes and subjects in what author Nehemia Levtzion

Nehemia Levtzion ( he, נחמיה לבציון; November 24, 1935 — August 15, 2003) was an Israeli scholar of African history, Near East, Islamic, and African studies, and the President of the Open University of Israel from 1987 to 1992 and the ...

dubbed “accommodationist Islam”. The man credited with formulating this rationale is Sheikh Al-Hajj Salim Suwari

Sheikh Al-Hajj Salim Suwari was a 13th-century West African Soninke ''karamogo'' ( Islamic scholar) who focused on the responsibilities of Muslims minorities residing in a non-Muslim society. He formulated an important theological rationale for ...

, a Soninke cleric from the core Mali area who lived around 1500. He made ''hajj'' to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

several times and devoted his intellectual career to developing an understanding of the faith that would assist Muslim minorities in “pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

” lands. He drew on North African and Middle Eastern jurists and theologians

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

who had reflected on the problem of Muslims living among non-Muslim majorities, situations that were frequent in the centuries of Islamic expansion.

Sheikh Suwari formulated the obligations of Muslim minorities in West Africa into something known as the ''Suwarian tradition''. It stressed the need for Muslims to coexist peaceably with unbelievers and so justified a separation of religion and politics. In this understanding, Muslims must nurture their own learning and piety and thereby furnish good examples to the non-Muslims around them. They could accept jurisdiction of non-Muslim authorities as long as they had the necessary protection and conditions to practice the faith. In this teaching, Suwari followed a strong predilection in Islamic thought for any government, even if non-Muslim or tyrannical, as opposed to none. The military ''jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

'' was a resort only if the faithful were threatened. Suwari discouraged ''dawah

Dawah ( ar, دعوة, lit=invitation, ) is the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam. The plural is ''da‘wāt'' (دَعْوات) or ''da‘awāt'' (دَعَوات).

Etymology

The English term ''Dawah'' derives from the Arabic ...

'' (missionary activity), instead contending that Allah

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", an ...

would bring non-Muslims to Islam in His own way; it was not a Muslim's responsibility to decide when ignorance should give way to belief. Since their Islamic practice was capable of accommodating traditional cults, ''dyula'' often served as priests, soothsayers, and counselors at the courts of animist

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, Soul, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct Spirituality, spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—Animal, animals, Plant, plants, Ro ...

rulers.

Commercial and political expansion

As fellow Muslims, ''dyula'' merchants were also able to assess the valuabletrans-Saharan trade

Trans-Saharan trade requires travel across the Sahara between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa. While existing from prehistoric times, the peak of trade extended from the 8th century until the early 17th century.

The Sahara once had a very d ...

network conducted by North African Arabs and Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

whom they met at commercial centers across the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid c ...

. Some important trade goods included gold, millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

, slaves, and kola nuts from the south and slave beads and cowrie shells

Cowrie or cowry () is the common name for a group of small to large sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Cypraeidae, the cowries.

The term ''porcelain'' derives from the old Italian term for the cowrie shell (''porcellana'') du ...

from the north (for use as currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general def ...

). It was under Mali that the great cities of the Niger bend including Gao

Gao , or Gawgaw/Kawkaw, is a city in Mali and the capital of the Gao Region. The city is located on the River Niger, east-southeast of Timbuktu on the left bank at the junction with the Tilemsi valley.

For much of its history Gao was an impor ...

and Djenné

Djenné ( Bambara: ߘߖߋߣߣߋ tr. Djenne; also known as Djénné, Jenné and Jenne) is a Songhai people town and an urban commune in the Inland Niger Delta region of central Mali. The town is the administrative centre of the Djenné Cercle, on ...

prospered, with Timbuktu in particular becoming known across Europe for its great wealth. Important trading centers in Southern West Africa developed at the transitional zone between the forest and the savanna; examples include Begho

Bono State (or Bonoman) was a trading state created by the Bono people, located in what is now southern Ghana. Bonoman was a medieval Akan kingdom in what is now Bono, Bono East and Ahafo region respectively named after the ( Bono and Ahafo) a ...

and Bono Manso

Bono State (or Bonoman) was a trading state created by the Bono people, located in what is now southern Ghana. Bonoman was a medieval Akan kingdom in what is now Bono, Bono East and Ahafo region respectively named after the ( Bono and Ahafo) a ...

(in present-day Ghana) and Bondoukou

Bondoukou (var. Bonduku, Bontuku) is a city in northeastern Ivory Coast, 420 km northeast of Abidjan. It is the seat of both Zanzan District and Gontougo Region. It is also a commune and the seat of and a sub-prefecture of Bondoukou Departm ...

(in present-day Côte d'Ivoire). Western trade routes continued to be important, with Ouadane

, settlement_type = Commune and town

, image_skyline = OuadaneOldTown1.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption = Old tower, Ouadane

, image_flag =

, im ...

, Oualata

, settlement_type = Communes of Mauritania, Commune and town

, image_skyline = Oualata 03.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, image_caption = View of the town looking in a southeas ...

and Chinguetti

Chinguetti () ( ar, شنقيط, translit=Šinqīṭ) is a ksar and a medieval trading center in northern Mauritania, located on the Adrar Plateau east of Atar.

Founded in the 13th century as the center of several trans-Saharan trade routes, this ...

being the major trade centres in what is now Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

.

Penetration into southern forest regions

The development of ''Dyula'' trade in Ghana and the adjacent Ivory Coast had important political consequences and sometimes military implications as well. The ''dyula'' spearheaded Mande penetration of the forested zones in the south by establishing caravan routes and trading posts at strategic locations throughout the region en route to cola-producing areas. By the start of the sixteenth century, ''dyula'' merchants were trading as far south as the coast of modern Ghana. On the forest's northern fringes, new states emerged, such asBono

Paul David Hewson (born 10 May 1960), known by his stage name Bono (), is an Irish singer-songwriter, activist, and philanthropist. He is the lead vocalist and primary lyricist of the rock band U2.

Born and raised in Dublin, he attended M ...

and Banda. As the economic value of gold and kola became appreciated, forests south of these states which had hitherto been little inhabited because of limited agricultural potential became more thickly populated, and the same principles of political and military mobilization began being applied there. Village communities became tributaries of ruling groups, with some members becoming the clients and slaves needed to support royal households, armies, and trading enterprises. Sometimes these political changes were not to the advantage of the ''Dyula'', who employed Mande warriors to guard their caravans and if necessary could call in larger contingents from the Sudanic kingdoms. In the seventeenth century, tensions between the Muslims and the local pagans in Begho erupted into a destructive war which eventually led to the total abandonment of the Banda capital. The local people eventually settled in a number of towns further east, while the dyula withdrew to the west to the further side of the Banda hills where they established the new trading center of Bonduku

Bondoukou (var. Bonduku, Bontuku) is a city in northeastern Ivory Coast, 420 km northeast of Abidjan. It is the seat of both Zanzan District and Gontougo Region. It is also a Communes of Ivory Coast, commune and the seat of and a sub-prefect ...

.

Gonja state

The ''dyula'' presence and changes in the balance of power occasioned political upheavals in other places. Among the paramount Mande political initiatives along trade routes south of Jenne was creation of the ''dyula'' state of Gonja by Naba'a in the 16th century. This was motivated by a general worsening of the competitive position of dyula traders and was occasioned by three factors: (1) a near-monopoly control in exporting forest produce achieved by the Akan kingdom of Bono; (2) the rise to power further north of the Dagomba Kingdom which controlled local salt pans; and (3) increased competition following the arrival in the region of rival long-distance traders fromHausaland

The Hausa ( autonyms for singular: Bahaushe ( m), Bahaushiya ( f); plural: Hausawa and general: Hausa; exonyms: Ausa; Ajami: ) are the largest native ethnic group in Africa. They speak the Hausa language, which is the second most spoken languag ...

.

The reaction of the Dyula in the Bono-Banda-Gonja region to these developments was to establish a kingdom of their own in Gonja - the territory northern traders had to cross to reach Akan forestlands, situated in what is now modern Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

. By 1675, Gonja had established a paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a chief-based system. This term is used occasionally in anthropological and arch ...

called Yagbongwura

List of rulers of Gonja, a kingdom located in the north of Ghana

(Dates in italics indicate ''de facto ''continuation of office)

See also

*Ghana

*Gold Coast

* Lists of office-holders

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gonja, Rulers

Rulers

A ruler, s ...

to control the kingdom. But Gonja was not a fruitful land in which to try to maintain a centralized government. This is because the Dagomba power to the north and Akan power to the south were too powerful; thus, the new kingdom rapidly declined in strength.

Kong Empire

Many of the trading posts established by the ''Dyula'' eventually became market villages or cities, such as Kong in today's Northeastern Côte d'Ivoire. It emerged as a commercial center when Malian merchants began trading in the territory which was inhabited by pagan Senufo and other Voltaic groups. The sous-préfecture of Kong, in the area of Kong toDabakala

Dabakala is a town in northeast Ivory Coast. It is a sub-prefecture of and the seat of Dabakala Department in Hambol Region, Vallée du Bandama District. Dabakala is also a commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. ...

, is said to be the “origin” area, where ''dyula'' traders first settled in the twelfth century. ''Dyula'' presence in the Kong area grew rapidly in the seventeenth century as a result of the developing trade between the commercial centers along the Niger banks and the forest region to the south which was controlled by the Baule chiefdoms and the Ashanti. The ''dyula'' brought their trading skills and connections and transformed Kong into an international market for the exchange of northern desert goods, such as salt and cloth, and southern forest exports, such as cola nuts, gold, and slaves. The city was also a religious center that housed a substantial academic community of Muslim scholars, with palaces and mosques built in the traditional Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

ese style. As Kong grew prosperous, its early rulers from the Taraweré clan combined ''dyula'' and Senufo traditions and extended their authority over the surrounding region.

By the eighteenth century the ''dyula'' had become quite powerful in the area and wished to rid themselves of subordination to Senufo chiefs. This was achieved in an uprising led by Seku Wattara (Ouattara), a ''dyula'' warrior who claimed descent from the Malinke Keita lineage and who had studied the Quran and engaged in commerce before becoming a warrior. By rallying around himself all ''dyula'' in the area, Seku Wattara easily defeated local chiefdoms and set up an independent ''Dyula'' state in 1710, the first of its kind in West Africa. He established himself as ruler and under his authority, the city rose from a small city-state to the capital of the great Kong Empire

The Kong Empire (1710–1898), also known as the Wattara Empire or Ouattara Empire for its founder, was a pre-colonial African Muslim state centered in northeastern Ivory Coast that also encompassed much of present-day Burkina Faso. It was fo ...

, holding sway over much of the region. The ''dyula'' of Kong also maintained commercial links with European traders on the Atlantic coast around the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is in the ...

, from whom they easily obtained prized European goods, most notably rifles, gunpowder, and textiles. The acquisition of weapons allowed for the creation of an armed militia force that protected trade routes passing through the territories of various minor rulers. In the course of developing his state, Seku Wattara built a strong army composed mostly of defeated pagan groups. The leadership of the army eventually developed into a new warrior class, called ''sonangi'', which was gradually separated from the overall ''dyula'' merchant class.

The Kong Empire started to decline after the death of Seku Wattara. Succession struggles divided the kingdom into two parts, with the northern area being controlled by Seku's brother Famagan who refused to recognize the rule of Seku's oldest son in the south. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, many of Kong's provinces had formed independent chiefdoms. The city of Kong retained the prestige of an Islamic commercial center, but it was no longer the seat of an important political power. It eventually came under French colonial control in 1898. Despite the fall from glory, the seventeenth-century Kong Friday Mosque survived, and the city was largely rebuilt in a traditional Sudano-Sahelian architectural style and features a Qur'anic school.

Kingdom of Wasulu

The Mande conquerors of the nineteenth century frequently utilized trade routes established by the ''Dyula''. Indeed, it was his exploitation of their commercial network that allowed military leaderSamory Touré

Samory Toure ( – June 2, 1900), also known as Samori Toure, Samory Touré, or Almamy Samore Lafiya Toure, was a Muslim cleric, a military strategist, and the founder and leader of the Wassoulou Empire, an Islamic empire that was in present-day ...

(1830–1900) to rise to a dominant position in the Upper Niger

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mali, ...

region. A member of a ''dyula'' family from Sanankoro in Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

, Samori conquered and united ''Dyula'' states during the 1860s. He gained control over the Milo River Valley in 1871, seized the village of Kankan

Kankan ( Mandingo: Kánkàn; N’ko: ߞߊ߲ߞߊ߲߫) is the largest city in Guinea in land area, and the third largest in population, with a population of 1 980 130 people as of 2020. The city is located in eastern Guinea about east of the ...

in 1881, and became the principal power holder on the Upper Niger. By 1883, Samori had successfully brought the local chieftains under his control and officially founded the kingdom of Wasulu

Wassoulou is a cultural area and historical region in the Wassoulou River Valley of West Africa. It is home to about 160,000 people, and is also the native land of the Wassoulou genre of music.

Wassoulou surrounds the point where the border ...

.

Having established an empire, he adopted the religious title of ''Almami

Almami ( ar, المامي; Also: Almamy, Almaami) was the regnal title of Tukulor monarchs from the eighteenth century through the first half of the twentieth century. It is derived from the Arabic Al-Imam, meaning "the leader", and it has since ...

'' in 1884 and recreated the Malian realm. This new state was governed by Samori and a council of kinsmen and clients who took on the management of the chancery and the treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in p ...

, and administered justice, religious affairs, and foreign relations

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through mu ...

. Unlike some of his contemporary state-builders, Samori was not a religious preacher, and Wasulu was not a reformist state as such. Nevertheless, he used Islam to unify the nation, promoting Islamic education and basing his rule on ''shari’a

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

'' (Islamic law). However, Samori's professional army was the essential institution and the real strength behind his empire. He imported horses and weapons and modernized the army along European lines.

''Dyula'' traders had never enjoyed as much prosperity as they did under the ''almamy''. Even though they did not play a central part in the creation of the state, the ''dyula'' supported Samori because he actively encouraged commerce and protected trade routes, thus promoting a free circulation of people and goods. Samori put up the strongest resistance to European colonial penetration in West Africa, fighting both the French and British for seventeen years. Samori's would-be Muslim empire was undone by the French, who took Sikasso

Sikasso ( Bambara: ߛߌߞߊߛߏ tr. Sikaso) is a city in the south of Mali and the capital of the Sikasso Cercle and the Sikasso Region. It is Mali's second largest city with 225,753 residents in the 2009 census.

History

Sikasso was founded ...

in 1898, and sent Samori into exile, where he died in 1900.

Dyula culture and society

''Dyula'' society is hierarchical or

''Dyula'' society is hierarchical or caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

-based, with nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

and vassals. Like numerous other African peoples, they previously held slaves (''jonw''), who were often war prisoners from lands surrounding their territory. Descendants of former kings and generals had a higher status than their nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

and more settled compatriots. With time, that difference has eroded, corresponding to the economic fortunes of the groups.

The traditional ''dyula'' social structure is further organized into various familial clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

groups, and clan affiliation continues to be a dominant aspect of both collective and individual identity. People are fiercely loyal to their clan lineage, often expressing their cultural history and devotion through the oral traditions of dance and storytelling. The ''dyula'' are patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

and patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of Dominance hierarchy, dominance and Social privilege, privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical Anthropology, anthropological term for families or clans controll ...

, with older males possessing the most power and influence. Men and women commonly reside in separate houses made of mud or cement - men occupying roundhouses and women in rectangular ones. The father heads the family, and inheritances are passed down from fathers to their sons. Despite being illegal, the ''dyula'' still practice polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

, and young people are often encouraged to marry within their own clan.

Another hereditary class that was afforded a particularly important status by the ''dyula'' social hierarchy was occupied by the ''tuntigi'' or warrior class. The ''dyula'' had long been accustomed to surrounding their cities with fortifications and taking up arms when it was deemed necessary in order to defend themselves and maintain the smooth flow of trade caravans. As a result, they became closely associated with the ''tuntigi'' warriors.

Islamic tradition

The ''dyula'' have been predominantly Muslim since the 13th century. Many in rural areas combine Islamic beliefs with certain pre-Islamic animistic traditions such as the presence of spirits and use ofamulets

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects ...

. ''Dyula'' communities have a reputation for historically maintaining a high standard of Muslim education. The ''dyula'' family enterprise based on the ''lu'' could afford to provide some of its younger men an Islamic education. Thus, an ''ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' (clerical) class known as karamogo

The Karamogo were the scholar class among the peaceful Dyula traders of Western Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso ...

emerged, who were educated in the Quran and commentary (''tafsir

Tafsir ( ar, تفسير, tafsīr ) refers to exegesis, usually of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' ( ar, مُفسّر; plural: ar, مفسّرون, mufassirūn). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, in ...

''), ''hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'' (prophetic narrations), and the life of Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

. According to the ''dyula'' clerical tradition, a student received instruction under a single ''sheikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

'' for a duration varying from five to thirty years, and earned his living as a part-time farmer working his teacher's lands. After he completed his studies, a ''karamogo'' obtained a turban and an ''isnad

Hadith studies ( ar, علم الحديث ''ʻilm al-ḥadīth'' "science of hadith", also science of hadith, or science of hadith criticism or hadith criticism)

consists of several religious scholarly disciplines used by Muslim scholars in th ...

'' (teaching license), and either sought further instruction or started his own school in a remote village. A highly educated ''karamogo'' could become a professional ''imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, ser ...

'' or ''qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

'' (judge).

Certain families gained a reputation for providing multiple generations of scholars. For example, the Saghanughu clan was a ''dyula'' lineage living in Northern and Western Ivory Coast and parts of the Upper Volta. This lineage may be traced to Timbuktu, but its principal figure was Sheikh Muhammad al-Mustafa Saghanughu (d. 1776), the ''imam'' of Bobo-Dyulasso. He produced an educational system based on three canonical texts of Quranic commentary (''tafsir

Tafsir ( ar, تفسير, tafsīr ) refers to exegesis, usually of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' ( ar, مُفسّر; plural: ar, مفسّرون, mufassirūn). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, in ...

'') and ''hadith''. His sons continued spreading their father's teachings and expanded through towns in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, founding Islamic schools, or madaris, and acting as ''imams'' and ''qadis''.

These ''madaris'' were probably a positive byproduct of the long history of Muslims’ interest in literary work. In "''The Islamic Literary Tradition in Ghana''", author Thomas Hodgkin

Thomas Hodgkin RMS (17 August 1798 – 5 April 1866) was a British physician, considered one of the most prominent pathologists of his time and a pioneer in preventive medicine. He is now best known for the first account of Hodgkin's disease, ...

enumerates the large literary contribution that was made by Dyula- Wangara Muslims to the history of not only the regions they found themselves in but also of West Africa as a whole. He cites al-Hajj Osmanu Eshaka Boyo of Kintampo as an “ ‘alim'' with a wide range of Muslim connexions and an excellent grasp of local Islamic history” whose efforts brought together a great many Arabic manuscripts from around Ghana. These manuscripts, the ''Isnad al-shuyukh wa’l-ulama'', or ''Kitab Ghunja'', compiled by al-Hajj ‘Umar ibn Abi Bakr ibn ‘Uthman al-Kabbawi al-Kanawi al-Salaghawi of Kete-Krachi who Hodgkin describes as “the most interesting, and historically significant of the poets,” may now be found in the library of the Institute of African Studies

The Institute of African Studies on the Anne Jiagee road on campus of the University of Ghana at Legon is an interdisciplinary research institute in the humanities and social sciences. It was established by President Kwame Nkrumah in 1962 to encou ...

of the University of Ghana

The University of Ghana is a public university located in Accra, Ghana. It the oldest and largest of the thirteen Ghanaian national public universities.

The university was founded in 1948 as the University College of the Gold Coast in the Br ...

.

Dioula language

The ''dyula'' speak the Dioula language or ''Julakan'', which is included in the group of closely interrelatedManding languages

The Manding languages (sometimes spelt Manden) are a dialect continuum within the Mande language family spoken in West Africa. Varieties of Manding are generally considered (among native speakers) to be mutually intelligible – dependent on exp ...

that are spoken by various ethnic groups spread across Western Africa. Dioula is most closely related to the Bambara language

Bambara (Arabic script: ), also known as Bamana (N'Ko script: ) or Bamanankan (), is a lingua franca and national language of Mali spoken by perhaps 15 million people, natively by 5 million Bambara people and about 10 million second-language us ...

(the most widely spoken language in Mali), in a manner similar to the relation between American English and British English. It is probably the most used language for trade in West Africa.

The Dioula language and people are distinct from the Diola

The Jola or Diola (endonym: Ajamat) are an ethnic group found in Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau. Most Jola live in small villages scattered throughout Senegal, especially in the Lower Casamance region. The main dialect of the Jola langu ...

(Jola) people of Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

and Casamance

, settlement_type = Geographical region

, image_skyline = Senegal Casamance.png

, image_caption = Casamance in Senegal

, image_flag = Flag of Casamance.svg

, image_shield =

, motto ...

.

Notable Dyula people

*Al-Hajj Salim Suwari

Sheikh Al-Hajj Salim Suwari was a 13th-century West African Soninke ''karamogo'' ( Islamic scholar) who focused on the responsibilities of Muslims minorities residing in a non-Muslim society. He formulated an important theological rationale for ...

, a 13th-century ''karamogo

The Karamogo were the scholar class among the peaceful Dyula traders of Western Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso ...

'' (Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the mai ...

scholar).

* Alban Lafont

* Amadou Touré

*Amadou Ouattara

Amadou Ouattara (born 30 December 1990) is an Ivorian professional footballer who plays for Thai League 1 club Chonburi

Chonburi ( th, ชลบุรี, , IAST: , ) is the capital of Chonburi Province and Mueang Chonburi District in Thailand ...

, Footballer

* Christian Manfredini

Christian José Manfredini Sisostri (born 1 May 1975) is an Ivory Coast, Ivorian retired association football, footballer who played as a Midfielder#Wide midfielder, left midfielder or Midfielder#Winger, left winger. Manfredini also holds Italia ...

* Cyrille Bayala

Cyrille Bayala (born 24 May 1996) is a Burkinabé professional footballer who plays as a winger for club Ajaccio and the Burkina Faso national team.

Club career

On 31 August 2016, Bayala signed for Moldovan club Sheriff Tiraspol.

A year la ...

* Issouf Ouattara

* Kalpi Ouattara

* Mohamed Ouattara

* Modibo Sagnan

* Mohamed Touré

*Samory Touré

Samory Toure ( – June 2, 1900), also known as Samori Toure, Samory Touré, or Almamy Samore Lafiya Toure, was a Muslim cleric, a military strategist, and the founder and leader of the Wassoulou Empire, an Islamic empire that was in present-day ...

(1830–1900)

*Kolo Touré

Kolo Abib Touré (born 19 March 1981) is an Ivorian professional football coach and former player who is the manager of Championship side Wigan Athletic. He played as a defender for Arsenal, Manchester City, Liverpool, Celtic and the Ivory Coas ...

, Ivorian footballer

*Yaya Touré

Gnégnéri Yaya Touré (born 13 May 1983) is an Ivorian professional football coach and former player who played as a midfielder. He is an academy coach for Premier League side Tottenham Hotspur.

Touré aspired to be a striker during his yout ...

, Ivorian footballer

*Seku Ouattara (Wattara) - a ''dioula'' warrior.

*Alassane Ouattara

Alassane Dramane Ouattara (; ; born 1 January 1942) is an Ivorian politician who has been President of Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire) since 2010. An economist by profession, Ouattara worked for the International Monetary Fund (IMF)Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire) since 2010.

*

"''Muslim Resurgence in Ghana Since 1950''"

''Journal of Christian-Muslim Relations'', Vol. 7. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster *

''Historical Context: Notes on the Arabic Literary Tradition of West Africa''

"''A History of African Societies to 1870''"

*Moshe Terdman, ''Project for the Research of Islamist Movements'' (PRISM): ''Islam in Africa Newsletter'', Vol. 2 No. 3

''Islam in Medieval Sudan''

islamawareness.net {{DEFAULTSORT:Dyula People Ethnic groups in Ivory Coast Ethnic groups in Ghana Ethnic groups in Guinea Ethnic groups in Mali Ethnic groups in Senegal Ethnic groups in Burkina Faso Mandé people West African people

Vincent Angban

Vincent Atchouailou de Paul Angban (born 2 February 1985) is an Ivorian former professional footballer who played as a goalkeeper.

Club career

Rio Sports / Sabé Sports

Born in Yamoussoukro, Angban began his career in Rio Sport d'Anyama and wa ...

* Yacouba Songné

* Mohamed Sylla

Notes

References

*Launey, Robert. "''Beyond the Stream: Islam & Society in a West African Town''",University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by faculty ...

, Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, 1992.

*Launay, Robert. "''Electronic Media & Islam Among the Dyula of Northern Cote de'Ivoire''". Journal Article; Africa, Vol. 67, 1997.

*Samwini, Nathan"''Muslim Resurgence in Ghana Since 1950''"

''Journal of Christian-Muslim Relations'', Vol. 7. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster *

Ivor Wilks

Professor Emeritus Ivor G. Wilks (19 July 1928 – 7 October 2014)"Professor Ivor Wilks is dead"

, Star ...

, "''The Juula & the Expansion of Islam into the Forest''", in N. Levtzion and R.L. Pouwels (eds.), ''The History of Islam in Africa'', Athens: , Star ...

Ohio University Press

Ohio University Press (OUP), founded in 1947, is the oldest and largest scholarly press in the state of Ohio. It is a department of Ohio University that publishes under its own name and the imprint Swallow Press.

History

The press publishes ap ...

, 2000

*Nehemia Levtzion and J.O. Voll (eds.), "''Eighteenth Century Renewal & Reform in Islam''", Syracuse: Syracuse University Press

Syracuse University Press, founded in 1943, is a university press that is part of Syracuse University. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

History

SUP was formed in August 1943 when president William P. Tolley prom ...

, 1987

*Andrea Brigaglia''Historical Context: Notes on the Arabic Literary Tradition of West Africa''

Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

*Elizabeth A. Isichei"''A History of African Societies to 1870''"

*Moshe Terdman, ''Project for the Research of Islamist Movements'' (PRISM): ''Islam in Africa Newsletter'', Vol. 2 No. 3

Herzliya, Israel

Herzliya ( ; he, הֶרְצְלִיָּה ; ar, هرتسليا, Hirtsiliyā) is an affluent city in the central coast of Israel, at the northern part of the Tel Aviv District, known for its robust start-up and entrepreneurial culture. In it h ...

. 2007''Islam in Medieval Sudan''

islamawareness.net {{DEFAULTSORT:Dyula People Ethnic groups in Ivory Coast Ethnic groups in Ghana Ethnic groups in Guinea Ethnic groups in Mali Ethnic groups in Senegal Ethnic groups in Burkina Faso Mandé people West African people