Death Cap Mushroom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Amanita phalloides'' (), commonly known as the death cap, is a deadly poisonous basidiomycete fungus, one of many in the genus '' Amanita''. Widely distributed across Europe, but now sprouting in other parts of the world, ''A. phalloides'' forms

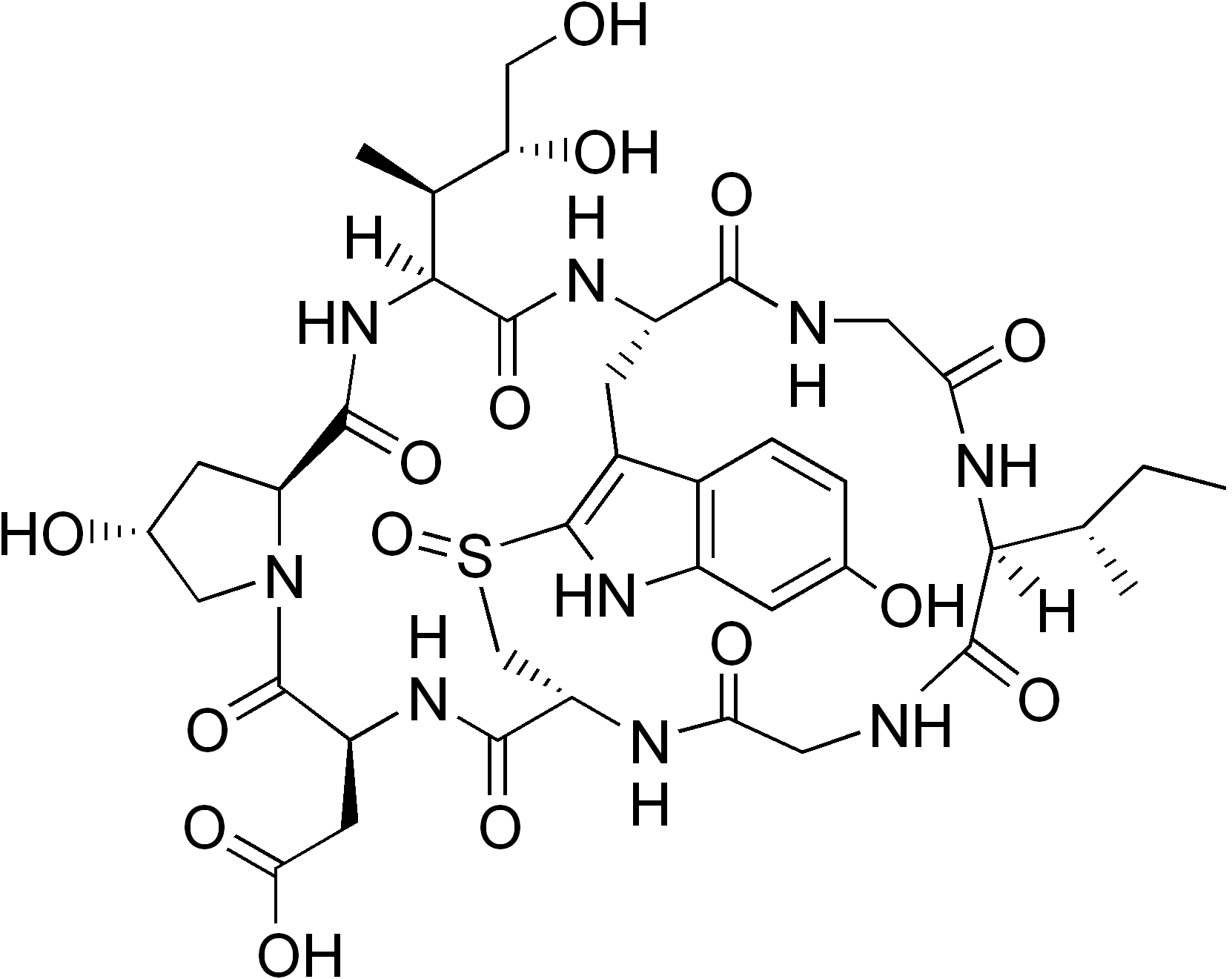

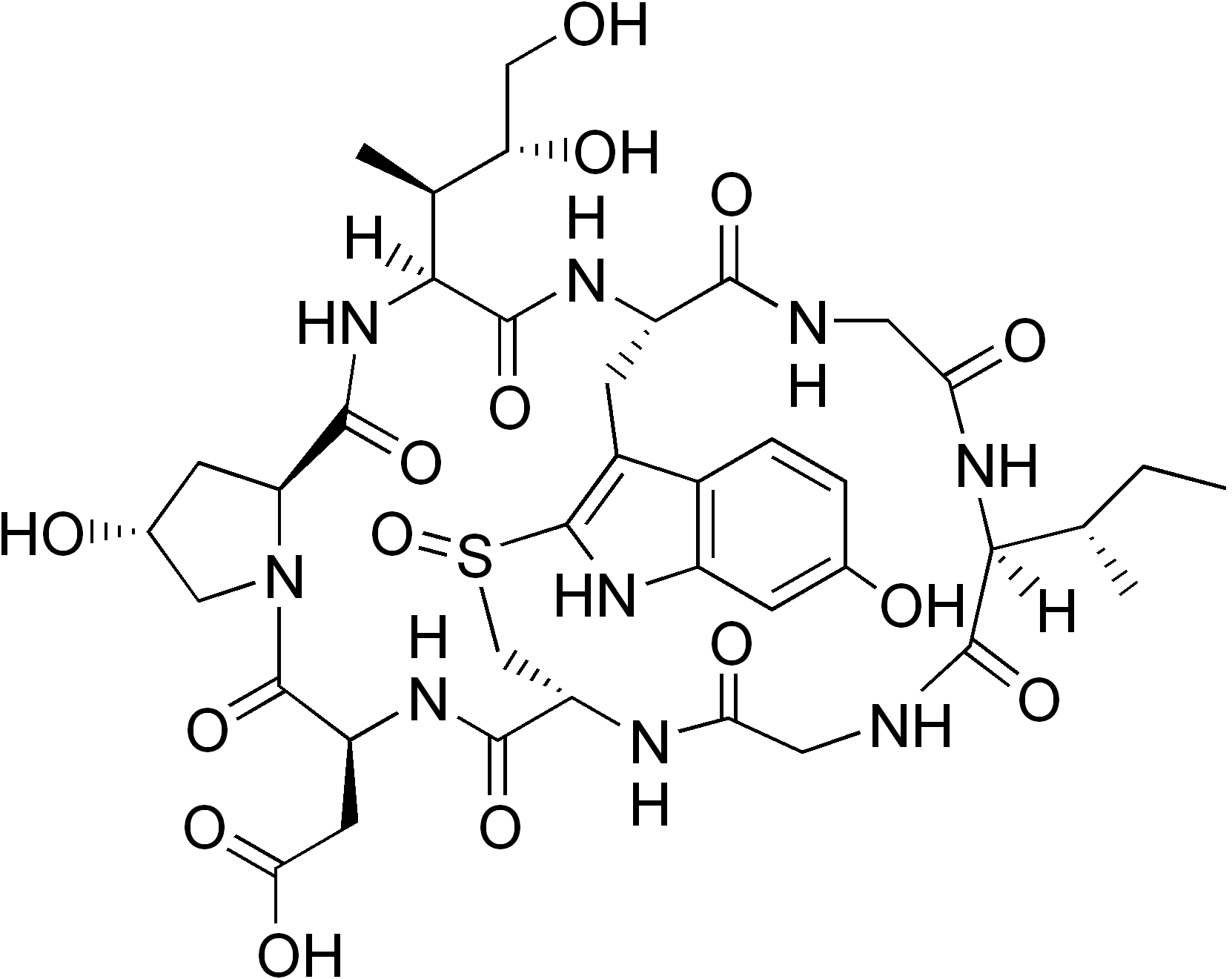

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped) peptides, spread throughout the mushroom tissue: the amatoxins and the

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped) peptides, spread throughout the mushroom tissue: the amatoxins and the

As the common name suggests, the fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal

As the common name suggests, the fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal

UK Telegraph Newspaper (September 2008) - One woman dead, another critically ill after eating Death Cap fungi

* ttp://www.mushroomexpert.com/amanita_phalloides.html ''Amanita phalloides'': the death cap

''Amanita phalloides'': Invasion of the Death Cap

* ttp://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Amanita_phalloides.html California Fungi—Amanita phalloides

Death cap in Australia - ANBG website

On the Trail of the Death Cap Mushroom

from National Public Radio * {{Featured article phalloides Fungi of Africa Fungi of Europe Deadly fungi Hepatotoxins Fungi described in 1821

ectomycorrhiza

An ectomycorrhiza (from Greek ἐκτός ', "outside", μύκης ', "fungus", and ῥίζα ', "root"; pl. ectomycorrhizas or ectomycorrhizae, abbreviated EcM) is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobi ...

s with various broadleaved trees. In some cases, the death cap has been introduced to new regions with the cultivation of non-native species of oak, chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce.

The unrelat ...

, and pine. The large fruiting bodies ( mushrooms) appear in summer and autumn; the caps are generally greenish in colour with a white stipe and gills. The cap colour is variable, including white forms, and is thus not a reliable identifier.

These toxic mushrooms resemble several edible species (most notably Caesar's mushroom

''Amanita caesarea'', commonly known as Caesar's mushroom, is a highly regarded edible mushroom in the genus ''Amanita'', native to southern Europe and North Africa. While it was first species description, described by Giovanni Antonio Scopol ...

and the straw mushroom) commonly consumed by humans, increasing the risk of accidental poisoning. Amatoxins, the class of toxins found in these mushrooms, are thermostable: they resist changes due to heat, so their toxic effects are not reduced by cooking.

''A. phalloides'' is one of the most poisonous of all known mushrooms. It is estimated that as little as half a mushroom contains enough toxin to kill an adult human. It has been involved in the majority of human deaths from mushroom poisoning,Benjamin, p.200. possibly including Roman Emperor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

in AD 54 and Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Charles VI in 1740. It has been the subject of much research and many of its biologically active agents have been isolated. The principal toxic constituent is α-amanitin, which causes liver and kidney failure.

Taxonomy

The death cap is named in Latin as such in the correspondence between the English physicianThomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne (; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a deep curi ...

and Christopher Merrett. Also, it was described by French botanist Sébastien Vaillant in 1727, who gave a succinct phrase name "''Fungus phalloides, annulatus, sordide virescens, et patulus''"—a recognizable name for the fungus today. Though the scientific name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''phalloides'' means "phallus-shaped", it is unclear whether it is named for its resemblance to a literal phallus

A phallus is a penis (especially when erect), an object that resembles a penis, or a mimetic image of an erect penis. In art history a figure with an erect penis is described as ithyphallic.

Any object that symbolically—or, more precisel ...

or the stinkhorn mushrooms ''Phallus

A phallus is a penis (especially when erect), an object that resembles a penis, or a mimetic image of an erect penis. In art history a figure with an erect penis is described as ithyphallic.

Any object that symbolically—or, more precisel ...

''.

In 1821, Elias Magnus Fries

Elias Magnus Fries (15 August 1794 – 8 February 1878) was a Swedish mycologist and botanist.

Career

Fries was born at Femsjö (Hylte Municipality), Småland, the son of the pastor there. He attended school in Växjö.

He acquired ...

described it as ''Agaricus phalloides'', but included all white amanitas within its description. Finally, in 1833, Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link

Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link (2 February 1767 – 1 January 1851) was a German naturalist and botanist.

Biography

Link was born at Hildesheim as a son of the minister August Heinrich Link (1738–1783), who taught him love of nature throug ...

settled on the name ''Amanita phalloides'', after Persoon

Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (1 February 1761 – 16 November 1836) was a German mycologist who made additions to Linnaeus' mushroom taxonomy.

Early life

Persoon was born in South Africa at the Cape of Good Hope, the third child of an immig ...

had named it ''Amanita viridis'' 30 years earlier. Although Louis Secretan

Louis (Gabriel Abraam Samuel Jean) Secretan (15 September 1758 – 24 May 1839) was a Swiss lawyer, politician and mycologist. He published ''Mycologie Suisse'' in 1833, though the names are not regarded as valid unless republished by other author ...

's use of the name ''A. phalloides'' predates Link's, it has been rejected for nomenclatural purposes because Secretan's works did not use binomial nomenclature consistently; some taxonomists have, however, disagreed with this opinion.

''Amanita phalloides'' is the type species of ''Amanita'' section Phalloideae, a group that contains all of the deadly poisonous ''Amanita'' species thus far identified. Most notable of these are the species known as destroying angels, namely '' A. virosa'', '' A. bisporigera'' and '' A. ocreata'', as well as the fool's mushroom ''( A. verna)''. The term "destroying angel" has been applied to ''A. phalloides'' at times, but "death cap" is by far the most common vernacular name used in English. Other common names also listed include "stinking amanita" and "deadly amanita".Benjamin, p.203

A rarely appearing, all-white form was initially described ''A. phalloides'' f. ''alba'' by Max Britzelmayr,Jordan & Wheeler, p. 109 though its status has been unclear. It is often found growing amid normally colored death caps. It has been described, in 2004, as a distinct variety and includes what was termed ''A. verna'' var. ''tarda''. The true ''A. verna'' fruits in spring and turns yellow with KOH solution, whereas ''A. phalloides'' never does.

Description

The death cap has a large and imposing epigeous (aboveground) fruiting body (basidiocarp), usually with a pileus (cap) from across, initially rounded and hemispherical, but flattening with age. The color of the cap can be pale-green, yellowish-green, olive-green, bronze, or (in one form) white; it is often paler toward the margins, which can have darker streaks; it is also often paler after rain. The cap surface is sticky when wet and easily peeled, a troublesome feature, as that is allegedly a feature of edible fungi.Jordan & Wheeler, p.99 The remains of the partial veil are seen as a skirtlike, floppyannulus

Annulus (or anulus) or annular indicates a ring- or donut-shaped area or structure. It may refer to:

Human anatomy

* ''Anulus fibrosus disci intervertebralis'', spinal structure

* Annulus of Zinn, a.k.a. annular tendon or ''anulus tendineus com ...

usually about below the cap. The crowded white lamellae (gills) are free. The stipe is white with a scattering of grayish-olive scales and is long and thick, with a swollen, ragged, sac-like white volva (base). As the volva, which may be hidden by leaf litter, is a distinctive and diagnostic feature, it is important to remove some debris to check for it.Jordan & Wheeler, p.108

The smell has been described as initially faint and honey-sweet, but strengthening over time to become overpowering, sickly-sweet and objectionable.Zeitlmayr, p.61 Young specimens first emerge from the ground resembling a white egg covered by a universal veil, which then breaks, leaving the volva as a remnant. The spore print is white, a common feature of ''Amanita''. The transparent spores are globular to egg-shaped, measure 8–10 μm

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American spelling), also commonly known as a micron, is a unit of length in the International System of Unit ...

(0.3–0.4 mil) long, and stain blue with iodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid at standard conditions that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

. The gills, in contrast, stain pallid lilac or pink with concentrated sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

.

Biochemistry

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped) peptides, spread throughout the mushroom tissue: the amatoxins and the

The species is now known to contain two main groups of toxins, both multicyclic (ring-shaped) peptides, spread throughout the mushroom tissue: the amatoxins and the phallotoxin The phallotoxins consist of at least seven compounds, all of which are bicyclic heptapeptides (seven amino acids), isolated from the death cap mushroom ''(Amanita phalloides)''. They differ from the closely related amatoxins by being one residue sma ...

s. Another toxin is phallolysin Phallolysin is a Protein found the ''Amanita phalloides'' species of the '' Amanita'' genus of mushrooms, the species commonly known as the death cap mushroom. The protein is toxic and causes Cytolysis in many cells found in animals, and is noted f ...

, which has shown some hemolytic (red blood cell–destroying) activity '' in vitro''. An unrelated compound, antamanide

Antamanide is a cyclic decapeptide isolated from a fungus, the death cap: ''Amanita phalloides''. It is being studied as a potential anti-toxin against the effects of phalloidin and for its potential for treating edema. It contains 1 valine residu ...

, has also been isolated.

Amatoxins consist of at least eight compounds with a similar structure, that of eight amino-acid rings; they were isolated in 1941 by Heinrich O. Wieland and Rudolf Hallermayer of the University of Munich. Of the amatoxins, α-Amanitin is the chief component and along with β-amanitin is likely responsible for the toxic effects. Their major toxic mechanism is the inhibition of RNA polymerase II, a vital enzyme in the synthesis of messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

(mRNA), microRNA, and small nuclear RNA ( snRNA). Without mRNA, essential protein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside Cell (biology), cells, homeostasis, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via Proteolysis, degradation or Protein targeting, export) through the product ...

and hence cell metabolism grind to a halt and the cell dies. The liver is the principal organ affected, as it is the organ which is first encountered after absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, though other organs, especially the kidneys, are susceptible.Benjamin, p.217 The RNA polymerase of ''Amanita phalloides'' is insensitive to the effects of amatoxins, so the mushroom does not poison itself.

The phallotoxins consist of at least seven compounds, all of which have seven similar peptide rings. Phalloidin was isolated in 1937 by Feodor Lynen, Heinrich Wieland's student and son-in-law, and Ulrich Wieland of the University of Munich. Though phallotoxins are highly toxic to liver cells, they have since been found to add little to the death cap's toxicity, as they are not absorbed through the gut. Furthermore, phalloidin is also found in the edible (and sought-after) blusher (''A. rubescens''). Another group of minor active peptides are the virotoxins, which consist of six similar monocyclic heptapeptides. Like the phallotoxins, they do not induce any acute toxicity after ingestion in humans.

The genome of the death cap has been sequenced.

Similarity to edible species

''A. phalloides'' is similar to the edible paddy straw mushroom ('' Volvariella volvacea'')Benjamin, pp.198–199 and '' A. princeps'', commonly known as "white Caesar". Some may mistake juvenile death caps for edible puffballs or mature specimens for other edible ''Amanita'' species, such as '' A. lanei'', so some authorities recommend avoiding the collecting of ''Amanita'' species for the table altogether. The white form of ''A. phalloides'' may be mistaken for edible species of '' Agaricus'', especially the young fruitbodies whose unexpanded caps conceal the telltale white gills; all mature species of ''Agaricus'' have dark-colored gills. In Europe, other similarly green-capped species collected by mushroom hunters include various green-hued brittlegills of the genus '' Russula'' and the formerly popular '' Tricholoma equestre'', now regarded as hazardous owing to a series of restaurant poisonings in France. Brittlegills, such as ''Russula heterophylla

The edible wild mushroom ''Russula heterophylla'', that has lately been given the common name of the greasy green brittlegill is placed in the genus '' Russula'', the members of which are mostly known as brittlegills. It is a variably colored ...

'', '' R. aeruginea'', and '' R. virescens'', can be distinguished by their brittle flesh and the lack of both volva and ring.Zeitlmayr, p.62 Other similar species include '' A. subjunquillea'' in eastern Asia and '' A. arocheae'', which ranges from Andean Colombia north at least as far as central Mexico, both of which are also poisonous.

Distribution and habitat

The death cap is native to Europe, where it is widespread. It is found from the southern coastal regions of Scandinavia in the north, to Ireland in the west, east to Poland and western Russia, and south throughout the Balkans, in Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal in theMediterranean basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

, and in Morocco and Algeria in north Africa. In west Asia, it has been reported from forests of northern Iran. There are records from further east in Asia but these have yet to be confirmed as ''A. phalloides''.

By the end of the 19th century, Charles Horton Peck had reported ''A. phalloides'' in North America. In 1918, samples from the eastern United States were identified as being a distinct though similar species, '' A. brunnescens'', by George Francis Atkinson of Cornell University. By the 1970s, it had become clear that ''A. phalloides'' does occur in the United States, apparently having been introduced from Europe alongside chestnuts, with populations on the West and East Coasts.Benjamin, p.204 A 2006 historical review concluded the East Coast populations were inadvertently introduced, likely on the roots of other purposely imported plants such as chestnuts. The origins of the West Coast populations remained unclear, due to scant historical records, but a 2009 genetic study provided strong evidence for the introduced status of the fungus on the west coast of North America. Observations of various collections of ''A. phalloides'', from conifers rather than native forests, have led to the hypothesis that the species was introduced to North America multiple times. It is hypothesized that the various introductions led to multiple genotypes which are adapted to either oaks or conifers.

''A. phalloides'' has been conveyed to new countries across the Southern Hemisphere with the importation of hardwoods and conifers. Introduced oaks appear to have been the vector to Australia and South America; populations under oaks have been recorded from Melbourne and Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

(where two people died in January 2012, of four who were poisoned) and Adelaide, as well as Uruguay. It has been recorded under other introduced trees in Argentina and Chile.

Pine plantations are associated with the fungus in Tanzania and South Africa, where it is also found under oaks and poplars. A number of deaths in India have been attributed to it.

Ecology

It isectomycorrhiza

An ectomycorrhiza (from Greek ἐκτός ', "outside", μύκης ', "fungus", and ῥίζα ', "root"; pl. ectomycorrhizas or ectomycorrhizae, abbreviated EcM) is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobi ...

lly associated with several tree species and is symbiotic with them. In Europe, these include hardwood

Hardwood is wood from dicot trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostly evergreen. Hardwood (which comes from ...

and, less frequently, conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

species. It appears most commonly under oaks, but also under beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engle ...

es, chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce.

The unrelat ...

s, horse-chestnuts, birches, filberts, hornbeams, pines, and spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

s. In other areas, ''A. phalloides'' may also be associated with these trees or with only some species and not others. In coastal California, for example, ''A. phalloides'' is associated with coast live oak, but not with the various coastal pine species, such as Monterey pine. In countries where it has been introduced, it has been restricted to those exotic trees with which it would associate in its natural range. There is, however, evidence of ''A. phalloides'' associating with hemlock and with genera of the Myrtaceae

Myrtaceae, the myrtle family, is a family of dicotyledonous plants placed within the order Myrtales. Myrtle, pōhutukawa, bay rum tree, clove, guava, acca (feijoa), allspice, and eucalyptus are some notable members of this group. All speci ...

: '' Eucalyptus'' in Tanzania and Algeria, and ''Leptospermum

''Leptospermum'' is a genus of shrubs and small trees in the myrtle family Myrtaceae commonly known as tea trees, although this name is sometimes also used for some species of ''Melaleuca''. Most species are endemic to Australia, with the greate ...

'' and '' Kunzea'' in New Zealand, suggesting that the species may have invasive potential. It may have also been anthropogenically introduced to the island of Cyprus, where it has been documented to fruit within '' Corylus avellana'' plantations.

Toxicity

As the common name suggests, the fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal

As the common name suggests, the fungus is highly toxic, and is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisoning

Mushroom poisoning is poisoning resulting from the ingestion of mushrooms that contain toxic substances. Its symptoms can vary from slight gastrointestinal discomfort to death in about 10 days. Mushroom toxins are secondary metabolites produced by ...

s worldwide. Its biochemistry has been researched intensively for decades, and , or half a cap, of this mushroom is estimated to be enough to kill a human.Benjamin, p.211 On average, one person dies a year in North America from death cap ingestion. The toxins of the death cap mushrooms primarily target the liver, but other organs, such as the kidneys, are also affected. Symptoms of death cap mushroom toxicity usually occur 6 to 12 hours after ingestion. Symptoms of ingestion of the death cap mushroom may include nausea and vomiting, which is then followed by jaundice, seizures, and coma which will lead to death. The mortality rate of ingestion of the death cap mushroom is believed to be around 10–30%.

Some authorities strongly advise against putting suspected death caps in the same basket with fungi collected for the table and to avoid even touching them. Furthermore, the toxicity is not reduced by cooking, freezing, or drying.

Poisoning incidents usually result from errors in identification. Recent cases highlight the issue of the similarity of ''A. phalloides'' to the edible paddy straw mushroom (''Volvariella volvacea''), with East- and Southeast-Asian immigrants in Australia and the West Coast of the U.S.

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast, Pacific states, and the western seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous U.S ...

falling victim. In an episode in Oregon, four members of a Korean family required liver transplants. Many North American incidents of death cap poisoning have occurred among Laotian and Hmong immigrants, since it is easily confused with ''A. princeps'' ("white Caesar"), a popular mushroom in their native countries. Of the 9 people poisoned in the Canberra region between 1988 and 2011, three were from Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

and two were from China. In January 2012, four people were accidentally poisoned when death caps (reportedly misidentified as straw fungi, which are popular in Chinese and other Asian dishes) were served for dinner in Canberra; all the victims required hospital treatment and two of them died, with a third requiring a liver transplant.

Signs and symptoms

Death caps have been reported to taste pleasant. This, coupled with the delay in the appearance of symptoms—during which time internal organs are being severely, sometimes irreparably, damaged—makes it particularly dangerous. Initially, symptoms are gastrointestinal in nature and include colicky abdominal pain, with watery diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, which may lead to dehydration if left untreated, and, in severe cases, hypotension, tachycardia, hypoglycemia, and acid–base disturbances. These first symptoms resolve two to three days after the ingestion. A more serious deterioration signifying liver involvement may then occur—jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme meta ...

, diarrhea, delirium

Delirium (also known as acute confusional state) is an organically caused decline from a previous baseline of mental function that develops over a short period of time, typically hours to days. Delirium is a syndrome encompassing disturbances in ...

, seizures, and coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

due to fulminant liver failure and attendant hepatic encephalopathy caused by the accumulation of normally liver-removed substance in the blood. Kidney failure (either secondary to severe hepatitis or caused by direct toxic kidney damage) and coagulopathy

Coagulopathy (also called a bleeding disorder) is a condition in which the blood's ability to coagulate (form clots) is impaired. This condition can cause a tendency toward prolonged or excessive bleeding (bleeding diathesis), which may occur spo ...

may appear during this stage. Life-threatening complications include increased intracranial pressure, intracranial bleeding, pancreatic inflammation, acute kidney failure, and cardiac arrest. Death generally occurs six to sixteen days after the poisoning.

Mushroom poisoning is more common in Europe than in North America. Up to the mid-20th century, the mortality rate was around 60–70%, but this has been greatly reduced with advances in medical care. A review of death cap poisoning throughout Europe from 1971 to 1980 found the overall mortality rate to be 22.4% (51.3% in children under ten and 16.5% in those older than ten). This has fallen further in more recent surveys to around 10–15%.Benjamin, p.215

Treatment

Consumption of the death cap is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization. The four main categories of therapy for poisoning are preliminary medical care, supportive measures, specific treatments, and liver transplantation. Preliminary care consists of gastric decontamination with eitheractivated carbon

Activated carbon, also called activated charcoal, is a form of carbon commonly used to filter contaminants from water and air, among many other uses. It is processed (activated) to have small, low-volume pores that increase the surface area avail ...

or gastric lavage; due to the delay between ingestion and the first symptoms of poisoning, it is common for patients to arrive for treatment many hours after ingestion, potentially reducing the efficacy of these interventions. Supportive measures are directed towards treating the dehydration which results from fluid loss during the gastrointestinal phase of intoxication and correction of metabolic acidosis

Metabolic acidosis is a serious electrolyte disorder characterized by an imbalance in the body's acid-base balance. Metabolic acidosis has three main root causes: increased acid production, loss of bicarbonate, and a reduced ability of the kidneys ...

, hypoglycemia, electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon dis ...

imbalances, and impaired coagulation.

No definitive antidote is available, but some specific treatments have been shown to improve survivability. High-dose continuous intravenous penicillin G has been reported to be of benefit, though the exact mechanism is unknown, and trials with cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus ''Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotics ...

s show promise.Benjamin, p.227 Some evidence indicates intravenous silibinin, an extract from the blessed milk thistle (''Silybum marianum''), may be beneficial in reducing the effects of death cap poisoning. A long-term clinical trial of intravenous silibinin began in the US in 2010. Silibinin prevents the uptake of amatoxins by liver cells, thereby protecting undamaged liver tissue; it also stimulates DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, leading to an increase in RNA synthesis. According to one report based on a treatment of 60 patients with silibinin, patients who started the drug within 96 hours of ingesting the mushroom and who still had intact kidney function all survived. As of February 2014 supporting research has not yet been published.

SLCO1B3 has been identified as the human hepatic uptake transporter for amatoxins; moreover, substrates and inhibitors of that protein—among others rifampicin

Rifampicin, also known as rifampin, is an ansamycin antibiotic used to treat several types of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis (TB), mycobacterium avium complex, ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, leprosy, and Legionnaires’ disease. ...

, penicillin, silibinin, antamanide

Antamanide is a cyclic decapeptide isolated from a fungus, the death cap: ''Amanita phalloides''. It is being studied as a potential anti-toxin against the effects of phalloidin and for its potential for treating edema. It contains 1 valine residu ...

, paclitaxel, ciclosporin and prednisolone—may be useful for the treatment of human amatoxin poisoning.

N-Acetylcysteine has shown promise in combination with other therapies. Animal studies indicate the amatoxins deplete hepatic glutathione; N-acetylcysteine serves as a glutathione precursor and may therefore prevent reduced glutathione levels and subsequent liver damage. None of the antidotes used have undergone prospective, randomized clinical trials, and only anecdotal support is available. Silibinin and N-acetylcysteine appear to be the therapies with the most potential benefit. Repeated doses of activated carbon may be helpful by absorbing any toxins returned to the gastrointestinal tract following enterohepatic circulation. Other methods of enhancing the elimination of the toxins have been trialed; techniques such as hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, plasmapheresis, and peritoneal dialysis have occasionally yielded success, but overall do not appear to improve outcome.

In patients developing liver failure, a liver transplant is often the only option to prevent death. Liver transplants have become a well-established option in amatoxin poisoning. This is a complicated issue, however, as transplants themselves may have significant complications and mortality; patients require long-term immunosuppression to maintain the transplant. That being the case, the criteria have been reassessed, such as onset of symptoms, prothrombin time (PT), serum bilirubin

Bilirubin (BR) (Latin for "red bile") is a red-orange compound that occurs in the normal catabolic pathway that breaks down heme in vertebrates. This catabolism is a necessary process in the body's clearance of waste products that arise from the ...

, and presence of encephalopathy, for determining at what point a transplant becomes necessary for survival. Evidence suggests, although survival rates have improved with modern medical treatment, in patients with moderate to severe poisoning, up to half of those who did recover suffered permanent liver damage.Benjamin, pp.231–232 A follow-up study has shown most survivors recover completely without any sequelae if treated within 36 hours of mushroom ingestion.

Notable victims

Several historical figures may have died from ''A. phalloides'' poisoning (or other similar, toxic ''Amanita'' species). These were either accidental poisonings orassassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

plots. Alleged victims of this kind of poisoning include Roman Emperor Claudius, Pope Clement VII, the Russian tsaritsa Natalia Naryshkina, and Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI.

R. Gordon Wasson

Robert Gordon Wasson (September 22, 1898 – December 23, 1986) was an American author, ethnomycologist, and Vice President for Public Relations at J.P. Morgan & Co.

In the course of work funded by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Wasso ...

recounted the details of these deaths, noting the likelihood of ''Amanita'' poisoning. In the case of Clement VII, the illness that led to his death lasted five months, making the case inconsistent with amatoxin poisoning. Natalia Naryshkina is said to have consumed a large quantity of pickled mushrooms prior to her death. It is unclear whether the mushrooms themselves were poisonous or if she succumbed to food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the spoilage of contaminated food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites that contaminate food,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease) ...

.

Charles VI experienced indigestion after eating a dish of sautéed mushrooms. This led to an illness from which he died 10 days later—symptomatology consistent with amatoxin poisoning. His death led to the War of the Austrian Succession. Noted Voltaire, "this dish of mushrooms changed the destiny of Europe."Benjamin, p.35

The case of Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

's poisoning is more complex. Claudius was known to have been very fond of eating Caesar's mushroom

''Amanita caesarea'', commonly known as Caesar's mushroom, is a highly regarded edible mushroom in the genus ''Amanita'', native to southern Europe and North Africa. While it was first species description, described by Giovanni Antonio Scopol ...

. Following his death, many sources have attributed it to his being fed a meal of death caps instead of Caesar's mushrooms. Ancient authors, such as Tacitus and Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

, are unanimous about poison having been added to the mushroom dish, rather than the dish having been prepared from poisonous mushrooms. Wasson speculated the poison used to kill Claudius was derived from death caps, with a fatal dose of an unknown poison (possibly a variety of nightshade

The Solanaceae , or nightshades, are a family of flowering plants that ranges from annual and perennial herbs to vines, lianas, epiphytes, shrubs, and trees, and includes a number of agricultural crops, medicinal plants, spices, weeds, and orna ...

) being administered later during his illness.Benjamin, pp.33–34 Other historians have speculated that Claudius may have died of natural causes.

See also

* List of ''Amanita'' species * List of deadly fungiReferences

Cited texts

* * *External links

UK Telegraph Newspaper (September 2008) - One woman dead, another critically ill after eating Death Cap fungi

* ttp://www.mushroomexpert.com/amanita_phalloides.html ''Amanita phalloides'': the death cap

''Amanita phalloides'': Invasion of the Death Cap

* ttp://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Amanita_phalloides.html California Fungi—Amanita phalloides

Death cap in Australia - ANBG website

On the Trail of the Death Cap Mushroom

from National Public Radio * {{Featured article phalloides Fungi of Africa Fungi of Europe Deadly fungi Hepatotoxins Fungi described in 1821