Doc Edgerton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harold Eugene "Doc" Edgerton (April 6, 1903 – January 4, 1990), also known as Papa Flash, was an American scientist and researcher, a professor of electrical engineering at the

In 1925 Edgerton received a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the

In 1925 Edgerton received a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the

In 1937 Edgerton began a lifelong association with photographer

In 1937 Edgerton began a lifelong association with photographer

The Edgerton Digital Collections

website by the MIT Museum with thousands of photographs and scanned notebooks.

The Edgerton Center at MIT

– Early photographs from Edgerton's laboratory, including water from the tap, MIT Collections

Biographical timeline

*

The Edgerton Explorit Center in Aurora, NEThe SPIE Harold E. Edgerton Award

* * ttp://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/edgerton-harold.pdf National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir {{DEFAULTSORT:Edgerton, Doc 1903 births 1990 deaths Pioneers of photography People from Aurora, Nebraska People from Fremont, Nebraska University of Nebraska–Lincoln alumni MIT School of Engineering faculty MIT School of Engineering alumni National Medal of Science laureates National Medal of Technology recipients Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Howard N. Potts Medal recipients 20th-century American engineers 20th-century American photographers Engineers from Nebraska Photographers from Nebraska Members of the American Philosophical Society

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern t ...

. He is largely credited with transforming the stroboscope

A stroboscope, also known as a strobe, is an instrument used to make a cyclically moving object appear to be slow-moving, or stationary. It consists of either a rotating disk with slots or holes or a lamp such as a flashtube which produces b ...

from an obscure laboratory instrument into a common device. He also was deeply involved with the development of sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects on ...

and deep-sea photography, and his equipment was used by Jacques Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful Aqua-Lung, open-circuit SCUBA (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus). Th ...

in searches for shipwrecks and even the Loch Ness Monster

The Loch Ness Monster ( gd, Uilebheist Loch Nis), affectionately known as Nessie, is a creature in Scottish folklore that is said to inhabit Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands. It is often described as large, long-necked, and with one or m ...

.

Biography

Early years

Edgerton was born inFremont, Nebraska

Fremont is a city and county seat of Dodge County in the eastern portion of the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. The population was 27,141 at the 2020 census. Fremont is the home of Midland University.

History

From the 183 ...

, on April 6, 1903, the son of Mary Nettie Coe and Frank Eugene Edgerton, a descendant of Samuel Edgerton, the son of Richard Edgerton, one of the founders of Norwich, Connecticut

Norwich ( ) (also called "The Rose of New England") is a city in New London County, Connecticut

New London County is in the southeastern corner of Connecticut and comprises the Norwich-New London, Connecticut Metropolitan Statistical Area, ...

and Alice Ripley, a great-granddaughter of Governor William Bradford

William Bradford ( 19 March 15909 May 1657) was an English Puritan separatist originally from the West Riding of Yorkshire in Northern England. He moved to Leiden in Holland in order to escape persecution from King James I of England, and th ...

(1590–1657) of the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

and a passenger on the Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

. His father was a lawyer, journalist, author and orator and served as the assistant attorney general of Nebraska from 1911 to 1915. Edgerton grew up in Aurora, Nebraska

Aurora is a city in Hamilton County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 4,479 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Hamilton County.

History

In 1861, David Millspaw became the first permanent settler in the area of what was to ...

. He also spent some of his childhood years in Washington, D.C., and Lincoln, Nebraska

Lincoln is the capital city of the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Lancaster County. The city covers with a population of 292,657 in 2021. It is the second-most populous city in Nebraska and the 73rd-largest in the United St ...

.

Education

In 1925 Edgerton received a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the

In 1925 Edgerton received a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

A university () is an educational institution, institution of higher education, higher (or Tertiary education, tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' ...

where he became a member of Acacia fraternity

Acacia Fraternity, Inc. is a social fraternity founded in 1904 at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The fraternity has 27 active chapters and 3 associate chapters throughout Canada and the United States. The fraternit ...

. He earned an SM in electrical engineering from MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

in 1927. Edgerton used stroboscopes to study synchronous motors for his Sc.D.

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

thesis in electrical engineering at MIT, awarded in 1931. He credited Charles Stark Draper

Charles Stark "Doc" Draper (October 2, 1901 – July 25, 1987) was an American scientist and engineer, known as the "father of inertial navigation". He was the founder and director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Instrumen ...

with inspiring him to photograph everyday objects using electronic flash; the first was a stream of water from a faucet.

In 1936 Edgerton visited hummingbird expert May Rogers Webster

May Rogers Webster (May 23, 1873 – January 7, 1938) was an American naturalist active in New Hampshire, especially known for her knack of taming hummingbirds, but also for starting environmental education programs in that state.

Early life

Alic ...

. He was able to illustrate with her help that it was possible to take photographs of the birds beating their wings 60 times a second using an exposure of one hundred thousandth of a second. A picture of her with the birds flying around her appeared in National Geographic.

Career

In 1937 Edgerton began a lifelong association with photographer

In 1937 Edgerton began a lifelong association with photographer Gjon Mili

Gjon Mili (November 28, 1904 – February 14, 1984) was an Albanian photographer from Korçë who developed his profession in America, best known for his work published in ''Life'', in which he photographed artists such as Pablo Picasso.

Biogr ...

, who used stroboscopic equipment, in particular, multiple studio electronic flash units, to produce strikingly beautiful photographs, many of which appeared in Life Magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

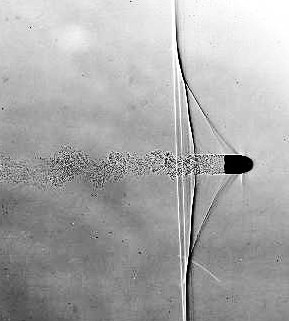

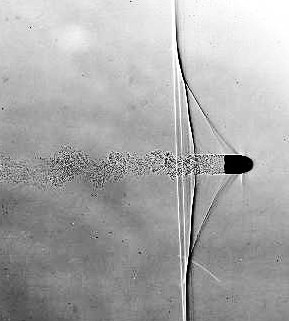

. When taking multiflash photographs this strobe light equipment could flash up to 120 times a second. Edgerton was a pioneer in using short duration electronic flash in photographing fast events photography, subsequently using the technique to capture images of balloons at different stages of their bursting, a bullet during its impact with an apple, or using multiflash to track the motion of a devil stick

The manipulation of the devil stick (also devil-sticks, devilsticks, flower sticks, stunt sticks, gravity sticks, or juggling sticks) is a form of gyroscopic juggling or equilibristics, consisting of manipulating one stick ("baton", 'center s ...

, for example. He was awarded a bronze medal by the Royal Photographic Society

The Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, commonly known as the Royal Photographic Society (RPS), is one of the world's oldest photographic societies. It was founded in London, England, in 1853 as the Photographic Society of London with ...

in 1934, the Howard N. Potts Medal

The Howard N. Potts Medal was one of The Franklin Institute Awards for science and engineering award presented by the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named for Howard N. Potts. The first Howard N. Potts Medal was awarded in ...

from the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memor ...

in 1941, the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet o ...

in 1966, the David Richardson Medal

The David Richardson Medal is awarded by the Optical Society (formerly the Optical Society of America) to recognize contributions to optical engineering, primarily in the commercial and industrial sector. The award was first made in 1966 to its nam ...

by the Optical Society of America

Optica (formerly known as The Optical Society (OSA) and before that as the Optical Society of America) is a professional society of individuals and companies with an interest in optics and photonics. It publishes journals and organizes conferenc ...

in 1968, the Albert A. Michelson Medal

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memo ...

from the same Franklin Institute in 1969, and the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

in 1973.

Edgerton partnered with Kenneth J. Germeshausen to do consulting for industrial clients. Later Herbert Grier joined them. The company name "Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier" was changed to EG&G

EG&G, formally known as Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier, Inc., was a United States national defense contractor and provider of management and technical services. The company was involved in contracting services to the United States governmen ...

in 1947. EG&G became a prime contractor for the Atomic Energy Commission and had a major role in photographing and recording nuclear tests for the US through the fifties and sixties. For this role Edgerton and Charles Wykoff and others at EG&G developed and manufactured the Rapatronic camera

The rapatronic camera (a portmanteau of ''rap''id ''a''ction elec''tronic'') is a high-speed camera capable of recording a still image with an exposure time as brief as 10 nanoseconds.

The camera was developed by Harold Edgerton in the 1940s ...

.

His work was instrumental in the development of side-scan sonar

Side-scan sonar (also sometimes called side scan sonar, sidescan sonar, side imaging sonar, side-imaging sonar and bottom classification sonar) is a category of sonar system that is used to efficiently create an image of large areas of the sea ...

technology, used to scan the sea floor for wrecks. Edgerton worked with undersea explorer Jacques Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful Aqua-Lung, open-circuit SCUBA (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus). Th ...

, by first providing him with custom-designed underwater photographic equipment featuring electronic flash, and then by developing sonar techniques used to discover the Britannic

Britannic means 'of Britain' or 'British', from the Roman name for the British.

Britannic may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Britannic'' (film), a 2000 film based on the story of HMHS ''Britannic''

* SS ''Britannic'', a fictional ...

. Edgerton participated in the discovery of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

battleship USS Monitor

USS ''Monitor'' was an ironclad warship built for the Union Navy during the American Civil War and completed in early 1862, the first such ship commissioned by the Navy. ''Monitor'' played a central role in the Battle of Hampton Roads on 9 Ma ...

. While working with Cousteau, he acquired the nickname in photographic circles: "Papa Flash". In 1988 Doc Edgerton worked with Paul Kronfield in Greece on a sonar search for the lost city of Helike, believed to be the basis for the legend of Atlantis.

Edgerton co-founded EG&G, Inc., which manufactured advanced electronic equipment including side-scan sonars, subbottom profiling equipment. EG&G also invented and manufactured the Krytron

The krytron is a cold-cathode gas-filled tube intended for use as a very high-speed switch, somewhat similar to the thyratron. It consists of a sealed glass tube with four electrodes. A small triggering pulse on the grid electrode switches the tu ...

, the detonation device for the hydrogen bomb, and an EG&G division supervised many of America's nuclear tests.

In addition to having the scientific and engineering acumen to perfect strobe light

A strobe light or stroboscopic lamp, commonly called a strobe, is a device used to produce regular flashes of light. It is one of a number of devices that can be used as a stroboscope. The word originated from the Ancient Greek ('), meaning ...

ing commercially, Edgerton is equally recognized for his visual aesthetic: many of the striking images he created in illuminating phenomena that occurred too fast for the naked eye adorn art museums worldwide. In 1940, his high speed stroboscopic short film '' Quicker'n a Wink'' won an Oscar

Oscar, OSCAR, or The Oscar may refer to:

People

* Oscar (given name), an Irish- and English-language name also used in other languages; the article includes the names Oskar, Oskari, Oszkár, Óscar, and other forms.

* Oscar (Irish mythology), ...

.

Edgerton was appointed a professor of electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1934. In 1956, Edgerton was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, ...

. He became a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

in 1964 and a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

in 1972. He was especially loved by MIT students for his willingness to teach and his kindness: "The trick to education", he said, "is to teach people in such a way that they don't realize they're learning until it's too late". His last undergraduate class, taught during fall semester 1977, was a freshman seminar titled "Bird and Insect Photography". One of the graduate student dormitories at MIT carries his name.

In 1962, Edgerton appeared on ''I've Got a Secret

''I've Got a Secret'' is an American panel game show produced by Mark Goodson and Bill Todman for CBS television. Created by comedy writers Allan Sherman and Howard Merrill, it was a derivative of Goodson-Todman's own panel show, ''What's My L ...

'', where he demonstrated strobe flash photography by shooting a bullet into a playing card and photographing the result.

Edgerton's work was featured in an October 1987 ''National Geographic Magazine

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widel ...

'' article entitled "Doc Edgerton: the man who made time stand still".

Family

After graduating from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Edgerton married Esther May Garrett in 1928. She was born inAurora, Nebraska

Aurora is a city in Hamilton County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 4,479 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Hamilton County.

History

In 1861, David Millspaw became the first permanent settler in the area of what was to ...

on September 8, 1903 and died on March 9, 2002 in Charleston, South Carolina. She received a bachelor's degree in mathematics, music and education from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. A skilled pianist and singer, she attended the New England Conservatory of Music

The New England Conservatory of Music (NEC) is a private music school in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest independent music conservatory in the United States and among the most prestigious in the world. The conservatory is located on ...

and taught in public schools in Aurora, Nebraska and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

. During their marriage they had three children: Mary Louise (April 21, 1931), William Eugene (8/9/1933), Robert Frank (5/10/1935). His sister, Mary Ellen Edgerton, was the wife of L. Welch Pogue

Lloyd Welch Pogue (October 21, 1899 – May 10, 2003) was an American aviation attorney and chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board.

Early life and education

Pogue was born in Grant, Iowa on October 21, 1899, the son of Leander Welch Pogue and ...

(1899–2003) a pioneering aviation attorney and Chairman of the old Civil Aeronautics Board

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) was an agency of the federal government of the United States, formed in 1938 and abolished in 1985, that regulated aviation services including scheduled passenger airline serviceStringer, David H."Non-Skeds: ...

. David Pogue

David Welch Pogue (born March 9, 1963) is an American technology and science writer and TV presenter. He is an Emmy-winning correspondent for '' CBS News Sunday Morning'' and author of the "Crowdwise" column in ''The New York Times'' Smarter Liv ...

, a technology writer, journalist and commentator, is his great nephew.

Death

Edgerton remained active throughout his later years, and was seen on the MIT campus many times after his official retirement. He died suddenly on January 4, 1990 at the MIT Faculty Club at the age of 86, and is buried inMount Auburn Cemetery

Mount Auburn Cemetery is the first rural, or garden, cemetery in the United States, located on the line between Cambridge and Watertown in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, west of Boston. It is the burial site of many prominent Boston Brahmi ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

, Massachusetts.

Legacy

On July 3, 1990, in an effort to memorialize Edgerton's accomplishments, several community members inAurora, Nebraska

Aurora is a city in Hamilton County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 4,479 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Hamilton County.

History

In 1861, David Millspaw became the first permanent settler in the area of what was to ...

decided to construct a "Hands-On" science center. It was designated as a "teaching museum," that would preserve Doc's work and artifacts, as well as feature the "Explorit Zone" where people of all ages could participate in hands-on exhibits and interact with live science demonstrations. After five years of private and community-wide fund-raising, as well as individual investments by Doc's surviving family members, the Edgerton Explorit Center was officially dedicated on September 9, 1995 in Aurora.

At MIT, the Edgerton Center, founded in 1992, is a hands-on laboratory resource for undergraduate and graduate students, and also conducts educational outreach programs for high school students and teachers.

Works

*''Flash! Seeing the Unseen by Ultra High-Speed Photography'' (1939, withJames R. Killian Jr.

James Rhyne Killian Jr. (July 24, 1904 – January 29, 1988) was the 10th president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, from 1948 until 1959.

Early life

Killian was born on July 24, 1904, in Blacksburg, South Carolina. His father w ...

). Boston: Hale, Cushman & Flint.

*''Electronic Flash, Strobe'' (1970). New York: McGraw-Hill.

*''Moments of Vision'' (1979, with Mr. Killian). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT.

*''Sonar Images'' (1986, with Mr. Killian). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

*''Stopping Time'', a collection of his photographs, (1987). New York: H.N. Abrams.

Photographs

Some of Edgerton's noted photographs are : *''Milk Drop Coronet'' (1935) *''Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds are birds native to the Americas and comprise the Family (biology), biological family Trochilidae. With about 361 species and 113 genus, genera, they occur from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, but the vast majority of the species are ...

'' (1936)

*''Football Kick'' (1938)

* ''Gussie Moran

Gertrude Augusta "Gussie" Moran (September 8, 1923 – January 16, 2013) was an American tennis player who was active in the late 1940s and 1950s. Her highest US national tennis ranking was 4th. She was born in Santa Monica, California and died i ...

's Tennis Swing'' (1949)

*''Diver'' (1955)

*''Cranberry Juice into Milk'' (1960)

*''Moscow Circus'' (1963)

*''Bullet Through Banana'' (1964)

*''.30 Bullet Piercing an Apple'' (1964)

*''Cutting the Card Quickly'' (1964)

*''Pigeon Release'' (1965)

*''Bullet Through Candle Flame'' (1973) (with Kim Vandiver)

Exhibitions

*''Flashes of Inspiration: The Work of Harold Edgerton,'' Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2009. *''Seeing the Unseen: The High Speed Photography of Dr. Harold Edgerton,''Ikon Gallery

The Ikon Gallery () is an English gallery of contemporary art, located in Brindleyplace, Birmingham. It is housed in the Grade II listed, neo-gothic former Oozells Street Board School, designed by John Henry Chamberlain in 1877.

Ikon was set ...

, Birmingham, January 1976; then toured to The Photographers' Gallery

The Photographers' Gallery was founded in London by Sue Davies opening on 14 January 1971, as the first public gallery in the United Kingdom devoted solely to photography.

It is also home to the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize, established i ...

, London; Hatton Gallery

The Hatton Gallery is Newcastle University's art gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. It is based in the University's Fine Art Building.

The Hatton Gallery briefly closed in February 2016 for a £3.8 million redevelopment and reopened in ...

, Newcastle University; Midland Group

The Midland Group is an international trading and investment holding company. Registered in Guernsey under the name Midland Resources Holding Ltd, the group owns a number of subsidiaries across the agriculture, manufacturing, real estate, shippi ...

Gallery, Nottingham; Modern Art Oxford

Modern Art Oxford is an art gallery established in 1965 in Oxford, England. From 1965 to 2002, it was called The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford.

The gallery presents exhibitions of modern and contemporary art. It has a national and internationa ...

; and Arnolfini

Arnolfini is an international arts centre and gallery in Bristol, England. It has a programme of contemporary art exhibitions, artist's performance, music and dance events, poetry and book readings, talks, lectures and cinema. There is also a ...

, Bristol. Curated by John Myers and Geoffrey Holt.

*''Seeing the Unseen: Photographs and films by Harold E. Edgerton,'' The Pallasades Shopping Centre, Birmingham. A repeat organised by Ikon Gallery of the previous exhibition.

Collections

Edgerton's work is held in the following public collection: *Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street (Manhattan), 53rd Street between Fifth Avenue, Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, ...

, New York City: 29 prints (as of July 2018)

*International Photography Hall of Fame

The International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum in St. Louis, Missouri honors those who have made great contributions to the field of photography.

History

In 1977 the first Hall of Fame and Museum opened in Santa Barbara, California and a f ...

, St.Louis, MO

See also

*Air-gap flash

An air-gap flash is a photographic light source capable of producing sub-microsecond light flashes, allowing for (ultra) high-speed photography. This is achieved by a high-voltage (20 kV typically) electric discharge between two electrodes ov ...

References

Further reading

* Bruce, Roger R. (editor); Collins, Douglas, et al., ''Seeing the unseen : Dr. Harold E. Edgerton and the wonders of Strobe Alley'', Rochester, N.Y. : Pub. Trust of George Eastman House ; Cambridge, Massachusetts : Distributed by MIT Press, 1994. *PBS ''Nova'' series: "Edgerton and His Incredible Seeing Machines". NOVA explores the fascinating world of Dr. Harold Edgerton, electronics wizard and inventor extraordinaire, whose invention of the electronic strobe, a "magic lamp," has enabled the human eye to see the unseen." Original broadcast date: 01/15/85External links

The Edgerton Digital Collections

website by the MIT Museum with thousands of photographs and scanned notebooks.

The Edgerton Center at MIT

– Early photographs from Edgerton's laboratory, including water from the tap, MIT Collections

Biographical timeline

*

The Edgerton Explorit Center in Aurora, NE

* * ttp://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/edgerton-harold.pdf National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir {{DEFAULTSORT:Edgerton, Doc 1903 births 1990 deaths Pioneers of photography People from Aurora, Nebraska People from Fremont, Nebraska University of Nebraska–Lincoln alumni MIT School of Engineering faculty MIT School of Engineering alumni National Medal of Science laureates National Medal of Technology recipients Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Howard N. Potts Medal recipients 20th-century American engineers 20th-century American photographers Engineers from Nebraska Photographers from Nebraska Members of the American Philosophical Society