Dnipro is

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants.

It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital

Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

on the

Dnipro River, from which it takes its name. Dnipro is the

administrative centre

An administrative centre is a seat of regional administration or local government, or a county town, or the place where the central administration of a commune, is located.

In countries with French as the administrative language, such as Belgi ...

of

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

. It hosts the administration of Dnipro urban

hromada

In Ukraine, a hromada () is the main type of municipality and the third level Administrative divisions of Ukraine, local self-government in Ukraine. The current hromadas were established by the Cabinet of ministers of Ukraine, Government of Uk ...

.

Dnipro has a population of

Archeological evidence suggests the site of the present city was settled by

Cossack communities from at least 1524. Yekaterinoslav ("glory of Catherine")

was established by decree of the

Russian Empress Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

in 1787 as the administrative center of

Novorossiya

Novorossiya rus, Новороссия, Novorossiya, p=nəvɐˈrosʲːɪjə, a=Ru-Новороссия.ogg; , ; ; ; "New Russia". is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later becom ...

. From the end of the 19th century, the town attracted foreign capital and an international, multi-ethnic workforce exploiting

Kryvbas iron ore and

Donbas coal.

Renamed Dnipropetrovsk in 1926 after the Ukrainian

Communist Party leader

Grigory Petrovsky, it became a focus for the

Stalinist commitment to the rapid development of heavy industry. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, this included

nuclear,

arms

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

*Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

**Fi ...

, and

space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

industries whose strategic importance led to Dnipropetrovsk's designation as a

closed city.

Following the

Euromaidan

Euromaidan ( ; , , ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of Political demonstration, demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The p ...

events of 2014, the city politically shifted away from pro-Russian parties and figures towards those favoring closer ties with the European Union. As a result of

decommunization, the city was renamed Dnipro in 2016. Following the

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

in February 2022, Dnipro rapidly developed as a logistical hub for humanitarian aid and a reception point for people fleeing the various battle fronts.

Name

Current names

*

*

Former names

*Novyi Kodak 1645–1784

*Yekaterinoslav (also spelled Ekaterinoslav; ; ) 1784–1796

*Novorossiysk ( ; ) 1796–1802, briefly renamed during the reign of Catherine II's son, tsar

Paul I; however, the previous name was restored by tsar

Alexander I after his father's assassination

*Yekaterinoslav 1802–1918, called Catharinoslav on some nineteenth-century maps.

*Sicheslav ( ) 1918–1921 (unofficial name)

*Yekaterinoslav/Katerynoslav 1918–1926

*

Dnipropetrovsk ( ; ), also Dnipropetrovske () according to the

Kharkiv orthography 1926–2016. The word originates from ("

Dnieper River") + , after Soviet revolutionary

Grigory Petrovsky.

Name history

The original name of a

Ukrainian Cossack city on the territory of modern Dnipro was Novyi Kodak ( , New Kodak).

[New Kodak]

(26 March 2022) Also on the territory of Modern Dnipro, the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

founded Yekaterinoslav (''the glory of Catherine'').

This name was first mentioned in a report to

Azov Governor Vasily Chertkov to

Grigory Potemkin on 23 April 1776. He wrote "The provincial city called Yekaterinoslav should be the best convenience on the right side of the

Dnieper River near

Kaydak..." (Which referred to ). The construction was officially transferred to the right bank in a decree of

Empress of Russia Catherine II

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter III ...

of 23 January 1784.

In the 17th century the city was also known as Polovytsia.

In 1918, the

Central Council of Ukraine of the

Ukrainian People's Republic proposed to change the name of the city to ''Sicheslav''; however, this was never finalised.

In 1926 the city was renamed after

communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

leader

Grigory Petrovsky.

[Poroshenko signed the laws about decomunization]

Ukrayinska Pravda. 15 May 2015

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes

Interfax-Ukraine

Interfax-Ukraine () is a Ukrainian news agency. Founded in 1992, the company publishes in Ukrainian, Russian, English and German.

The company owns a 50-seat press centre.

The staff of the agency is 105 people (as of the end of February 2022)

...

. 15 May 20

Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

(14 April 2015)[ In some Anglophone media Dnipro was nicknamed the Rocket City during the ]Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

The 2015 law on decommunization required the city to be renamed.[ On 29 December 2015 the Dnipro City Council officially changed the reference of the city naming from referring to Petrovsky to being in honor of ]Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

, thus making the name consistent with the law without actually changing the name itself.

On 3 February 2016 a draft law was registered in the Verkhovna Rada

The Verkhovna Rada ( ; VR), officially the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, is the unicameralism, unicameral parliament of Ukraine. It consists of 450 Deputy (legislator), deputies presided over by a speaker. The Verkhovna Rada meets in the Verkhovn ...

(the Ukrainian parliament) to change the name of the city to ''Dnipro''. On 19 May 2016 the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill to officially rename the city (to ''Dnipro''). The resolution was approved by 247 out of the 344 MPs, with 16 opposing the measure.

Верховна Рада України (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine)

''Поіменне голосування про проект Постанови про перейменування міста Дніпропетровська Дніпропетровської області (No.3864) (Roll-call vote on the draft resolution on renaming of Dnipropetrovsk Dnipropetrovsk region No.3864)'', 19 May 2016.Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

.

History

Early history

Human settlements in current Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

date from the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

era.Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

stonecrafter's house has been excavated in one of Dnipro's city parks.Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

the area was settled by diverse tribes.Cimmerian

The Cimmerians were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranic Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into W ...

settlements during the Bronze Age have been found near today's Taras Shevchenko Park.Migration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

(300–800) nomadic tribes of the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was par ...

, Avars, Bulgarians

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, ...

, and Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common culture, language and history. They also have a notable presence in former parts of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

passed through the lands of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

region, they came into contact with local agricultural East Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert Huds ...

.Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus,.

* was the first East Slavs, East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical At ...

(882–1240).Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks, , Middle Turkic languages, Middle Turkic: , , , , , , ka, პაჭანიკი, , , ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Pečenezi, separator=/, Печенези, also known as Pecheneg Turks were a semi-nomadic Turkic peopl ...

, Tork people and Cumans

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cumania, Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Ru ...

.Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

conquest of Kievan Rus'.khanate

A khanate ( ) or khaganate refers to historic polity, polities ruled by a Khan (title), khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. Khanates were typically nomadic Mongol and Turkic peoples, Turkic or Tatars, Tatar societies located on the Eurasian Steppe, ...

Golden Horde.Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

.Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

of Ivan Sulyma.[Plokhy, Serhii, ''The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine'', pub Oxford University Press, 2001, , pages 26, 37, 40, 51, 60–1, 142, 245, and 268.] Rebuilt in 1645,Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and their Tartar vassals, drove out the encroaching Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

. Under the terms of the Russian withdrawal—the Treaty of the Pruth in 1711—the Kodak fortress was demolished.[day.kyiv.ua ''Above Kodak, this year the unique fortress marks its 375th anniversary''](_blank)

by Mykola Chaban, 2010.

In the mid-1730s, the fortress and Russians returned, living in an uneasy cohabitation with local cossacks.sloboda

A sloboda was a type of settlement in the history of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. The name is derived from the early Slavic word for 'freedom' and may be loosely translated as 'free settlement'. (or "free settlement") of ''Polovytsia'' located on the site of today's Central Terminal and the ''Ozyorka'' farmers market.[Establishment and development of the Dnipropetrovsk city (Виникнення і розвиток міста Дніпропетровськ)](_blank)

The History of Cities and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR.

In the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774)

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, the Zaporozhian cossacks allied with Empress Catherine II. No sooner had they assisted the Russians to victory than they faced an imperial ultimatum to disband their confederation. The liquidation of the Sich destroyed their political autonomy and saw the incorporation of their lands into the new governates of Novorossiya

Novorossiya rus, Новороссия, Novorossiya, p=nəvɐˈrosʲːɪjə, a=Ru-Новороссия.ogg; , ; ; ; "New Russia". is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later becom ...

. In 1784, Catherine ordered the foundation of new city, commonly referred to at the time as Katerynoslav.

Imperial city

Establishment of Catherine's city

The first written mention of a town in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

called Yekaterinoslav can be found in a report from Azov Governor Vasily Chertkov to Grigory Potemkin on 23 April 1776. He wrote "The provincial city called Yekaterinoslav should be the best convenience on the right side of the Dnieper River near Kaydak..." (referring to Novyi Kodak). In 1777, a town named Yekaterinoslav (''the glory of Catherine''),Samara

Samara, formerly known as Kuybyshev (1935–1991), is the largest city and administrative centre of Samara Oblast in Russia. The city is located at the confluence of the Volga and the Samara (Volga), Samara rivers, with a population of over 1.14 ...

and Kilchen rivers. The site was badly chosen – spring waters transformed the city into a bog.[S. S. Montefiore: Prince of Princes – The Life of Potemkin]

The territory of modern Dnipro, despite the modern-day city's size, still has not expanded to encompass the territory of (Chertkov's) Yekaterinoslav of 1776.Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

signed an Imperial Ukase directing that "the gubernatorial city under name of Yekaterinoslav be moved to the right bank of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

river near Kodak". The new city would serve Grigory Potemkin as a Viceregal seat for the combined Novorossiya and Azov Governorates.Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

of southern Russia'[Charles Wynn]

Workers, Strikes, and Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend in Late Imperial Russia, 1870–1905

– " he Empressand her favorite, Prince Grigorii Potemkin, the city's first governor-general and the de facto viceroy of southern Russia, had big plans for Ekaterinoslav. Potemkin envisioned Ekaterinoslav as the 'Athens of southern Russia' and as Russia's third capital – 'the centre of the administrative, economic, and cultural life of southern Russia.'"

In 1815 a government official described the town as "more like some Dutch ennonitecolony then a provincial administrative centre".

= Disputed year of foundation

=

Scholarship concerning the foundation of the city has been subject to political considerations and dispute.Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

, the date of the city's foundation was moved back from the visit Russian Empress Catherine II in 1787, to 1776.[Riding the currents](_blank)

The Ukrainian Week

''The Ukrainian Week'' (, ) is an illustrated weekly magazine and news outlet covering politics, economics and the arts and aimed at the socially engaged Ukrainian-language reader. It provides a range of analysis, opinion, interviews, feature p ...

(18 August 2017)

Following Ukrainian independence, local historians began to promote the idea of a town emerging in the 17th century from Cossack settlements, an approach aimed at promoting the city's Ukrainian identity.[''"Літописець Запорозької Січі – Минуло 150 років від дня народження Дмитра Яворницького", Ukraina Moloda, November 2011'', ]

Growth as an industrial centre

While into the late nineteenth century the principal business of the town remained the processing of agricultural raw materials,Novorossiya Governorate

Novorossiya Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Russian Empire, which existed in 1764–1783 and again in 1796–1802. It was created and governed according to the "Plan for the Colonization of New Russia ...

, the settlement was officially known as ''Novorossiysk.''pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

foundries in Krivoy Rog with Donbass coal crossed the Dnieper at Yekaterinoslav.[Message of Greeting from Rector](_blank)

, University official website Within twenty years the population had more than tripled, reaching 157,000 in 1904. The immigrants flowing into the city were mainly ethnic or cultural Russians and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, with the Ukrainian population remaining rural in this stage of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

.

The Jewish community and the 1905 pogrom

From 1792 Yekaterinoslav was within the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 1917 (''de facto'' until 1915) in which permanent settlement by Jews was allowed and beyond which the creation of new Jewish settlem ...

, the former Polish-Lithuanian territories in which Catherine and her successors enforced no limitation on the movement and residency of their Jewish subjects. Within less than a century, a largely Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

-speaking Jewish community of 40,000 constituted more than a third of the city's population, and contributed a considerable share of its business capital and industrial workforce.Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, the political life of the city was dominated by the revolutionary opposition (including the Jewish Workers Socialist Party and the Bund)World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.[Dnipropetrovsk region. Pragmatic area]

The Ukrainian Week

''The Ukrainian Week'' (, ) is an illustrated weekly magazine and news outlet covering politics, economics and the arts and aimed at the socially engaged Ukrainian-language reader. It provides a range of analysis, opinion, interviews, feature p ...

(8 May 2014)

The Soviet era

War and revolution

Directly following the Russian February Revolution, in the night of 3 March O.S (16 March N.S) to 4 March 1917 a provisional government was organised in Yekaterinoslav headed by the (since 1913) chairman of the provincial land administration .prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the Russian Provisional Government Georgy Lvov removed the governor and the vice-governor of Yekaterinoslav Governorate, temporarily handing these powers to Hesberg.Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s, significantly strengthening their positions.Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

declared Yekaterinoslav to be within the territory of the autonomous Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR).Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly () was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the February Revolution of 1917. It met for 13 hours, from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m., , whereupon it was dissolved by the Bolshevik-led All-Russian Central Ex ...

, the Bolsheviks secured just under 18 per cent of the vote in the Governorate, compared to 46 per cent for the Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionaries and their allies.Imperial German army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

entered the city. Five hundred remaining Bolshevik Red Guards were publicly executed.Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

saw the UPR replaced by the more pliant Ukrainian State or Hetmanate. On 18 May 1918 the Hetman of the Ukrainian State, Pavlo Skoropadskyi, ordered the previously nationalized enterprises returned to their former owners, and with the assistance of Austro-Hungarian troops the new authorities suppressed labor protest.[ (page 77)] and the Bolsheviks, who reorganised as the Red Army, finally secured the city on 30 December 1919.

Stalin-era industrialisation

In late May 1920 the food supply to Yekaterinoslav deteriorated, resulting in a wave of strikes.

In late May 1920 the food supply to Yekaterinoslav deteriorated, resulting in a wave of strikes.Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, a constituent republic of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. In 1922 the Soviet government

The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was the executive and administrative organ of the highest body of state authority, the All-Union Supreme Soviet. It was formed on 30 December 1922 and abolished on 26 December 199 ...

ordered that "all nationalized enterprises with names related to the Company or the Surname of the old owners must be renamed in memory of revolutionary events, in memory of the international, all-Russian or local leaders of the proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialist ...

."Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet () was the standing body of the highest organ of state power, highest body of state authority in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).The Presidium of the Soviet Union is, in short, the legislativ ...

.[Ukraine tears down controversial statue](_blank)

by Rostyslav Khotin, BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

(27 November 2009)

Same article on UNIAN.

/ref>1930s

File:1930s decade montage.png, From left, clockwise: Dorothea Lange's photo of the homeless Florence Owens Thompson, Florence Thompson shows the effects of the Great Depression; due to extreme drought conditions, farms across the south-central Uni ...

dozens of streets, alleys, driveways, squares and parks continued to be renamed in the city, this continued in the 1940s

File:1940s decade montage.png, Above title bar: events during World War II (1939–1945): From left to right: Troops in an LCVP landing craft approaching Omaha Beach on Normandy landings, D-Day; Adolf Hitler visits Paris, soon after the Battle of ...

and in subsequent years.Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

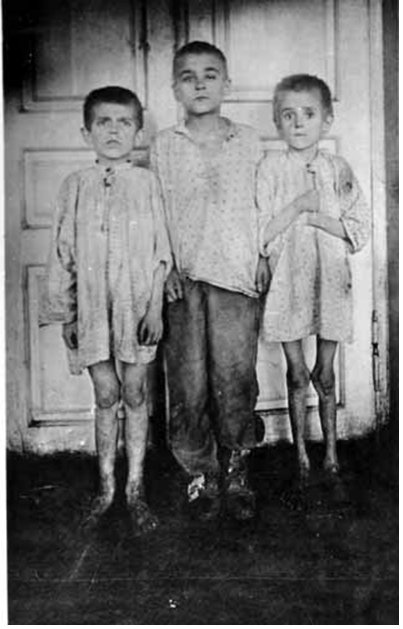

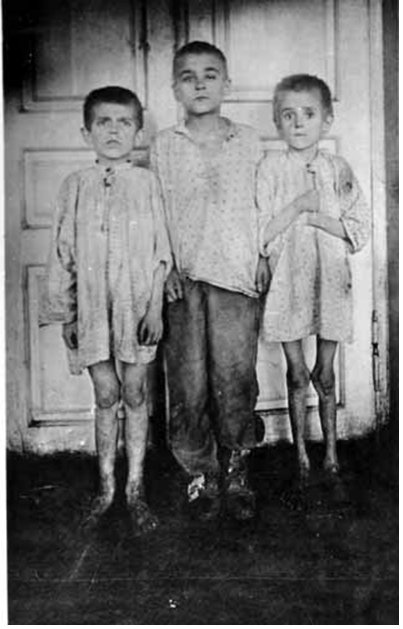

in the years 1932–33 lost 3.5 to 9.8 million people,Interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

grew rapidly. 368,000 people lived in Dnipropetrovsk in 1932. In the 1939 Soviet Census, this number had grown to more than half a million (500,662 people).Communist party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU or KPU) is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 and claimed to be the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine, which had been banned in 1991. In 2002 it held a "unifi ...

organized special courses in Ukrainian studies.1930s

File:1930s decade montage.png, From left, clockwise: Dorothea Lange's photo of the homeless Florence Owens Thompson, Florence Thompson shows the effects of the Great Depression; due to extreme drought conditions, farms across the south-central Uni ...

had eradicate illiteracy in the city.Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, following the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, also reached Dnipropetrovsk.NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

arrested 182 " Trotskyists".

Nazi occupation

Dnipropetrovsk was under Nazi German

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

occupation from 26 August 1941Rzeszów

Rzeszów ( , ) is the largest city in southeastern Poland. It is located on both sides of the Wisłok River in the heartland of the Sandomierz Basin. Rzeszów is the capital of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship and the county seat, seat of Rzeszów C ...

in German-occupied Poland, at which the occupiers are estimated to have killed upwards of 30,000 Soviet POWs, and briefly also the Stalag 310 and Stalag 387 camps.

In November 1941 Dnipropetrovsk's population was 233,000. In March 1942 this number had fallen to 178,000.

Post-war closed city

As early as July 1944, the State Committee of Defence in Moscow decided to build a large military machine-building factory in Dnipropetrovsk on the location of the pre-war aircraft plant. In December 1945, thousands of German prisoners of war began construction and built the first sections and shops in the new factory. This was the foundation of the Dnipropetrovsk Automobile Factory. In 1954 the administration of this automobile factory opened a secret design office, designated OKB-586

The ''Pivdenne'' Design Office (), located in Dnipro, Ukraine, is a designer of satellites and rockets, and formerly of Soviet Union, Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), established by Mikhail Yangel. During the Soviet era, the bu ...

, to construct military missile

A missile is an airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight aided usually by a propellant, jet engine or rocket motor.

Historically, 'missile' referred to any projectile that is thrown, shot or propelled towards a target; this ...

s and rocket engines.Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

boasted in 1960 that it was producing rockets "like sausages" ).perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

, that Dnipropetrovsk was opened to international visitors and civil restrictions were lifted.

The population of Dnipropetrovsk increased from 259,000 people in 1945 to 845,200 in 1965.[''New York Times'', 20 June 1990 ''Evolution in Europe; Soviet Troops Kill an Inmate During Riot in Ukrainian Jail''](_blank)

This stated that TASS had issued a statement saying that there had been a riot by 2,000 inmates in a prison in Dnipropetrovsk. The riot broke out on Thursday 14 June 1990, and was quelled by Soviet troops on Friday 15 June 1990, killing one prisoner and wounding another.

Dissent and youth rebellion

In 1959 17.4% of Dnipropetrovsk students were taught in Ukrainian language schools and 82.6% in Russian language schools. 58% of the city's inhabitants self-identified as Ukrainians.

In 1959 17.4% of Dnipropetrovsk students were taught in Ukrainian language schools and 82.6% in Russian language schools. 58% of the city's inhabitants self-identified as Ukrainians.Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

26.8% of pupils studied in Ukrainian and 73.1% in Russian while 66% of Kyiv residents considered themselves Ukrainian, in Kharkiv these numbers were 4.9%, 95.1% and 49%. In Odesa these numbers were 8.1%, 91.9% and 40%.[History of Ukraine. Standard level. Grade 11. Strukevich § 9. The state of culture during the period of de-Stalinization]

History , Your library (2009–2022)

As in the overall Ukrainian SSR, Dnipropetrovsk saw an influx of young immigrants from rural Ukraine.Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

saw the highest inflow of rural youth of all Ukraine.[The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music and Social Class](_blank)

ed. Ian Peddie, New York / London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, , page 318 + 319

The "Dnipropetrovsk Mafia"

Reflecting Dnipropetrovsk's special strategic importance for the entire Soviet Union, party Cadre (politics), cadres from the "rocket city" played an outsized role not only in republican leadership in Kyiv, but also in the Union leadership in Moscow. During Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

rose rapidly within the ranks of the local ''nomenklatura,''Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and call a halt to further reform.

Independent Ukraine

In a 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum, national referendum on 1 December 1991, 90.36% of Dnipropetrovsk's voters approved the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, declaration of independence that had been made by the Verkhovna Rada, Ukrainian parliament on 24 August.[East Journal](_blank)

29 April 2012

Euromaidan

On 26 January 2014, 3,000 anti-Viktor Yanukovych (Ukrainian President) and pro-Euromaidan

Euromaidan ( ; , , ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of Political demonstration, demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The p ...

activists attempted but failed to capture the Local government in Ukraine, Regional State Administration building.[Ukraine protests 'spread' into Russia-influenced east](_blank)

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

(26 January 2014)[Residents Dnipropetrovsk forced mayor to withdraw from the Party of Regions]

, Espreso TV (22 February 2014)

Dnipropetrovsk mayor left the PR 'for peace in the city'

, NEWSru.ua (22 February 2014)

In Dnepropetrovsk Lenin Square was renamed Heroes Square, the Mayor released from PR

Ukrayinska Pravda (22 February 2014)

Simultaneously the Dnipropetrovsk City Council vowed to support "the preservation of Ukraine as a single and indivisible state", although some members had called for separatism and for federalization of Ukraine.Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, 22 February 2014, Yanukovych left Ukraine and went into Russian exile.[Ukraine crisis timeline](_blank)

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

2014 to 2022

Dnipropetrovsk remained relatively quiet during the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine, with pro-Russian Federation protestors outnumbered by those opposing outside intervention.Euromaidan

Euromaidan ( ; , , ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of Political demonstration, demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The p ...

. To comply with the decommunization in Ukraine, 2015 decommunization law the city was renamed ''Dnipro'' in May 2016, after the river that flows through the city.

To comply with the decommunization in Ukraine, 2015 decommunization law the city was renamed ''Dnipro'' in May 2016, after the river that flows through the city.

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, and with developing military fronts near Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

and to the Northern front of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, north, Eastern front of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, east and Southern front of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, south, Dnipro has become a logistical hub for humanitarian aid and a reception point for people fleeing the war. Roughly equidistant from the war's major theatres in the Eastern Ukraine campaign, east and the Southern Ukraine campaign, south, the city's location is proving critical for supplying the Ukrainian defence effort. At the same time, its control of a Dnieper River crossing and the opportunity it would provide to cut off Ukrainian forces in the Donbas makes the city a high-value target for the Russians.

Government and politics

Government

The City of Dnipro is governed by the Dnipro City Council. It is a city municipality that is designated as a separate district within its oblast.

Administratively, the city is divided into Urban districts of Ukraine, urban districts. Presently, there are 8 of them. Aviatorske, a rural settlement located near the Dnipro International Airport, is also a part of Dnipro urban hromada.

The City Council Assembly makes up the administration's legislative branch, thus effectively making it a city 'parliament' or rada. The municipal council is made up of 12 elected members, who are each elected to represent a certain district of the city for a four-year term. The council has 29 standing commissions which play an important role in the oversight of the city and its merchants.

Until 18 July 2020, Dnipro was incorporated as a city of regional significance (Ukraine), city of oblast significance, the centre of Dnipro Municipality and extraterritorial administrative centre of Dnipro Raion. The municipality was abolished in July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast to seven. The area of Dnipro Municipality was merged into Dnipro Raion.

Dnipro is also the seat of the oblast's local administration controlled by the Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast Council, Rada. The Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast is appointed by the President of Ukraine.

Subdivisions

Five of the eight urban districts were renamed late November 2015 to comply with Decommunization in Ukraine, decommunization laws.

Five of the eight urban districts were renamed late November 2015 to comply with Decommunization in Ukraine, decommunization laws.[Street signs were Dnipropetrovsk nedekomunizovanymy]

Radio Svoboda (2 December 2015)

Politics

In the first decades of Ukrainian independence the city's voters generally favoured the proponents of continued close ties to Russia: in the 1990s the Communist Party of Ukraine, and in the new century, the Party of Regions.[Ukraine's political parties at the start of the election campaign](_blank)

Centre for Eastern Studies (17 September 2014) After the 2014 events of Euromaidan

Euromaidan ( ; , , ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of Political demonstration, demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The p ...

, which included demonstrations and clashes in the central city, the Party of Regions ceded influence to those parties and independents calling for Ukraine–European Union relations, closer ties to the European Union.

As in Soviet Ukraine, Dnipropetrovsk was disproportionately represented among political leaders in Kyiv. With Viktor Yushchenko, Tymoshenko co-led the Orange Revolution which annulled the declared victory of Viktor Yanukovych in the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, 2004 presidential election, and under President Yuschenko served as prime minister from 24 January to 8 September 2005, and again from 18 December 2007 to 4 March 2010. Yanukovych narrowly defeated Tymoshenko in the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, 2010 presidential election, taking 41.7 per cent of the vote in the Dnipropetrovsk region. The candidates accused one another of vote rigging.

In the October 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election Yanukovych's Party of Regions, which promoted itself as the champion of the language rights and industrial interests of largely Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine, won 35.8 per cent of the vote in the Dnipropetrovsk region, compared to 18.4 per cent for Tymoshenko's Fatherland Party (Ukraine), Fatherland Party and 19.4 per cent for the Communist Party of Ukraine, Communists. Tymoshenko mounted a hunger strike to once again protest election irregularities.

On 2 March 2014, following the Revolution of Dignity, removal of Yanukovich as President, acting President Oleksandr Turchynov appointed Ihor Kolomoyskyi Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Governor of

With Viktor Yushchenko, Tymoshenko co-led the Orange Revolution which annulled the declared victory of Viktor Yanukovych in the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, 2004 presidential election, and under President Yuschenko served as prime minister from 24 January to 8 September 2005, and again from 18 December 2007 to 4 March 2010. Yanukovych narrowly defeated Tymoshenko in the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, 2010 presidential election, taking 41.7 per cent of the vote in the Dnipropetrovsk region. The candidates accused one another of vote rigging.

In the October 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election Yanukovych's Party of Regions, which promoted itself as the champion of the language rights and industrial interests of largely Russian-speaking eastern Ukraine, won 35.8 per cent of the vote in the Dnipropetrovsk region, compared to 18.4 per cent for Tymoshenko's Fatherland Party (Ukraine), Fatherland Party and 19.4 per cent for the Communist Party of Ukraine, Communists. Tymoshenko mounted a hunger strike to once again protest election irregularities.

On 2 March 2014, following the Revolution of Dignity, removal of Yanukovich as President, acting President Oleksandr Turchynov appointed Ihor Kolomoyskyi Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

. Kolomoyskyi initially dismissed suggestions of War in Donbas (2014–2022), Russian-backed separatism in Dnipropetrovsk, but then took vigorous measures. He posted bounties for the capture of Russian-backed militants and the surrender of weapons; drafted thousands of Privat Group employees as auxiliary police officers; and is said to have provided substantial funds to create the Dnipro Battalion,[The Town Determined to Stop Putin](_blank)

The Daily Beast (12 June 2014)[Ukraine's Secret Weapon: Feisty Oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky](_blank)

The Wall Street Journal (27 June 2014) and to support the Aidar Battalion, Aidar, Azov Battalion, Azov, and Donbas Battalion, Donbas Territorial defense battalions (Ukraine), volunteer battalions.[Two Russia-friendly parties join forces for presidential election](_blank)

Kyiv Post (9 November 2018)

On 25 March 2015, following a struggle with Kolomoyskyi for control the state-owned oil pipeline operator, President Poroshenko replaced Kolomoyskyi as governor with Valentyn Reznichenko.[Borys Filatov becomes Dnipropetrovsk mayor – election commission](_blank)

Ukrinform (18 November 2015)

In the March–April 2019 Ukrainian presidential election Dnipro voted overwhelmingly voted for the successful candidate, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who advocated membership of European Union. In the parliamentary election in October, his Servant of the People party swept the board, winning each of Dnipro's five single-mandate parliamentary constituencies.

By the time of the October 2020 Ukrainian local elections#Dnipro, 2020 Ukrainian local elections, support for Zelenskyy's party had collapsed: it won just 8.7 per cent of the vote for the Dnipro City Council. The Euromaidan trajectory was represented instead by Filatov's Proposition (party), Proposition (the "Party of Mayors"),

Geography

The city is built mainly upon both banks of the Dnieper, at its confluence with the Samara River (Dnieper), Samara River. In the loop of a major meander, the Dnieper changes its course from the north west to continue southerly and later south-westerly through Ukraine, ultimately passing Kherson, where it finally flows into the Black Sea.

Nowadays both the north and south banks play home to a range of industrial enterprises and manufacturing plants. The airport is located about south-east of the city.

The centre of the city is constructed on the right bank which is part of the Dnieper Upland, while the left bank is part of the Dnieper Lowland. The old town is situated atop a hill that is formed as a result of the river's change of course to the south. The change of river's direction is caused by its proximity to the Azov Upland located southeast of the city.

One of the city's streets, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, links the two major architectural ensembles of the city and constitutes an important thoroughfare through the centre, which along with various suburban radial road systems, provides some of the area's most vital transport links for both suburban and inter-urban travel.

The city is built mainly upon both banks of the Dnieper, at its confluence with the Samara River (Dnieper), Samara River. In the loop of a major meander, the Dnieper changes its course from the north west to continue southerly and later south-westerly through Ukraine, ultimately passing Kherson, where it finally flows into the Black Sea.

Nowadays both the north and south banks play home to a range of industrial enterprises and manufacturing plants. The airport is located about south-east of the city.

The centre of the city is constructed on the right bank which is part of the Dnieper Upland, while the left bank is part of the Dnieper Lowland. The old town is situated atop a hill that is formed as a result of the river's change of course to the south. The change of river's direction is caused by its proximity to the Azov Upland located southeast of the city.

One of the city's streets, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt, links the two major architectural ensembles of the city and constitutes an important thoroughfare through the centre, which along with various suburban radial road systems, provides some of the area's most vital transport links for both suburban and inter-urban travel.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Köppen–Geiger climate classification system, Dnipro has a humid continental climate (''Dfa'').[www.mongabay.com Russia – Geography]

states: "Since 1990 Russian experts have added to the list the following less spectacular but equally threatening environmental crises: the Dnepropetrovsk-Donets and Kuznets coal-mining and metallurgical centres, which have severely polluted air and water and vast areas of decimated landscape;..." Though exactly where in Dnipropetrovsk these areas might be found is not stated.[

]

Cityscape

Dnipro is a primarily industrial city of around one million people. It has developed into a large urban centre over the past few centuries to become, today, Ukraine's fourth-largest city after

Dnipro is a primarily industrial city of around one million people. It has developed into a large urban centre over the past few centuries to become, today, Ukraine's fourth-largest city after Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Kharkiv and Odessa, Odesa. Stalinist architecture (monumental soviet classicism) dominates in the city centre.

Immediately after its foundation Yekaterinoslav, began to develop exclusively on the right bank of the Dnieper River. At first the city developed radially from the central point provided by the Transfiguration Cathedral, completed in 1835.Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

with the October Revolution in 1917, the city did not change much in appearance. The predominant architectural style remained neo-classicism. Notable buildings built in the era before 1917 include the main building of the Dnipro Polytechnic, which was built in 1899–1901, the art-nouveau inspired building of the city's former Duma (parliament), the Dnipropetrovsk National Historical Museum, and the Élie Metchnikoff, Mechnikov Regional Hospital. Other buildings of the era that did not fit the typical architectural style of the time in Dnipropetrovsk include, the Ukrainian-influenced Grand Hotel Ukraine, the Russian revivalist style railway station (since reconstructed), and the Art Nouveau, art-nouveau Astoriya building on Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt.

Once Yekaterinoslav became part of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, officially in 1922), and became Dnipropetrovsk in 1926,Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

that stood in front of the Mining Institute was replaced with one of Russian academic Mikhail Lomonosov.Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

, a function it fulfils to this day. Other buildings, such as the Potemkin Palace were given over to "the proletariat" (the working man), in this case as the students' union of the Oles Honchar Dnipro National University.

After the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the appointment of Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the industrialisation of Dnipropetrovsk became even more profound, with the PA Pivdenmash, Southern (Yuzhne) Missile and Rocket factory being set up in the city. However, this was not the only development and many other factories, especially metallurgical and heavy-manufacturing plants, were set up in the city.[ The low-rise tenant houses of the Khrushchev era (Khrushchyovkas) gave way to the construction of high-rise prefabricated apartment blocks (similar to German Plattenbaus). In 1976, in line with the city's 1926 renaming, a large monumental statue of Grigoriy Petrovsky was placed on the square in front of the Dnipro railway station, city's railway station.][In East Ukraine, fear of Putin, anger at Kiev](_blank)

br

/ref>

Demographics

The population of the city is about 1 million people. In 2011, the average age of the city's resident population was 40 years. The number of males declined slightly more than the number of females. The natural population growth in Dnipro is slightly higher than growth in Ukraine in general.

Between 1923 and 1933 the Ukrainian proportion of the population of the city increased from 16% to 48%. Ukrainization, This was part of a national trend.[Volodymyr Kubiyovych; Zenon Kuzelia, Енциклопедія українознавства ''(Encyclopedia of Ukrainian studies)'', 3-volumes, Kyiv, 1994, ]

In a survey in June–July 2017, 9% of residents said that they spoke Ukrainian at home, 63% spoke Russian, and 25% spoke Ukrainian and Russian equally.[

The same survey reported the following results for the religion of adult residents.][

*49% Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate

*6% Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate

*7% atheist

*1% belong to other religions

*28% believe in God, but do not belong to any religion

*5% found it difficult to answer

According to a survey conducted by the International Republican Institute in April–May 2023, 27% of the city's population spoke Ukrainian at home, and 66% spoke Russian.

]

Economy

Dnipro is a major industrial centre of Ukraine. Entrepreneur Ihor Kolomoyskyi's Privat Group, a global business group, is based in the city and grouped around the Privatbank. Privat Group controls thousands of companies of virtually every industry in Ukraine, European Union, Georgia, Ghana, Russia, Romania, United States and other countries. Steel, oil & gas, chemical and energy are sectors of the group's prime influence and expertise. Privat Group is in business conflict with the Interpipe, also based in Dnipro area. The influential metallurgical mill company founded and mostly owned by the local business oligarch Viktor Pinchuk.

Another company headquartered in Dnipro is ATB-Market. This company owns the largest national network of retail shops.

None of the group's capital is publicly traded on the stock exchange. Group's founding owners are natives of Dnipro and made their entire career here. Privatbank, the core of the group, is the largest commercial bank in Ukraine. In March 2014 was named by the American review magazine ''Global Finance'' as "the Best Bank in Ukraine for 2014" while British magazine ''The Banker'' in November 2013 named again the same bank as "the Bank of the year 2013 in Ukraine".

In 2018 a private Texas-based aerospace firm Firefly Aerospace opened a Research and Development (R&D) centre in Dnipro to develop small and medium-sized launch vehicles for commercial launches to orbit.

Entrepreneur Ihor Kolomoyskyi's Privat Group, a global business group, is based in the city and grouped around the Privatbank. Privat Group controls thousands of companies of virtually every industry in Ukraine, European Union, Georgia, Ghana, Russia, Romania, United States and other countries. Steel, oil & gas, chemical and energy are sectors of the group's prime influence and expertise. Privat Group is in business conflict with the Interpipe, also based in Dnipro area. The influential metallurgical mill company founded and mostly owned by the local business oligarch Viktor Pinchuk.

Another company headquartered in Dnipro is ATB-Market. This company owns the largest national network of retail shops.

None of the group's capital is publicly traded on the stock exchange. Group's founding owners are natives of Dnipro and made their entire career here. Privatbank, the core of the group, is the largest commercial bank in Ukraine. In March 2014 was named by the American review magazine ''Global Finance'' as "the Best Bank in Ukraine for 2014" while British magazine ''The Banker'' in November 2013 named again the same bank as "the Bank of the year 2013 in Ukraine".

In 2018 a private Texas-based aerospace firm Firefly Aerospace opened a Research and Development (R&D) centre in Dnipro to develop small and medium-sized launch vehicles for commercial launches to orbit.

Transport

Local transportation

The main forms of public transport used in Dnipro are trams, buses and electric Trolleybus, trolley buses. In addition to this there are a large number of taxi firms operating in the city, and many residents have private cars.

The city's municipal roads also suffer from the same funding problems as the trams, with many of them in a very poor technical state. It is not uncommon to find very large potholes and crumbling surfaces on many of Dnipro's smaller roads. Major roads and highways are of better quality. In the early 2010s the situation was improving, with a number of new used trams bought from the German cities of Dresden and Magdeburg, and a number of roads, including Otto Schmidt, Schmidt Street (now Stepan Bandera Street Dnipro also has a Dnipro Metro, metro system, opened in 1995, which consists of one line and 6 stations. The 1980 official plans for four different lines were never made reality.

Dnipro also has a Dnipro Metro, metro system, opened in 1995, which consists of one line and 6 stations. The 1980 official plans for four different lines were never made reality.

Suburban transportation

Dnipro has some highways crossing through the city. The most popular routes are from

Dnipro has some highways crossing through the city. The most popular routes are from Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Donetsk, Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia. Transit through the city is also available. the city is also seeing construction of a southern urban bypass, which will allow automobile traffic to proceed around the city centre. This is expected to both improve air quality and reduce transport issues from heavy freight lorries that pass through the city centre.

The largest bus station in eastern Ukraine is located in Dnipro, from where bus routes are available to all over the country, including some international routes to Poland, Germany, Moldova and Turkey. It is located near the city's central railway station. Since the start of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine Ukraine's border crossings with Russia and Belarus are closed to regular traffic.

Rail

The city is a large railway junction, with many daily trains running to and from Eastern Europe and on domestic routes within Ukraine.

There are two railway terminals, Dnipro Railway station, Dnipro Holovnyi (main station) and Dnipro Lotsmanska (south station).

Two express passenger services run each day between Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

and Dnipro under the name 'Capital Express'. Other daytime services include suburban trains to towns and villages in the surrounding Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast (), is an administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in simultaneously southern, eastern and central Ukraine, the most important industrial region of the country. It was created on February 27, 1932. Dnipropetro ...

. Most long-distance trains tend to run at night to reduce the amount of daytime hours spent travelling by each passenger.

Domestic connections exist between Dnipro and Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Lviv, Odesa, Ivano-Frankivsk, Truskavets, Kharkiv and many other smaller Ukrainian cities, while international destinations include, among others the Bulgarian seaside resort of Varna, Bulgaria, Varna. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine all railway connection between Ukraine and Belarus were axed.

Aviation

The city is served by Dnipro International Airport and is connected to European and Middle Eastern cities with daily flights. It is located southeast from the city centre. 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, A Russian attack on 10 April 2022 completely destroyed the airport and the infrastructure nearby.

Water transportation

The city has a river port located on the left bank of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

. There is also a railway freight station.

Education

There are 163 educational institutions among them schools, gymnasiums and boarding schools. For children of pre-school age there are 174 institutions, also a lot of out-of -school institutions such as centre of out-of-school work. Eighty-seven institutions that are recognized on all Ukrainian and regional levels.

In a survey in June–July 2017, adult respondents reported the following educational levels:

There are 163 educational institutions among them schools, gymnasiums and boarding schools. For children of pre-school age there are 174 institutions, also a lot of out-of -school institutions such as centre of out-of-school work. Eighty-seven institutions that are recognized on all Ukrainian and regional levels.

In a survey in June–July 2017, adult respondents reported the following educational levels:[

*1% primary or incomplete secondary education

*13% general secondary education

*46% vocational secondary education

*39% university education (including incomplete university education)

In 2006 Dnipropetrovsk hosted the All-Ukrainian Olympiad in Information Technology; in 2008, that for Mathematics, and in 2009 the semi-final of the All-Ukrainian Olympiad in Programming for the Eastern Region. In the same year as the latter took place, the youth group 'Eksperiment', an organisation promoting increased cultural awareness amongst Ukrainians, was founded in the city.

]

Higher education

Dnipro is a major educational centre in Ukraine and is home to two of Ukraine's top-ten universities; the Oles Honchar Dnipro National University and Dnipro Polytechnic, Dnipro Polytechnic National Technical University.

The system of high education institutions connects 38 institutions in Dnipro, among them 14 of IV and ІІІ levels of accreditation, and 22 of І and ІІ levels of accreditation. In year 2012 National Mining Institute was on the 7th and National University named after O. Honchar was on the 9th place among the best high education institutions in "TOP-200 Ukraine" list.

The list below is a list of all current state-organised higher educational institutions (not included are non-independent subdivisions of other universities not based in Dnipro).

In the 21st century annually around 55,000 students studied in Dnipro, a significant number of whom students from abroad.

Culture

Attractions

Dnipro has a variety of theatres (Dnipro Academic Drama and Comedy Theatre, Taras Shevchenko Dnipro Academic Ukrainian Music and Drama Theatre and Dnipro Opera and Ballet Theatre), a circus (Dnipro State Circus) and several museums (Dmytro Yavornytsky National Historical Museum of Dnipropetrovsk, Dmytro Yavornytsky National Historical Museum, Diorama "Battle of the Dnieper" and Dnipro Art Museum). There are also several restaurants, beaches and parks ( Taras Shevchenko Park and Sevastopol Park).

The major streets of the city were renamed in honour of Marxism–Leninism, Marxist heroes during the Soviet Union, Soviet era.Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

in 1787.

Religion

Ludwig Charlemagne, Ludwig Charlemagne-Bode and Pietro Visconti designed and erected the 19th century Holy Trinity Cathedral, Dnipro, Holy Trinity Cathedral in Dnipro, which is an Eastern Orthodox cathedral of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), UOC of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Sports

FC Dnipro is the most successful association football, football club of the city.

Notable people

* Peter Arshinov (1886–1937) – Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and intellectual, chronicled the history of the Makhnovshchina, a stateless anarchist society in Ukraine.

* Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) – founder of Theosophical Society.

* Oles Honchar (1918–1995) – Ukraine, Ukrainian writer and public figure and member of the Verkhovna Rada, Ukrainian parliament.

* Oleksandr Turchynov (born 1964) – Former Secretary of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine.

* Gennadiy Bogolyubov (born 1961/1962) – Ukrainian-Cypriot-Israeli billionaire businessman, Privat Group.

* Valentyn Reznichenko (born 1972) – The Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast 2020–2023.

* Borys Filatov (born 1972) – The current mayor of Dnipro.

* Yuriy Tkach (born 1983) Ukrainian comedian and actor.

* Kyrylo Tymoshenko (born 1989) Ukrainian politician who served as deputy Office of the President of Ukraine, Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine 2019–2023.

* Viktor Chebrikov (1923–1999) – head of the KGB 1982–1988.

* Dmytro Derevytskyy (born 1973) – Ukrainian entrepreneur

* Katherine Esau (1898–1997) German-American botanist.

* Vsevolod Garshin (1855–1888) – Russian author of short stories.

* Helen Gerardia (1903–1988) – American painter.

* Peter Arshinov (1886–1937) – Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and intellectual, chronicled the history of the Makhnovshchina, a stateless anarchist society in Ukraine.

* Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) – founder of Theosophical Society.

* Oles Honchar (1918–1995) – Ukraine, Ukrainian writer and public figure and member of the Verkhovna Rada, Ukrainian parliament.

* Oleksandr Turchynov (born 1964) – Former Secretary of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine.

* Gennadiy Bogolyubov (born 1961/1962) – Ukrainian-Cypriot-Israeli billionaire businessman, Privat Group.

* Valentyn Reznichenko (born 1972) – The Governor of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast 2020–2023.

* Borys Filatov (born 1972) – The current mayor of Dnipro.

* Yuriy Tkach (born 1983) Ukrainian comedian and actor.

* Kyrylo Tymoshenko (born 1989) Ukrainian politician who served as deputy Office of the President of Ukraine, Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine 2019–2023.

* Viktor Chebrikov (1923–1999) – head of the KGB 1982–1988.

* Dmytro Derevytskyy (born 1973) – Ukrainian entrepreneur

* Katherine Esau (1898–1997) German-American botanist.

* Vsevolod Garshin (1855–1888) – Russian author of short stories.

* Helen Gerardia (1903–1988) – American painter.

Sport

* Oksana Baiul (born 1977) – 1994 Winter Olympics figure skating gold medalist

* Anatoliy Demyanenko (born 1959) – Ukrainian football coach and former football defender.

* Artem Dolgopyat (born 1997) – Israeli artistic gymnast (Olympic medalist, second in world championships)

* Marharyta Dorozhon (born 1987) – Ukrainian/Israeli Olympic javelin thrower

* Kyrylo Fesenko (born 1986) – NBA basketball player

* Inessa Kravets (born 1966) – long jumper and triple jumper

* Yaroslava Mahuchikh (born 2001) – high jumper

* Igor Olshansky (born 1982) – NFL defensive tackle

* Olesya Povh (born 1987) – Olympic bronze medalist runner

* Oleh Protasov (born 1964) – former Ukrainian footballer

* Inna Ryzhykh (born 1985) – professional triathlete

* Adel Tankova (born 2000) – Ukrainian-born Israeli Olympic figure skater

* Oleg Tverdokhleb (1969–1995) – athlete, 400-metre hurdles

* Tatiana Volosozhar (born 1986) – figure skating Olympic gold medalist, 2014 Winter Olympic Games, 2014

Twin towns – sister cities

Dnipro is Sister city, twinned with:

Friendship cooperation cities

Dnipro also cooperates with:

See also

* Dnepropetrovsk maniacs

* Golden Rose Synagogue, Dnipro

Notes

References

Sources

*

* Михаил Александрович Шатров (Штейн). Город на трёх холмах. – Днепропетровск: Промiнь, 1969. (in Russian)

* Алексей Николаевич Толстой. Хождение по мукам. – М.: Художественная литература, 1976. (in Russian)

* Дмитрий Яворницкий. История города Екатеринослава. – Днепропетровск: Сiч, 1996. (in Russian)

* Справочник "Освобождение городов: Справочник по освобождению городов в период Великой Отечественной войны 1941—1945" / М. Л. Дударенко, Ю. Г. Перечнев, В. Т. Елисеев и др. М.: Воениздат, 1985. 598 с. (in Russian)

* Описание населенных мест Екатеринославской губернии на 1-е января 1925 г. – Екатеринослав: Типо-Литография Екатерининской ж.д., 1925. – 635 с. (in Russian)

*

*

External links

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

{{Authority control

Dnipro,

Cities in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

Yekaterinoslavsky Uyezd

Former closed cities

Populated places established in 1776

Cities of regional significance in Ukraine

1776 establishments in the Russian Empire

Populated places established in the Russian Empire

Populated places on the Dnieper in Ukraine

Oblast centers in Ukraine

In late May 1920 the food supply to Yekaterinoslav deteriorated, resulting in a wave of strikes. In June 1920 Soviet authorities quelled one such protest by arresting 200 railway workers, of which 51 were sentenced to immediate execution.

In 1922 the region was incorporated into the

In late May 1920 the food supply to Yekaterinoslav deteriorated, resulting in a wave of strikes. In June 1920 Soviet authorities quelled one such protest by arresting 200 railway workers, of which 51 were sentenced to immediate execution.

In 1922 the region was incorporated into the  In 1959 17.4% of Dnipropetrovsk students were taught in Ukrainian language schools and 82.6% in Russian language schools. 58% of the city's inhabitants self-identified as Ukrainians. Compared with the other 3 biggest cities of Ukraine Dnipropetrovsk had a rather large share of education conducted in Ukrainian. In