Detective Story on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Detective fiction is a subgenre of

Detective fiction is a subgenre of

Detective fiction is a subgenre of

Detective fiction is a subgenre of crime fiction

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

and mystery fiction

Mystery is a genre fiction, fiction genre where the nature of an event, usually a murder or other crime, remains wiktionary:mysterious, mysterious until the end of the story. Often within a closed circle of suspects, each suspect is usually prov ...

in which an investigator or a detective

A detective is an investigator, usually a member of a law enforcement agency. They often collect information to solve crimes by talking to witnesses and informants, collecting physical evidence, or searching records in databases. This leads th ...

ŌĆöwhether professional, amateur or retiredŌĆöinvestigates a crime, often murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

. The detective genre began around the same time as speculative fiction

Speculative fiction is a term that has been used with a variety of (sometimes contradictory) meanings. The broadest interpretation is as a category of fiction encompassing genres with elements that do not exist in reality, recorded history, na ...

and other genre fiction

Genre fiction, also known as popular fiction, is a term used in the book-trade for fictional works written with the intent of fitting into a specific literary genre, in order to appeal to readers and fans already familiar with that genre.

A num ...

in the mid-nineteenth century and has remained extremely popular, particularly in novels. Some of the most famous heroes of detective fiction include C. Auguste Dupin

''Le Knight, Chevalier'' C. Auguste Dupin is a fictional character created by Edgar Allan Poe. Dupin made his first appearance in Poe's 1841 short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", widely considered the first detective fiction story. He rea ...

, Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

, and Hercule Poirot

Hercule Poirot (, ) is a fictional Belgian detective created by British writer Agatha Christie. Poirot is one of Christie's most famous and long-running characters, appearing in 33 novels, two plays ('' Black Coffee'' and ''Alibi''), and more ...

. Juvenile stories featuring The Hardy Boys

The Hardy Boys, brothers Frank and Joe Hardy, are fictional characters who appear in several mystery series for children and teens. The series revolves around teenagers who are amateur sleuths, solving cases that stumped their adult counterpa ...

, Nancy Drew

Nancy Drew is a Fictional character, fictional character appearing in several Mystery fiction, mystery book series, movies, and a TV show as a teenage amateur sleuth. The books are ghostwriter, ghostwritten by a number of authors and published ...

, and The Boxcar Children have also remained in print for several decades.

History

Ancient

Some scholars, such as R. H. Pfeiffer, have suggested that certain ancient and religious texts bear similarities to what would later be called detective fiction. In the Old Testament story ofSusanna and the Elders

Susanna (; : "lily"), also called Susanna and the Elders, is a narrative included in the Book of Daniel (as chapter 13) by the Catholic Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches and Eastern Orthodox Churches. It is one of the additions to Daniel, plac ...

(the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

locates this story within the apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ß╝ĆŽĆŽī╬║ŽüŽģŽå╬┐Žé) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

), the account told by two witnesses broke down when Daniel

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. GabrielŌĆö"God is my strength" ...

cross-examines them. In response, author Julian Symons

Julian Gustave Symons (originally Gustave Julian Symons) (pronounced ''SIMM-ons''; 30 May 1912 ŌĆō 19 November 1994) was a British crime writer and poet. He also wrote social and military history, biography and studies of literature. He was bor ...

has argued that "those who search for fragments of detection in the Bible and Herodotus are looking only for puzzles" and that these puzzles are not detective stories. In the play ''Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, ╬¤ß╝░╬┤╬»ŽĆ╬┐ŽģŽé ╬żŽŹŽü╬▒╬Į╬Į╬┐Žé, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'' by Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

playwright Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, ╬Ż╬┐Žå╬┐╬║╬╗ß┐åŽé, , Sophoklß╗ģs; 497/6 ŌĆō winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or co ...

, Oedipus

Oedipus (, ; grc-gre, ╬¤ß╝░╬┤╬»ŽĆ╬┐ŽģŽé "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby ...

investigates the unsolved murder of King Laius and discovers the truth after questioning various witnesses that he himself is the culprit. Although "Oedipus's enquiry is based on supernatural, pre-rational methods that are evident in most narratives of crime until the development of Enlightenment thought in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries", this narrative has "all of the central characteristics and formal elements of the detective story, including a mystery surrounding a murder, a closed circle of suspects, and the gradual uncovering of a hidden past."

Early Arabic

The ''One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, žŻ┘Ä┘ä┘Æ┘ü┘Å ┘ä┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æ┘ä┘Äž®┘Ź ┘ł┘Ä┘ä┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æ┘ä┘Äž®┘ī, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' contains several of the earliest detective stories, anticipating modern detective fiction. The oldest known example of a detective story was "The Three Apples The Three Apples ( ar, ž¦┘䞬┘üž¦žŁž¦ž¬ ž¦┘äž½┘䞦ž½ž®), or The Tale of the Murdered Woman ( ar, žŁ┘āž¦┘Ŗž® ž¦┘䞥ž©┘Ŗž® ž¦┘ä┘ģ┘鞬┘ł┘äž®, Hikayat as-Sabiyya al-Maqtula), is a story contained in the ''One Thousand and One Nights'' collection (also k ...

", one of the tales narrated by Scheherazade

Scheherazade () is a major female character and the storyteller in the frame narrative of the Middle Eastern collection of tales known as the ''One Thousand and One Nights''.

Name

According to modern scholarship, the name ''Scheherazade'' deri ...

in the ''One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, žŻ┘Ä┘ä┘Æ┘ü┘Å ┘ä┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æ┘ä┘Äž®┘Ź ┘ł┘Ä┘ä┘Ä┘Ŗ┘Æ┘ä┘Äž®┘ī, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' (''Arabian Nights''). In this story, a fisherman discovers a heavy, locked chest along the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

river, which he then sells to the Abbasid Caliph

The Abbasid caliphs were the holders of the Islamic title of caliph who were members of the Abbasid dynasty, a branch of the Quraysh tribe descended from the uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib.

The family came t ...

, Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, žŻž©┘ł ž¼ž╣┘üž▒ ┘枦ž▒┘ł┘å ž¦ž©┘å ┘ģžŁ┘ģž» ž¦┘ä┘ģ┘ćž»┘Ŗ) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 ŌĆō 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, ┘ć┘Äž¦ž▒┘Å┘ł┘å ž¦┘äž▒┘Äž┤┘É┘Ŗž», translit=H─ür┼½n ...

. When Harun breaks open the chest, he discovers the body of a young woman who has been cut into pieces. Harun then orders his vizier

A vizier (; ar, ┘łž▓┘Ŗž▒, waz─½r; fa, ┘łž▓█īž▒, vaz─½r), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

, Ja'far ibn Yahya

Jafar ibn Yahya Barmaki, Jafar al-Barmaki ( fa, ž¼ž╣┘üž▒ ž©┘å █īžŁ█ī█ī ž©ž▒┘ģ┌®█ī, ar, ž¼ž╣┘üž▒ ž©┘å ┘ŖžŁ┘Ŗ┘ē, Jafar bin yaßĖźy─ü) (767ŌĆō803) also called Aba-Fadl, was a Persian vizier of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, succeeding his father ...

, to solve the crime and to find the murderer within three days, or be executed if he fails in his assignment. Suspense

Suspense is a state of mental uncertainty, anxiety, being undecided, or being doubtful. In a dramatic work, suspense is the anticipation of the outcome of a plot or of the solution to an uncertainty, puzzle, or mystery, particularly as it aff ...

is generated through multiple plot twist

A plot twist is a literary technique that introduces a radical change in the direction or expected outcome of the plot in a work of fiction. When it happens near the end of a story, it is known as a twist or surprise ending. It may change the aud ...

s that occur as the story progressed. With these characteristics this may be considered an archetype for detective fiction. It anticipates the use of reverse chronology

Reverse chronology is a narrative structure and method of storytelling whereby the Plot (narrative), plot is revealed in reverse order.

In a story employing this technique, the first Scene (fiction), scene shown is actually the conclusion to the ...

in modern detective fiction, where the story begins with a crime before presenting a gradual reconstruction of the past.

The main difference between Ja'far ("The Three Apples") and later fictional detectives, such as Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

and Hercule Poirot

Hercule Poirot (, ) is a fictional Belgian detective created by British writer Agatha Christie. Poirot is one of Christie's most famous and long-running characters, appearing in 33 novels, two plays ('' Black Coffee'' and ''Alibi''), and more ...

, is that Ja'far has no actual desire to solve the case. The whodunit

A ''whodunit'' or ''whodunnit'' (a colloquial elision of "Who asdone it?") is a complex plot-driven variety of detective fiction in which the puzzle regarding who committed the crime is the main focus. The reader or viewer is provided with the cl ...

mystery is solved when the murderer himself confessed his crime. This in turn leads to another assignment in which Ja'far has to find the culprit who instigated the murder within three days or else be executed. Ja'far again fails to find the culprit before the deadline, but owing to chance, he discovers a key item. In the end, he manages to solve the case through reasoning in order to prevent his own execution.

On the other hand, two other ''Arabian Nights'' stories, "The Merchant and the Thief" and "Ali Khwaja", contain two of the earliest fictional detectives

Fictional detectives are characters in detective fiction. These individuals have long been a staple of detective mystery crime fiction, particularly in detective novels and short stories. Much of early detective fiction was written during the "Go ...

, who uncover clues and present evidence to catch or convict a criminal known to the audience, with the story unfolding in normal chronology and the criminal already known to the audience. The latter involves a climax where the titular detective protagonist Ali Khwaja presents evidence from expert witness

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as ...

es in a court.

Early Chinese

Gong'an fiction

''Gong'an'' or crime-case fiction () is a subgenre of Chinese crime fiction involving government magistrates who solve criminal cases. Gong'an fiction first appeared in the colloquial stories of Song dynasty. Gong'an fiction was then developed and ...

( Õģ¼µĪłÕ░ÅĶ»┤, literally’╝Ü"case records of a public law court") is the earliest known genre of Chinese detective fiction.

Some well-known stories include the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

story ''Circle of Chalk

''The Chalk Circle'' (sometimes translated ''The Circle of Chalk''), by Li Qianfu, is a Yuan dynasty (1259ŌĆō1368) Chinese classical zaju verse play and gong'an crime drama, in four acts with a prologue.ńü░ ķŚī Ķ©ś), the

One of the earliest examples of detective fiction in Western Literature is

One of the earliest examples of detective fiction in Western Literature is

Another early example of a whodunit is a subplot in the novel ''

Another early example of a whodunit is a subplot in the novel '' Dickens's prot├®g├®,

Dickens's prot├®g├®,  Although ''The Moonstone'' is usually seen as the first detective novel, there are other contenders for the honor. A number of critics suggest that the lesser known '' Notting Hill Mystery'' (1862ŌĆō63), written by the pseudonymous "Charles Felix" (later identified as

Although ''The Moonstone'' is usually seen as the first detective novel, there are other contenders for the honor. A number of critics suggest that the lesser known '' Notting Hill Mystery'' (1862ŌĆō63), written by the pseudonymous "Charles Felix" (later identified as

"The Case of the First Mystery Novelist"

in-print as "Before Hercule or Sherlock, There Was Ralph", ''

The period between World War I and World War II (the 1920s and 1930s) is generally referred to as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. During this period, a number of very popular writers emerged, including mostly British but also a notable subset of American and New Zealand writers. Female writers constituted a major portion of notable Golden Age writers.

The period between World War I and World War II (the 1920s and 1930s) is generally referred to as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. During this period, a number of very popular writers emerged, including mostly British but also a notable subset of American and New Zealand writers. Female writers constituted a major portion of notable Golden Age writers.

''Detective Fiction''

Polity. . By the late 1920s,

An exhibition of detective fiction

,

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

story collection ''Bao Gong An

Judge Bao (or Justice Bao (ÕīģķØÆÕż®)) stories in literature and performing arts are some of the most popular in traditional Chinese crime fiction ( ''gong'an'' fiction). All stories involve the Song dynasty minister Bao Zheng who solves, judges an ...

'' (Chinese: Õīģ Õģ¼ µĪł) and the 18th century '' Di Gong An'' (Chinese: ńŗä Õģ¼ µĪł) story collection. The latter was translated into English as ''Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee

''Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee'' (; lit. "Cases of Judge Dee"), also known as Di Gong An or Dee Goong An, is an 18th-century Chinese ''gong'an'' detective novel by an anonymous author, "Buti zhuanren" ( Chinese: õĖŹķóśµÆ░õ║║). It is loosely ba ...

'' by Dutch sinologist Robert Van Gulik

Robert Hans van Gulik (, 9 August 1910 ŌĆō 24 September 1967) was a Dutch orientalist, diplomat, musician (of the guqin), and writer, best known for the Judge Dee historical mysteries, the protagonist of which he borrowed from the 18th-century ...

, who then used the style and characters to write the original Judge Dee

Judge Dee, or Judge Di, is a semi-fictional character based on the historical figure Di Renjie, county magistrate and statesman of the Tang court. The character appeared in the 18th-century Chinese detective and '' gong'an'' crime novel ''Di Gong ...

series.

The hero/detective of these novels was typically a traditional judge or similar official based on historical personages such as Judge Bao

Judge Bao (or Justice Bao (ÕīģķØÆÕż®)) stories in literature and performing arts are some of the most popular in traditional Chinese crime fiction (gong'an fiction, ''gong'an'' fiction). All stories involve the Song dynasty minister Bao Zheng who s ...

( Bao Qingtian) or Judge Dee (Di Renjie

Di Renjie (630 ŌĆō November 11, 700), courtesy name Huaiying (µćĘĶŗ▒), formally Duke Wenhui of Liang (µóüµ¢ćµāĀÕģ¼), was a Chinese politician of Tang and Wu Zhou dynasties, twice serving as chancellor during the reign of Wu Zetian. He was one of ...

). Although the historical characters may have lived in an earlier period (such as the Song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetitio ...

or Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690ŌĆō705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

) most stories are written in the later Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

or Qing

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speaki ...

dynasty period.

These novels differ from the Western style tradition in several points as described by Van Gulik:

* The detective is the local magistrate who is usually involved in several unrelated cases simultaneously;

* The criminal is introduced at the very beginning of the story and his crime and reasons are carefully explained, thus constituting an inverted detective story

An inverted detective story, also known as a "howcatchem", is a murder mystery fiction structure in which the commission of the crime is shown or described at the beginning, usually including the identity of the perpetrator. The story then describ ...

rather than a "puzzle";

* The stories have a supernatural element with ghosts telling people about their death and even accusing the criminal;

* The stories are filled with digressions into philosophy, the complete texts of official documents, and much more, resulting in long books; and

* The novels tend to have a huge cast of characters, typically in the hundreds, all described with their relation to the various main actors in the story.

Van Gulik chose ''Di Gong An'' to translate because in his view it was closer to the Western literary style and more likely to appeal to non-Chinese readers.

A number of Gong An works may have been lost

Lost may refer to getting lost, or to:

Geography

*Lost, Aberdeenshire, a hamlet in Scotland

* Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail, or LOST, a hiking and cycling trail in Florida, US

History

*Abbreviation of lost work, any work which is known to have bee ...

or destroyed during the Literary Inquisitions and the wars

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

in ancient China. In the traditional Chinese culture, this genre was low-prestige, and therefore was less worthy of preservation than works such as philosophy or poetry. Only little or incomplete case volumes can be found; for example, the only copy of Di Gong An was found at a second-hand

Used goods mean any item of personal property offered for sale not as new, including metals in any form except coins that are legal tender, but excluding books, magazines, and postage stamps.

Risks

Furniture, in particular bedding or upholstere ...

book store in Tokyo, Japan.

Early Western

One of the earliest examples of detective fiction in Western Literature is

One of the earliest examples of detective fiction in Western Literature is Voltaire

Fran├¦ois-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

's ''Zadig

''Zadig; or, The Book of Fate'' (french: Zadig ou la Destin├®e; 1747) is a novella and work of philosophical fiction by the Enlightenment writer Voltaire. It tells the story of Zadig, a Zoroastrian philosopher in ancient Babylonia. The story ...

'' (1748), which features a main character who performs feats of analysis. ''Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams

''Things as They Are; or The Adventures of Caleb Williams'' (1794; retitled ''The Adventures of Caleb Williams; or Things as They Are'' in 1831, and often abbreviated to ''Caleb Williams'') by William Godwin is a three-volume novel written as ...

'' (1794) by William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 ŌĆō 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous for ...

portrays the law as protecting the murderer and destroying the innocent. Thomas Skinner Sturr's anonymous ''Richmond, or stories in the life of a Bow Street officer'' was published in London in 1827; the Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

crime story ''The Rector of Veilbye

''The Rector of Veilbye'' ( da, Pr├”sten i Vejlbye), is a crime mystery written in 1829 by the Danish author Steen Steensen Blicher. The novella is based upon a true murder case from 1626 in the village of Vejlby near Gren├ź, Denmark, which ...

'' by Steen Steensen Blicher

Steen Steensen Blicher (11 October 1782, Vium ŌĆō 26 March 1848 in Spentrup) was an author and poet born in Vium near Viborg, Denmark.

Biography

Blicher was the son of a literarily inclined Jutlandic parson whose family was distantly rela ...

was written in 1829; and the Norwegian crime novel ''Mordet paa Maskinbygger Roolfsen'' ("The Murder of Engine Maker Roolfsen") by Maurits Hansen

Maurits Christopher Hansen (5 July 1794 ŌĆō 16 March 1842) was a Norwegian writer.

He was born in Modum as a son of Carl Hansen (1757ŌĆō1826) and Abigael Wulfsberg (1758ŌĆō1823). In October 1816 he married teacher Helvig Leschly (1789ŌĆō1874). ...

was published in December 1839.

"Das Fr├żulein von Scuderi

''Das Fr├żulein von Scuderi'' is an East German crime film directed by Eugen York. It was released in 1955.

Cast

* Henny Porten as Fr├żulein von Scuderi

* Willy A. Kleinau as Cardillac

* Anne Vernon as Madelon

* Roland Alexandre as O ...

" is an 1819 short story by E. T. A. Hoffmann, in which Mlle de Scudery establishes the innocence of the police's favorite suspect in the murder of a jeweller. This story is sometimes cited as the first detective story and as a direct influence on Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 ŌĆō October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue

"The Murders in the Rue Morgue" is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe published in ''Graham's Magazine'' in 1841. It has been described as the first modern detective story; Poe referred to it as one of his "tales of ratiocination".

C. Auguste Dup ...

" (1841). Also suggested as a possible influence on Poe is ŌĆśThe Secret CellŌĆÖ, a short story published in September 1837 by William Evans Burton

William Evans Burton (24 September 180410 February 1860) was an English actor, playwright, Actor-manager, theatre manager and publisher who relocated to the United States.

Life and work

Early life

Born in London on 24 September 1804, Burton w ...

. It has been suggested that this story may have been known to Poe, who in 1839 worked for Burton. The story was about a London policeman who solves the mystery of a kidnapped girl. Burton's fictional detective relied on practical methods such as dogged legwork, knowledge of the underworld and undercover surveillance, rather than brilliance of imagination or intellect.

English genre establishment

Detective fiction in the English-speaking world is considered to have begun in 1841 with the publication of Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", featuring "the first fictional detective, the eccentric and brilliantC. Auguste Dupin

''Le Knight, Chevalier'' C. Auguste Dupin is a fictional character created by Edgar Allan Poe. Dupin made his first appearance in Poe's 1841 short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", widely considered the first detective fiction story. He rea ...

". When the character first appeared, the word ''detective'' had not yet been used in English; however, the character's name, "Dupin", originated from the English word dupe or deception. Poe devised a "plot formula that's been successful ever since, give or take a few shifting variables."Kismaric, Carole and Heiferman, Marvin. ''The Mysterious Case of Nancy Drew & The Hardy Boys''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998. p. 56. Poe followed with further Auguste Dupin tales: "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt

"The Mystery of Marie Rogêt", often subtitled ''A Sequel to "The Murders in the Rue Morgue"'', is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe written in 1842. This is the first murder mystery based on the details of a real crime. It first ...

" in 1842 and "The Purloined Letter

"The Purloined Letter" is a short story by American author Edgar Allan Poe. It is the third of his three detective stories featuring the fictional C. Auguste Dupin, the other two being "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" and " The Mystery of Marie Rog ...

" in 1844.

Poe referred to his stories as "tales of ratiocination

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, langu ...

". In stories such as these, the primary concern of the plot is ascertaining truth, and the usual means of obtaining the truth is a complex and mysterious process combining intuitive logic, astute observation, and perspicacious inference. "Early detective stories tended to follow an investigating protagonist from the first scene to the last, making the unravelling a practical rather than emotional matter." "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" is particularly interesting because it is a barely fictionalized account based on Poe's theory of what happened to the real-life Mary Cecilia Rogers.

William Russell (1806ŌĆō1876) was among the first English authors to write fictitious 'police memoirs', contributing an irregular series of stories (under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

'Waters') to ''Chambers's Edinburgh Journal

''Chambers's Edinburgh Journal'' was a weekly 16-page magazine started by William Chambers in 1832. The first edition was dated 4 February 1832, and priced at one penny. Topics included history, religion, language, and science. William was soo ...

'' between 1849 and 1852. Unauthorised collections of his stories were published in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in 1852 and 1853, entitled ''The Recollections of a Policeman''. Twelve stories were then collated into a volume entitled ''Recollections of a Detective Police-Officer'', published in London in 1856.

Literary critic Catherine Ross Nickerson credits Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott (; November 29, 1832March 6, 1888) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known as the author of the novel ''Little Women'' (1868) and its sequels ''Little Men'' (1871) and ''Jo's Boys'' (1886). Raised in ...

with creating the second-oldest work of modern detective fiction, after only Poe's Dupin stories themselves, with the 1865 thriller "V.V., or Plots and Counterplots." A short story published anonymously by Alcott, the story concerns a Scottish aristocrat who tries to prove that a mysterious woman has killed his fianc├®e and cousin. The detective on the case, Antoine Dupres, is a parody of Auguste Dupin who is less concerned with solving the crime as he is in setting up a way to reveal the solution with a dramatic flourish. Ross Nickerson notes that many of the American writers who experimented with Poe's established rules of the genre were women, inventing a subgenre of domestic detective fiction that flourished in its own right for several generations. These included Metta Fuller Victor

Metta Victoria Fuller Victor (n├®e Fuller; March 2, 1831 ŌĆō June 26, 1885), who used the pen name Seeley Regester among others, was an American novelist, credited with authoring of one of the first detective novels in the United States. She wro ...

's two detective novels ''The Dead Letter'' (1867) and ''The Figure Eight'' (1869). ''The Dead Letter'' is noteworthy as the first full-length work of American crime fiction.

├ēmile Gaboriau

├ēmile Gaboriau (9 November 183228 September 1873) was a French writer, novelist, journalist, and a pioneer of detective fiction.

Early life

Gaboriau was born in the small town of Saujon, Charente-Maritime. He was the son of Charles Gabriel Ga ...

was a pioneer of the detective fiction genre in France. In ''Monsieur Lecoq

Monsieur Lecoq is the creation of ├ēmile Gaboriau, a 19th-century French writer and journalist. Monsieur Lecoq is a fictional detective employed by the French S├╗ret├®. The character is one of the pioneers of the genre and a major influence on She ...

'' (1868), the title character is adept at disguise, a key characteristic of detectives. Gaboriau's writing is also considered to contain the first example of a detective minutely examining a crime scene for clues.

Another early example of a whodunit is a subplot in the novel ''

Another early example of a whodunit is a subplot in the novel ''Bleak House

''Bleak House'' is a novel by Charles Dickens, first published as a 20-episode serial between March 1852 and September 1853. The novel has many characters and several sub-plots, and is told partly by the novel's heroine, Esther Summerson, and ...

'' (1853) by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 ŌĆō 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

. The conniving lawyer Tulkinghorn is killed in his office late one night, and the crime is investigated by Inspector Bucket of the Metropolitan police force. Numerous characters appeared on the staircase leading to Tulkinghorn's office that night, some of them in disguise, and Inspector Bucket must penetrate these mysteries to identify the murderer. Dickens also left a novel unfinished at his death, ''The Mystery of Edwin Drood

''The Mystery of Edwin Drood'' is the final novel by Charles Dickens, originally published in 1870.

Though the novel is named after the character Edwin Drood, it focuses more on Drood's uncle, John Jasper, a precentor, choirmaster and opium ...

''.

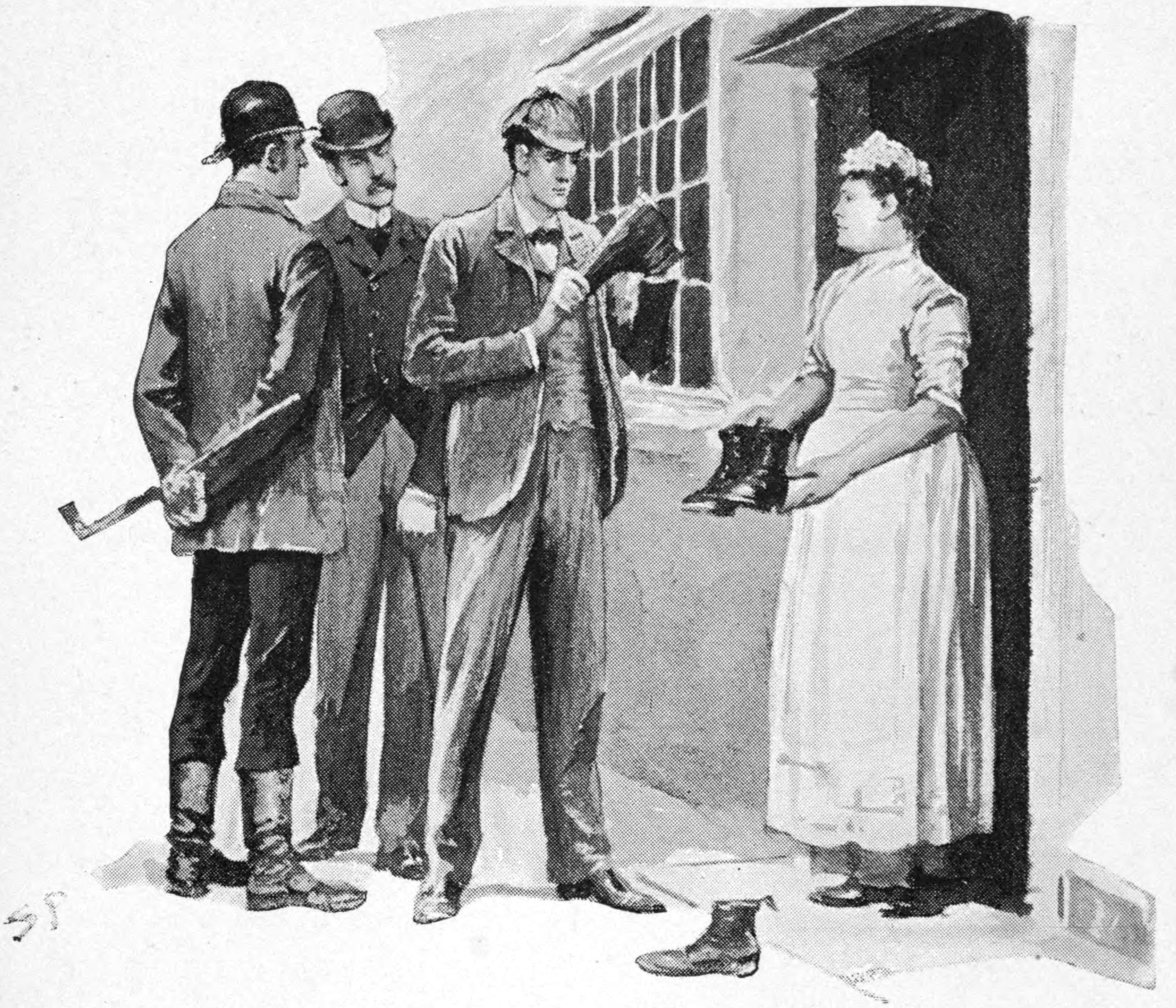

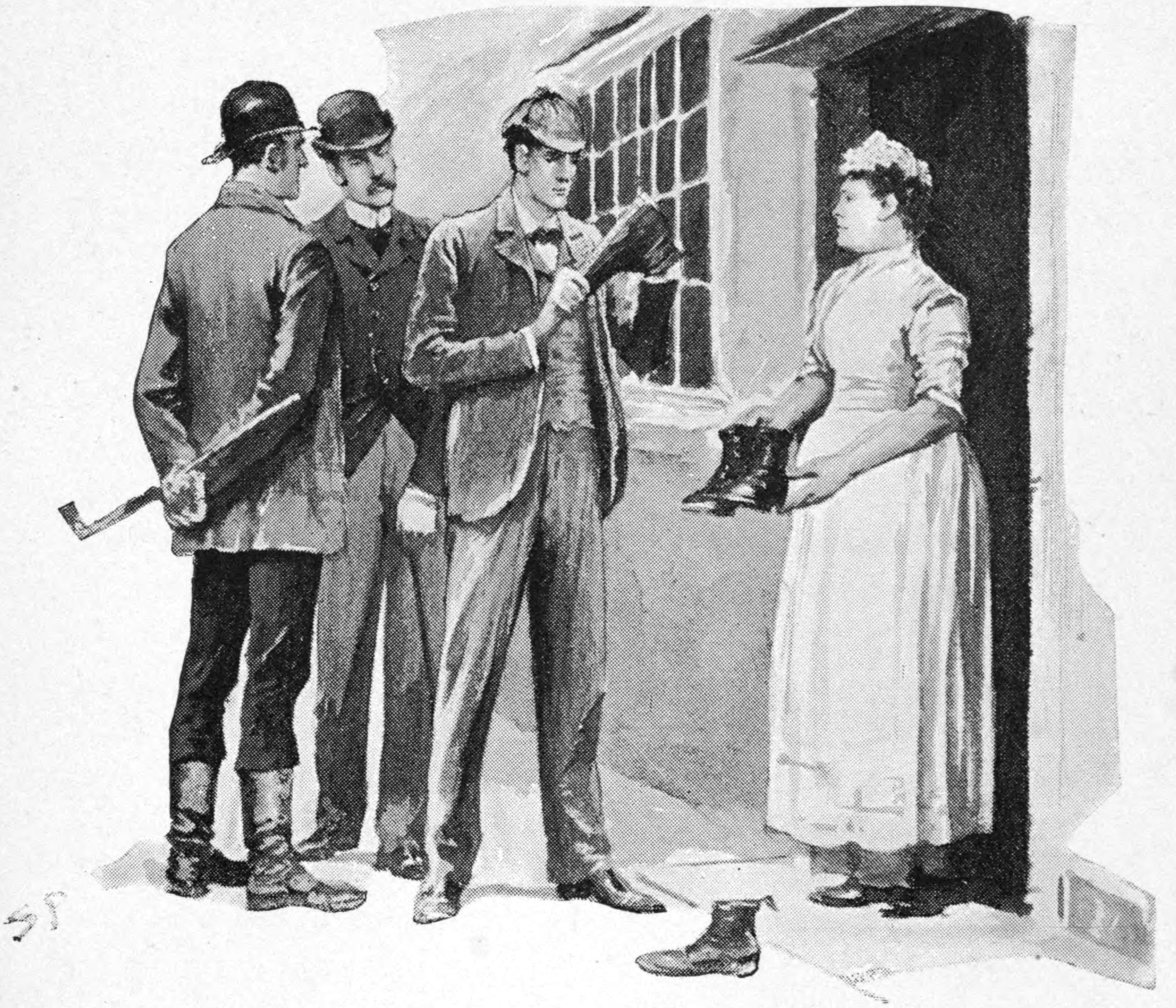

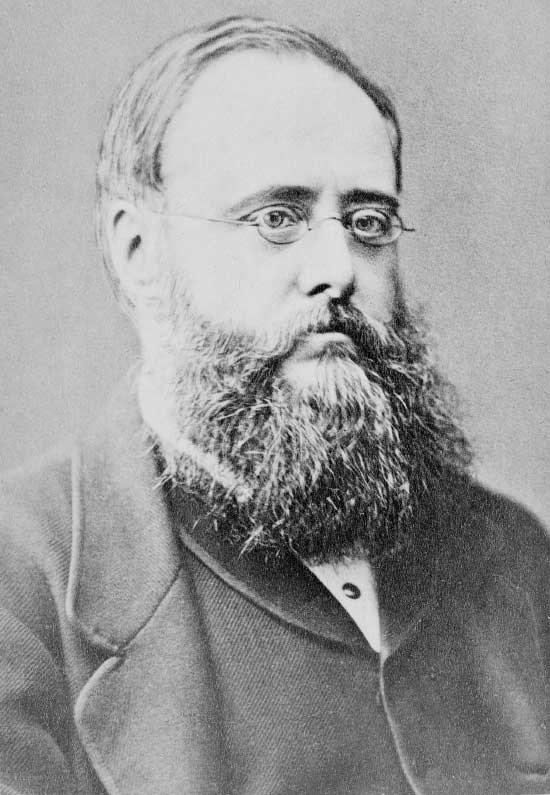

Dickens's prot├®g├®,

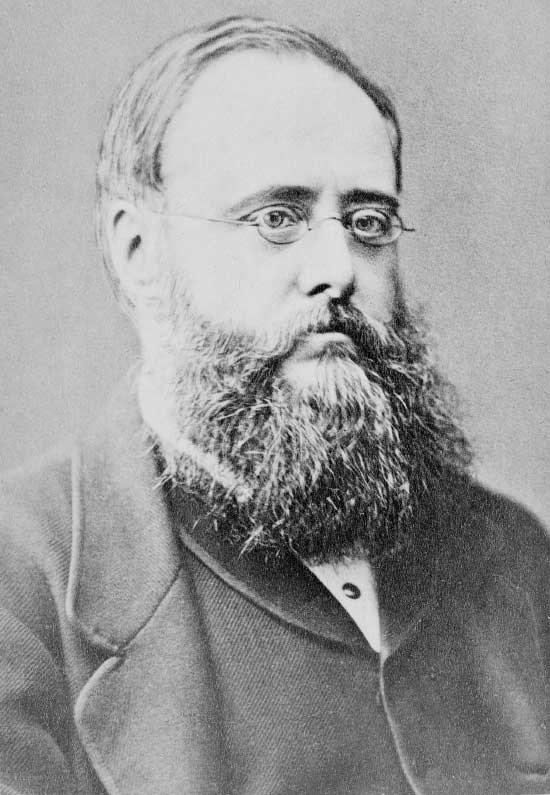

Dickens's prot├®g├®, Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 ŌĆō 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1859), a mystery novel and early "sensation novel", and for ''The Moons ...

(1824ŌĆō1889)ŌĆösometimes called the "grandfather of English detective fiction"ŌĆöis credited with the first great mystery novel, '' The Woman in White''. T. S. Eliot called Collins's novel ''The Moonstone

''The Moonstone'' (1868) by Wilkie Collins is a 19th-century British epistolary novel. It is an early example of the modern detective novel, and established many of the ground rules of the modern genre. The story was serialised in Charles Dic ...

'' (1868) "the first, the longest, and the best of modern English detective novels... in a genre invented by Collins and not by Poe", and Dorothy L. Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (; 13 June 1893 ŌĆō 17 December 1957) was an English crime writer and poet. She was also a student of classical and modern languages.

She is best known for her mysteries, a series of novels and short stories set between th ...

called it "probably the very finest detective story ever written". ''The Moonstone'' contains a number of ideas that have established in the genre several classic features of the 20th century detective story:

* English country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the cityŌĆöhence, for these peopl ...

robbery

* An "inside job

An insider threat is a malicious threat to an organization that comes from people within the organization, such as employees, former employees, contractors or business associates, who have inside information concerning the organization's security ...

"

* red herrings

A red herring is a figurative expression referring to a logical fallacy in which a clue or piece of information is or is intended to be misleading, or distracting from the actual question.

Red herring may also refer to: Animals

* Red herring (fish ...

* A celebrated, skilled, professional investigator

* Bungling local constabulary

* Detective inquiries

* Large number of false suspects

* The "least likely suspect"

* A rudimentary " locked room" murder

* A reconstruction of the crime

* A final twist in the plot

Although ''The Moonstone'' is usually seen as the first detective novel, there are other contenders for the honor. A number of critics suggest that the lesser known '' Notting Hill Mystery'' (1862ŌĆō63), written by the pseudonymous "Charles Felix" (later identified as

Although ''The Moonstone'' is usually seen as the first detective novel, there are other contenders for the honor. A number of critics suggest that the lesser known '' Notting Hill Mystery'' (1862ŌĆō63), written by the pseudonymous "Charles Felix" (later identified as Charles Warren Adams

Charles Warren Adams (1833ŌĆō1903) was an English lawyer, publisher and anti-vivisectionist, now known from documentary evidence to have been the author of ''The Notting Hill Mystery''. This is often taken to be the first full-length detective no ...

), preceded it by a number of years and first used techniques that would come to define the genre. Paul Collins"The Case of the First Mystery Novelist"

in-print as "Before Hercule or Sherlock, There Was Ralph", ''

New York Times Book Review

''The New York Times Book Review'' (''NYTBR'') is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times'' in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely rea ...

'', January 7, 2011, p. 46

Literary critics Chris Willis and Kate Watson consider Mary Elizabeth Braddon

Mary Elizabeth Braddon (4 October 1835 ŌĆō 4 February 1915) was an English popular novelist of the Victorian era. She is best known for her 1862 sensation novel ''Lady Audley's Secret'', which has also been dramatised and filmed several times.

...

's first book, the even earlier ''The Trail of the Serpent

''The Trail of the Serpent'' is the debut novel by Mary Elizabeth Braddon, first published in 1860 as ''Three Times Dead; or, The Secret of the Heath''. The story concerns the schemes of the orphan Jabez North to acquire an aristocratic fortune, ...

'' (1861), the first British detective novel. The novel "features an unusual and innovative detective figure, Mr. Peters, who is lower class and mute, and who is initially dismissed both by the text and its characters." Braddon's later and better-remembered work, ''Aurora Floyd

''Aurora Floyd'' (1863) is a sensation novel written by the prominent English author Mary Elizabeth Braddon. It forms a sequel to Braddon's highly popular novel ''Lady Audley's Secret'' (1862).

Plot

Aurora Floyd is the spoiled, impetuous, but ...

'' (printed in 1863 novel form, but serialized in 1862ŌĆō63), also features a compelling detective in the person of Detective Grimstone of Scotland Yard.

Tom Taylor

Tom Taylor (19 October 1817 – 12 July 1880) was an English dramatist, critic, biographer, public servant, and editor of ''Punch'' magazine. Taylor had a brief academic career, holding the professorship of English literature and language a ...

's melodrama '' The Ticket-of-Leave Man'', an adaptation of ''L├®onard'' by ├ēdouard Brisbarre and Eug├©ne Nus, appeared in 1863, introducing Hawkshaw the Detective. In short, it is difficult to establish who was the first to write the English-language detective novel, as various authors were exploring the theme simultaneously.

Anna Katharine Green

Anna Katharine Green (November 11, 1846 – April 11, 1935) was an American poet and novelist. She was one of the first writers of detective fiction in America and distinguished herself by writing well plotted, legally accurate stories. Green ...

, in her 1878 debut '' The Leavenworth Case'' and other works, popularized the genre among middle-class readers and helped to shape the genre into its classic form as well as developed the concept of the series detective.

In 1887, Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 ŌĆō 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

created Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

, arguably the most famous of all fictional detectives. Although Sherlock Holmes is not the original fictional detective (he was influenced by Poe's Dupin Dupin is a French surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andr├® Marie Jean Jacques Dupin (1783ŌĆō1865), French advocate

* C. Auguste Dupin, a fictional detective

* Charles Dupin (1784ŌĆō1873), French Catholic mathematician

* Jacques D ...

and Gaboriau's Lecoq), his name has become a byword for the part. Conan Doyle stated that the character of Holmes was inspired by Dr. Joseph Bell, for whom Doyle had worked as a clerk at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

. Like Holmes, Bell was noted for drawing large conclusions from the smallest observations. A brilliant London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

-based "consulting detective" residing at 221B Baker Street

221B Baker Street is the London address of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, created by author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In the United Kingdom, postal addresses with a number followed by a letter may indicate a separate address within ...

, Holmes is famous for his intellectual prowess and is renowned for his skillful use of astute observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. The ...

, deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning is the mental process of drawing deductive inferences. An inference is deductively valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, i.e. if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be fals ...

, and forensic

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to Criminal law, criminal and Civil law (legal system), civil laws, mainlyŌĆöon the criminal sideŌĆöduring criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standard ...

skills to solve difficult cases. Conan Doyle wrote four novels

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itself ...

and fifty-six short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest t ...

featuring Holmes, and all but four stories are narrated by Holmes's friend, assistant, and biographer, Dr. John H. Watson.

Golden Age novels

The period between World War I and World War II (the 1920s and 1930s) is generally referred to as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. During this period, a number of very popular writers emerged, including mostly British but also a notable subset of American and New Zealand writers. Female writers constituted a major portion of notable Golden Age writers.

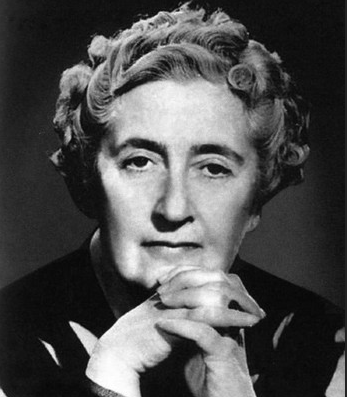

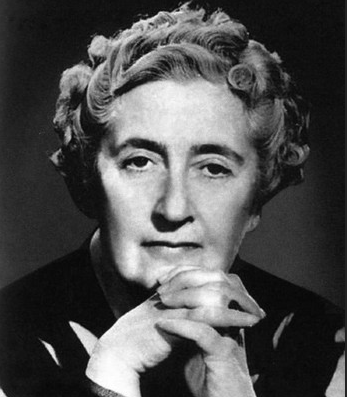

The period between World War I and World War II (the 1920s and 1930s) is generally referred to as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. During this period, a number of very popular writers emerged, including mostly British but also a notable subset of American and New Zealand writers. Female writers constituted a major portion of notable Golden Age writers. Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 ŌĆō 12 January 1976) was an English writer known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving around fictiona ...

, Dorothy L. Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (; 13 June 1893 ŌĆō 17 December 1957) was an English crime writer and poet. She was also a student of classical and modern languages.

She is best known for her mysteries, a series of novels and short stories set between th ...

, Josephine Tey

Josephine Tey was a pseudonym used by Elizabeth MacKintosh (25 July 1896 ŌĆō 13 February 1952), a Scottish author. Her novel ''The Daughter of Time'' was a detective work investigating the role of Richard III of England in the death of the Princ ...

, Margery Allingham

Margery Louise Allingham (20 May 1904 ŌĆō 30 June 1966) was an English novelist from the "Golden Age of Detective Fiction", and considered one of its four " Queens of Crime", alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers and Ngaio Marsh.

Alli ...

, and Ngaio Marsh

Dame Edith Ngaio Marsh (; 23 April 1895 ŌĆō 18 February 1982) was a New Zealand mystery writer and theatre director. She was appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1966.

As a crime writer during the "Golden Age of Det ...

were particularly famous female writers of this time. Apart from Ngaio Marsh (a New Zealander), they were all British.

Various conventions of the detective genre were standardized during the Golden Age, and in 1929, some of them were codified by the English Catholic priest and author of detective stories Ronald Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 February 1888 ŌĆō 24 August 1957) was an Catholic Church in England and Wales, English Catholic priest, Catholic theology, theologian, author, and radio broadcaster. Educated at Eton College, Eton and Balliol Colleg ...

in his 'Decalogue' of rules for detective fiction. One of his rules was to avoid supernatural elements so that the focus remained on the mystery itself. Knox has contended that a detective story "must have as its main interest the unravelling of a mystery; a mystery whose elements are clearly presented to the reader at an early stage in the proceedings, and whose nature is such as to arouse curiosity, a curiosity which is gratified at the end." Another common convention in Golden Age detective stories involved an outsiderŌĆōsometimes a salaried investigator or a police officer, but often a gifted amateurŌĆöinvestigating a murder committed in a closed environment by one of a limited number of suspects.

The most widespread subgenre of the detective novel became the whodunit (or whodunnit, short for "who done it?"). In this subgenre, great ingenuity may be exercised in narrating the crime, usually a homicide, and the subsequent investigation. This objective was to conceal the identity of the criminal from the reader until the end of the book, when the method and culprit are both revealed. According to scholars Carole Kismaric and Marvin Heiferman

Marvin Heiferman (born 1948) is an American curator and writer, who originates projects about the impact of photographic images on art, visual culture, and science for museums, art galleries, publishers and corporations.

Biography

As Assistan ...

, "The golden age of detective fiction began with high-class amateur detectives sniffing out murderers lurking in rose gardens, down country lanes, and in picturesque villages. Many conventions of the detective-fiction genre evolved in this era, as numerous writersŌĆöfrom populist entertainers to respected poetsŌĆötried their hands at mystery stories."

John Dickson CarrŌĆöwho also wrote as Carter DicksonŌĆöused the ŌĆ£puzzleŌĆØ approach in his writing which was characterized by including a complex puzzle for the reader to try to unravel. He created ingenious and seemingly impossible plots and is regarded as the master of the "locked room mystery

The "locked-room" or "impossible crime" mystery is a type of crime seen in crime and detective fiction. The crime in question, typically murder ("locked-room murder"), is committed in circumstances under which it appeared impossible for the perpetr ...

". Two of Carr's most famous works are ''The Case of Constant Suicides'' (1941) and ''The Hollow Man'' (1935). Another author, Cecil Street

Cecil John Charles Street (3 May 1884 ŌĆō 8 December 1964), who was known to his colleagues, family and friends as John Street, began his military career as an artillery officer in the British Army. During the course of World War I, he became a ...

ŌĆöwho also wrote as John RhodeŌĆöwrote of a detective, Dr. Priestley, who specialised in elaborate technical devices. In the United States, the whodunit subgenre was adopted and extended by Rex Stout

Rex Todhunter Stout (; December 1, 1886 – October 27, 1975) was an American writer noted for his detective fiction. His best-known characters are the detective Nero Wolfe and his assistant Archie Goodwin, who were featured in 33 novels and ...

and Ellery Queen

Ellery Queen is a pseudonym created in 1929 by American crime fiction writers Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee and the name of their main fictional character, a mystery writer in New York City who helps his police inspector father solve ...

, along with others. The emphasis on formal rules during the Golden Age produced great works, albeit with highly standardized form. The most successful novels of this time included ŌĆ£an original and exciting plot; distinction in the writing, a vivid sense of place, a memorable and compelling hero and the ability to draw the reader into their comforting and highly individual world.ŌĆØ

'Whodunit'

A ''whodunit'' or ''whodunnit'' (a colloquial elision of "Who asdone it?" or "Who did it?") is a complex, plot-driven variety of the detective story in which the audience is given the opportunity to engage in the same process of deduction as the protagonist throughout the investigation of a crime. The reader or viewer is provided with the clues from which the identity of the perpetrator may be deduced before the story provides the revelation itself at itsclimax

Climax may refer to:

Language arts

* Climax (narrative), the point of highest tension in a narrative work

* Climax (rhetoric), a figure of speech that lists items in order of importance

Biology

* Climax community, a biological community th ...

. The "whodunit" flourished during the so-called "Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

" of detective fiction, between 1920 and 1950, when it was the predominant mode of crime writing.

Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie is not only the most famous Golden Age writer, but also considered one of the most famous authors of all genres of all time. At the time of her death in 1976, ŌĆ£she was the best-selling novelist in history.ŌĆØ Many of the most popular books of the Golden Age were written by Agatha Christie. She produced long series of books featuring detective characters like Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, amongst others. Her use of basing her stories on complex puzzles, ŌĆ£combined with her stereotyped characters and picturesque middle-class settingsŌĆØ, is credited for her success. Christie's works include ''Murder on the Orient Express'' (1934), ''Death on the Nile'' (1937), ''Three Blind Mice

"Three Blind Mice" is an English-language nursery rhyme and musical round.I. Opie and P. Opie, ''The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951, 2nd edn., 1997), p. 306. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number o ...

'' (1950) and ''And Then There Were None'' (1939).

By country

China

Through China's Golden Age ofcrime fiction

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

(1900ŌĆō1949), translations of Western classics, and native Chinese detective fictions circulated within the country.

Cheng Xiaoqing

Cheng Xiaoqing (2 June 1893 – 12 October 1976) was a Chinese detective fiction writer and foreign detective fiction translator. He is known for his Huo Sang series, in which the main character, Huo Sang, is considered to be "the Eastern ...

had first encountered Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 ŌĆō 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

's highly popular stories as an adolescent. In the ensuing years, he played a major role in rendering them first into classical and later into vernacular Chinese

Written vernacular Chinese, also known as Baihua () or Huawen (), is the forms of written Chinese based on the varieties of Chinese spoken throughout China, in contrast to Classical Chinese, the written standard used during imperial China up to ...

. Cheng Xiaoqing's translated works from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 ŌĆō 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for '' A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

introduced China to a new type of narrative style. Western detective fiction that was translated often emphasized ŌĆ£individuality, equality, and the importance of knowledgeŌĆØ, appealing to China that it was the time for opening their eyes to the rest of the world.

This style began China's interest in popular crime fiction

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

, and is what drove Cheng Xiaoqing to write his own crime fiction

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

novel, ''Sherlock in Shanghai''. In the late 1910s, Cheng began writing detective fiction very much in Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 ŌĆō 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

's style, with Bao as the Watson-like narrator; a rare instance of such a direct appropriation from foreign fiction. Famed as the ŌĆ£Oriental Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

ŌĆØ, the duo Huo Sang and Bao Lang become counterparts to Doyle

Doyle is a surname of Irish origin. The name is a back-formation from O'Doyle, which is an Anglicisation of the Irish (), meaning "descendant of ''Dubhghall''". There is another possible etymology: the Anglo-Norman surname ''D'Oyley'' with agglu ...

's Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

and Dr. Watson

John H. Watson, known as Dr. Watson, is a fictional character in the Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Along with Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson first appeared in the novel ''A Study in Scarlet'' (1887). The last work by Doyle f ...

characters.

Japan

Edogawa Rampo

, better known by the pen name was a Japanese author and critic who played a major role in the development of Japanese mystery and thriller fiction. Many of his novels involve the detective hero Kogoro Akechi, who in later books was the le ...

is the first major Japanese modern mystery writer and the founder of the Detective Story Club in Japan. Rampo was an admirer of western mystery writers. He gained his fame in the early 1920s, when he began to bring to the genre many bizarre, erotic and even fantastic elements. This is partly because of the social tension before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

. In 1957, Seicho Matsumoto received the Mystery Writers of Japan Award The are presented every year by the Mystery Writers of Japan. They honor the best in crime fiction and critical/biographical work published in the previous year.

MWJ Award for Best Novel winners (1948ŌĆō1951, 1976ŌĆōpresent)

MWJ Award for Best ...

for his short story ''The Face'' (''ķĪö'' ''kao''). ''The Face'' and Matsumoto's subsequent works began the "social school" (ńżŠõ╝ܵ┤Š ''shakai ha'') within the genre, which emphasized social realism

Social realism is the term used for work produced by painters, printmakers, photographers, writers and filmmakers that aims to draw attention to the real socio-political conditions of the working class as a means to critique the power structure ...

, described crimes in an ordinary setting and sets motives within a wider context of social injustice and political corruption. Since the 1980s, a " new orthodox school" (µ¢░µ£¼µĀ╝µ┤Š ''shin honkaku ha'') has surfaced. It demands restoration of the classic rules of detective fiction and the use of more self-reflective elements. Famous authors of this movement include Soji Shimada

is a Japanese mystery writer. Born in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan.

Biography

Soji Shimada graduated from Seishikan High School in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima Prefecture, and later Musashino Art University as a Commercial arts d ...

, Yukito Ayatsuji

, who writes under his pen name , is a Japanese writer of mystery and horror. He is one of the founders of Honkaku Mystery Writers Club of Japan and one of the representative writers of the new traditionalist movement in Japanese mystery writing ...

, Rintaro Norizuki

is a Japanese mystery/crime writer. He is the President of Honkaku Mystery Writers Club of Japan and one of the representative writers of the new traditionalist movement in Japanese mystery writing. His works are deeply influenced by Ellery Que ...

, Alice Arisugawa

, mainly known by his pseudonym , is a Japanese mystery writer. He is one of the representative writers of the new traditionalist movement in Japanese mystery writing and was the first president of the Honkaku Mystery Writers Club of Japan from 20 ...

, Kaoru Kitamura and Taku Ashibe

is a Japanese mystery writer. He is a member of the Honkaku Mystery Writers Club of Japan and one of the representative writers of the new traditionalist movement in Japanese mystery writing.

Works in English translation

;Novel

* '' Murder in ...

.

Pakistan

Ibn-e-Safi

Ibn-e-Safi (26 July 1928 – 26 July 1980) (also spelled as Ibne Safi) ( ur, ) was the pen name of Asrar Ahmad ( ur, ), a fiction writer, novelist and poet of Urdu from Pakistan. The word Ibn-e-Safi is an Persian expression which litera ...

is the most popular Urdo detective fiction writer. He started writing his famous Jasoosi Dunya Series spy stories in 1952 with Col. Fareedi & Captain. Hameed as main characters.

In 1955 he started writing Imran Series spy novels with Ali Imran as X2 the chief of secret service and his companions.

After his death many other writers accepted Ali Imran character and wrote spy novels.

Another popular spy novel writer was Ishtiaq Ahmad who wrote Inspector Jamsheed, Inspector Kamran Mirza and Shooki brother's series of spy novels.

Russia

Stories about robbers and detectives were very popular in Russia since old times. The most famous hero in XVIII cent. was Ivan Osipov (1718ŌĆōafter 1756), nicknamed Ivan Kain. Another examples of early Russian detective stories are: "Bitter Fate" (1789) by M. D. Chulkov (1743ŌĆō1792), "The Finger Ring" (1831) byYevgeny Baratynsky

Yevgeny Abramovich Baratynsky (russian: ąĢą▓ą│ąĄ╠üąĮąĖą╣ ąÉą▒čĆą░╠üą╝ąŠą▓ąĖčć ąæą░čĆą░čéčŗ╠üąĮčüą║ąĖą╣, p=j╔¬v╦ł╔Ī╩▓en╩▓╔¬j ╔É╦łbram╔Öv╩▓╔¬t╔Ģ b╔Ör╔É╦łt╔©nsk╩▓╔¬j, a=Yevgyeniy Abramovich Baratynskiy.ru.vorb.oga; 11 July 1844) was lauded by Alexan ...

, "The White Ghost" (1834) by Mikhail Zagoskin

Mikhail Nikolayevich Zagoskin (russian: ą£ąĖčģą░ąĖą╗ ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ąĄą▓ąĖčć ąŚą░ą│ąŠčüą║ąĖąĮ; July 25, 1789 ŌĆō July 5, 1852) was a Russian writer of social comedies and historical novels.

Zagoskin was born in the village of Ramzay in Penza Oblast. ...

, ''Crime and Punishment

''Crime and Punishment'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, ą¤čĆąĄčüčéčāą┐ą╗ąĄąĮąĖąĄ ąĖ ąĮą░ą║ą░ąĘą░ąĮąĖąĄ, Prestupl├®niye i nakaz├Īniye, pr╩▓╔¬st╩Ŗ╦łpl╩▓en╩▓╔¬je ╔¬ n╔Ök╔É╦łzan╩▓╔¬je) is a novel by the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. ...

'' (1866) and ''The Brothers Karamazov

''The Brothers Karamazov'' (russian: ąæčĆą░čéčīčÅ ąÜą░čĆą░ą╝ą░ąĘąŠą▓čŗ, ''Brat'ya Karamazovy'', ), also translated as ''The Karamazov Brothers'', is the last novel by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky spent nearly two years writing '' ...

'' (1880) by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, ążčæą┤ąŠčĆ ą£ąĖčģą░ą╣ą╗ąŠą▓ąĖčć ąöąŠčüč鹊ąĄą▓čüą║ąĖą╣, Fy├│dor Mikh├Īylovich Dostoy├®vskiy, p=╦łf╩▓╔Ąd╔Ör m╩▓╔¬╦łxajl╔Öv╩▓╔¬d╩æ d╔Öst╔É╦łjefsk╩▓╔¬j, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

. Detective fiction in modern Russian literature with clear detective plots started with ''The Garin Death Ray

''The Garin Death Ray'', also known as ''The Death Box'' and ''The Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin'' (russian: ąōąĖą┐ąĄčĆą▒ąŠą╗ąŠąĖą┤ ąĖąĮąČąĄąĮąĄčĆą░ ąōą░čĆąĖąĮą░), is a science fiction novel by the noted Russian author Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolst ...

'' (1926ŌĆō1927) and ''The Black Gold'' (1931) by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy

Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy (russian: link= no, ąÉą╗ąĄą║čüąĄą╣ ąØąĖą║ąŠą╗ą░ąĄą▓ąĖčć ąóąŠą╗čüč鹊ą╣; ŌĆō 23 February 1945) was a Russian writer who wrote in many genres but specialized in science fiction and historical novels.

Despite having ...

, ''Mess-Mend'' by Marietta Shaginyan

Marietta Sergeevna Shaginyan (russian: ą£ą░čĆąĖčŹ╠üčéčéą░ ąĪąĄčĆą│ąĄ╠üąĄą▓ąĮą░ ą©ą░ą│ąĖąĮčÅ╠üąĮ; hy, šäšĪųĆš½šźš┐šĪ šŹšźųĆšŻšźšĄš½ šćšĪš░š½šČšĄšĪšČ, April 2, 1888 – March 20, 1982) was a Soviet writer, historian and activist of Armenian des ...

, ''The Investigator's Notes'' by Lev Sheinin Lev Romanovich Sheinin (1906-1967) was a Soviet writer, journalist, and NKVD investigator. He was Andrei Vyshinsky's chief investigator during the show trials of the 1930s, and a member of the Soviet team at the Nuremberg trials. In the 1930s he co ...

. Boris Akunin

Boris Akunin (russian: ąæąŠčĆąĖčü ąÉą║čāąĮąĖąĮ) is the pen name of Grigori Chkhartishvili (russian: ąōčĆąĖą│ąŠčĆąĖą╣ ą©ą░ą╗ą▓ąŠą▓ąĖčć ą¦čģą░čĆčéąĖčłą▓ąĖą╗ąĖ, Grigory Shalvovich Chkhartishvili; ka, ßāÆßāĀßāśßāÆßāØßāĀßāś ßā®ßā«ßāÉßāĀßāóßāśßā©ßāĢß ...

is a famous Russian writer of historical detective fiction in modern-day Russia.

United States

Especially in the United States, detective fiction emerged in the 1960s, and gained prominence in later decades, as a way for authors to bring stories about various subcultures to mainstream audiences. One scholar wrote about the detective novels ofTony Hillerman

Anthony Grove Hillerman (May 27, 1925 ŌĆō October 26, 2008) was an American author of detective novels and nonfiction works, best known for his mystery novels featuring Navajo Nation Police officers Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee. Several of his work ...

, set among the Native American population around New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, "many American readers have probably gotten more insight into traditional Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Din├® or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

culture from his detective stories than from any other recent books." Other notable writers who have explored regional and ethnic communities in their detective novels are Harry Kemelman

Harry Kemelman (November 24, 1908 ŌĆō December 15, 1996) was an American mystery writer and a professor of English. He was the creator of the fictitious religious sleuth Rabbi David Small.

Early life

Harry Kemelman was born in Boston, Massac ...

, whose Rabbi Small

''Friday the Rabbi Slept Late'' is a 1964 mystery novel by Harry Kemelman, the first of the successful ''Rabbi Small'' series.

Plot introduction

The fictional hero of the book, David Small, is the unconventional leader of the Conservative Jud ...

series were set in the Conservative Jewish

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a Jewish religious movement which regards the authority of ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions as coming primarily from its people and community through the generat ...

community of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, m╔Öhswat╩ā╔Öwi╦És╔Öt'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

; Walter Mosley

Walter Ellis Mosley (born January 12, 1952) is an American novelist, most widely recognized for his crime fiction. He has written a series of best-selling historical mysteries featuring the hard-boiled detective Easy Rawlins, a black private inv ...

, whose Easy Rawlins

Easy may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Easy'' (film), a 2003 American romantic comedy film

*''Easy!'', or ''Scialla!'', a 2011 Italian comedy film

* ''Easy'' (TV series), a 2016ŌĆō2019 American comedy-drama anthology ...

books are set in the African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

community of 1950s Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

; and Sara Paretsky

Sara Paretsky (born June 8, 1947) is an American author of detective fiction, best known for her novels focused on the protagonist V. I. Warshawski.

Life and career

Paretsky was born in Ames, Iowa. Her father was a microbiologist and moved the ...

, whose V. I. Warshawski

Victoria Iphigenia "Vic" "V. I." Warshawski is a fictional private investigator from Chicago who is the protagonist featured in a series of detective novels and short stories written by Chicago author Sara Paretsky.

With the exception of "The ...

books have explored the various subcultures of Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

.

Subgenres

Hardboiled

Martin Hewitt, created by British authorArthur Morrison

Arthur George Morrison (1 November 1863 ŌĆō 4 December 1945) was an English writer and journalist known for realistic novels, for stories about working-class life in the East End of London, and for detective stories featuring a specific detect ...

in 1894, is one of the first examples of the modern style of fictional private detective

A private investigator (often abbreviated to PI and informally called a private eye), a private detective, or inquiry agent is a person who can be hired by individuals or groups to undertake investigatory law services. Private investigators of ...

. This character is described as an "'Everyman' detective meant to challenge the detective-as-superman that Holmes represented."Rzepka, Charles J. (2005)''Detective Fiction''

Polity. . By the late 1920s,

Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone (; January 17, 1899 ŌĆō January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-founder and boss of the ...

and the Mob were inspiring not only fear, but piquing mainstream curiosity about the American crime underworld. Popular pulp fiction magazine

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 to the late 1950s. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazine ...

s like '' Black Mask'' capitalized on this, as authors such as Carrol John Daly published violent stories that focused on the mayhem and injustice surrounding the criminals, not the circumstances behind the crime. Very often, no actual mystery even existed: the books simply revolved around justice being served to those who deserved harsh treatment, which was described in explicit detail." The overall theme these writers portrayed reflected "the changing face of America itself."

In the 1930s, the private eye genre was adopted wholeheartedly by American writers. One of the primary contributors to this style was Dashiell Hammett

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (; May 27, 1894 ŌĆō January 10, 1961) was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the enduring characters he created are Sam Spade ('' ...

with his famous private investigator character, Sam Spade.Messent, P. (2006). ''Introduction: From private eye to police procedural ŌĆō the logic of contemporary crime fiction'' His style of crime fiction came to be known as "hardboiled

Hardboiled (or hard-boiled) fiction is a literary genre that shares some of its characters and settings with crime fiction (especially detective fiction and noir fiction). The genre's typical protagonist is a detective who battles the violence o ...

", which is described as a genre that "usually deals with criminal activity in a modern urban environment, a world of disconnected signs and anonymous strangers." "Told in stark and sometimes elegant language through the unemotional eyes of new hero-detectives, these stories were an American phenomenon."

In the late 1930s, Raymond Chandler

Raymond Thornton Chandler (July 23, 1888 ŌĆō March 26, 1959) was an American-British novelist and screenwriter. In 1932, at the age of forty-four, Chandler became a detective fiction writer after losing his job as an oil company executive durin ...

updated the form with his private detective Philip Marlowe

Philip Marlowe () is a fictional character created by Raymond Chandler, who was characteristic of the hardboiled crime fiction genre. The hardboiled crime fiction genre originated in the 1920s, notably in ''Black Mask'' magazine, in which Dashiel ...

, who brought a more intimate voice to the detective than the more distanced "operative's report" style of Hammett's Continental Op stories. Despite struggling through the task of plotting a story, his cadenced dialogue and cryptic narrations were musical, evoking the dark alleys and tough thugs, rich women and powerful men about whom he wrote. Several feature and television movies have been made about the Philip Marlowe character. James Hadley Chase

James Hadley Chase (24 December 1906 ŌĆō 6 February 1985) was an English writer. While his birth name was Ren├® Lodge Brabazon Raymond, he was well known by his various pseudonyms, including James Hadley Chase, James L. Docherty, Raymond ...

wrote a few novels with private eyes as the main heroes, including ''Blonde's Requiem'' (1945), ''Lay Her Among the Lilies'' (1950), and ''Figure It Out for Yourself'' (1950). The heroes of these novels are typical private eyes, very similar to or plagiarizing Raymond Chandler's work.

Ross Macdonald, pseudonym of Kenneth Millar

Ross Macdonald was the main pseudonym used by the American-Canadian writer of crime fiction Kenneth Millar (; December 13, 1915 ŌĆō July 11, 1983). He is best known for his series of hardboiled novels set in Southern California and featur ...

, updated the form again with his detective Lew Archer

Lew Archer is a fictional character created by American-Canadian writer Ross Macdonald. Archer is a private detective working in Southern California. Between the late 1940s and the early '70s, the character appeared in 18 novels and a handful of ...

. Archer, like Hammett's fictional heroes, was a camera eye, with hardly any known past. "Turn Archer sideways, and he disappears," one reviewer wrote. Two of Macdonald's strengths were his use of psychology and his beautiful prose, which was full of imagery. Like other 'hardboiled

Hardboiled (or hard-boiled) fiction is a literary genre that shares some of its characters and settings with crime fiction (especially detective fiction and noir fiction). The genre's typical protagonist is a detective who battles the violence o ...

' writers, Macdonald aimed to give an impression of realism in his work through violence, sex and confrontation. The 1966 movie ''Harper

Harper may refer to:

Names

* Harper (name), a surname and given name

Places

;in Canada

* Harper Islands, Nunavut

*Harper, Prince Edward Island

;In the United States

*Harper, former name of Costa Mesa, California in Orange County

* Harper, Il ...

'' starring Paul Newman

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 ŌĆō September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, race car driver, philanthropist, and entrepreneur. He was the recipient of numerous awards, including an Academy Award, a BAFTA Award, three ...

was based on the first Lew Archer story ''The Moving Target

''The Moving Target'' is a detective novel by writer Ross Macdonald, first published by Alfred A. Knopf in April 1949.

The novel

''The Moving Target'' introduces the detective Lew Archer, who was eventually to figure in a further seventeen nove ...

'' (1949). Newman reprised the role in '' The Drowning Pool'' in 1976.

Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890ŌĆō1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930ŌĆō2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

, pseudonym of Dennis Lynds, is generally considered the author who led the form into the Modern Age. His PI, Dan Fortune, was consistently involved in the same sort of David-and-Goliath stories that Hammett, Chandler, and Macdonald wrote, but Collins took a sociological bent, exploring the meaning of his characters' places in society and the impact society had on people. Full of commentary and clipped prose, his books were more intimate than those of his predecessors, dramatizing that crime can happen in one's own living room.

The PI novel was a male-dominated field in which female authors seldom found publication until Marcia Muller

Marcia Muller (born September 28, 1944) is an American author of fictional mystery and thriller novels.

Muller has written many novels featuring her ''Sharon McCone'' female private detective character. ''Vanishing Point'' won the Shamus Awar ...

, Sara Paretsky

Sara Paretsky (born June 8, 1947) is an American author of detective fiction, best known for her novels focused on the protagonist V. I. Warshawski.

Life and career