Druids United F on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient

The Greco-Roman and the vernacular Irish sources agree that the druids played an important part in pagan Celtic society. In his description,

The Greco-Roman and the vernacular Irish sources agree that the druids played an important part in pagan Celtic society. In his description,

Greek and Roman writers frequently made reference to the druids as practitioners of

Greek and Roman writers frequently made reference to the druids as practitioners of

"The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn mac Cumhaill"

. From maryjones.us. Retrieved July 22, 2008. daughter of the druid

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. While they were reported to have been literate, they are believed to have been prevented by doctrine from recording their knowledge in written form. Their beliefs and practices are attested in some detail by their contemporaries from other cultures, such as the Romans and the Greeks.

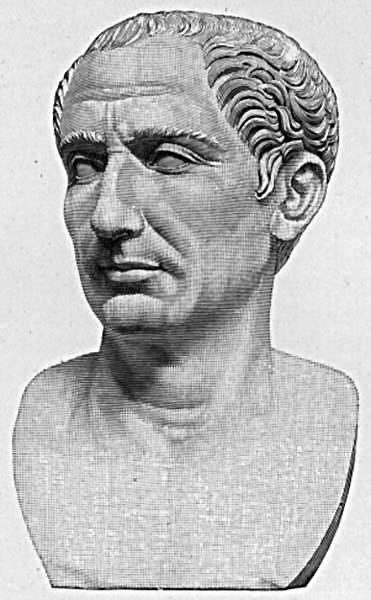

The earliest known references to the druids date to the 4th century BCE. The oldest detailed description comes from Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

's ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico

''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' (; en, Commentaries on the Gallic War, italic=yes), also ''Bellum Gallicum'' ( en, Gallic War, italic=yes), is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Ca ...

'' (50s BCE). They were described by other Roman writers such as Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, Cicero (44) I.XVI.90. Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

. Following the Roman invasion of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, the druid orders were suppressed by the Roman government under the 1st-century CE emperors Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

and Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

, and had disappeared from the written record by the 2nd century.

In about 750 CE, the word ''druid'' appears in a poem by Blathmac

Saint Blathmac ( la, Blathmacus, Florentius) was a distinguished Irish monk, born in Ireland about 750 AD. He is known as "Blathmac, son of Flann", to distinguish him from the poet and monk Blathmac mac Con Brettan.

He was killed and became a ...

, who wrote about Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, saying that he was "better than a prophet, more knowledgeable than every druid, a king who was a bishop and a complete sage." The druids appear in some of the medieval tales from Christianized Ireland like "Táin Bó Cúailnge

(Modern ; "the driving-off of the cows of Cooley"), commonly known as ''The Táin'' or less commonly as ''The Cattle Raid of Cooley'', is an epic from Irish mythology. It is often called "The Irish Iliad", although like most other early Iri ...

", where they are largely portrayed as sorcerers who opposed the coming of Christianity. In the wake of the Celtic revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gael ...

during the 18th and 19th centuries, fraternal and neopagan

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Afric ...

groups were founded based on ideas about the ancient druids, a movement known as Neo-Druidism

Druidry, sometimes termed Druidism, is a modern spirituality, spiritual or religion, religious movement that promotes the cultivation of honorable relationships with the physical landscapes, flora, fauna, and diverse peoples of the world, as w ...

. Many popular notions about druids, based on misconceptions of 18th-century scholars, have been largely superseded by more recent study.

Etymology

The English word ''druid'' derives from Latin ''druidēs'' (plural), which was considered by ancient Roman writers to come from the native Celtic Gaulish word for these figures. Piggott (1968) p. 89.Caroline aan de Wiel, "Druids the word", in ''Celtic Culture''. Other Roman texts employ the form ''druidae'', while the same term was used byGreek ethnographers

;Pre-Hellenistic Classical Greece

*Homer

*Anaximander

*Hecataeus of Miletus

*Massaliote Periplus

*Scylax of Caryanda (6th century BC)

*Herodotus

;Hellenistic period

*Pytheas (died c. 310 BC)

*''Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax'' (3rd or 4th century BC) ...

as (''druidēs''). Although no extant Romano-Celtic inscription is known to contain the form, the word is cognate with the later insular Celtic words, Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writt ...

''druí'' 'druid, sorcerer', Old Cornish

Cornish ( Standard Written Form: or ) , is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. It is a revived language, having become extinct as a living community language in Cornwall at the end of the 18th century. However, k ...

''druw'', Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh ( cy, Cymraeg Canol, wlm, Kymraec) is the label attached to the Welsh language of the 12th to 15th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This form of Welsh developed directly from Old Welsh ( cy, Hen G ...

''dryw'' 'seer

In the United States, the efficiency of air conditioners is often rated by the seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER) which is defined by the Air Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, a trade association, in its 2008 standard AHRI ...

; wren

Wrens are a family of brown passerine birds in the predominantly New World family Troglodytidae. The family includes 88 species divided into 19 genera. Only the Eurasian wren occurs in the Old World, where, in Anglophone regions, it is commonly ...

'. Based on all available forms, the hypothetical proto-Celtic word may be reconstructed as *''dru-wid-s'' (pl. *''druwides'') meaning "oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

-knower". The two elements go back to the Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

roots ''*deru-'' and ''*weid-'' "to see". The sense of "oak-knower" or "oak-seer" is supported by Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

, who in his ''Natural History'' considered the word to contain the Greek noun ''drýs'' (δρύς), "oak-tree" and the Greek suffix ''-idēs'' (-ιδης). Both Old Irish ''druí'' and Middle Welsh ''dryw'' could refer to the wren

Wrens are a family of brown passerine birds in the predominantly New World family Troglodytidae. The family includes 88 species divided into 19 genera. Only the Eurasian wren occurs in the Old World, where, in Anglophone regions, it is commonly ...

, possibly connected with an association of that bird with augury

Augury is the practice from ancient Roman religion of interpreting omens from the observed behavior of birds. When the individual, known as the augur, interpreted these signs, it is referred to as "taking the auspices". "Auspices" (Latin ''aus ...

in Irish and Welsh tradition (see also Wren Day

Wren Day, also known as Wren's Day, Day of the Wren, or Hunt the Wren Day ( ga, Lá an Dreoilín), is an Irish celebration held on 26 December, St. Stephen's Day in a number of countries across Europe. The tradition consists of "hunting" a wren ( ...

).

Practices and doctrines

Sources by ancient and medieval writers provide an idea of the religious duties and social roles involved in being a druid.Societal role and training

The Greco-Roman and the vernacular Irish sources agree that the druids played an important part in pagan Celtic society. In his description,

The Greco-Roman and the vernacular Irish sources agree that the druids played an important part in pagan Celtic society. In his description, Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

wrote that they were one of the two most important social groups in the region (alongside the ''equites'', or nobles) and were responsible for organizing worship and sacrifices, divination, and judicial procedure in Gallic, British, and Irish societies. Caesar, Julius. ''De bello gallico''. VI.13–18. He wrote that they were exempt from military service and from paying taxes, and had the power to excommunicate people from religious festivals, making them social outcasts. Two other classical writers, Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, wrote about the role of druids in Gallic society, stating that the druids were held in such respect that if they intervened between two armies they could stop the battle.

Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest Roman geographer. He was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nearly to the year 1500. It occupies less ...

was the first author to say that the druids' instruction was secret and took place in caves and forests.

Druidic lore consisted of a large number of verses learned by heart, and Caesar remarked that it could take up to twenty years to complete the course of study. What was taught to druid novices anywhere is conjecture: of the druids' oral literature

Oral literature, orature or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung as opposed to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used vary ...

, not one certifiably ancient verse is known to have survived, even in translation. All instruction was communicated orally, but for ordinary purposes, Caesar reports, the Gauls had a written language in which they used Greek letters. In this he probably draws on earlier writers; by the time of Caesar, Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic languages, Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium ...

inscriptions had moved from Greek script to Latin script.

Sacrifice

Greek and Roman writers frequently made reference to the druids as practitioners of

Greek and Roman writers frequently made reference to the druids as practitioners of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

. Caesar says those who had been found guilty of theft or other criminal offences were considered preferable for use as sacrificial victims, but when criminals were in short supply, innocents would be acceptable. A form of sacrifice recorded by Caesar was the burning alive of victims in a large wooden effigy, now often known as a wicker man

A wicker man was purportedly a large wicker statue in which the druids (priests of Celtic paganism) Human sacrifice, sacrificed humans and Animal sacrifice, animals by burning. The main evidence for this practice is a sentence by Ancient Rome, Ro ...

. A differing account came from the 10th-century ''Commenta Bernensia {{Short description, 10th-century manuscript

The ''Commenta Bernensia'', also known as the Bern scholia, are commentaries or marginal notes in a 10th-century manuscript, Cod. 370, preserved in the Burgerbibliothek of Berne, Switzerland.

The comment ...

'', which stated that sacrifices to the deities Teutates

Toutatis or Teutates is a Celtic god who was worshipped primarily in ancient Gaul and Britain. His name means "god of the tribe", and he has been widely interpreted as a tribal protector.Paul-Marie Duval (1993). ''Les dieux de la Gaule.'' Éditio ...

, Esus

Esus, Hesus, or Aisus was a Brittonic and Gaulish god known from two monumental statues and a line in Lucan's '' Bellum civile''.

Name

T. F. O'Rahilly derives the theonym ''Esus'', as well as ''Aoibheall'', ''Éibhleann'', ''Aoife'', and ...

and Taranis

In Celtic mythology, Taranis (Proto-Celtic: *''Toranos'', earlier ''*Tonaros''; Latin: Taranus, earlier Tanarus) is the god of thunder, who was worshipped primarily in Gaul, Hispania, Britain, and Ireland, but also in the Rhineland and Danube r ...

were by drowning, hanging and burning, respectively (see threefold death

In algebraic geometry, a 3-fold or threefold is a 3-dimensional algebraic variety.

The Mori program

In algebraic geometry, the minimal model program is part of the birational classification of algebraic varieties. Its goal is to construct a bira ...

).

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

asserts that a sacrifice acceptable to the Celtic gods

The gods and goddesses of the pre-Christian Celtic peoples are known from a variety of sources, including ancient places of worship, statues, engravings, cult objects and place or personal names. The ancient Celts appear to have had a pantheon ...

had to be attended by a druid, for they were the intermediaries between the people and the divinities. He remarked upon the importance of prophets in druidic ritual:

Archaeological evidence from western Europe has been widely used to support the view that Iron Age Celts practiced human sacrifice. Mass graves found in a ritual context dating from this period have been unearthed in Gaul, at both Gournay-sur-Aronde

Gournay-sur-Aronde () is a commune in the Oise department in northern France.

Gournay-sur-Aronde is best known for a Late Iron Age sanctuary that dates back to the 4th century BCE, and was burned and levelled at the end of the 1st century BCE. I ...

and Ribemont-sur-Ancre

Ribemont-sur-Ancre (; pcd, Ribemont-su-Inke) is a commune in the Somme ''département'' in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

The commune is situated northeast of Amiens, on the D119 road and by the banks of the river Ancre

The ...

in the region of the Belgae chiefdom. The excavator of these sites, Jean-Louis Brunaux, interpreted them as areas of human sacrifice in devotion to a war god, although this view was criticized by another archaeologist, Martin Brown, who believed that the corpses might be those of honoured warriors buried in the sanctuary rather than sacrifices. Some historians have questioned whether the Greco-Roman writers were accurate in their claims. J. Rives remarked that it was "ambiguous" whether druids ever performed such sacrifices, for the Romans and Greeks were known to project what they saw as barbarian traits onto foreign peoples including not only druids but Jews and Christians as well, thereby confirming their own "cultural superiority" in their own minds.

Nora Chadwick

Nora Kershaw Chadwick CBE FSA FBA (28 January 1891 – 24 April 1972) was an English philologist who specialized in Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Old Norse studies.

Early life and education

Nora Kershaw was born in Lancashire in 1891, the first dau ...

, an expert in medieval Welsh and Irish literature who believed the druids to be great philosophers, has also supported the idea that they had not been involved in human sacrifice, and that such accusations were imperialist Roman propaganda.

Philosophy

Alexander Cornelius Polyhistor referred to the druids as philosophers and called their doctrine of the immortality of the soul andreincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

or metempsychosis

Metempsychosis ( grc-gre, μετεμψύχωσις), in philosophy, is the transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. The term is derived from ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualised by modern philoso ...

, "Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

":

Caesar made similar observations:

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, writing in 36 BCE, described how the druids followed "the Pythagorean doctrine", that human souls "are immortal and after a prescribed number of years they commence a new life in a new body".Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

. ''Bibliotheca historicae''. V.21–22. In 1928, folklorist Donald A. Mackenzie speculated that Buddhist missionaries had been sent by the Indian king Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

. Caesar noted the druidic doctrine of the original ancestor of the tribe, whom he referred to as '' Dispater'', or ''Father Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

''.

Druids in mythology

Druids play a prominent role inIrish folklore

Irish folklore ( ga, béaloideas) refers to the folktales, balladry, music, dance, and so forth, ultimately, all of folk culture.

Irish folklore, when mentioned to many people, conjures up images of banshees, fairies, leprechauns and people gath ...

, generally serving lords and kings as high ranking priest-counselors with the gift of prophecy and other assorted mystical abilitiesthe best example of these possibly being Cathbad

Cathbad () or Cathbhadh (modern spelling) is the chief druid in the court of King Conchobar mac Nessa in the Ulster Cycle of Irish Mythology.

He features in both accounts of Conchobar's birth, in one of which he is the king's father. In the first ...

. The chief druid in the court of King Conchobar mac Nessa

Conchobar mac Nessa (son of Ness) is the king of Ulaid, Ulster in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. He rules from Emain Macha (Navan Fort, near Armagh). He is usually said to be the son of the High King of Ireland, High King Fachtna Fáthach, ...

of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, Cathbad features in several tales, most of which detail his ability to foretell the future. In the tale of Deirdre of the Sorrows

''Deirdre of the Sorrows'' is a three-act play written by Irish playwright John Millington Synge in 1909. The play, based on Irish mythology, in particular the myths concerning Deirdre, Naoise, and Conchobar, was unfinished at the author's death o ...

the foremost tragic heroine

A tragic hero is the protagonist of a tragedy. In his ''Poetics'', Aristotle records the descriptions of the tragic hero to the playwright and strictly defines the place that the tragic hero must play and the kind of man he must be. Aristotle ba ...

of the Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle ( ga, an Rúraíocht), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly coun ...

the druid prophesied before the court of Conchobar that Deirdre would grow up to be very beautiful, and that kings and lords would go to war over her, much blood would be shed because of her, and Ulster's three greatest warriors would be forced into exile for her sake. This prophecy, ignored by the king, came true.

The greatest of these mythological druids was Amergin Glúingel

Amergin ''Glúingel'' ("white knees") (also spelled Amhairghin Glúngheal) or ''Glúnmar'' ("big knee") is a bard, druid and judge for the Milesians in the Irish Mythological Cycle. He was appointed Chief Ollam of Ireland by his two brothers th ...

, a bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

and judge for the Milesians featured in the Mythological Cycle

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

. The Milesians were seeking to overrun the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuath(a) Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu (Irish goddess), Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deity, ...

and win the land of Ireland but, as they approached, the druids of the Tuatha Dé Danann raised a magical storm to bar their ships from making landfall. Thus Amergin called upon the spirit of Ireland itself, chanting a powerful incantation that has come to be known as ''The Song of Amergin'' and, eventually (after successfully making landfall), aiding and dividing the land between his royal brothers in the conquest of Ireland, earning the title Chief Ollam of Ireland

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

.

Other such mythological druids were Tadg mac Nuadat

Tadg, son of Nuada, was a druid and the maternal grandfather of Fionn mac Cumhail in the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology. It is unclear whether his father was the short-lived High King Nuada Necht, the god Nuada Airgetlam of the Tuatha Dé Dana ...

of the Fenian Cycle

The Fenian Cycle (), Fianna Cycle or Finn Cycle ( ga, an Fhiannaíocht) is a body of early Irish literature focusing on the exploits of the mythical hero Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill and his warrior band the Fianna. Sometimes called the Ossian ...

, and Mug Ruith

Mug Ruith (or Mogh Roith, "slave of the wheel") is a figure in Irish mythology, a powerful blind druid of Munster who lived on Valentia Island, County Kerry. He could grow to enormous size, and his breath caused storms and turned men to stone. He ...

, a powerful blind druid of Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

.

Female druids

Irish mythology

Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally passed down orally in the prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later written down in the early medieval era by C ...

has a number of female druids, often sharing similar prominent cultural and religious roles with their male counterparts. The Irish have several words for female druids, such as ''bandruí'' ("woman-druid"), found in tales such as ''Táin Bó Cúailnge

(Modern ; "the driving-off of the cows of Cooley"), commonly known as ''The Táin'' or less commonly as ''The Cattle Raid of Cooley'', is an epic from Irish mythology. It is often called "The Irish Iliad", although like most other early Iri ...

''; 1c: "dialt feminine declension, Auraic. 1830. bandruí druidess; female skilled in magic arts: tri ferdruid ┐ tri bandrúid, TBC 2402 = dī (leg. tri) drúid insin ┐ a teóra mná, TBC² 1767." Bodhmall

Bodhmall (or bodhmann, Bómall,''Dóiteoir na Samhna'', by Darach Ó Scalaí, Bodmall, or Bodbmall) is one of Fionn mac Cumhaill's childhood foster mothers in the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology and the daughter of Tréanmór mac Suailt. She is ...

, featured in the Fenian Cycle

The Fenian Cycle (), Fianna Cycle or Finn Cycle ( ga, an Fhiannaíocht) is a body of early Irish literature focusing on the exploits of the mythical hero Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill and his warrior band the Fianna. Sometimes called the Ossian ...

, and one of Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill ( ; Old and mga, Find or ''mac Cumail'' or ''mac Umaill''), often anglicized Finn McCool or MacCool, is a hero in Irish mythology, as well as in later Scottish and Manx folklore. He is leader of the ''Fianna'' bands of ...

's childhood caretakers;Parkes, "Fosterage, Kinship, & Legend", Cambridge University Press, Comparative Studies in Society and History (2004), 46: pp. 587–615. and Tlachtga

Tlachtga (Modern Irish: ''Tlachta'') was a powerful druidess in Irish mythology and the red-haired daughter of the arch-druid Mug Ruith. She accompanied him on his world travels, learning his magical secrets and discovering sacred stones in Italy. ...

,Jones, Mary"The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn mac Cumhaill"

. From maryjones.us. Retrieved July 22, 2008. daughter of the druid

Mug Ruith

Mug Ruith (or Mogh Roith, "slave of the wheel") is a figure in Irish mythology, a powerful blind druid of Munster who lived on Valentia Island, County Kerry. He could grow to enormous size, and his breath caused storms and turned men to stone. He ...

who, according to Irish tradition, is associated with the Hill of Ward

The Hill of Ward (, formerly ''Tlachtgha'') is a hill in County Meath, Ireland.

Geography

The hill lies between Athboy (to the west) and Ráth Chairn (to the east). During medieval times it was the site of great festivals, including one at w ...

, site of prominent festivals held in Tlachtga's honour during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

.MacKillop, James (1998). ''Dictionary of Celtic Mythology''. London: Oxford. . *page numbers needed*

Biróg

Biróg (Biroge of the Mountain, Birog), in Irish folklore is the ''leanan sídhe'' or the female familiar spirit of Cian who aids him in the folktale about his wooing of Balor's daughter Eithne.

She is reinvented as a druidess in Lady Gregory an ...

, another ''bandruí'' of the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuath(a) Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu (Irish goddess), Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deity, ...

, plays a key role in an Irish folktale where the Fomorian

The Fomorians or Fomori ( sga, Fomóire, Modern ga, Fomhóraigh / Fomóraigh) are a supernatural race in Irish mythology, who are often portrayed as hostile and monstrous beings. Originally they were said to come from under the sea or the eart ...

warrior Balor

In Irish mythology, Balor or Balar was a leader of the Fomorians, a group of malevolent supernatural beings. He is often described as a giant with a large eye that wreaks destruction when opened. Balor takes part in the Battle of Mag Tuired, a ...

attempts to thwart a prophecy foretelling that he would be killed by his own grandson by imprisoning his only daughter Eithne

Eithne is a female personal name of Irish origin, meaning "kernel" or "grain". Other spellings and earlier forms include Ethnea, Ethlend, Ethnen, Ethlenn, Ethnenn, Eithene, Ethne, Aithne, Enya, Ena, Edna, Etney, Eithnenn, Eithlenn, Eithna, Ethni, ...

in the tower of Tory Island

Tory Island, or simply Tory (officially known by its Irish name ''Toraigh''),Toraigh/Tory Island

O'Donovan, John (ed. & trans.), ''Annala Rioghachta Éireann: Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters'' Vol. 1, 1856, pp. 18–21, footnote ''S''T. W. Rolleston, ''Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race'', 1911, pp. 109–112.

According to classical authors, the Gallizenae (or Gallisenae) were virgin priestesses of the

According to classical authors, the Gallizenae (or Gallisenae) were virgin priestesses of the

The earliest surviving literary evidence of druids emerges from the classical world of Greece and Rome. Archaeologist

The earliest surviving literary evidence of druids emerges from the classical world of Greece and Rome. Archaeologist

The earliest extant text that describes druids in detail is

The earliest extant text that describes druids in detail is

Other classical writers also commented on the druids and their practices. Caesar's contemporary,

Other classical writers also commented on the druids and their practices. Caesar's contemporary,

An excavated burial in Deal, Kent discovered the "Deal Warrior"a man buried around 200–150 BCE with a sword and shield, and wearing an almost unique head-band, too thin to be part of a leather helmet. The crown is bronze with a broad band around the head and a thin strip crossing the top of the head. Since traces of hair were left on the metal it must have been worn without any padding beneath. The form of the headdress resembles depictions of Romano-British priests from several centuries later, leading to speculation among archaeologists that the man might have been a religious officiala druid.

An excavated burial in Deal, Kent discovered the "Deal Warrior"a man buried around 200–150 BCE with a sword and shield, and wearing an almost unique head-band, too thin to be part of a leather helmet. The crown is bronze with a broad band around the head and a thin strip crossing the top of the head. Since traces of hair were left on the metal it must have been worn without any padding beneath. The form of the headdress resembles depictions of Romano-British priests from several centuries later, leading to speculation among archaeologists that the man might have been a religious officiala druid.

From the 18th century, England and Wales saw a revival of interest in the druids. John Aubrey (1626–1697) had been the first modern writer to (incorrectly) connect Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments with the druids; since Aubrey's views were confined to his notebooks, the first wide audience for this idea were readers of William Stukeley (1687–1765). It is incorrectly believed that John Toland (1670–1722) founded the Ancient Druid Order; however, the research of historian Ronald Hutton has revealed that the ADO was founded by George Watson MacGregor Reid in 1909. The order never used (and still does not use) the title "Archdruid" for any member, but falsely credited William Blake as having been its "Chosen Chief" from 1799–1827, without corroboration in Blake's numerous writings or among modern Blake scholars. Blake's bardic mysticism derives instead from the pseudo-Ossianic epics of Macpherson; his friend Frederick Tatham's depiction of Blake's imagination, "clothing itself in the dark stole of moral sanctity"— in the precincts of Westminster Abbey— "it dwelt amid the druid terrors", is generic rather than specifically neo-druidic. John Toland was fascinated by Aubrey's Stonehenge theories, and wrote his own book about the monument without crediting Aubrey. The roles of bards in 10th century Wales had been established by Hywel Dda and it was during the 18th century that the idea arose that druids had been their predecessors.

The 19th century idea, gained from uncritical reading of the ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Gallic Wars'', that under cultural-military pressure from Rome the druids formed the core of 1st century BC resistance among the Gauls, was examined and dismissed before World War II, though it remains current in folk history.

Druids began to figure widely in popular culture with the first advent of Romanticism. François-René de Chateaubriand, Chateaubriand's novel ''Les Martyrs'' (1809) narrated the doomed love of a druid priestess and a Roman soldier; though Chateaubriand's theme was the triumph of Christianity over pagan druids, the setting was to continue to bear fruit. Opera provides a barometer of well-informed popular European culture in the early 19th century: In 1817 Giovanni Pacini brought druids to the stage in Trieste with an opera to a libretto by Felice Romani about a druid priestess, ''La Sacerdotessa d'Irminsul'' ("The Priestess of Irminsul"). Vincenzo Bellini's druidic opera, ''Norma (opera), Norma'' was a fiasco at La Scala, when it premiered the day after Christmas, 1831; but in 1833 it was a hit in London. For its libretto, Felice Romani reused some of the pseudo-druidical background of ''La Sacerdotessa'' to provide colour to a standard theatrical conflict of love and duty. The story was similar to that of Medea, as it had recently been recast for a popular Parisian play by Alexandre Soumet: the chaste goddess (''casta diva'') addressed in ''Norma''s hit aria is the moon goddess, worshipped in the "grove of the Irminenschaft, Irmin statue".

From the 18th century, England and Wales saw a revival of interest in the druids. John Aubrey (1626–1697) had been the first modern writer to (incorrectly) connect Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments with the druids; since Aubrey's views were confined to his notebooks, the first wide audience for this idea were readers of William Stukeley (1687–1765). It is incorrectly believed that John Toland (1670–1722) founded the Ancient Druid Order; however, the research of historian Ronald Hutton has revealed that the ADO was founded by George Watson MacGregor Reid in 1909. The order never used (and still does not use) the title "Archdruid" for any member, but falsely credited William Blake as having been its "Chosen Chief" from 1799–1827, without corroboration in Blake's numerous writings or among modern Blake scholars. Blake's bardic mysticism derives instead from the pseudo-Ossianic epics of Macpherson; his friend Frederick Tatham's depiction of Blake's imagination, "clothing itself in the dark stole of moral sanctity"— in the precincts of Westminster Abbey— "it dwelt amid the druid terrors", is generic rather than specifically neo-druidic. John Toland was fascinated by Aubrey's Stonehenge theories, and wrote his own book about the monument without crediting Aubrey. The roles of bards in 10th century Wales had been established by Hywel Dda and it was during the 18th century that the idea arose that druids had been their predecessors.

The 19th century idea, gained from uncritical reading of the ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Gallic Wars'', that under cultural-military pressure from Rome the druids formed the core of 1st century BC resistance among the Gauls, was examined and dismissed before World War II, though it remains current in folk history.

Druids began to figure widely in popular culture with the first advent of Romanticism. François-René de Chateaubriand, Chateaubriand's novel ''Les Martyrs'' (1809) narrated the doomed love of a druid priestess and a Roman soldier; though Chateaubriand's theme was the triumph of Christianity over pagan druids, the setting was to continue to bear fruit. Opera provides a barometer of well-informed popular European culture in the early 19th century: In 1817 Giovanni Pacini brought druids to the stage in Trieste with an opera to a libretto by Felice Romani about a druid priestess, ''La Sacerdotessa d'Irminsul'' ("The Priestess of Irminsul"). Vincenzo Bellini's druidic opera, ''Norma (opera), Norma'' was a fiasco at La Scala, when it premiered the day after Christmas, 1831; but in 1833 it was a hit in London. For its libretto, Felice Romani reused some of the pseudo-druidical background of ''La Sacerdotessa'' to provide colour to a standard theatrical conflict of love and duty. The story was similar to that of Medea, as it had recently been recast for a popular Parisian play by Alexandre Soumet: the chaste goddess (''casta diva'') addressed in ''Norma''s hit aria is the moon goddess, worshipped in the "grove of the Irminenschaft, Irmin statue".

A central figure in 19th century Romanticist, Neo-druid revival, is Welshman Edward Williams, better known as Iolo Morganwg. His writings, published posthumously as ''The Iolo Manuscripts'' (1849) and ''Barddas'' (1862), are not considered credible by contemporary scholars. Williams said that he had collected ancient knowledge in a "Gorsedd of Bards of the Isles of Britain" he had organized. While bits and pieces of the ''Barddas'' still turn up in some "Neo-Druidism, Neo-Druidic" works, the documents are not considered relevant to ancient practice by most scholars.

Another Welshman, William Price (physician), William Price (4 March 180023 January 1893), a physician known for his support of Welsh nationalism, Chartism, and his involvement with the Neo-Druidic religious movement, has been recognized as a significant figures of 19th century Wales. He was arrested for cremating his deceased son, a practice he believed to be a druid ritual, but won his case; this in turn led to the Cremation Act 1902.#Pow05, Powell (2005) p. 3.#Hut09, Hutton (2009) p. 253.

In 1927 T. D. Kendrick sought to dispel the pseudo-historical aura that had accrued to druids, asserting, "a prodigious amount of rubbish has been written about Druidism"; Neo-druidism has nevertheless continued to shape public perceptions of the historical druids.

Some strands of contemporary Neo-Druidism are a continuation of the 18th century revival and thus are built largely around writings produced in the 18th century and after by second-hand sources and theorists. Some are monotheism, monotheistic. Others, such as the largest druid group in the world, the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, draw on a wide range of sources for their teachings. Members of such Neo-Druid groups may be Neopaganism, Neopagan, occultist, Christian or non-specifically spiritual.

A central figure in 19th century Romanticist, Neo-druid revival, is Welshman Edward Williams, better known as Iolo Morganwg. His writings, published posthumously as ''The Iolo Manuscripts'' (1849) and ''Barddas'' (1862), are not considered credible by contemporary scholars. Williams said that he had collected ancient knowledge in a "Gorsedd of Bards of the Isles of Britain" he had organized. While bits and pieces of the ''Barddas'' still turn up in some "Neo-Druidism, Neo-Druidic" works, the documents are not considered relevant to ancient practice by most scholars.

Another Welshman, William Price (physician), William Price (4 March 180023 January 1893), a physician known for his support of Welsh nationalism, Chartism, and his involvement with the Neo-Druidic religious movement, has been recognized as a significant figures of 19th century Wales. He was arrested for cremating his deceased son, a practice he believed to be a druid ritual, but won his case; this in turn led to the Cremation Act 1902.#Pow05, Powell (2005) p. 3.#Hut09, Hutton (2009) p. 253.

In 1927 T. D. Kendrick sought to dispel the pseudo-historical aura that had accrued to druids, asserting, "a prodigious amount of rubbish has been written about Druidism"; Neo-druidism has nevertheless continued to shape public perceptions of the historical druids.

Some strands of contemporary Neo-Druidism are a continuation of the 18th century revival and thus are built largely around writings produced in the 18th century and after by second-hand sources and theorists. Some are monotheism, monotheistic. Others, such as the largest druid group in the world, the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, draw on a wide range of sources for their teachings. Members of such Neo-Druid groups may be Neopaganism, Neopagan, occultist, Christian or non-specifically spiritual.

In the 20th century, as new forms of textual criticism and archaeological methods were developed, allowing for greater accuracy in understanding the past, various historians and archaeologists published books on the subject of the druids and came to their own conclusions. Archaeologist

In the 20th century, as new forms of textual criticism and archaeological methods were developed, allowing for greater accuracy in understanding the past, various historians and archaeologists published books on the subject of the druids and came to their own conclusions. Archaeologist

World History Encyclopedia - Druid

* {{Authority control Druidry, Esoteric schools of thought Religious occupations

Bé Chuille

Bé Chuille, also known as Becuille and Bé Chuma, is the daughter of Flidais and one of the Tuatha Dé Danann in Irish mythology. In a tale from the Metrical Dindshenchas, she is a good sorceress who joins three other of the Tuatha Dé to defeat ...

daughter of the woodland goddess Flidais

Flidas or Flidais (modern spelling: Fliodhas, Fliodhais) is a female figure in Irish Mythology, known by the epithet ''Foltchaín'' ("beautiful hair"). She is believed to have been a goddess of cattle and fertility.

Mythology

Flidas is mentioned ...

and sometimes described as a sorceress rather than a bandruífeatures in a tale from the Metrical Dindshenchas

''Dindsenchas'' or ''Dindshenchas'' (modern spellings: ''Dinnseanchas'' or ''Dinnsheanchas'' or ''Dınnṡeanċas''), meaning "lore of places" (the modern Irish word ''dinnseanchas'' means "topography"), is a class of onomastic text in early Irish ...

where she joins three other of the Tuatha Dé to defeat the evil Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

witch Carman

In Celtic mythology, Carman or Carmun was a warrior and sorceress from Athens who tried to invade Ireland in the days of the Tuatha Dé Danann, along with her three sons, Dub ("black"), Dother ("evil") and Dian ("violence"). She used her magical ...

. Other bandrúi include Relbeo, a Nemedian druid who appears in The Book of Invasions

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

, where she is described as the daughter of the King of Greece and mother of Fergus Lethderg and Alma One-Tooth.O'Boyle, p. 150. Dornoll was a bandrúi in Scotland, who normally trained heroes in warfare, particularly Laegaire and Conall; she was the daughter of Domnall Mildemail.

The ''Gallizenae''

According to classical authors, the Gallizenae (or Gallisenae) were virgin priestesses of the

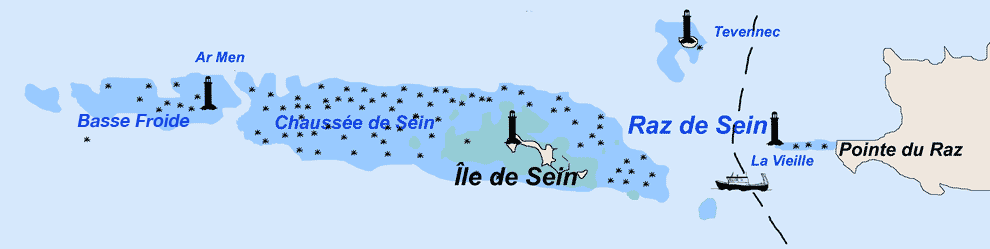

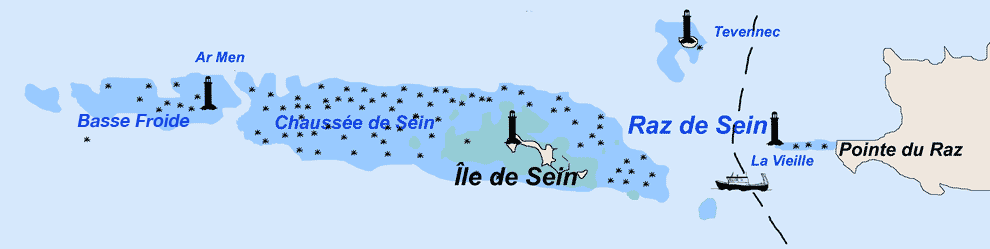

According to classical authors, the Gallizenae (or Gallisenae) were virgin priestesses of the Île de Sein

The Île de Sein is a Breton island in the Atlantic Ocean, off Finistère, eight kilometres from the Pointe du Raz (''raz'' meaning "water current"), from which it is separated by the Raz de Sein. Its Breton name is ''Enez-Sun''. The island, w ...

off Pointe du Raz, Finistère

Finistère (, ; br, Penn-ar-Bed ) is a department of France in the extreme west of Brittany. In 2019, it had a population of 915,090.

, western Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

. Their existence was first mentioned by the Greek geographer Artemidorus Ephesius

Artemidorus of Ephesus ( grc-gre, Ἀρτεμίδωρος ὁ Ἐφέσιος; la, Artemidorus Ephesius) was a Greek geographer, who flourished around 100 BC. His work in eleven books is often quoted by Strabo. What is thought to be a possibl ...

and later by the Greek historian Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, who wrote that their island was forbidden to men, but the women came to the mainland to meet their husbands. Which deities they honored is unknown. According to Pomponius Mela, the Gallizenae acted as both councilors and practitioners of the healing arts:

Gaul druidesses

According to ''Historia Augusta

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the sim ...

'', Alexander Severus

Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (1 October 208 – 21/22 March 235) was a Roman emperor, who reigned from 222 until 235. He was the last emperor from the Severan dynasty. He succeeded his slain cousin Elagabalus in 222. Alexander himself was ...

received a prophecy about his death by a Gaul druidess (''druiada''). The work also has Aurelian

Aurelian ( la, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus; 9 September 214 October 275) was a Roman emperor, who reigned during the Crisis of the Third Century, from 270 to 275. As emperor, he won an unprecedented series of military victories which reunited t ...

questioning those druidesses about the fate of his descendants, to which they answered in favor of Claudius II

Marcus Aurelius Claudius "Gothicus" (10 May 214 – January/April 270), also known as Claudius II, was Roman emperor from 268 to 270. During his reign he fought successfully against the Alemanni and decisively defeated the Goths at the Battle ...

. Flavius Vopiscus

The gens Flavia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Its members are first mentioned during the last three centuries of the Republic. The first of the Flavii to achieve prominence was Marcus Flavius, tribune of the plebs in 327 and 323 BC; ho ...

is also quoted as recalling a prophecy received by Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

from a Tungri

The Tungri (or Tongri, or Tungrians) were a tribe, or group of tribes, who lived in the Belgic part of Gaul, during the times of the Roman Empire. Within the Roman Empire, their territory was called the ''Civitas Tungrorum''. They were described by ...

druidess.

Sources on druid beliefs and practices

Greek and Roman records

The earliest surviving literary evidence of druids emerges from the classical world of Greece and Rome. Archaeologist

The earliest surviving literary evidence of druids emerges from the classical world of Greece and Rome. Archaeologist Stuart Piggott

Stuart Ernest Piggott, (28 May 1910 – 23 September 1996) was a British archaeologist, best known for his work on prehistoric Wessex.

Early life

Piggott was born in Petersfield, Hampshire, the son of G. H. O. Piggott, and was educated t ...

compared the attitude of the Classical authors toward the druids as being similar to the relationship that had existed in the 15th and 18th centuries between Europeans and the societies that they were just encountering in other parts of the world, such as the Americas and the South Sea Islands. He highlighted the attitude of "primitivism

Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that either emulates or aspires to recreate a "primitive" experience. It is also defined as a philosophical doctrine that considers "primitive" peoples as nobler than civilized peoples and was an o ...

" in both Early Modern Europeans and Classical authors, owing to their perception that these newly encountered societies had less technological development and were backward in socio-political development.

Historian Nora Chadwick

Nora Kershaw Chadwick CBE FSA FBA (28 January 1891 – 24 April 1972) was an English philologist who specialized in Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Old Norse studies.

Early life and education

Nora Kershaw was born in Lancashire in 1891, the first dau ...

, in a categorization subsequently adopted by Piggott, divided the Classical accounts of the druids into two groups, distinguished by their approach to the subject as well as their chronological contexts. She calls the first of these groups the "Posidonian" tradition after one of its primary exponents, Posidonious, and notes that it takes a largely critical attitude towards the Iron Age societies of Western Europe that emphasizes their "barbaric" qualities. The second of these two groups is termed the "Alexandrian" group, being centred on the scholastic traditions of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

; she notes that it took a more sympathetic and idealized attitude toward these foreign peoples. Piggott drew parallels between this categorisation and the ideas of "hard primitivism" and "soft primitivism" identified by historians of ideas A. O. Lovejoy and Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

.

One school of thought has suggested that all of these accounts are inherently unreliable, and might be entirely fictional. They have suggested that the idea of the druid might have been a fiction created by Classical writers to reinforce the idea of the barbaric "other" who existed beyond the civilized Greco-Roman world, thereby legitimizing the expansion of the Roman Empire into these areas. Aldhouse-Green (2010) p. xv.

The earliest record of the druids comes from two Greek texts of c. 300 BC: a history of philosophy written by Sotion

Sotion of Alexandria ( grc-gre, Σωτίων, ''gen''.: Σωτίωνος; fl. c. 200 – 170 BC) was a Greek doxographer and biographer, and an important source for Diogenes Laërtius. None of his works survive; they are known only indirectly. ...

of Alexandria, and a study of magic widely attributed to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

. Both texts are now lost, but are quoted in the 2nd century CE work ''Vitae'' by Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

.

Subsequent Greek and Roman texts from the 3rd century BCE refer to "barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

philosophers", possibly in reference to the Gaulish druids.

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

's ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico

''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' (; en, Commentaries on the Gallic War, italic=yes), also ''Bellum Gallicum'' ( en, Gallic War, italic=yes), is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Ca ...

'', book VI, written in the 50s or 40s BC. A general who was intent on conquering Gaul and Britain, Caesar described the druids as being concerned with "divine worship, the due performance of sacrifices, private or public, and the interpretation of ritual questions". He said they played an important part in Gaulish society, being one of the two respected classes along with the ''equites'' (in Rome the name for members of a privileged class above the common people, but also "horsemen") and that they performed the function of judges.

Caesar wrote that the druids recognized the authority of a single leader, who would rule until his death, when a successor would be chosen by vote or through conflict. He remarked that they met annually at a sacred place in the region occupied by the Carnute tribe in Gaul, while they viewed Britain as the centre of druidic study; and that they were not found among the German tribes to the east of the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

. According to Caesar, many young men were trained to be druids, during which time they had to learn all the associated lore by heart. He also said that their main teaching was "the souls do not perish, but after death pass from one to another". They were concerned with "the stars and their movements, the size of the cosmos and the earth, the world of nature, and the power and might of the immortal gods", indicating they were involved with not only such common aspects of religion as theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount (lexicographer), Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in ...

, but also astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

. Caesar held that they were "administrators" during rituals of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

, for which criminals were usually used, and that the method was by burning in a wicker man

A wicker man was purportedly a large wicker statue in which the druids (priests of Celtic paganism) Human sacrifice, sacrificed humans and Animal sacrifice, animals by burning. The main evidence for this practice is a sentence by Ancient Rome, Ro ...

.

Though he had first-hand experience of Gaulish people, and therefore likely druids, Caesar's account has been widely criticized by modern historians as inaccurate. One issue raised by such historians as Fustel de Coulanges was that while Caesar described the druids as a significant power within Gaulish society, he did not mention them even once in his accounts of his Gaulish conquests. Nor did Aulus Hirtius, who continued Caesar's account of the Gallic Wars after Caesar's death. Hutton believed that Caesar had manipulated the idea of the druids so they would appear both civilized (being learned and pious) and barbaric (performing human sacrifice) to Roman readers, thereby representing both "a society worth including in the Roman Empire" and one that required civilizing with Roman rule and values, thus justifying his wars of conquest. Sean Dunham suggested that Caesar had simply taken the Roman religious functions of senators and applied them to the druids. Daphne Nash believed it "not unlikely" that he "greatly exaggerates" both the centralized system of druidic leadership and its connection to Britain.

Other historians have accepted that Caesar's account might be more accurate. Norman J. DeWitt surmised that Caesar's description of the role of druids in Gaulish society may report an idealized tradition, based on the society of the 2nd century BC, before the pan-Gallic confederation led by the Arverni was smashed in 121 BC, followed by the invasions of Teutones and Cimbri, rather than on the demoralized and disunited Gaul of his own time. John Creighton has speculated that in Britain, the druidic social influence was already in decline by the mid-1st century BCE, in conflict with emergent new power structures embodied in paramount chieftains. Other scholars see the Roman conquest itself as the main reason for the decline of the druid orders. Archaeologist Miranda Aldhouse-Green (2010) asserted that Caesar offered both "our richest textual source" regarding the druids, and "one of the most reliable". She defended the accuracy of his accounts by highlighting that while he may have embellished some of his accounts to justify Roman imperial conquest, it was "inherently unlikely" that he constructed a fictional class system for Gaul and Britain, particularly considering that he was accompanied by a number of other Roman senators who would have also been sending reports on the conquest to Rome, and who would have challenged his inclusion of serious falsifications.

Cicero, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo and Tacitus

Other classical writers also commented on the druids and their practices. Caesar's contemporary,

Other classical writers also commented on the druids and their practices. Caesar's contemporary, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, noted that he had met a Gallic druid, Diviciacus (Aedui), Divitiacus, of the Aedui tribe. Divitiacus supposedly knew much about the natural world and performed divination through augury

Augury is the practice from ancient Roman religion of interpreting omens from the observed behavior of birds. When the individual, known as the augur, interpreted these signs, it is referred to as "taking the auspices". "Auspices" (Latin ''aus ...

. Whether Diviaticus was genuinely a druid can however be disputed, for Caesar also knew this figure, and wrote about him, calling him by the more Gaulish-sounding (and thereby presumably the more authentic) Diviciacus, but never referred to him as a druid and indeed presented him as a political and military leader.

Another classical writer to take up describing the druids not too long after was Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, who published this description in his ''Bibliotheca historicae'' in 36 BC. Alongside the druids, or as he called them, ''drouidas'', whom he viewed as philosophers and theologians, he remarked how there were poets and singers in Celtic society whom he called ''bardous'', or bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

s. Such an idea was expanded on by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, writing in the 20s CE, who declared that amongst the Gauls, there were three types of honoured figures:

* the poets and singers known as ''bardoi'',

* the diviners and specialists in the natural world known as ''o'vateis'', and

* those who studied "moral philosophy", the ''druidai''.

Roman writer Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, himself a senator and historian, described how when the Roman army, led by Suetonius Paulinus, attacked the island of Mona (Anglesey; Welsh language, Welsh: ''Ynys Môn''), the legionaries were awestruck on landing, by the appearance of a band of druids, who, with hands uplifted to the sky, poured forth terrible imprecations on the heads of the invaders. He says these "terrified our soldiers who had never seen such a thing before". The courage of the Romans, however, soon overcame such fears, according to the Roman historian; the Britons were put to flight, and the sacred groves of Mona were cut down. Tacitus is also the only primary source that gives accounts of druids in Britain, but maintains a hostile point of view, seeing them as ignorant savages.

Irish and Welsh records

In the Middle Ages, after Ireland and Wales were Christianization, Christianized, druids appear in a number of written sources, mainly tales and stories such as ''Táin Bó Cúailnge

(Modern ; "the driving-off of the cows of Cooley"), commonly known as ''The Táin'' or less commonly as ''The Cattle Raid of Cooley'', is an epic from Irish mythology. It is often called "The Irish Iliad", although like most other early Iri ...

'', and in the hagiography, hagiographies of various saints. These were all written by Christian monks.

Irish literature and law codes

In Irish-language literature, druids''draoithe'', plural of ''draoi''are sorcerers with supernatural powers, who are respected in society, particularly for their ability to do divination. ''Dictionary of the Irish Language'' defines ''druí'' (which has numerous variant forms, including ''draoi'') as 'magician, wizard or diviner'. In the literature the druids cast spells and turn people into animals or stones, or curse peoples' crops to be blighted. When druids are portrayed in early Irish sagas and saints' lives set in pre-Christian Ireland, they are usually given high social status. The evidence of the law-texts, which were first written down in the 7th and 8th centuries, suggests that with the coming of Christianity the role of the druid in Irish society was rapidly reduced to that of a sorcerer who could be consulted to cast spells or do healing magic and that his standing declined accordingly. According to the early legal tract ''Bretha Crólige'', the sick-maintenance due to a druid, satirist and brigand (''díberg'') is no more than that due to a ''bóaire'' (an ordinary freeman). Another law-text, ''Uraicecht Becc'' ('small primer'), gives the druid a place among the ''dóer-nemed'' or professional classes which depend for their status on a patron, along with wrights, blacksmiths and entertainers, as opposed to the ''fili'', who alone enjoyed free ''nemed''-status.Welsh literature

While druids featured prominently in many medieval Irish sources, they were far rarer in their Welsh counterparts. Unlike the Irish texts, the Welsh term commonly seen as referring to the druids, ', was used to refer purely to prophets and not to sorcerers or pagan priests. Historian Ronald Hutton noted that there were two explanations for the use of the term in Wales: the first was that it was a survival from the pre-Christian era, when ''dryw'' had been ancient priests; the second was that the Welsh had borrowed the term from the Irish, as had the English (who used the terms ''dry'' and ''drycraeft'' to refer to magicians and magic (paranormal), magic respectively, most probably influenced by the Irish terms).Archaeology

As the historian Jane Webster stated, "individual druids ... are unlikely to be identified archaeologically". A. P. Fitzpatrick, in examining what he believed to be astral symbolism on Late Iron Age swords has expressed difficulties in relating any material culture, even the Coligny calendar, with druidic culture. Nonetheless, some archaeologists have attempted to link certain discoveries with written accounts of the druids. The archaeologist Anne Ross linked what she believed to be evidence ofhuman sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

in Celtic pagan society—such as the Lindow Man bog body—to the Greco-Roman accounts of human sacrifice being officiated over by the druids. Miranda Aldhouse-Green, professor of archaeology at Cardiff University, has noted that Suetonius's army would have passed very near the site whilst traveling to deal with Boudicca and postulates that the sacrifice may have been connected. A 1996 discovery of a skeleton buried with advanced medical and possibly divinatory equipment has, however, been nicknamed the "Druid of Colchester".

An excavated burial in Deal, Kent discovered the "Deal Warrior"a man buried around 200–150 BCE with a sword and shield, and wearing an almost unique head-band, too thin to be part of a leather helmet. The crown is bronze with a broad band around the head and a thin strip crossing the top of the head. Since traces of hair were left on the metal it must have been worn without any padding beneath. The form of the headdress resembles depictions of Romano-British priests from several centuries later, leading to speculation among archaeologists that the man might have been a religious officiala druid.

An excavated burial in Deal, Kent discovered the "Deal Warrior"a man buried around 200–150 BCE with a sword and shield, and wearing an almost unique head-band, too thin to be part of a leather helmet. The crown is bronze with a broad band around the head and a thin strip crossing the top of the head. Since traces of hair were left on the metal it must have been worn without any padding beneath. The form of the headdress resembles depictions of Romano-British priests from several centuries later, leading to speculation among archaeologists that the man might have been a religious officiala druid.

History of reception

Prohibition and decline under Roman rule

In the Gallic Wars of 58–51 BC, the Roman army, led byJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

, conquered the many tribal chiefdoms of Gaul, and annexed it as a part of the Roman Republic. According to accounts produced in the following centuries, the new rulers of Roman Gaul subsequently introduced measures to wipe out the druids from that country. According to Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

, writing in the 70s CE, it was the emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

(ruled 14–37 CE), who introduced laws banning not only druid practices, and other native soothsayers and healers, a move which Pliny applauded, believing it would end human sacrifice in Gaul. A somewhat different account of Roman legal attacks on the druids was made by Suetonius, writing in the 2nd century CE, when he stated that Rome's first emperor, Augustus (ruled 27 BC–14 CE), had decreed that no-one could be both a druid and a Roman citizen, and that this was followed by a law passed by the later Emperor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

(ruled 41–54 CE) which "thoroughly suppressed" the druids by banning their religious practices.

Possible late survival of Insular druid orders

The best evidence of a druidic tradition in the British Isles is the independent cognate of the proto-Celtic language, Celtic ''*druwid-'' in Insular Celtic: The Old Irish ''druídecht'' survives in the meaning of 'magic', and the Welsh ''dryw'' in the meaning of 'seer'. While the druids as a priestly caste were extinct with the Christianization of Wales, complete by the 7th century at the latest, the offices ofbard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

and of "seer" ( cy, dryw) persisted in Wales in the High Middle Ages, medieval Wales into the 13th century.

Classics professor Phillip Freeman discusses a later reference to 'dryades', which he translates as 'druidesses', writing, "The fourth century A.D. collection of imperial biographies known as the ''Historia Augusta

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the sim ...

'' contains three short passages involving Gaulish women called 'dryades' ('druidesses'). He points out that "In all of these, the women may not be direct heirs of the druids who were supposedly extinguished by the Romansbut in any case they do show that the druidic function of prophecy continued among the natives in Roman Gaul." However, the ''Historia Augusta'' is frequently interpreted by scholars as a largely satirical work, and such details might have been introduced in a humorous fashion. Additionally, female druids are mentioned in later Irish mythology, including the legend of Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill ( ; Old and mga, Find or ''mac Cumail'' or ''mac Umaill''), often anglicized Finn McCool or MacCool, is a hero in Irish mythology, as well as in later Scottish and Manx folklore. He is leader of the ''Fianna'' bands of ...

, who, according to the 12th century ''The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn'', is raised by the woman druid Bodhmall

Bodhmall (or bodhmann, Bómall,''Dóiteoir na Samhna'', by Darach Ó Scalaí, Bodmall, or Bodbmall) is one of Fionn mac Cumhaill's childhood foster mothers in the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology and the daughter of Tréanmór mac Suailt. She is ...

and her companion, another wise-woman.

Christian historiography and hagiography

The story of Vortigern, as reported by Nennius, gives one of the very few glimpses of possible druidic survival in Britain after the Roman arrival. He wrote that after being excommunicated by Germanus of Auxerre, the British leader Vortigern invited twelve druids to help him. In the lives of saints and martyrs, the druids are represented as magicians and diviners. In Adamnan's ''vita'' of Columba, two of them act as tutors to the daughters of Lóegaire mac Néill, the High King of Ireland, at the coming of Saint Patrick. They are represented as endeavouring to prevent the progress of Patrick and Saint Columba by raising clouds and mist. Before the battle of Culdremne (561 CE) a druid made an ''airbe drtiad'' ("fence of protection"?) round one of the armies, but what is precisely meant by the phrase is unclear. The Irish druids seem to have had a peculiar tonsure. The word ''druí'' is always used to render the Latin ''magus'', and in one passage St Columba speaks of Christ as his druid. Similarly, a life of Saint Beuno states that when he died he had a vision of "all the saints and druids". Sulpicius Severus' ''vita'' of Martin of Tours relates how Martin encountered a peasant funeral, carrying the body in a winding sheet, which Martin mistook for some druidic rites of sacrifice, "because it was the custom of the Gallic rustics in their wretched folly to carry about through the fields the images of demons veiled with a white covering". So Martin halted the procession by raising his pectoral cross: "Upon this, the miserable creatures might have been seen at first to become stiff like rocks. Next, as they endeavoured, with every possible effort, to move forward, but were not able to take a step farther, they began to whirl themselves about in the most ridiculous fashion, until, not able any longer to sustain the weight, they set down the dead body." Then discovering his error, Martin raised his hand again to let them proceed: "Thus", the hagiographer points out, "he both compelled them to stand when he pleased, and permitted them to depart when he thought good."Romanticism and later revivals