Democratic World Government on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

A world government with executive, legislative, and judicial functions and an administrative apparatus has never existed.

The inception of the United Nations (UN) in the mid-20th century remains the closest approximation to a world government, as it is by far the largest and most powerful international institution. However, the UN is mostly limited to an advisory role, with the stated purpose of fostering cooperation between existing

The Dutch philosopher and jurist Hugo Grotius, widely regarded as a founder of international law, believed in the eventual formation of a world government to enforce it. His book, '' De jure belli ac pacis'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), published in Paris in 1625, is still cited as a foundational work in the field. Though he does not advocate for world government ''per se,'' Grotius argues that a "common law among nations", consisting of a framework of principles of natural law, bind all people and societies regardless of local custom.

The Dutch philosopher and jurist Hugo Grotius, widely regarded as a founder of international law, believed in the eventual formation of a world government to enforce it. His book, '' De jure belli ac pacis'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), published in Paris in 1625, is still cited as a foundational work in the field. Though he does not advocate for world government ''per se,'' Grotius argues that a "common law among nations", consisting of a framework of principles of natural law, bind all people and societies regardless of local custom.

In his essay " Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch" (1795), Kant describes three basic requirements for organizing human affairs to permanently abolish the threat of present and future war, and, thereby, help establish a new era of lasting peace throughout the world. Kant described his proposed peace program as containing two steps.

The "Preliminary Articles" described the steps that should be taken immediately, or with all deliberate speed:

# "No Secret Treaty of Peace Shall Be Held Valid in Which There Is Tacitly Reserved Matter for a Future War"

# "No Independent States, Large or Small, Shall Come under the Dominion of Another State by Inheritance, Exchange, Purchase, or Donation"

# "

In his essay " Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch" (1795), Kant describes three basic requirements for organizing human affairs to permanently abolish the threat of present and future war, and, thereby, help establish a new era of lasting peace throughout the world. Kant described his proposed peace program as containing two steps.

The "Preliminary Articles" described the steps that should be taken immediately, or with all deliberate speed:

# "No Secret Treaty of Peace Shall Be Held Valid in Which There Is Tacitly Reserved Matter for a Future War"

# "No Independent States, Large or Small, Shall Come under the Dominion of Another State by Inheritance, Exchange, Purchase, or Donation"

# "

p. 36

In its move to overthrow the post- World War I Treaty of Versailles, Germany had already withdrawn itself from the League of Nations, and it did not intend to join a similar internationalist organization ever again. In his stated political aim of expanding the living space ('' Lebensraum'') of the Germanic people by destroying or driving out "lesser-deserving races" in and from other territories, dictator Adolf Hitler devised an ideological system of self-perpetuating The

The

World War II (1939–1945) resulted in an unprecedented scale of destruction of lives (over 60 million dead, most of them civilians), and the use of weapons of mass destruction. Some of the acts committed against civilians during the war were on such a massive scale of savagery, they came to be widely considered as

World War II (1939–1945) resulted in an unprecedented scale of destruction of lives (over 60 million dead, most of them civilians), and the use of weapons of mass destruction. Some of the acts committed against civilians during the war were on such a massive scale of savagery, they came to be widely considered as  A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) is a proposed addition to the United Nations System that would allow for participation of member nations' legislators and, eventually,

A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) is a proposed addition to the United Nations System that would allow for participation of member nations' legislators and, eventually,

, there is no functioning global international military, executive, legislature, judiciary, or constitution with jurisdiction over the entire planet.

The world is divided geographically and demographically into mutually exclusive territories and political structures called states which are independent and

, there is no functioning global international military, executive, legislature, judiciary, or constitution with jurisdiction over the entire planet.

The world is divided geographically and demographically into mutually exclusive territories and political structures called states which are independent and UN.org

, Chart Of particular interest politically are the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization.

Militarily, the UN deploys peacekeeping forces, usually to build and maintain post-conflict peace and stability. When a more aggressive international military action is undertaken, either '' ad hoc'' coalitions (for example, the Multi-National Force – Iraq) or regional military alliances (for example, NATO) are used. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) formed together in July 1944 at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, to foster global monetary cooperation and to fight poverty by financially assisting states in need. These institutions have been criticized as simply oligarchic hegemonies of the Great Powers, most notably the United States, which maintains the only veto, for instance, in the International Monetary Fund. The World Trade Organization (WTO) sets the rules of international trade. It has a semi-legislative body (the General Council, reaching decisions by consensus) and a judicial body (the Dispute Settlement Body). Another influential economical international organization is the

"Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch"

(English translation of "''Zum ewigen Frieden''")

World Government Movement

{{DEFAULTSORT:World Government Government Government

national government A national government is the government of a nation.

National government or

National Government may also refer to:

* Central government in a unitary state, or a country that does not give significant power to regional divisions

* Federal governme ...

s, rather than exerting authority over them. Nevertheless, the organization is commonly viewed as either a model for, or preliminary step towards, a global government.

The concept of universal governance has existed since antiquity and been the subject of discussion, debate, and even advocacy by some kings, philosophers, religious leaders, and secular humanists. Some of these have discussed it as a natural and inevitable outcome of human social evolution, and interest in it has coincided with the trends of globalization. Opponents of world government, who come from a broad political spectrum, view the concept as a tool for violent totalitarianism, unfeasible, or simply unnecessary, and in the case of some sectors of fundamentalist Christianity, as a vehicle for the Antichrist to bring about the end-times.

World government for Earth is frequently featured in fiction, particularly within the science fiction genre

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to science fiction:

Science fiction – a genre of fiction dealing with the impact of imagined innovations in science or technology, often in a futuristic setting. Explo ...

; well-known examples include the "World State" in Aldous Huxley's '' Brave New World,'' the "Dictatorship of the Air" in H. G. Wells' '' The Shape of Things to Come,'' the United Nations in James S. A Corey's ''The Expanse

Expanse or The Expanse may refer to:

Media and entertainment

''The Expanse'' franchise

* ''The Expanse'' (novel series), a series of science fiction novels by James S. A. Corey

* ''The Expanse'' (TV series), a television adaptation of the ...

'', and United Earth (amongst other planetary sovereignties and even larger polities) in the Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the eponymous 1960s television series and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has expanded into vari ...

franchise. This concept also applies to other genres, while not as commonly, including well known examples such as One Piece, or to a degree, Nineteen Eighty Four

''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (also stylised as ''1984'') is a dystopian social science fiction novel and cautionary tale written by the English writer George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and fina ...

.

Definition

Wendt defines a state as an "organization possessing a monopoly on the legitimate use of organized violence within a society." According to Wendt, a world state would need to fulfill the following requirements: # Monopoly on organized violence - states have exclusive use of legitimate force within their territory. #Legitimacy

Legitimacy, from the Latin ''legitimare'' meaning "to make lawful", may refer to:

* Legitimacy (criminal law)

* Legitimacy (family law)

* Legitimacy (political)

See also

* Bastard (law of England and Wales)

* Illegitimacy in fiction

* Legit (d ...

- perceived as right by their populations, and possibly the global community.

# Sovereignty - possessing common power and legitimacy.

# Corporate action - a collection of individuals who act together in a systematic way.

A world government would not require a centrally controlled army or a central decision-making body, as long as the four conditions are fulfilled. In order to develop a world state, three changes must occur in the world system:

# Universal security community - a peaceful system of binding dispute resolution without threat of interstate violence.

# Universal collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats t ...

- unified response to crimes and threats.

# Supranational authority - binding decisions are made that apply to each and every state.

The development of a world government is conceptualized as a process through five stages:

# System of states;

# Society of states;

# World society;

# Collective security;

# World state.

Wendt argues that a struggle among sovereign individuals results in the formation of a collective identity and eventually a state. The same forces are present within the international system and could possibly, and potentially inevitably lead to the development of a world state through this five-stage process. When the world state would emerge, the traditional expression of states would become localized expressions of the world state. This process occurs within the default state of anarchy present in the world system.

Immanuel Kant conceptualized the state as sovereign individuals formed out of conflict. Part of the traditional philosophical objections to a world state (Kant, Hegel) are overcome by modern technological innovations. Wendt argues that new methods of communication and coordination can overcome these challenges.

Pre-industrialized philosophy

Antiquity

World government was an aspiration of ancient rulers as early as the Bronze Age (3300 BCE to 1200); Ancient Egyptian kings aimed to rule "All That the Sun Encircles",Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

kings "All from the Sunrise to the Sunset", and ancient Chinese and Japanese emperors "All under Heaven".

The Chinese had a particularly well-developed notion of world government in the form of Great Unity, or ''Da Yitong'' (大同), a Utopian vision for a united and just society bound by moral virtue and principles of good governance. The Han dynasty, which successfully united much of China for over four centuries, evidently aspired to this vision by erecting an Altar of the Great Unity in 113 BC.

Contemporaneously, the Ancient Greek historian Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

described Roman rule over much of the known world at the time as a "marvelous" achievement worthy of consideration by future historians. The '' Pax Romana'', a roughly two-century period of stable Roman hegemony across three continents, reflected the positive aspirations of a world government, as it was deemed to have brought prosperity and security to what was once a politically and culturally fractious region. Marxism-Leninism would later envision a world revolution leading to world communism.

Dante's Universal Monarchy

The idea of world government outlived thefall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

for centuries, particularly in its former heartland of Italy. In his fourteenth century work ''De Monarchia

''Monarchia'', often called ''De Monarchia'' (, ; "(On) Monarchy"), is a Latin treatise on secular and religious power by Dante Alighieri, who wrote it between 1312 and 1313. With this text, the poet intervened in one of the most controversial s ...

'', Florentine poet and philosopher Dante Alighieri, considered by many to be a proto-protestant, appealed for a universal monarchy that would work separate from and uninfluenced by the Roman Catholic Church to establish peace in humanity's lifetime and the afterlife, respectively:

But what has been the condition of the world since that day the seamless robeDi Gattinara was an Italian diplomat who widely promoted Dante's ''f Pax Romana F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''. Hist ...first suffered mutilation by the claws of avarice, we can read—would that we could not also see! O human race! what tempests must need toss thee, what treasure be thrown into the sea, what shipwrecks must be endured, so long as thou, like a beast of many heads, strivest after diverse ends! Thou art sick in either intellect, and sick likewise in thy affection. Thou healest not thy high understanding by argument irrefutable, nor thy lower by the countenance of experience. Nor dost thou heal thy affection by the sweetness of divine persuasion, when the voice of theHoly Spirit In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...breathes upon thee, 'Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!'

De Monarchia

''Monarchia'', often called ''De Monarchia'' (, ; "(On) Monarchy"), is a Latin treatise on secular and religious power by Dante Alighieri, who wrote it between 1312 and 1313. With this text, the poet intervened in one of the most controversial s ...

'' and its call for a universal monarchy. An advisor of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, and the chancellor of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (Crown of Castile, Castil ...

, he conceived global government as uniting all Christian nations

A Christian state is a country that recognizes a form of Christianity as its official religion and often has a state church (also called an established church), which is a Christian denomination that supports the government and is supported by ...

under a Respublica Christiana

In medieval and early modern Western political thought, the ''respublica'' or ''res publica Christiana'' refers to the international community of Christian peoples and states. As a Latin phrase, ''res publica Christiana'' combines Christianity wit ...

, which was the only political entity able to establish world peace.

Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546)

The Spanish philosopher Francisco de Vitoria is considered an author of "global political philosophy" and international law, along with Alberico Gentili andHugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

. This came at a time when the University of Salamanca was engaged in unprecedented thought concerning human rights, international law, and early economics based on the experiences of the Spanish Empire. De Vitoria conceived of the ''res publica totius orbis'', or the "republic of the whole world".

Hugo Grotius (1583–1645)

The Dutch philosopher and jurist Hugo Grotius, widely regarded as a founder of international law, believed in the eventual formation of a world government to enforce it. His book, '' De jure belli ac pacis'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), published in Paris in 1625, is still cited as a foundational work in the field. Though he does not advocate for world government ''per se,'' Grotius argues that a "common law among nations", consisting of a framework of principles of natural law, bind all people and societies regardless of local custom.

The Dutch philosopher and jurist Hugo Grotius, widely regarded as a founder of international law, believed in the eventual formation of a world government to enforce it. His book, '' De jure belli ac pacis'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), published in Paris in 1625, is still cited as a foundational work in the field. Though he does not advocate for world government ''per se,'' Grotius argues that a "common law among nations", consisting of a framework of principles of natural law, bind all people and societies regardless of local custom.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

In his essay " Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch" (1795), Kant describes three basic requirements for organizing human affairs to permanently abolish the threat of present and future war, and, thereby, help establish a new era of lasting peace throughout the world. Kant described his proposed peace program as containing two steps.

The "Preliminary Articles" described the steps that should be taken immediately, or with all deliberate speed:

# "No Secret Treaty of Peace Shall Be Held Valid in Which There Is Tacitly Reserved Matter for a Future War"

# "No Independent States, Large or Small, Shall Come under the Dominion of Another State by Inheritance, Exchange, Purchase, or Donation"

# "

In his essay " Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch" (1795), Kant describes three basic requirements for organizing human affairs to permanently abolish the threat of present and future war, and, thereby, help establish a new era of lasting peace throughout the world. Kant described his proposed peace program as containing two steps.

The "Preliminary Articles" described the steps that should be taken immediately, or with all deliberate speed:

# "No Secret Treaty of Peace Shall Be Held Valid in Which There Is Tacitly Reserved Matter for a Future War"

# "No Independent States, Large or Small, Shall Come under the Dominion of Another State by Inheritance, Exchange, Purchase, or Donation"

# "Standing Armies

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or na ...

Shall in Time Be Totally Abolished"

# " National Debts Shall Not Be Contracted with a View to the External Friction of States"

# "No State Shall by Force Interfere with the Constitution or Government of Another State,

# "No State Shall, during War, Permit Such Acts of Hostility Which Would Make Mutual Confidence in the Subsequent Peace Impossible: Such Are the Employment of Assassins (percussores), Poisoners (venefici), Breach of Capitulation, and Incitement to Treason (perduellio) in the Opposing State"

Three Definitive Articles would provide not merely a cessation of hostilities, but a foundation on which to build a peace.

# "The Civil Constitution of Every State Should Be Republican"

# "The Law of Nations Shall be Founded on a Federation of Free States"

# "The Law of World Citizenship Shall Be Limited to Conditions of Universal Hospitality"

Kant argued against a world government on the grounds that it would be prone to tyranny. He instead advocated for league of independent republican states akin to the intergovernmental organizations that would emerge over a century and a half later.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814)

The year of the battle at Jena (1806), whenNapoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

overwhelmed Prussia, Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kan ...

in ''Characteristics of the Present Age

A characteristic is a distinguishing feature of a person or thing. It may refer to:

Computing

* Characteristic (biased exponent), an ambiguous term formerly used by some authors to specify some type of exponent of a floating point number

* Charact ...

'' described what he perceived to be a very deep and dominant historical trend:

Supranational movements

International organizations started forming in the late 19th century, among the earliest being the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1863, theTelegraphic Union

The International Telecommunication Union is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information and communication technologies. It was established on 17 May 1865 as the International Telegraph Union ...

in 1865 and the Universal Postal Union in 1874. The increase in international trade at the turn of the 20th century accelerated the formation of international organizations, and, by the start of World War I in 1914, there were approximately 450 of them.

Some notable philosophers and political leaders were also promoting the value of world government during the post-industrial, pre-World War era. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, US President, was convinced that rapid advances in technology and industry would result in greater unity and eventually "one nation, so that armies and navies are no longer necessary." In China, political reformer Kang Youwei viewed human political organization growing into fewer, larger units, eventually into "one world". Bahá'u'lláh founded the Baháʼí Faith teaching that the establishment of world unity and a global federation of nations was a key principle of the religion. Author H. G. Wells was a strong proponent of the creation of a world state, arguing that such a state would ensure world peace and justice.

Karl Marx, the traditional founder of communism, viewed the capitalist epoch being succeeded by a socialist epoch in which the working class throughout the world will unite to render nationalism meaningless.

Support for the idea of establishing international law grew during this period as well. The Institute of International Law

The Institute of International Law ( French: Institut de Droit International) is an organization devoted to the study and development of international law, whose membership comprises the world's leading public international lawyers. The organizat ...

was formed in 1873 by Belgian Jurist Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns, leading to the creation of concrete legal drafts, for example by the Swiss Johaan Bluntschli in 1866. In 1883, James Lorimer published "The Institutes of the Law of Nations" in which he explored the idea of a world government establishing the global rule of law. The first embryonic world parliament, called the Inter-Parliamentary Union

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU; french: Union Interparlementaire, UIP) is an inter-parliamentary institution, international organization of national parliaments. Its primary purpose is to promote democratic governance, accountability, and coop ...

, was organized in 1886 by Cremer and Passy, composed of legislators from many countries. In 1904 the Union formally proposed "an international congress which should meet periodically to discuss international questions".

Theodore Roosevelt

As early as his 1905 statement to Congress, U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt highlighted the need for "an organization of the civilized nations" and cited the international arbitration tribunal at The Hague as a role model to be advanced further. During his acceptance speech for the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize, Roosevelt described a world federation as a "master stroke" and advocated for some form of international police power to maintain peace. HistorianWilliam Roscoe Thayer

William Roscoe Thayer (January 16, 1859 – September 7, 1923) was an American author and editor who wrote about Italian history.

Biography

Thayer was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 16, 1859. He studied at St. Mark's Academy, Conco ...

observed that the speech "foreshadowed many of the terms which have since been preached by the advocates of a League of Nations", which would not be established for another 14 years. Hamilton Holt

Hamilton Holt (August 18, 1872 – April 26, 1951) was an American educator, editor, author and politician.

Biography

Holt was born on August 18, 1872 in Brooklyn, New York City to George Chandler Holt and his wife Mary Louisa Bowen Holt. His fat ...

of ''The Independent'' lauded Roosevelt's plan for a "Federation of the World", writing that not since the "Great Design" of Henry IV has "so comprehensive a plan" for universal peace been proposed.

Although Roosevelt supported global government conceptually, he was critical of specific proposals and of leaders of organizations promoting the cause of international governance. According to historian John Milton Cooper

John Milton Cooper Jr. (born 1940) is an American historian, author, and educator. He specializes in late 19th and early 20th-century American political and diplomatic history with a particular focus on presidential history. His 2009 biography of W ...

, Roosevelt praised the plan of his presidential successor, William Howard Taft, for "a league under existing conditions and with such wisdom in refusing to let adherence to the principle be clouded by insistence upon improper or unimportant methods of enforcement that we can speak of the league as a practical matter."

In a 1907 letter to Andrew Carnegie, Roosevelt expressed his hope "to see The Hague Court greatly increased in power and permanency", and in one of his very last public speeches he said: "Let us support any reasonable plan whether in the form of a League of Nations or in any other shape, which bids fair to lessen the probable number of future wars and to limit their scope."

Founding of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LoN) was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919–1920. At its largest size from 28 September 1934 to 23 February 1935, it had 58 members. The League's goals included upholding the Rights of Man, such as the rights of non-whites, women, and soldiers; disarmament, preventing war throughcollective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats t ...

, settling disputes between countries through negotiation, diplomacy, and improving global quality of life. The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift in thought from the preceding hundred years. The League lacked its own armed force and so depended on the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

to enforce its resolutions and economic sanctions and provide an army, when needed. However, these powers proved reluctant to do so. Lacking many of the key elements necessary to maintain world peace, the League failed to prevent World War II. Adolf Hitler withdrew Germany from the League of Nations once he planned to take over Europe. The rest of the Axis Powers soon followed him. Having failed its primary goal, the League of Nations fell apart. The League of Nations consisted of the Assembly, the council, and the Permanent Secretariat. Below these were many agencies. The Assembly was where delegates from all member states conferred. Each country was allowed three representatives and one vote.

Competing visions during World War II

The Nazi Party of Germany envisaged the establishment of a world government under the complete hegemony of the Third Reich.Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1995) ''Germany, Hitler, and World War II: Essays in modern German and world history''. Cambridge University Pressp. 36

In its move to overthrow the post- World War I Treaty of Versailles, Germany had already withdrawn itself from the League of Nations, and it did not intend to join a similar internationalist organization ever again. In his stated political aim of expanding the living space ('' Lebensraum'') of the Germanic people by destroying or driving out "lesser-deserving races" in and from other territories, dictator Adolf Hitler devised an ideological system of self-perpetuating

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

, in which the growth of a state's population would require the conquest of more territory which would, in turn, lead to a further growth in population which would then require even more conquests. In 1927, Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

relayed to Walther Hewel Hitler's belief that world peace could only be acquired "when one power, the racially best one, has attained uncontested supremacy". When this control would be achieved, this power could then set up for itself a world police and assure itself "the necessary living space.... The lower races will have to restrict themselves accordingly".

During its imperial period (1868–1947), the Japanese Empire

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

elaborated a worldview, "'' Hakkō ichiu''", translated as "eight corners of the world under one roof". This was the idea behind the attempt to establish a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and behind the struggle for world domination. The

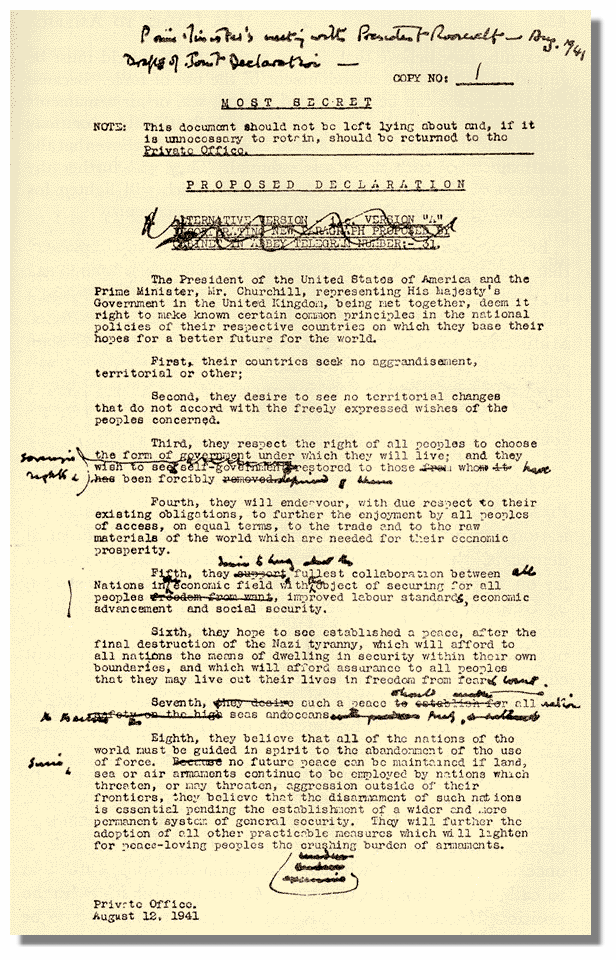

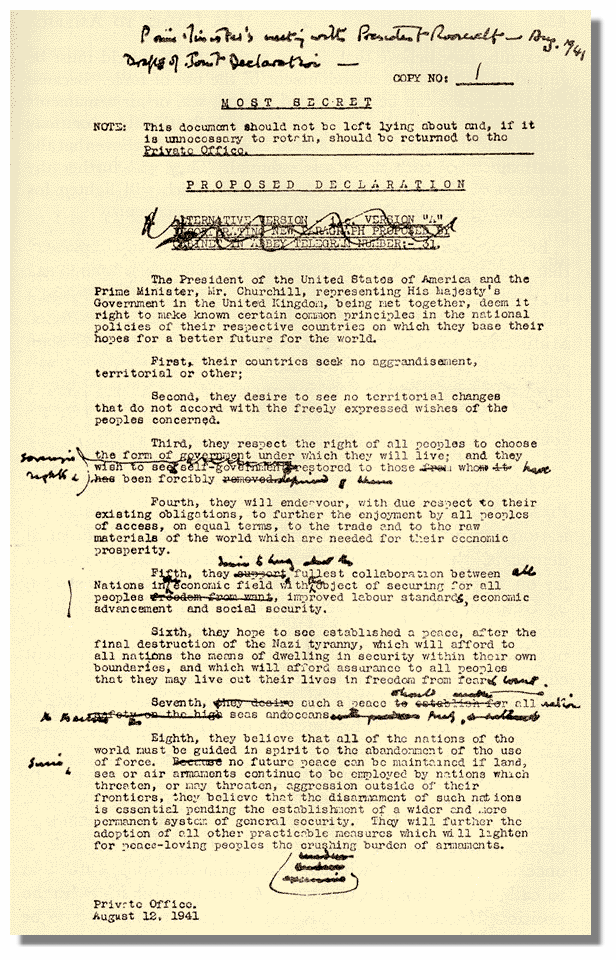

The Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

was a published statement agreed between the United Kingdom and the United States. It was intended as the blueprint for the postwar world after World War II, and turned out to be the foundation for many of the international agreements that currently shape the world. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its pre ...

(GATT), the post-war independence of British and French possessions, and much more are derived from the Atlantic Charter. The Atlantic charter was made to show the goals of the allied powers during World War II. It first started with the United States and Great Britain, and later all the allies would follow the charter. Some goals include access to raw materials, reduction of trade restrictions, and freedom from fear and wants. The name, The Atlantic Charter, came from a newspaper that coined the title. However, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

would use it, and from then on the Atlantic Charter was the official name. In retaliation, the Axis powers would raise their morale and try to work their way into Great Britain. The Atlantic Charter was a stepping stone into the creation of the United Nations.

On June 5, 1948, at the dedication of the War Memorial in Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

's remarked, "We must make the United Nations continue to work, and to be a going concern, to see that difficulties between nations may be settled just as we settle difficulties between States here in the United States. When Kansas and Colorado fall out over the waters in the Arkansas River, they don't go to war over it; they go to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

, and the matter is settled in a just and honorable way. There is not a difficulty in the whole world that cannot be settled in exactly the same way in a world court". The cultural moment of the late 1940s was the peak of World Federalism among Americans.

Founding of the United Nations

crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

itself. As the war's conclusion drew near, many shocked voices called for the establishment of institutions able to permanently prevent deadly international conflicts. This led to the founding of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, which adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. Many, however, felt that the UN, essentially a forum for discussion and coordination between sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

governments, was insufficiently empowered for the task. A number of prominent persons, such as Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, Bertrand Russell and Mahatma Gandhi, called on governments to proceed further by taking gradual steps towards forming an effectual federal world government. The United Nations main goal is to work on international law, international security, economic development, human rights, social progress, and eventually world peace. The United Nations replaced the League of Nations in 1945, after World War II. Almost every internationally recognized country is in the U.N.; as it contains 193 member states out of the 196 total nations of the world. The United Nations gather regularly in order to solve big problems throughout the world. There are six official languages: Arabic, Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

, English, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Russian and Spanish. The United Nations is also financed by some of the wealthiest nations. The flag shows the Earth from a map that shows all of the populated continents.

direct election

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...

of UN parliament members by citizens worldwide. The idea of a world parliament was raised at the founding of the League of Nations in the 1920s and again following the end of World War II in 1945, but remained dormant throughout the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. In the 1990s and 2000s, the rise of global trade and the power of world organizations that govern it led to calls for a parliamentary assembly to scrutinize their activity. The Campaign for a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

* Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* B ...

was formed in 2007 by Democracy Without Borders

Democracy Without Borders, or DWB is an international nongovernmental organization established in 2017 with national chapters across the world and a legal seat in Berlin that promotes "global democracy, global governance and global citizenship". ...

to coordinate pro-UNPA efforts, which as of January 2019 has received the support of over 1,500 Members of Parliament from over 100 countries worldwide, in addition to numerous non-governmental organizations, Nobel

Nobel often refers to:

*Nobel Prize, awarded annually since 1901, from the bequest of Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel

Nobel may also refer to:

Companies

*AkzoNobel, the result of the merger between Akzo and Nobel Industries in 1994

*Branobel, or ...

and Right Livelihood laureates and heads or former heads of state or government and foreign ministers.

In France, 1948, Garry Davis began an unauthorized speech calling for a world government from the balcony of the UN General Assembly, until he was dragged away by the guards. Davis renounced his American citizenship and started a Registry of World Citizens

The World Service Authority (WSA), founded in 1953 by Garry Davis, is a non-profit organization that claims to educate about and promote "world citizenship", "world law", and world government. It is best known for selling unofficial fantasy do ...

. On September 4, 1953, Davis announced from the city hall of Ellsworth, Maine, the formation of the "World Government of World Citizens" based on 3 "World Laws"One God (or Absolute Value), One World, and One Humanity. Following this declaration, mandated, he claimed, by Article twenty one, Section three of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, he formed the United World Service Authority in New York City as the administrative agency of the new government. Its first task was to design and begin selling "World Passports", which the organisation argues is legitimatised by on Article 13, Section 2 of the UDHR.

World Federalist Movement

The years between the end of World War II and the start of the Korean War—which roughly marked the entrenchment ofCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

polarity—saw a flourishing of the nascent world federalist movement. Wendell Willkie's 1943 book '' One World'' sold over 2 million copies, laying out many of the argument and principles that would inspire global federalism. A contemporaneous work, Emery Reves' ''The Anatomy of Peace

''The Anatomy of Peace'' () was a book by Emery Reves, first published in 1945. It expressed the world federalist sentiments shared by Albert Einstein and many others in the late 1940s, in the period immediately following World War II.

The books ...

'' (1945), argued for replacing the UN with a federal world government. The world federalist movement in the U.S., led by diverse figures such as Grenville Clark

Grenville Clark (November 5, 1882 – January 13, 1967) was a 20th-century American Wall Street lawyer, co-founder of Root Clark & Bird (later Dewey Ballantine, then Dewey & LeBoeuf), member of the Harvard Corporation, co-author of the book '' Wo ...

, Norman Cousins

Norman Cousins (June 24, 1915 – November 30, 1990) was an American political journalist, author, professor, and world peace advocate.

Early life

Cousins was born to Jewish immigrant parents Samuel Cousins and Sarah Babushkin Cousins, in West ...

, and Alan Cranston

Alan MacGregor Cranston (June 19, 1914 – December 31, 2000) was an American politician and journalist who served as a United States Senator from California from 1969 to 1993, and as a President of the World Federalist Association from 1949 to 1 ...

, grew larger and more prominent: in 1947, several grassroots organizations merged to form the United World Federalists

Citizens for Global Solutions is a grassroots membership organization in the United States.

History

Five world federalist organizations merged in 1947 to form the United World Federalists, Inc., later renamed World Federalists-USA. In 1975, ...

—later renamed the World Federalist Association, then Citizens for Global Solutions—

The dash is a punctuation mark consisting of a long horizontal line. It is similar in appearance to the hyphen but is longer and sometimes higher from the baseline. The most common versions are the endash , generally longer than the hyphen b ...

Elisabeth Mann Borgese

Elisabeth Veronika Mann Borgese, (24 April 1918 – 8 February 2002) was an internationally recognized expert on maritime law and policy and the protection of the environment. Called "the mother of the oceans", she has received the Order o ...

, which was devoted to world government; its title was ''Common Cause

Common Cause is a watchdog group based in Washington, D.C., with chapters in 35 states. It was founded in 1970 by John W. Gardner, a Republican, who was the former Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in the administration of President L ...

''.

In 1949, six U.S. states — California, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, New Jersey, and North Carolina — applied for an Article V convention

A convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution, also referred to as an Article V Convention or amendatory convention; is one of two methods authorized by Article Five of the United States Constitution whereby amendments to ...

to propose an amendment “to enable the participation of the United States in a world federal government.” Multiple other state legislatures introduced or debated the same proposal. These resolutions were part of this effort.

Similar movements concurrently formed in many other countries, culminating in a 1947 meeting in Montreux, Switzerland

Montreux (, , ; frp, Montrolx) is a Swiss municipality and town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Alps. It belongs to the district of Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland, and has a population of approxima ...

that formed a global coalition called the World Federalist Movement. By 1950, the movement claimed 56 member groups in 22 countries, with some 156,000 members.

Cold War and current system

By 1950, theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

began to dominate international politics and the UN Security Council became effectively paralyzed by its permanent members' ability to exercise veto power. The United Nations Security Council Resolution 82 and 83 backed the defense of South Korea, although the Soviets were then boycotting meetings in protest.

While enthusiasm for multinational federalism in Europe incrementally led, over the following decades, to the formation of the European Union, the Cold War eliminated the prospects of any progress towards federation with a more global scope. Global integration became stagnant during the Cold War, and the conflict became the driver behind one-third of all wars during the period. The idea of world government all but disappeared from wide public discourse.

Post-Cold War

As the Cold War dwindled in 1991, interest in a federal world government was renewed. When the conflict ended by 1992, without the external assistance, many proxy wars petered out or ended by negotiated settlements. This kicked off a period in the 1990s of unprecedented international activism and an expansion of international institutions. According to the ''Human Security Report 2005 The ''Human Security Report 2005'' is a report outlining declining world trends of global violence from the early 1990s to 2003. The study reported major worldwide declines in the number of armed conflicts, genocides, military coups, and internatio ...

'', this was the first effective functioning of the United Nations as it was designed to operate.

The most visible achievement of the world federalism movement during the 1990s is the Rome Statute of 1998, which led to the establishment of the International Criminal Court in 2002. In Europe, progress towards forming a federal union of European states gained much momentum, starting in 1952 as a trade deal between the German and French people led, in 1992, to the Maastricht Treaty that established the name and enlarged the agreement that the European Union is based upon. The EU expanded (1995, 2004, 2007, 2013) to encompass, in 2013, over half a billion people in 28 member states (27 after Brexit). Following the EU's example, other supranational union

A supranational union is a type of international organization that is empowered to directly exercise some of the powers and functions otherwise reserved to states. A supranational organization involves a greater transfer of or limitation of ...

s were established, including the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the Africa ...

in 2002, the Union of South American Nations in 2008, and the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015.

Current system of global governance

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

in most cases. There are numerous bodies, institutions, unions, coalitions, agreements and contracts between these units of authority

In the fields of sociology and political science, authority is the legitimate power of a person or group over other people. In a civil state, ''authority'' is practiced in ways such a judicial branch or an executive branch of government.''The N ...

, but, except in cases where a nation is under military occupation by another, ''all'' such arrangements depend on the continued consent of the participant nations. Countries that violate or do not enforce international laws may be subject to penalty or coercion often in the form of economic limitations such as embargo by cooperating countries, even if the violating country is not part of the United Nations. In this way a country's cooperation in international affairs is voluntary, but non-cooperation still has diplomatic

Diplomatics (in American English, and in most anglophone countries), or diplomatic (in British English), is a scholarly discipline centred on the critical analysis of documents: especially, historical documents. It focuses on the conventions, p ...

consequences.

A functioning system of International law encompasses international treaties, customs and globally accepted legal principles. With the exceptions of cases brought before the ICC and ICJ, the laws are interpreted by national courts. Many violations of treaty or customary law obligations are overlooked. International Criminal Court (ICC) was a relatively recent development in international law, it is the first permanent international criminal court established to ensure that the gravest international crimes ( war crimes, genocide, other crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

, etc.) do not go unpunished. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome, Italy on 17 July 1998Michael P. Scharf (August 1998)''Results of the R ...

establishing the ICC and its jurisdiction was signed by 139 national governments, of which 100 ratified it by October 2005.

The United Nations (UN) is the primary formal organization coordinating activities between states on a global scale and the only inter-governmental organization with a truly universal membership (193 governments). In addition to the main organs and various humanitarian programs and commissions of the UN itself, there are about 20 functional organizations affiliated with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), such as the World Health Organization, the International Labour Organization, and International Telecommunication Union., Chart Of particular interest politically are the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization.

Militarily, the UN deploys peacekeeping forces, usually to build and maintain post-conflict peace and stability. When a more aggressive international military action is undertaken, either '' ad hoc'' coalitions (for example, the Multi-National Force – Iraq) or regional military alliances (for example, NATO) are used. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) formed together in July 1944 at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, to foster global monetary cooperation and to fight poverty by financially assisting states in need. These institutions have been criticized as simply oligarchic hegemonies of the Great Powers, most notably the United States, which maintains the only veto, for instance, in the International Monetary Fund. The World Trade Organization (WTO) sets the rules of international trade. It has a semi-legislative body (the General Council, reaching decisions by consensus) and a judicial body (the Dispute Settlement Body). Another influential economical international organization is the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries ...

(OECD), with membership of 30 democratic members.

Informal global influences

In addition to the formal, or semi-formal, international organizations and laws mentioned above, many other mechanisms act to regulate human activities across national borders. International trade has the effect of requiring cooperation and interdependency between nations without a political body. Trans-national (or multi-national) corporations, some with resources exceeding those available to most governments, govern activities of people on a global scale. The rapid increase in the volume of trans-border digital communications and mass-media distribution (e.g., Internet, satellite television) has allowed information, ideas, and opinions to rapidly spread across the world, creating a complex web of international coordination and influence, mostly outside the control of any formal organizations or laws.Examples of regional integration of states

There are a number of regional organizations that, while not supranational unions, have adopted or intend to adopt policies that may lead to a similar sort of integration in some respects. The European Union is generally recognized as the most integrated among these. *African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the Africa ...

(AU)

* Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

* Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

* Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

* Central American Integration System (SICA)

* Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

* Commonwealth of Nations

* Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (CCASG)

* East African Community (EAC)

* Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)

* European Union (EU)

* North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

* Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

(OAS)

* South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)

* Turkic Council (TurkKon)

* Union of South American Nations (UNASUR)

* Union State

Other organisations that have also discussed greater integration include:

* Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

into an "Arab Union

The Arab Union is a theoretical political union of the Arab states. The term was first used when the British Empire promised the Arabs a united independent state in return for revolting against the Ottoman Empire, with whom Britain was at war. ...

"

* Caribbean Community (CARICOM) into a "Caribbean Federation"

* North American Free Trade Agreement

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA ; es, Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte, TLCAN; french: Accord de libre-échange nord-américain, ALÉNA) was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States that crea ...

(NAFTA) into a " North American Union"

* Pacific Islands Forum

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) is an inter-governmental organization that aims to enhance cooperation between countries and territories of Oceania, including formation of a trade bloc and regional peacekeeping operations. It was founded in 197 ...

into a "Pacific Union

The Pacific Union was a proposed development of the Pacific Islands Forum, suggested in 2003 by a committee of the Australian Senate, into a political and economic intergovernmentalism, intergovernmental community. The union, if formed, would hav ...

"

See also

*Cosmopolitanism

Cosmopolitanism is the idea that all human beings are members of a single community. Its adherents are known as cosmopolitan or cosmopolite. Cosmopolitanism is both prescriptive and aspirational, believing humans can and should be " world citizens ...

* Global civics Global civics proposes to understand civics in a global sense as a social contract among all world citizens in an age of interdependence and interaction. The disseminators of the concept define it as the notion that we have certain rights and respon ...

* Global governance

Global governance refers to institutions that coordinate the behavior of transnational actors, facilitate cooperation, resolve disputes, and alleviate collective action problems. Global governance broadly entails making, monitoring, and enfor ...

* New world order (Baháʼí)

* New world order (politics)

* New World Order (conspiracy theory)

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Cabrera, Luis. Political Theory of Global Justice: A Cosmopolitan Case for the World State (London: Routledge, 2004;2006). * Domingo, Rafael, The New Global Law (Cambridge University Press, 2010). * Marchetti, Raffaele. Global Democracy: For and Against. Ethical Theory, Institutional Design and Social Struggles (London: Routledge, 2008) Amazon.com, . * Tamir, Yael. "Who's Afraid of a Global State?" in Kjell Goldman, Ulf Hannerz, and Charles Westin, eds., Nationalism and Internationalism in the post–Cold War Era (London: Routledge, 2000). * Wendt, Alexander. "Why a World State is Inevitable," European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 9, No. 4 (2003), pp. 491–542 *External links

* * Immanuel Kant"Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch"

(English translation of "''Zum ewigen Frieden''")

World Government Movement

{{DEFAULTSORT:World Government Government Government