Desmond Rebellion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569–1573 and 1579–1583 in the Irish province of

They were rebellions by the

They were rebellions by the

/ref> in defiance of English law.

Gerald, the Earl of Desmond, initially resisted the call of the rebels and tried to remain neutral but gave in once the authorities had proclaimed him a

Gerald, the Earl of Desmond, initially resisted the call of the rebels and tried to remain neutral but gave in once the authorities had proclaimed him a

Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

.

They were rebellions by the

They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond

Earl of Desmond is a title in the peerage of Ireland () created four times. When the powerful Earl of Desmond took arms against Queen Elizabeth Tudor, around 1578, along with the King of Spain and the Pope, he was confiscated from his estates, s ...

, the head of the Fitzmaurice/FitzGerald Dynasty in Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

, and his followers, the Geraldines

The FitzGerald/FitzMaurice Dynasty is a noble and aristocratic dynasty of Cambro-Norman, Anglo-Norman and later Hiberno-Norman origin. They have been peers of Ireland since at least the 13th century, and are described in the Annals of the ...

and their allies, against the threat of the extension of the English government over the province. The rebellions were motivated primarily by the desire to maintain the independence of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

lords from their monarch but also had an element of religious antagonism between Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Geraldines and the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

English state. They culminated in the destruction of the Desmond dynasty and the plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

or colonisation

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

of Munster with English Protestant settlers. 'Desmond' is the Anglicisation

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

of the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

''Deasmumhain'', meaning 'South Munster'

In addition to the Scorched Earth policy, it might be worth mentioning that, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Warham St Leger, Perrot and later Nicholas Malby and Lord Grey and William Pelham, deliberately targeted civilians. Woman and children, the elderly or infirm or even those of diminished mental capacity. This was done regardless of whether they were pro the Desmonds or not. It was considered a good policy to terrorise the native population. The American author Richard Berleth covers it in great detail in his book the twilight Lords.

Causes

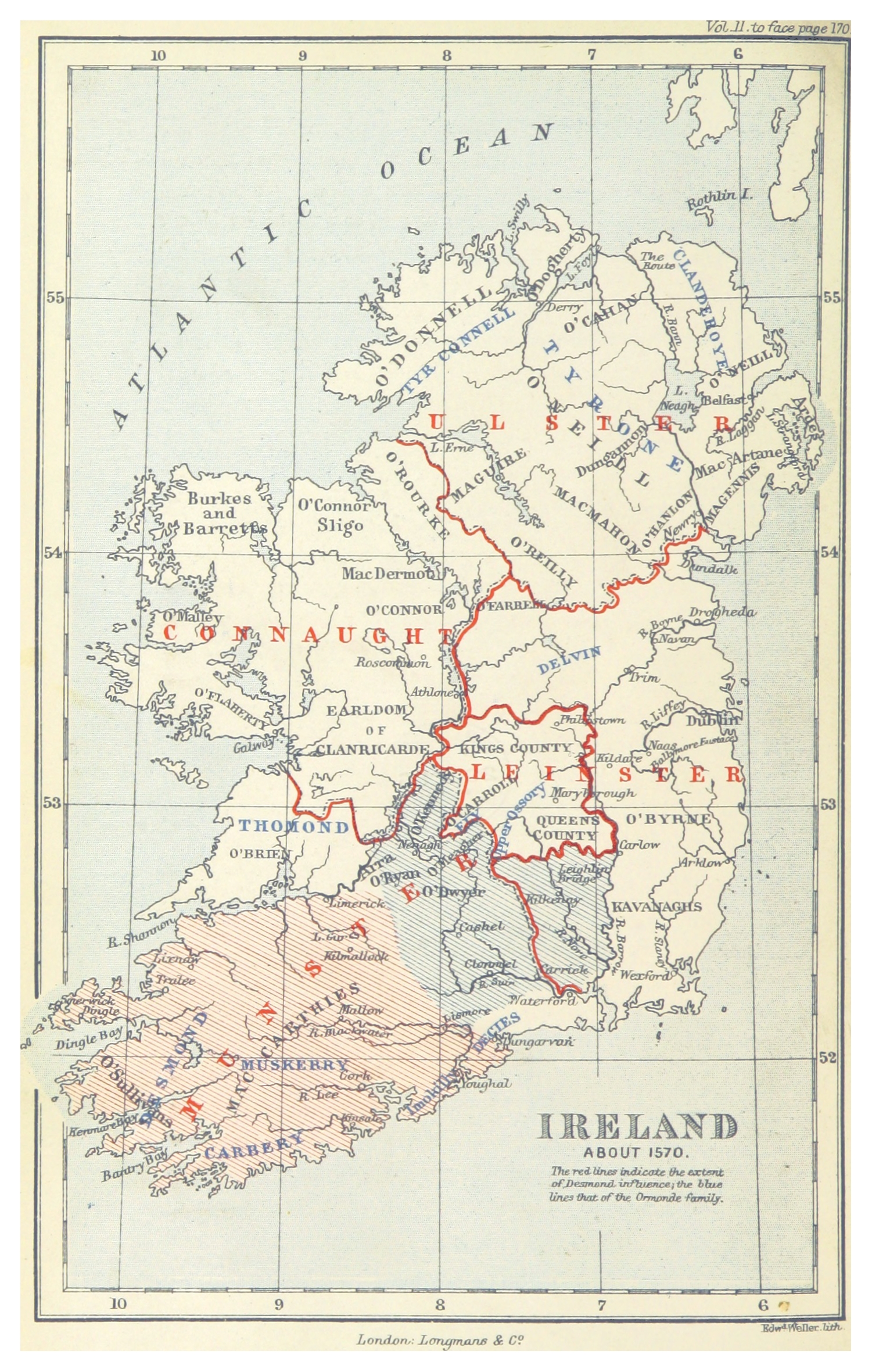

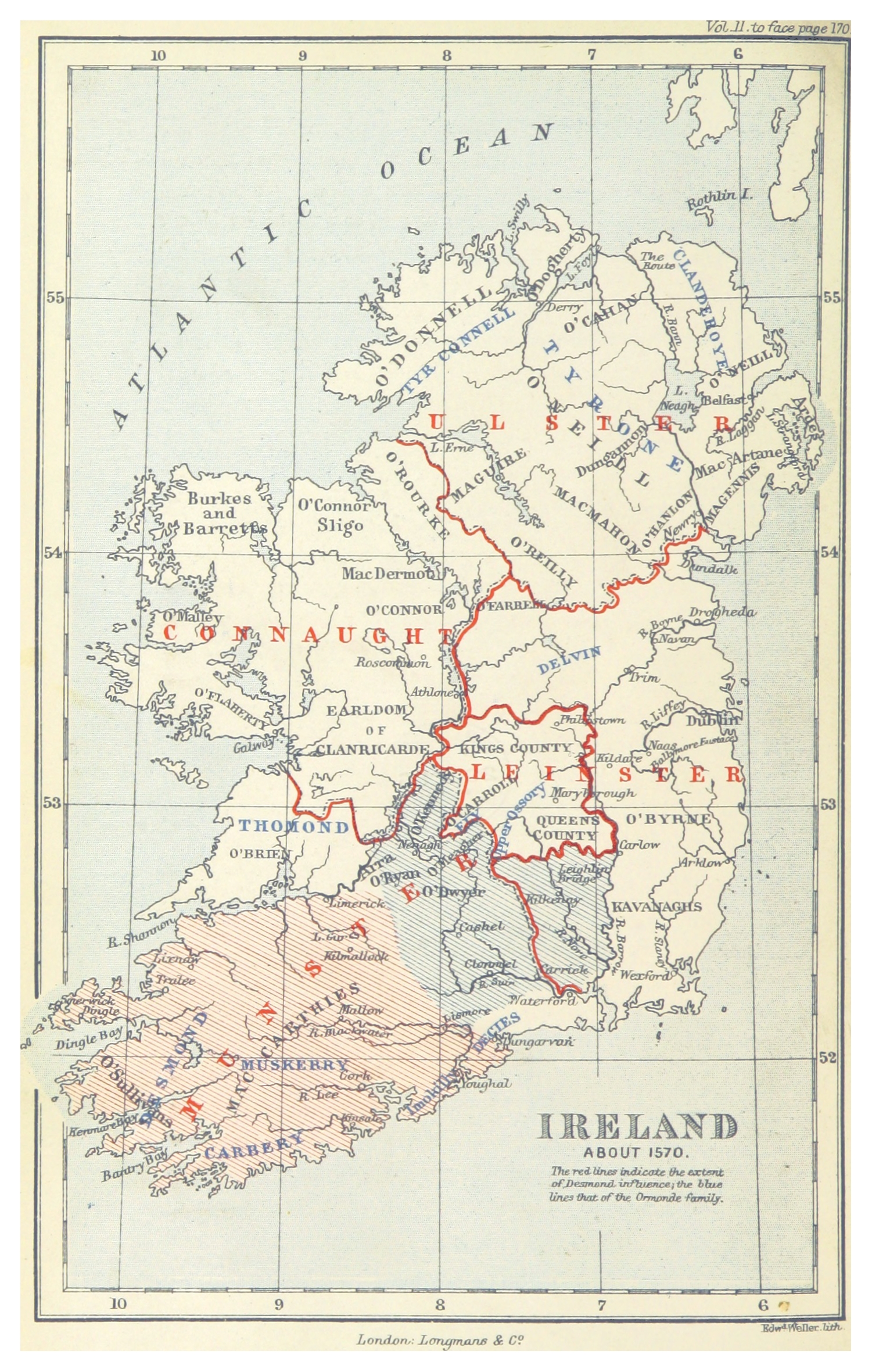

The south of Ireland (the provinces ofMunster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

and southern Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of Ir ...

) was dominated, as it had been for over two centuries, by the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

Butlers of Ormonde Ormonde is a surname occurring in Portugal (mainly Azores), Brazil, England, and United States. It may refer to:

People

* Ann Ormonde (born 1935), an Irish politician

* James Ormond or Ormonde (c. 1418–1497), the illegitimate son of John Butl ...

and the Fitzmaurices and FitzGeralds of Desmond. Both families raised their own armed forces and imposed their own law, a mixture of Irish and English customs independent of the English government imposed on Ireland. Beginning in the 1530s, successive English administrations tried to expand English control over Ireland (See Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, He ...

). By the 1560s, their attention had turned to the south of Ireland and Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586), Lord Deputy of Ireland, was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst, a prominent politician and courtier during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, from both of whom he received ...

, as Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive (government), executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland ...

, was charged with establishing the authority of the English government over the independent lordships there. His solution was the formation of "lord presidencies", provincial military governors who would replace the local lords as military powers and keepers of the peace.

The dynasties saw the presidencies as intrusions into their sphere of influence. Their interfamilial competition had seen the Butlers and FitzGeralds fight a pitched battle against each other at Affane

Affane () is a small village in west County Waterford, Ireland, situated near Cappoquin and the River Blackwater.

History

References to the town of Affane are limited to its inclusion on a list dated 1300 and an incident in 1312, but the pre ...

in County Waterford

County Waterford ( ga, Contae Phort Láirge) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is part of the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region. It is named ...

in 1565Hull, Eleanor. "The Desmond Rebellion", ''A History of Ireland'', 1931/ref> in defiance of English law.

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

summoned the heads of both houses to London to explain their actions. However, the treatment of the dynasties was not even-handed. Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormonde

Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormond and 3rd Earl of Ossory PC (Ire) (; – 1614), was an influential courtier in London at the court of Elizabeth I. He was Lord Treasurer of Ireland from 1559 to his death. He fought for the crown in the ...

— "Black Tom" Butler, Queen Elizabeth's cousin and friend – was pardoned, while both Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Desmond (in 1567) and his brother, John of Desmond, widely regarded as the real military leader of the FitzGeralds, (in 1568) were arrested and detained in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

on Ormonde's urging.

This decapitated the natural leadership of the Munster Geraldines and left the Desmond earldom in the hands of a soldier, James FitzMaurice

James Michael Christopher Fitzmaurice DFC (6 January 1898 – 26 September 1965) was an Irish aviation pioneer. He was a member of the crew of the ''Bremen'', which made the first successful trans-Atlantic aircraft flight from East to West ...

, the captain general of the Desmond military. FitzMaurice had little stake in a new demilitarised order in Munster, with abolition of the Irish lords' armies. A factor that drew wider support for FitzMaurice was the prospect of land confiscations, which had been mooted by Sidney and Peter Carew

Sir Peter Carew (1514? – 27 November 1575) of Mohuns Ottery, Luppitt, Devon, was an English adventurer, who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and took part in the Tudor conquest of Ireland. His biography was written by h ...

, an English claimant to lands granted to an ancestor just after the Norman conquest of Ireland

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land from the Irish, over which the kings of England then claimed sovereignty, all allegedly sanc ...

that had been lost soon afterwards.

This ensured FitzMaurice the support of important Munster clans, notably MacCarthy Mór, O'Sullivan Beare and O'Keefe, and two prominent Butlers, brothers of the Earl. Fitzmaurice himself had lost the land he had held at Kerricurrihy in County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

, which had been taken and leased to English colonists. He was a devout Catholic, influenced by the counter-reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

, and saw the Protestant Elizabethan governors as his enemies.

To discourage Sidney from going ahead with the Lord Presidency for Munster and to re-establish Desmond primacy over the Butlers, FitzMaurice planned rebellion against the English presence in the south, and against the Earl of Ormonde. FitzMaurice had wider aims than simply the recovery of FitzGerald supremacy within the context of the English Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label=Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

. Before the rebellion, he had secretly sent Maurice MacGibbon, Catholic Archbishop of Cashel

The Archbishop of Cashel ( ga, Ard-Easpag Chaiseal Mumhan) was an archiepiscopal title which took its name after the town of Cashel, County Tipperary in Ireland. Following the Reformation, there had been parallel apostolic successions to the title ...

, to seek military aid from Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

.

First Desmond Rebellion

FitzMaurice first attacked the English colony at Kerrycurihy south ofCork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

city in June 1569, before attacking Cork itself and those native lords who refused to join the rebellion. FitzMaurice's force of 4,500 men went on to besiege Kilkenny

Kilkenny (). is a city in County Kilkenny, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region and in the province of Leinster. It is built on both banks of the River Nore. The 2016 census gave the total population of Kilkenny as 26,512.

Kilken ...

, seat of the Earls of Ormonde, in July. In response, Sidney mobilised 600 English troops, who marched south from Dublin and another 400 landed by sea in Cork. Thomas Butler, Earl of Ormonde, returned from London, where he had been at court, and mobilised the Butlers and some Gaelic Irish clans antagonistic to the Geraldines. After the failed attempt to take Kilkenny, the rebellion quickly descended into an untidy mopping-up operation.

Together, Ormonde, Sidney, and Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an English adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America ...

, appointed as governor of Munster, devastated the lands of FitzMaurice's allies in a scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

policy. FitzMaurice's forces broke up, as individual lords had to retire to defend their own territories. Gilbert, a half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

, was the most notorious for terror tactics, killing civilians at random and setting up corridors of severed heads at the entrance to his camps.

Sidney forced FitzMaurice into the mountains of Kerry

Kerry or Kerri may refer to:

* Kerry (name), a given name and surname of Gaelic origin (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Kerry, Queensland, Australia

* County Kerry, Ireland

** Kerry Airport, an international airport in County ...

, from where he launched guerrilla attacks on the English and their allies. By 1570, most of FitzMaurice's allies had submitted to Sidney. The most important, Donal MacCarthy Mór, surrendered in November 1569. Nevertheless, the guerrilla campaign continued for three more years. In February 1571, John Perrot

Sir John Perrot (7 November 1528 – 3 November 1592) served as lord deputy to Queen Elizabeth I of England during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was formerly speculated that he was an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, though the idea is reject ...

was made Lord President of Munster

The post of Lord President of Munster was the most important office in the English government of the Irish province of Munster from its introduction in the Elizabethan era for a century, to 1672, a period including the Desmond Rebellions in Munste ...

. He pursued FitzMaurice with 700 troops for over a year without success. FitzMaurice had some victories, capturing an English ship near Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

and burning the town of Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle (or King John's Castle). The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are sti ...

in 1571, but by early 1573 his force was reduced to less than 100 men. FitzMaurice finally submitted on 23 February 1573, having negotiated a pardon for his life. However, in 1574, he became landless, and in 1575 he sailed to France to seek help from the Catholic powers to start another rebellion.

Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond, and his brother, John, were released from prison to reconstruct their shattered territory. Under a settlement imposed after the rebellion, known as "composition", the Desmonds' military forces were limited by law to just 20 horsemen; their tenants were made to pay rent to them rather than supply military service or quarter their soldiers. Perhaps the biggest winner of the first Desmond Rebellion was the Earl of Ormonde, who established himself as the most powerful lord in the south of Ireland due to siding with the English crown.

All of the local chiefs had submitted by the end of the rebellion. The methods used to suppress it provoked lingering resentment, especially among the Irish mercenaries; ''gall óglaigh'' or ''gallowglass

The Gallowglass (also spelled galloglass, gallowglas or galloglas; from ga, gallóglaigh meaning foreign warriors) were a class of elite mercenary warriors who were principally members of the Norse-Gaelic clans of Ireland between the mid 13t ...

'' as the English termed them, who had rallied to FitzMaurice. William Drury, Lord President of Munster from 1576, executed around 700 of these men in the years after the rebellion.

In the aftermath of the uprising, Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

customs such as Brehon Laws

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of Freemen), also called Brehon law, comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norma ...

, Irish dress, bardic poetry, and the maintaining of "private armies" – things that were deeply valued in traditional Irish society - were again outlawed and suppressed. FitzMaurice had emphasised the Gaelic character of the rebellion, wearing Irish dress, speaking only Irish, and referring to himself as the ''taoiseach'' of the Geraldines. Irish landowners continued to be threatened by the arrival of English colonists to settle on land confiscated from the Irish. All of these factors meant that, when FitzMaurice returned from Europe to start a new rebellion, plenty of people in Munster were willing to join him.

In late 1569 the Catholic Northern Rebellion

The Rising of the North of 1569, also called the Revolt of the Northern Earls or Northern Rebellion, was an unsuccessful attempt by Catholic nobles from Northern England to depose Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of ...

broke out in England, but was crushed. This and the Desmond Rebellion caused Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

to issue ''Regnans in Excelsis

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime", declared h ...

'', a bull excommunicating Elizabeth and depriving her of the allegiance of her Catholic subjects. Elizabeth had previously accepted Catholic worship in private, but now suppressed militant Catholicism. Luckily for her, most of her Irish subjects did not want to get involved in rebellions, while also mostly remaining Catholic.

Second Desmond Rebellion

The second Desmond rebellion was sparked whenJames FitzMaurice

James Michael Christopher Fitzmaurice DFC (6 January 1898 – 26 September 1965) was an Irish aviation pioneer. He was a member of the crew of the ''Bremen'', which made the first successful trans-Atlantic aircraft flight from East to West ...

launched an invasion of Munster in 1579. During his exile in Europe he had declared himself as a soldier of the counter-reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

, arguing that since the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

's excommunication of Elizabeth I Irish Catholics did not owe loyalty to a heretic monarch. The Pope granted FitzMaurice an indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The '' Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

and supplied him with troops and money. FitzMaurice landed at Smerwick

Ard na Caithne (; meaning "height of the arbutus/ strawberry tree"), sometimes known in English as Smerwick, is a bay and townland in County Kerry in Ireland. One of the principal bays of Corca Dhuibhne, it is located at the foot of an Triúr ...

, near Dingle

Dingle (Irish language, Irish: ''An Daingean'' or ''Daingean Uí Chúis'', meaning "fort of Ó Cúis") is a town in County Kerry, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The only town on the Dingle Peninsula, it sits on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coas ...

(modern County Kerry

County Kerry ( gle, Contae Chiarraí) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the South-West Region and forms part of the province of Munster. It is named after the Ciarraige who lived in part of the present county. The population of the co ...

) on 18 July 1579 with a small force of Spanish and Italian troops. He was joined on 1 August by John of Desmond, a brother of the earl, who had a large following among his kinsmen and the disaffected swordsmen of Munster. Other Gaelic clans and Old English families also joined in the rebellion.

FitzMaurice was killed in a skirmish with the Clanwilliam Burkes on 18 August, and John FitzGerald assumed leadership of the rebellion.

Gerald, the Earl of Desmond, initially resisted the call of the rebels and tried to remain neutral but gave in once the authorities had proclaimed him a

Gerald, the Earl of Desmond, initially resisted the call of the rebels and tried to remain neutral but gave in once the authorities had proclaimed him a traitor

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. He joined the rebellion by sacking Youghal (on 13 November) and Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

, and devastated the country of the English and their allies.

In the summer of 1580 English troops under William Pelham and locally raised Irish forces under the Earl of Ormonde retook the south coast, destroyed the lands of the Desmonds and their allies, and killed their tenants. They captured Carrigafoyle, the principal Desmond castle at the mouth of the Shannon at Easter 1580, cutting off the Geraldine forces from the rest of the country and prevented a landing of foreign troops into the main Munster ports.

In July 1580 the rising spread to Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of Ir ...

, under the leadership of Fiach MacHugh O'Byrne

Fiach Mac Aodha Ó Broin (anglicised as Feagh or Fiach MacHugh O'Byrne) (1534 – 8 May, 1597) was Chief of the Name of Clann Uí Bhroin (Clan O'Byrne) and Lord of Ranelagh during the Elizabethan wars against the Irish clans.

Arms

Backg ...

and his client the Pale

The Pale (Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast st ...

lord James Eustace, 3rd Viscount Baltinglass

James FitzEustace of Harristown, 3rd Viscount Baltinglass

(1530–1585)

James FitzEustace, the eldest son of Rowland Eustace, 2nd Viscount Baltinglass and Joan, daughter of James Butler, 8th Baron Dunboyne. He was born in 1530 and died in Spain in ...

. They ambushed and massacred a large English force under the Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive (government), executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland ...

Lord Grey de Wilton at the battle of Glenmalure

The Battle of Glenmalure ( ga, Cath Ghleann Molúra) took place in Ireland on 25 August 1580 during the Desmond Rebellions. A Catholic army of united Irish clans from the Wicklow Mountains led by Fiach MacHugh O'Byrne and James Eustace, 3rd Vis ...

on 25 August.

On 10 September 1580, 600 papal troops landed at Smerwick in Kerry to support the rebellion. They were besieged in a fort at Dún an Óir

Ard na Caithne (; meaning "height of the arbutus/ strawberry tree"), sometimes known in English as Smerwick, is a bay and townland in County Kerry in Ireland. One of the principal bays of Corca Dhuibhne, it is located at the foot of an Triúr D ...

. They surrendered after two days of bombardment and were then massacred. Through the relentless scorched-earth tactics of the English, who killed animals and razed crops and homes to deprive the Irish of any food or shelter, the rebellion was crushed by mid-1581. By May 1581, most of the minor rebels and FitzGerald allies in Munster and Leinster had accepted Elizabeth I's offer of a general pardon. John of Desmond was killed north of Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

in early 1582.

The Geraldine earl was pursued by English forces until the end. From 1581 to 1583, his supporters evaded capture in the mountains of Kerry

Kerry or Kerri may refer to:

* Kerry (name), a given name and surname of Gaelic origin (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Kerry, Queensland, Australia

* County Kerry, Ireland

** Kerry Airport, an international airport in County ...

. On 2 November 1583 the earl was hunted down and killed near Tralee

Tralee ( ; ga, Trá Lí, ; formerly , meaning 'strand of the Lee River') is the county town of County Kerry in the south-west of Ireland. The town is on the northern side of the neck of the Dingle Peninsula, and is the largest town in County ...

in Kerry by the O'Moriarty family. The clan chief, Maurice, received 1,000 pounds of silver and a pension of 20 pounds a year from the English government for Desmond's head, which was sent to Queen Elizabeth. Desmond's body was displayed on the walls of Cork. (Maurice O'Moriarty ended his life by being hanged at Tyburn.)

Aftermath

After three years of scorched earth warfare by the English, Munster was racked byfamine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

. In April 1582, the provost marshal of Munster, Sir Warham St Leger

Sir Warham St Leger PC (Ire) ( – 1597) was an English soldier, administrator, and politician, who sat in the Irish House of Commons in the Parliament of 1585–1586.

Birth and origins

Warham was probably born in 1525 in England, the second so ...

, estimated that 30,000 people had died of hunger in the previous six months. Plague broke out in Cork city

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city' ...

, to where the country people had fled to avoid the fighting. People continued to die of starvation and plague long after the war had ended, and it is estimated that by 1589 one-third of the province's population had died. Grey was recalled by Elizabeth I for his excessive brutality. Two famous accounts tell us of the devastation of Munster after the Desmond rebellion. The first is from the Gaelic Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

:

The second is from the View of the Present State of Ireland, written by English poet Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

, who fought in the campaign, approved the scorched earth method, and suggested it as a useful method of enforcing English ways:

The wars of the 1570s and 1580s marked a watershed in Ireland. The southern Geraldine axis of power was annihilated, and Munster was "planted" with English colonists given land confiscated from those who fought for their country. After a survey begun in 1584 by Sir Valentine Browne

Sir Valentine Browne (died 1589), of Croft, Lincolnshire, was auditor, treasurer and victualler of Berwick-upon-Tweed. He acquired large estates in Ireland during the Plantation of Munster, in particular the seignory of Molahiffe. He lived at R ...

, Surveyor General

A surveyor general is an official responsible for government surveying in a specific country or territory. Historically, this would often have been a military appointment, but it is now more likely to be a civilian post.

The following surveyor ge ...

of Ireland, the thousands of English soldiers and administrators who had been imported to suppress the rebellion were given land in the Munster Plantation

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, angl ...

of Desmond's confiscated estates. The Elizabethan conquest of Ireland followed the subsequent Nine Years War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

and the extension of plantation policy to other parts of the country.

See also

*List of Irish rebellions

This is a list of uprisings by Irish people against English and British claims of sovereignty over Ireland. These uprisings include attempted counter-revolutions and rebellions, though some can be described as either, depending upon perspective. ...

*Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, He ...

*Early Modern Ireland 1536-1691

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* E ...

Notes

References

*Colm Lennon, ''Sixteenth Century Ireland – The Incomplete Conquest'', Dublin 1994. *Edward O'Mahony, ''Baltimore, the O'Driscolls, and the end of Gaelic civilisation, 1538–1615'', Mizen Journal, no. 8 (2000): 110–127. *Nicholas Canny, ''The Elizabethan Conquest of Ireland'', Harvester Press Ltd, Sussex 1976. *Nicholas Canny, ''Making Ireland British 1580–1650'', Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. {{Ireland topics , expanded=History 16th century in Ireland 16th-century military history of the Kingdom of England 16th-century rebellions Rebellions in Ireland Tudor rebellions Wars involving Ireland FitzGerald dynasty Catholic rebellions