Destruction Of Smyrna on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

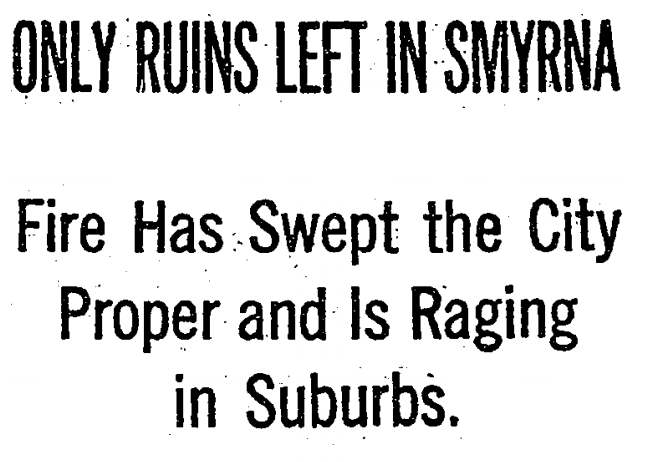

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of

Greece: A Jewish History

'. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008, p. 81. . Alongside Turks and Greeks, there were sizeable Armenian, Jewish, and

''International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe''

Taylor & Francis, 1995. , p. 351 According to the Ottoman census of 1906/7, there were 341,436 Muslims, 193,280 Greek Orthodox Christians, 12,273 Armenian Gregorian Christians, 24,633 Jews, 55,952 Foreigners totalling to 630,124 people in İzmir

''Ambassador Morgenthau's Story''

Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1918, p. 32. The American Consul General in Smyrna at the time,

At the outset, the Turkish occupation of the city was orderly. Though the Armenian and Greek inhabitants viewed their entry with trepidation, they reasoned that the presence of the Allied fleet would discourage any violence against the Christian community. On the morning of 9 September, no fewer than twenty-one Allied warships lay at anchor in Smyrna's harbor, including the British flagship, the battleships HMS ''Iron Duke'' and ''

At the outset, the Turkish occupation of the city was orderly. Though the Armenian and Greek inhabitants viewed their entry with trepidation, they reasoned that the presence of the Allied fleet would discourage any violence against the Christian community. On the morning of 9 September, no fewer than twenty-one Allied warships lay at anchor in Smyrna's harbor, including the British flagship, the battleships HMS ''Iron Duke'' and ''

The first fire broke out in the late afternoon of 13 September, four days after Turkish nationalist forces had entered the city. The blaze began in the Armenian quarter of the city (now the Basmane borough), and spread quickly due to the windy weather and the fact that no effort was made to put it out.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 49. Author

The first fire broke out in the late afternoon of 13 September, four days after Turkish nationalist forces had entered the city. The blaze began in the Armenian quarter of the city (now the Basmane borough), and spread quickly due to the windy weather and the fact that no effort was made to put it out.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 49. Author  The heat from the fire was so intense that Hepburn was worried that the refugees would die as a result of it. The refugees' situation on the pier on the morning of 14 September was described by the British Lieutenant A. S. Merrill, who believed that the Turks had set the fire to keep the Greeks in a state of terror so as to facilitate their departure:

The heat from the fire was so intense that Hepburn was worried that the refugees would die as a result of it. The refugees' situation on the pier on the morning of 14 September was described by the British Lieutenant A. S. Merrill, who believed that the Turks had set the fire to keep the Greeks in a state of terror so as to facilitate their departure:

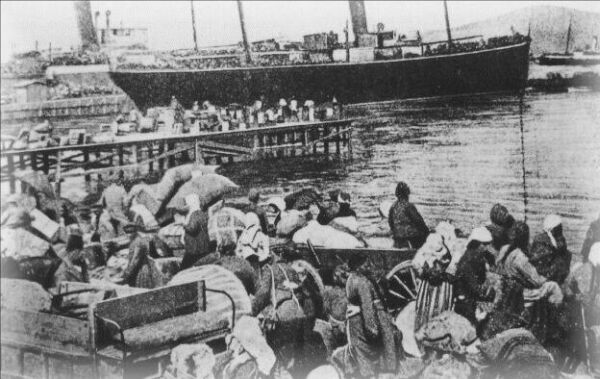

Turkish troops cordoned off the Quay to box the Armenians and Greeks within the fire zone and prevent them from fleeing. Eyewitness reports describe panic-stricken refugees diving into the water to escape the flames and that their terrified screaming could be heard miles away. By 15 September the fire had somewhat died down, but sporadic violence by the Turks against the Greek and Armenian refugees kept the pressure on the Western and Greek navies to remove the refugees as quickly as possible.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 51. The fire was completely extinguished by 22 September, and on 24 September the first Greek ships – part of a flotilla organized and commandeered by the American humanitarian

Turkish troops cordoned off the Quay to box the Armenians and Greeks within the fire zone and prevent them from fleeing. Eyewitness reports describe panic-stricken refugees diving into the water to escape the flames and that their terrified screaming could be heard miles away. By 15 September the fire had somewhat died down, but sporadic violence by the Turks against the Greek and Armenian refugees kept the pressure on the Western and Greek navies to remove the refugees as quickly as possible.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 51. The fire was completely extinguished by 22 September, and on 24 September the first Greek ships – part of a flotilla organized and commandeered by the American humanitarian

The evacuation was difficult despite the efforts of British and American sailors to maintain order, as tens of thousands of refugees pushed and shoved towards the shore. Attempts to organize relief were made by the American officials from the

The evacuation was difficult despite the efforts of British and American sailors to maintain order, as tens of thousands of refugees pushed and shoved towards the shore. Attempts to organize relief were made by the American officials from the

The question of who was responsible for starting the burning of Smyrna continues to be debated, with Turkish sources mostly attributing responsibility to Greeks or Armenians, and vice versa. Other sources, on the other hand, suggest that at the very least, Turkish inactivity played a significant part on the event.

A number of studies have been published on the Smyrna fire. Professor of literature

The question of who was responsible for starting the burning of Smyrna continues to be debated, with Turkish sources mostly attributing responsibility to Greeks or Armenians, and vice versa. Other sources, on the other hand, suggest that at the very least, Turkish inactivity played a significant part on the event.

A number of studies have been published on the Smyrna fire. Professor of literature

The number of casualties from the fire is not precisely known, with estimates of up to 125,000 Greeks and Armenians killed., p. 233. American historian Norman Naimark gives a figure of 10,000–15,000 dead, while historian Richard Clogg gives a figure of 30,000. Larger estimates include that of John Freely at 50,000 and Rudolf Rummel at 100,000.

Help to the city's population by ships of the

The number of casualties from the fire is not precisely known, with estimates of up to 125,000 Greeks and Armenians killed., p. 233. American historian Norman Naimark gives a figure of 10,000–15,000 dead, while historian Richard Clogg gives a figure of 30,000. Larger estimates include that of John Freely at 50,000 and Rudolf Rummel at 100,000.

Help to the city's population by ships of the  Many refugees were rescued via an impromptu relief flotilla organized by American missionary

Many refugees were rescued via an impromptu relief flotilla organized by American missionary

Two Armenian Physicians in Smyrna: Case Studies in Survival

" in ''Armenian Smyrna/Izmir: The Aegean Communities,'' ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2012. * Calonne, David Stephen. "Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, and Smyrna 1922," in ''Armenian Smyrna/Izmir: The Aegean Communities''.

Association of Smyrneans

Remembering Smyrna/Izmir: Shared History, Shared Trauma

Levantine Heritage

''Smyrna 1922''

a rare film, on Vimeo – shows before and after the fire {{DEFAULTSORT:Great Fire Of Smyrna Occupation of Smyrna Fires in Turkey Greek genocide Aftermath of the Armenian genocide 1922 fires in Europe 1922 in the Ottoman Empire 20th-century controversies Mass murder in 1922 September 1922 events Massacres in Turkey Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) Urban fires in Asia 1920s murders in Turkey 1922 crimes in the Ottoman Empire Events in İzmir 1922 disasters in the Ottoman Empire

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

(modern İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban agglo ...

, Turkey) in September 1922. Eyewitness reports state that the fire began on 13 September 1922Horton, George. ''The Blight of Asia

George Horton (October 11, 1859 – June 5, 1942) was a member of the United States diplomatic corps who held several consular offices in Greece and the Ottoman Empire between 1893 and 1924. During two periods he was the U.S. Consul or Consul Ge ...

''. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1926; repr. London: Gomidas Institute

The Gomidas Institute (GI; hy, ԿԻ) is an independent academic institution "dedicated to modern Armenian and regional studies." Its activities include research, publications and educational programmes. It publishes documents, monographs, memoir ...

, 2003, p. 96. and lasted until it was largely extinguished on 22 September. It began four days after the Turkish military captured the city on 9 September, effectively ending the Greco-Turkish War, more than three years after the landing of Greek army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

troops at Smyrna on 15 May 1919. Estimated Greek and Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

deaths resulting from the fire range from 10,000 to 125,000.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 52.

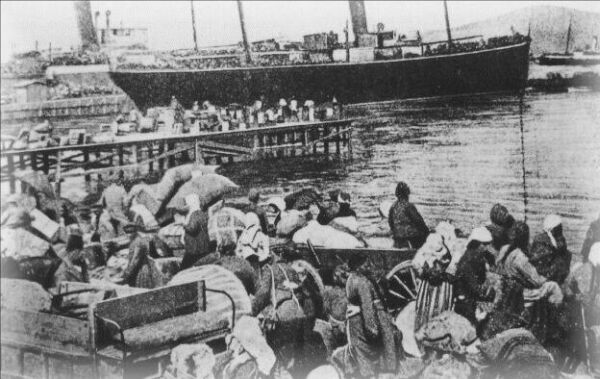

Approximately 80,000 to 400,000 Greek and Armenian refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s crammed the waterfront to escape from the fire. They were forced to remain there under harsh conditions for nearly two weeks. Turkish troops and irregulars had started committing massacres and atrocities against the Greek and Armenian population in the city before the outbreak of the fire. Many women were rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ...

d. Tens of thousands of Greek and Armenian men were subsequently deported

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

into the interior of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, where most of them died in harsh conditions.

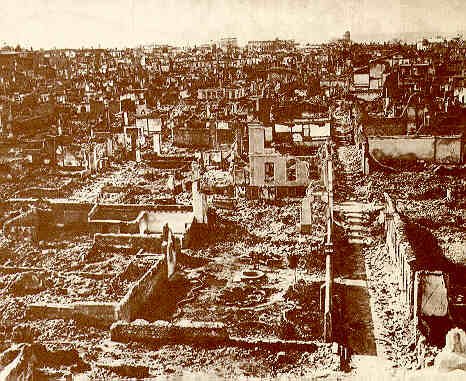

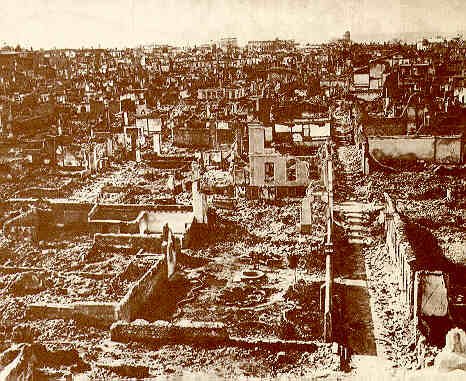

The fire completely destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city; the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

quarters escaped damage. There are different accounts and eyewitness reports about who was responsible for the fire; most sources and scholars attribute it to Turkish soldiers setting fire to Greek and Armenian homes and businesses,For example, see: , via the Internet Archive while a few, Turkish or pro-Turkish, sources hold that the Greeks and Armenians started the fire either to tarnish the Turks' reputation or deny them access to their former homes and businesses.Heath W. Lowry

Heath Ward Lowry (born 23 December 1942) is the Atatürk Professor of Ottoman and Modern Turkish Studies emeritus at Princeton University and Bahçeşehir University. He is an author of books about the history of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Tur ...

, “Turkish history: On Whose Sources Will it Be Based? A Case Study on the Burning of Izmir”, ''Journal of Ottoman Studies'' 9 (1989): 1–29. Testimonies from Western eyewitnesses were printed in many Western newspapers.

Background

The ratio ofChristian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

population to Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

population remains a matter of dispute, but the city was a multicultural and cosmopolitan center until September 1922. Different sources claim either Greeks or Turks as constituting the majority in the city. According to Katherine Elizabeth Flemming, in 1919–1922 the Greeks in Smyrna numbered 150,000, forming just under half of the population, outnumbering the Turks by a ratio of two to one.Fleming Katherine Elizabeth. Greece: A Jewish History

'. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008, p. 81. . Alongside Turks and Greeks, there were sizeable Armenian, Jewish, and

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

ine communities in the city. According to Trudy Ring, before World War I the Greeks alone numbered 130,000 out of a population of 250,000, excluding Armenians and other Christians.Ring Trudy, Salkin Robert M., La Boda Sharon''International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe''

Taylor & Francis, 1995. , p. 351 According to the Ottoman census of 1906/7, there were 341,436 Muslims, 193,280 Greek Orthodox Christians, 12,273 Armenian Gregorian Christians, 24,633 Jews, 55,952 Foreigners totalling to 630,124 people in İzmir

Sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian language, Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian language, Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησι� ...

(13 Kazas including the central Kaza

A kaza (, , , plural: , , ; ota, قضا, script=Arab, (; meaning 'borough')

* bg, околия (; meaning 'district'); also Кааза

* el, υποδιοίκησις () or (, which means 'borough' or 'municipality'); also ()

* lad, kaza

, ...

); the updated figures for 1914 gave 100,356 Muslims, 73.676 Greek Orthodox Christians, 10,061 Armenian Gregorians, 813 Armenian Catholics, 24,069 Jews for the central kaza of İzmir.Salâhi R. Sonyel, ''Minorities and the Destruction of the Ottoman Empire'', Ankara: TTK, 1993, p. 351; Gaston Gaillard, ''The Turks and Europe'', London, 1921, p. 199.

According to the U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire

The United States has maintained many high level contacts with Turkey since the 19th century.

Ottoman Empire

Chargé d'Affaires

*George W. Erving (before 1831)

* David Porter (September 13, 1831 – May 23, 1840)

Minister Resident

* David Port ...

at the time, Henry Morgenthau Henry Morgenthau may refer to:

* Henry Morgenthau Sr. (1856–1946), United States diplomat

* Henry Morgenthau Jr. (1891–1967), United States Secretary of the Treasury

* Henry Morgenthau III (1917–2018), author and television producer of ''Screa ...

, more than half of Smyrna's population was Greek.Morgenthau Henry''Ambassador Morgenthau's Story''

Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1918, p. 32. The American Consul General in Smyrna at the time,

George Horton

George Horton (October 11, 1859 – June 5, 1942) was a member of the United States diplomatic corps who held several consular offices in Greece and the Ottoman Empire between 1893 and 1924. During two periods he was the U.S. Consul or Consul Ge ...

, wrote that before the fire there were 400,000 people living in the city of Smyrna, of whom 165,000 were Turks, 150,000 were Greeks, 25,000 were Jews, 25,000 were Armenians, and 20,000 were foreigners—10,000 Italians, 3,000 French, 2,000 British, and 300 Americans. Most of the Greeks and Armenians were Christians.

Moreover, according to various scholars, prior to the war, the city was a center of more Greeks than lived in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, the capital of Greece. The Ottomans of that era referred to the city as ''Infidel Smyrna'' (''Gavur

Giaour or Gawur (; tr, gâvur, ; from fa, گور ''gâvor'' an obsolete variant of modern گبر ''gabr, gaur'', originally derived from arc, 𐡂𐡁𐡓𐡀, ''gaḇrā'', man; person; ro, ghiaur; al, kaur; gr, γκιαούρης, gkiao� ...

Izmir'') due to the numerous Greeks and the large non-Muslim population.

Events

Entry of the Turkish Army

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on the evening of Friday 8 September. The first elements of Mustafa Kemal's forces, a Turkish cavalry squadron, made its way into the city from the northern tip of the quay the following morning, establishing their headquarters at the main government building called ''Konak''. The Greek Army was in disarray and could not evacuate the city in an orderly manner, and fighting continued to the next day. According to the General of the 5th Cavalry SidearmyFahrettin Altay

Fahrettin Altay (12 January 1880 – 25 October 1974) was a Turkish military officer. The Turkish tank Altay is named in honor of him.

Biography

Fahrettin Altay was born to Lieutenant Colonel İsmail Bey, son of Hacı Ahmet Efendi from İz ...

, on the 10th of September, Turkish forces belonging to the 2nd and the 3rd Cavalry regiments captured around 3,000 Greek soldiers, 50 Greek Officers, including a Brigadier Commander in the south of the city center who were retreating from Aydın. Lieutenant Ali Rıza Akıncı, the first Turkish officer to hoist the Turkish flag

The national flag of Turkey, officially the Turkish flag ( tr, Türk bayrağı), is a red flag featuring a white star and crescent. The flag is often called "the red flag" (), and is referred to as "the red banner" () in the Turkish national a ...

in the Liberation of Izmir

The Turkish Capture of Smyrna, or the Liberation of İzmir ( tr, İzmir'in Kurtuluşu) marked the end of the 1919–1922 Greco-Turkish War, and the culmination of the Turkish War of Independence. On 9 September 1922, following the headlong ret ...

on the 9th of September, mentions in his memoirs that his unit of 13 cavalrymen was ambushed by a volley of fire from 30-40 rifles from the Tuzakoğlu factory after being saluted and congratulated by a French Marine platoon in the Halkapınar bridge. This volley fire killed 3 cavalrymen instantly and fatally wounded another. They were relieved by Captain Şerafettin and his 2 units which encircled the factory. Moreover, Captain Şerafettin, alongside Lieutenant Ali Rıza Akıncı were wounded by a grenade thrown by a Greek soldier in front of the Pasaport building. The Lieutenant was wounded lightly from his nose and his leg, and his horse from its belly. The grenade thrower was also mentioned by George Horton as "''some fool threw a bomb''", and that the commander of this unit "''received bloody cuts about the head''". A monument was later erected on the spot these cavalrymen had fallen. Military command was first assumed by Mürsel Pasha, and then Nureddin Pasha

Nureddin Ibrahim Pasha ( tr, Nurettin Paşa, Nureddin İbrahim Paşa; 1873 – 18 February 1932), known as Nureddin İbrahim Konyar from 1934, was a Turkish military officer who served in the Ottoman Army during World War I and in the Turkis ...

, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

of the Turkish First Army

The First Army of the Republic of Turkey () is one of the four field armies of the Turkish Army. Its headquarters is located at Selimiye Barracks in Istanbul. It guards the sensitive borders of Turkey with Greece and Bulgaria, including the st ...

.

At the outset, the Turkish occupation of the city was orderly. Though the Armenian and Greek inhabitants viewed their entry with trepidation, they reasoned that the presence of the Allied fleet would discourage any violence against the Christian community. On the morning of 9 September, no fewer than twenty-one Allied warships lay at anchor in Smyrna's harbor, including the British flagship, the battleships HMS ''Iron Duke'' and ''

At the outset, the Turkish occupation of the city was orderly. Though the Armenian and Greek inhabitants viewed their entry with trepidation, they reasoned that the presence of the Allied fleet would discourage any violence against the Christian community. On the morning of 9 September, no fewer than twenty-one Allied warships lay at anchor in Smyrna's harbor, including the British flagship, the battleships HMS ''Iron Duke'' and ''King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

'', along with their escort of cruisers and destroyers under the command of Admiral Osmond Brock

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Osmond de Beauvoir Brock, (5 January 1869 – 15 October 1947) was a Royal Navy officer. Brock served as assistant director of naval intelligence and then as assistant director of naval mobilisation at the Admiralty in t ...

; the American destroyers USS ''Litchfield'', ''Simpson

Simpson most often refers to:

* Simpson (name), a British surname

*''The Simpsons'', an animated American sitcom

**The Simpson family, central characters of the series ''The Simpsons''

Simpson may also refer to:

Organizations Schools

*Simpso ...

'', and ''Lawrence

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

'' (later joined by the '' Edsall''); three French cruisers and two destroyers under the command of Admiral Dumesnil; and an Italian cruiser and destroyer. As a precaution, sailors and marines from the Allied fleet were landed ashore to guard their respective diplomatic compounds and institutions with strict orders of maintaining neutrality in the event that violence would break out between the Turks and the Christians.

On 9 September, order and discipline began to break down among the Turkish troops, who began systematically targeting the Armenian population, pillaging their shops, looting their homes, separating the men from the women and carrying away and sexually assaulting the latter.Clogg, ''A Concise History of Greece'', p. 98.Dobkin. ''Smyrna 1922'', pp. 120–167. The Greek Orthodox Metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis.

Originally, the term referred to the b ...

, Chrysostomos, was tortured and hacked to death by a Turkish mob in full view of French soldiers, who were prevented from intervening by their commanding officer, and much to Admiral Dumesnil's approval. Refuge was sought wherever possible, including Paradise, where the American quarter was located, and the European quarters. Some were able to take shelter at the American Collegiate Institute and other institutions, despite strenuous efforts to turn away those seeking help by the Americans and Europeans, who were anxious not to antagonize or harm their relations with the leaders of the Turkish National movement. An officer of the Dutch steamer ''Siantar'' which was at the city's port during that period reported an incident that he has heard, according to him after the Turkish troops had entered the city a large hotel which had Greek guests was set on fire, the Turks had placed a machine gun at the opposite of the hotel's entrance and opened fire when people were trying to exit the burning building. In addition, he said that the crew were not allowed to go offshore after dusk because thugs were roaming the city's streets and it was dangerous.

Victims of the massacres committed by the Turkish army and irregulars were also foreign citizens. On 9 September, Dutch merchant Oscar de Jongh and his wife were murdered by Turkish cavalrymen, while in another incident a retired British doctor was beaten to death in his home, while trying to prevent the rape of a servant girl.

Burning

The first fire broke out in the late afternoon of 13 September, four days after Turkish nationalist forces had entered the city. The blaze began in the Armenian quarter of the city (now the Basmane borough), and spread quickly due to the windy weather and the fact that no effort was made to put it out.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 49. Author

The first fire broke out in the late afternoon of 13 September, four days after Turkish nationalist forces had entered the city. The blaze began in the Armenian quarter of the city (now the Basmane borough), and spread quickly due to the windy weather and the fact that no effort was made to put it out.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 49. Author Giles Milton

Giles Milton FRHistS (born 15 January 1966) is a British writer who specialises in narrative history. His books have sold more than one million copies in the UK. and been published in twenty-five languages. He has written twelve works of non-fi ...

writes:

Others, such as Claflin Davis of the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the desi ...

and Monsieur Joubert, director of the Credit Foncier Bank of Smyrna, also witnessed the Turks putting buildings to the torch. When the latter asked the soldiers what they were doing, "They replied impassively that they were under orders to blow up and burn all the houses of the area." The city's fire brigade did its best to combat the fires but by Wednesday 13 September so many were being set that it was unable to keep up. Two firemen from the brigade, a Sgt. Tchorbadjis and Emmanuel Katsaros, would later testify in court witnessing Turkish soldiers setting fire to the buildings. When Katsaros complained, one of them commented, "You have your orders...and we have ours. This is Armenian property. ''Our'' orders are to set fire to it." The spreading fire caused a stampede of people to flee toward the quay, which stretched from the western end of the city to its northern tip, known as the Point. Captain Arthur Japy Hepburn, chief of Staff of the American naval squadron, described the panic on the quay:

The heat from the fire was so intense that Hepburn was worried that the refugees would die as a result of it. The refugees' situation on the pier on the morning of 14 September was described by the British Lieutenant A. S. Merrill, who believed that the Turks had set the fire to keep the Greeks in a state of terror so as to facilitate their departure:

The heat from the fire was so intense that Hepburn was worried that the refugees would die as a result of it. The refugees' situation on the pier on the morning of 14 September was described by the British Lieutenant A. S. Merrill, who believed that the Turks had set the fire to keep the Greeks in a state of terror so as to facilitate their departure:

Turkish troops cordoned off the Quay to box the Armenians and Greeks within the fire zone and prevent them from fleeing. Eyewitness reports describe panic-stricken refugees diving into the water to escape the flames and that their terrified screaming could be heard miles away. By 15 September the fire had somewhat died down, but sporadic violence by the Turks against the Greek and Armenian refugees kept the pressure on the Western and Greek navies to remove the refugees as quickly as possible.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 51. The fire was completely extinguished by 22 September, and on 24 September the first Greek ships – part of a flotilla organized and commandeered by the American humanitarian

Turkish troops cordoned off the Quay to box the Armenians and Greeks within the fire zone and prevent them from fleeing. Eyewitness reports describe panic-stricken refugees diving into the water to escape the flames and that their terrified screaming could be heard miles away. By 15 September the fire had somewhat died down, but sporadic violence by the Turks against the Greek and Armenian refugees kept the pressure on the Western and Greek navies to remove the refugees as quickly as possible.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 51. The fire was completely extinguished by 22 September, and on 24 September the first Greek ships – part of a flotilla organized and commandeered by the American humanitarian Asa Jennings

Asa Kent Jennings (1877–1933) was a Methodist pastor from upstate New York and a member of the YMCA. In 1904, while in his twenties, Jennings was struck down by Pott's disease, a type of tuberculosis which affects the spine. As a result of his t ...

– entered the harbor to take passengers away, following Captain Hepburn's initiative and his having obtained permission and cooperation from the Turkish authorities and the British admiral in command of the destroyers in the harbor.Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', p. 50.

Aftermath

The evacuation was difficult despite the efforts of British and American sailors to maintain order, as tens of thousands of refugees pushed and shoved towards the shore. Attempts to organize relief were made by the American officials from the

The evacuation was difficult despite the efforts of British and American sailors to maintain order, as tens of thousands of refugees pushed and shoved towards the shore. Attempts to organize relief were made by the American officials from the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

and YWCA

The Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) is a nonprofit organization with a focus on empowerment, leadership, and rights of women, young women, and girls in more than 100 countries.

The World office is currently based in Geneva, Swi ...

, who were reportedly robbed and later shot at by Turkish soldiers. On the quay, Turkish soldiers and irregulars periodically robbed Greek refugees, beating some and arresting others who resisted. Though there were several reports of well-behaved Turkish troops helping old women and trying to maintain order among the refugees, these are heavily outnumbered by those describing gratuitous cruelty, incessant robbery and violence.

American and British attempts to protect the Greeks from the Turks did little good, with the fire having taken a terrible toll. Some frustrated and terrified Greeks took their own lives, plunging into the water with packs at their back, children were stampeded, and many of the elderly fainted and died. The city's Armenians also suffered grievously, and according to Captain Hepburn, "every able-bodied Armenian man was hunted down and killed wherever found, with even boys aged 12 to 15 taking part in the hunt."

The fire completely destroyed the Greek, Armenian, and Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

ine quarters of the city, with only the Turkish and Jewish quarters surviving. The thriving port of Smyrna, one of the most commercially active in the region, was burned to the ground. Some 150,000–200,000 Greek refugees were evacuated, while approximately 30,000 able-bodied Greek and Armenian men were deported to the interior, many of them dying under the harsh conditions or executed along the way. The 3,000-year Greek presence on Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

's Aegean shore was brought to an abrupt end, along with the Megali Idea. The Greek writer Dimitris Pentzopoulos wrote, "It is no exaggeration to call the year '1922' the most calamitous in modern Hellenic history."

Responsibility

The question of who was responsible for starting the burning of Smyrna continues to be debated, with Turkish sources mostly attributing responsibility to Greeks or Armenians, and vice versa. Other sources, on the other hand, suggest that at the very least, Turkish inactivity played a significant part on the event.

A number of studies have been published on the Smyrna fire. Professor of literature

The question of who was responsible for starting the burning of Smyrna continues to be debated, with Turkish sources mostly attributing responsibility to Greeks or Armenians, and vice versa. Other sources, on the other hand, suggest that at the very least, Turkish inactivity played a significant part on the event.

A number of studies have been published on the Smyrna fire. Professor of literature Marjorie Housepian Dobkin

Marjorie Anaïs Housepian Dobkin () was an author and an English professor at Barnard College, Columbia University, New York. Her books include the novel ''A Houseful of Love'' (a '' New York Times'' and ''New York Herald Tribune'' bestseller) an ...

's 1971 study ''Smyrna 1922'' concluded that the Turkish army systematically burned the city and killed Christian Greek and Armenian inhabitants. Her work is based on extensive eyewitness testimony from survivors, Allied troops sent to Smyrna during the evacuation, foreign diplomats, relief workers, and Turkish eyewitnesses. A study by historian Niall Ferguson comes to the same conclusion. Historian Richard Clogg categorically states that the fire was started by the Turks following their capture of the city. In his book ''Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922'', Giles Milton addresses the issue of the Smyrna Fire through original material (interviews, unpublished letters, and diaries) from the Levantine families of Smyrna, who were mainly of British origin. The conclusion of the author is that it was Turkish soldiers and officers who set the fire, most probably acting under direct orders. British scholar Michael Llewellyn-Smith

Sir Michael John Llewellyn-Smith (born 25 April 1939) is a retired British diplomat and academic. He served as Ambassador to Poland from 1991 to 1996 and Ambassador to Greece from 1996 to 1999. He is visiting professor at the Centre for Helleni ...

, writing on the Greek administration in Asia Minor, also concluded that the fire was "probably lit" by the Turks as indicated by what he called "what evidence there is."

Stanford historian Norman Naimark

Norman M. Naimark (; born 1944, New York City) is an American historian. He is the Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of Eastern European Studies at Stanford University, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. He writes on modern Easte ...

has evaluated the evidence regarding the responsibility of the fire. He agrees with the view of American Lieutenant Merrill that it was in Turkish interests to terrorize Greeks into leaving Smyrna with the fire, and points out to the "odd" fact that the Turkish quarter was spared from the fire as a factor suggesting Turkish responsibility. However, he points out that there is no "solid and substantial evidence" of this and that it can be argued that burning the city was against Turkish interests and was unnecessary. He also suggests that the responsibility may lie with Greeks and Armenians as they "had own their good reasons", pointing out to the "Greek history of retreating" and "Armenian attack in the first day of the occupation".Naimark, ''Fires of Hatred'', pp. 47–52. However, the Greek army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

departed from Smyrna on 9 September 1922, when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

and his army entered the city, while the fire began four days later, on 13 September 1922.

Horton and Housepian are criticized by Heath Lowry and Justin McCarthy, who argue that Horton was highly prejudiced and Housepian makes an extremely selective use of sources. Lowry and McCarthy were both members of the now defunct Institute of Turkish Studies The Institute of Turkish Studies (ITS) is a foundation based in the United States with the avowed objective of advancing Turkish studies at colleges and universities in the United States. Having been founded and provided a grant from the Republic of ...

and have in turn been strongly criticized by other scholars for their denial of the Armenian Genocide

Armenian genocide denial is the claim that the Ottoman Empire and its ruling party, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), did not commit genocide against its Armenian citizens during World War I—a crime documented in a large body of ...

Auron, Yair. ''The Banality of Denial: Israel and the Armenian Genocide''. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 2003, p. 248. Hovannisian, Richard G. "Denial of the Armenian Genocide in Comparison with Holocaust Denial" in ''Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide''. Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999, p. 210. and McCarthy has been described by Michael Mann

Michael Kenneth Mann (born February 5, 1943) is an American director, screenwriter, and producer of film and television who is best known for his distinctive style of crime drama. His most acclaimed works include the films ''Thief'' (1981), ' ...

as being on "the Turkish side of the debate."

Turkish author and journalist Falih Rıfkı Atay

Falih Rıfkı Atay (1894– 20 March 1971) was a Turkish journalist, writer and politician between 1923 and 1950.

Biography

Falih Rıfkı was the son of Halil Hilmi Efendi, an imam. He was educated in Istanbul, Ottoman Empire. Falih began his ...

, who was in Smyrna at the time, and the Turkish professor Biray Kolluoğlu Kırlı agreed that Turkish nationalist forces were responsible for the destruction of Smyrna in 1922. More recently, a number of non-contemporary scholars, historians, and politicians have added to the history of the events by revisiting contemporary communications and histories. Leyla Neyzi, in her work on the oral history regarding the fire, makes a distinction between Turkish nationalist discourse and local narratives. In the local narratives, she points out to the Turkish forces being held responsible for at least not attempting to extinguish the fire effectively, or, at times, being held responsible for the fire itself.

Casualties and refugees

The number of casualties from the fire is not precisely known, with estimates of up to 125,000 Greeks and Armenians killed., p. 233. American historian Norman Naimark gives a figure of 10,000–15,000 dead, while historian Richard Clogg gives a figure of 30,000. Larger estimates include that of John Freely at 50,000 and Rudolf Rummel at 100,000.

Help to the city's population by ships of the

The number of casualties from the fire is not precisely known, with estimates of up to 125,000 Greeks and Armenians killed., p. 233. American historian Norman Naimark gives a figure of 10,000–15,000 dead, while historian Richard Clogg gives a figure of 30,000. Larger estimates include that of John Freely at 50,000 and Rudolf Rummel at 100,000.

Help to the city's population by ships of the Hellenic Navy

The Hellenic Navy (HN; el, Πολεμικό Ναυτικό, Polemikó Naftikó, War Navy, abbreviated ΠΝ) is the naval force of Greece, part of the Hellenic Armed Forces. The modern Greek navy historically hails from the naval forces of vari ...

was limited, as the 11 September 1922 Revolution

The 11 September 1922 Revolution ( el, Επανάσταση της 11ης Σεπτεμβρίου 1922) was an uprising by the Greek army and navy against the government in Athens. The revolution took place on 24 September 1922, although the date wa ...

had broken out, and the most of the Greek army was concentrated at the islands of Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

and Lesbos, planning to overthrow the royalist government of Athens.

Although there were numerous ships from various Allied powers in the harbor of Smyrna, the vast majority of them cited neutrality and did not pick up Greeks and Armenians who were forced to flee from the fire and the Turkish troops retaking the city after the Greek army's defeat. Military bands played loud music to drown out the screams of those who were drowning in the harbor and who were forcefully prevented from boarding Allied ships.Dobkin. ''Smyrna 1922'', p. 71. A Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

ese freighter dumped all of its cargo and took on as many refugees as possible, taking them to the Greek port of Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

.

Many refugees were rescued via an impromptu relief flotilla organized by American missionary

Many refugees were rescued via an impromptu relief flotilla organized by American missionary Asa Jennings

Asa Kent Jennings (1877–1933) was a Methodist pastor from upstate New York and a member of the YMCA. In 1904, while in his twenties, Jennings was struck down by Pott's disease, a type of tuberculosis which affects the spine. As a result of his t ...

. Other scholars give a different account of the events; they argue that the Turks first forbade foreign ships in the harbor to pick up the survivors, but, under pressure especially from Britain, France, and the United States, they allowed the rescue of all the Christians except males 17 to 45 years old. They intended to deport the latter into the interior, which "was regarded as a short life sentence to slavery under brutal masters, ended by mysterious death".

The number of refugees changes according to the source. Some contemporary newspapers claim that there were 400,000 Greek and Armenian refugees from Smyrna and the surrounding area who received Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

aid immediately after the destruction of the city."U.S. Red Cross Feeding 400,000 Refugees," ''Japan Times and Mail'', 10 November 1922. Stewart Matthew states that there were 250,000 refugees who were all non-Turks. Naimark gives a figure of 150,000–200,000 Greek refugees evacuated. Edward Hale Bierstadt and Helen Davidson Creighton say that there were at least 50,000 Greek and Armenian refugees.Edward Hale Bierstadt, Helen Davidson Creighton. ''The Great betrayal: A Survey of the Near East Problem''. R. M. McBride & Company, 1924, p. 218. Some contemporary accounts also suggest the same number.

The number of Greek and Armenian men deported to the interior of Anatolia and the number of consequent deaths varies across sources. Naimark writes that 30,000 Greek and Armenian men were deported there, where most of them died under brutal conditions. Dimitrije Đorđević puts the number of deportees at 25,000 and the number of deaths at labour battalions at 10,000. David Abulafia

David Abulafia (born 12 December 1949) is an English historian with a particular interest in Italy, Spain and the rest of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. He spent most of his career at the University of Cambridge, ris ...

states that at least 100,000 Greeks were forcibly sent to the interior of Anatolia, where most of them died.

Aristotle Onassis

Aristotle Socrates Onassis (, ; el, Αριστοτέλης Ωνάσης, Aristotélis Onásis, ; 20 January 1906 – 15 March 1975), was a Greek-Argentinian shipping magnate who amassed the world's largest privately-owned shipping fleet and wa ...

, who was born in Smyrna and who later became one of the richest men in the world, was one of the Greek survivors. The various biographies of his life document aspects of his experiences during the Smyrna catastrophe. His life experiences were featured in the TV movie called ''Onassis, The Richest Man in the World''.''Onassis, The Richest Man in the World'' (1988), movie for television, directed by Waris Hussein.

During the Smyrna catastrophe, the Onassis family lost substantial property holdings, which were either taken or given to Turks as bribes to secure their safety and freedom. They became refugees

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

, fleeing to Greece after the fire. However, Aristotle Onassis stayed behind to save his father, who had been placed in a Turkish concentration camp. He was successful in saving his father's life. During this period three of his uncles died. He also lost an aunt, her husband Chrysostomos Konialidis, and their daughter, who were burned to death when Turkish soldiers set fire to a church in Thyatira

Thyateira (also Thyatira) ( grc, Θυάτειρα) was the name of an ancient Greek city in Asia Minor, now the modern Turkish city of Akhisar ("white castle"). The name is probably Lydian. It lies in the far west of Turkey, south of Istanbul ...

, where 500 Christians had found shelter to avoid Turkish soldiers and the burning of Smyrna.

Aftermath

The entire city suffered substantial damage to its infrastructure. The core of the city literally had to be rebuilt from the ashes. Today, 40 hectares of the former fire area is a vast park namedKültürpark

Kültürpark is an urban park in İzmir, Turkey. It is located in the district of Konak, roughly bounded by Dr. Mustafa Enver Bey Avenue on the north, 1395th Street, 1396th Street and Bozkurt Avenue on the east, Mürsel Paşa Boulevard on the sou ...

serving as Turkey's largest open air exhibition center, including the İzmir International Fair

The İzmir International Fair ( tr, İzmir Enternasyonal Fuarı) is the oldest tradeshow in Turkey, considered the cradle of Turkey's fairs and expositions industry, and is also notable for hosting a series of simultaneous festival activities. Th ...

, among others.

According to the first census in Turkey after the war, the total population of the city in 1927 was 184,254, of whom 162,144 (88%) were Muslims, the remainder numbering 22,110.

In art, music and literature

* Robert Byron's travelogue ''Europe in the Looking Glass'' (1926) contains an eyewitness report, placing the blame for the fire upon the Turks. * "On the Quai at Smyrna

"On the Quai at Smyrna" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, first published in the 1930 Scribner's edition of the '' In Our Time'' collection of short stories, then titled "Introduction by the author".Oliver (1999), 251 Accompanying it w ...

" (1930), a short story published as part of ''In Our Time In Our Time may refer to:

* ''In Our Time'' (1944 film), a film starring Ida Lupino and Paul Henreid

* ''In Our Time'' (1982 film), a Taiwanese anthology film featuring director Edward Yang; considered the beginning of the "New Taiwan Cinema"

* ''In ...

'', by Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

, alludes to the fire of Smyrna:

* Eric Ambler

Eric Clifford Ambler OBE (28 June 1909 – 22 October 1998) was an English author of thrillers, in particular spy novels, who introduced a new realism to the genre. Also working as a screenwriter, Ambler used the pseudonym Eliot Reed for book ...

's novel ''The Mask of Dimitrios

''The Mask of Dimitrios'' is a 1944 American film noir directed by Jean Negulesco and written by Frank Gruber, based on the 1939 novel of the same title written by Eric Ambler (in the United States, it was published as ''A Coffin for Dimitrios'' ...

'' (1939) details the events at Smyrna at the opening of chapter 3.

* The closing section of Edward Whittemore

Edward Payson Whittemore (May 26, 1933 – August 3, 1995) was an American novelist, the author of five novels written between 1974 and 1987, including the highly praised series ''Jerusalem Quartet.'' He had started his career as a case offi ...

's '' Sinai Tapestry'' (1977) takes place during the burning of Smyrna.

* Part of the novel ''The Titan'' (1985) by Fred Mustard Stewart

Fred Mustard Stewart (September 17, 1932, Anderson, Indiana – February 7, 2007, New York City) was an American novelist. His most popular books were ''The Mephisto Waltz'' (1969), adapted for the 1971 film of the same name starring Alan Alda ...

takes place during the burning of Smyrna.

* Susanna de Vries

Susanna de Vries AM (born 6 October 1936) is an Australian historian, writer, and former academic. She has published more than twenty books, making her one of Queensland's most published authors. The majority of these detail the bravery and h ...

''Blue Ribbons Bitter Bread'' (2000) is an account of Smyrna and the Greek refugees who landed at Thessaloniki.

* The novel ''Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

'' (2002) by American Jeffrey Eugenides opens with the burning of Smyrna.

* Mehmet Coral's ''İzmir: 13 Eylül 1922'' ("Izmir: 13 September 1922") (2003?) addressed this topic; it was also published in the Greek language by Kedros of Athens/Greece under the title: Πολλές ζωές στη Σμύρνη (Many lives in Izmir).

* Greek-American singer-songwriter Diamanda Galas's album '' Defixiones: Will and Testament'' (2003) is directly inspired by the Turkish atrocities committed against the Greek population at Smyrna. Galas is descended from a family who originated from Smyrna.

* Part of the novel ''Birds Without Wings'' (2004) by Louis De Bernieres Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis (d ...

takes place during the burning of Smyrna and its aftermath.

* Panos Karnezis

Panagiotis Karnezis ( el, Παναγιώτης (Πάνος) Καρνέζης; born 1967 in Amaliada), known as Panos Karnezis, is a Greek writer. Born in Greece, he moved to England in 1992 to study Engineering. He was later awarded a M.A. in Crea ...

's 2004 novel '' The Maze'' deals with historical events involving and related to the fire at Smyrna.

* "Smyrna: The Destruction of a Cosmopolitan City – 1900–1922", a 2012 documentary film by Maria Ilioú.

* Deli Sarkis Sarkisian's personal account of the fire of Smyrna is related in Ellen Sarkisian Chesnut's ''The Scars He Carried, A Daughter Confronts The Armenian Genocide and Tells Her Father's Story'' (2014).

* ''Smyrna in Flames'' (2021) by Homero Aridjis

Homero Aridjis (born April 6, 1940) is a Mexican poet, novelist, environmental activist, journalist and diplomat known for his rich imagination, poetry of lyrical beauty, and ethical independence.

Family and early life

Aridjis was born in Contepe ...

, is a historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

inspired by the written recollections and memories of the author's father, Nicias Aridjis; a captain in the Greek army during the Smyrna Catastrophe.

* ''Smyrna: Paradise is Burning, The Asa K. Jennings Story'', a 2022 documentary produced by Mike Damergis; won the Best Historical Film award in the Cannes World Film Festival (May 2022).

See also

*Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917

250px, The fire as seen from the quay in 1917.

250px, The fire as seen from the Thermaic Gulf.

The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 ( el, Μεγάλη Πυρκαγιά της Θεσσαλονίκης, 1917) destroyed two thirds of the city of T ...

* Fire of Manisa

The Fire of Manisa ( tr, Manisa yangını) refers to the burning of the town of Manisa, Turkey, which started on the night of Tuesday, 5 September 1922 and continued until 8 September. It was started and organized by the retreating Hellenic Army ...

* Scorched Earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

Notes

Further reading

Personal Accounts

* Der-Sarkissian, Jack.Two Armenian Physicians in Smyrna: Case Studies in Survival

" in ''Armenian Smyrna/Izmir: The Aegean Communities,'' ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2012. * Calonne, David Stephen. "Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, and Smyrna 1922," in ''Armenian Smyrna/Izmir: The Aegean Communities''.

History of Smyrna and the Fire

*Dobkin, Marjorie Housepian. ''Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of a City''. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971; 2nd ed. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1988. * Georgelin, Hervé. ''La Fin de Smyrne: Du cosmopolitisme aux nationalismes''. Paris: CNRS Editions, 2005. * Karagianis, Lydia, ''Smoldering Smyrna,'' Carlton Press, 1996; . * Llewellyn Smith, Michael. ''Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919–1922''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973. * Mansel, Philip. ''Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean'', London, John Murray, 2010; New Haven, Yale University Press, 2011. * Milton, Giles. ''Paradise Lost: Smyrna, 1922''. New York: Basic Books, 2008.Humanitarianism

* Papoutsy, Christos. ''Ships of Mercy: The True Story of the Rescue of the Greeks, Smyrna, September 1922''. Portsmouth, N.H.: Peter E. Randall, 2008. * Tusan, Michelle. ''Smyrna's Ashes: Humanitarianism, Genocide, and the Birth of the Middle East''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. * Ureneck, Lou. ''The Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First Genocide''. New York: Ecco Press, 2015.Memory and Remembering

* Kolluoğlu-Kırlı, Biray. "The Play of Memory, Counter-Memory: Building Izmir on Smyrna’s Ashes," ''New Perspectives on Turkey'' 26 (2002): 1–28. * Morack, Ellinor. "Fear and Loathing in 'Gavur' Izmir: Emotions in Early Republican Memories of the Greek Occupation (1919–22)," '' International Journal of Middle East Studies'' 49 (2017): 71–89. * Neyzi, Leyla. "Remembering Smyrna/Izmir: Shared History, Shared Trauma," ''History and Memory'' 20 (2008):106–27.External links

Association of Smyrneans

Remembering Smyrna/Izmir: Shared History, Shared Trauma

Levantine Heritage

''Smyrna 1922''

a rare film, on Vimeo – shows before and after the fire {{DEFAULTSORT:Great Fire Of Smyrna Occupation of Smyrna Fires in Turkey Greek genocide Aftermath of the Armenian genocide 1922 fires in Europe 1922 in the Ottoman Empire 20th-century controversies Mass murder in 1922 September 1922 events Massacres in Turkey Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) Urban fires in Asia 1920s murders in Turkey 1922 crimes in the Ottoman Empire Events in İzmir 1922 disasters in the Ottoman Empire