Donald Keyhoe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Donald Edward Keyhoe (June 20, 1897 – November 29, 1988) was an American Marine Corps

galenet.galegroup.com

Fee via

naval aviator

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier. Carrier-based a ...

,

Donald E(dward) Keyhoe. (April 30, 1998) Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2002. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009galenet.galegroup.com

Fee via

Fairfax County Public Library

The Fairfax County Public Library (FCPL) is a public library system headquartered in Suite 324 of The Fairfax County Government Center in unincorporated Fairfax County, Virginia, United States.

Hennen's American Public Library Ratings ...

. Document number: H1000053777. writer of aviation articles and stories in a variety of publications, and tour manager of aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

.

In the 1950s, Keyhoe became a UFO

An unidentified flying object (UFO), more recently renamed by US officials as a UAP (unidentified aerial phenomenon), is any perceived aerial phenomenon that cannot be immediately identified or explained. On investigation, most UFOs are id ...

researcher and writer, arguing that the U.S. government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

should conduct research into UFO matters, and should publicly release all its UFO files.

Early life and career

Keyhoe was born and raised inOttumwa, Iowa

Ottumwa ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Wapello County, Iowa, United States. The population was 25,529 at the time of the 2020 U.S. Census. Located in the state's southeastern section, the city is split into northern and southern halves b ...

. Upon receiving his B.S.

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

degree from the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

in 1919, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

.

In 1922, his arm was injured during an airplane crash in Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

. During his long convalescence

Convalescence is the gradual recovery of health and strength after illness or injury. It refers to the later stage of an infectious disease or illness when the patient recovers and returns to previous health, but may continue to be a source of ...

, Keyhoe began writing as a hobby. He eventually returned to active duty, but the injury gave Keyhoe persistent trouble, and, as a result, he resigned from the Marines in 1923. He then worked for the National Geodetic Survey

The National Geodetic Survey (NGS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, United States federal agency that defines and manages a national coordinate system, providing the foundation for transportation and communication; mapping an ...

and U.S. Department of Commerce

The United States Department of Commerce is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government concerned with creating the conditions for economic growth ...

.

In 1927, Keyhoe managed a coast-to-coast tour by Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

. This led to Keyhoe's first book, 1928's ''Flying With Lindbergh''. The book was a success, and led to a freelance writing career, with Keyhoe's articles and fictional stories (mostly related to aviation) appearing in a variety of publications.

Keyhoe returned to active duty during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in a Naval Aviation Training Division before retiring again at the rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

.

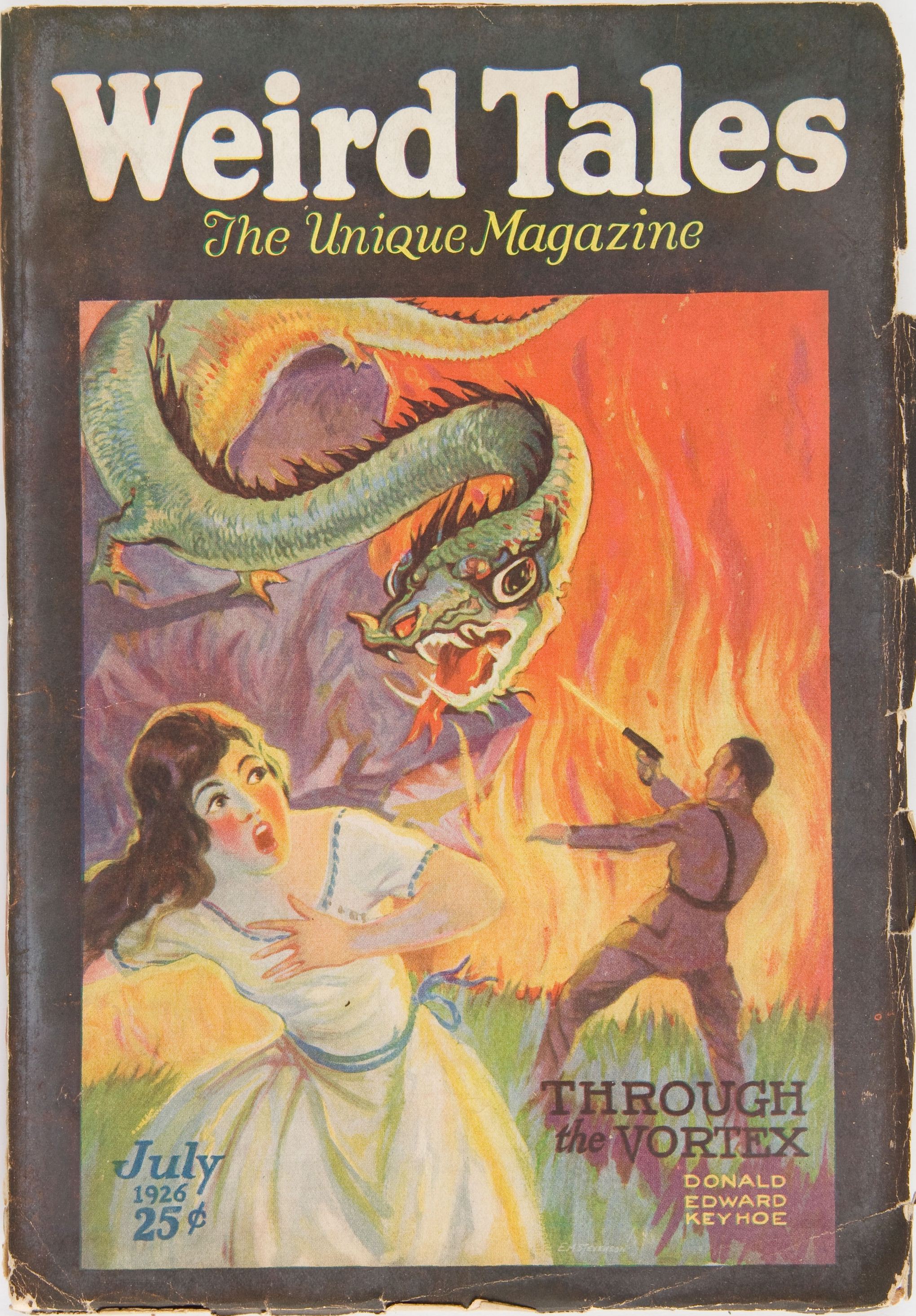

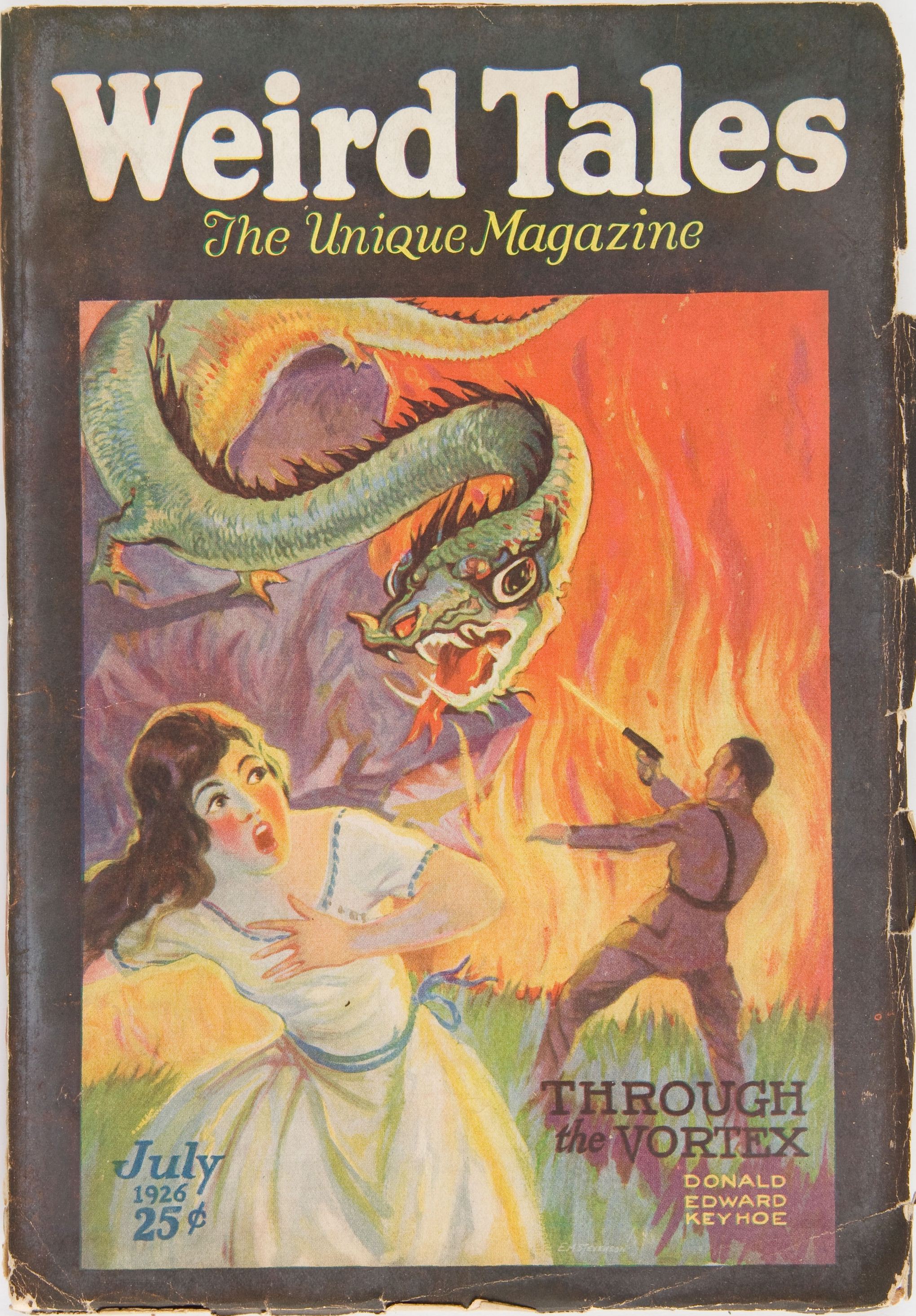

Writing for the pulps and glossies

By the time his UFO books appeared, Keyhoe was already an established author, with stories in the pulp magazines of the 1920s and 1930s. Four of his short stories were printed in '' Weird Tales'': "The Grim Passenger" (1925), "The Mystery Under the Sea" (1926), "Through the Vortex" (1926) and "The Master of Doom" (1927). He also produced the lead novel for all three issues of a short-lived magazine ''Dr. Yen Sin

''Dr. Yen Sin'' was a short-lived pulp science fiction magazine published by the New York City-based Popular Publications during 1936. It superseded a similar magazine from the same publishers entitled '' The Mysterious Wu Fang'', which had ceas ...

'': "The Mystery of the Dragon's Shadow" (May/June 1936), "The Mystery of the Golden Skull" (July/August 1936) and "The Mystery of the Singing Mummies" (September/October 1936). The Doctor was opposed by a hero who could not sleep.

Keyhoe wrote a number of air adventure stories for '' Flying Aces'', and other magazines, and created two larger-than-life superhero

A superhero or superheroine is a stock character that typically possesses ''superpowers'', abilities beyond those of ordinary people, and fits the role of the hero, typically using his or her powers to help the world become a better place, ...

es in this genre. The first of these was Captain Philip Strange, referred to as "the Brain Devil" and "the Phantom Ace of G-2." Captain Strange was an American intelligence officer during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

who was gifted with ESP

ESP most commonly refers to:

* Extrasensory perception, a paranormal ability

ESP may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment Music

* ESP Guitars, a manufacturer of electric guitars

* E.S. Posthumus, an independent music group formed in 2000, ...

and other mental powers. His existence has been perpetuated beyond Keyhoe's stories as a minor member of the Wold Newton universe.

Keyhoe's other "superpowered" flying ace was Richard Knight, a World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

veteran who was blinded in combat but gained a supernatural ability to see in the dark. Knight featured in a number of adventure stories.

Other series he wrote included the "Eric Trent" series in ''Flying Aces'' and the "Vanished Legion" in ''Dare-Devil Aces'', and two long-running series: "The Devildog Squadron" in ''Sky Birds'' and "The Jailbird Flight" in ''Battle Aces''.

Many of Keyhoe's stories for the pulps were science fiction or Weird Fantasy, or contained a significant measure of these elements — a fact that was not lost on later critics of his UFO books.p. 188

He was also a freelancer

''Freelance'' (sometimes spelled ''free-lance'' or ''free lance''), ''freelancer'', or ''freelance worker'', are terms commonly used for a person who is self-employed and not necessarily committed to a particular employer long-term. Freelance w ...

for ''Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

'', ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'', and '' Reader's Digest''.

The Flying Saucers Are Real

Interest in UFO's broke out across the United States following pilotKenneth Arnold

Kenneth Albert Arnold (March 29, 1915 – January 16, 1984) was an American aviator, businessman, and politician.

He is best known for making what is generally considered the first widely reported modern unidentified flying object sighting in ...

's report of odd, fast-moving aerial objects in Washington State

Washington (), officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. Named for George Washington—the first U.S. president—the state was formed from the western part of the Washington ...

during the summer of 1947. Keyhoe began to follow the subject with some interest, though he was initially skeptical of any extraordinary answer to the UFO question. For some time, ''True

True most commonly refers to truth, the state of being in congruence with fact or reality.

True may also refer to:

Places

* True, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* True, Wisconsin, a town in the United States

* Tr ...

'' (a popular American men's magazine) had been inquiring of officials as to the flying saucer question, with little to show for their efforts. In the spring of 1949, after the U.S. Air Force had released contradictory information about the saucers, editor Ken Purdy turned to Keyhoe, who had written for the magazine, but who also had friends and contacts in the military and the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

.

As their forms, flight maneuvers, speeds and light technology was apparently far ahead of any nation's developments, Keyhoe became convinced that they must be the products of unearthly intelligences, and that the U.S. government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

was trying to suppress the whole truth about the subject. This conclusion was based especially on the response Keyhoe found when he quizzed various officials about flying saucers. He was told there was nothing to the subject, yet was simultaneously denied access to saucer-related documents.

Keyhoe's article "Flying Saucers Are Real" appeared in the January 1950 issue of ''True'' (published December 26, 1949) and caused a sensation. Though such figures are always difficult to verify, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Edward J. Ruppelt

Edward James Ruppelt (July 17, 1923 – September 15, 1960) was a United States Air Force officer probably best known for his involvement in Project Blue Book, a formal governmental study of unidentified flying objects (UFOs). He is generally ...

, the first head of Project Blue Book, reported that "It is rumored among magazine publishers that Don Keyhoe's article in ''True'' was one of the most widely read and widely discussed magazine articles in history."

Capitalizing on the interest, Keyhoe expanded the article into a book, '' The Flying Saucers Are Real'' (1950); it sold over half a million copies in paperback. He argued that the Air Force knew that flying saucers were extraterrestrial, but downplayed the reports to avoid public panic. In Keyhoe's view, the aliens — wherever their origins or intentions — did not seem hostile, and had likely been surveilling the earth for two hundred years or more, though Keyhoe wrote that their "observation suddenly increased in 1947, following the series of A-bomb explosions in 1945." Dr. Michael D. Swords

Michael D. Swords is a retired professor of Natural Science at Western Michigan University, who writes about general sciences and anomalous phenomena, particularly parapsychology, cryptozoology, and ufology, editing the academic publication ''The J ...

characterized the book as "a rather sensational but accurate account of the matter." (Swords, p. 100) Boucher and McComas praised it as "cogent, intelligent and persuasive."

Keyhoe wrote several more books about UFOs. '' Flying Saucers from Outer Space'' (Holt, 1953) was largely based on interviews and official reports vetted by the Air Force. The book included a blurb by Albert M. Chop Albert M. Chop (1916 – January 15, 2006) was a newspaper reporter, a public relations officer in the aerospace industry, and a founding member of NASA's public relations office who served as Deputy Public Relations Director. Under Chop's leadershi ...

, the Air Force's press secretary in the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

, who characterized Keyhoe as a "responsible, accurate reporter" and further expressed approval for Keyhoe's arguments in favor of the extraterrestrial hypothesis

The extraterrestrial hypothesis (ETH) proposes that some unidentified flying objects (UFOs) are best explained as being physical spacecraft occupied by extraterrestrial life or non-human aliens, or non-occupied alien probes from other planets vi ...

.

Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philo ...

argued that Keyhoe's first two books were "based on official material and studiously avoid the wild speculations, ''naivete'' or prejudice of other FOpublications."

The Flying Saucer Conspiracy

In 1955, Keyhoe authored ''The Flying Saucer Conspiracy

''The Flying Saucer Conspiracy'' is a 1955 book authored by early UFO researcher Donald Keyhoe. The book pointedly accused elements of United States government of engaging in a conspiracy to cover up knowledge of flying saucers. Keyhoe claims the ...

'', which pointedly accused elements of United States government of engaging in a conspiracy to cover up knowledge of flying saucers. Keyhoe claims the existence of a "silence group" of orchestrating this conspiracy.Peebles, p. 111-113 Historian of folklore Curtis Peebles

Curtis Peebles (May 4, 1955 – June 25, 2017) was an American aerospace historian for the Smithsonian Institution, a researcher and historian for the Dryden Flight Research Center, and the author of several books dealing with aviation and aerial ...

argues: "''The Flying Saucer Conspiracy'' marked a shift in Keyhoe's belief system. No longer were flying saucers the central theme; that now belonged to the silence group and its coverup. For the next two decades Keyhoe's beliefs about this would dominate the flying saucer myth."

The book features claims of a possible discovery of an "orbiting space base" or a "moon base", knowledge of which might trigger a public panic. ''The Flying Saucer Conspiracy'' also incorporated legends of the Bermuda Triangle

The Bermuda Triangle, also known as the Devil's Triangle, is an urban legend focused on a loosely defined region in the western part of the North Atlantic Ocean where a number of aircraft and ships are said to have disappeared under mysterio ...

disappearances. Keyhoe sensationalized claims, ultimately stemming from optical illusions, of unusual structures on the moon.

The NICAP era

In 1956, Keyhoe cofounded the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena (NICAP). He was one of several prominent professional, military or scientific figures on the board of directors, which lent the group a degree of legitimacy many of the other contemporary "flying saucer clubs" sorely lacked. NICAP published a newsletter, ''The UFO Investigator'', which was mailed to its members. Although the newsletter was intended to be published on a regular monthly basis, due to financial problems it was often delivered on a more erratic basis. For example, in 1958 four issues were published, but only two issues were published in 1959.(Peebles, p. 162) NICAP founder Thomas Townsend Brown was ousted as director in early 1957 after facing repeated charges of financial ineptitude. Keyhoe replaced him; he was only slightly better at managing NICAP's finances, and the organization often faced financial shortfalls and crises throughout Keyhoe's twelve years as director. Even so, it would remain the largest and most influential civilian UFO research group in the United States from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. With Keyhoe in the lead, NICAP pressed hard for Congressional hearings and investigation into UFOs. They scored some attention from the mass media, and the general public (NICAP's membership peaked at about 15,000 during the early and mid-1960s) but only very limited interest from government officials. However, there was increasing criticism of the Air Force's Project Blue Book. Following a widely publicized wave of UFO reports in 1966, NICAP was among the chorus which called for an independent scientific investigation of UFOs. The Condon Committee was formed at the University of Colorado with this goal in mind, though it quickly became mired in infighting and later, in controversy. Keyhoe publicized the so-called "Trick Memo", an embarrassing memorandum written by the Condon Committee coordinator which seemed to suggest that the ostensibly objective and neutral committee had determined to pursue adebunking

{{Short pages monitor